User login

Does U.S. Healthcare Need More Diverse Leadership?

Throughout its history, the United States has been a nation of immigrants. From the early colonial settlements to the mid-20th century, most immigrants came from Western European countries. Since 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act abolished national-origin quotas, the diversity of immigrants has increased. “By the year 2043,” says Tomás León, president and CEO of the Institute for Diversity in Health Management in Chicago, “we will be a country where the majority of our population is comprised of racial and ethnic minorities.”

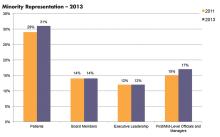

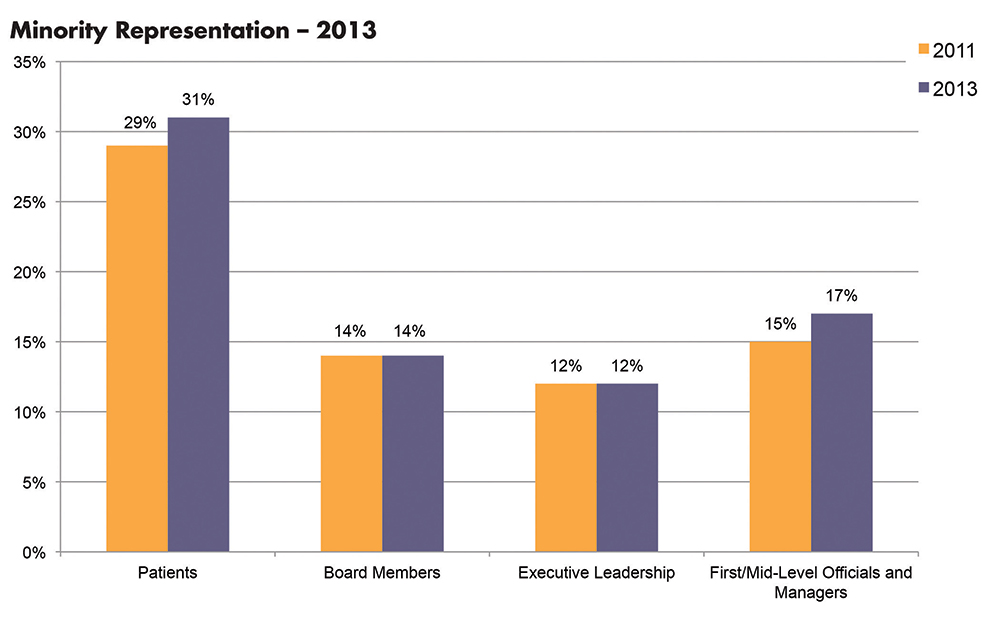

Those changing demographics, cited from the U.S. Census Bureau’s projections, already are evidenced in hospital patient populations. According to a benchmarking survey sponsored by the institute, which is an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, the percentage of minority patients seen in hospitals grew from 29% to 31% of patient census between 2011 and 2013.1 And yet, the survey found this increasing diversity is not currently reflected in leadership positions. During the same time period, underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities (UREM) on hospital boards of directors (14%) and in C-suite positions (14%) remained flat (see Figure 1).

Gender disparities in healthcare and academic leadership also have been slow to change. Periodic surveys conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives indicate that women comprise only 11% of healthcare CEOs in the U.S.2 And despite the fact that women make up half of all medical students (and one-third of full-time faculty), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) finds that women still trail men when it comes to attaining full professorship and decanal positions at their academic institutions.3

The Hospitalist interviewed medical directors, researchers, diversity management professionals, and hospitalists to ascertain current solutions being pursued to narrow the gaps in leadership diversity.

Why Diversity in Leadership Matters

Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in the Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, believes there is a need to encourage the advancement to leadership positions for female and UREM physicians.

“In medicine, it’s really about service. If we are really here for our patients, we need representation of diversity in our faculty and leadership,” says Dr. Howell, a past SHM president and faculty member of SHM’s Leadership Academy since its inception in 2005. In addition, he says, “Diversity adds incredible strength to an organization and adds to the richness of the ideas and solutions to overcome challenging problems.”

With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, formerly uninsured people are now accessing the healthcare system; many are bilingual and bicultural, notes George A. Zeppenfeldt-Cestero, president and CEO, Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives.

“You want to make sure that providers, whether they are physicians, nurses, dentists, or health executives that drive policy issues, are also reflective of that population throughout the organization,” he says. “The real definition of diversity is making sure you have diversity in all layers of the workforce, including the C-suite.”

León points to the coming “seismic demographic shifts” and wonders if healthcare is ready to become more reflective of the communities it serves.

“Increasing diversity in healthcare leadership and governance is essential for the delivery and provision of culturally competent care,” León says. “Now, more than ever, it’s important that we collectively accelerate progress in this area.”

Advancing in Academic and Hospital Medicine

Might hospital medicine offer additional opportunities for women and minorities to advance into leadership positions? Hospitalist Flora Kisuule, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and associate division director of the Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service (CIMS) at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, believes this may be the case. She was with Dr. Howell’s group when he needed to fill the associate director position.

“My advancement speaks to hospital medicine and the fact that we are growing as a field,” she says. “Because of that, opportunities are presenting themselves.”

Dr. Kisuule’s ability to thrive in her position speaks to her professionalism but also to a number of other intentional factors: Dr. Howell’s continuing sponsorship to include her in leadership opportunities, an emergency call system for parents with sick children, and a women’s task force whose agenda calls for transparency in hiring and advancement.

Intentional Structure Change

Cardiologist Hannah A. Valantine, MD, recognizes the importance of addressing the lack of women and people from unrepresented groups in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) workforce. While at Stanford University School of Medicine, she developed and put into place a set of strategies to understand and mitigate the drivers of gender imbalance. Since then, Dr. Valantine was recruited to bring her expertise to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., where she is the inaugural chief officer for scientific workforce diversity. In this role, she is committed “to promoting biomedical workforce diversity as an opportunity, not a problem.”

Dr. Valantine is pushing NIH to pursue a wide range of evidence-based programming to eliminate career-transition barriers that keep women and individuals from underrepresented groups from attaining spots in the top echelons of science and health leadership. She believes that applying scientific rigor to the issue of workforce diversity can lead to quantifiable, translatable, and repeatable methods for recruitment and retention of talent in the biomedical workforce (see “Building Blocks").

Before joining NIH, Dr. Valantine and her colleagues at Stanford surveyed gender composition and faculty satisfaction several years after initiating a multifaceted intervention to boost recruitment and development of women faculty.4 After making a visible commitment of resources to support faculty, with special attention to women, Stanford rose from below to above national benchmarks in the representation of women among faculty. Yet significant work remains to be done, Dr. Valantine says. Her work predicts that the estimated time to achieve 50% occupancy of full professorships by women nationally approaches 50 years—“far too long using current approaches.”

In a separate review article, Dr. Valantine and co-author Christy Sandborg, MD, described the Stanford University School of Medicine Academic Biomedical Career Customization (ABCC) model, which was adapted from Deloitte’s Mass Career Customization framework and allows for development of individual career plans that span a faculty member’s total career, not just a year or two at a time. Long-term planning can enable better alignment between the work culture and values of the workforce, which will improve the outlook for women faculty, Dr. Valantine says.

The issues of work-life balance may actually be generational, Dr. Valantine explains. Veteran hospitalist Janet Nagamine, MD, BSN, SFHM, of Santa Clara, Calif., agrees.

“Nowadays, men as well as women are looking for work-life balance,” she says.

In hospital medicine, Dr. Nagamine points out, the structural changes required to effect a work-life balance for hospital leaders are often difficult to achieve.

