User login

CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A common thread ties together the studies and developments highlighted here: the notion that maladaptive changes in the neurologic supply to pelvic organs may contribute to chronic pain to a greater extent than do stimuli from damaged tissue. This understanding is consistent with the general lack of any obvious relationship between the degree (i.e., volume) of tissue change in disease (e.g., endometriosis) and the intensity of associated pain. It may also open new avenues to the prevention and treatment of chronic pain.

In the future, treatments for painful conditions seen in gynecology are likely to expand beyond nonsteroidal analgesics and narcotics to include

- neuromodulatory drugs

- local anesthetics applied in novel ways

- nerve-stimulation procedures that are less invasive than methods used so far.

Furthermore, the art of treatment will involve an understanding of the most effective ways to mix and sequence these methods.

Preoperative preemptive analgesia may reduce long-term incisional pain

Mathiesen O, Moiniche S, Dahl JB. Gabapentin and post-operative pain: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review, with focus on procedure. BMC Anesthesiol. 2007;7:6.

Fassoulaki A, Stamatakis E, Petropoulos G, Siafaka I, Hassiakos D, Sarantopoulos C. Gabapentin attenuates late but not acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:136–141.

The study of preemptive analgesia over the past 20 or more years has focused almost exclusively on one goal: reducing immediate postoperative pain, usually with narcotic consumption as the primary outcome measure. Results have been mixed, with few studies showing clear and clinically meaningful benefit.

More recently, several studies have focused on what may be a more important longer-term clinical outcome measure: incisional pain long after surgery. Multiple studies document an incidence of 10% to 25% of patients reporting incisional pain long after their surgery.1 Thoracotomy, reconstructive breast procedures, and abdominal incisions have all been associated with this problem. The study by Fassoulaki and associates shows that one dose of gabapentin before abdominal hysterectomy was associated with less incisional pain a full month after surgery.

Implications for patients in chronic pain

Patients who suffer chronic pain and who undergo surgery require a higher dosage of narcotic analgesics during postoperative care than other patients might. This need is usually attributed to accelerated metabolism of the drugs, brought about by longstanding use before surgery. An alternative hypothesis that would unite these observations is that pain pathways in the central nervous system are activated when surgical trauma is inflicted and that they affect the intensity of pain after surgery. For example, if the spinal cord segments associated with the pelvic reproductive organs have been involved in conducting nociceptive (pain) signals for the months or years leading to surgery, superimposed stimulus of surgery may be less well tolerated.

This hypothesis gives rise to several tantalizing questions:

- Would preoperative medication with drugs used to treat neuropathic pain reduce both visceral and somatic components of postoperative pain?

- Would these medications, given early in the clinical course, help prevent the chronic pain associated with pelvic infection and endometriosis?

- Would this approach be an avenue to reduce long-term postoperative pain in women with chronic pain before surgery?

Observations from research into preemptive analgesia are providing the impetus for what promises to be a productive and exciting area of clinical research in the treatment of pain in a variety of clinical situations in gynecology.

In chronic pain, changes in innervation may extend to peripheral organs

Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1650–1655.

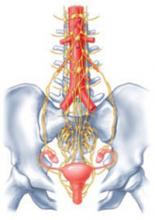

One widely accepted hypothesis is that chronic pain states are accompanied by changes in spinal cord neurophysiology at both neurochemical and neuroanatomic levels. Indeed, in animal models of chronic pain, neuronal connections are altered in the spinal cord such that touch and pressure excite true central pain fibers. New evidence suggests that changes in innervation associated with chronic pain may also affect peripheral organs (FIGURE).

For example, in the study by Atwal and associates, the uterus of women undergoing hysterectomy was stained for unmyelinated nerve fibers of the type commonly involved in visceral pain signals. Women undergoing surgery for painless conditions had a low density of pain fibers in the lower uterine segment compared with women who had chronic pain before surgery, who had a higher density of pain fibers. This was true for women who had otherwise normal pelvic anatomy, as well as for those who had endometriosis. These findings may explain the puzzling observation that hysterectomy relieves central pelvic pain in 78% of women undergoing the procedure (and improves pain in 22% of women with persistent pain) even when the uterus is histologically normal on routine pathologic examination.2

Perhaps even more intriguing is the notion that pelvic pain may ultimately be elucidated through the study of changes in neurologic systems rather than changes in gynecologic end organs themselves. If pain, initially triggered by alterations in end organs, becomes chronic and intractable by virtue of neurologic changes, this perspective may lead to entirely new approaches to preventing chronic pain.

Chronic pain may alter spinal cord neurophysiology

Under physiologic conditions, the nerves of the central nervous system guide the uterus and other organs through their respective functions. In some women, however, spinal cord neuronal circuitry becomes distorted, eliciting a pain response even when no trigger is present.

Less invasive nerve-stimulation method holds promise for pelvic pain

Nerve stimulation in a wide variety of forms has long been used to block nociceptive signals. Examples include sacral nerve root stimulators, spinal cord implants, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units. Their efficacy varies across pain syndromes, and the duration of impact (even in successfully treated women) is uncertain. The invasive nature of the implanted devices adds to the risk and often relegates them to the bottom of the list of treatment options.

Another method of peripheral nerve stimulation—posterior tibial nerve stimulation—was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of bladder irritability, and may also improve urge incontinence and pelvic pain.3,4 It involves application of electrical stimuli to a very fine (acupuncture-like) needle placed next to the posterior tibial nerve, just posterior to the medial maleolus. The nerve is generally stimulated for 30 minutes a week for a series of 12 treatments. Other protocols are bound to emerge as this method is applied more broadly.

In the case of irritability, bladder pain is also often relieved. The treatment is now being tried in women with interstitial cystitis. Even though the nerve supplies of the various pelvic and vulvar organs do not all arise from the same spinal cord segments, communications within the cord may explain the broader impact of techniques like posterior tibial nerve stimulation.

1. Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent post-surgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618-1625.

2. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Crawford DA. Hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain of presumed uterine etiology. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:676-679.

