User login

CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

Surgery may not be the best option for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis, one of the most common causes of chronic pelvic pain. Although laparoscopy has been the traditional approach, new findings show surgery may cause more adhesions than it removes.

Recent research has also focused on endometriosis in adolescents—and the lack of consensus on what treatment is best. Finally, aromatase inhibitors, a new class of hormone-based therapy, look promising for treatment of pain due to endometriosis.

Even adhesion-reducing surgery causes (and may worsen) adhesions

- Surgery avoidance may be the best strategy for evading adhesions

Parker JD, Sinaii N, Segars JH, Godoy H, Winkel C, Stratton P. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic excision of endometriosis and lysis of adhesions. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1457–1461.

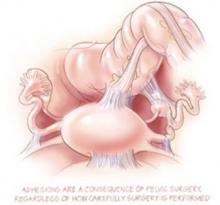

We have known for decades that surgery causes adhesions. The importance of this study is that it demonstrated that careful and thorough surgery designed to remove adhesions and endometriotic implants appears to make no difference in the presence of adhesions 2 years later, and might even worsen adhesions.

This NIH study evaluated 38 women with chronic pelvic pain attributed to endometriosis. At the time of an initial laparoscopy, the locations of endometriosis lesions and adhesions were recorded. All lesions and adhesions were excised using a neodymium-YAG laser, with meticulous hemostasis and careful tissue handling. Ovaries were wrapped in an adhesion barrier (Interceed) after removal of endometriomas; adhesion barriers were otherwise not used. Second-look laparoscopy was performed 2 years later to assess the presence of adhesions.

At the initial surgery, 74% of the 38 patients had adhesions, and at the second-look operation, 82% of the patients had adhesions. Most of the adhesions found at the second operation were not at the original adhesion sites—they were at sites where endometriosis had been excised.

Eighteen endometriomas were excised at the first operation. Although ovaries had been wrapped in an adhesion barrier after excision of the endometriomas, operative site adhesions occurred at 15 of the 18 excision sites. Despite this apparent failure of a barrier to prevent ovarian adhesions, the authors speculated that use of an adhesion barrier after adhesiolysis and after resection of superficial lesions might have prevented some of the adhesions they saw at second-look surgery.

Do adhesions cause pain?

A question not addressed is the role of adhesions in pain; this study did not report pain results. Although the researchers stated that they assumed that adhesions can cause pain, randomized trials have not confirmed this belief.1,2 Even if adhesions do cause pelvic pain, surgery does not appear to be an effective way to reduce adhesions in the long run.

REFERENCES

1. Peters AAW, Trimbos-Kemper GCM, Admiral C, Trimbos JB. A randomized clinical trial on the benefit of adhesiolysis in patients with intraperitoneal adhesions and chronic pelvic pain. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:59-62.

2. Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SC, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: a blinded randomized controlled multi-centre trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1247-1251.

Adolescents get endometriosis, too Should they have laparoscopy?

- Given the propensity of surgery to cause adhesive disease, the fertility of young women may be at risk

Song AH, Advicula AP. Adolescent chronic pelvic pain. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005;18:371–377.

Stavroulis AI, Saridogan E, Creighton SM, Cutner AS. Laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in teenagers. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006; in press.

ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Endometriosis in adolescents. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 310. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:921–927.

Evaluation and treatment of adolescents with chronic pelvic pain can be more challenging than the care of adults with this complaint. Song and Advicula encourage clinicians to consider endometriosis even in the very young adolescent, and they stress attention to the privacy of the adolescent and the importance of letting her decide whether an accompanying parent should be present during an examination.

It is unfortunate that laparoscopy early in the work-up is encouraged, without evidence of the effectiveness of surgery. Oral contraceptives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are recommended as empiric therapy, but progestins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs are discouraged, although there is no evidence that progestins and GnRH analogs are less safe than oral contraceptives in this age group.

A number of conditions that cause chronic pelvic pain in adolescents are described, but missing are discussions of psychiatric disorders and fibromyalgia, which are important causes of chronic pain.

Stavroulis et al is the latest of anecdotal reports claiming that laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in teenagers is safe and effective. In this retrospective review of case records of 31 girls younger than 21 years who underwent laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain, no abnormalities were found in 36% and endometriosis was found in another 36%. The remainder had other findings, including some (ovarian cysts) that are not generally associated with chronic pain, and others (obstructed uterine horn) suggesting that endometriosis may have been missed. Six girls with severe endometriosis had surgical excision, and 5 of the 6 were described as improved after 19 to 112 months of follow-up.

As in most of the literature advocating surgical management of endometriosis, this study had no control group treated with placebo surgery or other therapies. In addition, all the young women who underwent surgery were treated postoperatively with hormonal therapy for an unspecified length of time, making it unclear how much of the pain relief was due to surgery.

What’s wrong with these recommendations?

The ACOG Committee Opinion calls attention to the importance of considering endometriosis as a cause of pain in adolescents. The Opinion offers empiric therapy as an option for the management of young women with chronic pain believed to be due to endometriosis, but does a disservice in promoting laparoscopy as a superior method of diagnosis and treatment. The empiric therapy recommendation is marred by the statement that GnRH analogs should not be used in patients younger than 18 years, with surgery as the only option in this age group. The Committee goes on to recommend that if endometriosis is not visualized at surgery, the patient should be referred for gastrointestinal or urologic evaluation and for pain management services.

Withholding GnRH analogs in women under age 18 is arbitrary and without scientific foundation. The Committee expresses the concern that these agents might interfere with mineralization during this time of maximal bone accretion, and points to the lack of studies of GnRH analog therapy in this age group; however, it is acknowledged that add-back hormone therapy prevents bone mineral loss in the general population of women treated with GnRH analogs.1,2

Although the Committee is reluctant to recommend therapy because data from this age group are inadequate, it recommends laparoscopy despite the lack of data in this age group on either safety or effectiveness of surgery. The one study cited in support of the effectiveness of surgery3 was performed in adults, and compared laparoscopic excision to diagnostic laparoscopy, not to medical therapy. Finally, the Committee ignores danazol, a medication that continues to be useful for some patients.

Does surgery have more adverse consequences in adolescents than in adults? We don’t know. Given the propensity of surgery to cause adhesive disease, however, the fertility of these young women may be at risk. It is particularly disappointing to see the Committee recommending evaluation for gastrointestinal and urologic disease after failed surgery.

The correct approach is the evaluation and treatment of the patient before, and preferably instead of surgery.4

REFERENCES

1. Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

2. Surrey ES, Hornstein MD. Prolonged GnRH agonist and add-back therapy for symptomatic endometriosis: long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:709-719.

3. Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, Holmes M, Finn P, Garry R. Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:878-884.

4. Peters AAW, van Dorst E, Jellis B, van Zuuren E, Hermans J, Trimbos JB. A randomized trial to compare 2 different approaches to women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:740-744.

Medical treatment: Aromatase inhibitors for endometriosis

- It is time for a controlled trial on the question of whether aromatase inhibitors are superior to placebo or other medical treatments for endometriosis

Hefler LA, Grimm C, van Trotsenburg M, Nagele F. Role of the vaginally administered aromatase inhibitor anastrozole in women with rectovaginal endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1033–1036.

Amsterdam LL, Gentry W, Jobanputra S, Wolf M, Rubin SD, Bulun SE. Anastrozole and oral contraceptives: a novel treatment for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:300–304.

It has been widely accepted for decades that endometriosis is estrogen-dependent. More recently, it has been suspected that ectopic endometrium contains aromatase enzyme, which can produce estrogens locally from circulating androgens. This possibility has led to the use of aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of endometriosis.

