User login

Renal Function Caveats

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

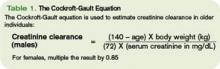

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Quartarolo JM, Thoelke M, Schafers SJ. Reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: effect on physician recognition of chronic kidney disease and prescribing practices for elderly hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):74-78.

- Frye RF, Matzke GR. Drug therapy individualization for patients with renal insufficiency. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:939-952.

- Healthy Aging At-A-Glance 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/healthy_aging.pdf. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Guay D, et al. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:79-89.

- Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917-1924.

- K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487-1496.

- Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa : American College of Physicians; 2007.

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Quartarolo JM, Thoelke M, Schafers SJ. Reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: effect on physician recognition of chronic kidney disease and prescribing practices for elderly hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):74-78.

- Frye RF, Matzke GR. Drug therapy individualization for patients with renal insufficiency. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:939-952.

- Healthy Aging At-A-Glance 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/healthy_aging.pdf. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Guay D, et al. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:79-89.

- Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917-1924.

- K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487-1496.

- Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa : American College of Physicians; 2007.

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Quartarolo JM, Thoelke M, Schafers SJ. Reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: effect on physician recognition of chronic kidney disease and prescribing practices for elderly hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):74-78.

- Frye RF, Matzke GR. Drug therapy individualization for patients with renal insufficiency. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:939-952.

- Healthy Aging At-A-Glance 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/healthy_aging.pdf. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Guay D, et al. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:79-89.

- Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917-1924.

- K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487-1496.

- Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa : American College of Physicians; 2007.

Avoid Pancreatitis Risk

Drugs are an often-overlooked cause of pancreatitis in hospitalized patients.1,2 Knowing which drugs are associated with acute pancreatic inflammation can help the hospitalist consider specific drugs as the cause within their differential diagnosis.

The two most common causes of acute pancreatitis are biliary disease (30%-60%) and chronic alcohol use (15%-30%). Drug-induced pancreatitis (DIP) has occurred with more than 100 prescribed medications.3,4

Most cases of acute pancreatitis are reversible and resolve on their own within three to seven days after treatment begins. A small number of patients develop severe complications, and their mortality rate nears 30%. Symptoms may last a few days and can include mild to severe epigastric pain that can radiate to the back, chest, flank, or lower abdomen.

Other symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal tenderness, jaundice, or hypotension. Serum amylase and lipase levels usually rise to three times the upper limit of normal. Use of computerized tomography (CT) or ultrasound can help the diagnosis.

The mechanism of DIP is not known, but is thought to be predominantly due to an idiosyncratic reaction, and for a few agents/classes, to intrinsic drug toxicity.5 The incidence of DIP is approximately 1.4%-5%. Not knowing the exact number of prescriptions for each medication and the cases of pancreatitis from each impedes the determination of incidence.

Most data on DIP are from case reports or reviews of compiled cases. The validity and severity of DIP is unknown mostly because cases are underreported to MedWatch. Reasons for underreporting include:

- Low index of suspicion for DIP compared with drug- induced hepatotoxicity;

- Milder cases due to missed lower enzyme levels (not routinely ascertained in a metabolic panel);

- Missed latency of exposure; and

- Erroneous classification as alcoholic or biliary disease by default.

Drug-induced pancreatitis is more common in patients who have inflammatory bowel disease, AIDS, cancer, or gastrointestinal disease. It is also common in those who are geriatric, HIV positive, or who are on immunomodulating agents.6

An early compilation of DIP reports was published by Lankisch, et al. This was a retrospective evaluation that excluded all other pancreatitis etiologies (e.g., post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), post-traumatic, post-operative, viral), except drugs. Out of 1,613 patients with acute pancreatitis, there were 22 cases of DIP due to the following agents: azathioprine (n=6), mesalamine/sulfasalazine (n=5) didanosine (ddI, n=4), estrogens (n=3), furosemide (n=2), hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ, n=1), and rifampicin (n=1). Rechallenge was not attempted for ethical reasons. The mean hospital stay was 25.5 days (range two to 78 days), with an incidence of 1.2%. Two patients died (from AIDS and tuberculosis). The authors noted that other studies show a high fatality rate from azathioprine, ddI, furosemide, and HCTZ.

Additionally, Triveldi, et al., evaluated cases reported in the literature or unpublished cases from 1966 through 2004. They then classified the drugs into one of three categories based on strength of evidence of DIP association.

Class I included medications causing more than 20 reported cases with at least one case following rechallenge. Class II were medications causing more than 10 but fewer than 20 reported cases with/without a positive rechallenge, and Class III were all medications in 10 or fewer cases or unpublished reports (FDA or pharmaceutical company records). Following are some of the most common reports from drugs available in the U.S.:

- Class I: ddI (n=883), asparaginase (n=177), azathioprine (n=86), valproic acid (n=80), pentavalent antimonials (parenterals to treat leishmaniasis, n=80), pentamidine (n=79), mercaptopurine (n=69), mesalamine (n=59), estrogens (n=42), opiates (n=42), tetracycline (n=34), cytarabine (n=26), steroids (n=25), sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SMZ-TMP, n=24), sulfasalazine (n=23), furosemide (n=21), sulindac (n=21);

- Class II: rifampin, lamivudine, octreotide, carbamazepine, acetaminophen, interferon alfa-2b, enalapril, HCTZ, cisplatin, erythromycin; and

- Class III (numerous agents, including the following classes): quinolones, macrolides, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), statins, and others.

Most recently Badalov, et al., evaluated cases from Medline (through July 1, 2006) and classified them based on levels of evidence. These levels were:

- Definite (imaging study or autopsy confirmed diagnosis);

- Probable (typical symptoms present and threefold increase in amylase and/or lipase); or

- Possible (all others, not included in the final analysis).

Cases were further subclassified into four classes:

- Class Ia (1 or more cases with positive rechallenge, excluding all other causes): codeine, conjugated estrogens, enalapril, isoniazid, metronidazole, mesalamine, pravastatin (other statins), procainamide, simvastatin, sulindac, sulfa drugs, tetracycline, and valproic acid;

- Class Ib (1 or more cases with positive rechallenge, not excluding all other causes): amiodarone, azathioprine, clomiphene, cytosine arabinoside, dapsone, dexamethasone (other steroids), estrogens, furosemide, ifosfamide, lamivudine, losartan, 6-MP, methimazole, methyldopa, nelfinavir, omeprazole, pentamidine, SMZ-TMP, and trans-retinoic acid (not topical);

- Class II (four or more cases, consistent latency in 75% of cases): acetaminophen, clozapine, ddI, erythromycin, l-asparaginase/peg-asparaginase, pentamidine, propofol, and tamoxifen;

- Class III (two or more cases, no consistent latency, no rechallenge): alendronate, captopril, carbamazepine, ceftriaxone, HCTZ, interferon, lisinopril, metformin, mirtazapine, naproxen, and others; and

- Class IV (one case, no other class, without rechallenge): too numerous.

