User login

2015 Update on contraception

Unintended pregnancy remains a serious problem in the United States, and the rate continues to increase. Currently, the unintended pregnancy rate is at an all-time high, estimated at 51% of all pregnancies.1 Sobering statistics reveal that the United States has a significantly higher rate of unintended pregnancy than any other developed country.2,3

So the question remains: If we have been introducing new contraceptive methods, why do unintended pregnancy rates keep rising in the United States?

The answer: Key barriers prevent women from attaining their desired contraceptive—foremost among them, cost.

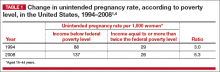

The unintended pregnancy rate is highest among women who are poor, young (aged 18–24 years), minorities, or cohabitating.1 The unintended pregnancy rate among poor women (income below the federal poverty level) of reproductive age has increased over the past few decades, whereas the rate among high-income women (more than twice the federal poverty level) has declined.1 The unintended pregnancy rate discrepancy between poor women and those with means has increased 77%, from a threefold difference in 1995 to a difference of more than fivefold in 2008 (TABLE 1).1,4

These data indicate that we are doing well providing contraception to women of means. However, as a society, we need to improve how we deliver contraceptives—especially highly effective methods—to poor women. As one might expect, given these numbers, low-income women have rates of abortion and unplanned birth that are nearly 6 times higher than their higher-income counterparts.1 The resultant cost to society is substantial, with 68% of unplanned births paid for by public insurance programs such as Medicaid, compared with 38% of planned births.5

As women’s health providers, we must work to improve these numbers and advocate for our patients to help them gain access to the contraceptives they need in accordance with their reproductive life plan. In this article, we hope to put this information in context as we:

- review reports and studies that evaluatethe trend of unintended pregnancy

- describe one state initiative that reduced the rates of unintended pregnancy, birth, and abortion

- introduce a new, highly effective levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Liletta) being marketed with the goal of reaching women who receive care from private physicians as well as public health clinics.

National and state snapshots reveal shifting proportions of intended, unintended pregnancies

Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):s43–s48.

Kost K. Unintended pregnancy rates at the state level: estimates for 2010 and trends since 2002. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/StateUP10.pdf. Published January 2015. Accessed June 29, 2015.

Recent studies have demonstrated trends in unplanned pregnancy over the past 2 decades on both a national and statewide level. Data from the National Survey of Family Growth have highlighted trends in abortion and miscarriage, and data from the National Center for Health Statistics have shed light on birth trends. Of 6 million births in 2008, 51% were unintended.1 Unintended pregnancy was defined as a gestation that was mistimed or unwanted. Intended pregnancy was defined as one that was desired at the time it occurred or sooner.

2008 data focus on the national level

Although the overall pregnancy rate for US women aged 15 to 44 years is relatively unchanged, there is a small change in whether or not the pregnancy was intended. For 2008, as the rate of intended pregnancy dropped slightly, from 54 to 51 pregnancies per 1,000 women, the unintended pregnancy rate increased by 10%, from 49 to 54 pregnancies per 1,000 women. Proportionally, unintended pregnancies that resulted in abortion declined from 47% to 40%, whereas the rate of unintended pregnancies ending in birth increased to 27 births per 1,000 women.1

2010 data focus on individual states

We now have state-specific data on trends in unintended pregnancy rates from 2002 to 2010 in the United States.6 In 28 of 50 states, more than half of all pregnancies were unintended, with rates ranging from 36% to 62%. The median rate was 47 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44, with the lowest unintended pregnancy rate in New Hampshire at 32 per 1,000 women and highest rates in Delaware, Hawaii, and New York at 61 to 62 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women.6

Between 2002 and 2010, unintended pregnancy rates fell 5% or more in 18 states and rose 5% or more in 4 states. In the remaining 12 states for which there are data, unintended pregnancy rates remained unchanged.

Interestingly, 16 states had increases in unintended pregnancy rates of 5% or more between 2002 and 2006. The trend reversed between 2006 and 2010, during which 28 of 41 states with available data experienced decreases of 5% or more and only 1 state experienced an increase of 5% or more. These latest numbers suggest we may be making some progress in reducing the overall rate of unintended pregnancy.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Although the rate of unintended pregnancy is declining in some states, the national rate is still increasing. This information emphasizes the need for all providers to consider initiating discussions about pregnancy intentions—a step that may be as important as obtaining blood pressure and weight. When women are seen for any health visit, they should be asked about their reproductive plans. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued a helpful set of questions to guide the discussion of timing and planning pregnancy. It also provides useful information on ways to increase utilization of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) to help realize the goal of fewer unintended pregnancies. (For more on this discussion, see “How to motivate your patient to create a reproductive life plan,” below.)

How to motivate your patient to create a reproductive life plan

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers a tool for health care professionals to use to encourage patients to think about their reproductive goals and make a plan to facilitate those goals. It’s available at: http://www.cdc.gov/preconception/documents/rlphealthproviders.pdf.

Questions to ask your patient

- Do you plan to have any (more) children at any time in your future?

IF YES

- How many children would you like to have?

- How long would you like to wait until you or your partner become pregnant?

- What family planning method do you plan to use until you or your partner are ready to become pregnant?

- How sure are you that you will be able to use this method without any problems?

IF NO

- What family planning method will you use to avoid pregnancy?

- How sure are you that you will be able to use this method without any problems?

- People’s plans change. Is it possible that you or your partner could ever decide to become pregnant?

Action plan

Encourage your patient to make a plan and take action. Remind her that the plan doesn’t have to be set in stone.

How Colorado broke down barriers to highly effective contraception—and saved $42.5 million in 1 year

Ricketts S, Klinger G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline of births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132.

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project in St. Louis County, Missouri, is an incredible success story. In it, clinicians made highly effective LARCs readily available and free of charge. When a large percentage of women chose a LARC method, the unintended pregnancy and abortion rates declined.7 In Colorado, providers put this study into practice, creating a successful statewide initiative to reduce the unintended pregnancy rate.8

The data behind LARC methods

LARC methods are backed by endorsements from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the CDC, and the World Health Organization, which recommend them for adolescents because of their superiority to shorter-acting methods. With LARCs, failure rates are lower and compliance is greater, making them ideal for adolescents, who have high unintended pregnancy rates.1

However, based on 2011 data, only 2% of LARC users nationwide are aged 20 or younger. A number of barriers prevent young women from obtaining LARCs, including lack of education, limited access to and availability of the contraceptives, and, importantly, cost. Many state plans have adopted Medicaid expansions to reduce barriers to LARCs. However, this benefit is still not available in many states, Colorado being 1 of them.

How the Colorado initiative worked

In 2005, 40% of Colorado’s births were unintended, and 60% of those unintended births occurred in women aged 15 to 24 years. About three-quarters of women who were using a contraceptive method at the time of unintended pregnancy reported that it was a low-cost, high-failure method such as condoms or withdrawal.

In response, Colorado’s Department of Public Health and Environment and the Colorado Family Planning Initiative (CFPI) used private funds from an anonymous foundation to provide LARC products at no cost to the Title X–funded clinics in the state.

The initiative began in 2009 in clinics that served 95% of the state’s total population. The funding provided the products themselves (intrauterine device [IUD], implant), as well as training for providers and staff.

