User login

John Nelson: Why Spinal Epidural Abcess Poses A Particular Liability Risk for Hospitalists

Delayed diagnosis of, or treatment for, a spinal epidural abscess (SEA): that will be the case over which you are sued.

Over the last 15 years, I’ve served as an expert witness for six or seven malpractice cases. Most were related to spinal cord injuries, and in all but one of those, the etiology was epidural abscess. I’ve been asked to review about 40 or 50 additional cases, and while I’ve turned them down (I just don’t have time to do reviews), I nearly always ask about the clinical picture in every case. A significant number have been SEA-related. This experience has convinced me that SEA poses a particular liability risk for hospitalists.

Of course, it is patients who bear the real risk and unfortunate consequences of SEA. Being a defendant physician in a lawsuit is stressful, but it’s nothing compared to the distress of permanent loss of neurologic function. To prevent permanent sequelae, we need to maintain a very high index of suspicion to try to make a prompt diagnosis, and ensure immediate intervention once the diagnosis is made.

Data from Malpractice Insurers

I had the pleasure of getting to know a number of leaders at The Doctor’s Company, a large malpractice insurer that provides malpractice policies for all specialties, including a lot of hospitalists. From 2007 to 2011, they closed 28 SEA-related claims, for which they spent an average of $212,000 defending each one. Eleven of the 28 resulted in indemnity payments averaging $754,000 each (median was $455,000). These dollar amounts are roughly double what might be seen for all other claims and reflect only the payments made on behalf of the company’s insured doctors. The total award to each patient was likely much higher, because in most cases, several defendants (other doctors and a hospital) probably paid money to the patient.

The Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA) “is the insurance industry trade association representing domestic and international medical professional liability insurance companies.” Their member malpractice insurance companies have the opportunity to report claims data that PIAA aggregates and makes available. Data from 2002 to 2011 showed 312 closed claims related to any diagnosis (not just SEA) for hospitalists, with an average indemnity payment of $272,553 (the highest hospitalist-related payment was $1.4 million). The most common allegations related to paid claims were 1) “errors in diagnosis,” 2) “failure/delay in referral or consultation,” and 3) “failure to supervise/monitor case.” Although only three of the 312 claims were related to “diseases of the spinal cord,” that was exceeded in frequency only by “diabetes.”

I think these numbers from the malpractice insurance industry support my concern that SEA is a high-risk area, but it doesn’t really support my anecdotal experience that SEA is clearly hospitalists’ highest-risk area. Maybe SEA is only one of several high-risk areas. Nevertheless, I’m going to stick to my sensationalist guns to get your attention.

Why Is Epidural Abscess a High Risk?

There likely are several reasons SEA is a treacherous liability problem. It can lead to devastating permanent disabling neurologic deficits in people who were previously healthy, and if the medical care was substandard, then significant financial compensation seems appropriate.

Delays in diagnosis of SEA are common. It can be a very sneaky illness that in the early stages is very easy to confuse with less-serious causes of back pain or fever. Even though I think about this particular diagnosis all the time, just last year I had a patient who reported an increase in his usual back pain. I felt reassured that he had no neurologic deficit or fever, and took the time to explain why there was no reason to repeat the spine MRI that had been done about two weeks prior to admission. But he was insistent that he have another MRI, and after a day or two I finally agreed to order it, assuring him it would not explain the cause of his pain. But it did. He had a significant SEA and went to emergency surgery. I was stunned, and profoundly relieved that he had no neurologic sequelae.

One of the remarkable things I’ve seen in the cases I’ve reviewed is that even when there is clear cause for concern, there is too often no action taken. In a number of cases, the nurses’ note indicates increasing back pain, loss of ability to stand, urinary retention, and other alarming signs. Yet the doctors either never learn of these issues, or they choose to attribute them to other causes.

