User login

Atypical Antipsychotics Tied to Adrenal Issues

NEW ORLEANS — It is important to recognize the potential for atypical antipsychotics to cause adrenal insufficiency to ensure that the condition is managed appropriately, according to Dr. Violeta Tan and Dr. Natalie Rasgon.

They described the case of a 54-year-old man with a history of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder who was admitted to the hospital after complaining of malaise 9 days after a previous admission for a urinary tract infection that had been treated with ciprofloxacin.

At the first admission, the patient was restarted on 225 mg/day of bupropion and 300 mg/day of quetiapine (Seroquel), both of which he had discontinued 6–8 months prior, said Dr. Tan and Dr. Rasgon, who presented the case in a poster session at the American Psychiatric Association's Institute of Psychiatric Services.

Symptoms at the time of the second admission included fatigue, warmth, chills, loose stools, mild headache, and reproducible chest wall pain. Laboratory findings showed that previously normal eosinophil levels were elevated (6.5%–8.3%), reported Dr. Tan and Dr. Rasgon, both of Stanford (Calif.) University.

A work-up for infection, malignancy, and rheumatologic conditions was negative, and primary adrenal insufficiency was ruled out based on the findings of a cosyntropin stimulation test. However, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels (less than 5 pg/mL) indicated secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency, and a review of the patient's medications alerted the authors to the possibility of quetiapine-associated ACTH and cortisol reductions.

Atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine can reduce cortisol levels—often in association with improved psychopathology. Thus, although the cortisol-lowering effects of such drugs may ameliorate negative symptomatology, the reduction could be detrimental, they wrote.

However, adrenal insufficiency caused by such agents has not been specifically studied, and although it might seem appropriate to discontinue the “offending agent,” the risks of discontinuing antipsychotics should be weighed against the benefits of preventing adrenal insufficiency sequelae, they added.

In the current case, which also demonstrated that quetiapine administration, particularly under precipitating circumstances such as an infection or stress, can contribute to reductions in ACTH and cortisol secretion, the patient's condition improved after quetiapine, a standard treatment for adrenal insufficiency, was administered at 20 mg every morning and at 10 mg at bedtime.

Atypical antipsychotics can cause adrenal insufficiency, which presents ambiguously, and awareness of this can be key in preventing false diagnoses, they said.

Adrenal insufficiency can present ambiguously, which can lead to false diagnoses. DR. RASGON

Spotting Adrenal Insufficiency

Dr. Tan and Dr. Rasgon say determining whether a patient has developed adrenal insufficiency requires an investigation into four areas:

▸ Symptoms. Look for weakness and fatigue, abdominal distress, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, myalgia or arthralgia, postural dizziness, salt craving, headache, impaired memory, and depression.

▸ Physical findings. Some factors to look out for are increased pigmentation, postural hypotension, tachycardia, fever, decreased body hair, vitiligo, amenorrhea, and cold intolerance.

▸ Laboratory findings. Red flags include hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, eosinophilia, and elevated thyroid stimulating hormone.

▸ Clinical problems. Watch for hemodynamic instability, ongoing inflammation, multiple-organ dysfunction, and hypoglycemia.

NEW ORLEANS — It is important to recognize the potential for atypical antipsychotics to cause adrenal insufficiency to ensure that the condition is managed appropriately, according to Dr. Violeta Tan and Dr. Natalie Rasgon.

They described the case of a 54-year-old man with a history of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder who was admitted to the hospital after complaining of malaise 9 days after a previous admission for a urinary tract infection that had been treated with ciprofloxacin.

At the first admission, the patient was restarted on 225 mg/day of bupropion and 300 mg/day of quetiapine (Seroquel), both of which he had discontinued 6–8 months prior, said Dr. Tan and Dr. Rasgon, who presented the case in a poster session at the American Psychiatric Association's Institute of Psychiatric Services.

Symptoms at the time of the second admission included fatigue, warmth, chills, loose stools, mild headache, and reproducible chest wall pain. Laboratory findings showed that previously normal eosinophil levels were elevated (6.5%–8.3%), reported Dr. Tan and Dr. Rasgon, both of Stanford (Calif.) University.

A work-up for infection, malignancy, and rheumatologic conditions was negative, and primary adrenal insufficiency was ruled out based on the findings of a cosyntropin stimulation test. However, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels (less than 5 pg/mL) indicated secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency, and a review of the patient's medications alerted the authors to the possibility of quetiapine-associated ACTH and cortisol reductions.

Atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine can reduce cortisol levels—often in association with improved psychopathology. Thus, although the cortisol-lowering effects of such drugs may ameliorate negative symptomatology, the reduction could be detrimental, they wrote.

However, adrenal insufficiency caused by such agents has not been specifically studied, and although it might seem appropriate to discontinue the “offending agent,” the risks of discontinuing antipsychotics should be weighed against the benefits of preventing adrenal insufficiency sequelae, they added.

In the current case, which also demonstrated that quetiapine administration, particularly under precipitating circumstances such as an infection or stress, can contribute to reductions in ACTH and cortisol secretion, the patient's condition improved after quetiapine, a standard treatment for adrenal insufficiency, was administered at 20 mg every morning and at 10 mg at bedtime.

Atypical antipsychotics can cause adrenal insufficiency, which presents ambiguously, and awareness of this can be key in preventing false diagnoses, they said.

Adrenal insufficiency can present ambiguously, which can lead to false diagnoses. DR. RASGON

Spotting Adrenal Insufficiency

Dr. Tan and Dr. Rasgon say determining whether a patient has developed adrenal insufficiency requires an investigation into four areas:

▸ Symptoms. Look for weakness and fatigue, abdominal distress, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, myalgia or arthralgia, postural dizziness, salt craving, headache, impaired memory, and depression.

▸ Physical findings. Some factors to look out for are increased pigmentation, postural hypotension, tachycardia, fever, decreased body hair, vitiligo, amenorrhea, and cold intolerance.

▸ Laboratory findings. Red flags include hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, eosinophilia, and elevated thyroid stimulating hormone.

▸ Clinical problems. Watch for hemodynamic instability, ongoing inflammation, multiple-organ dysfunction, and hypoglycemia.

NEW ORLEANS — It is important to recognize the potential for atypical antipsychotics to cause adrenal insufficiency to ensure that the condition is managed appropriately, according to Dr. Violeta Tan and Dr. Natalie Rasgon.

They described the case of a 54-year-old man with a history of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder who was admitted to the hospital after complaining of malaise 9 days after a previous admission for a urinary tract infection that had been treated with ciprofloxacin.

At the first admission, the patient was restarted on 225 mg/day of bupropion and 300 mg/day of quetiapine (Seroquel), both of which he had discontinued 6–8 months prior, said Dr. Tan and Dr. Rasgon, who presented the case in a poster session at the American Psychiatric Association's Institute of Psychiatric Services.

Symptoms at the time of the second admission included fatigue, warmth, chills, loose stools, mild headache, and reproducible chest wall pain. Laboratory findings showed that previously normal eosinophil levels were elevated (6.5%–8.3%), reported Dr. Tan and Dr. Rasgon, both of Stanford (Calif.) University.

A work-up for infection, malignancy, and rheumatologic conditions was negative, and primary adrenal insufficiency was ruled out based on the findings of a cosyntropin stimulation test. However, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels (less than 5 pg/mL) indicated secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency, and a review of the patient's medications alerted the authors to the possibility of quetiapine-associated ACTH and cortisol reductions.

Atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine can reduce cortisol levels—often in association with improved psychopathology. Thus, although the cortisol-lowering effects of such drugs may ameliorate negative symptomatology, the reduction could be detrimental, they wrote.

However, adrenal insufficiency caused by such agents has not been specifically studied, and although it might seem appropriate to discontinue the “offending agent,” the risks of discontinuing antipsychotics should be weighed against the benefits of preventing adrenal insufficiency sequelae, they added.

In the current case, which also demonstrated that quetiapine administration, particularly under precipitating circumstances such as an infection or stress, can contribute to reductions in ACTH and cortisol secretion, the patient's condition improved after quetiapine, a standard treatment for adrenal insufficiency, was administered at 20 mg every morning and at 10 mg at bedtime.

Atypical antipsychotics can cause adrenal insufficiency, which presents ambiguously, and awareness of this can be key in preventing false diagnoses, they said.

Adrenal insufficiency can present ambiguously, which can lead to false diagnoses. DR. RASGON

Spotting Adrenal Insufficiency

Dr. Tan and Dr. Rasgon say determining whether a patient has developed adrenal insufficiency requires an investigation into four areas:

▸ Symptoms. Look for weakness and fatigue, abdominal distress, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, myalgia or arthralgia, postural dizziness, salt craving, headache, impaired memory, and depression.

▸ Physical findings. Some factors to look out for are increased pigmentation, postural hypotension, tachycardia, fever, decreased body hair, vitiligo, amenorrhea, and cold intolerance.

▸ Laboratory findings. Red flags include hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, eosinophilia, and elevated thyroid stimulating hormone.

▸ Clinical problems. Watch for hemodynamic instability, ongoing inflammation, multiple-organ dysfunction, and hypoglycemia.

Streamlined Testosterone Order Template to Improve the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypogonadism in Veterans

Streamlined Testosterone Order Template to Improve the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypogonadism in Veterans

Testosterone therapy is administered following pragmatic diagnostic evaluation and workup to assess whether an adult male is hypogonadal, based on symptoms consistent with androgen deficiency and low morning serum testosterone concentrations on ≥ 2 occasions. Effects of testosterone administration include the development or maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics and increases in libido, muscle strength, fat-free mass, and bone density.

Testosterone prescriptions have markedly increased in the past 20 years, including within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system.1-3 This trend may be influenced by various factors, including patient perceptions of benefit, an increase in marketing, and the availability of more user-friendly formulations.

