User login

This month in the journal CHEST®

Giants In Chest Medicine

Professor Emeritus Elizabeth F. Juniper, MCSP, MSc

By Dr. P. M. O’Byrne

Original Research

A Population-Based Cohort Study on the Drug-Specific Effect of Statins on Sepsis Outcome.

A Multicenter Randomized Trial of a Checklist for Endotracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults.

By Dr. D. R. Janz, et al.

Determinants of Unintentional Leaks During CPAP Treatment in OSA.

By Dr. M. Lebret, et al.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Screening for Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. P. J. Mazzone, et al.

Treating Cough Due to Non-CF and CF Bronchiectasis With Nonpharmacological Airway Clearance: CHEST Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. T. Hill, et al.

Giants In Chest Medicine

Professor Emeritus Elizabeth F. Juniper, MCSP, MSc

By Dr. P. M. O’Byrne

Original Research

A Population-Based Cohort Study on the Drug-Specific Effect of Statins on Sepsis Outcome.

A Multicenter Randomized Trial of a Checklist for Endotracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults.

By Dr. D. R. Janz, et al.

Determinants of Unintentional Leaks During CPAP Treatment in OSA.

By Dr. M. Lebret, et al.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Screening for Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. P. J. Mazzone, et al.

Treating Cough Due to Non-CF and CF Bronchiectasis With Nonpharmacological Airway Clearance: CHEST Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. T. Hill, et al.

Giants In Chest Medicine

Professor Emeritus Elizabeth F. Juniper, MCSP, MSc

By Dr. P. M. O’Byrne

Original Research

A Population-Based Cohort Study on the Drug-Specific Effect of Statins on Sepsis Outcome.

A Multicenter Randomized Trial of a Checklist for Endotracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults.

By Dr. D. R. Janz, et al.

Determinants of Unintentional Leaks During CPAP Treatment in OSA.

By Dr. M. Lebret, et al.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Screening for Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. P. J. Mazzone, et al.

Treating Cough Due to Non-CF and CF Bronchiectasis With Nonpharmacological Airway Clearance: CHEST Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. T. Hill, et al.

SAVE LIVES: Clean your hands

The World Health Organization (WHO) has announced its annual SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands 2018 campaign (Saito, et al. J Hosp Infect. 2018;98[4]:321), designating May 5, 2018, as world hand hygiene day.

Health-care-associated infections are a major patient safety problem. Unfortunately, their spread is common in hospitals and ICUs around the globe. The vehicle for these infections, including multidrug-resistant organisms, is frequently the contaminated hands of health-care workers. Health-care-acquired infections, as any other infection, can lead to sepsis and death. Infections acquired in the ICU are especially deadly, with mortalities that can be as high as 80%. Proper hand hygiene, despite being simple and inexpensive, is the single most important means of reducing the prevalence of hospital-acquired infections and the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

We have known about the significance of hand washing since the early 19th century. More recent data show that hand washing can reduce the overall prevalence of hospital-acquired infections and the cross-transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms. It is estimated that we can prevent 15% to 30% of these infections with adequate hand washing alone.

Despite the clear benefit and the understanding of the importance of hand washing, compliance with this simple intervention is only about 50%. Health-care workers tend to overestimate these rates, self-reporting a compliance of 75%. Even the latter number represents a lot of missed opportunities, and we must do something about it.

A multifaceted approach that combines education with written material, reminders, and continued feedback on performance can have an important effect on hand washing compliance and rates of hospital-acquired infections.

Sepsis is the single most important cause of death in hospitals in the United States. The campaign (http://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/en/), sponsored by the World Health Organization, should serve as a reminder to all health-care workers about the importance of adequate hand washing and as an opportunity to improve our compliance moving forward.

Despite the progress made, there is still a lot of room for improvement. We can have an impact on the number of deaths from sepsis by preventing them to occur in the first place. Wash your hands and do it well, it does not cost us anything.

Remember: It is in our hands – prevent sepsis and save lives!

Shruti Gadre, MD

Steering Committee Member, Critical Care NetWork

Angel Coz, MD, FCCP

Chair, Critical Care NetWork

The World Health Organization (WHO) has announced its annual SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands 2018 campaign (Saito, et al. J Hosp Infect. 2018;98[4]:321), designating May 5, 2018, as world hand hygiene day.

Health-care-associated infections are a major patient safety problem. Unfortunately, their spread is common in hospitals and ICUs around the globe. The vehicle for these infections, including multidrug-resistant organisms, is frequently the contaminated hands of health-care workers. Health-care-acquired infections, as any other infection, can lead to sepsis and death. Infections acquired in the ICU are especially deadly, with mortalities that can be as high as 80%. Proper hand hygiene, despite being simple and inexpensive, is the single most important means of reducing the prevalence of hospital-acquired infections and the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

We have known about the significance of hand washing since the early 19th century. More recent data show that hand washing can reduce the overall prevalence of hospital-acquired infections and the cross-transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms. It is estimated that we can prevent 15% to 30% of these infections with adequate hand washing alone.

Despite the clear benefit and the understanding of the importance of hand washing, compliance with this simple intervention is only about 50%. Health-care workers tend to overestimate these rates, self-reporting a compliance of 75%. Even the latter number represents a lot of missed opportunities, and we must do something about it.

A multifaceted approach that combines education with written material, reminders, and continued feedback on performance can have an important effect on hand washing compliance and rates of hospital-acquired infections.

Sepsis is the single most important cause of death in hospitals in the United States. The campaign (http://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/en/), sponsored by the World Health Organization, should serve as a reminder to all health-care workers about the importance of adequate hand washing and as an opportunity to improve our compliance moving forward.

Despite the progress made, there is still a lot of room for improvement. We can have an impact on the number of deaths from sepsis by preventing them to occur in the first place. Wash your hands and do it well, it does not cost us anything.

Remember: It is in our hands – prevent sepsis and save lives!

Shruti Gadre, MD

Steering Committee Member, Critical Care NetWork

Angel Coz, MD, FCCP

Chair, Critical Care NetWork

The World Health Organization (WHO) has announced its annual SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands 2018 campaign (Saito, et al. J Hosp Infect. 2018;98[4]:321), designating May 5, 2018, as world hand hygiene day.

Health-care-associated infections are a major patient safety problem. Unfortunately, their spread is common in hospitals and ICUs around the globe. The vehicle for these infections, including multidrug-resistant organisms, is frequently the contaminated hands of health-care workers. Health-care-acquired infections, as any other infection, can lead to sepsis and death. Infections acquired in the ICU are especially deadly, with mortalities that can be as high as 80%. Proper hand hygiene, despite being simple and inexpensive, is the single most important means of reducing the prevalence of hospital-acquired infections and the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

We have known about the significance of hand washing since the early 19th century. More recent data show that hand washing can reduce the overall prevalence of hospital-acquired infections and the cross-transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms. It is estimated that we can prevent 15% to 30% of these infections with adequate hand washing alone.

Despite the clear benefit and the understanding of the importance of hand washing, compliance with this simple intervention is only about 50%. Health-care workers tend to overestimate these rates, self-reporting a compliance of 75%. Even the latter number represents a lot of missed opportunities, and we must do something about it.

A multifaceted approach that combines education with written material, reminders, and continued feedback on performance can have an important effect on hand washing compliance and rates of hospital-acquired infections.

Sepsis is the single most important cause of death in hospitals in the United States. The campaign (http://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/en/), sponsored by the World Health Organization, should serve as a reminder to all health-care workers about the importance of adequate hand washing and as an opportunity to improve our compliance moving forward.

Despite the progress made, there is still a lot of room for improvement. We can have an impact on the number of deaths from sepsis by preventing them to occur in the first place. Wash your hands and do it well, it does not cost us anything.

Remember: It is in our hands – prevent sepsis and save lives!

Shruti Gadre, MD

Steering Committee Member, Critical Care NetWork

Angel Coz, MD, FCCP

Chair, Critical Care NetWork

AMA Insights

As many who read CHEST® Physician may know, we have a nucleus of dedicated volunteers who give unselfishly of their time and talent to represent our members in the area of “regulatory advocacy” and “policy advocacy” in the areas of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. It is our goal to recognize and support this valuable group of individuals who represent us in the space of coding and reimbursement, RUC activities, relationships with organizations like the ACP and the AMA, as well as our sister societies, such as ATS, SCCM, NAMDRC, CCNA, APSR, ALAT, and ERS, among others.