Even when the diagnosis of SEA is clearly established, it is all too common for doctors caring for the patient not to act on this information. In several cases I reviewed, a radiologist had documented reporting the diagnosis to the hospitalist (and in one case the neurosurgeon as well), yet nothing was done for 12 hours or more. It is hard to imagine that establishing this diagnosis doesn’t reliably lead to an emergent response, but it doesn’t. (In some cases, nonsurgical management may be an option, but in these malpractices cases, there was just a failure to act on the diagnosis with any sort of plan.)

Practice Management Perspective

I usually discuss hospitalist practice operations in this space—things like work schedules and compensation. But attending to risk management is one component of effective practice operations, so I thought I’d raise the topic here. Obviously, there is a lot more to hospitalist risk management than one diagnosis, but a column on the whole universe of risk management would probably serve no purpose other than as a sleep aid. I hope that by focusing solely on SEA, there is some chance that you’ll remember it, and you’ll make sure that you disprove my first two sentences.

Lowering your risk of a malpractice lawsuit is valuable and worth spending time on. But far more important is that by keeping the diagnosis in mind, and ensuring that you act emergently when there is cause for concern, you might save someone from the devastating consequences of this disease.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Delayed diagnosis of, or treatment for, a spinal epidural abscess (SEA): that will be the case over which you are sued.

Over the last 15 years, I’ve served as an expert witness for six or seven malpractice cases. Most were related to spinal cord injuries, and in all but one of those, the etiology was epidural abscess. I’ve been asked to review about 40 or 50 additional cases, and while I’ve turned them down (I just don’t have time to do reviews), I nearly always ask about the clinical picture in every case. A significant number have been SEA-related. This experience has convinced me that SEA poses a particular liability risk for hospitalists.

Of course, it is patients who bear the real risk and unfortunate consequences of SEA. Being a defendant physician in a lawsuit is stressful, but it’s nothing compared to the distress of permanent loss of neurologic function. To prevent permanent sequelae, we need to maintain a very high index of suspicion to try to make a prompt diagnosis, and ensure immediate intervention once the diagnosis is made.

Data from Malpractice Insurers

I had the pleasure of getting to know a number of leaders at The Doctor’s Company, a large malpractice insurer that provides malpractice policies for all specialties, including a lot of hospitalists. From 2007 to 2011, they closed 28 SEA-related claims, for which they spent an average of $212,000 defending each one. Eleven of the 28 resulted in indemnity payments averaging $754,000 each (median was $455,000). These dollar amounts are roughly double what might be seen for all other claims and reflect only the payments made on behalf of the company’s insured doctors. The total award to each patient was likely much higher, because in most cases, several defendants (other doctors and a hospital) probably paid money to the patient.

The Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA) “is the insurance industry trade association representing domestic and international medical professional liability insurance companies.” Their member malpractice insurance companies have the opportunity to report claims data that PIAA aggregates and makes available. Data from 2002 to 2011 showed 312 closed claims related to any diagnosis (not just SEA) for hospitalists, with an average indemnity payment of $272,553 (the highest hospitalist-related payment was $1.4 million). The most common allegations related to paid claims were 1) “errors in diagnosis,” 2) “failure/delay in referral or consultation,” and 3) “failure to supervise/monitor case.” Although only three of the 312 claims were related to “diseases of the spinal cord,” that was exceeded in frequency only by “diabetes.”

I think these numbers from the malpractice insurance industry support my concern that SEA is a high-risk area, but it doesn’t really support my anecdotal experience that SEA is clearly hospitalists’ highest-risk area. Maybe SEA is only one of several high-risk areas. Nevertheless, I’m going to stick to my sensationalist guns to get your attention.

Why Is Epidural Abscess a High Risk?

There likely are several reasons SEA is a treacherous liability problem. It can lead to devastating permanent disabling neurologic deficits in people who were previously healthy, and if the medical care was substandard, then significant financial compensation seems appropriate.

Delays in diagnosis of SEA are common. It can be a very sneaky illness that in the early stages is very easy to confuse with less-serious causes of back pain or fever. Even though I think about this particular diagnosis all the time, just last year I had a patient who reported an increase in his usual back pain. I felt reassured that he had no neurologic deficit or fever, and took the time to explain why there was no reason to repeat the spine MRI that had been done about two weeks prior to admission. But he was insistent that he have another MRI, and after a day or two I finally agreed to order it, assuring him it would not explain the cause of his pain. But it did. He had a significant SEA and went to emergency surgery. I was stunned, and profoundly relieved that he had no neurologic sequelae.

