User login

Long-acting injectable aripiprazole lauroxil for schizophrenia

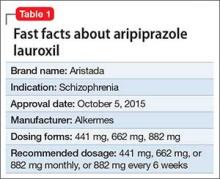

Approximately 80% of patients with schizophrenia relapse within 5 years1 despite the availability and increased use of second-generation antipsychotics. Long-acting depot formulations are a proven, effective treatment option for patients with schizophrenia. In October 2015, another long-acting injectable antipsychotic, aripiprazole lauroxil, was FDA-approved for schizophrenia.2 Aripiprazole lauroxil is administered IM every 4 to 6 weeks in the deltoid or gluteal region and is available in multiple dosages (Table 1).

Mechanism of action

Aripiprazole lauroxil is a prodrug of aripiprazole. Prodrugs are chemical compounds that exert their pharmacological effects after they undergo a biologic transformation and transform into a more active metabolite.3 The development of prodrugs is an established method used to improve physio-chemical or pharmacokinetic properties of the pharmacologically active compound.

After IM injection, aripiprazole lauroxil is most likely converted by an enzyme-mediated hydrolysis to N-hydroxymethyl aripiprazole, which is then hydrolyzed to aripiprazole. Aripiprazole’s mechanism of action is mediated through a combination of partial agonist activity at D2 and 5-HT1A receptors and antagonistic activity at 5-HT2A receptors.2,4

Dosing and administration

If your patient has never taken aripiprazole, ensure that she (he) will tolerate the drug by initiating a trial of oral aripiprazole before beginning treatment with aripiprazole lauroxil; establishing tolerability might take as long as 2 weeks because of the half-life of aripiprazole.

Aripiprazole lauroxil can be started at 441 mg, 662 mg, or 882 mg administered monthly; these dosages correspond to 300 mg, 450 mg, and 600 mg of aripiprazole, or 10 mg/d, 15 mg/d, ≥20 mg/d of oral aripiprazole, respectively (Table 2).2 Aripiprazole lauroxil can be administered either in the deltoid muscle (441 mg only) or gluteal muscle (441 mg, 662 mg, or 882 mg).2,4,5 Treatment with the 441-mg, 662-mg, or 882-mg dosages can be given every 4 weeks but the 882-mg dosage can be given every 6 weeks and only in the gluteal muscle, which provides greater dosing flexibility compared with extended-release injectable aripiprazole.2,4,5

Supplementation with oral aripiprazole is required for 21 days before the first aripiprazole lauroxil injection.2,4 The next injection should not be given earlier than 14 days after the previous dose. When a dose is missed, follow the guidelines outlined in Table 3.2

After a single injection, aripiprazole starts to appear in the systemic circulation at Day 5 or Day 6 and continues to be released for another 36 days.2 Steady-state concentration will be reached after the fourth monthly injection. The termination half-life of aripiprazole lauroxil ranged from 29 to 35 days after each monthly injection.2

Packaging. Aripiprazole lauroxil is available as single-dose, pre-filled, color-coded syringes for IM injection at 441 mg (light blue), 662 mg (green), and 882 mg (burgundy); syringes do not require refrigeration (Table 2).2 The syringe needs to be tapped at least 10 times to dislodge any material that might have settled. Shake the syringe vigorously for at least 30 seconds to ensure a uniform suspension. Shake it again for 30 seconds if the syringe is not used within 15 minutes.2

Efficacy

The efficacy of aripiprazole lauroxil for treating patients with schizophrenia has been established, in part, on the basis of efficacy data from clinical trials of oral aripiprazole. In addition, efficacy has been established in a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, fixed-dose study of 622 individuals age 18 to 70 with schizophrenia.4,5 All eligible patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia as defined by DSM-IV-TR criteria and confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders, Clinical Trial Version and were experiencing an acute exacerbation of their illness at the time of the study. To be eligible for the study, participants had to have a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of 70 to 120 and score of ≥4 for ≥2 of the selected positive items (delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, and suspiciousness/persecution). Individuals also were required to have a Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale score of ≥4. Efficacy was assessed using the PANSS and Clinical Global Impression–Improvement scale (CGI-I).

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive IM aripiprazole lauroxil, 441 mg, aripiprazole lauroxil, 882 mg, or placebo once monthly in the gluteal region for 12 weeks. The gluteal muscle was selected as the injection site to maintain blinding to the study drug.4,5 After establishing tolerability to oral aripiprazole, participants received oral aripiprazole or placebo daily for the first 3 weeks. The IM injections were administered on Days 1, 29, and 57.

Efficacy was measured primarily as change in total PANSS score from the baseline to day 854,5; secondary efficacy variable was the CGI-I score at day 85. Statistically significant separation in PANSS score was observed in each aripiprazole lauroxil dosage group (441 mg and 882 mg) compared with placebo. Significant improvement in both active treatment groups was observed as early as Day 8 and continued throughout the study (P ≤ .004). The number of patients who improved much or very much on the CGI-I was significantly greater in either aripiprazole lauroxil group, compared with placebo (P < .001).

Contraindications

Allergic reactions. Patients who are hypersensitive to oral aripiprazole should not receive aripiprazole lauroxil. Hypersensitivity reactions have ranged from pruritus and urticaria to anaphylaxis.2

Drug−drug interactions. Reduce aripiprazole lauroxil dosage to the next lower dosage when used in combination with strong cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inhibitors (eg, itraconazole, clarithromycin) or strong CYP2D6 inhibitors (eg, quinidine, fluoxetine, paroxetine) for more than 2 weeks or if the patient is known to be a poor metabolizer of CYP2D6, because concentration of aripiprazole lauroxil could increase. No dose adjustment is required if the patient is already taking 441 mg/month or if CYP450 modulators are added for less than 2 weeks.2 Similarly, a dosage increase is recommended when aripiprazole lauroxil is used in combination with strong CYP3A4 inducers (eg, carbamazepine, rifampin).2

Overdose

No data are available on aripiprazole lauroxil overdose. However, there is one known case of oral aripiprazole overdose in a patient who ingested 1,260 mg of oral aripiprazole (42 times the maximum recommended daily dosage) but recovered completely.2 Common side effects reported in at least 5% of all overdose cases include vomiting, somnolence, and tremor. If an overdose occurs, call a poison control center immediately.

‘Black-box’ warning for patients with dementia

Aripiprazole lauroxil, similar to all other atypical antipsychotics, has a “black-box” warning stating that (1) it is not approved for treating dementia-related psychosis, and (2) it is associated with an increased risk of death with off-label use to treat behavioral problems in older adults with dementia-related psychosis.2 Meta-analysis of 17 placebo-controlled trials in patients taking an atypical antipsychotic (olanzapine, aripiprazole, risperidone, or quetiapine) revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients 1.6 to 1.7 times that of placebo-treated patients.6

Adverse reactions

The overall safety profile of aripiprazole lauroxil is similar to that of oral aripiprazole. Most commonly observed adverse reaction during clinical trials of aripiprazole lauroxil was akathisia (incidence ≥5% and at least twice rate seen with placebo).2 Other common adverse reactions are shown in Table 4.2 Recently, the FDA issued a warning that compulsive or uncontrollable urges to gamble, binge eat, shop, and have sex have been reported with all formulations of aripiprazole.7 According to reports, these urges stopped when the drug was discontinued or the dosage reduced. Although rare, these impulse-control problems could result in harm if they are not recognized. See the full prescribing information for a complete set of adverse reactions.

