User login

The triple overlap: COPD-OSA-OHS. Is it time for new definitions?

In our current society, it is likely that the “skinny patient with COPD” who walks into your clinic is less and less your “traditional” patient with COPD. We are seeing in our health care systems more of the “blue bloaters” – patients with COPD and significant obesity. This phenotype is representing what we are seeing worldwide as a consequence of the rising obesity prevalence. In the United States, the prepandemic (2017-2020) estimated percentage of adults over the age of 40 with obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, was over 40%. Moreover, the estimated percentage of adults with morbid obesity (BMI at least 40 kg/m2) is close to 10% (Akinbami, LJ et al. Vital Health Stat. 2022:190:1-36) and trending up. These patients with the “triple overlap” of morbid obesity, COPD, and awake daytime hypercapnia are being seen in clinics and in-hospital settings with increasing frequency, often presenting with complicating comorbidities such as acute respiratory failure, acute heart failure, kidney disease, or pulmonary hypertension. We are now faced with managing these patients with complex disease.

The obesity paradox does not seem applicable in the triple overlap phenotype. Patients with COPD who are overweight, defined as “mild obesity,” have lower mortality when compared with normal weight and underweight patients with COPD; however, this effect diminishes when BMI increases beyond 32 kg/m2. With increasing obesity severity and aging, the risk of both obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and hypoventilation increases. It is well documented that COPD-OSA overlap is linked to worse outcomes and that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) as first-line therapy decreases readmission rates and mortality. The pathophysiology of hypoventilation in obesity is complex and multifactorial, and, although significant overlaps likely exist with comorbid COPD, by current definitions, to establish a diagnosis of obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS), one must have excluded other causes of hypoventilation, such as COPD.

These patients with the triple overlap of morbid obesity, awake daytime hypercapnia, and COPD are the subset of patients that providers struggle to fit in a diagnosis or in clinical research trials.

The triple overlap is a distinct syndrome

Different labels have been used in the medical literature: hypercapnic OSA-COPD overlap, morbid obesity and OSA-COPD overlap, hypercapnic morbidly obese COPD and OHS-COPD overlap. A better characterization of this distinctive phenotype is much needed. Patients with OSA-COPD overlap, for example, have an increased propensity to develop hypercapnia at higher FEV1 when compared with COPD without OSA – but this is thought to be a consequence of prolonged and frequent apneas and hypopneas compounded with obesity-related central hypoventilation. We found that morbidly obese patients with OSA-COPD overlap have a higher hypoxia burden, more severe OSA, and are frequently prescribed noninvasive ventilation after a failed titration polysomnogram (Htun ZM, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A1382), perhaps signaling a distinctive phenotype with worse outcomes, but the study had the inherent limitations of a single-center, retrospective design lacking data on awake hypercapnia. On the other side, the term OHS-COPD is contradictory and confusing based on current OHS diagnostic criteria.

In standardizing diagnostic criteria for patients with this triple overlap syndrome, challenges remain: would the patient with a BMI of 70 kg/m2 and fixed chronic airflow obstruction with FEV1 72% fall under the category of hypercapnic COPD vs OHS? Do these patients have worse outcomes regardless of their predominant feature? Would outcomes change if the apnea hypopnea index (AHI) is 10/h vs 65/h? More importantly, do patients with the triple overlap of COPD, morbid obesity, and daytime hypercapnia have worse outcomes when compared with hypercapnic COPD, or OHS with/without OSA? These questions can be better addressed once we agree on a definition. The patients with triple overlap syndrome have been traditionally excluded from clinical trials: the patient with morbid obesity has been excluded from chronic hypercapnic COPD clinical trials, and the patient with COPD has been excluded from OHS trials.

There are no specific clinical guidelines for this triple overlap phenotype. Positive airway pressure is the mainstay of treatment. CPAP is recommended as first-line therapy for patients with OSA-COPD overlap syndrome, while noninvasive ventilation (NIV) with bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) is recommended as first-line for the stable ambulatory hypercapnic patient with COPD. It is unclear if NIV is superior to CPAP in patients with triple overlap syndrome, although recently published data showed greater efficacy in reducing carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and improving quality of life in a small group of subjects (Zheng et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[1]:99-107). To take a step further, the subtleties of NIV set up, such as rise time and minimum inspiratory time, are contradictory: the goal in ventilating patients with COPD is to shorten inspiratory time, prolonging expiratory time, therefore allowing a shortened inspiratory cycle. In obesity, ventilation strategies aim to prolong and sustain inspiratory time to improve ventilation and dependent atelectasis. Another area of uncertainty is device selection. Should we aim to provide a respiratory assist device (RAD): the traditional, rent to own bilevel PAP without auto-expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) capabilities and lower maximum inspiratory pressure delivery capacity, vs a home mechanical ventilator at a higher expense, life-time rental, and one-way only data monitoring, which limits remote prescription adjustments, but allow auto-EPAP settings for patients with comorbid OSA? More importantly, how do we get these patients, who do not fit in any of the specified insurance criteria for PAP therapy approved for treatment?

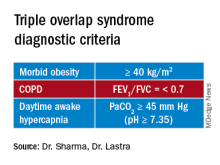

A uniform diagnostic definition and clear taxonomy allows for resource allocation, from government funded grants for clinical trials to a better-informed distribution of health care systems resources and support health care policy changes to improve patient-centric outcomes. Here, we propose that the morbidly obese patient (BMI >40 kg/m2) with chronic airflow obstruction and a forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC) <0.7 with awake daytime hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg) represents a different entity/phenotype and fits best under the triple overlap syndrome taxonomy.

We suspect that these patients have worse outcomes, including comorbidity burden, quality of life, exacerbation rates, longer hospital length-of-stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. Large, multicenter, controlled trials comparing the long-term effectiveness of NIV and CPAP: measurements of respiratory function, gas exchange, blood pressure, and health related quality of life are needed. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from volume-targeted pressure support mode ventilation with auto-EPAP capabilities upon discharge from the hospital after an acute exacerbation.