Before the initiative began, 52,645 clients received services in these clinics annually. In the third year of the initiative, that number had increased to 64,928 annually. About 55% of clients receiving services both preinitiative and postinitiative were younger than 25 years, and most (92% in 2011) had income below the poverty level.

LARC use increased fourfold over the 3 years of the funded program, from less than 4.5% to 19.4% in the third year. Contraceptive implant use increased tenfold, and IUD use increased by almost threefold. At the same time, oral contraceptive use declined 13%. Before the initiative, only 620 young, low-income women used a LARC method; afterward, 8,435 did.

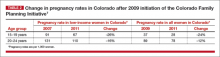

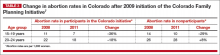

These changes in contraceptive practice triggered a significant decline in pregnancy rates (TABLE 2) and abortion rates (TABLE 3). Abortion rates increased 8% among 20- to 24-year-olds who were not enrolled in the initiative and decreased 18% among those who were. The proportion of high-risk births (births to unmarried, low-income women with less than a high school education) dropped 24% after the initiative began. The proportion of high-risk births in counties not receiving CFPI funds stayed the same at 7%.

Colorado program saved $42.5 million in public funds

This Colorado program demonstrated that the CHOICE Project can be translated to a statewide initiative. Whereas CHOICE enrolled 9,256 women over 4 years, the Colorado initiative included more than 50,000 clients annually over 3 years. Colorado did not use any state funds for this project, which resulted in significant decreases in the unintended birth rate, abortion rate, and rate of high-risk births.

The Colorado governor’s office estimates that the CFPI saved $5.68 in Medicaid costs for Colorado for every dollar spent on contraceptives. In just 1 year (2010), the program saved approximately $42.5 million in public funds.

Ironically, despite the success of this project, the Colorado legislature denied further funding once the initial financial support ceased.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The Colorado program demonstrates that we all can provide LARC methods in practice, especially to young women. In this population, use of highly effective contraception resulted in fewer unintended pregnancies, births, and abortions statewide.

We also need to advocate for our patients, particularly those who have less means and rely on public assistance. Public funding of LARC methods clearly improves outcomes at an individual and population level.

A new, more affordable IUD enters the market

Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, Teal SB, Westhoff CL, Creinin MD. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

Programs such as the Contraceptive CHOICE Project and the Colorado Family Planning Initiative relied on private foundations for financial support, largely because of the high cost of the IUDs and implants currently available in the United States. Even with the Affordable Care Act (ACA) reducing the costs of LARC products and other contraceptives for patients, there are still many women not covered by these programs. For example, “grandfathered” health insurance plans do not need to follow some aspects of the ACA.

Just as important, the high cost of LARC products takes a toll on providers and clinics that must finance the cost per unit to have stock on hand and then wait for months for reimbursement by insurance companies. As a result, some providers do not stock IUDs and implants and only order them as they are needed and approved by insurance for a particular patient. These barriers limit access to LARC methods and reduce the number of women who receive the products.8

Liletta is less expensive than other IUDs

Enter Liletta, a new levonorgestrel-releasing, 52-mg intrauterine system (IUS) that has been in clinical trials since 2009.9 ACCESS IUS (A Comprehensive Contraceptive Efficacy and Safety Study of an Intrauterine System) was initiated by Medicines360, a unique nonprofit pharmaceutical company committed to ensuring access to reproductive health products for all women (private and public sector).

ACCESS IUS is the largest IUD approval study ever performed exclusively in the United States. The Phase 3, open-label clinical trial was conducted at 29 sites around the United States, enrolling healthy, nonpregnant, sexually active women aged 16 to 45 years with regular menstrual cycles. Both nulliparous and parous women were included, with no weight or body mass index (BMI) restrictions applied. The study is ongoing and will continue for as long as 7 years. Eisenberg and colleagues published the data used for initial approval for 3 years of use in the United States and Europe.9

Details of the trial

A total of 1,600 women aged 16 to 35 years comprised the group in which efficacy was evaluated. An additional 151 women aged 36 to 45 years were evaluated for safety only. Of the enrolled women, 1,011 (58%) were nulliparous, making ACCESS IUS the largest product approval study of nulliparous women. In addition, 438 women (25.1%) were obese, and 5% of these women had a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2.

Liletta was placed successfully in 1,714 women (97.9%). Fifteen women did not have placement attempted due to uterine factors (the uterus could not be sounded, or the sound was <5.5 cm) or factors unrelated to the product or inserter. In women in whom placement was attempted, the success rate was 98.7%.

The first-year Pearl index for Liletta was 0.15. Life-table pregnancy rates were 0.14 through year 1 and 0.55 through year 3. Four of the 6 pregnancies reported through 3 years of use were ectopic. Adverse events and their incidence, occurring in more than 2% of users, were acne (6%), expulsion (3.5%), dyspareunia (2.8%), and mastalgia (2.0%). The most common adverse events leading to discontinuation were expulsion (3.5%), bleeding complaints (1.5%), acne (1.3%), and mood swings (1.3%).

Uterine perforation with Liletta was diagnosed in 2 participants (0.11%). Expulsion occurred in 62 users (3.5%) and was more frequent among parous than nulliparous women (5.6% vs 2.0%, respectively; P<.001). Most (80.6%) of the expulsions were reported in the first year of product use. Pelvic infection was reported in 10 participants (0.6%), and all cases resolved with outpatient antibiotic treatment.9

Keep in mind that this is an ongoing study—not all women have reached a full 3 years of use. Updates on efficacy and adverse events will be published in the future. This current publication demonstrates the high efficacy and safety of the product through 3 years of use, permitting its approval for contraception in the United States.

In Europe, the product is approved for both contraception and the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding, based on a European study.10

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Liletta is a branded product (not generic) designed to be similar to Mirena, with the same size, frame, hormone content, and hormone release rate.11 Medicines360 has entered a groundbreaking marketing partnership with Actavis to make Liletta widely available and affordable. For most public sector providers and clinics in the United States, Liletta costs only $50, significantly less than other LARC methods available in the United States. Actavis also has a program that ensures that any woman lacking insurance coverage for an IUD and not receiving care at a public sector clinic will not be charged more than $75 for her IUD. However, the price of the device is only one aspect of its overall cost, as women still need to pay for any office visit or insertion fees.

For society, this unique business partnership has to include providers and patients as well. Sales of Liletta in the private sector will support the very low price in the public sector. As a health care community, even if we do not directly care for women in public-sector settings, we can all help poor women access very affordable highly effective contraception.

For providers, Liletta is a lower-cost alternative to currently available hormonal IUDs and should perform well over the long term. The highly successful use of Liletta in nulliparous women demonstrates its safety in this population. The 3-year approval is the first step, as the Phase 3 study continues. In the future, Liletta is expected to be approved for 5 years or longer.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):s43–s48.

2. Guttmacher Institute. Fact Sheet: Unintended Pregnancy in the United States. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/FB-Unintended-Pregnancy-US.html. Published February 2015. Accessed June 29, 2015.

3. Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(4):241–250.

4. Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Fam Plann Perspectives. 1998;30(1):24–29, 46.

5. Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care. National and States Estimates for 2010. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/public-costs-of-UP-2010.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed June 29, 2015.

6. Kost K. Unintended pregnancy rates at the state level: estimates for 2010 and trends since 2002. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/StateUP10.pdf. Published January 2015. Accessed June 30, 2015.

7. Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Madden T, Peipert JF. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the ContraceptiveCHOICE Project in review. J Womens Health. 2015; 24(5):349–353.

8. Ricketts S, Klinger G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline of births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132.

9. Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, Teal SB, Westhoff CL, Creinin MD. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

10. Mawet M, Nollevaux F, Nizet D, et al. Impact of a new levonorgestrel intrauterine system, Levosert, on heavy menstrual bleeding: results of a one-year randomised controlled trial. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2014;19(3):169–179.

11. Gopalakrishnan M, Liu T, Gobburu J, Creinin MD. Levonorgestrel release rates with LNG20, a new levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(suppl 1): 62S–63S.

Unintended pregnancy remains a serious problem in the United States, and the rate continues to increase. Currently, the unintended pregnancy rate is at an all-time high, estimated at 51% of all pregnancies.1 Sobering statistics reveal that the United States has a significantly higher rate of unintended pregnancy than any other developed country.2,3

So the question remains: If we have been introducing new contraceptive methods, why do unintended pregnancy rates keep rising in the United States?

The answer: Key barriers prevent women from attaining their desired contraceptive—foremost among them, cost.

The unintended pregnancy rate is highest among women who are poor, young (aged 18–24 years), minorities, or cohabitating.1 The unintended pregnancy rate among poor women (income below the federal poverty level) of reproductive age has increased over the past few decades, whereas the rate among high-income women (more than twice the federal poverty level) has declined.1 The unintended pregnancy rate discrepancy between poor women and those with means has increased 77%, from a threefold difference in 1995 to a difference of more than fivefold in 2008 (TABLE 1).1,4

These data indicate that we are doing well providing contraception to women of means. However, as a society, we need to improve how we deliver contraceptives—especially highly effective methods—to poor women. As one might expect, given these numbers, low-income women have rates of abortion and unplanned birth that are nearly 6 times higher than their higher-income counterparts.1 The resultant cost to society is substantial, with 68% of unplanned births paid for by public insurance programs such as Medicaid, compared with 38% of planned births.5

As women’s health providers, we must work to improve these numbers and advocate for our patients to help them gain access to the contraceptives they need in accordance with their reproductive life plan. In this article, we hope to put this information in context as we:

- review reports and studies that evaluatethe trend of unintended pregnancy

- describe one state initiative that reduced the rates of unintended pregnancy, birth, and abortion

- introduce a new, highly effective levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Liletta) being marketed with the goal of reaching women who receive care from private physicians as well as public health clinics.

National and state snapshots reveal shifting proportions of intended, unintended pregnancies

Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):s43–s48.

Kost K. Unintended pregnancy rates at the state level: estimates for 2010 and trends since 2002. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/StateUP10.pdf. Published January 2015. Accessed June 29, 2015.

Recent studies have demonstrated trends in unplanned pregnancy over the past 2 decades on both a national and statewide level. Data from the National Survey of Family Growth have highlighted trends in abortion and miscarriage, and data from the National Center for Health Statistics have shed light on birth trends. Of 6 million births in 2008, 51% were unintended.1 Unintended pregnancy was defined as a gestation that was mistimed or unwanted. Intended pregnancy was defined as one that was desired at the time it occurred or sooner.

2008 data focus on the national level

Although the overall pregnancy rate for US women aged 15 to 44 years is relatively unchanged, there is a small change in whether or not the pregnancy was intended. For 2008, as the rate of intended pregnancy dropped slightly, from 54 to 51 pregnancies per 1,000 women, the unintended pregnancy rate increased by 10%, from 49 to 54 pregnancies per 1,000 women. Proportionally, unintended pregnancies that resulted in abortion declined from 47% to 40%, whereas the rate of unintended pregnancies ending in birth increased to 27 births per 1,000 women.1

2010 data focus on individual states

We now have state-specific data on trends in unintended pregnancy rates from 2002 to 2010 in the United States.6 In 28 of 50 states, more than half of all pregnancies were unintended, with rates ranging from 36% to 62%. The median rate was 47 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44, with the lowest unintended pregnancy rate in New Hampshire at 32 per 1,000 women and highest rates in Delaware, Hawaii, and New York at 61 to 62 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women.6

Between 2002 and 2010, unintended pregnancy rates fell 5% or more in 18 states and rose 5% or more in 4 states. In the remaining 12 states for which there are data, unintended pregnancy rates remained unchanged.

Interestingly, 16 states had increases in unintended pregnancy rates of 5% or more between 2002 and 2006. The trend reversed between 2006 and 2010, during which 28 of 41 states with available data experienced decreases of 5% or more and only 1 state experienced an increase of 5% or more. These latest numbers suggest we may be making some progress in reducing the overall rate of unintended pregnancy.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Although the rate of unintended pregnancy is declining in some states, the national rate is still increasing. This information emphasizes the need for all providers to consider initiating discussions about pregnancy intentions—a step that may be as important as obtaining blood pressure and weight. When women are seen for any health visit, they should be asked about their reproductive plans. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued a helpful set of questions to guide the discussion of timing and planning pregnancy. It also provides useful information on ways to increase utilization of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) to help realize the goal of fewer unintended pregnancies. (For more on this discussion, see “How to motivate your patient to create a reproductive life plan,” below.)

How to motivate your patient to create a reproductive life plan

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers a tool for health care professionals to use to encourage patients to think about their reproductive goals and make a plan to facilitate those goals. It’s available at: http://www.cdc.gov/preconception/documents/rlphealthproviders.pdf.

Questions to ask your patient

- Do you plan to have any (more) children at any time in your future?

IF YES

- How many children would you like to have?

- How long would you like to wait until you or your partner become pregnant?

- What family planning method do you plan to use until you or your partner are ready to become pregnant?

- How sure are you that you will be able to use this method without any problems?

IF NO

- What family planning method will you use to avoid pregnancy?

- How sure are you that you will be able to use this method without any problems?

- People’s plans change. Is it possible that you or your partner could ever decide to become pregnant?

Action plan

Encourage your patient to make a plan and take action. Remind her that the plan doesn’t have to be set in stone.

How Colorado broke down barriers to highly effective contraception—and saved $42.5 million in 1 year

Ricketts S, Klinger G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline of births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132.

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project in St. Louis County, Missouri, is an incredible success story. In it, clinicians made highly effective LARCs readily available and free of charge. When a large percentage of women chose a LARC method, the unintended pregnancy and abortion rates declined.7 In Colorado, providers put this study into practice, creating a successful statewide initiative to reduce the unintended pregnancy rate.8

The data behind LARC methods

LARC methods are backed by endorsements from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the CDC, and the World Health Organization, which recommend them for adolescents because of their superiority to shorter-acting methods. With LARCs, failure rates are lower and compliance is greater, making them ideal for adolescents, who have high unintended pregnancy rates.1

However, based on 2011 data, only 2% of LARC users nationwide are aged 20 or younger. A number of barriers prevent young women from obtaining LARCs, including lack of education, limited access to and availability of the contraceptives, and, importantly, cost. Many state plans have adopted Medicaid expansions to reduce barriers to LARCs. However, this benefit is still not available in many states, Colorado being 1 of them.