“As productivity surveys show, HM group leaders are putting in as many RVUs as the staff,” the former SHM board member says. “There is no dedicated time for administrative duties.”

Construct a Pipeline

Barriers to advancement often are particular to characteristics of diverse populations. For example, the AAMC’s report on the U.S. physician workforce documents that in African-American physicians 40 and younger, women outnumber their male counterparts. Therefore, in the association’s Diversity in Medical Education: Facts and Figures 2012 report, the executive summary points out the need to strengthen the medical education pipeline to increase the number of African-American males who enter the premed track.

Despite the fast-growing percentage of Latino and Hispanic populations in the United States, the shortage of Latino/Hispanic physicians increased from 1980 to 2010. Latinos/Hispanics are greatly underrepresented in the medical student, resident, and faculty populations, according to John Paul Sánchez, MD, MPH, assistant dean for diversity and inclusion in the Office for Diversity and Community Engagement at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Likewise, Zeppenfeldt-Cestero believes that efforts must begin much earlier with Latino and other minority and underrepresented students.

“We have to make sure our students pursue the STEM disciplines and that they also later have the education and preparation to be competitive at the MBA or MPH levels,” he says.

Dr. Sánchez, an associate professor of emergency medicine and a diversity activist since his med school days, is the recipient of last year’s Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives’ academic leader of the year award. Since September 2014, he has been involved with Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians Inc., which collaborates with more than 40 medical schools across the country. The initiative offers conferences designed to develop diverse medical students’ and residents’ interest in pursuing academic medicine. Open to all medical students and residents, the conference curriculum is tailored for women, UREMs, and trainees who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), he says. Seven conferences were held in 2015, 10 are planned for this year, and seven for 2017.

Healthcare Leadership Gaps

Despite their omnipresence in healthcare, there is a dearth of women in chief executive and governance roles, as has been noted by both the American College of Healthcare Executives and the National Center for Healthcare Leadership. As with academic leadership positions, the leadership gap in the administrative sector does not seem to be due to a lack of women entering graduate programs in health administration. On the contrary, since the mid-1980s women have comprised 50% to 60% of graduate students.

“This is absolutely not a pipeline issue,” says Christy Harris Lemak, PhD, FACHE, professor and chair of the Department of Health Services Administration at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Health Professions and lead investigator of the National Center for Healthcare Leadership’s study of women in healthcare executive positions. Other factors come into play.

In the study, she and her co-authors queried female healthcare CEOs to ascertain the critical career inflection points that led to their success.6 Those who were strategic about their careers, sought out mentors, and voiced their intentions about pursuing leadership positions were more likely to be successful in those efforts. However, individual career efforts must be coupled with overall organizational commitment to fostering inclusion (see “Path to the Top: Strategic Advice for Women").

Hospitals and healthcare organizations must pursue the development of human capital (and the diversity of their leaders) in a systematic way. “We recommended [in the study] that organizations set expectations that leaders who mentor other potential leaders be rewarded in the same way as those who hit financial targets or readmission rate targets,” Dr. Lemak says.

Leadership matters, agrees Deborah J. Bowen, FACHE, CAE, president and CEO of Chicago-based American College of Healthcare Executives.

“I think we’re getting a little smarter. Organizational leaders and trustees have a better understanding that talent development is one of the most important jobs,” she says. “If you don’t have the right people in the right places making good decisions on behalf of the patients and the populations in the communities they’re serving, the rest falls apart.”

Nuances of Mentoring

Many conversations about encouraging diversity in healthcare leadership converge around the role of effective mentoring and sponsorship. A substantial body of research supports the impact of mentoring on retention, research productivity, career satisfaction, and career development for women. It’s important to ensure that the institutional culture is geared toward mentoring junior faculty, says Jessie Kimbrough Marshall, MD, MPH, assistant professor in the Division of General Medicine Hospitalist Program at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor (UMHS).

Several of our sources pointed out that leaders must learn how to be effective mentors. More attention is being given to enhancing leaders’ mentorship skills. One example is at the Institute for Diversity in Health Management, which conducts an intensive 12-month certificate in diversity management program for practitioners. León says the program fosters ongoing networking and support through the American Leadership Council on Diversity in Healthcare by building leadership competencies.

Dr. Valantine points out that mentoring is hardly a one-style-fits-all proposition but that it is a crucial element to creating and retaining diversity. She says it should be viewed “much more broadly than it is today, and it should focus beyond the trainer-trainee relationship.”

The process is a two-way street. Denege Ward, MD, hospitalist, assistant professor of internal medicine, and director of the medical short stay unit at UMHS, says minorities need to be ready to take a leap of faith.

“Underrepresented faculty and staff should take the risk of possible failure in challenging situations but learn from it and do better and not succumb to fear in face of challenges,” Dr. Ward says.

Although mentoring is one important component in building diversity in academic medicine, Dr. Sánchez asserts that role models, champions, and sponsors are equally important.

“In addition and separate from role models, there must be in place policies and procedures that promote a climate for diverse individuals to succeed,” he says. “What’s needed is an institutional vision and strategic plan that recognizes the importance of diversity. [It] has to become a core principle.”

Dr. Marshall echoes that refrain, noting the recruitment and retention of a diverse set of leaders will take time and intentionality. She is actively engaged in organizing annual meeting mentoring panels at the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“There are still quite a few barriers for women and minorities to advance into hospital leadership roles,” she says. “We still have a long way to go. However, I’m seeing more women and people of color get into these positions. The numbers are increasing, and that encourages me.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Institute for Diversity in Health Management. The state of health care diversity and disparities: a benchmarking study of U.S. hospitals. Available at: http://www.diversityconnection.org/diversityconnection/leadership-conferences/Benchmarking-Survey.jsp?fll=S11.

- Top issues confronting hospitals in 2015. American College of Healthcare Executives website. Available at: https://www.ache.org/pubs/research/ceoissues.cfm. Accessed March 5, 2016.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the physician workforce: facts & figures 2014. Available at: http://aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/.

- Valantine HA, Grewal D, Ku MC, et al. The gender gap in academic medicine: comparing results from a multifaceted intervention for Stanford faculty to peer and national cohorts. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):904-911.

- Valantine H, Sandborg CI. Changing the culture of academic medicine to eliminate the gender leadership gap: 50/50 by 2020. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1411-1413.

- Sexton DW, Lemak CH, Wainio JA. Career inflection points of women who successfully achieved the hospital CEO position. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):367-383.

Throughout its history, the United States has been a nation of immigrants. From the early colonial settlements to the mid-20th century, most immigrants came from Western European countries. Since 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act abolished national-origin quotas, the diversity of immigrants has increased. “By the year 2043,” says Tomás León, president and CEO of the Institute for Diversity in Health Management in Chicago, “we will be a country where the majority of our population is comprised of racial and ethnic minorities.”

Those changing demographics, cited from the U.S. Census Bureau’s projections, already are evidenced in hospital patient populations. According to a benchmarking survey sponsored by the institute, which is an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, the percentage of minority patients seen in hospitals grew from 29% to 31% of patient census between 2011 and 2013.1 And yet, the survey found this increasing diversity is not currently reflected in leadership positions. During the same time period, underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities (UREM) on hospital boards of directors (14%) and in C-suite positions (14%) remained flat (see Figure 1).

Gender disparities in healthcare and academic leadership also have been slow to change. Periodic surveys conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives indicate that women comprise only 11% of healthcare CEOs in the U.S.2 And despite the fact that women make up half of all medical students (and one-third of full-time faculty), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) finds that women still trail men when it comes to attaining full professorship and decanal positions at their academic institutions.3

The Hospitalist interviewed medical directors, researchers, diversity management professionals, and hospitalists to ascertain current solutions being pursued to narrow the gaps in leadership diversity.

