User login

PPROM: New strategies for expectant management

- A large, prospective, randomized, controlled trial clearly showed that antibiotics decrease neonatal morbidities and prolong the interval between rupture of membranes and delivery.

- Avoid digital cervical examination during testing for rupture of membranes because it may hasten delivery and increase neonatal morbidity.

- Consider giving magnesium sulfate and corticosteroids to patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes at or beyond 23 weeks, provided there is no evidence of infection. After 32 weeks, deliver the infant if either intraamniotic infection or fetal lung maturity is present.

- At delivery, amnioinfusion decreases variable decelerations and improves pH when clinically indicated.

The outlook for preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) has improved considerably since a landmark study showed clear benefits of antibiotics.

Previously, approximately 80% of women with PPROM experienced spontaneous labor within 48 hours with expectant management.

We now know that infection is a major cause of PPROM and that antibiotic therapy decreases neonatal morbidity and increases the interval from rupture of membranes to delivery. These benefits are most evident at early gestational ages.

This article reviews newer studies, as well as that breakthrough 1997 study, and their implications for diagnosis and treatment, including optimal drug regimens. Recommendations for 4 special situations are also discussed:

- presence of cerclage,

- herpes simplex infection,

- bleeding, and

- outpatient management.

Despite progress, research is still needed. For example, because much of our information about clinical interventions for PPROM, such as corticosteroid therapy and use of tocolytics, predates the use of antibiotics, many earlier studies need to be repeated.

A variety of methods confirm the diagnosis

Approximately 90% of patients with PPROM report nonurinary fluid leaking from the vagina.1,2 Nevertheless, a history of leaking fluid should be confirmed by examination.

Nitrazine paper test

The most common way to diagnose rupture of membranes involves exposing nitrazine paper to the leaking fluid. If the fluid is alkaline, the paper will turn bright blue.

However, seminal fluid, urine, and blood can also turn nitrazine paper blue. Therefore, a confirmatory method should be used with nitrazine paper testing.

Fern pattern test

When amniotic fluid proteins are allowed to dry and then examined under a microscope, they will exhibit a “fern” pattern.

The combination of nitrazine paper and the fern test has a specificity of over 90%.

Avoid digital cervical examination

Digital examination during testing may diminish latency (the period from rupture of membranes to delivery) and increase neonatal morbidity.3

Testing at early gestational ages

Occasionally, PPROM occurs early in the middle trimester. At such early gestations, amniotic fluid may not fern or produce the classic blue color when exposed to nitrazine paper.

Other tests may be used, however:

- Ultrasound can help in evaluating the quantity of amniotic fluid.

- Indigo carmine dye can be placed in the amniotic cavity, with a tampon inserted in the vagina. If the tampon turns blue when the patient ambulates, rupture of membranes is confirmed.

- Alpha-fetoprotein and human choriogonadotropin. When alpha-fetoprotein is present and human choriogonadotropin is highly concentrated in amniotic fluid, ruptured membranes are confirmed.4

Fortunately, a large majority of patients can be diagnosed using clinical history, nitrazine paper, and the fern pattern test.

Definition

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) is ruptured membranes before the 37th week of gestation.

Incidence

PPROM complicates 3% to 4.5% of all pregnancies and is responsible for 30% to 40% of all preterm births.26 This high incidence makes it a major cause of premature birth in the United States.

Predisposing factors

African-American women appear to have a higher incidence of PPROM than Caucasian women.27

Smoking is strongly correlated with PPROM,28 as it is with most poor perinatal outcomes.

Nutritional deficiencies in hydroxyproline, vitamin C, copper, and zinc also are linked.26

The precise cause is unknown

Ascending infection29 and uterine bleeding1 are both strongly correlated with PPROM. An incompetent cervix is also thought to play a role, as are conditions involving connective tissue abnormalities, such as those found in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Unfortunately, we have yet to identify a factor or factors that could be linked to a specific cause for any given patient. Such knowledge would enable us to abandon empiric treatment in favor of more specific management guidelines.

Infection plays a major role in most cases

Bacteria in the vagina ascend through the intracervical canal and establish subclinical infection in the lower uterine segment.29

This activates macrophages and polymorphoneutrophils as a host defense mechanism. Macrophages release interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosing factors, while lysis of polymorphoneutrophils triggers the release of proteolytic enzymes.

These enzymes not only destroy the invasive microorganisms, but are capable of damaging the chorion and amnion, increasing the likelihood of ruptured membranes.

As we come to understand these mechanisms more fully, we should be able to tailor therapy to specific etiologies, thereby optimizing outcomes.30

Gestational age determines management

The number 1 factor determining management is gestational age.

Before 23 weeks, the pregnancy is considered previable

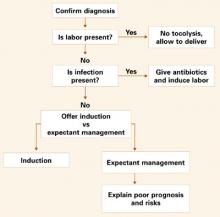

Counsel these patients about the risk of infection, the prognosis of extreme prematurity, and the generally poor outcome of these pregnancies, which can involve pulmonary hypoplasia secondary to severe oligohydramnios (FIGURE 1).

Induction of labor is an option to terminate the pregnancy. If the patient chooses expectant management, monitor her closely for infection.4 Outpatient management is acceptable for the highly compliant patient. However, once fetal viability is attained, readmit the patient to monitor maternal and fetal well-being.

Between 23 and 32 weeks

Treat these women expectantly in the hospital unless there is evidence of infection or fetal compromise. Management includes intravenous antibiotic therapy and corticosteroids, as recommended by the National Institutes of Health (FIGURE 2).5

Although it is controversial, consider magnesium sulfate tocolytic therapy if the patient is actively contracting with no evidence of infection.6

Some authorities recommend amniocentesis (at any gestational age) to rule out infection prior to expectant management, while others consider the appropriate use of clinical parameters to be adequate.6

After monitoring the patient in the labor suite for 24 to 48 hours, transfer her to the antenatal ward, if she is stable, for frequent fetal surveillance and maternal evaluation. Continue to evaluate her for signs of intraamniotic infection such as fever, uterine tenderness, and foulsmelling discharge.

Many authorities recommend daily nonstress testing or biophysical profiles to evaluate fetal well-being.7

Between 32 and 34 weeks

Management for this gestational age range is the most controversial (FIGURE 3). Mercer et al8 demonstrated that expectant management is harmful to the neonate if fetal lung maturity is present. Most experts contend that some method of fetal lung assessment should be undertaken. The most effective method is sampling amniotic fluid by amniocentesis. Not only can fetal lung maturity be determined, but the fluid can be analyzed for evidence of infection using the Gram stain, glucose level, and white blood cell count.

When an amniocentesis site is unavailable, consider assessing fetal lung maturity via a pooled amniotic fluid sample from the vagina.9 Deliver the infant if either intraamniotic infection or fetal lung maturity is present.

If there is no evidence of fetal lung maturity, expectant management is usually recommended for pregnancies between 32 and 34 weeks.