Inpatient (sleep medicine) and outpatient transitions

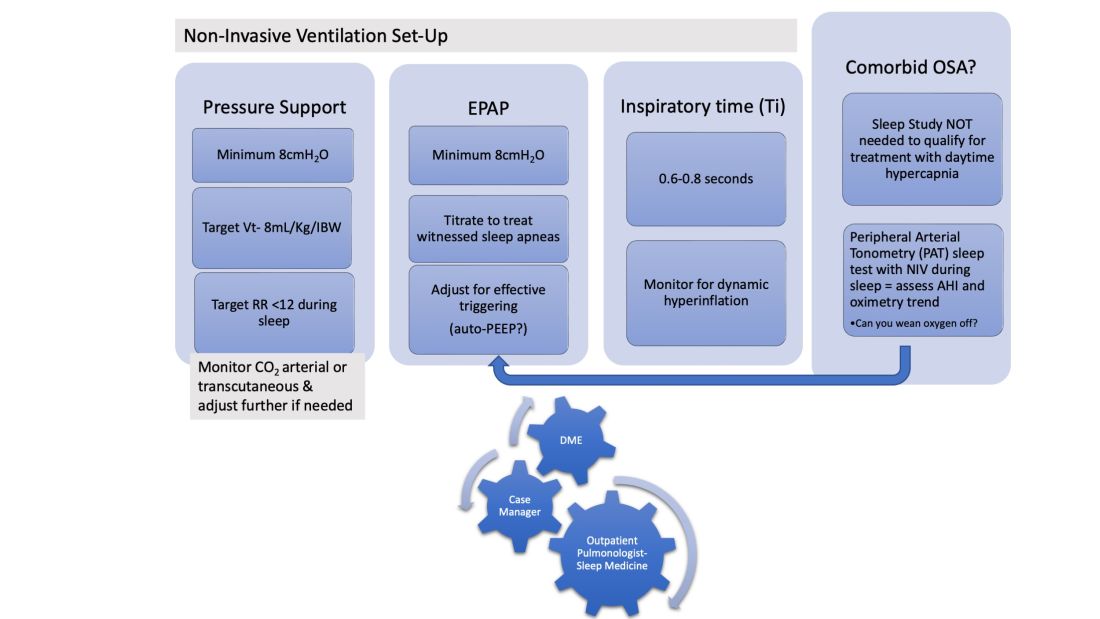

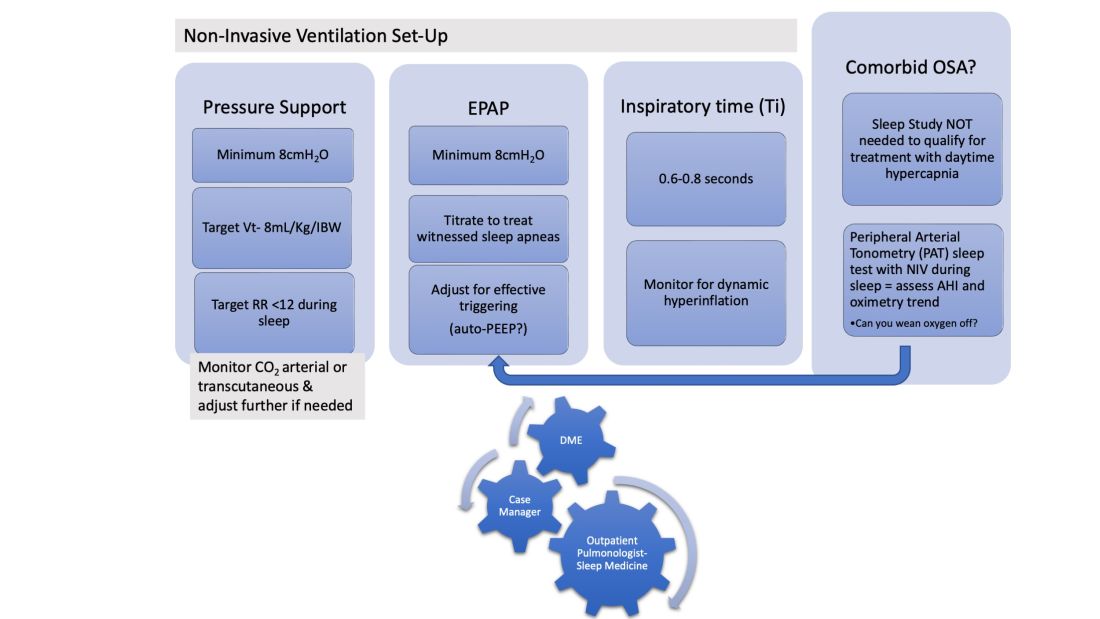

In patients hospitalized with the triple overlap syndrome, there are certain considerations that are of special interest. Given comorbid hypercapnia and limited data on NIV superiority over CPAP, a sleep study should not be needed for NIV qualification. In addition, the medical team may consider the following (Figure 1):

1. Noninvasive Ventilation:

a. Maintaining a high-pressure support differential between inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and EPAP. This can usually be achieved at 8-10 cm H2O, further adjusting to target a tidal volume (Vt) of 8 mL/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).

b. Higher EPAP: To overcome dependent atelectasis, improve ventilation-perfusion (VQ) matching, and better treat upper airway resistance both during wakefulness and sleep. Also, adjustments of EPAP at bedside should be considered to counteract auto-PEEP-related ineffective triggering if observed.

c. OSA screening and EPAP adjustment: for high residual obstructive apneas or hypopneas if data are available on the NIV device, or with the use of peripheral arterial tonometry sleep testing devices with NIV on overnight before discharge.

d. Does the patient meet criteria for oxygen supplementation at home? Wean oxygen off, if possible.

2. Case-managers can help establish services with a durable medical equipment provider with expertise in advanced PAP devices.3. Obesity management, Consider referral to an obesity management program for lifestyle/dietary modifications along with pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery interventions.

4. Close follow-up, track exacerbations. Device download data are crucial to monitor adherence/tolerance and treatment effectiveness with particular interest in AHI, oximetry, and CO2 trends monitoring. Some patients may need dedicated titration polysomnograms to adjust ventilation settings, for optimization of residual OSA or for oxygen addition or discontinuation.

Conclusion

Patients with the triple overlap phenotype have not been systematically defined, studied, or included in clinical trials. We anticipate that these patients have worse outcomes: quality of life, symptom and comorbidity burden, exacerbation rates, in-hospital mortality, longer hospital stay and ICU stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from domiciliary NIV set-up upon discharge from the hospital with close follow-up. Properly identifying these patients will help pulmonologists and health care systems direct resources to optimally manage this complex group of patients. Funding of research trials to support clinical guidelines development should be prioritized. Triple overlap syndrome is different from COPD-OSA overlap, OHS with moderate to severe OSA, or OHS without significant OSA.

In our current society, it is likely that the “skinny patient with COPD” who walks into your clinic is less and less your “traditional” patient with COPD. We are seeing in our health care systems more of the “blue bloaters” – patients with COPD and significant obesity. This phenotype is representing what we are seeing worldwide as a consequence of the rising obesity prevalence. In the United States, the prepandemic (2017-2020) estimated percentage of adults over the age of 40 with obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, was over 40%. Moreover, the estimated percentage of adults with morbid obesity (BMI at least 40 kg/m2) is close to 10% (Akinbami, LJ et al. Vital Health Stat. 2022:190:1-36) and trending up. These patients with the “triple overlap” of morbid obesity, COPD, and awake daytime hypercapnia are being seen in clinics and in-hospital settings with increasing frequency, often presenting with complicating comorbidities such as acute respiratory failure, acute heart failure, kidney disease, or pulmonary hypertension. We are now faced with managing these patients with complex disease.

The obesity paradox does not seem applicable in the triple overlap phenotype. Patients with COPD who are overweight, defined as “mild obesity,” have lower mortality when compared with normal weight and underweight patients with COPD; however, this effect diminishes when BMI increases beyond 32 kg/m2. With increasing obesity severity and aging, the risk of both obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and hypoventilation increases. It is well documented that COPD-OSA overlap is linked to worse outcomes and that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) as first-line therapy decreases readmission rates and mortality. The pathophysiology of hypoventilation in obesity is complex and multifactorial, and, although significant overlaps likely exist with comorbid COPD, by current definitions, to establish a diagnosis of obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS), one must have excluded other causes of hypoventilation, such as COPD.

These patients with the triple overlap of morbid obesity, awake daytime hypercapnia, and COPD are the subset of patients that providers struggle to fit in a diagnosis or in clinical research trials.

The triple overlap is a distinct syndrome

Different labels have been used in the medical literature: hypercapnic OSA-COPD overlap, morbid obesity and OSA-COPD overlap, hypercapnic morbidly obese COPD and OHS-COPD overlap. A better characterization of this distinctive phenotype is much needed. Patients with OSA-COPD overlap, for example, have an increased propensity to develop hypercapnia at higher FEV1 when compared with COPD without OSA – but this is thought to be a consequence of prolonged and frequent apneas and hypopneas compounded with obesity-related central hypoventilation. We found that morbidly obese patients with OSA-COPD overlap have a higher hypoxia burden, more severe OSA, and are frequently prescribed noninvasive ventilation after a failed titration polysomnogram (Htun ZM, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A1382), perhaps signaling a distinctive phenotype with worse outcomes, but the study had the inherent limitations of a single-center, retrospective design lacking data on awake hypercapnia. On the other side, the term OHS-COPD is contradictory and confusing based on current OHS diagnostic criteria.

In standardizing diagnostic criteria for patients with this triple overlap syndrome, challenges remain: would the patient with a BMI of 70 kg/m2 and fixed chronic airflow obstruction with FEV1 72% fall under the category of hypercapnic COPD vs OHS? Do these patients have worse outcomes regardless of their predominant feature? Would outcomes change if the apnea hypopnea index (AHI) is 10/h vs 65/h? More importantly, do patients with the triple overlap of COPD, morbid obesity, and daytime hypercapnia have worse outcomes when compared with hypercapnic COPD, or OHS with/without OSA? These questions can be better addressed once we agree on a definition. The patients with triple overlap syndrome have been traditionally excluded from clinical trials: the patient with morbid obesity has been excluded from chronic hypercapnic COPD clinical trials, and the patient with COPD has been excluded from OHS trials.

There are no specific clinical guidelines for this triple overlap phenotype. Positive airway pressure is the mainstay of treatment. CPAP is recommended as first-line therapy for patients with OSA-COPD overlap syndrome, while noninvasive ventilation (NIV) with bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) is recommended as first-line for the stable ambulatory hypercapnic patient with COPD. It is unclear if NIV is superior to CPAP in patients with triple overlap syndrome, although recently published data showed greater efficacy in reducing carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and improving quality of life in a small group of subjects (Zheng et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[1]:99-107). To take a step further, the subtleties of NIV set up, such as rise time and minimum inspiratory time, are contradictory: the goal in ventilating patients with COPD is to shorten inspiratory time, prolonging expiratory time, therefore allowing a shortened inspiratory cycle. In obesity, ventilation strategies aim to prolong and sustain inspiratory time to improve ventilation and dependent atelectasis. Another area of uncertainty is device selection. Should we aim to provide a respiratory assist device (RAD): the traditional, rent to own bilevel PAP without auto-expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) capabilities and lower maximum inspiratory pressure delivery capacity, vs a home mechanical ventilator at a higher expense, life-time rental, and one-way only data monitoring, which limits remote prescription adjustments, but allow auto-EPAP settings for patients with comorbid OSA? More importantly, how do we get these patients, who do not fit in any of the specified insurance criteria for PAP therapy approved for treatment?

A uniform diagnostic definition and clear taxonomy allows for resource allocation, from government funded grants for clinical trials to a better-informed distribution of health care systems resources and support health care policy changes to improve patient-centric outcomes. Here, we propose that the morbidly obese patient (BMI >40 kg/m2) with chronic airflow obstruction and a forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC) <0.7 with awake daytime hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg) represents a different entity/phenotype and fits best under the triple overlap syndrome taxonomy.

