User login

Chronic constipation: Practical approaches and novel therapies

While constipation is one of the most common symptoms managed by practicing gastroenterologists, it can also be among the most challenging. As a presenting complaint, constipation manifests with widely varying degrees of severity and may be seen in all age groups, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Its implications can include chronic and serious functional impairment as well as protracted and often excessive health care utilization. A growing number of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions have become available and proven to be effective when appropriately deployed. As such, health care providers and particularly gastroenterologists should strive to develop logical and efficient strategies for addressing this common disorder.

Clinical importance

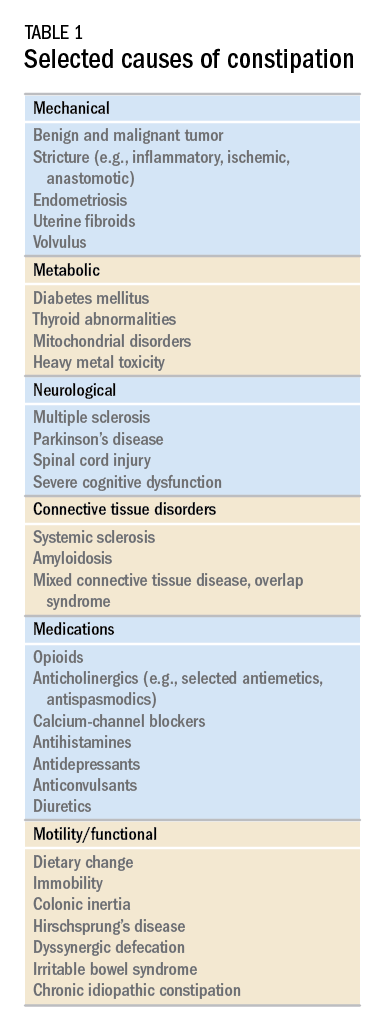

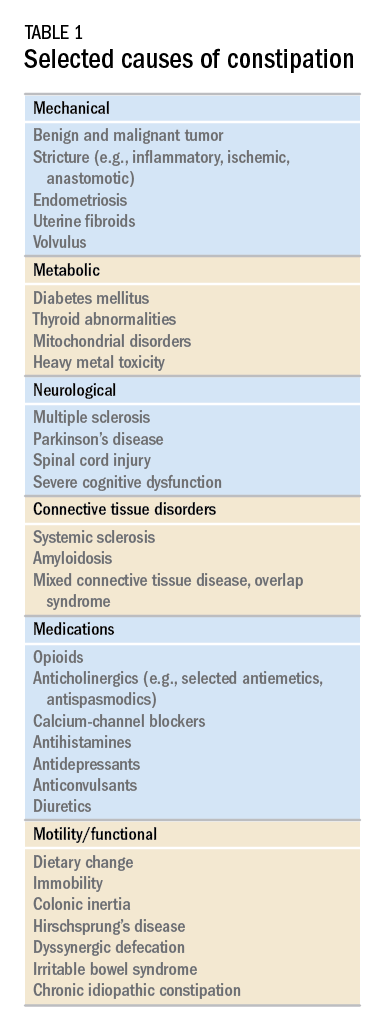

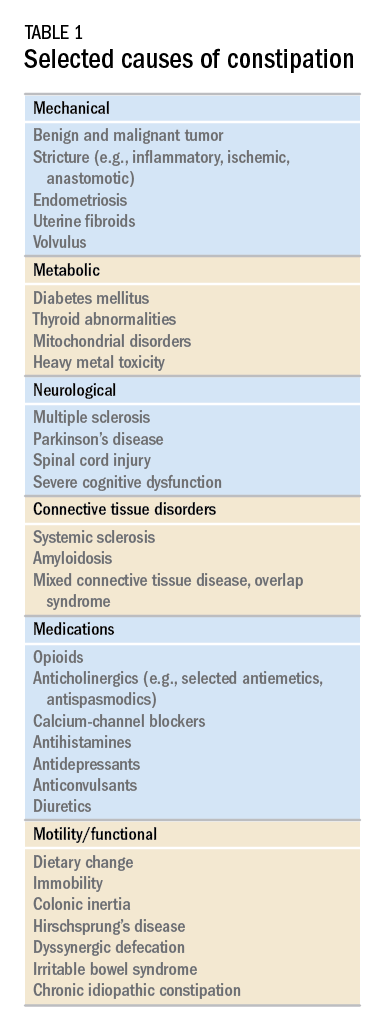

While there are a variety of etiologies for constipation (Table 1), a large proportion of chronic cases fall within the framework of functional gastrointestinal disorders, a category with a substantial burden of disease across the population. Prevalence estimates vary, but constipation likely affects between 12% and 20% of the North American population.1 Research has demonstrated significant health care expenditures associated with chronic constipation management; U.S. estimates suggest direct costs on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars per year, roughly half of which are attributable to inpatient care.2 The financial burden of constipation also includes indirect costs associated with absenteeism as well as the risks of hospitalization and invasive procedures.3

Physical and emotional complications can be likewise significant and affect all age groups, from newborns to patients in the last days of life. Hirschsprung’s disease, for example, can lead to life-threatening sequelae in infancy, such as spontaneous perforation or enterocolitis, or more prolonged functional impairments when it remains undiagnosed. Severe constipation in childhood can lead to encopresis, translating in turn into ostracism and impaired social functioning. Fecal incontinence associated with overflow diarrhea is common and debilitating, particularly in the elderly population.

The potential mechanical complications of constipation lead to its overlap with a variety of other gastrointestinal complaints. For example, the difficulties of passing inspissated stool can provoke lower gastrointestinal bleeding from irritated hemorrhoids, anal fissures, stercoral ulcers, or prolapsed rectal tissue. Retained stool can also lead to upper gastrointestinal symptoms such as postprandial bloating or early satiety.4 Delayed fecal discharge can promote an increase in fermentative microbiota, associated in turn with the production of short-chain fatty acids, methane, and other gaseous byproducts.

The initial assessment

History

Taking an appropriate history is an essential step toward achieving a successful outcome. Presenting concerns related to constipation can range from hard, infrequent, or small-volume stools; abdominal or rectal pain associated with the process of elimination; and bloating, nausea, or early satiety. A sound diagnosis requires a keen understanding of what patients mean when they indicate that they are constipated, an accurate assessment of its impact on quality of life, and a careful inventory of potentially associated complications.

It is critical to define the duration of the problem. Not infrequently, patients will focus on recent events while failing to reveal that altered bowel habits or other functional symptoms have been problematic for years. Reminding the patients to “begin at the beginning” can aid enormously in contextualizing their complaints. Individuals with longstanding symptoms and previously negative evaluations are much less likely to present with a new organic disease than are those in whom symptoms have truly arisen de novo.

