User login

Simple yet thorough office evaluation of pelvic floor disorders

- A voiding diary, stress test, and postvoid residual volume measurement often can provide as much useful information as complex urodynamic investigations.

- In addition to performing the standard gynecologic exam, clinicians should assess patients for evidence of pelvic organ prolapse.

- A lower urinary tract infection can cause urgency, frequency, and nocturia, which can mimic urge incontinence or interstitial cystitis.

- Documentation of the postvoid residual volume is a prerequisite for any incontinence or anterior/apical prolapse procedure, because the clinician will need the information to interpret any postoperative voiding difficulty.

The meticulous evaluation and diagnosis of pelvic floor disorders, critical precursors of treatment, are feasible for any gynecologist—without specialized equipment. A specific history, voiding diary, focused physical exam, and simple office tests provide sufficient data to diagnose most complaints in a single office visit, allowing clinicians to initiate a management plan immediately.

This approach frequently can be carried out without additional studies. In other cases, the evaluation steers the practitioner to the appropriate investigations.

Increasing need for skill in assessing pelvic floor disorders

Although the underlying etiology of pelvic floor disorders is the subject of debate, the increasing demand for management of these problems is not.1 Urinary incontinence is thought to affect 10% to 25% of women 15 to 64 years old, becoming more common with age, although prevalence rates vary considerably according to the definition and survey method used and the population studied.2 A woman’s lifetime risk of undergoing a surgical procedure for prolapse or urinary incontinence is 11.1% by the age of 80.3

As the proportion of postmenopausal women increases over the next 30 years, these conditions will become even more prevalent.1 Thus, the ability to respond appropriately will be a key determinant of a gynecologic practice’s success. Clearly, the need for proper evaluation and diagnosis has never been greater.

How to assess the patient’s history

One way to facilitate a pelvic floor history is to give the patient a detailed questionnaire that can be completed prior to her initial office visit. First, elicit the patient’s main complaint, including its impact on her lifestyle. Other essential components of the pelvic floor history are a description of symptoms and quantification of their duration, frequency, and severity, as well as any previous treatment the patient has undergone.

Evaluate urinary continence. Urinary symptoms range from frequency, nocturia, and urgency to dysuria and hematuria. If the patient does not volunteer a history of urinary incontinence, she should be asked about it. Have her describe any incontinent episodes she has experienced, particularly the frequency and amount of urine lost.

- Urge incontinence, as its name implies, is typically preceded by an urge to void, and can involve a trigger such as running water or cold temperature.

- Stress incontinence generally occurs with sudden movements or increases in intra-abdominal pressure, such as those brought about by coughing, laughing, sneezing, or running.

Estimate urine loss. The severity of a patient’s incontinence can be crudely assessed by the type and quantity of protection used (e.g., maxi pads or panty liners). Evaluate the level of activity needed to provoke an incontinent episode. Incontinence with positional change between lying, sitting, and standing is more severe than occasional incontinence with vigorous exercise. Keep in mind that many women with urinary incontinence have components of both stress and urge loss, otherwise called mixed incontinence.

Look for voiding dysfunction, prolapse. Elicit any symptoms of voiding dysfunction, such as straining, hesitancy, intermittent flow, incomplete emptying, postvoid dribbling, and retention. Symptoms of pelvic-organ prolapse include vaginal pressure or bulging and associated discomfort.

Evaluate bowel function. Include questions about the patient’s bowel function, such as frequency, consistency, and constipation.

- Ask about her use of laxatives or antidiarrheal medications, since these may not be included in her list of medications.

- Also inquire about “splinting”—the use of a finger pressing in the vagina or on the perineum during fecal evacuation—as this can be a sign of posterior prolapse or rectocele.

- Ask specifically about the presence of any anal incontinence, which may involve liquid, gas, or solid stool.

Don’t overlook sexual ramifications. Finally, address the patient’s sexual function, particularly symptoms of discomfort, pain, or incontinence with sexual activity.

Voiding diary

This is an inexpensive way to obtain information about a woman’s daily bladder function. It is completed by the patient over a 24-hour period and includes oral fluid intake, episodes of incontinence, associated activities, and voids (FIGURE 1). Voiding volumes and times are recorded.4 The amount of fluid intake listed on voiding diaries often is surprising and can provide clues to treatment.

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines adult polyuria as more than 2,800 mL (approximately 94 oz) of urine output in 24 hours.4 The voiding diary depicted in FIGURE 1 came from a patient who complained of urinary frequency, nocturia, and rare stress incontinence. It shows that her 24-hour fluid intake was 3,360 mL (112 oz), and her urinary output was 3,720 mL (124 oz). The diary alone reveals that her symptoms are attributable to excessive fluid intake, resulting in polyuria, frequency, and nocturia. This patient experienced symptomatic relief with fluid and methylxanthine reduction.

FIGURE 1Sample voiding diary of a patient with complaints of urinary frequency, nocturia, and rare stress incontinence

This sample diary alone reveals that symptoms were due to excessive fluid and methylxanthine intake. This patient’s symptoms abated with decreased intake of water and tea.

Physical examination

Perform a complete physical exam, focusing attention on elements specific to pelvic floor disorders.

The International Continence Society periodically reports on terminology for the symptoms, signs, and urodynamic observations of pelvic floor disorders.1

| Urinary incontinence | Any involuntary leakage of urine |

| Stress urinary incontinence | Involuntary leakage of urine on effort or exertion |

| Urge urinary incontinence | Involuntary leakage accompanied by or immediately preceded by urgency |

| Urgency | A sudden compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer |

| Mixed urinary incontinence | Involuntary leakage associated with urgency and also with exertion, sneezing, or coughing |

| Anal incontinence | The inability to control passage of flatus or liquid or solid stool |

Stress test. If the patient relates a history of stress incontinence, the condition must be documented before any anti-incontinence procedure is considered. One simple method for this is a stress test.

Ask the patient to present for her office visit with a full bladder, as if she had an ultrasound appointment. At the start of the physical exam, perform the stress test with the patient in a standing position. (The full bladder should reduce false-negative results.)

Have the patient stand with 1 foot on the step of the examination table. Now, sit on a stool and separate the labia with 1 hand, so that the urethral meatus is visible. (A 4×4 gauze in the other hand can absorb any urine that is lost.) Have the patient cough forcefully several times while you observe the meatus for loss of urine. A spurt of urine coincident with the cough is a positive test.