How the Colorado initiative worked

In 2005, 40% of Colorado’s births were unintended, and 60% of those unintended births occurred in women aged 15 to 24 years. About three-quarters of women who were using a contraceptive method at the time of unintended pregnancy reported that it was a low-cost, high-failure method such as condoms or withdrawal.

In response, Colorado’s Department of Public Health and Environment and the Colorado Family Planning Initiative (CFPI) used private funds from an anonymous foundation to provide LARC products at no cost to the Title X–funded clinics in the state.

The initiative began in 2009 in clinics that served 95% of the state’s total population. The funding provided the products themselves (intrauterine device [IUD], implant), as well as training for providers and staff.

Before the initiative began, 52,645 clients received services in these clinics annually. In the third year of the initiative, that number had increased to 64,928 annually. About 55% of clients receiving services both preinitiative and postinitiative were younger than 25 years, and most (92% in 2011) had income below the poverty level.

LARC use increased fourfold over the 3 years of the funded program, from less than 4.5% to 19.4% in the third year. Contraceptive implant use increased tenfold, and IUD use increased by almost threefold. At the same time, oral contraceptive use declined 13%. Before the initiative, only 620 young, low-income women used a LARC method; afterward, 8,435 did.

These changes in contraceptive practice triggered a significant decline in pregnancy rates (TABLE 2) and abortion rates (TABLE 3). Abortion rates increased 8% among 20- to 24-year-olds who were not enrolled in the initiative and decreased 18% among those who were. The proportion of high-risk births (births to unmarried, low-income women with less than a high school education) dropped 24% after the initiative began. The proportion of high-risk births in counties not receiving CFPI funds stayed the same at 7%.

Colorado program saved $42.5 million in public funds

This Colorado program demonstrated that the CHOICE Project can be translated to a statewide initiative. Whereas CHOICE enrolled 9,256 women over 4 years, the Colorado initiative included more than 50,000 clients annually over 3 years. Colorado did not use any state funds for this project, which resulted in significant decreases in the unintended birth rate, abortion rate, and rate of high-risk births.

The Colorado governor’s office estimates that the CFPI saved $5.68 in Medicaid costs for Colorado for every dollar spent on contraceptives. In just 1 year (2010), the program saved approximately $42.5 million in public funds.

Ironically, despite the success of this project, the Colorado legislature denied further funding once the initial financial support ceased.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The Colorado program demonstrates that we all can provide LARC methods in practice, especially to young women. In this population, use of highly effective contraception resulted in fewer unintended pregnancies, births, and abortions statewide.

We also need to advocate for our patients, particularly those who have less means and rely on public assistance. Public funding of LARC methods clearly improves outcomes at an individual and population level.

A new, more affordable IUD enters the market

Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, Teal SB, Westhoff CL, Creinin MD. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

Programs such as the Contraceptive CHOICE Project and the Colorado Family Planning Initiative relied on private foundations for financial support, largely because of the high cost of the IUDs and implants currently available in the United States. Even with the Affordable Care Act (ACA) reducing the costs of LARC products and other contraceptives for patients, there are still many women not covered by these programs. For example, “grandfathered” health insurance plans do not need to follow some aspects of the ACA.

Just as important, the high cost of LARC products takes a toll on providers and clinics that must finance the cost per unit to have stock on hand and then wait for months for reimbursement by insurance companies. As a result, some providers do not stock IUDs and implants and only order them as they are needed and approved by insurance for a particular patient. These barriers limit access to LARC methods and reduce the number of women who receive the products.8

Liletta is less expensive than other IUDs

Enter Liletta, a new levonorgestrel-releasing, 52-mg intrauterine system (IUS) that has been in clinical trials since 2009.9 ACCESS IUS (A Comprehensive Contraceptive Efficacy and Safety Study of an Intrauterine System) was initiated by Medicines360, a unique nonprofit pharmaceutical company committed to ensuring access to reproductive health products for all women (private and public sector).

ACCESS IUS is the largest IUD approval study ever performed exclusively in the United States. The Phase 3, open-label clinical trial was conducted at 29 sites around the United States, enrolling healthy, nonpregnant, sexually active women aged 16 to 45 years with regular menstrual cycles. Both nulliparous and parous women were included, with no weight or body mass index (BMI) restrictions applied. The study is ongoing and will continue for as long as 7 years. Eisenberg and colleagues published the data used for initial approval for 3 years of use in the United States and Europe.9

Details of the trial

A total of 1,600 women aged 16 to 35 years comprised the group in which efficacy was evaluated. An additional 151 women aged 36 to 45 years were evaluated for safety only. Of the enrolled women, 1,011 (58%) were nulliparous, making ACCESS IUS the largest product approval study of nulliparous women. In addition, 438 women (25.1%) were obese, and 5% of these women had a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2.

Liletta was placed successfully in 1,714 women (97.9%). Fifteen women did not have placement attempted due to uterine factors (the uterus could not be sounded, or the sound was <5.5 cm) or factors unrelated to the product or inserter. In women in whom placement was attempted, the success rate was 98.7%.

The first-year Pearl index for Liletta was 0.15. Life-table pregnancy rates were 0.14 through year 1 and 0.55 through year 3. Four of the 6 pregnancies reported through 3 years of use were ectopic. Adverse events and their incidence, occurring in more than 2% of users, were acne (6%), expulsion (3.5%), dyspareunia (2.8%), and mastalgia (2.0%). The most common adverse events leading to discontinuation were expulsion (3.5%), bleeding complaints (1.5%), acne (1.3%), and mood swings (1.3%).

Uterine perforation with Liletta was diagnosed in 2 participants (0.11%). Expulsion occurred in 62 users (3.5%) and was more frequent among parous than nulliparous women (5.6% vs 2.0%, respectively; P<.001). Most (80.6%) of the expulsions were reported in the first year of product use. Pelvic infection was reported in 10 participants (0.6%), and all cases resolved with outpatient antibiotic treatment.9

Keep in mind that this is an ongoing study—not all women have reached a full 3 years of use. Updates on efficacy and adverse events will be published in the future. This current publication demonstrates the high efficacy and safety of the product through 3 years of use, permitting its approval for contraception in the United States.

In Europe, the product is approved for both contraception and the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding, based on a European study.10

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Liletta is a branded product (not generic) designed to be similar to Mirena, with the same size, frame, hormone content, and hormone release rate.11 Medicines360 has entered a groundbreaking marketing partnership with Actavis to make Liletta widely available and affordable. For most public sector providers and clinics in the United States, Liletta costs only $50, significantly less than other LARC methods available in the United States. Actavis also has a program that ensures that any woman lacking insurance coverage for an IUD and not receiving care at a public sector clinic will not be charged more than $75 for her IUD. However, the price of the device is only one aspect of its overall cost, as women still need to pay for any office visit or insertion fees.

For society, this unique business partnership has to include providers and patients as well. Sales of Liletta in the private sector will support the very low price in the public sector. As a health care community, even if we do not directly care for women in public-sector settings, we can all help poor women access very affordable highly effective contraception.