Since 2006, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines have recommended specific clinical and laboratory evaluation and counseling prior to starting testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).4-8 However, research has shown poor adherence to these recommendations, including at the VA, which raises concerns about inappropriate TRT initiation without proper diagnostic evaluation.9,10 Observational research has suggested a possible link between testosterone therapy and increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) events. The US Food and Drug Administration prescribing information includes boxed warnings about potential risks of high blood pressure, myocardial infarction, stroke, and CV-related mortality with testosterone treatment, contact transfer of transdermal testosterone, and pulmonary oil microembolism with testosterone undecanoate injections.11-15

A VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) review of VA clinician adherence to clinical and laboratory evaluation guidelines for testosterone deficiency found poor adherence among VA practitioners and made recommendations for improvement.4,15 These focused on establishing clinical signs and symptoms consistent with testosterone deficiency, confirming hypogonadism by repeated testosterone testing, determining the etiology of hypogonadism by measuring gonadotropins, initiating a discussion of risks and benefits of TRT, and assessing clinical improvement and obtaining an updated hematocrit test within 3 to 6 months of initiation.

The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) developed a local prior authorization template to assist health care practitioners (HCPs) to address the OIG recommendations. This testosterone order template (TOT) aimed to improve the diagnosis, evaluation, and monitoring of TRT in males with hypogonadism, combined with existing VA pharmacy criteria for the use of testosterone based on Endocrine Society guidelines. A version of the VAPSHCS TOT was approved as the national VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) template.

Preliminary evaluation of the TOT suggested improved short-term adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation.16 This quality improvement study sought to assess the long-term effectiveness of the TOT with respect to clinical practice guideline adherence. The OIG did not address prostate-specific antigen (PSA) monitoring because understanding of the relationship between TRT and the risks of elevated PSA levels remains incomplete.6,17 This project hypothesized that implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT incorporated into CPRS would result in higher adherence rates to guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory evaluation, in addition to counseling of men with hypogonadism prior to initiation of TRT.

Methods

Eligible participants were cisgender males who received a new testosterone prescription, had ≥ 2 clinic visits at VAPSHCS, and no previous testosterone prescription in the previous 2 years. Individuals were excluded if they had testosterone administered at VAPSHCS; were prescribed testosterone at another facility (VA or community-based); pilot tested an initial version of the TOT prior to November 30, 2019; or had an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes for hypopituitarism, gender identity disorder, history of sexual assignment, or Klinefelter syndrome for which testosterone therapy was already approved. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were identified by an algorithm developed by the VAPSHCS pharmacoeconomist.

This quality improvement project used a retrospective, pre-post experimental design. Electronic chart review and systematic manual review of all eligible patient charts were performed for the pretemplate period (December 1, 2018, to November 30, 2019) and after the template implementation, (December 1, 2021, to November 30, 2022).

An initial version of the TOT was implemented on July 1, 2019, but was not fully integrated into CPRS until early 2020; individuals in whom the TOT was used prior to November 30, 2019, were excluded. Data from the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic were avoided because of alterations in clinic and prescribing practices. As a quality improvement project, the TOT evaluation was exempt from formal review by the VAPSHCS Institutional Review Board, as determined by the Director of the Office of Transformation/Quality/Safety/Value.

Interventions

Testosterone is a Schedule III controlled substance with potential risks and a propensity for varied prescribing practices. It was designated as a restricted drug requiring a prior authorization drug request (PADR) for which a specific TOT was developed, approved by the VAPSHCS Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and incorporated into CPRS. A team of pharmacists, primary care physicians, geriatricians, endocrinologists, and health informatics experts created and developed the TOT. Pharmacists managed and monitored its completion.

The process for prescribing testosterone via the TOT is outlined in the eAppendix. When an HCP orders testosterone in CPRS, reminders prompt them to use the TOT and indicate required laboratory measurements (an order set is provided). Completion of TOT is not necessary to order testosterone for patients with an existing diagnosis of an organic cause of hypogonadism (eg, Klinefelter syndrome or hypopituitarism) or transgender women (assigned male at birth). In the TOT, the prescriber must also indicate signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; required laboratory tests; and counseling regarding potential risks and benefits of TRT. A pharmacist reviews the TOT and either approves or rejects the testosterone prescription and provides follow-up guidance to the prescriber. The completed TOT serves as documentation of guideline adherence in CPRS. The TOT also includes sections for first renewal testosterone prescriptions, addressing guideline recommendations for follow-up laboratory evaluation and clinical response to TRT. Due to limited completion of this section in the posttemplate period, evaluating adherence to follow-up recommendations was not feasible.

Measures

This project assessed the percentage of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period with an approved PADR. Documentation of specific guideline-recommended measures was assessed: signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; ≥ 2 serum testosterone measurements (≥ 2 total, free and total, or 2 free testosterone levels, and ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10

The project also assessed the proportion of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period who had all hormone tests (≥ 2 serum testosterone and LH and FSH concentrations), all laboratory tests (hormone tests and hematocrit), and all 5 guideline-recommended measures.

Analysis

Statistical comparisons between the proportions of patients in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods for each measure were performed using a χ2 test, without correction for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 10.0. A P value < .05 was considered significant for all comparisons.