If the patient has a significant amount of prolapse—i.e., stage III or IV)—repeat the stress test with the prolapse reduced to eliminate the effect of any urethral kinking. (The prolapse can be reduced using the posterior blade of a speculum.)

After the stress test, have the patient void in a measured device, such as a toilet hat, to record the voided volume. When she returns to the examination room, obtain a postvoid residual (PVR). The stress-test volume is determined by adding the volume voided to the PVR volume.

Postvoid residual volume. This assessment enables the clinician to determine the bladder’s ability to empty. Physicians can measure residual urine either by catheterization or ultrasound. When using ultrasound, perform transabdominal imaging in the transverse and mid-sagittal planes. Once you have obtained measurements of the bladder’s diameter in 3 planes (anterior-posterior, transverse, and sagittal/longitudinal), you can approximate the volume using this formula:

Volume (mL) = height (cm) × length (cm) × width (cm) × 0.52

If no bladder dimension is greater than 5 cm, the PVR is less than 65 mL.

In our opinion, documentation of the PVR is a prerequisite for any incontinence or anterior/apical prolapse procedure; the clinician will need this information to interpret any postoperative voiding difficulties and to counsel patients at increased risk of such difficulties.

Neurologic examination. Although it is unlikely that significant neurologic disease contributes to the patient’s pelvic floor dysfunction, the ramifications of any disease can be substantial. Thus, perform a focused neurologic exam to evaluate mental status, lower-extremity and perineal sensation, and reflexes. The 2 relevant spinalcord reflexes are the bulbocavernosus and the anal wink.5 Interpret these tests with caution, however, since an anal wink may be absent in some women who are otherwise neurologically normal.6

Simple office tests

POPQ exam. In addition to the standard gynecologic examination, patients complaining of or presenting with prolapse should undergo an objective measurement of the problem: the pelvic organ prolapse quantitative (POPQ) exam.

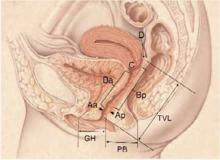

In 1996, the ICS published standardized terminology that has been adopted by most specialty organizations.7 This POPQ system describes the location and severity of prolapse using segments of the vaginal wall and external genitalia, rather than the terms cystocele, rectocele, and enterocele (FIGURE 2).

While the patient is straining, 6 specific sites are evaluated. Measure each site (in centimeters) in relation to the hymenal ring, which is a fixed, easily identified anatomic landmark. The hymenal ring is the zero point of reference. If a site is above the hymen, it is assigned a negative number; if it prolapses below the hymen, the measurement is positive.

In women with stress urinary incontinence, it is important to determine whether urethral hypermobility is present.

Use a Sims speculum or the posterior blade of a bivalve speculum to isolate the different vaginal compartments. An inexpensive disposable wooden spatula (Pap smear stick) marked with centimeters works well as the measuring device.

The 6 POPQ sites are:

- Aa: The point in the midline of the anterior vaginal wall 3 cm proximal to the urethral meatus, corresponding to the urethrovesical junction. By definition, the range of position Aa is -3 to +3.

- Ba: On the anterior vaginal wall, the most dependent position between point Aa and the vaginal cuff or anterior vaginal fornix.

- C: Cervix or vaginal cuff (posthysterectomy).

- D: Posterior fornix corresponding to the pouch of Douglas (this point is omitted in the absence of a cervix).

- Ap: The point in the midline of the posterior vaginal wall 3 cm proximal to the hymenal ring. By definition, the range of position Ap is -3 to +3.

- Bp: On the posterior vaginal wall, the most dependent position between Ap and the vaginal cuff or posterior fornix.

Two additional measurements are made in centimeters while the patient is straining:

- GH: The genital hiatus is measured from the midportion of the urethral meatus to the posterior margin of the genital hiatus.

- PB: The perineal body is measured between the posterior margin of the genital hiatus and the midportion of the anus.

While the patient is not straining, a ninth measurement is made:

- TVL: Total vaginal length is the greatest depth of the vagina.

Staging each compartment. When all 9 of these measurements have been taken, a stage can be assigned to each compartment: anterior, apex (uterine or vault), and posterior. The stages are:

- Stage 0: No prolapse is demonstrated. Points Aa, Ap, Ba, and Bp are all at -3 cm and either point C or point D is within 2 cm of TVL.

- Stage I: The most distal portion of the prolapse is 1 cm above the level of the hymen (above -1).

- Stage II: The most distal portion of the prolapse is 1cm proximal to or distal to the hymen.

- Stage III: The most distal portion of the prolapse is 1 cm below the hymen but protrudes no further than 2 cm less than the total vaginal length.

- Stage IV: Complete eversion is present.

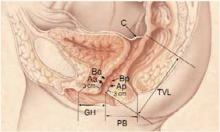

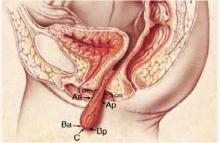

Most parous women are stage I, II, or III. If you remember that stage II is between and including -1 and +1, it follows that stage I is above this and stage III is below this. FIGURE 3 compares POPQ examination findings of normal support and posthysterectomy vaginal eversion.

Assess urethral hypermobility. In women with stress urinary incontinence, it is important to determine whether urethral hypermobility is present, since this finding may influence surgical management.

- Q-tip test. Measure mobility by placing a lubricated sterile cotton swab within the urethra so that the tip of the swab is at the urethrovesical junction. Lubrication with xylocaine gel may reduce the discomfort of this step. Measure the angle between the swab and the horizontal plane with a goniometer both while the patient is not straining and while the patient is straining at maximum. Urethral hypermobility exists if the angle is more than 30° either at rest or with straining.8

- Indications for surgery. Ahypermobile urethra is thought to correlate with decreased support of the urethra and the urethrovesical junction, which has been implicated in the development of stress incontinence. Many surgical interventions for stress incontinence are designed to increase support to this area.

