User login

CONTRACEPTION

Greater access to Plan B leads to increased—and faster—use

Now that Plan B is available OTC to both men and women 18 years and older,1 several questions are in order:

- What are the effects of this change?

- Does OTC access or provision of the drug in advance reduce condom or oral contraceptive use?

- Does it increase the number of sexual partners or rate of sexually transmitted disease (STD)?

- Does it reduce unintended pregnancy?

Several randomized trials have found that advance provision of EC not only increases its utilization, but causes it to be used sooner.2-7 Most of the trials conducted so far have compared advance provision of EC with counseling about EC or a prescription for it. Only one trial has included a pharmacy-access arm, and it was conducted before FDA approval of OTC status.3 It found that pharmacy access did not increase use of EC, compared with standard access (ie, returning to the clinic when EC was needed). It is too early to tell what effect OTC availability will have on the usage rate, but data so far support the practice of giving the patient a supply of EC rather than just a prescription.

Increased access to EC does not affect regular contraceptive behavior

Multiple studies have shown that advance provision of EC has no significant effect on the use of regular contraception. Studies have examined the impact of EC on both baseline oral contraceptive usage and condom usage and found no significant change in either among women who used EC during the study.3-6

… nor does it cause promiscuity or increase the rate of STD

Multiple studies have demonstrated that advance provision of EC does not increase the number of sexual partners or rate of STD.3-6 The largest of these studies compared both pharmacy access without a prescription and advance provision of EC to standard access. That study included 2,117 sexually active young women and found no difference in the rate of STD or number of sex partners among the three study groups.3 Smaller studies comparing advance pro-vision of EC with standard access also found no significant difference in these variables.8,9

No evidence of fewer unintended pregnancies—yet

We know that progestin-only EC can reduce unintended pregnancy by almost 90%.10 However, studies have not yet demonstrated such a decrease in the general population. One reason may be that the two studies that considered unintended pregnancy as a primary outcome3,9 were too small to detect a difference in pregnancy rates, or it may be that EC was underutilized by women in the studies.

Prescribing information for levonorgestrel emergency contraception (EC) recommends ingestion of the first 0.75-mg tablet within 72 hours (3 days) of a single act of unprotected intercourse, with the second tablet taken 12 hours after the first.11 However, data show that levonorgestrel EC can prevent pregnancy up to 5 days after intercourse. In a World Health Organization multicenter randomized trial of various EC regimens, levonorgestrel EC prevented 79% to 84% of expected pregnancies when taken within 1 to 3 days, and 60% to 63% when taken 4 to 5 days after intercourse.12 Randomized trials have also found that taking both 0.75-mg levonorgestrel pills simultaneously prevents pregnancy as effectively as taking them 12 hours apart.

Levonorgestrel EC prevents or delays ovulation by inhibiting the luteinizing hormone surge during the follicular phase.13 Secondary mechanisms of contraceptive action include thickening of the cervical mucus; decreased pH level, which immobilizes sperm; and decreased recovery of sperm from the uterus.14

Levonorgestrel intrauterine system has benefits beyond contraception

The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) has been shown to significantly decrease blood loss and increase hemoglobin and serum ferritin levels in women with idiopathic menorrhagia.15 The LNGIUS reduces blood loss to a greater degree (as much as 96% after 1 year) than do placebo, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antifibrinolytic medication, and oral contraceptives.16 In one study,16 the LNG-IUS was the only treatment that reduced menstrual bleeding to less than 80 mL/day—the upper limit of normal.

LNG-IUS compares favorably to endometrial ablation

The LNG-IUS provides nonoperative, local, and minimally invasive treatment of menorrhagia, producing clinical results similar to those of different endometrial ablation methods for dysfunctional uterine bleeding or menorrhagia. The LNG-IUS is comparable to endometrial resection in its reduction of blood loss, patient satisfaction, rate of amenorrhea, and recurrent menorrhagia.17 It also is equivalent to thermal balloon ablation in its reduction of bleeding and increased quality of life and hemoglobin level.18,19 And it produces a higher amenorrhea rate than expectant management after endometrial resection in women with adenomyosis, and averts the need for further procedures, such as hysterectomy and repeat resection.20

In many women, LNG-IUS renders hysterectomy unnecessary

In a controlled trial involving 56 women on a waiting list for hysterectomy, 64% of those who received the LNG-IUS and 14% of those in a control group removed themselves from the list at the end of 6 months because they were satisfied with symptom control (P.001>21 In a trial involving 236 women with menorrhagia randomized to LNG-IUS or hysterectomy, the groups had similar quality-of-life scores at 1 and 5 years of follow-up—and costs associated with the LNG-IUS were significantly lower than those associated with hysterectomy, even after 50 women randomized to the LNG-IUS opted for and underwent hysterectomy.41

Consider the LNG-IUS a first-line therapy for symptomatic fibroids

The LNG-IUS continuously decreases fibroid and uterine volume and blood loss and increases ferritin levels over time among women with symptomatic fibroids.22 It should therefore be routinely considered a first-line therapy for women with fibroids who wish to preserve their childbearing potential.