Two new studies report on the use of the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole, which is marketed for the treatment of breast cancer:

- Dose too low? Hefler and colleagues treated 10 patients with rectovaginal endometriosis, using a low dose (0.25 mg/day) of vaginal anastrozole, without much improvement in symptoms. They suggested that the dose may have been too low.

- Higher dose improved pain. Amsterdam and colleagues reported that pain improved in 15 of 18 patients who used anastrozole at a dosage of 1 mg/day by mouth. An oral contraceptive was given for hot flash control and prevention of bone mineral loss.

These results, along with other reports in the literature, are encouraging. It is now time for a controlled trial to investigate whether aromatase inhibitors are superior to placebo or other medical treatments for endometriosis.

The author has been a consultant for TAP Pharmaceuticals.

Surgery may not be the best option for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis, one of the most common causes of chronic pelvic pain. Although laparoscopy has been the traditional approach, new findings show surgery may cause more adhesions than it removes.

Recent research has also focused on endometriosis in adolescents—and the lack of consensus on what treatment is best. Finally, aromatase inhibitors, a new class of hormone-based therapy, look promising for treatment of pain due to endometriosis.

Even adhesion-reducing surgery causes (and may worsen) adhesions

- Surgery avoidance may be the best strategy for evading adhesions

Parker JD, Sinaii N, Segars JH, Godoy H, Winkel C, Stratton P. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic excision of endometriosis and lysis of adhesions. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1457–1461.

We have known for decades that surgery causes adhesions. The importance of this study is that it demonstrated that careful and thorough surgery designed to remove adhesions and endometriotic implants appears to make no difference in the presence of adhesions 2 years later, and might even worsen adhesions.

This NIH study evaluated 38 women with chronic pelvic pain attributed to endometriosis. At the time of an initial laparoscopy, the locations of endometriosis lesions and adhesions were recorded. All lesions and adhesions were excised using a neodymium-YAG laser, with meticulous hemostasis and careful tissue handling. Ovaries were wrapped in an adhesion barrier (Interceed) after removal of endometriomas; adhesion barriers were otherwise not used. Second-look laparoscopy was performed 2 years later to assess the presence of adhesions.

At the initial surgery, 74% of the 38 patients had adhesions, and at the second-look operation, 82% of the patients had adhesions. Most of the adhesions found at the second operation were not at the original adhesion sites—they were at sites where endometriosis had been excised.

Eighteen endometriomas were excised at the first operation. Although ovaries had been wrapped in an adhesion barrier after excision of the endometriomas, operative site adhesions occurred at 15 of the 18 excision sites. Despite this apparent failure of a barrier to prevent ovarian adhesions, the authors speculated that use of an adhesion barrier after adhesiolysis and after resection of superficial lesions might have prevented some of the adhesions they saw at second-look surgery.

Do adhesions cause pain?

A question not addressed is the role of adhesions in pain; this study did not report pain results. Although the researchers stated that they assumed that adhesions can cause pain, randomized trials have not confirmed this belief.1,2 Even if adhesions do cause pelvic pain, surgery does not appear to be an effective way to reduce adhesions in the long run.

REFERENCES

1. Peters AAW, Trimbos-Kemper GCM, Admiral C, Trimbos JB. A randomized clinical trial on the benefit of adhesiolysis in patients with intraperitoneal adhesions and chronic pelvic pain. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:59-62.

2. Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SC, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: a blinded randomized controlled multi-centre trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1247-1251.

Adolescents get endometriosis, too Should they have laparoscopy?

- Given the propensity of surgery to cause adhesive disease, the fertility of young women may be at risk

Song AH, Advicula AP. Adolescent chronic pelvic pain. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005;18:371–377.

Stavroulis AI, Saridogan E, Creighton SM, Cutner AS. Laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in teenagers. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006; in press.

ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Endometriosis in adolescents. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 310. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:921–927.

Evaluation and treatment of adolescents with chronic pelvic pain can be more challenging than the care of adults with this complaint. Song and Advicula encourage clinicians to consider endometriosis even in the very young adolescent, and they stress attention to the privacy of the adolescent and the importance of letting her decide whether an accompanying parent should be present during an examination.

It is unfortunate that laparoscopy early in the work-up is encouraged, without evidence of the effectiveness of surgery. Oral contraceptives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are recommended as empiric therapy, but progestins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs are discouraged, although there is no evidence that progestins and GnRH analogs are less safe than oral contraceptives in this age group.

A number of conditions that cause chronic pelvic pain in adolescents are described, but missing are discussions of psychiatric disorders and fibromyalgia, which are important causes of chronic pain.

Stavroulis et al is the latest of anecdotal reports claiming that laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in teenagers is safe and effective. In this retrospective review of case records of 31 girls younger than 21 years who underwent laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain, no abnormalities were found in 36% and endometriosis was found in another 36%. The remainder had other findings, including some (ovarian cysts) that are not generally associated with chronic pain, and others (obstructed uterine horn) suggesting that endometriosis may have been missed. Six girls with severe endometriosis had surgical excision, and 5 of the 6 were described as improved after 19 to 112 months of follow-up.

As in most of the literature advocating surgical management of endometriosis, this study had no control group treated with placebo surgery or other therapies. In addition, all the young women who underwent surgery were treated postoperatively with hormonal therapy for an unspecified length of time, making it unclear how much of the pain relief was due to surgery.

What’s wrong with these recommendations?

The ACOG Committee Opinion calls attention to the importance of considering endometriosis as a cause of pain in adolescents. The Opinion offers empiric therapy as an option for the management of young women with chronic pain believed to be due to endometriosis, but does a disservice in promoting laparoscopy as a superior method of diagnosis and treatment. The empiric therapy recommendation is marred by the statement that GnRH analogs should not be used in patients younger than 18 years, with surgery as the only option in this age group. The Committee goes on to recommend that if endometriosis is not visualized at surgery, the patient should be referred for gastrointestinal or urologic evaluation and for pain management services.

Withholding GnRH analogs in women under age 18 is arbitrary and without scientific foundation. The Committee expresses the concern that these agents might interfere with mineralization during this time of maximal bone accretion, and points to the lack of studies of GnRH analog therapy in this age group; however, it is acknowledged that add-back hormone therapy prevents bone mineral loss in the general population of women treated with GnRH analogs.1,2

Although the Committee is reluctant to recommend therapy because data from this age group are inadequate, it recommends laparoscopy despite the lack of data in this age group on either safety or effectiveness of surgery. The one study cited in support of the effectiveness of surgery3 was performed in adults, and compared laparoscopic excision to diagnostic laparoscopy, not to medical therapy. Finally, the Committee ignores danazol, a medication that continues to be useful for some patients.

Does surgery have more adverse consequences in adolescents than in adults? We don’t know. Given the propensity of surgery to cause adhesive disease, however, the fertility of these young women may be at risk. It is particularly disappointing to see the Committee recommending evaluation for gastrointestinal and urologic disease after failed surgery.

The correct approach is the evaluation and treatment of the patient before, and preferably instead of surgery.4

REFERENCES

1. Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

2. Surrey ES, Hornstein MD. Prolonged GnRH agonist and add-back therapy for symptomatic endometriosis: long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:709-719.

3. Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, Holmes M, Finn P, Garry R. Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:878-884.

4. Peters AAW, van Dorst E, Jellis B, van Zuuren E, Hermans J, Trimbos JB. A randomized trial to compare 2 different approaches to women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:740-744.

Medical treatment: Aromatase inhibitors for endometriosis

- It is time for a controlled trial on the question of whether aromatase inhibitors are superior to placebo or other medical treatments for endometriosis

Hefler LA, Grimm C, van Trotsenburg M, Nagele F. Role of the vaginally administered aromatase inhibitor anastrozole in women with rectovaginal endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1033–1036.

