User login

Quality metrics in colonoscopy

Editor's Note:

As quality metrics are becoming increasingly significant throughout all of medicine, our field is no exception. Recent evidence has demonstrated the importance of quality measures in colonoscopy; understanding, reporting, and improving these metrics has become a hot topic of discussion.

In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, Nabiha Shamsi, Ashish Malhotra, and Aasma Shaukat (University of Minnesota/Minneapolis VAMC) provide an outstanding overview of the evidence as well as recommended goals for important quality metrics in colonoscopy. Ultimately, improving colonoscopy quality amongst all gastroenterologists will increase colonoscopy value and lead to further decreases in the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Introduction

Colonoscopy is a widely used modality to evaluate colorectal cancer because it allows for both identification of early malignancies and removal of precancerous lesions. The increased use of colonoscopy in the last 20 years has been associated with a decline in the incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer.1,2 However, colonoscopy has its limitations. It is an invasive test with inherent risks. Additionally, studies have reported rates of post-colonoscopy cancers, also referred to as interval cancers, of 2%-7%, and miss-rates for adenomas by tandem colonoscopy of 2%-26%.3-5

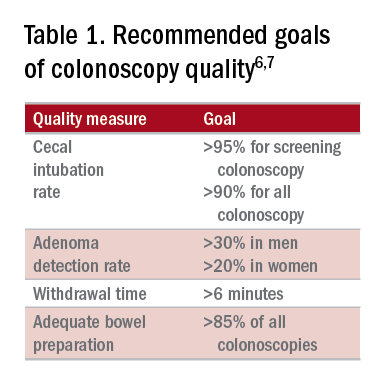

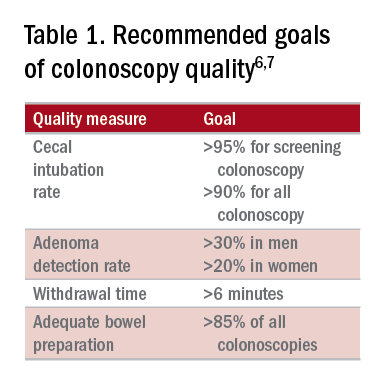

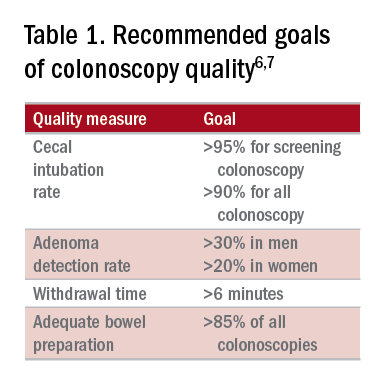

High-quality exams can maximize the value of colonoscopy, and it is important to consider the factors that contribute to high-quality colonoscopies. While there are many metrics proposed,6,7 here we discuss the most evidence-based ones, outlined in Table 1, along with their goal values.

Cecal intubation rate

A high-quality colonoscopy should include a complete examination of the colon. To achieve this, it is necessary to fully intubate the cecum, passing the colonoscope past the ileocecal valve to examine the medial wall of the cecum.8

There are several factors that may contribute to an incomplete colonoscopy, including bowel preparation, anatomy, body habitus, and endoscopist’s skill. To calculate cecal intubation rate as a quality measure, colonoscopies that are incomplete because of poor bowel preparation, severe colitis, or known obstructing lesion are usually excluded.

The U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer recommends a cecal intubation rate of at least 95% for screening colonoscopy and 90% for all colonoscopies.6 There is an expectation of photodocumentation of the ileocecal valve and appendiceal orifice to establish completion of the colonoscopy.6

Some methods used to assist with cecal intubation include changing patient position, applying abdominal pressure, stiffening the colonoscope, and alternating between adult or pediatric colonoscopes.

Adenoma detection rate

Adenoma detection rate (ADR), is defined as the proportion of patients over the age of 50 years undergoing first-time screening colonoscopies in which at least one adenomatous polyp is detected for a given endoscopist in a given time period.

Adenomas are tracked because clearing the colon of neoplasm is the goal of screening colonoscopies; adenomas are tracked instead of more advanced lesions because the higher frequency of adenomas allows for better tracking of variation between endoscopists. Tracking ADR also utilizes the assumption that, if small lesions are identified, larger ones will be as well.

ADR is the only current quality indicator reported to be significantly associated with the risk of interval cancers. In 2010, a study of 45,000 screening colonoscopies by 186 endoscopists validated the use of ADR, finding that patients who underwent colonoscopy by physicians with ADRs below 20% had hazard ratios for development of postcolonoscopy cancer greater than 10 times higher than patients of physicians with ADRs above 20%.9 However, this study had limited power to establish that cancer protection continues to improve when ADRs rise above 20%. Another study, which evaluated the association of ADR in 224,000 patients undergoing colonoscopies by 136 gastroenterologists, showed each 1% increase in ADR is associated with 3% decrease in the risk of interval CRC and 5% decrease in the risk of fatal interval cancers.10

Most recent guidelines propose an adequate ADR for asymptomatic individuals aged 50 years or older undergoing screening colonoscopy should be greater than 30% in men and greater than 20% in women.6 It remains unknown whether there is a threshold for maximum benefit of ADR, in which a very high ADR is not associated with further protective benefit. The answer to this question may depend on why a low ADR is associated with a higher rate of interval cancers and whether every missed polyp, independent of size, is a potential interval cancer or whether hasty, inadequate, or incomplete examinations of the colon are the underlying concern.