3. Congregado RB, Pena OXM, Campoy MP, Leon DE, Leal LA. Peripheral afferent nerve stimulation for treatment of lower urinary tract irritative symptoms. Eur Urol. 2004;45:65-69.

4. van Balken MR, Vandoninck V, Messelink BJ, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2003;43:158-163.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A common thread ties together the studies and developments highlighted here: the notion that maladaptive changes in the neurologic supply to pelvic organs may contribute to chronic pain to a greater extent than do stimuli from damaged tissue. This understanding is consistent with the general lack of any obvious relationship between the degree (i.e., volume) of tissue change in disease (e.g., endometriosis) and the intensity of associated pain. It may also open new avenues to the prevention and treatment of chronic pain.

In the future, treatments for painful conditions seen in gynecology are likely to expand beyond nonsteroidal analgesics and narcotics to include

- neuromodulatory drugs

- local anesthetics applied in novel ways

- nerve-stimulation procedures that are less invasive than methods used so far.

Furthermore, the art of treatment will involve an understanding of the most effective ways to mix and sequence these methods.

Preoperative preemptive analgesia may reduce long-term incisional pain

Mathiesen O, Moiniche S, Dahl JB. Gabapentin and post-operative pain: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review, with focus on procedure. BMC Anesthesiol. 2007;7:6.

Fassoulaki A, Stamatakis E, Petropoulos G, Siafaka I, Hassiakos D, Sarantopoulos C. Gabapentin attenuates late but not acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:136–141.

The study of preemptive analgesia over the past 20 or more years has focused almost exclusively on one goal: reducing immediate postoperative pain, usually with narcotic consumption as the primary outcome measure. Results have been mixed, with few studies showing clear and clinically meaningful benefit.

More recently, several studies have focused on what may be a more important longer-term clinical outcome measure: incisional pain long after surgery. Multiple studies document an incidence of 10% to 25% of patients reporting incisional pain long after their surgery.1 Thoracotomy, reconstructive breast procedures, and abdominal incisions have all been associated with this problem. The study by Fassoulaki and associates shows that one dose of gabapentin before abdominal hysterectomy was associated with less incisional pain a full month after surgery.

Implications for patients in chronic pain

Patients who suffer chronic pain and who undergo surgery require a higher dosage of narcotic analgesics during postoperative care than other patients might. This need is usually attributed to accelerated metabolism of the drugs, brought about by longstanding use before surgery. An alternative hypothesis that would unite these observations is that pain pathways in the central nervous system are activated when surgical trauma is inflicted and that they affect the intensity of pain after surgery. For example, if the spinal cord segments associated with the pelvic reproductive organs have been involved in conducting nociceptive (pain) signals for the months or years leading to surgery, superimposed stimulus of surgery may be less well tolerated.

This hypothesis gives rise to several tantalizing questions:

- Would preoperative medication with drugs used to treat neuropathic pain reduce both visceral and somatic components of postoperative pain?

- Would these medications, given early in the clinical course, help prevent the chronic pain associated with pelvic infection and endometriosis?

- Would this approach be an avenue to reduce long-term postoperative pain in women with chronic pain before surgery?

Observations from research into preemptive analgesia are providing the impetus for what promises to be a productive and exciting area of clinical research in the treatment of pain in a variety of clinical situations in gynecology.

In chronic pain, changes in innervation may extend to peripheral organs

Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1650–1655.

One widely accepted hypothesis is that chronic pain states are accompanied by changes in spinal cord neurophysiology at both neurochemical and neuroanatomic levels. Indeed, in animal models of chronic pain, neuronal connections are altered in the spinal cord such that touch and pressure excite true central pain fibers. New evidence suggests that changes in innervation associated with chronic pain may also affect peripheral organs (FIGURE).

For example, in the study by Atwal and associates, the uterus of women undergoing hysterectomy was stained for unmyelinated nerve fibers of the type commonly involved in visceral pain signals. Women undergoing surgery for painless conditions had a low density of pain fibers in the lower uterine segment compared with women who had chronic pain before surgery, who had a higher density of pain fibers. This was true for women who had otherwise normal pelvic anatomy, as well as for those who had endometriosis. These findings may explain the puzzling observation that hysterectomy relieves central pelvic pain in 78% of women undergoing the procedure (and improves pain in 22% of women with persistent pain) even when the uterus is histologically normal on routine pathologic examination.2

Perhaps even more intriguing is the notion that pelvic pain may ultimately be elucidated through the study of changes in neurologic systems rather than changes in gynecologic end organs themselves. If pain, initially triggered by alterations in end organs, becomes chronic and intractable by virtue of neurologic changes, this perspective may lead to entirely new approaches to preventing chronic pain.

Chronic pain may alter spinal cord neurophysiology

Under physiologic conditions, the nerves of the central nervous system guide the uterus and other organs through their respective functions. In some women, however, spinal cord neuronal circuitry becomes distorted, eliciting a pain response even when no trigger is present.

Less invasive nerve-stimulation method holds promise for pelvic pain

Nerve stimulation in a wide variety of forms has long been used to block nociceptive signals. Examples include sacral nerve root stimulators, spinal cord implants, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units. Their efficacy varies across pain syndromes, and the duration of impact (even in successfully treated women) is uncertain. The invasive nature of the implanted devices adds to the risk and often relegates them to the bottom of the list of treatment options.

Another method of peripheral nerve stimulation—posterior tibial nerve stimulation—was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of bladder irritability, and may also improve urge incontinence and pelvic pain.3,4 It involves application of electrical stimuli to a very fine (acupuncture-like) needle placed next to the posterior tibial nerve, just posterior to the medial maleolus. The nerve is generally stimulated for 30 minutes a week for a series of 12 treatments. Other protocols are bound to emerge as this method is applied more broadly.

In the case of irritability, bladder pain is also often relieved. The treatment is now being tried in women with interstitial cystitis. Even though the nerve supplies of the various pelvic and vulvar organs do not all arise from the same spinal cord segments, communications within the cord may explain the broader impact of techniques like posterior tibial nerve stimulation.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A common thread ties together the studies and developments highlighted here: the notion that maladaptive changes in the neurologic supply to pelvic organs may contribute to chronic pain to a greater extent than do stimuli from damaged tissue. This understanding is consistent with the general lack of any obvious relationship between the degree (i.e., volume) of tissue change in disease (e.g., endometriosis) and the intensity of associated pain. It may also open new avenues to the prevention and treatment of chronic pain.