We suspect that these patients have worse outcomes, including comorbidity burden, quality of life, exacerbation rates, longer hospital length-of-stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. Large, multicenter, controlled trials comparing the long-term effectiveness of NIV and CPAP: measurements of respiratory function, gas exchange, blood pressure, and health related quality of life are needed. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from volume-targeted pressure support mode ventilation with auto-EPAP capabilities upon discharge from the hospital after an acute exacerbation.

Inpatient (sleep medicine) and outpatient transitions

In patients hospitalized with the triple overlap syndrome, there are certain considerations that are of special interest. Given comorbid hypercapnia and limited data on NIV superiority over CPAP, a sleep study should not be needed for NIV qualification. In addition, the medical team may consider the following (Figure 1):

1. Noninvasive Ventilation:

a. Maintaining a high-pressure support differential between inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and EPAP. This can usually be achieved at 8-10 cm H2O, further adjusting to target a tidal volume (Vt) of 8 mL/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).

b. Higher EPAP: To overcome dependent atelectasis, improve ventilation-perfusion (VQ) matching, and better treat upper airway resistance both during wakefulness and sleep. Also, adjustments of EPAP at bedside should be considered to counteract auto-PEEP-related ineffective triggering if observed.

c. OSA screening and EPAP adjustment: for high residual obstructive apneas or hypopneas if data are available on the NIV device, or with the use of peripheral arterial tonometry sleep testing devices with NIV on overnight before discharge.

d. Does the patient meet criteria for oxygen supplementation at home? Wean oxygen off, if possible.

2. Case-managers can help establish services with a durable medical equipment provider with expertise in advanced PAP devices.3. Obesity management, Consider referral to an obesity management program for lifestyle/dietary modifications along with pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery interventions.

4. Close follow-up, track exacerbations. Device download data are crucial to monitor adherence/tolerance and treatment effectiveness with particular interest in AHI, oximetry, and CO2 trends monitoring. Some patients may need dedicated titration polysomnograms to adjust ventilation settings, for optimization of residual OSA or for oxygen addition or discontinuation.

Conclusion

Patients with the triple overlap phenotype have not been systematically defined, studied, or included in clinical trials. We anticipate that these patients have worse outcomes: quality of life, symptom and comorbidity burden, exacerbation rates, in-hospital mortality, longer hospital stay and ICU stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from domiciliary NIV set-up upon discharge from the hospital with close follow-up. Properly identifying these patients will help pulmonologists and health care systems direct resources to optimally manage this complex group of patients. Funding of research trials to support clinical guidelines development should be prioritized. Triple overlap syndrome is different from COPD-OSA overlap, OHS with moderate to severe OSA, or OHS without significant OSA.

In our current society, it is likely that the “skinny patient with COPD” who walks into your clinic is less and less your “traditional” patient with COPD. We are seeing in our health care systems more of the “blue bloaters” – patients with COPD and significant obesity. This phenotype is representing what we are seeing worldwide as a consequence of the rising obesity prevalence. In the United States, the prepandemic (2017-2020) estimated percentage of adults over the age of 40 with obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, was over 40%. Moreover, the estimated percentage of adults with morbid obesity (BMI at least 40 kg/m2) is close to 10% (Akinbami, LJ et al. Vital Health Stat. 2022:190:1-36) and trending up. These patients with the “triple overlap” of morbid obesity, COPD, and awake daytime hypercapnia are being seen in clinics and in-hospital settings with increasing frequency, often presenting with complicating comorbidities such as acute respiratory failure, acute heart failure, kidney disease, or pulmonary hypertension. We are now faced with managing these patients with complex disease.

The obesity paradox does not seem applicable in the triple overlap phenotype. Patients with COPD who are overweight, defined as “mild obesity,” have lower mortality when compared with normal weight and underweight patients with COPD; however, this effect diminishes when BMI increases beyond 32 kg/m2. With increasing obesity severity and aging, the risk of both obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and hypoventilation increases. It is well documented that COPD-OSA overlap is linked to worse outcomes and that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) as first-line therapy decreases readmission rates and mortality. The pathophysiology of hypoventilation in obesity is complex and multifactorial, and, although significant overlaps likely exist with comorbid COPD, by current definitions, to establish a diagnosis of obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS), one must have excluded other causes of hypoventilation, such as COPD.

These patients with the triple overlap of morbid obesity, awake daytime hypercapnia, and COPD are the subset of patients that providers struggle to fit in a diagnosis or in clinical research trials.

The triple overlap is a distinct syndrome

Different labels have been used in the medical literature: hypercapnic OSA-COPD overlap, morbid obesity and OSA-COPD overlap, hypercapnic morbidly obese COPD and OHS-COPD overlap. A better characterization of this distinctive phenotype is much needed. Patients with OSA-COPD overlap, for example, have an increased propensity to develop hypercapnia at higher FEV1 when compared with COPD without OSA – but this is thought to be a consequence of prolonged and frequent apneas and hypopneas compounded with obesity-related central hypoventilation. We found that morbidly obese patients with OSA-COPD overlap have a higher hypoxia burden, more severe OSA, and are frequently prescribed noninvasive ventilation after a failed titration polysomnogram (Htun ZM, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A1382), perhaps signaling a distinctive phenotype with worse outcomes, but the study had the inherent limitations of a single-center, retrospective design lacking data on awake hypercapnia. On the other side, the term OHS-COPD is contradictory and confusing based on current OHS diagnostic criteria.

In standardizing diagnostic criteria for patients with this triple overlap syndrome, challenges remain: would the patient with a BMI of 70 kg/m2 and fixed chronic airflow obstruction with FEV1 72% fall under the category of hypercapnic COPD vs OHS? Do these patients have worse outcomes regardless of their predominant feature? Would outcomes change if the apnea hypopnea index (AHI) is 10/h vs 65/h? More importantly, do patients with the triple overlap of COPD, morbid obesity, and daytime hypercapnia have worse outcomes when compared with hypercapnic COPD, or OHS with/without OSA? These questions can be better addressed once we agree on a definition. The patients with triple overlap syndrome have been traditionally excluded from clinical trials: the patient with morbid obesity has been excluded from chronic hypercapnic COPD clinical trials, and the patient with COPD has been excluded from OHS trials.

There are no specific clinical guidelines for this triple overlap phenotype. Positive airway pressure is the mainstay of treatment. CPAP is recommended as first-line therapy for patients with OSA-COPD overlap syndrome, while noninvasive ventilation (NIV) with bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) is recommended as first-line for the stable ambulatory hypercapnic patient with COPD. It is unclear if NIV is superior to CPAP in patients with triple overlap syndrome, although recently published data showed greater efficacy in reducing carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and improving quality of life in a small group of subjects (Zheng et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[1]:99-107). To take a step further, the subtleties of NIV set up, such as rise time and minimum inspiratory time, are contradictory: the goal in ventilating patients with COPD is to shorten inspiratory time, prolonging expiratory time, therefore allowing a shortened inspiratory cycle. In obesity, ventilation strategies aim to prolong and sustain inspiratory time to improve ventilation and dependent atelectasis. Another area of uncertainty is device selection. Should we aim to provide a respiratory assist device (RAD): the traditional, rent to own bilevel PAP without auto-expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) capabilities and lower maximum inspiratory pressure delivery capacity, vs a home mechanical ventilator at a higher expense, life-time rental, and one-way only data monitoring, which limits remote prescription adjustments, but allow auto-EPAP settings for patients with comorbid OSA? More importantly, how do we get these patients, who do not fit in any of the specified insurance criteria for PAP therapy approved for treatment?

A uniform diagnostic definition and clear taxonomy allows for resource allocation, from government funded grants for clinical trials to a better-informed distribution of health care systems resources and support health care policy changes to improve patient-centric outcomes. Here, we propose that the morbidly obese patient (BMI >40 kg/m2) with chronic airflow obstruction and a forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC) <0.7 with awake daytime hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg) represents a different entity/phenotype and fits best under the triple overlap syndrome taxonomy.

We suspect that these patients have worse outcomes, including comorbidity burden, quality of life, exacerbation rates, longer hospital length-of-stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. Large, multicenter, controlled trials comparing the long-term effectiveness of NIV and CPAP: measurements of respiratory function, gas exchange, blood pressure, and health related quality of life are needed. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from volume-targeted pressure support mode ventilation with auto-EPAP capabilities upon discharge from the hospital after an acute exacerbation.

