User login

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM's "Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program" course. Write to him at [email protected].

John Nelson: Peformance Key to Federal Value-Based Payment Modifier Plan

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

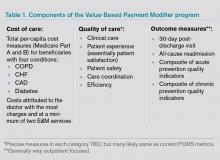

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

John Nelson: Learning CPT Coding and Documentation Tricky for Hospitalists

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

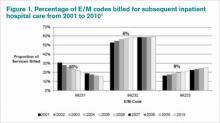

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.

To address tricky issues that come up only occasionally, several in our practice have compiled a “coding manual” by distilling guidance from our certified coders and compliance people on issues as they came up. Some issues would stump all of us, and we’d have to go to the Internet for help. All hospitalists are provided with a copy of the manual during orientation, and an electronic copy is available on the hospital’s Intranet. Topics addressed in the manual include things like how to bill the first inpatient day when a patient has changed from observation status, how to bill initial consult visits for various payors (an issue since Medicare eliminated consult codes a few years ago), how to bill when a patient is seen and discharged from the ED, etc.

Lastly, I suggest someone in your group talk with your hospital’s compliance department about its own coding and billing compliance plan. This could lead to ideas or help develop a compliance plan for your group.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.

To address tricky issues that come up only occasionally, several in our practice have compiled a “coding manual” by distilling guidance from our certified coders and compliance people on issues as they came up. Some issues would stump all of us, and we’d have to go to the Internet for help. All hospitalists are provided with a copy of the manual during orientation, and an electronic copy is available on the hospital’s Intranet. Topics addressed in the manual include things like how to bill the first inpatient day when a patient has changed from observation status, how to bill initial consult visits for various payors (an issue since Medicare eliminated consult codes a few years ago), how to bill when a patient is seen and discharged from the ED, etc.

Lastly, I suggest someone in your group talk with your hospital’s compliance department about its own coding and billing compliance plan. This could lead to ideas or help develop a compliance plan for your group.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.

To address tricky issues that come up only occasionally, several in our practice have compiled a “coding manual” by distilling guidance from our certified coders and compliance people on issues as they came up. Some issues would stump all of us, and we’d have to go to the Internet for help. All hospitalists are provided with a copy of the manual during orientation, and an electronic copy is available on the hospital’s Intranet. Topics addressed in the manual include things like how to bill the first inpatient day when a patient has changed from observation status, how to bill initial consult visits for various payors (an issue since Medicare eliminated consult codes a few years ago), how to bill when a patient is seen and discharged from the ED, etc.

Lastly, I suggest someone in your group talk with your hospital’s compliance department about its own coding and billing compliance plan. This could lead to ideas or help develop a compliance plan for your group.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

John Nelson: Post-Discharge Calls

There are lots of places to learn methods to improve patient satisfaction, including my thoughts from the January 2009 issue. Run an Internet search on “improve patient satisfaction” to get a huge number of articles, many of which have useful information and inspiration.

If you’re in a high-functioning hospitalist group, you’ve already read a lot on the topic, listened to presentations by someone at your hospital and elsewhere, and reliably reported and analyzed satisfaction survey results including HCAHPS questions and others. Maybe you’ve even engaged a consultant to help.

You might already have in place a number of strategies, such as reliably providing a business card with your photo, always sitting down in the patient’s room, asking “Is there anything else I can do?” before ending your time with a patient, etc. You’re doing all these things and more, but perhaps you’ve barely moved the needle on your satisfaction scores.

Despite your efforts, I bet your hospitalist group’s aggregate score is among the lowest of any physician group at your hospital.

You’re not alone.

What can you do about this?

High-Value Strategy: Phoning Patients after Discharge

I’m lucky enough to practice with some of the smartest, most professional, and most personable hospitalists you could ever meet. Yet our satisfaction scores are among the lowest for physicians at our hospital. Despite all of the improvement strategies we put in place over the last few years, our scores have barely budged. But that all changed once we instituted a formal program of phoning patients after discharge. That produced the largest uptick in our scores we’ve ever seen.

I can’t guarantee that our results are generalizable. But I have all the anecdotal information I need to be willing to invest the resources to make the calls. They improve scores. Likely more than any other single strategy. And they seem to have a positive effect on all survey questions, from how well the doctor explained things (nearly always the lowest of the HCAHPS scores for hospitalists) to the patient’s opinion of the hospital food.

