User login

Treating cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome

Incidence may increase as marijuana use rises

Case

WS is a 54-year-old African American male with a medical history of diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and gastroparesis. He has multiple admissions for intractable nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain believed to be from diabetic gastroparesis despite a normal gastric-emptying study. Endoscopy done in prior admission showed duodenitis, gastritis, and esophagitis, and colonoscopy revealed diverticulosis. He had a negative gastric-emptying study of 6% retention at 4 hrs. His last hemoglobin A1c was 5 and his glucose has been well controlled. He is hospitalized again for intractable abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. His examination was unremarkable except for dry mucosa and epigastric tenderness. His labs were also insignificant except for prerenal azotemia. Upon further questioning he admitted to significant marijuana use, and his symptoms transiently improved with a hot shower in the hospital. He was diagnosed with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) and admitted for further management.

Background

In the United States, 9 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational marijuana use, and 29 states and DC have legalized medical marijuana. Marijuana use is likely to rise, and with it may arise an increasing incidence of CHS.

The exact prevalence of CHS is not known. Diagnosis is often delayed as there is no reliable diagnostic test. A high index of suspicion is needed for prompt diagnosis.

CHS was first described in 2004 in South Australia and since then many case reports have been published. Marijuana has both proemetic and antiemetic effects. Unlike its antiemetic effect, the pathophysiology of the proemetic effect of marijuana is not well understood.

Key clinical features

CHS typically has three phases. Initially patients present with prodromal symptoms of abdominal discomfort and nausea. There is no emesis at this early phase. Patients are still able to tolerate a liquid diet in this prodromal phase.

This is followed by a more active phase of intractable vomiting, which is relieved by hot showers or baths. Most patients take compulsively long hot showers or baths many times a day. Also, they develop diaphoresis, restlessness, agitation, and weight loss.

The active phase is followed by a recovery phase when symptoms resolve and patients return to baseline, only to have it recur if marijuana use continues.

