User login

Which to treat first: Comorbid anxiety or alcohol disorder?

Men and women with anxiety disorders are at three times the general population’s risk of being alcohol-dependent (Table),1 and those who seek treatment for an anxiety disorder are at even higher risk of alcohol disorder.2,3 This comorbidity can complicate treatment attempts if either disorder remains unaddressed, leading to increased relapse risk and multiple treatment episodes.

Based on our research and clinical work in helping patients with comorbid alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders,2,4-6 this article describes:

- potential relationships between anxiety disorders and alcohol disorder

- pros and cons of 3 approaches to treating this comorbidity

- how to identify and address alcohol disorder in patients with anxiety disorders, depending on available resources.

Table

Comorbidity rates of anxiety disorders and alcohol dependence*

| Anxiety disorder | Odds ratio for having alcohol dependence | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |

| Any | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Panic disorder | 3.8 | 3.7 |

| Social phobia | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| Specific phobia | 2.8 | 2.9 |

| * Numbers indicate odds of having alcohol dependence when the anxiety disorder is present vs absent. | ||

| Source: 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), reference 1 | ||

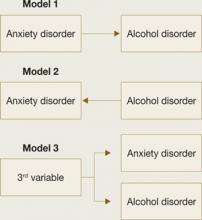

3 comorbidity models

The most common understanding of this comorbidity (Figure 1) is that having an anxiety disorder predisposes one to develop an alcohol or substance use disorder via self-medication—using alcohol or drugs to modulate anxiety and negative affect.7-9 However, substance use disorder experts have argued that the social, occupational, and physiologic effects of substance use can generate new anxiety symptoms in vulnerable individuals.10 In other words, physiologic and/or environmental disruptions from chronic alcohol or substance use could promote conditions and circumstances in which anxiety symptoms are more likely to emerge or worsen.

Although DSM-IV-TR does not delve into the causes of mental disorders, it states that substance use can cause or “induce” an anxiety syndrome with symptoms that resemble or are identical to those of the various anxiety syndromes that are not related to substance disorder (Box).11,12

Alternatively, the idea that a third factor can serve as a common cause for both conditions fits with the view that substance use disorder and anxiety disorder can be phenotypic expressions of a common underlying genetic/physiologic liability.13

Finally, these models are not mutually exclusive. Anxiety symptoms or substance use could cause or aggravate the other.

Figure 1

Hypothetical models of comorbidity

Which comes first?

Anxiety disorder typically begins before a substance use disorder in comorbid cases, although some studies have reported the opposite pattern or roughly simultaneous onset of both disorders.2

Using a prospective method in college students, we found that the risk of developing alcohol dependence for the first time as a junior or senior more than tripled among students who had an anxiety diagnosis as a freshman.14 We also found, however, that students who were alcohol dependent as freshman were 4 times more likely than other freshman to develop an anxiety disorder for the first time within the next 6 years.

In short, having either an anxiety or alcohol disorder earlier in life appears to increase the probability of developing the other later. This finding supports the idea that the types of associations that link pathologic anxiety and substance use vary among individuals and, perhaps, within individuals over time.

3 treatment approaches

Treating 1 of the comorbid conditions—anxiety or alcohol disorder—does not tend to resolve the other.3,15 This suggests that therapies aimed at treating a single disorder are not satisfactory for treating comorbid cases. Possible multi-focused approaches include:

- serial (or sequential) approach—treating comorbid disorders one at a time

- parallel approach—providing simultaneous but separate treatments for each comorbidity

- integrated approach—providing one treatment that focuses on both comorbid disorders, especially as they interact with one another.

Each has strengths and weaknesses, and the approach you choose for your patient may depend on clinical circumstances and available resources.

Serial treatment has the structure to empirically evaluate whether the initially untreated comorbid condition is resolved by treating the other condition. For example, you could treat an anxiety disorder as usual and refer the patient for alcohol disorder treatment only if drinking remains an active problem following anxiety treatment. This approach also allows you to use well-established treatment systems, programs, and specialists as usual.

One disadvantage to the serial approach, however, is that the initially untreated comorbid disorder could undermine the resolution of the treated disorder. We found, for example, that treating either the anxiety or the alcohol disorder alone fails to resolve the comorbid condition and might leave a patient vulnerable to relapse before serial treatment can be completed.3,15

When implementing a serial treatment, it is not always clear which disorder to treat first. Distinguishing comorbid disorders as “primary” or “secondary” often is done inconsistently and imprecisely, so treatment decisions based on these terms can be erroneous. Using the order of disorder onset also is an unreliable guide to which disorder is in priority need of treatment.7,16

Based on our experience and research, where and why the comorbid patient presents for treatment should be factored heavily in these treatment decisions. For example, individuals seeking anxiety treatment who have a comorbid alcohol use disorder typically possess little insight into their drinking problem and a frank resistance to clinician-driven attempts to modify their drinking behavior. We would expect a similar reaction from patients presenting for alcohol disorder treatment who are told they must first obtain psychiatric treatment for anxiety symptoms. The serial approach often necessitates that patients be treated initially for the problem for which they present and then referred afterward for the comorbid condition as needed.

In an open-label pilot treatment study of 5 subjects with social anxiety disorder and a co-occurring alcohol use disorder (C.L.R., S.W.B., unpublished data, 2007), we first treated the anxiety disorder with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine, up to 60 mg/d. After 6 weeks, we addressed the comorbid alcohol problem using a brief alcohol intervention. This approach met with little or no resistance to reduce drinking—all 5 subjects successfully decreased their alcohol consumption, and none dropped out of treatment. A controlled follow-up trial is planned to provide empiric support for serial treatment of anxiety and alcohol use disorders in mental health treatment settings.

DSM-IV-TR describes an anxiety disorder as independent from a coexisting substance use disorder only if the anxiety disorder:

- began distinctly before the substance use disorder

- or persisted during periods of extended abstinence (>1 month) from substance use/abuse.

