User login

Renal replacement therapy in the ICU: Vexed questions and team dynamics

More than 5 million patients are admitted to ICUs each year in the United States, and approximately 2% to 10% of these patients develop acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT). AKI-RRT carries high morbidity and mortality (Hoste EA, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1411) and is associated with renal and systemic complications, such as cardiovascular disease. RRT, frequently provided by nephrologists and/or intensivists, is a supportive therapy that can be life-saving when provided to the right patient at the right time. However, several questions related to the provision of RRT still remain, including the optimal timing of RRT initiation, the development of quality metrics for optimal RRT deliverables and monitoring, and the optimal strategy of RRT de-escalation and risk-stratification of renal recovery. Overall, there is paucity of randomized trials and standardized risk-stratification tools that can guide RRT in the ICU.

Current vexed questions of RRT deliverables in the ICU

There is ongoing research aiming to answer critical questions that can potentially improve current standards of RRT.

What is the optimal time of RRT initiation for critically ill patients with AKI?

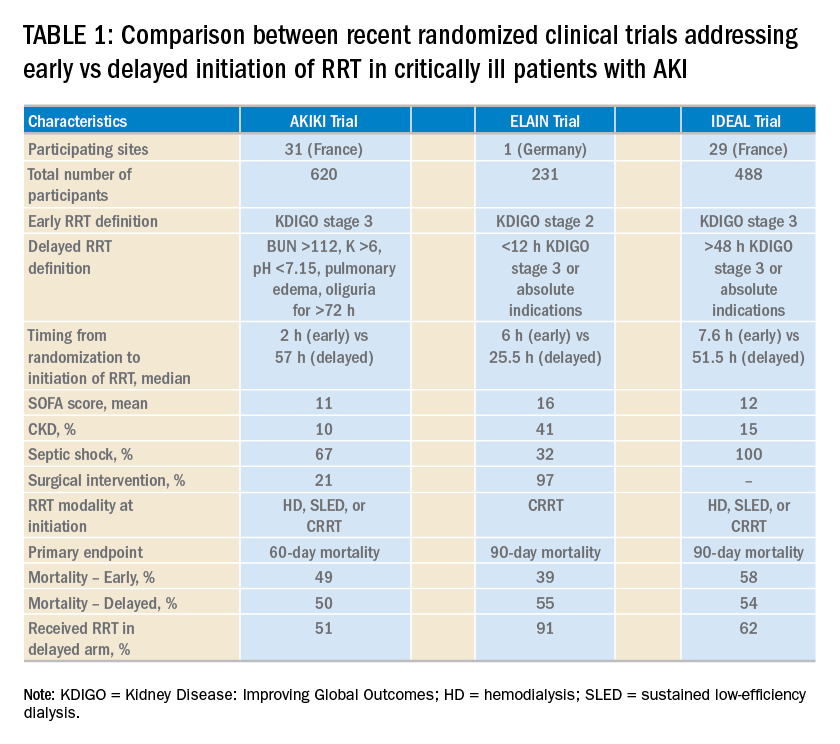

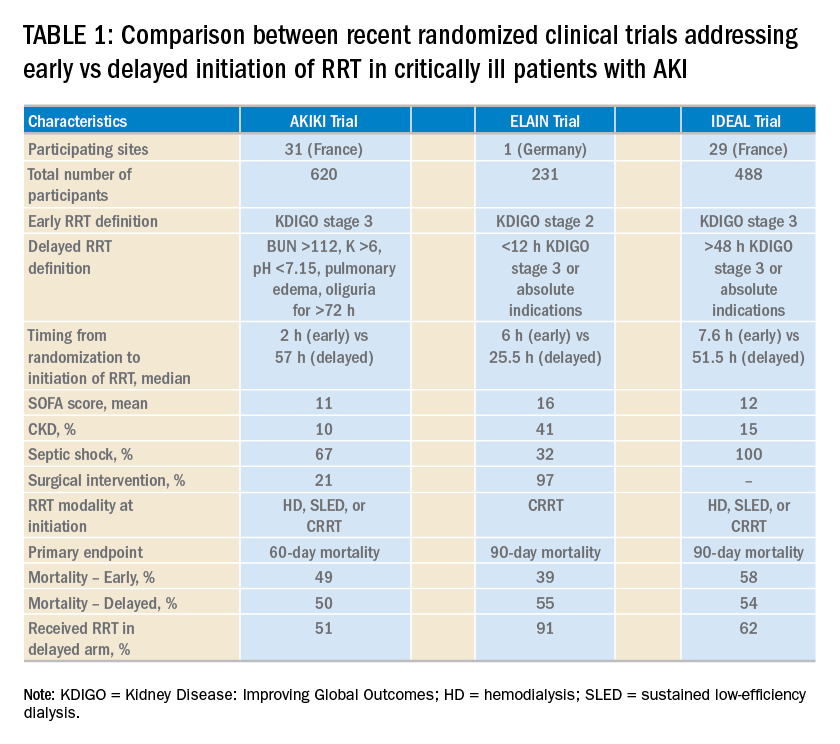

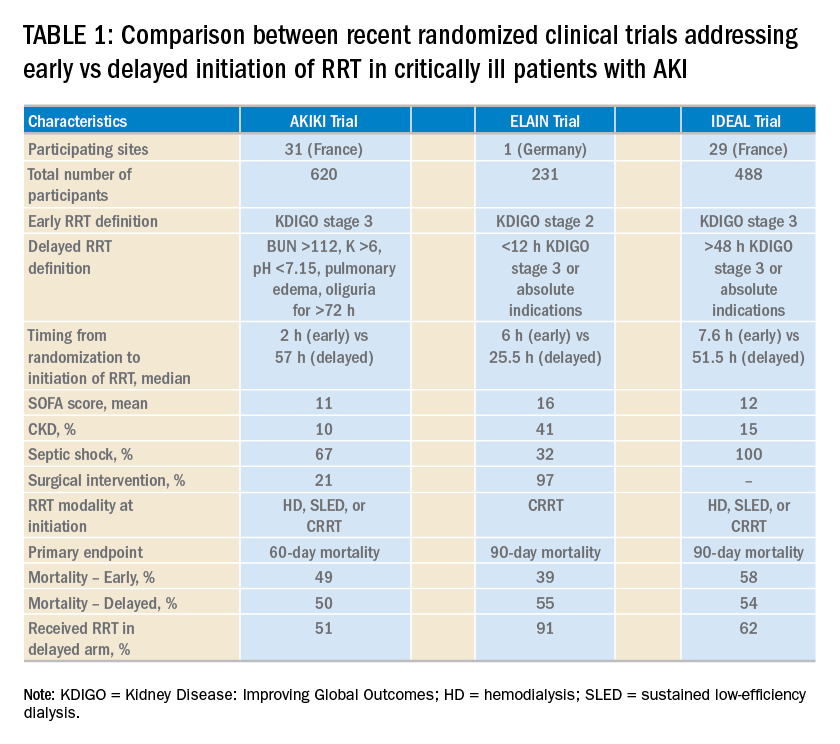