One of our goals, in addition to recognizing this group, is to identify and mentor the next generation of representatives. A great example of this mentorship is reflected in our involvement with the AMA. Dr. Bob McCaffree has represented CHEST for 22 years and is now mentoring Dr. Raj Desai who will be assuming this role of AMA Delegate this year. Special thanks to Dr. McCaffree for his unselfish service in this capacity and for his mentorship of Dr. Desai. I hope that you enjoy this and future CHEST® Physician articles summarizing and reflecting on the activities pertinent to CHEST at the AMA.

John Studdard, MD, FCCP

CHEST President

Collaborating with societies: CHEST and AMA

While the American Medical Association (AMA) is the oldest and largest national medical association, many physicians, both members and nonmembers, have limited understanding of the policies, processes, and strategic foci of the AMA. It is our goal to inform our membership about the workings of the AMA and how those interact with the goals of CHEST and our members. We hope to do this by publishing periodic articles in CHEST® Physician. One of the authors (DRM) has been the CHEST delegate to the AMA for more than 20 years, and the other (NRD) is CHEST’s new delegate.

- Create thriving physician practices.

- Create the medical school of the future.

- Improve health outcomes.

We will expand on these in future articles.

The AMA is both an individual member organization and a federation of geographic, ie, county and state, societies and specialty societies, as well as the uniformed services and the VA. It is this federation that comprises the House of Delegates (HOD or House), which is the principle policy-making body of the AMA. The number of delegates from each member organization (now numbering more than 170 organizations) depends on the number of individual AMA members among that organization’s members. Due to recent bylaws changes, CHEST now has two delegates. The HOD meets twice per year to establish policy on health, medical, professional, and governance matters, as well as the principles within which the AMA’s business activities are conducted.

Most member societies meet in caucuses or Section Councils prior to the voting in the House to discuss the pending business. The Specialty and Service Society (SSS) is the largest caucus in the AMA’s House of Delegates. The SSS meets twice annually in conjunction with the Interim and Annual Meetings of the HOD. There are two categories of groups in the SSS: those societies that have seats in the HOD and those seeking admission to the house.

SSS groups in the HOD include:

- 119 national medical specialties

- 2 professional interest medical associations

- 5 military service groups

An association must first be represented in the SSS for 3 years and meet the required number of AMA members before it is eligible to seek admission to the HOD.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) is an active member of the SSS but also joins with other societies of similar interests in the Section Council on Chest and Allergic Diseases. This caucus includes the ATS, SCCM, ASSM, and several allergy societies. Through the HOD, the SSS, and the Section Council, CHEST can partner with the AMA and other societies, such as ATS, to support each other’s resolutions or important regulatory issues.

In summary, the AMA plays an important role in many areas of interest to our members. And, it can be a useful forum for connecting with societies with similar interests in directing advocacy and setting policy. We plan to continue this update in future issues of CHEST® Physician.

References

1. https://www.ama-assn.org/content/ama-house-delegates Accessed: January 28, 2018

2. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/ama-steps-forward-practice-improvement-strategies Accessed: January 28, 2018

As many who read CHEST® Physician may know, we have a nucleus of dedicated volunteers who give unselfishly of their time and talent to represent our members in the area of “regulatory advocacy” and “policy advocacy” in the areas of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. It is our goal to recognize and support this valuable group of individuals who represent us in the space of coding and reimbursement, RUC activities, relationships with organizations like the ACP and the AMA, as well as our sister societies, such as ATS, SCCM, NAMDRC, CCNA, APSR, ALAT, and ERS, among others.

One of our goals, in addition to recognizing this group, is to identify and mentor the next generation of representatives. A great example of this mentorship is reflected in our involvement with the AMA. Dr. Bob McCaffree has represented CHEST for 22 years and is now mentoring Dr. Raj Desai who will be assuming this role of AMA Delegate this year. Special thanks to Dr. McCaffree for his unselfish service in this capacity and for his mentorship of Dr. Desai. I hope that you enjoy this and future CHEST® Physician articles summarizing and reflecting on the activities pertinent to CHEST at the AMA.

John Studdard, MD, FCCP

CHEST President

Collaborating with societies: CHEST and AMA

While the American Medical Association (AMA) is the oldest and largest national medical association, many physicians, both members and nonmembers, have limited understanding of the policies, processes, and strategic foci of the AMA. It is our goal to inform our membership about the workings of the AMA and how those interact with the goals of CHEST and our members. We hope to do this by publishing periodic articles in CHEST® Physician. One of the authors (DRM) has been the CHEST delegate to the AMA for more than 20 years, and the other (NRD) is CHEST’s new delegate.

- Create thriving physician practices.

- Create the medical school of the future.

- Improve health outcomes.

We will expand on these in future articles.

The AMA is both an individual member organization and a federation of geographic, ie, county and state, societies and specialty societies, as well as the uniformed services and the VA. It is this federation that comprises the House of Delegates (HOD or House), which is the principle policy-making body of the AMA. The number of delegates from each member organization (now numbering more than 170 organizations) depends on the number of individual AMA members among that organization’s members. Due to recent bylaws changes, CHEST now has two delegates. The HOD meets twice per year to establish policy on health, medical, professional, and governance matters, as well as the principles within which the AMA’s business activities are conducted.

Most member societies meet in caucuses or Section Councils prior to the voting in the House to discuss the pending business. The Specialty and Service Society (SSS) is the largest caucus in the AMA’s House of Delegates. The SSS meets twice annually in conjunction with the Interim and Annual Meetings of the HOD. There are two categories of groups in the SSS: those societies that have seats in the HOD and those seeking admission to the house.

SSS groups in the HOD include:

- 119 national medical specialties

- 2 professional interest medical associations

- 5 military service groups

An association must first be represented in the SSS for 3 years and meet the required number of AMA members before it is eligible to seek admission to the HOD.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) is an active member of the SSS but also joins with other societies of similar interests in the Section Council on Chest and Allergic Diseases. This caucus includes the ATS, SCCM, ASSM, and several allergy societies. Through the HOD, the SSS, and the Section Council, CHEST can partner with the AMA and other societies, such as ATS, to support each other’s resolutions or important regulatory issues.

In summary, the AMA plays an important role in many areas of interest to our members. And, it can be a useful forum for connecting with societies with similar interests in directing advocacy and setting policy. We plan to continue this update in future issues of CHEST® Physician.

References

1. https://www.ama-assn.org/content/ama-house-delegates Accessed: January 28, 2018

2. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/ama-steps-forward-practice-improvement-strategies Accessed: January 28, 2018

As many who read CHEST® Physician may know, we have a nucleus of dedicated volunteers who give unselfishly of their time and talent to represent our members in the area of “regulatory advocacy” and “policy advocacy” in the areas of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. It is our goal to recognize and support this valuable group of individuals who represent us in the space of coding and reimbursement, RUC activities, relationships with organizations like the ACP and the AMA, as well as our sister societies, such as ATS, SCCM, NAMDRC, CCNA, APSR, ALAT, and ERS, among others.

One of our goals, in addition to recognizing this group, is to identify and mentor the next generation of representatives. A great example of this mentorship is reflected in our involvement with the AMA. Dr. Bob McCaffree has represented CHEST for 22 years and is now mentoring Dr. Raj Desai who will be assuming this role of AMA Delegate this year. Special thanks to Dr. McCaffree for his unselfish service in this capacity and for his mentorship of Dr. Desai. I hope that you enjoy this and future CHEST® Physician articles summarizing and reflecting on the activities pertinent to CHEST at the AMA.

John Studdard, MD, FCCP

CHEST President

Collaborating with societies: CHEST and AMA

While the American Medical Association (AMA) is the oldest and largest national medical association, many physicians, both members and nonmembers, have limited understanding of the policies, processes, and strategic foci of the AMA. It is our goal to inform our membership about the workings of the AMA and how those interact with the goals of CHEST and our members. We hope to do this by publishing periodic articles in CHEST® Physician. One of the authors (DRM) has been the CHEST delegate to the AMA for more than 20 years, and the other (NRD) is CHEST’s new delegate.

- Create thriving physician practices.

- Create the medical school of the future.

- Improve health outcomes.

We will expand on these in future articles.

The AMA is both an individual member organization and a federation of geographic, ie, county and state, societies and specialty societies, as well as the uniformed services and the VA. It is this federation that comprises the House of Delegates (HOD or House), which is the principle policy-making body of the AMA. The number of delegates from each member organization (now numbering more than 170 organizations) depends on the number of individual AMA members among that organization’s members. Due to recent bylaws changes, CHEST now has two delegates. The HOD meets twice per year to establish policy on health, medical, professional, and governance matters, as well as the principles within which the AMA’s business activities are conducted.

