User login

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

In leveraging existing, readily available evidence-based health care information (eg, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines), clinicians have historically made recommendations based on treatment responses of the average patient.1 Recently, this approach has been expanded into data-driven, evidence-based precision medical care for individuals across a wide range of disciplines and care settings. These precision medicine approaches use information related to an individual’s genes, environment, and lifestyle to tailor recommendations regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Applying precision medicine approaches to the unique exposures and experiences of service members and veterans—particularly those who served in combat environments—through the incorporation of biopsychosocial factors into medical decision-making may be even more pertinent. This sentiment is reflected in Section 305 of the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, which outlines the Precision Medicine Initiative of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify and validate brain and mental health biomarkers.2 Despite widespread consensus regarding the promise of precision medicine, large, rich datasets with elements pertaining to common military exposures such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are limited.

Existing datasets, most of which are relatively small or focus on specific cohorts (eg, older veterans, transitioning veterans), continue to create barriers to advancing precision medicine. For example, in classically designed clinical trials, analyses are generally conducted in a manner that may obfuscate efficacy among subcohorts of individuals, thereby underscoring the need to explore alternative strategies to unify existing datasets capable of revealing such heterogeneity.3 The evidence base for precision medical care is limited, drawing from published trials with relatively small sample sizes and even larger cohort studies have limited biomarker data. Additionally, these models are often exploratory during development, and to avoid statistical overfitting of an exploratory model, validation in similar datasets is needed—an added burden when data sources are small or underpowered to begin with.

A promising approach is to combine and harmonize the largest, most deeply characterized data sources from similar samples. Although combining such datasets may appear to require minimal time and effort, harmonizing similar variables in an evidence-based and replicable manner requires time and expertise, even when participant characteristics and outcomes are similar.4-7

Challenges related to harmonization are related to the wide range of strategies (eg, self-report questionnaires, clinical interviews, electronic health record review) used to measure common brain and mental health constructs, such as depression. Even when similar methods (eg, self-report measures) are implemented, challenges persist. For example, if a study used a depression measure that focused primarily on cognitive symptoms (eg, pessimism, self-dislike, suicidal ideation) and another study used a depression measure composed of items more heavily weighted towards somatic symptoms (eg, insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, decreased libido), combining their data could be challenging, particularly if researchers, clinicians, or administrators are interested in more than dichotomous outcomes (eg, depression vs no depression).8,9

To address this knowledge gap and harmonize multimodal data from varied sources, well-planned and reproducible curation is needed. Longitudinal cohort studies of service members and veterans with military combat and training exposure histories provide researchers and other stakeholders access to extant biopsychosocial data shown to affect risk for adverse health outcomes; however, efforts to facilitate individually tailored treatment or other precision medicine approaches would benefit from the synthesis of such datasets.10

Members of the VA Total Brain Diagnostics (TBD) team are engaged in harmonizing variables from the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC)11 and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS).12-21 While there is overlap across LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS with respect to data domains, considerable data harmonization is needed to allow for future valid and meaningful analyses, particularly those involving multivariable predictors.

Data Sources

Both data sources for the TBD harmonization project, LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS, include extensive, longitudinal data collected from relatively large cohorts of veterans and service members with combat exposure. Both studies collect detailed data related to potential brain injury history and include participants with and without a history of TBI. Similarly, both include extensive collection of fluid biomarkers and imaging data, as well as measures of biopsychosocial functioning.

Data collection sites for LIMBIC-CENC include 16 recruitment sites, 9 at VA medical centers (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego) and 7 at military treatment sites (Alexandria, San Diego, Tampa, Tacoma, Columbia, Coronado, Hinesville), in addition to 11 assessment sites (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego, Alexandria, Augusta). Data for TRACTS are collected at sites in Boston and Houston.

LIMBIC-CENC is a 12-year, 17-site cohort of service members and veteran participants with combat exposure who are well characterized at baseline and undergo annual reassessments. As of December 2025, > 3100 participants have been recruited, and nearly 90% remain in follow-up. Data collection includes > 6200 annual follow-up evaluations and > 1550 5-year re-evaluations, with 400 enrolled participants followed up annually.

TRACTS is a 16-year, 2-site cohort of veterans with combat exposure who complete comprehensive assessments at enrollment, undergo annual reassessments, and complete comprehensive reassessment every 5 years thereafter. As of December 2025, > 1075 participants have completed baseline (Time 1) assessments, > 600 have completed the 2-year re-evaluation (Time 2), > 175 have completed the 5-year re-evaluation (Time 3), and > 35 have completed 10-year evaluations (Time 4), with about 50 new participants added and 100 enrolled participants followed up annually. More data on participant characteristics are available for both LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS in previous publications.11,22These 2 ongoing, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of service members and veterans offer access to a wide range of potential risk factors that can affect response to care and outcomes, including demographics (eg, age, sex), injury characteristics (eg, pre-exposure factors, exposure factors), biomarkers (eg, serum, saliva, brain imaging, evoked potentials), and functional measures (eg, computerized posturography, computerized eye tracking, sensory testing, clinical examination, neuropsychological assessments, symptom questionnaires).