Withdrawal time

Optimizing identification of colonic lesions requires a careful and thorough exam of the colon on withdrawal. While this may seem obvious, there is often little focus on the approach to withdrawal. In four chapters on colonoscopy technique from textbooks, the number of pages describing insertion ranged from 20 to 38, while the number of pages focused on withdrawal ranged from 0.5 to 1.5.11-14

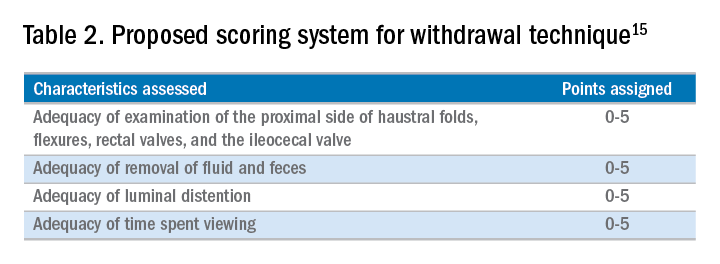

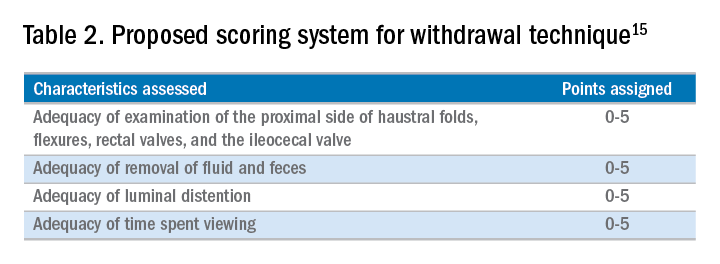

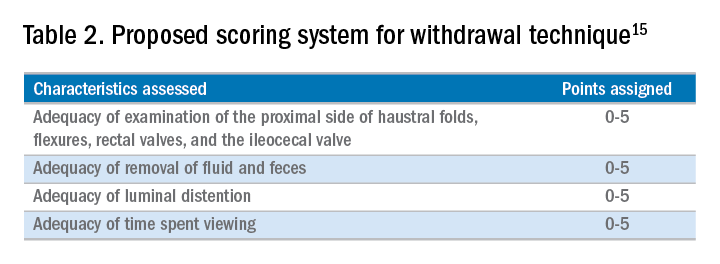

A study examining the difference in withdrawal technique between two endoscopists who were known to differ in adenoma miss rates by tandem colonoscopy proposed the scoring system listed in Table 2 that can assess quality of examination on withdrawal. There was a statistically significant difference in quality scores for the two endoscopists, as assessed by expert review of video recordings of their colonoscopies.15

The endoscopist with the lower adenoma miss rate was also found to have an average withdrawal time of 8 minutes and 55 seconds versus 6 minutes and 41 seconds for the endoscopist with the higher adenoma miss rate. A large, community-based study with over 76,000 colonoscopies found a statistically significant correlation between interval colorectal cancer and withdrawal times shorter than 6 minutes.16 However, there was no association between ADR and colorectal cancer, suggesting that, for practices with optimal ADRs (that is, rates greater than 25%), withdrawal time may be a more sensitive marker of quality of colonoscopy than ADR is.16Intuitively, adequate examination of the colon that includes examining the proximal side of folds, washing and suctioning stool, and even repositioning the patient would likely increase withdrawal time. In a 2008 study examining 2,000 screening colonoscopies of 12 endoscopists, those with withdrawal times greater than 6 minutes had significantly higher rates of detecting adenomas and advanced neoplasia, compared with those with faster withdrawal times.17 The average ADR in this group was 28.3%, compared with 11.8% for physicians who had a withdrawal time less than 6 minutes.17 An evaluation of nearly 11,000 colonoscopies done by 43 endoscopists also identified an increase polyp yield with increased withdrawal time.18 These data drive the recommendation for a minimum withdrawal time of 6 minutes, with 2 minutes spent examining each colonic segment.

Bowel preparation

Diagnosis of colonic lesions is dependent on adequate visualization of the colon. Poor bowel preparation can limit the yield of colonoscopy and lead to missed lesions. It also leads to canceled and rescheduled procedures that reduce efficiency, increase cost, and pose an undue burden on the patient.

The quality of bowel preparation should be assessed after washing and suctioning of colonic mucosa has been completed. Adequate preparation is that which allows identification of lesions greater than 5 mm in size.19