In a recent survey of maternal-fetal medicine specialists in the United States, 58% recommended delivery at 34 weeks of gestation.10

For patients who are at less than 34 weeks upon presentation—or to be treated expectantly—consider giving antibiotics, corticosteroids, and tocolysis during the first 48 hours.

FIGURE 1 Managing premature rupture of membranes: Less than 23 weeks’ gestation

FIGURE 2 Managing premature rupture of membranes: 23 to <32 weeks’ gestation

The new standard of care: antibiotic therapy

In the 1980s, several studies suggested antibiotics were beneficial for PPROM patients.11 More recently, the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Network published the results of a large, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial clearly demonstrating that antibiotics prolong the latency period and decrease neonatal morbidities (see “Antibiotics in PPROM improve outcomes in Maternal-Fetal Medicine Network study”).12

Limited- versus broad-spectrum antibiotics

Although antibiotic therapy is now the standard of care for patients with PPROM, it remains unclear which antibiotic is best. Some researchers have recommended limited-spectrum antibiotics, while others prefer a broader-spectrum approach.13 Several recent studies14 have suggested that erythromycin is effective for eradicating Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma and beneficial for the neonate.

Optimal duration of antibiotic therapy is unclear

Most early studies advocated standard treatment from the time of ruptured membranes until delivery, while others recommended 7 to 10 days of therapy. Several recent trials15 have found 3 days of therapy to be equivalent to 7 days. However, these studies lack sufficient power to warrant a shorter duration of therapy at this time.

Numerous small, prospective, randomized trials comparing antibiotics with placebo have demonstrated prolonged latency (period from rupture of membranes to delivery) in the women with preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) who were given antibiotics.

However, these studies lacked sufficient power to establish a decrease in neonatal morbidity with antibiotics, although a meta-analysis by Mercer and Arheart31 suggested such a decrease existed.

The breakthrough trial

Finally, in 1997, the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Network of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development published a study large enough to definitively answer the question.12

A significant decrease in morbidity and mortality

Since these findings were published, controversy has shifted to the choice of antibiotics and the length and route of administration.

In this study, 614 women between 24 and 32 weeks of gestation with confirmed PPROM were randomized to intravenous ampicillin (2 g every 6 hours) and erythromycin (250 mg every 6 hours) for 48 hours followed by oral amoxicillin (250 mg every 8 hours) and erythromycin base (333 mg every 8 hours) for 5 days, or placebo. None of the women had received corticosteroids for fetal maturation or antibiotic treatment within 1 week of randomization.

In the study group, the composite primary outcome of interest decreased significantly—pregnancies with at least 1 of the following: fetal or infant mortality, respiratory distress, severe intraventricular hemorrhage, stage 2 or 3 necrotizing enterocolitis, or sepsis within 72 hours of birth.

Practice recommendation

I use ampicillin (2 g IV every 6 hours) and azithromycin (500 mg orally or IV on day 1 followed by 250 mg every day for 4 days) because data from the ORACLE trial14 suggested an increased incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. I also treat patients for 7 full days, even though preliminary data suggests 3 days may be adequate.15

More trials ahead

Expect to see many more randomized trials seeking to establish the best antibiotic, route of administration, and length of treatment.

Corticosteroids beneficial if infection is treated

In 1998, the National Institutes of Health issued a Consensus Statement5 recommending corticosteroid therapy to accelerate fetal lung maturity and decrease neonatal morbidity in PPROM patients. Many authorities questioned the wisdom of this recommendation, since earlier studies had suggested an increased risk of maternal morbidity when corticosteroids are given as therapy for PPROM.16 However, these early studies did not use antibiotics to treat infection—the primary cause of PPROM—and many patients underwent digital vaginal exams, which probably contributed to unfavorable maternal and neonatal outcomes.

I recently began treating PPROM patients with antibiotics for 12 hours prior to administering corticosteroids and noted a considerable benefit for steroid therapy.17 I therefore recommend that PPROM patients who are treated expectantly receive corticosteroids unless there is evidence of an infection.

Tocolysis: jury still out

The use of tocolytics also is controversial. Many original studies reported no overall benefit and a significant increase in maternal morbidity when tocolytic therapy was given for ruptured membranes.18 However, many patients in these trials underwent digital vaginal exams and were not given antibiotics, and many received corticosteroids.

In my practice, I give magnesium sulfate and corticosteroids for the first 48 hours to women at or beyond 23 weeks’ gestation, provided there is no evidence of infection.19 However, additional data is needed before this management protocol can be considered the standard of care.

Assess fetal well-being frequently

Initial recommendations for antepartum testing were based on the high perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with PPROM. Nonstress testing was the foundation of therapy, and many authorities advocated daily nonstress testing even in the absence of definitive proof of its benefit.4

In the late 1980s, Vintzileos20 and other experts recommended daily biophysical profiles, suggesting that this strategy could identify patients with subclinical infection.

Daily biophysical profiles: No benefit beyond that of daily nonstress test

My colleagues and I7 conducted the only reported prospective, randomized trial comparing daily biophysical profiles to daily nonstress testing with backup biophysical profiles for abnormalities. We concluded that daily biophysical profiles provide no benefit beyond that achieved with daily nonstress testing. Whether a less intense testing protocol would produce the same benefit is unclear.

Important to recognize high risk of poor perinatal outcome

The important point in managing patients with PPROM is recognizing the high risk of poor perinatal outcome. For this reason, frequent evaluation of fetal well-being is an essential element of any management plan.

Determine mode of delivery as usual, but monitor fetus

In PPROM cases, the fetus often is intolerant of labor, primarily because of oligohydramnios and subclinical infection. For this reason, monitor the fetus very closely in the intrapartum period. Amnioinfusion decreases variable decelerations and improves pH in these patients and should be considered when it is clinically indicated.21

Determine the mode of delivery using routine obstetrical indications. Deliver viable breech infants by cesarean section.

Few data exist on the benefit of cesarean for the very premature neonate; use of routine obstetrical indicators is advisable.

Special situations

Four conditions may affect management of the patient with PPROM:

Cerclage in place

Numerous early studies suggested that this foreign body is a focus of infection and recommended removal. However, recent reports have not substantiated these findings.22 A large, multicenter, prospective, randomized trial is underway, which compares expectant management with cerclage removal when membranes rupture. It should provide a definitive answer.

Herpes simplex infection

If the patient with PPROM has a clinical outbreak of herpes simplex virus, weigh the risk of early delivery against the risk of herpes simplex infection. Major et al23 compiled a case series showing that infants did not become infected with herpes simplex virus when women were managed expectantly. Still, consider prophylactic therapy with antiviral agents in expectantly managed patients. At later gestational ages, most experts recommend delivery.

Bleeding

Placental abruptions occur in about 5% of PPROM pregnancies.24 Some authorities contend that the cause of abruption is placental shearing following leakage of amniotic fluid and decreased intrauterine volume. However, bleeding is rarely substantial enough to warrant delivery. Even so, monitor women with active bleeding in the labor suite, remaining vigilant for evidence of fetal compromise.