Defining constipation by frequency of bowel eliminations alone has proved inaccurate at predicting actual severity. This is in part because the bowel movement frequency varies widely in healthy individuals (anywhere from thrice daily to once every 3 days) and in part because the primary indicator of effective evacuation is not frequency but volume – a much more difficult quantity for patients to gauge.5 The Bristol Stool Scale is a simple, standardized tool that more accurately evaluates the presence or absence of colonic dysfunction. For example, patients passing Type 1-2 (hard or lumpy) stools often have an element of constipation that needs to be addressed.6 However, the interpretation of stool consistency assessments is still aided by awareness of both frequency and volume. A patient passing multiple small-volume Type 6-7 (loose or watery) stools may be the most constipated, presenting with overflow or paradoxical diarrhea attributable to fecal impaction.

Physical examination

An expert physical exam is another essential aspect of the initial assessment. Alarm features can be elicited in this context as well via signs of pallor, weight loss, blood in the stool, physical abuse, or advanced psychological distress. Attention should also be paid to signs of a systemic disorder that might be associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility including previously unrecognized signs of Raynaud’s syndrome, sclerodactyly, amyloidosis, surgical scars, and joint hypermobility.7,8 Abdominal bloating, a frequently vague symptomatic complaint, can be correlated with the presence or absence of distention as perceived by the patient and/or the examiner.9

Any initial evaluation of constipation should also include a detailed digital rectal exam. A complete examination should include a careful visual assessment of the perianal region for external lesions and of the degree and directional appropriateness of pelvic floor excursion (perineal elevation and descent) during squeeze and simulated defecation maneuvers, respectively. Digital examination should include palpation for the presence or absence of pain as well as stool, blood, or masses in the rectal vault, as well as an assessment of sphincter tone at baseline, with squeeze, and with simulated defecation. Rectal pressure generation with the latter maneuver can also be qualitatively assessed. Research has suggested moderate agreement between the digital rectal examination and formal manometric evaluation in diagnosing dyssynergic defecation, underscoring the former’s utility in guiding initial management decisions.10

Testing

It is reasonable to exclude metabolic, inflammatory, or other secondary etiologies of constipation in patients in whom history or examination raises suspicion. Likewise, colonoscopy should be considered in patients with alarm features or who are due for age-appropriate screening. That said, in the absence of risk factors or ancillary signs and symptoms, a detailed diagnostic work-up is often unnecessary. The AGA’s Medical Position Statement on Constipation recommends a complete blood count as the only test to be ordered on a standard basis in the work-up of constipation.11

In patients new to one’s practice, the diligent retrieval of prior records is one of the most efficient ways to avoid wasting health care resources. Locating an old abdominal radiograph that demonstrates extensive retained stool can not only secure the diagnosis for vague symptomatic complaints but also obviate the need for more extensive testing. One should instead consider how symptom duration and the associated changes in objectives measures such as weight and laboratory parameters can be used to justify or refute the need for repeating costly or invasive studies.

It is important to consider the potential contribution of defecatory dyssynergy to chronic constipation early in a patient’s presentation, and to return to this possibility in the future if initial therapeutic interventions are unsuccessful. An abnormal qualitative assessment on digital rectal examination should trigger a more formal characterization of the patient’s defecatory mechanics via anorectal manometry (ARM) and balloon expulsion testing (BET). Likewise, a lack of response to initial pharmacotherapy should prompt suspicion for outlet dysfunction, which can be queried with functional testing even if a rectal examination is qualitatively unrevealing.

Initial approach to the chronically constipated patient

The aforementioned AGA Medical Position Statement provides a helpful algorithm regarding the diagnostic approach to constipation (Figure 1). In the absence of concern for secondary etiologies of constipation, an initial therapeutic trial of dietary, lifestyle, and medication-based intervention is reasonable for mild symptoms. Patients should be encouraged to strive for 25-30 grams of dietary fiber intake per day. For patients unable to reach this goal via high-fiber foods alone, psyllium husk is a popular supplement, but it should be initiated at modest doses to mitigate the risk of bloating. Fiber may be supplemented with the use of osmotic laxatives (e.g., polyethylene glycol) with instructions that the initial dose may be modified as needed to optimal effectiveness. Selective response to rectal therapies (e.g., bisacodyl or glycerin suppositories) over osmotic laxatives may also suggest utility in early queries of outlet dysfunction.

An abdominal radiograph can be helpful not only to diagnose constipation but also to assess the stool burden present at the time of beginning treatment. For patients presenting with a significant degree of fecal loading, an initial bowel cleanse with four liters of osmotically balanced polyethylene glycol can be a useful means of eliminating background fecal impactions that might have mitigated the effectiveness of initial therapies in the past or that might reduce the effectiveness of daily laxative therapy moving forward.

Patients with a diagnosis of defecatory dyssynergy made via ARM/BET should be referred to pelvic floor physical therapy with biofeedback. Recognizing that courses of therapy are highly individualized in practice, randomized controlled trials suggest symptom improvement in 70%-80% of patients, with the majority also demonstrating maintenance of response.12 Biofeedback appears to be an essential component of this modality based on meta-analysis data and should be requested specifically by the referring provider.13

Pharmacologic agents

For those patients with more severe initial presentations or whose symptoms persist despite initial medical management, there are several pharmacologic agents that may be considered on a prescription basis (Table 2). Linaclotide, a minimally absorbed guanylate cyclase agonist, is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) and chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC). Improvements in constipation tend to occur over a slightly shorter timeline than in abdominal pain, though both have been demonstrated in comparison to placebo.14,15 Plecanatide, a newer agent with a similar mechanism of action, has demonstrated improvements in bowel movement frequency and was recently approved for CIC.16 Lubiprostone, a chloride channel agonist, has demonstrated benefit for IBS-C and CIC as well, though its side effect profile is more varied, including dose-related nausea in up to 30% of patients.17

For patients with opioid-induced constipation who cannot wean from the opioid medications, the peripheral acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists may be quite helpful. These include injectable as well as oral formulations (e.g., methylnaltrexone and naloxegol, respectively) with additional agents under active investigation in particular clinical subsets (e.g., naldemedine for patients with cancer-related pain).18,19 Prucalopride, a selective serotonin receptor agonist, has also demonstrated benefit for constipation; it is available abroad but not yet approved for use in the United States.20 Prucalopride shares its primary mechanism of action (selective agonism of the 5HT4 serotonin receptor) with cisapride, a previously quite popular gastrointestinal motility agent that was subsequently withdrawn from the U.S. market because of arrhythmia risk.21 This risk is likely attributable to cisapride’s dual binding affinity for potassium channels, a feature that prucalopride does not share; as such, cardiotoxicity is not an active concern with the latter agent.22

Still other pharmacologic agents with novel mechanisms of action are currently under investigation. Tenapanor, an inhibitor of a particular sodium/potassium exchanger in the gut lumen, mitigates intestinal sodium absorption, which increases fluid volume and transit. A recent phase 2 study demonstrated significantly increased stool frequency relative to placebo in patients with IBS-C.23 Elobixibat, an ileal bile acid transport inhibitor, promotes colonic retention of bile acids and, in placebo-controlled studies, has led to accelerated colonic transit and an increased number of spontaneous bowel movements in patients with CIC.24

Persistent constipation

In cases of refractory constipation (in practical terms, symptoms that persist despite trials of escalating medical therapy over at least 6 weeks), it is worth revisiting the question of etiology. Querying defecatory dyssynergy via ARM/BET, if not pursued prior to trials of newer pharmacologic agents, should certainly be explored in the event that such trials fail. Inconclusive results of ARM and BET testing, or BET abnormalities that persist despite a course of physical therapy with biofeedback, may raise suspicion for pelvic organ prolapse, which may be formally evaluated with defecography. Additional testing for metabolic or structural predispositions toward constipation may also be reasonable at this juncture.