Additionally, the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee reported on the top 12 DIP-associated medications (n=414 reports implicating 695 drugs). The most commonly reported drugs included azathioprine, ddI, valproate, stavudine, simvastatin, clozapine, lamivudine, ezetimibe, prednisolone, olanzapine, celecoxib and 6-MP, which are listed in each medication’s Australian product information.

The following drugs/classes have been implicated in causing DIP:

- AIDS therapies: ddI, pentamidine;

- Antimicrobials: metronidazole, sulfonamides, tetracyclines;

- Diuretics: furosemide, HCTZ;

- Anti-inflammatories: mesalamine, salicylates, sulindac, sulfasalazine;

- Immunosuppressives: asparaginase, azathioprine, mercaptopurine; and

- Neuropsychiatric agents: valproic acid.

The American Gastroenterologic Association Institute has developed a guide for managing acute pancreatitis. Additionally, they note that when assessing DIP, consider prescription, over-the-counter, and herbal products, too.7 Pancreatitis can occur with certain drugs or medication classes, some more often than others.

Consider DIP in the differential diagnosis of patients who present with or develop epigastric pain. Question all patients with acute pancreatitis about their medication use as a possible cause for the disease. Assessment of amylase/lipase will aid in the diagnosis. To prevent further compromise in cases where DIP is suspected, hold the offending agent (and substitute if possible) to decrease further episodes. TH

Michele B Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Lankisch PG, Dröge M, Gottesleben F. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis: incidence and severity. Gut. 1995 Oct;37(4):565-567.

- Eltookhy A, Pearson NL. Drug-induced pancreatitis. Can Pharm J. 2006;139(6):58-60.

- Trivedi CD, Pitchumoni CS. Drug-induced pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005 Sept;39(8):709-716.

- Badalov N, Baradarian R, Iswara K, et al. Drug-induced pancreatitis: an evidence-based review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Jun;5(6):648-661.

- Vege SS, Chari ST. Etiology of acute pancreatitis. In: UpToDate, Rose, BD (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, Mass., 2007.

- Skirvin A. Drug-induced pancreatitis. Aust Adv Drug Reactions Bull. 2006 Dec;25(6):22.

- American Gastroenterological Association Institute Medical Position Statement on Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1998 Sep;115(3):763-764.

Drugs are an often-overlooked cause of pancreatitis in hospitalized patients.1,2 Knowing which drugs are associated with acute pancreatic inflammation can help the hospitalist consider specific drugs as the cause within their differential diagnosis.

The two most common causes of acute pancreatitis are biliary disease (30%-60%) and chronic alcohol use (15%-30%). Drug-induced pancreatitis (DIP) has occurred with more than 100 prescribed medications.3,4

Most cases of acute pancreatitis are reversible and resolve on their own within three to seven days after treatment begins. A small number of patients develop severe complications, and their mortality rate nears 30%. Symptoms may last a few days and can include mild to severe epigastric pain that can radiate to the back, chest, flank, or lower abdomen.

Other symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal tenderness, jaundice, or hypotension. Serum amylase and lipase levels usually rise to three times the upper limit of normal. Use of computerized tomography (CT) or ultrasound can help the diagnosis.

The mechanism of DIP is not known, but is thought to be predominantly due to an idiosyncratic reaction, and for a few agents/classes, to intrinsic drug toxicity.5 The incidence of DIP is approximately 1.4%-5%. Not knowing the exact number of prescriptions for each medication and the cases of pancreatitis from each impedes the determination of incidence.

Most data on DIP are from case reports or reviews of compiled cases. The validity and severity of DIP is unknown mostly because cases are underreported to MedWatch. Reasons for underreporting include:

- Low index of suspicion for DIP compared with drug- induced hepatotoxicity;

- Milder cases due to missed lower enzyme levels (not routinely ascertained in a metabolic panel);

- Missed latency of exposure; and

- Erroneous classification as alcoholic or biliary disease by default.

Drug-induced pancreatitis is more common in patients who have inflammatory bowel disease, AIDS, cancer, or gastrointestinal disease. It is also common in those who are geriatric, HIV positive, or who are on immunomodulating agents.6

An early compilation of DIP reports was published by Lankisch, et al. This was a retrospective evaluation that excluded all other pancreatitis etiologies (e.g., post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), post-traumatic, post-operative, viral), except drugs. Out of 1,613 patients with acute pancreatitis, there were 22 cases of DIP due to the following agents: azathioprine (n=6), mesalamine/sulfasalazine (n=5) didanosine (ddI, n=4), estrogens (n=3), furosemide (n=2), hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ, n=1), and rifampicin (n=1). Rechallenge was not attempted for ethical reasons. The mean hospital stay was 25.5 days (range two to 78 days), with an incidence of 1.2%. Two patients died (from AIDS and tuberculosis). The authors noted that other studies show a high fatality rate from azathioprine, ddI, furosemide, and HCTZ.

Additionally, Triveldi, et al., evaluated cases reported in the literature or unpublished cases from 1966 through 2004. They then classified the drugs into one of three categories based on strength of evidence of DIP association.

Class I included medications causing more than 20 reported cases with at least one case following rechallenge. Class II were medications causing more than 10 but fewer than 20 reported cases with/without a positive rechallenge, and Class III were all medications in 10 or fewer cases or unpublished reports (FDA or pharmaceutical company records). Following are some of the most common reports from drugs available in the U.S.:

- Class I: ddI (n=883), asparaginase (n=177), azathioprine (n=86), valproic acid (n=80), pentavalent antimonials (parenterals to treat leishmaniasis, n=80), pentamidine (n=79), mercaptopurine (n=69), mesalamine (n=59), estrogens (n=42), opiates (n=42), tetracycline (n=34), cytarabine (n=26), steroids (n=25), sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SMZ-TMP, n=24), sulfasalazine (n=23), furosemide (n=21), sulindac (n=21);

- Class II: rifampin, lamivudine, octreotide, carbamazepine, acetaminophen, interferon alfa-2b, enalapril, HCTZ, cisplatin, erythromycin; and

- Class III (numerous agents, including the following classes): quinolones, macrolides, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), statins, and others.

Most recently Badalov, et al., evaluated cases from Medline (through July 1, 2006) and classified them based on levels of evidence. These levels were:

- Definite (imaging study or autopsy confirmed diagnosis);

- Probable (typical symptoms present and threefold increase in amylase and/or lipase); or

- Possible (all others, not included in the final analysis).