Though initially resistant to expending the time and energy to make the calls, most in our group have said that they regularly feel really gratified by the response they get from patients or families. I think it is much better if a hospitalist who cared for the patient makes the calls, and I suspect (I have no proof) that calls made by a nurse or clerk are much less effective at improving patient satisfaction. And the call can serve as a valuable clinical encounter to briefly troubleshoot a problem or review a test result that was pending at discharge.

Simple Strategies

- More than 80% of these calls should last less than three minutes. Most patients or family members will report things are going OK and thank you profusely for the call. “No doctor has ever called before,” many will say. “Can we get you the next time Mom is hospitalized?”

- You could reduce the number of calls needed if you limit them to patients eligible for a survey; this typically is only about half of a hospitalist’s patient census. For example, patients on observation status and those discharged somewhere other than to home (e.g. to a skilled-nursing facility) are not eligible for a survey.

- It’s usually best not to tell a patient or family to expect the call. Surprising them makes them more delighted when you do call, and a patient told to expect a call but doesn’t get one will be less satisfied than if never told to expect it. Best if no one at the hospital knows you’re making the calls, because someone might brag about you and tell the patient to expect the call.

- For patients seen by several hospitalists, decide ahead of time which doctor makes the call. The doctor who discharged the patient is probably the simplest protocol.

- Develop a system to track patients who have been discharged. Every morning, we get a printout of all patients discharged the prior day. We try to call all patients the day after discharge to ensure that we reach them before they’ve had a chance to complete a satisfaction survey and before the discharging doctor rotates off.

- Develop a protocol to document the calls. Calls that lead to any new advice or therapies (e.g. see your primary-care physician sooner than planned) must be documented in the medical record, e.g., by dictating an addendum to the discharge summary. Don’t let the system get too complicated or keep you from making the calls.

- Use your judgment about whether to call the patient or just call a family member directly; it’s often better to do the latter.

- If you reach a voicemail (about 50% of the calls I make), leave a message and don’t keep calling back to reach a person.

Sample Scripts

Here are some simple scripts to use for post-discharge calls. If you reach the patient or family member:

- “This is Dr. X from Superior Hospital. I was just thinking about you/your mother/your father and wanted to know how things have gone since you/she/he left the hospital.”

- Ask about something related to the reason for their stay. “How is your appetite?” or “You haven’t had any more fever, have you?” or “Have you made your appointment with Dr. PCP yet?”

- “I hope things go really well for you, but if you ever need the hospital again, we’d be happy to care for you at Superior Hospital.”

If you get a voicemail:

- “This is Dr. X from Superior Hospital. I’ve been thinking about you/your mother/father since you/she/he left the hospital, and I am calling just to check on how things are going.” (For HIPPA reasons, don’t use the patient’s name when leaving a voicemail.)

- Mention some medical concern specific to the patient, e.g., “Your culture test turned out OK and I hope you’ve been able to get the antibiotic I prescribed.”

- “You don’t need to call me back, but if you have questions or want to provide an update, I can be reached at 555-123-4567.” (It’s very important to include this last sentence and a number where you can be reached. If omitted, many patients/families will think you must have called to convey something really important and will be distressed until able to reach you.)

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course.

There are lots of places to learn methods to improve patient satisfaction, including my thoughts from the January 2009 issue. Run an Internet search on “improve patient satisfaction” to get a huge number of articles, many of which have useful information and inspiration.

If you’re in a high-functioning hospitalist group, you’ve already read a lot on the topic, listened to presentations by someone at your hospital and elsewhere, and reliably reported and analyzed satisfaction survey results including HCAHPS questions and others. Maybe you’ve even engaged a consultant to help.

You might already have in place a number of strategies, such as reliably providing a business card with your photo, always sitting down in the patient’s room, asking “Is there anything else I can do?” before ending your time with a patient, etc. You’re doing all these things and more, but perhaps you’ve barely moved the needle on your satisfaction scores.

Despite your efforts, I bet your hospitalist group’s aggregate score is among the lowest of any physician group at your hospital.

You’re not alone.

What can you do about this?