Results

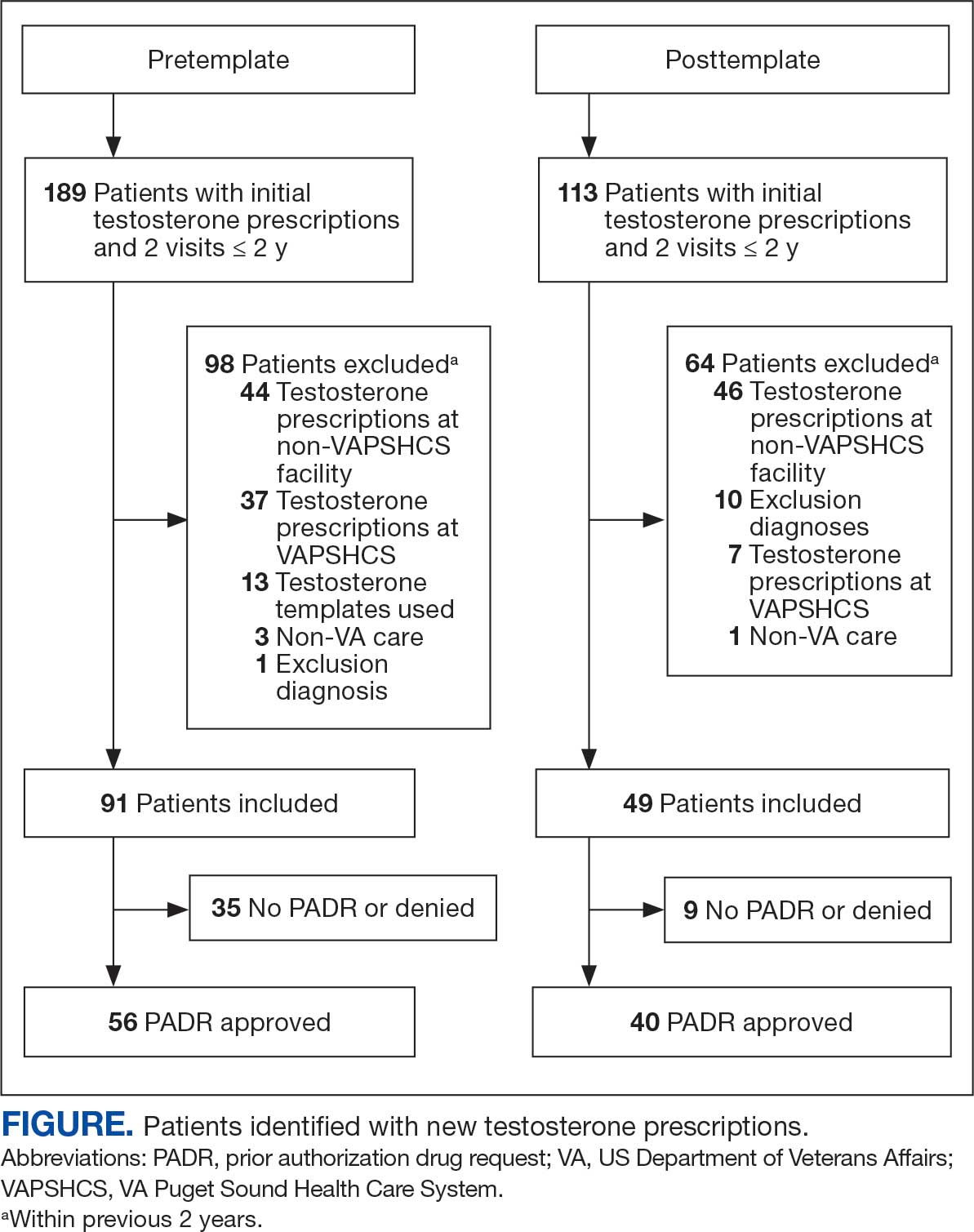

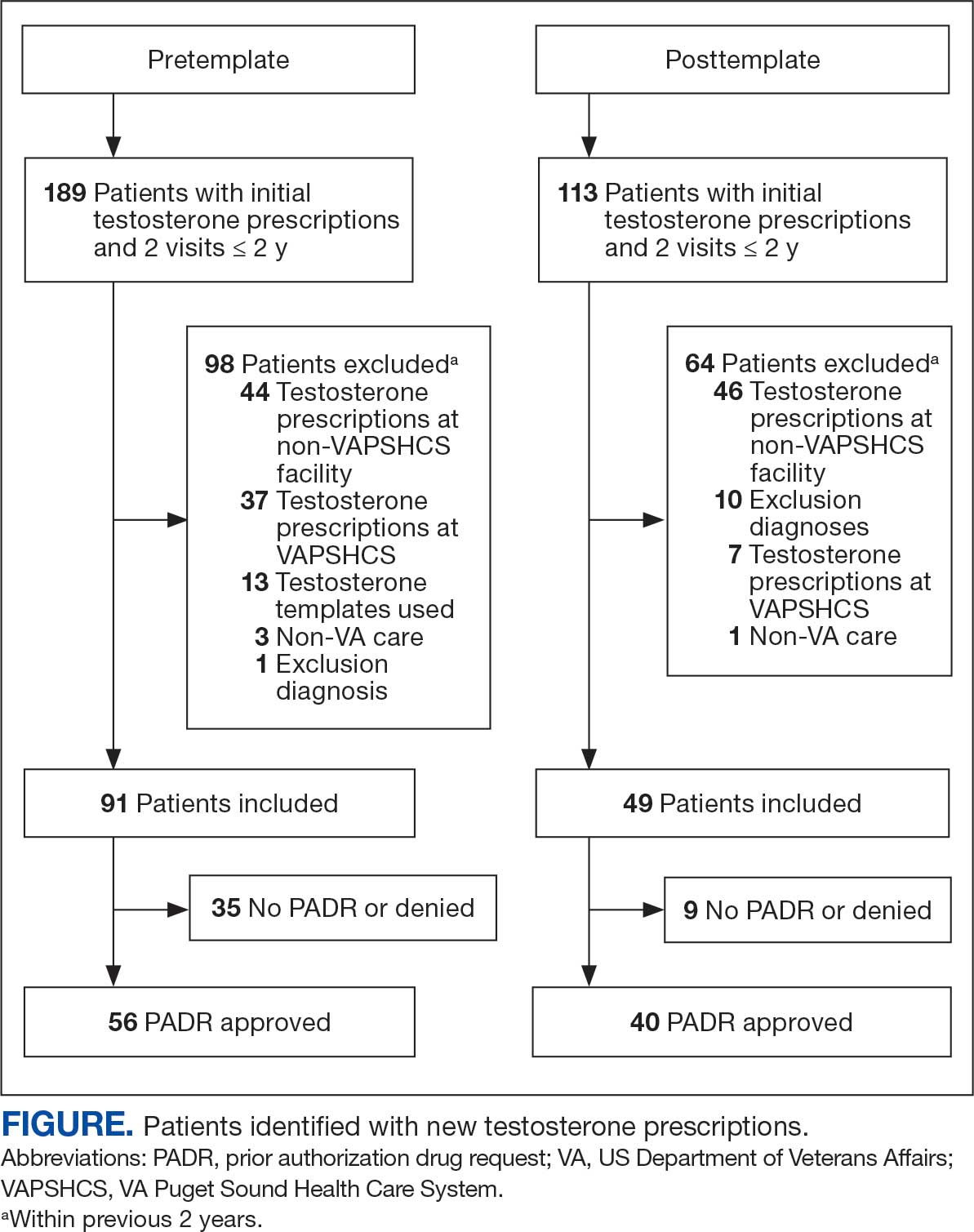

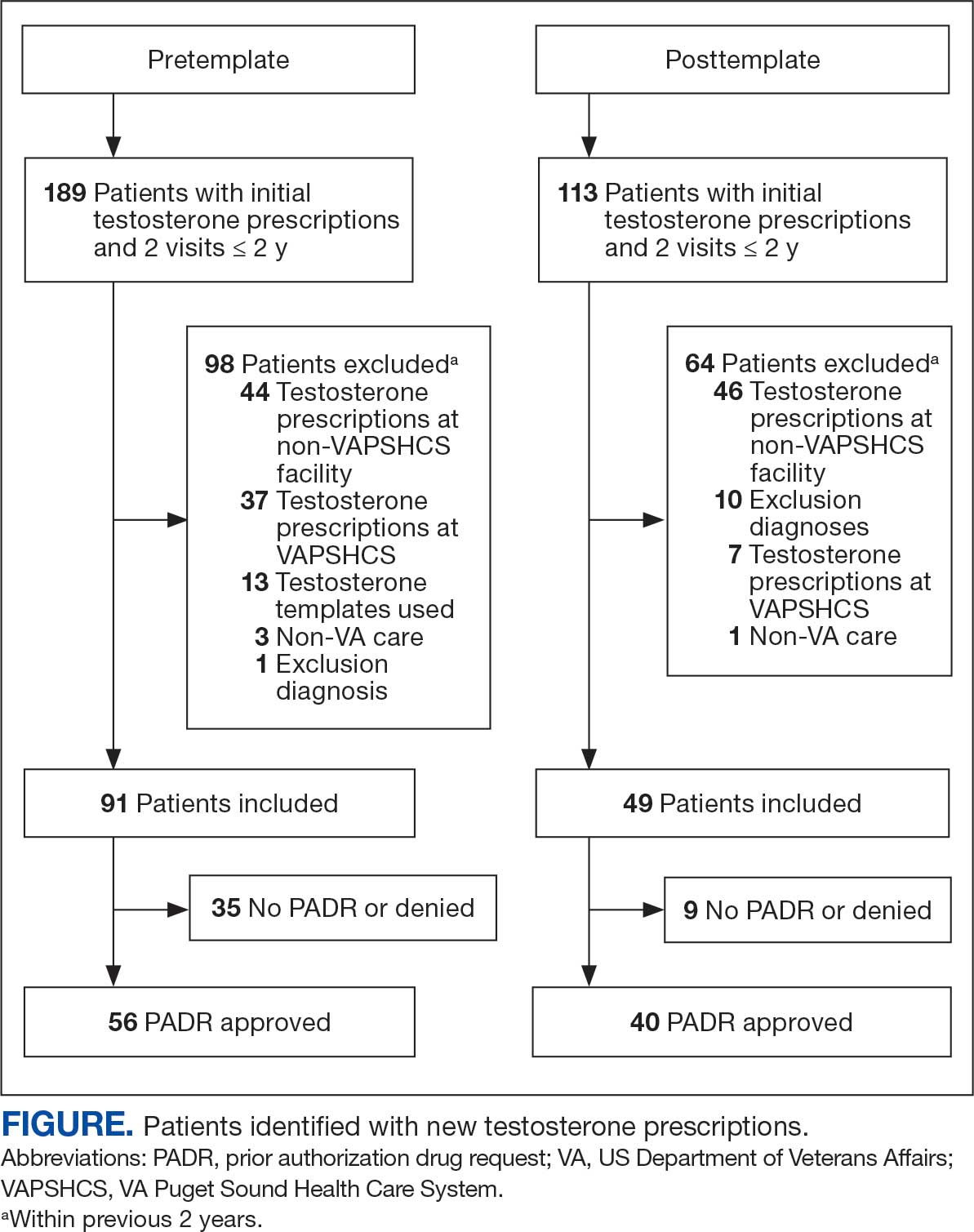

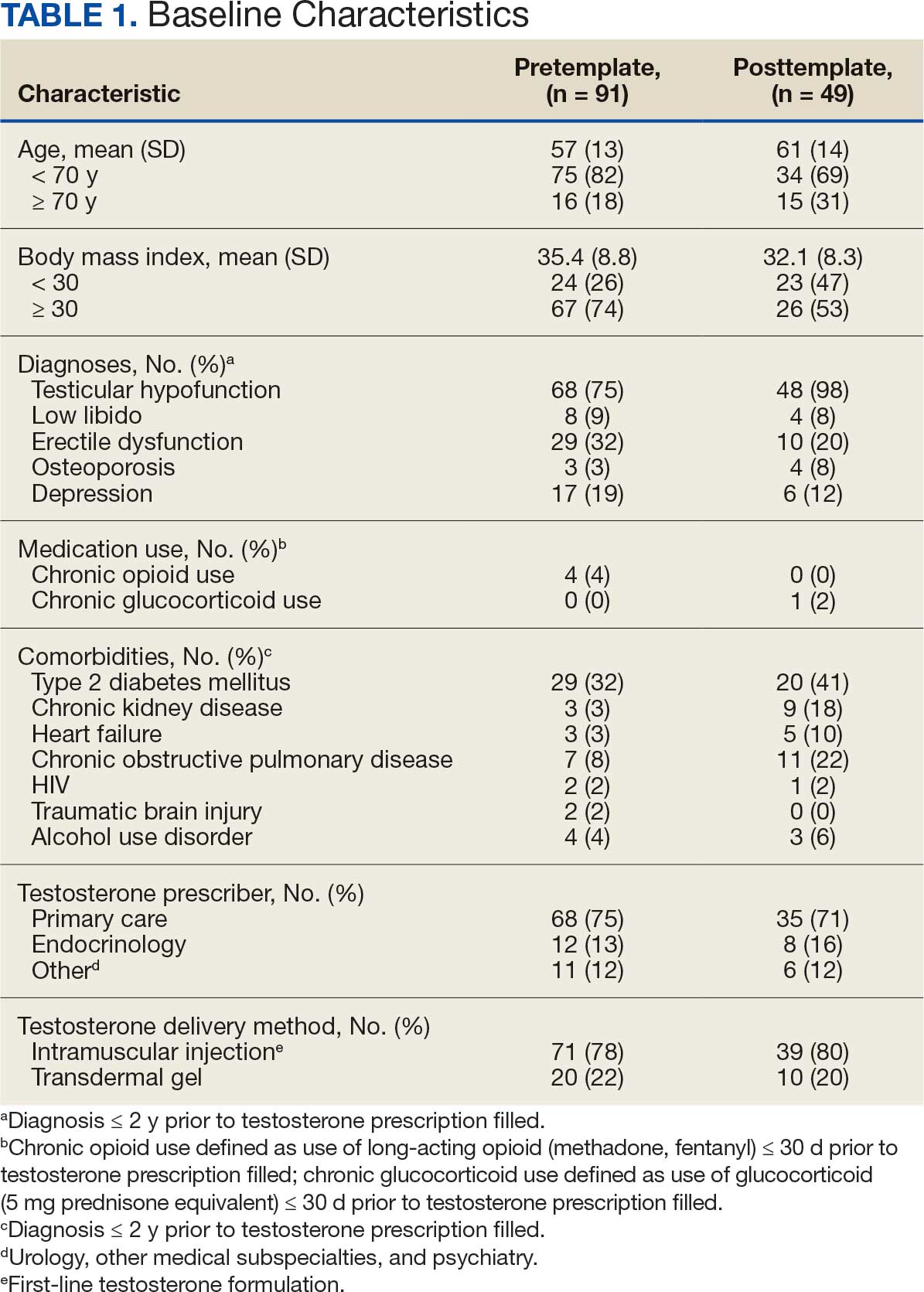

Chart review identified 189 patients in the pretemplate period and 113 patients in the posttemplate period with a new testosterone prescription (Figure). After exclusions, 91 and 49 patients, respectively, met eligibility criteria (Table 1). Fifty-six patients (62%) pretemplate and 40 patients (82%) posttemplate (P = .015) had approved PADRs and comprised the groups that were analyzed (Table 2).