Otherwise, substance abuse is presumed to have induced the anxiety disorder. This perspective implies that no specific treatment beyond drug/alcohol abstinence is required to resolve a substance-induced anxiety disorder.

In a large community-based sample, Grant et al11 found that <0.5% of individuals with comorbid anxiety and substance abuse met the strictly defined DSM-IV-TR criteria for a substance-induced anxiety disorder. Cases in which a comorbid anxiety disorder resolved during periods of substance abuse abstinence were especially rare. This observation suggests that substance-induced anxiety syndrome as defined by DSM-IV-TR is very rare in clinical practice.

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria do not recognize an “anxiety-induced substance use disorder,” in which pathologic anxiety might induce a substance use disorder. Conceptually, however, this idea is as reasonable as substance-induced anxiety disorder and fits within the self-medication model.12

Parallel treatments, which can mitigate some disadvantages of the serial approach, increasingly are being used in chemical dependency treatment settings, where it is common to have psychiatric consultations. Based on our experience, however, this approach is far less common in psychiatric treatment settings, where clinicians do not routinely treat (or sometimes even assess for) comorbid alcohol or drug disorder in anxious and depressed patients. Also, the parallel approach often requires coordinating the times, locations, and strategies of treatments systems and clinicians, which can lead to problems:

- Substance use disorder treatment expertise is not always available for patients in mental health treatment.

- Clinicians from disparate systems may not fully understand the impact of the comorbid disorder and the culture of the parallel treatment system.

- Practitioners (or patients) might see medications or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) exercises for anxiety as contradicting core tenants of the parallel treatment approach.

- It is not certain that standard treatments validated in non-comorbid patients would have the same therapeutic benefits when administered in a parallel treatment.5

Integrated treatments seek to address both comorbid disorders in a single treatment program. Our group has found, for example, that a CBT program aimed at treating comorbid anxiety could be successfully integrated with a standard alcohol disorder treatment.17

Several factors limit the use of integrated treatments, however:

- Few such programs exist.

- Treatment providers in mental health and addiction settings typically are not cross-trained.

- Personnel and other institutional supports are often lacking for integrated treatment programs.

Integrated treatment plan

Our CBT-based integrated approach to alcoholism treatment in patients with a comorbid anxiety disorder incorporates 3 components:

- psychoeducation

- cognitive restructuring

- cue exposure.

Psychoeducation. The goal of psychoeducation is to explain the biopsychosocial model of anxiety disorder, alcohol disorders, and their interactions. This information is the general platform on which the specific treatment program is established in the next phase of the treatment.

In addition to providing basic epidemiologic facts, we use simple language and graphics to emphasize the vicious cycle that can emerge between drinking and anxiety, wherein the more one uses alcohol to manage anxiety in the short run the more anxiety there is to manage in the long run.

We introduce the role of cognitions, thoughts, beliefs, and expectations in how individuals react to situations to produce anxiety and drinking urges. Finally, we teach patients a standard paced diaphragmatic breathing exercise designed to minimize hyperventilation commonly identified among individuals with anxiety disorders.

Cognitive restructuring. We teach patients about thinking patterns that contribute to initiating and maintaining anxiety and panic. We also teach patients how to recognize and restructure cognitions that promote alcohol use as a means of coping with anxiety, such as focusing on alcohol’s short-term calming effects instead of its longer-term anxiogenic effects. This phase requires clinical expertise in CBT skills; a wide range of resource materials is available to walk the patient (and clinician) through cognitive restructuring exercises (see Related Resources).

Cue exposure involves systematic therapist-guided exposure to fear-provoking situations and sensations with the goal of decoupling them from anxiety-inducing thoughts about catastrophic outcomes.

Exposures are used:

- for reality testing

- to allow patients to practice new anxiety management skills

- to increase patients’ sense that they can successfully cope in feared situations (“self-efficacy”).

We expand this approach to include alcohol-relevant cues associated with anxiety states. Exposures—imaginal and in vivo—incorporate this information to help patients decouple anxiety feelings from drinking urges and to practice alternate coping strategies.

Pilot data for integrated Tx

After 4 months of participating in an integrated CBT program, 32 alcoholism treatment patients with panic disorder were significantly less likely to meet criteria for panic disorder, compared with 17 patients who received standard chemical dependency treatment without the CBT program (M.G.K., C.D., B.F., unpublished data, 2007). Before treatment, both groups averaged approximately 2.5 panic attacks per week. At follow-up the group that received CBT averaged <0.5 panic attacks per week, whereas the control group averaged approximately 2 panic attacks per week.

Overall, there was a positive effect for CBT treatment in terms of relapse to full alcohol dependence—10% in the treatment group met this criteria vs 35% in the control group. Integrated CBT treatment was more effective in reducing relapse risk among patients who reported the strongest baseline expectations that alcohol consumption helps to control their anxiety symptoms: 0% in the treatment group relapsed to full alcohol dependence vs. 57% in the control group. For comorbid cases that had the weakest anxiety-reduction expectancies, 21% in the CBT group met the relapse criterion compared with about 20% in the control group.

In summary, an integrated CBT program for comorbid panic disorder appears to provide the greatest added value to standard alcoholism treatment among patients who expect alcohol to relieve their anxiety symptoms.

Treatment in a psychiatric setting

Our group is in the process of generating a database upon which to make empirically based treatment recommendations. Until then, we can offer treatment recommendations based upon experience and the limited data available.

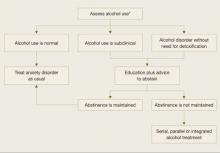

When planning psychiatric treatment for a patient with an anxiety disorder, start by assessing the patient’s alcohol use (Figure 2). The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) offers assessment tools (see Related Resources) to help you judge whether a patient’s alcohol use exceeds recommended limits (for example, 7 drinks per week for women and 14 per week for men).

