User login

Late Progesterone Also Cuts Repeat Preterm Births

MIAMI BEACH — Progesterone prevents recurrent preterm delivery to the same degree whether it is initiated earlier or later in the second trimester, according to a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“We were thinking that those who started earlier would have some benefit. But essentially it doesn't matter if you start progesterone at 16–18 weeks or between 19 and 21 weeks,” said Dr. Gretchen Koontz of the ob.gyn. department at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C.

In a 2003 study, researchers randomized women with a history of previous spontaneous preterm birth (before 37 weeks) to weekly injections of either 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) or placebo (N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2379–85). Of the 306 women who received 17P between 16 and 21 weeks' gestation, 36% delivered before 37 weeks, compared with 55% of the 153 women in the placebo group, a statistically significant difference.

As a secondary analysis of the original study data, Dr. Koontz compared 227 women who began weekly injections of 17P between 16 and 18 weeks, with 272 others who began 17P between weeks 19 and 21. Results showed that 36.5% of participants in the 16− to 18-week group delivered preterm, compared with 36.1% of those in the 19− to 21-week group.

MIAMI BEACH — Progesterone prevents recurrent preterm delivery to the same degree whether it is initiated earlier or later in the second trimester, according to a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“We were thinking that those who started earlier would have some benefit. But essentially it doesn't matter if you start progesterone at 16–18 weeks or between 19 and 21 weeks,” said Dr. Gretchen Koontz of the ob.gyn. department at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C.

In a 2003 study, researchers randomized women with a history of previous spontaneous preterm birth (before 37 weeks) to weekly injections of either 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) or placebo (N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2379–85). Of the 306 women who received 17P between 16 and 21 weeks' gestation, 36% delivered before 37 weeks, compared with 55% of the 153 women in the placebo group, a statistically significant difference.

As a secondary analysis of the original study data, Dr. Koontz compared 227 women who began weekly injections of 17P between 16 and 18 weeks, with 272 others who began 17P between weeks 19 and 21. Results showed that 36.5% of participants in the 16− to 18-week group delivered preterm, compared with 36.1% of those in the 19− to 21-week group.

MIAMI BEACH — Progesterone prevents recurrent preterm delivery to the same degree whether it is initiated earlier or later in the second trimester, according to a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“We were thinking that those who started earlier would have some benefit. But essentially it doesn't matter if you start progesterone at 16–18 weeks or between 19 and 21 weeks,” said Dr. Gretchen Koontz of the ob.gyn. department at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C.

In a 2003 study, researchers randomized women with a history of previous spontaneous preterm birth (before 37 weeks) to weekly injections of either 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) or placebo (N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2379–85). Of the 306 women who received 17P between 16 and 21 weeks' gestation, 36% delivered before 37 weeks, compared with 55% of the 153 women in the placebo group, a statistically significant difference.

As a secondary analysis of the original study data, Dr. Koontz compared 227 women who began weekly injections of 17P between 16 and 18 weeks, with 272 others who began 17P between weeks 19 and 21. Results showed that 36.5% of participants in the 16− to 18-week group delivered preterm, compared with 36.1% of those in the 19− to 21-week group.

Antiangiogenic State May Be Key in Preeclampsia

MIAMI BEACH — Serum levels of soluble endoglin and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 are increased months before onset of clinical disease in patients with preeclampsia, Dr. Richard Levine said at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The findings suggest that a circulating antiangiogenic state is important in the pathogenesis of this maternal syndrome, said Dr. Levine of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Md.

“We believe that soluble endoglin [a cell surface receptor for the proangiogenic protein transforming growth factor-β and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 [an antiangiogenic factor that binds placental growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor] act in concert to produce the maternal syndrome of preeclampsia,” he said.

A nested case-control study of the Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention (CPEP) trial cohort of healthy nulliparas showed that compared with serum samples from gestational age-matched controls, the levels of these factors were significantly higher beginning 9–11 weeks before preterm preeclampsia. After preeclampsia onset, soluble endoglin (sEng) levels were almost fivefold higher (46 vs. 10 ng/mL) and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) levels were nearly threefold higher (6,356 vs. 2,316 pg/mL). Placental growth factor (PlGF) levels were approximately fourfold lower (144 vs. 546 pg/mL), Dr. Levine said.

The findings were based on an analysis of 867 serum samples obtained from 120 controls; 120 patients with term preeclampsia; 72 patients with preterm preeclampsia; 9 patients with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome; and 8 patients with eclampsia. In patients with term preeclampsia, sEng was increased beginning at 12–14 weeks, free PlGF decreased beginning at 9–11 weeks, and sFlt1 increased less than 5 weeks before preeclampsia onset. Alterations in angiogenic factors were more pronounced in early preeclampsia patients and in patients with preeclampsia plus a small-for-gestational age fetus, HELLP syndrome, or eclampsia, he noted.

Laboratory studies have suggested independent roles for both sEng and sFlt1 in the development of preeclampsia. The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that in preeclampsia, excess soluble endoglin is released from the placenta into the circulation and that it may then synergize with sFlt1, which binds PlGF and vascular endothelial growth factor to cause endothelial dysfunction, he explained. Women in this analysis with high levels of either sEng or sFlt1—but not both—had small elevations in preeclampsia risk.

MIAMI BEACH — Serum levels of soluble endoglin and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 are increased months before onset of clinical disease in patients with preeclampsia, Dr. Richard Levine said at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The findings suggest that a circulating antiangiogenic state is important in the pathogenesis of this maternal syndrome, said Dr. Levine of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Md.

“We believe that soluble endoglin [a cell surface receptor for the proangiogenic protein transforming growth factor-β and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 [an antiangiogenic factor that binds placental growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor] act in concert to produce the maternal syndrome of preeclampsia,” he said.

A nested case-control study of the Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention (CPEP) trial cohort of healthy nulliparas showed that compared with serum samples from gestational age-matched controls, the levels of these factors were significantly higher beginning 9–11 weeks before preterm preeclampsia. After preeclampsia onset, soluble endoglin (sEng) levels were almost fivefold higher (46 vs. 10 ng/mL) and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) levels were nearly threefold higher (6,356 vs. 2,316 pg/mL). Placental growth factor (PlGF) levels were approximately fourfold lower (144 vs. 546 pg/mL), Dr. Levine said.

The findings were based on an analysis of 867 serum samples obtained from 120 controls; 120 patients with term preeclampsia; 72 patients with preterm preeclampsia; 9 patients with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome; and 8 patients with eclampsia. In patients with term preeclampsia, sEng was increased beginning at 12–14 weeks, free PlGF decreased beginning at 9–11 weeks, and sFlt1 increased less than 5 weeks before preeclampsia onset. Alterations in angiogenic factors were more pronounced in early preeclampsia patients and in patients with preeclampsia plus a small-for-gestational age fetus, HELLP syndrome, or eclampsia, he noted.

Laboratory studies have suggested independent roles for both sEng and sFlt1 in the development of preeclampsia. The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that in preeclampsia, excess soluble endoglin is released from the placenta into the circulation and that it may then synergize with sFlt1, which binds PlGF and vascular endothelial growth factor to cause endothelial dysfunction, he explained. Women in this analysis with high levels of either sEng or sFlt1—but not both—had small elevations in preeclampsia risk.

MIAMI BEACH — Serum levels of soluble endoglin and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 are increased months before onset of clinical disease in patients with preeclampsia, Dr. Richard Levine said at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The findings suggest that a circulating antiangiogenic state is important in the pathogenesis of this maternal syndrome, said Dr. Levine of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Md.

“We believe that soluble endoglin [a cell surface receptor for the proangiogenic protein transforming growth factor-β and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 [an antiangiogenic factor that binds placental growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor] act in concert to produce the maternal syndrome of preeclampsia,” he said.

A nested case-control study of the Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention (CPEP) trial cohort of healthy nulliparas showed that compared with serum samples from gestational age-matched controls, the levels of these factors were significantly higher beginning 9–11 weeks before preterm preeclampsia. After preeclampsia onset, soluble endoglin (sEng) levels were almost fivefold higher (46 vs. 10 ng/mL) and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) levels were nearly threefold higher (6,356 vs. 2,316 pg/mL). Placental growth factor (PlGF) levels were approximately fourfold lower (144 vs. 546 pg/mL), Dr. Levine said.