Outpatient management

Only 1 study has evaluated outpatient management of women with PPROM.25 Until more definitive information is available, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that outpatient management be limited to approved study protocols.6

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Iams JD, Stilson R, Johnson FF, et al. Symptoms that precede preterm labor and preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:486.-

2. Friedman ML, McElin TW. Diagnosis of ruptured fetal membranes: Clinical study and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;104:544-550.

3. Lewis DF, Major CA, Towers CV, et al. Effects of digital vaginal examinations on latency period in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:630-634.

4. Garite TJ. Management of premature rupture of membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):837-847.

5. National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: effect of corticosteroids for fetal maturation on perinatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:246-252.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin #1: Premature Rupture of Membranes. Washington, DC: ACOG; June 1998.

7. Lewis DF, Adair CD, Weeks JW, et al. A randomized clinical trial of nonstress test versus biophysical profile in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1495-1499.

8. Mercer BM, Crocker LG, Boe NM, et al. Induction versus expectant management in premature rupture of the membranes with mature amniotic fluid at 32 to 36 weeks: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:775-782.

9. Lewis DF, Towers CV, Major CA, et al. Use of Amniostat-FLM in detecting the presence of phosphatidylglycerol in vaginal pool samples in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1139-1143.

10. Healy AJ, Veille J-C, Sciscione A, et al. The timing of elective delivery in preterm rupture of the membranes: a survey of members of the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(5):1479-1481.

11. Amon E, Lewis SV, Sibai BM, et al. Ampicillin prophylaxis in preterm premature rupture of the membranes: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;159:539.-

12. Mercer B, Miodovnik M, Thurnau G, et al. Antibiotic therapy for reduction of infant morbidity after preterm premature rupture of the membranes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278:989-995.

13. Lewis DF, Fontenot MT, Brooks GG, et al. Latency period after preterm premature rupture of membranes: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study comparing ampicillin and ampicillin-sulbactum. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:392-395.

14. Kenyon SL, Taylor DJ, Tarnow-Mordi W. Oracle Collaborative Group. Broad spectrum antibiotics for preterm, prelabor rupture of fetal membranes: the ORACLE I randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;357:979-988.

15. Lewis DF, Adair CD, Robichaux AG, et al. Antibiotic therapy in preterm premature rupture of membranes: are seven days necessary? A preliminary, randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1413-1416;discussion 1416-1417.

16. Vidaeff AC, Ramin SM, Gilstrap III LC. Antenatal corticosteroids in women with preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):797-805.

17. Lewis DF, Brody K, Edwards MS, Brouillette RM. Preterm premature ruptured membranes: a randomized trial of steroids after treatment with antibiotics. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:801-805.

18. Garite TJ, Keegan KA, Freeman RK, et al. A randomized trial of ritodrine tocolysis versus expectant management in patients with premature rupture of membranes at 25 to 30 weeks of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:388-393.

19. Fontenot T, Lewis DF. Tocolytic therapy with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):787-796.

20. Vintzileos AM, Campbell WA, Nochimson DJ, et al. The fetal biophysical profile in patients with premature rupture of the membranes: an early predictor of fetal infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152:510.-

21. Nageotte MP, Freeman RK, Garite TJ, et al. Prophylactic intrapartum amnioinfusion in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:557.-

22. Lee RM, Major CA. Controversial and special situations in the management of preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):877-884.

23. Major CA, Towers CV, Lewis DF, Garite TJ. Expectant management of preterm premature rupture of membranes complicated by active recurrent genital herpes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1551-1554.

24. Major CA, de Veciana M, Lewis DF, Morgan MA. Preterm premature rupture of membranes and abruptio placentae: is there an association between these pregnancy complications? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:672-676.

25. Carlan SJ, O’Brien WF, Parsons MT, et al. Preterm premature rupture of membranes: a randomized study of home versus hospital management. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:61-64.

26. Lee T, Silver H. Etiology and epidemiology of preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):721-734.

27. Savitz DA, Blackmore CA, Thorp JM. Epidemiologic characteristics of preterm delivery: etiologic heterogeneity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:467.-

28. Shiono PH, Klebanoff MA, Rhoads GG. Smoking and drinking during pregnancy: their effects on preterm birth. JAMA. 1986;255:82.-

29. Romero R, Ghidini A, Mazor M, et al. Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in premature rupture of membranes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1991;34:769.-

30. Asrat T. Intra-amniotic infection in patients with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes: pathophysiology, detection, and management. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):735-751.

31. Mercer B, Arheart K. Antimicrobial therapy in expectant management of preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Lancet. 1995;346:1271-1279.

- A large, prospective, randomized, controlled trial clearly showed that antibiotics decrease neonatal morbidities and prolong the interval between rupture of membranes and delivery.

- Avoid digital cervical examination during testing for rupture of membranes because it may hasten delivery and increase neonatal morbidity.

- Consider giving magnesium sulfate and corticosteroids to patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes at or beyond 23 weeks, provided there is no evidence of infection. After 32 weeks, deliver the infant if either intraamniotic infection or fetal lung maturity is present.

- At delivery, amnioinfusion decreases variable decelerations and improves pH when clinically indicated.

The outlook for preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) has improved considerably since a landmark study showed clear benefits of antibiotics.

Previously, approximately 80% of women with PPROM experienced spontaneous labor within 48 hours with expectant management.

We now know that infection is a major cause of PPROM and that antibiotic therapy decreases neonatal morbidity and increases the interval from rupture of membranes to delivery. These benefits are most evident at early gestational ages.

This article reviews newer studies, as well as that breakthrough 1997 study, and their implications for diagnosis and treatment, including optimal drug regimens. Recommendations for 4 special situations are also discussed:

- presence of cerclage,

- herpes simplex infection,

- bleeding, and

- outpatient management.

Despite progress, research is still needed. For example, because much of our information about clinical interventions for PPROM, such as corticosteroid therapy and use of tocolytics, predates the use of antibiotics, many earlier studies need to be repeated.

A variety of methods confirm the diagnosis

Approximately 90% of patients with PPROM report nonurinary fluid leaking from the vagina.1,2 Nevertheless, a history of leaking fluid should be confirmed by examination.

Nitrazine paper test

The most common way to diagnose rupture of membranes involves exposing nitrazine paper to the leaking fluid. If the fluid is alkaline, the paper will turn bright blue.

However, seminal fluid, urine, and blood can also turn nitrazine paper blue. Therefore, a confirmatory method should be used with nitrazine paper testing.

Fern pattern test

When amniotic fluid proteins are allowed to dry and then examined under a microscope, they will exhibit a “fern” pattern.

The combination of nitrazine paper and the fern test has a specificity of over 90%.

