User login

Management of the hospitalized ulcerative colitis patient: A primer for the initial approach to care for the practicing gastroenterologist

Introduction

Inpatient management of acute ulcerative colitis (UC) flares can be challenging because of the multiple patient and disease-related factors influencing therapeutic decision making. The clinical course during the first 24-72 hours of the hospitalization will likely guide the decision between rescue medical and surgical therapy. Using available evidence from clinical practice guidelines, we present a day-by-day guide to managing most hospitalized UC patients.

Day 0 – The emergency department (ED)

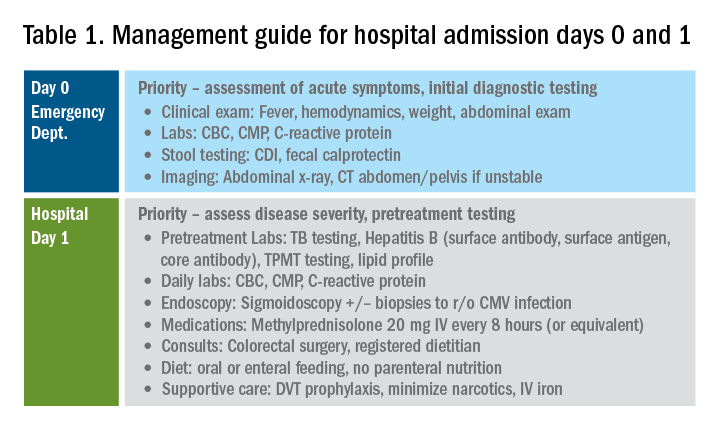

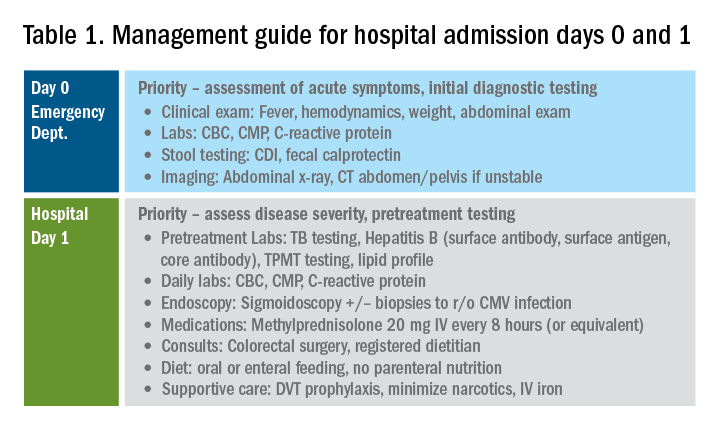

When an UC patient presents to the ED for evaluation, the initial assessments should focus on the acuity and severity of the flare. Key clinical features of disease severity include the presence of fever, tachycardia, hypotension, or weight loss in addition to worsened gastrointestinal symptoms of stool frequency relative to baseline, rectal bleeding, and abdominal pain. Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is often defined using the modified Truelove and Witts criteria.1 A patient meets criteria for ASUC if they have at least six bloody stools per day and at least one sign of systemic toxicity, such as heart rate greater than 90 bpm, temperature at or above 37.8° C, hemoglobin level below 10.5 g/dL, or elevated inflammatory markers.

Initial laboratory assessments should include complete blood counts to identify anemia, potential superimposed infection, or toxicity and a comprehensive metabolic profile to evaluate for dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, hepatic injury or hypoalbuminemia (an important predictor of surgery), as well as assessment of response to treatment and readmission.2,3 An evaluation at admission of C-reactive protein (CRP) is crucial because changes from the initial value will determine steroid response and predict need for surgical intervention or rescue therapy. A baseline fecal calprotectin can serve as a noninvasive marker that can be followed after discharge to monitor response to therapy.

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) must be ruled out in all patients presenting with ASUC regardless of history of antibiotic use or prior negative testing. Concomitant UC and CDI are associated with a four- to sixfold increased risk of in-hospital mortality and a two- to sixfold increased risk of bowel surgery.4-6 Immunoassay testing is inexpensive and fast with a high specificity but has low sensitivity; nucleic acid amplification testing with polymerase chain reaction has a high sensitivity and specificity.7 Knowing which testing algorithm the hospital lab uses helps guide interpretation of results.

For patients meeting criteria for ASUC, obtaining at least an abdominal x-ray is important to assess for colonic dilation to further stratify the patient by risk. Colonic dilation, defined as a transverse colon diameter greater than 5.5 cm, places the patient in the category of fulminant colitis and colorectal surgical consultation should be obtained.8 A CT scan is often ordered first because it can provide a rapid assessment of intra-abdominal processes but is not routinely needed unless hemodynamic instability, an acute abdomen, or markedly abnormal laboratory testing (specifically white blood cell count with bandemia) is present as these can be indicators of toxic megacolon or perforation.8-10

Day 1 – Assess disease severity and assemble the team

Obtaining a thorough clinical history is essential to classify disease severity and identify potential triggers for the acute exacerbation. Potential triggers may include infections, new medications, recent antibiotic use, recent travel, sick contacts, or cessation of treatments. Standard questions include asking about the timing of onset of symptoms, bowel movements during a 24-hour period, and particularly the presence of nocturnal bowel movements. If patients report bloody stools, inquire how often they see blood relative to the total number of bowel movements. The presence and nature of abdominal pain should be elicited, particularly changes in abdominal pain and comparison with previous disease flares. These clinical parameters are used to assess response to treatment; therefore, ask patients to keep a log of their stool frequency, consistency, rectal urgency, and bleeding each day to report to the team during daily rounds.