BOTTOM LINE

Aripiprazole lauroxil is a novel, long-acting second-generation antipsychotic that offers flexibility in terms of safe and effective dosing and can be administered in the deltoid (441 mg) or gluteal muscle (626 mg and 882 mg) and at dosing intervals of 4 to 6 weeks. Safety and tolerability profile of aripiprazole lauroxil are similar to that of oral aripiprazole. Aripiprazole lauroxil represents a new treatment option for patients with schizophrenia.

Related Resources

- Kennedy WK. When and how to use long-acting injectable antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):40-43.

- Citrome L, Du Y, Risinger R, et al. Effect of aripiprazole lauroxil on agitation and hostility in patients with schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(2):69-75.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole extended-release • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Itraconazole • Sporanox

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Quinidine • Quinidex

Rifampin • Rifadin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Acknowledgement

Maaz A. Khan, a student at the University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma, contributed to this article.

1. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

2. Aristada [package insert]. Waltham, MA; Alkermes; 2015.

3. Turncliff R, Hard M, Du Y, et al. Relative bioavailability and safety of aripiprazole lauroxil, a novel once-monthly, long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic following deltoid and gluteal administration in adult subjects with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;159(2-3):404-410.

4. Meltzer HY, Risinger R, Nasrallah HA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of aripiprazole lauroxil in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(8):1085-1090.

5. Citrome L. Aripiprazole long-acting injectable formulations for schizophrenia: aripiprazole monohydrate and aripiprazole lauroxil. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(2):169-186.

6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Public health advisory: deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm053171. Published April 11, 2005. Accessed April 29, 2016.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about new impulse-control problems associated with mental health drug aripiprazole (Abilify, Abilify Maintena, Aristada). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm498662.htm. Published May 3, 2016. Accessed June 20, 2016.

Approximately 80% of patients with schizophrenia relapse within 5 years1 despite the availability and increased use of second-generation antipsychotics. Long-acting depot formulations are a proven, effective treatment option for patients with schizophrenia. In October 2015, another long-acting injectable antipsychotic, aripiprazole lauroxil, was FDA-approved for schizophrenia.2 Aripiprazole lauroxil is administered IM every 4 to 6 weeks in the deltoid or gluteal region and is available in multiple dosages (Table 1).

Mechanism of action

Aripiprazole lauroxil is a prodrug of aripiprazole. Prodrugs are chemical compounds that exert their pharmacological effects after they undergo a biologic transformation and transform into a more active metabolite.3 The development of prodrugs is an established method used to improve physio-chemical or pharmacokinetic properties of the pharmacologically active compound.

After IM injection, aripiprazole lauroxil is most likely converted by an enzyme-mediated hydrolysis to N-hydroxymethyl aripiprazole, which is then hydrolyzed to aripiprazole. Aripiprazole’s mechanism of action is mediated through a combination of partial agonist activity at D2 and 5-HT1A receptors and antagonistic activity at 5-HT2A receptors.2,4

Dosing and administration

If your patient has never taken aripiprazole, ensure that she (he) will tolerate the drug by initiating a trial of oral aripiprazole before beginning treatment with aripiprazole lauroxil; establishing tolerability might take as long as 2 weeks because of the half-life of aripiprazole.

Aripiprazole lauroxil can be started at 441 mg, 662 mg, or 882 mg administered monthly; these dosages correspond to 300 mg, 450 mg, and 600 mg of aripiprazole, or 10 mg/d, 15 mg/d, ≥20 mg/d of oral aripiprazole, respectively (Table 2).2 Aripiprazole lauroxil can be administered either in the deltoid muscle (441 mg only) or gluteal muscle (441 mg, 662 mg, or 882 mg).2,4,5 Treatment with the 441-mg, 662-mg, or 882-mg dosages can be given every 4 weeks but the 882-mg dosage can be given every 6 weeks and only in the gluteal muscle, which provides greater dosing flexibility compared with extended-release injectable aripiprazole.2,4,5

Supplementation with oral aripiprazole is required for 21 days before the first aripiprazole lauroxil injection.2,4 The next injection should not be given earlier than 14 days after the previous dose. When a dose is missed, follow the guidelines outlined in Table 3.2

After a single injection, aripiprazole starts to appear in the systemic circulation at Day 5 or Day 6 and continues to be released for another 36 days.2 Steady-state concentration will be reached after the fourth monthly injection. The termination half-life of aripiprazole lauroxil ranged from 29 to 35 days after each monthly injection.2

Packaging. Aripiprazole lauroxil is available as single-dose, pre-filled, color-coded syringes for IM injection at 441 mg (light blue), 662 mg (green), and 882 mg (burgundy); syringes do not require refrigeration (Table 2).2 The syringe needs to be tapped at least 10 times to dislodge any material that might have settled. Shake the syringe vigorously for at least 30 seconds to ensure a uniform suspension. Shake it again for 30 seconds if the syringe is not used within 15 minutes.2

Efficacy

The efficacy of aripiprazole lauroxil for treating patients with schizophrenia has been established, in part, on the basis of efficacy data from clinical trials of oral aripiprazole. In addition, efficacy has been established in a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, fixed-dose study of 622 individuals age 18 to 70 with schizophrenia.4,5 All eligible patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia as defined by DSM-IV-TR criteria and confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders, Clinical Trial Version and were experiencing an acute exacerbation of their illness at the time of the study. To be eligible for the study, participants had to have a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of 70 to 120 and score of ≥4 for ≥2 of the selected positive items (delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, and suspiciousness/persecution). Individuals also were required to have a Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale score of ≥4. Efficacy was assessed using the PANSS and Clinical Global Impression–Improvement scale (CGI-I).

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive IM aripiprazole lauroxil, 441 mg, aripiprazole lauroxil, 882 mg, or placebo once monthly in the gluteal region for 12 weeks. The gluteal muscle was selected as the injection site to maintain blinding to the study drug.4,5 After establishing tolerability to oral aripiprazole, participants received oral aripiprazole or placebo daily for the first 3 weeks. The IM injections were administered on Days 1, 29, and 57.

Efficacy was measured primarily as change in total PANSS score from the baseline to day 854,5; secondary efficacy variable was the CGI-I score at day 85. Statistically significant separation in PANSS score was observed in each aripiprazole lauroxil dosage group (441 mg and 882 mg) compared with placebo. Significant improvement in both active treatment groups was observed as early as Day 8 and continued throughout the study (P ≤ .004). The number of patients who improved much or very much on the CGI-I was significantly greater in either aripiprazole lauroxil group, compared with placebo (P < .001).

Contraindications

Allergic reactions. Patients who are hypersensitive to oral aripiprazole should not receive aripiprazole lauroxil. Hypersensitivity reactions have ranged from pruritus and urticaria to anaphylaxis.2

Drug−drug interactions. Reduce aripiprazole lauroxil dosage to the next lower dosage when used in combination with strong cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inhibitors (eg, itraconazole, clarithromycin) or strong CYP2D6 inhibitors (eg, quinidine, fluoxetine, paroxetine) for more than 2 weeks or if the patient is known to be a poor metabolizer of CYP2D6, because concentration of aripiprazole lauroxil could increase. No dose adjustment is required if the patient is already taking 441 mg/month or if CYP450 modulators are added for less than 2 weeks.2 Similarly, a dosage increase is recommended when aripiprazole lauroxil is used in combination with strong CYP3A4 inducers (eg, carbamazepine, rifampin).2

Overdose

No data are available on aripiprazole lauroxil overdose. However, there is one known case of oral aripiprazole overdose in a patient who ingested 1,260 mg of oral aripiprazole (42 times the maximum recommended daily dosage) but recovered completely.2 Common side effects reported in at least 5% of all overdose cases include vomiting, somnolence, and tremor. If an overdose occurs, call a poison control center immediately.

