User login

The quest for a good night’s sleep: An update on pharmacologic therapy for insomnia

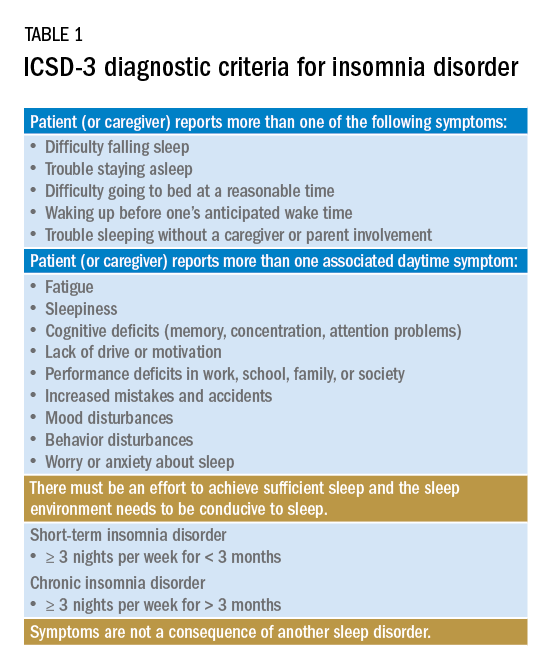

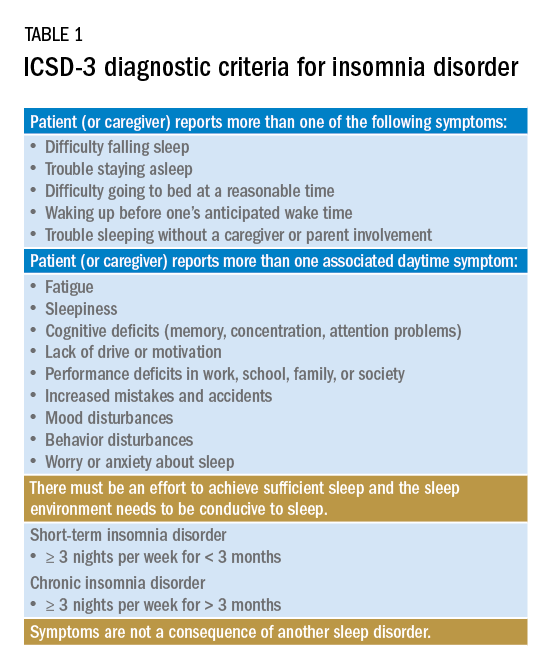

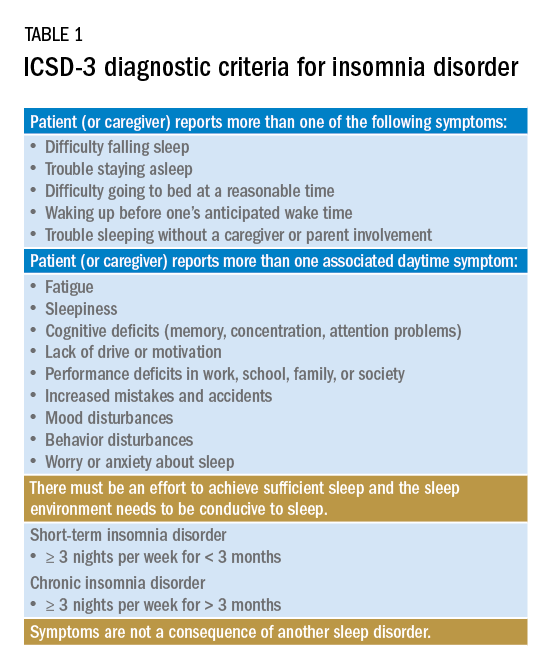

Insomnia is one of the most common complaints in medicine, driving millions of clinic visits each year (Table 1). It is estimated that approximately 30% of individuals report at least short-term insomnia symptoms and 10% report chronic insomnia. These rates are even higher in groups that may be more susceptible to insomnia, including women, the elderly, and those of disadvantaged socioeconomic status (Ohayon MM. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;[2]:97-111). While most patients with insomnia find their sleep difficulties self-resolve within 3 months, a substantial number of patients will find their insomnia to persist for longer and require intervention (Sateia MJ et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13[2]:307-49).