For patients with ASUC, a full colonoscopy is rarely indicated in the inpatient setting because it is unlikely to change management and poses a risk of perforation.11 However, a sigmoidoscopy within the first 24 hours of admission will provide useful information about the endoscopic disease activity, particularly if features such as deep or well-like ulcers, large mucosal abrasions, or extensive loss of the mucosal layer are present because these are predictors of colectomy.8 Tissue biopsies can exclude cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, an important consideration for patients on immunosuppression including corticosteroids.12-16

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis is extremely important for hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. At baseline, IBD patients have a threefold higher risk of VTE than do non-IBD patients, which increases to approximately sixfold during flares.17 Pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis is recommended for all hospitalized IBD patients, even those with rectal bleeding. This may seem counterintuitive in the setting of “GI bleeding,” so it is important to counsel both patients and team members regarding VTE risks and the role of the prophylactic regimen to ensure adherence. Mechanical VTE prophylaxis can be used in patients with severe bleeding and hemodynamic instability until pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis can be safely initiated.17

Narcotics should be used sparingly for hospitalized IBD patients. Narcotic use is associated with greater likelihood of subsequent IBD hospitalizations, ED visits, and higher costs of health care for patients with IBD.18 Heavy use of opiates, defined as continuous use for more than 30 days at a dose exceeding 50 mg morphine per day or equivalent, was strongly associated with an increased overall mortality in IBD patients.19 Opiates also slow bowel motility and precipitate toxic megacolon, along with any other agent that slows bowel motility, such as anticholinergic medications.8 These agents may also mask bowel frequency symptoms that would otherwise indicate a failure of medical therapy. Similarly, use of NSAIDS should also be avoided because these have been associated with disease relapse and escalating intestinal inflammation.20

Once disease severity has been determined, intravenous corticosteroid therapy may be initiated, ideally once CDI and CMV have been excluded. The recommended dosing of intravenous corticosteroids is methylprednisolone 20 mg IV every 8 hours or equivalent. There is no evidence to support additional benefit for doses exceeding these amounts.8 Prior to starting parenteral corticosteroids, it is important to keep in mind the possible need for rescue therapy during the admission. Recommended testing includes hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody, hepatitis B core antibody and tuberculosis testing if there is no documented negative testing within the past 6-12 months. These labs should be drawn prior to steroid treatment to avoid delays in care and indeterminate results. Finally, a lipid profile is recommended for patients who may be cyclosporine candidates pending response to intravenous corticosteroids. Unless the patient has been admitted with a bowel obstruction, which should raise the suspicion that the diagnosis is actually Crohn’s disease, enteral feeding is preferred for UC patients even if they may have significant food aversion. The early involvement of a registered dietitian is valuable to guide dietary choices and recommend appropriate enteral nutrition supplements. During acute flares, patients may find a low-residue diet to be less stimulating to their gut while their acute flare is being treated. Electrolyte abnormalities should be repleted and consistently monitored during the hospitalization. Providing parenteral intravenous iron for anemic patients will expedite correction of the anemia alongside treatment of the underlying UC.

Most UC patients admitted to the hospital will require a multidisciplinary approach with gastroenterologists, surgeons, radiologists, dietitians, and case coordinators/social workers, among others. It is essential to assemble the team, especially the surgeons, earlier during the hospitalization rather than later. It is especially important to discuss the role of the surgeon in the management of UC and explain why the surgeon is being consulted in the context of the patient’s acute presentation. Being transparent about the parameters the GI team are monitoring to determine if and when surgery is the most appropriate and safe approach will improve patients’ acceptance of the surgical team’s role in their care. Specific indications for surgery in ASUC include toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, severe refractory hemorrhage, and failure to respond to medical therapy (Table 1).8

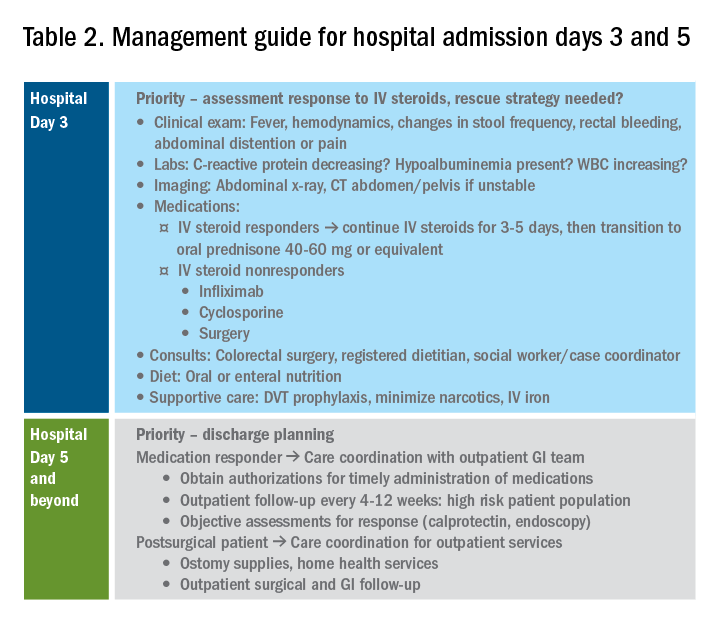

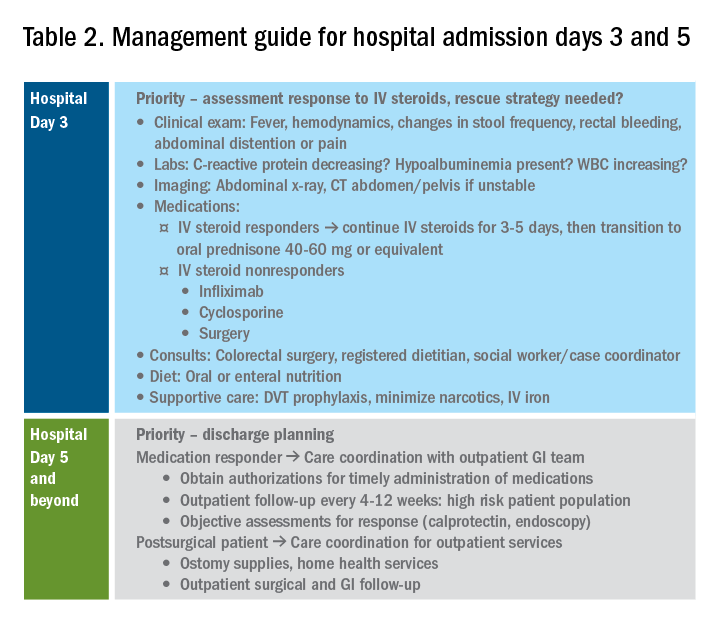

Day 3 – Assessing response to corticosteroids

In addition to daily symptom assessments, a careful abdominal exam should be performed every day with the understanding that steroids (and also narcotics) may mask perforation or pain. Any abrupt decrease or cessation of bowel movements, increasing abdominal distention, or a sudden increase in abdominal pain or tenderness may require abdominal imaging to ensure no interim perforation or severe colonic dilation has occurred while receiving steroid therapy. In these circumstances, the addition of broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be considered, particularly if hemodynamic instability (such as tachycardia) is present.