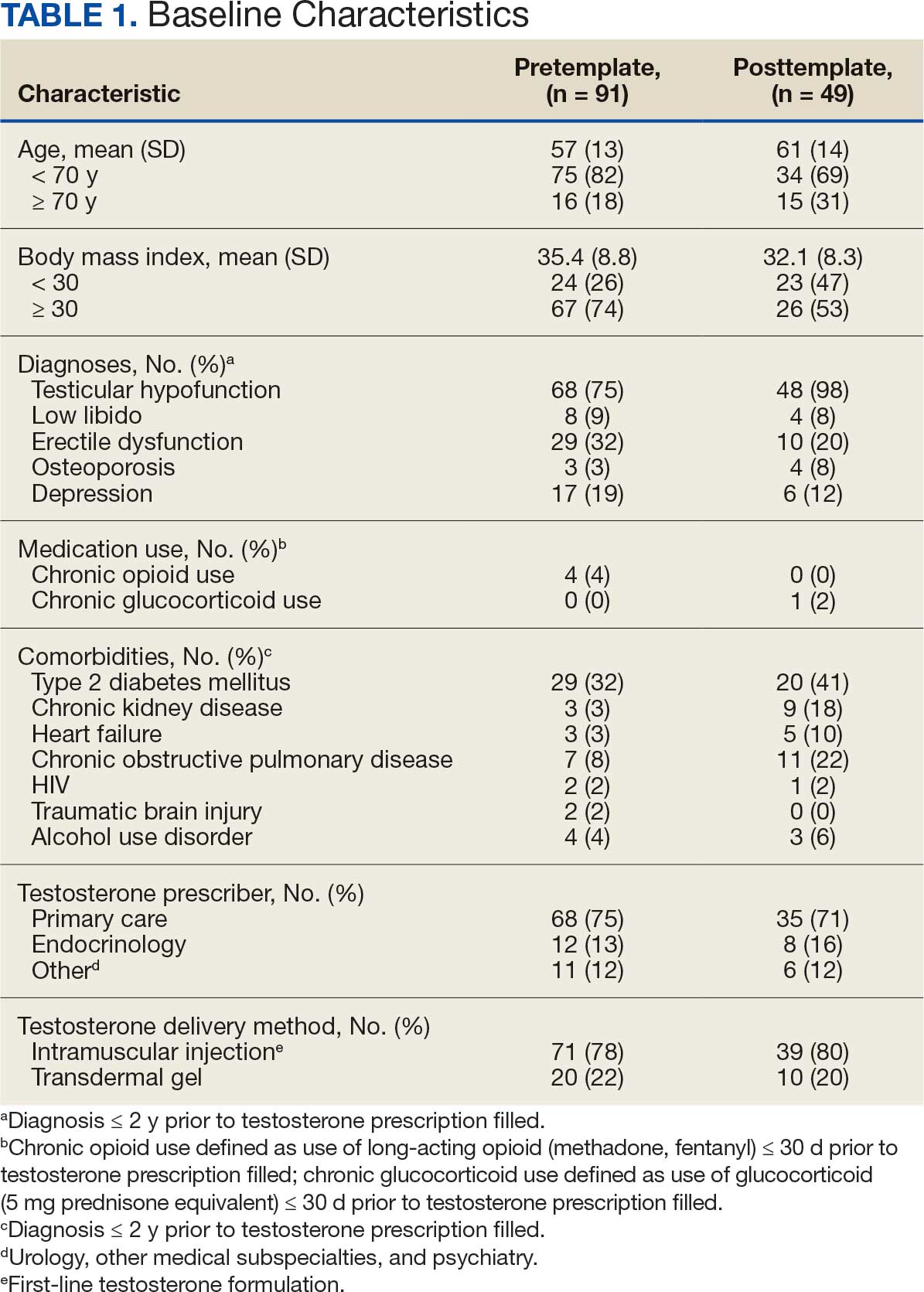

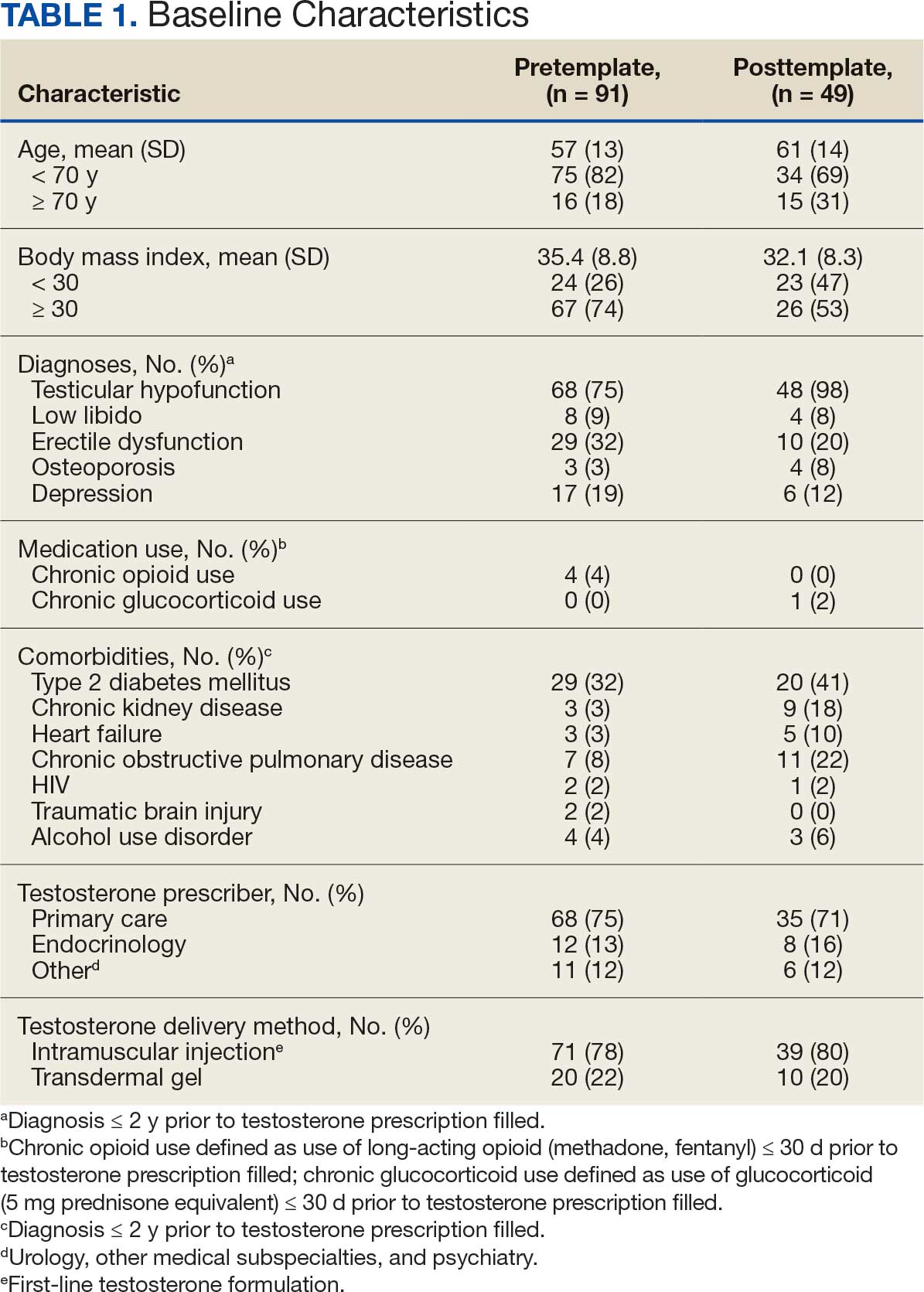

The mean age and body mass index were similar in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods, but there was variation in the proportions of patients aged < 70 years and those with a body mass index < 30 between the groups. The most common diagnosis in both groups was testicular hypofunction, and the most common comorbidity was type 2 diabetes mellitus. Concomitant use of opioids or glucocorticoids that can lower testosterone levels was rare. Most testosterone prescriptions originated from primary care clinics in both periods: 68 (75%) in the pretemplate period and 35 (71%) in the posttemplate period. Most testosterone treatment was delivered by intramuscular injection.

In the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period, the proportion of patients with an approved PADR (82% vs 62%, P = .02), and documentation of signs and symptoms of hypogonadism (93% vs 71%, P = .002) prior to starting TRT were higher, while the percentage of patients having ≥ 2 testosterone measurements (85% vs 89%, P = .53), ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10 AM (78% vs 75%, P = .70), and hematocrit measured (95% vs 91%, P = .47) were similar. Rates of LH and FSH testing were higher in the posttemplate period (80%) vs the pretemplate period (63%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .07), and discussion of the risks and benefits of TRT was higher in the posttemplate period (58%) vs the pretemplate period (34%) (P = .02). The percentage of patients who had all hormone measurements (total and/or free testosterone, LH, and FSH) was higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (59%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .06). The rates of all guideline-recommended laboratory test orders were higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (55%) (P = .03), and all 5 guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory measures were higher in the posttemplate period (45%) vs the pretemplate period (18%) (P = .004).

Discussion

The implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT in CPRS demonstrated higher adherence to evidence-based guidelines for diagnosing and evaluating hypogonadism before TRT. After TOT implementation, a higher proportion of patients had documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency, underwent all recommended laboratory tests, and had discussions about the risks and benefits of TRT. Adherence to 5 clinical and laboratory measures recommended by Endocrine Society guidelines was higher after TOT implementation, indicating improved prescribing practices.4

The requirement for TOT completion before testosterone prescription and its management by trained pharmacists likely contributed to higher adherence to guideline recommendations than previously reported. Integration of the TOT into CPRS with pharmacy oversight may have enhanced adherence by summarizing and codifying evidence-based guideline recommendations for clinical and biochemical evaluation prior to TRT initiation, offering relevant education to clinicians and pharmacists, automatically importing pertinent clinical information and laboratory results, and generating CPRS documentation to reduce clinician burden during patient care.