High-Value Strategy: Phoning Patients after Discharge

I’m lucky enough to practice with some of the smartest, most professional, and most personable hospitalists you could ever meet. Yet our satisfaction scores are among the lowest for physicians at our hospital. Despite all of the improvement strategies we put in place over the last few years, our scores have barely budged. But that all changed once we instituted a formal program of phoning patients after discharge. That produced the largest uptick in our scores we’ve ever seen.

I can’t guarantee that our results are generalizable. But I have all the anecdotal information I need to be willing to invest the resources to make the calls. They improve scores. Likely more than any other single strategy. And they seem to have a positive effect on all survey questions, from how well the doctor explained things (nearly always the lowest of the HCAHPS scores for hospitalists) to the patient’s opinion of the hospital food.

Though initially resistant to expending the time and energy to make the calls, most in our group have said that they regularly feel really gratified by the response they get from patients or families. I think it is much better if a hospitalist who cared for the patient makes the calls, and I suspect (I have no proof) that calls made by a nurse or clerk are much less effective at improving patient satisfaction. And the call can serve as a valuable clinical encounter to briefly troubleshoot a problem or review a test result that was pending at discharge.

Simple Strategies

- More than 80% of these calls should last less than three minutes. Most patients or family members will report things are going OK and thank you profusely for the call. “No doctor has ever called before,” many will say. “Can we get you the next time Mom is hospitalized?”

- You could reduce the number of calls needed if you limit them to patients eligible for a survey; this typically is only about half of a hospitalist’s patient census. For example, patients on observation status and those discharged somewhere other than to home (e.g. to a skilled-nursing facility) are not eligible for a survey.

- It’s usually best not to tell a patient or family to expect the call. Surprising them makes them more delighted when you do call, and a patient told to expect a call but doesn’t get one will be less satisfied than if never told to expect it. Best if no one at the hospital knows you’re making the calls, because someone might brag about you and tell the patient to expect the call.

- For patients seen by several hospitalists, decide ahead of time which doctor makes the call. The doctor who discharged the patient is probably the simplest protocol.

- Develop a system to track patients who have been discharged. Every morning, we get a printout of all patients discharged the prior day. We try to call all patients the day after discharge to ensure that we reach them before they’ve had a chance to complete a satisfaction survey and before the discharging doctor rotates off.

- Develop a protocol to document the calls. Calls that lead to any new advice or therapies (e.g. see your primary-care physician sooner than planned) must be documented in the medical record, e.g., by dictating an addendum to the discharge summary. Don’t let the system get too complicated or keep you from making the calls.

- Use your judgment about whether to call the patient or just call a family member directly; it’s often better to do the latter.

- If you reach a voicemail (about 50% of the calls I make), leave a message and don’t keep calling back to reach a person.

Sample Scripts

Here are some simple scripts to use for post-discharge calls. If you reach the patient or family member:

- “This is Dr. X from Superior Hospital. I was just thinking about you/your mother/your father and wanted to know how things have gone since you/she/he left the hospital.”

- Ask about something related to the reason for their stay. “How is your appetite?” or “You haven’t had any more fever, have you?” or “Have you made your appointment with Dr. PCP yet?”

- “I hope things go really well for you, but if you ever need the hospital again, we’d be happy to care for you at Superior Hospital.”

If you get a voicemail:

- “This is Dr. X from Superior Hospital. I’ve been thinking about you/your mother/father since you/she/he left the hospital, and I am calling just to check on how things are going.” (For HIPPA reasons, don’t use the patient’s name when leaving a voicemail.)

- Mention some medical concern specific to the patient, e.g., “Your culture test turned out OK and I hope you’ve been able to get the antibiotic I prescribed.”

- “You don’t need to call me back, but if you have questions or want to provide an update, I can be reached at 555-123-4567.” (It’s very important to include this last sentence and a number where you can be reached. If omitted, many patients/families will think you must have called to convey something really important and will be distressed until able to reach you.)

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course.

There are lots of places to learn methods to improve patient satisfaction, including my thoughts from the January 2009 issue. Run an Internet search on “improve patient satisfaction” to get a huge number of articles, many of which have useful information and inspiration.