For providers, Liletta is a lower-cost alternative to currently available hormonal IUDs and should perform well over the long term. The highly successful use of Liletta in nulliparous women demonstrates its safety in this population. The 3-year approval is the first step, as the Phase 3 study continues. In the future, Liletta is expected to be approved for 5 years or longer.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Unintended pregnancy remains a serious problem in the United States, and the rate continues to increase. Currently, the unintended pregnancy rate is at an all-time high, estimated at 51% of all pregnancies.1 Sobering statistics reveal that the United States has a significantly higher rate of unintended pregnancy than any other developed country.2,3

So the question remains: If we have been introducing new contraceptive methods, why do unintended pregnancy rates keep rising in the United States?

The answer: Key barriers prevent women from attaining their desired contraceptive—foremost among them, cost.

The unintended pregnancy rate is highest among women who are poor, young (aged 18–24 years), minorities, or cohabitating.1 The unintended pregnancy rate among poor women (income below the federal poverty level) of reproductive age has increased over the past few decades, whereas the rate among high-income women (more than twice the federal poverty level) has declined.1 The unintended pregnancy rate discrepancy between poor women and those with means has increased 77%, from a threefold difference in 1995 to a difference of more than fivefold in 2008 (TABLE 1).1,4

These data indicate that we are doing well providing contraception to women of means. However, as a society, we need to improve how we deliver contraceptives—especially highly effective methods—to poor women. As one might expect, given these numbers, low-income women have rates of abortion and unplanned birth that are nearly 6 times higher than their higher-income counterparts.1 The resultant cost to society is substantial, with 68% of unplanned births paid for by public insurance programs such as Medicaid, compared with 38% of planned births.5

As women’s health providers, we must work to improve these numbers and advocate for our patients to help them gain access to the contraceptives they need in accordance with their reproductive life plan. In this article, we hope to put this information in context as we:

- review reports and studies that evaluatethe trend of unintended pregnancy

- describe one state initiative that reduced the rates of unintended pregnancy, birth, and abortion

- introduce a new, highly effective levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Liletta) being marketed with the goal of reaching women who receive care from private physicians as well as public health clinics.

National and state snapshots reveal shifting proportions of intended, unintended pregnancies

Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):s43–s48.

Kost K. Unintended pregnancy rates at the state level: estimates for 2010 and trends since 2002. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/StateUP10.pdf. Published January 2015. Accessed June 29, 2015.

Recent studies have demonstrated trends in unplanned pregnancy over the past 2 decades on both a national and statewide level. Data from the National Survey of Family Growth have highlighted trends in abortion and miscarriage, and data from the National Center for Health Statistics have shed light on birth trends. Of 6 million births in 2008, 51% were unintended.1 Unintended pregnancy was defined as a gestation that was mistimed or unwanted. Intended pregnancy was defined as one that was desired at the time it occurred or sooner.

2008 data focus on the national level

Although the overall pregnancy rate for US women aged 15 to 44 years is relatively unchanged, there is a small change in whether or not the pregnancy was intended. For 2008, as the rate of intended pregnancy dropped slightly, from 54 to 51 pregnancies per 1,000 women, the unintended pregnancy rate increased by 10%, from 49 to 54 pregnancies per 1,000 women. Proportionally, unintended pregnancies that resulted in abortion declined from 47% to 40%, whereas the rate of unintended pregnancies ending in birth increased to 27 births per 1,000 women.1

2010 data focus on individual states

We now have state-specific data on trends in unintended pregnancy rates from 2002 to 2010 in the United States.6 In 28 of 50 states, more than half of all pregnancies were unintended, with rates ranging from 36% to 62%. The median rate was 47 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44, with the lowest unintended pregnancy rate in New Hampshire at 32 per 1,000 women and highest rates in Delaware, Hawaii, and New York at 61 to 62 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women.6

Between 2002 and 2010, unintended pregnancy rates fell 5% or more in 18 states and rose 5% or more in 4 states. In the remaining 12 states for which there are data, unintended pregnancy rates remained unchanged.

Interestingly, 16 states had increases in unintended pregnancy rates of 5% or more between 2002 and 2006. The trend reversed between 2006 and 2010, during which 28 of 41 states with available data experienced decreases of 5% or more and only 1 state experienced an increase of 5% or more. These latest numbers suggest we may be making some progress in reducing the overall rate of unintended pregnancy.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Although the rate of unintended pregnancy is declining in some states, the national rate is still increasing. This information emphasizes the need for all providers to consider initiating discussions about pregnancy intentions—a step that may be as important as obtaining blood pressure and weight. When women are seen for any health visit, they should be asked about their reproductive plans. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued a helpful set of questions to guide the discussion of timing and planning pregnancy. It also provides useful information on ways to increase utilization of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) to help realize the goal of fewer unintended pregnancies. (For more on this discussion, see “How to motivate your patient to create a reproductive life plan,” below.)

How to motivate your patient to create a reproductive life plan

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers a tool for health care professionals to use to encourage patients to think about their reproductive goals and make a plan to facilitate those goals. It’s available at: http://www.cdc.gov/preconception/documents/rlphealthproviders.pdf.

Questions to ask your patient

- Do you plan to have any (more) children at any time in your future?

IF YES

- How many children would you like to have?

- How long would you like to wait until you or your partner become pregnant?

- What family planning method do you plan to use until you or your partner are ready to become pregnant?

- How sure are you that you will be able to use this method without any problems?

IF NO

- What family planning method will you use to avoid pregnancy?

- How sure are you that you will be able to use this method without any problems?

- People’s plans change. Is it possible that you or your partner could ever decide to become pregnant?

Action plan

Encourage your patient to make a plan and take action. Remind her that the plan doesn’t have to be set in stone.

How Colorado broke down barriers to highly effective contraception—and saved $42.5 million in 1 year

Ricketts S, Klinger G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline of births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132.

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project in St. Louis County, Missouri, is an incredible success story. In it, clinicians made highly effective LARCs readily available and free of charge. When a large percentage of women chose a LARC method, the unintended pregnancy and abortion rates declined.7 In Colorado, providers put this study into practice, creating a successful statewide initiative to reduce the unintended pregnancy rate.8

The data behind LARC methods

LARC methods are backed by endorsements from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the CDC, and the World Health Organization, which recommend them for adolescents because of their superiority to shorter-acting methods. With LARCs, failure rates are lower and compliance is greater, making them ideal for adolescents, who have high unintended pregnancy rates.1

However, based on 2011 data, only 2% of LARC users nationwide are aged 20 or younger. A number of barriers prevent young women from obtaining LARCs, including lack of education, limited access to and availability of the contraceptives, and, importantly, cost. Many state plans have adopted Medicaid expansions to reduce barriers to LARCs. However, this benefit is still not available in many states, Colorado being 1 of them.

How the Colorado initiative worked

In 2005, 40% of Colorado’s births were unintended, and 60% of those unintended births occurred in women aged 15 to 24 years. About three-quarters of women who were using a contraceptive method at the time of unintended pregnancy reported that it was a low-cost, high-failure method such as condoms or withdrawal.

In response, Colorado’s Department of Public Health and Environment and the Colorado Family Planning Initiative (CFPI) used private funds from an anonymous foundation to provide LARC products at no cost to the Title X–funded clinics in the state.

The initiative began in 2009 in clinics that served 95% of the state’s total population. The funding provided the products themselves (intrauterine device [IUD], implant), as well as training for providers and staff.

Before the initiative began, 52,645 clients received services in these clinics annually. In the third year of the initiative, that number had increased to 64,928 annually. About 55% of clients receiving services both preinitiative and postinitiative were younger than 25 years, and most (92% in 2011) had income below the poverty level.