In the future, treatments for painful conditions seen in gynecology are likely to expand beyond nonsteroidal analgesics and narcotics to include

- neuromodulatory drugs

- local anesthetics applied in novel ways

- nerve-stimulation procedures that are less invasive than methods used so far.

Furthermore, the art of treatment will involve an understanding of the most effective ways to mix and sequence these methods.

Preoperative preemptive analgesia may reduce long-term incisional pain

Mathiesen O, Moiniche S, Dahl JB. Gabapentin and post-operative pain: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review, with focus on procedure. BMC Anesthesiol. 2007;7:6.

Fassoulaki A, Stamatakis E, Petropoulos G, Siafaka I, Hassiakos D, Sarantopoulos C. Gabapentin attenuates late but not acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:136–141.

The study of preemptive analgesia over the past 20 or more years has focused almost exclusively on one goal: reducing immediate postoperative pain, usually with narcotic consumption as the primary outcome measure. Results have been mixed, with few studies showing clear and clinically meaningful benefit.

More recently, several studies have focused on what may be a more important longer-term clinical outcome measure: incisional pain long after surgery. Multiple studies document an incidence of 10% to 25% of patients reporting incisional pain long after their surgery.1 Thoracotomy, reconstructive breast procedures, and abdominal incisions have all been associated with this problem. The study by Fassoulaki and associates shows that one dose of gabapentin before abdominal hysterectomy was associated with less incisional pain a full month after surgery.

Implications for patients in chronic pain

Patients who suffer chronic pain and who undergo surgery require a higher dosage of narcotic analgesics during postoperative care than other patients might. This need is usually attributed to accelerated metabolism of the drugs, brought about by longstanding use before surgery. An alternative hypothesis that would unite these observations is that pain pathways in the central nervous system are activated when surgical trauma is inflicted and that they affect the intensity of pain after surgery. For example, if the spinal cord segments associated with the pelvic reproductive organs have been involved in conducting nociceptive (pain) signals for the months or years leading to surgery, superimposed stimulus of surgery may be less well tolerated.

This hypothesis gives rise to several tantalizing questions:

- Would preoperative medication with drugs used to treat neuropathic pain reduce both visceral and somatic components of postoperative pain?

- Would these medications, given early in the clinical course, help prevent the chronic pain associated with pelvic infection and endometriosis?

- Would this approach be an avenue to reduce long-term postoperative pain in women with chronic pain before surgery?

Observations from research into preemptive analgesia are providing the impetus for what promises to be a productive and exciting area of clinical research in the treatment of pain in a variety of clinical situations in gynecology.

In chronic pain, changes in innervation may extend to peripheral organs

Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1650–1655.

One widely accepted hypothesis is that chronic pain states are accompanied by changes in spinal cord neurophysiology at both neurochemical and neuroanatomic levels. Indeed, in animal models of chronic pain, neuronal connections are altered in the spinal cord such that touch and pressure excite true central pain fibers. New evidence suggests that changes in innervation associated with chronic pain may also affect peripheral organs (FIGURE).

For example, in the study by Atwal and associates, the uterus of women undergoing hysterectomy was stained for unmyelinated nerve fibers of the type commonly involved in visceral pain signals. Women undergoing surgery for painless conditions had a low density of pain fibers in the lower uterine segment compared with women who had chronic pain before surgery, who had a higher density of pain fibers. This was true for women who had otherwise normal pelvic anatomy, as well as for those who had endometriosis. These findings may explain the puzzling observation that hysterectomy relieves central pelvic pain in 78% of women undergoing the procedure (and improves pain in 22% of women with persistent pain) even when the uterus is histologically normal on routine pathologic examination.2

Perhaps even more intriguing is the notion that pelvic pain may ultimately be elucidated through the study of changes in neurologic systems rather than changes in gynecologic end organs themselves. If pain, initially triggered by alterations in end organs, becomes chronic and intractable by virtue of neurologic changes, this perspective may lead to entirely new approaches to preventing chronic pain.

Chronic pain may alter spinal cord neurophysiology

Under physiologic conditions, the nerves of the central nervous system guide the uterus and other organs through their respective functions. In some women, however, spinal cord neuronal circuitry becomes distorted, eliciting a pain response even when no trigger is present.

Less invasive nerve-stimulation method holds promise for pelvic pain

Nerve stimulation in a wide variety of forms has long been used to block nociceptive signals. Examples include sacral nerve root stimulators, spinal cord implants, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units. Their efficacy varies across pain syndromes, and the duration of impact (even in successfully treated women) is uncertain. The invasive nature of the implanted devices adds to the risk and often relegates them to the bottom of the list of treatment options.

Another method of peripheral nerve stimulation—posterior tibial nerve stimulation—was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of bladder irritability, and may also improve urge incontinence and pelvic pain.3,4 It involves application of electrical stimuli to a very fine (acupuncture-like) needle placed next to the posterior tibial nerve, just posterior to the medial maleolus. The nerve is generally stimulated for 30 minutes a week for a series of 12 treatments. Other protocols are bound to emerge as this method is applied more broadly.

In the case of irritability, bladder pain is also often relieved. The treatment is now being tried in women with interstitial cystitis. Even though the nerve supplies of the various pelvic and vulvar organs do not all arise from the same spinal cord segments, communications within the cord may explain the broader impact of techniques like posterior tibial nerve stimulation.

1. Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent post-surgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618-1625.

2. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Crawford DA. Hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain of presumed uterine etiology. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:676-679.

3. Congregado RB, Pena OXM, Campoy MP, Leon DE, Leal LA. Peripheral afferent nerve stimulation for treatment of lower urinary tract irritative symptoms. Eur Urol. 2004;45:65-69.

4. van Balken MR, Vandoninck V, Messelink BJ, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2003;43:158-163.

1. Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent post-surgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618-1625.

2. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Crawford DA. Hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain of presumed uterine etiology. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:676-679.