If you’re in a high-functioning hospitalist group, you’ve already read a lot on the topic, listened to presentations by someone at your hospital and elsewhere, and reliably reported and analyzed satisfaction survey results including HCAHPS questions and others. Maybe you’ve even engaged a consultant to help.

You might already have in place a number of strategies, such as reliably providing a business card with your photo, always sitting down in the patient’s room, asking “Is there anything else I can do?” before ending your time with a patient, etc. You’re doing all these things and more, but perhaps you’ve barely moved the needle on your satisfaction scores.

Despite your efforts, I bet your hospitalist group’s aggregate score is among the lowest of any physician group at your hospital.

You’re not alone.

What can you do about this?

High-Value Strategy: Phoning Patients after Discharge

I’m lucky enough to practice with some of the smartest, most professional, and most personable hospitalists you could ever meet. Yet our satisfaction scores are among the lowest for physicians at our hospital. Despite all of the improvement strategies we put in place over the last few years, our scores have barely budged. But that all changed once we instituted a formal program of phoning patients after discharge. That produced the largest uptick in our scores we’ve ever seen.

I can’t guarantee that our results are generalizable. But I have all the anecdotal information I need to be willing to invest the resources to make the calls. They improve scores. Likely more than any other single strategy. And they seem to have a positive effect on all survey questions, from how well the doctor explained things (nearly always the lowest of the HCAHPS scores for hospitalists) to the patient’s opinion of the hospital food.

Though initially resistant to expending the time and energy to make the calls, most in our group have said that they regularly feel really gratified by the response they get from patients or families. I think it is much better if a hospitalist who cared for the patient makes the calls, and I suspect (I have no proof) that calls made by a nurse or clerk are much less effective at improving patient satisfaction. And the call can serve as a valuable clinical encounter to briefly troubleshoot a problem or review a test result that was pending at discharge.

Simple Strategies

- More than 80% of these calls should last less than three minutes. Most patients or family members will report things are going OK and thank you profusely for the call. “No doctor has ever called before,” many will say. “Can we get you the next time Mom is hospitalized?”

- You could reduce the number of calls needed if you limit them to patients eligible for a survey; this typically is only about half of a hospitalist’s patient census. For example, patients on observation status and those discharged somewhere other than to home (e.g. to a skilled-nursing facility) are not eligible for a survey.

- It’s usually best not to tell a patient or family to expect the call. Surprising them makes them more delighted when you do call, and a patient told to expect a call but doesn’t get one will be less satisfied than if never told to expect it. Best if no one at the hospital knows you’re making the calls, because someone might brag about you and tell the patient to expect the call.

- For patients seen by several hospitalists, decide ahead of time which doctor makes the call. The doctor who discharged the patient is probably the simplest protocol.

- Develop a system to track patients who have been discharged. Every morning, we get a printout of all patients discharged the prior day. We try to call all patients the day after discharge to ensure that we reach them before they’ve had a chance to complete a satisfaction survey and before the discharging doctor rotates off.

- Develop a protocol to document the calls. Calls that lead to any new advice or therapies (e.g. see your primary-care physician sooner than planned) must be documented in the medical record, e.g., by dictating an addendum to the discharge summary. Don’t let the system get too complicated or keep you from making the calls.

- Use your judgment about whether to call the patient or just call a family member directly; it’s often better to do the latter.

- If you reach a voicemail (about 50% of the calls I make), leave a message and don’t keep calling back to reach a person.

Sample Scripts

Here are some simple scripts to use for post-discharge calls. If you reach the patient or family member:

- “This is Dr. X from Superior Hospital. I was just thinking about you/your mother/your father and wanted to know how things have gone since you/she/he left the hospital.”

- Ask about something related to the reason for their stay. “How is your appetite?” or “You haven’t had any more fever, have you?” or “Have you made your appointment with Dr. PCP yet?”

- “I hope things go really well for you, but if you ever need the hospital again, we’d be happy to care for you at Superior Hospital.”

If you get a voicemail:

- “This is Dr. X from Superior Hospital. I’ve been thinking about you/your mother/father since you/she/he left the hospital, and I am calling just to check on how things are going.” (For HIPPA reasons, don’t use the patient’s name when leaving a voicemail.)

- Mention some medical concern specific to the patient, e.g., “Your culture test turned out OK and I hope you’ve been able to get the antibiotic I prescribed.”