In 1996, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published guidelines for surgery for genuine stress incontinence due to urethral hypermobility in patients without a history of previous antiincontinence surgery.10 These criteria include:

- History and demonstration of stress urinary incontinence

- No significant urge component

- Absence of transient causes of urinary incontinence

- Normal PVR volume

- Normal voiding habits

- Absence of neurologic history or findings

- Absence of pregnancy

- Confirmation that the patient has been counseled regarding more conservative therapy

The office evaluation of pelvic floor disorders outlined in this article meets the ACOG criteria. Of course, consider surgical management only after conservative measures have been exhausted.

Evaluate pelvic floor tone. This portion of the exam assesses the strength of the pelvic-floor musculature. Place 1 or 2 fingers in the vagina and instruct the patient to contract her pelvic floor muscles (i.e., the levator ani muscles). Then gauge her ability to contract these muscles, as well as the strength, symmetry, and duration of the contraction.

The strength of the contraction can be subjectively graded with a modified Oxford scale (0 = no contraction, 1 = flicker, 2 = weak, 3 = moderate, 4 = good, 5 = strong).9

Women with an external anal sphincter defect may lack the normal stellate pattern around the anus anteriorly.

Determine structure and function of the anal sphincter. This is the final part of the physical exam. Women with an external anal sphincter defect may lack the normal stellate pattern around the anus anteriorly because of the absence of contractile tissue. A rectal exam should be performed at rest and with voluntary squeezing of the anal sphincter to assess resting tone and squeeze strength of the anal sphincter muscle complex. In addition, the bulk of this complex can be palpated to determine whether a structural defect is present (usually found anteriorly).

FIGURE 2Quantifying pelvic organ support

Nine sites—points Aa, Ba, C, D, Bp, and Ap; the genital hiatus (GH); the perineal body (PB); and total vaginal length (TVL)—are used to measure pelvic organ support. This drawing represents Stage 0 prolapse, as there is no descent of any of the vaginal compartments. Points Aa and Ap are always measured at the point exactly 3 cm from the reference point of the hymenal ring. Since there is no descent in this example, points Aa and Ap are both -3.

FIGURE 3Posthysterectomy pelvic organ prolapse quantitative (POPQ) examination

POPQ examination for a patient with normal support who has undergone a hysterectomy. When compared to FIGURE 2, notice the absence of point D; point C now represents the vaginal cuff.

POPQ examination for a patient with vault prolapse after a hysterectomy. Notice how points Aa and Ap are now located outside the body, but are still exactly 3 cm from the hymen. The most distal part of the anterior wall (point Ba), the vaginal cuff (point C), and the most dis-tal part of the posterior wall (point Bp) are all at the same position.

Laboratory studies

Initial laboratory studies should include a urine dipstick analysis and possible culture to evaluate for infection or hematuria. A lower urinary tract infection can produce symptoms such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia, which can mimic the presentation of urge incontinence or interstitial cystitis. Hematuria may herald a more worrisome but rare condition such as transitional cell cancer of the bladder.

Indications for urodynamic testing

Although the basic office evaluation outlined here provides adequate information to properly treat most women with urinary incontinence, further evaluation is appropriate in some cases. A thorough discussion of urodynamics is beyond the scope of this article, but it is important to understand when a patient may require additional investigations. In 1996, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research recommended further evaluation of patients who:

- Have an uncertain diagnosis

- Fail to respond to treatment

- Are considering surgical intervention, particularly if previous surgery failed or the patient is a high surgical risk

- Exhibit comorbid conditions such as:

- · hematuria without infection

- · voiding dysfunction

- · recurrent urinary tract infection

- · prior anti-incontinence surgery

- · pelvic-organ prolapse beyond the hymen

- · a neurologic condition

Further evaluation may involve simple or complex urodynamics, cystoscopy, and various forms of urinary tract imaging. However, these tests are clearly not necessary for all patients.

1. Luber KM, Boero S, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: Current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1496-1501;discussion 1501-1503.

2. Thomas TM, Plymat KR, Blannin J, Meade TW. Prevalence of urinary incontinence. BMJ. 1980;281:1243-1245.

3. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

4. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167-178.

5. Theofrastous JP, Swift SE. The clinical evaluation of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1998;25:783-804.

6. Kotkin L, Milam DF. Evaluation and management of the urologic consequences of neurologic disease. Tech Urol. 1996;2:210-219.

7. Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10-17.

8. Caputo RM, Benson JT. The Q-tip test and urethrovesical junction mobility. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:892-896.

9. Bo K. Vaginal palpation of pelvic floor muscle strength: Inter-test reproducibility and comparison between palpation and vaginal squeeze pressure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:883-887.

10. ACOG criterial set. Surgery for genuine stress incontinence due to urethral hypermobility. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;52:211-212.

- A voiding diary, stress test, and postvoid residual volume measurement often can provide as much useful information as complex urodynamic investigations.

- In addition to performing the standard gynecologic exam, clinicians should assess patients for evidence of pelvic organ prolapse.

- A lower urinary tract infection can cause urgency, frequency, and nocturia, which can mimic urge incontinence or interstitial cystitis.

- Documentation of the postvoid residual volume is a prerequisite for any incontinence or anterior/apical prolapse procedure, because the clinician will need the information to interpret any postoperative voiding difficulty.

The meticulous evaluation and diagnosis of pelvic floor disorders, critical precursors of treatment, are feasible for any gynecologist—without specialized equipment. A specific history, voiding diary, focused physical exam, and simple office tests provide sufficient data to diagnose most complaints in a single office visit, allowing clinicians to initiate a management plan immediately.

This approach frequently can be carried out without additional studies. In other cases, the evaluation steers the practitioner to the appropriate investigations.

Increasing need for skill in assessing pelvic floor disorders

Although the underlying etiology of pelvic floor disorders is the subject of debate, the increasing demand for management of these problems is not.1 Urinary incontinence is thought to affect 10% to 25% of women 15 to 64 years old, becoming more common with age, although prevalence rates vary considerably according to the definition and survey method used and the population studied.2 A woman’s lifetime risk of undergoing a surgical procedure for prolapse or urinary incontinence is 11.1% by the age of 80.3

As the proportion of postmenopausal women increases over the next 30 years, these conditions will become even more prevalent.1 Thus, the ability to respond appropriately will be a key determinant of a gynecologic practice’s success. Clearly, the need for proper evaluation and diagnosis has never been greater.