Most member societies meet in caucuses or Section Councils prior to the voting in the House to discuss the pending business. The Specialty and Service Society (SSS) is the largest caucus in the AMA’s House of Delegates. The SSS meets twice annually in conjunction with the Interim and Annual Meetings of the HOD. There are two categories of groups in the SSS: those societies that have seats in the HOD and those seeking admission to the house.

SSS groups in the HOD include:

- 119 national medical specialties

- 2 professional interest medical associations

- 5 military service groups

An association must first be represented in the SSS for 3 years and meet the required number of AMA members before it is eligible to seek admission to the HOD.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) is an active member of the SSS but also joins with other societies of similar interests in the Section Council on Chest and Allergic Diseases. This caucus includes the ATS, SCCM, ASSM, and several allergy societies. Through the HOD, the SSS, and the Section Council, CHEST can partner with the AMA and other societies, such as ATS, to support each other’s resolutions or important regulatory issues.

In summary, the AMA plays an important role in many areas of interest to our members. And, it can be a useful forum for connecting with societies with similar interests in directing advocacy and setting policy. We plan to continue this update in future issues of CHEST® Physician.

References

1. https://www.ama-assn.org/content/ama-house-delegates Accessed: January 28, 2018

2. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/ama-steps-forward-practice-improvement-strategies Accessed: January 28, 2018

Palliative care screening, sleep devices, novel biologics

Palliative and end-of-life care

Nurse-driven palliative care screening

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve quality of life for patients with a life-threatening illness, providing holistic patient-centered support along the continuum of the disease process. Although frequently implemented in critical care settings, integrating PC in the neuro ICU has been difficult to adopt in practice due to the uncertainty in prognostication of definitive outcomes and practice culture beliefs such as the self-fulfilling prophecy (Frontera, et al. Crit Care Med. 2015;43[9]:1964; Rubin, et al. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23[2]:134; Knies, et al. Semin Neurol. 2016;36[6]:631).

At our institution, a nursing education project was conducted to pilot nurse-driven PC screenings on admission to the neuro ICU. The project evaluated nurse comfort and knowledge with identifying and recommending PC consults. Pre- and post-intervention surveys revealed that education and introduction of a PC screening tool significantly increased nurse comfort and knowledge of PC eligibility.

PC in the neuro ICU can exist to contribute to successful outcomes in patient and family care. Within neurocritical care, incorporating PC is essential to provide extra support to patients and families (Frontera, et al. 2015).

For these reasons and data from the project, nurse-driven screening may encourage appropriate early PC consults. Patient-centered care is the ultimate goal in the management of our patients. Nurse-driven PC screening can help bring various unmet PC needs to the health-care team for opportunities that might not have been met or otherwise assessed. Consider implementing nurse-driven PC screening protocols at your institution to aid in collaborative and proactive interdisciplinary care.

Danielle McCamey, ACNP

Steering Committee Member

Sleep medicine

Diagnostics, devices, and sleep

The past several months have been busy for the Sleep Medicine NetWork. We have been working to represent the interests of our membership and our patients in many arenas.

Devices coded as E0464, defined as life support mechanical ventilators used with mask-based ventilation in the home are being more frequently used. According to the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), there has been an 89-fold increase in billing for E0464 ventilators for Medicare and its beneficiaries between 2009 and 2015, increasing from $3.8M to $340M. In response, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) requested a response to specific questions related to these devices.

In 2018, the CHEST Sleep Medicine NetWork will be participating in a Federal Drug Association-sponsored workshop entitled “Study Design Considerations for Devices including Digital Health Technologies for Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SDB) in Adults,” along with other national organizations and leaders in our field. This workshop will address available technologies for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of SDB, as well as trends for digital health technologies and clinical trial design considerations.

Finally, the Sleep Medicine NetWork has wasted no time after a successful CHEST 2017 in Toronto in planning for the next annual meeting in San Antonio. We are excited to present an exciting curriculum in Sleep Medicine at CHEST 2018, so stay tuned.

Aneesa M. Das, MD, FCCP

NetWork Chair

Occupational and environmental health

Post-deployment lung disease

Since the early 1990s, ongoing military deployments to Southwest Asia remain a unique challenge from a pulmonary symptomology and diagnostic perspective.

Various airborne hazards in the deployment environment include geologic dusts, burn pit smoke, vehicle emissions, and industrial air pollution. Exposures can give rise to both acute respiratory symptoms and, in some instances, chronic lung disease. Currently, data are limited on whether inhalation of airborne particulate matter by military personnel is linked to increases in pulmonary diseases (Morris MJ, et al. US Army Med Dep J. 2016:173).

Ongoing research by the Veterans Affairs continues to enroll post-deployed personnel in an Airborne Hazard and Burn Pit Registry. Past approaches in evaluation of deployed individuals ranged from common tests such as spirometry, HRCT scanning, full PFTs, bronchoprovocation challenges, and, in some instances, lung biopsies (Krefft SD, et al. Fed Pract. 2015;32[6]:32). More novel evaluations of postdeployment dyspnea include impulse oscillometry, exhaled nitric oxide, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (Huprikar, et al. Chest. 2016;150[4]:S934A).

Members of the CHEST Occupational and Environmental Health NetWork are currently updating comprehensive approaches to evaluate military personnel with chronic respiratory symptoms from deployments. Continued emphasis, however, should be placed on diagnosing and treating common diseases such as asthma, exercise-induced bronchospasm, GERD, and upper airway disorders.

Pedro F. Lucero, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Clinical pulmonary medicine