‘Black-box’ warning for patients with dementia

Aripiprazole lauroxil, similar to all other atypical antipsychotics, has a “black-box” warning stating that (1) it is not approved for treating dementia-related psychosis, and (2) it is associated with an increased risk of death with off-label use to treat behavioral problems in older adults with dementia-related psychosis.2 Meta-analysis of 17 placebo-controlled trials in patients taking an atypical antipsychotic (olanzapine, aripiprazole, risperidone, or quetiapine) revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients 1.6 to 1.7 times that of placebo-treated patients.6

Adverse reactions

The overall safety profile of aripiprazole lauroxil is similar to that of oral aripiprazole. Most commonly observed adverse reaction during clinical trials of aripiprazole lauroxil was akathisia (incidence ≥5% and at least twice rate seen with placebo).2 Other common adverse reactions are shown in Table 4.2 Recently, the FDA issued a warning that compulsive or uncontrollable urges to gamble, binge eat, shop, and have sex have been reported with all formulations of aripiprazole.7 According to reports, these urges stopped when the drug was discontinued or the dosage reduced. Although rare, these impulse-control problems could result in harm if they are not recognized. See the full prescribing information for a complete set of adverse reactions.

BOTTOM LINE

Aripiprazole lauroxil is a novel, long-acting second-generation antipsychotic that offers flexibility in terms of safe and effective dosing and can be administered in the deltoid (441 mg) or gluteal muscle (626 mg and 882 mg) and at dosing intervals of 4 to 6 weeks. Safety and tolerability profile of aripiprazole lauroxil are similar to that of oral aripiprazole. Aripiprazole lauroxil represents a new treatment option for patients with schizophrenia.

Related Resources

- Kennedy WK. When and how to use long-acting injectable antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):40-43.

- Citrome L, Du Y, Risinger R, et al. Effect of aripiprazole lauroxil on agitation and hostility in patients with schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(2):69-75.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole extended-release • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Itraconazole • Sporanox

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Quinidine • Quinidex

Rifampin • Rifadin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Acknowledgement

Maaz A. Khan, a student at the University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma, contributed to this article.

Approximately 80% of patients with schizophrenia relapse within 5 years1 despite the availability and increased use of second-generation antipsychotics. Long-acting depot formulations are a proven, effective treatment option for patients with schizophrenia. In October 2015, another long-acting injectable antipsychotic, aripiprazole lauroxil, was FDA-approved for schizophrenia.2 Aripiprazole lauroxil is administered IM every 4 to 6 weeks in the deltoid or gluteal region and is available in multiple dosages (Table 1).

Mechanism of action

Aripiprazole lauroxil is a prodrug of aripiprazole. Prodrugs are chemical compounds that exert their pharmacological effects after they undergo a biologic transformation and transform into a more active metabolite.3 The development of prodrugs is an established method used to improve physio-chemical or pharmacokinetic properties of the pharmacologically active compound.

After IM injection, aripiprazole lauroxil is most likely converted by an enzyme-mediated hydrolysis to N-hydroxymethyl aripiprazole, which is then hydrolyzed to aripiprazole. Aripiprazole’s mechanism of action is mediated through a combination of partial agonist activity at D2 and 5-HT1A receptors and antagonistic activity at 5-HT2A receptors.2,4

Dosing and administration

If your patient has never taken aripiprazole, ensure that she (he) will tolerate the drug by initiating a trial of oral aripiprazole before beginning treatment with aripiprazole lauroxil; establishing tolerability might take as long as 2 weeks because of the half-life of aripiprazole.

Aripiprazole lauroxil can be started at 441 mg, 662 mg, or 882 mg administered monthly; these dosages correspond to 300 mg, 450 mg, and 600 mg of aripiprazole, or 10 mg/d, 15 mg/d, ≥20 mg/d of oral aripiprazole, respectively (Table 2).2 Aripiprazole lauroxil can be administered either in the deltoid muscle (441 mg only) or gluteal muscle (441 mg, 662 mg, or 882 mg).2,4,5 Treatment with the 441-mg, 662-mg, or 882-mg dosages can be given every 4 weeks but the 882-mg dosage can be given every 6 weeks and only in the gluteal muscle, which provides greater dosing flexibility compared with extended-release injectable aripiprazole.2,4,5

Supplementation with oral aripiprazole is required for 21 days before the first aripiprazole lauroxil injection.2,4 The next injection should not be given earlier than 14 days after the previous dose. When a dose is missed, follow the guidelines outlined in Table 3.2

After a single injection, aripiprazole starts to appear in the systemic circulation at Day 5 or Day 6 and continues to be released for another 36 days.2 Steady-state concentration will be reached after the fourth monthly injection. The termination half-life of aripiprazole lauroxil ranged from 29 to 35 days after each monthly injection.2

Packaging. Aripiprazole lauroxil is available as single-dose, pre-filled, color-coded syringes for IM injection at 441 mg (light blue), 662 mg (green), and 882 mg (burgundy); syringes do not require refrigeration (Table 2).2 The syringe needs to be tapped at least 10 times to dislodge any material that might have settled. Shake the syringe vigorously for at least 30 seconds to ensure a uniform suspension. Shake it again for 30 seconds if the syringe is not used within 15 minutes.2

Efficacy

The efficacy of aripiprazole lauroxil for treating patients with schizophrenia has been established, in part, on the basis of efficacy data from clinical trials of oral aripiprazole. In addition, efficacy has been established in a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, fixed-dose study of 622 individuals age 18 to 70 with schizophrenia.4,5 All eligible patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia as defined by DSM-IV-TR criteria and confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders, Clinical Trial Version and were experiencing an acute exacerbation of their illness at the time of the study. To be eligible for the study, participants had to have a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of 70 to 120 and score of ≥4 for ≥2 of the selected positive items (delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, and suspiciousness/persecution). Individuals also were required to have a Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale score of ≥4. Efficacy was assessed using the PANSS and Clinical Global Impression–Improvement scale (CGI-I).

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive IM aripiprazole lauroxil, 441 mg, aripiprazole lauroxil, 882 mg, or placebo once monthly in the gluteal region for 12 weeks. The gluteal muscle was selected as the injection site to maintain blinding to the study drug.4,5 After establishing tolerability to oral aripiprazole, participants received oral aripiprazole or placebo daily for the first 3 weeks. The IM injections were administered on Days 1, 29, and 57.

Efficacy was measured primarily as change in total PANSS score from the baseline to day 854,5; secondary efficacy variable was the CGI-I score at day 85. Statistically significant separation in PANSS score was observed in each aripiprazole lauroxil dosage group (441 mg and 882 mg) compared with placebo. Significant improvement in both active treatment groups was observed as early as Day 8 and continued throughout the study (P ≤ .004). The number of patients who improved much or very much on the CGI-I was significantly greater in either aripiprazole lauroxil group, compared with placebo (P < .001).