Formal colonic transit testing via radio-opaque markers, scintigraphy, or the wireless motility capsule is often inaccurate in the setting of dyssynergic defecation and should be pursued only after this entity has been excluded or successfully treated.25 While there are not many practical distinctions at present in the therapeutic management of slow-transit versus normal-transit constipation, the use of novel medications with an explicitly prokinetic mechanism of action may be reasonable to consider in the setting of a document delay in colonic transit. Such delays can also help justify further specialized diagnostic testing (e.g., colonic manometry), and, in rare refractory cases, surgical intervention.

Consideration of colectomy should be reserved for highly selected patients with delayed colonic transit, normal defecatory mechanics, and the absence of potentially explanatory background conditions (e.g., connective tissue disease). Clear evidence of an underlying colonic myopathy or neuropathy may militate in favor of a more targeted surgical intervention (e.g., subtotal colectomy) or guide one’s clinical evaluation toward alternative systemic diagnoses. A diverting loop ileostomy with interval assessment of symptoms may be useful to clarify the potential benefits of colectomy while preserving the option of operative reversal. Proximal transit delays should be definitively excluded before pursuing colonic resections given evidence that multisegment transit delays portend significantly worse postoperative outcomes.26

Conclusion

Constipation is a common, sometimes confusing presenting complaint and the variety of established and emergent options for diagnosis and therapy can lend themselves to haphazard application. Patients and providers both are well served by a clinical approach, rooted in a comprehensive history and examination, that begins to organize these options in thoughtful sequence.

Dr. Ahuja is assistant professor of clinical medicine, division of gastroenterology; Dr. Reynolds is professor of clinical medicine, and director of the program in neurogastroenterology and motility, division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

1. Higgins P.D., Johanson J.F. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Apr;99(4):750-9. PubMed PMID: 15089911.

2. Martin B.C., Barghout V., Cerulli A. Direct medical costs of constipation in the United States. Manage Care Interface. 2006 Dec;19(12):43-9. PubMed PMID: 17274481.

3. Sun S.X., Dibonaventura M., Purayidathil F.W., et al. Impact of chronic constipation on health-related quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource use: an analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Dig Dis Sc. 2011 Sep;56(9):2688-95. PubMed PMID: 21380761.

4. Heidelbaugh J.J., Stelwagon M., Miller S.A., et al. The spectrum of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: US survey assessing symptoms, care seeking, and disease burden. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Apr;110(4):580-7.

5. Mitsuhashi S., Ballou S., Jiang Z.G., et al. Characterizing normal bowel frequency and consistency in a representative sample of adults in the United States (NHANES). Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Aug 01. PubMed PMID: 28762379.

6. Saad R.J., Rao S.S., Koch K.L., et al. Do stool form and frequency correlate with whole-gut and colonic transit? Results from a multicenter study in constipated individuals and healthy controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Feb;105(2):403-11. PubMed PMID: 19888202.

7. Castori M., Morlino S., Pascolini G., et al. Gastrointestinal and nutritional issues in joint hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C, Semin Med Genet. 2015 Mar;169C(1):54-75. PubMed PMID: 25821092.

8. Nagaraja V., McMahan Z.H., Getzug T., Khanna D. Management of gastrointestinal involvement in scleroderma. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2015 Mar 01;1(1):82-105. PubMed PMID: 26005632. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4437639.

9. Malagelada J.R., Accarino A., Azpiroz F. Bloating and abdominal distension: Old misconceptions and current knowledge. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Aug;112(8):1221-31. PubMed PMID: 28508867.

10. Soh J.S., Lee H.J., Jung K.W., et al. The diagnostic value of a digital rectal examination compared with high-resolution anorectal manometry in patients with chronic constipation and fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Aug;110(8):1197-204. PubMed PMID: 26032152.

11. American Gastroenterological Association, Bharucha A.E., Dorn S.D., Lembo A., Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144(1):211-7. PubMed PMID: 23261064.

12. Skardoon G.R., Khera A.J., Emmanuel A.V., Burgell R.E. Review article: dyssynergic defaecation and biofeedback therapy in the pathophysiology and management of functional constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut. 2017 Aug;46(4):410-23. PubMed PMID: 28660663.

13. Koh C.E., Young C.J., Young J.M., Solomon M.J. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the effectiveness of biofeedback for pelvic floor dysfunction. Br J Surg. 2008 Sep;95(9):1079-87. PubMed PMID: 18655219.

14. Rao S., Lembo A.J., Shiff S.J., et al. A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Nov;107(11):1714-24; quiz p 25. PubMed PMID: 22986440. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3504311.

15. Lacy B.E., Schey R., Shiff S.J., et al. Linaclotide in chronic idiopathic constipation patients with moderate to severe abdominal bloating: A randomized, controlled trial. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0134349. PubMed PMID: 26222318. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4519259.

16. Miner P.B., Jr., Koltun W.D., Wiener G.J., et al. A randomized phase III clinical trial of plecanatide, a uroguanylin analog, in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Apr;112(4):613-21. PubMed PMID: 28169285. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5415706.

17. Johanson J.F., Drossman D.A., Panas R., Wahle A., Ueno R. Clinical trial: phase 2 study of lubiprostone for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut. 2008 Apr;27(8):685-96. PubMed PMID: 18248656.

18. Chey W.D., Webster L., Sostek M., Lappalainen J., Barker P.N., Tack J. Naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer pain. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jun 19;370(25):2387-96. PubMed PMID: 24896818.

19. Katakami N., Oda K., Tauchi K., et al. Phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of naldemedine for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jun 10;35(17):1921-8. PubMed PMID: 28445097.

20. Sajid M.S., Hebbar M., Baig M.K., Li A., Philipose Z. Use of prucalopride for chronic constipation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized, controlled trials. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Jul 30;22(3):412-22. PubMed PMID: 27127190. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4930296.

21. Quigley E.M. Cisapride: What can we learn from the rise and fall of a prokinetic? J Dig Dis. 2011 Jun;12(3):147-56. PubMed PMID: 21615867.

22. Conlon K., De Maeyer J.H., Bruce C., et al. Nonclinical cardiovascular studies of prucalopride, a highly selective 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptor agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 2017 Nov; doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.244079 [epub ahead of print].

23. Chey W.D., Lembo A.J., Rosenbaum D.P. Tenapanor treatment of patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:763-74.

24. Simren M., Bajor A., Gillberg P-G, Rudling M., Abrahamsson H. Randomised clinical trial: the ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor A3309 vs. placebo in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation – a double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Jul;34(1):41-50.

25. Zarate N., Knowles C.H., Newell M., et al. In patients with slow transit constipation, the pattern of colonic transit delay does not differentiate between those with and without impaired rectal evacuation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Feb;103(2):427-34. PubMed PMID: 18070233.