Biologics – Birth of a new era of precision management in asthma

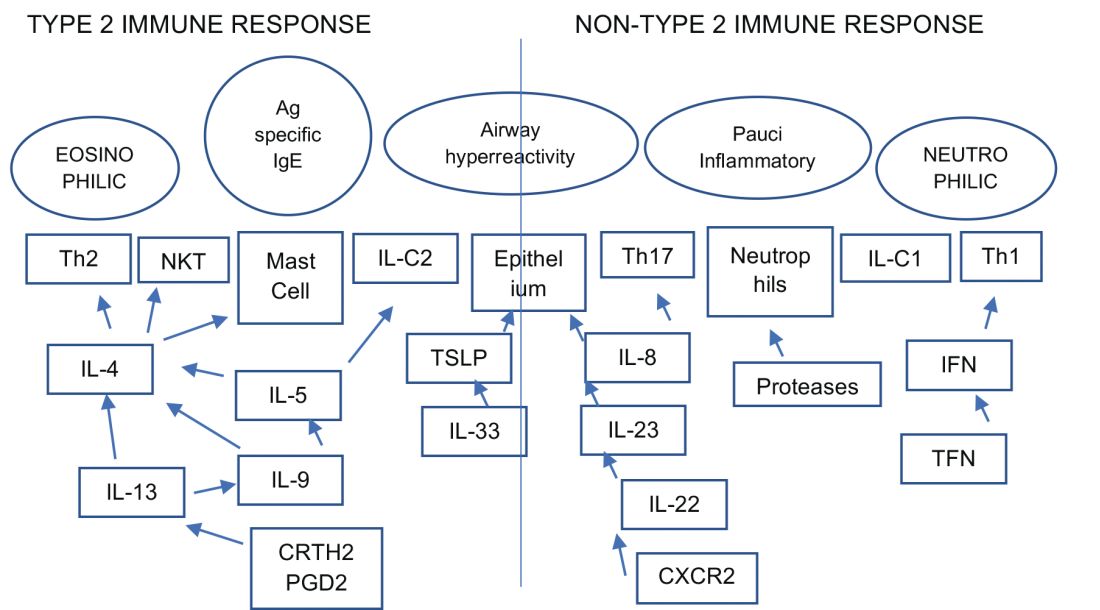

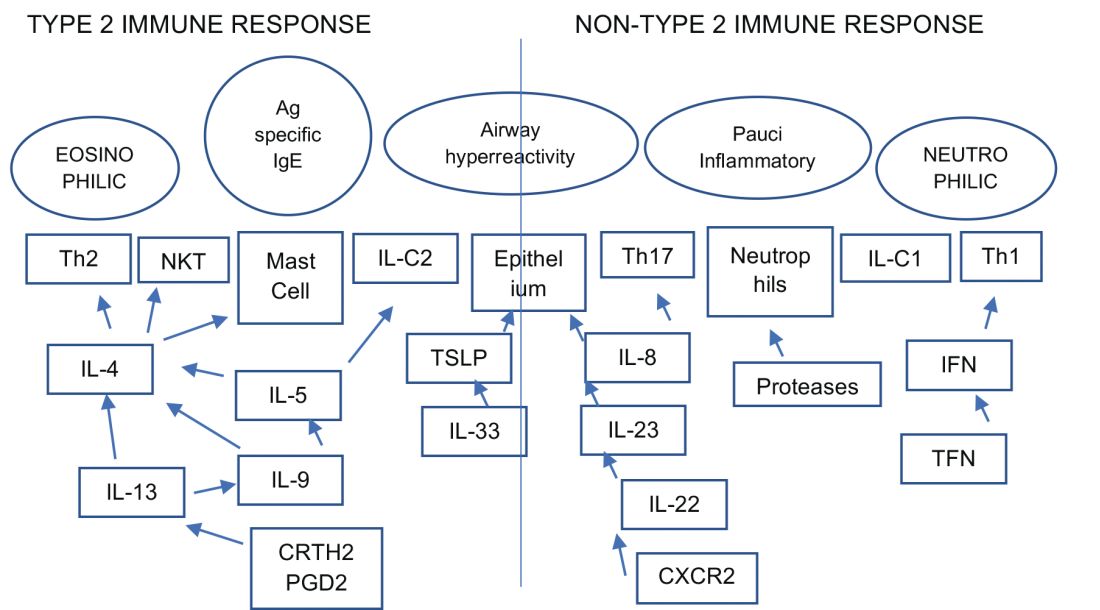

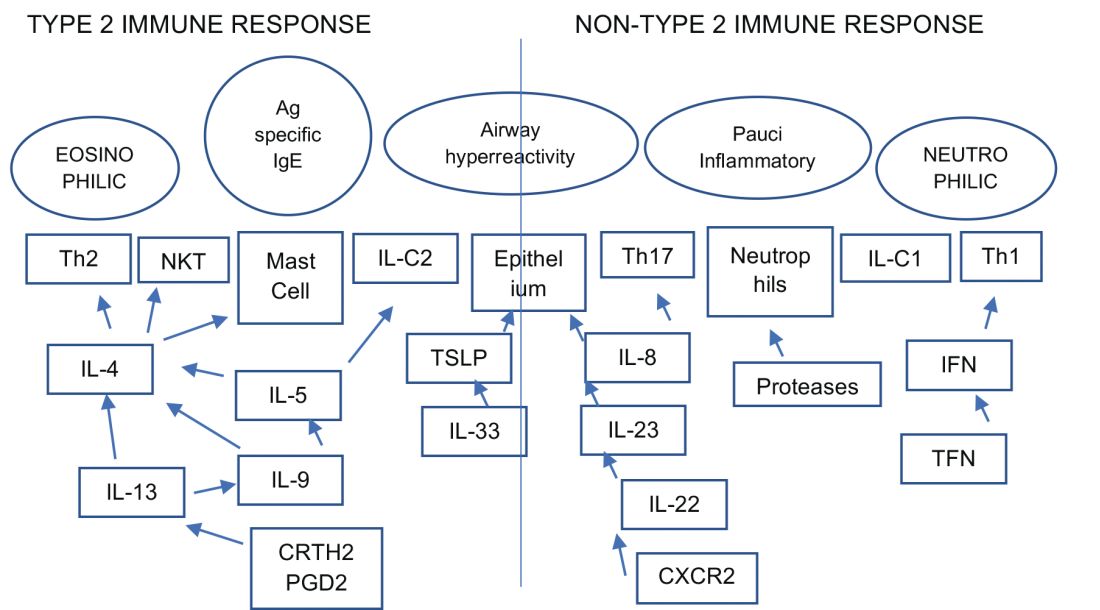

An estimated 10% to 20% of patients with severe uncontrolled asthma do not respond to maximal best standard treatments, leading to substantial health-care costs. A paradigm shift is now underway in our approach to the care of these patients with the emergence of novel biologics targeting the complex and interconnected inflammatory pathways in asthma that result in a diverse profile of asthma endotypes and phenotypes (Fig 1).

Current FDA-approved biologics primarily target patients with a T2 high phenotype (Table1).

Dupilumab binds to the alpha unit of the IL-4 receptor and blocks both IL-4 and IL-13. It shows potential efficacy in patients with T2 high asthma with or without eosinophilia but has not yet received FDA approval.

Multiple newer biologics are currently in development (Table 2).

Pulmonologists need to get familiar with the logistics of administration of these novel agents. The two common methods of administering biologics are (1) buy and bill – where the provider buys the drug directly from the distributor; and (2) assignment of benefits (typically administered by a Pharmacy Benefit Manager) - specific dose of the medication is shipped to the physician’s office and physician only bills for the administration. CPT and J codes are shown in Table 1.

Shyamsunder Subramanian, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Palliative and end-of-life care

Nurse-driven palliative care screening

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve quality of life for patients with a life-threatening illness, providing holistic patient-centered support along the continuum of the disease process. Although frequently implemented in critical care settings, integrating PC in the neuro ICU has been difficult to adopt in practice due to the uncertainty in prognostication of definitive outcomes and practice culture beliefs such as the self-fulfilling prophecy (Frontera, et al. Crit Care Med. 2015;43[9]:1964; Rubin, et al. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23[2]:134; Knies, et al. Semin Neurol. 2016;36[6]:631).

At our institution, a nursing education project was conducted to pilot nurse-driven PC screenings on admission to the neuro ICU. The project evaluated nurse comfort and knowledge with identifying and recommending PC consults. Pre- and post-intervention surveys revealed that education and introduction of a PC screening tool significantly increased nurse comfort and knowledge of PC eligibility.

PC in the neuro ICU can exist to contribute to successful outcomes in patient and family care. Within neurocritical care, incorporating PC is essential to provide extra support to patients and families (Frontera, et al. 2015).

For these reasons and data from the project, nurse-driven screening may encourage appropriate early PC consults. Patient-centered care is the ultimate goal in the management of our patients. Nurse-driven PC screening can help bring various unmet PC needs to the health-care team for opportunities that might not have been met or otherwise assessed. Consider implementing nurse-driven PC screening protocols at your institution to aid in collaborative and proactive interdisciplinary care.

Danielle McCamey, ACNP

Steering Committee Member

Sleep medicine

Diagnostics, devices, and sleep

The past several months have been busy for the Sleep Medicine NetWork. We have been working to represent the interests of our membership and our patients in many arenas.

Devices coded as E0464, defined as life support mechanical ventilators used with mask-based ventilation in the home are being more frequently used. According to the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), there has been an 89-fold increase in billing for E0464 ventilators for Medicare and its beneficiaries between 2009 and 2015, increasing from $3.8M to $340M. In response, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) requested a response to specific questions related to these devices.

In 2018, the CHEST Sleep Medicine NetWork will be participating in a Federal Drug Association-sponsored workshop entitled “Study Design Considerations for Devices including Digital Health Technologies for Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SDB) in Adults,” along with other national organizations and leaders in our field. This workshop will address available technologies for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of SDB, as well as trends for digital health technologies and clinical trial design considerations.

Finally, the Sleep Medicine NetWork has wasted no time after a successful CHEST 2017 in Toronto in planning for the next annual meeting in San Antonio. We are excited to present an exciting curriculum in Sleep Medicine at CHEST 2018, so stay tuned.

Aneesa M. Das, MD, FCCP

NetWork Chair

Occupational and environmental health

Post-deployment lung disease

Since the early 1990s, ongoing military deployments to Southwest Asia remain a unique challenge from a pulmonary symptomology and diagnostic perspective.

Various airborne hazards in the deployment environment include geologic dusts, burn pit smoke, vehicle emissions, and industrial air pollution. Exposures can give rise to both acute respiratory symptoms and, in some instances, chronic lung disease. Currently, data are limited on whether inhalation of airborne particulate matter by military personnel is linked to increases in pulmonary diseases (Morris MJ, et al. US Army Med Dep J. 2016:173).

Ongoing research by the Veterans Affairs continues to enroll post-deployed personnel in an Airborne Hazard and Burn Pit Registry. Past approaches in evaluation of deployed individuals ranged from common tests such as spirometry, HRCT scanning, full PFTs, bronchoprovocation challenges, and, in some instances, lung biopsies (Krefft SD, et al. Fed Pract. 2015;32[6]:32). More novel evaluations of postdeployment dyspnea include impulse oscillometry, exhaled nitric oxide, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (Huprikar, et al. Chest. 2016;150[4]:S934A).