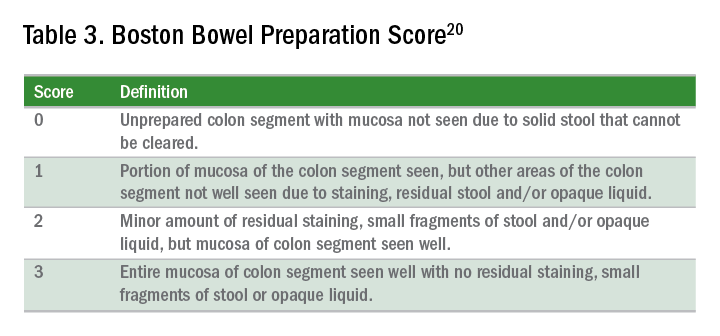

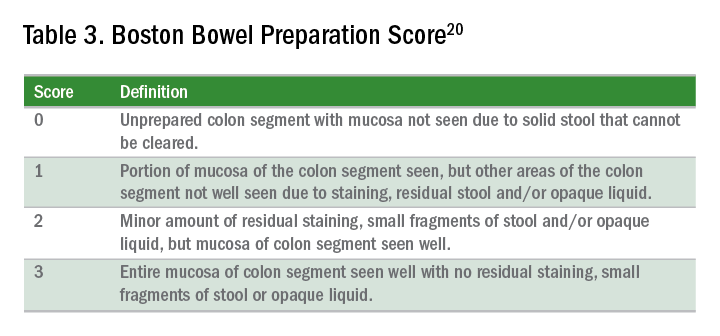

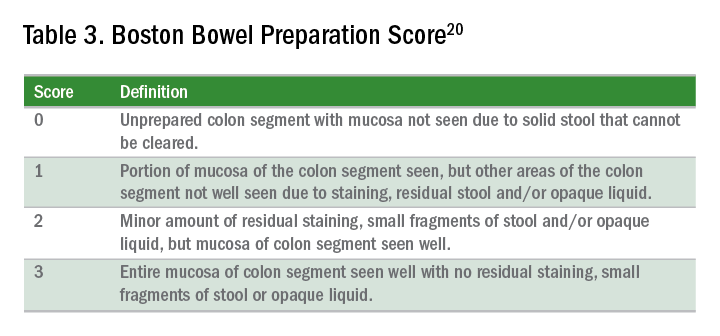

Quality of preparation is assessed subjectively by the endoscopists and often listed as excellent, good, fair, or poor. An alternative method of reporting bowel preparation quality is the Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) (Table 3).20 This scoring system allows for a more descriptive assessment of each colonic segment by assigning a score from 0 to 3 for the right, transverse, and left colon, leading to a total score between 0 and 9. The BBPS also helps standardize reporting of bowel preparation. The polyp detection rate associated with a BBPS of 5 or greater was 40%, compared with 24% associated with BBPS less than 5.19 A split-dose bowel preparation regimen with at least half of the preparation ingested on the day of the procedure is recommended to optimize quality of bowel preparation.6

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology task force on quality assurance in endoscopy recommends that bowel preparation should be adequate in 85% of all colonoscopy exams on a per-provider basis.7 One study of completed colonoscopy with inadequate preparation showed an adenoma miss rate of 48%.21 In the setting of inadequate bowel preparation, another study reported 42% of all adenomas detected were only found on repeat colonoscopy. When considering advanced adenomas, there was a 27% miss rate, a relatively high percentage.22

When poor bowel preparation precludes the exam, colonoscopy is appropriately aborted, and the patient asked to return. However, there are situations in which the exam can be completed but the bowel preparation is still inadequate to identify polyps larger than 5 mm. In this setting, the colonoscopy should be repeated with a more aggressive bowel preparation regimen within 1 year.19 Shorter intervals are recommended if advanced neoplasm is detected within an inadequate bowel preparation.19

The appropriate surveillance interval can be unclear when bowel preparation is considered adequate to identify polyps greater than or equal to 5 mm, yet still suboptimal. “Adequate” or “fair” bowel preparation often leads to shorter-than-recommended surveillance intervals because of the concern for small missed lesions. For example, patients with normal colonoscopy results and a fair prep were recommended to undergo a screening colonoscopy in 5 years at 57.4%, while only 23.1% received a 10-year recommendation.23 This increased frequency of colonoscopy leads to increased costs and procedural risks for the patient. Furthermore, a meta-analysis evaluating the effects of bowel preparation reported no significant difference in ADR between adequate and excellent prep.24 These findings suggest that patients with adequate bowel preparation may be followed at guideline-recommended surveillance intervals without significantly affecting colonoscopy quality as measured by ADR.