Contraindications

Allergic reactions. Patients who are hypersensitive to oral aripiprazole should not receive aripiprazole lauroxil. Hypersensitivity reactions have ranged from pruritus and urticaria to anaphylaxis.2

Drug−drug interactions. Reduce aripiprazole lauroxil dosage to the next lower dosage when used in combination with strong cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inhibitors (eg, itraconazole, clarithromycin) or strong CYP2D6 inhibitors (eg, quinidine, fluoxetine, paroxetine) for more than 2 weeks or if the patient is known to be a poor metabolizer of CYP2D6, because concentration of aripiprazole lauroxil could increase. No dose adjustment is required if the patient is already taking 441 mg/month or if CYP450 modulators are added for less than 2 weeks.2 Similarly, a dosage increase is recommended when aripiprazole lauroxil is used in combination with strong CYP3A4 inducers (eg, carbamazepine, rifampin).2

Overdose

No data are available on aripiprazole lauroxil overdose. However, there is one known case of oral aripiprazole overdose in a patient who ingested 1,260 mg of oral aripiprazole (42 times the maximum recommended daily dosage) but recovered completely.2 Common side effects reported in at least 5% of all overdose cases include vomiting, somnolence, and tremor. If an overdose occurs, call a poison control center immediately.

‘Black-box’ warning for patients with dementia

Aripiprazole lauroxil, similar to all other atypical antipsychotics, has a “black-box” warning stating that (1) it is not approved for treating dementia-related psychosis, and (2) it is associated with an increased risk of death with off-label use to treat behavioral problems in older adults with dementia-related psychosis.2 Meta-analysis of 17 placebo-controlled trials in patients taking an atypical antipsychotic (olanzapine, aripiprazole, risperidone, or quetiapine) revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients 1.6 to 1.7 times that of placebo-treated patients.6

Adverse reactions

The overall safety profile of aripiprazole lauroxil is similar to that of oral aripiprazole. Most commonly observed adverse reaction during clinical trials of aripiprazole lauroxil was akathisia (incidence ≥5% and at least twice rate seen with placebo).2 Other common adverse reactions are shown in Table 4.2 Recently, the FDA issued a warning that compulsive or uncontrollable urges to gamble, binge eat, shop, and have sex have been reported with all formulations of aripiprazole.7 According to reports, these urges stopped when the drug was discontinued or the dosage reduced. Although rare, these impulse-control problems could result in harm if they are not recognized. See the full prescribing information for a complete set of adverse reactions.

BOTTOM LINE

Aripiprazole lauroxil is a novel, long-acting second-generation antipsychotic that offers flexibility in terms of safe and effective dosing and can be administered in the deltoid (441 mg) or gluteal muscle (626 mg and 882 mg) and at dosing intervals of 4 to 6 weeks. Safety and tolerability profile of aripiprazole lauroxil are similar to that of oral aripiprazole. Aripiprazole lauroxil represents a new treatment option for patients with schizophrenia.

Related Resources

- Kennedy WK. When and how to use long-acting injectable antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):40-43.

- Citrome L, Du Y, Risinger R, et al. Effect of aripiprazole lauroxil on agitation and hostility in patients with schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(2):69-75.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole extended-release • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Itraconazole • Sporanox

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Quinidine • Quinidex

Rifampin • Rifadin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Acknowledgement

Maaz A. Khan, a student at the University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma, contributed to this article.

1. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

2. Aristada [package insert]. Waltham, MA; Alkermes; 2015.

3. Turncliff R, Hard M, Du Y, et al. Relative bioavailability and safety of aripiprazole lauroxil, a novel once-monthly, long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic following deltoid and gluteal administration in adult subjects with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;159(2-3):404-410.

4. Meltzer HY, Risinger R, Nasrallah HA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of aripiprazole lauroxil in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(8):1085-1090.

5. Citrome L. Aripiprazole long-acting injectable formulations for schizophrenia: aripiprazole monohydrate and aripiprazole lauroxil. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(2):169-186.

6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Public health advisory: deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm053171. Published April 11, 2005. Accessed April 29, 2016.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about new impulse-control problems associated with mental health drug aripiprazole (Abilify, Abilify Maintena, Aristada). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm498662.htm. Published May 3, 2016. Accessed June 20, 2016.

1. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

2. Aristada [package insert]. Waltham, MA; Alkermes; 2015.

3. Turncliff R, Hard M, Du Y, et al. Relative bioavailability and safety of aripiprazole lauroxil, a novel once-monthly, long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic following deltoid and gluteal administration in adult subjects with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;159(2-3):404-410.

4. Meltzer HY, Risinger R, Nasrallah HA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of aripiprazole lauroxil in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(8):1085-1090.

5. Citrome L. Aripiprazole long-acting injectable formulations for schizophrenia: aripiprazole monohydrate and aripiprazole lauroxil. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(2):169-186.

6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Public health advisory: deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm053171. Published April 11, 2005. Accessed April 29, 2016.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about new impulse-control problems associated with mental health drug aripiprazole (Abilify, Abilify Maintena, Aristada). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm498662.htm. Published May 3, 2016. Accessed June 20, 2016.

Reducing morbidity and mortality from common medical conditions in schizophrenia

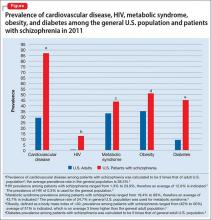

Life expectancy for both males and females has been increasing over the past several decades to an average of 76 years. However, the life expectancy among individuals with schizophrenia in the United States is 61 years—a 20% reduction.1 Patients with schizophrenia are known to be at increased risk of several comorbid medical conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with healthy people (Figure, page 32).2-5 This risk may be heightened by several factors, including sedentary lifestyle, a high rate of cigarette use, poor self-management skills, homelessness, and poor diet.

Although substantial attention is paid to the psychiatric and behavioral management of schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of patients’ medical conditions, which have been implicated in excess unforeseen deaths. Patients with schizophrenia might experience delays in diagnosis, leading to more acute comorbidity at time of diagnosis and premature mortality

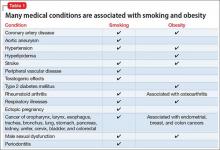

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among psychiatric patients.6 Key risk factors for cardiovascular disease include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more prevalent among patients with schizophrenia.7 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.8 In general, smoking and obesity are the most modifiable and preventable risk factors for many medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and many forms of cancer (Table 1).

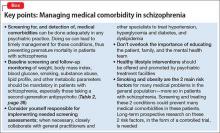

In this article, we discuss how to manage common medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia. Comprehensive management for all these medical conditions in this population is beyond the scope of this article; we limit ourselves to discussing (1) how common these conditions are in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population and (2) what can be done in psychiatric practice to manage these medical comorbidities (Box).

Obesity

Obesity—defined as body mass index (BMI) of >30—is common among patients with schizophrenia. The condition leads to poor self-image, decreased treatment adherence, and an increased risk of many chronic medical conditions (Table 1). Being overweight or obese can increase stigma and social discrimination, which will undermine self-esteem and, in turn, affect adherence with medications, leading to relapse.

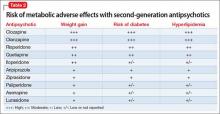

The prevalence of obesity among patients with schizophrenia is almost double that of the general population9 (Figure2-5). Several factors predispose these patients to overweight or obese, including sedentary lifestyle, lack of exercise, a high-fat diet, medications side effects, and genetic factors. Recent studies report the incidence of weight gain among patients treated with antipsychotics is as high as 80%10 (Table 2).

