User login

What is the best antibiotic treatment for C.difficile-associated diarrhea?

Case

An 84-year-old woman presents with watery diarrhea. She recently received a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a hospitalization for pneumonia. Her temperature is 101 degrees, her heart rate is 110 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate is 22 breaths per minute. Her abdominal exam is significant for mild distention, hyperactive bowel sounds, and diffuse, mild tenderness without rebound or guarding. Her white blood cell count is 18,200 cells/mm3. You suspect C. difficile infection. Should you treat empirically with antibiotics and, if so, which antibiotic should you prescribe?

Overview

C. difficile is an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus that produces spores and toxins. In 1978, C. difficile was identified as the causative agent for antibiotic-associated diarrhea.1 The portal of entry is via the fecal-oral route.

Some patients carry C. difficile in their intestinal flora and show no signs of infection. Patients who develop symptoms commonly present with profuse, watery diarrhea. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain also can be seen. Severe cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) can present with significant abdominal pain and multisystem organ failure, with toxic megacolon resulting from toxin production and ileus.2 In severe cases due to ileus, diarrhea may be absent. Risk of mortality in severe cases is high, with some reviews citing death rates of 57% in patients requiring total colectomy.3 Risk factors for developing CDAD include the prior or current use of antibiotics, advanced age, hospitalization, and prior gastrointestinal surgery or procedures.4

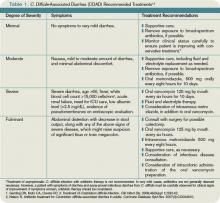

The initial CDAD treatment involves removal of the agent that incited the infection. In most cases, this means discontinuation of an antimicrobial agent. Removal of the inciting agent allows restoration of the normal bowel flora. In mild CDAD cases, this may be sufficient therapy. However, most CDAD cases require treatment. Although many antimicrobial and probiotic agents have been used in CDAD treatment, metronidazole and vancomycin are the most commonly prescribed agents. There is an ongoing debate as to which should be considered the first-line agent.

Review of the Data

Metronidazole and vancomycin have the longest histories of use and are the most studied agents in CDAD. Metronidazole is prescribed 250 mg four times daily (or 500 mg twice daily) for 14 days. It is reasonably tolerated, although it can cause a metallic taste in the mouth. Vancomycin is given 125 mg four times daily (or 500 mg three times daily) for 10 to 14 days. Unlike metronidazole, which can be given by mouth or intravenously, only oral vancomycin is effective in CDAD.

Historically, metronidazole has been prescribed more frequently as the first-line agent in CDAD. Proponents of the drug tout its low cost and the importance of minimizing the development of vancomycin-resistant enteric pathogens. There are two small, prospective, randomized studies comparing the efficacy of the agents against one another in the treatment of C. difficile infection, with similar efficacy demonstrated in both studies. In the early 1980s, Teasley and colleagues randomized 94 patients with C. difficile infection to either metronidazole or vancomycin.5 All the patients receiving vancomycin resolved their disease; 95% of patients receiving metronidazole were cured. The differences were not statistically significant.

In the mid-1990s, Wenisch and colleagues randomized patients with C. difficile infection to receive vancomycin, metronidazole, fusidic acid, or teicoplanin therapy.6 Ninety-four percent of patients in both the vancomycin and metronidazole groups were cured.

However, since 2000, investigators have reported higher failure rates with metronidazole therapy in C. difficile infections. For example, in 2005, Pepin and colleagues reviewed cases of C. difficile infections at a hospital in Quebec.7 They determined the number of patients with C. difficile infection initially treated with metronidazole who required additional therapy had markedly increased. Between 1991 and 2002, 9.6% of patients who initially were treated with metronidazole required a switch to vancomycin (or the addition of vancomycin) because of a disappointing response. This figure doubled to 25.7% in 2003-2004. The 60-day probability of recurrence also increased in the 2003-2004 test group (47.2%), compared with the 1991-2002 group (20.8%). Both results were statistically significant. Such data contributed to the debate regarding whether metronidazole or vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of C. difficile infections.