For individuals requiring treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is considered first-line therapy by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine for both acute and chronic insomnia. Unfortunately, obtaining CBT-I for a patient is often a challenge as the number of trained therapists offering this service is limited, resulting in long wait times or, in some cases, a complete lack of access to this treatment option. Judicious use of sedative-hypnotic medications may be a reasonable alternative for patients with insomnia who are unable to undergo CBT-I, who are still symptomatic despite undergoing CBT-I, or, in some cases, as a temporary treatment (Sateia MJ et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13[2]:307-49).

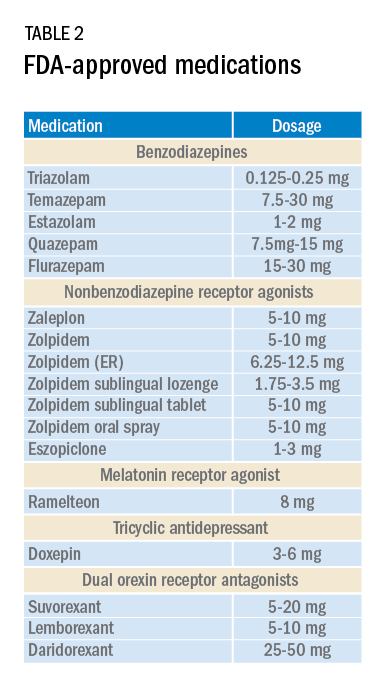

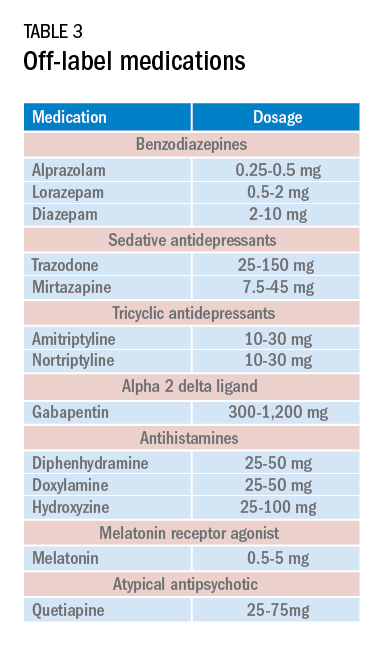

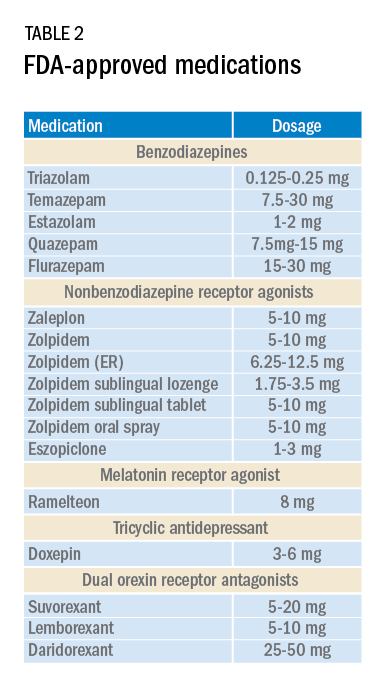

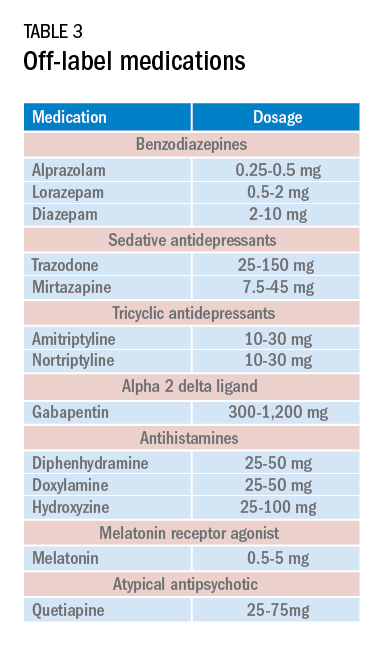

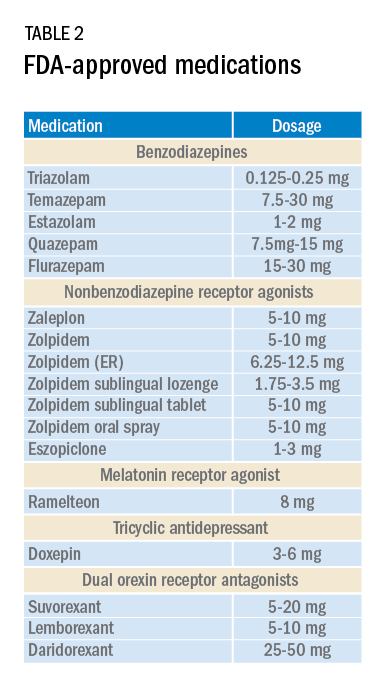

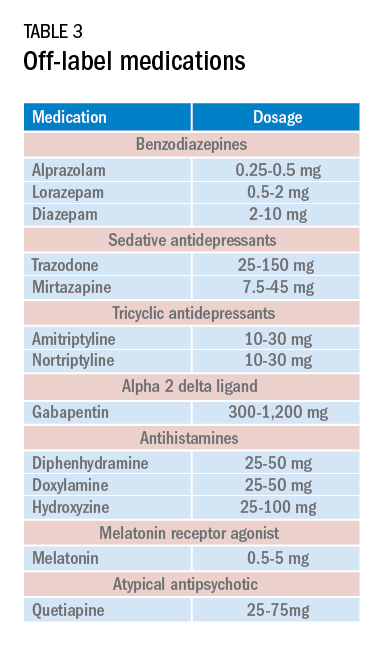

Current medications used to treat insomnia are listed in Tables 2 and 3, some of which carry an FDA approval to be used as a hypnotic, while others are used in an off-label manner.

Cautions abound with use of many of these medications. Common concerns include safety, particularly for elderly patients and long-term use, and the potential for developing tolerance and dependence.