Members of the CHEST Occupational and Environmental Health NetWork are currently updating comprehensive approaches to evaluate military personnel with chronic respiratory symptoms from deployments. Continued emphasis, however, should be placed on diagnosing and treating common diseases such as asthma, exercise-induced bronchospasm, GERD, and upper airway disorders.

Pedro F. Lucero, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Clinical pulmonary medicine

Biologics – Birth of a new era of precision management in asthma

An estimated 10% to 20% of patients with severe uncontrolled asthma do not respond to maximal best standard treatments, leading to substantial health-care costs. A paradigm shift is now underway in our approach to the care of these patients with the emergence of novel biologics targeting the complex and interconnected inflammatory pathways in asthma that result in a diverse profile of asthma endotypes and phenotypes (Fig 1).

Current FDA-approved biologics primarily target patients with a T2 high phenotype (Table1).

Dupilumab binds to the alpha unit of the IL-4 receptor and blocks both IL-4 and IL-13. It shows potential efficacy in patients with T2 high asthma with or without eosinophilia but has not yet received FDA approval.

Multiple newer biologics are currently in development (Table 2).

Pulmonologists need to get familiar with the logistics of administration of these novel agents. The two common methods of administering biologics are (1) buy and bill – where the provider buys the drug directly from the distributor; and (2) assignment of benefits (typically administered by a Pharmacy Benefit Manager) - specific dose of the medication is shipped to the physician’s office and physician only bills for the administration. CPT and J codes are shown in Table 1.

Shyamsunder Subramanian, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Palliative and end-of-life care

Nurse-driven palliative care screening

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve quality of life for patients with a life-threatening illness, providing holistic patient-centered support along the continuum of the disease process. Although frequently implemented in critical care settings, integrating PC in the neuro ICU has been difficult to adopt in practice due to the uncertainty in prognostication of definitive outcomes and practice culture beliefs such as the self-fulfilling prophecy (Frontera, et al. Crit Care Med. 2015;43[9]:1964; Rubin, et al. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23[2]:134; Knies, et al. Semin Neurol. 2016;36[6]:631).

At our institution, a nursing education project was conducted to pilot nurse-driven PC screenings on admission to the neuro ICU. The project evaluated nurse comfort and knowledge with identifying and recommending PC consults. Pre- and post-intervention surveys revealed that education and introduction of a PC screening tool significantly increased nurse comfort and knowledge of PC eligibility.

PC in the neuro ICU can exist to contribute to successful outcomes in patient and family care. Within neurocritical care, incorporating PC is essential to provide extra support to patients and families (Frontera, et al. 2015).

For these reasons and data from the project, nurse-driven screening may encourage appropriate early PC consults. Patient-centered care is the ultimate goal in the management of our patients. Nurse-driven PC screening can help bring various unmet PC needs to the health-care team for opportunities that might not have been met or otherwise assessed. Consider implementing nurse-driven PC screening protocols at your institution to aid in collaborative and proactive interdisciplinary care.

Danielle McCamey, ACNP

Steering Committee Member

Sleep medicine

Diagnostics, devices, and sleep

The past several months have been busy for the Sleep Medicine NetWork. We have been working to represent the interests of our membership and our patients in many arenas.

Devices coded as E0464, defined as life support mechanical ventilators used with mask-based ventilation in the home are being more frequently used. According to the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), there has been an 89-fold increase in billing for E0464 ventilators for Medicare and its beneficiaries between 2009 and 2015, increasing from $3.8M to $340M. In response, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) requested a response to specific questions related to these devices.

In 2018, the CHEST Sleep Medicine NetWork will be participating in a Federal Drug Association-sponsored workshop entitled “Study Design Considerations for Devices including Digital Health Technologies for Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SDB) in Adults,” along with other national organizations and leaders in our field. This workshop will address available technologies for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of SDB, as well as trends for digital health technologies and clinical trial design considerations.

Finally, the Sleep Medicine NetWork has wasted no time after a successful CHEST 2017 in Toronto in planning for the next annual meeting in San Antonio. We are excited to present an exciting curriculum in Sleep Medicine at CHEST 2018, so stay tuned.

Aneesa M. Das, MD, FCCP

NetWork Chair

Occupational and environmental health

Post-deployment lung disease

Since the early 1990s, ongoing military deployments to Southwest Asia remain a unique challenge from a pulmonary symptomology and diagnostic perspective.

Various airborne hazards in the deployment environment include geologic dusts, burn pit smoke, vehicle emissions, and industrial air pollution. Exposures can give rise to both acute respiratory symptoms and, in some instances, chronic lung disease. Currently, data are limited on whether inhalation of airborne particulate matter by military personnel is linked to increases in pulmonary diseases (Morris MJ, et al. US Army Med Dep J. 2016:173).

Ongoing research by the Veterans Affairs continues to enroll post-deployed personnel in an Airborne Hazard and Burn Pit Registry. Past approaches in evaluation of deployed individuals ranged from common tests such as spirometry, HRCT scanning, full PFTs, bronchoprovocation challenges, and, in some instances, lung biopsies (Krefft SD, et al. Fed Pract. 2015;32[6]:32). More novel evaluations of postdeployment dyspnea include impulse oscillometry, exhaled nitric oxide, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (Huprikar, et al. Chest. 2016;150[4]:S934A).

Members of the CHEST Occupational and Environmental Health NetWork are currently updating comprehensive approaches to evaluate military personnel with chronic respiratory symptoms from deployments. Continued emphasis, however, should be placed on diagnosing and treating common diseases such as asthma, exercise-induced bronchospasm, GERD, and upper airway disorders.

Pedro F. Lucero, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Clinical pulmonary medicine

Biologics – Birth of a new era of precision management in asthma

An estimated 10% to 20% of patients with severe uncontrolled asthma do not respond to maximal best standard treatments, leading to substantial health-care costs. A paradigm shift is now underway in our approach to the care of these patients with the emergence of novel biologics targeting the complex and interconnected inflammatory pathways in asthma that result in a diverse profile of asthma endotypes and phenotypes (Fig 1).

Current FDA-approved biologics primarily target patients with a T2 high phenotype (Table1).

Dupilumab binds to the alpha unit of the IL-4 receptor and blocks both IL-4 and IL-13. It shows potential efficacy in patients with T2 high asthma with or without eosinophilia but has not yet received FDA approval.

Multiple newer biologics are currently in development (Table 2).

Pulmonologists need to get familiar with the logistics of administration of these novel agents. The two common methods of administering biologics are (1) buy and bill – where the provider buys the drug directly from the distributor; and (2) assignment of benefits (typically administered by a Pharmacy Benefit Manager) - specific dose of the medication is shipped to the physician’s office and physician only bills for the administration. CPT and J codes are shown in Table 1.

Shyamsunder Subramanian, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Hurricane Maria, Bloodstream Infections, Lung Cancer in Women

Disaster Response

A Natural Disaster Creates Nationwide Threat

Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in late September 2017, and the lessons learned endure as the storm exposed the vulnerability of an increasingly interconnected and fragile medical community across the continental United States. According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Puerto Rico manufactures more drug products than any US state and just under 10% of all drugs consumed by Americans, some of which do not have therapeutic alternatives. In addition, certain medical devices are only produced in Puerto Rico. The humanitarian crisis caused by Hurricane Maria consequently created critical medication and medical device shortages across the United States (FDA. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/. Accessed Feb 01, 2018).

The disruption and disorganization caused by Hurricane Maria was perhaps best exemplified by the resultant shortage of small-volume 0.9% saline injection bags, which coincided with a particularly bad flu season. The FDA temporarily allowed import of saline bags from outside the United States while concurrently expediting the approval of IV solutions from new manufacturers. The American Society for Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), meanwhile, contributed guidance on managing fluid shortages (ASHP. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/. Accessed Feb 01, 2018).

Hurricane Maria was a wake-up call for medical professionals across the United States to modernize institutional procedures and to develop contingency plans to deal with medication shortages, particularly IV fluids, since this is a recurring problem across the United States since 2014. Ultimately, the goal of health-care providers across the United States is to manage natural catastrophes, however distant, by effectively planning for and adapting to medical product shortages to ensure patient care is not interrupted and that critical shortages remain invisible to patients themselves.

Cristian Madar, MD

Steering Committee Member

Practice Operations

Are All Regulations Well Thought Out? Point of View!