Why Diversity in Leadership Matters

Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in the Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, believes there is a need to encourage the advancement to leadership positions for female and UREM physicians.

“In medicine, it’s really about service. If we are really here for our patients, we need representation of diversity in our faculty and leadership,” says Dr. Howell, a past SHM president and faculty member of SHM’s Leadership Academy since its inception in 2005. In addition, he says, “Diversity adds incredible strength to an organization and adds to the richness of the ideas and solutions to overcome challenging problems.”

With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, formerly uninsured people are now accessing the healthcare system; many are bilingual and bicultural, notes George A. Zeppenfeldt-Cestero, president and CEO, Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives.

“You want to make sure that providers, whether they are physicians, nurses, dentists, or health executives that drive policy issues, are also reflective of that population throughout the organization,” he says. “The real definition of diversity is making sure you have diversity in all layers of the workforce, including the C-suite.”

León points to the coming “seismic demographic shifts” and wonders if healthcare is ready to become more reflective of the communities it serves.

“Increasing diversity in healthcare leadership and governance is essential for the delivery and provision of culturally competent care,” León says. “Now, more than ever, it’s important that we collectively accelerate progress in this area.”

Advancing in Academic and Hospital Medicine

Might hospital medicine offer additional opportunities for women and minorities to advance into leadership positions? Hospitalist Flora Kisuule, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and associate division director of the Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service (CIMS) at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, believes this may be the case. She was with Dr. Howell’s group when he needed to fill the associate director position.

“My advancement speaks to hospital medicine and the fact that we are growing as a field,” she says. “Because of that, opportunities are presenting themselves.”

Dr. Kisuule’s ability to thrive in her position speaks to her professionalism but also to a number of other intentional factors: Dr. Howell’s continuing sponsorship to include her in leadership opportunities, an emergency call system for parents with sick children, and a women’s task force whose agenda calls for transparency in hiring and advancement.

Intentional Structure Change

Cardiologist Hannah A. Valantine, MD, recognizes the importance of addressing the lack of women and people from unrepresented groups in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) workforce. While at Stanford University School of Medicine, she developed and put into place a set of strategies to understand and mitigate the drivers of gender imbalance. Since then, Dr. Valantine was recruited to bring her expertise to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., where she is the inaugural chief officer for scientific workforce diversity. In this role, she is committed “to promoting biomedical workforce diversity as an opportunity, not a problem.”

Dr. Valantine is pushing NIH to pursue a wide range of evidence-based programming to eliminate career-transition barriers that keep women and individuals from underrepresented groups from attaining spots in the top echelons of science and health leadership. She believes that applying scientific rigor to the issue of workforce diversity can lead to quantifiable, translatable, and repeatable methods for recruitment and retention of talent in the biomedical workforce (see “Building Blocks").

Before joining NIH, Dr. Valantine and her colleagues at Stanford surveyed gender composition and faculty satisfaction several years after initiating a multifaceted intervention to boost recruitment and development of women faculty.4 After making a visible commitment of resources to support faculty, with special attention to women, Stanford rose from below to above national benchmarks in the representation of women among faculty. Yet significant work remains to be done, Dr. Valantine says. Her work predicts that the estimated time to achieve 50% occupancy of full professorships by women nationally approaches 50 years—“far too long using current approaches.”

In a separate review article, Dr. Valantine and co-author Christy Sandborg, MD, described the Stanford University School of Medicine Academic Biomedical Career Customization (ABCC) model, which was adapted from Deloitte’s Mass Career Customization framework and allows for development of individual career plans that span a faculty member’s total career, not just a year or two at a time. Long-term planning can enable better alignment between the work culture and values of the workforce, which will improve the outlook for women faculty, Dr. Valantine says.

The issues of work-life balance may actually be generational, Dr. Valantine explains. Veteran hospitalist Janet Nagamine, MD, BSN, SFHM, of Santa Clara, Calif., agrees.

“Nowadays, men as well as women are looking for work-life balance,” she says.

In hospital medicine, Dr. Nagamine points out, the structural changes required to effect a work-life balance for hospital leaders are often difficult to achieve.

“As productivity surveys show, HM group leaders are putting in as many RVUs as the staff,” the former SHM board member says. “There is no dedicated time for administrative duties.”

Construct a Pipeline

Barriers to advancement often are particular to characteristics of diverse populations. For example, the AAMC’s report on the U.S. physician workforce documents that in African-American physicians 40 and younger, women outnumber their male counterparts. Therefore, in the association’s Diversity in Medical Education: Facts and Figures 2012 report, the executive summary points out the need to strengthen the medical education pipeline to increase the number of African-American males who enter the premed track.

Despite the fast-growing percentage of Latino and Hispanic populations in the United States, the shortage of Latino/Hispanic physicians increased from 1980 to 2010. Latinos/Hispanics are greatly underrepresented in the medical student, resident, and faculty populations, according to John Paul Sánchez, MD, MPH, assistant dean for diversity and inclusion in the Office for Diversity and Community Engagement at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Likewise, Zeppenfeldt-Cestero believes that efforts must begin much earlier with Latino and other minority and underrepresented students.

“We have to make sure our students pursue the STEM disciplines and that they also later have the education and preparation to be competitive at the MBA or MPH levels,” he says.

Dr. Sánchez, an associate professor of emergency medicine and a diversity activist since his med school days, is the recipient of last year’s Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives’ academic leader of the year award. Since September 2014, he has been involved with Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians Inc., which collaborates with more than 40 medical schools across the country. The initiative offers conferences designed to develop diverse medical students’ and residents’ interest in pursuing academic medicine. Open to all medical students and residents, the conference curriculum is tailored for women, UREMs, and trainees who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), he says. Seven conferences were held in 2015, 10 are planned for this year, and seven for 2017.

Healthcare Leadership Gaps

Despite their omnipresence in healthcare, there is a dearth of women in chief executive and governance roles, as has been noted by both the American College of Healthcare Executives and the National Center for Healthcare Leadership. As with academic leadership positions, the leadership gap in the administrative sector does not seem to be due to a lack of women entering graduate programs in health administration. On the contrary, since the mid-1980s women have comprised 50% to 60% of graduate students.

“This is absolutely not a pipeline issue,” says Christy Harris Lemak, PhD, FACHE, professor and chair of the Department of Health Services Administration at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Health Professions and lead investigator of the National Center for Healthcare Leadership’s study of women in healthcare executive positions. Other factors come into play.

In the study, she and her co-authors queried female healthcare CEOs to ascertain the critical career inflection points that led to their success.6 Those who were strategic about their careers, sought out mentors, and voiced their intentions about pursuing leadership positions were more likely to be successful in those efforts. However, individual career efforts must be coupled with overall organizational commitment to fostering inclusion (see “Path to the Top: Strategic Advice for Women").

Hospitals and healthcare organizations must pursue the development of human capital (and the diversity of their leaders) in a systematic way. “We recommended [in the study] that organizations set expectations that leaders who mentor other potential leaders be rewarded in the same way as those who hit financial targets or readmission rate targets,” Dr. Lemak says.

Leadership matters, agrees Deborah J. Bowen, FACHE, CAE, president and CEO of Chicago-based American College of Healthcare Executives.

“I think we’re getting a little smarter. Organizational leaders and trustees have a better understanding that talent development is one of the most important jobs,” she says. “If you don’t have the right people in the right places making good decisions on behalf of the patients and the populations in the communities they’re serving, the rest falls apart.”

