User login

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Track Helps Hospitalists Achieve ABIM Recertification

This is the year I complete my second recertification for the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). Prior to 1990, the ABIM issued certificates that were good for life. Beginning in 1990 and through 2013, all certificates were issued for a 10-year duration. All those prior lifetime certificates were honored, so those holding them were deemed “grandfathered” and have not had to recertify. The rest of us are now on the recertification pathway, renewing every 10 years. Although the date has been set at 10 years, the recertification process has become more regimented since January 2014, when the ABIM moved to a continuous program requiring evidence of new learning and maintenance of quality in your practice every two years.

This ratcheting up of requirements and adding increased increments of progress hasn’t come without controversy. Last year a petition was started and signed by 19,000 physicians protesting the changes and arguing the ABIM should go back to the methodology of taking a test every 10 years. Even this was a moderate position; many were clamoring for the abolition of maintenance of certification (MOC) all together.

I represented the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) in July 2014 at a summit in Philadelphia called by the ABIM Foundation. Each of the medical subspecialties was given an opportunity to speak to the ABIM leadership and the audience of fellow representatives about the impact of MOC. As members of a relatively youthful field, hospitalists are less focused on how the “grandfathers” are being treated and more concerned about the confusing process and lack of opportunity to incorporate our daily hospitalist-focused work effort easily into the process.

As a result of that petition, many letters written to the board, and the outspoken representatives at the ABIM summit, the ABIM has responded with a plan to make elements of the process more friendly and open, as well as one to further plan and adapt.

Clearly, this is a process in evolution. Hospitalists are committed to lifelong learning. I think we can expect that with more transparency in all aspects of our lives, personal and professional, our patients, our hospitals, and payers…will all be expecting to see just exactly how committed we are to lifelong learning and self-improvement.

It’s our turn…

In 2009, some bold steps were taken with the announcement of the new Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) that, hopefully, will impact hospitalists for many years to come. SHM’s partnership with the ABIM began with work five years prior, creating a focused declaration of hospital medicine competence. Initially, this was set up as a pilot project to be evaluated for success along the way, to see if the concept would become permanent. The work was announced, and the inaugural class of 175 physicians entered the process. Since that time, 555 physicians have earned the FPHM certificate. What’s even more impressive is that we have seen a surge recently in the number of entrants. There are now 3,300 hospitalists enrolled in the pathway.

While this growth is great, we estimate that there are 44,000 hospitalists in the U.S. We know that many are newer hospitalists and not yet up for recertification. Our goal is to get every hospitalist entering the pathway when it is his or her time, just like I’m doing now. It is my time!

As we steadily progress in distinguishing and defining our field, we need as many hospitalists as possible to raise their hands and say that they proudly practice hospital medicine and have taken the steps to learn the special knowledge and gain the special skills needed to succeed in the hospital. The ABIM certification program is still in the pilot phase. One of the key markers of success to determine if it will be continued is the number of participants. I am writing this column as another way to encourage us all to stand up and be counted.

Practical Tips

So, we know things have changed, and we know things will be changing more, but what about now? What do we need to do to navigate the process to gain our FPHM certificate today?

1. Enter the process: You can’t win if you don’t play. Entering FPHM is easier than ever. The requirement for current active ACLS has been removed. Now it is a declaration that you see 1,000 patients a year or that you had 3,000 encounters in the last three years and pay the supplemental fee.

2. Earn 100 “points”: You have five years, with a mix of Part II and Part IV activities at least every two years, and the secure exam. You must have the patient voice and patient safety module credit as part of this every five years block.

2a. Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment (Part II): Show what you know or learn on an ongoing basis. You can do these at home, work, or with a buddy, or, even better, sign up for a group learning session, usually offered as a pre-course at society meetings. HM15 will be offering a pre-course that will offer Part II credit. SHM’s Hospital QI and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module is available at www.shmlearningportal.org.

2b. Practice Improvement (Part IV): Show that you are trying to improve your practice. Again, the ABIM website lists many possibilities for improvement activities that count and has a practice improvement module (PIM) selector tool (select “hospital medicine” and “inpatient”). Here are some of my favorite PIMs.

Team PIM. Complete a self-assessment of your team skills, get 10 members of your hospital multidisciplinary team to fill out an evaluation on you, and then review with a trusted colleague. This PIM also satisfies both patient voice and patient safety requirements (10 points).

SHM Project BOOST or SHM’s Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation Program. Do either of these at your hospital to earn 20 points.

Clinical Supervisor PIM. For those of you who work with residents or students. Observe 10 visits by learners, then follow up with a chart look-back, feedback to the learner, and a plan for improving learning (20 points).

3. Take a test! The secure exam is given every 10 years and counts for 20 points. What is great about this FPHM test is that it is focused on all the stuff you do every day in your job. It’s a hospitalist test, not an outpatient clinic doctor test. It focuses on inpatient clinical medicine and palliative care, plus patient safety and quality. You can use the current study materials (MedStudy, MKSAP [Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program], and the like); just skip the purely ambulatory material. Focused study materials will be available in the next year. Look for the HM15 exam preparation guide, which will direct you to HM15 sessions that cross over with the ABIM/ABFM [American Board of Family Medicine] Hospital Medicine exam.

If you would like other tools for studying for the consultative co-management and quality and patient safety sections of the exam, check out SHM Learning Portal.

Final Thoughts

It’s complicated, right? But each time I look at it or read one of these articles, it gets a bit simpler. The overall process for internal medicine certification now mirrors this one, with very few differences. Remember, the ABFM process is identical for hospitalists trained in family medicine. Hopefully, this column will help you get off the fence and come down on the side of representing what you do every day at work in the hospital.

Be proud, take the more pertinent path, be a hospitalist! Twenty points.

This is the year I complete my second recertification for the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). Prior to 1990, the ABIM issued certificates that were good for life. Beginning in 1990 and through 2013, all certificates were issued for a 10-year duration. All those prior lifetime certificates were honored, so those holding them were deemed “grandfathered” and have not had to recertify. The rest of us are now on the recertification pathway, renewing every 10 years. Although the date has been set at 10 years, the recertification process has become more regimented since January 2014, when the ABIM moved to a continuous program requiring evidence of new learning and maintenance of quality in your practice every two years.

This ratcheting up of requirements and adding increased increments of progress hasn’t come without controversy. Last year a petition was started and signed by 19,000 physicians protesting the changes and arguing the ABIM should go back to the methodology of taking a test every 10 years. Even this was a moderate position; many were clamoring for the abolition of maintenance of certification (MOC) all together.

I represented the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) in July 2014 at a summit in Philadelphia called by the ABIM Foundation. Each of the medical subspecialties was given an opportunity to speak to the ABIM leadership and the audience of fellow representatives about the impact of MOC. As members of a relatively youthful field, hospitalists are less focused on how the “grandfathers” are being treated and more concerned about the confusing process and lack of opportunity to incorporate our daily hospitalist-focused work effort easily into the process.

As a result of that petition, many letters written to the board, and the outspoken representatives at the ABIM summit, the ABIM has responded with a plan to make elements of the process more friendly and open, as well as one to further plan and adapt.

Clearly, this is a process in evolution. Hospitalists are committed to lifelong learning. I think we can expect that with more transparency in all aspects of our lives, personal and professional, our patients, our hospitals, and payers…will all be expecting to see just exactly how committed we are to lifelong learning and self-improvement.