Over the last 2 years, three randomized clinical trials have attempted to address this important question involving heterogeneous ICU populations and distinct research hypotheses and study designs. Two of these studies, AKIKI (Gaudry S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:122) and IDEAL-ICU (Barbar SD, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1431) yielded no significant difference in the primary outcome of 60-day and 90-day all-cause mortality between the early vs delayed RRT initiation strategies, respectively (Table 1). Further, AKIKI showed no difference in RRT dependence at 60 days and higher catheter-related infections and hypophosphatemia in the early initiation arm. It is important to note that IDEAL-ICU was stopped early for futility after the second planned interim analysis with only 56% of patients enrolled (

How can RRT deliverables in the ICU be effectively and systematically monitored?

The provision of RRT to ICU patients with AKI requires an iterative adjustment of the RRT prescription and goals of therapy to accommodate changes in the clinical status with emphasis in hemodynamics, multiorgan failure, and fluid overload (Neyra JA. Clin Nephrol. 2018;90:1). The utilization of static and functional tests or point-of-care ultrasonography to assess hemodynamic variables can be useful. Furthermore, the implementation of customized and automated flowsheets in the electronic health record can facilitate remote monitoring. It is, therefore, essential that the multidisciplinary ICU team develops a process to monitor and ensure RRT deliverables. In this context, the standardization and monitoring of quality metrics (dose, modality, anticoagulation, filter life, downtime, etc) and the development of effective quality management systems are critically important. However, big multicenter data are direly needed to provide insight in this arena.