Endometrial hyperplasia is reduced

The LNG-IUS can prevent and induce regression of endometrial hyperplasia.23,24 In addition, it reduces bleeding and spotting among women using hormone replacement therapy.25,26 Studies also suggest it may be beneficial in the treatment of stage I endometrial cancer, although further research into this effect is needed.27

Endometriosis-related pain is eased

In a randomized trial comparing the LNG-IUS with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue among women with chronic pelvic pain due to endometriosis, both treatments reduced pain and improved psychological well-being to the same degree—but the LNG-IUS caused no systemic hypoestrogenic symptoms, unlike the GnRH analogue.28 In a randomized trial comparing the LNGIUS with expectant management among women who had undergone laparoscopic resection of endometriosis, women in the LNG-IUS arm had significantly decreased recurrent dysmenorrhea.29

In addition, the LNG-IUS is effective for as long as 5 years, can be used in conjunction with systemic estrogen, and is an effective contraceptive.

Continuous oral contraceptive regimens: 4 effective options

Oral contraceptives (OCs) can be prescribed for continuous use to achieve a number of different goals30:

- decrease the number of placebo days per cycle

- reduce the number of placebo weeks or withdrawal weeks per year

- eliminate withdrawal weeks from the cycle entirely

- reduce the incidence of breakthrough bleeding

Reduce the number of placebo days

Compared with the standard 28-day regimen (21 days of active pills followed by 7 days of placebo), extended regimens significantly reduce ovarian activity and produce smaller follicles and a lower estrogen level.31,32 Extended regimens may involve fewer days of placebo pills per cycle, or very small amounts of estrogen throughout the withdrawal week of the regimen. These modifications may translate into increased efficacy. In two randomized trials comparing extended regimens with a standard regimen, the extended regimens were highly effective, with a Pearl index of up to 1.29 (1.29 pregnancies for every 100 woman-years of use), and produced shorter withdrawal bleeds.33,34

Decrease the number of placebo or withdrawal weeks

The FDA approved the first OC to be packaged for extended use (Seasonale) in 2003. Each pack contains 84 active tablets of ethinyl estradiol (0.03 mg) and levonorgestrel (0.15 mg), followed by seven placebo pills. This highly effective regimen has a failure rate of 0.60 per 100 woman-years.35 Another extended-use OC (Seasonique) contains 7 days of ethinyl estradiol (10 μg) instead of placebo pills and may, therefore, suppress follicular development to an even greater degree during the withdrawal week.36

Extended cycles can be achieved with any monophasic OC in an off-label manner. Simply instruct the patient to take one active tablet for 42 consecutive days (known as “bicycling”) or for 63 consecutive days (“tricycling”), followed by 4 to 7 pill-free days.

Unscheduled bleeding with the 63-day regimen appears to be similar to the rate associated with the 21-day regimen.35 An extended-cycle regimen can be modified according to how often the user wants withdrawal bleeding.

Eliminate the withdrawal week

Perhaps the most radical extended-cycle regimen is continuous use of active pills with no placebo or withdrawal interval. This option is safe and acceptable to women, according to two small randomized trials and two prospective trials, but larger studies are needed to confirm these results.37-40 Continuous use for 1 year is associated with less bleeding, higher rates of amenorrhea, and similar side effects, compared with conventional regimens.37,38 Patient acceptance and satisfaction also are high,39 with most women choosing to keep taking the pill continuously. Lybrel, an OC designed for this purpose, contains 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and 90 μg of levonorgestrel and is intended to eliminate menses through 1 year of continuous use.

Reduce breakthrough bleeding

For women who experience unscheduled bleeding while taking an OC continuously, one option is to stop taking pills when breakthrough bleeding occurs and initiate a hormone-free interval. This approach was studied in a randomized trial in which women were scheduled to take an OC continuously for 168 days.40 Women who had persistent unscheduled bleeding for longer than 7 days were randomized to a 3-day hormone-free interval or continuation of the active pills. Those who continued taking active pills had more bleeding over the long term, and a large percentage found it necessary to institute a delayed hormone-free interval.