Patients should be assessed for response to intravenous steroid therapy after 3 days of treatment. A meaningful response to corticosteroids is present if the patient has had more than 50% improvement in symptoms, particularly rectal bleeding and stool frequency. A more than 75% improvement in CRP should also be noted from admission to day 3 with an overall trend of improvement.2,21 Additionally, patients should be afebrile, require minimal to no narcotic usage, tolerating oral intake, and be ambulatory. If the patient has met all these parameters, it is reasonable to transition to oral corticosteroids, such as prednisone 40-60 mg daily after a course of 3-5 days of intravenous corticosteroids. Ideally, patients should be observed for 24-48 hours in the hospital after transitioning to oral corticosteroids to make sure that symptoms do not worsen with the switch.

Patients with more than eight bowel movements per day, CRP greater than 4.5 g/dL, deep ulcers on endoscopy, or albumin less than 3.0 g/dL have a higher likelihood of failing intravenous corticosteroid therapy, and these patients should be prepared for rescue therapy.2,21 A patient has failed intravenous corticosteroids by day 3 if they have sustained fever in the absence of an infection, continued CRP elevation or lack of CRP decrease, or ongoing high stool frequency, bleeding, and pain with less than 50% improvement from baseline on admission.8 In the setting of nonresponse to intravenous corticosteroids, it is prudent to involve colorectal surgery to discuss colectomy as an option of equal merit to medical salvage therapies such as infliximab or cyclosporine.

Infliximab is the most readily available rescue therapy for steroid-refractory patients and has been shown to increase colectomy-free survival in patients with ASUC.8 However, patients with the same predictors for intravenous steroid failures (low albumin, high CRP, and/or deep ulcers on endoscopy) are also at the highest risk for infliximab nonresponse. These factors are important to discuss with the patients and colorectal surgery teams when providing the options of treatment strategy, particularly with medication dosing. ASUC with more severe disease biochemically (low albumin, elevated CRP, possibly bandemia) benefit from a higher dose of infliximab at 10 mg/kg, given the likelihood of increased drug clearance in this situation.22,23

From a practical standpoint, it is important to confirm the patient’s insurance status prior to medication administration to make sure therapy can be continued after hospital discharge. Early involvement of the social workers and case coordinators is key to ensuring timely administration of the next dose of treatment. Patients who receive infliximab rescue therapy should be monitored for an additional 1-2 days after administration to ensure they are responding to this therapy with continued monitoring of CRP and symptoms during this period. If there is no response at this point, an additional dose of infliximab may be considered but surgery should not be delayed if there is no meaningful response after the first dose.

Another option for intravenous corticosteroid nonresponders is intravenous cyclosporine because treatment failure rates for cyclosporine and infliximab were similar in head-to-head studies.24 However, patient selection is key to successful utilization of this agent. Unlike infliximab, cyclosporine is primarily an induction agent for steroid nonresponders rather than a maintenance strategy. Therefore, in patients in whom cyclosporine is being considered, thiopurines or vedolizumab are potential options for maintenance therapy. If the patient has poor renal function, low cholesterol, advanced age, significant comorbidities, or a history of nonadherence to therapy, cyclosporine should not be given. Additionally, clinical experience with intravenous cyclosporine administration and monitoring both during inpatient and outpatient care settings should be factored into the decision making for infliximab versus cyclosporine.8

Day 5 and beyond – Discharge planning

Patients who have responded to the initial intravenous steroid course by hospital day 5 should have successfully transitioned to oral steroids with plans to start an appropriate steroid-sparing therapy shortly after discharge. Treatment planning should commence prior to discharge and should be communicated with the outpatient GI team to ensure a smooth transition to the ambulatory care setting, primarily to begin insurance authorizations as soon as possible. If the patient has had a meaningful response to infliximab rescue therapy (improvement by more than 50% in bowel frequency, amount of blood, abdominal pain), discharge planning needs to prioritize obtaining authorization for the second dose within 2 weeks of the initial infusion. These patients are high risk for readmission, and close outpatient follow-up by the ambulatory GI care team is necessary to help direct the tapering of steroids and monitor response to treatment.

If the patient has not responded to intravenous steroid therapy, infliximab, or cyclosporine by day 5-7, then surgery should be strongly considered. Delaying surgery may worsen outcomes as patients become more malnourished, anemic, and continue to receive intravenous steroids. Additional preoperative optimization may be required depending on the patient’s course up to this point (Table 2).

Summary

The cornerstones of inpatient UC management center on a thorough initial evaluation including imaging and endoscopy as appropriate, establishment of baseline parameters, and daily assessment of response to therapy through a combination of patient-reported outcomes and biomarkers of inflammation. With this strategy in mind, practitioners and care teams can manage these complex patients using a consistent strategy focusing on multidisciplinary, evidence-based care.

References

1. Truelove SC et al. Br Med J. 1955 Oct 23;2(4947):1041-8.

2. Ho GT et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004 May 15;19(10):1079-87.

3. Tinsley A et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(9):1103-9.

4. Issa M et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Mar;5(3):345-51.

5. Ananthakrishnan AN et al. Gut. 2008 Feb;57(2):205-10.

6. Negron ME et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 May;111(5):691-704.

7. Taylor KN et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Feb;144(2):428-37.

8. Rubin DT et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Mar;114(3):384-413.

9. Jalan KN et al. Gastroenterology. 1969 Jul;57(1):68-82.

10. Gan SI et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Nov;98(11):2363-71.

11. Makkar R et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013 Sep;9(9):573-83.

12. Hindryckx P et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Nov;13(11):654-64.

13. Yerushalmy-Feler A et al. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2019 Feb 15;21(2):5.

14. Shukla T et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 May/Jun;51(5):394-401.

15. McCurdy JD et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan;13(1):131-7; quiz e7.

16. Cottone M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar;96(3):773-5.

17. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2014 Mar;146(3):835-48 e6.