Nuances of Mentoring

Many conversations about encouraging diversity in healthcare leadership converge around the role of effective mentoring and sponsorship. A substantial body of research supports the impact of mentoring on retention, research productivity, career satisfaction, and career development for women. It’s important to ensure that the institutional culture is geared toward mentoring junior faculty, says Jessie Kimbrough Marshall, MD, MPH, assistant professor in the Division of General Medicine Hospitalist Program at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor (UMHS).

Several of our sources pointed out that leaders must learn how to be effective mentors. More attention is being given to enhancing leaders’ mentorship skills. One example is at the Institute for Diversity in Health Management, which conducts an intensive 12-month certificate in diversity management program for practitioners. León says the program fosters ongoing networking and support through the American Leadership Council on Diversity in Healthcare by building leadership competencies.

Dr. Valantine points out that mentoring is hardly a one-style-fits-all proposition but that it is a crucial element to creating and retaining diversity. She says it should be viewed “much more broadly than it is today, and it should focus beyond the trainer-trainee relationship.”

The process is a two-way street. Denege Ward, MD, hospitalist, assistant professor of internal medicine, and director of the medical short stay unit at UMHS, says minorities need to be ready to take a leap of faith.

“Underrepresented faculty and staff should take the risk of possible failure in challenging situations but learn from it and do better and not succumb to fear in face of challenges,” Dr. Ward says.

Although mentoring is one important component in building diversity in academic medicine, Dr. Sánchez asserts that role models, champions, and sponsors are equally important.

“In addition and separate from role models, there must be in place policies and procedures that promote a climate for diverse individuals to succeed,” he says. “What’s needed is an institutional vision and strategic plan that recognizes the importance of diversity. [It] has to become a core principle.”

Dr. Marshall echoes that refrain, noting the recruitment and retention of a diverse set of leaders will take time and intentionality. She is actively engaged in organizing annual meeting mentoring panels at the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“There are still quite a few barriers for women and minorities to advance into hospital leadership roles,” she says. “We still have a long way to go. However, I’m seeing more women and people of color get into these positions. The numbers are increasing, and that encourages me.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Institute for Diversity in Health Management. The state of health care diversity and disparities: a benchmarking study of U.S. hospitals. Available at: http://www.diversityconnection.org/diversityconnection/leadership-conferences/Benchmarking-Survey.jsp?fll=S11.

- Top issues confronting hospitals in 2015. American College of Healthcare Executives website. Available at: https://www.ache.org/pubs/research/ceoissues.cfm. Accessed March 5, 2016.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the physician workforce: facts & figures 2014. Available at: http://aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/.

- Valantine HA, Grewal D, Ku MC, et al. The gender gap in academic medicine: comparing results from a multifaceted intervention for Stanford faculty to peer and national cohorts. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):904-911.

- Valantine H, Sandborg CI. Changing the culture of academic medicine to eliminate the gender leadership gap: 50/50 by 2020. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1411-1413.

- Sexton DW, Lemak CH, Wainio JA. Career inflection points of women who successfully achieved the hospital CEO position. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):367-383.

Throughout its history, the United States has been a nation of immigrants. From the early colonial settlements to the mid-20th century, most immigrants came from Western European countries. Since 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act abolished national-origin quotas, the diversity of immigrants has increased. “By the year 2043,” says Tomás León, president and CEO of the Institute for Diversity in Health Management in Chicago, “we will be a country where the majority of our population is comprised of racial and ethnic minorities.”

Those changing demographics, cited from the U.S. Census Bureau’s projections, already are evidenced in hospital patient populations. According to a benchmarking survey sponsored by the institute, which is an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, the percentage of minority patients seen in hospitals grew from 29% to 31% of patient census between 2011 and 2013.1 And yet, the survey found this increasing diversity is not currently reflected in leadership positions. During the same time period, underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities (UREM) on hospital boards of directors (14%) and in C-suite positions (14%) remained flat (see Figure 1).

Gender disparities in healthcare and academic leadership also have been slow to change. Periodic surveys conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives indicate that women comprise only 11% of healthcare CEOs in the U.S.2 And despite the fact that women make up half of all medical students (and one-third of full-time faculty), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) finds that women still trail men when it comes to attaining full professorship and decanal positions at their academic institutions.3

The Hospitalist interviewed medical directors, researchers, diversity management professionals, and hospitalists to ascertain current solutions being pursued to narrow the gaps in leadership diversity.

Why Diversity in Leadership Matters

Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in the Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, believes there is a need to encourage the advancement to leadership positions for female and UREM physicians.

“In medicine, it’s really about service. If we are really here for our patients, we need representation of diversity in our faculty and leadership,” says Dr. Howell, a past SHM president and faculty member of SHM’s Leadership Academy since its inception in 2005. In addition, he says, “Diversity adds incredible strength to an organization and adds to the richness of the ideas and solutions to overcome challenging problems.”

With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, formerly uninsured people are now accessing the healthcare system; many are bilingual and bicultural, notes George A. Zeppenfeldt-Cestero, president and CEO, Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives.

“You want to make sure that providers, whether they are physicians, nurses, dentists, or health executives that drive policy issues, are also reflective of that population throughout the organization,” he says. “The real definition of diversity is making sure you have diversity in all layers of the workforce, including the C-suite.”

León points to the coming “seismic demographic shifts” and wonders if healthcare is ready to become more reflective of the communities it serves.

“Increasing diversity in healthcare leadership and governance is essential for the delivery and provision of culturally competent care,” León says. “Now, more than ever, it’s important that we collectively accelerate progress in this area.”

Advancing in Academic and Hospital Medicine

Might hospital medicine offer additional opportunities for women and minorities to advance into leadership positions? Hospitalist Flora Kisuule, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and associate division director of the Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service (CIMS) at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, believes this may be the case. She was with Dr. Howell’s group when he needed to fill the associate director position.

“My advancement speaks to hospital medicine and the fact that we are growing as a field,” she says. “Because of that, opportunities are presenting themselves.”

Dr. Kisuule’s ability to thrive in her position speaks to her professionalism but also to a number of other intentional factors: Dr. Howell’s continuing sponsorship to include her in leadership opportunities, an emergency call system for parents with sick children, and a women’s task force whose agenda calls for transparency in hiring and advancement.

Intentional Structure Change

Cardiologist Hannah A. Valantine, MD, recognizes the importance of addressing the lack of women and people from unrepresented groups in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) workforce. While at Stanford University School of Medicine, she developed and put into place a set of strategies to understand and mitigate the drivers of gender imbalance. Since then, Dr. Valantine was recruited to bring her expertise to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., where she is the inaugural chief officer for scientific workforce diversity. In this role, she is committed “to promoting biomedical workforce diversity as an opportunity, not a problem.”

Dr. Valantine is pushing NIH to pursue a wide range of evidence-based programming to eliminate career-transition barriers that keep women and individuals from underrepresented groups from attaining spots in the top echelons of science and health leadership. She believes that applying scientific rigor to the issue of workforce diversity can lead to quantifiable, translatable, and repeatable methods for recruitment and retention of talent in the biomedical workforce (see “Building Blocks").

Before joining NIH, Dr. Valantine and her colleagues at Stanford surveyed gender composition and faculty satisfaction several years after initiating a multifaceted intervention to boost recruitment and development of women faculty.4 After making a visible commitment of resources to support faculty, with special attention to women, Stanford rose from below to above national benchmarks in the representation of women among faculty. Yet significant work remains to be done, Dr. Valantine says. Her work predicts that the estimated time to achieve 50% occupancy of full professorships by women nationally approaches 50 years—“far too long using current approaches.”