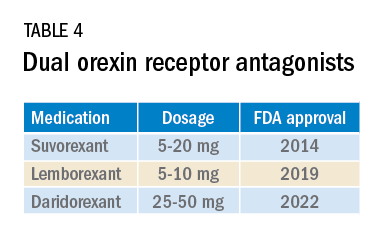

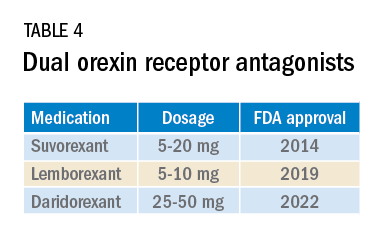

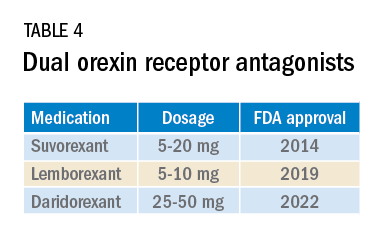

Most medications that have been used for insomnia have been available for decades, but, in recent years, a new class of hypnotics has emerged. Dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs) are the newest class of FDA-approved medications (Table 4).

Orexin is a neuropeptide found primarily in the lateral hypothalamus and binds to the orexin 1 and orexin 2 receptors leading to a number of downstream effects, including stimulating wakefulness. Loss of orexin-generating neurons has been implicated as the cause of type 1 narcolepsy, and antagonism of their effects can facilitate sleep by suppressing wakefulness. The first medication in the DORA class to be FDA-approved was suvorexant in 2014, followed by lemborexant’s FDA approval in 2019. These are both indicated for treating sleep onset and sleep maintenance insomnia and have been shown to improve both subjective and objective measures of sleep. The most common side effects reported for both suvorexant and lemborexant are headache and somnolence, with morning-after sleepiness being a frequent complaint.