18. Limsrivilai J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Mar;15(3):385-92 e2.

19. Targownik LE et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Oct;109(10):1613-20.

20. Takeuchi K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Feb;4(2):196-202.

21. Travis SP et al. Gut. 1996 Jun;38(6):905-10.

22. Syal G et al. Mo1891 - Gastroenterology. 2018;154:S841.

23. Ungar B et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Jun;43(12):1293-9.

24. Laharie D et al. Lancet 2012 Dec 1;380(9857):1909-15.

Dr. Chiplunker is an advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellow; Dr. Ha is associate professor of medicine at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Introduction

Inpatient management of acute ulcerative colitis (UC) flares can be challenging because of the multiple patient and disease-related factors influencing therapeutic decision making. The clinical course during the first 24-72 hours of the hospitalization will likely guide the decision between rescue medical and surgical therapy. Using available evidence from clinical practice guidelines, we present a day-by-day guide to managing most hospitalized UC patients.

Day 0 – The emergency department (ED)

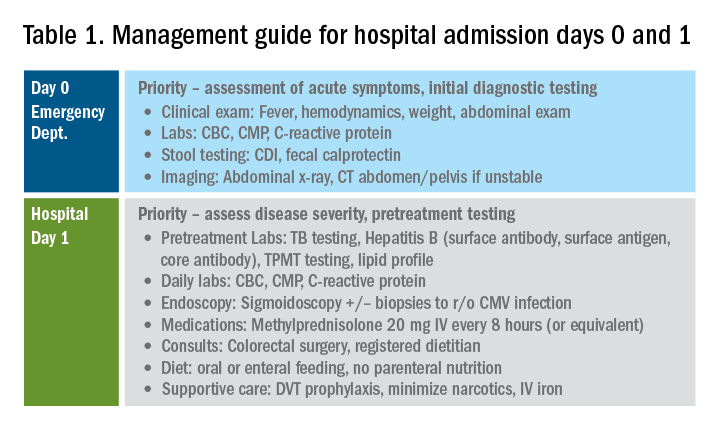

When an UC patient presents to the ED for evaluation, the initial assessments should focus on the acuity and severity of the flare. Key clinical features of disease severity include the presence of fever, tachycardia, hypotension, or weight loss in addition to worsened gastrointestinal symptoms of stool frequency relative to baseline, rectal bleeding, and abdominal pain. Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is often defined using the modified Truelove and Witts criteria.1 A patient meets criteria for ASUC if they have at least six bloody stools per day and at least one sign of systemic toxicity, such as heart rate greater than 90 bpm, temperature at or above 37.8° C, hemoglobin level below 10.5 g/dL, or elevated inflammatory markers.

Initial laboratory assessments should include complete blood counts to identify anemia, potential superimposed infection, or toxicity and a comprehensive metabolic profile to evaluate for dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, hepatic injury or hypoalbuminemia (an important predictor of surgery), as well as assessment of response to treatment and readmission.2,3 An evaluation at admission of C-reactive protein (CRP) is crucial because changes from the initial value will determine steroid response and predict need for surgical intervention or rescue therapy. A baseline fecal calprotectin can serve as a noninvasive marker that can be followed after discharge to monitor response to therapy.

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) must be ruled out in all patients presenting with ASUC regardless of history of antibiotic use or prior negative testing. Concomitant UC and CDI are associated with a four- to sixfold increased risk of in-hospital mortality and a two- to sixfold increased risk of bowel surgery.4-6 Immunoassay testing is inexpensive and fast with a high specificity but has low sensitivity; nucleic acid amplification testing with polymerase chain reaction has a high sensitivity and specificity.7 Knowing which testing algorithm the hospital lab uses helps guide interpretation of results.

For patients meeting criteria for ASUC, obtaining at least an abdominal x-ray is important to assess for colonic dilation to further stratify the patient by risk. Colonic dilation, defined as a transverse colon diameter greater than 5.5 cm, places the patient in the category of fulminant colitis and colorectal surgical consultation should be obtained.8 A CT scan is often ordered first because it can provide a rapid assessment of intra-abdominal processes but is not routinely needed unless hemodynamic instability, an acute abdomen, or markedly abnormal laboratory testing (specifically white blood cell count with bandemia) is present as these can be indicators of toxic megacolon or perforation.8-10

Day 1 – Assess disease severity and assemble the team

Obtaining a thorough clinical history is essential to classify disease severity and identify potential triggers for the acute exacerbation. Potential triggers may include infections, new medications, recent antibiotic use, recent travel, sick contacts, or cessation of treatments. Standard questions include asking about the timing of onset of symptoms, bowel movements during a 24-hour period, and particularly the presence of nocturnal bowel movements. If patients report bloody stools, inquire how often they see blood relative to the total number of bowel movements. The presence and nature of abdominal pain should be elicited, particularly changes in abdominal pain and comparison with previous disease flares. These clinical parameters are used to assess response to treatment; therefore, ask patients to keep a log of their stool frequency, consistency, rectal urgency, and bleeding each day to report to the team during daily rounds.

For patients with ASUC, a full colonoscopy is rarely indicated in the inpatient setting because it is unlikely to change management and poses a risk of perforation.11 However, a sigmoidoscopy within the first 24 hours of admission will provide useful information about the endoscopic disease activity, particularly if features such as deep or well-like ulcers, large mucosal abrasions, or extensive loss of the mucosal layer are present because these are predictors of colectomy.8 Tissue biopsies can exclude cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, an important consideration for patients on immunosuppression including corticosteroids.12-16

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis is extremely important for hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. At baseline, IBD patients have a threefold higher risk of VTE than do non-IBD patients, which increases to approximately sixfold during flares.17 Pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis is recommended for all hospitalized IBD patients, even those with rectal bleeding. This may seem counterintuitive in the setting of “GI bleeding,” so it is important to counsel both patients and team members regarding VTE risks and the role of the prophylactic regimen to ensure adherence. Mechanical VTE prophylaxis can be used in patients with severe bleeding and hemodynamic instability until pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis can be safely initiated.17