It’s our turn…

In 2009, some bold steps were taken with the announcement of the new Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) that, hopefully, will impact hospitalists for many years to come. SHM’s partnership with the ABIM began with work five years prior, creating a focused declaration of hospital medicine competence. Initially, this was set up as a pilot project to be evaluated for success along the way, to see if the concept would become permanent. The work was announced, and the inaugural class of 175 physicians entered the process. Since that time, 555 physicians have earned the FPHM certificate. What’s even more impressive is that we have seen a surge recently in the number of entrants. There are now 3,300 hospitalists enrolled in the pathway.

While this growth is great, we estimate that there are 44,000 hospitalists in the U.S. We know that many are newer hospitalists and not yet up for recertification. Our goal is to get every hospitalist entering the pathway when it is his or her time, just like I’m doing now. It is my time!

As we steadily progress in distinguishing and defining our field, we need as many hospitalists as possible to raise their hands and say that they proudly practice hospital medicine and have taken the steps to learn the special knowledge and gain the special skills needed to succeed in the hospital. The ABIM certification program is still in the pilot phase. One of the key markers of success to determine if it will be continued is the number of participants. I am writing this column as another way to encourage us all to stand up and be counted.

Practical Tips

So, we know things have changed, and we know things will be changing more, but what about now? What do we need to do to navigate the process to gain our FPHM certificate today?

1. Enter the process: You can’t win if you don’t play. Entering FPHM is easier than ever. The requirement for current active ACLS has been removed. Now it is a declaration that you see 1,000 patients a year or that you had 3,000 encounters in the last three years and pay the supplemental fee.

2. Earn 100 “points”: You have five years, with a mix of Part II and Part IV activities at least every two years, and the secure exam. You must have the patient voice and patient safety module credit as part of this every five years block.

2a. Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment (Part II): Show what you know or learn on an ongoing basis. You can do these at home, work, or with a buddy, or, even better, sign up for a group learning session, usually offered as a pre-course at society meetings. HM15 will be offering a pre-course that will offer Part II credit. SHM’s Hospital QI and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module is available at www.shmlearningportal.org.

2b. Practice Improvement (Part IV): Show that you are trying to improve your practice. Again, the ABIM website lists many possibilities for improvement activities that count and has a practice improvement module (PIM) selector tool (select “hospital medicine” and “inpatient”). Here are some of my favorite PIMs.

Team PIM. Complete a self-assessment of your team skills, get 10 members of your hospital multidisciplinary team to fill out an evaluation on you, and then review with a trusted colleague. This PIM also satisfies both patient voice and patient safety requirements (10 points).

SHM Project BOOST or SHM’s Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation Program. Do either of these at your hospital to earn 20 points.

Clinical Supervisor PIM. For those of you who work with residents or students. Observe 10 visits by learners, then follow up with a chart look-back, feedback to the learner, and a plan for improving learning (20 points).

3. Take a test! The secure exam is given every 10 years and counts for 20 points. What is great about this FPHM test is that it is focused on all the stuff you do every day in your job. It’s a hospitalist test, not an outpatient clinic doctor test. It focuses on inpatient clinical medicine and palliative care, plus patient safety and quality. You can use the current study materials (MedStudy, MKSAP [Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program], and the like); just skip the purely ambulatory material. Focused study materials will be available in the next year. Look for the HM15 exam preparation guide, which will direct you to HM15 sessions that cross over with the ABIM/ABFM [American Board of Family Medicine] Hospital Medicine exam.

If you would like other tools for studying for the consultative co-management and quality and patient safety sections of the exam, check out SHM Learning Portal.

Final Thoughts

It’s complicated, right? But each time I look at it or read one of these articles, it gets a bit simpler. The overall process for internal medicine certification now mirrors this one, with very few differences. Remember, the ABFM process is identical for hospitalists trained in family medicine. Hopefully, this column will help you get off the fence and come down on the side of representing what you do every day at work in the hospital.

Be proud, take the more pertinent path, be a hospitalist! Twenty points.

This is the year I complete my second recertification for the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). Prior to 1990, the ABIM issued certificates that were good for life. Beginning in 1990 and through 2013, all certificates were issued for a 10-year duration. All those prior lifetime certificates were honored, so those holding them were deemed “grandfathered” and have not had to recertify. The rest of us are now on the recertification pathway, renewing every 10 years. Although the date has been set at 10 years, the recertification process has become more regimented since January 2014, when the ABIM moved to a continuous program requiring evidence of new learning and maintenance of quality in your practice every two years.

This ratcheting up of requirements and adding increased increments of progress hasn’t come without controversy. Last year a petition was started and signed by 19,000 physicians protesting the changes and arguing the ABIM should go back to the methodology of taking a test every 10 years. Even this was a moderate position; many were clamoring for the abolition of maintenance of certification (MOC) all together.

I represented the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) in July 2014 at a summit in Philadelphia called by the ABIM Foundation. Each of the medical subspecialties was given an opportunity to speak to the ABIM leadership and the audience of fellow representatives about the impact of MOC. As members of a relatively youthful field, hospitalists are less focused on how the “grandfathers” are being treated and more concerned about the confusing process and lack of opportunity to incorporate our daily hospitalist-focused work effort easily into the process.

As a result of that petition, many letters written to the board, and the outspoken representatives at the ABIM summit, the ABIM has responded with a plan to make elements of the process more friendly and open, as well as one to further plan and adapt.

Clearly, this is a process in evolution. Hospitalists are committed to lifelong learning. I think we can expect that with more transparency in all aspects of our lives, personal and professional, our patients, our hospitals, and payers…will all be expecting to see just exactly how committed we are to lifelong learning and self-improvement.

It’s our turn…

In 2009, some bold steps were taken with the announcement of the new Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) that, hopefully, will impact hospitalists for many years to come. SHM’s partnership with the ABIM began with work five years prior, creating a focused declaration of hospital medicine competence. Initially, this was set up as a pilot project to be evaluated for success along the way, to see if the concept would become permanent. The work was announced, and the inaugural class of 175 physicians entered the process. Since that time, 555 physicians have earned the FPHM certificate. What’s even more impressive is that we have seen a surge recently in the number of entrants. There are now 3,300 hospitalists enrolled in the pathway.

While this growth is great, we estimate that there are 44,000 hospitalists in the U.S. We know that many are newer hospitalists and not yet up for recertification. Our goal is to get every hospitalist entering the pathway when it is his or her time, just like I’m doing now. It is my time!

As we steadily progress in distinguishing and defining our field, we need as many hospitalists as possible to raise their hands and say that they proudly practice hospital medicine and have taken the steps to learn the special knowledge and gain the special skills needed to succeed in the hospital. The ABIM certification program is still in the pilot phase. One of the key markers of success to determine if it will be continued is the number of participants. I am writing this column as another way to encourage us all to stand up and be counted.

Practical Tips

So, we know things have changed, and we know things will be changing more, but what about now? What do we need to do to navigate the process to gain our FPHM certificate today?

1. Enter the process: You can’t win if you don’t play. Entering FPHM is easier than ever. The requirement for current active ACLS has been removed. Now it is a declaration that you see 1,000 patients a year or that you had 3,000 encounters in the last three years and pay the supplemental fee.