Amsterdam LL, Gentry W, Jobanputra S, Wolf M, Rubin SD, Bulun SE. Anastrozole and oral contraceptives: a novel treatment for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:300–304.

It has been widely accepted for decades that endometriosis is estrogen-dependent. More recently, it has been suspected that ectopic endometrium contains aromatase enzyme, which can produce estrogens locally from circulating androgens. This possibility has led to the use of aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of endometriosis.

Two new studies report on the use of the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole, which is marketed for the treatment of breast cancer:

- Dose too low? Hefler and colleagues treated 10 patients with rectovaginal endometriosis, using a low dose (0.25 mg/day) of vaginal anastrozole, without much improvement in symptoms. They suggested that the dose may have been too low.

- Higher dose improved pain. Amsterdam and colleagues reported that pain improved in 15 of 18 patients who used anastrozole at a dosage of 1 mg/day by mouth. An oral contraceptive was given for hot flash control and prevention of bone mineral loss.

These results, along with other reports in the literature, are encouraging. It is now time for a controlled trial to investigate whether aromatase inhibitors are superior to placebo or other medical treatments for endometriosis.

The author has been a consultant for TAP Pharmaceuticals.

Surgery may not be the best option for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis, one of the most common causes of chronic pelvic pain. Although laparoscopy has been the traditional approach, new findings show surgery may cause more adhesions than it removes.

Recent research has also focused on endometriosis in adolescents—and the lack of consensus on what treatment is best. Finally, aromatase inhibitors, a new class of hormone-based therapy, look promising for treatment of pain due to endometriosis.

Even adhesion-reducing surgery causes (and may worsen) adhesions

- Surgery avoidance may be the best strategy for evading adhesions

Parker JD, Sinaii N, Segars JH, Godoy H, Winkel C, Stratton P. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic excision of endometriosis and lysis of adhesions. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1457–1461.

We have known for decades that surgery causes adhesions. The importance of this study is that it demonstrated that careful and thorough surgery designed to remove adhesions and endometriotic implants appears to make no difference in the presence of adhesions 2 years later, and might even worsen adhesions.

This NIH study evaluated 38 women with chronic pelvic pain attributed to endometriosis. At the time of an initial laparoscopy, the locations of endometriosis lesions and adhesions were recorded. All lesions and adhesions were excised using a neodymium-YAG laser, with meticulous hemostasis and careful tissue handling. Ovaries were wrapped in an adhesion barrier (Interceed) after removal of endometriomas; adhesion barriers were otherwise not used. Second-look laparoscopy was performed 2 years later to assess the presence of adhesions.

At the initial surgery, 74% of the 38 patients had adhesions, and at the second-look operation, 82% of the patients had adhesions. Most of the adhesions found at the second operation were not at the original adhesion sites—they were at sites where endometriosis had been excised.

Eighteen endometriomas were excised at the first operation. Although ovaries had been wrapped in an adhesion barrier after excision of the endometriomas, operative site adhesions occurred at 15 of the 18 excision sites. Despite this apparent failure of a barrier to prevent ovarian adhesions, the authors speculated that use of an adhesion barrier after adhesiolysis and after resection of superficial lesions might have prevented some of the adhesions they saw at second-look surgery.

Do adhesions cause pain?

A question not addressed is the role of adhesions in pain; this study did not report pain results. Although the researchers stated that they assumed that adhesions can cause pain, randomized trials have not confirmed this belief.1,2 Even if adhesions do cause pelvic pain, surgery does not appear to be an effective way to reduce adhesions in the long run.

REFERENCES

1. Peters AAW, Trimbos-Kemper GCM, Admiral C, Trimbos JB. A randomized clinical trial on the benefit of adhesiolysis in patients with intraperitoneal adhesions and chronic pelvic pain. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:59-62.

2. Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SC, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: a blinded randomized controlled multi-centre trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1247-1251.

Adolescents get endometriosis, too Should they have laparoscopy?

- Given the propensity of surgery to cause adhesive disease, the fertility of young women may be at risk

Song AH, Advicula AP. Adolescent chronic pelvic pain. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005;18:371–377.

Stavroulis AI, Saridogan E, Creighton SM, Cutner AS. Laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in teenagers. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006; in press.

ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Endometriosis in adolescents. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 310. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:921–927.

Evaluation and treatment of adolescents with chronic pelvic pain can be more challenging than the care of adults with this complaint. Song and Advicula encourage clinicians to consider endometriosis even in the very young adolescent, and they stress attention to the privacy of the adolescent and the importance of letting her decide whether an accompanying parent should be present during an examination.

It is unfortunate that laparoscopy early in the work-up is encouraged, without evidence of the effectiveness of surgery. Oral contraceptives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are recommended as empiric therapy, but progestins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs are discouraged, although there is no evidence that progestins and GnRH analogs are less safe than oral contraceptives in this age group.

A number of conditions that cause chronic pelvic pain in adolescents are described, but missing are discussions of psychiatric disorders and fibromyalgia, which are important causes of chronic pain.

Stavroulis et al is the latest of anecdotal reports claiming that laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in teenagers is safe and effective. In this retrospective review of case records of 31 girls younger than 21 years who underwent laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain, no abnormalities were found in 36% and endometriosis was found in another 36%. The remainder had other findings, including some (ovarian cysts) that are not generally associated with chronic pain, and others (obstructed uterine horn) suggesting that endometriosis may have been missed. Six girls with severe endometriosis had surgical excision, and 5 of the 6 were described as improved after 19 to 112 months of follow-up.

As in most of the literature advocating surgical management of endometriosis, this study had no control group treated with placebo surgery or other therapies. In addition, all the young women who underwent surgery were treated postoperatively with hormonal therapy for an unspecified length of time, making it unclear how much of the pain relief was due to surgery.

What’s wrong with these recommendations?

The ACOG Committee Opinion calls attention to the importance of considering endometriosis as a cause of pain in adolescents. The Opinion offers empiric therapy as an option for the management of young women with chronic pain believed to be due to endometriosis, but does a disservice in promoting laparoscopy as a superior method of diagnosis and treatment. The empiric therapy recommendation is marred by the statement that GnRH analogs should not be used in patients younger than 18 years, with surgery as the only option in this age group. The Committee goes on to recommend that if endometriosis is not visualized at surgery, the patient should be referred for gastrointestinal or urologic evaluation and for pain management services.

Withholding GnRH analogs in women under age 18 is arbitrary and without scientific foundation. The Committee expresses the concern that these agents might interfere with mineralization during this time of maximal bone accretion, and points to the lack of studies of GnRH analog therapy in this age group; however, it is acknowledged that add-back hormone therapy prevents bone mineral loss in the general population of women treated with GnRH analogs.1,2

Although the Committee is reluctant to recommend therapy because data from this age group are inadequate, it recommends laparoscopy despite the lack of data in this age group on either safety or effectiveness of surgery. The one study cited in support of the effectiveness of surgery3 was performed in adults, and compared laparoscopic excision to diagnostic laparoscopy, not to medical therapy. Finally, the Committee ignores danazol, a medication that continues to be useful for some patients.

Does surgery have more adverse consequences in adolescents than in adults? We don’t know. Given the propensity of surgery to cause adhesive disease, however, the fertility of these young women may be at risk. It is particularly disappointing to see the Committee recommending evaluation for gastrointestinal and urologic disease after failed surgery.

The correct approach is the evaluation and treatment of the patient before, and preferably instead of surgery.4

REFERENCES

1. Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

2. Surrey ES, Hornstein MD. Prolonged GnRH agonist and add-back therapy for symptomatic endometriosis: long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:709-719.

3. Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, Holmes M, Finn P, Garry R. Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:878-884.