26. Redmond J.M., Smith G.W., Barofsky I., et al. Physiological tests to predict long-term outcome of total abdominal colectomy for intractable constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995 May;90(5):748-53. PubMed PMID: 7733081.

While constipation is one of the most common symptoms managed by practicing gastroenterologists, it can also be among the most challenging. As a presenting complaint, constipation manifests with widely varying degrees of severity and may be seen in all age groups, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Its implications can include chronic and serious functional impairment as well as protracted and often excessive health care utilization. A growing number of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions have become available and proven to be effective when appropriately deployed. As such, health care providers and particularly gastroenterologists should strive to develop logical and efficient strategies for addressing this common disorder.

Clinical importance

While there are a variety of etiologies for constipation (Table 1), a large proportion of chronic cases fall within the framework of functional gastrointestinal disorders, a category with a substantial burden of disease across the population. Prevalence estimates vary, but constipation likely affects between 12% and 20% of the North American population.1 Research has demonstrated significant health care expenditures associated with chronic constipation management; U.S. estimates suggest direct costs on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars per year, roughly half of which are attributable to inpatient care.2 The financial burden of constipation also includes indirect costs associated with absenteeism as well as the risks of hospitalization and invasive procedures.3

Physical and emotional complications can be likewise significant and affect all age groups, from newborns to patients in the last days of life. Hirschsprung’s disease, for example, can lead to life-threatening sequelae in infancy, such as spontaneous perforation or enterocolitis, or more prolonged functional impairments when it remains undiagnosed. Severe constipation in childhood can lead to encopresis, translating in turn into ostracism and impaired social functioning. Fecal incontinence associated with overflow diarrhea is common and debilitating, particularly in the elderly population.

The potential mechanical complications of constipation lead to its overlap with a variety of other gastrointestinal complaints. For example, the difficulties of passing inspissated stool can provoke lower gastrointestinal bleeding from irritated hemorrhoids, anal fissures, stercoral ulcers, or prolapsed rectal tissue. Retained stool can also lead to upper gastrointestinal symptoms such as postprandial bloating or early satiety.4 Delayed fecal discharge can promote an increase in fermentative microbiota, associated in turn with the production of short-chain fatty acids, methane, and other gaseous byproducts.

The initial assessment

History

Taking an appropriate history is an essential step toward achieving a successful outcome. Presenting concerns related to constipation can range from hard, infrequent, or small-volume stools; abdominal or rectal pain associated with the process of elimination; and bloating, nausea, or early satiety. A sound diagnosis requires a keen understanding of what patients mean when they indicate that they are constipated, an accurate assessment of its impact on quality of life, and a careful inventory of potentially associated complications.

It is critical to define the duration of the problem. Not infrequently, patients will focus on recent events while failing to reveal that altered bowel habits or other functional symptoms have been problematic for years. Reminding the patients to “begin at the beginning” can aid enormously in contextualizing their complaints. Individuals with longstanding symptoms and previously negative evaluations are much less likely to present with a new organic disease than are those in whom symptoms have truly arisen de novo.

Defining constipation by frequency of bowel eliminations alone has proved inaccurate at predicting actual severity. This is in part because the bowel movement frequency varies widely in healthy individuals (anywhere from thrice daily to once every 3 days) and in part because the primary indicator of effective evacuation is not frequency but volume – a much more difficult quantity for patients to gauge.5 The Bristol Stool Scale is a simple, standardized tool that more accurately evaluates the presence or absence of colonic dysfunction. For example, patients passing Type 1-2 (hard or lumpy) stools often have an element of constipation that needs to be addressed.6 However, the interpretation of stool consistency assessments is still aided by awareness of both frequency and volume. A patient passing multiple small-volume Type 6-7 (loose or watery) stools may be the most constipated, presenting with overflow or paradoxical diarrhea attributable to fecal impaction.

Physical examination

An expert physical exam is another essential aspect of the initial assessment. Alarm features can be elicited in this context as well via signs of pallor, weight loss, blood in the stool, physical abuse, or advanced psychological distress. Attention should also be paid to signs of a systemic disorder that might be associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility including previously unrecognized signs of Raynaud’s syndrome, sclerodactyly, amyloidosis, surgical scars, and joint hypermobility.7,8 Abdominal bloating, a frequently vague symptomatic complaint, can be correlated with the presence or absence of distention as perceived by the patient and/or the examiner.9

Any initial evaluation of constipation should also include a detailed digital rectal exam. A complete examination should include a careful visual assessment of the perianal region for external lesions and of the degree and directional appropriateness of pelvic floor excursion (perineal elevation and descent) during squeeze and simulated defecation maneuvers, respectively. Digital examination should include palpation for the presence or absence of pain as well as stool, blood, or masses in the rectal vault, as well as an assessment of sphincter tone at baseline, with squeeze, and with simulated defecation. Rectal pressure generation with the latter maneuver can also be qualitatively assessed. Research has suggested moderate agreement between the digital rectal examination and formal manometric evaluation in diagnosing dyssynergic defecation, underscoring the former’s utility in guiding initial management decisions.10

Testing

It is reasonable to exclude metabolic, inflammatory, or other secondary etiologies of constipation in patients in whom history or examination raises suspicion. Likewise, colonoscopy should be considered in patients with alarm features or who are due for age-appropriate screening. That said, in the absence of risk factors or ancillary signs and symptoms, a detailed diagnostic work-up is often unnecessary. The AGA’s Medical Position Statement on Constipation recommends a complete blood count as the only test to be ordered on a standard basis in the work-up of constipation.11

In patients new to one’s practice, the diligent retrieval of prior records is one of the most efficient ways to avoid wasting health care resources. Locating an old abdominal radiograph that demonstrates extensive retained stool can not only secure the diagnosis for vague symptomatic complaints but also obviate the need for more extensive testing. One should instead consider how symptom duration and the associated changes in objectives measures such as weight and laboratory parameters can be used to justify or refute the need for repeating costly or invasive studies.

It is important to consider the potential contribution of defecatory dyssynergy to chronic constipation early in a patient’s presentation, and to return to this possibility in the future if initial therapeutic interventions are unsuccessful. An abnormal qualitative assessment on digital rectal examination should trigger a more formal characterization of the patient’s defecatory mechanics via anorectal manometry (ARM) and balloon expulsion testing (BET). Likewise, a lack of response to initial pharmacotherapy should prompt suspicion for outlet dysfunction, which can be queried with functional testing even if a rectal examination is qualitatively unrevealing.

Initial approach to the chronically constipated patient

The aforementioned AGA Medical Position Statement provides a helpful algorithm regarding the diagnostic approach to constipation (Figure 1). In the absence of concern for secondary etiologies of constipation, an initial therapeutic trial of dietary, lifestyle, and medication-based intervention is reasonable for mild symptoms. Patients should be encouraged to strive for 25-30 grams of dietary fiber intake per day. For patients unable to reach this goal via high-fiber foods alone, psyllium husk is a popular supplement, but it should be initiated at modest doses to mitigate the risk of bloating. Fiber may be supplemented with the use of osmotic laxatives (e.g., polyethylene glycol) with instructions that the initial dose may be modified as needed to optimal effectiveness. Selective response to rectal therapies (e.g., bisacodyl or glycerin suppositories) over osmotic laxatives may also suggest utility in early queries of outlet dysfunction.