The findings were based on an analysis of 867 serum samples obtained from 120 controls; 120 patients with term preeclampsia; 72 patients with preterm preeclampsia; 9 patients with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome; and 8 patients with eclampsia. In patients with term preeclampsia, sEng was increased beginning at 12–14 weeks, free PlGF decreased beginning at 9–11 weeks, and sFlt1 increased less than 5 weeks before preeclampsia onset. Alterations in angiogenic factors were more pronounced in early preeclampsia patients and in patients with preeclampsia plus a small-for-gestational age fetus, HELLP syndrome, or eclampsia, he noted.

Laboratory studies have suggested independent roles for both sEng and sFlt1 in the development of preeclampsia. The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that in preeclampsia, excess soluble endoglin is released from the placenta into the circulation and that it may then synergize with sFlt1, which binds PlGF and vascular endothelial growth factor to cause endothelial dysfunction, he explained. Women in this analysis with high levels of either sEng or sFlt1—but not both—had small elevations in preeclampsia risk.

Set Low Threshold for Appendectomy in Pregnant Women : Maternal and fetal mortality both escalate with perforation, so the risks of temporizing are grave.

PASADENA, CALIF. — The diagnosis of appendicitis can, of course, be exquisitely difficult in a nonpregnant patient. Pregnancy only makes the task more daunting.

However, the challenge must be met because early diagnosis and prompt surgery may mean the difference between life and death for both the mother and the fetus, said Dr. J. Gerald Quirk, who is professor and chairman of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive medicine at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

“The risks of temporizing appendicitis in pregnant women are quite grave,” he warned at a meeting of the Obstetrical and Gynecological Assembly of Southern California.

Approximately 1 in 1,000 pregnancies are complicated by appendicitis, noted Dr. Quirk. Appendectomy confirms the disease in two-thirds to three-fourths of patients.

Unfortunately, perforation is not an uncommon result of delay, with dire consequences. While fetal mortality occurs as a result of unperforated appendicitis in 3%–5% of cases, a perforated appendix is associated with the much higher fetal mortality rate of 20%–30%.

Maternal mortality, seen in approximately 0.1% of cases of unperforated appendicitis, rises precipitously to 4% with perforation.

The threshold for surgery should therefore be low, and increasingly so as the pregnancy progresses, since perforation is twice as common in the third trimester as it is in the first or second. “What you're doing is just increasing the risks … by waiting.”

And still, in part out of reluctance to operate unnecessarily, “We are loathe to make the diagnosis and a lot of surgeons are loathe to act on the diagnosis,” he said.

In fact, when special accommodations are made for physiologic changes associated with pregnancy, uncomplicated surgery and anesthesiology are not thought to be linked to adverse perinatal outcomes, said Dr. Quirk.

“In most cases, I think one can be assured that what's best for mom is best for the fetus.”

It is not surgery that poses the greatest risk, but, in the words of Dr. E.A. Babler in 1908, “[the mortality of appendicitis is] the mortality of delay.”

Uncertainty drives that delay, inasmuch as many of the classic signs and symptoms may not be present or may be confusing in the pregnant patient, and the differential diagnosis of appendicitis is long and complex. (See box.)

The location of the appendix varies during different stages of pregnancy. “What we do know is that it moves around,” he said.

Direct abdominal tenderness is a fairly reliable sign of appendicitis during pregnancy, but rebound tenderness is much less reliable, because the enlarged uterus shields the abdominal wall. Rectal tenderness is frequently absent, said Dr. Quirk.

Anorexia, present in nearly all nonpregnant patients with appendicitis, occurred in only one- to two-thirds of pregnant patients in a 1975 study from Parkland Hospital in Dallas, he noted. In early pregnancy, anorexia may be associated with morning sickness, further complicating its usefulness as a contributor to a diagnosis of appendicitis.

Dr. Quirk said a urinalysis showing many white cells but no bacteria may reinforce the diagnosis of appendicitis in a pregnant woman, because periureteritis can develop over the right ureter.

Ultrasound or spiral CT imaging may be helpful, but imaging is not always reliable. In any case, a surgical consult should be obtained immediately and the decision to operate made promptly. Also, perioperative antibiotics should be administered.

General anesthesia is generally well-tolerated in pregnancy; laparoscopy or laparotomy appear to be equally safe. The incision generally is made over the point of maximal tenderness, or at the midline if the diagnosis is seriously in doubt or if diffuse peritonitis might be present.

The table should be tilted 30 degrees to the left, and uterine manipulation minimized. Some institutions advocate external fetal monitoring.

Following surgery, Dr. Quirk recommends monitoring the uterus for contractions. The mother should ambulate early and be kept well hydrated. During rest, the patient should maintain the tilt position.

Because the diagnosis is so difficult, negative appendectomies can be expected. Acceptable rates are considered to be 25%–35% in early pregnancy and more than 40% in the second and third trimesters, “as the consequences of delay are so severe,” he said.

Differential Diagnosis

Nonobstetric Conditions

Urinary calculi

Cholelithiasis

Cholecystitis

Bowel obstruction

Gastroenteritis

Mesenteric adenitis

Colonic carcinoma

Rectus hematoma

Acute intermittent porphyria

Perforated duodenal ulcer

Pneumonia

Meckel's diverticulum

Obstetric Conditions

Preterm labor

Abruptio placentae

Chorioamnionitis

Adnexal torsion

Ectopic pregnancy

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Round ligament pain

Uteroovarian vein rupture

Carneous degeneration of myomas

Uterine rupture (placenta percreta; rudimentary horn)

Source: Dr. Quirk

PASADENA, CALIF. — The diagnosis of appendicitis can, of course, be exquisitely difficult in a nonpregnant patient. Pregnancy only makes the task more daunting.

However, the challenge must be met because early diagnosis and prompt surgery may mean the difference between life and death for both the mother and the fetus, said Dr. J. Gerald Quirk, who is professor and chairman of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive medicine at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

“The risks of temporizing appendicitis in pregnant women are quite grave,” he warned at a meeting of the Obstetrical and Gynecological Assembly of Southern California.

Approximately 1 in 1,000 pregnancies are complicated by appendicitis, noted Dr. Quirk. Appendectomy confirms the disease in two-thirds to three-fourths of patients.

Unfortunately, perforation is not an uncommon result of delay, with dire consequences. While fetal mortality occurs as a result of unperforated appendicitis in 3%–5% of cases, a perforated appendix is associated with the much higher fetal mortality rate of 20%–30%.

Maternal mortality, seen in approximately 0.1% of cases of unperforated appendicitis, rises precipitously to 4% with perforation.

The threshold for surgery should therefore be low, and increasingly so as the pregnancy progresses, since perforation is twice as common in the third trimester as it is in the first or second. “What you're doing is just increasing the risks … by waiting.”

And still, in part out of reluctance to operate unnecessarily, “We are loathe to make the diagnosis and a lot of surgeons are loathe to act on the diagnosis,” he said.

In fact, when special accommodations are made for physiologic changes associated with pregnancy, uncomplicated surgery and anesthesiology are not thought to be linked to adverse perinatal outcomes, said Dr. Quirk.

“In most cases, I think one can be assured that what's best for mom is best for the fetus.”

It is not surgery that poses the greatest risk, but, in the words of Dr. E.A. Babler in 1908, “[the mortality of appendicitis is] the mortality of delay.”

Uncertainty drives that delay, inasmuch as many of the classic signs and symptoms may not be present or may be confusing in the pregnant patient, and the differential diagnosis of appendicitis is long and complex. (See box.)

The location of the appendix varies during different stages of pregnancy. “What we do know is that it moves around,” he said.

Direct abdominal tenderness is a fairly reliable sign of appendicitis during pregnancy, but rebound tenderness is much less reliable, because the enlarged uterus shields the abdominal wall. Rectal tenderness is frequently absent, said Dr. Quirk.

Anorexia, present in nearly all nonpregnant patients with appendicitis, occurred in only one- to two-thirds of pregnant patients in a 1975 study from Parkland Hospital in Dallas, he noted. In early pregnancy, anorexia may be associated with morning sickness, further complicating its usefulness as a contributor to a diagnosis of appendicitis.