One of the remarkable things I’ve seen in the cases I’ve reviewed is that even when there is clear cause for concern, there is too often no action taken. In a number of cases, the nurses’ note indicates increasing back pain, loss of ability to stand, urinary retention, and other alarming signs. Yet the doctors either never learn of these issues, or they choose to attribute them to other causes.

Even when the diagnosis of SEA is clearly established, it is all too common for doctors caring for the patient not to act on this information. In several cases I reviewed, a radiologist had documented reporting the diagnosis to the hospitalist (and in one case the neurosurgeon as well), yet nothing was done for 12 hours or more. It is hard to imagine that establishing this diagnosis doesn’t reliably lead to an emergent response, but it doesn’t. (In some cases, nonsurgical management may be an option, but in these malpractices cases, there was just a failure to act on the diagnosis with any sort of plan.)

Practice Management Perspective

I usually discuss hospitalist practice operations in this space—things like work schedules and compensation. But attending to risk management is one component of effective practice operations, so I thought I’d raise the topic here. Obviously, there is a lot more to hospitalist risk management than one diagnosis, but a column on the whole universe of risk management would probably serve no purpose other than as a sleep aid. I hope that by focusing solely on SEA, there is some chance that you’ll remember it, and you’ll make sure that you disprove my first two sentences.

Lowering your risk of a malpractice lawsuit is valuable and worth spending time on. But far more important is that by keeping the diagnosis in mind, and ensuring that you act emergently when there is cause for concern, you might save someone from the devastating consequences of this disease.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Delayed diagnosis of, or treatment for, a spinal epidural abscess (SEA): that will be the case over which you are sued.

Over the last 15 years, I’ve served as an expert witness for six or seven malpractice cases. Most were related to spinal cord injuries, and in all but one of those, the etiology was epidural abscess. I’ve been asked to review about 40 or 50 additional cases, and while I’ve turned them down (I just don’t have time to do reviews), I nearly always ask about the clinical picture in every case. A significant number have been SEA-related. This experience has convinced me that SEA poses a particular liability risk for hospitalists.

Of course, it is patients who bear the real risk and unfortunate consequences of SEA. Being a defendant physician in a lawsuit is stressful, but it’s nothing compared to the distress of permanent loss of neurologic function. To prevent permanent sequelae, we need to maintain a very high index of suspicion to try to make a prompt diagnosis, and ensure immediate intervention once the diagnosis is made.

Data from Malpractice Insurers

I had the pleasure of getting to know a number of leaders at The Doctor’s Company, a large malpractice insurer that provides malpractice policies for all specialties, including a lot of hospitalists. From 2007 to 2011, they closed 28 SEA-related claims, for which they spent an average of $212,000 defending each one. Eleven of the 28 resulted in indemnity payments averaging $754,000 each (median was $455,000). These dollar amounts are roughly double what might be seen for all other claims and reflect only the payments made on behalf of the company’s insured doctors. The total award to each patient was likely much higher, because in most cases, several defendants (other doctors and a hospital) probably paid money to the patient.

The Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA) “is the insurance industry trade association representing domestic and international medical professional liability insurance companies.” Their member malpractice insurance companies have the opportunity to report claims data that PIAA aggregates and makes available. Data from 2002 to 2011 showed 312 closed claims related to any diagnosis (not just SEA) for hospitalists, with an average indemnity payment of $272,553 (the highest hospitalist-related payment was $1.4 million). The most common allegations related to paid claims were 1) “errors in diagnosis,” 2) “failure/delay in referral or consultation,” and 3) “failure to supervise/monitor case.” Although only three of the 312 claims were related to “diseases of the spinal cord,” that was exceeded in frequency only by “diabetes.”