Avoid digital cervical examination

Digital examination during testing may diminish latency (the period from rupture of membranes to delivery) and increase neonatal morbidity.3

Testing at early gestational ages

Occasionally, PPROM occurs early in the middle trimester. At such early gestations, amniotic fluid may not fern or produce the classic blue color when exposed to nitrazine paper.

Other tests may be used, however:

- Ultrasound can help in evaluating the quantity of amniotic fluid.

- Indigo carmine dye can be placed in the amniotic cavity, with a tampon inserted in the vagina. If the tampon turns blue when the patient ambulates, rupture of membranes is confirmed.

- Alpha-fetoprotein and human choriogonadotropin. When alpha-fetoprotein is present and human choriogonadotropin is highly concentrated in amniotic fluid, ruptured membranes are confirmed.4

Fortunately, a large majority of patients can be diagnosed using clinical history, nitrazine paper, and the fern pattern test.

Definition

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) is ruptured membranes before the 37th week of gestation.

Incidence

PPROM complicates 3% to 4.5% of all pregnancies and is responsible for 30% to 40% of all preterm births.26 This high incidence makes it a major cause of premature birth in the United States.

Predisposing factors

African-American women appear to have a higher incidence of PPROM than Caucasian women.27

Smoking is strongly correlated with PPROM,28 as it is with most poor perinatal outcomes.

Nutritional deficiencies in hydroxyproline, vitamin C, copper, and zinc also are linked.26

The precise cause is unknown

Ascending infection29 and uterine bleeding1 are both strongly correlated with PPROM. An incompetent cervix is also thought to play a role, as are conditions involving connective tissue abnormalities, such as those found in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Unfortunately, we have yet to identify a factor or factors that could be linked to a specific cause for any given patient. Such knowledge would enable us to abandon empiric treatment in favor of more specific management guidelines.

Infection plays a major role in most cases

Bacteria in the vagina ascend through the intracervical canal and establish subclinical infection in the lower uterine segment.29

This activates macrophages and polymorphoneutrophils as a host defense mechanism. Macrophages release interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosing factors, while lysis of polymorphoneutrophils triggers the release of proteolytic enzymes.

These enzymes not only destroy the invasive microorganisms, but are capable of damaging the chorion and amnion, increasing the likelihood of ruptured membranes.

As we come to understand these mechanisms more fully, we should be able to tailor therapy to specific etiologies, thereby optimizing outcomes.30

Gestational age determines management

The number 1 factor determining management is gestational age.

Before 23 weeks, the pregnancy is considered previable

Counsel these patients about the risk of infection, the prognosis of extreme prematurity, and the generally poor outcome of these pregnancies, which can involve pulmonary hypoplasia secondary to severe oligohydramnios (FIGURE 1).

Induction of labor is an option to terminate the pregnancy. If the patient chooses expectant management, monitor her closely for infection.4 Outpatient management is acceptable for the highly compliant patient. However, once fetal viability is attained, readmit the patient to monitor maternal and fetal well-being.

Between 23 and 32 weeks

Treat these women expectantly in the hospital unless there is evidence of infection or fetal compromise. Management includes intravenous antibiotic therapy and corticosteroids, as recommended by the National Institutes of Health (FIGURE 2).5

Although it is controversial, consider magnesium sulfate tocolytic therapy if the patient is actively contracting with no evidence of infection.6

Some authorities recommend amniocentesis (at any gestational age) to rule out infection prior to expectant management, while others consider the appropriate use of clinical parameters to be adequate.6

After monitoring the patient in the labor suite for 24 to 48 hours, transfer her to the antenatal ward, if she is stable, for frequent fetal surveillance and maternal evaluation. Continue to evaluate her for signs of intraamniotic infection such as fever, uterine tenderness, and foulsmelling discharge.

Many authorities recommend daily nonstress testing or biophysical profiles to evaluate fetal well-being.7

Between 32 and 34 weeks

Management for this gestational age range is the most controversial (FIGURE 3). Mercer et al8 demonstrated that expectant management is harmful to the neonate if fetal lung maturity is present. Most experts contend that some method of fetal lung assessment should be undertaken. The most effective method is sampling amniotic fluid by amniocentesis. Not only can fetal lung maturity be determined, but the fluid can be analyzed for evidence of infection using the Gram stain, glucose level, and white blood cell count.

When an amniocentesis site is unavailable, consider assessing fetal lung maturity via a pooled amniotic fluid sample from the vagina.9 Deliver the infant if either intraamniotic infection or fetal lung maturity is present.

If there is no evidence of fetal lung maturity, expectant management is usually recommended for pregnancies between 32 and 34 weeks.

In a recent survey of maternal-fetal medicine specialists in the United States, 58% recommended delivery at 34 weeks of gestation.10

For patients who are at less than 34 weeks upon presentation—or to be treated expectantly—consider giving antibiotics, corticosteroids, and tocolysis during the first 48 hours.

FIGURE 1 Managing premature rupture of membranes: Less than 23 weeks’ gestation

FIGURE 2 Managing premature rupture of membranes: 23 to <32 weeks’ gestation

The new standard of care: antibiotic therapy

In the 1980s, several studies suggested antibiotics were beneficial for PPROM patients.11 More recently, the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Network published the results of a large, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial clearly demonstrating that antibiotics prolong the latency period and decrease neonatal morbidities (see “Antibiotics in PPROM improve outcomes in Maternal-Fetal Medicine Network study”).12

Limited- versus broad-spectrum antibiotics

Although antibiotic therapy is now the standard of care for patients with PPROM, it remains unclear which antibiotic is best. Some researchers have recommended limited-spectrum antibiotics, while others prefer a broader-spectrum approach.13 Several recent studies14 have suggested that erythromycin is effective for eradicating Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma and beneficial for the neonate.

Optimal duration of antibiotic therapy is unclear

Most early studies advocated standard treatment from the time of ruptured membranes until delivery, while others recommended 7 to 10 days of therapy. Several recent trials15 have found 3 days of therapy to be equivalent to 7 days. However, these studies lack sufficient power to warrant a shorter duration of therapy at this time.

Numerous small, prospective, randomized trials comparing antibiotics with placebo have demonstrated prolonged latency (period from rupture of membranes to delivery) in the women with preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) who were given antibiotics.

However, these studies lacked sufficient power to establish a decrease in neonatal morbidity with antibiotics, although a meta-analysis by Mercer and Arheart31 suggested such a decrease existed.

The breakthrough trial

Finally, in 1997, the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Network of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development published a study large enough to definitively answer the question.12

A significant decrease in morbidity and mortality

Since these findings were published, controversy has shifted to the choice of antibiotics and the length and route of administration.

In this study, 614 women between 24 and 32 weeks of gestation with confirmed PPROM were randomized to intravenous ampicillin (2 g every 6 hours) and erythromycin (250 mg every 6 hours) for 48 hours followed by oral amoxicillin (250 mg every 8 hours) and erythromycin base (333 mg every 8 hours) for 5 days, or placebo. None of the women had received corticosteroids for fetal maturation or antibiotic treatment within 1 week of randomization.