In a separate review article, Dr. Valantine and co-author Christy Sandborg, MD, described the Stanford University School of Medicine Academic Biomedical Career Customization (ABCC) model, which was adapted from Deloitte’s Mass Career Customization framework and allows for development of individual career plans that span a faculty member’s total career, not just a year or two at a time. Long-term planning can enable better alignment between the work culture and values of the workforce, which will improve the outlook for women faculty, Dr. Valantine says.

The issues of work-life balance may actually be generational, Dr. Valantine explains. Veteran hospitalist Janet Nagamine, MD, BSN, SFHM, of Santa Clara, Calif., agrees.

“Nowadays, men as well as women are looking for work-life balance,” she says.

In hospital medicine, Dr. Nagamine points out, the structural changes required to effect a work-life balance for hospital leaders are often difficult to achieve.

“As productivity surveys show, HM group leaders are putting in as many RVUs as the staff,” the former SHM board member says. “There is no dedicated time for administrative duties.”

Construct a Pipeline

Barriers to advancement often are particular to characteristics of diverse populations. For example, the AAMC’s report on the U.S. physician workforce documents that in African-American physicians 40 and younger, women outnumber their male counterparts. Therefore, in the association’s Diversity in Medical Education: Facts and Figures 2012 report, the executive summary points out the need to strengthen the medical education pipeline to increase the number of African-American males who enter the premed track.

Despite the fast-growing percentage of Latino and Hispanic populations in the United States, the shortage of Latino/Hispanic physicians increased from 1980 to 2010. Latinos/Hispanics are greatly underrepresented in the medical student, resident, and faculty populations, according to John Paul Sánchez, MD, MPH, assistant dean for diversity and inclusion in the Office for Diversity and Community Engagement at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Likewise, Zeppenfeldt-Cestero believes that efforts must begin much earlier with Latino and other minority and underrepresented students.

“We have to make sure our students pursue the STEM disciplines and that they also later have the education and preparation to be competitive at the MBA or MPH levels,” he says.

Dr. Sánchez, an associate professor of emergency medicine and a diversity activist since his med school days, is the recipient of last year’s Association of Hispanic Healthcare Executives’ academic leader of the year award. Since September 2014, he has been involved with Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians Inc., which collaborates with more than 40 medical schools across the country. The initiative offers conferences designed to develop diverse medical students’ and residents’ interest in pursuing academic medicine. Open to all medical students and residents, the conference curriculum is tailored for women, UREMs, and trainees who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), he says. Seven conferences were held in 2015, 10 are planned for this year, and seven for 2017.

Healthcare Leadership Gaps

Despite their omnipresence in healthcare, there is a dearth of women in chief executive and governance roles, as has been noted by both the American College of Healthcare Executives and the National Center for Healthcare Leadership. As with academic leadership positions, the leadership gap in the administrative sector does not seem to be due to a lack of women entering graduate programs in health administration. On the contrary, since the mid-1980s women have comprised 50% to 60% of graduate students.

“This is absolutely not a pipeline issue,” says Christy Harris Lemak, PhD, FACHE, professor and chair of the Department of Health Services Administration at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Health Professions and lead investigator of the National Center for Healthcare Leadership’s study of women in healthcare executive positions. Other factors come into play.

In the study, she and her co-authors queried female healthcare CEOs to ascertain the critical career inflection points that led to their success.6 Those who were strategic about their careers, sought out mentors, and voiced their intentions about pursuing leadership positions were more likely to be successful in those efforts. However, individual career efforts must be coupled with overall organizational commitment to fostering inclusion (see “Path to the Top: Strategic Advice for Women").

Hospitals and healthcare organizations must pursue the development of human capital (and the diversity of their leaders) in a systematic way. “We recommended [in the study] that organizations set expectations that leaders who mentor other potential leaders be rewarded in the same way as those who hit financial targets or readmission rate targets,” Dr. Lemak says.

Leadership matters, agrees Deborah J. Bowen, FACHE, CAE, president and CEO of Chicago-based American College of Healthcare Executives.

“I think we’re getting a little smarter. Organizational leaders and trustees have a better understanding that talent development is one of the most important jobs,” she says. “If you don’t have the right people in the right places making good decisions on behalf of the patients and the populations in the communities they’re serving, the rest falls apart.”

Nuances of Mentoring

Many conversations about encouraging diversity in healthcare leadership converge around the role of effective mentoring and sponsorship. A substantial body of research supports the impact of mentoring on retention, research productivity, career satisfaction, and career development for women. It’s important to ensure that the institutional culture is geared toward mentoring junior faculty, says Jessie Kimbrough Marshall, MD, MPH, assistant professor in the Division of General Medicine Hospitalist Program at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor (UMHS).

Several of our sources pointed out that leaders must learn how to be effective mentors. More attention is being given to enhancing leaders’ mentorship skills. One example is at the Institute for Diversity in Health Management, which conducts an intensive 12-month certificate in diversity management program for practitioners. León says the program fosters ongoing networking and support through the American Leadership Council on Diversity in Healthcare by building leadership competencies.

Dr. Valantine points out that mentoring is hardly a one-style-fits-all proposition but that it is a crucial element to creating and retaining diversity. She says it should be viewed “much more broadly than it is today, and it should focus beyond the trainer-trainee relationship.”

The process is a two-way street. Denege Ward, MD, hospitalist, assistant professor of internal medicine, and director of the medical short stay unit at UMHS, says minorities need to be ready to take a leap of faith.

“Underrepresented faculty and staff should take the risk of possible failure in challenging situations but learn from it and do better and not succumb to fear in face of challenges,” Dr. Ward says.

Although mentoring is one important component in building diversity in academic medicine, Dr. Sánchez asserts that role models, champions, and sponsors are equally important.

“In addition and separate from role models, there must be in place policies and procedures that promote a climate for diverse individuals to succeed,” he says. “What’s needed is an institutional vision and strategic plan that recognizes the importance of diversity. [It] has to become a core principle.”

Dr. Marshall echoes that refrain, noting the recruitment and retention of a diverse set of leaders will take time and intentionality. She is actively engaged in organizing annual meeting mentoring panels at the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“There are still quite a few barriers for women and minorities to advance into hospital leadership roles,” she says. “We still have a long way to go. However, I’m seeing more women and people of color get into these positions. The numbers are increasing, and that encourages me.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Institute for Diversity in Health Management. The state of health care diversity and disparities: a benchmarking study of U.S. hospitals. Available at: http://www.diversityconnection.org/diversityconnection/leadership-conferences/Benchmarking-Survey.jsp?fll=S11.

- Top issues confronting hospitals in 2015. American College of Healthcare Executives website. Available at: https://www.ache.org/pubs/research/ceoissues.cfm. Accessed March 5, 2016.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the physician workforce: facts & figures 2014. Available at: http://aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/.

- Valantine HA, Grewal D, Ku MC, et al. The gender gap in academic medicine: comparing results from a multifaceted intervention for Stanford faculty to peer and national cohorts. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):904-911.

- Valantine H, Sandborg CI. Changing the culture of academic medicine to eliminate the gender leadership gap: 50/50 by 2020. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1411-1413.

- Sexton DW, Lemak CH, Wainio JA. Career inflection points of women who successfully achieved the hospital CEO position. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):367-383.

Hospitalist-Led Quality Initiatives Plentiful at Community Hospitals

Community hospitals offer multiple opportunities for hospitalists to become involved in both quality assurance and quality improvement. To help steer the right approach and avoid possible missteps, it’s important to acknowledge the differences between the community and academic settings, according to two medical directors with whom we spoke.