Mechanisms involved in antipsychotic-induced weight gain are not completely understood, but antagonism of serotonergic (5-HT2C, 5-HT1A), histamine (H1), dopamine (D2), muscarinic, and other receptors are involved in modulation of food intake. Decreased energy expenditure also has been blamed for antipsychotic-induced weight gain.10

Pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery can be as effective among patients with schizophrenia as they are among the general population. Maintaining a BMI of <25 kg/m2 lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6 Metformin has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing some metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia,11 and should be considered early when treating at-risk patients.

Managing obesity. Clinicians can apply several measures to manage obesity in a patient with schizophrenia:

- Educate the patient, and the family, about the risks of being overweight or obese.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Advise smoking cessation.

- When clinically appropriate, switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of weight gain—eg, from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2, page 36).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin with an antipsychotic; the drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in an overweight patient with schizophrenia.11

- Encourage the patient to engage in modest physical activity; for example, a 20-minute walk, every day, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Recommend a formal lifestyle modification program, such as behavioral group-based treatment for weight reduction.12

- Refer the patient and family to a dietitian.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

There is strong association between T2DM and schizophrenia that is related to abnormal glucose regulation independent of any adverse medication effect.13 Ryan et al14 reported that first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia had a higher level of intra-abdominal fat than age- and BMI-matched healthy controls, suggesting that schizophrenia could be associated with changes in adiposity that might increase the risk of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and dyslipidemia. Mechanisms that increase the risk of T2DM in schizophrenia include genetic and environmental factors, such as family history, lack of physical activity, and poor diet.

Diagnosis. All patients with schizophrenia should be evaluated for undiagnosed diabetes. The diagnosis of T2DM is made by documenting:

- a fasting plasma glucose reading of ≥126 mg/dL

- symptoms of T2DM, along with a random plasma glucose reading of ≥200 mg/dL

- 2-hour reading of a plasma glucose level >200 mg/dL on an oral glucose tolerance test.

Recent guidelines also suggest using a hemoglobin A1c value cutoff of ≥6.5% to diagnose T2DM.

In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, 38% of patients with schizophrenia and diabetes were not receiving any treatment for T2DM.15

Risk factors for T2DM are:

- BMI >25

- a first-degree relative with diabetes

- lack of physical activity

- being a member of a high-risk ethnic group (African American, Hispanic American, Native American, Asian American, or Pacific Islander)

- having delivered a baby >9 lb or having had gestational diabetes

- hypertension

- high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level of ≤35 mg/dL

- triglyceride level of ≥250 mg/dL

- history of an abnormal glucose tolerance test

- history of abnormal findings on a fasting plasma glucose test

- history of vascular disease.

Early detection and management.

- Educate the patient and family about signs and symptoms of T2DM, such as polyuria, nocturia, polydipsia, fatigue, visual disturbances, and (in women) vulvitis. Also, psychiatrists should be aware of, and inquire about, symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis.

- At the start of therapy with any antipsychotic, particularly a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), ask patients about a family history of diabetes and measure the hemoglobin A1c value.

- Monitor the hemoglobin A1c level 4 months after starting an antipsychotic, then annually, in a patient with significant risk factors for diabetes.

- Monitor blood glucose every 6 months in patients with no change from initial results and more frequently in those with significant risk factors for diabetes and those who gain weight.

- Order a lipid panel and measure the serum glucose level to rule out dyslipidemia and diabetes, because a patient with high lipid levels and diabetes is at higher risk of developing cardiovascular conditions.

- Advocate for smoking cessation.

- Switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of diabetes when clinically appropriate, such as switching a patient from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (such as haloperidol or perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin along with antipsychotics. Metformin has been used to improve insulin sensitivity and can lead to weight loss in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. The drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia.11 Metformin is simple to use, does not lead to hypoglycemia, does not require serum glucose monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile.11

- Educate the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk every day reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Refer the patient to a dietitian to develop an appropriate diet plan.

- When diabetes is diagnosed, ensure appropriate follow-up and initiation or continuation of therapy with a general practitioner or an endocrinologist.

- Reinforce the need for ongoing follow-up and compliance with therapy for diabetes.

Hyperlipidemia and dyslipidemia

Elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels are associated with cardiovascular diseases, such as ischemic heart disease and myocardial infarction. A 10% increase in cholesterol levels is associated with a 20% to 30% increase in the risk of coronary artery disease; lowering cholesterol by 10% decreases the risk by 20% to 30%.16 Triglyceride levels ≥250 mg/dL are associated with 2-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease.16

The incidence of dyslipidemia is not as well studied as diabetes in patients with schizophrenia. There is increased prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population because of obesity, lack of physical activity, and poor dietary habits.16

Data regarding the effects of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) on lipid levels are limited, but high-potency drugs, such as haloperidol, seem to carry a lower risk of hyperlipidemia than low-potency drugs, such as chlorpromazine and thioridazine.17 A comprehensive review on the effects of SGAs on plasma lipid levels suggested that clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine are associated with a higher risk of dyslipidemia17 (Table 2).

In the CATIE study, olanzapine and clozapine were associated with a greater increase in the serum level of cholesterol and triglycerides compared with other antipsychotics, even after adjusting for treatment duration. Furthermore, a retrospective chart review of patients who switched to aripiprazole from other SGAs showed a decrease in levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol15 (Table 2).

Patients with schizophrenia are more likely to have dyslipidemia go undiagnosed, and therefore are less likely to be treated for the disorder. In the CATIE study, 88% of patients with dyslipidemia were not receiving any treatment.15

Management for dyslipidemia.

- Educate the patient and family about risks involved with dyslipidemia.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Monitor lipids to rule out dyslipidemia. Obtain a pretreatment fasting or random lipid profile for any patient receiving an antipsychotic; repeat at least every 6 months after starting the antipsychotic.

- Counsel the patient to quit smoking.

- Switch to an antipsychotic with lower risk of weight gain and dyslipidemia, such as switching from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotics (such as, haloperidol or perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2).

- Educate and encourage the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk everyday will reduce cardiovascular disease risk by 35% to 55%.6

- Refer to a dietitian if indicated.

- Ensure follow-up and initiation of treatment with a general practitioner.

- Educate and encourage the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk everyday will reduce cardiovascular disease risk by 35% to 55%.

Metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is cluster of cardiovascular risk factors, including central adiposity, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. The National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III report defines metabolic syndrome as the presence of 3 of 5 of the following factors:

- abdominal obesity (waist circumference of >40 inches in men, or >35 inches in women)

- triglyceride level, >150 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol, <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women

- blood pressure, >130/85 mm Hg

- fasting plasma glucose level, >110 mg/dL.

The presence of metabolic syndrome in the general population is a strong predictor of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.18 The adverse effects of metabolic syndrome are thought to relate to atherogenic dyslipidemia, higher blood pressure, insulin resistance with or without glucose intolerance, a proinflammatory state, and a prothrombotic state.