In 2007, Zar and colleagues studied the efficacy of metronidazole and vancomycin in the treatment of CDAD patients, but the study stratified patients according to disease severity.8 This allowed the authors to investigate whether one agent was superior in treating mild or severe CDAD. They determined disease severity by assigning points to individual patient characteristics. Patients with two or more points were deemed to have “severe” CDAD.

The investigators assigned one point for each of the following patient characteristics: temperature >38.3 degrees Celsius, age >60 years, albumin level <2.5 mg/dL, and white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3 within 48 hours of enrolling in the study. Any patient with endoscopic evidence of pseudomembrane formation or admission to the intensive-care unit (ICU) for CDAD treatment was considered to have severe disease.

This was a prospective, randomized controlled trial of 150 patients. Patients were randomly prescribed 500 mg metronidazole by mouth three times daily or 125 mg of vancomycin by mouth four times daily. Patients with mild CDAD had similar cure rates: 90% metronidazole versus 98% vancomycin (P=0.36). However, patients with severe CDAD fared statistically better when treated with oral vancomycin. Ninety-seven percent of severe CDAD patients treated with oral vancomycin had a clinical cure, while only 76% of those treated with metronidazole were cured (P=0.02). Recurrence of the disease was similar in each treatment group.

Based on this study, metronidazole and vancomycin appear equally effective in the treatment of mild CDAD, but vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of patients with severe CDAD.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors predisposing her to developing CDAD. She was of advanced age and took a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a recent hospitalization. She also presented with signs consistent with a severe case of CDAD. She had a fever, a white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3, and was older than 60. Thus, she should be treated with supportive care, placed on contact precautions, and administered oral vancomycin 125 mg by mouth every six hours for 10 days as empiric therapy for CDAD. Stool cultures should be sent to confirm the presence of the C. difficile toxin.

Bottom Line

The appropriate antibiotic choice to treat CDAD in any patient depends upon the clinical severity of the disease. Treat patients with mild CDAD with metronidazole; prescribe oral vancomycin for patients with severe CDAD. TH

Dr. Mattison, instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is a hospitalist and co-director of the Inpatient Geriatrics Unit at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. Dr. Li, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is director of hospital medicine and associate chief of BIDMC’s Division of General Medicine and Primary Care.

References

1.Bartlett JG, Moon N, Chang TW, Taylor N, Onderdonk AB. Role of C. difficile in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75(5):778-782.

2.Poutanen SM, Simor AE. C. difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):51-58.

3.Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant C. difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):363-372.

4.Bartlett JG. Narrative review: the new epidemic of C. difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):758-764.

5.Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for C. difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-1046.

6.Wenisch C, Parschalk B, Hasenhündl M, Hirschl AM, Graninger W. Comparison of vancomycin, teicoplanin, metronidazole, and fusidic acid for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:813-818.

7.Pepin J, Alary M, Valiquette L, et al. Increasing risk of relapse after treatment of C. difficile colitis in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1591-1597.

8.Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(3):302-307.

Case

An 84-year-old woman presents with watery diarrhea. She recently received a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a hospitalization for pneumonia. Her temperature is 101 degrees, her heart rate is 110 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate is 22 breaths per minute. Her abdominal exam is significant for mild distention, hyperactive bowel sounds, and diffuse, mild tenderness without rebound or guarding. Her white blood cell count is 18,200 cells/mm3. You suspect C. difficile infection. Should you treat empirically with antibiotics and, if so, which antibiotic should you prescribe?

Overview

C. difficile is an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus that produces spores and toxins. In 1978, C. difficile was identified as the causative agent for antibiotic-associated diarrhea.1 The portal of entry is via the fecal-oral route.