An abdominal radiograph can be helpful not only to diagnose constipation but also to assess the stool burden present at the time of beginning treatment. For patients presenting with a significant degree of fecal loading, an initial bowel cleanse with four liters of osmotically balanced polyethylene glycol can be a useful means of eliminating background fecal impactions that might have mitigated the effectiveness of initial therapies in the past or that might reduce the effectiveness of daily laxative therapy moving forward.

Patients with a diagnosis of defecatory dyssynergy made via ARM/BET should be referred to pelvic floor physical therapy with biofeedback. Recognizing that courses of therapy are highly individualized in practice, randomized controlled trials suggest symptom improvement in 70%-80% of patients, with the majority also demonstrating maintenance of response.12 Biofeedback appears to be an essential component of this modality based on meta-analysis data and should be requested specifically by the referring provider.13

Pharmacologic agents

For those patients with more severe initial presentations or whose symptoms persist despite initial medical management, there are several pharmacologic agents that may be considered on a prescription basis (Table 2). Linaclotide, a minimally absorbed guanylate cyclase agonist, is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) and chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC). Improvements in constipation tend to occur over a slightly shorter timeline than in abdominal pain, though both have been demonstrated in comparison to placebo.14,15 Plecanatide, a newer agent with a similar mechanism of action, has demonstrated improvements in bowel movement frequency and was recently approved for CIC.16 Lubiprostone, a chloride channel agonist, has demonstrated benefit for IBS-C and CIC as well, though its side effect profile is more varied, including dose-related nausea in up to 30% of patients.17

For patients with opioid-induced constipation who cannot wean from the opioid medications, the peripheral acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists may be quite helpful. These include injectable as well as oral formulations (e.g., methylnaltrexone and naloxegol, respectively) with additional agents under active investigation in particular clinical subsets (e.g., naldemedine for patients with cancer-related pain).18,19 Prucalopride, a selective serotonin receptor agonist, has also demonstrated benefit for constipation; it is available abroad but not yet approved for use in the United States.20 Prucalopride shares its primary mechanism of action (selective agonism of the 5HT4 serotonin receptor) with cisapride, a previously quite popular gastrointestinal motility agent that was subsequently withdrawn from the U.S. market because of arrhythmia risk.21 This risk is likely attributable to cisapride’s dual binding affinity for potassium channels, a feature that prucalopride does not share; as such, cardiotoxicity is not an active concern with the latter agent.22

Still other pharmacologic agents with novel mechanisms of action are currently under investigation. Tenapanor, an inhibitor of a particular sodium/potassium exchanger in the gut lumen, mitigates intestinal sodium absorption, which increases fluid volume and transit. A recent phase 2 study demonstrated significantly increased stool frequency relative to placebo in patients with IBS-C.23 Elobixibat, an ileal bile acid transport inhibitor, promotes colonic retention of bile acids and, in placebo-controlled studies, has led to accelerated colonic transit and an increased number of spontaneous bowel movements in patients with CIC.24

Persistent constipation

In cases of refractory constipation (in practical terms, symptoms that persist despite trials of escalating medical therapy over at least 6 weeks), it is worth revisiting the question of etiology. Querying defecatory dyssynergy via ARM/BET, if not pursued prior to trials of newer pharmacologic agents, should certainly be explored in the event that such trials fail. Inconclusive results of ARM and BET testing, or BET abnormalities that persist despite a course of physical therapy with biofeedback, may raise suspicion for pelvic organ prolapse, which may be formally evaluated with defecography. Additional testing for metabolic or structural predispositions toward constipation may also be reasonable at this juncture.

Formal colonic transit testing via radio-opaque markers, scintigraphy, or the wireless motility capsule is often inaccurate in the setting of dyssynergic defecation and should be pursued only after this entity has been excluded or successfully treated.25 While there are not many practical distinctions at present in the therapeutic management of slow-transit versus normal-transit constipation, the use of novel medications with an explicitly prokinetic mechanism of action may be reasonable to consider in the setting of a document delay in colonic transit. Such delays can also help justify further specialized diagnostic testing (e.g., colonic manometry), and, in rare refractory cases, surgical intervention.

Consideration of colectomy should be reserved for highly selected patients with delayed colonic transit, normal defecatory mechanics, and the absence of potentially explanatory background conditions (e.g., connective tissue disease). Clear evidence of an underlying colonic myopathy or neuropathy may militate in favor of a more targeted surgical intervention (e.g., subtotal colectomy) or guide one’s clinical evaluation toward alternative systemic diagnoses. A diverting loop ileostomy with interval assessment of symptoms may be useful to clarify the potential benefits of colectomy while preserving the option of operative reversal. Proximal transit delays should be definitively excluded before pursuing colonic resections given evidence that multisegment transit delays portend significantly worse postoperative outcomes.26

Conclusion

Constipation is a common, sometimes confusing presenting complaint and the variety of established and emergent options for diagnosis and therapy can lend themselves to haphazard application. Patients and providers both are well served by a clinical approach, rooted in a comprehensive history and examination, that begins to organize these options in thoughtful sequence.

Dr. Ahuja is assistant professor of clinical medicine, division of gastroenterology; Dr. Reynolds is professor of clinical medicine, and director of the program in neurogastroenterology and motility, division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

1. Higgins P.D., Johanson J.F. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Apr;99(4):750-9. PubMed PMID: 15089911.

2. Martin B.C., Barghout V., Cerulli A. Direct medical costs of constipation in the United States. Manage Care Interface. 2006 Dec;19(12):43-9. PubMed PMID: 17274481.

3. Sun S.X., Dibonaventura M., Purayidathil F.W., et al. Impact of chronic constipation on health-related quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource use: an analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Dig Dis Sc. 2011 Sep;56(9):2688-95. PubMed PMID: 21380761.

4. Heidelbaugh J.J., Stelwagon M., Miller S.A., et al. The spectrum of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: US survey assessing symptoms, care seeking, and disease burden. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Apr;110(4):580-7.

5. Mitsuhashi S., Ballou S., Jiang Z.G., et al. Characterizing normal bowel frequency and consistency in a representative sample of adults in the United States (NHANES). Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Aug 01. PubMed PMID: 28762379.

6. Saad R.J., Rao S.S., Koch K.L., et al. Do stool form and frequency correlate with whole-gut and colonic transit? Results from a multicenter study in constipated individuals and healthy controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Feb;105(2):403-11. PubMed PMID: 19888202.

7. Castori M., Morlino S., Pascolini G., et al. Gastrointestinal and nutritional issues in joint hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C, Semin Med Genet. 2015 Mar;169C(1):54-75. PubMed PMID: 25821092.

8. Nagaraja V., McMahan Z.H., Getzug T., Khanna D. Management of gastrointestinal involvement in scleroderma. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2015 Mar 01;1(1):82-105. PubMed PMID: 26005632. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4437639.