2. Earn 100 “points”: You have five years, with a mix of Part II and Part IV activities at least every two years, and the secure exam. You must have the patient voice and patient safety module credit as part of this every five years block.

2a. Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment (Part II): Show what you know or learn on an ongoing basis. You can do these at home, work, or with a buddy, or, even better, sign up for a group learning session, usually offered as a pre-course at society meetings. HM15 will be offering a pre-course that will offer Part II credit. SHM’s Hospital QI and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module is available at www.shmlearningportal.org.

2b. Practice Improvement (Part IV): Show that you are trying to improve your practice. Again, the ABIM website lists many possibilities for improvement activities that count and has a practice improvement module (PIM) selector tool (select “hospital medicine” and “inpatient”). Here are some of my favorite PIMs.

Team PIM. Complete a self-assessment of your team skills, get 10 members of your hospital multidisciplinary team to fill out an evaluation on you, and then review with a trusted colleague. This PIM also satisfies both patient voice and patient safety requirements (10 points).

SHM Project BOOST or SHM’s Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation Program. Do either of these at your hospital to earn 20 points.

Clinical Supervisor PIM. For those of you who work with residents or students. Observe 10 visits by learners, then follow up with a chart look-back, feedback to the learner, and a plan for improving learning (20 points).

3. Take a test! The secure exam is given every 10 years and counts for 20 points. What is great about this FPHM test is that it is focused on all the stuff you do every day in your job. It’s a hospitalist test, not an outpatient clinic doctor test. It focuses on inpatient clinical medicine and palliative care, plus patient safety and quality. You can use the current study materials (MedStudy, MKSAP [Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program], and the like); just skip the purely ambulatory material. Focused study materials will be available in the next year. Look for the HM15 exam preparation guide, which will direct you to HM15 sessions that cross over with the ABIM/ABFM [American Board of Family Medicine] Hospital Medicine exam.

If you would like other tools for studying for the consultative co-management and quality and patient safety sections of the exam, check out SHM Learning Portal.

Final Thoughts

It’s complicated, right? But each time I look at it or read one of these articles, it gets a bit simpler. The overall process for internal medicine certification now mirrors this one, with very few differences. Remember, the ABFM process is identical for hospitalists trained in family medicine. Hopefully, this column will help you get off the fence and come down on the side of representing what you do every day at work in the hospital.

Be proud, take the more pertinent path, be a hospitalist! Twenty points.

Cut Costs, Improve Quality and Patient Experience

“Now that’s a fire!”

—Eddie Murphy

This is the final column in my five-part series tracing the history of the hospitalist movement and the factors that propelled it into becoming the fastest growing medical specialty in history and the mainstay of American medicine that it has become.

In the first column, “Tinder & Spark,” economic forces of the early 1990s pushed Baby Boomer physicians into creative ways of working in the hospital; a seminal article in the most famous journal in the world then sparked a revolution. In part two, “Fuel,” Generation X physicians aligned with the values of the HM movement and joined the field in record numbers. In part three, “Oxygen,” I explained how the patient safety and quality movement propelled hospitalist growth, through both inspiration and funding, to new heights throughout the late 90s and early 2000s. And in the October 2014 issue, I continued my journey through the first 20 years of hospital medicine as a field with the fourth installment, “Heat,” a focus on the rise in importance of patient experience and the Millennial generation’s arrival in our hospitalist workforce.

That brings us to the present and back to a factor that started our rise and is becoming more important than ever, both for us as a specialty and for our success as a country.

The Affordability Crisis

We have known for a long time how expensive healthcare is. If it wasn’t for managed care trying to control costs in the 80s and 90s, hospitalists might very well not even exist. But now, it isn’t just costly. It is unaffordable for the average family.

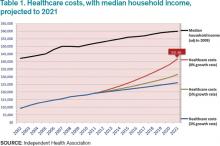

Table 1 shows projected healthcare costs and growth curves through 2021, with a median four-person household income overlaid.

In most scenarios, the two lines, income and healthcare costs, continue to get closer and closer—with healthcare costs almost $42,000 per family by 2021 in the most aggressive projection (8% growth). I am sure many of you have heard the phrase “bending the curve.” That simply means to try and bend that red line down to something approximating the blue line. It is slowing the growth, not actually decreasing the cost.

But it’s a step.

Only at that slowest healthcare growth rate projection (3%) does household income maintain pace. At the highest projection, two-thirds of family income will go toward healthcare. It simply won’t work. Affordability must be addressed.

Hospitalists are at the center of this storm. If you look at the various factors contributing to costs, we (and our keyboards) have great control and influence over inpatient, professional services, and pharmacy costs. To our credit, and to the credit of our teammates in the hospital, we actually seem to be bending the curve down toward the 5% range in inpatient care and professional services. Nevertheless, even at that level it is outpacing income growth.

In 2013, total healthcare costs for a family of four finally caught up with college costs. It is now just north of $22,000 per year for both healthcare costs and the annual cost of attending an in-state public college. Let’s not catch the private colleges as the biggest family budget buster.

The Triple Aim

So, over the course of five articles, I have talked about how we as hospitalists have faced and learned about key aspects of delivering care in a modern healthcare system. First, it was economics, then patient safety and quality, then patient experience, and now we’re back to economics as we consider patient affordability.

Wouldn’t it be great just to focus on one thing at a time? Unfortunately, life doesn’t work that way. In today’s world, hospitalists must give the best quality care while giving a great experience to their patients, all at an affordable cost. This concept of triple focus has given rise to a new term, “Triple Aim.”

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the phrase—and the idea—in 2006. It symbolizes an understanding that all three areas of quality MUST be joined together to achieve true success for our patients. As physicians and hospitalists, we have been taught to focus on health as the cornerstone of our profession. We know about cost pressures, and we now appreciate how important patient experience is. The problem has been that we tend to bounce back and forth in addressing these, silo to silo, depending on the circumstance—JCAHO [Joint Council on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations] visit, publication of CMS core measures, Press-Ganey scores.

Payers and public data sites already have moved away from just reporting health measures. Experience is nearly as prominent in the discussion now. Affordability measures and transparent pricing are on the verge, especially as we arrive in a world with value-based purchasing and cost bundling.

It is easy to focus on just the crisis of the moment. Today, that might very well be the affordability crisis, but it’s important to understand that when delivering healthcare to real live human beings, with all their complexities and vulnerabilities, we have to tune in to our most creative selves to come up with solutions that don’t just address individual areas of care but that also integrate and synergize.

Into the Future

So why this long, five-column preamble into our history, our grand social movement? Because our society and specialty, even with almost 20 years under our belts, are still in the early days. Our members know this and stay connected and coordinated, either in person, at our annual meeting, or virtually using HMX, to better face the many challenges today and those coming down the road. When SHM surveyed its members last year about why they had attended the annual meeting, the overwhelming response was to “be part of the hospital medicine movement.”

Our specialty started out as a group of one-offs and experiments and then coalesced into a social movement, and although it has changed directions and gathered new areas of focus, we are charging ahead. Much social, cultural, and medical change is to come. It’s why our members have told us they keep coming back—to share in this great and glorious social movement called hospital medicine.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

“Now that’s a fire!”

—Eddie Murphy

This is the final column in my five-part series tracing the history of the hospitalist movement and the factors that propelled it into becoming the fastest growing medical specialty in history and the mainstay of American medicine that it has become.