The proportion of patients with documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency before TRT increased from the pretemplate period (71%) to the posttemplate period (93%), indicating that most patients receiving TRT had clinical manifestations of hypogonadism. This aligns with Endocrine Society guidelines, which define hypogonadism as a clinical disorder characterized by clinical manifestations of testosterone deficiency and persistently low serum testosterone levels on ≥ 2 separate occasions.4,6 However, recent trends in direct-to-consumer advertising for testosterone and the rise of “low T” clinics may contribute to increased testing, varied practices, and inappropriate testosterone therapy initiation (eg, in men with low testosterone levels who lack symptoms of hypogonadism).18 Improved adherence in documenting clinical hypogonadism with implementation of the TOT reinforces the value of incorporating educational material, as previously reported.11

Adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation of the TOT in this project was higher than those previously reported. In a study of 111,631 outpatient veterans prescribed testosterone from 2009 to 2012, only 18.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 3.5% had ≥ 2 testosterone, LH, and FSH levels measured prior to the initiation of a TRT.9 In a report of 63,534 insured patients who received TRT from 2010 to 2012, 40.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 12% had LH and/or FSH measured prior to the initiation.8

Low rates of guideline-recommended laboratory tests prior to initiation of testosterone treatment were reported in prior non-VA studies.19,20 Poor guideline adherence reinforces the need for clinician education or other methods to improve TRT and ensure appropriate prescribing practices across health care systems. The TOT described in this project is a sustainable clinical tool with the potential to improve testosterone prescribing practices.

The high rates of adherence to guideline recommendations at VAPSHCS likely stem from local endocrine expertise and ongoing educational initiatives, as well as the requirement for template completion before testosterone prescription. However, most testosterone prescriptions were initiated by primary care and monitored by pharmacists with varying degrees of training and clinical experience in hypogonadism and TRT.

However, adherence to guideline recommendations was modest, suggesting there is still an opportunity for improvement. The decision to initiate therapy should be made only after appropriate counseling with patients regarding its potential benefits and risks. Reports on the CV risk of TRT have been mixed. The 2023 TRAVERSE study found no increase in major adverse CV events among older men with hypogonadism and pre-existing CV risks undergoing TRT, but noted higher instances of pulmonary embolism, atrial fibrillation, and acute kidney injury.21 This highlights the need for clinicians to continue to engage in informed decision-making with patients. Effective pretreatment counseling is important but time-consuming; future TOT monitoring and modifications could consider mandatory checkboxes to document counseling on TRT risks and benefits.

The TOT described in this study could be adapted and incorporated into the prescribing process and electronic health record of larger health care systems. Use of an electronic template allows for automatic real-time dashboard monitoring of organization performance. The TOT described could be modified or simplified for specialty or primary care clinics or individual practitioners to improve adherence to evidence-based guideline recommendations and quality of care.

Strengths

A strength of this study is the multidisciplinary team (composed of stakeholders with experience in VA health care system and subject matter experts in hypogonadism) that developed and incorporated a user-friendly template for testosterone prescriptions; the use of evidence-based guideline recommendations; and the use of a structured chart review permitted accurate assessment of adherence to recommendations to document signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency and a discussion of potential risks and benefits prior to TRT. To our knowledge, these recommendations have not been assessed in previous reports.

Limitations

The retrospective pre-post design of this study precludes a conclusion that implementation of the TOT caused the increase in adherence to guideline recommendations. Improved adherence could have resulted from the ongoing development of the preauthorization process for testosterone prescriptions or other changes over time. However, the preauthorization process had already been established for many years prior to template implementation. Forty-nine patients had new prescriptions for testosterone in the posttemplate period compared to 91 in the pretemplate period, but TRT was initiated in accordance with guideline recommendations more appropriately in the posttemplate period. The study’s sample size was small, and many eligible patients were excluded; however, exclusions were necessary to evaluate men who had new testosterone prescriptions for which the template was designed. Most men excluded were already taking testosterone.

Conclusions

The implementation of a CPRS-based TOT improved adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis, evaluation, and counseling of patients with hypogonadism before starting TRT. While there were improvements in adherence with the TOT, the relatively low proportion of patients with documentation of TRT risks and benefits and all guideline recommendations highlights the need for additional efforts to further strengthen adherence to guideline recommendations and ensure appropriate evaluation, counseling, and prescribing practices before initiating TRT.

- Layton JB, Li D, Meier CR, et al. Testosterone lab testing and initiation in the United Kingdom and the United States, 2000 to 2011. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:835-842. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-3570

- Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Westra JR, et al. Testosterone prescribing in the United States, 2002-2016. JAMA. 2018;320:200-202. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7999

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Rose AJ. Patterns of testosterone prescription overuse. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24:240-245. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000336

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1995-2010. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2847

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2536-2559. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2354

- Bhasin S, Brito JP, Cunningham GR, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1715-1744. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00229

- Mulhall JP, Trost LW, Brannigan RE, et al. Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2018;200:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2018.03.115

- Muram D, Zhang X, Cui Z, et al. Use of hormone testing for the diagnosis and evaluation of male hypogonadism and monitoring of testosterone therapy: application of hormone testing guideline recommendations in clinical practice. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1886-1894. doi:10.1111/jsm.12968

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, et al. Ascertainment of testosterone prescribing practices in the VA. Med Care. 2015;53:746-752. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000398?

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, et al. Who gets testosterone? Patient characteristics associated with testosterone prescribing in the Veteran Affairs system: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:304-311. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3940-7

- Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:109-122. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1000485

- Vigen R, O’Donnell CI, Barón AE, et al. Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels. JAMA. 2013;310:1829-1836. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280386

- Finkle WD, Greenland S, Ridgeway GK, et al. Increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction following testosterone therapy prescription in men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85805. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085805

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA cautions about using testosterone products for low testosterone due to aging; requires labeling change to inform of possible increased risk of heart attack and stroke with use. FDA.gov. March 3, 2015. Updated February 28, 2025. Accessed July 8, 2025. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm436259.htm

- US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Healthcare inspection – testosterone replacement therapy initiation and follow-up evaluation in VA male patients. April 11, 2018. Accessed July 8, 2025. https://www.vaoig.gov/reports/national-healthcare-review/healthcare-inspection-testosterone-replacement-therapy

- Narla R, Mobley D, Nguyen EHK, et al. Preliminary evaluation of an order template to improve diagnosis and testosterone therapy of hypogonadism in veterans. Fed Pract. 2021;38:121-127. doi:10.12788/fp.0103

- Bhasin S, Travison TG, Pencina KM, et al. Prostate safety events during testosterone replacement therapy in men with hypogonadism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2348692. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.48692

- Dubin JM, Jesse E, Fantus RJ, et al. Guideline-discordant care among direct-to-consumer testosterone therapy platforms. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:1321-1323. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4928

- Baillargeon J, Urban RJ, Ottenbacher KJ, et al. Trends in androgen prescribing in the United States, 2001 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1465-1466. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6895

- Locke JA, Flannigan R, Günther OP, et al. Testosterone therapy: prescribing and monitoring patterns of practice in British Columbia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2021;15:e110-e117. doi:10.5489/cuaj.6586

- Lincoff AM, Bhasin S, Flevaris P, et al. Cardiovascular safety of testosterone-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:107-117. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2215025

Testosterone therapy is administered following pragmatic diagnostic evaluation and workup to assess whether an adult male is hypogonadal, based on symptoms consistent with androgen deficiency and low morning serum testosterone concentrations on ≥ 2 occasions. Effects of testosterone administration include the development or maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics and increases in libido, muscle strength, fat-free mass, and bone density.

Testosterone prescriptions have markedly increased in the past 20 years, including within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system.1-3 This trend may be influenced by various factors, including patient perceptions of benefit, an increase in marketing, and the availability of more user-friendly formulations.

Since 2006, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines have recommended specific clinical and laboratory evaluation and counseling prior to starting testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).4-8 However, research has shown poor adherence to these recommendations, including at the VA, which raises concerns about inappropriate TRT initiation without proper diagnostic evaluation.9,10 Observational research has suggested a possible link between testosterone therapy and increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) events. The US Food and Drug Administration prescribing information includes boxed warnings about potential risks of high blood pressure, myocardial infarction, stroke, and CV-related mortality with testosterone treatment, contact transfer of transdermal testosterone, and pulmonary oil microembolism with testosterone undecanoate injections.11-15

A VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) review of VA clinician adherence to clinical and laboratory evaluation guidelines for testosterone deficiency found poor adherence among VA practitioners and made recommendations for improvement.4,15 These focused on establishing clinical signs and symptoms consistent with testosterone deficiency, confirming hypogonadism by repeated testosterone testing, determining the etiology of hypogonadism by measuring gonadotropins, initiating a discussion of risks and benefits of TRT, and assessing clinical improvement and obtaining an updated hematocrit test within 3 to 6 months of initiation.

The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) developed a local prior authorization template to assist health care practitioners (HCPs) to address the OIG recommendations. This testosterone order template (TOT) aimed to improve the diagnosis, evaluation, and monitoring of TRT in males with hypogonadism, combined with existing VA pharmacy criteria for the use of testosterone based on Endocrine Society guidelines. A version of the VAPSHCS TOT was approved as the national VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) template.

Preliminary evaluation of the TOT suggested improved short-term adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation.16 This quality improvement study sought to assess the long-term effectiveness of the TOT with respect to clinical practice guideline adherence. The OIG did not address prostate-specific antigen (PSA) monitoring because understanding of the relationship between TRT and the risks of elevated PSA levels remains incomplete.6,17 This project hypothesized that implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT incorporated into CPRS would result in higher adherence rates to guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory evaluation, in addition to counseling of men with hypogonadism prior to initiation of TRT.