Teach individuals whose drinking is excessive and/or regular (especially deliberate drinking aimed at coping with anxiety) about the risk associated with alcohol use and potential interference of alcohol/drugs with successful anxiety treatment. Suggest that patients reduce their drinking, and solicit their input into what would be a reasonable goal, such as those suggested in the NIAAA clinical guidelines (see Related Resources). Also advise patients to refrain from drinking/using before or during anxiety exposures so they can obtain the maximum benefits of treatment.

Individuals who are severely alcohol dependent or fail to meet their reduced drinking goals may require additional treatment. Options include:

- referral to a specialized addiction treatment setting

- pharmacotherapy with FDA-approved medications for treating alcohol dependence, such as naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram.

Figure 2

Identifying and addressing alcohol use in patients with anxiety disorder

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) offers assessment tools to help you judge whether a patient’s alcohol use exceeds recommended limits (seeRelated Resources).Related resources

- Al’Absi, M, ed. Stress and addiction: Biological and psychological mechanisms. 1st ed. New York: Elsevier-Academic Press; 2007.

- Beck AT, Wright FD, Newman CF, Liese BS. Cognitive therapy of substance abuse. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcoholism screening tools. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh28-2/78-79.htm.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide. 2005 ed. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. NIH Publication No. 07-3769. http://pubs.niaaa. nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/ clinicians_guide.htm.

- Padesky CA, Greenberger D. Mind over mood. New York: Guilford Press; 1995.

Drug brand names

- Acamprosate • Campral

- Disulfiram • Antabuse

- Naltrexone • Depade, ReVia

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eric Maurer for his help in preparing this manuscript.

This work was supported, in part, by the following grants: NIAAA Grant R01 AA0105069 (MGK), R01 AA013379 (CLR), P50 AA010761 (CLR, SWB).

1. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in the United States: main findings from the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Bethesda, MD; National Institutes of Health; 2006. NIH Publication No. 05-5737.

2. Kushner, Sher KJ, Beitman BD. The relation between alcohol problems and the anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:685-95.

3. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Thuras P, et al. Follow-up study of anxiety disorder and alcohol dependence in comorbid alcoholism treatment patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29:1432-43.

4. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. Anxiety disorders co-occurring with alcohol or drug use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev 2000;20:149-71.

5. Randall CL, Thomas S, Thevos AK. Concurrent alcoholism and social anxiety disorder: a first step toward developing effective treatments. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25:210-20.

6. Thomas SE, Thevos AK, Randall CL. Alcoholics with and without social phobia: a comparison of substance use and psychiatric variables. J Stud Alcohol 1999;60(4):472-9.

7. Conger JJ. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Q J Stud Alcohol 1956;17:296-305.

8. Sher KG, Levenson RW. Risk for alcoholism and individual differences in the stress-response dampening effect of alcohol. J Abnorm Psychol 1982;91:350-68.

9. Carrigan MH, Randall CL. Self-medication in social phobia: a review of the alcohol literature. Addict Behav 2003;28(2):269-84.

10. Schuckit MA, Hesselbrock V. Alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders: what is the relationship? Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1723-34.

11. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:807-16.

12. Thomas SE, Randall CL, Carrigan MH. Drinking to cope in socially anxious individuals: a controlled study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003;27(12):1937-43.

13. Merikangas KR, Metha RL, Molnar BE, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatry Epidemiology. Addict Behav 1996;23(6):893-907.

14. Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Erickson DJ. Prospective analysis of the relation between DSM-III anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1990;156:723-32.

15. Book SW, Thomas SE, Randall PK, Randall CL. Paroxetine reduces social anxiety in individuals with a co-occurring alcohol use disorder. J Anxiety Disord. In press.

16. Kadden RM, Kranzler HR, Rounsaville BJ. Validity of the distinction between “substance-induced” and “independent” depression and anxiety disorders. Am J Addict 1995;4:107-17.

17. Kushner MG, Donahue C, Sletten S. Cognitive behavioral treatment of comorbid anxiety disorder in alcoholism treatment patients: presentation of a prototype program and future directions. J Mental Health 2006;15:697-708.

Men and women with anxiety disorders are at three times the general population’s risk of being alcohol-dependent (Table),1 and those who seek treatment for an anxiety disorder are at even higher risk of alcohol disorder.2,3 This comorbidity can complicate treatment attempts if either disorder remains unaddressed, leading to increased relapse risk and multiple treatment episodes.

Based on our research and clinical work in helping patients with comorbid alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders,2,4-6 this article describes:

- potential relationships between anxiety disorders and alcohol disorder

- pros and cons of 3 approaches to treating this comorbidity

- how to identify and address alcohol disorder in patients with anxiety disorders, depending on available resources.

Table

Comorbidity rates of anxiety disorders and alcohol dependence*

| Anxiety disorder | Odds ratio for having alcohol dependence | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |

| Any | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Panic disorder | 3.8 | 3.7 |

| Social phobia | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| Specific phobia | 2.8 | 2.9 |

| * Numbers indicate odds of having alcohol dependence when the anxiety disorder is present vs absent. | ||

| Source: 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), reference 1 | ||

3 comorbidity models

The most common understanding of this comorbidity (Figure 1) is that having an anxiety disorder predisposes one to develop an alcohol or substance use disorder via self-medication—using alcohol or drugs to modulate anxiety and negative affect.7-9 However, substance use disorder experts have argued that the social, occupational, and physiologic effects of substance use can generate new anxiety symptoms in vulnerable individuals.10 In other words, physiologic and/or environmental disruptions from chronic alcohol or substance use could promote conditions and circumstances in which anxiety symptoms are more likely to emerge or worsen.