Inpatient (sleep medicine) and outpatient transitions

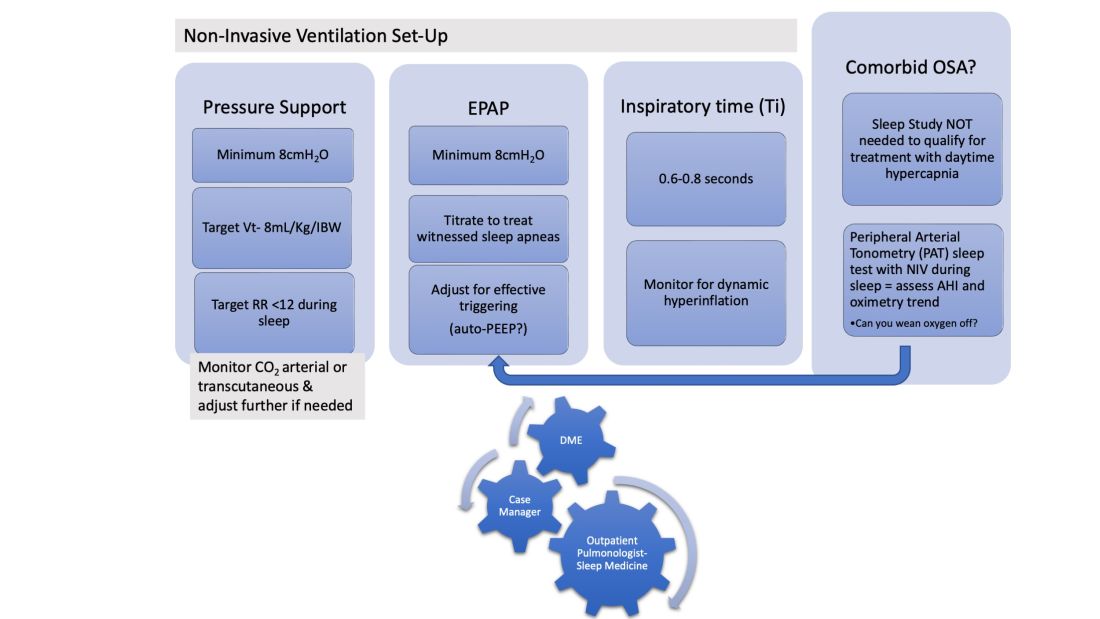

In patients hospitalized with the triple overlap syndrome, there are certain considerations that are of special interest. Given comorbid hypercapnia and limited data on NIV superiority over CPAP, a sleep study should not be needed for NIV qualification. In addition, the medical team may consider the following (Figure 1):

1. Noninvasive Ventilation:

a. Maintaining a high-pressure support differential between inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and EPAP. This can usually be achieved at 8-10 cm H2O, further adjusting to target a tidal volume (Vt) of 8 mL/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).

b. Higher EPAP: To overcome dependent atelectasis, improve ventilation-perfusion (VQ) matching, and better treat upper airway resistance both during wakefulness and sleep. Also, adjustments of EPAP at bedside should be considered to counteract auto-PEEP-related ineffective triggering if observed.

c. OSA screening and EPAP adjustment: for high residual obstructive apneas or hypopneas if data are available on the NIV device, or with the use of peripheral arterial tonometry sleep testing devices with NIV on overnight before discharge.

d. Does the patient meet criteria for oxygen supplementation at home? Wean oxygen off, if possible.

2. Case-managers can help establish services with a durable medical equipment provider with expertise in advanced PAP devices.3. Obesity management, Consider referral to an obesity management program for lifestyle/dietary modifications along with pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery interventions.

4. Close follow-up, track exacerbations. Device download data are crucial to monitor adherence/tolerance and treatment effectiveness with particular interest in AHI, oximetry, and CO2 trends monitoring. Some patients may need dedicated titration polysomnograms to adjust ventilation settings, for optimization of residual OSA or for oxygen addition or discontinuation.

Conclusion

Patients with the triple overlap phenotype have not been systematically defined, studied, or included in clinical trials. We anticipate that these patients have worse outcomes: quality of life, symptom and comorbidity burden, exacerbation rates, in-hospital mortality, longer hospital stay and ICU stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from domiciliary NIV set-up upon discharge from the hospital with close follow-up. Properly identifying these patients will help pulmonologists and health care systems direct resources to optimally manage this complex group of patients. Funding of research trials to support clinical guidelines development should be prioritized. Triple overlap syndrome is different from COPD-OSA overlap, OHS with moderate to severe OSA, or OHS without significant OSA.

Introducing CHEST President-Designate John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP

John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP, is a cardiothoracic surgeon currently serving as Chief of Oncology Services and Chair of Thoracic Surgery at Ascension Saint Thomas Health and a professor at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Dr. Howington received his undergraduate degree from Tennessee Technological University and medical degree from the University of Tennessee. He completed his general surgery residency at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and thoracic surgery residency at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Most recently, he received his Physician Executive MBA from the University of Tennessee.

As a passionate thoracic surgeon, he has lent his knowledge to the extensive CHEST lung cancer guideline portfolio for more than a decade. He offers regular leadership in multidisciplinary and executive forums and has spearheaded a series of quality improvement initiatives at Ascension. He has served in a variety of leadership roles with CHEST and with other national thoracic surgery societies.

Dr. Howington began his CHEST leadership journey with the Networks, as a member of the Interventional Chest Medicine Steering Committee and then as the Thoracic Oncology Network Chair (2008-2010).

Other leadership positions include serving as the President of the CHEST Foundation (2014-2016), member of the Scientific Program Committee and Membership Committee, and, recently, as the Chair of the Finance Committee from 2018-2021.

Since 2017, he has served on the Board of Regents as a Member at Large. Dr. Howington will serve as the 87th CHEST President in 2025.

John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP, is a cardiothoracic surgeon currently serving as Chief of Oncology Services and Chair of Thoracic Surgery at Ascension Saint Thomas Health and a professor at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Dr. Howington received his undergraduate degree from Tennessee Technological University and medical degree from the University of Tennessee. He completed his general surgery residency at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and thoracic surgery residency at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Most recently, he received his Physician Executive MBA from the University of Tennessee.

As a passionate thoracic surgeon, he has lent his knowledge to the extensive CHEST lung cancer guideline portfolio for more than a decade. He offers regular leadership in multidisciplinary and executive forums and has spearheaded a series of quality improvement initiatives at Ascension. He has served in a variety of leadership roles with CHEST and with other national thoracic surgery societies.

Dr. Howington began his CHEST leadership journey with the Networks, as a member of the Interventional Chest Medicine Steering Committee and then as the Thoracic Oncology Network Chair (2008-2010).

Other leadership positions include serving as the President of the CHEST Foundation (2014-2016), member of the Scientific Program Committee and Membership Committee, and, recently, as the Chair of the Finance Committee from 2018-2021.

Since 2017, he has served on the Board of Regents as a Member at Large. Dr. Howington will serve as the 87th CHEST President in 2025.

John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP, is a cardiothoracic surgeon currently serving as Chief of Oncology Services and Chair of Thoracic Surgery at Ascension Saint Thomas Health and a professor at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Dr. Howington received his undergraduate degree from Tennessee Technological University and medical degree from the University of Tennessee. He completed his general surgery residency at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and thoracic surgery residency at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Most recently, he received his Physician Executive MBA from the University of Tennessee.

As a passionate thoracic surgeon, he has lent his knowledge to the extensive CHEST lung cancer guideline portfolio for more than a decade. He offers regular leadership in multidisciplinary and executive forums and has spearheaded a series of quality improvement initiatives at Ascension. He has served in a variety of leadership roles with CHEST and with other national thoracic surgery societies.

Dr. Howington began his CHEST leadership journey with the Networks, as a member of the Interventional Chest Medicine Steering Committee and then as the Thoracic Oncology Network Chair (2008-2010).

Other leadership positions include serving as the President of the CHEST Foundation (2014-2016), member of the Scientific Program Committee and Membership Committee, and, recently, as the Chair of the Finance Committee from 2018-2021.

Since 2017, he has served on the Board of Regents as a Member at Large. Dr. Howington will serve as the 87th CHEST President in 2025.

Critical Care Network

Mechanical Ventilation and Airways Section

Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a ventilation modality that supports breathing by using mechanically assisted breaths without the need for intubation or a surgical airway. NIV is divided into two main types, negative-pressure ventilation (NPV) and noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV).

NPV

NPV periodically generates a negative (subatmospheric) pressure on the thorax wall, reflecting the natural breathing mechanism. As this negative pressure is transmitted into the thorax, normal atmospheric pressure air outside the thorax is pulled in for inhalation. Initiated by the negative pressure generator switching off, exhalation is passive due to elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The iron lung was a neck-to-toe horizontal cylinder used for NPV during the polio epidemic. New NPV devices are designed to fit the thorax only, using a cuirass (a torso-covering body armor molded shell).

For years, NPV use declined as NIPPV use increased. However, during the shortage of NIPPV devices during COVID and a recent recall of certain CPAP devices, NPV use has increased. NPV is an excellent alternative for those who cannot tolerate a facial mask due to facial deformity, claustrophobia, or excessive airway secretion (Corrado A et al. European Resp J. 2002;20[1]:187).

NIPPV

NIPPV is divided into several subtypes, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP or BiPAP), and average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS or VAPS). CPAP is defined as a single pressure delivered in inhalation (Pi) and exhalation (Pe). The increased mean airway pressure provides improved oxygenation (O2) but not ventilation (CO2). BPAP uses dual pressures with Pi higher than Pe. The increased mean airway pressure provides improved O2 while the difference between Pi minus Pe increases ventilation and decreases CO2.