Endoscopist feedback and report cards

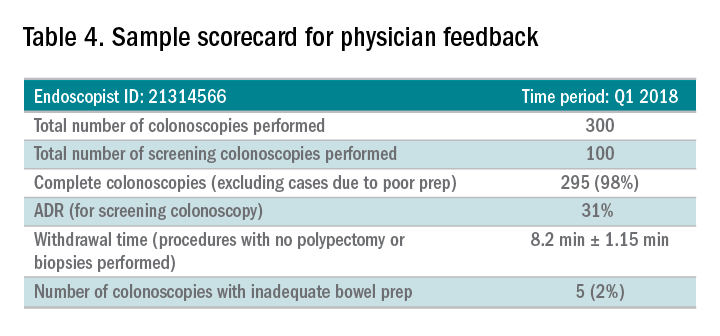

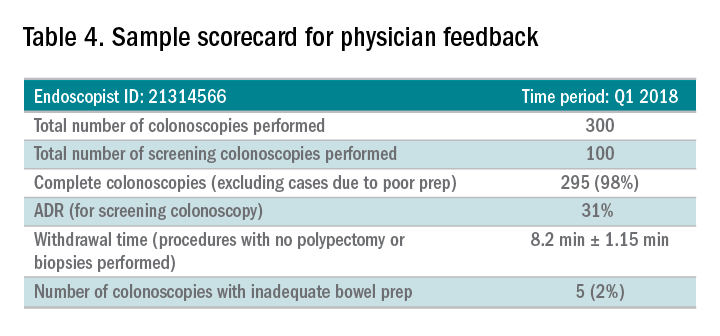

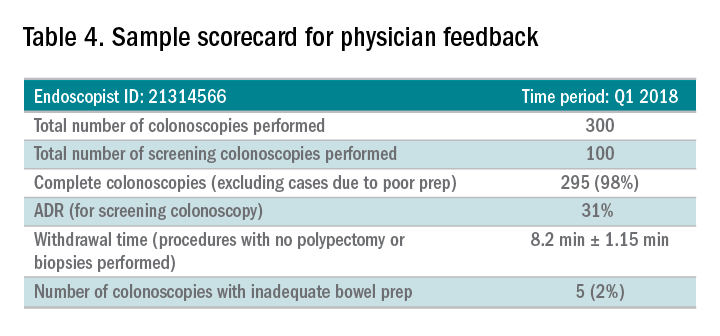

Awareness of quality metrics among individuals and endoscopy practices is crucial to ensuring adequate performance. Several studies have shown improvement with feedback and monitoring of endoscopists.25,26 Some strategies to improve colonoscopy technique and efficiency include having recorded or observed procedures, computer software that measures image resolution/velocity, and scorecards with quality measures. A representation of the scorecards used in our practice is shown in Table 4. Feedback measures both make endoscopists aware of how their performance compares with recommended goals for colonoscopy and help track their improvement. We recommend such feedback should be provided quarterly for most providers and more frequently for providers not meeting benchmarks.

Conclusion

Given we rely on colonoscopy to identify and clear the colon of potential malignancy, it is imperative that we provide high-value exams for our patients. The basis for a quality colonoscopy is complete intubation and careful inspection of the mucosa on withdrawal. Several quality measures are used as surrogates of a good exam such that endoscopists can assess themselves in relation to their peers. These metrics can help us in our goal of remaining mindful during each procedure we are completing and providing the best exam possible.

Dr. Shamsi is a third-year GI fellow. Dr. Malhotra is an assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Dr. Shaukat is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and the GI Section Chief at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center.

References

1. Siegel R et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 Jan-Feb;62(1):10-29.

2. Edwards BK et al. Cancer. 2010 Feb 1;116(3):544-73.

3. Hosokawa O et al. Endoscopy. 2003 Jun;35(6):506-10.

4. Morris EJ et al. Gut. 2015(Aug);64(2):1248-56.

5. Bressler B et al. Gastroenterology. 2004 Aug;127(2):452-6.

6. Rex DK et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 July;12(7):1016-30.

7. Rex DK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jan;81(1):31-53.

8. Anderson J et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb 26;6:e77.

9. Kaminski M et al. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 13;362(19):1795-803.

10. Corley DA et al. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 3;370(4):1298-306.

11. Hunt RH. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 109-46.

12. Waye JD. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 147-78.

13. Williams CB et al. In: Colonoscopy principles & techniques. Edited by Raskin J, Juergen NH. New York: Igaku-Shoin Medical Publishers; 1995. p. 121-42.

14. Baillie J. Colonoscopy. In: Gastrointestinal endoscopy basic principles and practice. Oxford (UK): Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992. p. 63-92.

15. Rex DK. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Jan;51(1):33-6.

16. Shaukat A et al. Gastroenterol. 2015;149(4):952-7.

17. Barclay R et al. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 14;355(24):2533-41.

18. Simmons DT et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(5):AB94.

19. Johnson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(4):543-62.

20. Calderwood A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):686-92.

21. Chokshi R et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Jun;75(6):1197-203.

22. Lebwohl B et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Jun;73(6):1207-14.

23. Menees SB et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Sep;78(3): 510-6.

24. Clark B et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov;109(11):1714-23.

25. Nielson A et al. BMJ Open Gastro. 2017 Jun. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000142.

26. Gurudu S et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Mar;33(3):645-9.

Editor's Note:

As quality metrics are becoming increasingly significant throughout all of medicine, our field is no exception. Recent evidence has demonstrated the importance of quality measures in colonoscopy; understanding, reporting, and improving these metrics has become a hot topic of discussion.

In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, Nabiha Shamsi, Ashish Malhotra, and Aasma Shaukat (University of Minnesota/Minneapolis VAMC) provide an outstanding overview of the evidence as well as recommended goals for important quality metrics in colonoscopy. Ultimately, improving colonoscopy quality amongst all gastroenterologists will increase colonoscopy value and lead to further decreases in the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Introduction

Colonoscopy is a widely used modality to evaluate colorectal cancer because it allows for both identification of early malignancies and removal of precancerous lesions. The increased use of colonoscopy in the last 20 years has been associated with a decline in the incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer.1,2 However, colonoscopy has its limitations. It is an invasive test with inherent risks. Additionally, studies have reported rates of post-colonoscopy cancers, also referred to as interval cancers, of 2%-7%, and miss-rates for adenomas by tandem colonoscopy of 2%-26%.3-5

High-quality exams can maximize the value of colonoscopy, and it is important to consider the factors that contribute to high-quality colonoscopies. While there are many metrics proposed,6,7 here we discuss the most evidence-based ones, outlined in Table 1, along with their goal values.

Cecal intubation rate

A high-quality colonoscopy should include a complete examination of the colon. To achieve this, it is necessary to fully intubate the cecum, passing the colonoscope past the ileocecal valve to examine the medial wall of the cecum.8

There are several factors that may contribute to an incomplete colonoscopy, including bowel preparation, anatomy, body habitus, and endoscopist’s skill. To calculate cecal intubation rate as a quality measure, colonoscopies that are incomplete because of poor bowel preparation, severe colitis, or known obstructing lesion are usually excluded.