4. Peters AAW, van Dorst E, Jellis B, van Zuuren E, Hermans J, Trimbos JB. A randomized trial to compare 2 different approaches to women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:740-744.

Medical treatment: Aromatase inhibitors for endometriosis

- It is time for a controlled trial on the question of whether aromatase inhibitors are superior to placebo or other medical treatments for endometriosis

Hefler LA, Grimm C, van Trotsenburg M, Nagele F. Role of the vaginally administered aromatase inhibitor anastrozole in women with rectovaginal endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1033–1036.

Amsterdam LL, Gentry W, Jobanputra S, Wolf M, Rubin SD, Bulun SE. Anastrozole and oral contraceptives: a novel treatment for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:300–304.

It has been widely accepted for decades that endometriosis is estrogen-dependent. More recently, it has been suspected that ectopic endometrium contains aromatase enzyme, which can produce estrogens locally from circulating androgens. This possibility has led to the use of aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of endometriosis.

Two new studies report on the use of the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole, which is marketed for the treatment of breast cancer:

- Dose too low? Hefler and colleagues treated 10 patients with rectovaginal endometriosis, using a low dose (0.25 mg/day) of vaginal anastrozole, without much improvement in symptoms. They suggested that the dose may have been too low.

- Higher dose improved pain. Amsterdam and colleagues reported that pain improved in 15 of 18 patients who used anastrozole at a dosage of 1 mg/day by mouth. An oral contraceptive was given for hot flash control and prevention of bone mineral loss.

These results, along with other reports in the literature, are encouraging. It is now time for a controlled trial to investigate whether aromatase inhibitors are superior to placebo or other medical treatments for endometriosis.

The author has been a consultant for TAP Pharmaceuticals.

Maybe it’s nerves: Common pathway may explain pain

Many gynecologists now recognize that surgery is of little benefit in the initial diagnosis and treatment of the syndrome of chronic pelvic pain, but effective alternatives have not been well established either. Within the last year, however, new research has given us a better understanding of its causes, evaluation, and management. This Update discusses new findings on the following patient care issues:

- How a common nerve pathway may affect chronic pelvic pain patterns

- Transvaginal ultrasound in the evaluation of acute versus chronic pelvic pain

- The placebo effect of surgery

- What we can and cannot expect from endometriosis resection

- The role of adhesions in pain

- Limits of hysterectomy

- Medical therapy

Any nerve plexus injury may lead to pain

Quinn M. Obstetric denervation–gynaecological reinnervation: disruption of the inferior hypogastric plexus in childbirth as a source of gynaecological symptoms. Med Hypoth. 2004;63:390–393.

When we fit together the pieces of the chronic pelvic pain puzzle, a picture emerges that suggests the pelvic organs are connected functionally, not just by anatomical proximity. Recent commercial promotion of drugs for diseases of the bladder and bowel has raised our awareness of interstitial cystitis and irritable bowel syndrome as factors in chronic pelvic pain, and we recognize that bowel and bladder symptoms often accompany gynecologic symptoms, such as dysmenorrhea and vulvodynia. Now, a hypothesis introduced by Martin Quinn suggests disruption of the inferior hypogastric nervous plexus during childbirth may result in reinnervation changes that cause visceral pain years later. He found collateral nervesprouting and a chaotic distribution of nerve fibers when special stains were used on surgical specimens.

According to this hypothesis:

- Cesarean section is not the answer to this childbirth-related injury, because cesarean section injures the nerve plexus.

- Hysterectomy would be effective for chronic pain only if abnormal nerve regeneration is restricted to the uterus.

DIAGNOSISUltrasound is more useful for acute than chronic pain

Clinicians are taught that a good history and physical examination are the most important diagnostic tools in evaluating symptoms, but we often use imaging studies as well, including routine transvaginal ultrasound in the evaluation of pelvic pain. This analysis of published studies identified transvaginal ultrasound as an extension of the bimanual exam, but observed its greatest utility for acute rather than chronic pelvic pain. In chronic pelvic pain, laparoscopic findings, if abnormal, commonly include endometriosis and adhesions—for which transvaginal ultrasound is not very useful unless there is fixation or enlargement of the ovary.

This review describes use of ultrasound for identification of heterogeneous myometrial echotexture, asymmetric uterine enlargement, and subendometrial cysts as features of adenomyosis, and reports a positive predictive value of 68% to 86% in published series.

SURGERYExcision can be effective—so can sham surgery

Some gynecologists still choose surgery as a first-line treatment, although a landmark randomized trial published 14 years ago proved that a nonsurgical approach more effectively resolves chronic pelvic pain symptoms.1 The enthusiasm for surgery is highest when endometriosis is suspected, and some gynecologists still believe that the only adequate treatment is physical removal or destruction of implants.

Pain relief has been attributed to laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis, but cause-and-effect is uncertain, in part because of confounding factors.

For example, in a report on outcomes after ablative therapy for stage 3 or 4 endometriosis with endometriotic cysts, Jones and Sutton2 considered surgery successful because 87.7% of subjects were satisfied 1 year later. This interpretation can be questioned, however, given that patients who did not want to conceive were treated with oral contraceptives or gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog after surgery. The extent to which symptoms responded to the medication rather than the surgery is not known.

Also unknown is the extent to which symptoms respond to the placebo effect of surgery. Sutton and colleagues had previously shown that pain relief 3 months after laser laparoscopy was no greater than after sham surgery,3 but by 6 months, pain relief in the sham surgery group was not sustained, and was lower than in the real surgery group.

The new study by Abbott et al re-addressed the placebo effect of surgery by randomizing 39 women with pain and visible endometriosis implants to either diagnostic laparoscopy or laparoscopic excision of endometriosis. Six months after the surgery, the women had a second laparoscopic procedure during which the extent of endometriosis was reevaluated and visible disease was resected. In other words, all women had resection of endometriosis, although in half of the subjects, the resection was preceded by a sham operation.

Six months after the first operation, 80% of the resection group said they were improved, compared to 32% of the sham surgery group. Six months after the second operation, 83% of those who initially had sham surgery were improved.

This study shows that surgical resection can be effective in reducing pain associated with visible endometriosis, but there are 2 important additional findings:

- The placebo response of 32% is considerable and not to be ignored.

- Despite aggressive excisional surgery with its risks of major organ injury, up to 20% of subjects did not improve.

Is adhesiolysis helpful or not?

Hammoud A, Gago A, Diamond MP. Adhesions in patients with chronic pelvic pain: a role for adhesiolysis? Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1483–1491.

Adhesions may be blamed for chronic pelvic pain, although randomized trials have shown adhesiolysis no more effective than sham surgery.4,5 Hammoud et al hypothesized that adhesions cause pain when they distort normal anatomy and pull on peritoneum, but stress that this idea has not been validated.

Their study found substantial evidence against the theory that adhesions cause pain, and suggests that pain and adhesions may both be due to an underlying process such as endometriosis.

They also review the evidence on the important complications that may occur with attempted surgical adhesiolysis.

Hysterectomy less helpful with preop depression

Hartmann KE, Ma C, Lamvu GM, Langenberg PW, Steege JF, Kjerulff KH. Quality of life and sexual function after hysterectomy in women with preoperative pain and depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:701–709.

Some gynecologists use removal of the uterus as the definitive treatment for chronic pain, although no controlled studies have examined the effectiveness of this operation compared to nonsurgical treatments. Hartmann et al evaluated quality of life and sexual function after hysterectomy in women who had pain, depression, or both pain and depression prior to surgery.

Results were compared between these groups and with women who had neither pain nor depression before surgery. Women with both pain and depression were more likely to have impaired quality of life after hysterectomy than were women with pain or depression alone or women with neither pain nor depression.