How to assess the patient’s history

One way to facilitate a pelvic floor history is to give the patient a detailed questionnaire that can be completed prior to her initial office visit. First, elicit the patient’s main complaint, including its impact on her lifestyle. Other essential components of the pelvic floor history are a description of symptoms and quantification of their duration, frequency, and severity, as well as any previous treatment the patient has undergone.

Evaluate urinary continence. Urinary symptoms range from frequency, nocturia, and urgency to dysuria and hematuria. If the patient does not volunteer a history of urinary incontinence, she should be asked about it. Have her describe any incontinent episodes she has experienced, particularly the frequency and amount of urine lost.

- Urge incontinence, as its name implies, is typically preceded by an urge to void, and can involve a trigger such as running water or cold temperature.

- Stress incontinence generally occurs with sudden movements or increases in intra-abdominal pressure, such as those brought about by coughing, laughing, sneezing, or running.

Estimate urine loss. The severity of a patient’s incontinence can be crudely assessed by the type and quantity of protection used (e.g., maxi pads or panty liners). Evaluate the level of activity needed to provoke an incontinent episode. Incontinence with positional change between lying, sitting, and standing is more severe than occasional incontinence with vigorous exercise. Keep in mind that many women with urinary incontinence have components of both stress and urge loss, otherwise called mixed incontinence.

Look for voiding dysfunction, prolapse. Elicit any symptoms of voiding dysfunction, such as straining, hesitancy, intermittent flow, incomplete emptying, postvoid dribbling, and retention. Symptoms of pelvic-organ prolapse include vaginal pressure or bulging and associated discomfort.

Evaluate bowel function. Include questions about the patient’s bowel function, such as frequency, consistency, and constipation.

- Ask about her use of laxatives or antidiarrheal medications, since these may not be included in her list of medications.

- Also inquire about “splinting”—the use of a finger pressing in the vagina or on the perineum during fecal evacuation—as this can be a sign of posterior prolapse or rectocele.

- Ask specifically about the presence of any anal incontinence, which may involve liquid, gas, or solid stool.

Don’t overlook sexual ramifications. Finally, address the patient’s sexual function, particularly symptoms of discomfort, pain, or incontinence with sexual activity.

Voiding diary

This is an inexpensive way to obtain information about a woman’s daily bladder function. It is completed by the patient over a 24-hour period and includes oral fluid intake, episodes of incontinence, associated activities, and voids (FIGURE 1). Voiding volumes and times are recorded.4 The amount of fluid intake listed on voiding diaries often is surprising and can provide clues to treatment.

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines adult polyuria as more than 2,800 mL (approximately 94 oz) of urine output in 24 hours.4 The voiding diary depicted in FIGURE 1 came from a patient who complained of urinary frequency, nocturia, and rare stress incontinence. It shows that her 24-hour fluid intake was 3,360 mL (112 oz), and her urinary output was 3,720 mL (124 oz). The diary alone reveals that her symptoms are attributable to excessive fluid intake, resulting in polyuria, frequency, and nocturia. This patient experienced symptomatic relief with fluid and methylxanthine reduction.

FIGURE 1Sample voiding diary of a patient with complaints of urinary frequency, nocturia, and rare stress incontinence

This sample diary alone reveals that symptoms were due to excessive fluid and methylxanthine intake. This patient’s symptoms abated with decreased intake of water and tea.

Physical examination

Perform a complete physical exam, focusing attention on elements specific to pelvic floor disorders.

The International Continence Society periodically reports on terminology for the symptoms, signs, and urodynamic observations of pelvic floor disorders.1

| Urinary incontinence | Any involuntary leakage of urine |

| Stress urinary incontinence | Involuntary leakage of urine on effort or exertion |

| Urge urinary incontinence | Involuntary leakage accompanied by or immediately preceded by urgency |

| Urgency | A sudden compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer |

| Mixed urinary incontinence | Involuntary leakage associated with urgency and also with exertion, sneezing, or coughing |

| Anal incontinence | The inability to control passage of flatus or liquid or solid stool |

Stress test. If the patient relates a history of stress incontinence, the condition must be documented before any anti-incontinence procedure is considered. One simple method for this is a stress test.

Ask the patient to present for her office visit with a full bladder, as if she had an ultrasound appointment. At the start of the physical exam, perform the stress test with the patient in a standing position. (The full bladder should reduce false-negative results.)

Have the patient stand with 1 foot on the step of the examination table. Now, sit on a stool and separate the labia with 1 hand, so that the urethral meatus is visible. (A 4×4 gauze in the other hand can absorb any urine that is lost.) Have the patient cough forcefully several times while you observe the meatus for loss of urine. A spurt of urine coincident with the cough is a positive test.

If the patient has a significant amount of prolapse—i.e., stage III or IV)—repeat the stress test with the prolapse reduced to eliminate the effect of any urethral kinking. (The prolapse can be reduced using the posterior blade of a speculum.)

After the stress test, have the patient void in a measured device, such as a toilet hat, to record the voided volume. When she returns to the examination room, obtain a postvoid residual (PVR). The stress-test volume is determined by adding the volume voided to the PVR volume.

Postvoid residual volume. This assessment enables the clinician to determine the bladder’s ability to empty. Physicians can measure residual urine either by catheterization or ultrasound. When using ultrasound, perform transabdominal imaging in the transverse and mid-sagittal planes. Once you have obtained measurements of the bladder’s diameter in 3 planes (anterior-posterior, transverse, and sagittal/longitudinal), you can approximate the volume using this formula:

Volume (mL) = height (cm) × length (cm) × width (cm) × 0.52

If no bladder dimension is greater than 5 cm, the PVR is less than 65 mL.

In our opinion, documentation of the PVR is a prerequisite for any incontinence or anterior/apical prolapse procedure; the clinician will need this information to interpret any postoperative voiding difficulties and to counsel patients at increased risk of such difficulties.

Neurologic examination. Although it is unlikely that significant neurologic disease contributes to the patient’s pelvic floor dysfunction, the ramifications of any disease can be substantial. Thus, perform a focused neurologic exam to evaluate mental status, lower-extremity and perineal sensation, and reflexes. The 2 relevant spinalcord reflexes are the bulbocavernosus and the anal wink.5 Interpret these tests with caution, however, since an anal wink may be absent in some women who are otherwise neurologically normal.6

Simple office tests

POPQ exam. In addition to the standard gynecologic examination, patients complaining of or presenting with prolapse should undergo an objective measurement of the problem: the pelvic organ prolapse quantitative (POPQ) exam.

