User login

GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY

ObGyns perform most of the screening for cancers of the ovary and breast. The first cancer is especially lethal, though rare, and the second is especially feared among women. This update reviews screening guidelines and recent studies that may affect how we detect and prevent ovarian and breast cancers.

Among the findings:

- In the only multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study to date to look at the use of CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasound screening in a low-risk population of postmenopausal women in the United States, researchers found no evidence to suggest a need to revise the present (1996) ovarian cancer screening guidelines of the US Preventive Services Task Force.

- Using a Markov decision-analysis model, investigators explored the health effects of prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in women at average risk of ovarian cancer undergoing hysterectomy. They found that removing the ovaries may decrease overall survival.

- Investigators found the opposite to be true in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy greatly reduced the overall mortality rate, as well as the risk of ovarian and breast cancer.

- In a prospective cohort study of BRCA mutation carriers with no history of breast cancer who underwent prophylactic oophorectomy, researchers found the short-term use of hormone replacement therapy to be safe, with no loss of protection against breast cancer.

No need to revise screening guidelines for ovarian cancer

Buys S, Partridge E, Greene M, et al; for the PLCO Project Team. Ovarian cancer screening in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial: findings from the initial screen of a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1630–1639.

The need to identify a marker for the early detection of ovarian cancer is especially urgent, given that approximately 75% of women with the cancer present with late-stage disease. Because the disease is rare, finding a cost-effective screening test with good sensitivity and very high specificity (to decrease too many false-positive results) will be challenging.

So far, no prospective, randomized studies of any ovarian cancer screening modality have demonstrated a decrease in mortality—the gold standard of efficacy for any screening test. Therefore, the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer trial is a critical study—it is the only multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study in the United States to tackle the question of whether CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasonographic (US) screening will be effective in a low-risk population of postmenopausal women aged 55 to 74.

In this large study, 1 arm underwent ovarian cancer screening with both modalities and the other arm underwent no such screening.

This study reports on baseline, or ‘prevalent,’ cancers

This preliminary report does not comment on the efficacy of ovarian cancer screening; data on the effect of repeated annual screens on detection rates and mortality will become available over the next several years.

Rather, the purpose of this preliminary report was to detail the baseline ovarian cancer screening tests of the 39,115 women randomized to the intervention arm from November 15, 1993, to December 13, 2001. These results describe “prevalent” cancers—that is, cancers that are present on the first screen. The more important information about efficacy of screening will come over the next several years, as “incident” cancers develop.

Roughly 6% of women had at least 1 abnormal finding at baseline

Among 28,506 women with results for both baseline tests, 1,706 had at least 1 abnormal finding:

- 1,338 had an abnormal transvaginal US scan

- 402 had an abnormal level on the CA-125 test

- 34 had abnormalities in both tests

- 29 malignant neoplasms were identified in this population, 20 of them invasive.

When combined, CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasonography had good positive predictive value

In general, a positive predictive value (PPV) of more than 10% (ie, 10 surgeries to detect 1 cancer) is considered reasonable justification for a screening test. In the PLCO trial, the PPV was 4% for CA-125 alone (16 neoplasms in 402 positive screens), 1.6% for transvaginal ultrasonography alone (22 neoplasms in 1,338 positive screens), and 26.5% if both tests were abnormal (9 neoplasms in 34 positive screens).

When tumors of low malignant potential were excluded, the PPV was 3.7% for an abnormal CA-125, 1.0% for an abnormal transvaginal sonogram, and 23.5% if both tests were abnormal. A PPV of 23.5% for both tests is fairly good (ie, approximately 4 surgeries to detect 1 cancer). However, if only women in whom both screening tests were abnormal went to surgery, 12 of 20 invasive cancers would be missed.

Bottom line: Routine screening still not justified

Nothing in the findings reported here suggests that we need to revise the current (from 1996) ovarian cancer screening guidelines of the US Preventive Services Task Force,1 which state that “routine screening for ovarian cancer by US, the measurement of serum tumor markers, or pelvic examination is not recommended.”

We will need to wait until the PLCO trial results come in to see the effect of repeated annual ovarian cancer screens on detection rates and mortality.

Consider ovarian conservation in hysterectomy for benign disease

Parker W, Broder MS, Liu Z, Shoupe D, Farquhar C, Berek JS. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:219–226.

As discussed earlier, we have no good screening tool for the early detection of ovarian cancer. Although rare, ovarian cancer is a lethal, scary disease, and most ObGyns prophylactically remove the ovaries at the time of hysterectomy in most postmenopausal and many perimenopausal women.

The downside to this strategy seems low among postmenopausal women, and the upside, in terms of not having to worry about ovarian cancer, seems high. The study by Parker and colleagues, while having definite limitations, asks us to question this routine practice pattern. The authors found that prophylactic oophorectomy may be associated with decreased overall survival.

Model used SEER data, Nurses’ Health Study to predict survival

Parker and colleagues used a Markov decision-analysis model (a hypothetical mathematical model that uses published data to create cohorts of patients to estimate risk of morbidity or mortality, or both, over time) to evaluate the risks and benefits of ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Age-specific mortality estimates for ovarian cancer were based on Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) statistics.

For women at average risk of ovarian cancer, the probability of surviving to 80 years of age after hysterectomy between 50 and 54 years varied, and was 62.8% and 62.5% for ovarian conservation with and without estrogen therapy, respectively, compared with 62.2% and 53.9% for oophorectomy with and without estrogen therapy. The main reason that the model found decreased overall survival with prophylactic oophorectomy was an increase in coronary artery disease after oophorectomy—a finding that was based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study.

At the very least, think hard about the decision to remove the ovaries

This report estimated that about 300,000 prophylactic oophorectomies are carried out annually in the United States. Although this study has limitations, we believe it encourages debate and reexamination of the benefit of prophylactic oophorectomy for benign indications in young, low-risk patients.

The most important finding from the study is that oophorectomy conferred no survival advantage. Given the rarity of ovarian cancer among the general population, this effect is not that surprising.

For now, careful risk assessment remains a fundamental component of management, so that women who are at increased risk of ovarian cancer can undergo prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy.

For low-risk women, who constitute the majority of patients, the data to support removing ovaries at the time of hysterectomy are less clear.

Make sure the patient understands the low risk of cancer and possible cardiac benefits of preservation

- Conduct a thorough discussion with the patient about the pros and cons of oophorectomy for benign disease.

- The risk of ovarian cancer in the general population is low; patients should understand that they may derive cardiac protection from postmenopausal ovarian function.

Do consider oophorectomy among carriers of a BRCA mutation

Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Neuhausen SL, et al. Mortality after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:223–229.

Women known to have BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations are now managed by means of surveillance or with prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Although bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy has been shown to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer by 90% and the risk of breast cancer by 50%, until this study few data shed light on the effect of the procedure on overall mortality among women with BRCA mutations.

This prospective cohort study identified 155 patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who elected to undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and matched them by age with a control group of 271. All women were followed until death by any cause or by breast, ovarian, or primary peritoneal cancer. The women were followed for a mean of 3.1 years in the bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy group and 2.1 years in the control group.