Methods

Eligible participants were cisgender males who received a new testosterone prescription, had ≥ 2 clinic visits at VAPSHCS, and no previous testosterone prescription in the previous 2 years. Individuals were excluded if they had testosterone administered at VAPSHCS; were prescribed testosterone at another facility (VA or community-based); pilot tested an initial version of the TOT prior to November 30, 2019; or had an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes for hypopituitarism, gender identity disorder, history of sexual assignment, or Klinefelter syndrome for which testosterone therapy was already approved. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were identified by an algorithm developed by the VAPSHCS pharmacoeconomist.

This quality improvement project used a retrospective, pre-post experimental design. Electronic chart review and systematic manual review of all eligible patient charts were performed for the pretemplate period (December 1, 2018, to November 30, 2019) and after the template implementation, (December 1, 2021, to November 30, 2022).

An initial version of the TOT was implemented on July 1, 2019, but was not fully integrated into CPRS until early 2020; individuals in whom the TOT was used prior to November 30, 2019, were excluded. Data from the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic were avoided because of alterations in clinic and prescribing practices. As a quality improvement project, the TOT evaluation was exempt from formal review by the VAPSHCS Institutional Review Board, as determined by the Director of the Office of Transformation/Quality/Safety/Value.

Interventions

Testosterone is a Schedule III controlled substance with potential risks and a propensity for varied prescribing practices. It was designated as a restricted drug requiring a prior authorization drug request (PADR) for which a specific TOT was developed, approved by the VAPSHCS Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and incorporated into CPRS. A team of pharmacists, primary care physicians, geriatricians, endocrinologists, and health informatics experts created and developed the TOT. Pharmacists managed and monitored its completion.

The process for prescribing testosterone via the TOT is outlined in the eAppendix. When an HCP orders testosterone in CPRS, reminders prompt them to use the TOT and indicate required laboratory measurements (an order set is provided). Completion of TOT is not necessary to order testosterone for patients with an existing diagnosis of an organic cause of hypogonadism (eg, Klinefelter syndrome or hypopituitarism) or transgender women (assigned male at birth). In the TOT, the prescriber must also indicate signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; required laboratory tests; and counseling regarding potential risks and benefits of TRT. A pharmacist reviews the TOT and either approves or rejects the testosterone prescription and provides follow-up guidance to the prescriber. The completed TOT serves as documentation of guideline adherence in CPRS. The TOT also includes sections for first renewal testosterone prescriptions, addressing guideline recommendations for follow-up laboratory evaluation and clinical response to TRT. Due to limited completion of this section in the posttemplate period, evaluating adherence to follow-up recommendations was not feasible.

Measures

This project assessed the percentage of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period with an approved PADR. Documentation of specific guideline-recommended measures was assessed: signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; ≥ 2 serum testosterone measurements (≥ 2 total, free and total, or 2 free testosterone levels, and ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10

The project also assessed the proportion of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period who had all hormone tests (≥ 2 serum testosterone and LH and FSH concentrations), all laboratory tests (hormone tests and hematocrit), and all 5 guideline-recommended measures.

Analysis

Statistical comparisons between the proportions of patients in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods for each measure were performed using a χ2 test, without correction for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 10.0. A P value < .05 was considered significant for all comparisons.

Results

Chart review identified 189 patients in the pretemplate period and 113 patients in the posttemplate period with a new testosterone prescription (Figure). After exclusions, 91 and 49 patients, respectively, met eligibility criteria (Table 1). Fifty-six patients (62%) pretemplate and 40 patients (82%) posttemplate (P = .015) had approved PADRs and comprised the groups that were analyzed (Table 2).

The mean age and body mass index were similar in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods, but there was variation in the proportions of patients aged < 70 years and those with a body mass index < 30 between the groups. The most common diagnosis in both groups was testicular hypofunction, and the most common comorbidity was type 2 diabetes mellitus. Concomitant use of opioids or glucocorticoids that can lower testosterone levels was rare. Most testosterone prescriptions originated from primary care clinics in both periods: 68 (75%) in the pretemplate period and 35 (71%) in the posttemplate period. Most testosterone treatment was delivered by intramuscular injection.

In the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period, the proportion of patients with an approved PADR (82% vs 62%, P = .02), and documentation of signs and symptoms of hypogonadism (93% vs 71%, P = .002) prior to starting TRT were higher, while the percentage of patients having ≥ 2 testosterone measurements (85% vs 89%, P = .53), ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10 AM (78% vs 75%, P = .70), and hematocrit measured (95% vs 91%, P = .47) were similar. Rates of LH and FSH testing were higher in the posttemplate period (80%) vs the pretemplate period (63%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .07), and discussion of the risks and benefits of TRT was higher in the posttemplate period (58%) vs the pretemplate period (34%) (P = .02). The percentage of patients who had all hormone measurements (total and/or free testosterone, LH, and FSH) was higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (59%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .06). The rates of all guideline-recommended laboratory test orders were higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (55%) (P = .03), and all 5 guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory measures were higher in the posttemplate period (45%) vs the pretemplate period (18%) (P = .004).

Discussion

The implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT in CPRS demonstrated higher adherence to evidence-based guidelines for diagnosing and evaluating hypogonadism before TRT. After TOT implementation, a higher proportion of patients had documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency, underwent all recommended laboratory tests, and had discussions about the risks and benefits of TRT. Adherence to 5 clinical and laboratory measures recommended by Endocrine Society guidelines was higher after TOT implementation, indicating improved prescribing practices.4

The requirement for TOT completion before testosterone prescription and its management by trained pharmacists likely contributed to higher adherence to guideline recommendations than previously reported. Integration of the TOT into CPRS with pharmacy oversight may have enhanced adherence by summarizing and codifying evidence-based guideline recommendations for clinical and biochemical evaluation prior to TRT initiation, offering relevant education to clinicians and pharmacists, automatically importing pertinent clinical information and laboratory results, and generating CPRS documentation to reduce clinician burden during patient care.

The proportion of patients with documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency before TRT increased from the pretemplate period (71%) to the posttemplate period (93%), indicating that most patients receiving TRT had clinical manifestations of hypogonadism. This aligns with Endocrine Society guidelines, which define hypogonadism as a clinical disorder characterized by clinical manifestations of testosterone deficiency and persistently low serum testosterone levels on ≥ 2 separate occasions.4,6 However, recent trends in direct-to-consumer advertising for testosterone and the rise of “low T” clinics may contribute to increased testing, varied practices, and inappropriate testosterone therapy initiation (eg, in men with low testosterone levels who lack symptoms of hypogonadism).18 Improved adherence in documenting clinical hypogonadism with implementation of the TOT reinforces the value of incorporating educational material, as previously reported.11

Adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation of the TOT in this project was higher than those previously reported. In a study of 111,631 outpatient veterans prescribed testosterone from 2009 to 2012, only 18.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 3.5% had ≥ 2 testosterone, LH, and FSH levels measured prior to the initiation of a TRT.9 In a report of 63,534 insured patients who received TRT from 2010 to 2012, 40.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 12% had LH and/or FSH measured prior to the initiation.8

Low rates of guideline-recommended laboratory tests prior to initiation of testosterone treatment were reported in prior non-VA studies.19,20 Poor guideline adherence reinforces the need for clinician education or other methods to improve TRT and ensure appropriate prescribing practices across health care systems. The TOT described in this project is a sustainable clinical tool with the potential to improve testosterone prescribing practices.

The high rates of adherence to guideline recommendations at VAPSHCS likely stem from local endocrine expertise and ongoing educational initiatives, as well as the requirement for template completion before testosterone prescription. However, most testosterone prescriptions were initiated by primary care and monitored by pharmacists with varying degrees of training and clinical experience in hypogonadism and TRT.

However, adherence to guideline recommendations was modest, suggesting there is still an opportunity for improvement. The decision to initiate therapy should be made only after appropriate counseling with patients regarding its potential benefits and risks. Reports on the CV risk of TRT have been mixed. The 2023 TRAVERSE study found no increase in major adverse CV events among older men with hypogonadism and pre-existing CV risks undergoing TRT, but noted higher instances of pulmonary embolism, atrial fibrillation, and acute kidney injury.21 This highlights the need for clinicians to continue to engage in informed decision-making with patients. Effective pretreatment counseling is important but time-consuming; future TOT monitoring and modifications could consider mandatory checkboxes to document counseling on TRT risks and benefits.

The TOT described in this study could be adapted and incorporated into the prescribing process and electronic health record of larger health care systems. Use of an electronic template allows for automatic real-time dashboard monitoring of organization performance. The TOT described could be modified or simplified for specialty or primary care clinics or individual practitioners to improve adherence to evidence-based guideline recommendations and quality of care.

Strengths

A strength of this study is the multidisciplinary team (composed of stakeholders with experience in VA health care system and subject matter experts in hypogonadism) that developed and incorporated a user-friendly template for testosterone prescriptions; the use of evidence-based guideline recommendations; and the use of a structured chart review permitted accurate assessment of adherence to recommendations to document signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency and a discussion of potential risks and benefits prior to TRT. To our knowledge, these recommendations have not been assessed in previous reports.

Limitations

The retrospective pre-post design of this study precludes a conclusion that implementation of the TOT caused the increase in adherence to guideline recommendations. Improved adherence could have resulted from the ongoing development of the preauthorization process for testosterone prescriptions or other changes over time. However, the preauthorization process had already been established for many years prior to template implementation. Forty-nine patients had new prescriptions for testosterone in the posttemplate period compared to 91 in the pretemplate period, but TRT was initiated in accordance with guideline recommendations more appropriately in the posttemplate period. The study’s sample size was small, and many eligible patients were excluded; however, exclusions were necessary to evaluate men who had new testosterone prescriptions for which the template was designed. Most men excluded were already taking testosterone.

Conclusions

The implementation of a CPRS-based TOT improved adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis, evaluation, and counseling of patients with hypogonadism before starting TRT. While there were improvements in adherence with the TOT, the relatively low proportion of patients with documentation of TRT risks and benefits and all guideline recommendations highlights the need for additional efforts to further strengthen adherence to guideline recommendations and ensure appropriate evaluation, counseling, and prescribing practices before initiating TRT.