In 1996, the ICS published standardized terminology that has been adopted by most specialty organizations.7 This POPQ system describes the location and severity of prolapse using segments of the vaginal wall and external genitalia, rather than the terms cystocele, rectocele, and enterocele (FIGURE 2).

While the patient is straining, 6 specific sites are evaluated. Measure each site (in centimeters) in relation to the hymenal ring, which is a fixed, easily identified anatomic landmark. The hymenal ring is the zero point of reference. If a site is above the hymen, it is assigned a negative number; if it prolapses below the hymen, the measurement is positive.

In women with stress urinary incontinence, it is important to determine whether urethral hypermobility is present.

Use a Sims speculum or the posterior blade of a bivalve speculum to isolate the different vaginal compartments. An inexpensive disposable wooden spatula (Pap smear stick) marked with centimeters works well as the measuring device.

The 6 POPQ sites are:

- Aa: The point in the midline of the anterior vaginal wall 3 cm proximal to the urethral meatus, corresponding to the urethrovesical junction. By definition, the range of position Aa is -3 to +3.

- Ba: On the anterior vaginal wall, the most dependent position between point Aa and the vaginal cuff or anterior vaginal fornix.

- C: Cervix or vaginal cuff (posthysterectomy).

- D: Posterior fornix corresponding to the pouch of Douglas (this point is omitted in the absence of a cervix).

- Ap: The point in the midline of the posterior vaginal wall 3 cm proximal to the hymenal ring. By definition, the range of position Ap is -3 to +3.

- Bp: On the posterior vaginal wall, the most dependent position between Ap and the vaginal cuff or posterior fornix.

Two additional measurements are made in centimeters while the patient is straining:

- GH: The genital hiatus is measured from the midportion of the urethral meatus to the posterior margin of the genital hiatus.

- PB: The perineal body is measured between the posterior margin of the genital hiatus and the midportion of the anus.

While the patient is not straining, a ninth measurement is made:

- TVL: Total vaginal length is the greatest depth of the vagina.

Staging each compartment. When all 9 of these measurements have been taken, a stage can be assigned to each compartment: anterior, apex (uterine or vault), and posterior. The stages are:

- Stage 0: No prolapse is demonstrated. Points Aa, Ap, Ba, and Bp are all at -3 cm and either point C or point D is within 2 cm of TVL.

- Stage I: The most distal portion of the prolapse is 1 cm above the level of the hymen (above -1).

- Stage II: The most distal portion of the prolapse is 1cm proximal to or distal to the hymen.

- Stage III: The most distal portion of the prolapse is 1 cm below the hymen but protrudes no further than 2 cm less than the total vaginal length.

- Stage IV: Complete eversion is present.

Most parous women are stage I, II, or III. If you remember that stage II is between and including -1 and +1, it follows that stage I is above this and stage III is below this. FIGURE 3 compares POPQ examination findings of normal support and posthysterectomy vaginal eversion.

Assess urethral hypermobility. In women with stress urinary incontinence, it is important to determine whether urethral hypermobility is present, since this finding may influence surgical management.

- Q-tip test. Measure mobility by placing a lubricated sterile cotton swab within the urethra so that the tip of the swab is at the urethrovesical junction. Lubrication with xylocaine gel may reduce the discomfort of this step. Measure the angle between the swab and the horizontal plane with a goniometer both while the patient is not straining and while the patient is straining at maximum. Urethral hypermobility exists if the angle is more than 30° either at rest or with straining.8

- Indications for surgery. Ahypermobile urethra is thought to correlate with decreased support of the urethra and the urethrovesical junction, which has been implicated in the development of stress incontinence. Many surgical interventions for stress incontinence are designed to increase support to this area.

In 1996, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published guidelines for surgery for genuine stress incontinence due to urethral hypermobility in patients without a history of previous antiincontinence surgery.10 These criteria include:

- History and demonstration of stress urinary incontinence

- No significant urge component

- Absence of transient causes of urinary incontinence

- Normal PVR volume

- Normal voiding habits

- Absence of neurologic history or findings

- Absence of pregnancy

- Confirmation that the patient has been counseled regarding more conservative therapy

The office evaluation of pelvic floor disorders outlined in this article meets the ACOG criteria. Of course, consider surgical management only after conservative measures have been exhausted.

Evaluate pelvic floor tone. This portion of the exam assesses the strength of the pelvic-floor musculature. Place 1 or 2 fingers in the vagina and instruct the patient to contract her pelvic floor muscles (i.e., the levator ani muscles). Then gauge her ability to contract these muscles, as well as the strength, symmetry, and duration of the contraction.

The strength of the contraction can be subjectively graded with a modified Oxford scale (0 = no contraction, 1 = flicker, 2 = weak, 3 = moderate, 4 = good, 5 = strong).9

Women with an external anal sphincter defect may lack the normal stellate pattern around the anus anteriorly.

Determine structure and function of the anal sphincter. This is the final part of the physical exam. Women with an external anal sphincter defect may lack the normal stellate pattern around the anus anteriorly because of the absence of contractile tissue. A rectal exam should be performed at rest and with voluntary squeezing of the anal sphincter to assess resting tone and squeeze strength of the anal sphincter muscle complex. In addition, the bulk of this complex can be palpated to determine whether a structural defect is present (usually found anteriorly).

FIGURE 2Quantifying pelvic organ support

Nine sites—points Aa, Ba, C, D, Bp, and Ap; the genital hiatus (GH); the perineal body (PB); and total vaginal length (TVL)—are used to measure pelvic organ support. This drawing represents Stage 0 prolapse, as there is no descent of any of the vaginal compartments. Points Aa and Ap are always measured at the point exactly 3 cm from the reference point of the hymenal ring. Since there is no descent in this example, points Aa and Ap are both -3.

FIGURE 3Posthysterectomy pelvic organ prolapse quantitative (POPQ) examination

POPQ examination for a patient with normal support who has undergone a hysterectomy. When compared to FIGURE 2, notice the absence of point D; point C now represents the vaginal cuff.

POPQ examination for a patient with vault prolapse after a hysterectomy. Notice how points Aa and Ap are now located outside the body, but are still exactly 3 cm from the hymen. The most distal part of the anterior wall (point Ba), the vaginal cuff (point C), and the most dis-tal part of the posterior wall (point Bp) are all at the same position.