Cases were further subclassified into four classes:

- Class Ia (1 or more cases with positive rechallenge, excluding all other causes): codeine, conjugated estrogens, enalapril, isoniazid, metronidazole, mesalamine, pravastatin (other statins), procainamide, simvastatin, sulindac, sulfa drugs, tetracycline, and valproic acid;

- Class Ib (1 or more cases with positive rechallenge, not excluding all other causes): amiodarone, azathioprine, clomiphene, cytosine arabinoside, dapsone, dexamethasone (other steroids), estrogens, furosemide, ifosfamide, lamivudine, losartan, 6-MP, methimazole, methyldopa, nelfinavir, omeprazole, pentamidine, SMZ-TMP, and trans-retinoic acid (not topical);

- Class II (four or more cases, consistent latency in 75% of cases): acetaminophen, clozapine, ddI, erythromycin, l-asparaginase/peg-asparaginase, pentamidine, propofol, and tamoxifen;

- Class III (two or more cases, no consistent latency, no rechallenge): alendronate, captopril, carbamazepine, ceftriaxone, HCTZ, interferon, lisinopril, metformin, mirtazapine, naproxen, and others; and

- Class IV (one case, no other class, without rechallenge): too numerous.

Additionally, the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee reported on the top 12 DIP-associated medications (n=414 reports implicating 695 drugs). The most commonly reported drugs included azathioprine, ddI, valproate, stavudine, simvastatin, clozapine, lamivudine, ezetimibe, prednisolone, olanzapine, celecoxib and 6-MP, which are listed in each medication’s Australian product information.

The following drugs/classes have been implicated in causing DIP:

- AIDS therapies: ddI, pentamidine;

- Antimicrobials: metronidazole, sulfonamides, tetracyclines;

- Diuretics: furosemide, HCTZ;

- Anti-inflammatories: mesalamine, salicylates, sulindac, sulfasalazine;

- Immunosuppressives: asparaginase, azathioprine, mercaptopurine; and

- Neuropsychiatric agents: valproic acid.

The American Gastroenterologic Association Institute has developed a guide for managing acute pancreatitis. Additionally, they note that when assessing DIP, consider prescription, over-the-counter, and herbal products, too.7 Pancreatitis can occur with certain drugs or medication classes, some more often than others.

Consider DIP in the differential diagnosis of patients who present with or develop epigastric pain. Question all patients with acute pancreatitis about their medication use as a possible cause for the disease. Assessment of amylase/lipase will aid in the diagnosis. To prevent further compromise in cases where DIP is suspected, hold the offending agent (and substitute if possible) to decrease further episodes. TH

Michele B Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Lankisch PG, Dröge M, Gottesleben F. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis: incidence and severity. Gut. 1995 Oct;37(4):565-567.

- Eltookhy A, Pearson NL. Drug-induced pancreatitis. Can Pharm J. 2006;139(6):58-60.

- Trivedi CD, Pitchumoni CS. Drug-induced pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005 Sept;39(8):709-716.

- Badalov N, Baradarian R, Iswara K, et al. Drug-induced pancreatitis: an evidence-based review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Jun;5(6):648-661.

- Vege SS, Chari ST. Etiology of acute pancreatitis. In: UpToDate, Rose, BD (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, Mass., 2007.

- Skirvin A. Drug-induced pancreatitis. Aust Adv Drug Reactions Bull. 2006 Dec;25(6):22.

- American Gastroenterological Association Institute Medical Position Statement on Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1998 Sep;115(3):763-764.

Drugs are an often-overlooked cause of pancreatitis in hospitalized patients.1,2 Knowing which drugs are associated with acute pancreatic inflammation can help the hospitalist consider specific drugs as the cause within their differential diagnosis.

The two most common causes of acute pancreatitis are biliary disease (30%-60%) and chronic alcohol use (15%-30%). Drug-induced pancreatitis (DIP) has occurred with more than 100 prescribed medications.3,4

Most cases of acute pancreatitis are reversible and resolve on their own within three to seven days after treatment begins. A small number of patients develop severe complications, and their mortality rate nears 30%. Symptoms may last a few days and can include mild to severe epigastric pain that can radiate to the back, chest, flank, or lower abdomen.

Other symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal tenderness, jaundice, or hypotension. Serum amylase and lipase levels usually rise to three times the upper limit of normal. Use of computerized tomography (CT) or ultrasound can help the diagnosis.

The mechanism of DIP is not known, but is thought to be predominantly due to an idiosyncratic reaction, and for a few agents/classes, to intrinsic drug toxicity.5 The incidence of DIP is approximately 1.4%-5%. Not knowing the exact number of prescriptions for each medication and the cases of pancreatitis from each impedes the determination of incidence.

Most data on DIP are from case reports or reviews of compiled cases. The validity and severity of DIP is unknown mostly because cases are underreported to MedWatch. Reasons for underreporting include:

- Low index of suspicion for DIP compared with drug- induced hepatotoxicity;

- Milder cases due to missed lower enzyme levels (not routinely ascertained in a metabolic panel);

- Missed latency of exposure; and

- Erroneous classification as alcoholic or biliary disease by default.

Drug-induced pancreatitis is more common in patients who have inflammatory bowel disease, AIDS, cancer, or gastrointestinal disease. It is also common in those who are geriatric, HIV positive, or who are on immunomodulating agents.6

An early compilation of DIP reports was published by Lankisch, et al. This was a retrospective evaluation that excluded all other pancreatitis etiologies (e.g., post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), post-traumatic, post-operative, viral), except drugs. Out of 1,613 patients with acute pancreatitis, there were 22 cases of DIP due to the following agents: azathioprine (n=6), mesalamine/sulfasalazine (n=5) didanosine (ddI, n=4), estrogens (n=3), furosemide (n=2), hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ, n=1), and rifampicin (n=1). Rechallenge was not attempted for ethical reasons. The mean hospital stay was 25.5 days (range two to 78 days), with an incidence of 1.2%. Two patients died (from AIDS and tuberculosis). The authors noted that other studies show a high fatality rate from azathioprine, ddI, furosemide, and HCTZ.

Additionally, Triveldi, et al., evaluated cases reported in the literature or unpublished cases from 1966 through 2004. They then classified the drugs into one of three categories based on strength of evidence of DIP association.

Class I included medications causing more than 20 reported cases with at least one case following rechallenge. Class II were medications causing more than 10 but fewer than 20 reported cases with/without a positive rechallenge, and Class III were all medications in 10 or fewer cases or unpublished reports (FDA or pharmaceutical company records). Following are some of the most common reports from drugs available in the U.S.:

- Class I: ddI (n=883), asparaginase (n=177), azathioprine (n=86), valproic acid (n=80), pentavalent antimonials (parenterals to treat leishmaniasis, n=80), pentamidine (n=79), mercaptopurine (n=69), mesalamine (n=59), estrogens (n=42), opiates (n=42), tetracycline (n=34), cytarabine (n=26), steroids (n=25), sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SMZ-TMP, n=24), sulfasalazine (n=23), furosemide (n=21), sulindac (n=21);

- Class II: rifampin, lamivudine, octreotide, carbamazepine, acetaminophen, interferon alfa-2b, enalapril, HCTZ, cisplatin, erythromycin; and

- Class III (numerous agents, including the following classes): quinolones, macrolides, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), statins, and others.

Most recently Badalov, et al., evaluated cases from Medline (through July 1, 2006) and classified them based on levels of evidence. These levels were:

- Definite (imaging study or autopsy confirmed diagnosis);

- Probable (typical symptoms present and threefold increase in amylase and/or lipase); or

- Possible (all others, not included in the final analysis).