Some patients carry C. difficile in their intestinal flora and show no signs of infection. Patients who develop symptoms commonly present with profuse, watery diarrhea. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain also can be seen. Severe cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) can present with significant abdominal pain and multisystem organ failure, with toxic megacolon resulting from toxin production and ileus.2 In severe cases due to ileus, diarrhea may be absent. Risk of mortality in severe cases is high, with some reviews citing death rates of 57% in patients requiring total colectomy.3 Risk factors for developing CDAD include the prior or current use of antibiotics, advanced age, hospitalization, and prior gastrointestinal surgery or procedures.4

The initial CDAD treatment involves removal of the agent that incited the infection. In most cases, this means discontinuation of an antimicrobial agent. Removal of the inciting agent allows restoration of the normal bowel flora. In mild CDAD cases, this may be sufficient therapy. However, most CDAD cases require treatment. Although many antimicrobial and probiotic agents have been used in CDAD treatment, metronidazole and vancomycin are the most commonly prescribed agents. There is an ongoing debate as to which should be considered the first-line agent.

Review of the Data

Metronidazole and vancomycin have the longest histories of use and are the most studied agents in CDAD. Metronidazole is prescribed 250 mg four times daily (or 500 mg twice daily) for 14 days. It is reasonably tolerated, although it can cause a metallic taste in the mouth. Vancomycin is given 125 mg four times daily (or 500 mg three times daily) for 10 to 14 days. Unlike metronidazole, which can be given by mouth or intravenously, only oral vancomycin is effective in CDAD.

Historically, metronidazole has been prescribed more frequently as the first-line agent in CDAD. Proponents of the drug tout its low cost and the importance of minimizing the development of vancomycin-resistant enteric pathogens. There are two small, prospective, randomized studies comparing the efficacy of the agents against one another in the treatment of C. difficile infection, with similar efficacy demonstrated in both studies. In the early 1980s, Teasley and colleagues randomized 94 patients with C. difficile infection to either metronidazole or vancomycin.5 All the patients receiving vancomycin resolved their disease; 95% of patients receiving metronidazole were cured. The differences were not statistically significant.

In the mid-1990s, Wenisch and colleagues randomized patients with C. difficile infection to receive vancomycin, metronidazole, fusidic acid, or teicoplanin therapy.6 Ninety-four percent of patients in both the vancomycin and metronidazole groups were cured.

However, since 2000, investigators have reported higher failure rates with metronidazole therapy in C. difficile infections. For example, in 2005, Pepin and colleagues reviewed cases of C. difficile infections at a hospital in Quebec.7 They determined the number of patients with C. difficile infection initially treated with metronidazole who required additional therapy had markedly increased. Between 1991 and 2002, 9.6% of patients who initially were treated with metronidazole required a switch to vancomycin (or the addition of vancomycin) because of a disappointing response. This figure doubled to 25.7% in 2003-2004. The 60-day probability of recurrence also increased in the 2003-2004 test group (47.2%), compared with the 1991-2002 group (20.8%). Both results were statistically significant. Such data contributed to the debate regarding whether metronidazole or vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of C. difficile infections.

In 2007, Zar and colleagues studied the efficacy of metronidazole and vancomycin in the treatment of CDAD patients, but the study stratified patients according to disease severity.8 This allowed the authors to investigate whether one agent was superior in treating mild or severe CDAD. They determined disease severity by assigning points to individual patient characteristics. Patients with two or more points were deemed to have “severe” CDAD.

The investigators assigned one point for each of the following patient characteristics: temperature >38.3 degrees Celsius, age >60 years, albumin level <2.5 mg/dL, and white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3 within 48 hours of enrolling in the study. Any patient with endoscopic evidence of pseudomembrane formation or admission to the intensive-care unit (ICU) for CDAD treatment was considered to have severe disease.

This was a prospective, randomized controlled trial of 150 patients. Patients were randomly prescribed 500 mg metronidazole by mouth three times daily or 125 mg of vancomycin by mouth four times daily. Patients with mild CDAD had similar cure rates: 90% metronidazole versus 98% vancomycin (P=0.36). However, patients with severe CDAD fared statistically better when treated with oral vancomycin. Ninety-seven percent of severe CDAD patients treated with oral vancomycin had a clinical cure, while only 76% of those treated with metronidazole were cured (P=0.02). Recurrence of the disease was similar in each treatment group.