- “You don’t need to call me back, but if you have questions or want to provide an update, I can be reached at 555-123-4567.” (It’s very important to include this last sentence and a number where you can be reached. If omitted, many patients/families will think you must have called to convey something really important and will be distressed until able to reach you.)

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course.

John Nelson: Admit Resolution

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series.

I used last month’s column to frame the issue of disagreement between doctors over who should admit a particular patient, as well as discuss the value of good social connections to reduce the chance that divergent opinions lead to outright conflict. This month, I’ll review another worthwhile strategy—one that could be a definitive solution to these disagreements but often falls short of that goal in practice.

Service Agreements, or “Compacts,” between Physician Groups

If, at your hospital, there are reasonably frequent cases of divergent opinions regarding whether an ED admission or transfer from elsewhere should be admitted by a hospitalist or doctor in another specialty, why not meet in advance to decide this? Many hospitalist groups have held meetings with doctors in other specialties and now have a collection of agreements outlining scenarios, such as:

- ESRD patients: Hospitalist admits for non-dialysis issues (pneumonia, diabetic issues, etc.); nephrologist admits for urgent dialysis issues (K+>6.3, pH<7.3, etc.).

- Cardiology: Hospitalist admits CHF and non-ST elevation chest pain; cardiologist admits STEMI.

- General surgery: Hospitalist admits ileus, pseudo obstruction, and SBO due to adhesions; general surgery admits bowel obstruction in “virgin abdomen,” volvulus, and any obstruction thought to require urgent surgery.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting the above guidelines are evidence-based or are the right ones for your institution. I just made these up, so yours might differ significantly. I just want to provide a sense of the kinds of issues these agreements typically cover. The comanagement section of the SHM website has several documents regarding hospitalist-orthopedic service agreements.

The Negotiation Process

It’s tempting for the lead hospitalist to just have a hallway chat with a spokesperson from the other specialty, then email a draft agreement, exchange a few messages until both parties are satisfied, then email a copy of the final document to all the doctors in both groups. This might work for some simple service agreements, but for any area with significant ambiguity or disagreements (or potential for disagreements), one or more in-person meetings are usually necessary. Ideally, several doctors in both groups will attend these meetings.

Much work could be done in advance of the first meeting, including surveying other practices to see how they decide which group admits the same kinds of patents, gathering any relevant published research, and possibly drafting a “straw man” proposed agreement. When meeting in person, the doctors will have a chance to explain their points of view, needs, and concerns, and gain a greater appreciation of the way “the other guy” sees things. An important purpose of the in-person meeting is to “look the other guy in the eye” to know if he or she really is committed to following through.

Remember that written agreements like these might become an issue in malpractice suits, so you might want to have them reviewed first by risk managers. You might also write them as guidelines rather than rigid protocols that don’t allow variations.

Maximize Effectiveness

Ideally, every doctor involved in the agreement should document their approval with a signature and date. My experience is that this doesn’t happen at most places, but if there is concern about whether everyone will comply, signing the document will probably help at least a little.

The completed agreements should be provided to all doctors in both groups, the ED, affected hospital nursing units, and others. Any new doctor should get a copy of all such agreements that might be relevant. And, most important, it should be made available electronically so that it is easy to find at any time. Some agreements cover uncommon events, and the doctors on duty might not remember what the agreement said and will need ready access to it.

Most service agreements should be reviewed and updated every two or three years or as needed. If there is confusion or controversy around a particular agreement, or if disagreements about which doctor does the admission are common despite the agreement, then an in-person meeting between the physician groups should be scheduled to revise or update it.

Keep Your Fingers Crossed

If it sounds like a lot of work to develop and maintain these agreements, it is. But they’re worth every bit of that work if they reduce confusion or discord. Sadly, for several reasons, they rarely prove so effective.

One doctor might think the agreement applies, but the other doctor says this patient is an exception and the agreement doesn’t apply. It is impossible to write an agreement that addresses all possible scenarios, so a doctor can argue that any particular patient falls outside the agreement because of things like comorbidities, which service admitted the patient last time (many agreements will have defined “bounce back” intervals), which primary-care physician (PCP) the patient sees, etc.