Dr. Quirk said a urinalysis showing many white cells but no bacteria may reinforce the diagnosis of appendicitis in a pregnant woman, because periureteritis can develop over the right ureter.

Ultrasound or spiral CT imaging may be helpful, but imaging is not always reliable. In any case, a surgical consult should be obtained immediately and the decision to operate made promptly. Also, perioperative antibiotics should be administered.

General anesthesia is generally well-tolerated in pregnancy; laparoscopy or laparotomy appear to be equally safe. The incision generally is made over the point of maximal tenderness, or at the midline if the diagnosis is seriously in doubt or if diffuse peritonitis might be present.

The table should be tilted 30 degrees to the left, and uterine manipulation minimized. Some institutions advocate external fetal monitoring.

Following surgery, Dr. Quirk recommends monitoring the uterus for contractions. The mother should ambulate early and be kept well hydrated. During rest, the patient should maintain the tilt position.

Because the diagnosis is so difficult, negative appendectomies can be expected. Acceptable rates are considered to be 25%–35% in early pregnancy and more than 40% in the second and third trimesters, “as the consequences of delay are so severe,” he said.

Differential Diagnosis

Nonobstetric Conditions

Urinary calculi

Cholelithiasis

Cholecystitis

Bowel obstruction

Gastroenteritis

Mesenteric adenitis

Colonic carcinoma

Rectus hematoma

Acute intermittent porphyria

Perforated duodenal ulcer

Pneumonia

Meckel's diverticulum

Obstetric Conditions

Preterm labor

Abruptio placentae

Chorioamnionitis

Adnexal torsion

Ectopic pregnancy

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Round ligament pain

Uteroovarian vein rupture

Carneous degeneration of myomas

Uterine rupture (placenta percreta; rudimentary horn)

Source: Dr. Quirk

PASADENA, CALIF. — The diagnosis of appendicitis can, of course, be exquisitely difficult in a nonpregnant patient. Pregnancy only makes the task more daunting.

However, the challenge must be met because early diagnosis and prompt surgery may mean the difference between life and death for both the mother and the fetus, said Dr. J. Gerald Quirk, who is professor and chairman of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive medicine at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

“The risks of temporizing appendicitis in pregnant women are quite grave,” he warned at a meeting of the Obstetrical and Gynecological Assembly of Southern California.

Approximately 1 in 1,000 pregnancies are complicated by appendicitis, noted Dr. Quirk. Appendectomy confirms the disease in two-thirds to three-fourths of patients.

Unfortunately, perforation is not an uncommon result of delay, with dire consequences. While fetal mortality occurs as a result of unperforated appendicitis in 3%–5% of cases, a perforated appendix is associated with the much higher fetal mortality rate of 20%–30%.

Maternal mortality, seen in approximately 0.1% of cases of unperforated appendicitis, rises precipitously to 4% with perforation.

The threshold for surgery should therefore be low, and increasingly so as the pregnancy progresses, since perforation is twice as common in the third trimester as it is in the first or second. “What you're doing is just increasing the risks … by waiting.”

And still, in part out of reluctance to operate unnecessarily, “We are loathe to make the diagnosis and a lot of surgeons are loathe to act on the diagnosis,” he said.

In fact, when special accommodations are made for physiologic changes associated with pregnancy, uncomplicated surgery and anesthesiology are not thought to be linked to adverse perinatal outcomes, said Dr. Quirk.

“In most cases, I think one can be assured that what's best for mom is best for the fetus.”

It is not surgery that poses the greatest risk, but, in the words of Dr. E.A. Babler in 1908, “[the mortality of appendicitis is] the mortality of delay.”

Uncertainty drives that delay, inasmuch as many of the classic signs and symptoms may not be present or may be confusing in the pregnant patient, and the differential diagnosis of appendicitis is long and complex. (See box.)

The location of the appendix varies during different stages of pregnancy. “What we do know is that it moves around,” he said.

Direct abdominal tenderness is a fairly reliable sign of appendicitis during pregnancy, but rebound tenderness is much less reliable, because the enlarged uterus shields the abdominal wall. Rectal tenderness is frequently absent, said Dr. Quirk.

Anorexia, present in nearly all nonpregnant patients with appendicitis, occurred in only one- to two-thirds of pregnant patients in a 1975 study from Parkland Hospital in Dallas, he noted. In early pregnancy, anorexia may be associated with morning sickness, further complicating its usefulness as a contributor to a diagnosis of appendicitis.

Dr. Quirk said a urinalysis showing many white cells but no bacteria may reinforce the diagnosis of appendicitis in a pregnant woman, because periureteritis can develop over the right ureter.

Ultrasound or spiral CT imaging may be helpful, but imaging is not always reliable. In any case, a surgical consult should be obtained immediately and the decision to operate made promptly. Also, perioperative antibiotics should be administered.

General anesthesia is generally well-tolerated in pregnancy; laparoscopy or laparotomy appear to be equally safe. The incision generally is made over the point of maximal tenderness, or at the midline if the diagnosis is seriously in doubt or if diffuse peritonitis might be present.

The table should be tilted 30 degrees to the left, and uterine manipulation minimized. Some institutions advocate external fetal monitoring.

Following surgery, Dr. Quirk recommends monitoring the uterus for contractions. The mother should ambulate early and be kept well hydrated. During rest, the patient should maintain the tilt position.

Because the diagnosis is so difficult, negative appendectomies can be expected. Acceptable rates are considered to be 25%–35% in early pregnancy and more than 40% in the second and third trimesters, “as the consequences of delay are so severe,” he said.

Differential Diagnosis

Nonobstetric Conditions

Urinary calculi

Cholelithiasis

Cholecystitis

Bowel obstruction

Gastroenteritis

Mesenteric adenitis

Colonic carcinoma

Rectus hematoma

Acute intermittent porphyria

Perforated duodenal ulcer

Pneumonia

Meckel's diverticulum

Obstetric Conditions

Preterm labor

Abruptio placentae

Chorioamnionitis

Adnexal torsion

Ectopic pregnancy

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Round ligament pain

Uteroovarian vein rupture

Carneous degeneration of myomas

Uterine rupture (placenta percreta; rudimentary horn)

Source: Dr. Quirk

Five Studies That Could Change Obstetric Practices

KAILUA KONA, HAWAII — Five studies may change the way physicians think about prolonged premature rupture of membranes, perinatal stroke in the fetus, and other topics, Dr. Michael A. Belfort said at a conference on obstetrics, gynecology, perinatal medicine, neonatology, and the law.

He delineated five areas in which obstetric practices could change because of these studies, which also included suctioning on the perineum, management of herpes in pregnancy, and vaginal birth after cesarean section.

PPROM

If a pregnant woman with prolonged premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) reaches 34 weeks' gestation, it's probably in the mother's and the baby's best interests to deliver the baby rather than continue expectant management, according to a single-institution observational study (Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;105:12–7).

The investigators studied 430 pregnancies in 1998–2000 with PPROM and 24–36 weeks' gestation to determine optimal delivery time.

Infants were delivered after reaching maturity (34 weeks or later) or after the development of chorioamnionitis, active labor, fetal compromise, or phosphatidylglycerol in vaginal pools.

Composite scores for neonatal morbidity suggested that there is limited benefit to continuing expectant management after 34 weeks in women with PPROM. Although this was not a randomized, controlled trial, physicians should seriously consider delivering these babies before 35 weeks' gestation to avoid the risk of abruption, the sudden onset of infection, or other problems, said Dr. Belfort, professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Perinatal Stroke

An analysis of data from the Kaiser Permanente system identified four major risk factors for perinatal arterial ischemic stroke (PAS), which is present in 50%–70% of fetuses with hemiplegic cerebral palsy, epilepsy, or cognitive impairment.

“Read this [report] and understand that it is possible for a baby to have a stroke in utero” even if clinicians did nothing wrong during the pregnancy or delivery, he said at the meeting sponsored by Boston University.

Two independent investigators reviewed 1,970 cases, compared them with three matched controls per case, and conducted multivariate analyses for risk factors. They found a rate of PAS of 20 per 100,000 live-born infants (JAMA 2005;293:723–9).