Cases were further subclassified into four classes:

- Class Ia (1 or more cases with positive rechallenge, excluding all other causes): codeine, conjugated estrogens, enalapril, isoniazid, metronidazole, mesalamine, pravastatin (other statins), procainamide, simvastatin, sulindac, sulfa drugs, tetracycline, and valproic acid;

- Class Ib (1 or more cases with positive rechallenge, not excluding all other causes): amiodarone, azathioprine, clomiphene, cytosine arabinoside, dapsone, dexamethasone (other steroids), estrogens, furosemide, ifosfamide, lamivudine, losartan, 6-MP, methimazole, methyldopa, nelfinavir, omeprazole, pentamidine, SMZ-TMP, and trans-retinoic acid (not topical);

- Class II (four or more cases, consistent latency in 75% of cases): acetaminophen, clozapine, ddI, erythromycin, l-asparaginase/peg-asparaginase, pentamidine, propofol, and tamoxifen;

- Class III (two or more cases, no consistent latency, no rechallenge): alendronate, captopril, carbamazepine, ceftriaxone, HCTZ, interferon, lisinopril, metformin, mirtazapine, naproxen, and others; and

- Class IV (one case, no other class, without rechallenge): too numerous.

Additionally, the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee reported on the top 12 DIP-associated medications (n=414 reports implicating 695 drugs). The most commonly reported drugs included azathioprine, ddI, valproate, stavudine, simvastatin, clozapine, lamivudine, ezetimibe, prednisolone, olanzapine, celecoxib and 6-MP, which are listed in each medication’s Australian product information.

The following drugs/classes have been implicated in causing DIP:

- AIDS therapies: ddI, pentamidine;

- Antimicrobials: metronidazole, sulfonamides, tetracyclines;

- Diuretics: furosemide, HCTZ;

- Anti-inflammatories: mesalamine, salicylates, sulindac, sulfasalazine;

- Immunosuppressives: asparaginase, azathioprine, mercaptopurine; and

- Neuropsychiatric agents: valproic acid.

The American Gastroenterologic Association Institute has developed a guide for managing acute pancreatitis. Additionally, they note that when assessing DIP, consider prescription, over-the-counter, and herbal products, too.7 Pancreatitis can occur with certain drugs or medication classes, some more often than others.

Consider DIP in the differential diagnosis of patients who present with or develop epigastric pain. Question all patients with acute pancreatitis about their medication use as a possible cause for the disease. Assessment of amylase/lipase will aid in the diagnosis. To prevent further compromise in cases where DIP is suspected, hold the offending agent (and substitute if possible) to decrease further episodes. TH

Michele B Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Lankisch PG, Dröge M, Gottesleben F. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis: incidence and severity. Gut. 1995 Oct;37(4):565-567.

- Eltookhy A, Pearson NL. Drug-induced pancreatitis. Can Pharm J. 2006;139(6):58-60.

- Trivedi CD, Pitchumoni CS. Drug-induced pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005 Sept;39(8):709-716.

- Badalov N, Baradarian R, Iswara K, et al. Drug-induced pancreatitis: an evidence-based review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Jun;5(6):648-661.

- Vege SS, Chari ST. Etiology of acute pancreatitis. In: UpToDate, Rose, BD (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, Mass., 2007.

- Skirvin A. Drug-induced pancreatitis. Aust Adv Drug Reactions Bull. 2006 Dec;25(6):22.

- American Gastroenterological Association Institute Medical Position Statement on Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1998 Sep;115(3):763-764.

Manage Cancer Drugs

Human epidural growth factor receptor (HER1/EGFR) signaling pathways are crucial in regulating cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.

HER1/EGFR is a protein tyrosine kinase with therapeutic applications in cancer treatment.1 Two approved drugs categories target HER1/EGFR: anti-HER1/EGFR monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and HER1/EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). The drugs have different complex actions, some leading to disruption of cellular processes at the level of cell division, apoptosis, and angiogenesis.

Approximately 30% to 100% of solid tumors express HER1/EGFR on the tumor surface, while some overexpress it. This is thought to lead to tumor growth.2,3 Increased HER1/EGFR activity has been associated with poor survival in some cancers.

The Agents

A number of HER1/EGFR TKIs are FDA approved and administered orally, including erlotinib (Tarceva), gefitinib (Iressa), imatinib (Gleevec), lapatinib (Tykerb), sorafenib (Nexavar), and sunitinib (Sutent).4-6

Cetuximab (Erbitux) and panitumumab (Vectibix) are approved mAbs given intravenously. Both categories treat different cancers including advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, renal cell carcinoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and others. The HER1/EGFR targeted agents have a more favorable side effect profile compared with more traditional chemotherapeutic agents with primarily dermatologic toxicities and limited hematopoietic effects. Because many patients are being treated with these oral anti-cancer agents, it is important to remain aware of the agents, their toxicities, and their management.

Adverse Effects

The most common adverse effect associated with HER1/EGFR inhibitors is a dose-dependent, folliculitis-like rash.

The rash affects up to two-thirds of treated patients within the first two weeks of therapy. It is usually on the face, neck, and upper torso and is characterized by inter- and intrafollicular papulopustules of mild-to-moderate severity. The rash develops in three phases: sensory disturbance with erythema and edema (weeks zero to one), papulopustular flare (weeks one to three), crusting (weeks three to five), and erythematotelangiectasias (weeks five to eight).

Dry skin and erythema may remain in the areas after resolution. The skin rash appears to be dose-dependent. The mechanism of the rash is not precisely known. However, HER1/EGFR is expressed by normal keratinocytes and skin fibroblasts, along the outer sheath of the hair follicle, and in many epidermal processes, which probably contributes.

Hair effects occur within two to three months of starting treatment. Scalp hair becomes more brittle, fine, and curly. Frontal alopecia gradually develops, and patients experience progressive trichomegaly of the eyelashes and hypertrichosis of the face. Paronychial inflammation can occur on the fingernails or toenails and be so painful it prevents patients from wearing shoes. Its origin is unknown, and it disappears after discontinuation of the drug. Xerosis is also common, which can be treated with topically applied 5% to 10% urea emollient.

Rash as a Marker

There appears to be some evidence of a relationship between HER1/EGFR efficacy and associated rash severity. There have been at least 19 trials and additional compassionate use centers that have found the relationship of a positive correlation between rash and response/survival.

For example, in a Phase II study in 57 patients with non-small cell lung cancer, those with grade zero rashes had a median survival of 1.5 months, those with rash grade one had a median survival of 8.5 months, and those with rash grades two or three had a 19.6 month survival. In another study with erlotinib monotherapy, patients with a skin rash had significantly greater survival rates (approximately 80%) than those without skin rashes. In trials of cetuximab in patients with different cancer types, those who developed a rash lived substantially longer than those who did not.