Diagnostic approach and management

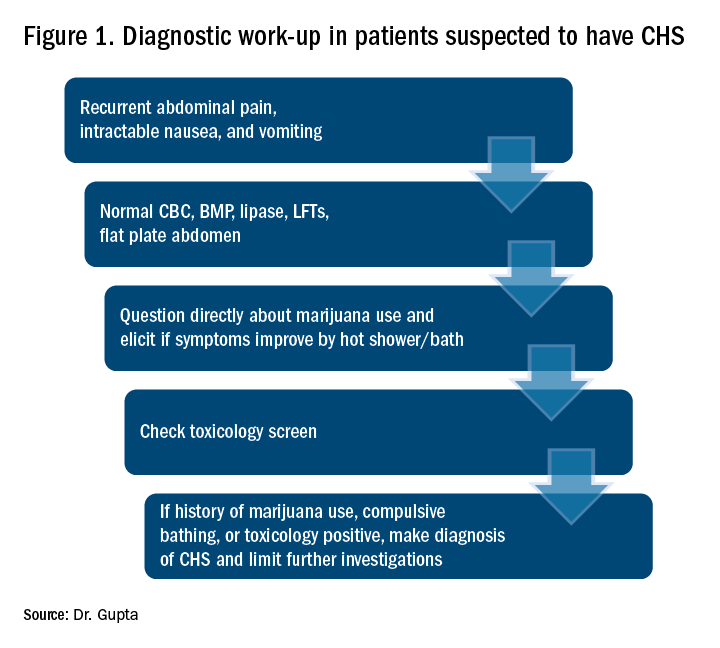

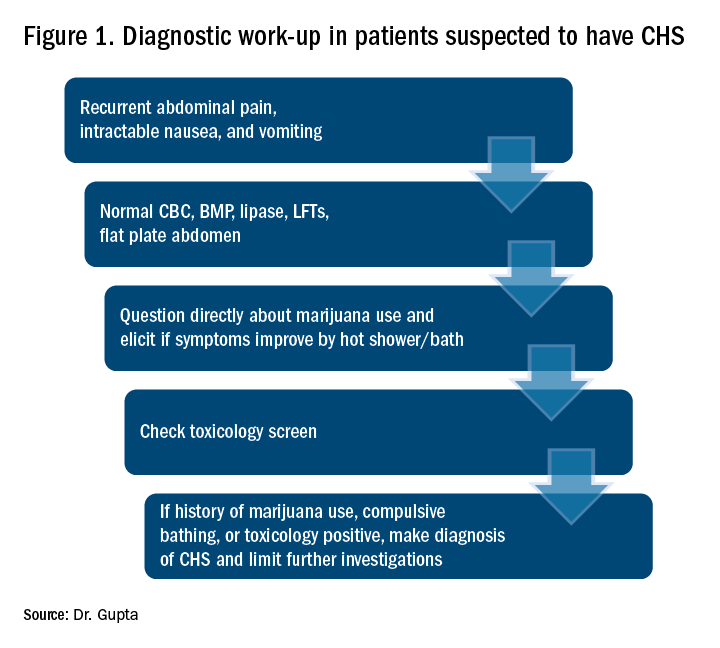

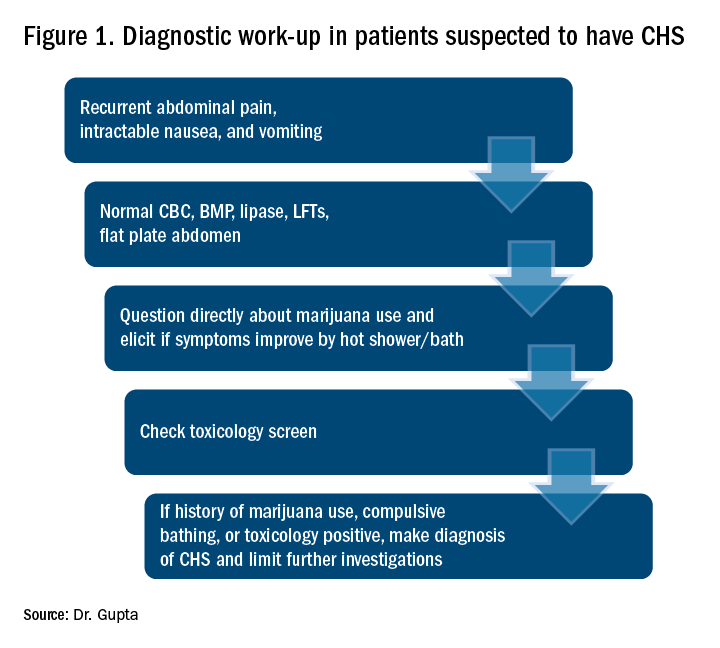

CHS should be suspected in patients coming in with recurrent symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and who have normal CBC, basic metabolic panel, lipase, and liver function tests. Patients should be directly questioned about marijuana use and whether symptoms are relieved with hot showers. A toxicology screen should be done. For patients with marijuana use and compulsive hot showers, further work up of their symptoms (e.g., upper endoscopy, abdominal ultrasound, and/or nuclear medicine emptying study) should be avoided. Figure 1 shows the suggested work-up.

The differential diagnosis for recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting is chronic pancreatitis, gastroparesis, severe gastritis, medication adverse effects (especially GLP1 receptor agonists), cyclic vomiting syndrome, psychogenic vomiting, and (with the rise of narcotic abuse) narcotic bowel syndrome.

Our patient had a history of diabetes with an HbA1c at goal and a normal nuclear medicine gastric-emptying study (6% retention at 4 hours). He was also on liraglutide, but his symptoms predated this medicine use.

The mainstay of treatment for CHS is supportive therapy with intravenous fluids and antiemetics like 5-HT3-receptor antagonists (ondansetron); D2-receptor antagonists (metoclopramide); and H1-receptor antagonists (diphenhydramine). The effectiveness of these agents is limited, which is also a clue for the diagnosis of CHS. If traditional agents fail in controlling the symptoms, haloperidol can be tried, but it has been used with limited success. Our patient did not respond to traditional antiemetics, but responded well to a small dose of lorazepam. Even though a benzodiazepine is not the mainstay of treatment, it may be tried if other agents fail. Acid-suppression therapy with a proton pump inhibitor should be used as esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) usually reveals mild gastritis and esophagitis, as in our patient. Narcotic use should be avoided for management of abdominal pain.