Harmonization Strategy

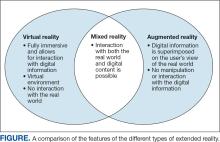

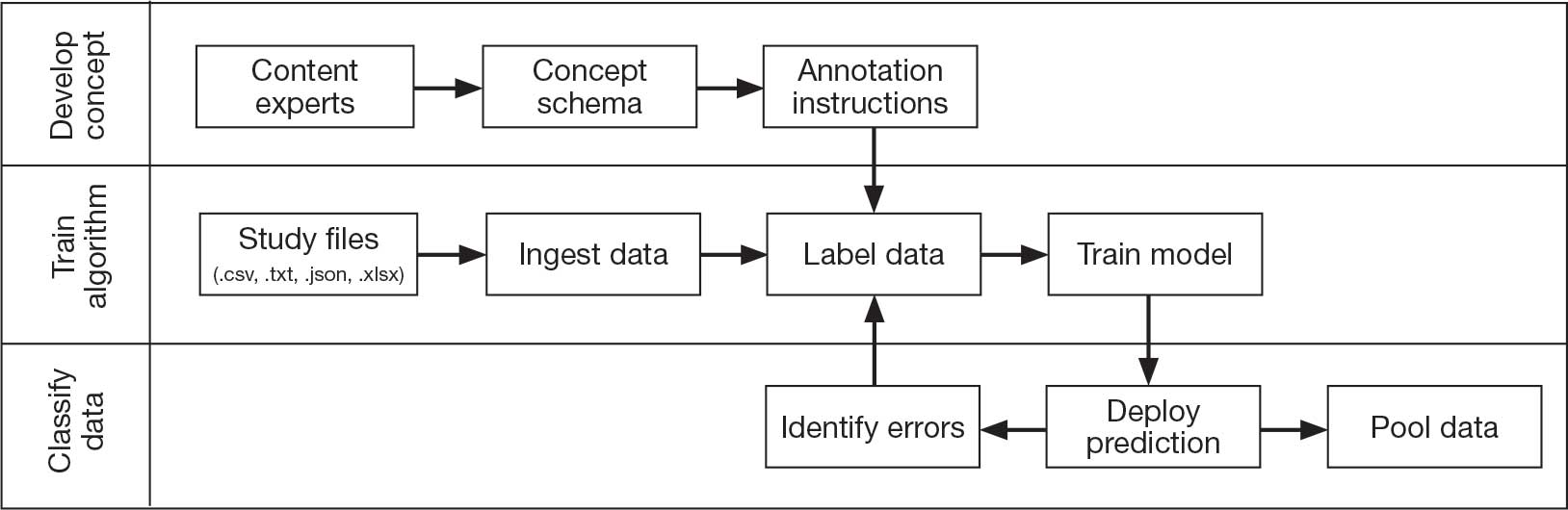

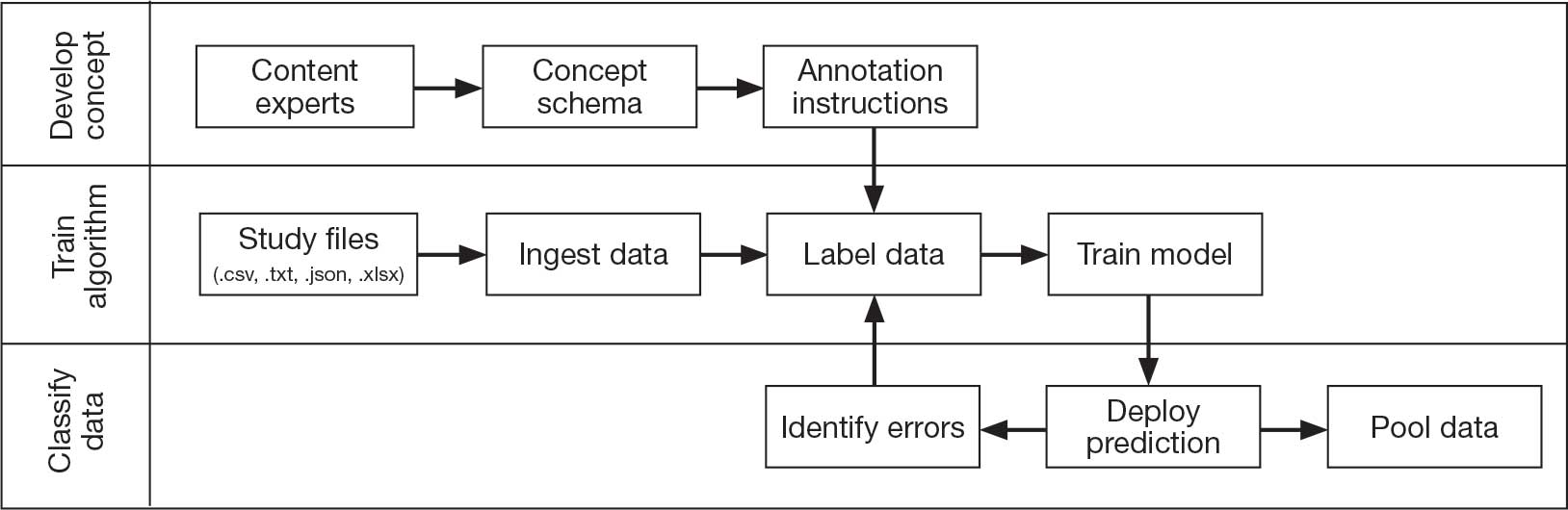

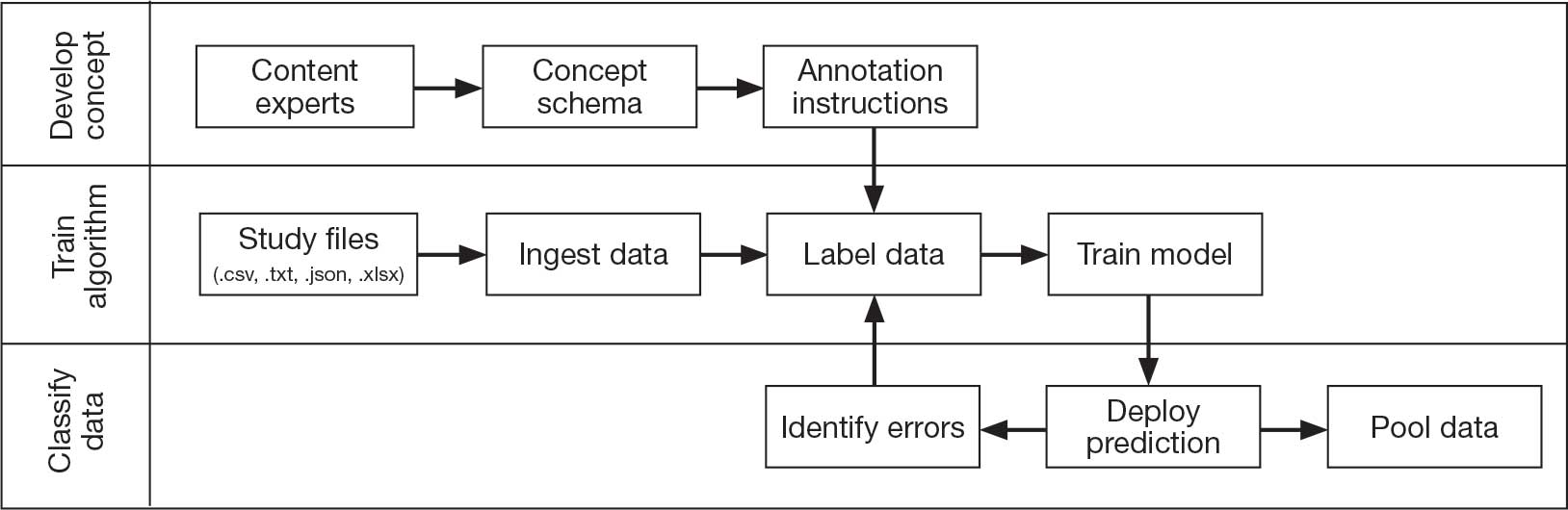

Pooling and harmonizing data from large studies evaluating similar participant cohorts and conditions involves numerous steps to appropriately handle a variety of measurements and disparate variable names. The TBD team adapted a model data harmonization system developed by O’Neil et al through initial work harmonizing the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System (FITBIR).4-7 This process was expanded and generalized by the research team to combine data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to create a single pooled dataset for analysis (Figure).

Injury Research database.

This approach was selected because it accommodates heterogeneous study designs (eg, cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control), data collection methods (eg, clinical assessment, self-reported, objective blood, and imaging biomarkers), and various assessments of the same construct (ie, different measures of brain injury). While exact matches for data collection methods and measures may be easily harmonized, the timing of assessment, number of assessments, assessment tool version, and other factors must be considered. The goal was to harmonize data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to allow additional data sources to be harmonized and incorporated in the future.

Original data files from each study were reshaped to represent participant-level observations with 1 unique measurement per row. The measurement represents what information was collected and the value recorded represents the unique observation. These data are linked to metadata from the original study, which includes the study’s definition of each measurement, how it was collected, and any available information regarding when it was collected in reference to study enrollment or injury. Additional information on the file source, row, and column position of each data point was added to enable recreation of the original data as needed.

The resulting dataset was used to harmonize measurements from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS into a priori-defined schemas for brain- and mental health-relevant concepts, including TBI severity, PTSD, substance use, depression, suicidal ideation, and functioning (including cognitive, physical, and social functioning). This process was facilitated using natural language processing (NLP). Each study uniquely defines all measurements and provides written definitions with the data. Measurement definitions serve as records describing what was collected, how it was collected, and how the study may have uniquely defined information for its purposes. For example, definitions of exposure to brain injury and severity of brain injury may differ between studies, and the study-provided definition defines these differences.

Definitions were converted into numeric vectors through sentence embedding, a process that preserves the semantic meaning of the definition.23 Cosine similarity was used as the primary metric to compare the semantic textual similarity between pairs of measurement definitions. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no meaningful similarity and 1 indicates they have identical meanings.24 This approach leverages the relationship between the definitions of each measurement provided by a study and enables quick comparison of all pairwise combinations of measurement definitions between studies.