Current medicine is complex, with patients presenting in the ICU with multiorgan dysfunction. The art and science of medicine is being replaced by protocolized medicine. To help streamline the care, societies and colleges are coming up with guidelines. The guideline, though, changes from year to year what has been practiced in the past has been obsolete, and what is current may not hold true in the future. With increasing health-care costs affecting physician and hospital practices, innovations are being undertaken on a daily basis. The payers, on the other hand, are trying to come up with regulations, whether one likes it or not, that have become the beacon for penalty and reward. Sometimes those regulations conflict with what is sound judgment and prudent care, cornering the providers in the box with unnecessary penalties.

Approximately 250,000 bloodstream infections occur in the United States yearly, mostly attributed to the presence of intravascular devices. The rate of central line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) in the United States is 0.8 per 1,000 central line days. The desirable rate is zero rate of CLABSI. The hospitals are being pushed to be prudent with the use of central lines and removal if not needed. The technique and sterile field along with appropriate innovation in dressing technique have been effective in reducing the CLABSI by 46% from 2008 to 2013. The hospitals and ICUs are being very vigilant in trying to avoid CLABSI and are striving to achieve the goal of a zero percentage CLABSI rate, leading to almost a state of paranoia. The efforts are being undertaken in many institutions to get all the cultures on admission to identify the organism on admission so as to be designated as a bloodstream infection (BSI) due to other causes and to avoid the CLABSI attribution. The CLABSI attribution follows a complex algorithm with no waiver for the exception outside the strict definition that is changing (The 2015 definition change resulted in an 83% increase in CLABSI rate.).

We hereby present a simple scenario for point of view, where there is very clear-cut evidence of the bloodstream infection due to abdominal sources but that BSI would be designated as CLABSI as defined by National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). The patient postoperatively presents with fever, nausea, and abdominal discomfort. The CT scan showed fluid collection suggestive of infection. Culture from the abscess grew Escherichia coli and the blood culture grew Bacteroides fargilis. This patient was labeled as BSI due to intra-abdominal cause. On the other hand, patient has pus pockets in the abdominal wall with swelling and tenderness. Cultures from the pustule grew Streptococcus Group B and the blood culture grew Staphylococcus aureus. This would be classified as soft tissue infection and primary BSI and if the patient has the central line for 2 days, it would be classified as CLABSI, even though there was a clear cut source from where the infection originated. On the other hand, if a patient has a CT scan of the abdomen or any imaging study done, which showed the pus pocket, and even if there is no abscess culture done, and if there is BSI, it would be labelled as BSI due to intra-abdominal cause rather than CLABSI.

This is one of the many examples where there is unnecessary imaging needed to avoid the designation of CLABSI, or, in other instances, unnecessary cultures on admission to avoid the CLABSI or catheter-related urinary tract infection (CAUTI) when patient is coming in from other institutions or nursing facilities to avoid the attribution of CLABSI and CAUTI, rather than what is good for the patient. We are in the time of protocol-driven medicine, which has helped in improving the patient care in certain aspects, but where are the days when the physical examination meant something rather than having to prove it by imaging and laboratory studies? Are the guidelines and regulations a solution to health-care cost and waste, or are they part of problem? You be the judge.

Adel Bassily-Marcus, MD, FCCP

Chair

Salim Surani, MD, FCCP

Vice-Chair

References

Grimes L, McMullen KM, Leone C, et al. Impact of 2015 National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Definition Changes on Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI) at a Large Healthcare System. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2016;3(suppl1):946-946.

Central line related blood infection. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/bsi/bsi.html. Accessed on 1/28/2018

Preventing central line related blood infections. A Global challenge and Global perspective. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/CLABSI_Monograph.pdf. Accessed on 1/28/2018

Transplant

Radius of Change: Will Expanding Organ Sharing Beyond Donor Service Area Enhance Access in Lung Transplantation?

In November 2017, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) prompted the United Network for Organ Sharing Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (UNOS/OPTN) to reconsider geographical boundaries of donor allocation. The impetus for change was driven by a recent litigation and data that challenged the current organ allocation algorithm on the premise that it overlooked potential high acuity candidates listed at centers outside the primary DSA (donor service area) of the donor hospital, in favor of less sick local recipients. In response, the UNOS/OPTN Executive Committee recommended the adoption of a 250-nautical mile radius from the donor hospital in lieu of the DSA as the first circle or zone A of distribution for lungs. The putative merits of this change, due to last an experimental year, is intended to provide sicker candidates with access to a broader geographic range of donors. Its impact will then be evaluated by the Thoracic Organ Transplantation Committee to make further recommendations, including possibly extending zone A to 500 miles.

The extended geographical limits have organ-specific implications. In contrast to other organs, constraints of cold ischemia limit the duration within which lungs and hearts must be transplanted. Indeed, this latter point is the basis for using a radius from the donor hospital, rather than the region, as the first circle of distribution. Furthermore, DSAs vary substantially in both size and population and performance, leading to considerable variation in access to organs for candidates based on their region of residence. Currently, more than 50% of the lung allocation in the United States occurs locally to recipients with lung allocation scores (LAS) less than 50 (Iribarne et al. Chest. 2009;135[4]:923). In addition, waiting time mortality remains high and actuarial survival remains low for those with higher LAS (Russo et al. Chest. 2010;137[3]:651). The new recommendations broaden the concentric circle approach and potentially provide enhanced access for the sickest candidates on the waiting list. However, this may increase duration of waitlist time for those with lower LAS, certain disease groups such as COPD and those listed in more conservative centers. It may conversely, however, drive transplantation in the sickest patients and increase the use of bridging strategies in high volume centers and those with ECMO capabilities, as there will now be a greater reassurance of donor offers with the wider catchment area. The implications are unclear at this time, and over the next year, the efficacy and the potential unintended consequences of this newly implemented directive should become more apparent.

Anupam Kumar, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

J. W. Awori Hayanga, MD, MPH

Steering Committee Member

Women’s Health

Lung Cancer and Steroid Hormones: An Evolving Paradigm

Lung cancer remains to be the second most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women. The risk for developing lung cancer in women is 1/17 and increases with age and smoking history. Women with stage I NSLC have better prognosis after surgical treatment compared with men (Graham et al. South Med J. 2013;106[10]:582); however. they are less likely to have undergone a low dose screening CT scan, even after meeting high risk criteria (Lamb et al. Chest. 2017;152[suppl]A623). The prognosis in advanced stage lung cancer at diagnosis does not differ among the genders or age groups (Santoro et al. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43[6]:431).

There is increasing interest in the role of steroid hormones in lung biology in health and disease with estrogen and progesterone receptors identified in both healthy and malignant tissue. The role of hormone receptors as a prognostication tool and a therapeutic target is being actively investigated.

Estrogen receptor Beta (ER-Beta) is the predominantly expressed estrogen receptor in lung cancer cells (Raso et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15[17]:5359). Increased cytoplasmic ER-alpha and ER-beta is associated with tobacco smoking and likely indicates a hormonal-smoking interaction (Siegfried. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12[1]:24). A higher nuclear expression ER-beta in women may be protective against hormone-related lung cancer (Schwartz et al. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25[36]:5785), whereas higher cytoplasmic expression of ER-alpha and ER-beta was associated with worse lung cancer survival (Cheng. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018; Jan 13). Therapies targeting ER-beta1 and its downregulation resulted in sensitizing the cells to epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors and may result in reversing EGFR-TK resistance (Fu et al. Oncol Rep. 2018;39[3]:1313).

The presence of progesterone receptors is associated with longer survival in NSCLC, and treatment with progesterone has been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit migration and invasion of lung cancer cell lines (Ishibashi et al. Cancer Res. 2005;65[14]:6450). Women over the age of 60 were found to have significant survival benefit when compared with both men and younger women (Wakelee et al. J Thoracic Oncol. 2007b; 2:S570), whereas a worse survival and earlier age of occurrence of lung cancer was associated with the exposure to HRT (Ganti et al. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24[1]:59).

The future of hormone receptor targets in lung cancer may provide new therapeutic options for patients with lung adenocarcinoma, especially those with acquired resistance to the EGFR antagonists (Hsu et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2017; 18[8] pii: E1713. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081713).

Fidaa Shaib, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Ali Jiwani, MD

NetWork Member

Disaster Response

A Natural Disaster Creates Nationwide Threat

Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in late September 2017, and the lessons learned endure as the storm exposed the vulnerability of an increasingly interconnected and fragile medical community across the continental United States. According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Puerto Rico manufactures more drug products than any US state and just under 10% of all drugs consumed by Americans, some of which do not have therapeutic alternatives. In addition, certain medical devices are only produced in Puerto Rico. The humanitarian crisis caused by Hurricane Maria consequently created critical medication and medical device shortages across the United States (FDA. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/. Accessed Feb 01, 2018).