The four major risk factors for PAS were a history of infertility (with the risk perhaps related to the use of infertility drugs), preeclampsia, chorioamnionitis, and PPROM lasting longer than 18 hours. To defend against a lawsuit related to a bad outcome in a baby with PAS, look at the records to see if these risk factors were present, he suggested.

Trial of Labor

A 4-year observational study of 45,988 pregnant women with a prior cesarean section who underwent either a trial of labor or elective C-section answered an important question about the risks of Pitocin that had been left hanging by previous studies of vaginal births after C-section.

Inducing labor significantly increased the risk of uterine rupture and rate of perinatal complications, the investigators found (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2581–9). Keep that in mind when counseling patients, he suggested.

Suctioning

A randomized, controlled study of 2,514 infants with meconium called into question the routine intrapartum practice of oropharyngeal suctioning. “We're all trained to do that,” Dr. Belfort noted.

Routine intrapartum suctioning did not prevent meconium aspiration syndrome, and in rare cases it traumatized the nasopharynx or caused a cardiac arrythmia (Lancet 2004;364:597–602).

Recommendations for routine intrapartum suctioning should be revised, he said.

Herpes

A metaanalysis of five randomized, controlled trials involving 799 pregnant women with herpes simplex virus found that giving acyclovir therapy beginning at 36 weeks' gestation reduced herpes recurrences at delivery, viral load, symptomatic shedding, and the need for cesarean deliveries (Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;102:1396–403).

“This is hard evidence, in my mind at least, that this is the standard of care now for women with herpes,” he said.

'Read this [report] and understand that it is possible for a baby to have a stroke in utero.' DR. BELFORT

KAILUA KONA, HAWAII — Five studies may change the way physicians think about prolonged premature rupture of membranes, perinatal stroke in the fetus, and other topics, Dr. Michael A. Belfort said at a conference on obstetrics, gynecology, perinatal medicine, neonatology, and the law.

He delineated five areas in which obstetric practices could change because of these studies, which also included suctioning on the perineum, management of herpes in pregnancy, and vaginal birth after cesarean section.

PPROM

If a pregnant woman with prolonged premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) reaches 34 weeks' gestation, it's probably in the mother's and the baby's best interests to deliver the baby rather than continue expectant management, according to a single-institution observational study (Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;105:12–7).

The investigators studied 430 pregnancies in 1998–2000 with PPROM and 24–36 weeks' gestation to determine optimal delivery time.

Infants were delivered after reaching maturity (34 weeks or later) or after the development of chorioamnionitis, active labor, fetal compromise, or phosphatidylglycerol in vaginal pools.

Composite scores for neonatal morbidity suggested that there is limited benefit to continuing expectant management after 34 weeks in women with PPROM. Although this was not a randomized, controlled trial, physicians should seriously consider delivering these babies before 35 weeks' gestation to avoid the risk of abruption, the sudden onset of infection, or other problems, said Dr. Belfort, professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Perinatal Stroke

An analysis of data from the Kaiser Permanente system identified four major risk factors for perinatal arterial ischemic stroke (PAS), which is present in 50%–70% of fetuses with hemiplegic cerebral palsy, epilepsy, or cognitive impairment.

“Read this [report] and understand that it is possible for a baby to have a stroke in utero” even if clinicians did nothing wrong during the pregnancy or delivery, he said at the meeting sponsored by Boston University.

Two independent investigators reviewed 1,970 cases, compared them with three matched controls per case, and conducted multivariate analyses for risk factors. They found a rate of PAS of 20 per 100,000 live-born infants (JAMA 2005;293:723–9).

The four major risk factors for PAS were a history of infertility (with the risk perhaps related to the use of infertility drugs), preeclampsia, chorioamnionitis, and PPROM lasting longer than 18 hours. To defend against a lawsuit related to a bad outcome in a baby with PAS, look at the records to see if these risk factors were present, he suggested.

Trial of Labor

A 4-year observational study of 45,988 pregnant women with a prior cesarean section who underwent either a trial of labor or elective C-section answered an important question about the risks of Pitocin that had been left hanging by previous studies of vaginal births after C-section.

Inducing labor significantly increased the risk of uterine rupture and rate of perinatal complications, the investigators found (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2581–9). Keep that in mind when counseling patients, he suggested.

Suctioning

A randomized, controlled study of 2,514 infants with meconium called into question the routine intrapartum practice of oropharyngeal suctioning. “We're all trained to do that,” Dr. Belfort noted.

Routine intrapartum suctioning did not prevent meconium aspiration syndrome, and in rare cases it traumatized the nasopharynx or caused a cardiac arrythmia (Lancet 2004;364:597–602).

Recommendations for routine intrapartum suctioning should be revised, he said.

Herpes

A metaanalysis of five randomized, controlled trials involving 799 pregnant women with herpes simplex virus found that giving acyclovir therapy beginning at 36 weeks' gestation reduced herpes recurrences at delivery, viral load, symptomatic shedding, and the need for cesarean deliveries (Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;102:1396–403).

“This is hard evidence, in my mind at least, that this is the standard of care now for women with herpes,” he said.

'Read this [report] and understand that it is possible for a baby to have a stroke in utero.' DR. BELFORT

KAILUA KONA, HAWAII — Five studies may change the way physicians think about prolonged premature rupture of membranes, perinatal stroke in the fetus, and other topics, Dr. Michael A. Belfort said at a conference on obstetrics, gynecology, perinatal medicine, neonatology, and the law.

He delineated five areas in which obstetric practices could change because of these studies, which also included suctioning on the perineum, management of herpes in pregnancy, and vaginal birth after cesarean section.

PPROM

If a pregnant woman with prolonged premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) reaches 34 weeks' gestation, it's probably in the mother's and the baby's best interests to deliver the baby rather than continue expectant management, according to a single-institution observational study (Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;105:12–7).

The investigators studied 430 pregnancies in 1998–2000 with PPROM and 24–36 weeks' gestation to determine optimal delivery time.

Infants were delivered after reaching maturity (34 weeks or later) or after the development of chorioamnionitis, active labor, fetal compromise, or phosphatidylglycerol in vaginal pools.

Composite scores for neonatal morbidity suggested that there is limited benefit to continuing expectant management after 34 weeks in women with PPROM. Although this was not a randomized, controlled trial, physicians should seriously consider delivering these babies before 35 weeks' gestation to avoid the risk of abruption, the sudden onset of infection, or other problems, said Dr. Belfort, professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Perinatal Stroke

An analysis of data from the Kaiser Permanente system identified four major risk factors for perinatal arterial ischemic stroke (PAS), which is present in 50%–70% of fetuses with hemiplegic cerebral palsy, epilepsy, or cognitive impairment.

“Read this [report] and understand that it is possible for a baby to have a stroke in utero” even if clinicians did nothing wrong during the pregnancy or delivery, he said at the meeting sponsored by Boston University.

Two independent investigators reviewed 1,970 cases, compared them with three matched controls per case, and conducted multivariate analyses for risk factors. They found a rate of PAS of 20 per 100,000 live-born infants (JAMA 2005;293:723–9).

The four major risk factors for PAS were a history of infertility (with the risk perhaps related to the use of infertility drugs), preeclampsia, chorioamnionitis, and PPROM lasting longer than 18 hours. To defend against a lawsuit related to a bad outcome in a baby with PAS, look at the records to see if these risk factors were present, he suggested.

Trial of Labor

A 4-year observational study of 45,988 pregnant women with a prior cesarean section who underwent either a trial of labor or elective C-section answered an important question about the risks of Pitocin that had been left hanging by previous studies of vaginal births after C-section.

Inducing labor significantly increased the risk of uterine rupture and rate of perinatal complications, the investigators found (N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2581–9). Keep that in mind when counseling patients, he suggested.

Suctioning

A randomized, controlled study of 2,514 infants with meconium called into question the routine intrapartum practice of oropharyngeal suctioning. “We're all trained to do that,” Dr. Belfort noted.

Routine intrapartum suctioning did not prevent meconium aspiration syndrome, and in rare cases it traumatized the nasopharynx or caused a cardiac arrythmia (Lancet 2004;364:597–602).

Recommendations for routine intrapartum suctioning should be revised, he said.