I think these numbers from the malpractice insurance industry support my concern that SEA is a high-risk area, but it doesn’t really support my anecdotal experience that SEA is clearly hospitalists’ highest-risk area. Maybe SEA is only one of several high-risk areas. Nevertheless, I’m going to stick to my sensationalist guns to get your attention.

Why Is Epidural Abscess a High Risk?

There likely are several reasons SEA is a treacherous liability problem. It can lead to devastating permanent disabling neurologic deficits in people who were previously healthy, and if the medical care was substandard, then significant financial compensation seems appropriate.

Delays in diagnosis of SEA are common. It can be a very sneaky illness that in the early stages is very easy to confuse with less-serious causes of back pain or fever. Even though I think about this particular diagnosis all the time, just last year I had a patient who reported an increase in his usual back pain. I felt reassured that he had no neurologic deficit or fever, and took the time to explain why there was no reason to repeat the spine MRI that had been done about two weeks prior to admission. But he was insistent that he have another MRI, and after a day or two I finally agreed to order it, assuring him it would not explain the cause of his pain. But it did. He had a significant SEA and went to emergency surgery. I was stunned, and profoundly relieved that he had no neurologic sequelae.

One of the remarkable things I’ve seen in the cases I’ve reviewed is that even when there is clear cause for concern, there is too often no action taken. In a number of cases, the nurses’ note indicates increasing back pain, loss of ability to stand, urinary retention, and other alarming signs. Yet the doctors either never learn of these issues, or they choose to attribute them to other causes.

Even when the diagnosis of SEA is clearly established, it is all too common for doctors caring for the patient not to act on this information. In several cases I reviewed, a radiologist had documented reporting the diagnosis to the hospitalist (and in one case the neurosurgeon as well), yet nothing was done for 12 hours or more. It is hard to imagine that establishing this diagnosis doesn’t reliably lead to an emergent response, but it doesn’t. (In some cases, nonsurgical management may be an option, but in these malpractices cases, there was just a failure to act on the diagnosis with any sort of plan.)

Practice Management Perspective

I usually discuss hospitalist practice operations in this space—things like work schedules and compensation. But attending to risk management is one component of effective practice operations, so I thought I’d raise the topic here. Obviously, there is a lot more to hospitalist risk management than one diagnosis, but a column on the whole universe of risk management would probably serve no purpose other than as a sleep aid. I hope that by focusing solely on SEA, there is some chance that you’ll remember it, and you’ll make sure that you disprove my first two sentences.

Lowering your risk of a malpractice lawsuit is valuable and worth spending time on. But far more important is that by keeping the diagnosis in mind, and ensuring that you act emergently when there is cause for concern, you might save someone from the devastating consequences of this disease.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

John Nelson, MD: A New Hospitalist

Ben was just accepted to med school!!! Hopefully, more acceptances will be forthcoming. We are very proud of Ben for all his hard work. Another doctor in the family.

I was delighted to find the above message from an old friend in my inbox. It got me thinking: Will Ben become a hospitalist? Will he join his dad’s hospitalist group? Will his dad encourage him to pursue a hospitalist career or something else?

Early Hospitalist Practice

The author of that email was Ben’s dad, Chuck Wilson. Chuck is the reason I’m a hospitalist. He was a year ahead of me in residency, and while still a resident, he somehow connected with a really busy family physician in town who was looking for someone to manage his hospital patients. Not one to be bound by convention, Chuck agreed to what was at the time a nearly unheard-of arrangement. He finished residency, joined the staff of the community hospital across town from our residency, and began caring for the family physician’s hospital patients. Within days, he was fielding calls from other doctors asking him to do the same for them. Within weeks of arriving, he had begun accepting essentially all unassigned medical admissions from the ED. This was in the 1980s; Chuck was among the nation’s first real hospitalists.

I don’t think Chuck spent any time worrying about how his practice was so different from the traditional internists and family physicians in the community. He was confident he was providing a valuable service to his patients and the medical community. The rapid growth in his patient census was an indicator he was on to something, and soon he and I began talking. He was looking for a partner.