The disruption and disorganization caused by Hurricane Maria was perhaps best exemplified by the resultant shortage of small-volume 0.9% saline injection bags, which coincided with a particularly bad flu season. The FDA temporarily allowed import of saline bags from outside the United States while concurrently expediting the approval of IV solutions from new manufacturers. The American Society for Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), meanwhile, contributed guidance on managing fluid shortages (ASHP. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/. Accessed Feb 01, 2018).

Hurricane Maria was a wake-up call for medical professionals across the United States to modernize institutional procedures and to develop contingency plans to deal with medication shortages, particularly IV fluids, since this is a recurring problem across the United States since 2014. Ultimately, the goal of health-care providers across the United States is to manage natural catastrophes, however distant, by effectively planning for and adapting to medical product shortages to ensure patient care is not interrupted and that critical shortages remain invisible to patients themselves.

Cristian Madar, MD

Steering Committee Member

Practice Operations

Are All Regulations Well Thought Out? Point of View!

Current medicine is complex, with patients presenting in the ICU with multiorgan dysfunction. The art and science of medicine is being replaced by protocolized medicine. To help streamline the care, societies and colleges are coming up with guidelines. The guideline, though, changes from year to year what has been practiced in the past has been obsolete, and what is current may not hold true in the future. With increasing health-care costs affecting physician and hospital practices, innovations are being undertaken on a daily basis. The payers, on the other hand, are trying to come up with regulations, whether one likes it or not, that have become the beacon for penalty and reward. Sometimes those regulations conflict with what is sound judgment and prudent care, cornering the providers in the box with unnecessary penalties.

Approximately 250,000 bloodstream infections occur in the United States yearly, mostly attributed to the presence of intravascular devices. The rate of central line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) in the United States is 0.8 per 1,000 central line days. The desirable rate is zero rate of CLABSI. The hospitals are being pushed to be prudent with the use of central lines and removal if not needed. The technique and sterile field along with appropriate innovation in dressing technique have been effective in reducing the CLABSI by 46% from 2008 to 2013. The hospitals and ICUs are being very vigilant in trying to avoid CLABSI and are striving to achieve the goal of a zero percentage CLABSI rate, leading to almost a state of paranoia. The efforts are being undertaken in many institutions to get all the cultures on admission to identify the organism on admission so as to be designated as a bloodstream infection (BSI) due to other causes and to avoid the CLABSI attribution. The CLABSI attribution follows a complex algorithm with no waiver for the exception outside the strict definition that is changing (The 2015 definition change resulted in an 83% increase in CLABSI rate.).

We hereby present a simple scenario for point of view, where there is very clear-cut evidence of the bloodstream infection due to abdominal sources but that BSI would be designated as CLABSI as defined by National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). The patient postoperatively presents with fever, nausea, and abdominal discomfort. The CT scan showed fluid collection suggestive of infection. Culture from the abscess grew Escherichia coli and the blood culture grew Bacteroides fargilis. This patient was labeled as BSI due to intra-abdominal cause. On the other hand, patient has pus pockets in the abdominal wall with swelling and tenderness. Cultures from the pustule grew Streptococcus Group B and the blood culture grew Staphylococcus aureus. This would be classified as soft tissue infection and primary BSI and if the patient has the central line for 2 days, it would be classified as CLABSI, even though there was a clear cut source from where the infection originated. On the other hand, if a patient has a CT scan of the abdomen or any imaging study done, which showed the pus pocket, and even if there is no abscess culture done, and if there is BSI, it would be labelled as BSI due to intra-abdominal cause rather than CLABSI.

This is one of the many examples where there is unnecessary imaging needed to avoid the designation of CLABSI, or, in other instances, unnecessary cultures on admission to avoid the CLABSI or catheter-related urinary tract infection (CAUTI) when patient is coming in from other institutions or nursing facilities to avoid the attribution of CLABSI and CAUTI, rather than what is good for the patient. We are in the time of protocol-driven medicine, which has helped in improving the patient care in certain aspects, but where are the days when the physical examination meant something rather than having to prove it by imaging and laboratory studies? Are the guidelines and regulations a solution to health-care cost and waste, or are they part of problem? You be the judge.

Adel Bassily-Marcus, MD, FCCP

Chair

Salim Surani, MD, FCCP

Vice-Chair

References

Grimes L, McMullen KM, Leone C, et al. Impact of 2015 National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Definition Changes on Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI) at a Large Healthcare System. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2016;3(suppl1):946-946.

Central line related blood infection. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/bsi/bsi.html. Accessed on 1/28/2018

Preventing central line related blood infections. A Global challenge and Global perspective. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/CLABSI_Monograph.pdf. Accessed on 1/28/2018

Transplant

Radius of Change: Will Expanding Organ Sharing Beyond Donor Service Area Enhance Access in Lung Transplantation?

In November 2017, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) prompted the United Network for Organ Sharing Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (UNOS/OPTN) to reconsider geographical boundaries of donor allocation. The impetus for change was driven by a recent litigation and data that challenged the current organ allocation algorithm on the premise that it overlooked potential high acuity candidates listed at centers outside the primary DSA (donor service area) of the donor hospital, in favor of less sick local recipients. In response, the UNOS/OPTN Executive Committee recommended the adoption of a 250-nautical mile radius from the donor hospital in lieu of the DSA as the first circle or zone A of distribution for lungs. The putative merits of this change, due to last an experimental year, is intended to provide sicker candidates with access to a broader geographic range of donors. Its impact will then be evaluated by the Thoracic Organ Transplantation Committee to make further recommendations, including possibly extending zone A to 500 miles.

The extended geographical limits have organ-specific implications. In contrast to other organs, constraints of cold ischemia limit the duration within which lungs and hearts must be transplanted. Indeed, this latter point is the basis for using a radius from the donor hospital, rather than the region, as the first circle of distribution. Furthermore, DSAs vary substantially in both size and population and performance, leading to considerable variation in access to organs for candidates based on their region of residence. Currently, more than 50% of the lung allocation in the United States occurs locally to recipients with lung allocation scores (LAS) less than 50 (Iribarne et al. Chest. 2009;135[4]:923). In addition, waiting time mortality remains high and actuarial survival remains low for those with higher LAS (Russo et al. Chest. 2010;137[3]:651). The new recommendations broaden the concentric circle approach and potentially provide enhanced access for the sickest candidates on the waiting list. However, this may increase duration of waitlist time for those with lower LAS, certain disease groups such as COPD and those listed in more conservative centers. It may conversely, however, drive transplantation in the sickest patients and increase the use of bridging strategies in high volume centers and those with ECMO capabilities, as there will now be a greater reassurance of donor offers with the wider catchment area. The implications are unclear at this time, and over the next year, the efficacy and the potential unintended consequences of this newly implemented directive should become more apparent.

Anupam Kumar, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

J. W. Awori Hayanga, MD, MPH

Steering Committee Member

Women’s Health

Lung Cancer and Steroid Hormones: An Evolving Paradigm

Lung cancer remains to be the second most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women. The risk for developing lung cancer in women is 1/17 and increases with age and smoking history. Women with stage I NSLC have better prognosis after surgical treatment compared with men (Graham et al. South Med J. 2013;106[10]:582); however. they are less likely to have undergone a low dose screening CT scan, even after meeting high risk criteria (Lamb et al. Chest. 2017;152[suppl]A623). The prognosis in advanced stage lung cancer at diagnosis does not differ among the genders or age groups (Santoro et al. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43[6]:431).

There is increasing interest in the role of steroid hormones in lung biology in health and disease with estrogen and progesterone receptors identified in both healthy and malignant tissue. The role of hormone receptors as a prognostication tool and a therapeutic target is being actively investigated.

Estrogen receptor Beta (ER-Beta) is the predominantly expressed estrogen receptor in lung cancer cells (Raso et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15[17]:5359). Increased cytoplasmic ER-alpha and ER-beta is associated with tobacco smoking and likely indicates a hormonal-smoking interaction (Siegfried. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12[1]:24). A higher nuclear expression ER-beta in women may be protective against hormone-related lung cancer (Schwartz et al. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25[36]:5785), whereas higher cytoplasmic expression of ER-alpha and ER-beta was associated with worse lung cancer survival (Cheng. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018; Jan 13). Therapies targeting ER-beta1 and its downregulation resulted in sensitizing the cells to epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors and may result in reversing EGFR-TK resistance (Fu et al. Oncol Rep. 2018;39[3]:1313).