How can renal recovery be assessed and RRT effectively de-escalated?

The continuous examination of renal recovery in ICU patients with AKI-RRT is mostly based on urine output trend and, if feasible, interdialytic solute control. Sometimes, the transition from continuous RRT to intermittent modalities is necessary in the context of multiorgan recovery and de-escalation of care. However, clinical risk-prediction tools that identify patients who can potentially recover or already exhibit early signs of renal function recovery are needed. Current advances in clinical informatics can help to incorporate time-varying clinical parameters that may be informative for risk-prediction models. In addition, incorporating novel biomarkers of AKI repair and functional tests (eg, furosemide stress test, functional MRI) into these models may further inform these tools and aid the development of clinical decision support systems that enhance interventions to promote AKI recovery (Neyra JA, et al. Nephron. 2018;140: 99).

Is post-AKI outpatient care beneficial for ICU survivors who suffered from AKI-RRT?

Specialized AKI survivor clinics have been implemented in some centers. In general, this outpatient follow-up model includes survivors who suffered from AKI stage 2 or 3, some of them requiring RRT, and tailors individualized interventions for post-AKI complications (preventing recurrent AKI, attenuating incident or progressive CKD). However, the value of this outpatient model needs to be further evaluated with emphasis on clinical outcomes (eg, recurrent AKI, CKD, readmissions, or death) and elements that impact quality of life. This is an area of evolving research and a great opportunity for the nephrology and critical care communities to integrate and enhance post-ICU outpatient care and research collaboration.

Interdisciplinary communication among acute care team members

Two essential elements to provide effective RRT to ICU patients with AKI are: (1) the dynamics of the ICU team (intensivists, nephrologists, pharmacists, nurses, nutritionists, physical therapists, etc) to enhance the delivery of personalized therapy (RRT candidacy, timing of initiation, goals for solute control and fluid removal/regulation, renal recovery evaluation, RRT de-escalation, etc.) and (2) the frequent assessment and adjustment of RRT goals according to the clinical status of the patient. Therefore, effective RRT provision in the ICU requires the development of optimal channels of communication among all members of the acute care team and the systematic monitoring of the clinical status of the patient and RRT-specific goals and deliverables.

Perspective from a nurse and quality improvement officer for the provision of RRT in the ICU

The provision of continuous RRT (CRRT) to critically ill patients requires close communication between the bedside nurse and the rest of the ICU team. The physician typically prescribes CRRT and determines the specific goals of therapy. The pharmacist works closely with the nephrologist/intensivist and bedside nurse, especially in regards to customized CRRT solutions (when indicated) and medication dosing. Because CRRT can alter drug pharmacokinetics, the pharmacist closely and constantly monitors the patient’s clinical status, CRRT prescription, and all active medications. CRRT can also affect the nutritional and metabolic status of critically ill patients; therefore, the input of the nutritionist is necessary. The syndrome of ICU-acquired weakness is commonly encountered in ICU patients and is related to physical immobility. While ICU patients with AKI are already at risk for decreased mobility, the continuous connection to an immobile extracorporeal machine for the provision of CRRT may further contribute to immobilization and can also preclude the provision of optimal physical therapy. Therefore, the bedside nurse should assist the physical therapist for the timely and effective delivery of physical therapy according to the clinical status of the patient.

The clinical scenarios discussed above provide a small glimpse into the importance of developing an interdisciplinary ICU team caring for critically ill patients receiving CRRT. In the context of how integral the specific role of each team member is, it becomes clear that the bedside nurse’s role is not only to deliver hands-on patient care but also the orchestration of collaborative communication among all health-care providers for the effective provision of CRRT to critically ill patients in the ICU.

Dr. Neyra and Ms. Hauschild are with the Department of Internal Medicine; Division of Nephrology; Bone and Mineral Metabolism; University of Kentucky; Lexington, Kentucky.