In the first column, “Tinder & Spark,” economic forces of the early 1990s pushed Baby Boomer physicians into creative ways of working in the hospital; a seminal article in the most famous journal in the world then sparked a revolution. In part two, “Fuel,” Generation X physicians aligned with the values of the HM movement and joined the field in record numbers. In part three, “Oxygen,” I explained how the patient safety and quality movement propelled hospitalist growth, through both inspiration and funding, to new heights throughout the late 90s and early 2000s. And in the October 2014 issue, I continued my journey through the first 20 years of hospital medicine as a field with the fourth installment, “Heat,” a focus on the rise in importance of patient experience and the Millennial generation’s arrival in our hospitalist workforce.

That brings us to the present and back to a factor that started our rise and is becoming more important than ever, both for us as a specialty and for our success as a country.

The Affordability Crisis

We have known for a long time how expensive healthcare is. If it wasn’t for managed care trying to control costs in the 80s and 90s, hospitalists might very well not even exist. But now, it isn’t just costly. It is unaffordable for the average family.

Table 1 shows projected healthcare costs and growth curves through 2021, with a median four-person household income overlaid.

In most scenarios, the two lines, income and healthcare costs, continue to get closer and closer—with healthcare costs almost $42,000 per family by 2021 in the most aggressive projection (8% growth). I am sure many of you have heard the phrase “bending the curve.” That simply means to try and bend that red line down to something approximating the blue line. It is slowing the growth, not actually decreasing the cost.

But it’s a step.

Only at that slowest healthcare growth rate projection (3%) does household income maintain pace. At the highest projection, two-thirds of family income will go toward healthcare. It simply won’t work. Affordability must be addressed.

Hospitalists are at the center of this storm. If you look at the various factors contributing to costs, we (and our keyboards) have great control and influence over inpatient, professional services, and pharmacy costs. To our credit, and to the credit of our teammates in the hospital, we actually seem to be bending the curve down toward the 5% range in inpatient care and professional services. Nevertheless, even at that level it is outpacing income growth.

In 2013, total healthcare costs for a family of four finally caught up with college costs. It is now just north of $22,000 per year for both healthcare costs and the annual cost of attending an in-state public college. Let’s not catch the private colleges as the biggest family budget buster.

The Triple Aim

So, over the course of five articles, I have talked about how we as hospitalists have faced and learned about key aspects of delivering care in a modern healthcare system. First, it was economics, then patient safety and quality, then patient experience, and now we’re back to economics as we consider patient affordability.

Wouldn’t it be great just to focus on one thing at a time? Unfortunately, life doesn’t work that way. In today’s world, hospitalists must give the best quality care while giving a great experience to their patients, all at an affordable cost. This concept of triple focus has given rise to a new term, “Triple Aim.”

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the phrase—and the idea—in 2006. It symbolizes an understanding that all three areas of quality MUST be joined together to achieve true success for our patients. As physicians and hospitalists, we have been taught to focus on health as the cornerstone of our profession. We know about cost pressures, and we now appreciate how important patient experience is. The problem has been that we tend to bounce back and forth in addressing these, silo to silo, depending on the circumstance—JCAHO [Joint Council on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations] visit, publication of CMS core measures, Press-Ganey scores.

Payers and public data sites already have moved away from just reporting health measures. Experience is nearly as prominent in the discussion now. Affordability measures and transparent pricing are on the verge, especially as we arrive in a world with value-based purchasing and cost bundling.

It is easy to focus on just the crisis of the moment. Today, that might very well be the affordability crisis, but it’s important to understand that when delivering healthcare to real live human beings, with all their complexities and vulnerabilities, we have to tune in to our most creative selves to come up with solutions that don’t just address individual areas of care but that also integrate and synergize.

Into the Future

So why this long, five-column preamble into our history, our grand social movement? Because our society and specialty, even with almost 20 years under our belts, are still in the early days. Our members know this and stay connected and coordinated, either in person, at our annual meeting, or virtually using HMX, to better face the many challenges today and those coming down the road. When SHM surveyed its members last year about why they had attended the annual meeting, the overwhelming response was to “be part of the hospital medicine movement.”

Our specialty started out as a group of one-offs and experiments and then coalesced into a social movement, and although it has changed directions and gathered new areas of focus, we are charging ahead. Much social, cultural, and medical change is to come. It’s why our members have told us they keep coming back—to share in this great and glorious social movement called hospital medicine.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

“Now that’s a fire!”

—Eddie Murphy

This is the final column in my five-part series tracing the history of the hospitalist movement and the factors that propelled it into becoming the fastest growing medical specialty in history and the mainstay of American medicine that it has become.

In the first column, “Tinder & Spark,” economic forces of the early 1990s pushed Baby Boomer physicians into creative ways of working in the hospital; a seminal article in the most famous journal in the world then sparked a revolution. In part two, “Fuel,” Generation X physicians aligned with the values of the HM movement and joined the field in record numbers. In part three, “Oxygen,” I explained how the patient safety and quality movement propelled hospitalist growth, through both inspiration and funding, to new heights throughout the late 90s and early 2000s. And in the October 2014 issue, I continued my journey through the first 20 years of hospital medicine as a field with the fourth installment, “Heat,” a focus on the rise in importance of patient experience and the Millennial generation’s arrival in our hospitalist workforce.

That brings us to the present and back to a factor that started our rise and is becoming more important than ever, both for us as a specialty and for our success as a country.

The Affordability Crisis

We have known for a long time how expensive healthcare is. If it wasn’t for managed care trying to control costs in the 80s and 90s, hospitalists might very well not even exist. But now, it isn’t just costly. It is unaffordable for the average family.

Table 1 shows projected healthcare costs and growth curves through 2021, with a median four-person household income overlaid.

In most scenarios, the two lines, income and healthcare costs, continue to get closer and closer—with healthcare costs almost $42,000 per family by 2021 in the most aggressive projection (8% growth). I am sure many of you have heard the phrase “bending the curve.” That simply means to try and bend that red line down to something approximating the blue line. It is slowing the growth, not actually decreasing the cost.

But it’s a step.

Only at that slowest healthcare growth rate projection (3%) does household income maintain pace. At the highest projection, two-thirds of family income will go toward healthcare. It simply won’t work. Affordability must be addressed.

Hospitalists are at the center of this storm. If you look at the various factors contributing to costs, we (and our keyboards) have great control and influence over inpatient, professional services, and pharmacy costs. To our credit, and to the credit of our teammates in the hospital, we actually seem to be bending the curve down toward the 5% range in inpatient care and professional services. Nevertheless, even at that level it is outpacing income growth.

In 2013, total healthcare costs for a family of four finally caught up with college costs. It is now just north of $22,000 per year for both healthcare costs and the annual cost of attending an in-state public college. Let’s not catch the private colleges as the biggest family budget buster.

The Triple Aim

So, over the course of five articles, I have talked about how we as hospitalists have faced and learned about key aspects of delivering care in a modern healthcare system. First, it was economics, then patient safety and quality, then patient experience, and now we’re back to economics as we consider patient affordability.

Wouldn’t it be great just to focus on one thing at a time? Unfortunately, life doesn’t work that way. In today’s world, hospitalists must give the best quality care while giving a great experience to their patients, all at an affordable cost. This concept of triple focus has given rise to a new term, “Triple Aim.”