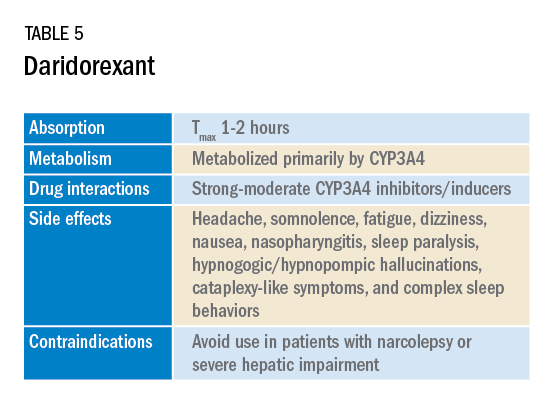

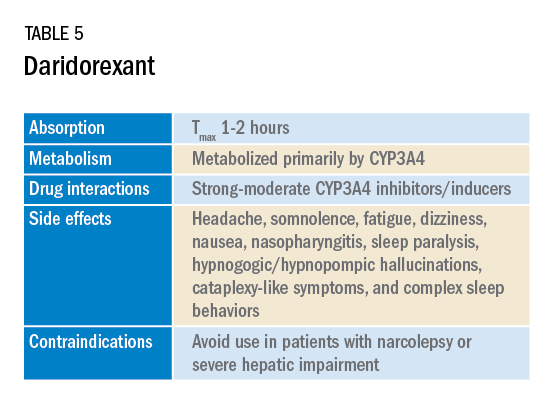

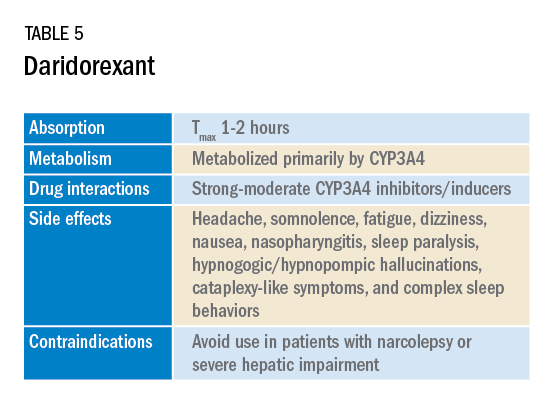

In January 2022, a new medication in the DORA class named daridorexant was approved by the FDA (Table 5).

Daridorexant, like its DORA counterparts, has been shown to have efficacy in improving subjective and objective markers of insomnia. This has included polysomnographic measures of wake after sleep onset and latency to persistent sleep, as well as subjective total sleep time. Importantly, in addition to positive sleep outcomes, improvements with daytime function have also been observed with this medication (Mignot E et al. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21[2]:125-39). Daridorexant’s half-life of approximately 8 hours is shorter than that of the other available DORAs, leading to fewer day-after effects. The combination of effectiveness for sleep initiation and maintenance without daytime impairment distinguishes daridorexant from the other DORAs and even other classes of sleep medication.

Safety, especially in patients of age 65 and older, is an important concern with sleep medication, particularly with respect to polypharmacy, over-sedation, increased fall risk, and cognitive impairment, but daridorexant’s available safety data suggest a favorable safety profile (Zammit G et al. Neurology. 2020;94[21]:e2222-32).

Daridorexant at the highest dose available, 50 mg, did not worsen respiratory function, in terms of the apnea-hypopnea index and oxygen saturation in individuals with mild-moderate obstructive sleep apnea regardless of sleep stage (Boof ML et al. Sleep. 2021;44[6]:zsaa275). However, more safety and longitudinal data are needed to have a fuller understanding of any potential limitations of this medication.

While we continue to recommend CBT-I as the first-line treatment whenever possible for patients with insomnia, not all patients have access to this treatment and not all patients will respond satisfactorily to it. Thus, pharmacologic treatment can continue to play an important role in the management of some patients’ insomnia. Each class of medications used for treating insomnia features a unique constellation of advantages and limitations, meaning that the more available options, the greater the chances of finding an option that will be both effective and safe for a particular patient. The growing DORA class, especially its newest available entrant, daridorexant, represents a continued expansion of the armamentarium of options against insomnia.

Dr. Pelekanos and Dr. Sum-Ping are with the Division of Sleep Medicine, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California.