In the study group, the composite primary outcome of interest decreased significantly—pregnancies with at least 1 of the following: fetal or infant mortality, respiratory distress, severe intraventricular hemorrhage, stage 2 or 3 necrotizing enterocolitis, or sepsis within 72 hours of birth.

Practice recommendation

I use ampicillin (2 g IV every 6 hours) and azithromycin (500 mg orally or IV on day 1 followed by 250 mg every day for 4 days) because data from the ORACLE trial14 suggested an increased incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. I also treat patients for 7 full days, even though preliminary data suggests 3 days may be adequate.15

More trials ahead

Expect to see many more randomized trials seeking to establish the best antibiotic, route of administration, and length of treatment.

Corticosteroids beneficial if infection is treated

In 1998, the National Institutes of Health issued a Consensus Statement5 recommending corticosteroid therapy to accelerate fetal lung maturity and decrease neonatal morbidity in PPROM patients. Many authorities questioned the wisdom of this recommendation, since earlier studies had suggested an increased risk of maternal morbidity when corticosteroids are given as therapy for PPROM.16 However, these early studies did not use antibiotics to treat infection—the primary cause of PPROM—and many patients underwent digital vaginal exams, which probably contributed to unfavorable maternal and neonatal outcomes.

I recently began treating PPROM patients with antibiotics for 12 hours prior to administering corticosteroids and noted a considerable benefit for steroid therapy.17 I therefore recommend that PPROM patients who are treated expectantly receive corticosteroids unless there is evidence of an infection.

Tocolysis: jury still out

The use of tocolytics also is controversial. Many original studies reported no overall benefit and a significant increase in maternal morbidity when tocolytic therapy was given for ruptured membranes.18 However, many patients in these trials underwent digital vaginal exams and were not given antibiotics, and many received corticosteroids.

In my practice, I give magnesium sulfate and corticosteroids for the first 48 hours to women at or beyond 23 weeks’ gestation, provided there is no evidence of infection.19 However, additional data is needed before this management protocol can be considered the standard of care.

Assess fetal well-being frequently

Initial recommendations for antepartum testing were based on the high perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with PPROM. Nonstress testing was the foundation of therapy, and many authorities advocated daily nonstress testing even in the absence of definitive proof of its benefit.4

In the late 1980s, Vintzileos20 and other experts recommended daily biophysical profiles, suggesting that this strategy could identify patients with subclinical infection.

Daily biophysical profiles: No benefit beyond that of daily nonstress test

My colleagues and I7 conducted the only reported prospective, randomized trial comparing daily biophysical profiles to daily nonstress testing with backup biophysical profiles for abnormalities. We concluded that daily biophysical profiles provide no benefit beyond that achieved with daily nonstress testing. Whether a less intense testing protocol would produce the same benefit is unclear.

Important to recognize high risk of poor perinatal outcome

The important point in managing patients with PPROM is recognizing the high risk of poor perinatal outcome. For this reason, frequent evaluation of fetal well-being is an essential element of any management plan.

Determine mode of delivery as usual, but monitor fetus

In PPROM cases, the fetus often is intolerant of labor, primarily because of oligohydramnios and subclinical infection. For this reason, monitor the fetus very closely in the intrapartum period. Amnioinfusion decreases variable decelerations and improves pH in these patients and should be considered when it is clinically indicated.21

Determine the mode of delivery using routine obstetrical indications. Deliver viable breech infants by cesarean section.

Few data exist on the benefit of cesarean for the very premature neonate; use of routine obstetrical indicators is advisable.

Special situations

Four conditions may affect management of the patient with PPROM:

Cerclage in place

Numerous early studies suggested that this foreign body is a focus of infection and recommended removal. However, recent reports have not substantiated these findings.22 A large, multicenter, prospective, randomized trial is underway, which compares expectant management with cerclage removal when membranes rupture. It should provide a definitive answer.

Herpes simplex infection

If the patient with PPROM has a clinical outbreak of herpes simplex virus, weigh the risk of early delivery against the risk of herpes simplex infection. Major et al23 compiled a case series showing that infants did not become infected with herpes simplex virus when women were managed expectantly. Still, consider prophylactic therapy with antiviral agents in expectantly managed patients. At later gestational ages, most experts recommend delivery.

Bleeding

Placental abruptions occur in about 5% of PPROM pregnancies.24 Some authorities contend that the cause of abruption is placental shearing following leakage of amniotic fluid and decreased intrauterine volume. However, bleeding is rarely substantial enough to warrant delivery. Even so, monitor women with active bleeding in the labor suite, remaining vigilant for evidence of fetal compromise.

Outpatient management

Only 1 study has evaluated outpatient management of women with PPROM.25 Until more definitive information is available, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that outpatient management be limited to approved study protocols.6

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- A large, prospective, randomized, controlled trial clearly showed that antibiotics decrease neonatal morbidities and prolong the interval between rupture of membranes and delivery.

- Avoid digital cervical examination during testing for rupture of membranes because it may hasten delivery and increase neonatal morbidity.

- Consider giving magnesium sulfate and corticosteroids to patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes at or beyond 23 weeks, provided there is no evidence of infection. After 32 weeks, deliver the infant if either intraamniotic infection or fetal lung maturity is present.

- At delivery, amnioinfusion decreases variable decelerations and improves pH when clinically indicated.

The outlook for preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) has improved considerably since a landmark study showed clear benefits of antibiotics.

Previously, approximately 80% of women with PPROM experienced spontaneous labor within 48 hours with expectant management.

We now know that infection is a major cause of PPROM and that antibiotic therapy decreases neonatal morbidity and increases the interval from rupture of membranes to delivery. These benefits are most evident at early gestational ages.

This article reviews newer studies, as well as that breakthrough 1997 study, and their implications for diagnosis and treatment, including optimal drug regimens. Recommendations for 4 special situations are also discussed:

- presence of cerclage,

- herpes simplex infection,

- bleeding, and

- outpatient management.

Despite progress, research is still needed. For example, because much of our information about clinical interventions for PPROM, such as corticosteroid therapy and use of tocolytics, predates the use of antibiotics, many earlier studies need to be repeated.

A variety of methods confirm the diagnosis

Approximately 90% of patients with PPROM report nonurinary fluid leaking from the vagina.1,2 Nevertheless, a history of leaking fluid should be confirmed by examination.

Nitrazine paper test

The most common way to diagnose rupture of membranes involves exposing nitrazine paper to the leaking fluid. If the fluid is alkaline, the paper will turn bright blue.

However, seminal fluid, urine, and blood can also turn nitrazine paper blue. Therefore, a confirmatory method should be used with nitrazine paper testing.

Fern pattern test

When amniotic fluid proteins are allowed to dry and then examined under a microscope, they will exhibit a “fern” pattern.