In November of my third year of residency, I decided I would put off my endocrinology fellowship for a year or two and join Chuck in his new practice. From our conversations, I anticipated that I would care for exactly the kinds of patients that filled nearly all of my time as a resident. I wouldn’t need to learn the new skills in ambulatory medicine, and wouldn’t need to make the long-term commitment expected to join a traditional primary-care practice. And I would earn a competitive compensation and have a flexible lifestyle. I soon realized that hospitalist practice provided me with all of these advantages, so more than two decades later, I still haven’t gotten around to completing the application for an endocrine fellowship.

A Loose Arrangement

For the first few years, Chuck and I didn’t bother to have any sort of legal agreement with each other. We shook hands and agreed to a “reap what you till” form of compensation, which meant we didn’t have to work exactly the same amount, and never had disagreements about how practice revenue was divided between us.

Because of Chuck’s influence, we had miniscule overhead expenses, most likely less than 10% of revenue. We each bought our own malpractice insurance, paid our biller a percent of collections, and rented a pager. That was about it for overhead.

We had no rigid scheduling algorithm, the only requirement being that at least one of us needed to be working every day. Both of us worked most weekdays, but we took time off whenever it suited us. Our scheduling meetings were usually held when we bumped into one another while rounding and went something like this:

“You OK if I take five days off starting tomorrow?”

“Sure. That’s fine.”

Meeting adjourned.

For years, we had no official name for our practice. This became a bigger issue when our group had grown to four doctors, so we defaulted to referring to the group by the first letter of the last name of each doctor, in order of tenure: The WNKL Group. A more formal name was to follow a few years later when the group was even larger, but I’ve taken delight in hearing that WNKL has persisted in some places and documents around the hospital years later, even though N, K, and L left the group long ago.

In the first few years, we never thought about developing clinical protocols or measuring our efficiency or clinical effectiveness. Chuck was confident that compared to the traditional primary-care model, we were providing higher-quality care at a lower cost. But I wasn’t so sure. After a few years, we began seeing hospital data showing that our cost per case tended to be lower, and what little data we could get regarding our quality of care suggested that it was about the same, and in some cases might be better.

A principal reason the practice has survived more than 25 years is that other than a small “tax” during their first 18 months (mainly to cover the cost of recruiting them), new doctors were regarded as equals in the business. Chuck and subsequent doctors never tried to gain an advantage over newer doctors by trying to claim a greater share of the practice’s revenue or decision-making authority.

Chuck is still in the same group he founded. In 2000, I was lured away by the chance to start a new group and live in a place that both my wife and I love. He and I have enjoyed watching our field grow up, and we take satisfaction in our roles in its evolution.

Lessons Learned

The hospitalist model of practice didn’t have a single inventor or place of origin, and anyone involved in starting a practice in the 1980s or before should be proud to have invented their practice when no blueprint existed. Creative thinking and openness to a new way of doing things were critical in developing the first hospitalist practices. They also are useful traits in trying to improve modern hospitalist practices or other segments of our healthcare system.

Like many new developments in medicine, the economic effects of our practice—lower hospital cost per case—became apparent, especially to Chuck, before data regarding quality surfaced. I wish we had gotten more serious early on about capturing whatever quality data might have been available—clearly less than what is available today—and those in new healthcare endeavors today should try to measure quality at the outset. Unlike the 1980s, the current marketplace will help ensure that happens.

Coda

There is one other really cool thing about Chuck’s email at the beginning of this column: those three exclamation points! Chuck is typically laconic and understated, and not given to such displays of emotion, but there are few things that generate more enthusiasm than a parent sharing news of a child’s success.

So, Ben, as you start med school next year, I wish you the best. You can be sure I’ll be asking for updates about your progress. The most important thing is that you find a life and career that engages you to do good work for others and provides satisfaction. And whatever you choose to do after med school, I know you’ll continue to make your parents proud.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Ben was just accepted to med school!!! Hopefully, more acceptances will be forthcoming. We are very proud of Ben for all his hard work. Another doctor in the family.