Overall and cancer-specific survival improved with oophorectomy

Among BRCA mutation carriers, women who chose prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy had improved overall and cancer-specific survival, compared with women who did not undergo the surgery.

In the analysis of the matched BRCA mutation carriers, women who chose to undergo the procedure had a decreased risk of overall mortality (hazard ratio [HR]=0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08–0.71); they also had a decreased risk of mortality due to both breast cancer (HR=0.1; 95% CI, 0.02–0.71) and ovarian cancer (HR=0.05; 95% CI, 0.01–0.46).

Practice recommendations

Apparently, unlike women at average risk of ovarian cancer (for whom prophylactic oophorectomy in conjunction with hysterectomy for benign disease may be associated with decreased overall survival; see the review of the study by Parker and colleagues), women with BRCA mutations may benefit from oophorectomy.

Advantages of prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in this patient population should be discussed with potential surgical candidates, because:

- Women who have a BRCA mutation and who have had bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were shown to have improved overall and cancer-specific survival.

- In this specific group of BRCA mutation carriers, this study did not demonstrate an increased risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, or other causes associated with premature menopause from bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

In BRCA carriers, HRT after oophorectomy does not raise breast cancer risk

Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al; for the PROSE Study Group. Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7804–7810.

In women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, the risk of ovarian cancer is staggering (20% to 40% for BRCA1 mutations, 15% to 25% for BRCA2 mutations), and prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the only strategy proven to significantly reduce risk. A second important benefit for bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy among premenopausal mutation carriers is that the procedure decreases the risk of breast cancer by 50%. In women who have a lifetime risk of breast cancer that is as high as 80%, this benefit is extremely welcome. Current recommendations are for women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations to undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at age 35 to 40, or when child-bearing is complete.

Yet, for many women in this age group, quality of life is substantially altered when premature menopause kicks in after the surgery. Most ObGyns feel comfortable giving short-term hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to premenopausal women who do not have a history of breast cancer. However, until this study, no data were available that addressed the question of whether short-term HRT affects breast cancer risk.

In a prospective cohort of 462 women, of whom 155 underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, Rebbeck and colleagues evaluated the risk of developing breast cancer over an average of 3.6 years based on exposure to any type of HRT. In this multicenter study conducted at 13 different institutions in the United States and Europe, they found that women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation were more likely to be older, have had children, and were more likely to use HRT. Compared with women who did not have bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, women who had undergone the procedure and used any short-term HRT (including estrogen, progesterone, or a combination) still had a substantial decrease in breast cancer risk (HR=0.37; 95% CI, 0.14–0.96).

Practice recommendations

We can now reassure young women who must decide whether to undergo prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to reduce their staggering risks of breast and ovarian cancer: Short-term HRT to address the hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness associated with premature surgical menopause, first, is clinically reasonable and, second, will not substantially reduce the benefits of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for breast cancer risk.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. Available at: http://odphp.osophs.dhhs.gov/pubs/guidecps/. Accessed June 4, 2007.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article

ObGyns perform most of the screening for cancers of the ovary and breast. The first cancer is especially lethal, though rare, and the second is especially feared among women. This update reviews screening guidelines and recent studies that may affect how we detect and prevent ovarian and breast cancers.

Among the findings:

- In the only multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study to date to look at the use of CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasound screening in a low-risk population of postmenopausal women in the United States, researchers found no evidence to suggest a need to revise the present (1996) ovarian cancer screening guidelines of the US Preventive Services Task Force.

- Using a Markov decision-analysis model, investigators explored the health effects of prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in women at average risk of ovarian cancer undergoing hysterectomy. They found that removing the ovaries may decrease overall survival.

- Investigators found the opposite to be true in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy greatly reduced the overall mortality rate, as well as the risk of ovarian and breast cancer.

- In a prospective cohort study of BRCA mutation carriers with no history of breast cancer who underwent prophylactic oophorectomy, researchers found the short-term use of hormone replacement therapy to be safe, with no loss of protection against breast cancer.

No need to revise screening guidelines for ovarian cancer

Buys S, Partridge E, Greene M, et al; for the PLCO Project Team. Ovarian cancer screening in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial: findings from the initial screen of a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1630–1639.

The need to identify a marker for the early detection of ovarian cancer is especially urgent, given that approximately 75% of women with the cancer present with late-stage disease. Because the disease is rare, finding a cost-effective screening test with good sensitivity and very high specificity (to decrease too many false-positive results) will be challenging.

So far, no prospective, randomized studies of any ovarian cancer screening modality have demonstrated a decrease in mortality—the gold standard of efficacy for any screening test. Therefore, the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer trial is a critical study—it is the only multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study in the United States to tackle the question of whether CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasonographic (US) screening will be effective in a low-risk population of postmenopausal women aged 55 to 74.

In this large study, 1 arm underwent ovarian cancer screening with both modalities and the other arm underwent no such screening.

This study reports on baseline, or ‘prevalent,’ cancers

This preliminary report does not comment on the efficacy of ovarian cancer screening; data on the effect of repeated annual screens on detection rates and mortality will become available over the next several years.

Rather, the purpose of this preliminary report was to detail the baseline ovarian cancer screening tests of the 39,115 women randomized to the intervention arm from November 15, 1993, to December 13, 2001. These results describe “prevalent” cancers—that is, cancers that are present on the first screen. The more important information about efficacy of screening will come over the next several years, as “incident” cancers develop.

Roughly 6% of women had at least 1 abnormal finding at baseline

Among 28,506 women with results for both baseline tests, 1,706 had at least 1 abnormal finding:

- 1,338 had an abnormal transvaginal US scan

- 402 had an abnormal level on the CA-125 test

- 34 had abnormalities in both tests

- 29 malignant neoplasms were identified in this population, 20 of them invasive.

When combined, CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasonography had good positive predictive value

In general, a positive predictive value (PPV) of more than 10% (ie, 10 surgeries to detect 1 cancer) is considered reasonable justification for a screening test. In the PLCO trial, the PPV was 4% for CA-125 alone (16 neoplasms in 402 positive screens), 1.6% for transvaginal ultrasonography alone (22 neoplasms in 1,338 positive screens), and 26.5% if both tests were abnormal (9 neoplasms in 34 positive screens).

When tumors of low malignant potential were excluded, the PPV was 3.7% for an abnormal CA-125, 1.0% for an abnormal transvaginal sonogram, and 23.5% if both tests were abnormal. A PPV of 23.5% for both tests is fairly good (ie, approximately 4 surgeries to detect 1 cancer). However, if only women in whom both screening tests were abnormal went to surgery, 12 of 20 invasive cancers would be missed.

Bottom line: Routine screening still not justified

Nothing in the findings reported here suggests that we need to revise the current (from 1996) ovarian cancer screening guidelines of the US Preventive Services Task Force,1 which state that “routine screening for ovarian cancer by US, the measurement of serum tumor markers, or pelvic examination is not recommended.”