3. Congregado RB, Pena OXM, Campoy MP, Leon DE, Leal LA. Peripheral afferent nerve stimulation for treatment of lower urinary tract irritative symptoms. Eur Urol. 2004;45:65-69.

4. van Balken MR, Vandoninck V, Messelink BJ, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2003;43:158-163.

CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

Thanks to recent clinical investigation and experience, we are gaining a more complex understanding of the interactions among organ systems and the interplay between visceral and somatic structures and their contributions to pain. Understanding the interactions among these components should lead to more informed therapeutic approaches.

In this article, I focus on 2 common complaints that appear to have multiple components: vulvar vestibulitis and endometriosis.

I also explore the role of myofascial tissue in pelvic pain disorders.

Conspicuously absent from this discussion is any review of surgical technique—be it robotic, laparoscopic, or other minimally invasive surgery. As beneficial as these approaches are, in general, surgical details in the case of pelvic pain matter less than the need to integrate surgery with other aspects of treatment.

Vulvar vestibulitis is a chronic pain disorder

Zolnoun D, Hartmann K, Lamvu G, As-Sanie S, Maixner W, Steege J. A conceptual model for the pathophysiology of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61:395–401.

Erythema and hypersensitivity of the predominantly posterior vulvar vestibule are now widely recognized as a common cause of introital dyspareunia, as well as pain during daily activities. In patients with vulvar vestibulitis, a cotton-tipped applicator touched to the posterior vestibule commonly elicits allodynia (pain in response to a typically nonpainful stimulus).

Although vulvar vestibulitis often involves muscular contraction, it now seems likely that many cases labeled as vaginismus in the past were in fact more complex, attributable to what we increasingly understand as a neuroinflammatory disorder, as Zolnoun and colleagues observe. Research suggests that the pathophysiology of vulvar vestibulitis involves abnormalities in 3 interdependent systems:

- vestibular mucosa

- pelvic floor muscles

- central nervous system pain regulatory pathways.

How this view affects treatment

A modest literature search and extensive clinical experience suggest that pelvic floor muscular spasm can accompany vestibulitis, so treating the pelvic floor with biofeedback or physical therapy or both is helpful.1 The presence of muscular spasm is sometimes interpreted to mean that muscle dysfunction is the primary disorder and the vestibular response secondary, but my clinical experience favors the opposite view: Vestibulitis happens first, and then the muscles become involved. For many patients, both aspects require treatment.

Vulvar vestibulitis is now often viewed as neuropathic pain—that is, the activation of local pain fibers that appears to be strikingly out of proportion to any demonstrable tissue damage. Overnight application of 5% lidocaine to the vestibule for 4 weeks or more has substantially reduced dyspareunia.2 (Compounded preparations of pH-neutral media are often better tolerated than the commercially available medications, which tend to be mildly acidic.) A randomized, controlled trial of this approach is under way.

Multiple studies have reported high success rates (85–95%) for vestibuloplasty. Most surgeons seem to favor excision of the posterior vestibule and posterior hymeneal ring, covering the defect with the leading edge of advanced vaginal mucosa. This surgery is sometimes the first treatment for vestibulitis, but usually is a last resort after other therapies have failed.

Few clinical studies have explored nonsurgical treatments. Tricyclic antidepressants, long used to treat chronic pain in general, have proved helpful in treating generalized vulvodynia, as well as the more localized syndrome of vestibulitis.3

Anti-epileptic drugs, including gabapentin, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine, have been used in other pain disorders, and have recently met with some success when used for vestibulitis.

Success of different treatments highlights complexity of vestibulitis

At first glance, it would seem puzzling that treatment of the pelvic floor muscles, medical therapy for neuropathic pain, and surgical revision of the posterior vestibule would all be beneficial. This finding makes more sense if vestibulitis is viewed as one example of the interaction of several systems.

Early studies suggest potential overlap between interstitial cystitis and vulvar vestibulitis, and there may be an association between vestibulitis and temporomandibular joint disorder, supporting the notion that these conditions are members of a family of neurosensory disorders that share a common genetic susceptibility.4

Focus on endometriosis implants may not fully address the disease

Practice Committee, American Society for Reprodutive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with edometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:S156–S160.

Varma R, Sinha D, Gupta JK. Non-contraceptive uses of levonorgestrel-releasing hormone system—a systematic enquiry and overview. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;125:9–28.

Because endometriosis involves the ectopic presence of endometrium in the pelvis or beyond, medical and surgical treatments have traditionally targeted the implants. However, American Fertility Society staging of the disease, based on a fundamentally oncologic model (volume and distribution), is poorly predictive of the 2 major clinical morbidities of endometriosis: pain and infertility. Hence, the mechanisms of pain remain obscure.

Three aspects of endometriosis deserve comment here:

- Successful treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist does not necessarily mean endometriosis is present

- The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) eases pain, suggesting uterine involvement

- Surrounding organ systems appear to contribute to the disease.

Is a presumptive diagnosis accurate?

When treatment of pelvic pain with first-line agents such as NSAIDs or oral contraceptives fails, it is common practice to make a presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis and administer a GnRH agonist. If pain is relieved, it is assumed that endometriosis was the cause, but data do not support this conclusion. In the study most often cited in support of preemptive GnRH-agonist treatment without laparoscopic diagnosis,5 women with and without endometriosis experienced pain relief with equal frequency. The ASRM concluded in its recent guideline that relief of pelvic pain in response to a GnRH agonist does not make the diagnosis of endometriosis. This agent interrupts the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, causing hypoestrogenism and amenorrhea, and may alter pain by

- reducing contractility of intestinal muscle

- eliminating the physiologic perimenstrual rise in pain sensitivity

- quieting uterine contractions.

Evidence suggests a uterine link

According to Varma and colleagues, the easing of endometriosis-related pain with the LNG-IUS suggests that the uterus itself—as opposed to the peritoneal implants—plays an important role. (Women with chronic pelvic pain, with or without endometriosis, have increased nerve-fiber density in the lower uterine segment.6) Therefore, the benefits of progestins may be at least partly attributable to their quieting effect on uterine contractility, in addition to their direct impact on endometriosis implants, and therapies thought to target implants may relieve pain in part through their impact on the uterus.