For example, in the rural, 47-bed Riverside Tappahannock Hospital where Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, SFHM, is medical director for hospital-based quality, cost effectiveness is king.

“We live on a thin margin, and being sure we provide cost-effective care is the difference between having adequate nursing and not,” he says. It’s a critical difference from academic institutions, he notes, where “there is protected time to do QI, research, and administrative tasks.”

Dr. Ferrance advises those interested in tackling quality projects to “make sure that the project is tied to quality measures and that you’re being cognizant of the cost impact.”

Although much of the work around quality assurance and quality improvement in the community hospital setting is being tackled by nonphysician administrative partners, “those people are usually more than happy to develop a physician partner,” says Colleen A. McCoy, MD, PhD, medical director for hospital medicine at Williamsport (Pa.) Regional Medical Center, a part of the Susquehanna Health System.

“The idea is to look for quality projects where there is a quantifiable financial payoff to the hospital,” she says. That could be a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) core measure or helping to rewrite an order set for new inpatient guidelines on stroke, as Dr. McCoy did at her hospital.

First Order of Business

Dr. McCoy has been actively engaged in quality initiatives since she joined Williams-port in 2012. She cautions new hospitalists to spend the first six months at their new job developing a reputation for clinical excellence and attention to detail.

“Having a reputation that is respected clinically opens many doors,” she says. As generalists, hospitalists interact with a wider variety of staff than specialists. This leads to broad early exposure to a diverse group of decision makers in your institution. “As a hospitalist, you can get a lot of credibility in your organization much sooner than, for example, a young cardiologist or a young gastroenterologist,” she notes.

It is also important for new hospitalists to be mindful of their position in the organization and to watch how their institutions work and operate, so that when they propose a project they are not doing so from a critical standpoint.

“Unrequested input is often seen as criticism,” she says.

Dr. Ferrance agrees. “It’s always a good idea to make sure we focus on processes and not on people in the process.”

Meeting the Mark

“If you want to leapfrog into doing things quickly, you have to be very savvy about the cost impact of your quality improvement,” continues Dr. McCoy. She and Dr. Ferrance advise those just getting started to consider tackling core measures that are reported to CMS or to identify other quality improvement projects that can be financially quantified.

Early on at Riverside Tappahannock Hospital, Dr. Ferrance participated in root cause analyses and developed (at that time) paper-based standard order sets with quality measures attached to them.

Because of her attention to detail during her orientation at Williamsport, Dr. McCoy, who had been a clinical instructor at Emory University and worked for Kaiser Permanente, quickly spotted some necessary omissions regarding DVT prophylaxis. She helped rewrite the ICU admission order sets, inserting a query for DVT prophylaxis. That one intervention helped to increase compliance on a CMS core measure.

Assess Advancement Ops

Is your community hospital open to QI projects? Dr. McCoy says candidates should ask direct questions during job interviews to assess a prospective employer’s approach to quality. She suggests two fair questions:

- Is it possible, within my first two years here as a junior staff member, to participate in a QI project?

- If I were successful in that venture, is this organization open and able to give me more opportunities in that field?

It is key for the medical director to know who in the administrative organization of the hospital would really appreciate a physician partner or physician champion for new projects. If young hospitalists are interested in such projects, they should make that known to their medical directors.

“Having the senior person in your group make a connection with your [administrative] partner is how things get done in the community medical center,” Dr. McCoy says.

Dr. Ferrance’s HM group comprises four physicians and one nurse practitioner, so “there are plenty of QI projects to go around.”

“I would be more than happy to give them [junior staff hospitalists] any QI project they are interested in taking on,” he adds. “With medicine evolving as it does, we need to revisit processes every two to three years.” For example, drug shortages and cost increases often necessitate formulary cutbacks and the need for a change in administration protocols.

When selecting a QI project, it pays to stay ahead of the game, Dr. McCoy says. She encourages hospitalists to be aware of the next core measures and volunteer to help develop guidelines. She helped create a new protocol for inpatient tissue plasminogen activator (tPa) evaluation for acute stroke, which was a recent recommendation for stroke center certification. This approach was key in helping Williamsport retain its accreditation as a stroke center. The hospital has garnered multiple accolades from the Joint Commission, U.S. News and World Report, and other reporting agencies.

“The community setting is a much smaller world than academia,” she says. But smaller can be good for one’s career advancement. “If you hit a project out of the park and it makes your hospital look better, you can very quickly get a promotion or an increase in other opportunities. These types of projects may lead to the hospital asking, ‘Have you thought about being director of the hospital medicine group or taking a leadership role in hospital operations?’”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Community hospitals offer multiple opportunities for hospitalists to become involved in both quality assurance and quality improvement. To help steer the right approach and avoid possible missteps, it’s important to acknowledge the differences between the community and academic settings, according to two medical directors with whom we spoke.

For example, in the rural, 47-bed Riverside Tappahannock Hospital where Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, SFHM, is medical director for hospital-based quality, cost effectiveness is king.

“We live on a thin margin, and being sure we provide cost-effective care is the difference between having adequate nursing and not,” he says. It’s a critical difference from academic institutions, he notes, where “there is protected time to do QI, research, and administrative tasks.”

Dr. Ferrance advises those interested in tackling quality projects to “make sure that the project is tied to quality measures and that you’re being cognizant of the cost impact.”

Although much of the work around quality assurance and quality improvement in the community hospital setting is being tackled by nonphysician administrative partners, “those people are usually more than happy to develop a physician partner,” says Colleen A. McCoy, MD, PhD, medical director for hospital medicine at Williamsport (Pa.) Regional Medical Center, a part of the Susquehanna Health System.

“The idea is to look for quality projects where there is a quantifiable financial payoff to the hospital,” she says. That could be a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) core measure or helping to rewrite an order set for new inpatient guidelines on stroke, as Dr. McCoy did at her hospital.

First Order of Business

Dr. McCoy has been actively engaged in quality initiatives since she joined Williams-port in 2012. She cautions new hospitalists to spend the first six months at their new job developing a reputation for clinical excellence and attention to detail.

“Having a reputation that is respected clinically opens many doors,” she says. As generalists, hospitalists interact with a wider variety of staff than specialists. This leads to broad early exposure to a diverse group of decision makers in your institution. “As a hospitalist, you can get a lot of credibility in your organization much sooner than, for example, a young cardiologist or a young gastroenterologist,” she notes.

It is also important for new hospitalists to be mindful of their position in the organization and to watch how their institutions work and operate, so that when they propose a project they are not doing so from a critical standpoint.

“Unrequested input is often seen as criticism,” she says.

Dr. Ferrance agrees. “It’s always a good idea to make sure we focus on processes and not on people in the process.”

Meeting the Mark

“If you want to leapfrog into doing things quickly, you have to be very savvy about the cost impact of your quality improvement,” continues Dr. McCoy. She and Dr. Ferrance advise those just getting started to consider tackling core measures that are reported to CMS or to identify other quality improvement projects that can be financially quantified.

Early on at Riverside Tappahannock Hospital, Dr. Ferrance participated in root cause analyses and developed (at that time) paper-based standard order sets with quality measures attached to them.

Because of her attention to detail during her orientation at Williamsport, Dr. McCoy, who had been a clinical instructor at Emory University and worked for Kaiser Permanente, quickly spotted some necessary omissions regarding DVT prophylaxis. She helped rewrite the ICU admission order sets, inserting a query for DVT prophylaxis. That one intervention helped to increase compliance on a CMS core measure.