We will need to wait until the PLCO trial results come in to see the effect of repeated annual ovarian cancer screens on detection rates and mortality.

Consider ovarian conservation in hysterectomy for benign disease

Parker W, Broder MS, Liu Z, Shoupe D, Farquhar C, Berek JS. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:219–226.

As discussed earlier, we have no good screening tool for the early detection of ovarian cancer. Although rare, ovarian cancer is a lethal, scary disease, and most ObGyns prophylactically remove the ovaries at the time of hysterectomy in most postmenopausal and many perimenopausal women.

The downside to this strategy seems low among postmenopausal women, and the upside, in terms of not having to worry about ovarian cancer, seems high. The study by Parker and colleagues, while having definite limitations, asks us to question this routine practice pattern. The authors found that prophylactic oophorectomy may be associated with decreased overall survival.

Model used SEER data, Nurses’ Health Study to predict survival

Parker and colleagues used a Markov decision-analysis model (a hypothetical mathematical model that uses published data to create cohorts of patients to estimate risk of morbidity or mortality, or both, over time) to evaluate the risks and benefits of ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Age-specific mortality estimates for ovarian cancer were based on Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) statistics.

For women at average risk of ovarian cancer, the probability of surviving to 80 years of age after hysterectomy between 50 and 54 years varied, and was 62.8% and 62.5% for ovarian conservation with and without estrogen therapy, respectively, compared with 62.2% and 53.9% for oophorectomy with and without estrogen therapy. The main reason that the model found decreased overall survival with prophylactic oophorectomy was an increase in coronary artery disease after oophorectomy—a finding that was based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study.

At the very least, think hard about the decision to remove the ovaries

This report estimated that about 300,000 prophylactic oophorectomies are carried out annually in the United States. Although this study has limitations, we believe it encourages debate and reexamination of the benefit of prophylactic oophorectomy for benign indications in young, low-risk patients.

The most important finding from the study is that oophorectomy conferred no survival advantage. Given the rarity of ovarian cancer among the general population, this effect is not that surprising.

For now, careful risk assessment remains a fundamental component of management, so that women who are at increased risk of ovarian cancer can undergo prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy.

For low-risk women, who constitute the majority of patients, the data to support removing ovaries at the time of hysterectomy are less clear.

Make sure the patient understands the low risk of cancer and possible cardiac benefits of preservation

- Conduct a thorough discussion with the patient about the pros and cons of oophorectomy for benign disease.

- The risk of ovarian cancer in the general population is low; patients should understand that they may derive cardiac protection from postmenopausal ovarian function.

Do consider oophorectomy among carriers of a BRCA mutation

Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Neuhausen SL, et al. Mortality after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:223–229.

Women known to have BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations are now managed by means of surveillance or with prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Although bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy has been shown to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer by 90% and the risk of breast cancer by 50%, until this study few data shed light on the effect of the procedure on overall mortality among women with BRCA mutations.

This prospective cohort study identified 155 patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who elected to undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and matched them by age with a control group of 271. All women were followed until death by any cause or by breast, ovarian, or primary peritoneal cancer. The women were followed for a mean of 3.1 years in the bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy group and 2.1 years in the control group.

Overall and cancer-specific survival improved with oophorectomy

Among BRCA mutation carriers, women who chose prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy had improved overall and cancer-specific survival, compared with women who did not undergo the surgery.

In the analysis of the matched BRCA mutation carriers, women who chose to undergo the procedure had a decreased risk of overall mortality (hazard ratio [HR]=0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08–0.71); they also had a decreased risk of mortality due to both breast cancer (HR=0.1; 95% CI, 0.02–0.71) and ovarian cancer (HR=0.05; 95% CI, 0.01–0.46).

Practice recommendations

Apparently, unlike women at average risk of ovarian cancer (for whom prophylactic oophorectomy in conjunction with hysterectomy for benign disease may be associated with decreased overall survival; see the review of the study by Parker and colleagues), women with BRCA mutations may benefit from oophorectomy.

Advantages of prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in this patient population should be discussed with potential surgical candidates, because:

- Women who have a BRCA mutation and who have had bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were shown to have improved overall and cancer-specific survival.

- In this specific group of BRCA mutation carriers, this study did not demonstrate an increased risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, or other causes associated with premature menopause from bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

In BRCA carriers, HRT after oophorectomy does not raise breast cancer risk

Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al; for the PROSE Study Group. Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7804–7810.

In women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, the risk of ovarian cancer is staggering (20% to 40% for BRCA1 mutations, 15% to 25% for BRCA2 mutations), and prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the only strategy proven to significantly reduce risk. A second important benefit for bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy among premenopausal mutation carriers is that the procedure decreases the risk of breast cancer by 50%. In women who have a lifetime risk of breast cancer that is as high as 80%, this benefit is extremely welcome. Current recommendations are for women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations to undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at age 35 to 40, or when child-bearing is complete.

Yet, for many women in this age group, quality of life is substantially altered when premature menopause kicks in after the surgery. Most ObGyns feel comfortable giving short-term hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to premenopausal women who do not have a history of breast cancer. However, until this study, no data were available that addressed the question of whether short-term HRT affects breast cancer risk.

In a prospective cohort of 462 women, of whom 155 underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, Rebbeck and colleagues evaluated the risk of developing breast cancer over an average of 3.6 years based on exposure to any type of HRT. In this multicenter study conducted at 13 different institutions in the United States and Europe, they found that women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation were more likely to be older, have had children, and were more likely to use HRT. Compared with women who did not have bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, women who had undergone the procedure and used any short-term HRT (including estrogen, progesterone, or a combination) still had a substantial decrease in breast cancer risk (HR=0.37; 95% CI, 0.14–0.96).

Practice recommendations

We can now reassure young women who must decide whether to undergo prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to reduce their staggering risks of breast and ovarian cancer: Short-term HRT to address the hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness associated with premature surgical menopause, first, is clinically reasonable and, second, will not substantially reduce the benefits of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for breast cancer risk.

ObGyns perform most of the screening for cancers of the ovary and breast. The first cancer is especially lethal, though rare, and the second is especially feared among women. This update reviews screening guidelines and recent studies that may affect how we detect and prevent ovarian and breast cancers.

Among the findings:

- In the only multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study to date to look at the use of CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasound screening in a low-risk population of postmenopausal women in the United States, researchers found no evidence to suggest a need to revise the present (1996) ovarian cancer screening guidelines of the US Preventive Services Task Force.

- Using a Markov decision-analysis model, investigators explored the health effects of prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in women at average risk of ovarian cancer undergoing hysterectomy. They found that removing the ovaries may decrease overall survival.

- Investigators found the opposite to be true in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy greatly reduced the overall mortality rate, as well as the risk of ovarian and breast cancer.

- In a prospective cohort study of BRCA mutation carriers with no history of breast cancer who underwent prophylactic oophorectomy, researchers found the short-term use of hormone replacement therapy to be safe, with no loss of protection against breast cancer.

No need to revise screening guidelines for ovarian cancer

Buys S, Partridge E, Greene M, et al; for the PLCO Project Team. Ovarian cancer screening in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial: findings from the initial screen of a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1630–1639.

The need to identify a marker for the early detection of ovarian cancer is especially urgent, given that approximately 75% of women with the cancer present with late-stage disease. Because the disease is rare, finding a cost-effective screening test with good sensitivity and very high specificity (to decrease too many false-positive results) will be challenging.

So far, no prospective, randomized studies of any ovarian cancer screening modality have demonstrated a decrease in mortality—the gold standard of efficacy for any screening test. Therefore, the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer trial is a critical study—it is the only multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study in the United States to tackle the question of whether CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasonographic (US) screening will be effective in a low-risk population of postmenopausal women aged 55 to 74.

In this large study, 1 arm underwent ovarian cancer screening with both modalities and the other arm underwent no such screening.

This study reports on baseline, or ‘prevalent,’ cancers

This preliminary report does not comment on the efficacy of ovarian cancer screening; data on the effect of repeated annual screens on detection rates and mortality will become available over the next several years.

Rather, the purpose of this preliminary report was to detail the baseline ovarian cancer screening tests of the 39,115 women randomized to the intervention arm from November 15, 1993, to December 13, 2001. These results describe “prevalent” cancers—that is, cancers that are present on the first screen. The more important information about efficacy of screening will come over the next several years, as “incident” cancers develop.

Roughly 6% of women had at least 1 abnormal finding at baseline

Among 28,506 women with results for both baseline tests, 1,706 had at least 1 abnormal finding:

- 1,338 had an abnormal transvaginal US scan

- 402 had an abnormal level on the CA-125 test

- 34 had abnormalities in both tests

- 29 malignant neoplasms were identified in this population, 20 of them invasive.

When combined, CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasonography had good positive predictive value

In general, a positive predictive value (PPV) of more than 10% (ie, 10 surgeries to detect 1 cancer) is considered reasonable justification for a screening test. In the PLCO trial, the PPV was 4% for CA-125 alone (16 neoplasms in 402 positive screens), 1.6% for transvaginal ultrasonography alone (22 neoplasms in 1,338 positive screens), and 26.5% if both tests were abnormal (9 neoplasms in 34 positive screens).

When tumors of low malignant potential were excluded, the PPV was 3.7% for an abnormal CA-125, 1.0% for an abnormal transvaginal sonogram, and 23.5% if both tests were abnormal. A PPV of 23.5% for both tests is fairly good (ie, approximately 4 surgeries to detect 1 cancer). However, if only women in whom both screening tests were abnormal went to surgery, 12 of 20 invasive cancers would be missed.

Bottom line: Routine screening still not justified

Nothing in the findings reported here suggests that we need to revise the current (from 1996) ovarian cancer screening guidelines of the US Preventive Services Task Force,1 which state that “routine screening for ovarian cancer by US, the measurement of serum tumor markers, or pelvic examination is not recommended.”

We will need to wait until the PLCO trial results come in to see the effect of repeated annual ovarian cancer screens on detection rates and mortality.

Consider ovarian conservation in hysterectomy for benign disease

Parker W, Broder MS, Liu Z, Shoupe D, Farquhar C, Berek JS. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:219–226.

As discussed earlier, we have no good screening tool for the early detection of ovarian cancer. Although rare, ovarian cancer is a lethal, scary disease, and most ObGyns prophylactically remove the ovaries at the time of hysterectomy in most postmenopausal and many perimenopausal women.

The downside to this strategy seems low among postmenopausal women, and the upside, in terms of not having to worry about ovarian cancer, seems high. The study by Parker and colleagues, while having definite limitations, asks us to question this routine practice pattern. The authors found that prophylactic oophorectomy may be associated with decreased overall survival.

Model used SEER data, Nurses’ Health Study to predict survival

Parker and colleagues used a Markov decision-analysis model (a hypothetical mathematical model that uses published data to create cohorts of patients to estimate risk of morbidity or mortality, or both, over time) to evaluate the risks and benefits of ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Age-specific mortality estimates for ovarian cancer were based on Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) statistics.

For women at average risk of ovarian cancer, the probability of surviving to 80 years of age after hysterectomy between 50 and 54 years varied, and was 62.8% and 62.5% for ovarian conservation with and without estrogen therapy, respectively, compared with 62.2% and 53.9% for oophorectomy with and without estrogen therapy. The main reason that the model found decreased overall survival with prophylactic oophorectomy was an increase in coronary artery disease after oophorectomy—a finding that was based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study.

At the very least, think hard about the decision to remove the ovaries

This report estimated that about 300,000 prophylactic oophorectomies are carried out annually in the United States. Although this study has limitations, we believe it encourages debate and reexamination of the benefit of prophylactic oophorectomy for benign indications in young, low-risk patients.

The most important finding from the study is that oophorectomy conferred no survival advantage. Given the rarity of ovarian cancer among the general population, this effect is not that surprising.

For now, careful risk assessment remains a fundamental component of management, so that women who are at increased risk of ovarian cancer can undergo prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy.

For low-risk women, who constitute the majority of patients, the data to support removing ovaries at the time of hysterectomy are less clear.

Make sure the patient understands the low risk of cancer and possible cardiac benefits of preservation

- Conduct a thorough discussion with the patient about the pros and cons of oophorectomy for benign disease.

- The risk of ovarian cancer in the general population is low; patients should understand that they may derive cardiac protection from postmenopausal ovarian function.

Do consider oophorectomy among carriers of a BRCA mutation

Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Neuhausen SL, et al. Mortality after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:223–229.

Women known to have BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations are now managed by means of surveillance or with prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Although bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy has been shown to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer by 90% and the risk of breast cancer by 50%, until this study few data shed light on the effect of the procedure on overall mortality among women with BRCA mutations.

This prospective cohort study identified 155 patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who elected to undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and matched them by age with a control group of 271. All women were followed until death by any cause or by breast, ovarian, or primary peritoneal cancer. The women were followed for a mean of 3.1 years in the bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy group and 2.1 years in the control group.

Overall and cancer-specific survival improved with oophorectomy

Among BRCA mutation carriers, women who chose prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy had improved overall and cancer-specific survival, compared with women who did not undergo the surgery.

In the analysis of the matched BRCA mutation carriers, women who chose to undergo the procedure had a decreased risk of overall mortality (hazard ratio [HR]=0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08–0.71); they also had a decreased risk of mortality due to both breast cancer (HR=0.1; 95% CI, 0.02–0.71) and ovarian cancer (HR=0.05; 95% CI, 0.01–0.46).

Practice recommendations

Apparently, unlike women at average risk of ovarian cancer (for whom prophylactic oophorectomy in conjunction with hysterectomy for benign disease may be associated with decreased overall survival; see the review of the study by Parker and colleagues), women with BRCA mutations may benefit from oophorectomy.

Advantages of prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in this patient population should be discussed with potential surgical candidates, because:

- Women who have a BRCA mutation and who have had bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were shown to have improved overall and cancer-specific survival.

- In this specific group of BRCA mutation carriers, this study did not demonstrate an increased risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, or other causes associated with premature menopause from bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

In BRCA carriers, HRT after oophorectomy does not raise breast cancer risk

Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al; for the PROSE Study Group. Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7804–7810.

In women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, the risk of ovarian cancer is staggering (20% to 40% for BRCA1 mutations, 15% to 25% for BRCA2 mutations), and prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the only strategy proven to significantly reduce risk. A second important benefit for bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy among premenopausal mutation carriers is that the procedure decreases the risk of breast cancer by 50%. In women who have a lifetime risk of breast cancer that is as high as 80%, this benefit is extremely welcome. Current recommendations are for women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations to undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at age 35 to 40, or when child-bearing is complete.

Yet, for many women in this age group, quality of life is substantially altered when premature menopause kicks in after the surgery. Most ObGyns feel comfortable giving short-term hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to premenopausal women who do not have a history of breast cancer. However, until this study, no data were available that addressed the question of whether short-term HRT affects breast cancer risk.

In a prospective cohort of 462 women, of whom 155 underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, Rebbeck and colleagues evaluated the risk of developing breast cancer over an average of 3.6 years based on exposure to any type of HRT. In this multicenter study conducted at 13 different institutions in the United States and Europe, they found that women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation were more likely to be older, have had children, and were more likely to use HRT. Compared with women who did not have bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, women who had undergone the procedure and used any short-term HRT (including estrogen, progesterone, or a combination) still had a substantial decrease in breast cancer risk (HR=0.37; 95% CI, 0.14–0.96).

Practice recommendations

We can now reassure young women who must decide whether to undergo prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to reduce their staggering risks of breast and ovarian cancer: Short-term HRT to address the hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness associated with premature surgical menopause, first, is clinically reasonable and, second, will not substantially reduce the benefits of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for breast cancer risk.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. Available at: http://odphp.osophs.dhhs.gov/pubs/guidecps/. Accessed June 4, 2007.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. Available at: http://odphp.osophs.dhhs.gov/pubs/guidecps/. Accessed June 4, 2007.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article

ENDOMETRIAL CANCER

ObGyns are the first to make the diagnosis and are frequently involved in the treatment of endometrial cancer. It is the most common gynecologic cancer—more common than ovarian cancer and cervical cancer combined.

There will be an estimated 41,200 cases and 7,350 deaths from uterine cancer in 2006.

This update reviews recent studies and practice guidelines that may affect how we manage this disease.

Anticipate cancer when the diagnosis is atypical hyperplasia

Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ II, Alberts D, Curtin J. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer. 2006;106:812–819.

When we see a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, we need to consider that there very well may be an endometrial cancer already present

ObGyns often manage women with a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and we know that it is a precursor to endometrial cancer. A now-classic study1 found that 29% of women with complex atypical hyperplasia go on to develop endometrial cancer, and the standard recommendation for women with complex atypical hyperplasia is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. (The exception to surgical management is for young women who wish to retain their ability to have children; in these cases, conservative management with progesterone therapy is often attempted.)

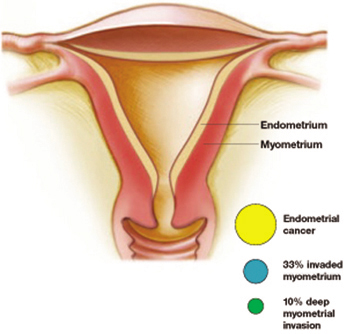

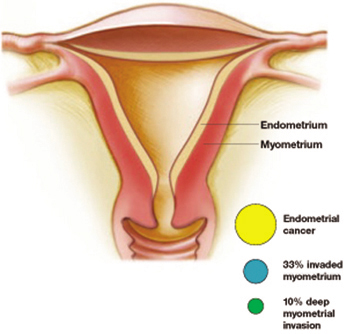

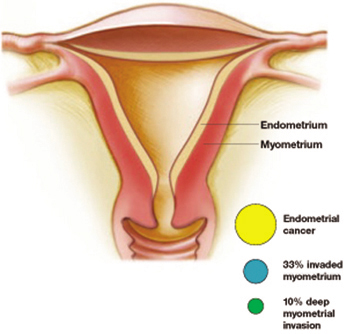

A considerably higher rate—42.6%—of concurrent endometrial carcinoma was found, in a large NIH-sponsored study conducted by Trimble and colleagues, from the Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions. A panel of gynecologic pathologists analyzed the diagnostic biopsy specimens and the hysterectomy slides of 289 women who had a preoperative diagnosis of complex atypical hyperplasia. Of those who had concurrent cancer, about one third of the cancers invaded the myometrium, and about 10% involved deep myometrial invasion.

Atypical hyperplasia: A warning sign

More than 40% of women with a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia had endometrial cancer. About a third of these cancers had invaded the myometrium—a tenth of them deeply. Trimble et al

Practice recommendations

I believe the findings of this study have two important implications for practice:

- When taking a patient with complex atypical hyperplasia to the operating room, an intraoperative frozen section is important. Understaging can occur if the surgeon is not prepared to perform staging.

- In counseling patients with complex atypical hyperplasia, it is important to inform them of the high risk of finding a concurrent cancer. Women who choose conservative medical management with progesterone due to their wish to retain childbearing potential should be informed of the risks. In addition, very close follow-up with serial endometrial biopsies or dilation and curettage should be considered.

No pre-op evidence of metastatic cancer? Don’t get too comfortable

Orr Jr J, Chamberlain D, Kilgore L, Naumann W. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 65. Management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:413–425.

ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of endometrial cancer cases

The most significant and controversial aspect of the new ACOG Practice Bulletin is the strong recommendation that most women with endometrial cancer undergo full staging, including pelvic washings, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and complete resection of all disease. The exceptions include young or perimenopausal women with grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma associated with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and women at increased risk of mortality secondary to comorbidities. The bulletin acknowledges that the recommendations are based on limited or inconsistent evidence (Level B).

One of the reasons for full surgical staging for most endometrial cancers is the difficulty in accurately determining grade and depth of invasion intraoperatively. Because of this difficulty, gynecologic oncologists occasionally see patients who were understaged. This limits the oncologist’s ability to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and accurately assess risk of recurrence.

Practice recommendations

Many ObGyns feel comfortable taking a patient with complex hyperplasia or grade I endometrial cancer to the operating room if there is no evidence of metastatic disease or deep myometrial invasion. These new guidelines mean that ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of cases of endometrial cancer.

The bulletin also offers helpful guidelines for preoperative evaluation and postoperative adjuvant treatment, and discusses specific recommendations for women found to have endometrial cancer after a hysterectomy, progesterone therapy for early grade I disease, and management of endometrial cancer in patients with morbid obesity.

Estrogen therapy after hysterectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer

Barakat RR, Bundy BN, Spirtos NM, Bell J, Mannel RS. Randomized double-blind trial of estrogen replacement therapy versus placebo in stage I or II endometrial cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:587–592.

For women with problematic symptoms that are unresponsive to other drugs, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting is unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer

This prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study was initiated to examine whether estrogen replacement therapy had a deleterious effect on the risk of recurrence in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer. More than 1,236 women were randomized to either estrogen replacement therapy or placebo. Although the study did not complete accrual, and therefore definitive answers about the effect of estrogen replacement on survival cannot be made, some useful clinical information resulted.

The absolute recurrence rate in those taking estrogen therapy was 2.1%, which is quite low. This low rate did not differ significantly from the recurrence rate in the placebo group. It is unlikely that a randomized clinical trial will ever definitively answer the question of safety of estrogen replacement therapy in women with early-stage endometrial cancer. Therefore, the decision to use estrogen replacement therapy has to be individualized.

Estrogen replacement therapy will most likely be for the approximately one quarter of all women with endometrial cancer who are under the age of 50 and for whom surgical treatment of endometrial cancer will result in premature menopause.

Symptoms including hot flashes and night sweats can be addressed initially with agents such as venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

For women whose problematic symptoms do not improve with these drugs, however, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting was unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer, this study found.

Practice recommendations

The ACOG Committee Opinion for Hormone Replacement Therapy in Women Treated for Endometrial Cancer, Number 234, May 2000 (published before completion of this study) recommends individualization on the basis of potential benefit and risk to the patient.

It is a good recommendation, and now this study’s results can be included, as well, in discussions with patients about risks and benefits.

Surgery prevents Lynch syndrome cancers

Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen L-M, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, Clark MB, Daniels MS, White KG, Boyd-Rogers SG, Conrad PG, Yang KY, Rubin MM, Sun CC, Slomovitz BM, Gershenson DM, Lu KH. Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:261–269.

Lu K, Broaddus R. Gynecologic cancers in HNPCC. Familial Cancer. 2005;4:249–254.

Prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is an effective strategy for prevention of endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome

Although ObGyns are familiar with the Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer syndrome and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, few are familiar with the increased risk of endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome, also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC).

The Lynch syndrome is an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome that increases risk for endometrial cancer, colon cancer, and ovarian cancer. There are also less common cancers associated with Lynch syndrome. The genes that are responsible for inherited cancer susceptibility in families with Lynch syndrome are MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6. These genes are part of a family of genes that are responsible for repairing DNA mistakes during DNA replication. Mutations in one of the genes occur in about 1 in 1,000 individuals, which is similar in frequency to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Women with Lynch syndrome have a 40% to 60% lifetime risk of colon cancer and a 40% to 60% risk of endometrial cancer (compare this to the 5% lifetime risk of colon cancer and 3% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer in the general population).

ObGyns can:

- Identify women who may have Lynch syndrome

- Manage their endometrial and ovarian cancer risks

The New England Journal of Medicine report helps to further define prevention strategies. Of 315 women with documented germline mutations associated with the Lynch syndrome, 61 underwent prophylactic hysterectomy and were matched with 210 women who did not undergo hysterectomy.

Key results

- None of the women who underwent prophylactic hysterectomy developed endometrial cancer, whereas 69 women in the control group (33%) developed endometrial cancer.

- None of the women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy developed ovarian cancer, whereas 12 women in the control group (5%) developed ovarian cancer.

Practice recommendations

- These findings suggest that prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy is an effective strategy for preventing endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome.

- For endometrial and ovarian cancer screening, the available studies have shown that measurement of the endometrial stripe is unlikely to be effective.

- Current consensus group recommendations advise an annual endometrial biopsy and a transvaginal ultrasound to examine the ovaries.

- For colon cancer screening, a colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years is recommended.

1. Kurman R, Kaminski P, Norris H. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403-411.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

ObGyns are the first to make the diagnosis and are frequently involved in the treatment of endometrial cancer. It is the most common gynecologic cancer—more common than ovarian cancer and cervical cancer combined.

There will be an estimated 41,200 cases and 7,350 deaths from uterine cancer in 2006.

This update reviews recent studies and practice guidelines that may affect how we manage this disease.

Anticipate cancer when the diagnosis is atypical hyperplasia

Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ II, Alberts D, Curtin J. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer. 2006;106:812–819.

When we see a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, we need to consider that there very well may be an endometrial cancer already present

ObGyns often manage women with a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and we know that it is a precursor to endometrial cancer. A now-classic study1 found that 29% of women with complex atypical hyperplasia go on to develop endometrial cancer, and the standard recommendation for women with complex atypical hyperplasia is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. (The exception to surgical management is for young women who wish to retain their ability to have children; in these cases, conservative management with progesterone therapy is often attempted.)

A considerably higher rate—42.6%—of concurrent endometrial carcinoma was found, in a large NIH-sponsored study conducted by Trimble and colleagues, from the Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions. A panel of gynecologic pathologists analyzed the diagnostic biopsy specimens and the hysterectomy slides of 289 women who had a preoperative diagnosis of complex atypical hyperplasia. Of those who had concurrent cancer, about one third of the cancers invaded the myometrium, and about 10% involved deep myometrial invasion.

Atypical hyperplasia: A warning sign

More than 40% of women with a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia had endometrial cancer. About a third of these cancers had invaded the myometrium—a tenth of them deeply. Trimble et al

Practice recommendations

I believe the findings of this study have two important implications for practice:

- When taking a patient with complex atypical hyperplasia to the operating room, an intraoperative frozen section is important. Understaging can occur if the surgeon is not prepared to perform staging.

- In counseling patients with complex atypical hyperplasia, it is important to inform them of the high risk of finding a concurrent cancer. Women who choose conservative medical management with progesterone due to their wish to retain childbearing potential should be informed of the risks. In addition, very close follow-up with serial endometrial biopsies or dilation and curettage should be considered.

No pre-op evidence of metastatic cancer? Don’t get too comfortable

Orr Jr J, Chamberlain D, Kilgore L, Naumann W. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 65. Management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:413–425.

ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of endometrial cancer cases

The most significant and controversial aspect of the new ACOG Practice Bulletin is the strong recommendation that most women with endometrial cancer undergo full staging, including pelvic washings, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and complete resection of all disease. The exceptions include young or perimenopausal women with grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma associated with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and women at increased risk of mortality secondary to comorbidities. The bulletin acknowledges that the recommendations are based on limited or inconsistent evidence (Level B).

One of the reasons for full surgical staging for most endometrial cancers is the difficulty in accurately determining grade and depth of invasion intraoperatively. Because of this difficulty, gynecologic oncologists occasionally see patients who were understaged. This limits the oncologist’s ability to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and accurately assess risk of recurrence.

Practice recommendations

Many ObGyns feel comfortable taking a patient with complex hyperplasia or grade I endometrial cancer to the operating room if there is no evidence of metastatic disease or deep myometrial invasion. These new guidelines mean that ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of cases of endometrial cancer.

The bulletin also offers helpful guidelines for preoperative evaluation and postoperative adjuvant treatment, and discusses specific recommendations for women found to have endometrial cancer after a hysterectomy, progesterone therapy for early grade I disease, and management of endometrial cancer in patients with morbid obesity.

Estrogen therapy after hysterectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer

Barakat RR, Bundy BN, Spirtos NM, Bell J, Mannel RS. Randomized double-blind trial of estrogen replacement therapy versus placebo in stage I or II endometrial cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:587–592.

For women with problematic symptoms that are unresponsive to other drugs, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting is unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer

This prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study was initiated to examine whether estrogen replacement therapy had a deleterious effect on the risk of recurrence in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer. More than 1,236 women were randomized to either estrogen replacement therapy or placebo. Although the study did not complete accrual, and therefore definitive answers about the effect of estrogen replacement on survival cannot be made, some useful clinical information resulted.

The absolute recurrence rate in those taking estrogen therapy was 2.1%, which is quite low. This low rate did not differ significantly from the recurrence rate in the placebo group. It is unlikely that a randomized clinical trial will ever definitively answer the question of safety of estrogen replacement therapy in women with early-stage endometrial cancer. Therefore, the decision to use estrogen replacement therapy has to be individualized.

Estrogen replacement therapy will most likely be for the approximately one quarter of all women with endometrial cancer who are under the age of 50 and for whom surgical treatment of endometrial cancer will result in premature menopause.

Symptoms including hot flashes and night sweats can be addressed initially with agents such as venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

For women whose problematic symptoms do not improve with these drugs, however, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting was unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer, this study found.

Practice recommendations

The ACOG Committee Opinion for Hormone Replacement Therapy in Women Treated for Endometrial Cancer, Number 234, May 2000 (published before completion of this study) recommends individualization on the basis of potential benefit and risk to the patient.

It is a good recommendation, and now this study’s results can be included, as well, in discussions with patients about risks and benefits.

Surgery prevents Lynch syndrome cancers

Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen L-M, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, Clark MB, Daniels MS, White KG, Boyd-Rogers SG, Conrad PG, Yang KY, Rubin MM, Sun CC, Slomovitz BM, Gershenson DM, Lu KH. Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:261–269.

Lu K, Broaddus R. Gynecologic cancers in HNPCC. Familial Cancer. 2005;4:249–254.

Prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is an effective strategy for prevention of endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome

Although ObGyns are familiar with the Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer syndrome and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, few are familiar with the increased risk of endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome, also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC).

The Lynch syndrome is an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome that increases risk for endometrial cancer, colon cancer, and ovarian cancer. There are also less common cancers associated with Lynch syndrome. The genes that are responsible for inherited cancer susceptibility in families with Lynch syndrome are MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6. These genes are part of a family of genes that are responsible for repairing DNA mistakes during DNA replication. Mutations in one of the genes occur in about 1 in 1,000 individuals, which is similar in frequency to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Women with Lynch syndrome have a 40% to 60% lifetime risk of colon cancer and a 40% to 60% risk of endometrial cancer (compare this to the 5% lifetime risk of colon cancer and 3% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer in the general population).

ObGyns can:

- Identify women who may have Lynch syndrome

- Manage their endometrial and ovarian cancer risks

The New England Journal of Medicine report helps to further define prevention strategies. Of 315 women with documented germline mutations associated with the Lynch syndrome, 61 underwent prophylactic hysterectomy and were matched with 210 women who did not undergo hysterectomy.

Key results

- None of the women who underwent prophylactic hysterectomy developed endometrial cancer, whereas 69 women in the control group (33%) developed endometrial cancer.

- None of the women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy developed ovarian cancer, whereas 12 women in the control group (5%) developed ovarian cancer.

Practice recommendations

- These findings suggest that prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy is an effective strategy for preventing endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome.

- For endometrial and ovarian cancer screening, the available studies have shown that measurement of the endometrial stripe is unlikely to be effective.

- Current consensus group recommendations advise an annual endometrial biopsy and a transvaginal ultrasound to examine the ovaries.

- For colon cancer screening, a colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years is recommended.

ObGyns are the first to make the diagnosis and are frequently involved in the treatment of endometrial cancer. It is the most common gynecologic cancer—more common than ovarian cancer and cervical cancer combined.

There will be an estimated 41,200 cases and 7,350 deaths from uterine cancer in 2006.

This update reviews recent studies and practice guidelines that may affect how we manage this disease.

Anticipate cancer when the diagnosis is atypical hyperplasia

Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ II, Alberts D, Curtin J. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer. 2006;106:812–819.

When we see a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, we need to consider that there very well may be an endometrial cancer already present

ObGyns often manage women with a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and we know that it is a precursor to endometrial cancer. A now-classic study1 found that 29% of women with complex atypical hyperplasia go on to develop endometrial cancer, and the standard recommendation for women with complex atypical hyperplasia is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. (The exception to surgical management is for young women who wish to retain their ability to have children; in these cases, conservative management with progesterone therapy is often attempted.)

A considerably higher rate—42.6%—of concurrent endometrial carcinoma was found, in a large NIH-sponsored study conducted by Trimble and colleagues, from the Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions. A panel of gynecologic pathologists analyzed the diagnostic biopsy specimens and the hysterectomy slides of 289 women who had a preoperative diagnosis of complex atypical hyperplasia. Of those who had concurrent cancer, about one third of the cancers invaded the myometrium, and about 10% involved deep myometrial invasion.

Atypical hyperplasia: A warning sign

More than 40% of women with a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia had endometrial cancer. About a third of these cancers had invaded the myometrium—a tenth of them deeply. Trimble et al

Practice recommendations

I believe the findings of this study have two important implications for practice:

- When taking a patient with complex atypical hyperplasia to the operating room, an intraoperative frozen section is important. Understaging can occur if the surgeon is not prepared to perform staging.

- In counseling patients with complex atypical hyperplasia, it is important to inform them of the high risk of finding a concurrent cancer. Women who choose conservative medical management with progesterone due to their wish to retain childbearing potential should be informed of the risks. In addition, very close follow-up with serial endometrial biopsies or dilation and curettage should be considered.

No pre-op evidence of metastatic cancer? Don’t get too comfortable

Orr Jr J, Chamberlain D, Kilgore L, Naumann W. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 65. Management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:413–425.

ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of endometrial cancer cases

The most significant and controversial aspect of the new ACOG Practice Bulletin is the strong recommendation that most women with endometrial cancer undergo full staging, including pelvic washings, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and complete resection of all disease. The exceptions include young or perimenopausal women with grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma associated with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and women at increased risk of mortality secondary to comorbidities. The bulletin acknowledges that the recommendations are based on limited or inconsistent evidence (Level B).

One of the reasons for full surgical staging for most endometrial cancers is the difficulty in accurately determining grade and depth of invasion intraoperatively. Because of this difficulty, gynecologic oncologists occasionally see patients who were understaged. This limits the oncologist’s ability to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and accurately assess risk of recurrence.

Practice recommendations

Many ObGyns feel comfortable taking a patient with complex hyperplasia or grade I endometrial cancer to the operating room if there is no evidence of metastatic disease or deep myometrial invasion. These new guidelines mean that ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of cases of endometrial cancer.

The bulletin also offers helpful guidelines for preoperative evaluation and postoperative adjuvant treatment, and discusses specific recommendations for women found to have endometrial cancer after a hysterectomy, progesterone therapy for early grade I disease, and management of endometrial cancer in patients with morbid obesity.

Estrogen therapy after hysterectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer

Barakat RR, Bundy BN, Spirtos NM, Bell J, Mannel RS. Randomized double-blind trial of estrogen replacement therapy versus placebo in stage I or II endometrial cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:587–592.

For women with problematic symptoms that are unresponsive to other drugs, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting is unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer

This prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study was initiated to examine whether estrogen replacement therapy had a deleterious effect on the risk of recurrence in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer. More than 1,236 women were randomized to either estrogen replacement therapy or placebo. Although the study did not complete accrual, and therefore definitive answers about the effect of estrogen replacement on survival cannot be made, some useful clinical information resulted.

The absolute recurrence rate in those taking estrogen therapy was 2.1%, which is quite low. This low rate did not differ significantly from the recurrence rate in the placebo group. It is unlikely that a randomized clinical trial will ever definitively answer the question of safety of estrogen replacement therapy in women with early-stage endometrial cancer. Therefore, the decision to use estrogen replacement therapy has to be individualized.

Estrogen replacement therapy will most likely be for the approximately one quarter of all women with endometrial cancer who are under the age of 50 and for whom surgical treatment of endometrial cancer will result in premature menopause.

Symptoms including hot flashes and night sweats can be addressed initially with agents such as venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

For women whose problematic symptoms do not improve with these drugs, however, short-term estrogen may be an option. Estrogen in this setting was unlikely to significantly increase the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer, this study found.

Practice recommendations

The ACOG Committee Opinion for Hormone Replacement Therapy in Women Treated for Endometrial Cancer, Number 234, May 2000 (published before completion of this study) recommends individualization on the basis of potential benefit and risk to the patient.

It is a good recommendation, and now this study’s results can be included, as well, in discussions with patients about risks and benefits.

Surgery prevents Lynch syndrome cancers

Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen L-M, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, Clark MB, Daniels MS, White KG, Boyd-Rogers SG, Conrad PG, Yang KY, Rubin MM, Sun CC, Slomovitz BM, Gershenson DM, Lu KH. Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:261–269.

Lu K, Broaddus R. Gynecologic cancers in HNPCC. Familial Cancer. 2005;4:249–254.

Prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is an effective strategy for prevention of endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome

Although ObGyns are familiar with the Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer syndrome and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, few are familiar with the increased risk of endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome, also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC).

The Lynch syndrome is an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome that increases risk for endometrial cancer, colon cancer, and ovarian cancer. There are also less common cancers associated with Lynch syndrome. The genes that are responsible for inherited cancer susceptibility in families with Lynch syndrome are MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6. These genes are part of a family of genes that are responsible for repairing DNA mistakes during DNA replication. Mutations in one of the genes occur in about 1 in 1,000 individuals, which is similar in frequency to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Women with Lynch syndrome have a 40% to 60% lifetime risk of colon cancer and a 40% to 60% risk of endometrial cancer (compare this to the 5% lifetime risk of colon cancer and 3% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer in the general population).

ObGyns can:

- Identify women who may have Lynch syndrome

- Manage their endometrial and ovarian cancer risks

The New England Journal of Medicine report helps to further define prevention strategies. Of 315 women with documented germline mutations associated with the Lynch syndrome, 61 underwent prophylactic hysterectomy and were matched with 210 women who did not undergo hysterectomy.

Key results

- None of the women who underwent prophylactic hysterectomy developed endometrial cancer, whereas 69 women in the control group (33%) developed endometrial cancer.

- None of the women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy developed ovarian cancer, whereas 12 women in the control group (5%) developed ovarian cancer.

Practice recommendations

- These findings suggest that prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy is an effective strategy for preventing endometrial and ovarian cancer in women with the Lynch syndrome.

- For endometrial and ovarian cancer screening, the available studies have shown that measurement of the endometrial stripe is unlikely to be effective.

- Current consensus group recommendations advise an annual endometrial biopsy and a transvaginal ultrasound to examine the ovaries.

- For colon cancer screening, a colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years is recommended.

1. Kurman R, Kaminski P, Norris H. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403-411.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Kurman R, Kaminski P, Norris H. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403-411.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Gynecologic Cancer

This Update reviews recent findings of importance to obstetricians and gynecologists. Late detection of ovarian cancer is still the main reason for the high mortality rate of the most deadly of the gynecologic cancers. Approximately 22,200 women will be newly diagnosed in the United States this year, and there will be 16,210 deaths. Since ovarian cancer is still initially detected in its advanced stages in more than 70% of cases, when cure rates are low, early detection and prevention remain our greatest challenge. The gynecologic oncologist’s opportunity to successfully treat malignancy depends on early detection, and therefore physicians providing primary care for women are our firstline guardians.

“Silent killer” may not be so stealthy

Women ultimately diagnosed with malignant masses had a triad of symptoms, as well as more recent onset and greater severity of symptoms than women with benign masses or no masses. A diagnostic workup employing transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 should be considered when a woman says she has these symptoms.

Ovarian cancer is not a silent disease. It was believed to be a “silent killer” because it was thought to be asymptomatic until a woman had very advanced disease. However, Goff and colleagues, in a previous study, found that 95% of women with ovarian cancer had had symptoms prior to diagnosis—and that the type of symptoms was not significantly different, whether disease was early stage or late stage.

This new study aimed to identify the frequency, severity, and duration of symptoms typically associated with ovarian cancer, by comparing symptoms reported by different groups of women. Symptoms reported by women presenting to primary care clinics were compared with symptoms reported by a group of 128 women with ovarian masses. Importantly, women were surveyed about their symptoms before undergoing surgery, and before they had a diagnosis of cancer or benign disease.

Main findings:

- A triad of symptoms—abdominal bloating, an increase in abdominal girth, and urinary symptoms—occurred in 43% of women found to have ovarian cancer, but in only 8% of women who presented to a primary care clinic.

- The frequency and duration of symptoms in women with ovarian masses were more severe in the women with malignant masses, but were of a similar type regardless of whether the mass was benign or ovarian cancer.

- Onset of symptoms was more recent in women with ovarian cancer than in the control group.

Listening carefully and evaluating the severity, frequency, and duration of symptoms, especially abdominal bloating, an increase in abdominal girth, urinary symptoms, and abdominal pain, is all-important.

Ovarian cancer should be included in the differential diagnosis when a woman says she has these symptoms.

I found it interesting that symptoms with a more recent onset may be more consistent with ovarian cancer.

In an ideal world, a simple blood test with an absolute cutoff, with perfect sensitivity and specificity, would identify ovarian cancer at its earliest stages. However, until such a test exists, primary care physicians and ObGyns should continue to put weight on the symptoms the patient communicates.

Transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125

Consider performing a diagnostic workup employing transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 measurement in women presenting with these complaints.