Testosterone therapy is administered following pragmatic diagnostic evaluation and workup to assess whether an adult male is hypogonadal, based on symptoms consistent with androgen deficiency and low morning serum testosterone concentrations on ≥ 2 occasions. Effects of testosterone administration include the development or maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics and increases in libido, muscle strength, fat-free mass, and bone density.

Testosterone prescriptions have markedly increased in the past 20 years, including within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system.1-3 This trend may be influenced by various factors, including patient perceptions of benefit, an increase in marketing, and the availability of more user-friendly formulations.

Since 2006, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines have recommended specific clinical and laboratory evaluation and counseling prior to starting testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).4-8 However, research has shown poor adherence to these recommendations, including at the VA, which raises concerns about inappropriate TRT initiation without proper diagnostic evaluation.9,10 Observational research has suggested a possible link between testosterone therapy and increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) events. The US Food and Drug Administration prescribing information includes boxed warnings about potential risks of high blood pressure, myocardial infarction, stroke, and CV-related mortality with testosterone treatment, contact transfer of transdermal testosterone, and pulmonary oil microembolism with testosterone undecanoate injections.11-15

A VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) review of VA clinician adherence to clinical and laboratory evaluation guidelines for testosterone deficiency found poor adherence among VA practitioners and made recommendations for improvement.4,15 These focused on establishing clinical signs and symptoms consistent with testosterone deficiency, confirming hypogonadism by repeated testosterone testing, determining the etiology of hypogonadism by measuring gonadotropins, initiating a discussion of risks and benefits of TRT, and assessing clinical improvement and obtaining an updated hematocrit test within 3 to 6 months of initiation.

The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) developed a local prior authorization template to assist health care practitioners (HCPs) to address the OIG recommendations. This testosterone order template (TOT) aimed to improve the diagnosis, evaluation, and monitoring of TRT in males with hypogonadism, combined with existing VA pharmacy criteria for the use of testosterone based on Endocrine Society guidelines. A version of the VAPSHCS TOT was approved as the national VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) template.

Preliminary evaluation of the TOT suggested improved short-term adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation.16 This quality improvement study sought to assess the long-term effectiveness of the TOT with respect to clinical practice guideline adherence. The OIG did not address prostate-specific antigen (PSA) monitoring because understanding of the relationship between TRT and the risks of elevated PSA levels remains incomplete.6,17 This project hypothesized that implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT incorporated into CPRS would result in higher adherence rates to guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory evaluation, in addition to counseling of men with hypogonadism prior to initiation of TRT.

Methods

Eligible participants were cisgender males who received a new testosterone prescription, had ≥ 2 clinic visits at VAPSHCS, and no previous testosterone prescription in the previous 2 years. Individuals were excluded if they had testosterone administered at VAPSHCS; were prescribed testosterone at another facility (VA or community-based); pilot tested an initial version of the TOT prior to November 30, 2019; or had an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes for hypopituitarism, gender identity disorder, history of sexual assignment, or Klinefelter syndrome for which testosterone therapy was already approved. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were identified by an algorithm developed by the VAPSHCS pharmacoeconomist.

This quality improvement project used a retrospective, pre-post experimental design. Electronic chart review and systematic manual review of all eligible patient charts were performed for the pretemplate period (December 1, 2018, to November 30, 2019) and after the template implementation, (December 1, 2021, to November 30, 2022).

An initial version of the TOT was implemented on July 1, 2019, but was not fully integrated into CPRS until early 2020; individuals in whom the TOT was used prior to November 30, 2019, were excluded. Data from the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic were avoided because of alterations in clinic and prescribing practices. As a quality improvement project, the TOT evaluation was exempt from formal review by the VAPSHCS Institutional Review Board, as determined by the Director of the Office of Transformation/Quality/Safety/Value.

Interventions

Testosterone is a Schedule III controlled substance with potential risks and a propensity for varied prescribing practices. It was designated as a restricted drug requiring a prior authorization drug request (PADR) for which a specific TOT was developed, approved by the VAPSHCS Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and incorporated into CPRS. A team of pharmacists, primary care physicians, geriatricians, endocrinologists, and health informatics experts created and developed the TOT. Pharmacists managed and monitored its completion.

The process for prescribing testosterone via the TOT is outlined in the eAppendix. When an HCP orders testosterone in CPRS, reminders prompt them to use the TOT and indicate required laboratory measurements (an order set is provided). Completion of TOT is not necessary to order testosterone for patients with an existing diagnosis of an organic cause of hypogonadism (eg, Klinefelter syndrome or hypopituitarism) or transgender women (assigned male at birth). In the TOT, the prescriber must also indicate signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; required laboratory tests; and counseling regarding potential risks and benefits of TRT. A pharmacist reviews the TOT and either approves or rejects the testosterone prescription and provides follow-up guidance to the prescriber. The completed TOT serves as documentation of guideline adherence in CPRS. The TOT also includes sections for first renewal testosterone prescriptions, addressing guideline recommendations for follow-up laboratory evaluation and clinical response to TRT. Due to limited completion of this section in the posttemplate period, evaluating adherence to follow-up recommendations was not feasible.

Measures

This project assessed the percentage of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period with an approved PADR. Documentation of specific guideline-recommended measures was assessed: signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; ≥ 2 serum testosterone measurements (≥ 2 total, free and total, or 2 free testosterone levels, and ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10

The project also assessed the proportion of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period who had all hormone tests (≥ 2 serum testosterone and LH and FSH concentrations), all laboratory tests (hormone tests and hematocrit), and all 5 guideline-recommended measures.

Analysis

Statistical comparisons between the proportions of patients in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods for each measure were performed using a χ2 test, without correction for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 10.0. A P value < .05 was considered significant for all comparisons.

Results

Chart review identified 189 patients in the pretemplate period and 113 patients in the posttemplate period with a new testosterone prescription (Figure). After exclusions, 91 and 49 patients, respectively, met eligibility criteria (Table 1). Fifty-six patients (62%) pretemplate and 40 patients (82%) posttemplate (P = .015) had approved PADRs and comprised the groups that were analyzed (Table 2).

The mean age and body mass index were similar in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods, but there was variation in the proportions of patients aged < 70 years and those with a body mass index < 30 between the groups. The most common diagnosis in both groups was testicular hypofunction, and the most common comorbidity was type 2 diabetes mellitus. Concomitant use of opioids or glucocorticoids that can lower testosterone levels was rare. Most testosterone prescriptions originated from primary care clinics in both periods: 68 (75%) in the pretemplate period and 35 (71%) in the posttemplate period. Most testosterone treatment was delivered by intramuscular injection.

In the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period, the proportion of patients with an approved PADR (82% vs 62%, P = .02), and documentation of signs and symptoms of hypogonadism (93% vs 71%, P = .002) prior to starting TRT were higher, while the percentage of patients having ≥ 2 testosterone measurements (85% vs 89%, P = .53), ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10 AM (78% vs 75%, P = .70), and hematocrit measured (95% vs 91%, P = .47) were similar. Rates of LH and FSH testing were higher in the posttemplate period (80%) vs the pretemplate period (63%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .07), and discussion of the risks and benefits of TRT was higher in the posttemplate period (58%) vs the pretemplate period (34%) (P = .02). The percentage of patients who had all hormone measurements (total and/or free testosterone, LH, and FSH) was higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (59%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .06). The rates of all guideline-recommended laboratory test orders were higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (55%) (P = .03), and all 5 guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory measures were higher in the posttemplate period (45%) vs the pretemplate period (18%) (P = .004).

Discussion

The implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT in CPRS demonstrated higher adherence to evidence-based guidelines for diagnosing and evaluating hypogonadism before TRT. After TOT implementation, a higher proportion of patients had documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency, underwent all recommended laboratory tests, and had discussions about the risks and benefits of TRT. Adherence to 5 clinical and laboratory measures recommended by Endocrine Society guidelines was higher after TOT implementation, indicating improved prescribing practices.4

The requirement for TOT completion before testosterone prescription and its management by trained pharmacists likely contributed to higher adherence to guideline recommendations than previously reported. Integration of the TOT into CPRS with pharmacy oversight may have enhanced adherence by summarizing and codifying evidence-based guideline recommendations for clinical and biochemical evaluation prior to TRT initiation, offering relevant education to clinicians and pharmacists, automatically importing pertinent clinical information and laboratory results, and generating CPRS documentation to reduce clinician burden during patient care.

The proportion of patients with documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency before TRT increased from the pretemplate period (71%) to the posttemplate period (93%), indicating that most patients receiving TRT had clinical manifestations of hypogonadism. This aligns with Endocrine Society guidelines, which define hypogonadism as a clinical disorder characterized by clinical manifestations of testosterone deficiency and persistently low serum testosterone levels on ≥ 2 separate occasions.4,6 However, recent trends in direct-to-consumer advertising for testosterone and the rise of “low T” clinics may contribute to increased testing, varied practices, and inappropriate testosterone therapy initiation (eg, in men with low testosterone levels who lack symptoms of hypogonadism).18 Improved adherence in documenting clinical hypogonadism with implementation of the TOT reinforces the value of incorporating educational material, as previously reported.11

Adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation of the TOT in this project was higher than those previously reported. In a study of 111,631 outpatient veterans prescribed testosterone from 2009 to 2012, only 18.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 3.5% had ≥ 2 testosterone, LH, and FSH levels measured prior to the initiation of a TRT.9 In a report of 63,534 insured patients who received TRT from 2010 to 2012, 40.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 12% had LH and/or FSH measured prior to the initiation.8

Low rates of guideline-recommended laboratory tests prior to initiation of testosterone treatment were reported in prior non-VA studies.19,20 Poor guideline adherence reinforces the need for clinician education or other methods to improve TRT and ensure appropriate prescribing practices across health care systems. The TOT described in this project is a sustainable clinical tool with the potential to improve testosterone prescribing practices.

The high rates of adherence to guideline recommendations at VAPSHCS likely stem from local endocrine expertise and ongoing educational initiatives, as well as the requirement for template completion before testosterone prescription. However, most testosterone prescriptions were initiated by primary care and monitored by pharmacists with varying degrees of training and clinical experience in hypogonadism and TRT.