Patients should be counseled against marijuana use. This may be difficult if marijuana is being used as an appetite stimulant or for treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. If willing, patients should be referred to a substance abuse rehabilitation center.

Back to the case

In this case, after a diagnosis of CHS was made, the patient was counseled against marijuana use. His abdominal pain and intractable vomiting did not improve with conservative management of n.p.o status, prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, and ondansetron. He was given a trial of low-dose lorazepam with significant improvement in his symptoms. He was counseled extensively against marijuana use and discharged. A follow-up phone call at 3 months showed continued abstinence and no recurrence of symptoms.

Dr. Gupta is a hospitalist at Yale New Haven Health and Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

References

1. Bajgoric S et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A guide for the practising clinician. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210246.

2. Batke M et al. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: A report of eight cases in the united states. Dig Dis Sci. 2010 Nov;55(11):3113-9.

3. Iacopetti CL et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report and review of pathophysiology. Clin Med Res. 2014 Sep;12(1-2):65-7.

4. Hickey JL et al. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Jun. 31(6):1003.e5-6. Epub 2013 Apr 10.

Key points

Suspect CHS for patients with recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting with negative initial work-up.

- Ask directly about marijuana use.

- Ask whether symptoms are relieved with hot shower/ bath.

- Send a toxicology screen.

- Make a diagnosis of CHS if:

1. Positive marijuana use.

2. Symptom improvement with hot baths or

3. Toxicology positive for marijuana.

- Manage conservatively with hydration and antiemetics.

- Suspect CHS if traditional antiemetics are not providing relief .

- If traditional antiemetics fail, trial of haloperidol or low-dose benzodiazepines.

- Avoid narcotics.

- Avoid unnecessary investigations.

- Counsel patients against marijuana use and refer to substance abuse center if patient agrees.

Incidence may increase as marijuana use rises

Incidence may increase as marijuana use rises

Case

WS is a 54-year-old African American male with a medical history of diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and gastroparesis. He has multiple admissions for intractable nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain believed to be from diabetic gastroparesis despite a normal gastric-emptying study. Endoscopy done in prior admission showed duodenitis, gastritis, and esophagitis, and colonoscopy revealed diverticulosis. He had a negative gastric-emptying study of 6% retention at 4 hrs. His last hemoglobin A1c was 5 and his glucose has been well controlled. He is hospitalized again for intractable abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. His examination was unremarkable except for dry mucosa and epigastric tenderness. His labs were also insignificant except for prerenal azotemia. Upon further questioning he admitted to significant marijuana use, and his symptoms transiently improved with a hot shower in the hospital. He was diagnosed with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) and admitted for further management.

Background

In the United States, 9 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational marijuana use, and 29 states and DC have legalized medical marijuana. Marijuana use is likely to rise, and with it may arise an increasing incidence of CHS.

The exact prevalence of CHS is not known. Diagnosis is often delayed as there is no reliable diagnostic test. A high index of suspicion is needed for prompt diagnosis.

CHS was first described in 2004 in South Australia and since then many case reports have been published. Marijuana has both proemetic and antiemetic effects. Unlike its antiemetic effect, the pathophysiology of the proemetic effect of marijuana is not well understood.

Key clinical features

CHS typically has three phases. Initially patients present with prodromal symptoms of abdominal discomfort and nausea. There is no emesis at this early phase. Patients are still able to tolerate a liquid diet in this prodromal phase.

This is followed by a more active phase of intractable vomiting, which is relieved by hot showers or baths. Most patients take compulsively long hot showers or baths many times a day. Also, they develop diaphoresis, restlessness, agitation, and weight loss.

The active phase is followed by a recovery phase when symptoms resolve and patients return to baseline, only to have it recur if marijuana use continues.

Diagnostic approach and management

CHS should be suspected in patients coming in with recurrent symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and who have normal CBC, basic metabolic panel, lipase, and liver function tests. Patients should be directly questioned about marijuana use and whether symptoms are relieved with hot showers. A toxicology screen should be done. For patients with marijuana use and compulsive hot showers, further work up of their symptoms (e.g., upper endoscopy, abdominal ultrasound, and/or nuclear medicine emptying study) should be avoided. Figure 1 shows the suggested work-up.