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the phrase—and the idea—in 2006. It symbolizes an understanding that all three areas of quality MUST be joined together to achieve true success for our patients. As physicians and hospitalists, we have been taught to focus on health as the cornerstone of our profession. We know about cost pressures, and we now appreciate how important patient experience is. The problem has been that we tend to bounce back and forth in addressing these, silo to silo, depending on the circumstance—JCAHO [Joint Council on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations] visit, publication of CMS core measures, Press-Ganey scores.

Payers and public data sites already have moved away from just reporting health measures. Experience is nearly as prominent in the discussion now. Affordability measures and transparent pricing are on the verge, especially as we arrive in a world with value-based purchasing and cost bundling.

It is easy to focus on just the crisis of the moment. Today, that might very well be the affordability crisis, but it’s important to understand that when delivering healthcare to real live human beings, with all their complexities and vulnerabilities, we have to tune in to our most creative selves to come up with solutions that don’t just address individual areas of care but that also integrate and synergize.

Into the Future

So why this long, five-column preamble into our history, our grand social movement? Because our society and specialty, even with almost 20 years under our belts, are still in the early days. Our members know this and stay connected and coordinated, either in person, at our annual meeting, or virtually using HMX, to better face the many challenges today and those coming down the road. When SHM surveyed its members last year about why they had attended the annual meeting, the overwhelming response was to “be part of the hospital medicine movement.”

Our specialty started out as a group of one-offs and experiments and then coalesced into a social movement, and although it has changed directions and gathered new areas of focus, we are charging ahead. Much social, cultural, and medical change is to come. It’s why our members have told us they keep coming back—to share in this great and glorious social movement called hospital medicine.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

Focus on Patient Experience Strengthens Hospital Medicine Movement

“People don’t always remember what you say or even what you do, but they always remember how you made them feel.”—Maya Angelou

When SHM surveyed its members last year about why they had attended the annual meeting, the single most common response was to “be part of the hospital medicine movement.”

In the first three of my presidential columns, I talked about what that meant for the first 15 years of our specialty. HM’s rise occurred in the mid 1990s, during a time of despair in medicine, when pressures from rising costs and the new managed care industry upended the usual way of doing things, and then, around the turn of the century, amid a growing awareness that the care we had been delivering was wildly variable in quality—and often unsafe. Our field, created by members of the Baby Boomer generation, ultimately proved highly attractive to Generation X’ers, and our growth was accelerated by this new supply of young doctors. Fueled by the influx of dollars and attention brought on by the patient safety and quality movement, HM became the fastest growing medical specialty in history.

So, now we know what being part of the hospitalist movement meant before, but what does it mean today? Are the issues and drivers the same? I left my last column in 2006, with the partnership between the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), SHM, and six other key organizations to create the 5 Million Lives Campaign. It was an important year in several other ways, as what it meant to be a hospitalist began to change.

Enter the Millenials

In 2006 a new generation, the Millenials, born between 1985 and 2000, began entering medical schools across the country. This group, raised on a diet of positive reinforcement and cooperation, is characterized by confidence and a desire to work in teams. Born after the introduction of the Macintosh computer, Millenials are not just tech savvy; they have grown up in the world of social media and are digital media savvy. Even more than Gen X, Millenials strive for work-life balance. It almost seems this was a generation born and raised to be hospitalists!

Not only is their life philosophy different than the Boomers and X’ers before them, but their medical training has been unlike any before. From the moment they entered medical school, they were taught about patient quality and safety. To them, doctors aren’t the isolated pillars of strength and sole possessors of sacred knowledge that they used to be. They intuitively get that medicine is a team sport. In fact, most of the attendings on their ward rotations have been hospitalists.

Rise of Experience

In the early days of medicine, we as physicians understood that patients might not have the best experience, but that was just part of the deal, right? It’s just not supposed to be fun to be hospitalized—and sometimes you had to go through hell to get better. Those were the days of pure, unadulterated paternalism. We did things to patients to make them get better.

In the late 1970s, Irwin Press, PhD, began to study and lecture on patient satisfaction. In 1985, he joined forces with statistician Rod Ganey, PhD, to found Press Ganey Inc.1 Patient experience as a concept began to enter the conversation of hospital administration, especially around the one-dimensional idea that better experience could contribute to the better financial health of an organization.

During the rise of the patient safety and quality movement in the late 1990s and early 2000s, our zeal to improve care led us to begin doing many things for patients. But a collateral idea began to rise in importance, too—the idea that a patient’s experience was critical to improving quality, not just a tool to attract more patients.

The entire national quality infrastructure I described in my last column (CMS, JCAHO, AHRQ, NQF) began to work on adding experience to the suite of measurements being developed. In 2006, CMS introduced the HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey. This was a set of questions designed to be used at all hospitals nationwide, a significant development, because there was now a national standard for patient experience that could be compared over time and across hospitals anywhere in the country.2

In 2007, all hospitals subject to the Inpatient Prospective Payment System—pretty much all hospitals except critical access hospitals—were required to submit their HCAHPS survey data or face up to a 2% penalty. In 2008, this experience data was released publicly for the first time.2

And, of course, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) included HCAHPS results in calculating Hospital Value-Based Purchasing payments.3

The Institute of Medicine, in laying out a vision for better healthcare in 2012, called for more involvement of patients and families.

We are even seeing organizations creating leadership positions solely focused on patient experience. The Cleveland Clinic created the first physician leadership position dedicated to patient experience in the country, appointing Bridget Duffy, MD, a hospitalist, as its first chief experience officer in 2010. In 2012, Sound Physicians became the first hospitalist company to create such a position, to which it appointed Mark Rudolph, MD. Who would have imagined this 10 years ago?

Life for hospitalists has changed dramatically from the early 1990s to the Millenials now entering our workforce. The forces guiding our work and stimulating our growth have evolved, but the overarching theme of the last twenty years has been improvement. When the medical world took a cold hard look at the care being delivered, we suddenly saw a world of opportunities for improvement.

I talked before about how the rise of the patient safety and quality movement coincided perfectly with the emergence of hospitalists. Here I told you about how patient experience emerged in prominence as we, collectively, in becoming aware of our quality deficits, gained newfound empathy for what patients were going through. This focus on patient experience again plays into our strength and the opportunity we have as a specialty.

In the December issue of The Hospitalist, the final column in this five-part series will examine how to put it all together as we move toward the future of the field. But first I’ll introduce one last factor, a problem that helped launch our field and is now the greatest threat to our success.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

References

- Press Ganey Associates, Inc. A spark ignited nearly three decades ago. Available at: http://www.pressganey.com/aboutUs/ourHistory.aspx. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HCAHPS Fact Sheet. Available at: www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- American Hospital Association. Inpatient PPS. Available at: http://www.aha.org/advocacy-issues/medicare/ipps/index.shtml. Accessed August 31, 2014.

“People don’t always remember what you say or even what you do, but they always remember how you made them feel.”—Maya Angelou

When SHM surveyed its members last year about why they had attended the annual meeting, the single most common response was to “be part of the hospital medicine movement.”