Although DSM-IV-TR does not delve into the causes of mental disorders, it states that substance use can cause or “induce” an anxiety syndrome with symptoms that resemble or are identical to those of the various anxiety syndromes that are not related to substance disorder (Box).11,12

Alternatively, the idea that a third factor can serve as a common cause for both conditions fits with the view that substance use disorder and anxiety disorder can be phenotypic expressions of a common underlying genetic/physiologic liability.13

Finally, these models are not mutually exclusive. Anxiety symptoms or substance use could cause or aggravate the other.

Figure 1

Hypothetical models of comorbidity

Which comes first?

Anxiety disorder typically begins before a substance use disorder in comorbid cases, although some studies have reported the opposite pattern or roughly simultaneous onset of both disorders.2

Using a prospective method in college students, we found that the risk of developing alcohol dependence for the first time as a junior or senior more than tripled among students who had an anxiety diagnosis as a freshman.14 We also found, however, that students who were alcohol dependent as freshman were 4 times more likely than other freshman to develop an anxiety disorder for the first time within the next 6 years.

In short, having either an anxiety or alcohol disorder earlier in life appears to increase the probability of developing the other later. This finding supports the idea that the types of associations that link pathologic anxiety and substance use vary among individuals and, perhaps, within individuals over time.

3 treatment approaches

Treating 1 of the comorbid conditions—anxiety or alcohol disorder—does not tend to resolve the other.3,15 This suggests that therapies aimed at treating a single disorder are not satisfactory for treating comorbid cases. Possible multi-focused approaches include:

- serial (or sequential) approach—treating comorbid disorders one at a time

- parallel approach—providing simultaneous but separate treatments for each comorbidity

- integrated approach—providing one treatment that focuses on both comorbid disorders, especially as they interact with one another.

Each has strengths and weaknesses, and the approach you choose for your patient may depend on clinical circumstances and available resources.

Serial treatment has the structure to empirically evaluate whether the initially untreated comorbid condition is resolved by treating the other condition. For example, you could treat an anxiety disorder as usual and refer the patient for alcohol disorder treatment only if drinking remains an active problem following anxiety treatment. This approach also allows you to use well-established treatment systems, programs, and specialists as usual.

One disadvantage to the serial approach, however, is that the initially untreated comorbid disorder could undermine the resolution of the treated disorder. We found, for example, that treating either the anxiety or the alcohol disorder alone fails to resolve the comorbid condition and might leave a patient vulnerable to relapse before serial treatment can be completed.3,15

When implementing a serial treatment, it is not always clear which disorder to treat first. Distinguishing comorbid disorders as “primary” or “secondary” often is done inconsistently and imprecisely, so treatment decisions based on these terms can be erroneous. Using the order of disorder onset also is an unreliable guide to which disorder is in priority need of treatment.7,16

Based on our experience and research, where and why the comorbid patient presents for treatment should be factored heavily in these treatment decisions. For example, individuals seeking anxiety treatment who have a comorbid alcohol use disorder typically possess little insight into their drinking problem and a frank resistance to clinician-driven attempts to modify their drinking behavior. We would expect a similar reaction from patients presenting for alcohol disorder treatment who are told they must first obtain psychiatric treatment for anxiety symptoms. The serial approach often necessitates that patients be treated initially for the problem for which they present and then referred afterward for the comorbid condition as needed.

In an open-label pilot treatment study of 5 subjects with social anxiety disorder and a co-occurring alcohol use disorder (C.L.R., S.W.B., unpublished data, 2007), we first treated the anxiety disorder with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine, up to 60 mg/d. After 6 weeks, we addressed the comorbid alcohol problem using a brief alcohol intervention. This approach met with little or no resistance to reduce drinking—all 5 subjects successfully decreased their alcohol consumption, and none dropped out of treatment. A controlled follow-up trial is planned to provide empiric support for serial treatment of anxiety and alcohol use disorders in mental health treatment settings.

DSM-IV-TR describes an anxiety disorder as independent from a coexisting substance use disorder only if the anxiety disorder:

- began distinctly before the substance use disorder

- or persisted during periods of extended abstinence (>1 month) from substance use/abuse.

Otherwise, substance abuse is presumed to have induced the anxiety disorder. This perspective implies that no specific treatment beyond drug/alcohol abstinence is required to resolve a substance-induced anxiety disorder.

In a large community-based sample, Grant et al11 found that <0.5% of individuals with comorbid anxiety and substance abuse met the strictly defined DSM-IV-TR criteria for a substance-induced anxiety disorder. Cases in which a comorbid anxiety disorder resolved during periods of substance abuse abstinence were especially rare. This observation suggests that substance-induced anxiety syndrome as defined by DSM-IV-TR is very rare in clinical practice.

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria do not recognize an “anxiety-induced substance use disorder,” in which pathologic anxiety might induce a substance use disorder. Conceptually, however, this idea is as reasonable as substance-induced anxiety disorder and fits within the self-medication model.12

Parallel treatments, which can mitigate some disadvantages of the serial approach, increasingly are being used in chemical dependency treatment settings, where it is common to have psychiatric consultations. Based on our experience, however, this approach is far less common in psychiatric treatment settings, where clinicians do not routinely treat (or sometimes even assess for) comorbid alcohol or drug disorder in anxious and depressed patients. Also, the parallel approach often requires coordinating the times, locations, and strategies of treatments systems and clinicians, which can lead to problems:

- Substance use disorder treatment expertise is not always available for patients in mental health treatment.

- Clinicians from disparate systems may not fully understand the impact of the comorbid disorder and the culture of the parallel treatment system.

- Practitioners (or patients) might see medications or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) exercises for anxiety as contradicting core tenants of the parallel treatment approach.

- It is not certain that standard treatments validated in non-comorbid patients would have the same therapeutic benefits when administered in a parallel treatment.5

Integrated treatments seek to address both comorbid disorders in a single treatment program. Our group has found, for example, that a CBT program aimed at treating comorbid anxiety could be successfully integrated with a standard alcohol disorder treatment.17

Several factors limit the use of integrated treatments, however:

- Few such programs exist.