Insomnia is one of the most common complaints in medicine, driving millions of clinic visits each year (Table 1). It is estimated that approximately 30% of individuals report at least short-term insomnia symptoms and 10% report chronic insomnia. These rates are even higher in groups that may be more susceptible to insomnia, including women, the elderly, and those of disadvantaged socioeconomic status (Ohayon MM. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;[2]:97-111). While most patients with insomnia find their sleep difficulties self-resolve within 3 months, a substantial number of patients will find their insomnia to persist for longer and require intervention (Sateia MJ et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13[2]:307-49).

For individuals requiring treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is considered first-line therapy by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine for both acute and chronic insomnia. Unfortunately, obtaining CBT-I for a patient is often a challenge as the number of trained therapists offering this service is limited, resulting in long wait times or, in some cases, a complete lack of access to this treatment option. Judicious use of sedative-hypnotic medications may be a reasonable alternative for patients with insomnia who are unable to undergo CBT-I, who are still symptomatic despite undergoing CBT-I, or, in some cases, as a temporary treatment (Sateia MJ et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13[2]:307-49).

Current medications used to treat insomnia are listed in Tables 2 and 3, some of which carry an FDA approval to be used as a hypnotic, while others are used in an off-label manner.

Cautions abound with use of many of these medications. Common concerns include safety, particularly for elderly patients and long-term use, and the potential for developing tolerance and dependence.

Most medications that have been used for insomnia have been available for decades, but, in recent years, a new class of hypnotics has emerged. Dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs) are the newest class of FDA-approved medications (Table 4).

Orexin is a neuropeptide found primarily in the lateral hypothalamus and binds to the orexin 1 and orexin 2 receptors leading to a number of downstream effects, including stimulating wakefulness. Loss of orexin-generating neurons has been implicated as the cause of type 1 narcolepsy, and antagonism of their effects can facilitate sleep by suppressing wakefulness. The first medication in the DORA class to be FDA-approved was suvorexant in 2014, followed by lemborexant’s FDA approval in 2019. These are both indicated for treating sleep onset and sleep maintenance insomnia and have been shown to improve both subjective and objective measures of sleep. The most common side effects reported for both suvorexant and lemborexant are headache and somnolence, with morning-after sleepiness being a frequent complaint.

In January 2022, a new medication in the DORA class named daridorexant was approved by the FDA (Table 5).

Daridorexant, like its DORA counterparts, has been shown to have efficacy in improving subjective and objective markers of insomnia. This has included polysomnographic measures of wake after sleep onset and latency to persistent sleep, as well as subjective total sleep time. Importantly, in addition to positive sleep outcomes, improvements with daytime function have also been observed with this medication (Mignot E et al. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21[2]:125-39). Daridorexant’s half-life of approximately 8 hours is shorter than that of the other available DORAs, leading to fewer day-after effects. The combination of effectiveness for sleep initiation and maintenance without daytime impairment distinguishes daridorexant from the other DORAs and even other classes of sleep medication.

Safety, especially in patients of age 65 and older, is an important concern with sleep medication, particularly with respect to polypharmacy, over-sedation, increased fall risk, and cognitive impairment, but daridorexant’s available safety data suggest a favorable safety profile (Zammit G et al. Neurology. 2020;94[21]:e2222-32).

Daridorexant at the highest dose available, 50 mg, did not worsen respiratory function, in terms of the apnea-hypopnea index and oxygen saturation in individuals with mild-moderate obstructive sleep apnea regardless of sleep stage (Boof ML et al. Sleep. 2021;44[6]:zsaa275). However, more safety and longitudinal data are needed to have a fuller understanding of any potential limitations of this medication.

While we continue to recommend CBT-I as the first-line treatment whenever possible for patients with insomnia, not all patients have access to this treatment and not all patients will respond satisfactorily to it. Thus, pharmacologic treatment can continue to play an important role in the management of some patients’ insomnia. Each class of medications used for treating insomnia features a unique constellation of advantages and limitations, meaning that the more available options, the greater the chances of finding an option that will be both effective and safe for a particular patient. The growing DORA class, especially its newest available entrant, daridorexant, represents a continued expansion of the armamentarium of options against insomnia.

Dr. Pelekanos and Dr. Sum-Ping are with the Division of Sleep Medicine, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California.