The U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer recommends a cecal intubation rate of at least 95% for screening colonoscopy and 90% for all colonoscopies.6 There is an expectation of photodocumentation of the ileocecal valve and appendiceal orifice to establish completion of the colonoscopy.6

Some methods used to assist with cecal intubation include changing patient position, applying abdominal pressure, stiffening the colonoscope, and alternating between adult or pediatric colonoscopes.

Adenoma detection rate

Adenoma detection rate (ADR), is defined as the proportion of patients over the age of 50 years undergoing first-time screening colonoscopies in which at least one adenomatous polyp is detected for a given endoscopist in a given time period.

Adenomas are tracked because clearing the colon of neoplasm is the goal of screening colonoscopies; adenomas are tracked instead of more advanced lesions because the higher frequency of adenomas allows for better tracking of variation between endoscopists. Tracking ADR also utilizes the assumption that, if small lesions are identified, larger ones will be as well.

ADR is the only current quality indicator reported to be significantly associated with the risk of interval cancers. In 2010, a study of 45,000 screening colonoscopies by 186 endoscopists validated the use of ADR, finding that patients who underwent colonoscopy by physicians with ADRs below 20% had hazard ratios for development of postcolonoscopy cancer greater than 10 times higher than patients of physicians with ADRs above 20%.9 However, this study had limited power to establish that cancer protection continues to improve when ADRs rise above 20%. Another study, which evaluated the association of ADR in 224,000 patients undergoing colonoscopies by 136 gastroenterologists, showed each 1% increase in ADR is associated with 3% decrease in the risk of interval CRC and 5% decrease in the risk of fatal interval cancers.10

Most recent guidelines propose an adequate ADR for asymptomatic individuals aged 50 years or older undergoing screening colonoscopy should be greater than 30% in men and greater than 20% in women.6 It remains unknown whether there is a threshold for maximum benefit of ADR, in which a very high ADR is not associated with further protective benefit. The answer to this question may depend on why a low ADR is associated with a higher rate of interval cancers and whether every missed polyp, independent of size, is a potential interval cancer or whether hasty, inadequate, or incomplete examinations of the colon are the underlying concern.

Withdrawal time

Optimizing identification of colonic lesions requires a careful and thorough exam of the colon on withdrawal. While this may seem obvious, there is often little focus on the approach to withdrawal. In four chapters on colonoscopy technique from textbooks, the number of pages describing insertion ranged from 20 to 38, while the number of pages focused on withdrawal ranged from 0.5 to 1.5.11-14

A study examining the difference in withdrawal technique between two endoscopists who were known to differ in adenoma miss rates by tandem colonoscopy proposed the scoring system listed in Table 2 that can assess quality of examination on withdrawal. There was a statistically significant difference in quality scores for the two endoscopists, as assessed by expert review of video recordings of their colonoscopies.15

The endoscopist with the lower adenoma miss rate was also found to have an average withdrawal time of 8 minutes and 55 seconds versus 6 minutes and 41 seconds for the endoscopist with the higher adenoma miss rate. A large, community-based study with over 76,000 colonoscopies found a statistically significant correlation between interval colorectal cancer and withdrawal times shorter than 6 minutes.16 However, there was no association between ADR and colorectal cancer, suggesting that, for practices with optimal ADRs (that is, rates greater than 25%), withdrawal time may be a more sensitive marker of quality of colonoscopy than ADR is.16Intuitively, adequate examination of the colon that includes examining the proximal side of folds, washing and suctioning stool, and even repositioning the patient would likely increase withdrawal time. In a 2008 study examining 2,000 screening colonoscopies of 12 endoscopists, those with withdrawal times greater than 6 minutes had significantly higher rates of detecting adenomas and advanced neoplasia, compared with those with faster withdrawal times.17 The average ADR in this group was 28.3%, compared with 11.8% for physicians who had a withdrawal time less than 6 minutes.17 An evaluation of nearly 11,000 colonoscopies done by 43 endoscopists also identified an increase polyp yield with increased withdrawal time.18 These data drive the recommendation for a minimum withdrawal time of 6 minutes, with 2 minutes spent examining each colonic segment.

Bowel preparation

Diagnosis of colonic lesions is dependent on adequate visualization of the colon. Poor bowel preparation can limit the yield of colonoscopy and lead to missed lesions. It also leads to canceled and rescheduled procedures that reduce efficiency, increase cost, and pose an undue burden on the patient.

The quality of bowel preparation should be assessed after washing and suctioning of colonic mucosa has been completed. Adequate preparation is that which allows identification of lesions greater than 5 mm in size.19

Quality of preparation is assessed subjectively by the endoscopists and often listed as excellent, good, fair, or poor. An alternative method of reporting bowel preparation quality is the Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) (Table 3).20 This scoring system allows for a more descriptive assessment of each colonic segment by assigning a score from 0 to 3 for the right, transverse, and left colon, leading to a total score between 0 and 9. The BBPS also helps standardize reporting of bowel preparation. The polyp detection rate associated with a BBPS of 5 or greater was 40%, compared with 24% associated with BBPS less than 5.19 A split-dose bowel preparation regimen with at least half of the preparation ingested on the day of the procedure is recommended to optimize quality of bowel preparation.6