In the first three of my presidential columns, I talked about what that meant for the first 15 years of our specialty. HM’s rise occurred in the mid 1990s, during a time of despair in medicine, when pressures from rising costs and the new managed care industry upended the usual way of doing things, and then, around the turn of the century, amid a growing awareness that the care we had been delivering was wildly variable in quality—and often unsafe. Our field, created by members of the Baby Boomer generation, ultimately proved highly attractive to Generation X’ers, and our growth was accelerated by this new supply of young doctors. Fueled by the influx of dollars and attention brought on by the patient safety and quality movement, HM became the fastest growing medical specialty in history.

So, now we know what being part of the hospitalist movement meant before, but what does it mean today? Are the issues and drivers the same? I left my last column in 2006, with the partnership between the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), SHM, and six other key organizations to create the 5 Million Lives Campaign. It was an important year in several other ways, as what it meant to be a hospitalist began to change.

Enter the Millenials

In 2006 a new generation, the Millenials, born between 1985 and 2000, began entering medical schools across the country. This group, raised on a diet of positive reinforcement and cooperation, is characterized by confidence and a desire to work in teams. Born after the introduction of the Macintosh computer, Millenials are not just tech savvy; they have grown up in the world of social media and are digital media savvy. Even more than Gen X, Millenials strive for work-life balance. It almost seems this was a generation born and raised to be hospitalists!

Not only is their life philosophy different than the Boomers and X’ers before them, but their medical training has been unlike any before. From the moment they entered medical school, they were taught about patient quality and safety. To them, doctors aren’t the isolated pillars of strength and sole possessors of sacred knowledge that they used to be. They intuitively get that medicine is a team sport. In fact, most of the attendings on their ward rotations have been hospitalists.

Rise of Experience

In the early days of medicine, we as physicians understood that patients might not have the best experience, but that was just part of the deal, right? It’s just not supposed to be fun to be hospitalized—and sometimes you had to go through hell to get better. Those were the days of pure, unadulterated paternalism. We did things to patients to make them get better.

In the late 1970s, Irwin Press, PhD, began to study and lecture on patient satisfaction. In 1985, he joined forces with statistician Rod Ganey, PhD, to found Press Ganey Inc.1 Patient experience as a concept began to enter the conversation of hospital administration, especially around the one-dimensional idea that better experience could contribute to the better financial health of an organization.

During the rise of the patient safety and quality movement in the late 1990s and early 2000s, our zeal to improve care led us to begin doing many things for patients. But a collateral idea began to rise in importance, too—the idea that a patient’s experience was critical to improving quality, not just a tool to attract more patients.

The entire national quality infrastructure I described in my last column (CMS, JCAHO, AHRQ, NQF) began to work on adding experience to the suite of measurements being developed. In 2006, CMS introduced the HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey. This was a set of questions designed to be used at all hospitals nationwide, a significant development, because there was now a national standard for patient experience that could be compared over time and across hospitals anywhere in the country.2

In 2007, all hospitals subject to the Inpatient Prospective Payment System—pretty much all hospitals except critical access hospitals—were required to submit their HCAHPS survey data or face up to a 2% penalty. In 2008, this experience data was released publicly for the first time.2

And, of course, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) included HCAHPS results in calculating Hospital Value-Based Purchasing payments.3

The Institute of Medicine, in laying out a vision for better healthcare in 2012, called for more involvement of patients and families.

We are even seeing organizations creating leadership positions solely focused on patient experience. The Cleveland Clinic created the first physician leadership position dedicated to patient experience in the country, appointing Bridget Duffy, MD, a hospitalist, as its first chief experience officer in 2010. In 2012, Sound Physicians became the first hospitalist company to create such a position, to which it appointed Mark Rudolph, MD. Who would have imagined this 10 years ago?

Life for hospitalists has changed dramatically from the early 1990s to the Millenials now entering our workforce. The forces guiding our work and stimulating our growth have evolved, but the overarching theme of the last twenty years has been improvement. When the medical world took a cold hard look at the care being delivered, we suddenly saw a world of opportunities for improvement.

I talked before about how the rise of the patient safety and quality movement coincided perfectly with the emergence of hospitalists. Here I told you about how patient experience emerged in prominence as we, collectively, in becoming aware of our quality deficits, gained newfound empathy for what patients were going through. This focus on patient experience again plays into our strength and the opportunity we have as a specialty.

In the December issue of The Hospitalist, the final column in this five-part series will examine how to put it all together as we move toward the future of the field. But first I’ll introduce one last factor, a problem that helped launch our field and is now the greatest threat to our success.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

References

- Press Ganey Associates, Inc. A spark ignited nearly three decades ago. Available at: http://www.pressganey.com/aboutUs/ourHistory.aspx. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HCAHPS Fact Sheet. Available at: www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- American Hospital Association. Inpatient PPS. Available at: http://www.aha.org/advocacy-issues/medicare/ipps/index.shtml. Accessed August 31, 2014.

“People don’t always remember what you say or even what you do, but they always remember how you made them feel.”—Maya Angelou

When SHM surveyed its members last year about why they had attended the annual meeting, the single most common response was to “be part of the hospital medicine movement.”

In the first three of my presidential columns, I talked about what that meant for the first 15 years of our specialty. HM’s rise occurred in the mid 1990s, during a time of despair in medicine, when pressures from rising costs and the new managed care industry upended the usual way of doing things, and then, around the turn of the century, amid a growing awareness that the care we had been delivering was wildly variable in quality—and often unsafe. Our field, created by members of the Baby Boomer generation, ultimately proved highly attractive to Generation X’ers, and our growth was accelerated by this new supply of young doctors. Fueled by the influx of dollars and attention brought on by the patient safety and quality movement, HM became the fastest growing medical specialty in history.

So, now we know what being part of the hospitalist movement meant before, but what does it mean today? Are the issues and drivers the same? I left my last column in 2006, with the partnership between the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), SHM, and six other key organizations to create the 5 Million Lives Campaign. It was an important year in several other ways, as what it meant to be a hospitalist began to change.

Enter the Millenials

In 2006 a new generation, the Millenials, born between 1985 and 2000, began entering medical schools across the country. This group, raised on a diet of positive reinforcement and cooperation, is characterized by confidence and a desire to work in teams. Born after the introduction of the Macintosh computer, Millenials are not just tech savvy; they have grown up in the world of social media and are digital media savvy. Even more than Gen X, Millenials strive for work-life balance. It almost seems this was a generation born and raised to be hospitalists!

Not only is their life philosophy different than the Boomers and X’ers before them, but their medical training has been unlike any before. From the moment they entered medical school, they were taught about patient quality and safety. To them, doctors aren’t the isolated pillars of strength and sole possessors of sacred knowledge that they used to be. They intuitively get that medicine is a team sport. In fact, most of the attendings on their ward rotations have been hospitalists.

Rise of Experience

In the early days of medicine, we as physicians understood that patients might not have the best experience, but that was just part of the deal, right? It’s just not supposed to be fun to be hospitalized—and sometimes you had to go through hell to get better. Those were the days of pure, unadulterated paternalism. We did things to patients to make them get better.

In the late 1970s, Irwin Press, PhD, began to study and lecture on patient satisfaction. In 1985, he joined forces with statistician Rod Ganey, PhD, to found Press Ganey Inc.1 Patient experience as a concept began to enter the conversation of hospital administration, especially around the one-dimensional idea that better experience could contribute to the better financial health of an organization.

During the rise of the patient safety and quality movement in the late 1990s and early 2000s, our zeal to improve care led us to begin doing many things for patients. But a collateral idea began to rise in importance, too—the idea that a patient’s experience was critical to improving quality, not just a tool to attract more patients.