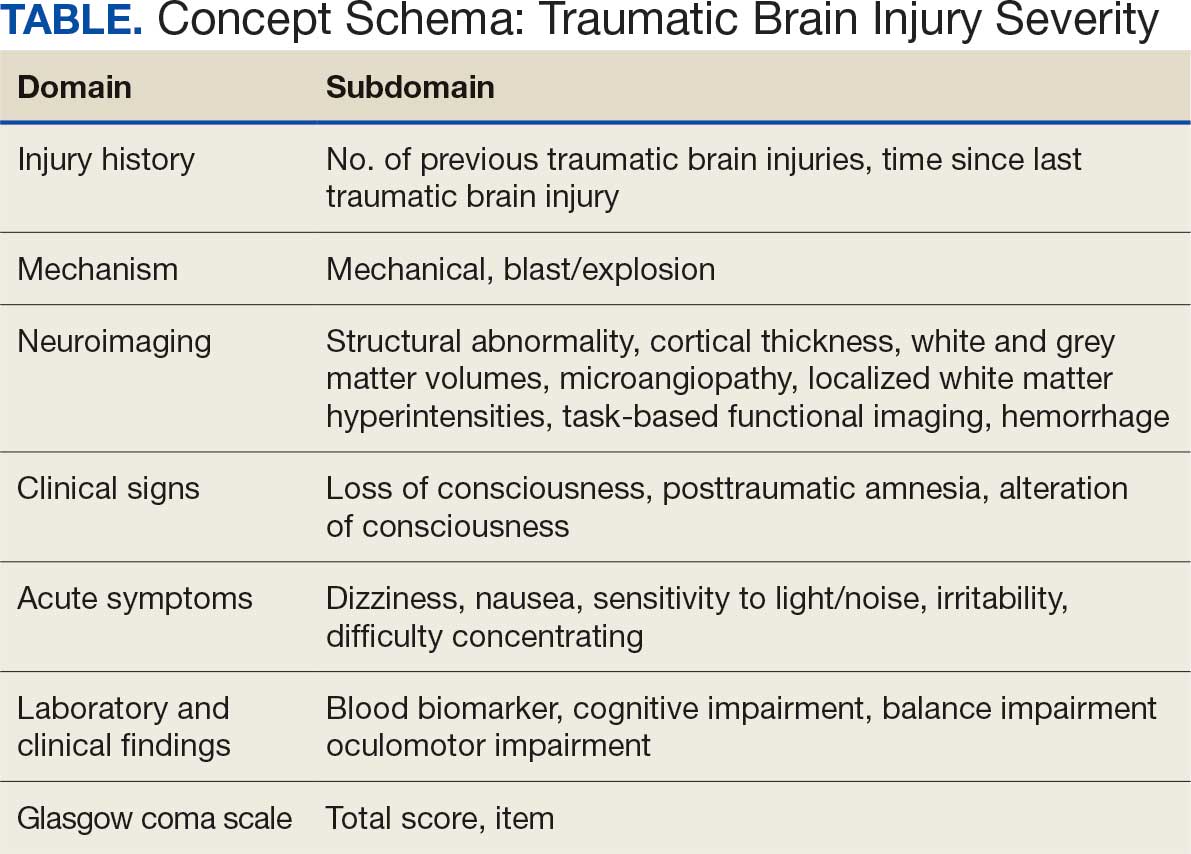

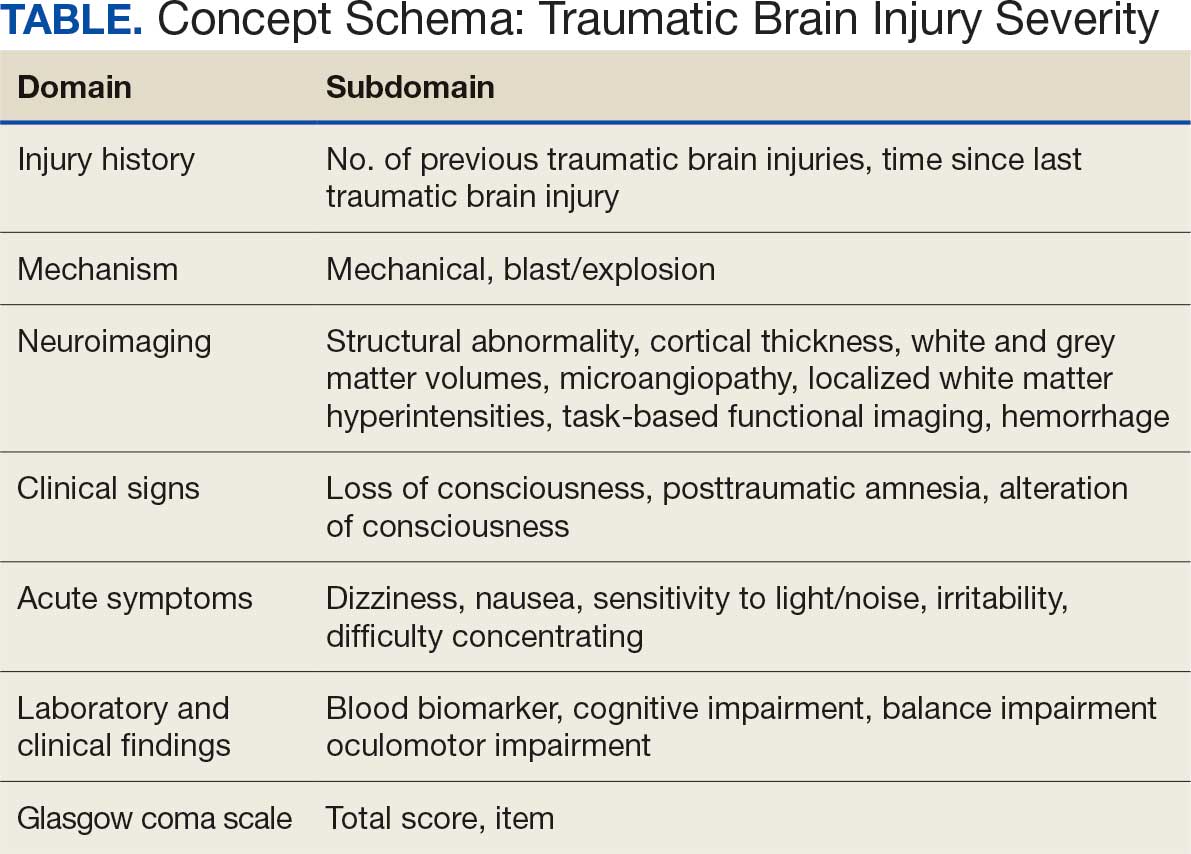

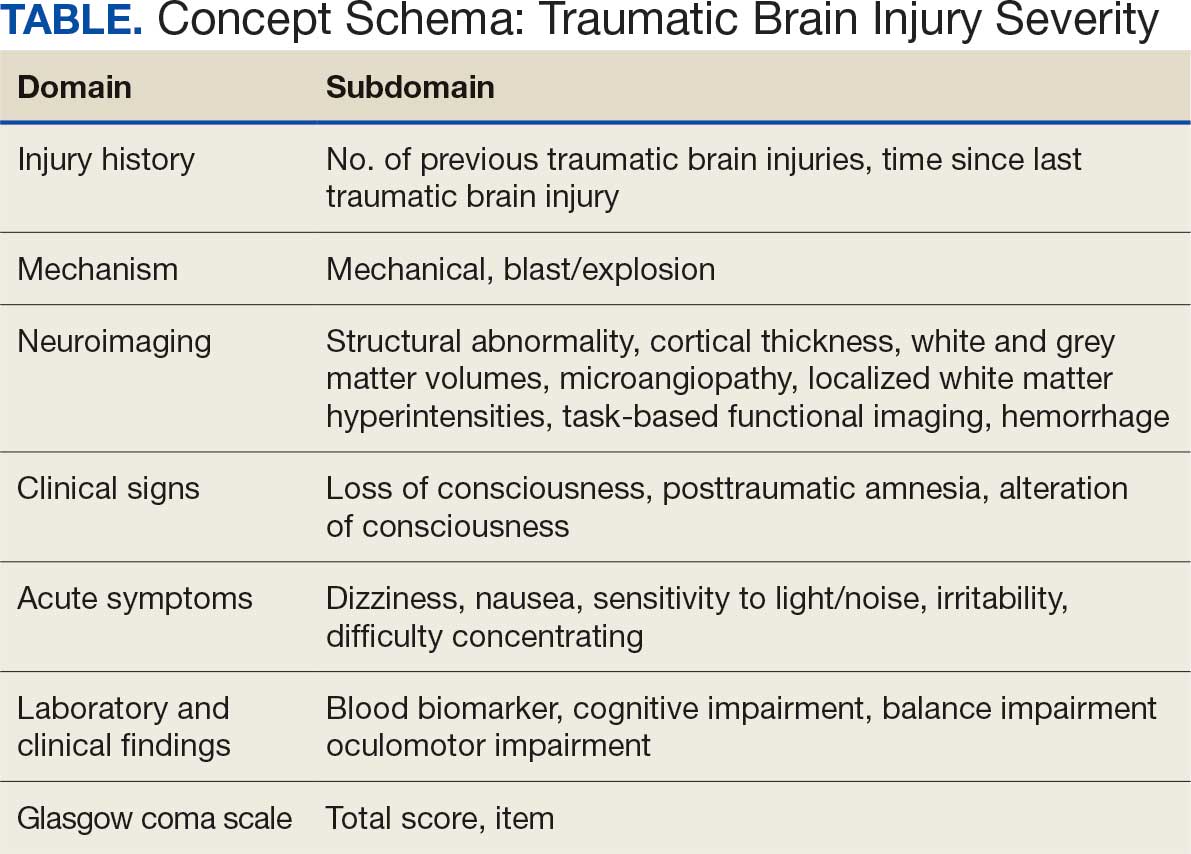

Subsets of similar measurements across studies were organized into a priori-defined schema. Clinical experts then reviewed each schema and further refined them into domains, (eg, mechanism of injury, clinical signs, acute symptoms) and subdomains (children), such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, and alteration of consciousness. This approach allows efficient handling of 2 specific cases that commonly occur when pooling and harmonizing datasets: (1) identifying the same measurement with differing names; and (2) identifying different measurements with definitions that each relate to the same domain.