In a randomized trial, the LNG-IUS relieved endometriosis-related pain as effectively as depot leuprolide.7 Given that this device may remain in place for 5 years, it offers substantial benefit.

What interstitial cystitis may reveal about endometriosis

Clinical evidence suggests that endometriosis and disorders of surrounding visceral systems (eg, interstitial cystitis and irritable bowel syndrome) share some morbidities. Assuming these associations are validated by epidemiologic investigations, the common denominator may be vulnerability to inflammation (or a deficit in counterinflammatory systems), nonspecific stress responses to the primary illness, genetically determined deficits in neuromodulation of nociceptive signals reaching the spinal chord,4 and other mechanisms awaiting discovery.

How myofascial tissue contributes to pelvic pain

Tu FF, As-Sanie S, Steege JF. Prevalence of pelvic musculoskeletal disorders in a female chronic pelvic pain clinic. J Reprod Med. 2006;51:185–189.

More than 20 years ago, Lipscomb and colleagues8 identified pelvic floor dysfunction as an important component of pelvic pain in women, and Slocumb9 described abdominal wall trigger points as another. We continue to gain appreciation of myofascial contributions to pelvic pain, although systematic study is lacking.

Tu and colleagues retrospectively studied the records of 987 women who presented to a chronic pelvic pain clinic for evaluation. Single-digit, intravaginal palpation revealed tenderness in the levator ani and piriformis muscles in 22% and 14% of women, respectively. Tenderness at these sites was associated with a higher total number of pain sites, previous surgery for pelvic pain, higher scores on the Beck Depression Inventory and McGill Pain Inventory, and worsening pain with bowel movements.

Muscles that are tender to palpation may, on occasion, be the prime movers in a pain syndrome, but my experience suggests that muscle problems often develop secondary to some other condition. For example, a woman with endometriosis may, over time, develop pelvic floor dysfunction as an important part of her dyspareunia, as a reaction to the tenderness in the posterior cul-de-sac. In a similar manner, muscle dysfunction may follow in the wake of pelvic infection or uterine enlargement, or after gynecologic surgery.

Suboptimal response to generally effective treatments is a common clue to the presence of myofascial and other factors. In this circumstance, rather than escalating treatment (eg, by operating repeatedly to treat endometriosis), the gynecologist should broaden the clinical inquiry by palpating the pelvic muscle groups during physical examination.

Can myofascial pain be treated?

Physical therapy has moved enthusiastically into the area of pelvic pain in general. Many clinicians and physical therapists have begun to look beyond the pelvic floor and recognize contributions from the hip external rotator muscles (piriformis, obturator), the sacroiliac joints, and the abdominal wall muscles. These muscle groups seem to communicate with each other at times. For example, palpation of the pelvic floor may refer pain to the ipsilateral lower abdominal wall, and palpation of the sacroiliac joint, which may be painful itself, may also refer pain to the corresponding anterior lower quadrant. The gynecologist can readily screen for these dysfunctions, with treatment provided by the physical therapist. Follow-up by the gynecologist then permits integration of all medical, surgical, and physical therapy.

Systematic studies are needed

At present, comparisons across treatment centers are complicated by variations in clinical assessment techniques. For example, the literature describing how the bladder contributes to pelvic pain often fails to describe assessment techniques for disorders in other systems (gastrointestinal, pelvic floor, etc). When increased bladder sensitivity is then demonstrated, the reader is left to wonder whether it is the prime mover in the problem or an epiphenomenon, secondary to some other disorder.

Dr. Steege reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91:297-306.

2. Zolnoun DA, Hartmann KE, Steege JF. Overnight 5% lidocaine ointment for treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:84-87.

3. Baggish MS, Miklos JR. Vulvar pain syndrome: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995;50:618-627.

4. Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, et al. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:135-143.

5. Ling FW. For the Pelvic Pain Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of depot leuprolide in patients with chronic pelvic pain and clinically suspected endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:51-58.

6. Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1650-1655.

7. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1993-1998.

8. Lipscomb GH, Ling FW. Chronic pelvic pain. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79:1422-1425.

9. Slocumb J. Neurological factors in chronic pelvic pain: trigger points and the abdominal pelvic pain syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149:536-543.

Thanks to recent clinical investigation and experience, we are gaining a more complex understanding of the interactions among organ systems and the interplay between visceral and somatic structures and their contributions to pain. Understanding the interactions among these components should lead to more informed therapeutic approaches.

In this article, I focus on 2 common complaints that appear to have multiple components: vulvar vestibulitis and endometriosis.

I also explore the role of myofascial tissue in pelvic pain disorders.

Conspicuously absent from this discussion is any review of surgical technique—be it robotic, laparoscopic, or other minimally invasive surgery. As beneficial as these approaches are, in general, surgical details in the case of pelvic pain matter less than the need to integrate surgery with other aspects of treatment.

Vulvar vestibulitis is a chronic pain disorder

Zolnoun D, Hartmann K, Lamvu G, As-Sanie S, Maixner W, Steege J. A conceptual model for the pathophysiology of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61:395–401.

Erythema and hypersensitivity of the predominantly posterior vulvar vestibule are now widely recognized as a common cause of introital dyspareunia, as well as pain during daily activities. In patients with vulvar vestibulitis, a cotton-tipped applicator touched to the posterior vestibule commonly elicits allodynia (pain in response to a typically nonpainful stimulus).

Although vulvar vestibulitis often involves muscular contraction, it now seems likely that many cases labeled as vaginismus in the past were in fact more complex, attributable to what we increasingly understand as a neuroinflammatory disorder, as Zolnoun and colleagues observe. Research suggests that the pathophysiology of vulvar vestibulitis involves abnormalities in 3 interdependent systems:

- vestibular mucosa

- pelvic floor muscles

- central nervous system pain regulatory pathways.