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology task force on quality assurance in endoscopy recommends that bowel preparation should be adequate in 85% of all colonoscopy exams on a per-provider basis.7 One study of completed colonoscopy with inadequate preparation showed an adenoma miss rate of 48%.21 In the setting of inadequate bowel preparation, another study reported 42% of all adenomas detected were only found on repeat colonoscopy. When considering advanced adenomas, there was a 27% miss rate, a relatively high percentage.22

When poor bowel preparation precludes the exam, colonoscopy is appropriately aborted, and the patient asked to return. However, there are situations in which the exam can be completed but the bowel preparation is still inadequate to identify polyps larger than 5 mm. In this setting, the colonoscopy should be repeated with a more aggressive bowel preparation regimen within 1 year.19 Shorter intervals are recommended if advanced neoplasm is detected within an inadequate bowel preparation.19

The appropriate surveillance interval can be unclear when bowel preparation is considered adequate to identify polyps greater than or equal to 5 mm, yet still suboptimal. “Adequate” or “fair” bowel preparation often leads to shorter-than-recommended surveillance intervals because of the concern for small missed lesions. For example, patients with normal colonoscopy results and a fair prep were recommended to undergo a screening colonoscopy in 5 years at 57.4%, while only 23.1% received a 10-year recommendation.23 This increased frequency of colonoscopy leads to increased costs and procedural risks for the patient. Furthermore, a meta-analysis evaluating the effects of bowel preparation reported no significant difference in ADR between adequate and excellent prep.24 These findings suggest that patients with adequate bowel preparation may be followed at guideline-recommended surveillance intervals without significantly affecting colonoscopy quality as measured by ADR.

Endoscopist feedback and report cards

Awareness of quality metrics among individuals and endoscopy practices is crucial to ensuring adequate performance. Several studies have shown improvement with feedback and monitoring of endoscopists.25,26 Some strategies to improve colonoscopy technique and efficiency include having recorded or observed procedures, computer software that measures image resolution/velocity, and scorecards with quality measures. A representation of the scorecards used in our practice is shown in Table 4. Feedback measures both make endoscopists aware of how their performance compares with recommended goals for colonoscopy and help track their improvement. We recommend such feedback should be provided quarterly for most providers and more frequently for providers not meeting benchmarks.

Conclusion

Given we rely on colonoscopy to identify and clear the colon of potential malignancy, it is imperative that we provide high-value exams for our patients. The basis for a quality colonoscopy is complete intubation and careful inspection of the mucosa on withdrawal. Several quality measures are used as surrogates of a good exam such that endoscopists can assess themselves in relation to their peers. These metrics can help us in our goal of remaining mindful during each procedure we are completing and providing the best exam possible.

Dr. Shamsi is a third-year GI fellow. Dr. Malhotra is an assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Dr. Shaukat is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and the GI Section Chief at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center.

References

1. Siegel R et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 Jan-Feb;62(1):10-29.

2. Edwards BK et al. Cancer. 2010 Feb 1;116(3):544-73.

3. Hosokawa O et al. Endoscopy. 2003 Jun;35(6):506-10.

4. Morris EJ et al. Gut. 2015(Aug);64(2):1248-56.

5. Bressler B et al. Gastroenterology. 2004 Aug;127(2):452-6.

6. Rex DK et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 July;12(7):1016-30.

7. Rex DK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jan;81(1):31-53.

8. Anderson J et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb 26;6:e77.

9. Kaminski M et al. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 13;362(19):1795-803.

10. Corley DA et al. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 3;370(4):1298-306.

11. Hunt RH. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 109-46.

12. Waye JD. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 147-78.

13. Williams CB et al. In: Colonoscopy principles & techniques. Edited by Raskin J, Juergen NH. New York: Igaku-Shoin Medical Publishers; 1995. p. 121-42.

14. Baillie J. Colonoscopy. In: Gastrointestinal endoscopy basic principles and practice. Oxford (UK): Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992. p. 63-92.

15. Rex DK. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Jan;51(1):33-6.

16. Shaukat A et al. Gastroenterol. 2015;149(4):952-7.

17. Barclay R et al. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 14;355(24):2533-41.

18. Simmons DT et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(5):AB94.

19. Johnson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(4):543-62.

20. Calderwood A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):686-92.

21. Chokshi R et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Jun;75(6):1197-203.

22. Lebwohl B et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Jun;73(6):1207-14.

23. Menees SB et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Sep;78(3): 510-6.

24. Clark B et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov;109(11):1714-23.

25. Nielson A et al. BMJ Open Gastro. 2017 Jun. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000142.

26. Gurudu S et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Mar;33(3):645-9.

Editor's Note:

As quality metrics are becoming increasingly significant throughout all of medicine, our field is no exception. Recent evidence has demonstrated the importance of quality measures in colonoscopy; understanding, reporting, and improving these metrics has become a hot topic of discussion.

In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, Nabiha Shamsi, Ashish Malhotra, and Aasma Shaukat (University of Minnesota/Minneapolis VAMC) provide an outstanding overview of the evidence as well as recommended goals for important quality metrics in colonoscopy. Ultimately, improving colonoscopy quality amongst all gastroenterologists will increase colonoscopy value and lead to further decreases in the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Introduction

Colonoscopy is a widely used modality to evaluate colorectal cancer because it allows for both identification of early malignancies and removal of precancerous lesions. The increased use of colonoscopy in the last 20 years has been associated with a decline in the incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer.1,2 However, colonoscopy has its limitations. It is an invasive test with inherent risks. Additionally, studies have reported rates of post-colonoscopy cancers, also referred to as interval cancers, of 2%-7%, and miss-rates for adenomas by tandem colonoscopy of 2%-26%.3-5

High-quality exams can maximize the value of colonoscopy, and it is important to consider the factors that contribute to high-quality colonoscopies. While there are many metrics proposed,6,7 here we discuss the most evidence-based ones, outlined in Table 1, along with their goal values.