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia is 2- to 3-fold higher than the general population.19 In the CATIE study, approximately one-third of patients met criteria for metabolic syndrome at baseline.15 In a prospective study, De Hert et al20 reported that patients who were started on a SGA had more than twice the rate of developing metabolic syndrome compared with those treated with a FGA (Table 2). Other possible causes of metabolic syndrome are visceral adiposity and insulin resistance.16Management of the metabolic syndrome involves addressing the individual components that have been described in the preceding sections on T2DM and dyslipidemia.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is thought to be the most common blood-borne illness, with an estimated prevalence of 1% of the U.S. population. Some studies suggest that as many as 16% of people with schizophrenia have HCV infection.4 Risk factors for HCV infection include unsafe sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality, homelessness, and IV drug use.

HCV treatments typically have involved regimens with interferon alfa, which is associated with significant neuropsychiatric side effects, including depression and suicide. There is a dearth of research on treatment of HCV in patients with schizophrenia; however, at least 1 study suggests that there was no increase in psychiatric symptoms in patients treated with interferon-containing regimens.21 There is even less evidence to guide the use of newer, non-interferon–based HCV treatment regimens that are better tolerated and have a higher response rate in the general population; there is reason, however, to be hopeful about their potential in patients with schizophrenia and HCV infection.

Managing HCV infection.

- Educate the patients and family about risk factors associated with contracting HCV.

- Screen for HCV infection in patients with schizophrenia because there is higher prevalence of HCV in these patients compared with the general population.

- When HCV infection is diagnosed, educate the patients and family about available treatments.

- Facilitate referral to an HCV specialist for appropriate treatment.

HIV/AIDS

HIV infection is highly prevalent among people suffering from severe mental illness such as schizophrenia. The incidence of HIV/AIDS in patients with schizophrenia is estimated to be 4% to 23%, compared with 0.6% in the general population.22 Risk factors associated with a higher incidence of HIV/AIDS in patients with schizophrenia are lack of knowledge about contracting HIV, unsafe sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality, homelessness, and IV drug use.22

Managing HIV/AIDS.

- Educate the patient and family about risk factors associated with contracting HIV/AIDS.

- Educate patients about safe sex practices.

- All patients with schizophrenia should be screened for HIV because there is 10-fold higher HIV prevalence in schizophrenia compared with the general population.

- When HIV infection is diagnosed, facilitate referral to a HIV or infectious disease specialist for treatment.

- Educate the patient in whom HIV/AIDS has been diagnosed about the importance of (1) adherence to his (her) HIV medication regimen and (2) follow-up visits with an infectious disease practitioner and appropriate laboratory tests.

- Educate the patient’s family and significant other about the illness.

- Screen for and treat substance use.

- At each visit, inquire about the patient’s adherence to HIV medical therapy, viral load, and CD4 cell count.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Patients with schizophrenia are more likely to suffer from respiratory disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma, compared with the general population.23 Smoking is a major risk factor for COPD. In a study by Dickerson et al,24 64% of people with schizophrenia were current smokers, compared with 19% of those without mental illness.

A high rate of smoking rate among people with schizophrenia suggests a “self-medication” hypothesis: That is, stimulation of CNS nicotinic cholinergic receptors treats the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and overcomes the dopamine blocking effects of antipsychotics.25 Among SGAs, only clozapine has a substantial body of evidence to support its association with decreased smoking behavior.

Managing COPD.

- Educate the patient and family about risk factors associated with COPD and smoking.

- Screen for tobacco use at each visit; try to increase motivation to quit smoking.

- Educate the patients and family about the value and availability of smoking cessation programs.

- Prescribe medication to help with smoking cessation when needed. Bupropion and varenicline have been shown to be effective in patients with schizophrenia; nicotine replacement therapies are safe and can be helpful.

- When treating a patient who is in the process of quitting, encourage and help him to maintain his commitment and enlist support from his family.

- Refer to an appropriate medical provider (primary care provider or pulmonologist) for a patient with an established or suspected diagnosis of COPD.

Cancer

Since 1909, when the Board of Control of the Commissioners in Lunacy for England and Wales noted the possibility of a decreased incidence in cancer among psychiatric patients, this connection has been a matter of controversy.26 Subsequent research has been equivocal; the prevalence of cancer has been reported to be either increased, similar, or decreased compared with the general population.26-28 Risk factors for cancer, including smoking, obesity, poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, and hyperprolactinemia, are more common among patients with schizophrenia.

Genetic factors and a possible protective effect from antipsychotics have been cited as potential causes of decreased prevalence. Clozapine is associated with an increased risk of leukemia. No conclusion can be drawn about the overall prevalence of cancer in schizophrenia.

Managing cancer in a patient with schizophrenia, however, poses a significant challenge29; he might lack capacity to make decisions about cancer treatment. The patient—or his surrogate decision-makers—need to carefully weigh current quality of life against potential benefits of treatment and risks of side effects. Adherence to complex, often toxic, therapies can be challenging for the patient with psychosis. Successful cancer treatment often requires close collaboration between the cancer treatment team and the patient’s support system, including the treating psychiatrist and case management teams.

Bottom Line

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk of developing comorbid medical

conditions because of the illness itself, lifestyle behaviors, genetics, and adverse

effects of medications. Because mental health clinicians focus attention on the

psychiatric and behavioral aspect of treatment, often there is delay in screening,

detecting, and treating medical comorbidities. This screening can be done in any

psychiatric practice, which can lead to timely management for those conditions

and preventing premature mortality in patients with schizophrenia.

1. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212-217.

2. De Hert M, Correl CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorder. I. Prevalence, impact of medications, and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77.

3. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics update-2011 update. Circulation. 2011;123(4):e18-e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701.

4. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31-37.

5. Lovre D, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Trends in prevalence of the metabolic syndrome. JAMA. 2015;314(9):950.

6. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1115-1121.

7. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical point. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):17-25.

8. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

9. Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Heo M et al. The distribution of body mass index among individuals with and without schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(4):215-220.

10. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(11):1686-1696.

11. Jarskog LF, Hamer RM, Catellier DJ, et al; METS Investigators. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

12. Ganguli R. Behavioral therapy for weight loss in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 4):19-25.

13. Kohen D. Diabetes mellitus and schizophrenia: historical perspective. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;47:S64-S66.

14. Ryan MC, Flanagan S, Kinsella U, et al. The effects of atypical antipsychotics on visceral fat distribution in first episode, drug naïve patients with schizophrenia. Life Sci. 2004;74(16):1999-2008.

15. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):19-32.

16. Barnett AH, Mackin P, Chaudhry I, et al. Minimising metabolic and cardiovascular risk in schizophrenia: diabetes, obesity and dyslipidaemia. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21(4):357-373.

17. Meyer JM, Koro CE. The effects of antipsychotic therapy on serum lipids: a comprehensive review. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(1):1-17.

18. Sacks FM. Metabolic syndrome: epidemiology and consequences. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 18):3-12.

19. De Hert M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, et al. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(1):15-22.

20. De Hert M, Hanssens L, Wampers M, et al. Prevalence and incidence rates of metabolic abnormalities and diabetes in a prospective study of patients treated with second-generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:560.

21. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Pavawalla S, et al. The influence of antiviral therapy on psychiatric symptoms among patients with hepatitis C and schizophrenia. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(1):111-119.

22. Davidson S, Judd F, Jolley D, et al. Risk factors for HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C among the chronic mentally ill. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(2):203-209.

23. Copeland LA, Mortensen EM, Zeber JE, et al. Pulmonary disease among inpatient decendents: impact of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(3):720-726.