The combination of nitrazine paper and the fern test has a specificity of over 90%.

Avoid digital cervical examination

Digital examination during testing may diminish latency (the period from rupture of membranes to delivery) and increase neonatal morbidity.3

Testing at early gestational ages

Occasionally, PPROM occurs early in the middle trimester. At such early gestations, amniotic fluid may not fern or produce the classic blue color when exposed to nitrazine paper.

Other tests may be used, however:

- Ultrasound can help in evaluating the quantity of amniotic fluid.

- Indigo carmine dye can be placed in the amniotic cavity, with a tampon inserted in the vagina. If the tampon turns blue when the patient ambulates, rupture of membranes is confirmed.

- Alpha-fetoprotein and human choriogonadotropin. When alpha-fetoprotein is present and human choriogonadotropin is highly concentrated in amniotic fluid, ruptured membranes are confirmed.4

Fortunately, a large majority of patients can be diagnosed using clinical history, nitrazine paper, and the fern pattern test.

Definition

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) is ruptured membranes before the 37th week of gestation.

Incidence

PPROM complicates 3% to 4.5% of all pregnancies and is responsible for 30% to 40% of all preterm births.26 This high incidence makes it a major cause of premature birth in the United States.

Predisposing factors

African-American women appear to have a higher incidence of PPROM than Caucasian women.27

Smoking is strongly correlated with PPROM,28 as it is with most poor perinatal outcomes.

Nutritional deficiencies in hydroxyproline, vitamin C, copper, and zinc also are linked.26

The precise cause is unknown

Ascending infection29 and uterine bleeding1 are both strongly correlated with PPROM. An incompetent cervix is also thought to play a role, as are conditions involving connective tissue abnormalities, such as those found in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Unfortunately, we have yet to identify a factor or factors that could be linked to a specific cause for any given patient. Such knowledge would enable us to abandon empiric treatment in favor of more specific management guidelines.

Infection plays a major role in most cases

Bacteria in the vagina ascend through the intracervical canal and establish subclinical infection in the lower uterine segment.29

This activates macrophages and polymorphoneutrophils as a host defense mechanism. Macrophages release interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosing factors, while lysis of polymorphoneutrophils triggers the release of proteolytic enzymes.

These enzymes not only destroy the invasive microorganisms, but are capable of damaging the chorion and amnion, increasing the likelihood of ruptured membranes.

As we come to understand these mechanisms more fully, we should be able to tailor therapy to specific etiologies, thereby optimizing outcomes.30

Gestational age determines management

The number 1 factor determining management is gestational age.

Before 23 weeks, the pregnancy is considered previable

Counsel these patients about the risk of infection, the prognosis of extreme prematurity, and the generally poor outcome of these pregnancies, which can involve pulmonary hypoplasia secondary to severe oligohydramnios (FIGURE 1).

Induction of labor is an option to terminate the pregnancy. If the patient chooses expectant management, monitor her closely for infection.4 Outpatient management is acceptable for the highly compliant patient. However, once fetal viability is attained, readmit the patient to monitor maternal and fetal well-being.

Between 23 and 32 weeks

Treat these women expectantly in the hospital unless there is evidence of infection or fetal compromise. Management includes intravenous antibiotic therapy and corticosteroids, as recommended by the National Institutes of Health (FIGURE 2).5

Although it is controversial, consider magnesium sulfate tocolytic therapy if the patient is actively contracting with no evidence of infection.6

Some authorities recommend amniocentesis (at any gestational age) to rule out infection prior to expectant management, while others consider the appropriate use of clinical parameters to be adequate.6

After monitoring the patient in the labor suite for 24 to 48 hours, transfer her to the antenatal ward, if she is stable, for frequent fetal surveillance and maternal evaluation. Continue to evaluate her for signs of intraamniotic infection such as fever, uterine tenderness, and foulsmelling discharge.

Many authorities recommend daily nonstress testing or biophysical profiles to evaluate fetal well-being.7

Between 32 and 34 weeks

Management for this gestational age range is the most controversial (FIGURE 3). Mercer et al8 demonstrated that expectant management is harmful to the neonate if fetal lung maturity is present. Most experts contend that some method of fetal lung assessment should be undertaken. The most effective method is sampling amniotic fluid by amniocentesis. Not only can fetal lung maturity be determined, but the fluid can be analyzed for evidence of infection using the Gram stain, glucose level, and white blood cell count.

When an amniocentesis site is unavailable, consider assessing fetal lung maturity via a pooled amniotic fluid sample from the vagina.9 Deliver the infant if either intraamniotic infection or fetal lung maturity is present.

If there is no evidence of fetal lung maturity, expectant management is usually recommended for pregnancies between 32 and 34 weeks.

In a recent survey of maternal-fetal medicine specialists in the United States, 58% recommended delivery at 34 weeks of gestation.10

For patients who are at less than 34 weeks upon presentation—or to be treated expectantly—consider giving antibiotics, corticosteroids, and tocolysis during the first 48 hours.

FIGURE 1 Managing premature rupture of membranes: Less than 23 weeks’ gestation

FIGURE 2 Managing premature rupture of membranes: 23 to <32 weeks’ gestation

The new standard of care: antibiotic therapy

In the 1980s, several studies suggested antibiotics were beneficial for PPROM patients.11 More recently, the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Network published the results of a large, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial clearly demonstrating that antibiotics prolong the latency period and decrease neonatal morbidities (see “Antibiotics in PPROM improve outcomes in Maternal-Fetal Medicine Network study”).12

Limited- versus broad-spectrum antibiotics

Although antibiotic therapy is now the standard of care for patients with PPROM, it remains unclear which antibiotic is best. Some researchers have recommended limited-spectrum antibiotics, while others prefer a broader-spectrum approach.13 Several recent studies14 have suggested that erythromycin is effective for eradicating Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma and beneficial for the neonate.

Optimal duration of antibiotic therapy is unclear

Most early studies advocated standard treatment from the time of ruptured membranes until delivery, while others recommended 7 to 10 days of therapy. Several recent trials15 have found 3 days of therapy to be equivalent to 7 days. However, these studies lack sufficient power to warrant a shorter duration of therapy at this time.

Numerous small, prospective, randomized trials comparing antibiotics with placebo have demonstrated prolonged latency (period from rupture of membranes to delivery) in the women with preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) who were given antibiotics.

However, these studies lacked sufficient power to establish a decrease in neonatal morbidity with antibiotics, although a meta-analysis by Mercer and Arheart31 suggested such a decrease existed.

The breakthrough trial

Finally, in 1997, the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Network of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development published a study large enough to definitively answer the question.12

A significant decrease in morbidity and mortality

Since these findings were published, controversy has shifted to the choice of antibiotics and the length and route of administration.