The presence of progesterone receptors is associated with longer survival in NSCLC, and treatment with progesterone has been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit migration and invasion of lung cancer cell lines (Ishibashi et al. Cancer Res. 2005;65[14]:6450). Women over the age of 60 were found to have significant survival benefit when compared with both men and younger women (Wakelee et al. J Thoracic Oncol. 2007b; 2:S570), whereas a worse survival and earlier age of occurrence of lung cancer was associated with the exposure to HRT (Ganti et al. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24[1]:59).

The future of hormone receptor targets in lung cancer may provide new therapeutic options for patients with lung adenocarcinoma, especially those with acquired resistance to the EGFR antagonists (Hsu et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2017; 18[8] pii: E1713. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081713).

Fidaa Shaib, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Ali Jiwani, MD

NetWork Member

Disaster Response

A Natural Disaster Creates Nationwide Threat

Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in late September 2017, and the lessons learned endure as the storm exposed the vulnerability of an increasingly interconnected and fragile medical community across the continental United States. According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Puerto Rico manufactures more drug products than any US state and just under 10% of all drugs consumed by Americans, some of which do not have therapeutic alternatives. In addition, certain medical devices are only produced in Puerto Rico. The humanitarian crisis caused by Hurricane Maria consequently created critical medication and medical device shortages across the United States (FDA. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/. Accessed Feb 01, 2018).

The disruption and disorganization caused by Hurricane Maria was perhaps best exemplified by the resultant shortage of small-volume 0.9% saline injection bags, which coincided with a particularly bad flu season. The FDA temporarily allowed import of saline bags from outside the United States while concurrently expediting the approval of IV solutions from new manufacturers. The American Society for Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), meanwhile, contributed guidance on managing fluid shortages (ASHP. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/. Accessed Feb 01, 2018).

Hurricane Maria was a wake-up call for medical professionals across the United States to modernize institutional procedures and to develop contingency plans to deal with medication shortages, particularly IV fluids, since this is a recurring problem across the United States since 2014. Ultimately, the goal of health-care providers across the United States is to manage natural catastrophes, however distant, by effectively planning for and adapting to medical product shortages to ensure patient care is not interrupted and that critical shortages remain invisible to patients themselves.

Cristian Madar, MD

Steering Committee Member

Practice Operations

Are All Regulations Well Thought Out? Point of View!

Current medicine is complex, with patients presenting in the ICU with multiorgan dysfunction. The art and science of medicine is being replaced by protocolized medicine. To help streamline the care, societies and colleges are coming up with guidelines. The guideline, though, changes from year to year what has been practiced in the past has been obsolete, and what is current may not hold true in the future. With increasing health-care costs affecting physician and hospital practices, innovations are being undertaken on a daily basis. The payers, on the other hand, are trying to come up with regulations, whether one likes it or not, that have become the beacon for penalty and reward. Sometimes those regulations conflict with what is sound judgment and prudent care, cornering the providers in the box with unnecessary penalties.

Approximately 250,000 bloodstream infections occur in the United States yearly, mostly attributed to the presence of intravascular devices. The rate of central line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) in the United States is 0.8 per 1,000 central line days. The desirable rate is zero rate of CLABSI. The hospitals are being pushed to be prudent with the use of central lines and removal if not needed. The technique and sterile field along with appropriate innovation in dressing technique have been effective in reducing the CLABSI by 46% from 2008 to 2013. The hospitals and ICUs are being very vigilant in trying to avoid CLABSI and are striving to achieve the goal of a zero percentage CLABSI rate, leading to almost a state of paranoia. The efforts are being undertaken in many institutions to get all the cultures on admission to identify the organism on admission so as to be designated as a bloodstream infection (BSI) due to other causes and to avoid the CLABSI attribution. The CLABSI attribution follows a complex algorithm with no waiver for the exception outside the strict definition that is changing (The 2015 definition change resulted in an 83% increase in CLABSI rate.).

We hereby present a simple scenario for point of view, where there is very clear-cut evidence of the bloodstream infection due to abdominal sources but that BSI would be designated as CLABSI as defined by National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). The patient postoperatively presents with fever, nausea, and abdominal discomfort. The CT scan showed fluid collection suggestive of infection. Culture from the abscess grew Escherichia coli and the blood culture grew Bacteroides fargilis. This patient was labeled as BSI due to intra-abdominal cause. On the other hand, patient has pus pockets in the abdominal wall with swelling and tenderness. Cultures from the pustule grew Streptococcus Group B and the blood culture grew Staphylococcus aureus. This would be classified as soft tissue infection and primary BSI and if the patient has the central line for 2 days, it would be classified as CLABSI, even though there was a clear cut source from where the infection originated. On the other hand, if a patient has a CT scan of the abdomen or any imaging study done, which showed the pus pocket, and even if there is no abscess culture done, and if there is BSI, it would be labelled as BSI due to intra-abdominal cause rather than CLABSI.

This is one of the many examples where there is unnecessary imaging needed to avoid the designation of CLABSI, or, in other instances, unnecessary cultures on admission to avoid the CLABSI or catheter-related urinary tract infection (CAUTI) when patient is coming in from other institutions or nursing facilities to avoid the attribution of CLABSI and CAUTI, rather than what is good for the patient. We are in the time of protocol-driven medicine, which has helped in improving the patient care in certain aspects, but where are the days when the physical examination meant something rather than having to prove it by imaging and laboratory studies? Are the guidelines and regulations a solution to health-care cost and waste, or are they part of problem? You be the judge.

Adel Bassily-Marcus, MD, FCCP

Chair

Salim Surani, MD, FCCP

Vice-Chair

References

Grimes L, McMullen KM, Leone C, et al. Impact of 2015 National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Definition Changes on Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI) at a Large Healthcare System. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2016;3(suppl1):946-946.

Central line related blood infection. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/bsi/bsi.html. Accessed on 1/28/2018

Preventing central line related blood infections. A Global challenge and Global perspective. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/CLABSI_Monograph.pdf. Accessed on 1/28/2018

Transplant

Radius of Change: Will Expanding Organ Sharing Beyond Donor Service Area Enhance Access in Lung Transplantation?

In November 2017, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) prompted the United Network for Organ Sharing Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (UNOS/OPTN) to reconsider geographical boundaries of donor allocation. The impetus for change was driven by a recent litigation and data that challenged the current organ allocation algorithm on the premise that it overlooked potential high acuity candidates listed at centers outside the primary DSA (donor service area) of the donor hospital, in favor of less sick local recipients. In response, the UNOS/OPTN Executive Committee recommended the adoption of a 250-nautical mile radius from the donor hospital in lieu of the DSA as the first circle or zone A of distribution for lungs. The putative merits of this change, due to last an experimental year, is intended to provide sicker candidates with access to a broader geographic range of donors. Its impact will then be evaluated by the Thoracic Organ Transplantation Committee to make further recommendations, including possibly extending zone A to 500 miles.

The extended geographical limits have organ-specific implications. In contrast to other organs, constraints of cold ischemia limit the duration within which lungs and hearts must be transplanted. Indeed, this latter point is the basis for using a radius from the donor hospital, rather than the region, as the first circle of distribution. Furthermore, DSAs vary substantially in both size and population and performance, leading to considerable variation in access to organs for candidates based on their region of residence. Currently, more than 50% of the lung allocation in the United States occurs locally to recipients with lung allocation scores (LAS) less than 50 (Iribarne et al. Chest. 2009;135[4]:923). In addition, waiting time mortality remains high and actuarial survival remains low for those with higher LAS (Russo et al. Chest. 2010;137[3]:651). The new recommendations broaden the concentric circle approach and potentially provide enhanced access for the sickest candidates on the waiting list. However, this may increase duration of waitlist time for those with lower LAS, certain disease groups such as COPD and those listed in more conservative centers. It may conversely, however, drive transplantation in the sickest patients and increase the use of bridging strategies in high volume centers and those with ECMO capabilities, as there will now be a greater reassurance of donor offers with the wider catchment area. The implications are unclear at this time, and over the next year, the efficacy and the potential unintended consequences of this newly implemented directive should become more apparent.

Anupam Kumar, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

J. W. Awori Hayanga, MD, MPH

Steering Committee Member

Women’s Health

Lung Cancer and Steroid Hormones: An Evolving Paradigm