Laboratory studies

Initial laboratory studies should include a urine dipstick analysis and possible culture to evaluate for infection or hematuria. A lower urinary tract infection can produce symptoms such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia, which can mimic the presentation of urge incontinence or interstitial cystitis. Hematuria may herald a more worrisome but rare condition such as transitional cell cancer of the bladder.

Indications for urodynamic testing

Although the basic office evaluation outlined here provides adequate information to properly treat most women with urinary incontinence, further evaluation is appropriate in some cases. A thorough discussion of urodynamics is beyond the scope of this article, but it is important to understand when a patient may require additional investigations. In 1996, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research recommended further evaluation of patients who:

- Have an uncertain diagnosis

- Fail to respond to treatment

- Are considering surgical intervention, particularly if previous surgery failed or the patient is a high surgical risk

- Exhibit comorbid conditions such as:

- · hematuria without infection

- · voiding dysfunction

- · recurrent urinary tract infection

- · prior anti-incontinence surgery

- · pelvic-organ prolapse beyond the hymen

- · a neurologic condition

Further evaluation may involve simple or complex urodynamics, cystoscopy, and various forms of urinary tract imaging. However, these tests are clearly not necessary for all patients.

- A voiding diary, stress test, and postvoid residual volume measurement often can provide as much useful information as complex urodynamic investigations.

- In addition to performing the standard gynecologic exam, clinicians should assess patients for evidence of pelvic organ prolapse.

- A lower urinary tract infection can cause urgency, frequency, and nocturia, which can mimic urge incontinence or interstitial cystitis.

- Documentation of the postvoid residual volume is a prerequisite for any incontinence or anterior/apical prolapse procedure, because the clinician will need the information to interpret any postoperative voiding difficulty.

The meticulous evaluation and diagnosis of pelvic floor disorders, critical precursors of treatment, are feasible for any gynecologist—without specialized equipment. A specific history, voiding diary, focused physical exam, and simple office tests provide sufficient data to diagnose most complaints in a single office visit, allowing clinicians to initiate a management plan immediately.

This approach frequently can be carried out without additional studies. In other cases, the evaluation steers the practitioner to the appropriate investigations.

Increasing need for skill in assessing pelvic floor disorders

Although the underlying etiology of pelvic floor disorders is the subject of debate, the increasing demand for management of these problems is not.1 Urinary incontinence is thought to affect 10% to 25% of women 15 to 64 years old, becoming more common with age, although prevalence rates vary considerably according to the definition and survey method used and the population studied.2 A woman’s lifetime risk of undergoing a surgical procedure for prolapse or urinary incontinence is 11.1% by the age of 80.3

As the proportion of postmenopausal women increases over the next 30 years, these conditions will become even more prevalent.1 Thus, the ability to respond appropriately will be a key determinant of a gynecologic practice’s success. Clearly, the need for proper evaluation and diagnosis has never been greater.

How to assess the patient’s history

One way to facilitate a pelvic floor history is to give the patient a detailed questionnaire that can be completed prior to her initial office visit. First, elicit the patient’s main complaint, including its impact on her lifestyle. Other essential components of the pelvic floor history are a description of symptoms and quantification of their duration, frequency, and severity, as well as any previous treatment the patient has undergone.

Evaluate urinary continence. Urinary symptoms range from frequency, nocturia, and urgency to dysuria and hematuria. If the patient does not volunteer a history of urinary incontinence, she should be asked about it. Have her describe any incontinent episodes she has experienced, particularly the frequency and amount of urine lost.

- Urge incontinence, as its name implies, is typically preceded by an urge to void, and can involve a trigger such as running water or cold temperature.

- Stress incontinence generally occurs with sudden movements or increases in intra-abdominal pressure, such as those brought about by coughing, laughing, sneezing, or running.

Estimate urine loss. The severity of a patient’s incontinence can be crudely assessed by the type and quantity of protection used (e.g., maxi pads or panty liners). Evaluate the level of activity needed to provoke an incontinent episode. Incontinence with positional change between lying, sitting, and standing is more severe than occasional incontinence with vigorous exercise. Keep in mind that many women with urinary incontinence have components of both stress and urge loss, otherwise called mixed incontinence.

Look for voiding dysfunction, prolapse. Elicit any symptoms of voiding dysfunction, such as straining, hesitancy, intermittent flow, incomplete emptying, postvoid dribbling, and retention. Symptoms of pelvic-organ prolapse include vaginal pressure or bulging and associated discomfort.

Evaluate bowel function. Include questions about the patient’s bowel function, such as frequency, consistency, and constipation.

- Ask about her use of laxatives or antidiarrheal medications, since these may not be included in her list of medications.

- Also inquire about “splinting”—the use of a finger pressing in the vagina or on the perineum during fecal evacuation—as this can be a sign of posterior prolapse or rectocele.

- Ask specifically about the presence of any anal incontinence, which may involve liquid, gas, or solid stool.

Don’t overlook sexual ramifications. Finally, address the patient’s sexual function, particularly symptoms of discomfort, pain, or incontinence with sexual activity.

Voiding diary

This is an inexpensive way to obtain information about a woman’s daily bladder function. It is completed by the patient over a 24-hour period and includes oral fluid intake, episodes of incontinence, associated activities, and voids (FIGURE 1). Voiding volumes and times are recorded.4 The amount of fluid intake listed on voiding diaries often is surprising and can provide clues to treatment.

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines adult polyuria as more than 2,800 mL (approximately 94 oz) of urine output in 24 hours.4 The voiding diary depicted in FIGURE 1 came from a patient who complained of urinary frequency, nocturia, and rare stress incontinence. It shows that her 24-hour fluid intake was 3,360 mL (112 oz), and her urinary output was 3,720 mL (124 oz). The diary alone reveals that her symptoms are attributable to excessive fluid intake, resulting in polyuria, frequency, and nocturia. This patient experienced symptomatic relief with fluid and methylxanthine reduction.

FIGURE 1Sample voiding diary of a patient with complaints of urinary frequency, nocturia, and rare stress incontinence

This sample diary alone reveals that symptoms were due to excessive fluid and methylxanthine intake. This patient’s symptoms abated with decreased intake of water and tea.