More than 5 million patients are admitted to ICUs each year in the United States, and approximately 2% to 10% of these patients develop acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT). AKI-RRT carries high morbidity and mortality (Hoste EA, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1411) and is associated with renal and systemic complications, such as cardiovascular disease. RRT, frequently provided by nephrologists and/or intensivists, is a supportive therapy that can be life-saving when provided to the right patient at the right time. However, several questions related to the provision of RRT still remain, including the optimal timing of RRT initiation, the development of quality metrics for optimal RRT deliverables and monitoring, and the optimal strategy of RRT de-escalation and risk-stratification of renal recovery. Overall, there is paucity of randomized trials and standardized risk-stratification tools that can guide RRT in the ICU.

Current vexed questions of RRT deliverables in the ICU

There is ongoing research aiming to answer critical questions that can potentially improve current standards of RRT.

What is the optimal time of RRT initiation for critically ill patients with AKI?

Over the last 2 years, three randomized clinical trials have attempted to address this important question involving heterogeneous ICU populations and distinct research hypotheses and study designs. Two of these studies, AKIKI (Gaudry S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:122) and IDEAL-ICU (Barbar SD, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1431) yielded no significant difference in the primary outcome of 60-day and 90-day all-cause mortality between the early vs delayed RRT initiation strategies, respectively (Table 1). Further, AKIKI showed no difference in RRT dependence at 60 days and higher catheter-related infections and hypophosphatemia in the early initiation arm. It is important to note that IDEAL-ICU was stopped early for futility after the second planned interim analysis with only 56% of patients enrolled (

How can RRT deliverables in the ICU be effectively and systematically monitored?

The provision of RRT to ICU patients with AKI requires an iterative adjustment of the RRT prescription and goals of therapy to accommodate changes in the clinical status with emphasis in hemodynamics, multiorgan failure, and fluid overload (Neyra JA. Clin Nephrol. 2018;90:1). The utilization of static and functional tests or point-of-care ultrasonography to assess hemodynamic variables can be useful. Furthermore, the implementation of customized and automated flowsheets in the electronic health record can facilitate remote monitoring. It is, therefore, essential that the multidisciplinary ICU team develops a process to monitor and ensure RRT deliverables. In this context, the standardization and monitoring of quality metrics (dose, modality, anticoagulation, filter life, downtime, etc) and the development of effective quality management systems are critically important. However, big multicenter data are direly needed to provide insight in this arena.

How can renal recovery be assessed and RRT effectively de-escalated?

The continuous examination of renal recovery in ICU patients with AKI-RRT is mostly based on urine output trend and, if feasible, interdialytic solute control. Sometimes, the transition from continuous RRT to intermittent modalities is necessary in the context of multiorgan recovery and de-escalation of care. However, clinical risk-prediction tools that identify patients who can potentially recover or already exhibit early signs of renal function recovery are needed. Current advances in clinical informatics can help to incorporate time-varying clinical parameters that may be informative for risk-prediction models. In addition, incorporating novel biomarkers of AKI repair and functional tests (eg, furosemide stress test, functional MRI) into these models may further inform these tools and aid the development of clinical decision support systems that enhance interventions to promote AKI recovery (Neyra JA, et al. Nephron. 2018;140: 99).

Is post-AKI outpatient care beneficial for ICU survivors who suffered from AKI-RRT?

Specialized AKI survivor clinics have been implemented in some centers. In general, this outpatient follow-up model includes survivors who suffered from AKI stage 2 or 3, some of them requiring RRT, and tailors individualized interventions for post-AKI complications (preventing recurrent AKI, attenuating incident or progressive CKD). However, the value of this outpatient model needs to be further evaluated with emphasis on clinical outcomes (eg, recurrent AKI, CKD, readmissions, or death) and elements that impact quality of life. This is an area of evolving research and a great opportunity for the nephrology and critical care communities to integrate and enhance post-ICU outpatient care and research collaboration.