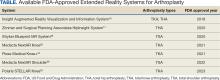

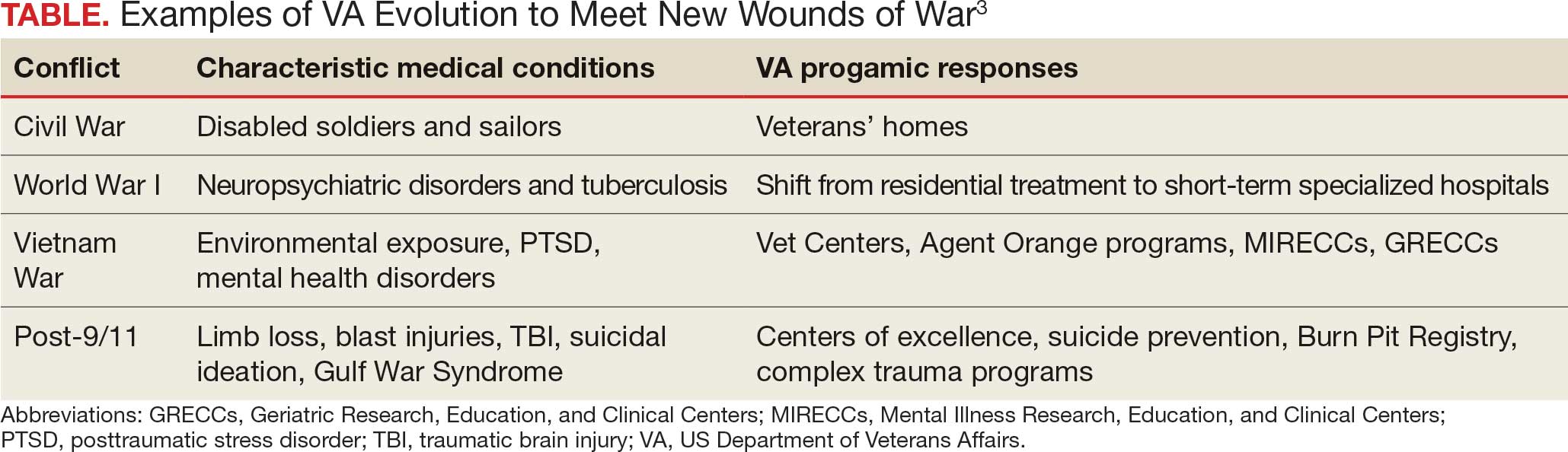

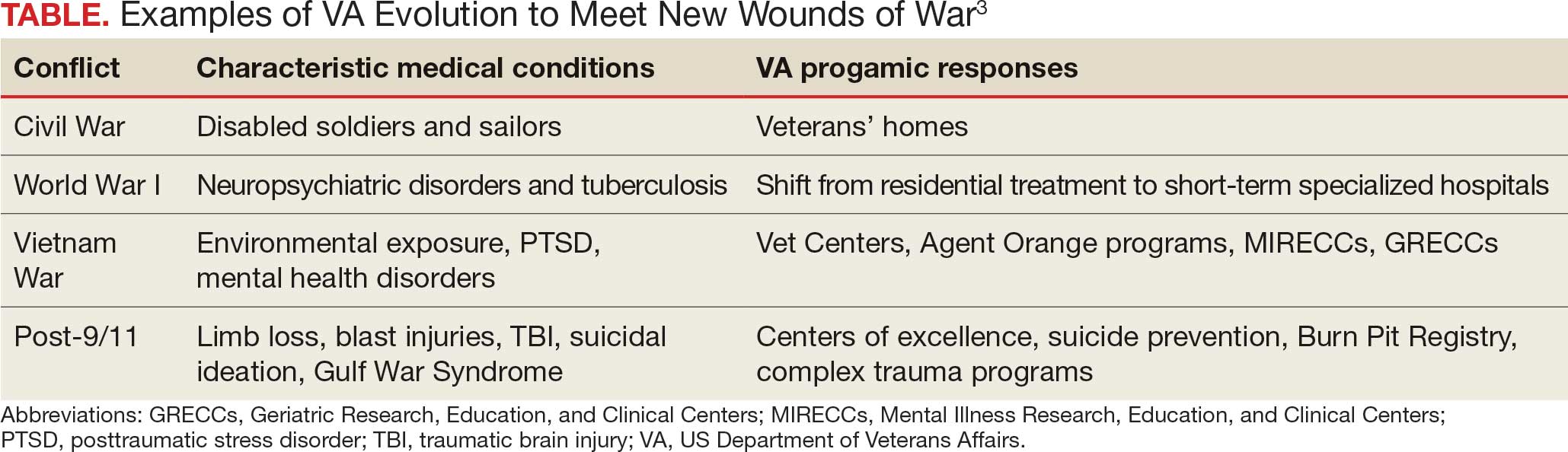

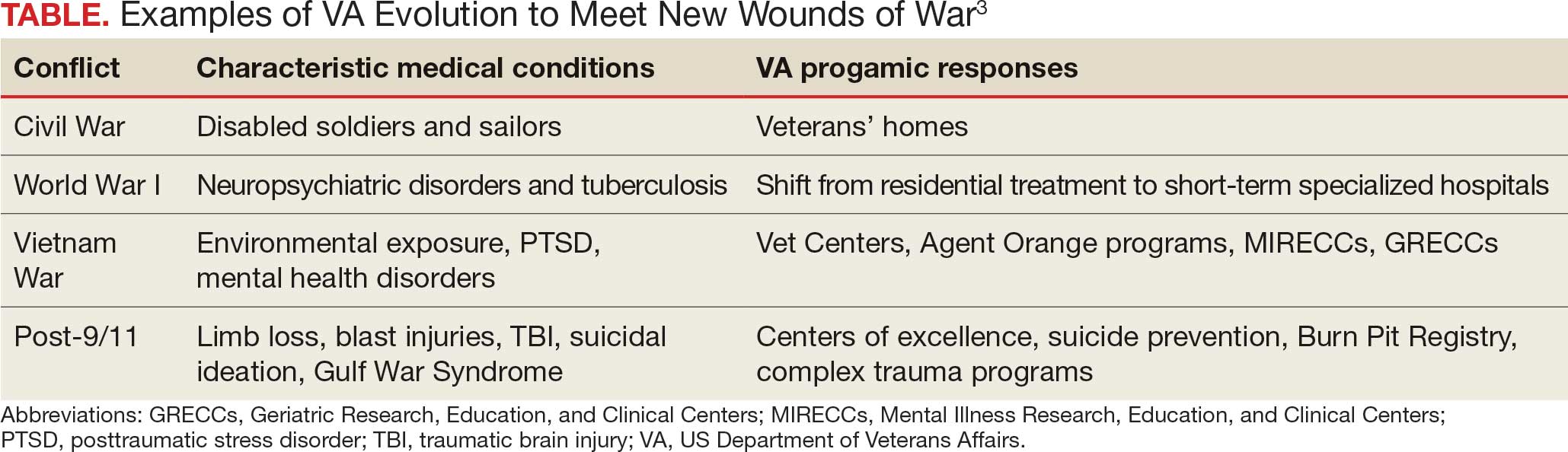

The Table provides a general example of the schema for TBI severity. This was an iterative process in which clinical experts reviewed study-defined measurement definitions to develop general harmonized domains, and NLP techniques facilitated and accelerated identification and organization of measurements within these domains.

Expected Impact

Harmonization combining LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS datasets is ongoing. Preliminary descriptive analyses of baseline cohort data indicate that harmonization across data sources is appropriate, given the lack of significant heterogeneity across sites and studies for most domains. Work by members of the TBD team is expected to lay the foundation for the use of existing and ongoing prospective, longitudinal datasets (eg, LIMBIC-CENC, TRACTS) and linked large datasets (eg, VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure including electronic health records, VA Million Veteran Program, DaVINCI [US Department of Defense and VA Infrastructure for Clinical Intelligence]) to generate generalizable, clinically relevant information to advance precision brain and mental health care among service members and veterans.

By enhancing existing practice, this synthesized dataset has the potential to inform tailored and personalized medicine approaches designed to meet the needs of veterans and service members. These data will serve as the starting point for multivariable models examining the intersection of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors. The goal of this data harmonization effort is to better elucidate how clinicians and researchers can select optimal approaches for veterans and service members with TBI histories by accounting for a comprehensive set of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors in an individually tailored manner. These data may further extend existing clinical practice guideline approaches, inform shared decision-making, and enhance functional outcomes beyond those currently available.

Conclusions

Individuals who have served in the military have unique biopsychosocial exposures that are associated with brain and mental health disorders. To address these needs, the nationwide TBD team has initiated the creation of a unified, longitudinal dataset that includes harmonized measures from existing LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS protocols. Initial data harmonization efforts are required to facilitate precision prognostics, diagnostics, and tailored interventions, with the goal of improving veterans’ brain and mental health and psychosocial functioning and enabling tailored and evidence-informed, individualized clinical care.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Updated January 21, 2025. Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-turning-discovery-into-health/promise-precision-medicine.

- Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, S 785, 116th Cong (2019-2020) Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- Cheng C, Messerschmidt L, Bravo I, et al. A general primer for data harmonization. Sci Data. 2024;11:152. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-02956-3

- Neil M, Cameron D, Clauss K, et al. A proof-of-concept study demonstrating how FITBIR datasets can be harmonized to examine posttraumatic stress disorder-traumatic brain injury associations. J Behav Data Sci. 2024;4:45-62. doi:10.35566/jbds/oneil

- O’Neil ME, Cameron D, Krushnic D, et al. Using harmonized FITBIR datasets to examine associations between TBI history and cognitive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. doi:10.1080/23279095.2024.2401974

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Clauss K, et al. Harmonizing federal interagency traumatic brain injury research data to examine depression and suicide-related outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2024;69:159-170. doi:10.1037/rep0000547

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Walker WC, et al. Increased risk for clinically significant sleep disturbances in mild traumatic brain injury: an approach to leveraging the federal interagency traumatic brain injury research database. Brain Sci. 2024;14:921. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090921

- Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A, et al. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043-1049. doi:10.1002/da.21993

- Hung CI, Weng LJ, Su YJ, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasized. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:700-708. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01585.x

- Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Amuan ME, et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22:661-667. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.019

- Cifu DX. Clinical research findings from the long-term impact of military-relevant brain injury consortium-chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) 2013-2021. Brain Inj. 2022;36:587-597.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033843

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:220-226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx044

- Fortier CB, Amick MM, Kenna A, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) clinical interview and the VA TBI screen. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:E1-7. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000008

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, et al. Verbal memory deficits in OEF/OIF/OND veterans exposed to blasts at close range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24:466-475. doi:10.1017/S1355617717001242

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:813-825. doi:10.1093/brain/aww344

- Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:25-33. doi:10.1002/jts.21979

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, et al. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Radigan LJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime and the VA Comprehensive TBI Evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E55. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000361

- Sydnor VJ, Bouix S, Pasternak O, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury impacts associations between limbic system microstructure and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102190. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102190

- Van Etten EJ, Knight AR, Colaizzi TA, et al. Peritraumatic context and long-term outcomes of concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2455622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55622

- Andrews RJ, Fonda JR, Levin LK, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the predictors of neurobehavioral symptom reporting in veterans. Neurology. 2018;91:e732-e745. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000006034

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudional prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. 2019. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Singhal A. Modern information retrieval: a brief overview. IEEE Data Eng Bull. 2001;24:34-43.