Cecal intubation rate

A high-quality colonoscopy should include a complete examination of the colon. To achieve this, it is necessary to fully intubate the cecum, passing the colonoscope past the ileocecal valve to examine the medial wall of the cecum.8

There are several factors that may contribute to an incomplete colonoscopy, including bowel preparation, anatomy, body habitus, and endoscopist’s skill. To calculate cecal intubation rate as a quality measure, colonoscopies that are incomplete because of poor bowel preparation, severe colitis, or known obstructing lesion are usually excluded.

The U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer recommends a cecal intubation rate of at least 95% for screening colonoscopy and 90% for all colonoscopies.6 There is an expectation of photodocumentation of the ileocecal valve and appendiceal orifice to establish completion of the colonoscopy.6

Some methods used to assist with cecal intubation include changing patient position, applying abdominal pressure, stiffening the colonoscope, and alternating between adult or pediatric colonoscopes.

Adenoma detection rate

Adenoma detection rate (ADR), is defined as the proportion of patients over the age of 50 years undergoing first-time screening colonoscopies in which at least one adenomatous polyp is detected for a given endoscopist in a given time period.

Adenomas are tracked because clearing the colon of neoplasm is the goal of screening colonoscopies; adenomas are tracked instead of more advanced lesions because the higher frequency of adenomas allows for better tracking of variation between endoscopists. Tracking ADR also utilizes the assumption that, if small lesions are identified, larger ones will be as well.

ADR is the only current quality indicator reported to be significantly associated with the risk of interval cancers. In 2010, a study of 45,000 screening colonoscopies by 186 endoscopists validated the use of ADR, finding that patients who underwent colonoscopy by physicians with ADRs below 20% had hazard ratios for development of postcolonoscopy cancer greater than 10 times higher than patients of physicians with ADRs above 20%.9 However, this study had limited power to establish that cancer protection continues to improve when ADRs rise above 20%. Another study, which evaluated the association of ADR in 224,000 patients undergoing colonoscopies by 136 gastroenterologists, showed each 1% increase in ADR is associated with 3% decrease in the risk of interval CRC and 5% decrease in the risk of fatal interval cancers.10

Most recent guidelines propose an adequate ADR for asymptomatic individuals aged 50 years or older undergoing screening colonoscopy should be greater than 30% in men and greater than 20% in women.6 It remains unknown whether there is a threshold for maximum benefit of ADR, in which a very high ADR is not associated with further protective benefit. The answer to this question may depend on why a low ADR is associated with a higher rate of interval cancers and whether every missed polyp, independent of size, is a potential interval cancer or whether hasty, inadequate, or incomplete examinations of the colon are the underlying concern.

Withdrawal time

Optimizing identification of colonic lesions requires a careful and thorough exam of the colon on withdrawal. While this may seem obvious, there is often little focus on the approach to withdrawal. In four chapters on colonoscopy technique from textbooks, the number of pages describing insertion ranged from 20 to 38, while the number of pages focused on withdrawal ranged from 0.5 to 1.5.11-14

A study examining the difference in withdrawal technique between two endoscopists who were known to differ in adenoma miss rates by tandem colonoscopy proposed the scoring system listed in Table 2 that can assess quality of examination on withdrawal. There was a statistically significant difference in quality scores for the two endoscopists, as assessed by expert review of video recordings of their colonoscopies.15

The endoscopist with the lower adenoma miss rate was also found to have an average withdrawal time of 8 minutes and 55 seconds versus 6 minutes and 41 seconds for the endoscopist with the higher adenoma miss rate. A large, community-based study with over 76,000 colonoscopies found a statistically significant correlation between interval colorectal cancer and withdrawal times shorter than 6 minutes.16 However, there was no association between ADR and colorectal cancer, suggesting that, for practices with optimal ADRs (that is, rates greater than 25%), withdrawal time may be a more sensitive marker of quality of colonoscopy than ADR is.16Intuitively, adequate examination of the colon that includes examining the proximal side of folds, washing and suctioning stool, and even repositioning the patient would likely increase withdrawal time. In a 2008 study examining 2,000 screening colonoscopies of 12 endoscopists, those with withdrawal times greater than 6 minutes had significantly higher rates of detecting adenomas and advanced neoplasia, compared with those with faster withdrawal times.17 The average ADR in this group was 28.3%, compared with 11.8% for physicians who had a withdrawal time less than 6 minutes.17 An evaluation of nearly 11,000 colonoscopies done by 43 endoscopists also identified an increase polyp yield with increased withdrawal time.18 These data drive the recommendation for a minimum withdrawal time of 6 minutes, with 2 minutes spent examining each colonic segment.

Bowel preparation

Diagnosis of colonic lesions is dependent on adequate visualization of the colon. Poor bowel preparation can limit the yield of colonoscopy and lead to missed lesions. It also leads to canceled and rescheduled procedures that reduce efficiency, increase cost, and pose an undue burden on the patient.