9. Malagelada J.R., Accarino A., Azpiroz F. Bloating and abdominal distension: Old misconceptions and current knowledge. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Aug;112(8):1221-31. PubMed PMID: 28508867.

10. Soh J.S., Lee H.J., Jung K.W., et al. The diagnostic value of a digital rectal examination compared with high-resolution anorectal manometry in patients with chronic constipation and fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Aug;110(8):1197-204. PubMed PMID: 26032152.

11. American Gastroenterological Association, Bharucha A.E., Dorn S.D., Lembo A., Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144(1):211-7. PubMed PMID: 23261064.

12. Skardoon G.R., Khera A.J., Emmanuel A.V., Burgell R.E. Review article: dyssynergic defaecation and biofeedback therapy in the pathophysiology and management of functional constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut. 2017 Aug;46(4):410-23. PubMed PMID: 28660663.

13. Koh C.E., Young C.J., Young J.M., Solomon M.J. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the effectiveness of biofeedback for pelvic floor dysfunction. Br J Surg. 2008 Sep;95(9):1079-87. PubMed PMID: 18655219.

14. Rao S., Lembo A.J., Shiff S.J., et al. A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Nov;107(11):1714-24; quiz p 25. PubMed PMID: 22986440. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3504311.

15. Lacy B.E., Schey R., Shiff S.J., et al. Linaclotide in chronic idiopathic constipation patients with moderate to severe abdominal bloating: A randomized, controlled trial. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0134349. PubMed PMID: 26222318. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4519259.

16. Miner P.B., Jr., Koltun W.D., Wiener G.J., et al. A randomized phase III clinical trial of plecanatide, a uroguanylin analog, in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Apr;112(4):613-21. PubMed PMID: 28169285. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5415706.

17. Johanson J.F., Drossman D.A., Panas R., Wahle A., Ueno R. Clinical trial: phase 2 study of lubiprostone for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut. 2008 Apr;27(8):685-96. PubMed PMID: 18248656.

18. Chey W.D., Webster L., Sostek M., Lappalainen J., Barker P.N., Tack J. Naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer pain. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jun 19;370(25):2387-96. PubMed PMID: 24896818.

19. Katakami N., Oda K., Tauchi K., et al. Phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of naldemedine for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jun 10;35(17):1921-8. PubMed PMID: 28445097.

20. Sajid M.S., Hebbar M., Baig M.K., Li A., Philipose Z. Use of prucalopride for chronic constipation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized, controlled trials. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Jul 30;22(3):412-22. PubMed PMID: 27127190. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4930296.

21. Quigley E.M. Cisapride: What can we learn from the rise and fall of a prokinetic? J Dig Dis. 2011 Jun;12(3):147-56. PubMed PMID: 21615867.

22. Conlon K., De Maeyer J.H., Bruce C., et al. Nonclinical cardiovascular studies of prucalopride, a highly selective 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptor agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 2017 Nov; doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.244079 [epub ahead of print].

23. Chey W.D., Lembo A.J., Rosenbaum D.P. Tenapanor treatment of patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:763-74.

24. Simren M., Bajor A., Gillberg P-G, Rudling M., Abrahamsson H. Randomised clinical trial: the ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor A3309 vs. placebo in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation – a double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Jul;34(1):41-50.

25. Zarate N., Knowles C.H., Newell M., et al. In patients with slow transit constipation, the pattern of colonic transit delay does not differentiate between those with and without impaired rectal evacuation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Feb;103(2):427-34. PubMed PMID: 18070233.

26. Redmond J.M., Smith G.W., Barofsky I., et al. Physiological tests to predict long-term outcome of total abdominal colectomy for intractable constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995 May;90(5):748-53. PubMed PMID: 7733081.

While constipation is one of the most common symptoms managed by practicing gastroenterologists, it can also be among the most challenging. As a presenting complaint, constipation manifests with widely varying degrees of severity and may be seen in all age groups, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Its implications can include chronic and serious functional impairment as well as protracted and often excessive health care utilization. A growing number of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions have become available and proven to be effective when appropriately deployed. As such, health care providers and particularly gastroenterologists should strive to develop logical and efficient strategies for addressing this common disorder.

Clinical importance

While there are a variety of etiologies for constipation (Table 1), a large proportion of chronic cases fall within the framework of functional gastrointestinal disorders, a category with a substantial burden of disease across the population. Prevalence estimates vary, but constipation likely affects between 12% and 20% of the North American population.1 Research has demonstrated significant health care expenditures associated with chronic constipation management; U.S. estimates suggest direct costs on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars per year, roughly half of which are attributable to inpatient care.2 The financial burden of constipation also includes indirect costs associated with absenteeism as well as the risks of hospitalization and invasive procedures.3

Physical and emotional complications can be likewise significant and affect all age groups, from newborns to patients in the last days of life. Hirschsprung’s disease, for example, can lead to life-threatening sequelae in infancy, such as spontaneous perforation or enterocolitis, or more prolonged functional impairments when it remains undiagnosed. Severe constipation in childhood can lead to encopresis, translating in turn into ostracism and impaired social functioning. Fecal incontinence associated with overflow diarrhea is common and debilitating, particularly in the elderly population.

The potential mechanical complications of constipation lead to its overlap with a variety of other gastrointestinal complaints. For example, the difficulties of passing inspissated stool can provoke lower gastrointestinal bleeding from irritated hemorrhoids, anal fissures, stercoral ulcers, or prolapsed rectal tissue. Retained stool can also lead to upper gastrointestinal symptoms such as postprandial bloating or early satiety.4 Delayed fecal discharge can promote an increase in fermentative microbiota, associated in turn with the production of short-chain fatty acids, methane, and other gaseous byproducts.

The initial assessment

History

Taking an appropriate history is an essential step toward achieving a successful outcome. Presenting concerns related to constipation can range from hard, infrequent, or small-volume stools; abdominal or rectal pain associated with the process of elimination; and bloating, nausea, or early satiety. A sound diagnosis requires a keen understanding of what patients mean when they indicate that they are constipated, an accurate assessment of its impact on quality of life, and a careful inventory of potentially associated complications.

It is critical to define the duration of the problem. Not infrequently, patients will focus on recent events while failing to reveal that altered bowel habits or other functional symptoms have been problematic for years. Reminding the patients to “begin at the beginning” can aid enormously in contextualizing their complaints. Individuals with longstanding symptoms and previously negative evaluations are much less likely to present with a new organic disease than are those in whom symptoms have truly arisen de novo.

Defining constipation by frequency of bowel eliminations alone has proved inaccurate at predicting actual severity. This is in part because the bowel movement frequency varies widely in healthy individuals (anywhere from thrice daily to once every 3 days) and in part because the primary indicator of effective evacuation is not frequency but volume – a much more difficult quantity for patients to gauge.5 The Bristol Stool Scale is a simple, standardized tool that more accurately evaluates the presence or absence of colonic dysfunction. For example, patients passing Type 1-2 (hard or lumpy) stools often have an element of constipation that needs to be addressed.6 However, the interpretation of stool consistency assessments is still aided by awareness of both frequency and volume. A patient passing multiple small-volume Type 6-7 (loose or watery) stools may be the most constipated, presenting with overflow or paradoxical diarrhea attributable to fecal impaction.