LARC use increased fourfold over the 3 years of the funded program, from less than 4.5% to 19.4% in the third year. Contraceptive implant use increased tenfold, and IUD use increased by almost threefold. At the same time, oral contraceptive use declined 13%. Before the initiative, only 620 young, low-income women used a LARC method; afterward, 8,435 did.

These changes in contraceptive practice triggered a significant decline in pregnancy rates (TABLE 2) and abortion rates (TABLE 3). Abortion rates increased 8% among 20- to 24-year-olds who were not enrolled in the initiative and decreased 18% among those who were. The proportion of high-risk births (births to unmarried, low-income women with less than a high school education) dropped 24% after the initiative began. The proportion of high-risk births in counties not receiving CFPI funds stayed the same at 7%.

Colorado program saved $42.5 million in public funds

This Colorado program demonstrated that the CHOICE Project can be translated to a statewide initiative. Whereas CHOICE enrolled 9,256 women over 4 years, the Colorado initiative included more than 50,000 clients annually over 3 years. Colorado did not use any state funds for this project, which resulted in significant decreases in the unintended birth rate, abortion rate, and rate of high-risk births.

The Colorado governor’s office estimates that the CFPI saved $5.68 in Medicaid costs for Colorado for every dollar spent on contraceptives. In just 1 year (2010), the program saved approximately $42.5 million in public funds.

Ironically, despite the success of this project, the Colorado legislature denied further funding once the initial financial support ceased.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The Colorado program demonstrates that we all can provide LARC methods in practice, especially to young women. In this population, use of highly effective contraception resulted in fewer unintended pregnancies, births, and abortions statewide.

We also need to advocate for our patients, particularly those who have less means and rely on public assistance. Public funding of LARC methods clearly improves outcomes at an individual and population level.

A new, more affordable IUD enters the market

Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, Teal SB, Westhoff CL, Creinin MD. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

Programs such as the Contraceptive CHOICE Project and the Colorado Family Planning Initiative relied on private foundations for financial support, largely because of the high cost of the IUDs and implants currently available in the United States. Even with the Affordable Care Act (ACA) reducing the costs of LARC products and other contraceptives for patients, there are still many women not covered by these programs. For example, “grandfathered” health insurance plans do not need to follow some aspects of the ACA.

Just as important, the high cost of LARC products takes a toll on providers and clinics that must finance the cost per unit to have stock on hand and then wait for months for reimbursement by insurance companies. As a result, some providers do not stock IUDs and implants and only order them as they are needed and approved by insurance for a particular patient. These barriers limit access to LARC methods and reduce the number of women who receive the products.8

Liletta is less expensive than other IUDs

Enter Liletta, a new levonorgestrel-releasing, 52-mg intrauterine system (IUS) that has been in clinical trials since 2009.9 ACCESS IUS (A Comprehensive Contraceptive Efficacy and Safety Study of an Intrauterine System) was initiated by Medicines360, a unique nonprofit pharmaceutical company committed to ensuring access to reproductive health products for all women (private and public sector).

ACCESS IUS is the largest IUD approval study ever performed exclusively in the United States. The Phase 3, open-label clinical trial was conducted at 29 sites around the United States, enrolling healthy, nonpregnant, sexually active women aged 16 to 45 years with regular menstrual cycles. Both nulliparous and parous women were included, with no weight or body mass index (BMI) restrictions applied. The study is ongoing and will continue for as long as 7 years. Eisenberg and colleagues published the data used for initial approval for 3 years of use in the United States and Europe.9

Details of the trial

A total of 1,600 women aged 16 to 35 years comprised the group in which efficacy was evaluated. An additional 151 women aged 36 to 45 years were evaluated for safety only. Of the enrolled women, 1,011 (58%) were nulliparous, making ACCESS IUS the largest product approval study of nulliparous women. In addition, 438 women (25.1%) were obese, and 5% of these women had a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2.

Liletta was placed successfully in 1,714 women (97.9%). Fifteen women did not have placement attempted due to uterine factors (the uterus could not be sounded, or the sound was <5.5 cm) or factors unrelated to the product or inserter. In women in whom placement was attempted, the success rate was 98.7%.

The first-year Pearl index for Liletta was 0.15. Life-table pregnancy rates were 0.14 through year 1 and 0.55 through year 3. Four of the 6 pregnancies reported through 3 years of use were ectopic. Adverse events and their incidence, occurring in more than 2% of users, were acne (6%), expulsion (3.5%), dyspareunia (2.8%), and mastalgia (2.0%). The most common adverse events leading to discontinuation were expulsion (3.5%), bleeding complaints (1.5%), acne (1.3%), and mood swings (1.3%).

Uterine perforation with Liletta was diagnosed in 2 participants (0.11%). Expulsion occurred in 62 users (3.5%) and was more frequent among parous than nulliparous women (5.6% vs 2.0%, respectively; P<.001). Most (80.6%) of the expulsions were reported in the first year of product use. Pelvic infection was reported in 10 participants (0.6%), and all cases resolved with outpatient antibiotic treatment.9

Keep in mind that this is an ongoing study—not all women have reached a full 3 years of use. Updates on efficacy and adverse events will be published in the future. This current publication demonstrates the high efficacy and safety of the product through 3 years of use, permitting its approval for contraception in the United States.

In Europe, the product is approved for both contraception and the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding, based on a European study.10

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Liletta is a branded product (not generic) designed to be similar to Mirena, with the same size, frame, hormone content, and hormone release rate.11 Medicines360 has entered a groundbreaking marketing partnership with Actavis to make Liletta widely available and affordable. For most public sector providers and clinics in the United States, Liletta costs only $50, significantly less than other LARC methods available in the United States. Actavis also has a program that ensures that any woman lacking insurance coverage for an IUD and not receiving care at a public sector clinic will not be charged more than $75 for her IUD. However, the price of the device is only one aspect of its overall cost, as women still need to pay for any office visit or insertion fees.

For society, this unique business partnership has to include providers and patients as well. Sales of Liletta in the private sector will support the very low price in the public sector. As a health care community, even if we do not directly care for women in public-sector settings, we can all help poor women access very affordable highly effective contraception.

For providers, Liletta is a lower-cost alternative to currently available hormonal IUDs and should perform well over the long term. The highly successful use of Liletta in nulliparous women demonstrates its safety in this population. The 3-year approval is the first step, as the Phase 3 study continues. In the future, Liletta is expected to be approved for 5 years or longer.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):s43–s48.

2. Guttmacher Institute. Fact Sheet: Unintended Pregnancy in the United States. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/FB-Unintended-Pregnancy-US.html. Published February 2015. Accessed June 29, 2015.

3. Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(4):241–250.

4. Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Fam Plann Perspectives. 1998;30(1):24–29, 46.

5. Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care. National and States Estimates for 2010. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/public-costs-of-UP-2010.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed June 29, 2015.

6. Kost K. Unintended pregnancy rates at the state level: estimates for 2010 and trends since 2002. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/StateUP10.pdf. Published January 2015. Accessed June 30, 2015.

7. Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Madden T, Peipert JF. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the ContraceptiveCHOICE Project in review. J Womens Health. 2015; 24(5):349–353.