The differential diagnosis for recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting is chronic pancreatitis, gastroparesis, severe gastritis, medication adverse effects (especially GLP1 receptor agonists), cyclic vomiting syndrome, psychogenic vomiting, and (with the rise of narcotic abuse) narcotic bowel syndrome.

Our patient had a history of diabetes with an HbA1c at goal and a normal nuclear medicine gastric-emptying study (6% retention at 4 hours). He was also on liraglutide, but his symptoms predated this medicine use.

The mainstay of treatment for CHS is supportive therapy with intravenous fluids and antiemetics like 5-HT3-receptor antagonists (ondansetron); D2-receptor antagonists (metoclopramide); and H1-receptor antagonists (diphenhydramine). The effectiveness of these agents is limited, which is also a clue for the diagnosis of CHS. If traditional agents fail in controlling the symptoms, haloperidol can be tried, but it has been used with limited success. Our patient did not respond to traditional antiemetics, but responded well to a small dose of lorazepam. Even though a benzodiazepine is not the mainstay of treatment, it may be tried if other agents fail. Acid-suppression therapy with a proton pump inhibitor should be used as esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) usually reveals mild gastritis and esophagitis, as in our patient. Narcotic use should be avoided for management of abdominal pain.

Patients should be counseled against marijuana use. This may be difficult if marijuana is being used as an appetite stimulant or for treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. If willing, patients should be referred to a substance abuse rehabilitation center.

Back to the case

In this case, after a diagnosis of CHS was made, the patient was counseled against marijuana use. His abdominal pain and intractable vomiting did not improve with conservative management of n.p.o status, prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, and ondansetron. He was given a trial of low-dose lorazepam with significant improvement in his symptoms. He was counseled extensively against marijuana use and discharged. A follow-up phone call at 3 months showed continued abstinence and no recurrence of symptoms.

Dr. Gupta is a hospitalist at Yale New Haven Health and Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

References

1. Bajgoric S et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A guide for the practising clinician. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210246.

2. Batke M et al. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: A report of eight cases in the united states. Dig Dis Sci. 2010 Nov;55(11):3113-9.

3. Iacopetti CL et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report and review of pathophysiology. Clin Med Res. 2014 Sep;12(1-2):65-7.

4. Hickey JL et al. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Jun. 31(6):1003.e5-6. Epub 2013 Apr 10.

Key points

Suspect CHS for patients with recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting with negative initial work-up.

- Ask directly about marijuana use.

- Ask whether symptoms are relieved with hot shower/ bath.

- Send a toxicology screen.

- Make a diagnosis of CHS if:

1. Positive marijuana use.

2. Symptom improvement with hot baths or

3. Toxicology positive for marijuana.

- Manage conservatively with hydration and antiemetics.

- Suspect CHS if traditional antiemetics are not providing relief .

- If traditional antiemetics fail, trial of haloperidol or low-dose benzodiazepines.

- Avoid narcotics.

- Avoid unnecessary investigations.

- Counsel patients against marijuana use and refer to substance abuse center if patient agrees.

Case

WS is a 54-year-old African American male with a medical history of diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and gastroparesis. He has multiple admissions for intractable nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain believed to be from diabetic gastroparesis despite a normal gastric-emptying study. Endoscopy done in prior admission showed duodenitis, gastritis, and esophagitis, and colonoscopy revealed diverticulosis. He had a negative gastric-emptying study of 6% retention at 4 hrs. His last hemoglobin A1c was 5 and his glucose has been well controlled. He is hospitalized again for intractable abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. His examination was unremarkable except for dry mucosa and epigastric tenderness. His labs were also insignificant except for prerenal azotemia. Upon further questioning he admitted to significant marijuana use, and his symptoms transiently improved with a hot shower in the hospital. He was diagnosed with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) and admitted for further management.

Background

In the United States, 9 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational marijuana use, and 29 states and DC have legalized medical marijuana. Marijuana use is likely to rise, and with it may arise an increasing incidence of CHS.

The exact prevalence of CHS is not known. Diagnosis is often delayed as there is no reliable diagnostic test. A high index of suspicion is needed for prompt diagnosis.