There are also data supporting gefitinib and cetuximab. Many of the studies note a poorer clinical outcome in those patients without rash. These findings suggest that lack of a rash after a specific period of therapy may be an early indicator of treatment failure and the need for another treatment.

Rash Treatment

While receiving treatment with these agents, patients should be advised to moisturize dry body areas twice daily with a thick alcohol-free emollient. Patients should minimize sun exposure and wear a broad-spectrum sunscreen (SPF 15). Zinc oxide or titanium dioxide is preferred over chemical sunscreens. The following treatment interventions are suggested:

- Mild toxicity: topical hydrocortisone 1% to 2.5% cream or clindamycin 1% gel. The HER1/EGFR dose should not be adjusted;

- Moderate toxicity: topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream, clindamycin 1% gel, or pimecrolimus 1% cream (Elidel) with doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day or minocycline 100mg orally twice a day. The HER1/EGFR dose should not be adjusted; or

- Severe toxicity: topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream, clindamycin 1% gel, or pimecrolimus 1% cream (Elidel) with doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day or minocycline 100mg orally twice a day. Also add methylprednisolone dose pack.

Reduce the HER1/EGFR dose, if after two to four weeks the toxicities have not sufficiently abated, then the HER1/EGFR therapy should be interrupted. Once the skin reactions have resolved or diminished in severity, the HER1/EGFR dose may typically be restarted or re-escalated.

Results of a recent double-blind, placebo-controlled study suggest tetracycline may be effective in decreasing EGFR-associated rash severity and improving some quality-of-life parameters (e.g., irritation, burning, stinging).7 Remaining alert to these reactions in patients receiving HER1/EGFRs is important for monitoring treatment and managing patients. TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Castillo L, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Fischel JL, et al. Pharmacologic background of EGFR targeting. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(7):1007-1012.

- Robert C, Soria JC, Spatz A et al. Cutaneous side effects of kinase inhibitors and blocking antibodies. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(7):491-500.

- Peréz-Soler R, Saltz L. Cutaneous adverse effects with HER1/EGFR-targeted agents: Is there a silver lining? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5235-5246.

- Seiverling EV, Fernandez EM, Adams D. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor associated skin eruption. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(4)368-369. Available at http://findarticles.com/p/articles/ mi_m0PDG/ is_4_5/ai_n16361317Accessed August 7, 2007

- Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. www.oncolink.com/treatment/article.cfm?c=12&s=90&id=268. Accessed August 7, 2007

- Lynch TJ, Kim ES, Eaby B, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated toxicities: An evolving paradigm in clinical management. Oncologist 2007;12(5):610-621.

- Jatoi A, Rowland K, Sloan JA, et al. J Clin Oncol 2007; ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. Vol. 25(18S);June 20:LBA9006.

Human epidural growth factor receptor (HER1/EGFR) signaling pathways are crucial in regulating cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.

HER1/EGFR is a protein tyrosine kinase with therapeutic applications in cancer treatment.1 Two approved drugs categories target HER1/EGFR: anti-HER1/EGFR monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and HER1/EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). The drugs have different complex actions, some leading to disruption of cellular processes at the level of cell division, apoptosis, and angiogenesis.

Approximately 30% to 100% of solid tumors express HER1/EGFR on the tumor surface, while some overexpress it. This is thought to lead to tumor growth.2,3 Increased HER1/EGFR activity has been associated with poor survival in some cancers.

The Agents

A number of HER1/EGFR TKIs are FDA approved and administered orally, including erlotinib (Tarceva), gefitinib (Iressa), imatinib (Gleevec), lapatinib (Tykerb), sorafenib (Nexavar), and sunitinib (Sutent).4-6

Cetuximab (Erbitux) and panitumumab (Vectibix) are approved mAbs given intravenously. Both categories treat different cancers including advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, renal cell carcinoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and others. The HER1/EGFR targeted agents have a more favorable side effect profile compared with more traditional chemotherapeutic agents with primarily dermatologic toxicities and limited hematopoietic effects. Because many patients are being treated with these oral anti-cancer agents, it is important to remain aware of the agents, their toxicities, and their management.

Adverse Effects

The most common adverse effect associated with HER1/EGFR inhibitors is a dose-dependent, folliculitis-like rash.

The rash affects up to two-thirds of treated patients within the first two weeks of therapy. It is usually on the face, neck, and upper torso and is characterized by inter- and intrafollicular papulopustules of mild-to-moderate severity. The rash develops in three phases: sensory disturbance with erythema and edema (weeks zero to one), papulopustular flare (weeks one to three), crusting (weeks three to five), and erythematotelangiectasias (weeks five to eight).

Dry skin and erythema may remain in the areas after resolution. The skin rash appears to be dose-dependent. The mechanism of the rash is not precisely known. However, HER1/EGFR is expressed by normal keratinocytes and skin fibroblasts, along the outer sheath of the hair follicle, and in many epidermal processes, which probably contributes.

Hair effects occur within two to three months of starting treatment. Scalp hair becomes more brittle, fine, and curly. Frontal alopecia gradually develops, and patients experience progressive trichomegaly of the eyelashes and hypertrichosis of the face. Paronychial inflammation can occur on the fingernails or toenails and be so painful it prevents patients from wearing shoes. Its origin is unknown, and it disappears after discontinuation of the drug. Xerosis is also common, which can be treated with topically applied 5% to 10% urea emollient.

Rash as a Marker

There appears to be some evidence of a relationship between HER1/EGFR efficacy and associated rash severity. There have been at least 19 trials and additional compassionate use centers that have found the relationship of a positive correlation between rash and response/survival.

For example, in a Phase II study in 57 patients with non-small cell lung cancer, those with grade zero rashes had a median survival of 1.5 months, those with rash grade one had a median survival of 8.5 months, and those with rash grades two or three had a 19.6 month survival. In another study with erlotinib monotherapy, patients with a skin rash had significantly greater survival rates (approximately 80%) than those without skin rashes. In trials of cetuximab in patients with different cancer types, those who developed a rash lived substantially longer than those who did not.

There are also data supporting gefitinib and cetuximab. Many of the studies note a poorer clinical outcome in those patients without rash. These findings suggest that lack of a rash after a specific period of therapy may be an early indicator of treatment failure and the need for another treatment.

Rash Treatment

While receiving treatment with these agents, patients should be advised to moisturize dry body areas twice daily with a thick alcohol-free emollient. Patients should minimize sun exposure and wear a broad-spectrum sunscreen (SPF 15). Zinc oxide or titanium dioxide is preferred over chemical sunscreens. The following treatment interventions are suggested:

- Mild toxicity: topical hydrocortisone 1% to 2.5% cream or clindamycin 1% gel. The HER1/EGFR dose should not be adjusted;

- Moderate toxicity: topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream, clindamycin 1% gel, or pimecrolimus 1% cream (Elidel) with doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day or minocycline 100mg orally twice a day. The HER1/EGFR dose should not be adjusted; or

- Severe toxicity: topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream, clindamycin 1% gel, or pimecrolimus 1% cream (Elidel) with doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day or minocycline 100mg orally twice a day. Also add methylprednisolone dose pack.