Herpes

A metaanalysis of five randomized, controlled trials involving 799 pregnant women with herpes simplex virus found that giving acyclovir therapy beginning at 36 weeks' gestation reduced herpes recurrences at delivery, viral load, symptomatic shedding, and the need for cesarean deliveries (Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;102:1396–403).

“This is hard evidence, in my mind at least, that this is the standard of care now for women with herpes,” he said.

'Read this [report] and understand that it is possible for a baby to have a stroke in utero.' DR. BELFORT

Safe, efficient management of acute asthma

CASE Could fetal loss have been prevented?

“L.S.” is a 23-year-old gravida at 16 weeks’ gestation who is experiencing severe asthma. Prior to pregnancy, her asthma was moderate and persistent, but was well-controlled on a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid accompanied by monthly use of a short-acting beta-2 adrenergic inhaler and weekly allergy injections. When she learned she was pregnant, L.S. stopped all treatment except for the beta-2 adrenergic inhaler, which she now uses daily.

After stopping treatment, she remained stable until a viral infection developed, causing shortness of breath and wheezing that are affecting her sleep and daytime activity.

A physical examination reveals audible wheezing with nasal flaring and some retraction at the sternal notch. L.S. is treated with nebulized albuterol and ipratropium in the office, but refuses an injection of corticosteroid.

She is told to start oral steroids and advised that failure to do so will put her at increased risk for pregnancy complications, including fetal loss.

She calls later the same day from the hospital to report vaginal bleeding and continued wheezing. She is admitted and treated with intravenous steroids, nebulized beta-2 adrenergics, and oxygen, but suffers spontaneous abortion.

Many women assume “less is more” when it comes to asthma medications in pregnancy. When L.S. stopped her inhaled corticosteroid therapy, she mistakenly believed she was protecting her fetus. In actuality, it destabilized her condition and led to the pregnancy loss.

With few exceptions, the medications needed to control asthma will diminish maternal and fetal complications, and are safer—for both mother and fetus—than uncontrolled asthma.

The biggest barrier to good control of asthma during pregnancy is the fear—on the part of both physician and patient—that asthma medication may harm the fetus.1,2

This article reviews current understanding of:

- Asthma control before and during gestation

- How to prevent acute asthma in the first place

- Safe treatment of acute asthma in pregnancy

Asthma is the most common chronic disease in pregnancy

Asthma in pregnancy is not an isolated occurrence but the most common chronic disease in pregnancy. It affects almost 7% of women. About one third of gravidas with asthma experience an exacerbation during pregnancy.

If the asthma is well controlled, however, it need not increase pregnancy risks. Asthma control means:

- Minimal or no chronic symptoms day or night

- Minimal or no exacerbations

- No limitations on activities

- Maintenance of near-normal pulmonary function

- Minimal use of short-acting inhaled beta-2 agonist

- Minimal or no adverse drug effects

For best results, continue asthma treatment throughout pregnancy, and closely monitor women with severe asthma, especially around 26 weeks’ gestation, as they are more likely to experience disease exacerbation. Treatment for acute asthma is similar to therapy in nonpregnant women.

Manage asthma exacerbations aggressively. When exacerbations do occur during pregnancy despite our best efforts, aggressive management—whether at home or in the hospital—is recommended by the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1

What to do if asthma worsens

| OUTPATIENT MANAGEMENT |

Assess severity

|

Treatment

|

| EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT AND INPATIENT MANAGEMENT |

Initial assessment

|

Treatment

|

| FEV1=forced expiratory volume in the first second of pulmonary function test, PEF=peak expiratory flow. |

| SOURCE: Modified from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute15 |

How pregnancy affects asthma

Pre-pregnancy severity is key

Asthma improves in approximately one third of women, remains the same in one third, and worsens in one third. The severity of asthma prior to pregnancy correlates with the response of asthma to the pregnancy. The more severe the asthma before pregnancy, the more likely severity will increase during pregnancy.3

In rare cases, asthma presents for the first time during pregnancy.

Subsequent pregnancies are similarly affected. The changes in severity that occur in 1 pregnancy tend to recur in subsequent pregnancies.4

Some gestational ages are more problematic. The first trimester is generally well tolerated by women with asthma, with rare exacerbations. When symptoms increase, it tends to be near the start of the second trimester until about 36 weeks. Acute exacerbations are most frequent at 26 weeks.

Asthma problems are fewer and less severe during the last 4 weeks of pregnancy, even among women whose disease has worsened over the pregnancy.

Symptoms during labor and delivery are usually mild and easily controlled

Only 10% of women with well-controlled asthma experience increased symptoms during labor and delivery, and these symptoms are usually mild and easily managed. In a study of 360 patients,4 37 women were symptomatic during labor and delivery. Of these, 54% required no treatment, 15% used inhaled bronchodilators, and 5% were given intravenous (IV) aminophylline.

An 18-fold increased risk of asthma exacerbation during delivery by cesarean section was reported in another study, compared with vaginal delivery.5

Quick return to pre-pregnancy function. After delivery, most women promptly return to pre-pregnancy pulmonary function.

How asthma affects pregnancy

Prospective and retrospective studies confirm that severe or uncontrolled disease during pregnancy may result in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Maternal complications include preeclampsia (risk increases 2- to 3-fold6), gestational diabetes, preterm labor, vaginal hemorrhage, placenta previa, toxemia, and cesarean delivery.7-9 A study of 24,115 women with no history of chronic hypertension found a significant association between asthma (needing treatment) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (P<.001).7 A direct correlation was noted between severity of asthma during pregnancy and severity of maternal hypertension.

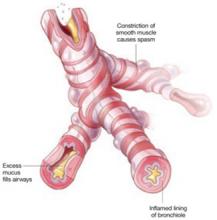

3 elements of an asthma attack

Asthma is characterized by airway obstruction and epithelial remodeling, caused by airway muscular spasm, excess mucus production, and inflammation. Bronchospasm is the hallmark of acute exacerbations, which manifest clinically as wheezing, shortness of breath, and nonproductive cough.

Greater risk of hemorrhage, drugs or no drugs

The risk of antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage increases in women with uncontrolled asthma, independent of drug usage.8 In fact, the increase in postpartum hemorrhage was most pronounced in women who did not take medication. The increased risk of hemorrhage may be related to hemostatic alterations in atopic patients, including deficient platelet aggregation, decreased platelet life span, and altered arachidonic acid metabolism.

Asthma drugs are well tolerated, but save oral steroids for acute disease

In a cohort of 817 women with asthma and 13,709 without, the only significant difference in neonatal outcome was an increased risk of hyperbilirubinemia in the infants of women taking oral steroids.10

A large multicenter study9 of perinatal outcomes in 2,123 women with asthma showed no adverse outcomes related to the use of inhaled beta-agonists, inhaled steroids, or theophylline. However, oral corticosteroid use was significantly associated with an increase in preterm births (<37 weeks) (P=.010) caused by premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, or for indicated reasons such as fetal distress, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), or preeclampsia.9 Oral corticosteroid use also was associated with low birth weight (<2,500 g) (P=.008). In addition, there was an increased cesarean delivery rate in the moderate-to-severe asthmatic group.11

No increase in congenital malformations was seen in gravidas with asthma taking a variety of medications, according to a 20-year study in Sweden.10,12 Recently, using data from the Swedish national birth registry, researchers conducted a subgroup analysis of 2,534 gravidas with first-trimester exposure to the inhaled corticosteroid budesonide, and found no increase in the rate of congenital anomalies.10,12 Based on this finding, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) changed budesonide from pregnancy category C to category B. Although other inhaled corticosteroids may be as safe, they are still classified as category C owing to a lack of clinical data. The FDA classification of several other frequently used asthma drugs is shown in TABLE 2.

Because of the increased risk of prematurity associated with oral steroids, asthma should be carefully controlled to avoid their use if at all possible. However, for severe exacerbations triggered by viral infection or other factors, oral steroids are indicated to reduce the likelihood of other, more significant risks, including death.

It is unclear whether fetal complications associated with oral steroids are a direct result of the drugs or if increased use of oral steroids is just a marker for more severe underlying asthma or exacerbation of asthma. Nevertheless, women who require oral corticosteroids should be educated about the signs and symptoms of threatened preterm delivery.