Two years later, pelvic pain was still troubling 19.4% of women with preoperative depression and pain, and only 9.3% of women with preoperative pain only.

Hysterectomy led to improvement in many quality of life measures and sexual function in women with pain, depression, or both. The authors concluded, “Overall we do not do harm when we perform hysterectomy for these complex patients.”

That conclusion, however, fails to consider surgical complications, time lost from work or other activities, or monetary costs, which were not evaluated.

There was no nonsurgical comparison group, and the authors point out that their study did not address the possibility that nonsurgical treatments may be as effective or more effective than hysterectomy.

REFERENCES

1. Peters AAW, van Dorst E, Jellis B, van Zuuren E, Hermans J, Trimbos JB. A randomized trial to compare 2 different approaches to women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:740-744.

2. Jones KD, Sutton C. Patient satisfaction and changes in pain scores after ablative laparoscopic surgery for stage III–IV endometriosis and endometriotic cysts. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1086-1090.

3. Sutton CJG, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild and moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:696-700.

4. Peters AAW, Trimbos-Kemper GCM, Admiral C, Trimbos JB. A randomized clinical trial on the benefit of adhesiolysis in patients with intraperitoneal adhesions and chronic pelvic pain. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:59-62.

5. Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SC, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: a blinded randomized controlled multi-centre trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1247-1251.

MEDICAL THERAPYLetrozole for endometriosis?

The discovery that endometriosis implants may contain the aromatase enzyme prompted consideration of aromatase inhibitors as a nonsurgical treatment for endometriosis. These agents, which prevent conversion of androgens to estrogens, are used in the management of breast cancer.

This pilot study evaluated the use of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole in 10 women in whom medical and surgical therapy for endometriosis had failed. Addback therapy with norethindrone acetate was given to prevent the decrease in bone mineral density that might have occurred with letrozole alone. In 9 of the 10 women, pain decreased over the 6 months of the study.

This encouraging result suggests that larger trials with control subjects and longer follow-up will be worthwhile.

Recommendation: Use GnRH agonist

Nasir L, Bope ET. Management of pelvic pain from dysmenorrhea or endometriosis. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17:S43–S47.

Recommendations from the Family Practice Pain Education Project published at the end of 2004 support use of nonsurgical therapies for endometriosis, based in part on the findings of Ling et al,1 which demonstrated the effectiveness of empirical therapy.

ACOG agrees

That recommendation is similar to the nonsurgical approach to chronic pelvic pain recommended in 1999 in an ACOG Practice Bulletin2:

“Therapy with a GnRH agonist is an appropriate approach to the management of women with chronic pelvic pain, even in the absence of surgical confirmation of endometriosis, provided that a detailed initial evaluation fails to demonstrate some other cause of pelvic pain.”

The author is a speaker and consultant for TAP Pharmaceuticals.

1. Ling FW for the Pelvic Pain Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of depot leuprolide in patients with chronic pelvic pain and clinically suspected endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:51-58.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin #11: Medical Management of Endometriosis. Washington, DC: ACOG; December 1999.

Many gynecologists now recognize that surgery is of little benefit in the initial diagnosis and treatment of the syndrome of chronic pelvic pain, but effective alternatives have not been well established either. Within the last year, however, new research has given us a better understanding of its causes, evaluation, and management. This Update discusses new findings on the following patient care issues:

- How a common nerve pathway may affect chronic pelvic pain patterns

- Transvaginal ultrasound in the evaluation of acute versus chronic pelvic pain

- The placebo effect of surgery

- What we can and cannot expect from endometriosis resection

- The role of adhesions in pain

- Limits of hysterectomy

- Medical therapy

Any nerve plexus injury may lead to pain

Quinn M. Obstetric denervation–gynaecological reinnervation: disruption of the inferior hypogastric plexus in childbirth as a source of gynaecological symptoms. Med Hypoth. 2004;63:390–393.

When we fit together the pieces of the chronic pelvic pain puzzle, a picture emerges that suggests the pelvic organs are connected functionally, not just by anatomical proximity. Recent commercial promotion of drugs for diseases of the bladder and bowel has raised our awareness of interstitial cystitis and irritable bowel syndrome as factors in chronic pelvic pain, and we recognize that bowel and bladder symptoms often accompany gynecologic symptoms, such as dysmenorrhea and vulvodynia. Now, a hypothesis introduced by Martin Quinn suggests disruption of the inferior hypogastric nervous plexus during childbirth may result in reinnervation changes that cause visceral pain years later. He found collateral nervesprouting and a chaotic distribution of nerve fibers when special stains were used on surgical specimens.

According to this hypothesis:

- Cesarean section is not the answer to this childbirth-related injury, because cesarean section injures the nerve plexus.

- Hysterectomy would be effective for chronic pain only if abnormal nerve regeneration is restricted to the uterus.

DIAGNOSISUltrasound is more useful for acute than chronic pain

Clinicians are taught that a good history and physical examination are the most important diagnostic tools in evaluating symptoms, but we often use imaging studies as well, including routine transvaginal ultrasound in the evaluation of pelvic pain. This analysis of published studies identified transvaginal ultrasound as an extension of the bimanual exam, but observed its greatest utility for acute rather than chronic pelvic pain. In chronic pelvic pain, laparoscopic findings, if abnormal, commonly include endometriosis and adhesions—for which transvaginal ultrasound is not very useful unless there is fixation or enlargement of the ovary.

This review describes use of ultrasound for identification of heterogeneous myometrial echotexture, asymmetric uterine enlargement, and subendometrial cysts as features of adenomyosis, and reports a positive predictive value of 68% to 86% in published series.

SURGERYExcision can be effective—so can sham surgery

Some gynecologists still choose surgery as a first-line treatment, although a landmark randomized trial published 14 years ago proved that a nonsurgical approach more effectively resolves chronic pelvic pain symptoms.1 The enthusiasm for surgery is highest when endometriosis is suspected, and some gynecologists still believe that the only adequate treatment is physical removal or destruction of implants.

Pain relief has been attributed to laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis, but cause-and-effect is uncertain, in part because of confounding factors.

For example, in a report on outcomes after ablative therapy for stage 3 or 4 endometriosis with endometriotic cysts, Jones and Sutton2 considered surgery successful because 87.7% of subjects were satisfied 1 year later. This interpretation can be questioned, however, given that patients who did not want to conceive were treated with oral contraceptives or gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog after surgery. The extent to which symptoms responded to the medication rather than the surgery is not known.

Also unknown is the extent to which symptoms respond to the placebo effect of surgery. Sutton and colleagues had previously shown that pain relief 3 months after laser laparoscopy was no greater than after sham surgery,3 but by 6 months, pain relief in the sham surgery group was not sustained, and was lower than in the real surgery group.

The new study by Abbott et al re-addressed the placebo effect of surgery by randomizing 39 women with pain and visible endometriosis implants to either diagnostic laparoscopy or laparoscopic excision of endometriosis. Six months after the surgery, the women had a second laparoscopic procedure during which the extent of endometriosis was reevaluated and visible disease was resected. In other words, all women had resection of endometriosis, although in half of the subjects, the resection was preceded by a sham operation.

Six months after the first operation, 80% of the resection group said they were improved, compared to 32% of the sham surgery group. Six months after the second operation, 83% of those who initially had sham surgery were improved.

This study shows that surgical resection can be effective in reducing pain associated with visible endometriosis, but there are 2 important additional findings:

- The placebo response of 32% is considerable and not to be ignored.

- Despite aggressive excisional surgery with its risks of major organ injury, up to 20% of subjects did not improve.

Is adhesiolysis helpful or not?