AVAPS is a form of BPAP where Pi varies in an automated range to achieve the ordered tidal volume. In AVAPS, the generator adjusts Pi based on the average delivered tidal volume. If the average delivered tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, Pi gradually increases while not exceeding Pi Max. Patients notice improved comfort of AVAPS with a variable Pi vs. BPAP with a fixed Pi (Frank A et al. Chest. 2018;154[4]:1060A).

Samantha Tauscher, DO, Resident-in-Training

Herbert Patrick, MD, MSEE, FCCP , Member-at-Large

Mechanical Ventilation and Airways Section

Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a ventilation modality that supports breathing by using mechanically assisted breaths without the need for intubation or a surgical airway. NIV is divided into two main types, negative-pressure ventilation (NPV) and noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV).

NPV

NPV periodically generates a negative (subatmospheric) pressure on the thorax wall, reflecting the natural breathing mechanism. As this negative pressure is transmitted into the thorax, normal atmospheric pressure air outside the thorax is pulled in for inhalation. Initiated by the negative pressure generator switching off, exhalation is passive due to elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The iron lung was a neck-to-toe horizontal cylinder used for NPV during the polio epidemic. New NPV devices are designed to fit the thorax only, using a cuirass (a torso-covering body armor molded shell).

For years, NPV use declined as NIPPV use increased. However, during the shortage of NIPPV devices during COVID and a recent recall of certain CPAP devices, NPV use has increased. NPV is an excellent alternative for those who cannot tolerate a facial mask due to facial deformity, claustrophobia, or excessive airway secretion (Corrado A et al. European Resp J. 2002;20[1]:187).

NIPPV

NIPPV is divided into several subtypes, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP or BiPAP), and average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS or VAPS). CPAP is defined as a single pressure delivered in inhalation (Pi) and exhalation (Pe). The increased mean airway pressure provides improved oxygenation (O2) but not ventilation (CO2). BPAP uses dual pressures with Pi higher than Pe. The increased mean airway pressure provides improved O2 while the difference between Pi minus Pe increases ventilation and decreases CO2.

AVAPS is a form of BPAP where Pi varies in an automated range to achieve the ordered tidal volume. In AVAPS, the generator adjusts Pi based on the average delivered tidal volume. If the average delivered tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, Pi gradually increases while not exceeding Pi Max. Patients notice improved comfort of AVAPS with a variable Pi vs. BPAP with a fixed Pi (Frank A et al. Chest. 2018;154[4]:1060A).

Samantha Tauscher, DO, Resident-in-Training

Herbert Patrick, MD, MSEE, FCCP , Member-at-Large

Mechanical Ventilation and Airways Section

Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a ventilation modality that supports breathing by using mechanically assisted breaths without the need for intubation or a surgical airway. NIV is divided into two main types, negative-pressure ventilation (NPV) and noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV).

NPV

NPV periodically generates a negative (subatmospheric) pressure on the thorax wall, reflecting the natural breathing mechanism. As this negative pressure is transmitted into the thorax, normal atmospheric pressure air outside the thorax is pulled in for inhalation. Initiated by the negative pressure generator switching off, exhalation is passive due to elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The iron lung was a neck-to-toe horizontal cylinder used for NPV during the polio epidemic. New NPV devices are designed to fit the thorax only, using a cuirass (a torso-covering body armor molded shell).

For years, NPV use declined as NIPPV use increased. However, during the shortage of NIPPV devices during COVID and a recent recall of certain CPAP devices, NPV use has increased. NPV is an excellent alternative for those who cannot tolerate a facial mask due to facial deformity, claustrophobia, or excessive airway secretion (Corrado A et al. European Resp J. 2002;20[1]:187).

NIPPV

NIPPV is divided into several subtypes, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP or BiPAP), and average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS or VAPS). CPAP is defined as a single pressure delivered in inhalation (Pi) and exhalation (Pe). The increased mean airway pressure provides improved oxygenation (O2) but not ventilation (CO2). BPAP uses dual pressures with Pi higher than Pe. The increased mean airway pressure provides improved O2 while the difference between Pi minus Pe increases ventilation and decreases CO2.

AVAPS is a form of BPAP where Pi varies in an automated range to achieve the ordered tidal volume. In AVAPS, the generator adjusts Pi based on the average delivered tidal volume. If the average delivered tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, Pi gradually increases while not exceeding Pi Max. Patients notice improved comfort of AVAPS with a variable Pi vs. BPAP with a fixed Pi (Frank A et al. Chest. 2018;154[4]:1060A).

Samantha Tauscher, DO, Resident-in-Training

Herbert Patrick, MD, MSEE, FCCP , Member-at-Large

Delays in diagnosing IPF. Noninvasive ventilation. BPA and CTEPH.

Diffuse Lung Disease & Transplant Network

Interstitial Lung Disease Section

Delay in diagnosis of IPF: How bad is the problem?

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a devastating disease with a poor prognosis. Antifibrotic therapies for IPF are only capable of slowing disease progression without reversing established fibrosis. As such, the therapeutic efficacy of antifibrotic therapy may be reduced in patients whose diagnosis is delayed.

Unfortunately, diagnostic delay is common in IPF. Studies demonstrate that IPF diagnosis is delayed by more than a year after symptom onset in 43% of subjects, and more than 3 years in 19% of subjects (Cosgrove GP et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18[9]). Approximately one-third of patients with IPF have undergone chest CT imaging more than 3 years prior to diagnosis, and around the same proportion has seen a pulmonologist within the same time span (Mooney J, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16[3]:393). A median delay to IPF diagnosis of 2.2 years was noted in patients presenting to a tertiary academic medical center and was associated with an increased risk of death independent of age, sex, and forced vital capacity (adjusted hazard ratio per doubling of delay was 1.3) (Lamas DJ et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:842).

Robust improvements are clearly required for identifying patients with IPF earlier in their disease course. The Bridging Specialties Initiative from CHEST and the Three Lakes Foundation is one resource designed to improve the timely diagnosis of ILD (ILD Clinician Toolkit available at https://www.chestnet.org/Guidelines-and-Topic-Collections/Bridging-Specialties/Timely-Diagnosis-for-ILD-Patients/Clinician-Toolkit). This, and other initiatives will hopefully reduce delays in diagnosing IPF, allowing for optimal patient care.

Adrian Shifren, MBBCh, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Saniya Khan, MD, MBBS, Member-at-Large

Robert Case Jr., MD, Pulmonary & Critical Care Fellow

Critical Care Network

Mechanical Ventilation and Airways Section

Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a ventilation modality that supports breathing by using mechanically assisted breaths without the need for intubation or a surgical airway. NIV is divided into two main types, negative-pressure ventilation (NPV) and noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV).

NPV

NPV periodically generates a negative (subatmospheric) pressure on the thorax wall, reflecting the natural breathing mechanism. As this negative pressure is transmitted into the thorax, normal atmospheric pressure air outside the thorax is pulled in for inhalation. Initiated by the negative pressure generator switching off, exhalation is passive due to elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The iron lung was a neck-to-toe horizontal cylinder used for NPV during the polio epidemic. New NPV devices are designed to fit the thorax only, using a cuirass (a torso-covering body armor molded shell).

For years, NPV use declined as NIPPV use increased. However, during the shortage of NIPPV devices during COVID and a recent recall of certain CPAP devices, NPV use has increased. NPV is an excellent alternative for those who cannot tolerate a facial mask due to facial deformity, claustrophobia, or excessive airway secretion (Corrado A et al. European Resp J. 2002;20[1]:187).

NIPPV

NIPPV is divided into several subtypes, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP or BiPAP), and average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS or VAPS). CPAP is defined as a single pressure delivered in inhalation (Pi) and exhalation (Pe). The increased mean airway pressure provides improved oxygenation (O2) but not ventilation (CO2). BPAP uses dual pressures with Pi higher than Pe. The increased mean airway pressure provides improved O2 while the difference between Pi minus Pe increases ventilation and decreases CO2.

AVAPS is a form of BPAP where Pi varies in an automated range to achieve the ordered tidal volume. In AVAPS, the generator adjusts Pi based on the average delivered tidal volume. If the average delivered tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, Pi gradually increases while not exceeding Pi Max. Patients notice improved comfort of AVAPS with a variable Pi vs. BPAP with a fixed Pi (Frank A et al. Chest. 2018;154[4]:1060A).

Samantha Tauscher, DO, Resident-in-Training

Herbert Patrick, MD, MSEE, FCCP , Member-at-Large

Pulmonary Vascular & Cardiovascular Disease Network

Pulmonary Vascular Disease Section

A RACE to the finish: Revisiting the role of BPA in the management of CTEPH

Pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE) is the treatment of choice for patients with CTEPH (Kim NH et al. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801915). However, this leaves about 40% of CTEPH patients who are not operative candidates due to inaccessible distal clot burden or significant comorbidities (Pepke-Zaba J et al. Circulation 2011;124:1973). For these inoperable situations, riociguat is the only FDA-approved medical therapy (Delcroix M et al. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2002828). Balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) became a treatment option for these patients in the last 2 decades. As technique refined, BPA demonstrated improved safety data along with improved hemodynamics and increased exercise capacity (Kataoka M et al. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:756).