TABLE 2

Some asthma “controller” medications are safer than others

| TYPE OF DRUG | MEDICATIONS |

|---|---|

| PREGNANCY CATEGORY B | |

| Inhaled corticosteroid | Budesonide |

| Mast cell stabilizer | Cromolyn |

| Nedocromil | |

| Leukotriene modifier | Montelukast |

| Zafirlukast | |

| PREGNANCY CATEGORY C | |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | Beclomethasone |

| Fluticasone | |

| Flunisolide | |

| Triamcinolone | |

| Leukotriene modifier | Zileuton |

| Methylxanthine | Theophylline |

| Long-acting beta-agonist | Formoterol |

| Salmeterol | |

| SOURCE: Reprinted from Gluck JC, Gluck PA. Asthma controller therapy during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:369-380, © 2005 with permission from Elsevier. 17 | |

Fetal surveillance and monitoring

Fetal distress can be caused by acute or chronic maternal hypoxia from severe chronic asthma or acute exacerbations. IUGR may also be related to hypoxia, or it may be a direct result of treatment with oral steroids.13

Surveillance with nonstress testing and serial ultrasound, as well as fetal monitoring, may be necessary to check for IUGR, especially in women with severe asthma, because any hypoxemia can affect the fetus. During a severe asthma attack, continuous fetal monitoring (depending on gestational age) may be necessary.

How to control asthma

“Controller” and “reliever” drugs

Daily “controller” drugs are needed to manage inflammation in the lung; they include inhaled corticosteroids and leukotriene inhibitors.

“Reliever” medications such as beta-adrenergic inhalers act rapidly to calm exacerbations, and should be kept readily available.

Individualize allergen avoidance

Environmental allergens or lung irritants can exacerbate asthma. As many as 85% of patients with asthma also have allergies to 1 or more substances such as animals, pollens, molds, and dust mites, which can worsen symptoms. Lung irritants such as smoke, chemical fumes, and environmental pollutants can also be problematic. Finally, some drugs such as aspirin and beta-blockers can trigger acute symptoms.

An important part of treatment for these patients is identification and avoidance of asthma and allergy triggers.

Strategies include keeping pets out of the bedroom, sealing old pillows and mattresses in special encasings, removing drapes, using special filter vacuum bags while cleaning, closing the windows between 5 AM and 10 AM when pollen is highest, and limiting exposure to smoke.

Preconception immunotherapy may help

Immunotherapy is a cornerstone of maintenance therapy for asthma that cannot be controlled via avoidance strategies or medication. Identification of allergy triggers requires skin testing (scratch, patch, or intradermal). Starting with minute amounts of allergen extracts, regular injections with increasing doses are given to stimulate a protective, specific immune response.

Because it takes several months for the treatments to take full effect, and because there is a greater risk of adverse reactions with increasing doses, this therapy should not be initiated during pregnancy. However, it can be carefully continued during pregnancy in women who are already benefiting from it and not experiencing adverse reactions.

If a woman is in the “build-up” phase of immunotherapy when she conceives, continue treatment without increasing the allergen dose.14

Treatment recommendations

Treatment guidelines generally categorize asthma according to severity (TABLE 3).15 While these guidelines assist in decision-making, each patient should receive an individualized treatment plan. Severity of the disease is based on clinical signs and symptoms as well as pulmonary function, as measured by FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in the first second of a pulmonary function test). This classification system is helpful in deciding how well asthma is controlled and also in following response to treatment.

Choice of the appropriate medications to control asthma during pregnancy is critical for the best maternal and fetal outcomes (TABLE 3).

No daily medication is needed in women with mild asthma.

Women with mild asthma whose day-time symptoms occur less than daily and whose nighttime symptoms occur less than weekly, often have fewer symptoms during pregnancy.

The tipping point. If the patient is using an entire canister of short-acting inhaled beta-agonist in a month, her disease control is inadequate. This is the point at which therapy should be increased to include long-term control medications, such as daily inhaled corticosteroids or leukotriene inhibitors (TABLE 3).

The most severe asthma, characterized by frequent daytime and nighttime symptoms, is more likely to become exacerbated during pregnancy. These women require careful monitoring to ensure that their medications are prescribed at adequate levels.

TABLE 3

How to determine severity—and treat accordingly

| SEVERITY | SYMPTOMS | PEAK FLOW (OR FEV1) | TREATMENT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAY | NIGHT | |||

| Mild Intermittent | ≤2/week | ≤2/month | ≥80% | No daily medication needed. |

| ACUTE SYMPTOMS Beta-2 adrenergic inhaler | ||||

| IF EXACERBATION IS UNABATED Systemic corticosteroids | ||||

| Mild Persistent | >2/week | >2/month | ≥80% | MAINTENANCE Low-dose inhaled corticosteroid |

| ALTERNATIVE MAINTENANCE Cromolyn, | ||||

| Leukotriene receptor antagonist, or | ||||

| Theophylline (5–12 μg/mL serum level). | ||||

| ACUTE SYMPTOMS Beta-2 adrenergic inhaler | ||||

| IF NOT IMPROVED Systemic corticosteroids | ||||

| Moderate Persistent | Daily | >1/week | >60% to <80% | Low-dose inhaled corticosteroid and |

| Long-acting inhaled beta-2 agonist or | ||||

| Medium-dose inhaled corticosteroid. | ||||

| ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT | ||||

| Low-dose inhaled corticosteroid and | ||||

| Theophylline or leukotriene antagonist | ||||

| Severe Persistent | Continual | Frequent | <60% | High-dose inhaled corticosteroid and |

| Long-acting inhaled beta-2 agonist. | ||||

| ACUTE SYMPTOMS | ||||

| Beta-2 adrenergic inhaler (short acting) and | ||||

| Systemic corticosteroids (2 mg/kg/day, not to exceed 60 mg/day). | ||||

| FEV1=forced expiratory volume in the first second of pulmonary function test. | ||||

| SOURCE: Modified from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute15 | ||||

Back off as asthma is controlled

Review treatment every 1 to 3 months; gradual stepwise reduction in treatment may be possible. The goal is to use the least medication necessary to maintain good control of symptoms.

General principles

- Maintain pulmonary function to adequately oxygenate the fetus.

- Prevent acute exacerbation.

- Intervene promptly when treating acute exacerbation and associated conditions such as rhinitis, sinusitis, and gastroesophageal reflux (TABLE 1).

- Prescribe daily anti-inflammatory therapy for persistent asthma.

Recommendations from ACOG and ACAAI

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology also offer specific recommendations,16 which include:

- Avoid zileuton (Zyflo), which causes adverse fetal effects in animals and lacks human data

- Give the leukotriene modifiers montelukast (Singulair) or zafirlukast (Accolate) if the patient had a good pre-pregnancy response to these drugs

- Budesonide (Rhinocort) is a good choice for high-dose inhaled corticosteroid and is now classified as a category B drug

- Drugs to be avoided: alpha-adrenergic medications (except pseudoephedrine), iodides, tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and epinephrine (except for a life-threatening event)

In addition, we make sure:

- Every woman with asthma of any severity has a beta-adrenergic short-acting (bronchodilator) inhaler as a “rescue” treatment and knows when and how to use it.

- Women with persistent asthma have an action plan, and, in some cases, a peak-flow meter at home.

- Every patient with asthma has oral prednisone at home, with instructions to start it immediately in the event of an exacerbation unresponsive to bronchodilators and other measures in the action plan.

- Finally, we reassure gravidas that their asthma drugs will provide more benefit than harm to the fetus, compared with uncontrolled asthma.

Overcoming reluctance to treat

The reluctance to treat gravidas with asthma can be difficult to overcome, even with the proper assurance and education. Effective management requires a team effort, with communication between the allergist, obstetrician, and patient. Compliance will improve if women of childbearing age are treated with asthma drugs that can be safely continued during pregnancy.

At the first prenatal visit, reassure the patient that, in most cases, it is safer for her and her baby to control the asthma than to discontinue therapy. Every visit should include assessment of maternal asthma, and there should be a consultation with the allergist/pulmonologist whenever needed. Overall, helping a pregnant woman maintain control of her asthma and improve obstetric outcomes is easy—a matter of paying attention to the right details.