Hammoud A, Gago A, Diamond MP. Adhesions in patients with chronic pelvic pain: a role for adhesiolysis? Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1483–1491.

Adhesions may be blamed for chronic pelvic pain, although randomized trials have shown adhesiolysis no more effective than sham surgery.4,5 Hammoud et al hypothesized that adhesions cause pain when they distort normal anatomy and pull on peritoneum, but stress that this idea has not been validated.

Their study found substantial evidence against the theory that adhesions cause pain, and suggests that pain and adhesions may both be due to an underlying process such as endometriosis.

They also review the evidence on the important complications that may occur with attempted surgical adhesiolysis.

Hysterectomy less helpful with preop depression

Hartmann KE, Ma C, Lamvu GM, Langenberg PW, Steege JF, Kjerulff KH. Quality of life and sexual function after hysterectomy in women with preoperative pain and depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:701–709.

Some gynecologists use removal of the uterus as the definitive treatment for chronic pain, although no controlled studies have examined the effectiveness of this operation compared to nonsurgical treatments. Hartmann et al evaluated quality of life and sexual function after hysterectomy in women who had pain, depression, or both pain and depression prior to surgery.

Results were compared between these groups and with women who had neither pain nor depression before surgery. Women with both pain and depression were more likely to have impaired quality of life after hysterectomy than were women with pain or depression alone or women with neither pain nor depression.

Two years later, pelvic pain was still troubling 19.4% of women with preoperative depression and pain, and only 9.3% of women with preoperative pain only.

Hysterectomy led to improvement in many quality of life measures and sexual function in women with pain, depression, or both. The authors concluded, “Overall we do not do harm when we perform hysterectomy for these complex patients.”

That conclusion, however, fails to consider surgical complications, time lost from work or other activities, or monetary costs, which were not evaluated.

There was no nonsurgical comparison group, and the authors point out that their study did not address the possibility that nonsurgical treatments may be as effective or more effective than hysterectomy.

REFERENCES

1. Peters AAW, van Dorst E, Jellis B, van Zuuren E, Hermans J, Trimbos JB. A randomized trial to compare 2 different approaches to women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:740-744.

2. Jones KD, Sutton C. Patient satisfaction and changes in pain scores after ablative laparoscopic surgery for stage III–IV endometriosis and endometriotic cysts. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1086-1090.

3. Sutton CJG, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild and moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:696-700.

4. Peters AAW, Trimbos-Kemper GCM, Admiral C, Trimbos JB. A randomized clinical trial on the benefit of adhesiolysis in patients with intraperitoneal adhesions and chronic pelvic pain. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:59-62.

5. Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SC, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: a blinded randomized controlled multi-centre trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1247-1251.

MEDICAL THERAPYLetrozole for endometriosis?

The discovery that endometriosis implants may contain the aromatase enzyme prompted consideration of aromatase inhibitors as a nonsurgical treatment for endometriosis. These agents, which prevent conversion of androgens to estrogens, are used in the management of breast cancer.

This pilot study evaluated the use of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole in 10 women in whom medical and surgical therapy for endometriosis had failed. Addback therapy with norethindrone acetate was given to prevent the decrease in bone mineral density that might have occurred with letrozole alone. In 9 of the 10 women, pain decreased over the 6 months of the study.

This encouraging result suggests that larger trials with control subjects and longer follow-up will be worthwhile.

Recommendation: Use GnRH agonist

Nasir L, Bope ET. Management of pelvic pain from dysmenorrhea or endometriosis. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17:S43–S47.

Recommendations from the Family Practice Pain Education Project published at the end of 2004 support use of nonsurgical therapies for endometriosis, based in part on the findings of Ling et al,1 which demonstrated the effectiveness of empirical therapy.

ACOG agrees

That recommendation is similar to the nonsurgical approach to chronic pelvic pain recommended in 1999 in an ACOG Practice Bulletin2:

“Therapy with a GnRH agonist is an appropriate approach to the management of women with chronic pelvic pain, even in the absence of surgical confirmation of endometriosis, provided that a detailed initial evaluation fails to demonstrate some other cause of pelvic pain.”

The author is a speaker and consultant for TAP Pharmaceuticals.

Many gynecologists now recognize that surgery is of little benefit in the initial diagnosis and treatment of the syndrome of chronic pelvic pain, but effective alternatives have not been well established either. Within the last year, however, new research has given us a better understanding of its causes, evaluation, and management. This Update discusses new findings on the following patient care issues:

- How a common nerve pathway may affect chronic pelvic pain patterns

- Transvaginal ultrasound in the evaluation of acute versus chronic pelvic pain

- The placebo effect of surgery

- What we can and cannot expect from endometriosis resection

- The role of adhesions in pain

- Limits of hysterectomy

- Medical therapy

Any nerve plexus injury may lead to pain

Quinn M. Obstetric denervation–gynaecological reinnervation: disruption of the inferior hypogastric plexus in childbirth as a source of gynaecological symptoms. Med Hypoth. 2004;63:390–393.

When we fit together the pieces of the chronic pelvic pain puzzle, a picture emerges that suggests the pelvic organs are connected functionally, not just by anatomical proximity. Recent commercial promotion of drugs for diseases of the bladder and bowel has raised our awareness of interstitial cystitis and irritable bowel syndrome as factors in chronic pelvic pain, and we recognize that bowel and bladder symptoms often accompany gynecologic symptoms, such as dysmenorrhea and vulvodynia. Now, a hypothesis introduced by Martin Quinn suggests disruption of the inferior hypogastric nervous plexus during childbirth may result in reinnervation changes that cause visceral pain years later. He found collateral nervesprouting and a chaotic distribution of nerve fibers when special stains were used on surgical specimens.

According to this hypothesis:

- Cesarean section is not the answer to this childbirth-related injury, because cesarean section injures the nerve plexus.

- Hysterectomy would be effective for chronic pain only if abnormal nerve regeneration is restricted to the uterus.

DIAGNOSISUltrasound is more useful for acute than chronic pain

Clinicians are taught that a good history and physical examination are the most important diagnostic tools in evaluating symptoms, but we often use imaging studies as well, including routine transvaginal ultrasound in the evaluation of pelvic pain. This analysis of published studies identified transvaginal ultrasound as an extension of the bimanual exam, but observed its greatest utility for acute rather than chronic pelvic pain. In chronic pelvic pain, laparoscopic findings, if abnormal, commonly include endometriosis and adhesions—for which transvaginal ultrasound is not very useful unless there is fixation or enlargement of the ovary.

This review describes use of ultrasound for identification of heterogeneous myometrial echotexture, asymmetric uterine enlargement, and subendometrial cysts as features of adenomyosis, and reports a positive predictive value of 68% to 86% in published series.

SURGERYExcision can be effective—so can sham surgery

Some gynecologists still choose surgery as a first-line treatment, although a landmark randomized trial published 14 years ago proved that a nonsurgical approach more effectively resolves chronic pelvic pain symptoms.1 The enthusiasm for surgery is highest when endometriosis is suspected, and some gynecologists still believe that the only adequate treatment is physical removal or destruction of implants.

Pain relief has been attributed to laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis, but cause-and-effect is uncertain, in part because of confounding factors.

For example, in a report on outcomes after ablative therapy for stage 3 or 4 endometriosis with endometriotic cysts, Jones and Sutton2 considered surgery successful because 87.7% of subjects were satisfied 1 year later. This interpretation can be questioned, however, given that patients who did not want to conceive were treated with oral contraceptives or gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog after surgery. The extent to which symptoms responded to the medication rather than the surgery is not known.

Also unknown is the extent to which symptoms respond to the placebo effect of surgery. Sutton and colleagues had previously shown that pain relief 3 months after laser laparoscopy was no greater than after sham surgery,3 but by 6 months, pain relief in the sham surgery group was not sustained, and was lower than in the real surgery group.