In leveraging existing, readily available evidence-based health care information (eg, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines), clinicians have historically made recommendations based on treatment responses of the average patient.1 Recently, this approach has been expanded into data-driven, evidence-based precision medical care for individuals across a wide range of disciplines and care settings. These precision medicine approaches use information related to an individual’s genes, environment, and lifestyle to tailor recommendations regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Applying precision medicine approaches to the unique exposures and experiences of service members and veterans—particularly those who served in combat environments—through the incorporation of biopsychosocial factors into medical decision-making may be even more pertinent. This sentiment is reflected in Section 305 of the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, which outlines the Precision Medicine Initiative of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify and validate brain and mental health biomarkers.2 Despite widespread consensus regarding the promise of precision medicine, large, rich datasets with elements pertaining to common military exposures such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are limited.

Existing datasets, most of which are relatively small or focus on specific cohorts (eg, older veterans, transitioning veterans), continue to create barriers to advancing precision medicine. For example, in classically designed clinical trials, analyses are generally conducted in a manner that may obfuscate efficacy among subcohorts of individuals, thereby underscoring the need to explore alternative strategies to unify existing datasets capable of revealing such heterogeneity.3 The evidence base for precision medical care is limited, drawing from published trials with relatively small sample sizes and even larger cohort studies have limited biomarker data. Additionally, these models are often exploratory during development, and to avoid statistical overfitting of an exploratory model, validation in similar datasets is needed—an added burden when data sources are small or underpowered to begin with.

A promising approach is to combine and harmonize the largest, most deeply characterized data sources from similar samples. Although combining such datasets may appear to require minimal time and effort, harmonizing similar variables in an evidence-based and replicable manner requires time and expertise, even when participant characteristics and outcomes are similar.4-7

Challenges related to harmonization are related to the wide range of strategies (eg, self-report questionnaires, clinical interviews, electronic health record review) used to measure common brain and mental health constructs, such as depression. Even when similar methods (eg, self-report measures) are implemented, challenges persist. For example, if a study used a depression measure that focused primarily on cognitive symptoms (eg, pessimism, self-dislike, suicidal ideation) and another study used a depression measure composed of items more heavily weighted towards somatic symptoms (eg, insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, decreased libido), combining their data could be challenging, particularly if researchers, clinicians, or administrators are interested in more than dichotomous outcomes (eg, depression vs no depression).8,9

To address this knowledge gap and harmonize multimodal data from varied sources, well-planned and reproducible curation is needed. Longitudinal cohort studies of service members and veterans with military combat and training exposure histories provide researchers and other stakeholders access to extant biopsychosocial data shown to affect risk for adverse health outcomes; however, efforts to facilitate individually tailored treatment or other precision medicine approaches would benefit from the synthesis of such datasets.10

Members of the VA Total Brain Diagnostics (TBD) team are engaged in harmonizing variables from the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC)11 and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS).12-21 While there is overlap across LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS with respect to data domains, considerable data harmonization is needed to allow for future valid and meaningful analyses, particularly those involving multivariable predictors.

Data Sources

Both data sources for the TBD harmonization project, LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS, include extensive, longitudinal data collected from relatively large cohorts of veterans and service members with combat exposure. Both studies collect detailed data related to potential brain injury history and include participants with and without a history of TBI. Similarly, both include extensive collection of fluid biomarkers and imaging data, as well as measures of biopsychosocial functioning.

Data collection sites for LIMBIC-CENC include 16 recruitment sites, 9 at VA medical centers (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego) and 7 at military treatment sites (Alexandria, San Diego, Tampa, Tacoma, Columbia, Coronado, Hinesville), in addition to 11 assessment sites (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego, Alexandria, Augusta). Data for TRACTS are collected at sites in Boston and Houston.

LIMBIC-CENC is a 12-year, 17-site cohort of service members and veteran participants with combat exposure who are well characterized at baseline and undergo annual reassessments. As of December 2025, > 3100 participants have been recruited, and nearly 90% remain in follow-up. Data collection includes > 6200 annual follow-up evaluations and > 1550 5-year re-evaluations, with 400 enrolled participants followed up annually.

TRACTS is a 16-year, 2-site cohort of veterans with combat exposure who complete comprehensive assessments at enrollment, undergo annual reassessments, and complete comprehensive reassessment every 5 years thereafter. As of December 2025, > 1075 participants have completed baseline (Time 1) assessments, > 600 have completed the 2-year re-evaluation (Time 2), > 175 have completed the 5-year re-evaluation (Time 3), and > 35 have completed 10-year evaluations (Time 4), with about 50 new participants added and 100 enrolled participants followed up annually. More data on participant characteristics are available for both LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS in previous publications.11,22These 2 ongoing, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of service members and veterans offer access to a wide range of potential risk factors that can affect response to care and outcomes, including demographics (eg, age, sex), injury characteristics (eg, pre-exposure factors, exposure factors), biomarkers (eg, serum, saliva, brain imaging, evoked potentials), and functional measures (eg, computerized posturography, computerized eye tracking, sensory testing, clinical examination, neuropsychological assessments, symptom questionnaires).

Harmonization Strategy

Pooling and harmonizing data from large studies evaluating similar participant cohorts and conditions involves numerous steps to appropriately handle a variety of measurements and disparate variable names. The TBD team adapted a model data harmonization system developed by O’Neil et al through initial work harmonizing the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System (FITBIR).4-7 This process was expanded and generalized by the research team to combine data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to create a single pooled dataset for analysis (Figure).

Injury Research database.

This approach was selected because it accommodates heterogeneous study designs (eg, cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control), data collection methods (eg, clinical assessment, self-reported, objective blood, and imaging biomarkers), and various assessments of the same construct (ie, different measures of brain injury). While exact matches for data collection methods and measures may be easily harmonized, the timing of assessment, number of assessments, assessment tool version, and other factors must be considered. The goal was to harmonize data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to allow additional data sources to be harmonized and incorporated in the future.

Original data files from each study were reshaped to represent participant-level observations with 1 unique measurement per row. The measurement represents what information was collected and the value recorded represents the unique observation. These data are linked to metadata from the original study, which includes the study’s definition of each measurement, how it was collected, and any available information regarding when it was collected in reference to study enrollment or injury. Additional information on the file source, row, and column position of each data point was added to enable recreation of the original data as needed.

The resulting dataset was used to harmonize measurements from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS into a priori-defined schemas for brain- and mental health-relevant concepts, including TBI severity, PTSD, substance use, depression, suicidal ideation, and functioning (including cognitive, physical, and social functioning). This process was facilitated using natural language processing (NLP). Each study uniquely defines all measurements and provides written definitions with the data. Measurement definitions serve as records describing what was collected, how it was collected, and how the study may have uniquely defined information for its purposes. For example, definitions of exposure to brain injury and severity of brain injury may differ between studies, and the study-provided definition defines these differences.

Definitions were converted into numeric vectors through sentence embedding, a process that preserves the semantic meaning of the definition.23 Cosine similarity was used as the primary metric to compare the semantic textual similarity between pairs of measurement definitions. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no meaningful similarity and 1 indicates they have identical meanings.24 This approach leverages the relationship between the definitions of each measurement provided by a study and enables quick comparison of all pairwise combinations of measurement definitions between studies.

Subsets of similar measurements across studies were organized into a priori-defined schema. Clinical experts then reviewed each schema and further refined them into domains, (eg, mechanism of injury, clinical signs, acute symptoms) and subdomains (children), such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, and alteration of consciousness. This approach allows efficient handling of 2 specific cases that commonly occur when pooling and harmonizing datasets: (1) identifying the same measurement with differing names; and (2) identifying different measurements with definitions that each relate to the same domain.

The Table provides a general example of the schema for TBI severity. This was an iterative process in which clinical experts reviewed study-defined measurement definitions to develop general harmonized domains, and NLP techniques facilitated and accelerated identification and organization of measurements within these domains.