1. Cydulka RK, Emerman CL, Schreiber D, Molander KH, Woodruff PG, Camargo CA, Jr. Acute asthma among pregnant women presenting to the emergency department. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:887-892.

2. Otsuka H, Narushima M, Suzuki H. Assessment of inhaled corticosteroid therapy for asthma treatment during pregnancy. Allergology Int. 2005;54:381-386.

3. Gluck JC, Gluck PA. The effects of pregnancy on asthma: a prospective study. Ann Allergy. 1976;37:164-168.

4. Schatz M, Harden K, Forsythe A, et al. The course of asthma during pregnancy, post partum, and with successive pregnancies: a prospective analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988;81:509-517.

5. Mabie WC, Barton JR, Wasserstrum N, et al. Clinical observations on asthma in pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Med. 1992;1:45-50.

6. Beck SA. Asthma in the female: hormonal effect and pregnancy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2001;22:1-4.

7. Lehrer S, Stone J, Lapinski R, et al. Association between pregnancy-induced hypertension and asthma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1463-1466.

8. Alexander S, Dodds L, Armson BA. Perinatal outcomes in women with asthma during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:435-440.

9. Schatz M, Dombrowski M, Wise R, et al, for the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network, The National Institute of Child Health and Development; The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The relationship of asthma medication use to perinatal outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1040-1045.

10. Ericson A, Kallen B. Use of drugs during pregnancy-unique Swedish registration method that can be improved. Swedish Medical Products Agency. 1999;1:8-11.

11. Dombrowski MP, Schatz M, Wise R, et al, for the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Asthma during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:5-12.

12. Kallen B, Rydhstroem H, Aberg A. Asthma during pregnancy: a population based study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;16:167-171.

13. Stenius-Aarniala B, Piirila P, Teramo K. Asthma and pregnancy: a prospective study of 198 pregnancies. Thorax. 1988;43:12-18.

14. Metzger WJ, Turner E, Patterson R. The safety of immunotherapy during pregnancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1978;61:268-272.

15. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Asthma and Pregnancy Working Group. NAEPP expert panel report. Managing asthma during pregnancy: recommendations for pharmacologic treatment-2004 update [published correction appears in J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:477]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:34-46.

16. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and The American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI). Position statement: The use of newer asthma and allergy medications during pregnancy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;84:475-480.

17. Gluck JC, Gluck PA. Asthma controller therapy during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:369-380.

Both authors receive grant/research support from Astra Zeneca. In addition, Dr. Joan Gluck receives grant/research support from Sepracor.

CASE Could fetal loss have been prevented?

“L.S.” is a 23-year-old gravida at 16 weeks’ gestation who is experiencing severe asthma. Prior to pregnancy, her asthma was moderate and persistent, but was well-controlled on a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid accompanied by monthly use of a short-acting beta-2 adrenergic inhaler and weekly allergy injections. When she learned she was pregnant, L.S. stopped all treatment except for the beta-2 adrenergic inhaler, which she now uses daily.

After stopping treatment, she remained stable until a viral infection developed, causing shortness of breath and wheezing that are affecting her sleep and daytime activity.

A physical examination reveals audible wheezing with nasal flaring and some retraction at the sternal notch. L.S. is treated with nebulized albuterol and ipratropium in the office, but refuses an injection of corticosteroid.

She is told to start oral steroids and advised that failure to do so will put her at increased risk for pregnancy complications, including fetal loss.

She calls later the same day from the hospital to report vaginal bleeding and continued wheezing. She is admitted and treated with intravenous steroids, nebulized beta-2 adrenergics, and oxygen, but suffers spontaneous abortion.

Many women assume “less is more” when it comes to asthma medications in pregnancy. When L.S. stopped her inhaled corticosteroid therapy, she mistakenly believed she was protecting her fetus. In actuality, it destabilized her condition and led to the pregnancy loss.

With few exceptions, the medications needed to control asthma will diminish maternal and fetal complications, and are safer—for both mother and fetus—than uncontrolled asthma.

The biggest barrier to good control of asthma during pregnancy is the fear—on the part of both physician and patient—that asthma medication may harm the fetus.1,2

This article reviews current understanding of:

- Asthma control before and during gestation

- How to prevent acute asthma in the first place

- Safe treatment of acute asthma in pregnancy

Asthma is the most common chronic disease in pregnancy

Asthma in pregnancy is not an isolated occurrence but the most common chronic disease in pregnancy. It affects almost 7% of women. About one third of gravidas with asthma experience an exacerbation during pregnancy.

If the asthma is well controlled, however, it need not increase pregnancy risks. Asthma control means:

- Minimal or no chronic symptoms day or night

- Minimal or no exacerbations

- No limitations on activities

- Maintenance of near-normal pulmonary function

- Minimal use of short-acting inhaled beta-2 agonist

- Minimal or no adverse drug effects

For best results, continue asthma treatment throughout pregnancy, and closely monitor women with severe asthma, especially around 26 weeks’ gestation, as they are more likely to experience disease exacerbation. Treatment for acute asthma is similar to therapy in nonpregnant women.

Manage asthma exacerbations aggressively. When exacerbations do occur during pregnancy despite our best efforts, aggressive management—whether at home or in the hospital—is recommended by the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1

What to do if asthma worsens

| OUTPATIENT MANAGEMENT |

Assess severity

|

Treatment

|

| EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT AND INPATIENT MANAGEMENT |

Initial assessment

|

Treatment

|

| FEV1=forced expiratory volume in the first second of pulmonary function test, PEF=peak expiratory flow. |

| SOURCE: Modified from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute15 |

How pregnancy affects asthma

Pre-pregnancy severity is key

Asthma improves in approximately one third of women, remains the same in one third, and worsens in one third. The severity of asthma prior to pregnancy correlates with the response of asthma to the pregnancy. The more severe the asthma before pregnancy, the more likely severity will increase during pregnancy.3

In rare cases, asthma presents for the first time during pregnancy.

Subsequent pregnancies are similarly affected. The changes in severity that occur in 1 pregnancy tend to recur in subsequent pregnancies.4

Some gestational ages are more problematic. The first trimester is generally well tolerated by women with asthma, with rare exacerbations. When symptoms increase, it tends to be near the start of the second trimester until about 36 weeks. Acute exacerbations are most frequent at 26 weeks.

Asthma problems are fewer and less severe during the last 4 weeks of pregnancy, even among women whose disease has worsened over the pregnancy.

Symptoms during labor and delivery are usually mild and easily controlled

Only 10% of women with well-controlled asthma experience increased symptoms during labor and delivery, and these symptoms are usually mild and easily managed. In a study of 360 patients,4 37 women were symptomatic during labor and delivery. Of these, 54% required no treatment, 15% used inhaled bronchodilators, and 5% were given intravenous (IV) aminophylline.

An 18-fold increased risk of asthma exacerbation during delivery by cesarean section was reported in another study, compared with vaginal delivery.5

Quick return to pre-pregnancy function. After delivery, most women promptly return to pre-pregnancy pulmonary function.

How asthma affects pregnancy

Prospective and retrospective studies confirm that severe or uncontrolled disease during pregnancy may result in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Maternal complications include preeclampsia (risk increases 2- to 3-fold6), gestational diabetes, preterm labor, vaginal hemorrhage, placenta previa, toxemia, and cesarean delivery.7-9 A study of 24,115 women with no history of chronic hypertension found a significant association between asthma (needing treatment) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (P<.001).7 A direct correlation was noted between severity of asthma during pregnancy and severity of maternal hypertension.

3 elements of an asthma attack

Asthma is characterized by airway obstruction and epithelial remodeling, caused by airway muscular spasm, excess mucus production, and inflammation. Bronchospasm is the hallmark of acute exacerbations, which manifest clinically as wheezing, shortness of breath, and nonproductive cough.

Greater risk of hemorrhage, drugs or no drugs

The risk of antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage increases in women with uncontrolled asthma, independent of drug usage.8 In fact, the increase in postpartum hemorrhage was most pronounced in women who did not take medication. The increased risk of hemorrhage may be related to hemostatic alterations in atopic patients, including deficient platelet aggregation, decreased platelet life span, and altered arachidonic acid metabolism.