Reduce the HER1/EGFR dose, if after two to four weeks the toxicities have not sufficiently abated, then the HER1/EGFR therapy should be interrupted. Once the skin reactions have resolved or diminished in severity, the HER1/EGFR dose may typically be restarted or re-escalated.

Results of a recent double-blind, placebo-controlled study suggest tetracycline may be effective in decreasing EGFR-associated rash severity and improving some quality-of-life parameters (e.g., irritation, burning, stinging).7 Remaining alert to these reactions in patients receiving HER1/EGFRs is important for monitoring treatment and managing patients. TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Castillo L, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Fischel JL, et al. Pharmacologic background of EGFR targeting. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(7):1007-1012.

- Robert C, Soria JC, Spatz A et al. Cutaneous side effects of kinase inhibitors and blocking antibodies. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(7):491-500.

- Peréz-Soler R, Saltz L. Cutaneous adverse effects with HER1/EGFR-targeted agents: Is there a silver lining? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5235-5246.

- Seiverling EV, Fernandez EM, Adams D. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor associated skin eruption. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(4)368-369. Available at http://findarticles.com/p/articles/ mi_m0PDG/ is_4_5/ai_n16361317Accessed August 7, 2007

- Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. www.oncolink.com/treatment/article.cfm?c=12&s=90&id=268. Accessed August 7, 2007

- Lynch TJ, Kim ES, Eaby B, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated toxicities: An evolving paradigm in clinical management. Oncologist 2007;12(5):610-621.

- Jatoi A, Rowland K, Sloan JA, et al. J Clin Oncol 2007; ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. Vol. 25(18S);June 20:LBA9006.

Human epidural growth factor receptor (HER1/EGFR) signaling pathways are crucial in regulating cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.

HER1/EGFR is a protein tyrosine kinase with therapeutic applications in cancer treatment.1 Two approved drugs categories target HER1/EGFR: anti-HER1/EGFR monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and HER1/EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). The drugs have different complex actions, some leading to disruption of cellular processes at the level of cell division, apoptosis, and angiogenesis.

Approximately 30% to 100% of solid tumors express HER1/EGFR on the tumor surface, while some overexpress it. This is thought to lead to tumor growth.2,3 Increased HER1/EGFR activity has been associated with poor survival in some cancers.

The Agents

A number of HER1/EGFR TKIs are FDA approved and administered orally, including erlotinib (Tarceva), gefitinib (Iressa), imatinib (Gleevec), lapatinib (Tykerb), sorafenib (Nexavar), and sunitinib (Sutent).4-6

Cetuximab (Erbitux) and panitumumab (Vectibix) are approved mAbs given intravenously. Both categories treat different cancers including advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, renal cell carcinoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and others. The HER1/EGFR targeted agents have a more favorable side effect profile compared with more traditional chemotherapeutic agents with primarily dermatologic toxicities and limited hematopoietic effects. Because many patients are being treated with these oral anti-cancer agents, it is important to remain aware of the agents, their toxicities, and their management.

Adverse Effects

The most common adverse effect associated with HER1/EGFR inhibitors is a dose-dependent, folliculitis-like rash.

The rash affects up to two-thirds of treated patients within the first two weeks of therapy. It is usually on the face, neck, and upper torso and is characterized by inter- and intrafollicular papulopustules of mild-to-moderate severity. The rash develops in three phases: sensory disturbance with erythema and edema (weeks zero to one), papulopustular flare (weeks one to three), crusting (weeks three to five), and erythematotelangiectasias (weeks five to eight).

Dry skin and erythema may remain in the areas after resolution. The skin rash appears to be dose-dependent. The mechanism of the rash is not precisely known. However, HER1/EGFR is expressed by normal keratinocytes and skin fibroblasts, along the outer sheath of the hair follicle, and in many epidermal processes, which probably contributes.

Hair effects occur within two to three months of starting treatment. Scalp hair becomes more brittle, fine, and curly. Frontal alopecia gradually develops, and patients experience progressive trichomegaly of the eyelashes and hypertrichosis of the face. Paronychial inflammation can occur on the fingernails or toenails and be so painful it prevents patients from wearing shoes. Its origin is unknown, and it disappears after discontinuation of the drug. Xerosis is also common, which can be treated with topically applied 5% to 10% urea emollient.

Rash as a Marker

There appears to be some evidence of a relationship between HER1/EGFR efficacy and associated rash severity. There have been at least 19 trials and additional compassionate use centers that have found the relationship of a positive correlation between rash and response/survival.

For example, in a Phase II study in 57 patients with non-small cell lung cancer, those with grade zero rashes had a median survival of 1.5 months, those with rash grade one had a median survival of 8.5 months, and those with rash grades two or three had a 19.6 month survival. In another study with erlotinib monotherapy, patients with a skin rash had significantly greater survival rates (approximately 80%) than those without skin rashes. In trials of cetuximab in patients with different cancer types, those who developed a rash lived substantially longer than those who did not.

There are also data supporting gefitinib and cetuximab. Many of the studies note a poorer clinical outcome in those patients without rash. These findings suggest that lack of a rash after a specific period of therapy may be an early indicator of treatment failure and the need for another treatment.

Rash Treatment

While receiving treatment with these agents, patients should be advised to moisturize dry body areas twice daily with a thick alcohol-free emollient. Patients should minimize sun exposure and wear a broad-spectrum sunscreen (SPF 15). Zinc oxide or titanium dioxide is preferred over chemical sunscreens. The following treatment interventions are suggested:

- Mild toxicity: topical hydrocortisone 1% to 2.5% cream or clindamycin 1% gel. The HER1/EGFR dose should not be adjusted;

- Moderate toxicity: topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream, clindamycin 1% gel, or pimecrolimus 1% cream (Elidel) with doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day or minocycline 100mg orally twice a day. The HER1/EGFR dose should not be adjusted; or

- Severe toxicity: topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream, clindamycin 1% gel, or pimecrolimus 1% cream (Elidel) with doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day or minocycline 100mg orally twice a day. Also add methylprednisolone dose pack.

Reduce the HER1/EGFR dose, if after two to four weeks the toxicities have not sufficiently abated, then the HER1/EGFR therapy should be interrupted. Once the skin reactions have resolved or diminished in severity, the HER1/EGFR dose may typically be restarted or re-escalated.

Results of a recent double-blind, placebo-controlled study suggest tetracycline may be effective in decreasing EGFR-associated rash severity and improving some quality-of-life parameters (e.g., irritation, burning, stinging).7 Remaining alert to these reactions in patients receiving HER1/EGFRs is important for monitoring treatment and managing patients. TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Castillo L, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Fischel JL, et al. Pharmacologic background of EGFR targeting. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(7):1007-1012.