The entire national quality infrastructure I described in my last column (CMS, JCAHO, AHRQ, NQF) began to work on adding experience to the suite of measurements being developed. In 2006, CMS introduced the HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey. This was a set of questions designed to be used at all hospitals nationwide, a significant development, because there was now a national standard for patient experience that could be compared over time and across hospitals anywhere in the country.2

In 2007, all hospitals subject to the Inpatient Prospective Payment System—pretty much all hospitals except critical access hospitals—were required to submit their HCAHPS survey data or face up to a 2% penalty. In 2008, this experience data was released publicly for the first time.2

And, of course, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) included HCAHPS results in calculating Hospital Value-Based Purchasing payments.3

The Institute of Medicine, in laying out a vision for better healthcare in 2012, called for more involvement of patients and families.

We are even seeing organizations creating leadership positions solely focused on patient experience. The Cleveland Clinic created the first physician leadership position dedicated to patient experience in the country, appointing Bridget Duffy, MD, a hospitalist, as its first chief experience officer in 2010. In 2012, Sound Physicians became the first hospitalist company to create such a position, to which it appointed Mark Rudolph, MD. Who would have imagined this 10 years ago?

Life for hospitalists has changed dramatically from the early 1990s to the Millenials now entering our workforce. The forces guiding our work and stimulating our growth have evolved, but the overarching theme of the last twenty years has been improvement. When the medical world took a cold hard look at the care being delivered, we suddenly saw a world of opportunities for improvement.

I talked before about how the rise of the patient safety and quality movement coincided perfectly with the emergence of hospitalists. Here I told you about how patient experience emerged in prominence as we, collectively, in becoming aware of our quality deficits, gained newfound empathy for what patients were going through. This focus on patient experience again plays into our strength and the opportunity we have as a specialty.

In the December issue of The Hospitalist, the final column in this five-part series will examine how to put it all together as we move toward the future of the field. But first I’ll introduce one last factor, a problem that helped launch our field and is now the greatest threat to our success.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

References

- Press Ganey Associates, Inc. A spark ignited nearly three decades ago. Available at: http://www.pressganey.com/aboutUs/ourHistory.aspx. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HCAHPS Fact Sheet. Available at: www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- American Hospital Association. Inpatient PPS. Available at: http://www.aha.org/advocacy-issues/medicare/ipps/index.shtml. Accessed August 31, 2014.

Hospital Patient Safety, Quality Movement Helped Propel Hospitalists

Hippocrates, Epidemics.“The Physician must be able to do good or to do no harm.”

This is part three of my ongoing series on the journey of hospital medicine and how we are poised for greater things yet. In part one, “Tinder and Spark,” macro changes in the American healthcare landscape pressured primary care physicians to get creative with new ways to practice, the most prominent result being the creation of hospitalist practices. Wachter and Goldman provided the spark that gave the field its name and cohesiveness. In part two, “Fuel,” the Baby Boomers shaped the field, setting the stage for the Generation X physicians who fueled HM’s early growth.

But the field might have stagnated there, the fire attenuated, if not for the rise of something new, something that stoked our growth to new heights.

Orlando, Fla., December 2006.

SHM President-Elect Rusty Holman, MD, MHM, was on stage representing hospitalists at the annual Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) National Forum in front of more than 5,000 enthusiastic attendees representing every discipline of clinical care from hundreds of healthcare organizations across the country and internationally. This was a special event. Two years earlier, IHI President Don Berwick, MD, MPP, had launched an audacious campaign, called the 100,000 Lives Campaign, that aimed to prevent the deaths of 100,000 patients in our nation’s hospitals in the following 18 months, not by utilizing some great new technological advance but by changing the culture around safety and quality in our nation’s hospitals and enacting proven safety methods and processes.1 Out of this plan came widespread use of terms and programs that weren’t widely adopted then but are familiar to all of us now: rapid response teams, medicine reconciliation, surgical site infection prevention, and ventilator-acquired pneumonia.

That program estimated that it saved 122,000 lives.1

IHI was looking to build on the safety and quality infrastructure that had been built up to make the 100,000 Lives Campaign a success and to launch an even bigger program. The 5 Million Lives Campaign’s goal was to reduce incidents of harm in five million patients over the next two years. For this campaign, IHI understood that success could only be achieved with partners. SHM and the field of hospital medicine, which had grown in size and influence, was seen as a critical and influential partner in achieving the goal of reducing harm in our nation’s hospitals. Thus, Dr. Holman was standing on that stage for SHM at the launch of the biggest safety and quality initiative in our nation’s history. SHM was among seven partner organizations, including the American Nurses Association, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the American Heart Association, and the CDC. SHM was the only medical society represented. Pretty heady stuff for a field barely 10 years old. How did we get there? For that story, we need to go back a few years.

In 1984, Libby Zion, an 18-year-old college student, died from serotonin syndrome. A contributing factor was felt to be overworked residents not getting enough sleep. In his landmark 1990 article, “Human Factors in Hazardous Situations,” James Reason, PhD, introduced the world to some key concepts: active versus latent errors and the Swiss cheese model of errors.2 These concepts influence our thinking to this day. In 1994, Betsy Lehman, a health reporter for the Boston Globe, died from a massive chemotherapy overdose. That same year Lucian Leape, MD, a Harvard pediatric surgeon, published his influential article in JAMA, “Errors in Medicine,” which called for a systems approach to improving patient safety.3

These key moments in safety and quality, all of which occurred in the years leading up to hospitalists gaining their identity, were but a prelude to the widespread patient safety and quality movement. Like our own social movement, “Patient Safety and Quality” was born with an influential publication. This was the 1999 release of the Institute of Medicine’s “To Err is Human,” a report that reiterated claims that up to 98,000 U.S. patients per year were dying from medical errors.4 It also supported Dr. Leape’s earlier work calling for systems changes. In 2001, the Institute of Medicine published a second report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” which introduced the six aims for healthcare improvement: safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered.5

Before 1999, hospitalists were just getting their feet on the ground. Groups were experimenting with practice models and recruiting young talent, mostly with a pitch for a new way to practice with freedom to design their day and often an interesting work schedule.

After the publication of “To Err is Human” in 1999, changes in patient safety and quality began to accelerate. Taking one of the recommendations from “To Err is Human,” which suggested that employers should use their market power to improve quality and safety, the Leapfrog Group, a consortium of large employers, organized in 2000. Leapfrog began rewarding and recognizing hospitals that put accepted safety measures in place.6 Suddenly, hospital CEOs began to see tangible rewards for improving quality in their hospitals.

Here is where the hospitalist movement and the patient safety and quality movement began to intersect.

Shift to Quality and Safety

In 2001, the same year “Crossing the Quality Chasm” was published, Congress created the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety within the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Significant funding was suddenly available for quality and safety research, and a more organized reporting mechanism for quality would soon be available.

In 2002, the Joint Commission released its first set of National Patient Safety Goals. There were seven, and key goals for hospitalists included improving the effectiveness of communication among caregivers, reducing the risk of healthcare-acquired infections, and reconciling medications.

And, lastly, as if that weren’t enough activity in the patient safety and quality world, the Joint Commission and CMS released in 2003 the first joint, aligned set of core measures, with which we are all now very familiar, around acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia.