Physical examination

An expert physical exam is another essential aspect of the initial assessment. Alarm features can be elicited in this context as well via signs of pallor, weight loss, blood in the stool, physical abuse, or advanced psychological distress. Attention should also be paid to signs of a systemic disorder that might be associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility including previously unrecognized signs of Raynaud’s syndrome, sclerodactyly, amyloidosis, surgical scars, and joint hypermobility.7,8 Abdominal bloating, a frequently vague symptomatic complaint, can be correlated with the presence or absence of distention as perceived by the patient and/or the examiner.9

Any initial evaluation of constipation should also include a detailed digital rectal exam. A complete examination should include a careful visual assessment of the perianal region for external lesions and of the degree and directional appropriateness of pelvic floor excursion (perineal elevation and descent) during squeeze and simulated defecation maneuvers, respectively. Digital examination should include palpation for the presence or absence of pain as well as stool, blood, or masses in the rectal vault, as well as an assessment of sphincter tone at baseline, with squeeze, and with simulated defecation. Rectal pressure generation with the latter maneuver can also be qualitatively assessed. Research has suggested moderate agreement between the digital rectal examination and formal manometric evaluation in diagnosing dyssynergic defecation, underscoring the former’s utility in guiding initial management decisions.10

Testing

It is reasonable to exclude metabolic, inflammatory, or other secondary etiologies of constipation in patients in whom history or examination raises suspicion. Likewise, colonoscopy should be considered in patients with alarm features or who are due for age-appropriate screening. That said, in the absence of risk factors or ancillary signs and symptoms, a detailed diagnostic work-up is often unnecessary. The AGA’s Medical Position Statement on Constipation recommends a complete blood count as the only test to be ordered on a standard basis in the work-up of constipation.11

In patients new to one’s practice, the diligent retrieval of prior records is one of the most efficient ways to avoid wasting health care resources. Locating an old abdominal radiograph that demonstrates extensive retained stool can not only secure the diagnosis for vague symptomatic complaints but also obviate the need for more extensive testing. One should instead consider how symptom duration and the associated changes in objectives measures such as weight and laboratory parameters can be used to justify or refute the need for repeating costly or invasive studies.

It is important to consider the potential contribution of defecatory dyssynergy to chronic constipation early in a patient’s presentation, and to return to this possibility in the future if initial therapeutic interventions are unsuccessful. An abnormal qualitative assessment on digital rectal examination should trigger a more formal characterization of the patient’s defecatory mechanics via anorectal manometry (ARM) and balloon expulsion testing (BET). Likewise, a lack of response to initial pharmacotherapy should prompt suspicion for outlet dysfunction, which can be queried with functional testing even if a rectal examination is qualitatively unrevealing.

Initial approach to the chronically constipated patient

The aforementioned AGA Medical Position Statement provides a helpful algorithm regarding the diagnostic approach to constipation (Figure 1). In the absence of concern for secondary etiologies of constipation, an initial therapeutic trial of dietary, lifestyle, and medication-based intervention is reasonable for mild symptoms. Patients should be encouraged to strive for 25-30 grams of dietary fiber intake per day. For patients unable to reach this goal via high-fiber foods alone, psyllium husk is a popular supplement, but it should be initiated at modest doses to mitigate the risk of bloating. Fiber may be supplemented with the use of osmotic laxatives (e.g., polyethylene glycol) with instructions that the initial dose may be modified as needed to optimal effectiveness. Selective response to rectal therapies (e.g., bisacodyl or glycerin suppositories) over osmotic laxatives may also suggest utility in early queries of outlet dysfunction.

An abdominal radiograph can be helpful not only to diagnose constipation but also to assess the stool burden present at the time of beginning treatment. For patients presenting with a significant degree of fecal loading, an initial bowel cleanse with four liters of osmotically balanced polyethylene glycol can be a useful means of eliminating background fecal impactions that might have mitigated the effectiveness of initial therapies in the past or that might reduce the effectiveness of daily laxative therapy moving forward.

Patients with a diagnosis of defecatory dyssynergy made via ARM/BET should be referred to pelvic floor physical therapy with biofeedback. Recognizing that courses of therapy are highly individualized in practice, randomized controlled trials suggest symptom improvement in 70%-80% of patients, with the majority also demonstrating maintenance of response.12 Biofeedback appears to be an essential component of this modality based on meta-analysis data and should be requested specifically by the referring provider.13

Pharmacologic agents

For those patients with more severe initial presentations or whose symptoms persist despite initial medical management, there are several pharmacologic agents that may be considered on a prescription basis (Table 2). Linaclotide, a minimally absorbed guanylate cyclase agonist, is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) and chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC). Improvements in constipation tend to occur over a slightly shorter timeline than in abdominal pain, though both have been demonstrated in comparison to placebo.14,15 Plecanatide, a newer agent with a similar mechanism of action, has demonstrated improvements in bowel movement frequency and was recently approved for CIC.16 Lubiprostone, a chloride channel agonist, has demonstrated benefit for IBS-C and CIC as well, though its side effect profile is more varied, including dose-related nausea in up to 30% of patients.17

For patients with opioid-induced constipation who cannot wean from the opioid medications, the peripheral acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists may be quite helpful. These include injectable as well as oral formulations (e.g., methylnaltrexone and naloxegol, respectively) with additional agents under active investigation in particular clinical subsets (e.g., naldemedine for patients with cancer-related pain).18,19 Prucalopride, a selective serotonin receptor agonist, has also demonstrated benefit for constipation; it is available abroad but not yet approved for use in the United States.20 Prucalopride shares its primary mechanism of action (selective agonism of the 5HT4 serotonin receptor) with cisapride, a previously quite popular gastrointestinal motility agent that was subsequently withdrawn from the U.S. market because of arrhythmia risk.21 This risk is likely attributable to cisapride’s dual binding affinity for potassium channels, a feature that prucalopride does not share; as such, cardiotoxicity is not an active concern with the latter agent.22

Still other pharmacologic agents with novel mechanisms of action are currently under investigation. Tenapanor, an inhibitor of a particular sodium/potassium exchanger in the gut lumen, mitigates intestinal sodium absorption, which increases fluid volume and transit. A recent phase 2 study demonstrated significantly increased stool frequency relative to placebo in patients with IBS-C.23 Elobixibat, an ileal bile acid transport inhibitor, promotes colonic retention of bile acids and, in placebo-controlled studies, has led to accelerated colonic transit and an increased number of spontaneous bowel movements in patients with CIC.24

Persistent constipation

In cases of refractory constipation (in practical terms, symptoms that persist despite trials of escalating medical therapy over at least 6 weeks), it is worth revisiting the question of etiology. Querying defecatory dyssynergy via ARM/BET, if not pursued prior to trials of newer pharmacologic agents, should certainly be explored in the event that such trials fail. Inconclusive results of ARM and BET testing, or BET abnormalities that persist despite a course of physical therapy with biofeedback, may raise suspicion for pelvic organ prolapse, which may be formally evaluated with defecography. Additional testing for metabolic or structural predispositions toward constipation may also be reasonable at this juncture.