- Treatment providers in mental health and addiction settings typically are not cross-trained.

- Personnel and other institutional supports are often lacking for integrated treatment programs.

Integrated treatment plan

Our CBT-based integrated approach to alcoholism treatment in patients with a comorbid anxiety disorder incorporates 3 components:

- psychoeducation

- cognitive restructuring

- cue exposure.

Psychoeducation. The goal of psychoeducation is to explain the biopsychosocial model of anxiety disorder, alcohol disorders, and their interactions. This information is the general platform on which the specific treatment program is established in the next phase of the treatment.

In addition to providing basic epidemiologic facts, we use simple language and graphics to emphasize the vicious cycle that can emerge between drinking and anxiety, wherein the more one uses alcohol to manage anxiety in the short run the more anxiety there is to manage in the long run.

We introduce the role of cognitions, thoughts, beliefs, and expectations in how individuals react to situations to produce anxiety and drinking urges. Finally, we teach patients a standard paced diaphragmatic breathing exercise designed to minimize hyperventilation commonly identified among individuals with anxiety disorders.

Cognitive restructuring. We teach patients about thinking patterns that contribute to initiating and maintaining anxiety and panic. We also teach patients how to recognize and restructure cognitions that promote alcohol use as a means of coping with anxiety, such as focusing on alcohol’s short-term calming effects instead of its longer-term anxiogenic effects. This phase requires clinical expertise in CBT skills; a wide range of resource materials is available to walk the patient (and clinician) through cognitive restructuring exercises (see Related Resources).

Cue exposure involves systematic therapist-guided exposure to fear-provoking situations and sensations with the goal of decoupling them from anxiety-inducing thoughts about catastrophic outcomes.

Exposures are used:

- for reality testing

- to allow patients to practice new anxiety management skills

- to increase patients’ sense that they can successfully cope in feared situations (“self-efficacy”).

We expand this approach to include alcohol-relevant cues associated with anxiety states. Exposures—imaginal and in vivo—incorporate this information to help patients decouple anxiety feelings from drinking urges and to practice alternate coping strategies.

Pilot data for integrated Tx

After 4 months of participating in an integrated CBT program, 32 alcoholism treatment patients with panic disorder were significantly less likely to meet criteria for panic disorder, compared with 17 patients who received standard chemical dependency treatment without the CBT program (M.G.K., C.D., B.F., unpublished data, 2007). Before treatment, both groups averaged approximately 2.5 panic attacks per week. At follow-up the group that received CBT averaged <0.5 panic attacks per week, whereas the control group averaged approximately 2 panic attacks per week.

Overall, there was a positive effect for CBT treatment in terms of relapse to full alcohol dependence—10% in the treatment group met this criteria vs 35% in the control group. Integrated CBT treatment was more effective in reducing relapse risk among patients who reported the strongest baseline expectations that alcohol consumption helps to control their anxiety symptoms: 0% in the treatment group relapsed to full alcohol dependence vs. 57% in the control group. For comorbid cases that had the weakest anxiety-reduction expectancies, 21% in the CBT group met the relapse criterion compared with about 20% in the control group.

In summary, an integrated CBT program for comorbid panic disorder appears to provide the greatest added value to standard alcoholism treatment among patients who expect alcohol to relieve their anxiety symptoms.

Treatment in a psychiatric setting

Our group is in the process of generating a database upon which to make empirically based treatment recommendations. Until then, we can offer treatment recommendations based upon experience and the limited data available.

When planning psychiatric treatment for a patient with an anxiety disorder, start by assessing the patient’s alcohol use (Figure 2). The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) offers assessment tools (see Related Resources) to help you judge whether a patient’s alcohol use exceeds recommended limits (for example, 7 drinks per week for women and 14 per week for men).

Teach individuals whose drinking is excessive and/or regular (especially deliberate drinking aimed at coping with anxiety) about the risk associated with alcohol use and potential interference of alcohol/drugs with successful anxiety treatment. Suggest that patients reduce their drinking, and solicit their input into what would be a reasonable goal, such as those suggested in the NIAAA clinical guidelines (see Related Resources). Also advise patients to refrain from drinking/using before or during anxiety exposures so they can obtain the maximum benefits of treatment.

Individuals who are severely alcohol dependent or fail to meet their reduced drinking goals may require additional treatment. Options include:

- referral to a specialized addiction treatment setting

- pharmacotherapy with FDA-approved medications for treating alcohol dependence, such as naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram.

Figure 2

Identifying and addressing alcohol use in patients with anxiety disorder

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) offers assessment tools to help you judge whether a patient’s alcohol use exceeds recommended limits (seeRelated Resources).Related resources

- Al’Absi, M, ed. Stress and addiction: Biological and psychological mechanisms. 1st ed. New York: Elsevier-Academic Press; 2007.

- Beck AT, Wright FD, Newman CF, Liese BS. Cognitive therapy of substance abuse. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcoholism screening tools. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh28-2/78-79.htm.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide. 2005 ed. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. NIH Publication No. 07-3769. http://pubs.niaaa. nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/ clinicians_guide.htm.

- Padesky CA, Greenberger D. Mind over mood. New York: Guilford Press; 1995.

Drug brand names

- Acamprosate • Campral

- Disulfiram • Antabuse

- Naltrexone • Depade, ReVia

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eric Maurer for his help in preparing this manuscript.

This work was supported, in part, by the following grants: NIAAA Grant R01 AA0105069 (MGK), R01 AA013379 (CLR), P50 AA010761 (CLR, SWB).

Men and women with anxiety disorders are at three times the general population’s risk of being alcohol-dependent (Table),1 and those who seek treatment for an anxiety disorder are at even higher risk of alcohol disorder.2,3 This comorbidity can complicate treatment attempts if either disorder remains unaddressed, leading to increased relapse risk and multiple treatment episodes.