- Robert C, Soria JC, Spatz A et al. Cutaneous side effects of kinase inhibitors and blocking antibodies. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(7):491-500.

- Peréz-Soler R, Saltz L. Cutaneous adverse effects with HER1/EGFR-targeted agents: Is there a silver lining? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5235-5246.

- Seiverling EV, Fernandez EM, Adams D. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor associated skin eruption. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(4)368-369. Available at http://findarticles.com/p/articles/ mi_m0PDG/ is_4_5/ai_n16361317Accessed August 7, 2007

- Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. www.oncolink.com/treatment/article.cfm?c=12&s=90&id=268. Accessed August 7, 2007

- Lynch TJ, Kim ES, Eaby B, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated toxicities: An evolving paradigm in clinical management. Oncologist 2007;12(5):610-621.

- Jatoi A, Rowland K, Sloan JA, et al. J Clin Oncol 2007; ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. Vol. 25(18S);June 20:LBA9006.

Stress Ulcer Agents

An article published this year in the American Journal of Health-Systems Pharmacy defined stress ulcers as “acute superficial inflammatory lesions of the gastric mucosa induced when an individual is subjected to abnormally high physiologic demands.”1

These stress ulcers are believed to be caused by an imbalance between gastric acid production and the normal physiologic protective mucosal mechanisms in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Reduction of blood flow to the gastric mucosa may also lead to ischemic damage to the GI mucosa.

The development of stress ulcers, or stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD), occurs in 75% to 100% of critically ill patients within 24 hours of intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Although bleeding risk has decreased over the years, mortality from stress-related bleeding nears 50%. According a peer-reviewed guideline from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), indications for SRMD in the ICU setting include:2

- Coagulopathy;

- Mechanical ventilation longer than 48 hours;

- History of GI ulceration or bleeding within one year of the current admission;

- Glasgow Coma score of 10 or less (or if unable to obey simple commands);

- Thermal injury to more than 35% of the body surface area;

- Partial hepatectomy;

- Multiple trauma;

- Transplantation perioperatively in the ICU;

- Spinal cord injury;

- Hepatic failure; and

- Two or more of the following risk factors: sepsis, ICU stay of a week or longer, occult bleeding for more than six days, or high-dose corticosteroids (more than 250 mg a day of hydrocortisone or the equivalent).

Other risk factors for SRMD in ICU patients include multiorgan failure, chronic renal failure, major surgical procedures, shock, and tetraplegia.3,4

Recommended SRMD prophylaxis agents should be institution-based, taking into account the administration route (e.g., functioning GI tract), daily dosing regimens, adverse effect profile, drug interactions, and total costs. Classes that can be used include sucralfate, antacids, H2 receptor antagonists (H2RA), and proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Some patients may prefer the oral route. Some agents can be given in solution or suspension and administered via a nasogastric tube—but be aware of drug interactions. There are limited comparative data for preventing SRMD with these classes. The H2RA and PPI classes of agents are available in intravenous forms, which may be preferable in critically ill patients. However, none of the PPIs are FDA-approved for SRMD prophylaxis.

In the general patient population, SRMD prophylaxis with H2RAs or PPIs is common in 30% to 50% of patients without clear evidence of benefit. Qadeer, et al., identified a 0.4% bleeding rate in their retrospective case-control study of nearly 18,000 patients over a four-year period. In their study, the key risk factor for development of nosocomial GI bleeding was treatment with full-dose anticoagulation or clopidogrel.

Another concern they identified is that when a patient commences an SRMD prophylaxis agent in the hospital, they continue on it post-discharge when it is not needed. This creates an unnecessary cost burden and risks adverse drug interactions.

Todd Janicki, MD, and Scott Stewart, MD, both with the department of medicine at the State University of New York at Buffalo, this year reported on a review of evidence for SRMD prophylaxis in general medicine patients from the peer-reviewed literature.5 They found limited data, identifying only five citations meeting their evaluation criteria. Two of these studies noted only a 3% to 6% reduction in clinically significant bleeding utilizing SRMD prophylaxis. TH

Michele Kaufman is a clinical/managed care consultant and medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Grube RRA, May DB. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients not in intensive care units. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1396-400.

- ASHP Commission on Therapeutics. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56:347-379.

- Qadeer MA, Richter JE, Brotman DJ. Hospital-acquired gastrointestinal bleeding outside the critical care unit: risk factors, role of acid suppression, and endoscopy findings. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):13-20.

- Weinhouse GL, Manaker S. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in the intensive care unit. In: UpToDate, Rose, BD (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, Mass. 2007.

- Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):86-92.

An article published this year in the American Journal of Health-Systems Pharmacy defined stress ulcers as “acute superficial inflammatory lesions of the gastric mucosa induced when an individual is subjected to abnormally high physiologic demands.”1

These stress ulcers are believed to be caused by an imbalance between gastric acid production and the normal physiologic protective mucosal mechanisms in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Reduction of blood flow to the gastric mucosa may also lead to ischemic damage to the GI mucosa.

The development of stress ulcers, or stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD), occurs in 75% to 100% of critically ill patients within 24 hours of intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Although bleeding risk has decreased over the years, mortality from stress-related bleeding nears 50%. According a peer-reviewed guideline from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), indications for SRMD in the ICU setting include:2

- Coagulopathy;

- Mechanical ventilation longer than 48 hours;

- History of GI ulceration or bleeding within one year of the current admission;

- Glasgow Coma score of 10 or less (or if unable to obey simple commands);

- Thermal injury to more than 35% of the body surface area;

- Partial hepatectomy;

- Multiple trauma;

- Transplantation perioperatively in the ICU;

- Spinal cord injury;

- Hepatic failure; and

- Two or more of the following risk factors: sepsis, ICU stay of a week or longer, occult bleeding for more than six days, or high-dose corticosteroids (more than 250 mg a day of hydrocortisone or the equivalent).

Other risk factors for SRMD in ICU patients include multiorgan failure, chronic renal failure, major surgical procedures, shock, and tetraplegia.3,4

Recommended SRMD prophylaxis agents should be institution-based, taking into account the administration route (e.g., functioning GI tract), daily dosing regimens, adverse effect profile, drug interactions, and total costs. Classes that can be used include sucralfate, antacids, H2 receptor antagonists (H2RA), and proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Some patients may prefer the oral route. Some agents can be given in solution or suspension and administered via a nasogastric tube—but be aware of drug interactions. There are limited comparative data for preventing SRMD with these classes. The H2RA and PPI classes of agents are available in intravenous forms, which may be preferable in critically ill patients. However, none of the PPIs are FDA-approved for SRMD prophylaxis.

In the general patient population, SRMD prophylaxis with H2RAs or PPIs is common in 30% to 50% of patients without clear evidence of benefit. Qadeer, et al., identified a 0.4% bleeding rate in their retrospective case-control study of nearly 18,000 patients over a four-year period. In their study, the key risk factor for development of nosocomial GI bleeding was treatment with full-dose anticoagulation or clopidogrel.