Narcotics should be used sparingly for hospitalized IBD patients. Narcotic use is associated with greater likelihood of subsequent IBD hospitalizations, ED visits, and higher costs of health care for patients with IBD.18 Heavy use of opiates, defined as continuous use for more than 30 days at a dose exceeding 50 mg morphine per day or equivalent, was strongly associated with an increased overall mortality in IBD patients.19 Opiates also slow bowel motility and precipitate toxic megacolon, along with any other agent that slows bowel motility, such as anticholinergic medications.8 These agents may also mask bowel frequency symptoms that would otherwise indicate a failure of medical therapy. Similarly, use of NSAIDS should also be avoided because these have been associated with disease relapse and escalating intestinal inflammation.20

Once disease severity has been determined, intravenous corticosteroid therapy may be initiated, ideally once CDI and CMV have been excluded. The recommended dosing of intravenous corticosteroids is methylprednisolone 20 mg IV every 8 hours or equivalent. There is no evidence to support additional benefit for doses exceeding these amounts.8 Prior to starting parenteral corticosteroids, it is important to keep in mind the possible need for rescue therapy during the admission. Recommended testing includes hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody, hepatitis B core antibody and tuberculosis testing if there is no documented negative testing within the past 6-12 months. These labs should be drawn prior to steroid treatment to avoid delays in care and indeterminate results. Finally, a lipid profile is recommended for patients who may be cyclosporine candidates pending response to intravenous corticosteroids. Unless the patient has been admitted with a bowel obstruction, which should raise the suspicion that the diagnosis is actually Crohn’s disease, enteral feeding is preferred for UC patients even if they may have significant food aversion. The early involvement of a registered dietitian is valuable to guide dietary choices and recommend appropriate enteral nutrition supplements. During acute flares, patients may find a low-residue diet to be less stimulating to their gut while their acute flare is being treated. Electrolyte abnormalities should be repleted and consistently monitored during the hospitalization. Providing parenteral intravenous iron for anemic patients will expedite correction of the anemia alongside treatment of the underlying UC.

Most UC patients admitted to the hospital will require a multidisciplinary approach with gastroenterologists, surgeons, radiologists, dietitians, and case coordinators/social workers, among others. It is essential to assemble the team, especially the surgeons, earlier during the hospitalization rather than later. It is especially important to discuss the role of the surgeon in the management of UC and explain why the surgeon is being consulted in the context of the patient’s acute presentation. Being transparent about the parameters the GI team are monitoring to determine if and when surgery is the most appropriate and safe approach will improve patients’ acceptance of the surgical team’s role in their care. Specific indications for surgery in ASUC include toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, severe refractory hemorrhage, and failure to respond to medical therapy (Table 1).8

Day 3 – Assessing response to corticosteroids

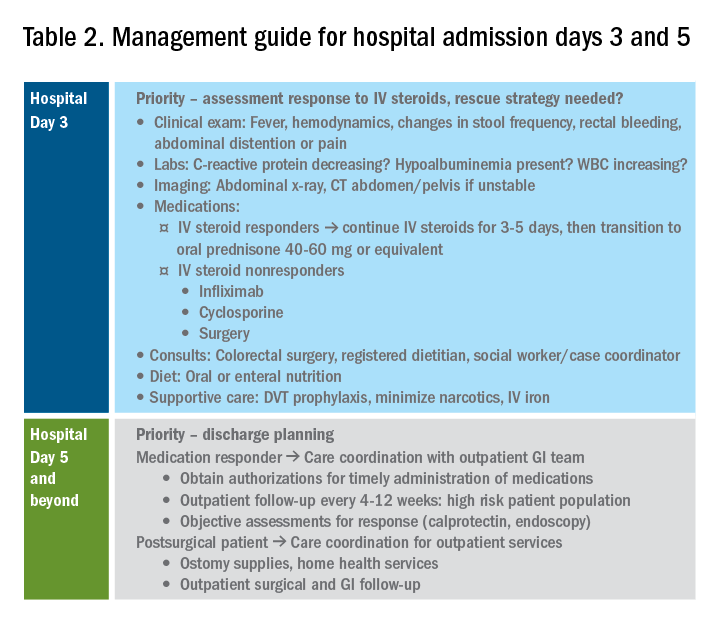

In addition to daily symptom assessments, a careful abdominal exam should be performed every day with the understanding that steroids (and also narcotics) may mask perforation or pain. Any abrupt decrease or cessation of bowel movements, increasing abdominal distention, or a sudden increase in abdominal pain or tenderness may require abdominal imaging to ensure no interim perforation or severe colonic dilation has occurred while receiving steroid therapy. In these circumstances, the addition of broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be considered, particularly if hemodynamic instability (such as tachycardia) is present.

Patients should be assessed for response to intravenous steroid therapy after 3 days of treatment. A meaningful response to corticosteroids is present if the patient has had more than 50% improvement in symptoms, particularly rectal bleeding and stool frequency. A more than 75% improvement in CRP should also be noted from admission to day 3 with an overall trend of improvement.2,21 Additionally, patients should be afebrile, require minimal to no narcotic usage, tolerating oral intake, and be ambulatory. If the patient has met all these parameters, it is reasonable to transition to oral corticosteroids, such as prednisone 40-60 mg daily after a course of 3-5 days of intravenous corticosteroids. Ideally, patients should be observed for 24-48 hours in the hospital after transitioning to oral corticosteroids to make sure that symptoms do not worsen with the switch.

Patients with more than eight bowel movements per day, CRP greater than 4.5 g/dL, deep ulcers on endoscopy, or albumin less than 3.0 g/dL have a higher likelihood of failing intravenous corticosteroid therapy, and these patients should be prepared for rescue therapy.2,21 A patient has failed intravenous corticosteroids by day 3 if they have sustained fever in the absence of an infection, continued CRP elevation or lack of CRP decrease, or ongoing high stool frequency, bleeding, and pain with less than 50% improvement from baseline on admission.8 In the setting of nonresponse to intravenous corticosteroids, it is prudent to involve colorectal surgery to discuss colectomy as an option of equal merit to medical salvage therapies such as infliximab or cyclosporine.