How this view affects treatment

A modest literature search and extensive clinical experience suggest that pelvic floor muscular spasm can accompany vestibulitis, so treating the pelvic floor with biofeedback or physical therapy or both is helpful.1 The presence of muscular spasm is sometimes interpreted to mean that muscle dysfunction is the primary disorder and the vestibular response secondary, but my clinical experience favors the opposite view: Vestibulitis happens first, and then the muscles become involved. For many patients, both aspects require treatment.

Vulvar vestibulitis is now often viewed as neuropathic pain—that is, the activation of local pain fibers that appears to be strikingly out of proportion to any demonstrable tissue damage. Overnight application of 5% lidocaine to the vestibule for 4 weeks or more has substantially reduced dyspareunia.2 (Compounded preparations of pH-neutral media are often better tolerated than the commercially available medications, which tend to be mildly acidic.) A randomized, controlled trial of this approach is under way.

Multiple studies have reported high success rates (85–95%) for vestibuloplasty. Most surgeons seem to favor excision of the posterior vestibule and posterior hymeneal ring, covering the defect with the leading edge of advanced vaginal mucosa. This surgery is sometimes the first treatment for vestibulitis, but usually is a last resort after other therapies have failed.

Few clinical studies have explored nonsurgical treatments. Tricyclic antidepressants, long used to treat chronic pain in general, have proved helpful in treating generalized vulvodynia, as well as the more localized syndrome of vestibulitis.3

Anti-epileptic drugs, including gabapentin, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine, have been used in other pain disorders, and have recently met with some success when used for vestibulitis.

Success of different treatments highlights complexity of vestibulitis

At first glance, it would seem puzzling that treatment of the pelvic floor muscles, medical therapy for neuropathic pain, and surgical revision of the posterior vestibule would all be beneficial. This finding makes more sense if vestibulitis is viewed as one example of the interaction of several systems.

Early studies suggest potential overlap between interstitial cystitis and vulvar vestibulitis, and there may be an association between vestibulitis and temporomandibular joint disorder, supporting the notion that these conditions are members of a family of neurosensory disorders that share a common genetic susceptibility.4

Focus on endometriosis implants may not fully address the disease

Practice Committee, American Society for Reprodutive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with edometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:S156–S160.

Varma R, Sinha D, Gupta JK. Non-contraceptive uses of levonorgestrel-releasing hormone system—a systematic enquiry and overview. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;125:9–28.

Because endometriosis involves the ectopic presence of endometrium in the pelvis or beyond, medical and surgical treatments have traditionally targeted the implants. However, American Fertility Society staging of the disease, based on a fundamentally oncologic model (volume and distribution), is poorly predictive of the 2 major clinical morbidities of endometriosis: pain and infertility. Hence, the mechanisms of pain remain obscure.

Three aspects of endometriosis deserve comment here:

- Successful treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist does not necessarily mean endometriosis is present

- The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) eases pain, suggesting uterine involvement

- Surrounding organ systems appear to contribute to the disease.

Is a presumptive diagnosis accurate?

When treatment of pelvic pain with first-line agents such as NSAIDs or oral contraceptives fails, it is common practice to make a presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis and administer a GnRH agonist. If pain is relieved, it is assumed that endometriosis was the cause, but data do not support this conclusion. In the study most often cited in support of preemptive GnRH-agonist treatment without laparoscopic diagnosis,5 women with and without endometriosis experienced pain relief with equal frequency. The ASRM concluded in its recent guideline that relief of pelvic pain in response to a GnRH agonist does not make the diagnosis of endometriosis. This agent interrupts the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, causing hypoestrogenism and amenorrhea, and may alter pain by

- reducing contractility of intestinal muscle

- eliminating the physiologic perimenstrual rise in pain sensitivity

- quieting uterine contractions.

Evidence suggests a uterine link

According to Varma and colleagues, the easing of endometriosis-related pain with the LNG-IUS suggests that the uterus itself—as opposed to the peritoneal implants—plays an important role. (Women with chronic pelvic pain, with or without endometriosis, have increased nerve-fiber density in the lower uterine segment.6) Therefore, the benefits of progestins may be at least partly attributable to their quieting effect on uterine contractility, in addition to their direct impact on endometriosis implants, and therapies thought to target implants may relieve pain in part through their impact on the uterus.

In a randomized trial, the LNG-IUS relieved endometriosis-related pain as effectively as depot leuprolide.7 Given that this device may remain in place for 5 years, it offers substantial benefit.

What interstitial cystitis may reveal about endometriosis

Clinical evidence suggests that endometriosis and disorders of surrounding visceral systems (eg, interstitial cystitis and irritable bowel syndrome) share some morbidities. Assuming these associations are validated by epidemiologic investigations, the common denominator may be vulnerability to inflammation (or a deficit in counterinflammatory systems), nonspecific stress responses to the primary illness, genetically determined deficits in neuromodulation of nociceptive signals reaching the spinal chord,4 and other mechanisms awaiting discovery.

How myofascial tissue contributes to pelvic pain

Tu FF, As-Sanie S, Steege JF. Prevalence of pelvic musculoskeletal disorders in a female chronic pelvic pain clinic. J Reprod Med. 2006;51:185–189.

More than 20 years ago, Lipscomb and colleagues8 identified pelvic floor dysfunction as an important component of pelvic pain in women, and Slocumb9 described abdominal wall trigger points as another. We continue to gain appreciation of myofascial contributions to pelvic pain, although systematic study is lacking.

Tu and colleagues retrospectively studied the records of 987 women who presented to a chronic pelvic pain clinic for evaluation. Single-digit, intravaginal palpation revealed tenderness in the levator ani and piriformis muscles in 22% and 14% of women, respectively. Tenderness at these sites was associated with a higher total number of pain sites, previous surgery for pelvic pain, higher scores on the Beck Depression Inventory and McGill Pain Inventory, and worsening pain with bowel movements.

Muscles that are tender to palpation may, on occasion, be the prime movers in a pain syndrome, but my experience suggests that muscle problems often develop secondary to some other condition. For example, a woman with endometriosis may, over time, develop pelvic floor dysfunction as an important part of her dyspareunia, as a reaction to the tenderness in the posterior cul-de-sac. In a similar manner, muscle dysfunction may follow in the wake of pelvic infection or uterine enlargement, or after gynecologic surgery.