Formal colonic transit testing via radio-opaque markers, scintigraphy, or the wireless motility capsule is often inaccurate in the setting of dyssynergic defecation and should be pursued only after this entity has been excluded or successfully treated.25 While there are not many practical distinctions at present in the therapeutic management of slow-transit versus normal-transit constipation, the use of novel medications with an explicitly prokinetic mechanism of action may be reasonable to consider in the setting of a document delay in colonic transit. Such delays can also help justify further specialized diagnostic testing (e.g., colonic manometry), and, in rare refractory cases, surgical intervention.

Consideration of colectomy should be reserved for highly selected patients with delayed colonic transit, normal defecatory mechanics, and the absence of potentially explanatory background conditions (e.g., connective tissue disease). Clear evidence of an underlying colonic myopathy or neuropathy may militate in favor of a more targeted surgical intervention (e.g., subtotal colectomy) or guide one’s clinical evaluation toward alternative systemic diagnoses. A diverting loop ileostomy with interval assessment of symptoms may be useful to clarify the potential benefits of colectomy while preserving the option of operative reversal. Proximal transit delays should be definitively excluded before pursuing colonic resections given evidence that multisegment transit delays portend significantly worse postoperative outcomes.26

Conclusion

Constipation is a common, sometimes confusing presenting complaint and the variety of established and emergent options for diagnosis and therapy can lend themselves to haphazard application. Patients and providers both are well served by a clinical approach, rooted in a comprehensive history and examination, that begins to organize these options in thoughtful sequence.

Dr. Ahuja is assistant professor of clinical medicine, division of gastroenterology; Dr. Reynolds is professor of clinical medicine, and director of the program in neurogastroenterology and motility, division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

1. Higgins P.D., Johanson J.F. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Apr;99(4):750-9. PubMed PMID: 15089911.

2. Martin B.C., Barghout V., Cerulli A. Direct medical costs of constipation in the United States. Manage Care Interface. 2006 Dec;19(12):43-9. PubMed PMID: 17274481.

3. Sun S.X., Dibonaventura M., Purayidathil F.W., et al. Impact of chronic constipation on health-related quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource use: an analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Dig Dis Sc. 2011 Sep;56(9):2688-95. PubMed PMID: 21380761.

4. Heidelbaugh J.J., Stelwagon M., Miller S.A., et al. The spectrum of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: US survey assessing symptoms, care seeking, and disease burden. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Apr;110(4):580-7.

5. Mitsuhashi S., Ballou S., Jiang Z.G., et al. Characterizing normal bowel frequency and consistency in a representative sample of adults in the United States (NHANES). Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Aug 01. PubMed PMID: 28762379.

6. Saad R.J., Rao S.S., Koch K.L., et al. Do stool form and frequency correlate with whole-gut and colonic transit? Results from a multicenter study in constipated individuals and healthy controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Feb;105(2):403-11. PubMed PMID: 19888202.

7. Castori M., Morlino S., Pascolini G., et al. Gastrointestinal and nutritional issues in joint hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C, Semin Med Genet. 2015 Mar;169C(1):54-75. PubMed PMID: 25821092.

8. Nagaraja V., McMahan Z.H., Getzug T., Khanna D. Management of gastrointestinal involvement in scleroderma. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2015 Mar 01;1(1):82-105. PubMed PMID: 26005632. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4437639.

9. Malagelada J.R., Accarino A., Azpiroz F. Bloating and abdominal distension: Old misconceptions and current knowledge. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Aug;112(8):1221-31. PubMed PMID: 28508867.

10. Soh J.S., Lee H.J., Jung K.W., et al. The diagnostic value of a digital rectal examination compared with high-resolution anorectal manometry in patients with chronic constipation and fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Aug;110(8):1197-204. PubMed PMID: 26032152.

11. American Gastroenterological Association, Bharucha A.E., Dorn S.D., Lembo A., Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144(1):211-7. PubMed PMID: 23261064.

12. Skardoon G.R., Khera A.J., Emmanuel A.V., Burgell R.E. Review article: dyssynergic defaecation and biofeedback therapy in the pathophysiology and management of functional constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut. 2017 Aug;46(4):410-23. PubMed PMID: 28660663.

13. Koh C.E., Young C.J., Young J.M., Solomon M.J. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the effectiveness of biofeedback for pelvic floor dysfunction. Br J Surg. 2008 Sep;95(9):1079-87. PubMed PMID: 18655219.

14. Rao S., Lembo A.J., Shiff S.J., et al. A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Nov;107(11):1714-24; quiz p 25. PubMed PMID: 22986440. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3504311.

15. Lacy B.E., Schey R., Shiff S.J., et al. Linaclotide in chronic idiopathic constipation patients with moderate to severe abdominal bloating: A randomized, controlled trial. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0134349. PubMed PMID: 26222318. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4519259.

16. Miner P.B., Jr., Koltun W.D., Wiener G.J., et al. A randomized phase III clinical trial of plecanatide, a uroguanylin analog, in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Apr;112(4):613-21. PubMed PMID: 28169285. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5415706.

17. Johanson J.F., Drossman D.A., Panas R., Wahle A., Ueno R. Clinical trial: phase 2 study of lubiprostone for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut. 2008 Apr;27(8):685-96. PubMed PMID: 18248656.

18. Chey W.D., Webster L., Sostek M., Lappalainen J., Barker P.N., Tack J. Naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer pain. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jun 19;370(25):2387-96. PubMed PMID: 24896818.

19. Katakami N., Oda K., Tauchi K., et al. Phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of naldemedine for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jun 10;35(17):1921-8. PubMed PMID: 28445097.

20. Sajid M.S., Hebbar M., Baig M.K., Li A., Philipose Z. Use of prucalopride for chronic constipation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized, controlled trials. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Jul 30;22(3):412-22. PubMed PMID: 27127190. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4930296.

21. Quigley E.M. Cisapride: What can we learn from the rise and fall of a prokinetic? J Dig Dis. 2011 Jun;12(3):147-56. PubMed PMID: 21615867.

22. Conlon K., De Maeyer J.H., Bruce C., et al. Nonclinical cardiovascular studies of prucalopride, a highly selective 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptor agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 2017 Nov; doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.244079 [epub ahead of print].

23. Chey W.D., Lembo A.J., Rosenbaum D.P. Tenapanor treatment of patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:763-74.

24. Simren M., Bajor A., Gillberg P-G, Rudling M., Abrahamsson H. Randomised clinical trial: the ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor A3309 vs. placebo in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation – a double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Jul;34(1):41-50.

25. Zarate N., Knowles C.H., Newell M., et al. In patients with slow transit constipation, the pattern of colonic transit delay does not differentiate between those with and without impaired rectal evacuation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Feb;103(2):427-34. PubMed PMID: 18070233.

26. Redmond J.M., Smith G.W., Barofsky I., et al. Physiological tests to predict long-term outcome of total abdominal colectomy for intractable constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995 May;90(5):748-53. PubMed PMID: 7733081.