Expected Impact

Harmonization combining LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS datasets is ongoing. Preliminary descriptive analyses of baseline cohort data indicate that harmonization across data sources is appropriate, given the lack of significant heterogeneity across sites and studies for most domains. Work by members of the TBD team is expected to lay the foundation for the use of existing and ongoing prospective, longitudinal datasets (eg, LIMBIC-CENC, TRACTS) and linked large datasets (eg, VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure including electronic health records, VA Million Veteran Program, DaVINCI [US Department of Defense and VA Infrastructure for Clinical Intelligence]) to generate generalizable, clinically relevant information to advance precision brain and mental health care among service members and veterans.

By enhancing existing practice, this synthesized dataset has the potential to inform tailored and personalized medicine approaches designed to meet the needs of veterans and service members. These data will serve as the starting point for multivariable models examining the intersection of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors. The goal of this data harmonization effort is to better elucidate how clinicians and researchers can select optimal approaches for veterans and service members with TBI histories by accounting for a comprehensive set of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors in an individually tailored manner. These data may further extend existing clinical practice guideline approaches, inform shared decision-making, and enhance functional outcomes beyond those currently available.

Conclusions

Individuals who have served in the military have unique biopsychosocial exposures that are associated with brain and mental health disorders. To address these needs, the nationwide TBD team has initiated the creation of a unified, longitudinal dataset that includes harmonized measures from existing LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS protocols. Initial data harmonization efforts are required to facilitate precision prognostics, diagnostics, and tailored interventions, with the goal of improving veterans’ brain and mental health and psychosocial functioning and enabling tailored and evidence-informed, individualized clinical care.

In leveraging existing, readily available evidence-based health care information (eg, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines), clinicians have historically made recommendations based on treatment responses of the average patient.1 Recently, this approach has been expanded into data-driven, evidence-based precision medical care for individuals across a wide range of disciplines and care settings. These precision medicine approaches use information related to an individual’s genes, environment, and lifestyle to tailor recommendations regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Applying precision medicine approaches to the unique exposures and experiences of service members and veterans—particularly those who served in combat environments—through the incorporation of biopsychosocial factors into medical decision-making may be even more pertinent. This sentiment is reflected in Section 305 of the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, which outlines the Precision Medicine Initiative of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify and validate brain and mental health biomarkers.2 Despite widespread consensus regarding the promise of precision medicine, large, rich datasets with elements pertaining to common military exposures such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are limited.

Existing datasets, most of which are relatively small or focus on specific cohorts (eg, older veterans, transitioning veterans), continue to create barriers to advancing precision medicine. For example, in classically designed clinical trials, analyses are generally conducted in a manner that may obfuscate efficacy among subcohorts of individuals, thereby underscoring the need to explore alternative strategies to unify existing datasets capable of revealing such heterogeneity.3 The evidence base for precision medical care is limited, drawing from published trials with relatively small sample sizes and even larger cohort studies have limited biomarker data. Additionally, these models are often exploratory during development, and to avoid statistical overfitting of an exploratory model, validation in similar datasets is needed—an added burden when data sources are small or underpowered to begin with.

A promising approach is to combine and harmonize the largest, most deeply characterized data sources from similar samples. Although combining such datasets may appear to require minimal time and effort, harmonizing similar variables in an evidence-based and replicable manner requires time and expertise, even when participant characteristics and outcomes are similar.4-7

Challenges related to harmonization are related to the wide range of strategies (eg, self-report questionnaires, clinical interviews, electronic health record review) used to measure common brain and mental health constructs, such as depression. Even when similar methods (eg, self-report measures) are implemented, challenges persist. For example, if a study used a depression measure that focused primarily on cognitive symptoms (eg, pessimism, self-dislike, suicidal ideation) and another study used a depression measure composed of items more heavily weighted towards somatic symptoms (eg, insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, decreased libido), combining their data could be challenging, particularly if researchers, clinicians, or administrators are interested in more than dichotomous outcomes (eg, depression vs no depression).8,9

To address this knowledge gap and harmonize multimodal data from varied sources, well-planned and reproducible curation is needed. Longitudinal cohort studies of service members and veterans with military combat and training exposure histories provide researchers and other stakeholders access to extant biopsychosocial data shown to affect risk for adverse health outcomes; however, efforts to facilitate individually tailored treatment or other precision medicine approaches would benefit from the synthesis of such datasets.10

Members of the VA Total Brain Diagnostics (TBD) team are engaged in harmonizing variables from the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC)11 and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS).12-21 While there is overlap across LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS with respect to data domains, considerable data harmonization is needed to allow for future valid and meaningful analyses, particularly those involving multivariable predictors.

Data Sources

Both data sources for the TBD harmonization project, LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS, include extensive, longitudinal data collected from relatively large cohorts of veterans and service members with combat exposure. Both studies collect detailed data related to potential brain injury history and include participants with and without a history of TBI. Similarly, both include extensive collection of fluid biomarkers and imaging data, as well as measures of biopsychosocial functioning.

Data collection sites for LIMBIC-CENC include 16 recruitment sites, 9 at VA medical centers (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego) and 7 at military treatment sites (Alexandria, San Diego, Tampa, Tacoma, Columbia, Coronado, Hinesville), in addition to 11 assessment sites (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego, Alexandria, Augusta). Data for TRACTS are collected at sites in Boston and Houston.

LIMBIC-CENC is a 12-year, 17-site cohort of service members and veteran participants with combat exposure who are well characterized at baseline and undergo annual reassessments. As of December 2025, > 3100 participants have been recruited, and nearly 90% remain in follow-up. Data collection includes > 6200 annual follow-up evaluations and > 1550 5-year re-evaluations, with 400 enrolled participants followed up annually.

TRACTS is a 16-year, 2-site cohort of veterans with combat exposure who complete comprehensive assessments at enrollment, undergo annual reassessments, and complete comprehensive reassessment every 5 years thereafter. As of December 2025, > 1075 participants have completed baseline (Time 1) assessments, > 600 have completed the 2-year re-evaluation (Time 2), > 175 have completed the 5-year re-evaluation (Time 3), and > 35 have completed 10-year evaluations (Time 4), with about 50 new participants added and 100 enrolled participants followed up annually. More data on participant characteristics are available for both LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS in previous publications.11,22These 2 ongoing, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of service members and veterans offer access to a wide range of potential risk factors that can affect response to care and outcomes, including demographics (eg, age, sex), injury characteristics (eg, pre-exposure factors, exposure factors), biomarkers (eg, serum, saliva, brain imaging, evoked potentials), and functional measures (eg, computerized posturography, computerized eye tracking, sensory testing, clinical examination, neuropsychological assessments, symptom questionnaires).

Harmonization Strategy

Pooling and harmonizing data from large studies evaluating similar participant cohorts and conditions involves numerous steps to appropriately handle a variety of measurements and disparate variable names. The TBD team adapted a model data harmonization system developed by O’Neil et al through initial work harmonizing the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System (FITBIR).4-7 This process was expanded and generalized by the research team to combine data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to create a single pooled dataset for analysis (Figure).

Injury Research database.

This approach was selected because it accommodates heterogeneous study designs (eg, cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control), data collection methods (eg, clinical assessment, self-reported, objective blood, and imaging biomarkers), and various assessments of the same construct (ie, different measures of brain injury). While exact matches for data collection methods and measures may be easily harmonized, the timing of assessment, number of assessments, assessment tool version, and other factors must be considered. The goal was to harmonize data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to allow additional data sources to be harmonized and incorporated in the future.

Original data files from each study were reshaped to represent participant-level observations with 1 unique measurement per row. The measurement represents what information was collected and the value recorded represents the unique observation. These data are linked to metadata from the original study, which includes the study’s definition of each measurement, how it was collected, and any available information regarding when it was collected in reference to study enrollment or injury. Additional information on the file source, row, and column position of each data point was added to enable recreation of the original data as needed.

The resulting dataset was used to harmonize measurements from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS into a priori-defined schemas for brain- and mental health-relevant concepts, including TBI severity, PTSD, substance use, depression, suicidal ideation, and functioning (including cognitive, physical, and social functioning). This process was facilitated using natural language processing (NLP). Each study uniquely defines all measurements and provides written definitions with the data. Measurement definitions serve as records describing what was collected, how it was collected, and how the study may have uniquely defined information for its purposes. For example, definitions of exposure to brain injury and severity of brain injury may differ between studies, and the study-provided definition defines these differences.

Definitions were converted into numeric vectors through sentence embedding, a process that preserves the semantic meaning of the definition.23 Cosine similarity was used as the primary metric to compare the semantic textual similarity between pairs of measurement definitions. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no meaningful similarity and 1 indicates they have identical meanings.24 This approach leverages the relationship between the definitions of each measurement provided by a study and enables quick comparison of all pairwise combinations of measurement definitions between studies.