However, adherence to guideline recommendations was modest, suggesting there is still an opportunity for improvement. The decision to initiate therapy should be made only after appropriate counseling with patients regarding its potential benefits and risks. Reports on the CV risk of TRT have been mixed. The 2023 TRAVERSE study found no increase in major adverse CV events among older men with hypogonadism and pre-existing CV risks undergoing TRT, but noted higher instances of pulmonary embolism, atrial fibrillation, and acute kidney injury.21 This highlights the need for clinicians to continue to engage in informed decision-making with patients. Effective pretreatment counseling is important but time-consuming; future TOT monitoring and modifications could consider mandatory checkboxes to document counseling on TRT risks and benefits.

The TOT described in this study could be adapted and incorporated into the prescribing process and electronic health record of larger health care systems. Use of an electronic template allows for automatic real-time dashboard monitoring of organization performance. The TOT described could be modified or simplified for specialty or primary care clinics or individual practitioners to improve adherence to evidence-based guideline recommendations and quality of care.

Strengths

A strength of this study is the multidisciplinary team (composed of stakeholders with experience in VA health care system and subject matter experts in hypogonadism) that developed and incorporated a user-friendly template for testosterone prescriptions; the use of evidence-based guideline recommendations; and the use of a structured chart review permitted accurate assessment of adherence to recommendations to document signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency and a discussion of potential risks and benefits prior to TRT. To our knowledge, these recommendations have not been assessed in previous reports.

Limitations

The retrospective pre-post design of this study precludes a conclusion that implementation of the TOT caused the increase in adherence to guideline recommendations. Improved adherence could have resulted from the ongoing development of the preauthorization process for testosterone prescriptions or other changes over time. However, the preauthorization process had already been established for many years prior to template implementation. Forty-nine patients had new prescriptions for testosterone in the posttemplate period compared to 91 in the pretemplate period, but TRT was initiated in accordance with guideline recommendations more appropriately in the posttemplate period. The study’s sample size was small, and many eligible patients were excluded; however, exclusions were necessary to evaluate men who had new testosterone prescriptions for which the template was designed. Most men excluded were already taking testosterone.

Conclusions

The implementation of a CPRS-based TOT improved adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis, evaluation, and counseling of patients with hypogonadism before starting TRT. While there were improvements in adherence with the TOT, the relatively low proportion of patients with documentation of TRT risks and benefits and all guideline recommendations highlights the need for additional efforts to further strengthen adherence to guideline recommendations and ensure appropriate evaluation, counseling, and prescribing practices before initiating TRT.

- Layton JB, Li D, Meier CR, et al. Testosterone lab testing and initiation in the United Kingdom and the United States, 2000 to 2011. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:835-842. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-3570

- Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Westra JR, et al. Testosterone prescribing in the United States, 2002-2016. JAMA. 2018;320:200-202. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7999

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Rose AJ. Patterns of testosterone prescription overuse. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24:240-245. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000336

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1995-2010. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2847

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2536-2559. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2354

- Bhasin S, Brito JP, Cunningham GR, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1715-1744. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00229

- Mulhall JP, Trost LW, Brannigan RE, et al. Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2018;200:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2018.03.115

- Muram D, Zhang X, Cui Z, et al. Use of hormone testing for the diagnosis and evaluation of male hypogonadism and monitoring of testosterone therapy: application of hormone testing guideline recommendations in clinical practice. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1886-1894. doi:10.1111/jsm.12968

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, et al. Ascertainment of testosterone prescribing practices in the VA. Med Care. 2015;53:746-752. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000398?

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, et al. Who gets testosterone? Patient characteristics associated with testosterone prescribing in the Veteran Affairs system: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:304-311. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3940-7

- Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:109-122. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1000485

- Vigen R, O’Donnell CI, Barón AE, et al. Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels. JAMA. 2013;310:1829-1836. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280386

- Finkle WD, Greenland S, Ridgeway GK, et al. Increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction following testosterone therapy prescription in men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85805. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085805

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA cautions about using testosterone products for low testosterone due to aging; requires labeling change to inform of possible increased risk of heart attack and stroke with use. FDA.gov. March 3, 2015. Updated February 28, 2025. Accessed July 8, 2025. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm436259.htm

- US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Healthcare inspection – testosterone replacement therapy initiation and follow-up evaluation in VA male patients. April 11, 2018. Accessed July 8, 2025. https://www.vaoig.gov/reports/national-healthcare-review/healthcare-inspection-testosterone-replacement-therapy

- Narla R, Mobley D, Nguyen EHK, et al. Preliminary evaluation of an order template to improve diagnosis and testosterone therapy of hypogonadism in veterans. Fed Pract. 2021;38:121-127. doi:10.12788/fp.0103

- Bhasin S, Travison TG, Pencina KM, et al. Prostate safety events during testosterone replacement therapy in men with hypogonadism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2348692. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.48692

- Dubin JM, Jesse E, Fantus RJ, et al. Guideline-discordant care among direct-to-consumer testosterone therapy platforms. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:1321-1323. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4928

- Baillargeon J, Urban RJ, Ottenbacher KJ, et al. Trends in androgen prescribing in the United States, 2001 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1465-1466. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6895

- Locke JA, Flannigan R, Günther OP, et al. Testosterone therapy: prescribing and monitoring patterns of practice in British Columbia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2021;15:e110-e117. doi:10.5489/cuaj.6586

- Lincoff AM, Bhasin S, Flevaris P, et al. Cardiovascular safety of testosterone-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:107-117. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2215025

- Layton JB, Li D, Meier CR, et al. Testosterone lab testing and initiation in the United Kingdom and the United States, 2000 to 2011. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:835-842. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-3570

- Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Westra JR, et al. Testosterone prescribing in the United States, 2002-2016. JAMA. 2018;320:200-202. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7999

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Rose AJ. Patterns of testosterone prescription overuse. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24:240-245. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000336

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1995-2010. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2847

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2536-2559. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2354

- Bhasin S, Brito JP, Cunningham GR, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1715-1744. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00229

- Mulhall JP, Trost LW, Brannigan RE, et al. Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2018;200:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2018.03.115

- Muram D, Zhang X, Cui Z, et al. Use of hormone testing for the diagnosis and evaluation of male hypogonadism and monitoring of testosterone therapy: application of hormone testing guideline recommendations in clinical practice. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1886-1894. doi:10.1111/jsm.12968

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, et al. Ascertainment of testosterone prescribing practices in the VA. Med Care. 2015;53:746-752. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000398?

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, et al. Who gets testosterone? Patient characteristics associated with testosterone prescribing in the Veteran Affairs system: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:304-311. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3940-7

- Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:109-122. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1000485

- Vigen R, O’Donnell CI, Barón AE, et al. Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels. JAMA. 2013;310:1829-1836. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280386

- Finkle WD, Greenland S, Ridgeway GK, et al. Increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction following testosterone therapy prescription in men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85805. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085805

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA cautions about using testosterone products for low testosterone due to aging; requires labeling change to inform of possible increased risk of heart attack and stroke with use. FDA.gov. March 3, 2015. Updated February 28, 2025. Accessed July 8, 2025. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm436259.htm

- US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Healthcare inspection – testosterone replacement therapy initiation and follow-up evaluation in VA male patients. April 11, 2018. Accessed July 8, 2025. https://www.vaoig.gov/reports/national-healthcare-review/healthcare-inspection-testosterone-replacement-therapy

- Narla R, Mobley D, Nguyen EHK, et al. Preliminary evaluation of an order template to improve diagnosis and testosterone therapy of hypogonadism in veterans. Fed Pract. 2021;38:121-127. doi:10.12788/fp.0103

- Bhasin S, Travison TG, Pencina KM, et al. Prostate safety events during testosterone replacement therapy in men with hypogonadism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2348692. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.48692

- Dubin JM, Jesse E, Fantus RJ, et al. Guideline-discordant care among direct-to-consumer testosterone therapy platforms. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:1321-1323. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4928

- Baillargeon J, Urban RJ, Ottenbacher KJ, et al. Trends in androgen prescribing in the United States, 2001 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1465-1466. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6895

- Locke JA, Flannigan R, Günther OP, et al. Testosterone therapy: prescribing and monitoring patterns of practice in British Columbia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2021;15:e110-e117. doi:10.5489/cuaj.6586

- Lincoff AM, Bhasin S, Flevaris P, et al. Cardiovascular safety of testosterone-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:107-117. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2215025

Streamlined Testosterone Order Template to Improve the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypogonadism in Veterans

Streamlined Testosterone Order Template to Improve the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypogonadism in Veterans

Around 5% of US Population Diagnosed With Autoimmune Disease

TOPLINE:

In 2022, autoimmune diseases affected over 15 million individuals in the United States, with women nearly twice as likely to be affected as men and more than one third of affected individuals having more than one autoimmune condition.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used electronic health record (EHR) data from six healthcare systems in the United States between 2011 and 2022 to estimate the prevalence of autoimmune diseases according to sex and age.

- They selected 105 autoimmune diseases from the textbook The Autoimmune Diseases and estimated their prevalence in more than 10 million individuals from these healthcare systems; these statistics were subsequently extrapolated to an estimated US population of 333.3 million.

- An individual was considered to have a diagnosis of an autoimmune disease if they had at least two diagnosis codes for the condition, with the codes being at least 30 days apart.

- A software program was developed to compute the prevalence of autoimmune diseases alone and in aggregate, enabling other researchers to replicate or modify the analysis over time.

TAKEAWAY:

- More than 15 million people, accounting for 4.6% of the US population, were diagnosed with at least one autoimmune disease from January 2011 to June 2022; 34% were diagnosed with more than one autoimmune disease.

- Sex-stratified analysis revealed that 63% of patients diagnosed with autoimmune disease were women, and only 37% were men, establishing a female-to-male ratio of 1.7:1; age-stratified analysis revealed increasing prevalence of autoimmune conditions with age, peaking in individuals aged ≥ 65 years.

- Among individuals with autoimmune diseases, 65% of patients had one condition, whereas 24% had two, 8% had three, and 2% had four or more autoimmune diseases (does not add to 100% due to rounding).