Assess Advancement Ops

Is your community hospital open to QI projects? Dr. McCoy says candidates should ask direct questions during job interviews to assess a prospective employer’s approach to quality. She suggests two fair questions:

- Is it possible, within my first two years here as a junior staff member, to participate in a QI project?

- If I were successful in that venture, is this organization open and able to give me more opportunities in that field?

It is key for the medical director to know who in the administrative organization of the hospital would really appreciate a physician partner or physician champion for new projects. If young hospitalists are interested in such projects, they should make that known to their medical directors.

“Having the senior person in your group make a connection with your [administrative] partner is how things get done in the community medical center,” Dr. McCoy says.

Dr. Ferrance’s HM group comprises four physicians and one nurse practitioner, so “there are plenty of QI projects to go around.”

“I would be more than happy to give them [junior staff hospitalists] any QI project they are interested in taking on,” he adds. “With medicine evolving as it does, we need to revisit processes every two to three years.” For example, drug shortages and cost increases often necessitate formulary cutbacks and the need for a change in administration protocols.

When selecting a QI project, it pays to stay ahead of the game, Dr. McCoy says. She encourages hospitalists to be aware of the next core measures and volunteer to help develop guidelines. She helped create a new protocol for inpatient tissue plasminogen activator (tPa) evaluation for acute stroke, which was a recent recommendation for stroke center certification. This approach was key in helping Williamsport retain its accreditation as a stroke center. The hospital has garnered multiple accolades from the Joint Commission, U.S. News and World Report, and other reporting agencies.

“The community setting is a much smaller world than academia,” she says. But smaller can be good for one’s career advancement. “If you hit a project out of the park and it makes your hospital look better, you can very quickly get a promotion or an increase in other opportunities. These types of projects may lead to the hospital asking, ‘Have you thought about being director of the hospital medicine group or taking a leadership role in hospital operations?’”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Community hospitals offer multiple opportunities for hospitalists to become involved in both quality assurance and quality improvement. To help steer the right approach and avoid possible missteps, it’s important to acknowledge the differences between the community and academic settings, according to two medical directors with whom we spoke.

For example, in the rural, 47-bed Riverside Tappahannock Hospital where Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, SFHM, is medical director for hospital-based quality, cost effectiveness is king.

“We live on a thin margin, and being sure we provide cost-effective care is the difference between having adequate nursing and not,” he says. It’s a critical difference from academic institutions, he notes, where “there is protected time to do QI, research, and administrative tasks.”

Dr. Ferrance advises those interested in tackling quality projects to “make sure that the project is tied to quality measures and that you’re being cognizant of the cost impact.”

Although much of the work around quality assurance and quality improvement in the community hospital setting is being tackled by nonphysician administrative partners, “those people are usually more than happy to develop a physician partner,” says Colleen A. McCoy, MD, PhD, medical director for hospital medicine at Williamsport (Pa.) Regional Medical Center, a part of the Susquehanna Health System.

“The idea is to look for quality projects where there is a quantifiable financial payoff to the hospital,” she says. That could be a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) core measure or helping to rewrite an order set for new inpatient guidelines on stroke, as Dr. McCoy did at her hospital.

First Order of Business

Dr. McCoy has been actively engaged in quality initiatives since she joined Williams-port in 2012. She cautions new hospitalists to spend the first six months at their new job developing a reputation for clinical excellence and attention to detail.

“Having a reputation that is respected clinically opens many doors,” she says. As generalists, hospitalists interact with a wider variety of staff than specialists. This leads to broad early exposure to a diverse group of decision makers in your institution. “As a hospitalist, you can get a lot of credibility in your organization much sooner than, for example, a young cardiologist or a young gastroenterologist,” she notes.

It is also important for new hospitalists to be mindful of their position in the organization and to watch how their institutions work and operate, so that when they propose a project they are not doing so from a critical standpoint.

“Unrequested input is often seen as criticism,” she says.

Dr. Ferrance agrees. “It’s always a good idea to make sure we focus on processes and not on people in the process.”

Meeting the Mark

“If you want to leapfrog into doing things quickly, you have to be very savvy about the cost impact of your quality improvement,” continues Dr. McCoy. She and Dr. Ferrance advise those just getting started to consider tackling core measures that are reported to CMS or to identify other quality improvement projects that can be financially quantified.

Early on at Riverside Tappahannock Hospital, Dr. Ferrance participated in root cause analyses and developed (at that time) paper-based standard order sets with quality measures attached to them.

Because of her attention to detail during her orientation at Williamsport, Dr. McCoy, who had been a clinical instructor at Emory University and worked for Kaiser Permanente, quickly spotted some necessary omissions regarding DVT prophylaxis. She helped rewrite the ICU admission order sets, inserting a query for DVT prophylaxis. That one intervention helped to increase compliance on a CMS core measure.

Assess Advancement Ops

Is your community hospital open to QI projects? Dr. McCoy says candidates should ask direct questions during job interviews to assess a prospective employer’s approach to quality. She suggests two fair questions:

- Is it possible, within my first two years here as a junior staff member, to participate in a QI project?

- If I were successful in that venture, is this organization open and able to give me more opportunities in that field?

It is key for the medical director to know who in the administrative organization of the hospital would really appreciate a physician partner or physician champion for new projects. If young hospitalists are interested in such projects, they should make that known to their medical directors.

“Having the senior person in your group make a connection with your [administrative] partner is how things get done in the community medical center,” Dr. McCoy says.

Dr. Ferrance’s HM group comprises four physicians and one nurse practitioner, so “there are plenty of QI projects to go around.”

“I would be more than happy to give them [junior staff hospitalists] any QI project they are interested in taking on,” he adds. “With medicine evolving as it does, we need to revisit processes every two to three years.” For example, drug shortages and cost increases often necessitate formulary cutbacks and the need for a change in administration protocols.

When selecting a QI project, it pays to stay ahead of the game, Dr. McCoy says. She encourages hospitalists to be aware of the next core measures and volunteer to help develop guidelines. She helped create a new protocol for inpatient tissue plasminogen activator (tPa) evaluation for acute stroke, which was a recent recommendation for stroke center certification. This approach was key in helping Williamsport retain its accreditation as a stroke center. The hospital has garnered multiple accolades from the Joint Commission, U.S. News and World Report, and other reporting agencies.

“The community setting is a much smaller world than academia,” she says. But smaller can be good for one’s career advancement. “If you hit a project out of the park and it makes your hospital look better, you can very quickly get a promotion or an increase in other opportunities. These types of projects may lead to the hospital asking, ‘Have you thought about being director of the hospital medicine group or taking a leadership role in hospital operations?’”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Job Search Tips for First-Time Hospitalists

The best strategy for landing that first job is to start your search early, says Cheryl DeVita, senior search consultant at Cejka Search, Inc., in St. Louis, Mo.

“Many hospital organizations planning to add to their staff are willing to consider candidates six or 12 months out,” DeVita explains. Required licensing and credentialing “don’t happen fast,” she adds, and you will not be the only applicant. To preserve your range of choices, explore options early, preferably in the fall before your residency concludes.

Tom Baudendistel, MD, FACP, program director of internal medicine residency at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., encourages his senior residents to “at least interview at new settings, and test the waters a bit.

“Too often, I see residents trying to find the absolute perfect position for the next 30 years of their career,” he says, “when in reality they are likely to change jobs in a few years for a variety of reasons, from personal to geographic to the job itself. Even if they decide to remain with Kaiser—as many do—they’ll have some perspective on what other systems are up to, which they can file away for future reference.”