The quality of bowel preparation should be assessed after washing and suctioning of colonic mucosa has been completed. Adequate preparation is that which allows identification of lesions greater than 5 mm in size.19

Quality of preparation is assessed subjectively by the endoscopists and often listed as excellent, good, fair, or poor. An alternative method of reporting bowel preparation quality is the Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) (Table 3).20 This scoring system allows for a more descriptive assessment of each colonic segment by assigning a score from 0 to 3 for the right, transverse, and left colon, leading to a total score between 0 and 9. The BBPS also helps standardize reporting of bowel preparation. The polyp detection rate associated with a BBPS of 5 or greater was 40%, compared with 24% associated with BBPS less than 5.19 A split-dose bowel preparation regimen with at least half of the preparation ingested on the day of the procedure is recommended to optimize quality of bowel preparation.6

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology task force on quality assurance in endoscopy recommends that bowel preparation should be adequate in 85% of all colonoscopy exams on a per-provider basis.7 One study of completed colonoscopy with inadequate preparation showed an adenoma miss rate of 48%.21 In the setting of inadequate bowel preparation, another study reported 42% of all adenomas detected were only found on repeat colonoscopy. When considering advanced adenomas, there was a 27% miss rate, a relatively high percentage.22

When poor bowel preparation precludes the exam, colonoscopy is appropriately aborted, and the patient asked to return. However, there are situations in which the exam can be completed but the bowel preparation is still inadequate to identify polyps larger than 5 mm. In this setting, the colonoscopy should be repeated with a more aggressive bowel preparation regimen within 1 year.19 Shorter intervals are recommended if advanced neoplasm is detected within an inadequate bowel preparation.19

The appropriate surveillance interval can be unclear when bowel preparation is considered adequate to identify polyps greater than or equal to 5 mm, yet still suboptimal. “Adequate” or “fair” bowel preparation often leads to shorter-than-recommended surveillance intervals because of the concern for small missed lesions. For example, patients with normal colonoscopy results and a fair prep were recommended to undergo a screening colonoscopy in 5 years at 57.4%, while only 23.1% received a 10-year recommendation.23 This increased frequency of colonoscopy leads to increased costs and procedural risks for the patient. Furthermore, a meta-analysis evaluating the effects of bowel preparation reported no significant difference in ADR between adequate and excellent prep.24 These findings suggest that patients with adequate bowel preparation may be followed at guideline-recommended surveillance intervals without significantly affecting colonoscopy quality as measured by ADR.

Endoscopist feedback and report cards

Awareness of quality metrics among individuals and endoscopy practices is crucial to ensuring adequate performance. Several studies have shown improvement with feedback and monitoring of endoscopists.25,26 Some strategies to improve colonoscopy technique and efficiency include having recorded or observed procedures, computer software that measures image resolution/velocity, and scorecards with quality measures. A representation of the scorecards used in our practice is shown in Table 4. Feedback measures both make endoscopists aware of how their performance compares with recommended goals for colonoscopy and help track their improvement. We recommend such feedback should be provided quarterly for most providers and more frequently for providers not meeting benchmarks.

Conclusion

Given we rely on colonoscopy to identify and clear the colon of potential malignancy, it is imperative that we provide high-value exams for our patients. The basis for a quality colonoscopy is complete intubation and careful inspection of the mucosa on withdrawal. Several quality measures are used as surrogates of a good exam such that endoscopists can assess themselves in relation to their peers. These metrics can help us in our goal of remaining mindful during each procedure we are completing and providing the best exam possible.

Dr. Shamsi is a third-year GI fellow. Dr. Malhotra is an assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Dr. Shaukat is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and the GI Section Chief at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center.

References

1. Siegel R et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 Jan-Feb;62(1):10-29.

2. Edwards BK et al. Cancer. 2010 Feb 1;116(3):544-73.

3. Hosokawa O et al. Endoscopy. 2003 Jun;35(6):506-10.

4. Morris EJ et al. Gut. 2015(Aug);64(2):1248-56.

5. Bressler B et al. Gastroenterology. 2004 Aug;127(2):452-6.

6. Rex DK et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 July;12(7):1016-30.

7. Rex DK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jan;81(1):31-53.

8. Anderson J et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb 26;6:e77.

9. Kaminski M et al. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 13;362(19):1795-803.

10. Corley DA et al. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 3;370(4):1298-306.

11. Hunt RH. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 109-46.

12. Waye JD. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 147-78.

13. Williams CB et al. In: Colonoscopy principles & techniques. Edited by Raskin J, Juergen NH. New York: Igaku-Shoin Medical Publishers; 1995. p. 121-42.

14. Baillie J. Colonoscopy. In: Gastrointestinal endoscopy basic principles and practice. Oxford (UK): Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992. p. 63-92.

15. Rex DK. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Jan;51(1):33-6.

16. Shaukat A et al. Gastroenterol. 2015;149(4):952-7.

17. Barclay R et al. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 14;355(24):2533-41.

18. Simmons DT et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(5):AB94.

19. Johnson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(4):543-62.

20. Calderwood A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):686-92.

21. Chokshi R et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Jun;75(6):1197-203.

22. Lebwohl B et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Jun;73(6):1207-14.

23. Menees SB et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Sep;78(3): 510-6.

24. Clark B et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov;109(11):1714-23.

25. Nielson A et al. BMJ Open Gastro. 2017 Jun. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000142.

26. Gurudu S et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Mar;33(3):645-9.