8. Ricketts S, Klinger G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline of births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132.

9. Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, Teal SB, Westhoff CL, Creinin MD. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

10. Mawet M, Nollevaux F, Nizet D, et al. Impact of a new levonorgestrel intrauterine system, Levosert, on heavy menstrual bleeding: results of a one-year randomised controlled trial. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2014;19(3):169–179.

11. Gopalakrishnan M, Liu T, Gobburu J, Creinin MD. Levonorgestrel release rates with LNG20, a new levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(suppl 1): 62S–63S.

1. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):s43–s48.

2. Guttmacher Institute. Fact Sheet: Unintended Pregnancy in the United States. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/FB-Unintended-Pregnancy-US.html. Published February 2015. Accessed June 29, 2015.

3. Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(4):241–250.

4. Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Fam Plann Perspectives. 1998;30(1):24–29, 46.

5. Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care. National and States Estimates for 2010. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/public-costs-of-UP-2010.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed June 29, 2015.

6. Kost K. Unintended pregnancy rates at the state level: estimates for 2010 and trends since 2002. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/StateUP10.pdf. Published January 2015. Accessed June 30, 2015.

7. Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Madden T, Peipert JF. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the ContraceptiveCHOICE Project in review. J Womens Health. 2015; 24(5):349–353.

8. Ricketts S, Klinger G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline of births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132.

9. Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, Teal SB, Westhoff CL, Creinin MD. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

10. Mawet M, Nollevaux F, Nizet D, et al. Impact of a new levonorgestrel intrauterine system, Levosert, on heavy menstrual bleeding: results of a one-year randomised controlled trial. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2014;19(3):169–179.

11. Gopalakrishnan M, Liu T, Gobburu J, Creinin MD. Levonorgestrel release rates with LNG20, a new levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(suppl 1): 62S–63S.

In this Article

- How Colorado broke down barriers to highly effective contraception

- How to motivate your patient to create a reproductive life plan

- A more affordable IUD enters the market

2014 Update on Contraception

Unintended pregnancy remains an important public health priority in the United States. Correct and consistent use of effective contraception can help women achieve appropriate interpregnancy intervals and desired family size, whereas inconsistent or non-use of contraceptive methods contributes to the majority of unintended pregnancies.

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, such as implants and intrauterine devices, have effectiveness rates similar to those of permanent sterilization, and these methods are becoming more popular among American women. The proportion of women using LARC methods increased from 2.4% in 2002 to 8.5% in 2009.1

Sterilization continues to be a common method of contraception, with 32% of women relying on female or male sterilization in 2009.1 For women who are not using contraception regularly or who experience a failure in their method, emergency contraception is a viable back-up plan.

In this article, we will review the latest data on contraceptive efficacy in three different contexts:

- implant placement in the immediate postpartum period

- emergency contraception (EC) with the copper intrauterine device (IUD)

- sterilization via hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic approaches.

Immediate postpartum placement of the contraceptive implant saves money

Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):481.e1–e7.

Han L, Teal SB, Sheeder J, Tocce K. Preventing repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Is immediate postpartum insertion of the contraceptive implant cost effective? [published online ahead of print March 11, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.015.

Although teen birth rates have been declining in the United States in recent years, repeat teen births still pose significant health and socioeconomic challenges for young mothers, their children, and society. Adolescent mothers face barriers in completing their education and obtaining work experience. Repeat teen mothers are also more likely to experience adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth or delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. Families of adolescent mothers are not the only ones who are affected by teen childbearing. In fact, US taxpayers spend about $11 billion each year on costs related to teen pregnancy.2

The immediate postpartum period is a time when effective LARC methods can be initiated to decrease the risk of rapid repeat pregnancy.

Details of the study by Tocce and colleagues

Tocce and colleagues report the results of a prospective observational study that compared adolescents who chose postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion with those who elected to use no contraception or initiate contraception at the usual interval (condoms, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills at any time after delivery, combined hormonal contraception after 4 weeks postpartum, implant insertion after 4 weeks postpartum, and intrauterine device placement at 6 weeks after delivery).

Of adolescents who chose immediate postpartum implant placement, 88.6% were still using this method at 12 months postpartum. In comparison, only 53.6% of adolescents in the control group were using a highly effective contraceptive method at 12 months postpartum (TABLE).

| Contraceptive method | Immediate postpartum implant (n = 149) | Control* (n = 166) |

| Implant | 132 (88.6%) | 35 (21.1%) |

| Intrauterine device | 6 (4.0%) | 51 (30.7%) |

| Female sterilization | 0 | 3 (01.8%) |

| Total using highly effective method† | 138 (92.6%) | 89 (53.6%) |

* The control group consisted of women who elected to use no contraception or initiate contraception at the usual postpartum interval (condoms, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills at any time after delivery, combined hormonal contraception after 4 weeks postpartum, implant insertion after 4 weeks postpartum, and intrauterine device placement at 6 weeks after delivery). † P<.0001, Fisher exact test.Adapted from: Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):481.e1–e7. | ||

The difference in repeat pregnancy rates was even more compelling. At 12 months postpartum, the pregnancy rate was 2.6% for women who had chosen an immediate postpartum implant, compared with 18.6% in the control group (P<.001).

One significant barrier to immediate postpartum LARC placement is reimbursement policies; hospitals are reimbursed a single global fee for all of the hospital care, so insertion of an expensive contraceptive implant during the hospital stay is not reimbursed. However, if a woman returns to the office for insertion, the provider receives full reimbursement if she has coverage for the product.

A look at cost effectiveness

With this in mind, Han and colleagues determined the cost effectiveness of immediate postpartum implant placement using the results from the observational study from Tocce et al. The costs of implant insertion and removal were calculated, as well as the costs associated with various obstetric or gynecologic outcomes, including prenatal care, vaginal or cesarean delivery, infant medical care for the first year of life, and management of ectopic pregnancy or spontaneous miscarriage. The contraceptive costs for the comparison group were not included in the analysis because these costs would represent baseline contraceptive costs incurred by Medicaid.

Significant cost savings were found with immediate postpartum implant placement over time; specifically, $0.78, $3.54, and $6.50 were saved for every dollar spent at 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively. To be clear, this analysis was limited to contraceptive implant placement, and cannot be directly applied to immediate postpartum intrauterine device insertion.

What this evidence means for practice

Among adolescents who received immediate postpartum implant placement, contraceptive continuation rates were higher and repeat teen birth rates were lower, translating into overall cost savings for state Medicaid programs. Furthermore, young mothers and their families also experience health, social, and economic benefits from a delay in childbearing.

In accordance with the findings of Han and colleagues, the South Carolina Medicaid program is the first to implement reimbursement for inpatient postpartum LARC insertion. Other states should evaluate their own policies for inpatient LARC reimbursement and take into consideration the potential for cost savings

More evidence suggests the copper IUD is the preferred emergency contraceptive

Turok DK, Jacobson JC, Dermish Amna I, et al. Emergency contraception with a copper IUD or oral levonorgestrel: An observational study of 1-year pregnancy rates. Contraception. 2014;89(3):222–228.