Based on this study, metronidazole and vancomycin appear equally effective in the treatment of mild CDAD, but vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of patients with severe CDAD.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors predisposing her to developing CDAD. She was of advanced age and took a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a recent hospitalization. She also presented with signs consistent with a severe case of CDAD. She had a fever, a white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3, and was older than 60. Thus, she should be treated with supportive care, placed on contact precautions, and administered oral vancomycin 125 mg by mouth every six hours for 10 days as empiric therapy for CDAD. Stool cultures should be sent to confirm the presence of the C. difficile toxin.

Bottom Line

The appropriate antibiotic choice to treat CDAD in any patient depends upon the clinical severity of the disease. Treat patients with mild CDAD with metronidazole; prescribe oral vancomycin for patients with severe CDAD. TH

Dr. Mattison, instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is a hospitalist and co-director of the Inpatient Geriatrics Unit at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. Dr. Li, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is director of hospital medicine and associate chief of BIDMC’s Division of General Medicine and Primary Care.

References

1.Bartlett JG, Moon N, Chang TW, Taylor N, Onderdonk AB. Role of C. difficile in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75(5):778-782.

2.Poutanen SM, Simor AE. C. difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):51-58.

3.Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant C. difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):363-372.

4.Bartlett JG. Narrative review: the new epidemic of C. difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):758-764.

5.Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for C. difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-1046.

6.Wenisch C, Parschalk B, Hasenhündl M, Hirschl AM, Graninger W. Comparison of vancomycin, teicoplanin, metronidazole, and fusidic acid for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:813-818.

7.Pepin J, Alary M, Valiquette L, et al. Increasing risk of relapse after treatment of C. difficile colitis in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1591-1597.

8.Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(3):302-307.

Case

An 84-year-old woman presents with watery diarrhea. She recently received a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a hospitalization for pneumonia. Her temperature is 101 degrees, her heart rate is 110 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate is 22 breaths per minute. Her abdominal exam is significant for mild distention, hyperactive bowel sounds, and diffuse, mild tenderness without rebound or guarding. Her white blood cell count is 18,200 cells/mm3. You suspect C. difficile infection. Should you treat empirically with antibiotics and, if so, which antibiotic should you prescribe?

Overview

C. difficile is an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus that produces spores and toxins. In 1978, C. difficile was identified as the causative agent for antibiotic-associated diarrhea.1 The portal of entry is via the fecal-oral route.

Some patients carry C. difficile in their intestinal flora and show no signs of infection. Patients who develop symptoms commonly present with profuse, watery diarrhea. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain also can be seen. Severe cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) can present with significant abdominal pain and multisystem organ failure, with toxic megacolon resulting from toxin production and ileus.2 In severe cases due to ileus, diarrhea may be absent. Risk of mortality in severe cases is high, with some reviews citing death rates of 57% in patients requiring total colectomy.3 Risk factors for developing CDAD include the prior or current use of antibiotics, advanced age, hospitalization, and prior gastrointestinal surgery or procedures.4

The initial CDAD treatment involves removal of the agent that incited the infection. In most cases, this means discontinuation of an antimicrobial agent. Removal of the inciting agent allows restoration of the normal bowel flora. In mild CDAD cases, this may be sufficient therapy. However, most CDAD cases require treatment. Although many antimicrobial and probiotic agents have been used in CDAD treatment, metronidazole and vancomycin are the most commonly prescribed agents. There is an ongoing debate as to which should be considered the first-line agent.

Review of the Data

Metronidazole and vancomycin have the longest histories of use and are the most studied agents in CDAD. Metronidazole is prescribed 250 mg four times daily (or 500 mg twice daily) for 14 days. It is reasonably tolerated, although it can cause a metallic taste in the mouth. Vancomycin is given 125 mg four times daily (or 500 mg three times daily) for 10 to 14 days. Unlike metronidazole, which can be given by mouth or intravenously, only oral vancomycin is effective in CDAD.

Historically, metronidazole has been prescribed more frequently as the first-line agent in CDAD. Proponents of the drug tout its low cost and the importance of minimizing the development of vancomycin-resistant enteric pathogens. There are two small, prospective, randomized studies comparing the efficacy of the agents against one another in the treatment of C. difficile infection, with similar efficacy demonstrated in both studies. In the early 1980s, Teasley and colleagues randomized 94 patients with C. difficile infection to either metronidazole or vancomycin.5 All the patients receiving vancomycin resolved their disease; 95% of patients receiving metronidazole were cured. The differences were not statistically significant.