In this study, 614 women between 24 and 32 weeks of gestation with confirmed PPROM were randomized to intravenous ampicillin (2 g every 6 hours) and erythromycin (250 mg every 6 hours) for 48 hours followed by oral amoxicillin (250 mg every 8 hours) and erythromycin base (333 mg every 8 hours) for 5 days, or placebo. None of the women had received corticosteroids for fetal maturation or antibiotic treatment within 1 week of randomization.

In the study group, the composite primary outcome of interest decreased significantly—pregnancies with at least 1 of the following: fetal or infant mortality, respiratory distress, severe intraventricular hemorrhage, stage 2 or 3 necrotizing enterocolitis, or sepsis within 72 hours of birth.

Practice recommendation

I use ampicillin (2 g IV every 6 hours) and azithromycin (500 mg orally or IV on day 1 followed by 250 mg every day for 4 days) because data from the ORACLE trial14 suggested an increased incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. I also treat patients for 7 full days, even though preliminary data suggests 3 days may be adequate.15

More trials ahead

Expect to see many more randomized trials seeking to establish the best antibiotic, route of administration, and length of treatment.

Corticosteroids beneficial if infection is treated

In 1998, the National Institutes of Health issued a Consensus Statement5 recommending corticosteroid therapy to accelerate fetal lung maturity and decrease neonatal morbidity in PPROM patients. Many authorities questioned the wisdom of this recommendation, since earlier studies had suggested an increased risk of maternal morbidity when corticosteroids are given as therapy for PPROM.16 However, these early studies did not use antibiotics to treat infection—the primary cause of PPROM—and many patients underwent digital vaginal exams, which probably contributed to unfavorable maternal and neonatal outcomes.

I recently began treating PPROM patients with antibiotics for 12 hours prior to administering corticosteroids and noted a considerable benefit for steroid therapy.17 I therefore recommend that PPROM patients who are treated expectantly receive corticosteroids unless there is evidence of an infection.

Tocolysis: jury still out

The use of tocolytics also is controversial. Many original studies reported no overall benefit and a significant increase in maternal morbidity when tocolytic therapy was given for ruptured membranes.18 However, many patients in these trials underwent digital vaginal exams and were not given antibiotics, and many received corticosteroids.

In my practice, I give magnesium sulfate and corticosteroids for the first 48 hours to women at or beyond 23 weeks’ gestation, provided there is no evidence of infection.19 However, additional data is needed before this management protocol can be considered the standard of care.

Assess fetal well-being frequently

Initial recommendations for antepartum testing were based on the high perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with PPROM. Nonstress testing was the foundation of therapy, and many authorities advocated daily nonstress testing even in the absence of definitive proof of its benefit.4

In the late 1980s, Vintzileos20 and other experts recommended daily biophysical profiles, suggesting that this strategy could identify patients with subclinical infection.

Daily biophysical profiles: No benefit beyond that of daily nonstress test

My colleagues and I7 conducted the only reported prospective, randomized trial comparing daily biophysical profiles to daily nonstress testing with backup biophysical profiles for abnormalities. We concluded that daily biophysical profiles provide no benefit beyond that achieved with daily nonstress testing. Whether a less intense testing protocol would produce the same benefit is unclear.

Important to recognize high risk of poor perinatal outcome

The important point in managing patients with PPROM is recognizing the high risk of poor perinatal outcome. For this reason, frequent evaluation of fetal well-being is an essential element of any management plan.

Determine mode of delivery as usual, but monitor fetus

In PPROM cases, the fetus often is intolerant of labor, primarily because of oligohydramnios and subclinical infection. For this reason, monitor the fetus very closely in the intrapartum period. Amnioinfusion decreases variable decelerations and improves pH in these patients and should be considered when it is clinically indicated.21

Determine the mode of delivery using routine obstetrical indications. Deliver viable breech infants by cesarean section.

Few data exist on the benefit of cesarean for the very premature neonate; use of routine obstetrical indicators is advisable.

Special situations

Four conditions may affect management of the patient with PPROM:

Cerclage in place

Numerous early studies suggested that this foreign body is a focus of infection and recommended removal. However, recent reports have not substantiated these findings.22 A large, multicenter, prospective, randomized trial is underway, which compares expectant management with cerclage removal when membranes rupture. It should provide a definitive answer.

Herpes simplex infection

If the patient with PPROM has a clinical outbreak of herpes simplex virus, weigh the risk of early delivery against the risk of herpes simplex infection. Major et al23 compiled a case series showing that infants did not become infected with herpes simplex virus when women were managed expectantly. Still, consider prophylactic therapy with antiviral agents in expectantly managed patients. At later gestational ages, most experts recommend delivery.

Bleeding

Placental abruptions occur in about 5% of PPROM pregnancies.24 Some authorities contend that the cause of abruption is placental shearing following leakage of amniotic fluid and decreased intrauterine volume. However, bleeding is rarely substantial enough to warrant delivery. Even so, monitor women with active bleeding in the labor suite, remaining vigilant for evidence of fetal compromise.

Outpatient management

Only 1 study has evaluated outpatient management of women with PPROM.25 Until more definitive information is available, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that outpatient management be limited to approved study protocols.6

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Iams JD, Stilson R, Johnson FF, et al. Symptoms that precede preterm labor and preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:486.-

2. Friedman ML, McElin TW. Diagnosis of ruptured fetal membranes: Clinical study and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;104:544-550.

3. Lewis DF, Major CA, Towers CV, et al. Effects of digital vaginal examinations on latency period in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:630-634.

4. Garite TJ. Management of premature rupture of membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):837-847.

5. National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: effect of corticosteroids for fetal maturation on perinatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:246-252.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin #1: Premature Rupture of Membranes. Washington, DC: ACOG; June 1998.

7. Lewis DF, Adair CD, Weeks JW, et al. A randomized clinical trial of nonstress test versus biophysical profile in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1495-1499.

8. Mercer BM, Crocker LG, Boe NM, et al. Induction versus expectant management in premature rupture of the membranes with mature amniotic fluid at 32 to 36 weeks: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:775-782.

9. Lewis DF, Towers CV, Major CA, et al. Use of Amniostat-FLM in detecting the presence of phosphatidylglycerol in vaginal pool samples in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1139-1143.

10. Healy AJ, Veille J-C, Sciscione A, et al. The timing of elective delivery in preterm rupture of the membranes: a survey of members of the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(5):1479-1481.

11. Amon E, Lewis SV, Sibai BM, et al. Ampicillin prophylaxis in preterm premature rupture of the membranes: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;159:539.-

12. Mercer B, Miodovnik M, Thurnau G, et al. Antibiotic therapy for reduction of infant morbidity after preterm premature rupture of the membranes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278:989-995.

13. Lewis DF, Fontenot MT, Brooks GG, et al. Latency period after preterm premature rupture of membranes: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study comparing ampicillin and ampicillin-sulbactum. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:392-395.

14. Kenyon SL, Taylor DJ, Tarnow-Mordi W. Oracle Collaborative Group. Broad spectrum antibiotics for preterm, prelabor rupture of fetal membranes: the ORACLE I randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;357:979-988.