Insomnia is one of the most common complaints in medicine, driving millions of clinic visits each year (Table 1). It is estimated that approximately 30% of individuals report at least short-term insomnia symptoms and 10% report chronic insomnia. These rates are even higher in groups that may be more susceptible to insomnia, including women, the elderly, and those of disadvantaged socioeconomic status (Ohayon MM. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;[2]:97-111). While most patients with insomnia find their sleep difficulties self-resolve within 3 months, a substantial number of patients will find their insomnia to persist for longer and require intervention (Sateia MJ et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13[2]:307-49).

For individuals requiring treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is considered first-line therapy by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine for both acute and chronic insomnia. Unfortunately, obtaining CBT-I for a patient is often a challenge as the number of trained therapists offering this service is limited, resulting in long wait times or, in some cases, a complete lack of access to this treatment option. Judicious use of sedative-hypnotic medications may be a reasonable alternative for patients with insomnia who are unable to undergo CBT-I, who are still symptomatic despite undergoing CBT-I, or, in some cases, as a temporary treatment (Sateia MJ et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13[2]:307-49).

Current medications used to treat insomnia are listed in Tables 2 and 3, some of which carry an FDA approval to be used as a hypnotic, while others are used in an off-label manner.

Cautions abound with use of many of these medications. Common concerns include safety, particularly for elderly patients and long-term use, and the potential for developing tolerance and dependence.

Most medications that have been used for insomnia have been available for decades, but, in recent years, a new class of hypnotics has emerged. Dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs) are the newest class of FDA-approved medications (Table 4).

Orexin is a neuropeptide found primarily in the lateral hypothalamus and binds to the orexin 1 and orexin 2 receptors leading to a number of downstream effects, including stimulating wakefulness. Loss of orexin-generating neurons has been implicated as the cause of type 1 narcolepsy, and antagonism of their effects can facilitate sleep by suppressing wakefulness. The first medication in the DORA class to be FDA-approved was suvorexant in 2014, followed by lemborexant’s FDA approval in 2019. These are both indicated for treating sleep onset and sleep maintenance insomnia and have been shown to improve both subjective and objective measures of sleep. The most common side effects reported for both suvorexant and lemborexant are headache and somnolence, with morning-after sleepiness being a frequent complaint.

In January 2022, a new medication in the DORA class named daridorexant was approved by the FDA (Table 5).

Daridorexant, like its DORA counterparts, has been shown to have efficacy in improving subjective and objective markers of insomnia. This has included polysomnographic measures of wake after sleep onset and latency to persistent sleep, as well as subjective total sleep time. Importantly, in addition to positive sleep outcomes, improvements with daytime function have also been observed with this medication (Mignot E et al. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21[2]:125-39). Daridorexant’s half-life of approximately 8 hours is shorter than that of the other available DORAs, leading to fewer day-after effects. The combination of effectiveness for sleep initiation and maintenance without daytime impairment distinguishes daridorexant from the other DORAs and even other classes of sleep medication.

Safety, especially in patients of age 65 and older, is an important concern with sleep medication, particularly with respect to polypharmacy, over-sedation, increased fall risk, and cognitive impairment, but daridorexant’s available safety data suggest a favorable safety profile (Zammit G et al. Neurology. 2020;94[21]:e2222-32).

Daridorexant at the highest dose available, 50 mg, did not worsen respiratory function, in terms of the apnea-hypopnea index and oxygen saturation in individuals with mild-moderate obstructive sleep apnea regardless of sleep stage (Boof ML et al. Sleep. 2021;44[6]:zsaa275). However, more safety and longitudinal data are needed to have a fuller understanding of any potential limitations of this medication.

While we continue to recommend CBT-I as the first-line treatment whenever possible for patients with insomnia, not all patients have access to this treatment and not all patients will respond satisfactorily to it. Thus, pharmacologic treatment can continue to play an important role in the management of some patients’ insomnia. Each class of medications used for treating insomnia features a unique constellation of advantages and limitations, meaning that the more available options, the greater the chances of finding an option that will be both effective and safe for a particular patient. The growing DORA class, especially its newest available entrant, daridorexant, represents a continued expansion of the armamentarium of options against insomnia.

Dr. Pelekanos and Dr. Sum-Ping are with the Division of Sleep Medicine, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California.