Physical examination

Perform a complete physical exam, focusing attention on elements specific to pelvic floor disorders.

The International Continence Society periodically reports on terminology for the symptoms, signs, and urodynamic observations of pelvic floor disorders.1

| Urinary incontinence | Any involuntary leakage of urine |

| Stress urinary incontinence | Involuntary leakage of urine on effort or exertion |

| Urge urinary incontinence | Involuntary leakage accompanied by or immediately preceded by urgency |

| Urgency | A sudden compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer |

| Mixed urinary incontinence | Involuntary leakage associated with urgency and also with exertion, sneezing, or coughing |

| Anal incontinence | The inability to control passage of flatus or liquid or solid stool |

Stress test. If the patient relates a history of stress incontinence, the condition must be documented before any anti-incontinence procedure is considered. One simple method for this is a stress test.

Ask the patient to present for her office visit with a full bladder, as if she had an ultrasound appointment. At the start of the physical exam, perform the stress test with the patient in a standing position. (The full bladder should reduce false-negative results.)

Have the patient stand with 1 foot on the step of the examination table. Now, sit on a stool and separate the labia with 1 hand, so that the urethral meatus is visible. (A 4×4 gauze in the other hand can absorb any urine that is lost.) Have the patient cough forcefully several times while you observe the meatus for loss of urine. A spurt of urine coincident with the cough is a positive test.

If the patient has a significant amount of prolapse—i.e., stage III or IV)—repeat the stress test with the prolapse reduced to eliminate the effect of any urethral kinking. (The prolapse can be reduced using the posterior blade of a speculum.)

After the stress test, have the patient void in a measured device, such as a toilet hat, to record the voided volume. When she returns to the examination room, obtain a postvoid residual (PVR). The stress-test volume is determined by adding the volume voided to the PVR volume.

Postvoid residual volume. This assessment enables the clinician to determine the bladder’s ability to empty. Physicians can measure residual urine either by catheterization or ultrasound. When using ultrasound, perform transabdominal imaging in the transverse and mid-sagittal planes. Once you have obtained measurements of the bladder’s diameter in 3 planes (anterior-posterior, transverse, and sagittal/longitudinal), you can approximate the volume using this formula:

Volume (mL) = height (cm) × length (cm) × width (cm) × 0.52

If no bladder dimension is greater than 5 cm, the PVR is less than 65 mL.

In our opinion, documentation of the PVR is a prerequisite for any incontinence or anterior/apical prolapse procedure; the clinician will need this information to interpret any postoperative voiding difficulties and to counsel patients at increased risk of such difficulties.

Neurologic examination. Although it is unlikely that significant neurologic disease contributes to the patient’s pelvic floor dysfunction, the ramifications of any disease can be substantial. Thus, perform a focused neurologic exam to evaluate mental status, lower-extremity and perineal sensation, and reflexes. The 2 relevant spinalcord reflexes are the bulbocavernosus and the anal wink.5 Interpret these tests with caution, however, since an anal wink may be absent in some women who are otherwise neurologically normal.6

Simple office tests

POPQ exam. In addition to the standard gynecologic examination, patients complaining of or presenting with prolapse should undergo an objective measurement of the problem: the pelvic organ prolapse quantitative (POPQ) exam.

In 1996, the ICS published standardized terminology that has been adopted by most specialty organizations.7 This POPQ system describes the location and severity of prolapse using segments of the vaginal wall and external genitalia, rather than the terms cystocele, rectocele, and enterocele (FIGURE 2).

While the patient is straining, 6 specific sites are evaluated. Measure each site (in centimeters) in relation to the hymenal ring, which is a fixed, easily identified anatomic landmark. The hymenal ring is the zero point of reference. If a site is above the hymen, it is assigned a negative number; if it prolapses below the hymen, the measurement is positive.

In women with stress urinary incontinence, it is important to determine whether urethral hypermobility is present.

Use a Sims speculum or the posterior blade of a bivalve speculum to isolate the different vaginal compartments. An inexpensive disposable wooden spatula (Pap smear stick) marked with centimeters works well as the measuring device.

The 6 POPQ sites are:

- Aa: The point in the midline of the anterior vaginal wall 3 cm proximal to the urethral meatus, corresponding to the urethrovesical junction. By definition, the range of position Aa is -3 to +3.

- Ba: On the anterior vaginal wall, the most dependent position between point Aa and the vaginal cuff or anterior vaginal fornix.

- C: Cervix or vaginal cuff (posthysterectomy).

- D: Posterior fornix corresponding to the pouch of Douglas (this point is omitted in the absence of a cervix).

- Ap: The point in the midline of the posterior vaginal wall 3 cm proximal to the hymenal ring. By definition, the range of position Ap is -3 to +3.

- Bp: On the posterior vaginal wall, the most dependent position between Ap and the vaginal cuff or posterior fornix.

Two additional measurements are made in centimeters while the patient is straining:

- GH: The genital hiatus is measured from the midportion of the urethral meatus to the posterior margin of the genital hiatus.

- PB: The perineal body is measured between the posterior margin of the genital hiatus and the midportion of the anus.

While the patient is not straining, a ninth measurement is made:

- TVL: Total vaginal length is the greatest depth of the vagina.

Staging each compartment. When all 9 of these measurements have been taken, a stage can be assigned to each compartment: anterior, apex (uterine or vault), and posterior. The stages are:

- Stage 0: No prolapse is demonstrated. Points Aa, Ap, Ba, and Bp are all at -3 cm and either point C or point D is within 2 cm of TVL.

- Stage I: The most distal portion of the prolapse is 1 cm above the level of the hymen (above -1).

- Stage II: The most distal portion of the prolapse is 1cm proximal to or distal to the hymen.

- Stage III: The most distal portion of the prolapse is 1 cm below the hymen but protrudes no further than 2 cm less than the total vaginal length.

- Stage IV: Complete eversion is present.

Most parous women are stage I, II, or III. If you remember that stage II is between and including -1 and +1, it follows that stage I is above this and stage III is below this. FIGURE 3 compares POPQ examination findings of normal support and posthysterectomy vaginal eversion.

Assess urethral hypermobility. In women with stress urinary incontinence, it is important to determine whether urethral hypermobility is present, since this finding may influence surgical management.