I was delighted to find the above message from an old friend in my inbox. It got me thinking: Will Ben become a hospitalist? Will he join his dad’s hospitalist group? Will his dad encourage him to pursue a hospitalist career or something else?

Early Hospitalist Practice

The author of that email was Ben’s dad, Chuck Wilson. Chuck is the reason I’m a hospitalist. He was a year ahead of me in residency, and while still a resident, he somehow connected with a really busy family physician in town who was looking for someone to manage his hospital patients. Not one to be bound by convention, Chuck agreed to what was at the time a nearly unheard-of arrangement. He finished residency, joined the staff of the community hospital across town from our residency, and began caring for the family physician’s hospital patients. Within days, he was fielding calls from other doctors asking him to do the same for them. Within weeks of arriving, he had begun accepting essentially all unassigned medical admissions from the ED. This was in the 1980s; Chuck was among the nation’s first real hospitalists.

I don’t think Chuck spent any time worrying about how his practice was so different from the traditional internists and family physicians in the community. He was confident he was providing a valuable service to his patients and the medical community. The rapid growth in his patient census was an indicator he was on to something, and soon he and I began talking. He was looking for a partner.

In November of my third year of residency, I decided I would put off my endocrinology fellowship for a year or two and join Chuck in his new practice. From our conversations, I anticipated that I would care for exactly the kinds of patients that filled nearly all of my time as a resident. I wouldn’t need to learn the new skills in ambulatory medicine, and wouldn’t need to make the long-term commitment expected to join a traditional primary-care practice. And I would earn a competitive compensation and have a flexible lifestyle. I soon realized that hospitalist practice provided me with all of these advantages, so more than two decades later, I still haven’t gotten around to completing the application for an endocrine fellowship.

A Loose Arrangement

For the first few years, Chuck and I didn’t bother to have any sort of legal agreement with each other. We shook hands and agreed to a “reap what you till” form of compensation, which meant we didn’t have to work exactly the same amount, and never had disagreements about how practice revenue was divided between us.

Because of Chuck’s influence, we had miniscule overhead expenses, most likely less than 10% of revenue. We each bought our own malpractice insurance, paid our biller a percent of collections, and rented a pager. That was about it for overhead.

We had no rigid scheduling algorithm, the only requirement being that at least one of us needed to be working every day. Both of us worked most weekdays, but we took time off whenever it suited us. Our scheduling meetings were usually held when we bumped into one another while rounding and went something like this:

“You OK if I take five days off starting tomorrow?”

“Sure. That’s fine.”

Meeting adjourned.

For years, we had no official name for our practice. This became a bigger issue when our group had grown to four doctors, so we defaulted to referring to the group by the first letter of the last name of each doctor, in order of tenure: The WNKL Group. A more formal name was to follow a few years later when the group was even larger, but I’ve taken delight in hearing that WNKL has persisted in some places and documents around the hospital years later, even though N, K, and L left the group long ago.

In the first few years, we never thought about developing clinical protocols or measuring our efficiency or clinical effectiveness. Chuck was confident that compared to the traditional primary-care model, we were providing higher-quality care at a lower cost. But I wasn’t so sure. After a few years, we began seeing hospital data showing that our cost per case tended to be lower, and what little data we could get regarding our quality of care suggested that it was about the same, and in some cases might be better.

A principal reason the practice has survived more than 25 years is that other than a small “tax” during their first 18 months (mainly to cover the cost of recruiting them), new doctors were regarded as equals in the business. Chuck and subsequent doctors never tried to gain an advantage over newer doctors by trying to claim a greater share of the practice’s revenue or decision-making authority.

Chuck is still in the same group he founded. In 2000, I was lured away by the chance to start a new group and live in a place that both my wife and I love. He and I have enjoyed watching our field grow up, and we take satisfaction in our roles in its evolution.

Lessons Learned

The hospitalist model of practice didn’t have a single inventor or place of origin, and anyone involved in starting a practice in the 1980s or before should be proud to have invented their practice when no blueprint existed. Creative thinking and openness to a new way of doing things were critical in developing the first hospitalist practices. They also are useful traits in trying to improve modern hospitalist practices or other segments of our healthcare system.