In the mid-1990s, Wenisch and colleagues randomized patients with C. difficile infection to receive vancomycin, metronidazole, fusidic acid, or teicoplanin therapy.6 Ninety-four percent of patients in both the vancomycin and metronidazole groups were cured.

However, since 2000, investigators have reported higher failure rates with metronidazole therapy in C. difficile infections. For example, in 2005, Pepin and colleagues reviewed cases of C. difficile infections at a hospital in Quebec.7 They determined the number of patients with C. difficile infection initially treated with metronidazole who required additional therapy had markedly increased. Between 1991 and 2002, 9.6% of patients who initially were treated with metronidazole required a switch to vancomycin (or the addition of vancomycin) because of a disappointing response. This figure doubled to 25.7% in 2003-2004. The 60-day probability of recurrence also increased in the 2003-2004 test group (47.2%), compared with the 1991-2002 group (20.8%). Both results were statistically significant. Such data contributed to the debate regarding whether metronidazole or vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of C. difficile infections.

In 2007, Zar and colleagues studied the efficacy of metronidazole and vancomycin in the treatment of CDAD patients, but the study stratified patients according to disease severity.8 This allowed the authors to investigate whether one agent was superior in treating mild or severe CDAD. They determined disease severity by assigning points to individual patient characteristics. Patients with two or more points were deemed to have “severe” CDAD.

The investigators assigned one point for each of the following patient characteristics: temperature >38.3 degrees Celsius, age >60 years, albumin level <2.5 mg/dL, and white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3 within 48 hours of enrolling in the study. Any patient with endoscopic evidence of pseudomembrane formation or admission to the intensive-care unit (ICU) for CDAD treatment was considered to have severe disease.

This was a prospective, randomized controlled trial of 150 patients. Patients were randomly prescribed 500 mg metronidazole by mouth three times daily or 125 mg of vancomycin by mouth four times daily. Patients with mild CDAD had similar cure rates: 90% metronidazole versus 98% vancomycin (P=0.36). However, patients with severe CDAD fared statistically better when treated with oral vancomycin. Ninety-seven percent of severe CDAD patients treated with oral vancomycin had a clinical cure, while only 76% of those treated with metronidazole were cured (P=0.02). Recurrence of the disease was similar in each treatment group.

Based on this study, metronidazole and vancomycin appear equally effective in the treatment of mild CDAD, but vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of patients with severe CDAD.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors predisposing her to developing CDAD. She was of advanced age and took a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a recent hospitalization. She also presented with signs consistent with a severe case of CDAD. She had a fever, a white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3, and was older than 60. Thus, she should be treated with supportive care, placed on contact precautions, and administered oral vancomycin 125 mg by mouth every six hours for 10 days as empiric therapy for CDAD. Stool cultures should be sent to confirm the presence of the C. difficile toxin.

Bottom Line

The appropriate antibiotic choice to treat CDAD in any patient depends upon the clinical severity of the disease. Treat patients with mild CDAD with metronidazole; prescribe oral vancomycin for patients with severe CDAD. TH

Dr. Mattison, instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is a hospitalist and co-director of the Inpatient Geriatrics Unit at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. Dr. Li, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is director of hospital medicine and associate chief of BIDMC’s Division of General Medicine and Primary Care.

References

1.Bartlett JG, Moon N, Chang TW, Taylor N, Onderdonk AB. Role of C. difficile in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75(5):778-782.

2.Poutanen SM, Simor AE. C. difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):51-58.

3.Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant C. difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):363-372.

4.Bartlett JG. Narrative review: the new epidemic of C. difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):758-764.

5.Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for C. difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-1046.

6.Wenisch C, Parschalk B, Hasenhündl M, Hirschl AM, Graninger W. Comparison of vancomycin, teicoplanin, metronidazole, and fusidic acid for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:813-818.

7.Pepin J, Alary M, Valiquette L, et al. Increasing risk of relapse after treatment of C. difficile colitis in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1591-1597.

8.Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(3):302-307.