Another concern they identified is that when a patient commences an SRMD prophylaxis agent in the hospital, they continue on it post-discharge when it is not needed. This creates an unnecessary cost burden and risks adverse drug interactions.

Todd Janicki, MD, and Scott Stewart, MD, both with the department of medicine at the State University of New York at Buffalo, this year reported on a review of evidence for SRMD prophylaxis in general medicine patients from the peer-reviewed literature.5 They found limited data, identifying only five citations meeting their evaluation criteria. Two of these studies noted only a 3% to 6% reduction in clinically significant bleeding utilizing SRMD prophylaxis. TH

Michele Kaufman is a clinical/managed care consultant and medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Grube RRA, May DB. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients not in intensive care units. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1396-400.

- ASHP Commission on Therapeutics. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56:347-379.

- Qadeer MA, Richter JE, Brotman DJ. Hospital-acquired gastrointestinal bleeding outside the critical care unit: risk factors, role of acid suppression, and endoscopy findings. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):13-20.

- Weinhouse GL, Manaker S. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in the intensive care unit. In: UpToDate, Rose, BD (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, Mass. 2007.

- Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):86-92.

An article published this year in the American Journal of Health-Systems Pharmacy defined stress ulcers as “acute superficial inflammatory lesions of the gastric mucosa induced when an individual is subjected to abnormally high physiologic demands.”1

These stress ulcers are believed to be caused by an imbalance between gastric acid production and the normal physiologic protective mucosal mechanisms in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Reduction of blood flow to the gastric mucosa may also lead to ischemic damage to the GI mucosa.

The development of stress ulcers, or stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD), occurs in 75% to 100% of critically ill patients within 24 hours of intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Although bleeding risk has decreased over the years, mortality from stress-related bleeding nears 50%. According a peer-reviewed guideline from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), indications for SRMD in the ICU setting include:2

- Coagulopathy;

- Mechanical ventilation longer than 48 hours;

- History of GI ulceration or bleeding within one year of the current admission;

- Glasgow Coma score of 10 or less (or if unable to obey simple commands);

- Thermal injury to more than 35% of the body surface area;

- Partial hepatectomy;

- Multiple trauma;

- Transplantation perioperatively in the ICU;

- Spinal cord injury;

- Hepatic failure; and

- Two or more of the following risk factors: sepsis, ICU stay of a week or longer, occult bleeding for more than six days, or high-dose corticosteroids (more than 250 mg a day of hydrocortisone or the equivalent).

Other risk factors for SRMD in ICU patients include multiorgan failure, chronic renal failure, major surgical procedures, shock, and tetraplegia.3,4

Recommended SRMD prophylaxis agents should be institution-based, taking into account the administration route (e.g., functioning GI tract), daily dosing regimens, adverse effect profile, drug interactions, and total costs. Classes that can be used include sucralfate, antacids, H2 receptor antagonists (H2RA), and proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Some patients may prefer the oral route. Some agents can be given in solution or suspension and administered via a nasogastric tube—but be aware of drug interactions. There are limited comparative data for preventing SRMD with these classes. The H2RA and PPI classes of agents are available in intravenous forms, which may be preferable in critically ill patients. However, none of the PPIs are FDA-approved for SRMD prophylaxis.

In the general patient population, SRMD prophylaxis with H2RAs or PPIs is common in 30% to 50% of patients without clear evidence of benefit. Qadeer, et al., identified a 0.4% bleeding rate in their retrospective case-control study of nearly 18,000 patients over a four-year period. In their study, the key risk factor for development of nosocomial GI bleeding was treatment with full-dose anticoagulation or clopidogrel.

Another concern they identified is that when a patient commences an SRMD prophylaxis agent in the hospital, they continue on it post-discharge when it is not needed. This creates an unnecessary cost burden and risks adverse drug interactions.

Todd Janicki, MD, and Scott Stewart, MD, both with the department of medicine at the State University of New York at Buffalo, this year reported on a review of evidence for SRMD prophylaxis in general medicine patients from the peer-reviewed literature.5 They found limited data, identifying only five citations meeting their evaluation criteria. Two of these studies noted only a 3% to 6% reduction in clinically significant bleeding utilizing SRMD prophylaxis. TH

Michele Kaufman is a clinical/managed care consultant and medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Grube RRA, May DB. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients not in intensive care units. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1396-400.

- ASHP Commission on Therapeutics. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56:347-379.

- Qadeer MA, Richter JE, Brotman DJ. Hospital-acquired gastrointestinal bleeding outside the critical care unit: risk factors, role of acid suppression, and endoscopy findings. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):13-20.

- Weinhouse GL, Manaker S. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in the intensive care unit. In: UpToDate, Rose, BD (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, Mass. 2007.

- Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):86-92.

Steroid Stress Dosing

Adrenal response to stress can vary broadly from patient to patient. For hospitalists, the challenge is predicting patients’ cortisol needs.

The variability exists whether one is dealing with a healthy patient or a patient with adrenal insufficiency (AI).1 Glucocorticoid use is even more complicated in patients with chronic autoimmune or inflammatory disorders who have been treated with high doses of glucocorticoids, or with those who are hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppressed.

Additionally, glucocorticoid administration is the most common cause of AI. Guidelines for adrenal supplementation therapy published in JAMA in 2002 note the difficulty in determining exact patient needs. JAMA’s review of guidelines for adrenal supplementation therapy is based on expert opinion, extrapolation from research literature, and clinical experience rather than clinical trials and should be consulted for more specific patient recommendations.2

Around the same time, similar guidelines on the management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients on chronic glucocorticoids were published in the Bulletin on the Rheumatic Diseases.3 The guidelines suggest lower doses and shorter therapy than many textbooks advocate to counter problems associated with excessive steroid dosing. Problems such as immunosuppression, hyperglycemia, hypertension, acute psychosis, and accelerated protein catabolism lead to poor wound healing.

Additionally, the guidelines recommend that all patients receiving chronic glucocorticoids with an illness or while undergoing any procedure continue their normal daily glucocorticoid therapy. The authors caution that in patients with rheumatic disease, discontinuation of even low glucocorticoid doses may lead to a significant disease flare. Patients who receive 5 mg or less of prednisone daily do not require additional supplementation—regardless of whether they are undergoing a procedure or have an intercurrent illness. Patients undergoing superficial surgical procedures while less than an hour under local anesthesia (e.g., routine dental work, skin biopsy, minor orthopedic surgery) require their normal daily glucocorticoid dose without additional supplementation.

Patients with primary AI should receive individualized supplemental homeostatic glucocorticoid replacement therapy—usually with 20 to 30 mg of hydrocortisone two to three times daily in divided doses. Adjust based on patient factors and use of concomitant medications. Also consider that mineralocorticoid replacement may be necessary in these patients.

When considering patients for potential use of corticosteroids in the hospital, identify those who may be HPA-axis suppressed versus those who are not. The time to achieve HPA-axis suppression varies among patients. Patients can be considered not suppressed if: