User login

Rendered speechless

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 63-year-old man at an inpatient rehabilitation center was transferred to an academic tertiary care center for evaluation of slurred speech and episodic confusion. He was accompanied by his wife, who provided the history. Three weeks earlier, the patient had fallen, sustaining a right femur fracture. He underwent surgery and was discharged to rehabilitation on postoperative day 3. During the second week of rehabilitation, he developed a cough and low-grade fevers, which prompted treatment with cefpodoxime for 5 days for presumed pneumonia. The day after completing antimicrobial therapy, he became confused and began to slur his words.

Confusion is a nonspecific symptom that typically has a diffuse or multifocal localization within the cerebral hemispheres and is unlikely to be caused by a single lesion. Slurred speech may accompany global metabolic dysfunction. However, slurred speech typically localizes to the brainstem, the cerebellum in the posterior fossa, the nuclei, or the course of cranial nerves VII, X, or XII, including where these nerves pass through the subarachnoid space.

It seems this patient’s new neurologic symptoms have some relationship to his fall. Long-bone fractures and altered mental status (AMS) lead to consideration of fat emboli, but this syndrome typically presents in the acute period after the fracture. The patient is at risk for a number of complications, related to recent surgery and hospitalization, that could affect the central nervous system (CNS), including systemic infection (possibly with associated meningeal involvement) and venous thromboembolism with concomitant stroke by paradoxical emboli. The episodic nature of the confusion leads to consideration of seizures from structural lesions in the brain. Finally, the circumstances of the fall itself should be explored to determine whether an underlying neurologic dysfunction led to imbalance and gait difficulty.

Over the next 3 days at the inpatient rehabilitation center, the patient’s slurred speech became unintelligible, and he experienced intermittent disorientation to person, place, and time. There was no concomitant fever, dizziness, headache, neck pain, weakness, dyspnea, diarrhea, dysuria, or change in hearing or vision.

Progressive dysarthria argues for an expanding lesion in the posterior fossa, worsening metabolic disturbance, or a problem affecting the cranial nerves (eg, Guillain-Barré syndrome) or neuromuscular junctions (eg, myasthenia gravis). Lack of headache makes a CNS localization less likely, though disorientation must localize to the brain itself. The transient nature of the AMS could signal an ictal phenomenon or a fluctuating toxic or metabolic condition, such as hyperammonemia, drug reaction, or healthcare–acquired delirium.

His past medical history included end-stage liver disease secondary to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis status post transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure three years prior, hepatic encephalopathy, diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, previous melanoma excision on his back, and recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis. Two years prior to admission he had been started on an indefinite course of metronidazole 500 mg twice daily without any recurrence. The patient’s other medications were aspirin, furosemide, insulin, lactulose, mirtazapine, pantoprazole, propranolol, spironolactone, and zinc. At the rehabilitation center, he was prescribed oral oxycodone 5 mg as needed every 4 hours for pain. He denied use of tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drugs. He previously worked as a funeral home director and embalmer.

Hyperammonemia and hepatic encephalopathy can present with a fluctuating mental state that often correlates to dietary protein intake or the frequency of bowel movements; the previous TIPS history places the patient at further risk. Use of oxycodone or another narcotic commonly leads to confusion, , especially in patients who are older, have preexisting cognitive decline, or have concomitant medical comorbidities. Mirtazapine and propranolol have been associated more rarely with encephalopathy, and therefore a careful history of adherence, drug interactions, and appropriate dosing should be obtained. Metronidazole is most often associated neurologically with a peripheral neuropathy; however, it is increasingly recognized that some patients can develop a CNS syndrome that features an AMS, which can be severe and accompanied by ataxia, dysarthria, and characteristic brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, including hyperintensity surrounding the fourth ventricle on T2-weighted images.

Embalming fluid has a high concentration of formaldehyde, and a recent epidemiologic study suggested a link between formaldehyde exposure and increased risk for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS uncommonly presents with isolated dysarthria, but its bulbar form can, usually over a much longer course than is demonstrated here. Finally, the patient’s history of melanoma places him at risk for stroke from hypercoagulability as well as potential brain metastases or carcinomatous meningitis.

Evaluation was initiated at the rehabilitation facility at the onset of the patient’s slurred speech and confusion. Physical examination were negative for focal neurologic deficits, asterixis, and jaundice. Ammonia level was 41 µmol/L (reference range, 11-35 µmol/L). Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head showed no signs of acute infarct or hemorrhage. Symptoms were attributed to hepatic encephalopathy; lactulose was up-titrated to ensure 2 or 3 bowel movements per day, and rifaximin was started.

Hyperammonemia is a cause of non-inflammatory relapsing encephalopathy, but an elevated level is neither a sensitive nor specific indicator of hepatic encephalopathy. Levels of ammonia can fluctuate widely during the day based on the frequency of bowel movements as well as dietary protein intake. In addition, proper handling of samples with prompt delivery to the laboratory is essential to minimize errors.

The ammonia level of 41 µmol/L discovered here is only modestly elevated, but given the patient’s history of TIPS as well as the clinical picture, it is reasonable to aggressively treat hepatic encephalopathy with lactulose to reduce ammonia levels. If he does not improve, an MRI of the brain to exclude a structural lesion and spinal fluid examination looking for inflammatory or infectious conditions would be important next steps. Although CT excludes a large hemorrhage or mass, this screening examination does not visualize many of the findings of the metabolic etiology and the other etiologies under consideration here.

Despite 3 days of therapy for presumed hepatic encephalopathy, the patient’s slurred speech worsened, and he was transferred to an academic tertiary care center for further evaluation. On admission, his temperature was 36.9°C, heart rate was 80 beats per minute, blood pressure was 139/67 mm Hg, respiratory rate was 10 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. He was alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He was not jaundiced. He exhibited a moderate dysarthria characterized by monotone speech, decreased volume, decreased breath support, and a hoarse vocal quality with intact language function. Motor control of the lips, tongue, and mandible were normal. Motor strength was 5/5 bilaterally in the upper and lower extremities with the exception of right hip flexion, which was 4/5. The patient exhibited mild bilateral dysmetria on finger-to-nose examination, consistent with appendicular ataxia of the upper extremities. Reflexes were depressed throughout, and there was no asterixis. He had 2+ pulses in all extremities and 1+ pitting edema of the right lower extremity to the mid leg. Pulmonary examination revealed inspiratory crackles at the left base. The rest of the examination findings were normal.

The patient’s altered mental state appears to have resolved, and the neurological examination is now mainly characterized by signs that point to the cerebellum. The description of monotone speech typically refers to loss of prosody, the variable stress or intonation of speech, which is characteristic of a cerebellar speech pattern. The hoarseness should be explored to determine if it is a feature of the patient’s speech or is a separate process. Hoarseness may involve the vocal cord and therefore, potentially, cranial nerve X or its nuclei in the brainstem. The appendicular ataxia of the limbs points definitively to the cerebellar hemispheres or their pathways through the brainstem.

Unilateral lower extremity edema, especially in the context of a recent fracture, raises the possibility of deep vein thrombosis. If this patient has a right-to-left intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunt, embolization could lead to an ischemic stroke of the brainstem or cerebellum, potentially causing dysarthria.

Laboratory evaluation revealed hemoglobin level of 10.9 g/dL, white blood cell count of 5.3 × 10 9 /L, platelet count of 169 × 10 9 /L, glucose level of 177 mg/dL, corrected calcium level of 9.0 mg/dL, sodium level of 135 mmol/L, bicarbonate level of 30 mmol/L, creatinine level of 0.9 mg/dL, total bilirubin level of 1.3 mg/dL, direct bilirubin level of 0.4 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase level of 503 U/L, alanine aminotransferase level of 12 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase level of 33 U/L, ammonia level of 49 µmol/L (range, 0-30 µ mol/L), international normalized ratio of 1.2, and troponin level of <0.01 ng/mL. Electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm.

Some patients with bacterial meningitis do not have a leukocytosis, but patients with meningitis caused by seeding from a systemic infection nearly always do. In this patient’s case, lack of a leukocytosis makes bacterial meningitis very unlikely. The elevated alkaline phosphatase level is expected, as this level peaks about 3 weeks after a long-bone fracture and returns to normal over a few months.

Non-contrast CT scan of the head performed on admission demonstrated no large vessel cortical-based infarct, intracranial hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, mass effect, midline shift, or extra-axial fluid. There was mild cortical atrophy as well as very mild periventricular white matter hypodensity.

The atrophy and mild white-matter hypodensities seen on repeat noncontrast CT are nonspecific for any particular entity in this patient’s age group. MRI is more effective in evaluating toxic encephalopathies, including metronidazole toxicity or Wernicke encephalopathy, and in characterizing small infarcts or inflammatory conditions of the brainstem and cerebellum, which are poorly evaluated by CT due to the bone surrounded space of the posterior fossa. An urgent lumbar puncture is not necessary due to the slow pace of illness, lack of fever, nuchal rigidity, or serum elevated white blood cell count. Rather, performing MRI should be prioritized. If MRI is nondiagnostic, then spinal fluid should be evaluated for evidence of an infectious, autoimmune, paraneoplastic, or neoplastic process.

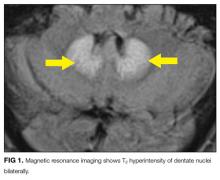

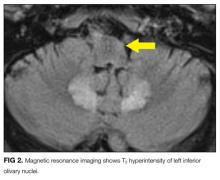

MRI was subsequently performed. It showed symmetric abnormal T2 hyperintensities involving dentate nuclei (Figure 1), left inferior olivary nuclei (Figure 2), restiform bodies, pontine tegmentum, superior cerebellar peduncles, oculomotor nuclei, and subthalamic nuclei. The most prominent hyperintensity was in the dentate nuclei.

The clinical and radiographic features confirm a diagnosis of metronidazole-associated CNS neurotoxicity. The reason for the predilection for edema in these specific areas of the brainstem and midline cerebellum is unclear but likely is related to selective neuronal vulnerability in these structures. The treatment is to stop metronidazole. In addition, the fluctuating mental status should be evaluated with electroencephalogram to ensure concomitant seizures are not occurring.

These MRI findings were consistent with metronidazole toxicity. Metronidazole was discontinued, and 2 days later the patient’s speech improved. Two weeks after medication discontinuation, his speech was normal. There were no more episodes of confusion.

DISCUSSION

Metronidazole was originally developed in France during the 1950s as an anti-parasitic medication to treat trichomonas infections. In 1962, its antibacterial properties were discovered after a patient with bacterial gingivitis improved while taking metronidazole for treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis.1 Since that time metronidazole has become a first-line treatment for anaerobic bacteria and is now recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America2 and the American College of Gastroenterology3 as a first-line therapy for mild and moderate C difficile infections.

Common side effects of metronidazole are nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, diarrhea, headaches, peripheral neuropathy, and metallic taste; less common is CNS toxicity. Although the incidence of CNS toxicity is unknown, a systematic review of the literature found 64 cases reported between 1965 and 2011.4 CNS toxicity most often occurs between the fifth and sixth decades of life, and about two thirds of the people affected are men.4 CNS adverse effects characteristically fall into 4 categories: cerebellar dysfunction (eg, ataxia, dysarthria, dysmetria, nystagmus; 75%), AMS (33%), seizures (13%), and a combination of the first 3 categories.4

The exact mechanism of metronidazole CNS toxicity is unknown, but vasogenic or cytotoxic edema may be involved.5,6 Other potential etiologies are neural protein inhibition, reversible mitochondrial dysfunction, and modifications of the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor in the cerebellum.7,8 There is no known genetic predisposition. Although the risk for CNS toxicity traditionally is thought to correlate with therapy duration and cumulative dose,7,9 in 2011 a systemic review found no significant correlation.4 In fact, 26% of patients with CNS toxicity were treated with metronidazole for less than 1 week at time of diagnosis.4

Brain CT is typically normal. On brain MRI, lesions most commonly appear as bilateral symmetric T2 hyperintensities, most often in the cerebellar dentate nuclei (85%) and less often in the midbrain (55%), the splenium of the corpus callosum (50%), the pons (35%), and the medulla (30%).4,10 Radiographic changes have been noted as early as 3 days after symptom onset. Based on damage severity and area affected (white or gray matter), vasogenic edema and cytotoxic edema may in combination be contributing to MRI abnormalities.6,10 Hyperintensities of the bilateral dentate nuclei can help in distinguishing metronidazole-induced encephalopathy from other potential disease processes, such as Wernicke encephalopathy.10

The prognosis for patients with metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity is favorable if metronidazole is discontinued. Approximately two-thirds of patients will have complete resolution of symptoms, which is more commonly observed when patients present with seizures or altered mental status. Approximately one-third will show partial improvement, particularly if the symptoms are due to cerebellar dysfunction. It is rare to experience permanent damage or death.4 Neurologic recovery usually begins within a week after medication discontinuation but may take months for complete recovery to occur.6,8,9,11 Follow-up imaging typically shows reversal of the original lesions, but this does not always correlate with symptom improvement.4,10

Despite its frequent use and long history, metronidazole can have potentially severe toxicity. When patients who are taking this medication present with new signs and symptoms of CNS dysfunction, hospitalists should include metronidazole CNS toxicity in the differential diagnosis and, if they suspect toxicity, have a brain MRI performed. Hospitalists often prescribe metronidazole because of the increasing number of patients being discharged from acute-care hospitals with a diagnosis of C difficile colitis.12 Brain MRI remains the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis. Discontinuation of metronidazole is usually salutary in reversing symptoms. Being keenly aware of this toxicity will help clinicians avoid being rendered speechless by a patient rendered speechless.

TEACHING POINTS

CNS toxicity is a rare but potentially devastating side effect of metronidazole exposure.

Metronidazole CNS adverse effects characteristically fall under 4 categories:

○ Cerebellar dysfunction, such as ataxia, dysarthria, dysmetria, or nystagmus (75%).

○ AMS (33%).

○ Seizures (13%).

○ A combination of the first 3 categories.

- Typically lesions indicating metronidazole toxicity on brain MRI are bilateral symmetric hyperintensities on T2-weighted imaging in the cerebellar dentate nuclei, corpus callosum, midbrain, pons, or medulla.

- Treatment of CNS toxicity is metronidazole discontinuation, which results in a high rate of symptom resolution.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Samuelson J. Why metronidazole is active against both bacteria and parasites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(7):1533-1541. PubMed

2. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455. PubMed

3. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(4):478-498. PubMed

4. Kuriyama A, Jackson JL, Doi A, Kamiya T. Metronidazole-induced central nervous system toxicity: a systemic review. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(6):241-247. PubMed

5. Graves TD, Condon M, Loucaidou M, Perry RJ. Reversible metronidazole-induced cerebellar toxicity in a multiple transplant recipient. J Neurol Sci. 2009;285(1-2):238-240. PubMed

6. Kim DW, Park JM, Yoon BW, Baek MJ, Kim JE, Kim S. Metronidazole-induced encephalopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2004;224(1-2):107-111. PubMed

7. Park KI, Chung JM, Kim JY. Metronidazole neurotoxicity: sequential neuroaxis involvement. Neurol India. 2011;59(1):104-107. PubMed

8. Patel K, Green-Hopkins I, Lu S, Tunkel AR. Cerebellar ataxia following prolonged use of metronidazole: case report and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(6):e111-e114. PubMed

9. Chandak S, Agarwal A, Shukla A, Joon P. A case report of metronidazole induced neurotoxicity in liver abscess patient and the usefulness of MRI for its diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(1):TD06-TD07. PubMed

10. Kim E, Na DG, Kim EY, Kim JH, Son KR, Chang KH. MR imaging of metronidazole-induced encephalopathy: lesion distribution and diffusion-weighted imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(9):1652-1658. PubMed

11. Chacko J, Pramod K, Sinha S, et al. Clinical, neuroimaging and pathological features of 5-nitroimidazole-induced encephalo-neuropathy in two patients: insights into possible pathogenesis. Neurol India. 2011;59(5):743-747. PubMed

12. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e1-e3. PubMed

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 63-year-old man at an inpatient rehabilitation center was transferred to an academic tertiary care center for evaluation of slurred speech and episodic confusion. He was accompanied by his wife, who provided the history. Three weeks earlier, the patient had fallen, sustaining a right femur fracture. He underwent surgery and was discharged to rehabilitation on postoperative day 3. During the second week of rehabilitation, he developed a cough and low-grade fevers, which prompted treatment with cefpodoxime for 5 days for presumed pneumonia. The day after completing antimicrobial therapy, he became confused and began to slur his words.

Confusion is a nonspecific symptom that typically has a diffuse or multifocal localization within the cerebral hemispheres and is unlikely to be caused by a single lesion. Slurred speech may accompany global metabolic dysfunction. However, slurred speech typically localizes to the brainstem, the cerebellum in the posterior fossa, the nuclei, or the course of cranial nerves VII, X, or XII, including where these nerves pass through the subarachnoid space.

It seems this patient’s new neurologic symptoms have some relationship to his fall. Long-bone fractures and altered mental status (AMS) lead to consideration of fat emboli, but this syndrome typically presents in the acute period after the fracture. The patient is at risk for a number of complications, related to recent surgery and hospitalization, that could affect the central nervous system (CNS), including systemic infection (possibly with associated meningeal involvement) and venous thromboembolism with concomitant stroke by paradoxical emboli. The episodic nature of the confusion leads to consideration of seizures from structural lesions in the brain. Finally, the circumstances of the fall itself should be explored to determine whether an underlying neurologic dysfunction led to imbalance and gait difficulty.

Over the next 3 days at the inpatient rehabilitation center, the patient’s slurred speech became unintelligible, and he experienced intermittent disorientation to person, place, and time. There was no concomitant fever, dizziness, headache, neck pain, weakness, dyspnea, diarrhea, dysuria, or change in hearing or vision.

Progressive dysarthria argues for an expanding lesion in the posterior fossa, worsening metabolic disturbance, or a problem affecting the cranial nerves (eg, Guillain-Barré syndrome) or neuromuscular junctions (eg, myasthenia gravis). Lack of headache makes a CNS localization less likely, though disorientation must localize to the brain itself. The transient nature of the AMS could signal an ictal phenomenon or a fluctuating toxic or metabolic condition, such as hyperammonemia, drug reaction, or healthcare–acquired delirium.

His past medical history included end-stage liver disease secondary to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis status post transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure three years prior, hepatic encephalopathy, diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, previous melanoma excision on his back, and recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis. Two years prior to admission he had been started on an indefinite course of metronidazole 500 mg twice daily without any recurrence. The patient’s other medications were aspirin, furosemide, insulin, lactulose, mirtazapine, pantoprazole, propranolol, spironolactone, and zinc. At the rehabilitation center, he was prescribed oral oxycodone 5 mg as needed every 4 hours for pain. He denied use of tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drugs. He previously worked as a funeral home director and embalmer.

Hyperammonemia and hepatic encephalopathy can present with a fluctuating mental state that often correlates to dietary protein intake or the frequency of bowel movements; the previous TIPS history places the patient at further risk. Use of oxycodone or another narcotic commonly leads to confusion, , especially in patients who are older, have preexisting cognitive decline, or have concomitant medical comorbidities. Mirtazapine and propranolol have been associated more rarely with encephalopathy, and therefore a careful history of adherence, drug interactions, and appropriate dosing should be obtained. Metronidazole is most often associated neurologically with a peripheral neuropathy; however, it is increasingly recognized that some patients can develop a CNS syndrome that features an AMS, which can be severe and accompanied by ataxia, dysarthria, and characteristic brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, including hyperintensity surrounding the fourth ventricle on T2-weighted images.

Embalming fluid has a high concentration of formaldehyde, and a recent epidemiologic study suggested a link between formaldehyde exposure and increased risk for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS uncommonly presents with isolated dysarthria, but its bulbar form can, usually over a much longer course than is demonstrated here. Finally, the patient’s history of melanoma places him at risk for stroke from hypercoagulability as well as potential brain metastases or carcinomatous meningitis.

Evaluation was initiated at the rehabilitation facility at the onset of the patient’s slurred speech and confusion. Physical examination were negative for focal neurologic deficits, asterixis, and jaundice. Ammonia level was 41 µmol/L (reference range, 11-35 µmol/L). Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head showed no signs of acute infarct or hemorrhage. Symptoms were attributed to hepatic encephalopathy; lactulose was up-titrated to ensure 2 or 3 bowel movements per day, and rifaximin was started.

Hyperammonemia is a cause of non-inflammatory relapsing encephalopathy, but an elevated level is neither a sensitive nor specific indicator of hepatic encephalopathy. Levels of ammonia can fluctuate widely during the day based on the frequency of bowel movements as well as dietary protein intake. In addition, proper handling of samples with prompt delivery to the laboratory is essential to minimize errors.

The ammonia level of 41 µmol/L discovered here is only modestly elevated, but given the patient’s history of TIPS as well as the clinical picture, it is reasonable to aggressively treat hepatic encephalopathy with lactulose to reduce ammonia levels. If he does not improve, an MRI of the brain to exclude a structural lesion and spinal fluid examination looking for inflammatory or infectious conditions would be important next steps. Although CT excludes a large hemorrhage or mass, this screening examination does not visualize many of the findings of the metabolic etiology and the other etiologies under consideration here.

Despite 3 days of therapy for presumed hepatic encephalopathy, the patient’s slurred speech worsened, and he was transferred to an academic tertiary care center for further evaluation. On admission, his temperature was 36.9°C, heart rate was 80 beats per minute, blood pressure was 139/67 mm Hg, respiratory rate was 10 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. He was alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He was not jaundiced. He exhibited a moderate dysarthria characterized by monotone speech, decreased volume, decreased breath support, and a hoarse vocal quality with intact language function. Motor control of the lips, tongue, and mandible were normal. Motor strength was 5/5 bilaterally in the upper and lower extremities with the exception of right hip flexion, which was 4/5. The patient exhibited mild bilateral dysmetria on finger-to-nose examination, consistent with appendicular ataxia of the upper extremities. Reflexes were depressed throughout, and there was no asterixis. He had 2+ pulses in all extremities and 1+ pitting edema of the right lower extremity to the mid leg. Pulmonary examination revealed inspiratory crackles at the left base. The rest of the examination findings were normal.

The patient’s altered mental state appears to have resolved, and the neurological examination is now mainly characterized by signs that point to the cerebellum. The description of monotone speech typically refers to loss of prosody, the variable stress or intonation of speech, which is characteristic of a cerebellar speech pattern. The hoarseness should be explored to determine if it is a feature of the patient’s speech or is a separate process. Hoarseness may involve the vocal cord and therefore, potentially, cranial nerve X or its nuclei in the brainstem. The appendicular ataxia of the limbs points definitively to the cerebellar hemispheres or their pathways through the brainstem.

Unilateral lower extremity edema, especially in the context of a recent fracture, raises the possibility of deep vein thrombosis. If this patient has a right-to-left intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunt, embolization could lead to an ischemic stroke of the brainstem or cerebellum, potentially causing dysarthria.

Laboratory evaluation revealed hemoglobin level of 10.9 g/dL, white blood cell count of 5.3 × 10 9 /L, platelet count of 169 × 10 9 /L, glucose level of 177 mg/dL, corrected calcium level of 9.0 mg/dL, sodium level of 135 mmol/L, bicarbonate level of 30 mmol/L, creatinine level of 0.9 mg/dL, total bilirubin level of 1.3 mg/dL, direct bilirubin level of 0.4 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase level of 503 U/L, alanine aminotransferase level of 12 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase level of 33 U/L, ammonia level of 49 µmol/L (range, 0-30 µ mol/L), international normalized ratio of 1.2, and troponin level of <0.01 ng/mL. Electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm.

Some patients with bacterial meningitis do not have a leukocytosis, but patients with meningitis caused by seeding from a systemic infection nearly always do. In this patient’s case, lack of a leukocytosis makes bacterial meningitis very unlikely. The elevated alkaline phosphatase level is expected, as this level peaks about 3 weeks after a long-bone fracture and returns to normal over a few months.

Non-contrast CT scan of the head performed on admission demonstrated no large vessel cortical-based infarct, intracranial hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, mass effect, midline shift, or extra-axial fluid. There was mild cortical atrophy as well as very mild periventricular white matter hypodensity.

The atrophy and mild white-matter hypodensities seen on repeat noncontrast CT are nonspecific for any particular entity in this patient’s age group. MRI is more effective in evaluating toxic encephalopathies, including metronidazole toxicity or Wernicke encephalopathy, and in characterizing small infarcts or inflammatory conditions of the brainstem and cerebellum, which are poorly evaluated by CT due to the bone surrounded space of the posterior fossa. An urgent lumbar puncture is not necessary due to the slow pace of illness, lack of fever, nuchal rigidity, or serum elevated white blood cell count. Rather, performing MRI should be prioritized. If MRI is nondiagnostic, then spinal fluid should be evaluated for evidence of an infectious, autoimmune, paraneoplastic, or neoplastic process.

MRI was subsequently performed. It showed symmetric abnormal T2 hyperintensities involving dentate nuclei (Figure 1), left inferior olivary nuclei (Figure 2), restiform bodies, pontine tegmentum, superior cerebellar peduncles, oculomotor nuclei, and subthalamic nuclei. The most prominent hyperintensity was in the dentate nuclei.

The clinical and radiographic features confirm a diagnosis of metronidazole-associated CNS neurotoxicity. The reason for the predilection for edema in these specific areas of the brainstem and midline cerebellum is unclear but likely is related to selective neuronal vulnerability in these structures. The treatment is to stop metronidazole. In addition, the fluctuating mental status should be evaluated with electroencephalogram to ensure concomitant seizures are not occurring.

These MRI findings were consistent with metronidazole toxicity. Metronidazole was discontinued, and 2 days later the patient’s speech improved. Two weeks after medication discontinuation, his speech was normal. There were no more episodes of confusion.

DISCUSSION

Metronidazole was originally developed in France during the 1950s as an anti-parasitic medication to treat trichomonas infections. In 1962, its antibacterial properties were discovered after a patient with bacterial gingivitis improved while taking metronidazole for treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis.1 Since that time metronidazole has become a first-line treatment for anaerobic bacteria and is now recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America2 and the American College of Gastroenterology3 as a first-line therapy for mild and moderate C difficile infections.

Common side effects of metronidazole are nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, diarrhea, headaches, peripheral neuropathy, and metallic taste; less common is CNS toxicity. Although the incidence of CNS toxicity is unknown, a systematic review of the literature found 64 cases reported between 1965 and 2011.4 CNS toxicity most often occurs between the fifth and sixth decades of life, and about two thirds of the people affected are men.4 CNS adverse effects characteristically fall into 4 categories: cerebellar dysfunction (eg, ataxia, dysarthria, dysmetria, nystagmus; 75%), AMS (33%), seizures (13%), and a combination of the first 3 categories.4

The exact mechanism of metronidazole CNS toxicity is unknown, but vasogenic or cytotoxic edema may be involved.5,6 Other potential etiologies are neural protein inhibition, reversible mitochondrial dysfunction, and modifications of the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor in the cerebellum.7,8 There is no known genetic predisposition. Although the risk for CNS toxicity traditionally is thought to correlate with therapy duration and cumulative dose,7,9 in 2011 a systemic review found no significant correlation.4 In fact, 26% of patients with CNS toxicity were treated with metronidazole for less than 1 week at time of diagnosis.4

Brain CT is typically normal. On brain MRI, lesions most commonly appear as bilateral symmetric T2 hyperintensities, most often in the cerebellar dentate nuclei (85%) and less often in the midbrain (55%), the splenium of the corpus callosum (50%), the pons (35%), and the medulla (30%).4,10 Radiographic changes have been noted as early as 3 days after symptom onset. Based on damage severity and area affected (white or gray matter), vasogenic edema and cytotoxic edema may in combination be contributing to MRI abnormalities.6,10 Hyperintensities of the bilateral dentate nuclei can help in distinguishing metronidazole-induced encephalopathy from other potential disease processes, such as Wernicke encephalopathy.10

The prognosis for patients with metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity is favorable if metronidazole is discontinued. Approximately two-thirds of patients will have complete resolution of symptoms, which is more commonly observed when patients present with seizures or altered mental status. Approximately one-third will show partial improvement, particularly if the symptoms are due to cerebellar dysfunction. It is rare to experience permanent damage or death.4 Neurologic recovery usually begins within a week after medication discontinuation but may take months for complete recovery to occur.6,8,9,11 Follow-up imaging typically shows reversal of the original lesions, but this does not always correlate with symptom improvement.4,10

Despite its frequent use and long history, metronidazole can have potentially severe toxicity. When patients who are taking this medication present with new signs and symptoms of CNS dysfunction, hospitalists should include metronidazole CNS toxicity in the differential diagnosis and, if they suspect toxicity, have a brain MRI performed. Hospitalists often prescribe metronidazole because of the increasing number of patients being discharged from acute-care hospitals with a diagnosis of C difficile colitis.12 Brain MRI remains the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis. Discontinuation of metronidazole is usually salutary in reversing symptoms. Being keenly aware of this toxicity will help clinicians avoid being rendered speechless by a patient rendered speechless.

TEACHING POINTS

CNS toxicity is a rare but potentially devastating side effect of metronidazole exposure.

Metronidazole CNS adverse effects characteristically fall under 4 categories:

○ Cerebellar dysfunction, such as ataxia, dysarthria, dysmetria, or nystagmus (75%).

○ AMS (33%).

○ Seizures (13%).

○ A combination of the first 3 categories.

- Typically lesions indicating metronidazole toxicity on brain MRI are bilateral symmetric hyperintensities on T2-weighted imaging in the cerebellar dentate nuclei, corpus callosum, midbrain, pons, or medulla.

- Treatment of CNS toxicity is metronidazole discontinuation, which results in a high rate of symptom resolution.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 63-year-old man at an inpatient rehabilitation center was transferred to an academic tertiary care center for evaluation of slurred speech and episodic confusion. He was accompanied by his wife, who provided the history. Three weeks earlier, the patient had fallen, sustaining a right femur fracture. He underwent surgery and was discharged to rehabilitation on postoperative day 3. During the second week of rehabilitation, he developed a cough and low-grade fevers, which prompted treatment with cefpodoxime for 5 days for presumed pneumonia. The day after completing antimicrobial therapy, he became confused and began to slur his words.

Confusion is a nonspecific symptom that typically has a diffuse or multifocal localization within the cerebral hemispheres and is unlikely to be caused by a single lesion. Slurred speech may accompany global metabolic dysfunction. However, slurred speech typically localizes to the brainstem, the cerebellum in the posterior fossa, the nuclei, or the course of cranial nerves VII, X, or XII, including where these nerves pass through the subarachnoid space.

It seems this patient’s new neurologic symptoms have some relationship to his fall. Long-bone fractures and altered mental status (AMS) lead to consideration of fat emboli, but this syndrome typically presents in the acute period after the fracture. The patient is at risk for a number of complications, related to recent surgery and hospitalization, that could affect the central nervous system (CNS), including systemic infection (possibly with associated meningeal involvement) and venous thromboembolism with concomitant stroke by paradoxical emboli. The episodic nature of the confusion leads to consideration of seizures from structural lesions in the brain. Finally, the circumstances of the fall itself should be explored to determine whether an underlying neurologic dysfunction led to imbalance and gait difficulty.

Over the next 3 days at the inpatient rehabilitation center, the patient’s slurred speech became unintelligible, and he experienced intermittent disorientation to person, place, and time. There was no concomitant fever, dizziness, headache, neck pain, weakness, dyspnea, diarrhea, dysuria, or change in hearing or vision.

Progressive dysarthria argues for an expanding lesion in the posterior fossa, worsening metabolic disturbance, or a problem affecting the cranial nerves (eg, Guillain-Barré syndrome) or neuromuscular junctions (eg, myasthenia gravis). Lack of headache makes a CNS localization less likely, though disorientation must localize to the brain itself. The transient nature of the AMS could signal an ictal phenomenon or a fluctuating toxic or metabolic condition, such as hyperammonemia, drug reaction, or healthcare–acquired delirium.

His past medical history included end-stage liver disease secondary to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis status post transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure three years prior, hepatic encephalopathy, diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, previous melanoma excision on his back, and recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis. Two years prior to admission he had been started on an indefinite course of metronidazole 500 mg twice daily without any recurrence. The patient’s other medications were aspirin, furosemide, insulin, lactulose, mirtazapine, pantoprazole, propranolol, spironolactone, and zinc. At the rehabilitation center, he was prescribed oral oxycodone 5 mg as needed every 4 hours for pain. He denied use of tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drugs. He previously worked as a funeral home director and embalmer.

Hyperammonemia and hepatic encephalopathy can present with a fluctuating mental state that often correlates to dietary protein intake or the frequency of bowel movements; the previous TIPS history places the patient at further risk. Use of oxycodone or another narcotic commonly leads to confusion, , especially in patients who are older, have preexisting cognitive decline, or have concomitant medical comorbidities. Mirtazapine and propranolol have been associated more rarely with encephalopathy, and therefore a careful history of adherence, drug interactions, and appropriate dosing should be obtained. Metronidazole is most often associated neurologically with a peripheral neuropathy; however, it is increasingly recognized that some patients can develop a CNS syndrome that features an AMS, which can be severe and accompanied by ataxia, dysarthria, and characteristic brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, including hyperintensity surrounding the fourth ventricle on T2-weighted images.

Embalming fluid has a high concentration of formaldehyde, and a recent epidemiologic study suggested a link between formaldehyde exposure and increased risk for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS uncommonly presents with isolated dysarthria, but its bulbar form can, usually over a much longer course than is demonstrated here. Finally, the patient’s history of melanoma places him at risk for stroke from hypercoagulability as well as potential brain metastases or carcinomatous meningitis.

Evaluation was initiated at the rehabilitation facility at the onset of the patient’s slurred speech and confusion. Physical examination were negative for focal neurologic deficits, asterixis, and jaundice. Ammonia level was 41 µmol/L (reference range, 11-35 µmol/L). Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head showed no signs of acute infarct or hemorrhage. Symptoms were attributed to hepatic encephalopathy; lactulose was up-titrated to ensure 2 or 3 bowel movements per day, and rifaximin was started.

Hyperammonemia is a cause of non-inflammatory relapsing encephalopathy, but an elevated level is neither a sensitive nor specific indicator of hepatic encephalopathy. Levels of ammonia can fluctuate widely during the day based on the frequency of bowel movements as well as dietary protein intake. In addition, proper handling of samples with prompt delivery to the laboratory is essential to minimize errors.

The ammonia level of 41 µmol/L discovered here is only modestly elevated, but given the patient’s history of TIPS as well as the clinical picture, it is reasonable to aggressively treat hepatic encephalopathy with lactulose to reduce ammonia levels. If he does not improve, an MRI of the brain to exclude a structural lesion and spinal fluid examination looking for inflammatory or infectious conditions would be important next steps. Although CT excludes a large hemorrhage or mass, this screening examination does not visualize many of the findings of the metabolic etiology and the other etiologies under consideration here.

Despite 3 days of therapy for presumed hepatic encephalopathy, the patient’s slurred speech worsened, and he was transferred to an academic tertiary care center for further evaluation. On admission, his temperature was 36.9°C, heart rate was 80 beats per minute, blood pressure was 139/67 mm Hg, respiratory rate was 10 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. He was alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He was not jaundiced. He exhibited a moderate dysarthria characterized by monotone speech, decreased volume, decreased breath support, and a hoarse vocal quality with intact language function. Motor control of the lips, tongue, and mandible were normal. Motor strength was 5/5 bilaterally in the upper and lower extremities with the exception of right hip flexion, which was 4/5. The patient exhibited mild bilateral dysmetria on finger-to-nose examination, consistent with appendicular ataxia of the upper extremities. Reflexes were depressed throughout, and there was no asterixis. He had 2+ pulses in all extremities and 1+ pitting edema of the right lower extremity to the mid leg. Pulmonary examination revealed inspiratory crackles at the left base. The rest of the examination findings were normal.

The patient’s altered mental state appears to have resolved, and the neurological examination is now mainly characterized by signs that point to the cerebellum. The description of monotone speech typically refers to loss of prosody, the variable stress or intonation of speech, which is characteristic of a cerebellar speech pattern. The hoarseness should be explored to determine if it is a feature of the patient’s speech or is a separate process. Hoarseness may involve the vocal cord and therefore, potentially, cranial nerve X or its nuclei in the brainstem. The appendicular ataxia of the limbs points definitively to the cerebellar hemispheres or their pathways through the brainstem.

Unilateral lower extremity edema, especially in the context of a recent fracture, raises the possibility of deep vein thrombosis. If this patient has a right-to-left intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunt, embolization could lead to an ischemic stroke of the brainstem or cerebellum, potentially causing dysarthria.

Laboratory evaluation revealed hemoglobin level of 10.9 g/dL, white blood cell count of 5.3 × 10 9 /L, platelet count of 169 × 10 9 /L, glucose level of 177 mg/dL, corrected calcium level of 9.0 mg/dL, sodium level of 135 mmol/L, bicarbonate level of 30 mmol/L, creatinine level of 0.9 mg/dL, total bilirubin level of 1.3 mg/dL, direct bilirubin level of 0.4 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase level of 503 U/L, alanine aminotransferase level of 12 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase level of 33 U/L, ammonia level of 49 µmol/L (range, 0-30 µ mol/L), international normalized ratio of 1.2, and troponin level of <0.01 ng/mL. Electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm.

Some patients with bacterial meningitis do not have a leukocytosis, but patients with meningitis caused by seeding from a systemic infection nearly always do. In this patient’s case, lack of a leukocytosis makes bacterial meningitis very unlikely. The elevated alkaline phosphatase level is expected, as this level peaks about 3 weeks after a long-bone fracture and returns to normal over a few months.

Non-contrast CT scan of the head performed on admission demonstrated no large vessel cortical-based infarct, intracranial hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, mass effect, midline shift, or extra-axial fluid. There was mild cortical atrophy as well as very mild periventricular white matter hypodensity.

The atrophy and mild white-matter hypodensities seen on repeat noncontrast CT are nonspecific for any particular entity in this patient’s age group. MRI is more effective in evaluating toxic encephalopathies, including metronidazole toxicity or Wernicke encephalopathy, and in characterizing small infarcts or inflammatory conditions of the brainstem and cerebellum, which are poorly evaluated by CT due to the bone surrounded space of the posterior fossa. An urgent lumbar puncture is not necessary due to the slow pace of illness, lack of fever, nuchal rigidity, or serum elevated white blood cell count. Rather, performing MRI should be prioritized. If MRI is nondiagnostic, then spinal fluid should be evaluated for evidence of an infectious, autoimmune, paraneoplastic, or neoplastic process.

MRI was subsequently performed. It showed symmetric abnormal T2 hyperintensities involving dentate nuclei (Figure 1), left inferior olivary nuclei (Figure 2), restiform bodies, pontine tegmentum, superior cerebellar peduncles, oculomotor nuclei, and subthalamic nuclei. The most prominent hyperintensity was in the dentate nuclei.

The clinical and radiographic features confirm a diagnosis of metronidazole-associated CNS neurotoxicity. The reason for the predilection for edema in these specific areas of the brainstem and midline cerebellum is unclear but likely is related to selective neuronal vulnerability in these structures. The treatment is to stop metronidazole. In addition, the fluctuating mental status should be evaluated with electroencephalogram to ensure concomitant seizures are not occurring.

These MRI findings were consistent with metronidazole toxicity. Metronidazole was discontinued, and 2 days later the patient’s speech improved. Two weeks after medication discontinuation, his speech was normal. There were no more episodes of confusion.

DISCUSSION

Metronidazole was originally developed in France during the 1950s as an anti-parasitic medication to treat trichomonas infections. In 1962, its antibacterial properties were discovered after a patient with bacterial gingivitis improved while taking metronidazole for treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis.1 Since that time metronidazole has become a first-line treatment for anaerobic bacteria and is now recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America2 and the American College of Gastroenterology3 as a first-line therapy for mild and moderate C difficile infections.

Common side effects of metronidazole are nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, diarrhea, headaches, peripheral neuropathy, and metallic taste; less common is CNS toxicity. Although the incidence of CNS toxicity is unknown, a systematic review of the literature found 64 cases reported between 1965 and 2011.4 CNS toxicity most often occurs between the fifth and sixth decades of life, and about two thirds of the people affected are men.4 CNS adverse effects characteristically fall into 4 categories: cerebellar dysfunction (eg, ataxia, dysarthria, dysmetria, nystagmus; 75%), AMS (33%), seizures (13%), and a combination of the first 3 categories.4

The exact mechanism of metronidazole CNS toxicity is unknown, but vasogenic or cytotoxic edema may be involved.5,6 Other potential etiologies are neural protein inhibition, reversible mitochondrial dysfunction, and modifications of the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor in the cerebellum.7,8 There is no known genetic predisposition. Although the risk for CNS toxicity traditionally is thought to correlate with therapy duration and cumulative dose,7,9 in 2011 a systemic review found no significant correlation.4 In fact, 26% of patients with CNS toxicity were treated with metronidazole for less than 1 week at time of diagnosis.4

Brain CT is typically normal. On brain MRI, lesions most commonly appear as bilateral symmetric T2 hyperintensities, most often in the cerebellar dentate nuclei (85%) and less often in the midbrain (55%), the splenium of the corpus callosum (50%), the pons (35%), and the medulla (30%).4,10 Radiographic changes have been noted as early as 3 days after symptom onset. Based on damage severity and area affected (white or gray matter), vasogenic edema and cytotoxic edema may in combination be contributing to MRI abnormalities.6,10 Hyperintensities of the bilateral dentate nuclei can help in distinguishing metronidazole-induced encephalopathy from other potential disease processes, such as Wernicke encephalopathy.10

The prognosis for patients with metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity is favorable if metronidazole is discontinued. Approximately two-thirds of patients will have complete resolution of symptoms, which is more commonly observed when patients present with seizures or altered mental status. Approximately one-third will show partial improvement, particularly if the symptoms are due to cerebellar dysfunction. It is rare to experience permanent damage or death.4 Neurologic recovery usually begins within a week after medication discontinuation but may take months for complete recovery to occur.6,8,9,11 Follow-up imaging typically shows reversal of the original lesions, but this does not always correlate with symptom improvement.4,10

Despite its frequent use and long history, metronidazole can have potentially severe toxicity. When patients who are taking this medication present with new signs and symptoms of CNS dysfunction, hospitalists should include metronidazole CNS toxicity in the differential diagnosis and, if they suspect toxicity, have a brain MRI performed. Hospitalists often prescribe metronidazole because of the increasing number of patients being discharged from acute-care hospitals with a diagnosis of C difficile colitis.12 Brain MRI remains the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis. Discontinuation of metronidazole is usually salutary in reversing symptoms. Being keenly aware of this toxicity will help clinicians avoid being rendered speechless by a patient rendered speechless.

TEACHING POINTS

CNS toxicity is a rare but potentially devastating side effect of metronidazole exposure.

Metronidazole CNS adverse effects characteristically fall under 4 categories:

○ Cerebellar dysfunction, such as ataxia, dysarthria, dysmetria, or nystagmus (75%).

○ AMS (33%).

○ Seizures (13%).

○ A combination of the first 3 categories.

- Typically lesions indicating metronidazole toxicity on brain MRI are bilateral symmetric hyperintensities on T2-weighted imaging in the cerebellar dentate nuclei, corpus callosum, midbrain, pons, or medulla.

- Treatment of CNS toxicity is metronidazole discontinuation, which results in a high rate of symptom resolution.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Samuelson J. Why metronidazole is active against both bacteria and parasites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(7):1533-1541. PubMed

2. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455. PubMed

3. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(4):478-498. PubMed

4. Kuriyama A, Jackson JL, Doi A, Kamiya T. Metronidazole-induced central nervous system toxicity: a systemic review. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(6):241-247. PubMed

5. Graves TD, Condon M, Loucaidou M, Perry RJ. Reversible metronidazole-induced cerebellar toxicity in a multiple transplant recipient. J Neurol Sci. 2009;285(1-2):238-240. PubMed

6. Kim DW, Park JM, Yoon BW, Baek MJ, Kim JE, Kim S. Metronidazole-induced encephalopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2004;224(1-2):107-111. PubMed

7. Park KI, Chung JM, Kim JY. Metronidazole neurotoxicity: sequential neuroaxis involvement. Neurol India. 2011;59(1):104-107. PubMed

8. Patel K, Green-Hopkins I, Lu S, Tunkel AR. Cerebellar ataxia following prolonged use of metronidazole: case report and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(6):e111-e114. PubMed

9. Chandak S, Agarwal A, Shukla A, Joon P. A case report of metronidazole induced neurotoxicity in liver abscess patient and the usefulness of MRI for its diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(1):TD06-TD07. PubMed

10. Kim E, Na DG, Kim EY, Kim JH, Son KR, Chang KH. MR imaging of metronidazole-induced encephalopathy: lesion distribution and diffusion-weighted imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(9):1652-1658. PubMed

11. Chacko J, Pramod K, Sinha S, et al. Clinical, neuroimaging and pathological features of 5-nitroimidazole-induced encephalo-neuropathy in two patients: insights into possible pathogenesis. Neurol India. 2011;59(5):743-747. PubMed

12. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e1-e3. PubMed

1. Samuelson J. Why metronidazole is active against both bacteria and parasites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(7):1533-1541. PubMed

2. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455. PubMed

3. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(4):478-498. PubMed

4. Kuriyama A, Jackson JL, Doi A, Kamiya T. Metronidazole-induced central nervous system toxicity: a systemic review. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(6):241-247. PubMed

5. Graves TD, Condon M, Loucaidou M, Perry RJ. Reversible metronidazole-induced cerebellar toxicity in a multiple transplant recipient. J Neurol Sci. 2009;285(1-2):238-240. PubMed

6. Kim DW, Park JM, Yoon BW, Baek MJ, Kim JE, Kim S. Metronidazole-induced encephalopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2004;224(1-2):107-111. PubMed

7. Park KI, Chung JM, Kim JY. Metronidazole neurotoxicity: sequential neuroaxis involvement. Neurol India. 2011;59(1):104-107. PubMed

8. Patel K, Green-Hopkins I, Lu S, Tunkel AR. Cerebellar ataxia following prolonged use of metronidazole: case report and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(6):e111-e114. PubMed

9. Chandak S, Agarwal A, Shukla A, Joon P. A case report of metronidazole induced neurotoxicity in liver abscess patient and the usefulness of MRI for its diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(1):TD06-TD07. PubMed

10. Kim E, Na DG, Kim EY, Kim JH, Son KR, Chang KH. MR imaging of metronidazole-induced encephalopathy: lesion distribution and diffusion-weighted imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(9):1652-1658. PubMed

11. Chacko J, Pramod K, Sinha S, et al. Clinical, neuroimaging and pathological features of 5-nitroimidazole-induced encephalo-neuropathy in two patients: insights into possible pathogenesis. Neurol India. 2011;59(5):743-747. PubMed

12. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e1-e3. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Patients Overwhelmingly Prefer Inpatient Boarding to ED Boarding

Clinical question: When hallway boarding is required, do patients prefer inpatient units over the ED?

Background: ED crowding is associated with patient dissatisfaction, ambulance diversion, delays in care, medical errors, and higher mortality rates. Strategies to alleviate the problem of boarding admitted patients in the ED can include relocation to inpatient hallways while awaiting a regular hospital bed. Traditional objections to inpatient hallway boarding include concerns regarding patient satisfaction and safety.

Study design: Structured telephone survey.

Setting: Suburban, university-based, teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Patients who required boarding in the ED hallway after hospital admission were eligible for inpatient hallway boarding according to the institutional protocol, which screens for those with only mild to moderate comorbidities. Of 110 consecutive patients contacted who experienced both ED and inpatient hallway boarding, 105 consented to participate in a tested telephone survey instrument.

The overall preferred location was inpatient hallways for 85% (95% CI 75-90) of respondents. Comparing ED boarding to inpatient hallway boarding, respondents preferred inpatient boarding with regard to staff availability (84%), safety (83%), confidentiality (82%), and comfort (79%).

Study results were subject to non-response bias, because working telephone numbers were required for study inclusion, as well as recall bias, because the survey was conducted within several months after discharge. This study’s results are based on actual patient experiences, whereas prior literature relied on patients to hypothesize the preferred environment after experiencing only ED hallway boarding to predict satisfaction.

Bottom line: Boarding in inpatient hallways was associated with higher patient satisfaction compared with ED hallway boarding.

Citation: Viccellio P, Zito JA, Sayage V, et al. Patients overwhelmingly prefer inpatient boarding to emergency department boarding [published online ahead of print September 21, 2013].

Clinical question: When hallway boarding is required, do patients prefer inpatient units over the ED?

Background: ED crowding is associated with patient dissatisfaction, ambulance diversion, delays in care, medical errors, and higher mortality rates. Strategies to alleviate the problem of boarding admitted patients in the ED can include relocation to inpatient hallways while awaiting a regular hospital bed. Traditional objections to inpatient hallway boarding include concerns regarding patient satisfaction and safety.

Study design: Structured telephone survey.

Setting: Suburban, university-based, teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Patients who required boarding in the ED hallway after hospital admission were eligible for inpatient hallway boarding according to the institutional protocol, which screens for those with only mild to moderate comorbidities. Of 110 consecutive patients contacted who experienced both ED and inpatient hallway boarding, 105 consented to participate in a tested telephone survey instrument.

The overall preferred location was inpatient hallways for 85% (95% CI 75-90) of respondents. Comparing ED boarding to inpatient hallway boarding, respondents preferred inpatient boarding with regard to staff availability (84%), safety (83%), confidentiality (82%), and comfort (79%).

Study results were subject to non-response bias, because working telephone numbers were required for study inclusion, as well as recall bias, because the survey was conducted within several months after discharge. This study’s results are based on actual patient experiences, whereas prior literature relied on patients to hypothesize the preferred environment after experiencing only ED hallway boarding to predict satisfaction.

Bottom line: Boarding in inpatient hallways was associated with higher patient satisfaction compared with ED hallway boarding.

Citation: Viccellio P, Zito JA, Sayage V, et al. Patients overwhelmingly prefer inpatient boarding to emergency department boarding [published online ahead of print September 21, 2013].

Clinical question: When hallway boarding is required, do patients prefer inpatient units over the ED?

Background: ED crowding is associated with patient dissatisfaction, ambulance diversion, delays in care, medical errors, and higher mortality rates. Strategies to alleviate the problem of boarding admitted patients in the ED can include relocation to inpatient hallways while awaiting a regular hospital bed. Traditional objections to inpatient hallway boarding include concerns regarding patient satisfaction and safety.

Study design: Structured telephone survey.

Setting: Suburban, university-based, teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Patients who required boarding in the ED hallway after hospital admission were eligible for inpatient hallway boarding according to the institutional protocol, which screens for those with only mild to moderate comorbidities. Of 110 consecutive patients contacted who experienced both ED and inpatient hallway boarding, 105 consented to participate in a tested telephone survey instrument.

The overall preferred location was inpatient hallways for 85% (95% CI 75-90) of respondents. Comparing ED boarding to inpatient hallway boarding, respondents preferred inpatient boarding with regard to staff availability (84%), safety (83%), confidentiality (82%), and comfort (79%).

Study results were subject to non-response bias, because working telephone numbers were required for study inclusion, as well as recall bias, because the survey was conducted within several months after discharge. This study’s results are based on actual patient experiences, whereas prior literature relied on patients to hypothesize the preferred environment after experiencing only ED hallway boarding to predict satisfaction.

Bottom line: Boarding in inpatient hallways was associated with higher patient satisfaction compared with ED hallway boarding.

Citation: Viccellio P, Zito JA, Sayage V, et al. Patients overwhelmingly prefer inpatient boarding to emergency department boarding [published online ahead of print September 21, 2013].

Surgical Readmission Rate Variation Dependent on Surgical Volume, Surgical Mortality Rates

Clinical question: What factors determine rates of readmission after major surgery?

Background: Reducing hospital readmission rates has become a national priority. The U.S. patterns for surgical readmissions are unknown, as are the specific structural and quality characteristics of hospitals associated with lower surgical readmission rates.

Study design: Retrospective study of national Medicare data was used to calculate 30-day readmission rates for six major surgical procedures.

Setting: U.S. Hospitals, 2009-2010.

Synopsis: Six major surgical procedures were tracked by Medicare data, with 479,471 discharges from 3,004 hospitals. Structural characteristics included hospital size, teaching status, region, ownership, and proportion of patients living below the federal poverty line. Three well-established measures of surgical quality were used: the HQA surgical score, procedure volume, and 30-day mortality.

Hospitals in the highest quartile for surgical volume had a significantly lower readmission rate. Additionally, hospitals with the lowest surgical mortality rates had significantly lower readmission rates. Interestingly, high adherence to reported surgical process measures was only marginally associated with reduced admission rates. Prior studies have also shown inconsistent relationship between HQA surgical score and mortality.

Limitations to this study include inability to account for factors not captured by billing codes and the focus on a Medicare population.

Bottom line: Surgical readmission rates are associated with measures of surgical quality, specifically procedural volume and mortality.

Citation: Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Gawande AA, Jha AK. Variation in surgical-readmission rates and quality of hospital care. 2013;369(12):1134-1142.

Clinical question: What factors determine rates of readmission after major surgery?

Background: Reducing hospital readmission rates has become a national priority. The U.S. patterns for surgical readmissions are unknown, as are the specific structural and quality characteristics of hospitals associated with lower surgical readmission rates.

Study design: Retrospective study of national Medicare data was used to calculate 30-day readmission rates for six major surgical procedures.

Setting: U.S. Hospitals, 2009-2010.

Synopsis: Six major surgical procedures were tracked by Medicare data, with 479,471 discharges from 3,004 hospitals. Structural characteristics included hospital size, teaching status, region, ownership, and proportion of patients living below the federal poverty line. Three well-established measures of surgical quality were used: the HQA surgical score, procedure volume, and 30-day mortality.

Hospitals in the highest quartile for surgical volume had a significantly lower readmission rate. Additionally, hospitals with the lowest surgical mortality rates had significantly lower readmission rates. Interestingly, high adherence to reported surgical process measures was only marginally associated with reduced admission rates. Prior studies have also shown inconsistent relationship between HQA surgical score and mortality.

Limitations to this study include inability to account for factors not captured by billing codes and the focus on a Medicare population.

Bottom line: Surgical readmission rates are associated with measures of surgical quality, specifically procedural volume and mortality.

Citation: Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Gawande AA, Jha AK. Variation in surgical-readmission rates and quality of hospital care. 2013;369(12):1134-1142.

Clinical question: What factors determine rates of readmission after major surgery?

Background: Reducing hospital readmission rates has become a national priority. The U.S. patterns for surgical readmissions are unknown, as are the specific structural and quality characteristics of hospitals associated with lower surgical readmission rates.

Study design: Retrospective study of national Medicare data was used to calculate 30-day readmission rates for six major surgical procedures.

Setting: U.S. Hospitals, 2009-2010.

Synopsis: Six major surgical procedures were tracked by Medicare data, with 479,471 discharges from 3,004 hospitals. Structural characteristics included hospital size, teaching status, region, ownership, and proportion of patients living below the federal poverty line. Three well-established measures of surgical quality were used: the HQA surgical score, procedure volume, and 30-day mortality.

Hospitals in the highest quartile for surgical volume had a significantly lower readmission rate. Additionally, hospitals with the lowest surgical mortality rates had significantly lower readmission rates. Interestingly, high adherence to reported surgical process measures was only marginally associated with reduced admission rates. Prior studies have also shown inconsistent relationship between HQA surgical score and mortality.

Limitations to this study include inability to account for factors not captured by billing codes and the focus on a Medicare population.

Bottom line: Surgical readmission rates are associated with measures of surgical quality, specifically procedural volume and mortality.

Citation: Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Gawande AA, Jha AK. Variation in surgical-readmission rates and quality of hospital care. 2013;369(12):1134-1142.

Higher Continuity of Care Results in Lower Rate of Preventable Hospitalizations

Clinical question: Is continuity of care related to preventable hospitalizations among older adults?

Background: Preventable hospitalizations cost approximately $25 billion annually in the U.S. The relationship between continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, for ambulatory visits and hospital admissions.

Synopsis: This study examined 3.2 million Medicare beneficiaries using 2008-2010 claims data to measure continuity and the first preventable hospitalization. The Prevention Quality Indicators definitions and technical specifications from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality were used to identify preventable hospitalizations. Both the continuity of care score and usual provider continuity score were used to calculate continuity metrics. Baseline risk of preventable hospitalization included age, sex, race, Medicaid dual-eligible status, and residential zip code.

During a two-year period, 12.6% of patients had a preventable hospitalization. After adjusting for variables, a 0.1 increase in continuity of care was associated with about a 2% lower rate of preventable hospitalization. Interestingly, continuity of care was not related to mortality rates.

This study extends prior research associating continuity of care with reduced rate of hospitalization; however, the associations found cannot assert a causal relationship. This study used coding practices that vary throughout the country, included only older fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, and could not verify why some patients had higher continuity of care. The authors suggest that efforts to strengthen physician-patient relationships through high-quality primary care will deter some hospital admissions.

Bottom line: Higher continuity of ambulatory care is associated with lower preventable hospitalizations in Medicare beneficiaries.

Citation: Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JP, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. 2013;173(20):1879-1885.

Clinical question: Is continuity of care related to preventable hospitalizations among older adults?

Background: Preventable hospitalizations cost approximately $25 billion annually in the U.S. The relationship between continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, for ambulatory visits and hospital admissions.

Synopsis: This study examined 3.2 million Medicare beneficiaries using 2008-2010 claims data to measure continuity and the first preventable hospitalization. The Prevention Quality Indicators definitions and technical specifications from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality were used to identify preventable hospitalizations. Both the continuity of care score and usual provider continuity score were used to calculate continuity metrics. Baseline risk of preventable hospitalization included age, sex, race, Medicaid dual-eligible status, and residential zip code.

During a two-year period, 12.6% of patients had a preventable hospitalization. After adjusting for variables, a 0.1 increase in continuity of care was associated with about a 2% lower rate of preventable hospitalization. Interestingly, continuity of care was not related to mortality rates.

This study extends prior research associating continuity of care with reduced rate of hospitalization; however, the associations found cannot assert a causal relationship. This study used coding practices that vary throughout the country, included only older fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, and could not verify why some patients had higher continuity of care. The authors suggest that efforts to strengthen physician-patient relationships through high-quality primary care will deter some hospital admissions.

Bottom line: Higher continuity of ambulatory care is associated with lower preventable hospitalizations in Medicare beneficiaries.

Citation: Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JP, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. 2013;173(20):1879-1885.

Clinical question: Is continuity of care related to preventable hospitalizations among older adults?

Background: Preventable hospitalizations cost approximately $25 billion annually in the U.S. The relationship between continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, for ambulatory visits and hospital admissions.

Synopsis: This study examined 3.2 million Medicare beneficiaries using 2008-2010 claims data to measure continuity and the first preventable hospitalization. The Prevention Quality Indicators definitions and technical specifications from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality were used to identify preventable hospitalizations. Both the continuity of care score and usual provider continuity score were used to calculate continuity metrics. Baseline risk of preventable hospitalization included age, sex, race, Medicaid dual-eligible status, and residential zip code.

During a two-year period, 12.6% of patients had a preventable hospitalization. After adjusting for variables, a 0.1 increase in continuity of care was associated with about a 2% lower rate of preventable hospitalization. Interestingly, continuity of care was not related to mortality rates.

This study extends prior research associating continuity of care with reduced rate of hospitalization; however, the associations found cannot assert a causal relationship. This study used coding practices that vary throughout the country, included only older fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, and could not verify why some patients had higher continuity of care. The authors suggest that efforts to strengthen physician-patient relationships through high-quality primary care will deter some hospital admissions.

Bottom line: Higher continuity of ambulatory care is associated with lower preventable hospitalizations in Medicare beneficiaries.

Citation: Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JP, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. 2013;173(20):1879-1885.

Characteristics and Impact of Hospitalist-Staffed, Post-Discharge Clinic

Clinical question: What effect does a hospitalist-staffed, post-discharge clinic have on time to first post-hospitalization visit?

Background: Hospital discharge is a well-recognized care transition that can leave patients vulnerable to morbidity and re-hospitalization. Limited primary care access can hamper complex post-hospital follow-up. Discharge clinic models staffed by hospitalists have been developed to mitigate access issues, but research is lacking to describe their characteristics and benefits.

Study design: Single-center, prospective, observational database review.

Setting: Large, academic primary care practice affiliated with an academic medical center.