The new study by Abbott et al re-addressed the placebo effect of surgery by randomizing 39 women with pain and visible endometriosis implants to either diagnostic laparoscopy or laparoscopic excision of endometriosis. Six months after the surgery, the women had a second laparoscopic procedure during which the extent of endometriosis was reevaluated and visible disease was resected. In other words, all women had resection of endometriosis, although in half of the subjects, the resection was preceded by a sham operation.

Six months after the first operation, 80% of the resection group said they were improved, compared to 32% of the sham surgery group. Six months after the second operation, 83% of those who initially had sham surgery were improved.

This study shows that surgical resection can be effective in reducing pain associated with visible endometriosis, but there are 2 important additional findings:

- The placebo response of 32% is considerable and not to be ignored.

- Despite aggressive excisional surgery with its risks of major organ injury, up to 20% of subjects did not improve.

Is adhesiolysis helpful or not?

Hammoud A, Gago A, Diamond MP. Adhesions in patients with chronic pelvic pain: a role for adhesiolysis? Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1483–1491.

Adhesions may be blamed for chronic pelvic pain, although randomized trials have shown adhesiolysis no more effective than sham surgery.4,5 Hammoud et al hypothesized that adhesions cause pain when they distort normal anatomy and pull on peritoneum, but stress that this idea has not been validated.

Their study found substantial evidence against the theory that adhesions cause pain, and suggests that pain and adhesions may both be due to an underlying process such as endometriosis.

They also review the evidence on the important complications that may occur with attempted surgical adhesiolysis.

Hysterectomy less helpful with preop depression

Hartmann KE, Ma C, Lamvu GM, Langenberg PW, Steege JF, Kjerulff KH. Quality of life and sexual function after hysterectomy in women with preoperative pain and depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:701–709.

Some gynecologists use removal of the uterus as the definitive treatment for chronic pain, although no controlled studies have examined the effectiveness of this operation compared to nonsurgical treatments. Hartmann et al evaluated quality of life and sexual function after hysterectomy in women who had pain, depression, or both pain and depression prior to surgery.

Results were compared between these groups and with women who had neither pain nor depression before surgery. Women with both pain and depression were more likely to have impaired quality of life after hysterectomy than were women with pain or depression alone or women with neither pain nor depression.

Two years later, pelvic pain was still troubling 19.4% of women with preoperative depression and pain, and only 9.3% of women with preoperative pain only.

Hysterectomy led to improvement in many quality of life measures and sexual function in women with pain, depression, or both. The authors concluded, “Overall we do not do harm when we perform hysterectomy for these complex patients.”

That conclusion, however, fails to consider surgical complications, time lost from work or other activities, or monetary costs, which were not evaluated.

There was no nonsurgical comparison group, and the authors point out that their study did not address the possibility that nonsurgical treatments may be as effective or more effective than hysterectomy.

REFERENCES

1. Peters AAW, van Dorst E, Jellis B, van Zuuren E, Hermans J, Trimbos JB. A randomized trial to compare 2 different approaches to women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:740-744.

2. Jones KD, Sutton C. Patient satisfaction and changes in pain scores after ablative laparoscopic surgery for stage III–IV endometriosis and endometriotic cysts. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1086-1090.

3. Sutton CJG, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild and moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:696-700.

4. Peters AAW, Trimbos-Kemper GCM, Admiral C, Trimbos JB. A randomized clinical trial on the benefit of adhesiolysis in patients with intraperitoneal adhesions and chronic pelvic pain. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:59-62.

5. Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SC, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: a blinded randomized controlled multi-centre trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1247-1251.

MEDICAL THERAPYLetrozole for endometriosis?

The discovery that endometriosis implants may contain the aromatase enzyme prompted consideration of aromatase inhibitors as a nonsurgical treatment for endometriosis. These agents, which prevent conversion of androgens to estrogens, are used in the management of breast cancer.

This pilot study evaluated the use of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole in 10 women in whom medical and surgical therapy for endometriosis had failed. Addback therapy with norethindrone acetate was given to prevent the decrease in bone mineral density that might have occurred with letrozole alone. In 9 of the 10 women, pain decreased over the 6 months of the study.

This encouraging result suggests that larger trials with control subjects and longer follow-up will be worthwhile.

Recommendation: Use GnRH agonist

Nasir L, Bope ET. Management of pelvic pain from dysmenorrhea or endometriosis. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17:S43–S47.

Recommendations from the Family Practice Pain Education Project published at the end of 2004 support use of nonsurgical therapies for endometriosis, based in part on the findings of Ling et al,1 which demonstrated the effectiveness of empirical therapy.

ACOG agrees

That recommendation is similar to the nonsurgical approach to chronic pelvic pain recommended in 1999 in an ACOG Practice Bulletin2:

“Therapy with a GnRH agonist is an appropriate approach to the management of women with chronic pelvic pain, even in the absence of surgical confirmation of endometriosis, provided that a detailed initial evaluation fails to demonstrate some other cause of pelvic pain.”

The author is a speaker and consultant for TAP Pharmaceuticals.

1. Ling FW for the Pelvic Pain Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of depot leuprolide in patients with chronic pelvic pain and clinically suspected endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:51-58.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin #11: Medical Management of Endometriosis. Washington, DC: ACOG; December 1999.

1. Ling FW for the Pelvic Pain Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of depot leuprolide in patients with chronic pelvic pain and clinically suspected endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:51-58.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin #11: Medical Management of Endometriosis. Washington, DC: ACOG; December 1999.

New insight on an enduring enigma

The most important new advance in chronic pelvic pain is recognition that this complaint often does not represent an anatomical disorder that can be seen, photographed, or excised away. It is a syndrome—a group of related disorders associated with abnormal pain processing. The abnormal pain processing may relate to other symptoms affecting mood, sleep, and autonomic function. The term for this array of complaints—chronic pelvic pain syndrome–reinforces the concept that a group of disorders produces the subjective experience of pain.

This new understanding is steering us toward therapeutic strategies that may be more helpful than multiple uncoordinated treatments at the hands of different specialists—the unfortunate experience of too many women.

Clinicians have long understood that for many patients, there is no clear diagnosis. Patients become frustrated with clinicians’ apparent inability to help, or even take their complaints seriously. Doctor-shopping results in multiple tests, medication trials, and surgery. This chain of events stems from the traditional anatomic model of disease, which attributes pain to an organ or tissue abnormality that surgical correction might resolve.

Key findings. Clues that the anatomic model is inadequate have been a part of gynecologic teaching for decades, but recent studies confirm these impressions about chronic pelvic pain:

- Anatomic features noted at surgery may not give reliable information about the cause;

- The effect of surgical treatment is similar to placebo, at least short-term;

- A history of abuse is common.

‘Difficult’ patient or other disease was blamed when surgery failed. The traditional approach was to seek an anatomic abnormality such as endometriosis, adhesions, or pelvic congestion, and treat the abnormality with surgical removal of implants, scar tissue, or the pelvic organs altogether.

(The anatomic model still applies to acute pelvic pain; ruptured ovarian cyst, ectopic pregnancy, and appendicitis are highest on the list of diagnostic possibilities.)

Surgeons were convinced that their operations were successful, largely because they characterized cases that failed to get better as evidence of nongynecologic disease or a patient who simply wanted to be difficult.

Pivotal study: ‘Integrated’ treatment achieved better results. One of the earliest clues that surgery might not be the best approach to chronic pelvic pain came from a study of 106 patients randomized to 2 different strategies1:

- In the “standard” approach, laparoscopy was used early, and patients with no anatomic abnormalities were then evaluated for other problems, such as psychological disorders.