Based on our research and clinical work in helping patients with comorbid alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders,2,4-6 this article describes:

- potential relationships between anxiety disorders and alcohol disorder

- pros and cons of 3 approaches to treating this comorbidity

- how to identify and address alcohol disorder in patients with anxiety disorders, depending on available resources.

Table

Comorbidity rates of anxiety disorders and alcohol dependence*

| Anxiety disorder | Odds ratio for having alcohol dependence | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |

| Any | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Panic disorder | 3.8 | 3.7 |

| Social phobia | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| Specific phobia | 2.8 | 2.9 |

| * Numbers indicate odds of having alcohol dependence when the anxiety disorder is present vs absent. | ||

| Source: 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), reference 1 | ||

3 comorbidity models

The most common understanding of this comorbidity (Figure 1) is that having an anxiety disorder predisposes one to develop an alcohol or substance use disorder via self-medication—using alcohol or drugs to modulate anxiety and negative affect.7-9 However, substance use disorder experts have argued that the social, occupational, and physiologic effects of substance use can generate new anxiety symptoms in vulnerable individuals.10 In other words, physiologic and/or environmental disruptions from chronic alcohol or substance use could promote conditions and circumstances in which anxiety symptoms are more likely to emerge or worsen.

Although DSM-IV-TR does not delve into the causes of mental disorders, it states that substance use can cause or “induce” an anxiety syndrome with symptoms that resemble or are identical to those of the various anxiety syndromes that are not related to substance disorder (Box).11,12

Alternatively, the idea that a third factor can serve as a common cause for both conditions fits with the view that substance use disorder and anxiety disorder can be phenotypic expressions of a common underlying genetic/physiologic liability.13

Finally, these models are not mutually exclusive. Anxiety symptoms or substance use could cause or aggravate the other.

Figure 1

Hypothetical models of comorbidity

Which comes first?

Anxiety disorder typically begins before a substance use disorder in comorbid cases, although some studies have reported the opposite pattern or roughly simultaneous onset of both disorders.2

Using a prospective method in college students, we found that the risk of developing alcohol dependence for the first time as a junior or senior more than tripled among students who had an anxiety diagnosis as a freshman.14 We also found, however, that students who were alcohol dependent as freshman were 4 times more likely than other freshman to develop an anxiety disorder for the first time within the next 6 years.

In short, having either an anxiety or alcohol disorder earlier in life appears to increase the probability of developing the other later. This finding supports the idea that the types of associations that link pathologic anxiety and substance use vary among individuals and, perhaps, within individuals over time.

3 treatment approaches

Treating 1 of the comorbid conditions—anxiety or alcohol disorder—does not tend to resolve the other.3,15 This suggests that therapies aimed at treating a single disorder are not satisfactory for treating comorbid cases. Possible multi-focused approaches include:

- serial (or sequential) approach—treating comorbid disorders one at a time

- parallel approach—providing simultaneous but separate treatments for each comorbidity

- integrated approach—providing one treatment that focuses on both comorbid disorders, especially as they interact with one another.

Each has strengths and weaknesses, and the approach you choose for your patient may depend on clinical circumstances and available resources.

Serial treatment has the structure to empirically evaluate whether the initially untreated comorbid condition is resolved by treating the other condition. For example, you could treat an anxiety disorder as usual and refer the patient for alcohol disorder treatment only if drinking remains an active problem following anxiety treatment. This approach also allows you to use well-established treatment systems, programs, and specialists as usual.

One disadvantage to the serial approach, however, is that the initially untreated comorbid disorder could undermine the resolution of the treated disorder. We found, for example, that treating either the anxiety or the alcohol disorder alone fails to resolve the comorbid condition and might leave a patient vulnerable to relapse before serial treatment can be completed.3,15

When implementing a serial treatment, it is not always clear which disorder to treat first. Distinguishing comorbid disorders as “primary” or “secondary” often is done inconsistently and imprecisely, so treatment decisions based on these terms can be erroneous. Using the order of disorder onset also is an unreliable guide to which disorder is in priority need of treatment.7,16

Based on our experience and research, where and why the comorbid patient presents for treatment should be factored heavily in these treatment decisions. For example, individuals seeking anxiety treatment who have a comorbid alcohol use disorder typically possess little insight into their drinking problem and a frank resistance to clinician-driven attempts to modify their drinking behavior. We would expect a similar reaction from patients presenting for alcohol disorder treatment who are told they must first obtain psychiatric treatment for anxiety symptoms. The serial approach often necessitates that patients be treated initially for the problem for which they present and then referred afterward for the comorbid condition as needed.

In an open-label pilot treatment study of 5 subjects with social anxiety disorder and a co-occurring alcohol use disorder (C.L.R., S.W.B., unpublished data, 2007), we first treated the anxiety disorder with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine, up to 60 mg/d. After 6 weeks, we addressed the comorbid alcohol problem using a brief alcohol intervention. This approach met with little or no resistance to reduce drinking—all 5 subjects successfully decreased their alcohol consumption, and none dropped out of treatment. A controlled follow-up trial is planned to provide empiric support for serial treatment of anxiety and alcohol use disorders in mental health treatment settings.

DSM-IV-TR describes an anxiety disorder as independent from a coexisting substance use disorder only if the anxiety disorder:

- began distinctly before the substance use disorder

- or persisted during periods of extended abstinence (>1 month) from substance use/abuse.

Otherwise, substance abuse is presumed to have induced the anxiety disorder. This perspective implies that no specific treatment beyond drug/alcohol abstinence is required to resolve a substance-induced anxiety disorder.