Even if there is no dispute about whether the agreement covers a particular patient, many doctors simply don’t feel obligated to uphold the agreement. Such a doctor might tell the ED doctor: “Yep, I signed the agreement, but only as a way to get the meeting over with. I was never in favor of it and just can’t admit the patient. Call the other guy to admit.” So in spite of all the work done to create a reasonable agreement, some doctors might feel entitled to ignore it when it suits them.

Compliance Is Critical

Sadly, my take is that despite the tremendous hoped-for benefits that service agreements might provide, poor compliance means they rarely achieve their potential. Even so, they are usually worth the time and effort to create them if it leads doctors in the two specialties to schedule time away from patient care to listen to the other group’s point of view and discuss how best to handle particular types of patients. In some cases, it will be the first time the two groups of doctors have set aside time to talk about the work they do together; that alone can have significant value.

Tom Lorence, MD, a Kaiser hospitalist in Portland, Ore., who is chief of hospital medicine for Northwest Permanente, developed more than 20 service agreements with many different specialties at his institution. He has found that they are worth the effort, and that they helped allay hospitalists’ feeling of being “dumped on.”

He also told me a rule that probably applies to all such agreements in any setting: The tie goes to the hospitalist—that is, when there is reasonable uncertainty or disagreement about which group should admit a patient, it is nearly always the hospitalist who will do so.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course.

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series.

I used last month’s column to frame the issue of disagreement between doctors over who should admit a particular patient, as well as discuss the value of good social connections to reduce the chance that divergent opinions lead to outright conflict. This month, I’ll review another worthwhile strategy—one that could be a definitive solution to these disagreements but often falls short of that goal in practice.

Service Agreements, or “Compacts,” between Physician Groups

If, at your hospital, there are reasonably frequent cases of divergent opinions regarding whether an ED admission or transfer from elsewhere should be admitted by a hospitalist or doctor in another specialty, why not meet in advance to decide this? Many hospitalist groups have held meetings with doctors in other specialties and now have a collection of agreements outlining scenarios, such as:

- ESRD patients: Hospitalist admits for non-dialysis issues (pneumonia, diabetic issues, etc.); nephrologist admits for urgent dialysis issues (K+>6.3, pH<7.3, etc.).

- Cardiology: Hospitalist admits CHF and non-ST elevation chest pain; cardiologist admits STEMI.

- General surgery: Hospitalist admits ileus, pseudo obstruction, and SBO due to adhesions; general surgery admits bowel obstruction in “virgin abdomen,” volvulus, and any obstruction thought to require urgent surgery.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting the above guidelines are evidence-based or are the right ones for your institution. I just made these up, so yours might differ significantly. I just want to provide a sense of the kinds of issues these agreements typically cover. The comanagement section of the SHM website has several documents regarding hospitalist-orthopedic service agreements.

The Negotiation Process

It’s tempting for the lead hospitalist to just have a hallway chat with a spokesperson from the other specialty, then email a draft agreement, exchange a few messages until both parties are satisfied, then email a copy of the final document to all the doctors in both groups. This might work for some simple service agreements, but for any area with significant ambiguity or disagreements (or potential for disagreements), one or more in-person meetings are usually necessary. Ideally, several doctors in both groups will attend these meetings.

Much work could be done in advance of the first meeting, including surveying other practices to see how they decide which group admits the same kinds of patents, gathering any relevant published research, and possibly drafting a “straw man” proposed agreement. When meeting in person, the doctors will have a chance to explain their points of view, needs, and concerns, and gain a greater appreciation of the way “the other guy” sees things. An important purpose of the in-person meeting is to “look the other guy in the eye” to know if he or she really is committed to following through.

Remember that written agreements like these might become an issue in malpractice suits, so you might want to have them reviewed first by risk managers. You might also write them as guidelines rather than rigid protocols that don’t allow variations.

Maximize Effectiveness

Ideally, every doctor involved in the agreement should document their approval with a signature and date. My experience is that this doesn’t happen at most places, but if there is concern about whether everyone will comply, signing the document will probably help at least a little.

The completed agreements should be provided to all doctors in both groups, the ED, affected hospital nursing units, and others. Any new doctor should get a copy of all such agreements that might be relevant. And, most important, it should be made available electronically so that it is easy to find at any time. Some agreements cover uncommon events, and the doctors on duty might not remember what the agreement said and will need ready access to it.