Suboptimal response to generally effective treatments is a common clue to the presence of myofascial and other factors. In this circumstance, rather than escalating treatment (eg, by operating repeatedly to treat endometriosis), the gynecologist should broaden the clinical inquiry by palpating the pelvic muscle groups during physical examination.

Can myofascial pain be treated?

Physical therapy has moved enthusiastically into the area of pelvic pain in general. Many clinicians and physical therapists have begun to look beyond the pelvic floor and recognize contributions from the hip external rotator muscles (piriformis, obturator), the sacroiliac joints, and the abdominal wall muscles. These muscle groups seem to communicate with each other at times. For example, palpation of the pelvic floor may refer pain to the ipsilateral lower abdominal wall, and palpation of the sacroiliac joint, which may be painful itself, may also refer pain to the corresponding anterior lower quadrant. The gynecologist can readily screen for these dysfunctions, with treatment provided by the physical therapist. Follow-up by the gynecologist then permits integration of all medical, surgical, and physical therapy.

Systematic studies are needed

At present, comparisons across treatment centers are complicated by variations in clinical assessment techniques. For example, the literature describing how the bladder contributes to pelvic pain often fails to describe assessment techniques for disorders in other systems (gastrointestinal, pelvic floor, etc). When increased bladder sensitivity is then demonstrated, the reader is left to wonder whether it is the prime mover in the problem or an epiphenomenon, secondary to some other disorder.

Dr. Steege reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article.

Thanks to recent clinical investigation and experience, we are gaining a more complex understanding of the interactions among organ systems and the interplay between visceral and somatic structures and their contributions to pain. Understanding the interactions among these components should lead to more informed therapeutic approaches.

In this article, I focus on 2 common complaints that appear to have multiple components: vulvar vestibulitis and endometriosis.

I also explore the role of myofascial tissue in pelvic pain disorders.

Conspicuously absent from this discussion is any review of surgical technique—be it robotic, laparoscopic, or other minimally invasive surgery. As beneficial as these approaches are, in general, surgical details in the case of pelvic pain matter less than the need to integrate surgery with other aspects of treatment.

Vulvar vestibulitis is a chronic pain disorder

Zolnoun D, Hartmann K, Lamvu G, As-Sanie S, Maixner W, Steege J. A conceptual model for the pathophysiology of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61:395–401.

Erythema and hypersensitivity of the predominantly posterior vulvar vestibule are now widely recognized as a common cause of introital dyspareunia, as well as pain during daily activities. In patients with vulvar vestibulitis, a cotton-tipped applicator touched to the posterior vestibule commonly elicits allodynia (pain in response to a typically nonpainful stimulus).

Although vulvar vestibulitis often involves muscular contraction, it now seems likely that many cases labeled as vaginismus in the past were in fact more complex, attributable to what we increasingly understand as a neuroinflammatory disorder, as Zolnoun and colleagues observe. Research suggests that the pathophysiology of vulvar vestibulitis involves abnormalities in 3 interdependent systems:

- vestibular mucosa

- pelvic floor muscles

- central nervous system pain regulatory pathways.

How this view affects treatment

A modest literature search and extensive clinical experience suggest that pelvic floor muscular spasm can accompany vestibulitis, so treating the pelvic floor with biofeedback or physical therapy or both is helpful.1 The presence of muscular spasm is sometimes interpreted to mean that muscle dysfunction is the primary disorder and the vestibular response secondary, but my clinical experience favors the opposite view: Vestibulitis happens first, and then the muscles become involved. For many patients, both aspects require treatment.

Vulvar vestibulitis is now often viewed as neuropathic pain—that is, the activation of local pain fibers that appears to be strikingly out of proportion to any demonstrable tissue damage. Overnight application of 5% lidocaine to the vestibule for 4 weeks or more has substantially reduced dyspareunia.2 (Compounded preparations of pH-neutral media are often better tolerated than the commercially available medications, which tend to be mildly acidic.) A randomized, controlled trial of this approach is under way.

Multiple studies have reported high success rates (85–95%) for vestibuloplasty. Most surgeons seem to favor excision of the posterior vestibule and posterior hymeneal ring, covering the defect with the leading edge of advanced vaginal mucosa. This surgery is sometimes the first treatment for vestibulitis, but usually is a last resort after other therapies have failed.

Few clinical studies have explored nonsurgical treatments. Tricyclic antidepressants, long used to treat chronic pain in general, have proved helpful in treating generalized vulvodynia, as well as the more localized syndrome of vestibulitis.3

Anti-epileptic drugs, including gabapentin, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine, have been used in other pain disorders, and have recently met with some success when used for vestibulitis.

Success of different treatments highlights complexity of vestibulitis

At first glance, it would seem puzzling that treatment of the pelvic floor muscles, medical therapy for neuropathic pain, and surgical revision of the posterior vestibule would all be beneficial. This finding makes more sense if vestibulitis is viewed as one example of the interaction of several systems.

Early studies suggest potential overlap between interstitial cystitis and vulvar vestibulitis, and there may be an association between vestibulitis and temporomandibular joint disorder, supporting the notion that these conditions are members of a family of neurosensory disorders that share a common genetic susceptibility.4

Focus on endometriosis implants may not fully address the disease

Practice Committee, American Society for Reprodutive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with edometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:S156–S160.

Varma R, Sinha D, Gupta JK. Non-contraceptive uses of levonorgestrel-releasing hormone system—a systematic enquiry and overview. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;125:9–28.

Because endometriosis involves the ectopic presence of endometrium in the pelvis or beyond, medical and surgical treatments have traditionally targeted the implants. However, American Fertility Society staging of the disease, based on a fundamentally oncologic model (volume and distribution), is poorly predictive of the 2 major clinical morbidities of endometriosis: pain and infertility. Hence, the mechanisms of pain remain obscure.

Three aspects of endometriosis deserve comment here:

- Successful treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist does not necessarily mean endometriosis is present

- The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) eases pain, suggesting uterine involvement

- Surrounding organ systems appear to contribute to the disease.

Is a presumptive diagnosis accurate?