CHS was first described in 2004 in South Australia and since then many case reports have been published. Marijuana has both proemetic and antiemetic effects. Unlike its antiemetic effect, the pathophysiology of the proemetic effect of marijuana is not well understood.

Key clinical features

CHS typically has three phases. Initially patients present with prodromal symptoms of abdominal discomfort and nausea. There is no emesis at this early phase. Patients are still able to tolerate a liquid diet in this prodromal phase.

This is followed by a more active phase of intractable vomiting, which is relieved by hot showers or baths. Most patients take compulsively long hot showers or baths many times a day. Also, they develop diaphoresis, restlessness, agitation, and weight loss.

The active phase is followed by a recovery phase when symptoms resolve and patients return to baseline, only to have it recur if marijuana use continues.

Diagnostic approach and management

CHS should be suspected in patients coming in with recurrent symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and who have normal CBC, basic metabolic panel, lipase, and liver function tests. Patients should be directly questioned about marijuana use and whether symptoms are relieved with hot showers. A toxicology screen should be done. For patients with marijuana use and compulsive hot showers, further work up of their symptoms (e.g., upper endoscopy, abdominal ultrasound, and/or nuclear medicine emptying study) should be avoided. Figure 1 shows the suggested work-up.

The differential diagnosis for recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting is chronic pancreatitis, gastroparesis, severe gastritis, medication adverse effects (especially GLP1 receptor agonists), cyclic vomiting syndrome, psychogenic vomiting, and (with the rise of narcotic abuse) narcotic bowel syndrome.

Our patient had a history of diabetes with an HbA1c at goal and a normal nuclear medicine gastric-emptying study (6% retention at 4 hours). He was also on liraglutide, but his symptoms predated this medicine use.

The mainstay of treatment for CHS is supportive therapy with intravenous fluids and antiemetics like 5-HT3-receptor antagonists (ondansetron); D2-receptor antagonists (metoclopramide); and H1-receptor antagonists (diphenhydramine). The effectiveness of these agents is limited, which is also a clue for the diagnosis of CHS. If traditional agents fail in controlling the symptoms, haloperidol can be tried, but it has been used with limited success. Our patient did not respond to traditional antiemetics, but responded well to a small dose of lorazepam. Even though a benzodiazepine is not the mainstay of treatment, it may be tried if other agents fail. Acid-suppression therapy with a proton pump inhibitor should be used as esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) usually reveals mild gastritis and esophagitis, as in our patient. Narcotic use should be avoided for management of abdominal pain.

Patients should be counseled against marijuana use. This may be difficult if marijuana is being used as an appetite stimulant or for treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. If willing, patients should be referred to a substance abuse rehabilitation center.

Back to the case

In this case, after a diagnosis of CHS was made, the patient was counseled against marijuana use. His abdominal pain and intractable vomiting did not improve with conservative management of n.p.o status, prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, and ondansetron. He was given a trial of low-dose lorazepam with significant improvement in his symptoms. He was counseled extensively against marijuana use and discharged. A follow-up phone call at 3 months showed continued abstinence and no recurrence of symptoms.

Dr. Gupta is a hospitalist at Yale New Haven Health and Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

References

1. Bajgoric S et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A guide for the practising clinician. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210246.

2. Batke M et al. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: A report of eight cases in the united states. Dig Dis Sci. 2010 Nov;55(11):3113-9.

3. Iacopetti CL et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report and review of pathophysiology. Clin Med Res. 2014 Sep;12(1-2):65-7.

4. Hickey JL et al. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Jun. 31(6):1003.e5-6. Epub 2013 Apr 10.

Key points

Suspect CHS for patients with recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting with negative initial work-up.

- Ask directly about marijuana use.

- Ask whether symptoms are relieved with hot shower/ bath.

- Send a toxicology screen.

- Make a diagnosis of CHS if:

1. Positive marijuana use.

2. Symptom improvement with hot baths or

3. Toxicology positive for marijuana.

- Manage conservatively with hydration and antiemetics.

- Suspect CHS if traditional antiemetics are not providing relief .

- If traditional antiemetics fail, trial of haloperidol or low-dose benzodiazepines.

- Avoid narcotics.

- Avoid unnecessary investigations.

- Counsel patients against marijuana use and refer to substance abuse center if patient agrees.