24. Dickerson F, Stallings CR, Origoni AE, et al. Cigarette smoking among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in routine clinical settings, 1999-2011. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(1):44-50.

25. Dalack GW, Healy DJ, Meador-Woodruff JH. Nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: clinical phenomena and laboratory findings. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1490-1501.

26. Hodgson R, Wildgust HJ, Bushe CJ. Cancer and schizophrenia: is there a paradox? J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):51-60.

27. Hippisley-Cox J, Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, et al. Risk of malignancy in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: nested case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1368-1376.

28. Grinshpoon A, Barchana M, Ponizovsky A, et al. Cancer in schizophrenia: is the risk higher or lower? Schizophr Res. 2005;73(2-3):333-341.

29. Hwang M, Farasatpour M, Williams CD, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer patients with schizophrenia. Oncol Lett. 2012;3(4):845-850.

Life expectancy for both males and females has been increasing over the past several decades to an average of 76 years. However, the life expectancy among individuals with schizophrenia in the United States is 61 years—a 20% reduction.1 Patients with schizophrenia are known to be at increased risk of several comorbid medical conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with healthy people (Figure, page 32).2-5 This risk may be heightened by several factors, including sedentary lifestyle, a high rate of cigarette use, poor self-management skills, homelessness, and poor diet.

Although substantial attention is paid to the psychiatric and behavioral management of schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of patients’ medical conditions, which have been implicated in excess unforeseen deaths. Patients with schizophrenia might experience delays in diagnosis, leading to more acute comorbidity at time of diagnosis and premature mortality

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among psychiatric patients.6 Key risk factors for cardiovascular disease include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more prevalent among patients with schizophrenia.7 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.8 In general, smoking and obesity are the most modifiable and preventable risk factors for many medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and many forms of cancer (Table 1).

In this article, we discuss how to manage common medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia. Comprehensive management for all these medical conditions in this population is beyond the scope of this article; we limit ourselves to discussing (1) how common these conditions are in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population and (2) what can be done in psychiatric practice to manage these medical comorbidities (Box).

Obesity

Obesity—defined as body mass index (BMI) of >30—is common among patients with schizophrenia. The condition leads to poor self-image, decreased treatment adherence, and an increased risk of many chronic medical conditions (Table 1). Being overweight or obese can increase stigma and social discrimination, which will undermine self-esteem and, in turn, affect adherence with medications, leading to relapse.

The prevalence of obesity among patients with schizophrenia is almost double that of the general population9 (Figure2-5). Several factors predispose these patients to overweight or obese, including sedentary lifestyle, lack of exercise, a high-fat diet, medications side effects, and genetic factors. Recent studies report the incidence of weight gain among patients treated with antipsychotics is as high as 80%10 (Table 2).

Mechanisms involved in antipsychotic-induced weight gain are not completely understood, but antagonism of serotonergic (5-HT2C, 5-HT1A), histamine (H1), dopamine (D2), muscarinic, and other receptors are involved in modulation of food intake. Decreased energy expenditure also has been blamed for antipsychotic-induced weight gain.10

Pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery can be as effective among patients with schizophrenia as they are among the general population. Maintaining a BMI of <25 kg/m2 lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6 Metformin has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing some metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia,11 and should be considered early when treating at-risk patients.

Managing obesity. Clinicians can apply several measures to manage obesity in a patient with schizophrenia:

- Educate the patient, and the family, about the risks of being overweight or obese.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Advise smoking cessation.

- When clinically appropriate, switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of weight gain—eg, from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2, page 36).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin with an antipsychotic; the drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in an overweight patient with schizophrenia.11

- Encourage the patient to engage in modest physical activity; for example, a 20-minute walk, every day, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Recommend a formal lifestyle modification program, such as behavioral group-based treatment for weight reduction.12

- Refer the patient and family to a dietitian.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

There is strong association between T2DM and schizophrenia that is related to abnormal glucose regulation independent of any adverse medication effect.13 Ryan et al14 reported that first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia had a higher level of intra-abdominal fat than age- and BMI-matched healthy controls, suggesting that schizophrenia could be associated with changes in adiposity that might increase the risk of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and dyslipidemia. Mechanisms that increase the risk of T2DM in schizophrenia include genetic and environmental factors, such as family history, lack of physical activity, and poor diet.

Diagnosis. All patients with schizophrenia should be evaluated for undiagnosed diabetes. The diagnosis of T2DM is made by documenting:

- a fasting plasma glucose reading of ≥126 mg/dL

- symptoms of T2DM, along with a random plasma glucose reading of ≥200 mg/dL

- 2-hour reading of a plasma glucose level >200 mg/dL on an oral glucose tolerance test.

Recent guidelines also suggest using a hemoglobin A1c value cutoff of ≥6.5% to diagnose T2DM.

In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, 38% of patients with schizophrenia and diabetes were not receiving any treatment for T2DM.15

Risk factors for T2DM are:

- BMI >25

- a first-degree relative with diabetes

- lack of physical activity

- being a member of a high-risk ethnic group (African American, Hispanic American, Native American, Asian American, or Pacific Islander)

- having delivered a baby >9 lb or having had gestational diabetes

- hypertension

- high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level of ≤35 mg/dL

- triglyceride level of ≥250 mg/dL

- history of an abnormal glucose tolerance test

- history of abnormal findings on a fasting plasma glucose test

- history of vascular disease.

Early detection and management.

- Educate the patient and family about signs and symptoms of T2DM, such as polyuria, nocturia, polydipsia, fatigue, visual disturbances, and (in women) vulvitis. Also, psychiatrists should be aware of, and inquire about, symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis.

- At the start of therapy with any antipsychotic, particularly a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), ask patients about a family history of diabetes and measure the hemoglobin A1c value.

- Monitor the hemoglobin A1c level 4 months after starting an antipsychotic, then annually, in a patient with significant risk factors for diabetes.

- Monitor blood glucose every 6 months in patients with no change from initial results and more frequently in those with significant risk factors for diabetes and those who gain weight.

- Order a lipid panel and measure the serum glucose level to rule out dyslipidemia and diabetes, because a patient with high lipid levels and diabetes is at higher risk of developing cardiovascular conditions.

- Advocate for smoking cessation.

- Switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of diabetes when clinically appropriate, such as switching a patient from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (such as haloperidol or perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin along with antipsychotics. Metformin has been used to improve insulin sensitivity and can lead to weight loss in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. The drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia.11 Metformin is simple to use, does not lead to hypoglycemia, does not require serum glucose monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile.11

- Educate the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk every day reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Refer the patient to a dietitian to develop an appropriate diet plan.

- When diabetes is diagnosed, ensure appropriate follow-up and initiation or continuation of therapy with a general practitioner or an endocrinologist.

- Reinforce the need for ongoing follow-up and compliance with therapy for diabetes.

Hyperlipidemia and dyslipidemia

Elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels are associated with cardiovascular diseases, such as ischemic heart disease and myocardial infarction. A 10% increase in cholesterol levels is associated with a 20% to 30% increase in the risk of coronary artery disease; lowering cholesterol by 10% decreases the risk by 20% to 30%.16 Triglyceride levels ≥250 mg/dL are associated with 2-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease.16

The incidence of dyslipidemia is not as well studied as diabetes in patients with schizophrenia. There is increased prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population because of obesity, lack of physical activity, and poor dietary habits.16

Data regarding the effects of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) on lipid levels are limited, but high-potency drugs, such as haloperidol, seem to carry a lower risk of hyperlipidemia than low-potency drugs, such as chlorpromazine and thioridazine.17 A comprehensive review on the effects of SGAs on plasma lipid levels suggested that clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine are associated with a higher risk of dyslipidemia17 (Table 2).