Infliximab is the most readily available rescue therapy for steroid-refractory patients and has been shown to increase colectomy-free survival in patients with ASUC.8 However, patients with the same predictors for intravenous steroid failures (low albumin, high CRP, and/or deep ulcers on endoscopy) are also at the highest risk for infliximab nonresponse. These factors are important to discuss with the patients and colorectal surgery teams when providing the options of treatment strategy, particularly with medication dosing. ASUC with more severe disease biochemically (low albumin, elevated CRP, possibly bandemia) benefit from a higher dose of infliximab at 10 mg/kg, given the likelihood of increased drug clearance in this situation.22,23

From a practical standpoint, it is important to confirm the patient’s insurance status prior to medication administration to make sure therapy can be continued after hospital discharge. Early involvement of the social workers and case coordinators is key to ensuring timely administration of the next dose of treatment. Patients who receive infliximab rescue therapy should be monitored for an additional 1-2 days after administration to ensure they are responding to this therapy with continued monitoring of CRP and symptoms during this period. If there is no response at this point, an additional dose of infliximab may be considered but surgery should not be delayed if there is no meaningful response after the first dose.

Another option for intravenous corticosteroid nonresponders is intravenous cyclosporine because treatment failure rates for cyclosporine and infliximab were similar in head-to-head studies.24 However, patient selection is key to successful utilization of this agent. Unlike infliximab, cyclosporine is primarily an induction agent for steroid nonresponders rather than a maintenance strategy. Therefore, in patients in whom cyclosporine is being considered, thiopurines or vedolizumab are potential options for maintenance therapy. If the patient has poor renal function, low cholesterol, advanced age, significant comorbidities, or a history of nonadherence to therapy, cyclosporine should not be given. Additionally, clinical experience with intravenous cyclosporine administration and monitoring both during inpatient and outpatient care settings should be factored into the decision making for infliximab versus cyclosporine.8

Day 5 and beyond – Discharge planning

Patients who have responded to the initial intravenous steroid course by hospital day 5 should have successfully transitioned to oral steroids with plans to start an appropriate steroid-sparing therapy shortly after discharge. Treatment planning should commence prior to discharge and should be communicated with the outpatient GI team to ensure a smooth transition to the ambulatory care setting, primarily to begin insurance authorizations as soon as possible. If the patient has had a meaningful response to infliximab rescue therapy (improvement by more than 50% in bowel frequency, amount of blood, abdominal pain), discharge planning needs to prioritize obtaining authorization for the second dose within 2 weeks of the initial infusion. These patients are high risk for readmission, and close outpatient follow-up by the ambulatory GI care team is necessary to help direct the tapering of steroids and monitor response to treatment.

If the patient has not responded to intravenous steroid therapy, infliximab, or cyclosporine by day 5-7, then surgery should be strongly considered. Delaying surgery may worsen outcomes as patients become more malnourished, anemic, and continue to receive intravenous steroids. Additional preoperative optimization may be required depending on the patient’s course up to this point (Table 2).

Summary

The cornerstones of inpatient UC management center on a thorough initial evaluation including imaging and endoscopy as appropriate, establishment of baseline parameters, and daily assessment of response to therapy through a combination of patient-reported outcomes and biomarkers of inflammation. With this strategy in mind, practitioners and care teams can manage these complex patients using a consistent strategy focusing on multidisciplinary, evidence-based care.

References

1. Truelove SC et al. Br Med J. 1955 Oct 23;2(4947):1041-8.

2. Ho GT et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004 May 15;19(10):1079-87.

3. Tinsley A et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(9):1103-9.

4. Issa M et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Mar;5(3):345-51.

5. Ananthakrishnan AN et al. Gut. 2008 Feb;57(2):205-10.

6. Negron ME et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 May;111(5):691-704.

7. Taylor KN et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Feb;144(2):428-37.

8. Rubin DT et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Mar;114(3):384-413.

9. Jalan KN et al. Gastroenterology. 1969 Jul;57(1):68-82.

10. Gan SI et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Nov;98(11):2363-71.

11. Makkar R et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013 Sep;9(9):573-83.

12. Hindryckx P et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Nov;13(11):654-64.

13. Yerushalmy-Feler A et al. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2019 Feb 15;21(2):5.

14. Shukla T et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 May/Jun;51(5):394-401.

15. McCurdy JD et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan;13(1):131-7; quiz e7.

16. Cottone M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar;96(3):773-5.

17. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2014 Mar;146(3):835-48 e6.

18. Limsrivilai J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Mar;15(3):385-92 e2.

19. Targownik LE et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Oct;109(10):1613-20.

20. Takeuchi K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Feb;4(2):196-202.

21. Travis SP et al. Gut. 1996 Jun;38(6):905-10.

22. Syal G et al. Mo1891 - Gastroenterology. 2018;154:S841.

23. Ungar B et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Jun;43(12):1293-9.

24. Laharie D et al. Lancet 2012 Dec 1;380(9857):1909-15.

Dr. Chiplunker is an advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellow; Dr. Ha is associate professor of medicine at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Introduction

Inpatient management of acute ulcerative colitis (UC) flares can be challenging because of the multiple patient and disease-related factors influencing therapeutic decision making. The clinical course during the first 24-72 hours of the hospitalization will likely guide the decision between rescue medical and surgical therapy. Using available evidence from clinical practice guidelines, we present a day-by-day guide to managing most hospitalized UC patients.

Day 0 – The emergency department (ED)

When an UC patient presents to the ED for evaluation, the initial assessments should focus on the acuity and severity of the flare. Key clinical features of disease severity include the presence of fever, tachycardia, hypotension, or weight loss in addition to worsened gastrointestinal symptoms of stool frequency relative to baseline, rectal bleeding, and abdominal pain. Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is often defined using the modified Truelove and Witts criteria.1 A patient meets criteria for ASUC if they have at least six bloody stools per day and at least one sign of systemic toxicity, such as heart rate greater than 90 bpm, temperature at or above 37.8° C, hemoglobin level below 10.5 g/dL, or elevated inflammatory markers.

Initial laboratory assessments should include complete blood counts to identify anemia, potential superimposed infection, or toxicity and a comprehensive metabolic profile to evaluate for dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, hepatic injury or hypoalbuminemia (an important predictor of surgery), as well as assessment of response to treatment and readmission.2,3 An evaluation at admission of C-reactive protein (CRP) is crucial because changes from the initial value will determine steroid response and predict need for surgical intervention or rescue therapy. A baseline fecal calprotectin can serve as a noninvasive marker that can be followed after discharge to monitor response to therapy.