This option may be particularly useful for women who experience persistent breakthrough bleeding on a continuous regimen.40

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves over-the-counter access for Plan B for women 18 and older; prescription remains required for those 17 and under [August 24, 2006]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01436.html. Accessed July 11, 2007.

2. Harper CC, Cheong M, Rocca CH, Darney PD, Raine TR. The effect of increased access to emergency contraception among young adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:483-491.

3. Raine TR, Harper CC, Rocca CH, et al. Direct access to emergency contraception through pharmacies and effect on unintended pregnancy and STIs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:54-62.

4. Raymond EG, Trussell J, Polis CB. Population effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:181-188.

5. Walsh TL, Frezieres RG. Patterns of emergency contraception use by age and ethnicity from a randomized trial comparing advance provision and information only. Contraception. 2006;74:110-117.

6. Jackson RA, Schwarz EB, Freedman L, Darney PD. Advance supply of emergency contraception. Effect on use and usual contraception—a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:8-16.

7. Hu X, Cheng L, Hua X, Glasier A. Advanced provision of emergency contraception to postnatal women in China makes no difference in abortion rates: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2005;72:111-116.

8. Gold MA, Wolford JE, Smith KA, Parker AM. The effects of advance provision of emergency contraception on adolescent women’s sexual and contraceptive behaviors. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17:87-96.

9. Raymond EG, Stewart F, Weaver M, Monteith C, Van Der Pol B. Impact of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1098-1106.

10. Trussell J, Ellertson C, Stewart F. The effectiveness of the Yuzpe regimen of emergency contraception. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28:58-64, 87.

11. Plan B. [package insert] Pomona, NY: Duramed Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2006.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1803-1810.

13. Durand M, del Carmen Cravioto M, Raymond EG, et al. On the mechanisms of action of short-term levonorgestrel administration in emergency contraception. Contraception. 2001;64:227-234.

14. Croxatto HB, Devoto L, Durand M, et al. Mechanism of action of hormonal preparations used for emergency contraception: a review of the literature. Contraception. 2001;63:111-121.

15. Xiao B, Wu SC, Chong J, et al. Therapeutic effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:963-969.

16. Milsom I, Andersson K, Andersch B, Rybo G. A comparison of flurbiprofen, tranexamic acid, and a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive device in the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:879-883.

17. Crosignani PG, Vercellini P, Mosconi P, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus hysteroscopic endometrial resection in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:257-263.

18. Soysal M, Soysal S, Ozer S. A randomized controlled trial of levonorgestrel releasing IUD and thermal balloon ablation in the treatment of menorrhagia. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2002;124:213-219.

19. Barrington JW, Arunkalaivanan AS, Abdel-Fattah M. Comparison between the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) and thermal balloon ablation in the treatment of menorrhagia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;108:72-74.

20. Maia H, Jr, Maltez A, Coelho G, et al. Insertion of Mirena after endometrial resection in patients with adenomyosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:512-516.

21. Lahteenmaki P, Haukkamaa M, Puolakka J, et al. Open randomised study of use of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system as alternative to hysterectomy. BMJ. 1998;316:1122-1126.

22. Grigorieva V, Chen-Mok M, Tarasova M, Mikhailov A. Use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system to treat bleeding related to uterine leiomyomas. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1194-1198.

23. Scarselli G, Tantini C, Colafranceschi M, et al. Levonorgestrel-nova-T and precancerous lesions of the endometrium. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1988;9:284-286.

24. Perino A, Quartararo P, Catinella E, et al. Treatment of endometrial hyperplasia with levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine devices. Acta Eur Fertil. 1987;18:137-140.

25. Ettinger B, Pressman A, Silver P. Effect of age on reasons for initiation and discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause. 1999;6:282-289.

26. Andersson K, Mattson LA, Rybo G, Stadberg E. Intrauterine release of levonorgestrel—a new way of adding progestogen in hormone replacement therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:963-967.

27. Montz FJ, Bristow RE, Bovicelli A, et al. Intrauterine progesterone treatment of early endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:651-657.

28. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1993-1998.

29. Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, Aimi G, Zaina B, Crosignani PG. Comparison of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:305-309.

30. Steinauer J, Autry AM. Extended cycle combined hormonal contraception. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:43-55, viii.