Asthma drugs are well tolerated, but save oral steroids for acute disease

In a cohort of 817 women with asthma and 13,709 without, the only significant difference in neonatal outcome was an increased risk of hyperbilirubinemia in the infants of women taking oral steroids.10

A large multicenter study9 of perinatal outcomes in 2,123 women with asthma showed no adverse outcomes related to the use of inhaled beta-agonists, inhaled steroids, or theophylline. However, oral corticosteroid use was significantly associated with an increase in preterm births (<37 weeks) (P=.010) caused by premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, or for indicated reasons such as fetal distress, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), or preeclampsia.9 Oral corticosteroid use also was associated with low birth weight (<2,500 g) (P=.008). In addition, there was an increased cesarean delivery rate in the moderate-to-severe asthmatic group.11

No increase in congenital malformations was seen in gravidas with asthma taking a variety of medications, according to a 20-year study in Sweden.10,12 Recently, using data from the Swedish national birth registry, researchers conducted a subgroup analysis of 2,534 gravidas with first-trimester exposure to the inhaled corticosteroid budesonide, and found no increase in the rate of congenital anomalies.10,12 Based on this finding, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) changed budesonide from pregnancy category C to category B. Although other inhaled corticosteroids may be as safe, they are still classified as category C owing to a lack of clinical data. The FDA classification of several other frequently used asthma drugs is shown in TABLE 2.

Because of the increased risk of prematurity associated with oral steroids, asthma should be carefully controlled to avoid their use if at all possible. However, for severe exacerbations triggered by viral infection or other factors, oral steroids are indicated to reduce the likelihood of other, more significant risks, including death.

It is unclear whether fetal complications associated with oral steroids are a direct result of the drugs or if increased use of oral steroids is just a marker for more severe underlying asthma or exacerbation of asthma. Nevertheless, women who require oral corticosteroids should be educated about the signs and symptoms of threatened preterm delivery.

TABLE 2

Some asthma “controller” medications are safer than others

| TYPE OF DRUG | MEDICATIONS |

|---|---|

| PREGNANCY CATEGORY B | |

| Inhaled corticosteroid | Budesonide |

| Mast cell stabilizer | Cromolyn |

| Nedocromil | |

| Leukotriene modifier | Montelukast |

| Zafirlukast | |

| PREGNANCY CATEGORY C | |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | Beclomethasone |

| Fluticasone | |

| Flunisolide | |

| Triamcinolone | |

| Leukotriene modifier | Zileuton |

| Methylxanthine | Theophylline |

| Long-acting beta-agonist | Formoterol |

| Salmeterol | |

| SOURCE: Reprinted from Gluck JC, Gluck PA. Asthma controller therapy during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:369-380, © 2005 with permission from Elsevier. 17 | |

Fetal surveillance and monitoring

Fetal distress can be caused by acute or chronic maternal hypoxia from severe chronic asthma or acute exacerbations. IUGR may also be related to hypoxia, or it may be a direct result of treatment with oral steroids.13

Surveillance with nonstress testing and serial ultrasound, as well as fetal monitoring, may be necessary to check for IUGR, especially in women with severe asthma, because any hypoxemia can affect the fetus. During a severe asthma attack, continuous fetal monitoring (depending on gestational age) may be necessary.

How to control asthma

“Controller” and “reliever” drugs

Daily “controller” drugs are needed to manage inflammation in the lung; they include inhaled corticosteroids and leukotriene inhibitors.

“Reliever” medications such as beta-adrenergic inhalers act rapidly to calm exacerbations, and should be kept readily available.

Individualize allergen avoidance

Environmental allergens or lung irritants can exacerbate asthma. As many as 85% of patients with asthma also have allergies to 1 or more substances such as animals, pollens, molds, and dust mites, which can worsen symptoms. Lung irritants such as smoke, chemical fumes, and environmental pollutants can also be problematic. Finally, some drugs such as aspirin and beta-blockers can trigger acute symptoms.

An important part of treatment for these patients is identification and avoidance of asthma and allergy triggers.

Strategies include keeping pets out of the bedroom, sealing old pillows and mattresses in special encasings, removing drapes, using special filter vacuum bags while cleaning, closing the windows between 5 AM and 10 AM when pollen is highest, and limiting exposure to smoke.

Preconception immunotherapy may help

Immunotherapy is a cornerstone of maintenance therapy for asthma that cannot be controlled via avoidance strategies or medication. Identification of allergy triggers requires skin testing (scratch, patch, or intradermal). Starting with minute amounts of allergen extracts, regular injections with increasing doses are given to stimulate a protective, specific immune response.

Because it takes several months for the treatments to take full effect, and because there is a greater risk of adverse reactions with increasing doses, this therapy should not be initiated during pregnancy. However, it can be carefully continued during pregnancy in women who are already benefiting from it and not experiencing adverse reactions.

If a woman is in the “build-up” phase of immunotherapy when she conceives, continue treatment without increasing the allergen dose.14

Treatment recommendations

Treatment guidelines generally categorize asthma according to severity (TABLE 3).15 While these guidelines assist in decision-making, each patient should receive an individualized treatment plan. Severity of the disease is based on clinical signs and symptoms as well as pulmonary function, as measured by FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in the first second of a pulmonary function test). This classification system is helpful in deciding how well asthma is controlled and also in following response to treatment.

Choice of the appropriate medications to control asthma during pregnancy is critical for the best maternal and fetal outcomes (TABLE 3).

No daily medication is needed in women with mild asthma.

Women with mild asthma whose day-time symptoms occur less than daily and whose nighttime symptoms occur less than weekly, often have fewer symptoms during pregnancy.

The tipping point. If the patient is using an entire canister of short-acting inhaled beta-agonist in a month, her disease control is inadequate. This is the point at which therapy should be increased to include long-term control medications, such as daily inhaled corticosteroids or leukotriene inhibitors (TABLE 3).

The most severe asthma, characterized by frequent daytime and nighttime symptoms, is more likely to become exacerbated during pregnancy. These women require careful monitoring to ensure that their medications are prescribed at adequate levels.

TABLE 3

How to determine severity—and treat accordingly

| SEVERITY | SYMPTOMS | PEAK FLOW (OR FEV1) | TREATMENT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAY | NIGHT | |||

| Mild Intermittent | ≤2/week | ≤2/month | ≥80% | No daily medication needed. |

| ACUTE SYMPTOMS Beta-2 adrenergic inhaler | ||||

| IF EXACERBATION IS UNABATED Systemic corticosteroids | ||||

| Mild Persistent | >2/week | >2/month | ≥80% | MAINTENANCE Low-dose inhaled corticosteroid |

| ALTERNATIVE MAINTENANCE Cromolyn, | ||||

| Leukotriene receptor antagonist, or | ||||

| Theophylline (5–12 μg/mL serum level). | ||||

| ACUTE SYMPTOMS Beta-2 adrenergic inhaler | ||||

| IF NOT IMPROVED Systemic corticosteroids | ||||

| Moderate Persistent | Daily | >1/week | >60% to <80% | Low-dose inhaled corticosteroid and |

| Long-acting inhaled beta-2 agonist or | ||||

| Medium-dose inhaled corticosteroid. | ||||

| ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT | ||||

| Low-dose inhaled corticosteroid and | ||||

| Theophylline or leukotriene antagonist | ||||

| Severe Persistent | Continual | Frequent | <60% | High-dose inhaled corticosteroid and |

| Long-acting inhaled beta-2 agonist. | ||||

| ACUTE SYMPTOMS | ||||

| Beta-2 adrenergic inhaler (short acting) and | ||||

| Systemic corticosteroids (2 mg/kg/day, not to exceed 60 mg/day). | ||||

| FEV1=forced expiratory volume in the first second of pulmonary function test. | ||||

| SOURCE: Modified from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute15 | ||||

Back off as asthma is controlled

Review treatment every 1 to 3 months; gradual stepwise reduction in treatment may be possible. The goal is to use the least medication necessary to maintain good control of symptoms.

General principles

- Maintain pulmonary function to adequately oxygenate the fetus.

- Prevent acute exacerbation.

- Intervene promptly when treating acute exacerbation and associated conditions such as rhinitis, sinusitis, and gastroesophageal reflux (TABLE 1).

- Prescribe daily anti-inflammatory therapy for persistent asthma.

Recommendations from ACOG and ACAAI