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) must be ruled out in all patients presenting with ASUC regardless of history of antibiotic use or prior negative testing. Concomitant UC and CDI are associated with a four- to sixfold increased risk of in-hospital mortality and a two- to sixfold increased risk of bowel surgery.4-6 Immunoassay testing is inexpensive and fast with a high specificity but has low sensitivity; nucleic acid amplification testing with polymerase chain reaction has a high sensitivity and specificity.7 Knowing which testing algorithm the hospital lab uses helps guide interpretation of results.

For patients meeting criteria for ASUC, obtaining at least an abdominal x-ray is important to assess for colonic dilation to further stratify the patient by risk. Colonic dilation, defined as a transverse colon diameter greater than 5.5 cm, places the patient in the category of fulminant colitis and colorectal surgical consultation should be obtained.8 A CT scan is often ordered first because it can provide a rapid assessment of intra-abdominal processes but is not routinely needed unless hemodynamic instability, an acute abdomen, or markedly abnormal laboratory testing (specifically white blood cell count with bandemia) is present as these can be indicators of toxic megacolon or perforation.8-10

Day 1 – Assess disease severity and assemble the team

Obtaining a thorough clinical history is essential to classify disease severity and identify potential triggers for the acute exacerbation. Potential triggers may include infections, new medications, recent antibiotic use, recent travel, sick contacts, or cessation of treatments. Standard questions include asking about the timing of onset of symptoms, bowel movements during a 24-hour period, and particularly the presence of nocturnal bowel movements. If patients report bloody stools, inquire how often they see blood relative to the total number of bowel movements. The presence and nature of abdominal pain should be elicited, particularly changes in abdominal pain and comparison with previous disease flares. These clinical parameters are used to assess response to treatment; therefore, ask patients to keep a log of their stool frequency, consistency, rectal urgency, and bleeding each day to report to the team during daily rounds.

For patients with ASUC, a full colonoscopy is rarely indicated in the inpatient setting because it is unlikely to change management and poses a risk of perforation.11 However, a sigmoidoscopy within the first 24 hours of admission will provide useful information about the endoscopic disease activity, particularly if features such as deep or well-like ulcers, large mucosal abrasions, or extensive loss of the mucosal layer are present because these are predictors of colectomy.8 Tissue biopsies can exclude cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, an important consideration for patients on immunosuppression including corticosteroids.12-16

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis is extremely important for hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. At baseline, IBD patients have a threefold higher risk of VTE than do non-IBD patients, which increases to approximately sixfold during flares.17 Pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis is recommended for all hospitalized IBD patients, even those with rectal bleeding. This may seem counterintuitive in the setting of “GI bleeding,” so it is important to counsel both patients and team members regarding VTE risks and the role of the prophylactic regimen to ensure adherence. Mechanical VTE prophylaxis can be used in patients with severe bleeding and hemodynamic instability until pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis can be safely initiated.17

Narcotics should be used sparingly for hospitalized IBD patients. Narcotic use is associated with greater likelihood of subsequent IBD hospitalizations, ED visits, and higher costs of health care for patients with IBD.18 Heavy use of opiates, defined as continuous use for more than 30 days at a dose exceeding 50 mg morphine per day or equivalent, was strongly associated with an increased overall mortality in IBD patients.19 Opiates also slow bowel motility and precipitate toxic megacolon, along with any other agent that slows bowel motility, such as anticholinergic medications.8 These agents may also mask bowel frequency symptoms that would otherwise indicate a failure of medical therapy. Similarly, use of NSAIDS should also be avoided because these have been associated with disease relapse and escalating intestinal inflammation.20

Once disease severity has been determined, intravenous corticosteroid therapy may be initiated, ideally once CDI and CMV have been excluded. The recommended dosing of intravenous corticosteroids is methylprednisolone 20 mg IV every 8 hours or equivalent. There is no evidence to support additional benefit for doses exceeding these amounts.8 Prior to starting parenteral corticosteroids, it is important to keep in mind the possible need for rescue therapy during the admission. Recommended testing includes hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody, hepatitis B core antibody and tuberculosis testing if there is no documented negative testing within the past 6-12 months. These labs should be drawn prior to steroid treatment to avoid delays in care and indeterminate results. Finally, a lipid profile is recommended for patients who may be cyclosporine candidates pending response to intravenous corticosteroids. Unless the patient has been admitted with a bowel obstruction, which should raise the suspicion that the diagnosis is actually Crohn’s disease, enteral feeding is preferred for UC patients even if they may have significant food aversion. The early involvement of a registered dietitian is valuable to guide dietary choices and recommend appropriate enteral nutrition supplements. During acute flares, patients may find a low-residue diet to be less stimulating to their gut while their acute flare is being treated. Electrolyte abnormalities should be repleted and consistently monitored during the hospitalization. Providing parenteral intravenous iron for anemic patients will expedite correction of the anemia alongside treatment of the underlying UC.

Most UC patients admitted to the hospital will require a multidisciplinary approach with gastroenterologists, surgeons, radiologists, dietitians, and case coordinators/social workers, among others. It is essential to assemble the team, especially the surgeons, earlier during the hospitalization rather than later. It is especially important to discuss the role of the surgeon in the management of UC and explain why the surgeon is being consulted in the context of the patient’s acute presentation. Being transparent about the parameters the GI team are monitoring to determine if and when surgery is the most appropriate and safe approach will improve patients’ acceptance of the surgical team’s role in their care. Specific indications for surgery in ASUC include toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, severe refractory hemorrhage, and failure to respond to medical therapy (Table 1).8

Day 3 – Assessing response to corticosteroids

In addition to daily symptom assessments, a careful abdominal exam should be performed every day with the understanding that steroids (and also narcotics) may mask perforation or pain. Any abrupt decrease or cessation of bowel movements, increasing abdominal distention, or a sudden increase in abdominal pain or tenderness may require abdominal imaging to ensure no interim perforation or severe colonic dilation has occurred while receiving steroid therapy. In these circumstances, the addition of broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be considered, particularly if hemodynamic instability (such as tachycardia) is present.