- Q-tip test. Measure mobility by placing a lubricated sterile cotton swab within the urethra so that the tip of the swab is at the urethrovesical junction. Lubrication with xylocaine gel may reduce the discomfort of this step. Measure the angle between the swab and the horizontal plane with a goniometer both while the patient is not straining and while the patient is straining at maximum. Urethral hypermobility exists if the angle is more than 30° either at rest or with straining.8

- Indications for surgery. Ahypermobile urethra is thought to correlate with decreased support of the urethra and the urethrovesical junction, which has been implicated in the development of stress incontinence. Many surgical interventions for stress incontinence are designed to increase support to this area.

In 1996, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published guidelines for surgery for genuine stress incontinence due to urethral hypermobility in patients without a history of previous antiincontinence surgery.10 These criteria include:

- History and demonstration of stress urinary incontinence

- No significant urge component

- Absence of transient causes of urinary incontinence

- Normal PVR volume

- Normal voiding habits

- Absence of neurologic history or findings

- Absence of pregnancy

- Confirmation that the patient has been counseled regarding more conservative therapy

The office evaluation of pelvic floor disorders outlined in this article meets the ACOG criteria. Of course, consider surgical management only after conservative measures have been exhausted.

Evaluate pelvic floor tone. This portion of the exam assesses the strength of the pelvic-floor musculature. Place 1 or 2 fingers in the vagina and instruct the patient to contract her pelvic floor muscles (i.e., the levator ani muscles). Then gauge her ability to contract these muscles, as well as the strength, symmetry, and duration of the contraction.

The strength of the contraction can be subjectively graded with a modified Oxford scale (0 = no contraction, 1 = flicker, 2 = weak, 3 = moderate, 4 = good, 5 = strong).9

Women with an external anal sphincter defect may lack the normal stellate pattern around the anus anteriorly.

Determine structure and function of the anal sphincter. This is the final part of the physical exam. Women with an external anal sphincter defect may lack the normal stellate pattern around the anus anteriorly because of the absence of contractile tissue. A rectal exam should be performed at rest and with voluntary squeezing of the anal sphincter to assess resting tone and squeeze strength of the anal sphincter muscle complex. In addition, the bulk of this complex can be palpated to determine whether a structural defect is present (usually found anteriorly).

FIGURE 2Quantifying pelvic organ support

Nine sites—points Aa, Ba, C, D, Bp, and Ap; the genital hiatus (GH); the perineal body (PB); and total vaginal length (TVL)—are used to measure pelvic organ support. This drawing represents Stage 0 prolapse, as there is no descent of any of the vaginal compartments. Points Aa and Ap are always measured at the point exactly 3 cm from the reference point of the hymenal ring. Since there is no descent in this example, points Aa and Ap are both -3.

FIGURE 3Posthysterectomy pelvic organ prolapse quantitative (POPQ) examination

POPQ examination for a patient with normal support who has undergone a hysterectomy. When compared to FIGURE 2, notice the absence of point D; point C now represents the vaginal cuff.

POPQ examination for a patient with vault prolapse after a hysterectomy. Notice how points Aa and Ap are now located outside the body, but are still exactly 3 cm from the hymen. The most distal part of the anterior wall (point Ba), the vaginal cuff (point C), and the most dis-tal part of the posterior wall (point Bp) are all at the same position.

Laboratory studies

Initial laboratory studies should include a urine dipstick analysis and possible culture to evaluate for infection or hematuria. A lower urinary tract infection can produce symptoms such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia, which can mimic the presentation of urge incontinence or interstitial cystitis. Hematuria may herald a more worrisome but rare condition such as transitional cell cancer of the bladder.

Indications for urodynamic testing

Although the basic office evaluation outlined here provides adequate information to properly treat most women with urinary incontinence, further evaluation is appropriate in some cases. A thorough discussion of urodynamics is beyond the scope of this article, but it is important to understand when a patient may require additional investigations. In 1996, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research recommended further evaluation of patients who:

- Have an uncertain diagnosis

- Fail to respond to treatment

- Are considering surgical intervention, particularly if previous surgery failed or the patient is a high surgical risk

- Exhibit comorbid conditions such as:

- · hematuria without infection

- · voiding dysfunction

- · recurrent urinary tract infection

- · prior anti-incontinence surgery

- · pelvic-organ prolapse beyond the hymen

- · a neurologic condition

Further evaluation may involve simple or complex urodynamics, cystoscopy, and various forms of urinary tract imaging. However, these tests are clearly not necessary for all patients.

1. Luber KM, Boero S, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: Current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1496-1501;discussion 1501-1503.

2. Thomas TM, Plymat KR, Blannin J, Meade TW. Prevalence of urinary incontinence. BMJ. 1980;281:1243-1245.

3. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

4. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167-178.

5. Theofrastous JP, Swift SE. The clinical evaluation of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1998;25:783-804.

6. Kotkin L, Milam DF. Evaluation and management of the urologic consequences of neurologic disease. Tech Urol. 1996;2:210-219.

7. Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10-17.

8. Caputo RM, Benson JT. The Q-tip test and urethrovesical junction mobility. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:892-896.

9. Bo K. Vaginal palpation of pelvic floor muscle strength: Inter-test reproducibility and comparison between palpation and vaginal squeeze pressure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:883-887.

10. ACOG criterial set. Surgery for genuine stress incontinence due to urethral hypermobility. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;52:211-212.

1. Luber KM, Boero S, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: Current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1496-1501;discussion 1501-1503.

2. Thomas TM, Plymat KR, Blannin J, Meade TW. Prevalence of urinary incontinence. BMJ. 1980;281:1243-1245.

3. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

4. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167-178.

5. Theofrastous JP, Swift SE. The clinical evaluation of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1998;25:783-804.

6. Kotkin L, Milam DF. Evaluation and management of the urologic consequences of neurologic disease. Tech Urol. 1996;2:210-219.

7. Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10-17.

8. Caputo RM, Benson JT. The Q-tip test and urethrovesical junction mobility. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:892-896.

9. Bo K. Vaginal palpation of pelvic floor muscle strength: Inter-test reproducibility and comparison between palpation and vaginal squeeze pressure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:883-887.

10. ACOG criterial set. Surgery for genuine stress incontinence due to urethral hypermobility. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;52:211-212.