When treatment of pelvic pain with first-line agents such as NSAIDs or oral contraceptives fails, it is common practice to make a presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis and administer a GnRH agonist. If pain is relieved, it is assumed that endometriosis was the cause, but data do not support this conclusion. In the study most often cited in support of preemptive GnRH-agonist treatment without laparoscopic diagnosis,5 women with and without endometriosis experienced pain relief with equal frequency. The ASRM concluded in its recent guideline that relief of pelvic pain in response to a GnRH agonist does not make the diagnosis of endometriosis. This agent interrupts the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, causing hypoestrogenism and amenorrhea, and may alter pain by

- reducing contractility of intestinal muscle

- eliminating the physiologic perimenstrual rise in pain sensitivity

- quieting uterine contractions.

Evidence suggests a uterine link

According to Varma and colleagues, the easing of endometriosis-related pain with the LNG-IUS suggests that the uterus itself—as opposed to the peritoneal implants—plays an important role. (Women with chronic pelvic pain, with or without endometriosis, have increased nerve-fiber density in the lower uterine segment.6) Therefore, the benefits of progestins may be at least partly attributable to their quieting effect on uterine contractility, in addition to their direct impact on endometriosis implants, and therapies thought to target implants may relieve pain in part through their impact on the uterus.

In a randomized trial, the LNG-IUS relieved endometriosis-related pain as effectively as depot leuprolide.7 Given that this device may remain in place for 5 years, it offers substantial benefit.

What interstitial cystitis may reveal about endometriosis

Clinical evidence suggests that endometriosis and disorders of surrounding visceral systems (eg, interstitial cystitis and irritable bowel syndrome) share some morbidities. Assuming these associations are validated by epidemiologic investigations, the common denominator may be vulnerability to inflammation (or a deficit in counterinflammatory systems), nonspecific stress responses to the primary illness, genetically determined deficits in neuromodulation of nociceptive signals reaching the spinal chord,4 and other mechanisms awaiting discovery.

How myofascial tissue contributes to pelvic pain

Tu FF, As-Sanie S, Steege JF. Prevalence of pelvic musculoskeletal disorders in a female chronic pelvic pain clinic. J Reprod Med. 2006;51:185–189.

More than 20 years ago, Lipscomb and colleagues8 identified pelvic floor dysfunction as an important component of pelvic pain in women, and Slocumb9 described abdominal wall trigger points as another. We continue to gain appreciation of myofascial contributions to pelvic pain, although systematic study is lacking.

Tu and colleagues retrospectively studied the records of 987 women who presented to a chronic pelvic pain clinic for evaluation. Single-digit, intravaginal palpation revealed tenderness in the levator ani and piriformis muscles in 22% and 14% of women, respectively. Tenderness at these sites was associated with a higher total number of pain sites, previous surgery for pelvic pain, higher scores on the Beck Depression Inventory and McGill Pain Inventory, and worsening pain with bowel movements.

Muscles that are tender to palpation may, on occasion, be the prime movers in a pain syndrome, but my experience suggests that muscle problems often develop secondary to some other condition. For example, a woman with endometriosis may, over time, develop pelvic floor dysfunction as an important part of her dyspareunia, as a reaction to the tenderness in the posterior cul-de-sac. In a similar manner, muscle dysfunction may follow in the wake of pelvic infection or uterine enlargement, or after gynecologic surgery.

Suboptimal response to generally effective treatments is a common clue to the presence of myofascial and other factors. In this circumstance, rather than escalating treatment (eg, by operating repeatedly to treat endometriosis), the gynecologist should broaden the clinical inquiry by palpating the pelvic muscle groups during physical examination.

Can myofascial pain be treated?

Physical therapy has moved enthusiastically into the area of pelvic pain in general. Many clinicians and physical therapists have begun to look beyond the pelvic floor and recognize contributions from the hip external rotator muscles (piriformis, obturator), the sacroiliac joints, and the abdominal wall muscles. These muscle groups seem to communicate with each other at times. For example, palpation of the pelvic floor may refer pain to the ipsilateral lower abdominal wall, and palpation of the sacroiliac joint, which may be painful itself, may also refer pain to the corresponding anterior lower quadrant. The gynecologist can readily screen for these dysfunctions, with treatment provided by the physical therapist. Follow-up by the gynecologist then permits integration of all medical, surgical, and physical therapy.

Systematic studies are needed

At present, comparisons across treatment centers are complicated by variations in clinical assessment techniques. For example, the literature describing how the bladder contributes to pelvic pain often fails to describe assessment techniques for disorders in other systems (gastrointestinal, pelvic floor, etc). When increased bladder sensitivity is then demonstrated, the reader is left to wonder whether it is the prime mover in the problem or an epiphenomenon, secondary to some other disorder.

Dr. Steege reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91:297-306.

2. Zolnoun DA, Hartmann KE, Steege JF. Overnight 5% lidocaine ointment for treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:84-87.

3. Baggish MS, Miklos JR. Vulvar pain syndrome: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995;50:618-627.

4. Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, et al. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:135-143.

5. Ling FW. For the Pelvic Pain Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of depot leuprolide in patients with chronic pelvic pain and clinically suspected endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:51-58.

6. Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1650-1655.

7. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1993-1998.

8. Lipscomb GH, Ling FW. Chronic pelvic pain. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79:1422-1425.

9. Slocumb J. Neurological factors in chronic pelvic pain: trigger points and the abdominal pelvic pain syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149:536-543.

1. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91:297-306.

2. Zolnoun DA, Hartmann KE, Steege JF. Overnight 5% lidocaine ointment for treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:84-87.

3. Baggish MS, Miklos JR. Vulvar pain syndrome: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995;50:618-627.

4. Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, et al. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:135-143.

5. Ling FW. For the Pelvic Pain Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of depot leuprolide in patients with chronic pelvic pain and clinically suspected endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:51-58.

6. Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1650-1655.

7. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1993-1998.

8. Lipscomb GH, Ling FW. Chronic pelvic pain. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79:1422-1425.

9. Slocumb J. Neurological factors in chronic pelvic pain: trigger points and the abdominal pelvic pain syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149:536-543.