31. Spona J, Elstein M, Feichtinger W, et al. Shorter pill-free interval in combined oral contraceptives decreases follicular development. Contraception. 1996;54:71-77.

32. Sullivan H, Furniss H, Spona J, Elstein M. Effect of 21-day and 24-day oral contraceptive regimens containing gestodene (60 microg) and ethinyl estradiol (15 microg) on ovarian activity. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:115-120.

33. Bachmann G, Sulak PJ, Sampson-Landers C, Benda N, Marr J. Efficacy and safety of a low-dose 24-day combined oral contraceptive containing 20 micrograms ethinylestradiol and 3 mg drospirenone. Contraception. 2004;70:191-198.

34. Endrikat J, Cronin M, Gerlinger C, Ruebig A, Schmidt W, Düsterburg B. Open, multicenter comparison of efficacy, cycle control, and tolerability of a 23-day oral contraceptive regimen with 20 microg ethinyl estradiol and 75 microg gestodene and a 21-day regimen with 20 microg ethinyl estradiol and 150 microg desogestrel. Contraception. 2001;64:201-207.

35. Anderson FD, Hait H. A multicenter, randomized study of an extended cycle oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2003;68:89-96.

36. Anderson FD, Gibbons W, Portman D. Safety and efficacy of an extended-regimen oral contraceptive utilizing continuous low-dose ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:229-234.

37. Miller L, Hughes JP. Continuous combination oral contraceptive pills to eliminate withdrawal bleeding: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:653-661.

38. Kwiecien M, Edelman A, Nichols MD, et al. Bleeding patterns and patient acceptability of standard or continuous dosing regimens of a low-dose oral contraceptive: a randomized trial. Contraception. 2003;67:9-13.

39. Foidart JM, Sulak PJ, Schellschmidt I, Zimmermann D. Yasmin Extended Regimen Study Group. The use of an oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol and drospirenone in an extended regimen over 126 days. Contraception. 2006;73:34-40.

40. Sulak PJ, Kuehl TJ, Coffee A, Willis S. Prospective analysis of occurrence and management of breakthrough bleeding during an extended oral contraceptive regimen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:935-941.

41. Hurskainen R, et al. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:273-277.

Dr. Newmann reports no financial relationship relevant to this article. Dr. Darney receives support from Organon, is a consultant to Organon and Bayer, and is a speaker for Organon and Bayer.

Greater access to Plan B leads to increased—and faster—use

Now that Plan B is available OTC to both men and women 18 years and older,1 several questions are in order:

- What are the effects of this change?

- Does OTC access or provision of the drug in advance reduce condom or oral contraceptive use?

- Does it increase the number of sexual partners or rate of sexually transmitted disease (STD)?

- Does it reduce unintended pregnancy?

Several randomized trials have found that advance provision of EC not only increases its utilization, but causes it to be used sooner.2-7 Most of the trials conducted so far have compared advance provision of EC with counseling about EC or a prescription for it. Only one trial has included a pharmacy-access arm, and it was conducted before FDA approval of OTC status.3 It found that pharmacy access did not increase use of EC, compared with standard access (ie, returning to the clinic when EC was needed). It is too early to tell what effect OTC availability will have on the usage rate, but data so far support the practice of giving the patient a supply of EC rather than just a prescription.

Increased access to EC does not affect regular contraceptive behavior

Multiple studies have shown that advance provision of EC has no significant effect on the use of regular contraception. Studies have examined the impact of EC on both baseline oral contraceptive usage and condom usage and found no significant change in either among women who used EC during the study.3-6

… nor does it cause promiscuity or increase the rate of STD

Multiple studies have demonstrated that advance provision of EC does not increase the number of sexual partners or rate of STD.3-6 The largest of these studies compared both pharmacy access without a prescription and advance provision of EC to standard access. That study included 2,117 sexually active young women and found no difference in the rate of STD or number of sex partners among the three study groups.3 Smaller studies comparing advance pro-vision of EC with standard access also found no significant difference in these variables.8,9

No evidence of fewer unintended pregnancies—yet

We know that progestin-only EC can reduce unintended pregnancy by almost 90%.10 However, studies have not yet demonstrated such a decrease in the general population. One reason may be that the two studies that considered unintended pregnancy as a primary outcome3,9 were too small to detect a difference in pregnancy rates, or it may be that EC was underutilized by women in the studies.