Subsets of similar measurements across studies were organized into a priori-defined schema. Clinical experts then reviewed each schema and further refined them into domains, (eg, mechanism of injury, clinical signs, acute symptoms) and subdomains (children), such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, and alteration of consciousness. This approach allows efficient handling of 2 specific cases that commonly occur when pooling and harmonizing datasets: (1) identifying the same measurement with differing names; and (2) identifying different measurements with definitions that each relate to the same domain.

The Table provides a general example of the schema for TBI severity. This was an iterative process in which clinical experts reviewed study-defined measurement definitions to develop general harmonized domains, and NLP techniques facilitated and accelerated identification and organization of measurements within these domains.

Expected Impact

Harmonization combining LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS datasets is ongoing. Preliminary descriptive analyses of baseline cohort data indicate that harmonization across data sources is appropriate, given the lack of significant heterogeneity across sites and studies for most domains. Work by members of the TBD team is expected to lay the foundation for the use of existing and ongoing prospective, longitudinal datasets (eg, LIMBIC-CENC, TRACTS) and linked large datasets (eg, VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure including electronic health records, VA Million Veteran Program, DaVINCI [US Department of Defense and VA Infrastructure for Clinical Intelligence]) to generate generalizable, clinically relevant information to advance precision brain and mental health care among service members and veterans.

By enhancing existing practice, this synthesized dataset has the potential to inform tailored and personalized medicine approaches designed to meet the needs of veterans and service members. These data will serve as the starting point for multivariable models examining the intersection of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors. The goal of this data harmonization effort is to better elucidate how clinicians and researchers can select optimal approaches for veterans and service members with TBI histories by accounting for a comprehensive set of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors in an individually tailored manner. These data may further extend existing clinical practice guideline approaches, inform shared decision-making, and enhance functional outcomes beyond those currently available.

Conclusions

Individuals who have served in the military have unique biopsychosocial exposures that are associated with brain and mental health disorders. To address these needs, the nationwide TBD team has initiated the creation of a unified, longitudinal dataset that includes harmonized measures from existing LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS protocols. Initial data harmonization efforts are required to facilitate precision prognostics, diagnostics, and tailored interventions, with the goal of improving veterans’ brain and mental health and psychosocial functioning and enabling tailored and evidence-informed, individualized clinical care.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Updated January 21, 2025. Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-turning-discovery-into-health/promise-precision-medicine.

- Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, S 785, 116th Cong (2019-2020) Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- Cheng C, Messerschmidt L, Bravo I, et al. A general primer for data harmonization. Sci Data. 2024;11:152. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-02956-3

- Neil M, Cameron D, Clauss K, et al. A proof-of-concept study demonstrating how FITBIR datasets can be harmonized to examine posttraumatic stress disorder-traumatic brain injury associations. J Behav Data Sci. 2024;4:45-62. doi:10.35566/jbds/oneil

- O’Neil ME, Cameron D, Krushnic D, et al. Using harmonized FITBIR datasets to examine associations between TBI history and cognitive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. doi:10.1080/23279095.2024.2401974

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Clauss K, et al. Harmonizing federal interagency traumatic brain injury research data to examine depression and suicide-related outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2024;69:159-170. doi:10.1037/rep0000547

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Walker WC, et al. Increased risk for clinically significant sleep disturbances in mild traumatic brain injury: an approach to leveraging the federal interagency traumatic brain injury research database. Brain Sci. 2024;14:921. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090921

- Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A, et al. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043-1049. doi:10.1002/da.21993

- Hung CI, Weng LJ, Su YJ, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasized. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:700-708. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01585.x

- Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Amuan ME, et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22:661-667. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.019

- Cifu DX. Clinical research findings from the long-term impact of military-relevant brain injury consortium-chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) 2013-2021. Brain Inj. 2022;36:587-597.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033843

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:220-226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx044

- Fortier CB, Amick MM, Kenna A, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) clinical interview and the VA TBI screen. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:E1-7. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000008

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, et al. Verbal memory deficits in OEF/OIF/OND veterans exposed to blasts at close range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24:466-475. doi:10.1017/S1355617717001242

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:813-825. doi:10.1093/brain/aww344

- Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:25-33. doi:10.1002/jts.21979

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, et al. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Radigan LJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime and the VA Comprehensive TBI Evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E55. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000361

- Sydnor VJ, Bouix S, Pasternak O, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury impacts associations between limbic system microstructure and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102190. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102190

- Van Etten EJ, Knight AR, Colaizzi TA, et al. Peritraumatic context and long-term outcomes of concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2455622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55622

- Andrews RJ, Fonda JR, Levin LK, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the predictors of neurobehavioral symptom reporting in veterans. Neurology. 2018;91:e732-e745. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000006034

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudional prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. 2019. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Singhal A. Modern information retrieval: a brief overview. IEEE Data Eng Bull. 2001;24:34-43.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Updated January 21, 2025. Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-turning-discovery-into-health/promise-precision-medicine.

- Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, S 785, 116th Cong (2019-2020) Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- Cheng C, Messerschmidt L, Bravo I, et al. A general primer for data harmonization. Sci Data. 2024;11:152. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-02956-3

- Neil M, Cameron D, Clauss K, et al. A proof-of-concept study demonstrating how FITBIR datasets can be harmonized to examine posttraumatic stress disorder-traumatic brain injury associations. J Behav Data Sci. 2024;4:45-62. doi:10.35566/jbds/oneil

- O’Neil ME, Cameron D, Krushnic D, et al. Using harmonized FITBIR datasets to examine associations between TBI history and cognitive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. doi:10.1080/23279095.2024.2401974

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Clauss K, et al. Harmonizing federal interagency traumatic brain injury research data to examine depression and suicide-related outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2024;69:159-170. doi:10.1037/rep0000547

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Walker WC, et al. Increased risk for clinically significant sleep disturbances in mild traumatic brain injury: an approach to leveraging the federal interagency traumatic brain injury research database. Brain Sci. 2024;14:921. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090921

- Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A, et al. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043-1049. doi:10.1002/da.21993

- Hung CI, Weng LJ, Su YJ, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasized. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:700-708. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01585.x

- Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Amuan ME, et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22:661-667. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.019

- Cifu DX. Clinical research findings from the long-term impact of military-relevant brain injury consortium-chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) 2013-2021. Brain Inj. 2022;36:587-597.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033843

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:220-226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx044

- Fortier CB, Amick MM, Kenna A, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) clinical interview and the VA TBI screen. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:E1-7. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000008

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, et al. Verbal memory deficits in OEF/OIF/OND veterans exposed to blasts at close range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24:466-475. doi:10.1017/S1355617717001242

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:813-825. doi:10.1093/brain/aww344

- Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:25-33. doi:10.1002/jts.21979

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, et al. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Radigan LJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime and the VA Comprehensive TBI Evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E55. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000361

- Sydnor VJ, Bouix S, Pasternak O, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury impacts associations between limbic system microstructure and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102190. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102190

- Van Etten EJ, Knight AR, Colaizzi TA, et al. Peritraumatic context and long-term outcomes of concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2455622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55622

- Andrews RJ, Fonda JR, Levin LK, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the predictors of neurobehavioral symptom reporting in veterans. Neurology. 2018;91:e732-e745. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000006034

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudional prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. 2019. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Singhal A. Modern information retrieval: a brief overview. IEEE Data Eng Bull. 2001;24:34-43.

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

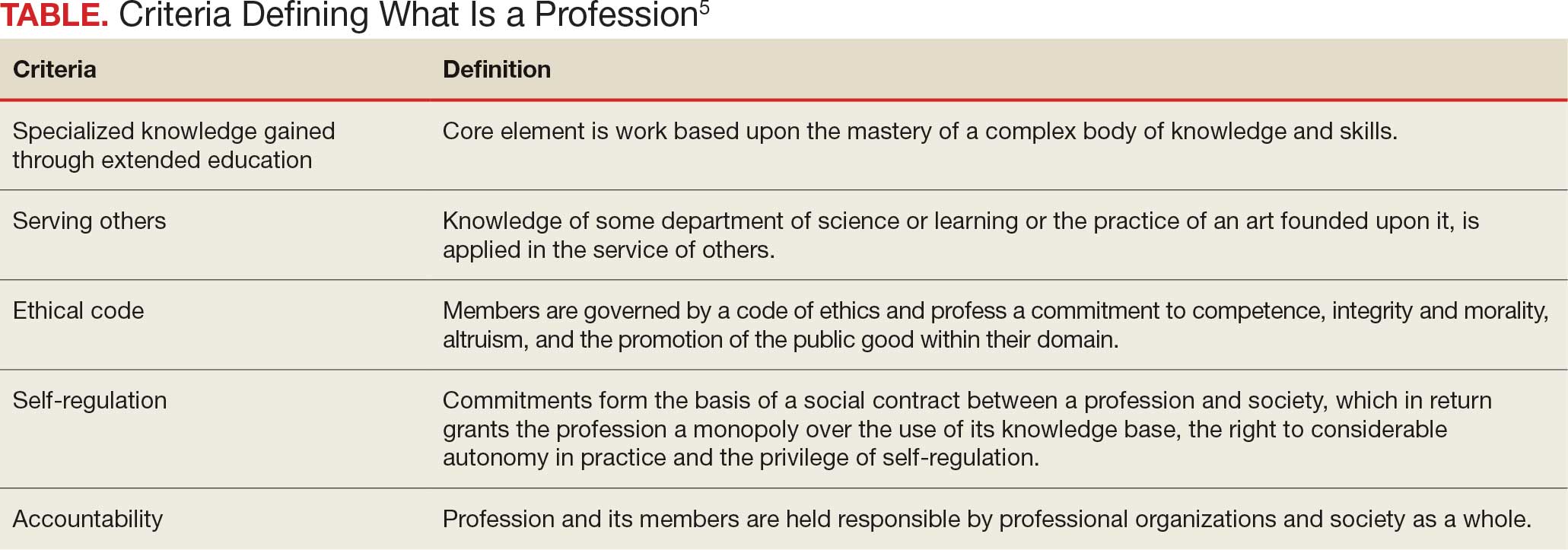

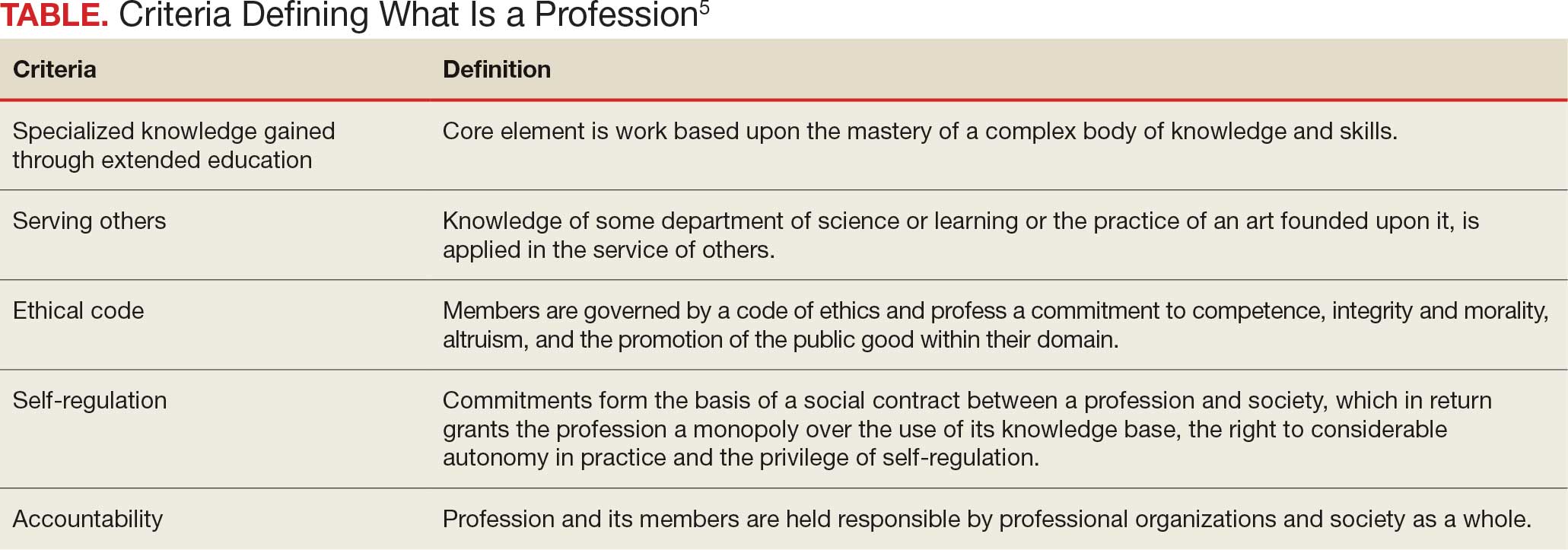

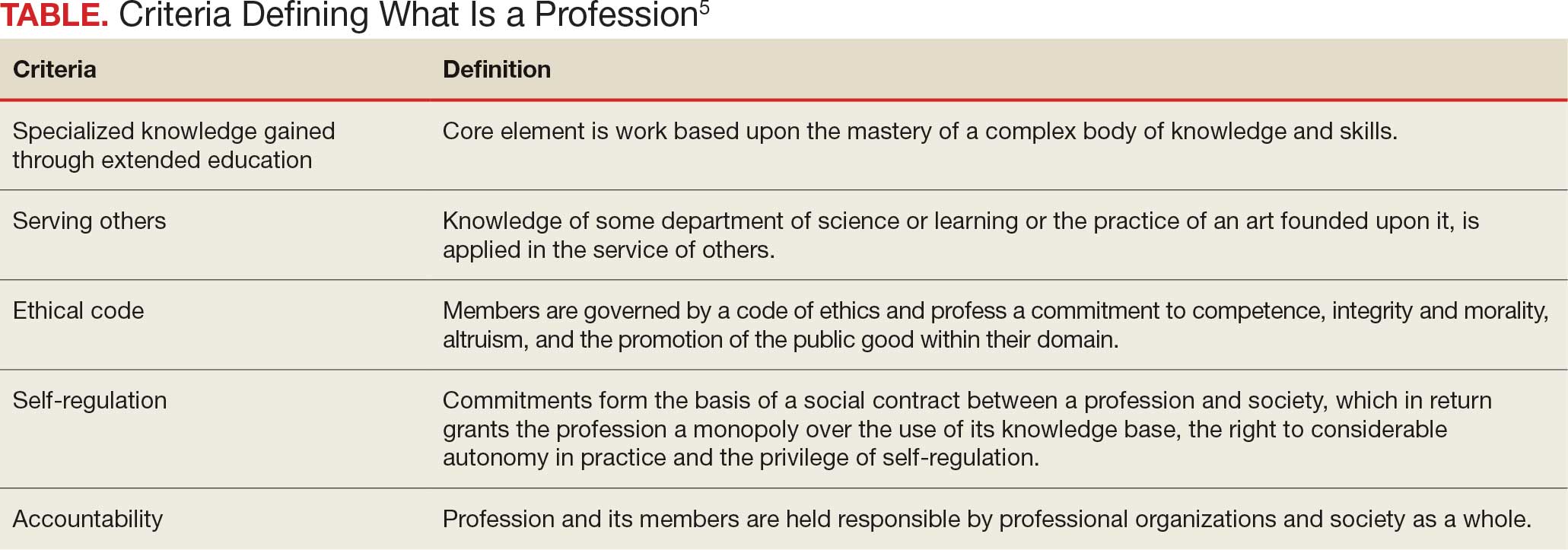

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.

- Wade JW. Public responsibilities of the learned professions. Louisiana Law Rev. 1960;21:130-148

- US Department of Education. Myth vs. fact: the definition of professional degrees. Press Release. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/myth-vs-fact-definition-of-professional-degrees

- Laws J. Full list of degrees not classed as “professional” by Trump admin. Newsweek. Updated November 26, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-degrees-professional-trump-administration-11085695

- New York Academy of Medicine. Response to stripping “professional status” as proposed by the Department of Education. New York Academy of Medicine. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://nyam.org/article/response-to-stripping-professional-status-as-proposed-by-the-department-of-education

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:74-76. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing is a professional degree. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.aacnnursing.org/policy-advocacy/take-action/nursing-is-a-professional-degree

- National Association of Social Workers. Social work is a profession. Social Workers. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.socialworkers.org

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.nccpa.net/about-nccpa/#who-we-are

- The Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.fsbpt.org/About-Us/Staff-Home

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism and medicine’s contract with social contract with society. Virtual Mentor. 2004;6:185-188. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2004.6.4.msoc1-040

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.

- Wade JW. Public responsibilities of the learned professions. Louisiana Law Rev. 1960;21:130-148

- US Department of Education. Myth vs. fact: the definition of professional degrees. Press Release. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/myth-vs-fact-definition-of-professional-degrees

- Laws J. Full list of degrees not classed as “professional” by Trump admin. Newsweek. Updated November 26, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-degrees-professional-trump-administration-11085695

- New York Academy of Medicine. Response to stripping “professional status” as proposed by the Department of Education. New York Academy of Medicine. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://nyam.org/article/response-to-stripping-professional-status-as-proposed-by-the-department-of-education

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:74-76. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing is a professional degree. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.aacnnursing.org/policy-advocacy/take-action/nursing-is-a-professional-degree

- National Association of Social Workers. Social work is a profession. Social Workers. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.socialworkers.org

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.nccpa.net/about-nccpa/#who-we-are

- The Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.fsbpt.org/About-Us/Staff-Home

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism and medicine’s contract with social contract with society. Virtual Mentor. 2004;6:185-188. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2004.6.4.msoc1-040

- Wade JW. Public responsibilities of the learned professions. Louisiana Law Rev. 1960;21:130-148

- US Department of Education. Myth vs. fact: the definition of professional degrees. Press Release. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/myth-vs-fact-definition-of-professional-degrees

- Laws J. Full list of degrees not classed as “professional” by Trump admin. Newsweek. Updated November 26, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-degrees-professional-trump-administration-11085695