User login

Antidepressants for bipolar depression: Tips to stay out of trouble

In clinical practice, 50% to 80% of bipolar patients receive long-term antidepressants,1 although potential benefits probably outweigh risks in 20% to 40%. This gap suggests that psychiatrists could do more to stay out of trouble when prescribing antidepressants for patients with bipolar depression.

Antidepressants have not shown efficacy in long-term treatment, and evidence of their effectiveness in acute bipolar depression is limited. They appear to pose greater risk of switching and mood destabilization for some patients and certain types of bipolar illness, and some antidepressant classes are more worrisome than others.

Because carefully analyzing risks and benefits is essential when considering antidepressants for a patient with bipolar illness, this article clarifies that delicate balance and offers evidence-based recommendations for using antidepressants in bipolar depression.

ACUTE THERAPY

Clinical trials support antidepressants as the treatment of choice for unipolar depression, but less evidence supports efficacy and safety in acute bipolar depression. Depressive episodes predominate in bipolar disorder, with chronic subsyndromal symptoms being most characteristic.2,3 Compared with mania or hypomania, depressive episodes:

- last longer and are more frequent

- contribute to greater morbidity and mortality

- pose a greater treatment challenge.

Antidepressants have shown benefit in multiple double-blind, bipolar depression trials and were as effective as mood stabilizers in one small study.4 Even so, no trials have found them more effective than mood stabilizers in acute bipolar depression.

Controlled trials. Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have examined antidepressant use in bipolar depression.5,6 The larger and better designed—a prospective 10-week study by Nemeroff et al6—examined 117 outpatients with type I bipolar disorder.

Subjects who had been taking lithium (serum levels 0.5 to 1.2 mEq/L) for ≥6 weeks and were experiencing moderate breakthrough depression then received paroxetine (mean dosage 32.6 mg/d), imipramine (mean dosage 166.7 mg/d), or placebo. Therapeutic response was defined as ≤7 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) or ≤2 on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale—normally considered criteria for depressive remission.

The authors hoped to show a statistically significant medication-placebo difference, but the antidepressants’ effects were similar to those of placebo. Thus, adding antidepressants to lithium conferred no added benefit, though the small sample size may have created a false negative.

Interestingly, a post-hoc analysis found different treatment outcomes when patients were separated into two groups by lithium serum levels:

- low therapeutic (≤0.8 mEq/L)

- high therapeutic (>0.8 mEq/L).

Adding antidepressants significantly reduced HRSD scores compared with placebo in the low lithium group but not in the high lithium group. Thus, therapeutic lithium levels may have moderate antidepressant effects, and adding antidepressants may help patients who cannot tolerate therapeutic lithium levels.

MAINTENANCE THERAPY

Antidepressants may have modest efficacy in acute bipolar depression, but they have not shown benefit—with or without mood stabilizers—in 7 studies of bipolar depression maintenance therapy. Most were double-blind, long-term trials comparing tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) with lithium or adding TCAs to lithium; 3 were placebo-controlled.7 Antidepressants were not more effective than mood stabilizers such as lithium or lamotrigine in preventing bipolar depression.

Type II patients. For depression in type II bipolar disorder, the only data on using antidepressants as acute or maintenance therapy come from post-hoc analyses of unipolar depression trials and retrospective assessments of “manic switches.” No specific mania rating scales have been used.8,9

Long-term antidepressants. Two naturalistic studies by Altshuler et al10,11 explored continuing antidepressants as bipolar depression maintenance treatment. The larger trial11 included 84 patients (most with type I bipolar disorder) who experienced breakthrough depression while taking a mood stabilizer. This subset (15%) of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network had tolerated antidepressants at least 2 months without switching into hypomania/mania and remained in remission at least 6 weeks. None were rapid cyclers.

With counseling from clinicians, patients chose to continue or discontinue taking antidepressants. Relapse rates after 1 year were 70% in patients who stopped antidepressants after <6 months, compared with 24% in those who continued taking them for 1 year. The authors concluded that bipolar patients may benefit from staying on antidepressants at least 6 months and perhaps 12 or more months after depressive remission.

Keep in mind, however, that these findings may not apply to all bipolar patients. This study pertains to a minority of robust responders—none of whom were rapid cyclers—who tolerated the medication well and were not randomly assigned to continue or discontinue antidepressants. Other evidence suggests that depressed bipolar patients are three times more likely than unipolar patients (54% vs 16%) to develop tolerance to antidepressants.12

ANTIDEPRESSANT RISKS

Risks of using antidepressants in bipolar patients include acute switches into hypo/mania, usually within 8 weeks of starting an antidepressant, and new-onset mood destabilization—with cycle acceleration or rapid cycling—or worsening of pre-existing rapid cycling (Table 1).1

Table 1

Switches vs destabilization: Defining antidepressant risks

| Risk | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acute switches to hypomania/mania | ≤8 weeks by convention, unless dosage is increased |

| Mood destabilization | |

| Cycle acceleration | Increase of ≥2 mood episodes while taking antidepressants, compared with a similar exposure time before treatment |

| Rapid cycling | ≥4mood episodes in previous 12 months (new-onset or exacerbation of baseline pattern), according to DSM-IV-TR |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

Switching risk. Some researchers have reported antidepressant-induced switches to be milder and more brief than spontaneous hypo/manias,13 whereas others have observed more-severe mixed14 and even psychotic episodes. Risk factors that may predispose patients to switching include:

- personal or family history of switches or mood destabilization

- family history of bipolar disorder

- exposure to multiple antidepressant trials

- history of substance abuse or dependence

- early onset (age <25) and/or treatment of mood symptoms.15,16

True switch rates are difficult to estimate because clinical trials have used different switching definitions, durations, antidepressants (with or without mood stabilizers, and with different mood stabilizers), and cohorts (often excluding rapid cyclers). Except for the Nemeroff et al study,6 no prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have examined switch rates, and even this study was not large enough to detect statistically significant differences.

Thus we must rely on naturalistic evidence that is less rigorous but more applicable to clinical practice. This literature reveals switch rates of:

- 30% to 60% with TCAs and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- 15% to 27% with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), bupropion, and venlafaxine.

Average switch rates are thought to be approximately 40% with TCAs/MAOIs and 20% with the newer antidepressants.1 Preliminary data associate venlafaxine with higher switch rates than SSRIs or bupropion, so perhaps antidepressants with some noradrenergic effects (including TCAs) facilitate the switching phenomenon.17

Mood destabilization. Three randomized, controlled trials suggest that antidepressants—especially TCAs—increase the risk of cycle acceleration or rapid cycling in bipolar patients. The best designed study—sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health—was a 10-year, prospective, double-blind trial of 51 rapid-cycling patients. The trial’s on-off-on design showed that 20% of these patients developed rapid cycling as a direct result of taking TCAs.18

Unfortunately, most randomized, controlled trials are not designed to show a relationship between antidepressants and mood destabilization. Observational literature is mixed but suggests that antidepressant use is associated with rapid cycling. Most evidence supports a relationship between antidepressants and long-term mood destabilization—especially cycle acceleration, which is believed to occur in approximately 20% of patients using TCAs or SSRIs.1

Are mood stabilizers protective? Some studies suggest that mood stabilizers may help protect against switches. Most of the evidence—using lithium and TCAs—suggests a 50% drop in switch rates when patients receive mood stabilizers with antidepressants. In one study, lithium was more protective than anticonvulsants for SSRI-induced mania, but the difference was not statistically significant.19

Because study data variability, we don’t know if some mood stabilizers are more effective than others in preventing antidepressant-related switching. This variability is likely caused by:

- medication-specific factors (such as higher switch rates with TCAs and possibly dual-reuptake inhibitors than with SSRIs)

- illness-specific factors (such as rapid cycling and cycle pattern)

- patient-specific factors, already described. Mood stabilizers appear to be more protective against switching than against mood destabilization, in which their effects are less clear (Table 2).15

Table 2

Frequency of switching or mood destabilization with antidepressants

| Bipolar risk | Causative agents | Frequency | Mood stabilizer effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute switch | TCAs, MAOIs | ~ 40% | Variably protective; apparent partial risk reduction ~ 50% |

| SSRIs, bupropion, venlafaxine | ~ 20% | ||

| Mood destabilization | TCAs, SSRIs | ~ 20% | Not as clearly protective against mood destabilization as against acute switching |

| TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants; MAOIs: monoamine oxidase inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |||

| Source: References 1, 15 | |||

TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS

How does a clinician decide which bipolar depressed patients should receive antidepressants?

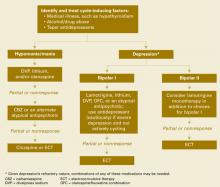

The first step in treating bipolar depression (Algorithm) is to provide optimal dosages of the patient’s mood stabilizers. Consensus guidelines20 suggest lithium or lamotrigine as first-line treatments for bipolar depression. Evidence also shows efficacy for atypical antipsychotics, including the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC)—FDA-approved for acute bipolar depression21—and quetiapine monotherapy.22 Dosages vary, but suggested ranges include:

- lithium: 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L; aim for approximately 0.8 mEq/L, but some data suggest 0.6 to 0.7 mEq/L may be sufficient

- lamotrigine: 50 to 250 mg/d (the higher dosage is based on maintenance studies)

- OFC: 6 to 12 mg olanzapine/25 to 50 mg fluoxetine

- quetiapine: 300 to 600 mg/d.

The next step is an antidepressant risk/benefit analysis, weighing the considerable risks of switching/mood destabilization with the patient’s depressive illness severity, type of bipolar disorder (such as rapid cycling), and cycle pattern.

Algorithm Recommended treatment of bipolar depression

Cycle patterns. In a naturalistic study, Macqueen et al23 used life chart data for 42 bipolar patients to assess how the mood state preceding a prospectively observed depressive episode affected treatment response:

- A euthymic mood state in the previous 2 months represented a uniphasic pattern and an isolated depressive episode.

- A preceding hypomanic/manic mood state indicated a biphasic pattern.

Approximately 60% of bipolar patients show a biphasic pattern, although the episode sequence is usually depression-hypomania/mania rather than hypomania/mania-depression. These authors included patients whose breakthrough depressive episodes were treated with an antidepressant or a putative mood stabilizer but not an atypical antipsychotic.

In patients treated with an antidepressant, the response-to-switch ratio was 10:1 for those previously euthymic, compared with a less beneficial 0.75:1 in previously hypomanic/manic patients. This small study suggests that a patient’s cycle pattern may help you decide whether to use an antidepressant for bipolar depression.

How to use antidepressants. As described, some depressed bipolar patients are better candidates for antidepressant therapy than others (Table 3).

Table 3

Antidepressants for bipolar depression? Consider ‘ideal patient’ traits

| Severe depression refractory to optimal doses of ≥1 mood stabilizers |

| Uniphasic cycle pattern |

| Not rapid cycling |

| No history of switching or mood destabilization |

| No comorbid substance abuse |

Use antidepressants cautiously and conservatively in a minority of bipolar patients (approximately 20% to 40%) and usually for short periods (discussed below). SSRIs or bupropion are first-line agents because:

- they appear to be relatively less likely to cause switching than other antidepressant classes

- controlled trials have examined these antidepressants in bipolar depression.

Depressed patients with very mild, nonrapid-cycling, bipolar II disorder and no more than three previous hypomanic episodes might be candidates for antidepressant monotherapy. In other bipolar patients, always use at least one mood stabilizer if you decide to use an antidepressant.

TREATMENT DURATION

No randomized, controlled trial has examined what duration of antidepressant treatment may be optimum for bipolar depression, but consensus guidelines recommend:

- approximately 3 to 7 months, depending on depression severity

- approximately one-half that duration (2 to 4 months) for rapid-cycling bipolar disorder.20

Because of the switching risk, one could also argue for a shorter treatment duration in patients with a biphasic cycle pattern—especially with an episode sequence of depression to hypomania/mania to euthymia.

Ideally, patients would stay on antidepressants no longer than the natural course of their depression (usually 2 to 6 months in bipolar depression), although it could be shorter in rapid cyclers. Approximately 15% to 20% of patients may have a robust initial response to antidepressants and need to be maintained on these medications, especially after several tapers and relapses have failed.

Related resources

- Bipolar Clinic and Research Program. Massachusetts General Hospital. Includes tools for clinicians and the clinical site for the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). www.manicdepressive.org.

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Olanzapine/fluoxetine • Symbyax

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Altman is a speaker for Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Abbott Laboratories.

1. Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Soldani F, et al. Antidepressants in bipolar disorder: the case for caution. Bipolar Disorders 2003;5:421-33.

2. Judd LL. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:530-7.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(3):261-9.

4. Young LT, Joffe RT, Robb JC, et al. Double-blind comparison of addition of a second mood stabilizer versus an antidepressant to an initial mood stabilizer for treatment of patients with bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:124-6.

5. Cohn JB, Collins G, Ashbrook E, et al. A comparison of fluoxetine, imipramine and placebo in patients with bipolar depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1989;4(4):313-22.

6. Nemeroff CB, Evans DL, Gyulai L, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine and paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(6):906-12.

7. Ghaemi SN, Lenox MS, Baldessarini RJ. Effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(7):565-9.

8. Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F, Fawcett J, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in treating bipolar II major depressive episode. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;18:435-40.

9. Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F. Venlafaxine monotherapy in women with bipolar II and unipolar major depression. J Affect Disord 2000;59:225-9.

10. Altshuler L, Kiriakos L, Calcagno J, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation versus antidepressant continuation at 1-year risk for relapse of bipolar depression: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:612-16.

11. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1252-62.

12. Ghaemi SN, Rosenquist KJ, Ko JY, et al. Antidepressant treatment in bipolar versus unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:163-5.

13. Stoll AL, Mayer PV, Kolbrener M, et al. Antidepressant-associated mania: a controlled comparison with spontaneous mania. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1642-5.

14. Zubieta JK, Demitrack MA. Possible bupropion precipitation of mania and mixed affective state. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991;11(5):327-8.

15. Goldberg JF, Truman CJ. Antidepressant-induced mania: an overview of current controversies. Bipolar Disorders 2003;5:407-20.

16. Goldberg JF, Whiteside JE. The association between substance abuse and antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:791-5.

17. Post RM, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, et al. A re-evaluation of the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression: data from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. Bipolar Disorders 2003;5:396-406.

18. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, et al. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:179-84.

19. Henry C, Sorbara F, Lacoste J, et al. Antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar patients: identification of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:249-55.

20. Keck PE, Jr, Perlis RH, Otto MW, et al. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Treatment of bipolar disorder 2004. Postgrad Med 2004;1-120.

21. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:1079-88.

22. Calabrese JR. Quetiapine BOLDER study [presentation]. New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2004.

23. MacQueen GM, Young LT, Marriott M, et al. Previous mood state predicts response and switch rates in patients with bipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002;105:414-18.

In clinical practice, 50% to 80% of bipolar patients receive long-term antidepressants,1 although potential benefits probably outweigh risks in 20% to 40%. This gap suggests that psychiatrists could do more to stay out of trouble when prescribing antidepressants for patients with bipolar depression.

Antidepressants have not shown efficacy in long-term treatment, and evidence of their effectiveness in acute bipolar depression is limited. They appear to pose greater risk of switching and mood destabilization for some patients and certain types of bipolar illness, and some antidepressant classes are more worrisome than others.

Because carefully analyzing risks and benefits is essential when considering antidepressants for a patient with bipolar illness, this article clarifies that delicate balance and offers evidence-based recommendations for using antidepressants in bipolar depression.

ACUTE THERAPY

Clinical trials support antidepressants as the treatment of choice for unipolar depression, but less evidence supports efficacy and safety in acute bipolar depression. Depressive episodes predominate in bipolar disorder, with chronic subsyndromal symptoms being most characteristic.2,3 Compared with mania or hypomania, depressive episodes:

- last longer and are more frequent

- contribute to greater morbidity and mortality

- pose a greater treatment challenge.

Antidepressants have shown benefit in multiple double-blind, bipolar depression trials and were as effective as mood stabilizers in one small study.4 Even so, no trials have found them more effective than mood stabilizers in acute bipolar depression.

Controlled trials. Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have examined antidepressant use in bipolar depression.5,6 The larger and better designed—a prospective 10-week study by Nemeroff et al6—examined 117 outpatients with type I bipolar disorder.

Subjects who had been taking lithium (serum levels 0.5 to 1.2 mEq/L) for ≥6 weeks and were experiencing moderate breakthrough depression then received paroxetine (mean dosage 32.6 mg/d), imipramine (mean dosage 166.7 mg/d), or placebo. Therapeutic response was defined as ≤7 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) or ≤2 on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale—normally considered criteria for depressive remission.

The authors hoped to show a statistically significant medication-placebo difference, but the antidepressants’ effects were similar to those of placebo. Thus, adding antidepressants to lithium conferred no added benefit, though the small sample size may have created a false negative.

Interestingly, a post-hoc analysis found different treatment outcomes when patients were separated into two groups by lithium serum levels:

- low therapeutic (≤0.8 mEq/L)

- high therapeutic (>0.8 mEq/L).

Adding antidepressants significantly reduced HRSD scores compared with placebo in the low lithium group but not in the high lithium group. Thus, therapeutic lithium levels may have moderate antidepressant effects, and adding antidepressants may help patients who cannot tolerate therapeutic lithium levels.

MAINTENANCE THERAPY

Antidepressants may have modest efficacy in acute bipolar depression, but they have not shown benefit—with or without mood stabilizers—in 7 studies of bipolar depression maintenance therapy. Most were double-blind, long-term trials comparing tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) with lithium or adding TCAs to lithium; 3 were placebo-controlled.7 Antidepressants were not more effective than mood stabilizers such as lithium or lamotrigine in preventing bipolar depression.

Type II patients. For depression in type II bipolar disorder, the only data on using antidepressants as acute or maintenance therapy come from post-hoc analyses of unipolar depression trials and retrospective assessments of “manic switches.” No specific mania rating scales have been used.8,9

Long-term antidepressants. Two naturalistic studies by Altshuler et al10,11 explored continuing antidepressants as bipolar depression maintenance treatment. The larger trial11 included 84 patients (most with type I bipolar disorder) who experienced breakthrough depression while taking a mood stabilizer. This subset (15%) of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network had tolerated antidepressants at least 2 months without switching into hypomania/mania and remained in remission at least 6 weeks. None were rapid cyclers.

With counseling from clinicians, patients chose to continue or discontinue taking antidepressants. Relapse rates after 1 year were 70% in patients who stopped antidepressants after <6 months, compared with 24% in those who continued taking them for 1 year. The authors concluded that bipolar patients may benefit from staying on antidepressants at least 6 months and perhaps 12 or more months after depressive remission.

Keep in mind, however, that these findings may not apply to all bipolar patients. This study pertains to a minority of robust responders—none of whom were rapid cyclers—who tolerated the medication well and were not randomly assigned to continue or discontinue antidepressants. Other evidence suggests that depressed bipolar patients are three times more likely than unipolar patients (54% vs 16%) to develop tolerance to antidepressants.12

ANTIDEPRESSANT RISKS

Risks of using antidepressants in bipolar patients include acute switches into hypo/mania, usually within 8 weeks of starting an antidepressant, and new-onset mood destabilization—with cycle acceleration or rapid cycling—or worsening of pre-existing rapid cycling (Table 1).1

Table 1

Switches vs destabilization: Defining antidepressant risks

| Risk | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acute switches to hypomania/mania | ≤8 weeks by convention, unless dosage is increased |

| Mood destabilization | |

| Cycle acceleration | Increase of ≥2 mood episodes while taking antidepressants, compared with a similar exposure time before treatment |

| Rapid cycling | ≥4mood episodes in previous 12 months (new-onset or exacerbation of baseline pattern), according to DSM-IV-TR |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

Switching risk. Some researchers have reported antidepressant-induced switches to be milder and more brief than spontaneous hypo/manias,13 whereas others have observed more-severe mixed14 and even psychotic episodes. Risk factors that may predispose patients to switching include:

- personal or family history of switches or mood destabilization

- family history of bipolar disorder

- exposure to multiple antidepressant trials

- history of substance abuse or dependence

- early onset (age <25) and/or treatment of mood symptoms.15,16

True switch rates are difficult to estimate because clinical trials have used different switching definitions, durations, antidepressants (with or without mood stabilizers, and with different mood stabilizers), and cohorts (often excluding rapid cyclers). Except for the Nemeroff et al study,6 no prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have examined switch rates, and even this study was not large enough to detect statistically significant differences.

Thus we must rely on naturalistic evidence that is less rigorous but more applicable to clinical practice. This literature reveals switch rates of:

- 30% to 60% with TCAs and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- 15% to 27% with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), bupropion, and venlafaxine.

Average switch rates are thought to be approximately 40% with TCAs/MAOIs and 20% with the newer antidepressants.1 Preliminary data associate venlafaxine with higher switch rates than SSRIs or bupropion, so perhaps antidepressants with some noradrenergic effects (including TCAs) facilitate the switching phenomenon.17

Mood destabilization. Three randomized, controlled trials suggest that antidepressants—especially TCAs—increase the risk of cycle acceleration or rapid cycling in bipolar patients. The best designed study—sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health—was a 10-year, prospective, double-blind trial of 51 rapid-cycling patients. The trial’s on-off-on design showed that 20% of these patients developed rapid cycling as a direct result of taking TCAs.18

Unfortunately, most randomized, controlled trials are not designed to show a relationship between antidepressants and mood destabilization. Observational literature is mixed but suggests that antidepressant use is associated with rapid cycling. Most evidence supports a relationship between antidepressants and long-term mood destabilization—especially cycle acceleration, which is believed to occur in approximately 20% of patients using TCAs or SSRIs.1

Are mood stabilizers protective? Some studies suggest that mood stabilizers may help protect against switches. Most of the evidence—using lithium and TCAs—suggests a 50% drop in switch rates when patients receive mood stabilizers with antidepressants. In one study, lithium was more protective than anticonvulsants for SSRI-induced mania, but the difference was not statistically significant.19

Because study data variability, we don’t know if some mood stabilizers are more effective than others in preventing antidepressant-related switching. This variability is likely caused by:

- medication-specific factors (such as higher switch rates with TCAs and possibly dual-reuptake inhibitors than with SSRIs)

- illness-specific factors (such as rapid cycling and cycle pattern)

- patient-specific factors, already described. Mood stabilizers appear to be more protective against switching than against mood destabilization, in which their effects are less clear (Table 2).15

Table 2

Frequency of switching or mood destabilization with antidepressants

| Bipolar risk | Causative agents | Frequency | Mood stabilizer effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute switch | TCAs, MAOIs | ~ 40% | Variably protective; apparent partial risk reduction ~ 50% |

| SSRIs, bupropion, venlafaxine | ~ 20% | ||

| Mood destabilization | TCAs, SSRIs | ~ 20% | Not as clearly protective against mood destabilization as against acute switching |

| TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants; MAOIs: monoamine oxidase inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |||

| Source: References 1, 15 | |||

TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS

How does a clinician decide which bipolar depressed patients should receive antidepressants?

The first step in treating bipolar depression (Algorithm) is to provide optimal dosages of the patient’s mood stabilizers. Consensus guidelines20 suggest lithium or lamotrigine as first-line treatments for bipolar depression. Evidence also shows efficacy for atypical antipsychotics, including the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC)—FDA-approved for acute bipolar depression21—and quetiapine monotherapy.22 Dosages vary, but suggested ranges include:

- lithium: 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L; aim for approximately 0.8 mEq/L, but some data suggest 0.6 to 0.7 mEq/L may be sufficient

- lamotrigine: 50 to 250 mg/d (the higher dosage is based on maintenance studies)

- OFC: 6 to 12 mg olanzapine/25 to 50 mg fluoxetine

- quetiapine: 300 to 600 mg/d.

The next step is an antidepressant risk/benefit analysis, weighing the considerable risks of switching/mood destabilization with the patient’s depressive illness severity, type of bipolar disorder (such as rapid cycling), and cycle pattern.

Algorithm Recommended treatment of bipolar depression

Cycle patterns. In a naturalistic study, Macqueen et al23 used life chart data for 42 bipolar patients to assess how the mood state preceding a prospectively observed depressive episode affected treatment response:

- A euthymic mood state in the previous 2 months represented a uniphasic pattern and an isolated depressive episode.

- A preceding hypomanic/manic mood state indicated a biphasic pattern.

Approximately 60% of bipolar patients show a biphasic pattern, although the episode sequence is usually depression-hypomania/mania rather than hypomania/mania-depression. These authors included patients whose breakthrough depressive episodes were treated with an antidepressant or a putative mood stabilizer but not an atypical antipsychotic.

In patients treated with an antidepressant, the response-to-switch ratio was 10:1 for those previously euthymic, compared with a less beneficial 0.75:1 in previously hypomanic/manic patients. This small study suggests that a patient’s cycle pattern may help you decide whether to use an antidepressant for bipolar depression.

How to use antidepressants. As described, some depressed bipolar patients are better candidates for antidepressant therapy than others (Table 3).

Table 3

Antidepressants for bipolar depression? Consider ‘ideal patient’ traits

| Severe depression refractory to optimal doses of ≥1 mood stabilizers |

| Uniphasic cycle pattern |

| Not rapid cycling |

| No history of switching or mood destabilization |

| No comorbid substance abuse |

Use antidepressants cautiously and conservatively in a minority of bipolar patients (approximately 20% to 40%) and usually for short periods (discussed below). SSRIs or bupropion are first-line agents because:

- they appear to be relatively less likely to cause switching than other antidepressant classes

- controlled trials have examined these antidepressants in bipolar depression.

Depressed patients with very mild, nonrapid-cycling, bipolar II disorder and no more than three previous hypomanic episodes might be candidates for antidepressant monotherapy. In other bipolar patients, always use at least one mood stabilizer if you decide to use an antidepressant.

TREATMENT DURATION

No randomized, controlled trial has examined what duration of antidepressant treatment may be optimum for bipolar depression, but consensus guidelines recommend:

- approximately 3 to 7 months, depending on depression severity

- approximately one-half that duration (2 to 4 months) for rapid-cycling bipolar disorder.20

Because of the switching risk, one could also argue for a shorter treatment duration in patients with a biphasic cycle pattern—especially with an episode sequence of depression to hypomania/mania to euthymia.

Ideally, patients would stay on antidepressants no longer than the natural course of their depression (usually 2 to 6 months in bipolar depression), although it could be shorter in rapid cyclers. Approximately 15% to 20% of patients may have a robust initial response to antidepressants and need to be maintained on these medications, especially after several tapers and relapses have failed.

Related resources

- Bipolar Clinic and Research Program. Massachusetts General Hospital. Includes tools for clinicians and the clinical site for the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). www.manicdepressive.org.

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Olanzapine/fluoxetine • Symbyax

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Altman is a speaker for Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Abbott Laboratories.

In clinical practice, 50% to 80% of bipolar patients receive long-term antidepressants,1 although potential benefits probably outweigh risks in 20% to 40%. This gap suggests that psychiatrists could do more to stay out of trouble when prescribing antidepressants for patients with bipolar depression.

Antidepressants have not shown efficacy in long-term treatment, and evidence of their effectiveness in acute bipolar depression is limited. They appear to pose greater risk of switching and mood destabilization for some patients and certain types of bipolar illness, and some antidepressant classes are more worrisome than others.

Because carefully analyzing risks and benefits is essential when considering antidepressants for a patient with bipolar illness, this article clarifies that delicate balance and offers evidence-based recommendations for using antidepressants in bipolar depression.

ACUTE THERAPY

Clinical trials support antidepressants as the treatment of choice for unipolar depression, but less evidence supports efficacy and safety in acute bipolar depression. Depressive episodes predominate in bipolar disorder, with chronic subsyndromal symptoms being most characteristic.2,3 Compared with mania or hypomania, depressive episodes:

- last longer and are more frequent

- contribute to greater morbidity and mortality

- pose a greater treatment challenge.

Antidepressants have shown benefit in multiple double-blind, bipolar depression trials and were as effective as mood stabilizers in one small study.4 Even so, no trials have found them more effective than mood stabilizers in acute bipolar depression.

Controlled trials. Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have examined antidepressant use in bipolar depression.5,6 The larger and better designed—a prospective 10-week study by Nemeroff et al6—examined 117 outpatients with type I bipolar disorder.

Subjects who had been taking lithium (serum levels 0.5 to 1.2 mEq/L) for ≥6 weeks and were experiencing moderate breakthrough depression then received paroxetine (mean dosage 32.6 mg/d), imipramine (mean dosage 166.7 mg/d), or placebo. Therapeutic response was defined as ≤7 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) or ≤2 on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale—normally considered criteria for depressive remission.

The authors hoped to show a statistically significant medication-placebo difference, but the antidepressants’ effects were similar to those of placebo. Thus, adding antidepressants to lithium conferred no added benefit, though the small sample size may have created a false negative.

Interestingly, a post-hoc analysis found different treatment outcomes when patients were separated into two groups by lithium serum levels:

- low therapeutic (≤0.8 mEq/L)

- high therapeutic (>0.8 mEq/L).

Adding antidepressants significantly reduced HRSD scores compared with placebo in the low lithium group but not in the high lithium group. Thus, therapeutic lithium levels may have moderate antidepressant effects, and adding antidepressants may help patients who cannot tolerate therapeutic lithium levels.

MAINTENANCE THERAPY

Antidepressants may have modest efficacy in acute bipolar depression, but they have not shown benefit—with or without mood stabilizers—in 7 studies of bipolar depression maintenance therapy. Most were double-blind, long-term trials comparing tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) with lithium or adding TCAs to lithium; 3 were placebo-controlled.7 Antidepressants were not more effective than mood stabilizers such as lithium or lamotrigine in preventing bipolar depression.

Type II patients. For depression in type II bipolar disorder, the only data on using antidepressants as acute or maintenance therapy come from post-hoc analyses of unipolar depression trials and retrospective assessments of “manic switches.” No specific mania rating scales have been used.8,9

Long-term antidepressants. Two naturalistic studies by Altshuler et al10,11 explored continuing antidepressants as bipolar depression maintenance treatment. The larger trial11 included 84 patients (most with type I bipolar disorder) who experienced breakthrough depression while taking a mood stabilizer. This subset (15%) of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network had tolerated antidepressants at least 2 months without switching into hypomania/mania and remained in remission at least 6 weeks. None were rapid cyclers.

With counseling from clinicians, patients chose to continue or discontinue taking antidepressants. Relapse rates after 1 year were 70% in patients who stopped antidepressants after <6 months, compared with 24% in those who continued taking them for 1 year. The authors concluded that bipolar patients may benefit from staying on antidepressants at least 6 months and perhaps 12 or more months after depressive remission.

Keep in mind, however, that these findings may not apply to all bipolar patients. This study pertains to a minority of robust responders—none of whom were rapid cyclers—who tolerated the medication well and were not randomly assigned to continue or discontinue antidepressants. Other evidence suggests that depressed bipolar patients are three times more likely than unipolar patients (54% vs 16%) to develop tolerance to antidepressants.12

ANTIDEPRESSANT RISKS

Risks of using antidepressants in bipolar patients include acute switches into hypo/mania, usually within 8 weeks of starting an antidepressant, and new-onset mood destabilization—with cycle acceleration or rapid cycling—or worsening of pre-existing rapid cycling (Table 1).1

Table 1

Switches vs destabilization: Defining antidepressant risks

| Risk | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acute switches to hypomania/mania | ≤8 weeks by convention, unless dosage is increased |

| Mood destabilization | |

| Cycle acceleration | Increase of ≥2 mood episodes while taking antidepressants, compared with a similar exposure time before treatment |

| Rapid cycling | ≥4mood episodes in previous 12 months (new-onset or exacerbation of baseline pattern), according to DSM-IV-TR |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

Switching risk. Some researchers have reported antidepressant-induced switches to be milder and more brief than spontaneous hypo/manias,13 whereas others have observed more-severe mixed14 and even psychotic episodes. Risk factors that may predispose patients to switching include:

- personal or family history of switches or mood destabilization

- family history of bipolar disorder

- exposure to multiple antidepressant trials

- history of substance abuse or dependence

- early onset (age <25) and/or treatment of mood symptoms.15,16

True switch rates are difficult to estimate because clinical trials have used different switching definitions, durations, antidepressants (with or without mood stabilizers, and with different mood stabilizers), and cohorts (often excluding rapid cyclers). Except for the Nemeroff et al study,6 no prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have examined switch rates, and even this study was not large enough to detect statistically significant differences.

Thus we must rely on naturalistic evidence that is less rigorous but more applicable to clinical practice. This literature reveals switch rates of:

- 30% to 60% with TCAs and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- 15% to 27% with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), bupropion, and venlafaxine.

Average switch rates are thought to be approximately 40% with TCAs/MAOIs and 20% with the newer antidepressants.1 Preliminary data associate venlafaxine with higher switch rates than SSRIs or bupropion, so perhaps antidepressants with some noradrenergic effects (including TCAs) facilitate the switching phenomenon.17

Mood destabilization. Three randomized, controlled trials suggest that antidepressants—especially TCAs—increase the risk of cycle acceleration or rapid cycling in bipolar patients. The best designed study—sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health—was a 10-year, prospective, double-blind trial of 51 rapid-cycling patients. The trial’s on-off-on design showed that 20% of these patients developed rapid cycling as a direct result of taking TCAs.18

Unfortunately, most randomized, controlled trials are not designed to show a relationship between antidepressants and mood destabilization. Observational literature is mixed but suggests that antidepressant use is associated with rapid cycling. Most evidence supports a relationship between antidepressants and long-term mood destabilization—especially cycle acceleration, which is believed to occur in approximately 20% of patients using TCAs or SSRIs.1

Are mood stabilizers protective? Some studies suggest that mood stabilizers may help protect against switches. Most of the evidence—using lithium and TCAs—suggests a 50% drop in switch rates when patients receive mood stabilizers with antidepressants. In one study, lithium was more protective than anticonvulsants for SSRI-induced mania, but the difference was not statistically significant.19

Because study data variability, we don’t know if some mood stabilizers are more effective than others in preventing antidepressant-related switching. This variability is likely caused by:

- medication-specific factors (such as higher switch rates with TCAs and possibly dual-reuptake inhibitors than with SSRIs)

- illness-specific factors (such as rapid cycling and cycle pattern)

- patient-specific factors, already described. Mood stabilizers appear to be more protective against switching than against mood destabilization, in which their effects are less clear (Table 2).15

Table 2

Frequency of switching or mood destabilization with antidepressants

| Bipolar risk | Causative agents | Frequency | Mood stabilizer effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute switch | TCAs, MAOIs | ~ 40% | Variably protective; apparent partial risk reduction ~ 50% |

| SSRIs, bupropion, venlafaxine | ~ 20% | ||

| Mood destabilization | TCAs, SSRIs | ~ 20% | Not as clearly protective against mood destabilization as against acute switching |

| TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants; MAOIs: monoamine oxidase inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |||

| Source: References 1, 15 | |||

TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS

How does a clinician decide which bipolar depressed patients should receive antidepressants?

The first step in treating bipolar depression (Algorithm) is to provide optimal dosages of the patient’s mood stabilizers. Consensus guidelines20 suggest lithium or lamotrigine as first-line treatments for bipolar depression. Evidence also shows efficacy for atypical antipsychotics, including the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC)—FDA-approved for acute bipolar depression21—and quetiapine monotherapy.22 Dosages vary, but suggested ranges include:

- lithium: 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L; aim for approximately 0.8 mEq/L, but some data suggest 0.6 to 0.7 mEq/L may be sufficient

- lamotrigine: 50 to 250 mg/d (the higher dosage is based on maintenance studies)

- OFC: 6 to 12 mg olanzapine/25 to 50 mg fluoxetine

- quetiapine: 300 to 600 mg/d.

The next step is an antidepressant risk/benefit analysis, weighing the considerable risks of switching/mood destabilization with the patient’s depressive illness severity, type of bipolar disorder (such as rapid cycling), and cycle pattern.

Algorithm Recommended treatment of bipolar depression

Cycle patterns. In a naturalistic study, Macqueen et al23 used life chart data for 42 bipolar patients to assess how the mood state preceding a prospectively observed depressive episode affected treatment response:

- A euthymic mood state in the previous 2 months represented a uniphasic pattern and an isolated depressive episode.

- A preceding hypomanic/manic mood state indicated a biphasic pattern.

Approximately 60% of bipolar patients show a biphasic pattern, although the episode sequence is usually depression-hypomania/mania rather than hypomania/mania-depression. These authors included patients whose breakthrough depressive episodes were treated with an antidepressant or a putative mood stabilizer but not an atypical antipsychotic.

In patients treated with an antidepressant, the response-to-switch ratio was 10:1 for those previously euthymic, compared with a less beneficial 0.75:1 in previously hypomanic/manic patients. This small study suggests that a patient’s cycle pattern may help you decide whether to use an antidepressant for bipolar depression.

How to use antidepressants. As described, some depressed bipolar patients are better candidates for antidepressant therapy than others (Table 3).

Table 3

Antidepressants for bipolar depression? Consider ‘ideal patient’ traits

| Severe depression refractory to optimal doses of ≥1 mood stabilizers |

| Uniphasic cycle pattern |

| Not rapid cycling |

| No history of switching or mood destabilization |

| No comorbid substance abuse |

Use antidepressants cautiously and conservatively in a minority of bipolar patients (approximately 20% to 40%) and usually for short periods (discussed below). SSRIs or bupropion are first-line agents because:

- they appear to be relatively less likely to cause switching than other antidepressant classes

- controlled trials have examined these antidepressants in bipolar depression.

Depressed patients with very mild, nonrapid-cycling, bipolar II disorder and no more than three previous hypomanic episodes might be candidates for antidepressant monotherapy. In other bipolar patients, always use at least one mood stabilizer if you decide to use an antidepressant.

TREATMENT DURATION

No randomized, controlled trial has examined what duration of antidepressant treatment may be optimum for bipolar depression, but consensus guidelines recommend:

- approximately 3 to 7 months, depending on depression severity

- approximately one-half that duration (2 to 4 months) for rapid-cycling bipolar disorder.20

Because of the switching risk, one could also argue for a shorter treatment duration in patients with a biphasic cycle pattern—especially with an episode sequence of depression to hypomania/mania to euthymia.

Ideally, patients would stay on antidepressants no longer than the natural course of their depression (usually 2 to 6 months in bipolar depression), although it could be shorter in rapid cyclers. Approximately 15% to 20% of patients may have a robust initial response to antidepressants and need to be maintained on these medications, especially after several tapers and relapses have failed.

Related resources

- Bipolar Clinic and Research Program. Massachusetts General Hospital. Includes tools for clinicians and the clinical site for the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). www.manicdepressive.org.

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Olanzapine/fluoxetine • Symbyax

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Altman is a speaker for Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Abbott Laboratories.

1. Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Soldani F, et al. Antidepressants in bipolar disorder: the case for caution. Bipolar Disorders 2003;5:421-33.

2. Judd LL. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:530-7.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(3):261-9.

4. Young LT, Joffe RT, Robb JC, et al. Double-blind comparison of addition of a second mood stabilizer versus an antidepressant to an initial mood stabilizer for treatment of patients with bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:124-6.

5. Cohn JB, Collins G, Ashbrook E, et al. A comparison of fluoxetine, imipramine and placebo in patients with bipolar depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1989;4(4):313-22.

6. Nemeroff CB, Evans DL, Gyulai L, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine and paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(6):906-12.

7. Ghaemi SN, Lenox MS, Baldessarini RJ. Effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(7):565-9.

8. Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F, Fawcett J, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in treating bipolar II major depressive episode. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;18:435-40.

9. Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F. Venlafaxine monotherapy in women with bipolar II and unipolar major depression. J Affect Disord 2000;59:225-9.

10. Altshuler L, Kiriakos L, Calcagno J, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation versus antidepressant continuation at 1-year risk for relapse of bipolar depression: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:612-16.

11. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1252-62.

12. Ghaemi SN, Rosenquist KJ, Ko JY, et al. Antidepressant treatment in bipolar versus unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:163-5.

13. Stoll AL, Mayer PV, Kolbrener M, et al. Antidepressant-associated mania: a controlled comparison with spontaneous mania. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1642-5.

14. Zubieta JK, Demitrack MA. Possible bupropion precipitation of mania and mixed affective state. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991;11(5):327-8.

15. Goldberg JF, Truman CJ. Antidepressant-induced mania: an overview of current controversies. Bipolar Disorders 2003;5:407-20.

16. Goldberg JF, Whiteside JE. The association between substance abuse and antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:791-5.

17. Post RM, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, et al. A re-evaluation of the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression: data from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. Bipolar Disorders 2003;5:396-406.

18. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, et al. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:179-84.

19. Henry C, Sorbara F, Lacoste J, et al. Antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar patients: identification of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:249-55.

20. Keck PE, Jr, Perlis RH, Otto MW, et al. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Treatment of bipolar disorder 2004. Postgrad Med 2004;1-120.

21. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:1079-88.

22. Calabrese JR. Quetiapine BOLDER study [presentation]. New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2004.

23. MacQueen GM, Young LT, Marriott M, et al. Previous mood state predicts response and switch rates in patients with bipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002;105:414-18.

1. Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Soldani F, et al. Antidepressants in bipolar disorder: the case for caution. Bipolar Disorders 2003;5:421-33.

2. Judd LL. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:530-7.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(3):261-9.

4. Young LT, Joffe RT, Robb JC, et al. Double-blind comparison of addition of a second mood stabilizer versus an antidepressant to an initial mood stabilizer for treatment of patients with bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:124-6.

5. Cohn JB, Collins G, Ashbrook E, et al. A comparison of fluoxetine, imipramine and placebo in patients with bipolar depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1989;4(4):313-22.

6. Nemeroff CB, Evans DL, Gyulai L, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine and paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(6):906-12.

7. Ghaemi SN, Lenox MS, Baldessarini RJ. Effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(7):565-9.

8. Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F, Fawcett J, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in treating bipolar II major depressive episode. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;18:435-40.

9. Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F. Venlafaxine monotherapy in women with bipolar II and unipolar major depression. J Affect Disord 2000;59:225-9.

10. Altshuler L, Kiriakos L, Calcagno J, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation versus antidepressant continuation at 1-year risk for relapse of bipolar depression: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:612-16.

11. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1252-62.

12. Ghaemi SN, Rosenquist KJ, Ko JY, et al. Antidepressant treatment in bipolar versus unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:163-5.

13. Stoll AL, Mayer PV, Kolbrener M, et al. Antidepressant-associated mania: a controlled comparison with spontaneous mania. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1642-5.

14. Zubieta JK, Demitrack MA. Possible bupropion precipitation of mania and mixed affective state. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991;11(5):327-8.

15. Goldberg JF, Truman CJ. Antidepressant-induced mania: an overview of current controversies. Bipolar Disorders 2003;5:407-20.

16. Goldberg JF, Whiteside JE. The association between substance abuse and antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:791-5.

17. Post RM, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, et al. A re-evaluation of the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression: data from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. Bipolar Disorders 2003;5:396-406.

18. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, et al. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:179-84.

19. Henry C, Sorbara F, Lacoste J, et al. Antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar patients: identification of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:249-55.

20. Keck PE, Jr, Perlis RH, Otto MW, et al. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Treatment of bipolar disorder 2004. Postgrad Med 2004;1-120.

21. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:1079-88.

22. Calabrese JR. Quetiapine BOLDER study [presentation]. New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2004.

23. MacQueen GM, Young LT, Marriott M, et al. Previous mood state predicts response and switch rates in patients with bipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002;105:414-18.

Bipolar moving target: Draw a bead on rapid cycling with type-specific therapies

Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder is a moving target, with treatment-resistant depression recurring frequently and alternating with hypomanic/manic episodes (Box).1,2 Can one medication adequately treat these complicated patients, or is combination therapy necessary? If more than one medication is needed, are some combinations more effective than others?

This article attempts to answer these questions by:

- discussing recent treatment trial results

- suggesting an algorithm for managing hypomanic/manic and depressive episodes in rapid-cycling patients with bipolar disorder types I or II.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Rapid cycling is associated most consistently with female gender and bipolar II disorder2 (Table); why these two groups are primarily affected is unknown. Results of studies linking rapid cycling with hypothyroidism, gonadal steroid effects, family history, and substance use have been inconsistent and contradictory.2

Age of onset. Recent studies examining bipolar disorder’s age of onset have contradicted earlier rapid-cycling literature. In two large studies, Schneck et al3 and Coryell et al4 found rapid cycling associated with early onset of bipolar illness. The authors note that high rates of rapid cycling in children and adolescents resemble adult rapid cycling and speculate that early-onset bipolar illness might lead to rapid cycling vulnerability.5

Rapid cycling—defined in DSM-IV-TR as four or more depressive, manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes in the previous 12 months—is considered a longitudinal course specifier for bipolar I or II disorder.1 Episodes must be demarcated by:

- full or partial remission lasting at least 2 months

- or a switch to a mood state of opposite polarity.

Cycling variations include ultra-rapid (1 day to 1 week), ultra-ultra rapid or ultradian (<24 hours), and continuous (no euthymic periods between mood episodes). Rapid cycling occurs in an estimated 15% to 25% of patients with bipolar disorder,2 though psychiatrists in specialty and tertiary referral centers see higher percentages because of the illness’ refractory nature.

Transient vs persistent state. Rapid cycling is thought to be either a transient state in long-term bipolar illness or a more chronic expression of the illness. Several studies6,7 have described rapid cycling as a transient phenomenon, whereas others8-11 have found a more persistent rapid cycling course during follow-up. Interestingly, a recent study11 suggested the mood-cycle pattern may be the most important predictor of rapid cycling. Patients with a depression–hypomania/mania-euthymia course demonstrated more-persistent rapid cycling than did those with a hypomania/mania-depression-euthymia course.

Antidepressants. Antidepressants’ role in initiating or exacerbating rapid cycling also remains unclear. Wehr et al8 found that discontinuing antidepressants contributed to cycling cessation or slowing. However, two prospective studies by Coryell et al4 that controlled for major depression found no association between antidepressant use and rapid cycling.

More recently, Yildiz and Sachs12 found a possible gender-specific relationship between antidepressants and rapid cycling. Women exposed to antidepressants before their first hypomanic/manic episode were more likely to develop rapid cycling than women who were not so exposed. This association was not evident in men.

NO DEFINITIVE CHOICES

Any discussion of treating rapid-cycling bipolar disorder is based on limited data, as few prospective studies of this exclusive cohort exist. Many studies report on mixed cohorts of refractory bipolar patients that include rapid cyclers, but separate analyses of rapid-cycling subgroups are not usually reported. Notable exceptions are recent studies by Calabrese et al, which are discussed below.

Lithium. Dunner and Fieve13 were the first to suggest that rapid-cycling bipolar patients respond poorly to lithium maintenance monotherapy. Later studies, however, suggested that lithium could benefit rapid cyclers, primarily in reducing hypomanic or manic episodes.

Baldessarini et al10 found that lithium was less effective for rapid than nonrapid cyclers only in reducing recurrence of depressive episodes. Kukopulos et al14 reported that lithium response in rapid cyclers increased from 16% to 78% after antidepressants were stopped, suggesting that a positive response to lithium may require more limited antidepressant use (or patients not having been exposed to antidepressants at all).

Thus, lithium prophylaxis has at least partial efficacy in many rapid cyclers, especially when antidepressants are avoided.

Divalproex. As with lithium, divalproex sodium appears more effective in treating and preventing hypomanic/manic episodes than depressive episodes in bipolar patients with rapid-cycling illness. Six open studies showed that patients who had not responded to lithium tended to do better with divalproex.15

Calabrese et al then tested the hypothesis that rapid cycling predicts nonresponse to lithium and positive response to divalproex.16 In a randomized controlled trial, they enrolled 254 recently hypomanic/manic rapid-cycling outpatients in an open-label stabilization phase involving combination lithium and divalproex therapy. Stabilized patients were then randomized to monotherapy with lithium, serum level ≥ 0.8 mEq/L, or divalproex, serum level ≥ 50 mcg/mL. Only 60 patients (24%) met stability criteria for randomization, achieving a persistent bimodal response as measured by continuous weeks of:

- Hamilton depression scale (24-item) score ≤ 20

- Young Mania Rating Scale score ≤ 12.5

- Global Assessment Scale score ≥ 51.

Most nonresponse was attributed to refractory depression.

After 20 months of maintenance therapy, about one-half of patients relapsed on either monotherapy. In the survival analysis, the median time to any mood episode was 45 weeks with divalproex monotherapy and 18 weeks with lithium monotherapy, although this difference was not statistically significant. The small sample size and high dropout rate may have created a false-negative error in this study.

Thus, these data did not show divalproex monotherapy to be more effective than lithium monotherapy in managing rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. The combination proved more effective in treating mania than depression and superior to monotherapy. This finding underscores combination therapy’s importance and the need to use mood stabilizers that also treat the depressed phase of bipolar disorder in rapid cyclers.

Table

Clinical characteristics of rapid cycling

| Prevalence approximately 15% to 25% in patients with bipolar disorder |

| More common in women than men |

| More common with type II than type I bipolar disorder |

| Primarily a depressive disease |

| Low treatment response rates and high recurrence risk |

| Associated with antidepressant use in some cases |

Carbamazepine. Recent data refute earlier reports suggesting that rapid cycling predicted positive response to carbamazepine. Multiple open studies and four controlled studies suggest that carbamazepine—like lithium and divalproex—possesses moderate to marked efficacy in the hypomanic/manic phase but poor to moderate efficacy in the depressed phase of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder.17

Lamotrigine. Lamotrigine is the first mood-stabilizing agent that has shown efficacy in maintenance treatment of bipolar depression and rapid cycling. In a double-blind, prospective, placebo-controlled trial, Calabrese et al18 enrolled 324 rapid-cycling patients with bipolar disorder type I or II in an open-label stabilization phase with lamotrigine. The 182 stabilized patients were then randomly assigned to receive either lamotrigine (mean 288 +/- 94 mg/d) or placebo.

For 6 months, 41% of patients receiving lamotrigine and 26% of those receiving placebo remained stable without relapse (P = 0.03), although the difference was statistically significant only for the bipolar II subtype. Lamotrigine appeared most effective in patients with the biphasic pattern of depression-hypomania/mania-euthymia.

Topiramate. Most studies of topiramate in rapid cycling have been retrospective and/or small add-on studies to existing mood stabilizers, with topiramate use associated with moderately or markedly improved manic symptoms.19 Evidence supports further controlled investigations, particularly because topiramate’s weight-loss effects may help overweight or obese patients.

Gabapentin. Gabapentin’s efficacy in rapid cycling has not been established. Although open-label studies showed a 67% response rate when gabapentin was used as adjunctive therapy, two double-blind, placebocontrolled studies of bipolar patients failed to show efficacy.20,21

Atypical antipsychotics. Five atypical antipsychotics—aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone—are FDA-approved for treating acute mania. Olanzapine is also indicated for bipolar maintenance treatment and has the most data showing efficacy in rapid cycling:

- In a 3-week, placebo-controlled study of 139 patients with bipolar I acute mania, olanzapine (median modal 15 mg/d) reduced manic symptoms to a statistically significantly extent in the 45 rapid cyclers.22

- A long-term prospective study followed 23 patients—30% of whom were rapid cyclers—who used olanzapine (mean 8.2 mg/d) as an adjunct to mood stabilizers. Manic and depressive symptoms were reduced significantly in the cohort, which was followed for a mean of 303 days.23

- An 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study24 compared olanzapine monotherapy with the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC) in 833 depressed bipolar I patients, of whom 315 (37%) had rapid cycling. Mean olanzapine dosage was 9.7 mg in monotherapy and 7.4 mg in combination therapy; mean fluoxetine dosage was 39.3 mg.

A follow-up analysis25 showed that rapid cyclers’ depressive symptoms improved rapidly, and this improvement was sustained with OFC but not olanzapine monotherapy. Nonrapid-cycling patients responded to both treatments.

Other atypicals have shown partial efficacy in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder, although the studies have had methodologic limitations. Suppes et al26 conducted the first controlled trial using clozapine as add-on therapy in a 1-year, randomized evaluation of 38 patients with treatment-refractory bipolar disorder. The 21 rapid cyclers received a mean peak of 234 mg/d. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and Clinical Global Improvement scores improved significantly overall, but data specific to the rapid-cycling patients were not reported.

Small, open-label studies using risperidone and quetiapine as adjuncts to mood stabilizers have shown modest efficacy in rapid cycling, usually in treating manic symptoms. A recent 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in bipolar depression showed promising results, though its efficacy in rapid cycling was not reported.27

RECOMMENDED TREATMENT

Because coincidental cycling may give the false appearance of efficacy in the short term, we recommend that you treat rapid cyclers methodically and judge outcomes over several months or cycle-lengths. A general approach includes:

- identify and treat underlying medical illnesses, such as hypothyroidism

- identify and treat comorbid alcohol/drug abuse

- taper or discontinue cycle-inducing agents such as antidepressants or sympathomimetics

- use standard mood stabilizers and/or atypical antipsychotics alone or in combination (Algorithm).

Algorithm Managing manic and depressive phases of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder

Treating acute mania in rapid-cycling patients is similar to managing this phase in nonrapid cyclers. First-tier therapy includes established mood stabilizers such as lithium, divalproex, or atypical antipsychotics. Carbamazepine is usually considered second-tier because of its effects on other medications via cytochrome P-450 system induction, and limited data exist on oxcarbazepine’s efficacy. Lamotrigine has not been proven effective in acute mania. If monotherapy is ineffective, try combinations of mood stabilizers and/or atypical antipsychotics.

Treating the depressed phase in rapid cyclers is far more difficult than treating acute mania and may depend on bipolar subtype:

- Bipolar I patients likely will require one or more mood stabilizers (such as lithium, divalproex, olanzapine) plus add-on lamotrigine.

- Bipolar II patients may benefit from lamotrigine alone.

- Atypical antipsychotics that have putative antidepressant effects without apparent cycle-accelerating effects may also be considered. At this time, olanzapine has the most data.

Given depression’s refractory nature in rapid-cycling bipolar illness, you may need to combine any of the above medications, try electroconvulsive therapy, or use more-experimental strategies such as:

- omega-3 fatty acids

- donepezil

- pramipexole

- high-dose levothyroxine/T4.

Antidepressants. Before using antidepressants to treat bipolar depression, consider carefully the risk of initiating or exacerbating rapid cycling. No definitive evidence is available to guide your decision.

Likewise, the optimal duration of antidepressant treatment is unclear, although tapering the antidepressant as tolerated may be prudent after depressive symptoms are in remission.

Psychosocial interventions. Finally, don’t overlook psychosocial interventions. Bipolar-specific psychotherapies can enhance compliance, lessen depression, and improve treatment response.28

CONCLUSION

Standard mood stabilizers appear to show partial efficacy in rapid cycling’s hypomanic/manic phase but only modest efficacy in the depressed phase. Lamotrigine appears more-promising in treating depressive than acute manic episodes and may be particularly effective for bipolar II patients. Evidence is growing that atypical antipsychotics also have partial efficacy in treating rapid cyclers, though whether this effect is phase-specific is unclear. As no single agent provides ideal bimodal treatment, combination therapy is recommended.

Related resources

- Bipolar Clinic and Research Program. Massachusetts General Hospital. Includes tools for clinicians and the clinical site for the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). www.manicdepressive.org. Accessed Oct. 14, 2004.

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Marneros A, Goodwin FK (eds). Bipolar disorders: Mixed states, rapid cycling and atypical bipolar disorder. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (in press).

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, others

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid, others

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Olanzapine/fluoxetine • Symbyax

- Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Altman is a speaker for Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Abbott Laboratories.

Dr. Schneck is a consultant to AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, UCB Pharma, and Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. and a speaker for AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed, text rev). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

2. Kupka RW, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM, et al. Rapid and non-rapid cycling bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(12):1483-94.

3. Schneck CD, Miklowitz DJ, Calabrese JR, et al. Phenomenology of rapid cycling bipolar disorder: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(10):1902-8.

4. Coryell W, Solomon D, Turvey C, et al. The long-term course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(9):914-20.

5. Findling RL, Gracious BL, McNamara NK, et al. Rapid, continuous cycling and psychiatric comorbidity in pediatric bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord 2001;3:202-10.

6. Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller M. Rapidly cycling affective disorder. Demographics, diagnosis, family history, and course. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:126-31.

7. Maj M, Magliano L, Pirozzi R, et al. Validity of rapid cycling as a course specifier for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1015-19.

8. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, Cowdry RW. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:179-84.

9. Bauer MS, Calabrese J, Dunner DL, et al. Multisite data reanalysis of the validity of rapid cycling as a course modifier for bipolar disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:506-15.

10. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Floris G, Hennen J. Effects of rapid cycling on response to lithium maintenance treatment in 360 bipolar I and II disorder patients. J Affect Disord 2000;61:13-22.

11. Koukopoulos A, Sani G, Koukopoulos AE, et al. Duration and stability of the rapid-cycling course: a long-term personal follow-up of 109 patients. J Affect Disord 2003;73:75-85.

12. Yildiz A, Sachs GS. Do antidepressants induce rapid cycling? A gender-specific association. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:814-18.

13. Dunner DL, Fieve RR. Clinical factors in lithium carbonate prophylaxis failure. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974;30:229-33.

14. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D, Laddomada P, et al. Course of the manic-depressive cycle and changes caused by treatments. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol 1980;13:156-67.

15. Calabrese JR, Woyshville MJ, Kimmel SE, Rapport DJ. Predictors of valproate response in bipolar rapid cycling. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993;13:280-3.

16. Calabrese JR, Shelton M, Rapport DJ, et al. A double-blind 20 month maintenance study of lithium vs. divalproex in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder [presentation]. Pittsburgh, PA: Fifth International Conference on Bipolar Disorder, June 12-14, 2003.

17. Calabrese JR, Bowden C, Woyshville MJ. Lithium and anticonvulsants in the treatment of bipolar disorders. In: Bloom E, Kupfer D (eds). Psychopharmacology: The third generation of progress. New York: Raven Press, 1995;1099-1112.

18. Calabrese JR, Suppes T, Bowden CL, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61(11):841-50.

19. Marcotte D. Use of topiramate, a new anti-epileptic as a mood stabilizer. J Affect Disord 1998;50(2-3):245-51.

20. Pande AC, Crockatt JG, Janney CA, et al. Gabapentin in bipolar disorder: a placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy. Gabapentin Bipolar Disorder Study Group. Bipolar Disord 2000;2(3 pt 2):249-55.

21. Frye MA, Ketter TA, Kimbrell TA, et al. A placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20(6):607-14.

22. Sanger TM, Tohen M, Vieta E, et al. Olanzapine in the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder with a history of rapid cycling. J Affect Disord 2003;73:155-61.

23. Calabrese JR, Kasper S, Johnson G, et al. International consensus group on bipolar I depression treatment guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:569-79.

24. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:1079-88.