A recently published crossover study, the RACE trial, compared riociguat with BPA in treating inoperable CTEPH (Jaïs X et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10[10]:961). Patients were randomly assigned to either riociguat or BPA for 26 weeks. At 26 weeks, patients with pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) more than 4 Woods Units (WU) were crossed over to receive either BPA or riociguat therapy. At 26 weeks, the BPA arm showed a greater reduction in PVR but more complications, including lung injury and hemoptysis. After a 26-week crossover period, the reduction in PVR was similar in both arms. The complication rate in the BPA arm was lower when preceded by riociguat.

In patients with inoperable CTEPH, BPA has emerged as an attractive management option in addition to the medical therapy with riociguat. However, BPA should be performed at expert centers with experience. Further studies are needed to strengthen the role and optimal timing of BPA in management of post PTE patients with residual PH.

Samantha Pettigrew, MD, Fellow-in-Training

Janine Vintich, MD, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Diffuse Lung Disease & Transplant Network

Interstitial Lung Disease Section

Delay in diagnosis of IPF: How bad is the problem?

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a devastating disease with a poor prognosis. Antifibrotic therapies for IPF are only capable of slowing disease progression without reversing established fibrosis. As such, the therapeutic efficacy of antifibrotic therapy may be reduced in patients whose diagnosis is delayed.

Unfortunately, diagnostic delay is common in IPF. Studies demonstrate that IPF diagnosis is delayed by more than a year after symptom onset in 43% of subjects, and more than 3 years in 19% of subjects (Cosgrove GP et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18[9]). Approximately one-third of patients with IPF have undergone chest CT imaging more than 3 years prior to diagnosis, and around the same proportion has seen a pulmonologist within the same time span (Mooney J, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16[3]:393). A median delay to IPF diagnosis of 2.2 years was noted in patients presenting to a tertiary academic medical center and was associated with an increased risk of death independent of age, sex, and forced vital capacity (adjusted hazard ratio per doubling of delay was 1.3) (Lamas DJ et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:842).

Robust improvements are clearly required for identifying patients with IPF earlier in their disease course. The Bridging Specialties Initiative from CHEST and the Three Lakes Foundation is one resource designed to improve the timely diagnosis of ILD (ILD Clinician Toolkit available at https://www.chestnet.org/Guidelines-and-Topic-Collections/Bridging-Specialties/Timely-Diagnosis-for-ILD-Patients/Clinician-Toolkit). This, and other initiatives will hopefully reduce delays in diagnosing IPF, allowing for optimal patient care.

Adrian Shifren, MBBCh, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Saniya Khan, MD, MBBS, Member-at-Large

Robert Case Jr., MD, Pulmonary & Critical Care Fellow

Critical Care Network

Mechanical Ventilation and Airways Section

Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a ventilation modality that supports breathing by using mechanically assisted breaths without the need for intubation or a surgical airway. NIV is divided into two main types, negative-pressure ventilation (NPV) and noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV).

NPV

NPV periodically generates a negative (subatmospheric) pressure on the thorax wall, reflecting the natural breathing mechanism. As this negative pressure is transmitted into the thorax, normal atmospheric pressure air outside the thorax is pulled in for inhalation. Initiated by the negative pressure generator switching off, exhalation is passive due to elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The iron lung was a neck-to-toe horizontal cylinder used for NPV during the polio epidemic. New NPV devices are designed to fit the thorax only, using a cuirass (a torso-covering body armor molded shell).

For years, NPV use declined as NIPPV use increased. However, during the shortage of NIPPV devices during COVID and a recent recall of certain CPAP devices, NPV use has increased. NPV is an excellent alternative for those who cannot tolerate a facial mask due to facial deformity, claustrophobia, or excessive airway secretion (Corrado A et al. European Resp J. 2002;20[1]:187).

NIPPV

NIPPV is divided into several subtypes, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP or BiPAP), and average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS or VAPS). CPAP is defined as a single pressure delivered in inhalation (Pi) and exhalation (Pe). The increased mean airway pressure provides improved oxygenation (O2) but not ventilation (CO2). BPAP uses dual pressures with Pi higher than Pe. The increased mean airway pressure provides improved O2 while the difference between Pi minus Pe increases ventilation and decreases CO2.

AVAPS is a form of BPAP where Pi varies in an automated range to achieve the ordered tidal volume. In AVAPS, the generator adjusts Pi based on the average delivered tidal volume. If the average delivered tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, Pi gradually increases while not exceeding Pi Max. Patients notice improved comfort of AVAPS with a variable Pi vs. BPAP with a fixed Pi (Frank A et al. Chest. 2018;154[4]:1060A).

Samantha Tauscher, DO, Resident-in-Training

Herbert Patrick, MD, MSEE, FCCP , Member-at-Large

Pulmonary Vascular & Cardiovascular Disease Network

Pulmonary Vascular Disease Section

A RACE to the finish: Revisiting the role of BPA in the management of CTEPH

Pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE) is the treatment of choice for patients with CTEPH (Kim NH et al. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801915). However, this leaves about 40% of CTEPH patients who are not operative candidates due to inaccessible distal clot burden or significant comorbidities (Pepke-Zaba J et al. Circulation 2011;124:1973). For these inoperable situations, riociguat is the only FDA-approved medical therapy (Delcroix M et al. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2002828). Balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) became a treatment option for these patients in the last 2 decades. As technique refined, BPA demonstrated improved safety data along with improved hemodynamics and increased exercise capacity (Kataoka M et al. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:756).

A recently published crossover study, the RACE trial, compared riociguat with BPA in treating inoperable CTEPH (Jaïs X et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10[10]:961). Patients were randomly assigned to either riociguat or BPA for 26 weeks. At 26 weeks, patients with pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) more than 4 Woods Units (WU) were crossed over to receive either BPA or riociguat therapy. At 26 weeks, the BPA arm showed a greater reduction in PVR but more complications, including lung injury and hemoptysis. After a 26-week crossover period, the reduction in PVR was similar in both arms. The complication rate in the BPA arm was lower when preceded by riociguat.

In patients with inoperable CTEPH, BPA has emerged as an attractive management option in addition to the medical therapy with riociguat. However, BPA should be performed at expert centers with experience. Further studies are needed to strengthen the role and optimal timing of BPA in management of post PTE patients with residual PH.

Samantha Pettigrew, MD, Fellow-in-Training

Janine Vintich, MD, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Diffuse Lung Disease & Transplant Network

Interstitial Lung Disease Section

Delay in diagnosis of IPF: How bad is the problem?

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a devastating disease with a poor prognosis. Antifibrotic therapies for IPF are only capable of slowing disease progression without reversing established fibrosis. As such, the therapeutic efficacy of antifibrotic therapy may be reduced in patients whose diagnosis is delayed.

Unfortunately, diagnostic delay is common in IPF. Studies demonstrate that IPF diagnosis is delayed by more than a year after symptom onset in 43% of subjects, and more than 3 years in 19% of subjects (Cosgrove GP et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18[9]). Approximately one-third of patients with IPF have undergone chest CT imaging more than 3 years prior to diagnosis, and around the same proportion has seen a pulmonologist within the same time span (Mooney J, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16[3]:393). A median delay to IPF diagnosis of 2.2 years was noted in patients presenting to a tertiary academic medical center and was associated with an increased risk of death independent of age, sex, and forced vital capacity (adjusted hazard ratio per doubling of delay was 1.3) (Lamas DJ et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:842).

Robust improvements are clearly required for identifying patients with IPF earlier in their disease course. The Bridging Specialties Initiative from CHEST and the Three Lakes Foundation is one resource designed to improve the timely diagnosis of ILD (ILD Clinician Toolkit available at https://www.chestnet.org/Guidelines-and-Topic-Collections/Bridging-Specialties/Timely-Diagnosis-for-ILD-Patients/Clinician-Toolkit). This, and other initiatives will hopefully reduce delays in diagnosing IPF, allowing for optimal patient care.

Adrian Shifren, MBBCh, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Saniya Khan, MD, MBBS, Member-at-Large

Robert Case Jr., MD, Pulmonary & Critical Care Fellow

Critical Care Network

Mechanical Ventilation and Airways Section

Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a ventilation modality that supports breathing by using mechanically assisted breaths without the need for intubation or a surgical airway. NIV is divided into two main types, negative-pressure ventilation (NPV) and noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV).

NPV

NPV periodically generates a negative (subatmospheric) pressure on the thorax wall, reflecting the natural breathing mechanism. As this negative pressure is transmitted into the thorax, normal atmospheric pressure air outside the thorax is pulled in for inhalation. Initiated by the negative pressure generator switching off, exhalation is passive due to elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The iron lung was a neck-to-toe horizontal cylinder used for NPV during the polio epidemic. New NPV devices are designed to fit the thorax only, using a cuirass (a torso-covering body armor molded shell).