In a large community-based sample, Grant et al11 found that <0.5% of individuals with comorbid anxiety and substance abuse met the strictly defined DSM-IV-TR criteria for a substance-induced anxiety disorder. Cases in which a comorbid anxiety disorder resolved during periods of substance abuse abstinence were especially rare. This observation suggests that substance-induced anxiety syndrome as defined by DSM-IV-TR is very rare in clinical practice.

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria do not recognize an “anxiety-induced substance use disorder,” in which pathologic anxiety might induce a substance use disorder. Conceptually, however, this idea is as reasonable as substance-induced anxiety disorder and fits within the self-medication model.12

Parallel treatments, which can mitigate some disadvantages of the serial approach, increasingly are being used in chemical dependency treatment settings, where it is common to have psychiatric consultations. Based on our experience, however, this approach is far less common in psychiatric treatment settings, where clinicians do not routinely treat (or sometimes even assess for) comorbid alcohol or drug disorder in anxious and depressed patients. Also, the parallel approach often requires coordinating the times, locations, and strategies of treatments systems and clinicians, which can lead to problems:

- Substance use disorder treatment expertise is not always available for patients in mental health treatment.

- Clinicians from disparate systems may not fully understand the impact of the comorbid disorder and the culture of the parallel treatment system.

- Practitioners (or patients) might see medications or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) exercises for anxiety as contradicting core tenants of the parallel treatment approach.

- It is not certain that standard treatments validated in non-comorbid patients would have the same therapeutic benefits when administered in a parallel treatment.5

Integrated treatments seek to address both comorbid disorders in a single treatment program. Our group has found, for example, that a CBT program aimed at treating comorbid anxiety could be successfully integrated with a standard alcohol disorder treatment.17

Several factors limit the use of integrated treatments, however:

- Few such programs exist.

- Treatment providers in mental health and addiction settings typically are not cross-trained.

- Personnel and other institutional supports are often lacking for integrated treatment programs.

Integrated treatment plan

Our CBT-based integrated approach to alcoholism treatment in patients with a comorbid anxiety disorder incorporates 3 components:

- psychoeducation

- cognitive restructuring

- cue exposure.

Psychoeducation. The goal of psychoeducation is to explain the biopsychosocial model of anxiety disorder, alcohol disorders, and their interactions. This information is the general platform on which the specific treatment program is established in the next phase of the treatment.

In addition to providing basic epidemiologic facts, we use simple language and graphics to emphasize the vicious cycle that can emerge between drinking and anxiety, wherein the more one uses alcohol to manage anxiety in the short run the more anxiety there is to manage in the long run.

We introduce the role of cognitions, thoughts, beliefs, and expectations in how individuals react to situations to produce anxiety and drinking urges. Finally, we teach patients a standard paced diaphragmatic breathing exercise designed to minimize hyperventilation commonly identified among individuals with anxiety disorders.

Cognitive restructuring. We teach patients about thinking patterns that contribute to initiating and maintaining anxiety and panic. We also teach patients how to recognize and restructure cognitions that promote alcohol use as a means of coping with anxiety, such as focusing on alcohol’s short-term calming effects instead of its longer-term anxiogenic effects. This phase requires clinical expertise in CBT skills; a wide range of resource materials is available to walk the patient (and clinician) through cognitive restructuring exercises (see Related Resources).

Cue exposure involves systematic therapist-guided exposure to fear-provoking situations and sensations with the goal of decoupling them from anxiety-inducing thoughts about catastrophic outcomes.

Exposures are used:

- for reality testing

- to allow patients to practice new anxiety management skills

- to increase patients’ sense that they can successfully cope in feared situations (“self-efficacy”).

We expand this approach to include alcohol-relevant cues associated with anxiety states. Exposures—imaginal and in vivo—incorporate this information to help patients decouple anxiety feelings from drinking urges and to practice alternate coping strategies.

Pilot data for integrated Tx

After 4 months of participating in an integrated CBT program, 32 alcoholism treatment patients with panic disorder were significantly less likely to meet criteria for panic disorder, compared with 17 patients who received standard chemical dependency treatment without the CBT program (M.G.K., C.D., B.F., unpublished data, 2007). Before treatment, both groups averaged approximately 2.5 panic attacks per week. At follow-up the group that received CBT averaged <0.5 panic attacks per week, whereas the control group averaged approximately 2 panic attacks per week.

Overall, there was a positive effect for CBT treatment in terms of relapse to full alcohol dependence—10% in the treatment group met this criteria vs 35% in the control group. Integrated CBT treatment was more effective in reducing relapse risk among patients who reported the strongest baseline expectations that alcohol consumption helps to control their anxiety symptoms: 0% in the treatment group relapsed to full alcohol dependence vs. 57% in the control group. For comorbid cases that had the weakest anxiety-reduction expectancies, 21% in the CBT group met the relapse criterion compared with about 20% in the control group.

In summary, an integrated CBT program for comorbid panic disorder appears to provide the greatest added value to standard alcoholism treatment among patients who expect alcohol to relieve their anxiety symptoms.

Treatment in a psychiatric setting

Our group is in the process of generating a database upon which to make empirically based treatment recommendations. Until then, we can offer treatment recommendations based upon experience and the limited data available.

When planning psychiatric treatment for a patient with an anxiety disorder, start by assessing the patient’s alcohol use (Figure 2). The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) offers assessment tools (see Related Resources) to help you judge whether a patient’s alcohol use exceeds recommended limits (for example, 7 drinks per week for women and 14 per week for men).

Teach individuals whose drinking is excessive and/or regular (especially deliberate drinking aimed at coping with anxiety) about the risk associated with alcohol use and potential interference of alcohol/drugs with successful anxiety treatment. Suggest that patients reduce their drinking, and solicit their input into what would be a reasonable goal, such as those suggested in the NIAAA clinical guidelines (see Related Resources). Also advise patients to refrain from drinking/using before or during anxiety exposures so they can obtain the maximum benefits of treatment.