Patients should be assessed for response to intravenous steroid therapy after 3 days of treatment. A meaningful response to corticosteroids is present if the patient has had more than 50% improvement in symptoms, particularly rectal bleeding and stool frequency. A more than 75% improvement in CRP should also be noted from admission to day 3 with an overall trend of improvement.2,21 Additionally, patients should be afebrile, require minimal to no narcotic usage, tolerating oral intake, and be ambulatory. If the patient has met all these parameters, it is reasonable to transition to oral corticosteroids, such as prednisone 40-60 mg daily after a course of 3-5 days of intravenous corticosteroids. Ideally, patients should be observed for 24-48 hours in the hospital after transitioning to oral corticosteroids to make sure that symptoms do not worsen with the switch.

Patients with more than eight bowel movements per day, CRP greater than 4.5 g/dL, deep ulcers on endoscopy, or albumin less than 3.0 g/dL have a higher likelihood of failing intravenous corticosteroid therapy, and these patients should be prepared for rescue therapy.2,21 A patient has failed intravenous corticosteroids by day 3 if they have sustained fever in the absence of an infection, continued CRP elevation or lack of CRP decrease, or ongoing high stool frequency, bleeding, and pain with less than 50% improvement from baseline on admission.8 In the setting of nonresponse to intravenous corticosteroids, it is prudent to involve colorectal surgery to discuss colectomy as an option of equal merit to medical salvage therapies such as infliximab or cyclosporine.

Infliximab is the most readily available rescue therapy for steroid-refractory patients and has been shown to increase colectomy-free survival in patients with ASUC.8 However, patients with the same predictors for intravenous steroid failures (low albumin, high CRP, and/or deep ulcers on endoscopy) are also at the highest risk for infliximab nonresponse. These factors are important to discuss with the patients and colorectal surgery teams when providing the options of treatment strategy, particularly with medication dosing. ASUC with more severe disease biochemically (low albumin, elevated CRP, possibly bandemia) benefit from a higher dose of infliximab at 10 mg/kg, given the likelihood of increased drug clearance in this situation.22,23

From a practical standpoint, it is important to confirm the patient’s insurance status prior to medication administration to make sure therapy can be continued after hospital discharge. Early involvement of the social workers and case coordinators is key to ensuring timely administration of the next dose of treatment. Patients who receive infliximab rescue therapy should be monitored for an additional 1-2 days after administration to ensure they are responding to this therapy with continued monitoring of CRP and symptoms during this period. If there is no response at this point, an additional dose of infliximab may be considered but surgery should not be delayed if there is no meaningful response after the first dose.

Another option for intravenous corticosteroid nonresponders is intravenous cyclosporine because treatment failure rates for cyclosporine and infliximab were similar in head-to-head studies.24 However, patient selection is key to successful utilization of this agent. Unlike infliximab, cyclosporine is primarily an induction agent for steroid nonresponders rather than a maintenance strategy. Therefore, in patients in whom cyclosporine is being considered, thiopurines or vedolizumab are potential options for maintenance therapy. If the patient has poor renal function, low cholesterol, advanced age, significant comorbidities, or a history of nonadherence to therapy, cyclosporine should not be given. Additionally, clinical experience with intravenous cyclosporine administration and monitoring both during inpatient and outpatient care settings should be factored into the decision making for infliximab versus cyclosporine.8

Day 5 and beyond – Discharge planning

Patients who have responded to the initial intravenous steroid course by hospital day 5 should have successfully transitioned to oral steroids with plans to start an appropriate steroid-sparing therapy shortly after discharge. Treatment planning should commence prior to discharge and should be communicated with the outpatient GI team to ensure a smooth transition to the ambulatory care setting, primarily to begin insurance authorizations as soon as possible. If the patient has had a meaningful response to infliximab rescue therapy (improvement by more than 50% in bowel frequency, amount of blood, abdominal pain), discharge planning needs to prioritize obtaining authorization for the second dose within 2 weeks of the initial infusion. These patients are high risk for readmission, and close outpatient follow-up by the ambulatory GI care team is necessary to help direct the tapering of steroids and monitor response to treatment.

If the patient has not responded to intravenous steroid therapy, infliximab, or cyclosporine by day 5-7, then surgery should be strongly considered. Delaying surgery may worsen outcomes as patients become more malnourished, anemic, and continue to receive intravenous steroids. Additional preoperative optimization may be required depending on the patient’s course up to this point (Table 2).

Summary

The cornerstones of inpatient UC management center on a thorough initial evaluation including imaging and endoscopy as appropriate, establishment of baseline parameters, and daily assessment of response to therapy through a combination of patient-reported outcomes and biomarkers of inflammation. With this strategy in mind, practitioners and care teams can manage these complex patients using a consistent strategy focusing on multidisciplinary, evidence-based care.

References

1. Truelove SC et al. Br Med J. 1955 Oct 23;2(4947):1041-8.

2. Ho GT et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004 May 15;19(10):1079-87.

3. Tinsley A et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(9):1103-9.

4. Issa M et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Mar;5(3):345-51.

5. Ananthakrishnan AN et al. Gut. 2008 Feb;57(2):205-10.

6. Negron ME et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 May;111(5):691-704.

7. Taylor KN et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Feb;144(2):428-37.

8. Rubin DT et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Mar;114(3):384-413.

9. Jalan KN et al. Gastroenterology. 1969 Jul;57(1):68-82.

10. Gan SI et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Nov;98(11):2363-71.

11. Makkar R et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013 Sep;9(9):573-83.

12. Hindryckx P et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Nov;13(11):654-64.

13. Yerushalmy-Feler A et al. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2019 Feb 15;21(2):5.

14. Shukla T et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 May/Jun;51(5):394-401.

15. McCurdy JD et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan;13(1):131-7; quiz e7.

16. Cottone M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar;96(3):773-5.

17. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2014 Mar;146(3):835-48 e6.

18. Limsrivilai J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Mar;15(3):385-92 e2.

19. Targownik LE et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Oct;109(10):1613-20.

20. Takeuchi K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Feb;4(2):196-202.

21. Travis SP et al. Gut. 1996 Jun;38(6):905-10.

22. Syal G et al. Mo1891 - Gastroenterology. 2018;154:S841.

23. Ungar B et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Jun;43(12):1293-9.

24. Laharie D et al. Lancet 2012 Dec 1;380(9857):1909-15.

Dr. Chiplunker is an advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellow; Dr. Ha is associate professor of medicine at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.