In the CATIE study, olanzapine and clozapine were associated with a greater increase in the serum level of cholesterol and triglycerides compared with other antipsychotics, even after adjusting for treatment duration. Furthermore, a retrospective chart review of patients who switched to aripiprazole from other SGAs showed a decrease in levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol15 (Table 2).

Patients with schizophrenia are more likely to have dyslipidemia go undiagnosed, and therefore are less likely to be treated for the disorder. In the CATIE study, 88% of patients with dyslipidemia were not receiving any treatment.15

Management for dyslipidemia.

- Educate the patient and family about risks involved with dyslipidemia.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Monitor lipids to rule out dyslipidemia. Obtain a pretreatment fasting or random lipid profile for any patient receiving an antipsychotic; repeat at least every 6 months after starting the antipsychotic.

- Counsel the patient to quit smoking.

- Switch to an antipsychotic with lower risk of weight gain and dyslipidemia, such as switching from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotics (such as, haloperidol or perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2).

- Educate and encourage the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk everyday will reduce cardiovascular disease risk by 35% to 55%.6

- Refer to a dietitian if indicated.

- Ensure follow-up and initiation of treatment with a general practitioner.

- Educate and encourage the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk everyday will reduce cardiovascular disease risk by 35% to 55%.

Metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is cluster of cardiovascular risk factors, including central adiposity, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. The National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III report defines metabolic syndrome as the presence of 3 of 5 of the following factors:

- abdominal obesity (waist circumference of >40 inches in men, or >35 inches in women)

- triglyceride level, >150 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol, <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women

- blood pressure, >130/85 mm Hg

- fasting plasma glucose level, >110 mg/dL.

The presence of metabolic syndrome in the general population is a strong predictor of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.18 The adverse effects of metabolic syndrome are thought to relate to atherogenic dyslipidemia, higher blood pressure, insulin resistance with or without glucose intolerance, a proinflammatory state, and a prothrombotic state.

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia is 2- to 3-fold higher than the general population.19 In the CATIE study, approximately one-third of patients met criteria for metabolic syndrome at baseline.15 In a prospective study, De Hert et al20 reported that patients who were started on a SGA had more than twice the rate of developing metabolic syndrome compared with those treated with a FGA (Table 2). Other possible causes of metabolic syndrome are visceral adiposity and insulin resistance.16Management of the metabolic syndrome involves addressing the individual components that have been described in the preceding sections on T2DM and dyslipidemia.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is thought to be the most common blood-borne illness, with an estimated prevalence of 1% of the U.S. population. Some studies suggest that as many as 16% of people with schizophrenia have HCV infection.4 Risk factors for HCV infection include unsafe sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality, homelessness, and IV drug use.

HCV treatments typically have involved regimens with interferon alfa, which is associated with significant neuropsychiatric side effects, including depression and suicide. There is a dearth of research on treatment of HCV in patients with schizophrenia; however, at least 1 study suggests that there was no increase in psychiatric symptoms in patients treated with interferon-containing regimens.21 There is even less evidence to guide the use of newer, non-interferon–based HCV treatment regimens that are better tolerated and have a higher response rate in the general population; there is reason, however, to be hopeful about their potential in patients with schizophrenia and HCV infection.

Managing HCV infection.

- Educate the patients and family about risk factors associated with contracting HCV.

- Screen for HCV infection in patients with schizophrenia because there is higher prevalence of HCV in these patients compared with the general population.

- When HCV infection is diagnosed, educate the patients and family about available treatments.

- Facilitate referral to an HCV specialist for appropriate treatment.

HIV/AIDS

HIV infection is highly prevalent among people suffering from severe mental illness such as schizophrenia. The incidence of HIV/AIDS in patients with schizophrenia is estimated to be 4% to 23%, compared with 0.6% in the general population.22 Risk factors associated with a higher incidence of HIV/AIDS in patients with schizophrenia are lack of knowledge about contracting HIV, unsafe sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality, homelessness, and IV drug use.22

Managing HIV/AIDS.

- Educate the patient and family about risk factors associated with contracting HIV/AIDS.

- Educate patients about safe sex practices.

- All patients with schizophrenia should be screened for HIV because there is 10-fold higher HIV prevalence in schizophrenia compared with the general population.

- When HIV infection is diagnosed, facilitate referral to a HIV or infectious disease specialist for treatment.

- Educate the patient in whom HIV/AIDS has been diagnosed about the importance of (1) adherence to his (her) HIV medication regimen and (2) follow-up visits with an infectious disease practitioner and appropriate laboratory tests.

- Educate the patient’s family and significant other about the illness.

- Screen for and treat substance use.

- At each visit, inquire about the patient’s adherence to HIV medical therapy, viral load, and CD4 cell count.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Patients with schizophrenia are more likely to suffer from respiratory disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma, compared with the general population.23 Smoking is a major risk factor for COPD. In a study by Dickerson et al,24 64% of people with schizophrenia were current smokers, compared with 19% of those without mental illness.

A high rate of smoking rate among people with schizophrenia suggests a “self-medication” hypothesis: That is, stimulation of CNS nicotinic cholinergic receptors treats the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and overcomes the dopamine blocking effects of antipsychotics.25 Among SGAs, only clozapine has a substantial body of evidence to support its association with decreased smoking behavior.

Managing COPD.

- Educate the patient and family about risk factors associated with COPD and smoking.

- Screen for tobacco use at each visit; try to increase motivation to quit smoking.

- Educate the patients and family about the value and availability of smoking cessation programs.

- Prescribe medication to help with smoking cessation when needed. Bupropion and varenicline have been shown to be effective in patients with schizophrenia; nicotine replacement therapies are safe and can be helpful.

- When treating a patient who is in the process of quitting, encourage and help him to maintain his commitment and enlist support from his family.

- Refer to an appropriate medical provider (primary care provider or pulmonologist) for a patient with an established or suspected diagnosis of COPD.

Cancer

Since 1909, when the Board of Control of the Commissioners in Lunacy for England and Wales noted the possibility of a decreased incidence in cancer among psychiatric patients, this connection has been a matter of controversy.26 Subsequent research has been equivocal; the prevalence of cancer has been reported to be either increased, similar, or decreased compared with the general population.26-28 Risk factors for cancer, including smoking, obesity, poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, and hyperprolactinemia, are more common among patients with schizophrenia.

Genetic factors and a possible protective effect from antipsychotics have been cited as potential causes of decreased prevalence. Clozapine is associated with an increased risk of leukemia. No conclusion can be drawn about the overall prevalence of cancer in schizophrenia.

Managing cancer in a patient with schizophrenia, however, poses a significant challenge29; he might lack capacity to make decisions about cancer treatment. The patient—or his surrogate decision-makers—need to carefully weigh current quality of life against potential benefits of treatment and risks of side effects. Adherence to complex, often toxic, therapies can be challenging for the patient with psychosis. Successful cancer treatment often requires close collaboration between the cancer treatment team and the patient’s support system, including the treating psychiatrist and case management teams.

Bottom Line

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk of developing comorbid medical

conditions because of the illness itself, lifestyle behaviors, genetics, and adverse