At Stake? More than Money

Salary and benefits are important, but they aren’t the only factors to evaluate during a job search. Dr. Baudendistel offers a few “don’ts” to help guide the job search journey:

- Don’t forget to consider how you will stay up to date: “Residents sometimes take for granted the amount of didactic learning going on every day in the academic environment of residency, only to become disenchanted to take a job at a hospital where there may only be one grand rounds a week [if that], and the group meetings center primarily on business items, such as contracts, coding, and RVUs.”

- Don’t be lured by the money: Debt-ridden residents may be drawn to the quick fix of a nice salary, but this can cloud the fact that the salary might not increase much over the next five to 10 years, that the benefits/retirement/home loan packages are thin, or that there is very little growth potential within the group. To assess the potential for professional growth—a better predictor of job satisfaction—ask the attendings who have been with the group for five to 10 years: “How has your job evolved since you first started?” Be wary if the answer is, “I’ve been doing the same full-time clinical job since I started.”

- Don’t forget to look critically at group happiness. What is the turnover of the group? How is leadership viewed by the rank-and-file attendings? What is the relationship between the HM group and the hospital administration and nurses? A good question to ask is, “Does the group go to lunch?”

- Don’t forget to consider who your mentors will be. Who will help you grow and thrive in your job? Is there a formal mentoring program? If not, how does the group leader mentor the attendings?

The Nuts and Bolts

Once you’ve been offered a contract, it’s not just a simple matter of whether you will be salaried with benefits or a contract employee and have to purchase your own benefits. Legal counsel might be appropriate, DeVita says, to ensure you understand the ramifications of malpractice insurance.

Importantly, find out who pays for “tail insurance” for when you leave a job. This is vital, because physicians remain liable for malpractice acts performed when they were a part of the previous medical group.

You’re In, Now What?

Dr. Baudendistel and DeVita agree that honing your clinical skills will be “job one” once you start to work.

“If you’re averaging 12 patients and your peers are averaging 17, you will be in a position of jeopardy,” DeVita cautions.

For that reason, Baudendistel advises young hospitalists not to overcommit to nonclinical duties.

“There is a temptation to say ‘yes’ to every opportunity that arises in your first job. There will be plenty of time over the years to get involved in committee work, QI [quality improvement], and the like. Sometimes saying ‘no’ is the right approach in your early years,” he says.

Once you’re maintaining the same productivity level as your peers, DeVita points out, then it may be appropriate to participate in committee work—and there may be bonus components for citizenship work.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

The best strategy for landing that first job is to start your search early, says Cheryl DeVita, senior search consultant at Cejka Search, Inc., in St. Louis, Mo.

“Many hospital organizations planning to add to their staff are willing to consider candidates six or 12 months out,” DeVita explains. Required licensing and credentialing “don’t happen fast,” she adds, and you will not be the only applicant. To preserve your range of choices, explore options early, preferably in the fall before your residency concludes.

Tom Baudendistel, MD, FACP, program director of internal medicine residency at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., encourages his senior residents to “at least interview at new settings, and test the waters a bit.

“Too often, I see residents trying to find the absolute perfect position for the next 30 years of their career,” he says, “when in reality they are likely to change jobs in a few years for a variety of reasons, from personal to geographic to the job itself. Even if they decide to remain with Kaiser—as many do—they’ll have some perspective on what other systems are up to, which they can file away for future reference.”

At Stake? More than Money

Salary and benefits are important, but they aren’t the only factors to evaluate during a job search. Dr. Baudendistel offers a few “don’ts” to help guide the job search journey:

- Don’t forget to consider how you will stay up to date: “Residents sometimes take for granted the amount of didactic learning going on every day in the academic environment of residency, only to become disenchanted to take a job at a hospital where there may only be one grand rounds a week [if that], and the group meetings center primarily on business items, such as contracts, coding, and RVUs.”

- Don’t be lured by the money: Debt-ridden residents may be drawn to the quick fix of a nice salary, but this can cloud the fact that the salary might not increase much over the next five to 10 years, that the benefits/retirement/home loan packages are thin, or that there is very little growth potential within the group. To assess the potential for professional growth—a better predictor of job satisfaction—ask the attendings who have been with the group for five to 10 years: “How has your job evolved since you first started?” Be wary if the answer is, “I’ve been doing the same full-time clinical job since I started.”

- Don’t forget to look critically at group happiness. What is the turnover of the group? How is leadership viewed by the rank-and-file attendings? What is the relationship between the HM group and the hospital administration and nurses? A good question to ask is, “Does the group go to lunch?”

- Don’t forget to consider who your mentors will be. Who will help you grow and thrive in your job? Is there a formal mentoring program? If not, how does the group leader mentor the attendings?

The Nuts and Bolts

Once you’ve been offered a contract, it’s not just a simple matter of whether you will be salaried with benefits or a contract employee and have to purchase your own benefits. Legal counsel might be appropriate, DeVita says, to ensure you understand the ramifications of malpractice insurance.

Importantly, find out who pays for “tail insurance” for when you leave a job. This is vital, because physicians remain liable for malpractice acts performed when they were a part of the previous medical group.

You’re In, Now What?

Dr. Baudendistel and DeVita agree that honing your clinical skills will be “job one” once you start to work.

“If you’re averaging 12 patients and your peers are averaging 17, you will be in a position of jeopardy,” DeVita cautions.

For that reason, Baudendistel advises young hospitalists not to overcommit to nonclinical duties.

“There is a temptation to say ‘yes’ to every opportunity that arises in your first job. There will be plenty of time over the years to get involved in committee work, QI [quality improvement], and the like. Sometimes saying ‘no’ is the right approach in your early years,” he says.

Once you’re maintaining the same productivity level as your peers, DeVita points out, then it may be appropriate to participate in committee work—and there may be bonus components for citizenship work.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

The best strategy for landing that first job is to start your search early, says Cheryl DeVita, senior search consultant at Cejka Search, Inc., in St. Louis, Mo.

“Many hospital organizations planning to add to their staff are willing to consider candidates six or 12 months out,” DeVita explains. Required licensing and credentialing “don’t happen fast,” she adds, and you will not be the only applicant. To preserve your range of choices, explore options early, preferably in the fall before your residency concludes.

Tom Baudendistel, MD, FACP, program director of internal medicine residency at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., encourages his senior residents to “at least interview at new settings, and test the waters a bit.

“Too often, I see residents trying to find the absolute perfect position for the next 30 years of their career,” he says, “when in reality they are likely to change jobs in a few years for a variety of reasons, from personal to geographic to the job itself. Even if they decide to remain with Kaiser—as many do—they’ll have some perspective on what other systems are up to, which they can file away for future reference.”

At Stake? More than Money

Salary and benefits are important, but they aren’t the only factors to evaluate during a job search. Dr. Baudendistel offers a few “don’ts” to help guide the job search journey:

- Don’t forget to consider how you will stay up to date: “Residents sometimes take for granted the amount of didactic learning going on every day in the academic environment of residency, only to become disenchanted to take a job at a hospital where there may only be one grand rounds a week [if that], and the group meetings center primarily on business items, such as contracts, coding, and RVUs.”

- Don’t be lured by the money: Debt-ridden residents may be drawn to the quick fix of a nice salary, but this can cloud the fact that the salary might not increase much over the next five to 10 years, that the benefits/retirement/home loan packages are thin, or that there is very little growth potential within the group. To assess the potential for professional growth—a better predictor of job satisfaction—ask the attendings who have been with the group for five to 10 years: “How has your job evolved since you first started?” Be wary if the answer is, “I’ve been doing the same full-time clinical job since I started.”