For years, NPV use declined as NIPPV use increased. However, during the shortage of NIPPV devices during COVID and a recent recall of certain CPAP devices, NPV use has increased. NPV is an excellent alternative for those who cannot tolerate a facial mask due to facial deformity, claustrophobia, or excessive airway secretion (Corrado A et al. European Resp J. 2002;20[1]:187).

NIPPV

NIPPV is divided into several subtypes, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP or BiPAP), and average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS or VAPS). CPAP is defined as a single pressure delivered in inhalation (Pi) and exhalation (Pe). The increased mean airway pressure provides improved oxygenation (O2) but not ventilation (CO2). BPAP uses dual pressures with Pi higher than Pe. The increased mean airway pressure provides improved O2 while the difference between Pi minus Pe increases ventilation and decreases CO2.

AVAPS is a form of BPAP where Pi varies in an automated range to achieve the ordered tidal volume. In AVAPS, the generator adjusts Pi based on the average delivered tidal volume. If the average delivered tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, Pi gradually increases while not exceeding Pi Max. Patients notice improved comfort of AVAPS with a variable Pi vs. BPAP with a fixed Pi (Frank A et al. Chest. 2018;154[4]:1060A).

Samantha Tauscher, DO, Resident-in-Training

Herbert Patrick, MD, MSEE, FCCP , Member-at-Large

Pulmonary Vascular & Cardiovascular Disease Network

Pulmonary Vascular Disease Section

A RACE to the finish: Revisiting the role of BPA in the management of CTEPH

Pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE) is the treatment of choice for patients with CTEPH (Kim NH et al. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801915). However, this leaves about 40% of CTEPH patients who are not operative candidates due to inaccessible distal clot burden or significant comorbidities (Pepke-Zaba J et al. Circulation 2011;124:1973). For these inoperable situations, riociguat is the only FDA-approved medical therapy (Delcroix M et al. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2002828). Balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) became a treatment option for these patients in the last 2 decades. As technique refined, BPA demonstrated improved safety data along with improved hemodynamics and increased exercise capacity (Kataoka M et al. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:756).

A recently published crossover study, the RACE trial, compared riociguat with BPA in treating inoperable CTEPH (Jaïs X et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10[10]:961). Patients were randomly assigned to either riociguat or BPA for 26 weeks. At 26 weeks, patients with pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) more than 4 Woods Units (WU) were crossed over to receive either BPA or riociguat therapy. At 26 weeks, the BPA arm showed a greater reduction in PVR but more complications, including lung injury and hemoptysis. After a 26-week crossover period, the reduction in PVR was similar in both arms. The complication rate in the BPA arm was lower when preceded by riociguat.

In patients with inoperable CTEPH, BPA has emerged as an attractive management option in addition to the medical therapy with riociguat. However, BPA should be performed at expert centers with experience. Further studies are needed to strengthen the role and optimal timing of BPA in management of post PTE patients with residual PH.

Samantha Pettigrew, MD, Fellow-in-Training

Janine Vintich, MD, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Continuing our list of CHEST 2022 Winners

CHEST FOUNDATION GRANT AWARDS

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Women’s Lung Health Disparities

Laura Sanapo, MD, The Miriam Hospital, Providence, R.I.

This grant is jointly supported by the CHEST Foundation and the Respiratory Health Association.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Benjamin Wu, MD, New York University

This grant is supported by AstraZeneca.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Richard Zou, MD, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation and AASM Foundation Research Grant in Sleep Medicine

Gonzalo Labarca, MD, Universidad San Sebastian, Concepción, Chile

This grant is jointly supported by the CHEST Foundation and AASM Foundation.

CHEST Foundation and American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine Research Grant in Sleep Apnea

Sherri Katz, MD, FCCP, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation and American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Sleep Medicine

Nancy Stewart, DO, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City

This grant is supported by Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Severe Asthma

Gareth Walters, MD, University Hospitals Birmingham (England)

This grant is supported by AstraZeneca.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Severe Asthma

Andréanne Côté, MD, Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de Québec, Quebec

This grant is supported by AstraZeneca.

CHEST Foundation and APCCMPD Research Grant in Medical Education

Christopher Leba, MD, MPH, University of California, San Francisco

This grant is jointly supported by the CHEST Foundation and APCCMPD.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in COVID-19

Clea Barnett, MD, New York University

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Critical Care

Katherine Walker, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Venous Thromboembolism

Daniel Lachant, DO, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center/Strong Memorial Hospital

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Pulmonary Hypertension

Christina Thornton, MD, PhD, University of Calgary (Alta.)

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Pulmonary Fibrosis

Christina Eckhardt, MD, Columbia University, New York

This grant is supported by an independent grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals and Genentech.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Pulmonary Fibrosis

John Kim, MD, University of Virginia, Charlottesville

This grant is supported by an independent grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals and Genentech.

John R. Addrizzo, MD, FCCP Research Grant in Sarcoidosis

Kerry Hena, MD, New York University

This grant is in honor of John R. Addrizzo, MD, FCCP and is jointly supported by the Addrizzo family and the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Pediatric Lung Health

Adam Shapiro, MD, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation Young Investigator Grant

Sameer Avasarala, MD, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST/ALA/ATS Respiratory Health Equity Research Award

Matthew Triplette, MD, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle

The Respiratory Health Equity Research Award is jointly supported by the American Lung Association, the American Thoracic Society, and the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST/ALA/ATS Respiratory Health Equity Research Award

Ayobami Akenroye, MD, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

The Respiratory Health Equity Research Award is jointly supported by the American Lung Association, the American Thoracic Society, and the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation Community Service Grant Honoring D. Robert McCaffree, MD, Master FCCP

Lorriane Odhiambo, PhD, Augusta (Ga.) University

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation Community Service Grant Honoring D. Robert McCaffree, MD, Master FCCP

Katie Stevens, Team Telomere, New York

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

CHEST Foundation Community Service Grant Honoring D. Robert McCaffree, MD, Master FCCP

Matthew Sharpe, MD, The University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City

This grant is supported by the CHEST Foundation.

SCIENTIFIC ABSTRACT AWARDS

Alfred Soffer Research Awards

Presented abstracts will be judged by session moderators, and award recipients will be selected for their outstanding original scientific research. Finalists will be evaluated on the basis of their written abstract and the quality of their oral presentation. This award is named in honor of Alfred Soffer, MD, Master FCCP, who was Editor in Chief of the journal CHEST® from 1968 to 1993, and Executive Director of CHEST from 1969 to 1992.

Young Investigator Awards

Investigators who are enrolled in a training or fellowship program or who have completed a fellowship program within 5 years prior to CHEST 2022 are eligible for Young Investigator Awards.

Presenters will be evaluated on the basis of their written abstract and presentation. Recipients will be selected by judges from the Scientific Presentations and Awards Committee for their outstanding original scientific research.

Top Rapid Fire Abstract Award

Awards are granted to two presenters from all the rapid fire sessions at the CHEST Annual Meeting for outstanding original scientific research and presentation

Top Case Report Award

Awards are granted to one presenter in each oral case report session at the CHEST Annual Meeting for outstanding original scientific research and presentation

Top Rapid Fire Case Report Award

Awards are granted to one presenter in each rapid fire oral case report session at the CHEST Annual Meeting for outstanding original scientific research and presentation

ALFRED SOFFER RESEARCH AWARD WINNERS

Palak Rath, MD

A Sense Of Urgency: Boarding Of Critical Care Medicine Patients In The ED

Syed Nazeer Mahmood, MD

Quantifying The Risk For Overtreatment And Undertreatment Of Severe Community Onset Pneumonia

YOUNG INVESTIGATOR AWARD WINNERS

Anusha Devarajan, MD, MBBS

Pneumomediastinum And Pneumothorax In COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Matched Case-Control Study

Marjan Islam, MD

Thoracic Ultrasound In COVID-19: Use Of Lung And Diaphragm Ultrasound In Evaluating Dyspnea In Survivors Of Critical Illness From COVID-19 Pneumonia In A Post-ICU Clinic

Aaron St Laurent, MD

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Respiratory Profiles From Real-World Registry Data: A Retrospective Longitudinal Study

ABSTRACT RAPID FIRE WINNERS

Andrew J.O. Davis, MD

Early Gas Exchange Parameters Not Associated With Survival In COVID-19-Associated ARDS Patients Requiring Prolonged Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

Benjamin Emmanuel

Clinical Outcomes In Patients With Severe Asthma Who Had Or Had Not Initiated Biologic Therapy: Results From The CLEAR Study

CASE REPORT SESSION WINNERS

Sathya Alekhya Bukkuri

Smarca4-Deficient Undifferentiated Tumor: A Rare Thoracic Malignancy

Zachary A. Banbury, MD

Fungal Aortitis In A Patient For Whom Blood Transfusion Is Not An Option: A Rare But Potentially Fatal Complication Of Aortic Valve Replacement

Harinivaas Shanmugavel Geetha, MD

Respiratory Distress After Potentially Fatal Aspirin Overdose: When To Intubate?