Like many new developments in medicine, the economic effects of our practice—lower hospital cost per case—became apparent, especially to Chuck, before data regarding quality surfaced. I wish we had gotten more serious early on about capturing whatever quality data might have been available—clearly less than what is available today—and those in new healthcare endeavors today should try to measure quality at the outset. Unlike the 1980s, the current marketplace will help ensure that happens.

Coda

There is one other really cool thing about Chuck’s email at the beginning of this column: those three exclamation points! Chuck is typically laconic and understated, and not given to such displays of emotion, but there are few things that generate more enthusiasm than a parent sharing news of a child’s success.

So, Ben, as you start med school next year, I wish you the best. You can be sure I’ll be asking for updates about your progress. The most important thing is that you find a life and career that engages you to do good work for others and provides satisfaction. And whatever you choose to do after med school, I know you’ll continue to make your parents proud.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Ben was just accepted to med school!!! Hopefully, more acceptances will be forthcoming. We are very proud of Ben for all his hard work. Another doctor in the family.

I was delighted to find the above message from an old friend in my inbox. It got me thinking: Will Ben become a hospitalist? Will he join his dad’s hospitalist group? Will his dad encourage him to pursue a hospitalist career or something else?

Early Hospitalist Practice

The author of that email was Ben’s dad, Chuck Wilson. Chuck is the reason I’m a hospitalist. He was a year ahead of me in residency, and while still a resident, he somehow connected with a really busy family physician in town who was looking for someone to manage his hospital patients. Not one to be bound by convention, Chuck agreed to what was at the time a nearly unheard-of arrangement. He finished residency, joined the staff of the community hospital across town from our residency, and began caring for the family physician’s hospital patients. Within days, he was fielding calls from other doctors asking him to do the same for them. Within weeks of arriving, he had begun accepting essentially all unassigned medical admissions from the ED. This was in the 1980s; Chuck was among the nation’s first real hospitalists.

I don’t think Chuck spent any time worrying about how his practice was so different from the traditional internists and family physicians in the community. He was confident he was providing a valuable service to his patients and the medical community. The rapid growth in his patient census was an indicator he was on to something, and soon he and I began talking. He was looking for a partner.

In November of my third year of residency, I decided I would put off my endocrinology fellowship for a year or two and join Chuck in his new practice. From our conversations, I anticipated that I would care for exactly the kinds of patients that filled nearly all of my time as a resident. I wouldn’t need to learn the new skills in ambulatory medicine, and wouldn’t need to make the long-term commitment expected to join a traditional primary-care practice. And I would earn a competitive compensation and have a flexible lifestyle. I soon realized that hospitalist practice provided me with all of these advantages, so more than two decades later, I still haven’t gotten around to completing the application for an endocrine fellowship.

A Loose Arrangement

For the first few years, Chuck and I didn’t bother to have any sort of legal agreement with each other. We shook hands and agreed to a “reap what you till” form of compensation, which meant we didn’t have to work exactly the same amount, and never had disagreements about how practice revenue was divided between us.

Because of Chuck’s influence, we had miniscule overhead expenses, most likely less than 10% of revenue. We each bought our own malpractice insurance, paid our biller a percent of collections, and rented a pager. That was about it for overhead.

We had no rigid scheduling algorithm, the only requirement being that at least one of us needed to be working every day. Both of us worked most weekdays, but we took time off whenever it suited us. Our scheduling meetings were usually held when we bumped into one another while rounding and went something like this:

“You OK if I take five days off starting tomorrow?”

“Sure. That’s fine.”

Meeting adjourned.

For years, we had no official name for our practice. This became a bigger issue when our group had grown to four doctors, so we defaulted to referring to the group by the first letter of the last name of each doctor, in order of tenure: The WNKL Group. A more formal name was to follow a few years later when the group was even larger, but I’ve taken delight in hearing that WNKL has persisted in some places and documents around the hospital years later, even though N, K, and L left the group long ago.