Most service agreements should be reviewed and updated every two or three years or as needed. If there is confusion or controversy around a particular agreement, or if disagreements about which doctor does the admission are common despite the agreement, then an in-person meeting between the physician groups should be scheduled to revise or update it.

Keep Your Fingers Crossed

If it sounds like a lot of work to develop and maintain these agreements, it is. But they’re worth every bit of that work if they reduce confusion or discord. Sadly, for several reasons, they rarely prove so effective.

One doctor might think the agreement applies, but the other doctor says this patient is an exception and the agreement doesn’t apply. It is impossible to write an agreement that addresses all possible scenarios, so a doctor can argue that any particular patient falls outside the agreement because of things like comorbidities, which service admitted the patient last time (many agreements will have defined “bounce back” intervals), which primary-care physician (PCP) the patient sees, etc.

Even if there is no dispute about whether the agreement covers a particular patient, many doctors simply don’t feel obligated to uphold the agreement. Such a doctor might tell the ED doctor: “Yep, I signed the agreement, but only as a way to get the meeting over with. I was never in favor of it and just can’t admit the patient. Call the other guy to admit.” So in spite of all the work done to create a reasonable agreement, some doctors might feel entitled to ignore it when it suits them.

Compliance Is Critical

Sadly, my take is that despite the tremendous hoped-for benefits that service agreements might provide, poor compliance means they rarely achieve their potential. Even so, they are usually worth the time and effort to create them if it leads doctors in the two specialties to schedule time away from patient care to listen to the other group’s point of view and discuss how best to handle particular types of patients. In some cases, it will be the first time the two groups of doctors have set aside time to talk about the work they do together; that alone can have significant value.

Tom Lorence, MD, a Kaiser hospitalist in Portland, Ore., who is chief of hospital medicine for Northwest Permanente, developed more than 20 service agreements with many different specialties at his institution. He has found that they are worth the effort, and that they helped allay hospitalists’ feeling of being “dumped on.”

He also told me a rule that probably applies to all such agreements in any setting: The tie goes to the hospitalist—that is, when there is reasonable uncertainty or disagreement about which group should admit a patient, it is nearly always the hospitalist who will do so.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course.

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series.

I used last month’s column to frame the issue of disagreement between doctors over who should admit a particular patient, as well as discuss the value of good social connections to reduce the chance that divergent opinions lead to outright conflict. This month, I’ll review another worthwhile strategy—one that could be a definitive solution to these disagreements but often falls short of that goal in practice.

Service Agreements, or “Compacts,” between Physician Groups

If, at your hospital, there are reasonably frequent cases of divergent opinions regarding whether an ED admission or transfer from elsewhere should be admitted by a hospitalist or doctor in another specialty, why not meet in advance to decide this? Many hospitalist groups have held meetings with doctors in other specialties and now have a collection of agreements outlining scenarios, such as:

- ESRD patients: Hospitalist admits for non-dialysis issues (pneumonia, diabetic issues, etc.); nephrologist admits for urgent dialysis issues (K+>6.3, pH<7.3, etc.).

- Cardiology: Hospitalist admits CHF and non-ST elevation chest pain; cardiologist admits STEMI.

- General surgery: Hospitalist admits ileus, pseudo obstruction, and SBO due to adhesions; general surgery admits bowel obstruction in “virgin abdomen,” volvulus, and any obstruction thought to require urgent surgery.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting the above guidelines are evidence-based or are the right ones for your institution. I just made these up, so yours might differ significantly. I just want to provide a sense of the kinds of issues these agreements typically cover. The comanagement section of the SHM website has several documents regarding hospitalist-orthopedic service agreements.

The Negotiation Process

It’s tempting for the lead hospitalist to just have a hallway chat with a spokesperson from the other specialty, then email a draft agreement, exchange a few messages until both parties are satisfied, then email a copy of the final document to all the doctors in both groups. This might work for some simple service agreements, but for any area with significant ambiguity or disagreements (or potential for disagreements), one or more in-person meetings are usually necessary. Ideally, several doctors in both groups will attend these meetings.