Lisa Hayes

Systemic Epstein-Barr Virus-Related T-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder: A Rare Cause Of Dyspnea And Pulmonary Infiltrates In An Immunocompetent Adult

Mohammed Alsaggaf, MBBS

Calcium Oxalate Deposition In Pulmonary Aspergillosis

Cheyenne Snavely

Traffic Jam In The Vasculature: A Case Of Pulmonary Leukostasis

Clarissa Smith, MD

Talcoma In Lung Cancer Screening: A Rare Benign Cause Of PET Scan Avidity

Nitin Gupta, MD

The Clue Is In The Blood Gas: A Rare Manifestation Of Lactic Acidosis

Moses Hayrabedian, MD

A Century-Old Infection Mimicking Malignancy: A Case Of Diffuse Histoplasmosis

Gabriel R. Schroeder, MD

A Case Of Wind-Instrument Associated Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

Fizza Sajid, DO

Leaping From Lush Tropical Environments To The L-Train: A Case Of Severe Leptospirosis In New York City

Krista R. Dollar, MD

Looking Past The Ground Glass: It Was Only Skin Deep

Konstantin Golubykh, MD

Point-Of-Care Ultrasound In The Timely Diagnosis Of Colonic Necrosis

Arsal Tharwani

Abdominal Compression In End-Stage Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) Improves Respiratory Compliance

Ryan Kozloski

When Asthma Isn’t: Multispecialty Approach To Fibrosing Mediastinitis

Zach S. Jarrett, DO

Vanishing Cancer: A Case Of Smoking-Related Organizing Pneumonia

Stephen Simeone

Intravascular Papillary Endothelial Hyperplasia Presenting As Thrombus In Transit With Acute Pulmonary Embolism

David Gruen, MD

Tackling Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES): A Rare Case Of Subtherapeutic Tacrolimus Causing PRES In Steroid-Resistant Nephropathy

Nicholas Kunce, MD

An Unusual Case Of Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis Presenting With Catastrophic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Phillip J. Gary, MD

Sarcoid-Like Reaction After Treatment With Pembrolizumab

Shreya Podder, MD

Endobronchial Valves For Treatment Of Persistent Air Leak After Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax In Patients With Cystic Fibrosis

Alina Aw Wasim, MD, MBBS

Chest-Wall Castleman Disease Mimicking Thymoma Drop Metastasis

Ndausung Udongwo

The ‘Rat Bite Sign” On Cardiac MRI: Left Dominant Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy As An Atypical Etiology Of Sudden Cardiac Arrest

Grant Senyei, MD

Management Of Ventriculopleural Shunt-Associated Pleural Effusion

Garima Singh, MD

COVID-19-Associated Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia Purpura (TTP)

CASE REPORT RAPID FIRE WINNERS

Sandeep Patri

Hyperammonemia Postlung Transplantation: An Uncommon But Life-Threatening Complication

Trung Nguyen

Dyspnea During Pregnancy Revealing Multiple Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations And A New Diagnosis Of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

Pedro J. Baez, MD

Adenoid Cystic Adenocarcinoma: A Rare Esophageal Malignancy Misdiagnosed As COPD

Brette Guckian, DO

Management Of Pulmonary Cement Emboli After Kyphoplasty

Brinn Demars, DO

Tumor Emboli In The Pulmonary Artery Secondary To Chondrosarcoma: A Rare Presentation Mimicking Pulmonary Thromboembolism

Aakriti Arora

A Case Of Pulmonary Hypertension As A Possible Extracranial Manifestation Of Moyamoya Disease

Racine Elaine Reinoso

Clot In Transit: The Role Of Point-Of-Care Ultrasound In Early Diagnosis And Improved Outcomes

Qiraat Azeem, MD

A Case Of Autosomal-Dominant Hyper-IgE Syndrome Masquerading As Cystic Fibrosis

Jason R. Ballengee, DO

Third-Trimester Pregnancy Complicated By Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Initially Presenting With Central Airway Obstruction And Stenosis

Sam Shafer

Caught In The Fray: Neurosarcoidosis Presenting As Chronic Respiratory Failure

Takkin Lo, MD, MPH

China White In Asthmatic Recreational Drug Users: Does It Contribute To Pneumatocele Development?

Sanjeev Shrestha, MD

Successful Treatment Of Microscopic Polyangiitis Using Novel Steroid-Sparing Agent Avacopan

Kristina Menchaca, MD

Cardiac Tamponade Without The Beck Triad: A Complication Of Severe Hypothyroidism

Olivia Millay, BS

Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Of Left Anterior Descending Artery Complicated By Ventricular Septal Rupture

Akruti P. Prabhakar, DO

Delayed Lead Perforation Of The Right Atrium In The Presence Of Persistent Left Superior Vena Cava: A Rare Coincidence

Kevin Hsu, MD

A Modified Valsalva Maneuver For Ventilated And Sedated Patients With Unstable Supraventricular Tachycardia

Nang San Hti Lar Seng

Cardiovascular Manifestations Of Paraaortic Paragangliomas

Rocio Castillo-Larios

Membranous Dehiscence After Tracheal Resection And Reconstruction Healed Spontaneously With Conservative Treatment

Fizza Sajid, DO

A Young Broken Heart, Reversed

Janeen Grant-Sittol, MD

Inhaled Tranexamic Acid Use For Massive Hemoptysis In Vasculitis-Induced Bronchoalveolar Hemorrhage

Raman G. Kutty, Md, PhD

Progressive Lung Infiltrates In Patient With Acquired Immunodeficiency: A Rare Case Of GLILD

Tanwe Shende

Mycobacterium Shimoidei: A Rare Nontuberculous Infection In A U.S. Patient

Sarah M. Upson, MD

Not Your Typical Lactic Acidosis

Prachi Saluja, MD

Late-Onset Immune Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP) After Asymptomatic COVID-19 Infection

Steven S. Wu, MD

Type 1 Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia-Associated Tracheobronchial Tumors Managed By Rigid Bronchoscopy-Directed Multimodal Tumor Destruction

Konstantin Golubykh, MD

The Reversal That Helped: Role Of Bedside Echocardiography In Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

Eric Salomon, MD

Obstructive Tracheobronchial Pulmonary Aspergillosis Managed With Local Bronchoscopic Intervention Alone

Daniel Hoesterey, MD

A Rare Case Of Critical Illness Due To Eczema Herpeticum With Disseminated Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

Awab U. Khan, DO

Severe Colchicine Toxicity In A Suicide Attempt Causing Multiorgan Failure: A Survival Story

Jacob Cebulko

Disseminated Strongyloidiasis In A Patient With Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia

Hasan Baher, MD

Hiding In Plain Sight: Disseminated Pulmonary TB

Navneet Ramesh

Multimodal Management Of Gastric Variceal Bleeding In Hemorrhagic Shock

Jason L. Peng, MD

Improving Compliance With Continuous Anterior Chest Compression In ARDS Caused By COVID-19: A Case Series

Sushan Gupta, MD

Complete Resolution Of Vasoreactive Pulmonary Artery Hypertension In Chronic Hypersensitive Pneumonitis

Mamta S. Chhabria, MD

A Fistulous Issue: Gastropleural Fistula As A Complication Of Gastrectomy

Anita Singh, DO, MBA

Identifying A Novel Surfactant Protein Mutation In A Family With Pulmonary Fibrosis

Rana Prathap Padappayil, MBBS

Delayed Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis (CSVT) After An Invasive Meningioma Resection: An Uncommon Presentation Of A Common Complication

Rubabin Tooba, MD

The Morphing Cavity: An Image Series Of A Patient’s Pulmonary Infarction Over Time

Sally Ziatabar, DO

A Rare Case Of Disseminated Blastomycosis

Sumukh Arun Kumar

Incidental Pulmonary Cavitary Lesions As An Uncommon Presentation Of Lemierre Syndrome

Sophia Emetu

Pet Peeve: Dyspnea From Undiagnosed Pasteurella Multocida Empyema

Chidambaram Ramasamy, MD

A Case Of Diffuse Alveolar-Septal Pulmonary Amyloidosis And Cardiomyopathy

Rachel Swier

Acid-Fast Bacteria In Bronchiectasis: If The Glass Slipper Does Not Fit, Non-TB Mycobacteria, Consider Tsukamurella

Catherine Durant, MD

Idiopathic Multicentric Castleman Disease With Tafro Syndrome And Sjögren Syndrome

Ali Al-Hilli, MD, MSc

Sarcoidosis-Like Reaction During Treatment For Metastatic Breast Cancer With CDK 4/6 Inhibitors: Just An Epiphenomenon Or A Causal Relationship?

Scott Slusarenko, DO

Rapidly Progressive Perimyocarditis In SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Agatha M. Formoso, MD

Two Infants Presenting With Polymicrobial Pneumonia And Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure Associated With Heterozygous Variants In Carmil2 And Itk

Juan Adams-Chahin

The Silence Of “Lam”: A Case Of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Associated With Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (Lam)

Kathleen Capaccione, MD

Lung Cancer Is Not Always The Answer: Exploring The Differential Diagnosis Of Thoracic Masses

Joann Wongvravit, DO

West Nile-Induced Myasthenia Gravis Crisis: An Unexpected Case Of Respiratory Failure

Ethan Karle, Do