Individuals who are severely alcohol dependent or fail to meet their reduced drinking goals may require additional treatment. Options include:

- referral to a specialized addiction treatment setting

- pharmacotherapy with FDA-approved medications for treating alcohol dependence, such as naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram.

Figure 2

Identifying and addressing alcohol use in patients with anxiety disorder

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) offers assessment tools to help you judge whether a patient’s alcohol use exceeds recommended limits (seeRelated Resources).Related resources

- Al’Absi, M, ed. Stress and addiction: Biological and psychological mechanisms. 1st ed. New York: Elsevier-Academic Press; 2007.

- Beck AT, Wright FD, Newman CF, Liese BS. Cognitive therapy of substance abuse. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcoholism screening tools. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh28-2/78-79.htm.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide. 2005 ed. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. NIH Publication No. 07-3769. http://pubs.niaaa. nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/ clinicians_guide.htm.

- Padesky CA, Greenberger D. Mind over mood. New York: Guilford Press; 1995.

Drug brand names

- Acamprosate • Campral

- Disulfiram • Antabuse

- Naltrexone • Depade, ReVia

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eric Maurer for his help in preparing this manuscript.

This work was supported, in part, by the following grants: NIAAA Grant R01 AA0105069 (MGK), R01 AA013379 (CLR), P50 AA010761 (CLR, SWB).

1. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in the United States: main findings from the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Bethesda, MD; National Institutes of Health; 2006. NIH Publication No. 05-5737.

2. Kushner, Sher KJ, Beitman BD. The relation between alcohol problems and the anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:685-95.

3. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Thuras P, et al. Follow-up study of anxiety disorder and alcohol dependence in comorbid alcoholism treatment patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29:1432-43.

4. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. Anxiety disorders co-occurring with alcohol or drug use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev 2000;20:149-71.

5. Randall CL, Thomas S, Thevos AK. Concurrent alcoholism and social anxiety disorder: a first step toward developing effective treatments. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25:210-20.

6. Thomas SE, Thevos AK, Randall CL. Alcoholics with and without social phobia: a comparison of substance use and psychiatric variables. J Stud Alcohol 1999;60(4):472-9.

7. Conger JJ. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Q J Stud Alcohol 1956;17:296-305.

8. Sher KG, Levenson RW. Risk for alcoholism and individual differences in the stress-response dampening effect of alcohol. J Abnorm Psychol 1982;91:350-68.

9. Carrigan MH, Randall CL. Self-medication in social phobia: a review of the alcohol literature. Addict Behav 2003;28(2):269-84.

10. Schuckit MA, Hesselbrock V. Alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders: what is the relationship? Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1723-34.

11. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:807-16.

12. Thomas SE, Randall CL, Carrigan MH. Drinking to cope in socially anxious individuals: a controlled study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003;27(12):1937-43.

13. Merikangas KR, Metha RL, Molnar BE, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatry Epidemiology. Addict Behav 1996;23(6):893-907.

14. Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Erickson DJ. Prospective analysis of the relation between DSM-III anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1990;156:723-32.

15. Book SW, Thomas SE, Randall PK, Randall CL. Paroxetine reduces social anxiety in individuals with a co-occurring alcohol use disorder. J Anxiety Disord. In press.

16. Kadden RM, Kranzler HR, Rounsaville BJ. Validity of the distinction between “substance-induced” and “independent” depression and anxiety disorders. Am J Addict 1995;4:107-17.

17. Kushner MG, Donahue C, Sletten S. Cognitive behavioral treatment of comorbid anxiety disorder in alcoholism treatment patients: presentation of a prototype program and future directions. J Mental Health 2006;15:697-708.

1. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in the United States: main findings from the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Bethesda, MD; National Institutes of Health; 2006. NIH Publication No. 05-5737.

2. Kushner, Sher KJ, Beitman BD. The relation between alcohol problems and the anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:685-95.

3. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Thuras P, et al. Follow-up study of anxiety disorder and alcohol dependence in comorbid alcoholism treatment patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29:1432-43.

4. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. Anxiety disorders co-occurring with alcohol or drug use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev 2000;20:149-71.

5. Randall CL, Thomas S, Thevos AK. Concurrent alcoholism and social anxiety disorder: a first step toward developing effective treatments. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25:210-20.

6. Thomas SE, Thevos AK, Randall CL. Alcoholics with and without social phobia: a comparison of substance use and psychiatric variables. J Stud Alcohol 1999;60(4):472-9.

7. Conger JJ. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Q J Stud Alcohol 1956;17:296-305.

8. Sher KG, Levenson RW. Risk for alcoholism and individual differences in the stress-response dampening effect of alcohol. J Abnorm Psychol 1982;91:350-68.

9. Carrigan MH, Randall CL. Self-medication in social phobia: a review of the alcohol literature. Addict Behav 2003;28(2):269-84.

10. Schuckit MA, Hesselbrock V. Alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders: what is the relationship? Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1723-34.

11. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:807-16.

12. Thomas SE, Randall CL, Carrigan MH. Drinking to cope in socially anxious individuals: a controlled study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003;27(12):1937-43.

13. Merikangas KR, Metha RL, Molnar BE, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatry Epidemiology. Addict Behav 1996;23(6):893-907.

14. Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Erickson DJ. Prospective analysis of the relation between DSM-III anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1990;156:723-32.

15. Book SW, Thomas SE, Randall PK, Randall CL. Paroxetine reduces social anxiety in individuals with a co-occurring alcohol use disorder. J Anxiety Disord. In press.

16. Kadden RM, Kranzler HR, Rounsaville BJ. Validity of the distinction between “substance-induced” and “independent” depression and anxiety disorders. Am J Addict 1995;4:107-17.

17. Kushner MG, Donahue C, Sletten S. Cognitive behavioral treatment of comorbid anxiety disorder in alcoholism treatment patients: presentation of a prototype program and future directions. J Mental Health 2006;15:697-708.