Hospital executives were trying to get a handle on the meaning of this flurry of activity for their hospitals. It certainly meant new regulatory requirements. It probably meant greater visibility to the public around what happened behind the walls of their facilities. No doubt dollars on the line wouldn’t be too far behind. They needed help, and they needed it fast.

No longer were hospitalists a small group of young docs roaming the halls; now, instead of just taking care of one patient at a time, they were reaching the threshold of size—and even status in some organizations—where they could leverage their working knowledge of the system and presence on site to affect the various facets of quality now being measured and incented. Additionally, as the information technology (IT) revolution rolled out, hospitalists, mostly tech-savvy Gen X’ers, looked to ease the transition into the new world of EHRs, which promised to serve as a new base for improving quality.

As the C-suite continued making value calculations in their heads, they saw that, in addition to helping them manage the many facets of the transition of primary care and specialty teaching attendings out of the hospital, hospitalists could now be a powerful weapon in helping them stay competitive in the looming patient safety and quality revolution. They pulled out their checkbooks.

When SHM first started gathering data to explore this gap, we discovered that in 2003 the reported median support per FTE of an adult hospitalist in this country was $60,000.7 With an estimated 11,000 hospitalists in the country at that time, C-suite funders paid out over $600 million to help overcome the deficit between hospitalist professional billings and salary and benefits. By the time SHM partnered with IHI on the 5 Million Lives Campaign in 2006, the figure stood at well over $2 billion. The 2011 SHM/Medical Group Management Association survey data showed $139,090 support per FTE. With 31,000 U.S. hospitalists estimated at the time, that figure had doubled to over $4 billion in just five years’ time.

The new generation of doctors had come along in the late 1990s looking for a practice that fit their wants and needs. HM gave them what they were looking for: autonomy, the promise of work-life balance, and the ability to help patients in their most vulnerable time. The traditional E&M [evaluation and management]-based funding mechanisms simply weren’t designed to account for physicians who spend all of their time doing the critical cognitive and coordinating clinical work. To account for this, hospitals and medical groups, seeing the value to their organizations in this new specialty, anteed up to cover the difference. That gave us a great beginning.

But it was the convergence of the early hospitalist movement and the emergent patient safety and quality movement that created a synergy that propelled both movements forward. Boosted by the influx of funding directly and indirectly related to patient safety and quality, hospitalists grew in number from an estimated 5,000 physicians at the 1999 publication of “To Err is Human” to north of 40,000 today.

The synergy was evident when SHM President-Elect Dr. Holman, representing our fledgling specialty and society, faced that cheering throng in Orlando alongside Dr. Don Berwick, the face of the patient safety and quality movement.

But that’s not quite the end of the story.

To get us up to the present and on to our bright future, there will be a few more additions to the quality story and an all-new generation arriving on the scene to shake things up.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

References

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Overview of the 100,000 Lives Campaign. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Completed/5MillionLivesCampaign/Documents/Overview%20of%20the%20100K%20Campaign.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2014.

- Broadbent DE, Reason J, Baddeley A, eds. Human Factors in Hazardous Situations: Proceedings of a Royal Society Discussion Meeting Held on 28 and 29 June 1989. Gloucestershire, England: Clarendon Press; 1990:475-484.

- Leape LL. Error in medicine JAMA.1994;272(23):1851-1857.

- Institute of Medicine. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, D.C.: The National Academy Press; 2000.

- Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: The National Academy Press; 2001.

- The Leapfrog Group. About Leapfrog. Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/about_leapfrog. Accessed July 6, 2014.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine Surveys 2003-2012. Available at: www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey. Accessed July 3, 2014.

Hippocrates, Epidemics.“The Physician must be able to do good or to do no harm.”

This is part three of my ongoing series on the journey of hospital medicine and how we are poised for greater things yet. In part one, “Tinder and Spark,” macro changes in the American healthcare landscape pressured primary care physicians to get creative with new ways to practice, the most prominent result being the creation of hospitalist practices. Wachter and Goldman provided the spark that gave the field its name and cohesiveness. In part two, “Fuel,” the Baby Boomers shaped the field, setting the stage for the Generation X physicians who fueled HM’s early growth.

But the field might have stagnated there, the fire attenuated, if not for the rise of something new, something that stoked our growth to new heights.

Orlando, Fla., December 2006.

SHM President-Elect Rusty Holman, MD, MHM, was on stage representing hospitalists at the annual Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) National Forum in front of more than 5,000 enthusiastic attendees representing every discipline of clinical care from hundreds of healthcare organizations across the country and internationally. This was a special event. Two years earlier, IHI President Don Berwick, MD, MPP, had launched an audacious campaign, called the 100,000 Lives Campaign, that aimed to prevent the deaths of 100,000 patients in our nation’s hospitals in the following 18 months, not by utilizing some great new technological advance but by changing the culture around safety and quality in our nation’s hospitals and enacting proven safety methods and processes.1 Out of this plan came widespread use of terms and programs that weren’t widely adopted then but are familiar to all of us now: rapid response teams, medicine reconciliation, surgical site infection prevention, and ventilator-acquired pneumonia.

That program estimated that it saved 122,000 lives.1

IHI was looking to build on the safety and quality infrastructure that had been built up to make the 100,000 Lives Campaign a success and to launch an even bigger program. The 5 Million Lives Campaign’s goal was to reduce incidents of harm in five million patients over the next two years. For this campaign, IHI understood that success could only be achieved with partners. SHM and the field of hospital medicine, which had grown in size and influence, was seen as a critical and influential partner in achieving the goal of reducing harm in our nation’s hospitals. Thus, Dr. Holman was standing on that stage for SHM at the launch of the biggest safety and quality initiative in our nation’s history. SHM was among seven partner organizations, including the American Nurses Association, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the American Heart Association, and the CDC. SHM was the only medical society represented. Pretty heady stuff for a field barely 10 years old. How did we get there? For that story, we need to go back a few years.

In 1984, Libby Zion, an 18-year-old college student, died from serotonin syndrome. A contributing factor was felt to be overworked residents not getting enough sleep. In his landmark 1990 article, “Human Factors in Hazardous Situations,” James Reason, PhD, introduced the world to some key concepts: active versus latent errors and the Swiss cheese model of errors.2 These concepts influence our thinking to this day. In 1994, Betsy Lehman, a health reporter for the Boston Globe, died from a massive chemotherapy overdose. That same year Lucian Leape, MD, a Harvard pediatric surgeon, published his influential article in JAMA, “Errors in Medicine,” which called for a systems approach to improving patient safety.3

These key moments in safety and quality, all of which occurred in the years leading up to hospitalists gaining their identity, were but a prelude to the widespread patient safety and quality movement. Like our own social movement, “Patient Safety and Quality” was born with an influential publication. This was the 1999 release of the Institute of Medicine’s “To Err is Human,” a report that reiterated claims that up to 98,000 U.S. patients per year were dying from medical errors.4 It also supported Dr. Leape’s earlier work calling for systems changes. In 2001, the Institute of Medicine published a second report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” which introduced the six aims for healthcare improvement: safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered.5

Before 1999, hospitalists were just getting their feet on the ground. Groups were experimenting with practice models and recruiting young talent, mostly with a pitch for a new way to practice with freedom to design their day and often an interesting work schedule.