Interdisciplinary communication among acute care team members

Two essential elements to provide effective RRT to ICU patients with AKI are: (1) the dynamics of the ICU team (intensivists, nephrologists, pharmacists, nurses, nutritionists, physical therapists, etc) to enhance the delivery of personalized therapy (RRT candidacy, timing of initiation, goals for solute control and fluid removal/regulation, renal recovery evaluation, RRT de-escalation, etc.) and (2) the frequent assessment and adjustment of RRT goals according to the clinical status of the patient. Therefore, effective RRT provision in the ICU requires the development of optimal channels of communication among all members of the acute care team and the systematic monitoring of the clinical status of the patient and RRT-specific goals and deliverables.

Perspective from a nurse and quality improvement officer for the provision of RRT in the ICU

The provision of continuous RRT (CRRT) to critically ill patients requires close communication between the bedside nurse and the rest of the ICU team. The physician typically prescribes CRRT and determines the specific goals of therapy. The pharmacist works closely with the nephrologist/intensivist and bedside nurse, especially in regards to customized CRRT solutions (when indicated) and medication dosing. Because CRRT can alter drug pharmacokinetics, the pharmacist closely and constantly monitors the patient’s clinical status, CRRT prescription, and all active medications. CRRT can also affect the nutritional and metabolic status of critically ill patients; therefore, the input of the nutritionist is necessary. The syndrome of ICU-acquired weakness is commonly encountered in ICU patients and is related to physical immobility. While ICU patients with AKI are already at risk for decreased mobility, the continuous connection to an immobile extracorporeal machine for the provision of CRRT may further contribute to immobilization and can also preclude the provision of optimal physical therapy. Therefore, the bedside nurse should assist the physical therapist for the timely and effective delivery of physical therapy according to the clinical status of the patient.

The clinical scenarios discussed above provide a small glimpse into the importance of developing an interdisciplinary ICU team caring for critically ill patients receiving CRRT. In the context of how integral the specific role of each team member is, it becomes clear that the bedside nurse’s role is not only to deliver hands-on patient care but also the orchestration of collaborative communication among all health-care providers for the effective provision of CRRT to critically ill patients in the ICU.

Dr. Neyra and Ms. Hauschild are with the Department of Internal Medicine; Division of Nephrology; Bone and Mineral Metabolism; University of Kentucky; Lexington, Kentucky.

More than 5 million patients are admitted to ICUs each year in the United States, and approximately 2% to 10% of these patients develop acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT). AKI-RRT carries high morbidity and mortality (Hoste EA, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1411) and is associated with renal and systemic complications, such as cardiovascular disease. RRT, frequently provided by nephrologists and/or intensivists, is a supportive therapy that can be life-saving when provided to the right patient at the right time. However, several questions related to the provision of RRT still remain, including the optimal timing of RRT initiation, the development of quality metrics for optimal RRT deliverables and monitoring, and the optimal strategy of RRT de-escalation and risk-stratification of renal recovery. Overall, there is paucity of randomized trials and standardized risk-stratification tools that can guide RRT in the ICU.

Current vexed questions of RRT deliverables in the ICU

There is ongoing research aiming to answer critical questions that can potentially improve current standards of RRT.

What is the optimal time of RRT initiation for critically ill patients with AKI?

Over the last 2 years, three randomized clinical trials have attempted to address this important question involving heterogeneous ICU populations and distinct research hypotheses and study designs. Two of these studies, AKIKI (Gaudry S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:122) and IDEAL-ICU (Barbar SD, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1431) yielded no significant difference in the primary outcome of 60-day and 90-day all-cause mortality between the early vs delayed RRT initiation strategies, respectively (Table 1). Further, AKIKI showed no difference in RRT dependence at 60 days and higher catheter-related infections and hypophosphatemia in the early initiation arm. It is important to note that IDEAL-ICU was stopped early for futility after the second planned interim analysis with only 56% of patients enrolled (

How can RRT deliverables in the ICU be effectively and systematically monitored?

The provision of RRT to ICU patients with AKI requires an iterative adjustment of the RRT prescription and goals of therapy to accommodate changes in the clinical status with emphasis in hemodynamics, multiorgan failure, and fluid overload (Neyra JA. Clin Nephrol. 2018;90:1). The utilization of static and functional tests or point-of-care ultrasonography to assess hemodynamic variables can be useful. Furthermore, the implementation of customized and automated flowsheets in the electronic health record can facilitate remote monitoring. It is, therefore, essential that the multidisciplinary ICU team develops a process to monitor and ensure RRT deliverables. In this context, the standardization and monitoring of quality metrics (dose, modality, anticoagulation, filter life, downtime, etc) and the development of effective quality management systems are critically important. However, big multicenter data are direly needed to provide insight in this arena.