15. Lewis DF, Adair CD, Robichaux AG, et al. Antibiotic therapy in preterm premature rupture of membranes: are seven days necessary? A preliminary, randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1413-1416;discussion 1416-1417.

16. Vidaeff AC, Ramin SM, Gilstrap III LC. Antenatal corticosteroids in women with preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):797-805.

17. Lewis DF, Brody K, Edwards MS, Brouillette RM. Preterm premature ruptured membranes: a randomized trial of steroids after treatment with antibiotics. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:801-805.

18. Garite TJ, Keegan KA, Freeman RK, et al. A randomized trial of ritodrine tocolysis versus expectant management in patients with premature rupture of membranes at 25 to 30 weeks of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:388-393.

19. Fontenot T, Lewis DF. Tocolytic therapy with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):787-796.

20. Vintzileos AM, Campbell WA, Nochimson DJ, et al. The fetal biophysical profile in patients with premature rupture of the membranes: an early predictor of fetal infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152:510.-

21. Nageotte MP, Freeman RK, Garite TJ, et al. Prophylactic intrapartum amnioinfusion in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:557.-

22. Lee RM, Major CA. Controversial and special situations in the management of preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):877-884.

23. Major CA, Towers CV, Lewis DF, Garite TJ. Expectant management of preterm premature rupture of membranes complicated by active recurrent genital herpes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1551-1554.

24. Major CA, de Veciana M, Lewis DF, Morgan MA. Preterm premature rupture of membranes and abruptio placentae: is there an association between these pregnancy complications? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:672-676.

25. Carlan SJ, O’Brien WF, Parsons MT, et al. Preterm premature rupture of membranes: a randomized study of home versus hospital management. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:61-64.

26. Lee T, Silver H. Etiology and epidemiology of preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):721-734.

27. Savitz DA, Blackmore CA, Thorp JM. Epidemiologic characteristics of preterm delivery: etiologic heterogeneity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:467.-

28. Shiono PH, Klebanoff MA, Rhoads GG. Smoking and drinking during pregnancy: their effects on preterm birth. JAMA. 1986;255:82.-

29. Romero R, Ghidini A, Mazor M, et al. Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in premature rupture of membranes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1991;34:769.-

30. Asrat T. Intra-amniotic infection in patients with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes: pathophysiology, detection, and management. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):735-751.

31. Mercer B, Arheart K. Antimicrobial therapy in expectant management of preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Lancet. 1995;346:1271-1279.

1. Iams JD, Stilson R, Johnson FF, et al. Symptoms that precede preterm labor and preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:486.-

2. Friedman ML, McElin TW. Diagnosis of ruptured fetal membranes: Clinical study and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;104:544-550.

3. Lewis DF, Major CA, Towers CV, et al. Effects of digital vaginal examinations on latency period in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:630-634.

4. Garite TJ. Management of premature rupture of membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):837-847.

5. National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: effect of corticosteroids for fetal maturation on perinatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:246-252.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin #1: Premature Rupture of Membranes. Washington, DC: ACOG; June 1998.

7. Lewis DF, Adair CD, Weeks JW, et al. A randomized clinical trial of nonstress test versus biophysical profile in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1495-1499.

8. Mercer BM, Crocker LG, Boe NM, et al. Induction versus expectant management in premature rupture of the membranes with mature amniotic fluid at 32 to 36 weeks: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:775-782.

9. Lewis DF, Towers CV, Major CA, et al. Use of Amniostat-FLM in detecting the presence of phosphatidylglycerol in vaginal pool samples in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1139-1143.

10. Healy AJ, Veille J-C, Sciscione A, et al. The timing of elective delivery in preterm rupture of the membranes: a survey of members of the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(5):1479-1481.

11. Amon E, Lewis SV, Sibai BM, et al. Ampicillin prophylaxis in preterm premature rupture of the membranes: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;159:539.-

12. Mercer B, Miodovnik M, Thurnau G, et al. Antibiotic therapy for reduction of infant morbidity after preterm premature rupture of the membranes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278:989-995.

13. Lewis DF, Fontenot MT, Brooks GG, et al. Latency period after preterm premature rupture of membranes: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study comparing ampicillin and ampicillin-sulbactum. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:392-395.

14. Kenyon SL, Taylor DJ, Tarnow-Mordi W. Oracle Collaborative Group. Broad spectrum antibiotics for preterm, prelabor rupture of fetal membranes: the ORACLE I randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;357:979-988.

15. Lewis DF, Adair CD, Robichaux AG, et al. Antibiotic therapy in preterm premature rupture of membranes: are seven days necessary? A preliminary, randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1413-1416;discussion 1416-1417.

16. Vidaeff AC, Ramin SM, Gilstrap III LC. Antenatal corticosteroids in women with preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):797-805.

17. Lewis DF, Brody K, Edwards MS, Brouillette RM. Preterm premature ruptured membranes: a randomized trial of steroids after treatment with antibiotics. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:801-805.

18. Garite TJ, Keegan KA, Freeman RK, et al. A randomized trial of ritodrine tocolysis versus expectant management in patients with premature rupture of membranes at 25 to 30 weeks of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:388-393.

19. Fontenot T, Lewis DF. Tocolytic therapy with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):787-796.

20. Vintzileos AM, Campbell WA, Nochimson DJ, et al. The fetal biophysical profile in patients with premature rupture of the membranes: an early predictor of fetal infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152:510.-

21. Nageotte MP, Freeman RK, Garite TJ, et al. Prophylactic intrapartum amnioinfusion in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:557.-

22. Lee RM, Major CA. Controversial and special situations in the management of preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):877-884.

23. Major CA, Towers CV, Lewis DF, Garite TJ. Expectant management of preterm premature rupture of membranes complicated by active recurrent genital herpes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1551-1554.

24. Major CA, de Veciana M, Lewis DF, Morgan MA. Preterm premature rupture of membranes and abruptio placentae: is there an association between these pregnancy complications? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:672-676.

25. Carlan SJ, O’Brien WF, Parsons MT, et al. Preterm premature rupture of membranes: a randomized study of home versus hospital management. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:61-64.

26. Lee T, Silver H. Etiology and epidemiology of preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):721-734.

27. Savitz DA, Blackmore CA, Thorp JM. Epidemiologic characteristics of preterm delivery: etiologic heterogeneity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:467.-

28. Shiono PH, Klebanoff MA, Rhoads GG. Smoking and drinking during pregnancy: their effects on preterm birth. JAMA. 1986;255:82.-

29. Romero R, Ghidini A, Mazor M, et al. Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in premature rupture of membranes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1991;34:769.-

30. Asrat T. Intra-amniotic infection in patients with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes: pathophysiology, detection, and management. Clinics in Perinatology: Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. 2001;28(4):735-751.

31. Mercer B, Arheart K. Antimicrobial therapy in expectant management of preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Lancet. 1995;346:1271-1279.