Several options for EC exist, but only the copper IUD also can be continued as an effective method of contraception. Despite its dual roles in pregnancy prevention, the copper IUD remains underutilized, compared with oral EC methods. Women who seek EC are motivated to reduce their risk of pregnancy. However, they may not be receiving the most effective method to avoid pregnancy. A survey of 816 emergency contraception providers revealed that 85% of respondents had never offered the copper IUD as a method of EC to their patients.3 This represents a lost opportunity, as the copper IUD would be ideal for women who desire an effective form of EC that also can be continued as contraception.

Details of the trial

Turok and colleagues conducted a prospective observational trial comparing oral levonorgestrel (LNG) with copper IUD insertion in women seeking EC. Women who were interested in participating received scripted counseling on both methods and were given their desired method free of charge.

In this study, almost 40% (215/542) of women chose the copper IUD for EC. However, the providers in this study were unable to place the IUD in 20% of these women. The women who chose not to receive an IUD or who did not have an IUD placed received LNG EC.

There were four pregnancies from EC failures in the first month in the LNG group, compared with none in the IUD group. After 1 year, the risk of pregnancy in women who chose the copper IUD (including the women who were unable to have the device placed) was lower than in women who chose LNG (odds ratio [OR], 0.50; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26–0.96).

In an analysis based on the actual method received, the risk of pregnancy in the IUD group was even lower (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.18–0.80).

At 1 year, 60% of women in the copper IUD group were using a highly effective method of contraception, specifically an IUD, implant, or sterilization, compared with 10% in the LNG group.

What this evidence means for practice

When given the option, almost 50% of women chose the copper IUD to reduce their risk of pregnancy. Women who received a copper IUD were more likely to be using a highly effective method of contraception and less likely to experience an unintended pregnancy at 1 year than women who chose LNG EC.

We need to counsel our patients on the differences in efficacy between the methods and offer copper IUDs to eligible women.

Hysteroscopic sterilization may not be as effective as we thought

Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Smith KJ, Xu X. Probability of pregnancy after sterilization: A comparison of hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic sterilization [published online ahead of print April 24, 2014]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.03.010.

Since its introduction in 2002, hysteroscopic sterilization has become a popular method of sterilization. It has many potential advantages over laparoscopic sterilization, including the ability to perform the procedure in an office setting without general anesthesia or abdominal incisions. However, there are also disadvantages to hysteroscopic sterilization, as we pointed out in this Update last year, such as a risk of unsuccessful procedure completion on the first attempt and the need for contraception until tubal occlusion is confirmed.

There are limited data on the effectiveness of hysteroscopic sterilization, and there are no prospective studies comparing hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization. Given the rare outcome of unintended pregnancy with both procedures, based on published literature, a prospective study is unfeasible. An inherent weakness of large clinical trials or retrospective reports of hysteroscopic sterilization success is that only women who had successful completion of the procedure can be included. Two recent reports that demonstrate that completed hysteroscopic sterilization procedures are highly effective highlighted this “weakness.”4,5 However, these data do not reflect “real-life” practice; there are no intent-to-treat data on pregnancy rates among women who choose this option but are unable to fully complete the procedure.

Details of the study

To evaluate real-life outcomes, Gariepy and colleagues performed a decision analysis to estimate the probability of pregnancy after hysteroscopic sterilization and laparoscopic approaches with silicone rubber band application and bipolar coagulation. Using a Markov state-transition model, the authors could determine the probability of pregnancy over a 10-year period for all types of sterilization. For hysteroscopic sterilization, each of the multiple steps, from coil placement to use of alternative contraception in the interim period to follow-up confirmation of tubal occlusion, could be included.

At 10 years, the expected cumulative pregnancy rates per 1,000 women were 96, 24, and 30 for hysteroscopic sterilization, laparoscopic silicone rubber band application, and laparoscopic bipolar coagulation, respectively. For hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization to be equal in effectiveness, the success of laparoscopic sterilization would need to decrease to less than 90% from 99% and hysteroscopic coil placement or follow-up would need to improve.

The authors concluded that the effectiveness of sterilization does vary significantly bythe method used, and rankings of effectiveness should differentiate between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization.

What this evidence means for practice

When counseling women about sterilization, we should discuss the advantages and disadvantages of hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic approaches and disclose the efficacy rates of each method.

The issue is not that the hysteroscopic sterilization procedure is less effective than laparoscopic sterilization. The real take-home point is that women choosing to attempt hysteroscopic sterilization are more likely to experience an unintended pregnancy within the next 10 years than women presenting for laparoscopic sterilization.

Each year, 345,000 US women undergo interval sterilization.6 If hysteroscopic sterilization were attempted as the preferred method for all of these women (as compared with laparoscopic sterilization) in just 1 year, then an additional 22,770 pregnancies would occur for this group of women over the ensuing 10 years. With the current technology, hysteroscopic sterilization should be reserved for appropriate candidates, such as women who may face higher risks from laparoscopy.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007-2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(4):893–897.

2. Centers for Disease Control. Vital signs: Repeat births among teens—United States, 2007–2010. MMWR. 2013;62(13):249–255.

3. Harper CC, Speidel JJ, Drey EA, Trussell J, Blum M, Darney PD. Copper intrauterine device for emergency contraception: Clinical practice among contraceptive providers. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 Pt 1):220–226.

4. Munro MG, Nichols JE, Levy B, Vleugels MP, Veersema S. Hysteroscopic sterilization: 10-year retrospective analysis of worldwide pregnancy reports. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(2):245–251.

5. Fernandez H, Legendre G, Blein C, Lamarsalle L, Panel P. Tubal sterilization: Pregnancy rates after hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic sterilization in France, 2006–2010 [published online ahead of print May 14, 2014]. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.04.043.

6. Bartz D, Greenberg JA. Sterilization in the United States. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(1):23–32.

Unintended pregnancy remains an important public health priority in the United States. Correct and consistent use of effective contraception can help women achieve appropriate interpregnancy intervals and desired family size, whereas inconsistent or non-use of contraceptive methods contributes to the majority of unintended pregnancies.

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, such as implants and intrauterine devices, have effectiveness rates similar to those of permanent sterilization, and these methods are becoming more popular among American women. The proportion of women using LARC methods increased from 2.4% in 2002 to 8.5% in 2009.1

Sterilization continues to be a common method of contraception, with 32% of women relying on female or male sterilization in 2009.1 For women who are not using contraception regularly or who experience a failure in their method, emergency contraception is a viable back-up plan.

In this article, we will review the latest data on contraceptive efficacy in three different contexts:

- implant placement in the immediate postpartum period

- emergency contraception (EC) with the copper intrauterine device (IUD)

- sterilization via hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic approaches.

Immediate postpartum placement of the contraceptive implant saves money

Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):481.e1–e7.

Han L, Teal SB, Sheeder J, Tocce K. Preventing repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Is immediate postpartum insertion of the contraceptive implant cost effective? [published online ahead of print March 11, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.015.

Although teen birth rates have been declining in the United States in recent years, repeat teen births still pose significant health and socioeconomic challenges for young mothers, their children, and society. Adolescent mothers face barriers in completing their education and obtaining work experience. Repeat teen mothers are also more likely to experience adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth or delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. Families of adolescent mothers are not the only ones who are affected by teen childbearing. In fact, US taxpayers spend about $11 billion each year on costs related to teen pregnancy.2

The immediate postpartum period is a time when effective LARC methods can be initiated to decrease the risk of rapid repeat pregnancy.