In the first few years, we never thought about developing clinical protocols or measuring our efficiency or clinical effectiveness. Chuck was confident that compared to the traditional primary-care model, we were providing higher-quality care at a lower cost. But I wasn’t so sure. After a few years, we began seeing hospital data showing that our cost per case tended to be lower, and what little data we could get regarding our quality of care suggested that it was about the same, and in some cases might be better.

A principal reason the practice has survived more than 25 years is that other than a small “tax” during their first 18 months (mainly to cover the cost of recruiting them), new doctors were regarded as equals in the business. Chuck and subsequent doctors never tried to gain an advantage over newer doctors by trying to claim a greater share of the practice’s revenue or decision-making authority.

Chuck is still in the same group he founded. In 2000, I was lured away by the chance to start a new group and live in a place that both my wife and I love. He and I have enjoyed watching our field grow up, and we take satisfaction in our roles in its evolution.

Lessons Learned

The hospitalist model of practice didn’t have a single inventor or place of origin, and anyone involved in starting a practice in the 1980s or before should be proud to have invented their practice when no blueprint existed. Creative thinking and openness to a new way of doing things were critical in developing the first hospitalist practices. They also are useful traits in trying to improve modern hospitalist practices or other segments of our healthcare system.

Like many new developments in medicine, the economic effects of our practice—lower hospital cost per case—became apparent, especially to Chuck, before data regarding quality surfaced. I wish we had gotten more serious early on about capturing whatever quality data might have been available—clearly less than what is available today—and those in new healthcare endeavors today should try to measure quality at the outset. Unlike the 1980s, the current marketplace will help ensure that happens.

Coda

There is one other really cool thing about Chuck’s email at the beginning of this column: those three exclamation points! Chuck is typically laconic and understated, and not given to such displays of emotion, but there are few things that generate more enthusiasm than a parent sharing news of a child’s success.

So, Ben, as you start med school next year, I wish you the best. You can be sure I’ll be asking for updates about your progress. The most important thing is that you find a life and career that engages you to do good work for others and provides satisfaction. And whatever you choose to do after med school, I know you’ll continue to make your parents proud.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

John Nelson: Peformance Key to Federal Value-Based Payment Modifier Plan

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

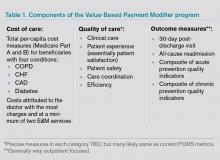

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

John Nelson: Learning CPT Coding and Documentation Tricky for Hospitalists

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

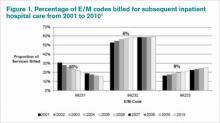

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.

To address tricky issues that come up only occasionally, several in our practice have compiled a “coding manual” by distilling guidance from our certified coders and compliance people on issues as they came up. Some issues would stump all of us, and we’d have to go to the Internet for help. All hospitalists are provided with a copy of the manual during orientation, and an electronic copy is available on the hospital’s Intranet. Topics addressed in the manual include things like how to bill the first inpatient day when a patient has changed from observation status, how to bill initial consult visits for various payors (an issue since Medicare eliminated consult codes a few years ago), how to bill when a patient is seen and discharged from the ED, etc.

Lastly, I suggest someone in your group talk with your hospital’s compliance department about its own coding and billing compliance plan. This could lead to ideas or help develop a compliance plan for your group.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.

To address tricky issues that come up only occasionally, several in our practice have compiled a “coding manual” by distilling guidance from our certified coders and compliance people on issues as they came up. Some issues would stump all of us, and we’d have to go to the Internet for help. All hospitalists are provided with a copy of the manual during orientation, and an electronic copy is available on the hospital’s Intranet. Topics addressed in the manual include things like how to bill the first inpatient day when a patient has changed from observation status, how to bill initial consult visits for various payors (an issue since Medicare eliminated consult codes a few years ago), how to bill when a patient is seen and discharged from the ED, etc.

Lastly, I suggest someone in your group talk with your hospital’s compliance department about its own coding and billing compliance plan. This could lead to ideas or help develop a compliance plan for your group.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.