How can renal recovery be assessed and RRT effectively de-escalated?

The continuous examination of renal recovery in ICU patients with AKI-RRT is mostly based on urine output trend and, if feasible, interdialytic solute control. Sometimes, the transition from continuous RRT to intermittent modalities is necessary in the context of multiorgan recovery and de-escalation of care. However, clinical risk-prediction tools that identify patients who can potentially recover or already exhibit early signs of renal function recovery are needed. Current advances in clinical informatics can help to incorporate time-varying clinical parameters that may be informative for risk-prediction models. In addition, incorporating novel biomarkers of AKI repair and functional tests (eg, furosemide stress test, functional MRI) into these models may further inform these tools and aid the development of clinical decision support systems that enhance interventions to promote AKI recovery (Neyra JA, et al. Nephron. 2018;140: 99).

Is post-AKI outpatient care beneficial for ICU survivors who suffered from AKI-RRT?

Specialized AKI survivor clinics have been implemented in some centers. In general, this outpatient follow-up model includes survivors who suffered from AKI stage 2 or 3, some of them requiring RRT, and tailors individualized interventions for post-AKI complications (preventing recurrent AKI, attenuating incident or progressive CKD). However, the value of this outpatient model needs to be further evaluated with emphasis on clinical outcomes (eg, recurrent AKI, CKD, readmissions, or death) and elements that impact quality of life. This is an area of evolving research and a great opportunity for the nephrology and critical care communities to integrate and enhance post-ICU outpatient care and research collaboration.

Interdisciplinary communication among acute care team members

Two essential elements to provide effective RRT to ICU patients with AKI are: (1) the dynamics of the ICU team (intensivists, nephrologists, pharmacists, nurses, nutritionists, physical therapists, etc) to enhance the delivery of personalized therapy (RRT candidacy, timing of initiation, goals for solute control and fluid removal/regulation, renal recovery evaluation, RRT de-escalation, etc.) and (2) the frequent assessment and adjustment of RRT goals according to the clinical status of the patient. Therefore, effective RRT provision in the ICU requires the development of optimal channels of communication among all members of the acute care team and the systematic monitoring of the clinical status of the patient and RRT-specific goals and deliverables.

Perspective from a nurse and quality improvement officer for the provision of RRT in the ICU

The provision of continuous RRT (CRRT) to critically ill patients requires close communication between the bedside nurse and the rest of the ICU team. The physician typically prescribes CRRT and determines the specific goals of therapy. The pharmacist works closely with the nephrologist/intensivist and bedside nurse, especially in regards to customized CRRT solutions (when indicated) and medication dosing. Because CRRT can alter drug pharmacokinetics, the pharmacist closely and constantly monitors the patient’s clinical status, CRRT prescription, and all active medications. CRRT can also affect the nutritional and metabolic status of critically ill patients; therefore, the input of the nutritionist is necessary. The syndrome of ICU-acquired weakness is commonly encountered in ICU patients and is related to physical immobility. While ICU patients with AKI are already at risk for decreased mobility, the continuous connection to an immobile extracorporeal machine for the provision of CRRT may further contribute to immobilization and can also preclude the provision of optimal physical therapy. Therefore, the bedside nurse should assist the physical therapist for the timely and effective delivery of physical therapy according to the clinical status of the patient.

The clinical scenarios discussed above provide a small glimpse into the importance of developing an interdisciplinary ICU team caring for critically ill patients receiving CRRT. In the context of how integral the specific role of each team member is, it becomes clear that the bedside nurse’s role is not only to deliver hands-on patient care but also the orchestration of collaborative communication among all health-care providers for the effective provision of CRRT to critically ill patients in the ICU.

Dr. Neyra and Ms. Hauschild are with the Department of Internal Medicine; Division of Nephrology; Bone and Mineral Metabolism; University of Kentucky; Lexington, Kentucky.