- In the “integrated” approach, the pain experience was thought to have 4 components: nociception, pain sensation (which includes processing), suffering, and pain behavior. This approach included psychological and physical therapy as well as evaluation for anatomic abnormalities, generally using nonsurgical methods.

Among the 57 women randomized to the integrated approach, 5 (9%) underwent surgery, compared with 100% of the group randomized to standard therapy. One year later, 75% of the women assigned to the integrated approach reported improvement in pain, compared with 41% of those in the standard group.

In both groups, associated symptoms were common at the onset of therapy, including backache, nausea, malaise, headache, and insomnia. These symptoms were more likely to improve with the integrated approach.

Initial strategy: Avoid surgery

Winkel CA. Evaluation and management of women with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:397-408.

Avoidance of surgery can be recommended except perhaps in patients with a mass or discrete and localized abnormalities (eg, tender uterosacral nodule with deep dyspareunia as the only complaint). This strategy challenges the anatomic model of chronic pelvic pain, but is consistent with challenges to the anatomic model of chronic pain at other sites, such as chronic back pain.

Empiric medical therapy may be preferable in women believed, clinically, to have endometriosis without a mass or who wish to get pregnant right away, Dr. Winkel noted.

Many diagnoses can be made in women with chronic pelvic pain, in addition to endometriosis (eg, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, vulvodynia, fibromyalgia, and somatization disorder); these may reflect different manifestations of the same disorder of pain processing, which is often associated with mood and sleep abnormalities. Therapy to improve sleep, physical conditioning, and coping strategies appears to be more helpful than surgery as an initial approach.

Visual and histologic diagnoses of endometriosis at odds

Walter AJ, Hentz JG, Magtibay PM, Cornella JL, Magrina JF. Endometriosis: correlation between histologic and visual findings at laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1407-1413.

Stratton P, Winkel CA, Sinaii N, Merino MJ, Zimmer C, Nieman LK. Location, color, size, depth and volume may predict endometriosis in lesions resected at surgery. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:743-749.

Stratton P, Winkel C, Premkumar A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, and histopathologic examination for the detection of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1078-1085.

Three recent studies assess the discrepancies between visual and histologic evidence of endometriosis in women with chronic pelvic pain. Earlier studies had indicated that visual diagnosis is not equivalent to histologic diagnosis, and that failure to see endometriosis does not mean it is not there.

In all 3 studies, visible lesions that appeared to be endometriosis were excised and evaluated by a pathologist.

- Walter et al found that 12 of 37 women with visible lesions had no histologic evidence of endometriosis; the positive predictive value of visualized endometriosis was 62%.

- Stratton et al found a similar 61% of 314 lesions believed on visual inspection to be endometriosis were histologically confirmed. Of 44 women with visual criteria suggesting endometriosis, 6 (14%) were unconfirmed by histology. This discrepancy was noted in women considered upon inspection to have “mild” disease, of whom 5 of 13 (38%) had no histologic evidence.

Does a diagnosis benefit the patient? In a commentary, Dr. Frank Ling2 questioned whether histologic or visual diagnoses are useful. After all, he argued, histologic diagnosis of endometriosis does not prove it caused the pain—prior studies showed a high prevalence of endometriosis in asymptomatic women.

Focusing on what the inside of the pelvis looks like, whether through a laparoscope or the pathologist’s microscope, may leave the woman with chronic pain without relief. Ling made a case for empiric medical treatment of endometriosis, without surgery.

Sham surgery: A potent placebo

Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SC, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: a blinded randomised controlled multi-centre trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1247-1251.

In chronic pelvic pain, the placebo effect can be potent—another indication that the anatomic model is not the answer. In the mid-90s, Sutton et al3 found equal responses to sham surgery and laser laparoscopy at 3 months postoperatively in patients with endometriosis-associated pain—but laser laparoscopy had an advantage over sham surgery at 6 months postoperatively.

Swank et al compared laparoscopic adhesiolysis with sham surgery in 100 adults (87% women) with chronic abdominal pain without intestinal stricture. At 1 year, 27% were pain-free or much improved, and there was no difference in visual analog score improvement, regardless of type of surgery. They concluded that abdominal pain can improve after surgery, but the benefit is not likely due to adhesiolysis.

In both groups, as in the Sutton study, reduced pain was maximal at 3 months and somewhat less by 6 months after surgery, supporting the likelihood of a placebo effect.

Possibly, the response to surgery was due in part to reduced anxiety after surgery excluded cancer, yet the mean number of prior operations was almost 3, suggesting that many of these patients had already had the opportunity to be reassured by benign operative findings.

Past abuse: The mind-body link

Lampe A, Doering S, Rumpold G, et al. Childhood pain syndromes and their relation to childhood abuse and stressful life events. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:361-367.

It has been noted for years that women with chronic pelvic pain are more likely to have a history of sexual abuse than women without chronic pelvic pain. In a study of the chronic pain/abuse relationship, Lampe et al found “complex mutual interactions among childhood abuse, stressful life events, depression, and the occurrence of chronic pain,” and urged clinicians to consider these factors when treating patients.

It is clear that chronic pain syndromes and abuse are linked, but there is disagreement on whether pelvic pain is associated with sexual abuse more than other abuse, or if sexual abuse is associated more with pelvic pain than chronic pain at other sites.

These associations were once explained as physically and psychologically traumatic events being reenacted through illness behaviors. A theory more consistent with current views of pain-processing disorders is that physical or psychological trauma may “kindle” abnormalities of neurotransmitter function to which a patient is genetically predisposed. This model is analogous to the view that depression is a genetic disorder kindled by a major loss or adverse life event.

Such a view requires that we relinquish the mind-body dualism first proposed by Descartes in the 17th century, long before we recognized that neurotransmitters mediate mood as well as motor function, and that life events can alter the chemistry of the brain.

Dr. Scialli reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Peters AAW, van Dorst E, Jellis B, van Zuuren E, Hermans J, Trimbos JB. A randomized trial to compare 2 different approaches in women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:740-744.

2. Ling FW. Randomized controlled trial of depot leuprolide in patients with chronic pelvic pain and clinically suspected endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:51-58.

3. Sutton CJG, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild and moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:696-700.

The most important new advance in chronic pelvic pain is recognition that this complaint often does not represent an anatomical disorder that can be seen, photographed, or excised away. It is a syndrome—a group of related disorders associated with abnormal pain processing. The abnormal pain processing may relate to other symptoms affecting mood, sleep, and autonomic function. The term for this array of complaints—chronic pelvic pain syndrome–reinforces the concept that a group of disorders produces the subjective experience of pain.

This new understanding is steering us toward therapeutic strategies that may be more helpful than multiple uncoordinated treatments at the hands of different specialists—the unfortunate experience of too many women.

Clinicians have long understood that for many patients, there is no clear diagnosis. Patients become frustrated with clinicians’ apparent inability to help, or even take their complaints seriously. Doctor-shopping results in multiple tests, medication trials, and surgery. This chain of events stems from the traditional anatomic model of disease, which attributes pain to an organ or tissue abnormality that surgical correction might resolve.

Key findings. Clues that the anatomic model is inadequate have been a part of gynecologic teaching for decades, but recent studies confirm these impressions about chronic pelvic pain:

- Anatomic features noted at surgery may not give reliable information about the cause;

- The effect of surgical treatment is similar to placebo, at least short-term;

- A history of abuse is common.

‘Difficult’ patient or other disease was blamed when surgery failed. The traditional approach was to seek an anatomic abnormality such as endometriosis, adhesions, or pelvic congestion, and treat the abnormality with surgical removal of implants, scar tissue, or the pelvic organs altogether.