Prescribing information for levonorgestrel emergency contraception (EC) recommends ingestion of the first 0.75-mg tablet within 72 hours (3 days) of a single act of unprotected intercourse, with the second tablet taken 12 hours after the first.11 However, data show that levonorgestrel EC can prevent pregnancy up to 5 days after intercourse. In a World Health Organization multicenter randomized trial of various EC regimens, levonorgestrel EC prevented 79% to 84% of expected pregnancies when taken within 1 to 3 days, and 60% to 63% when taken 4 to 5 days after intercourse.12 Randomized trials have also found that taking both 0.75-mg levonorgestrel pills simultaneously prevents pregnancy as effectively as taking them 12 hours apart.

Levonorgestrel EC prevents or delays ovulation by inhibiting the luteinizing hormone surge during the follicular phase.13 Secondary mechanisms of contraceptive action include thickening of the cervical mucus; decreased pH level, which immobilizes sperm; and decreased recovery of sperm from the uterus.14

Levonorgestrel intrauterine system has benefits beyond contraception

The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) has been shown to significantly decrease blood loss and increase hemoglobin and serum ferritin levels in women with idiopathic menorrhagia.15 The LNGIUS reduces blood loss to a greater degree (as much as 96% after 1 year) than do placebo, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antifibrinolytic medication, and oral contraceptives.16 In one study,16 the LNG-IUS was the only treatment that reduced menstrual bleeding to less than 80 mL/day—the upper limit of normal.

LNG-IUS compares favorably to endometrial ablation

The LNG-IUS provides nonoperative, local, and minimally invasive treatment of menorrhagia, producing clinical results similar to those of different endometrial ablation methods for dysfunctional uterine bleeding or menorrhagia. The LNG-IUS is comparable to endometrial resection in its reduction of blood loss, patient satisfaction, rate of amenorrhea, and recurrent menorrhagia.17 It also is equivalent to thermal balloon ablation in its reduction of bleeding and increased quality of life and hemoglobin level.18,19 And it produces a higher amenorrhea rate than expectant management after endometrial resection in women with adenomyosis, and averts the need for further procedures, such as hysterectomy and repeat resection.20

In many women, LNG-IUS renders hysterectomy unnecessary

In a controlled trial involving 56 women on a waiting list for hysterectomy, 64% of those who received the LNG-IUS and 14% of those in a control group removed themselves from the list at the end of 6 months because they were satisfied with symptom control (P.001>21 In a trial involving 236 women with menorrhagia randomized to LNG-IUS or hysterectomy, the groups had similar quality-of-life scores at 1 and 5 years of follow-up—and costs associated with the LNG-IUS were significantly lower than those associated with hysterectomy, even after 50 women randomized to the LNG-IUS opted for and underwent hysterectomy.41

Consider the LNG-IUS a first-line therapy for symptomatic fibroids

The LNG-IUS continuously decreases fibroid and uterine volume and blood loss and increases ferritin levels over time among women with symptomatic fibroids.22 It should therefore be routinely considered a first-line therapy for women with fibroids who wish to preserve their childbearing potential.

Endometrial hyperplasia is reduced

The LNG-IUS can prevent and induce regression of endometrial hyperplasia.23,24 In addition, it reduces bleeding and spotting among women using hormone replacement therapy.25,26 Studies also suggest it may be beneficial in the treatment of stage I endometrial cancer, although further research into this effect is needed.27

Endometriosis-related pain is eased

In a randomized trial comparing the LNG-IUS with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue among women with chronic pelvic pain due to endometriosis, both treatments reduced pain and improved psychological well-being to the same degree—but the LNG-IUS caused no systemic hypoestrogenic symptoms, unlike the GnRH analogue.28 In a randomized trial comparing the LNGIUS with expectant management among women who had undergone laparoscopic resection of endometriosis, women in the LNG-IUS arm had significantly decreased recurrent dysmenorrhea.29

In addition, the LNG-IUS is effective for as long as 5 years, can be used in conjunction with systemic estrogen, and is an effective contraceptive.

Continuous oral contraceptive regimens: 4 effective options

Oral contraceptives (OCs) can be prescribed for continuous use to achieve a number of different goals30:

- decrease the number of placebo days per cycle

- reduce the number of placebo weeks or withdrawal weeks per year

- eliminate withdrawal weeks from the cycle entirely

- reduce the incidence of breakthrough bleeding

Reduce the number of placebo days

Compared with the standard 28-day regimen (21 days of active pills followed by 7 days of placebo), extended regimens significantly reduce ovarian activity and produce smaller follicles and a lower estrogen level.31,32 Extended regimens may involve fewer days of placebo pills per cycle, or very small amounts of estrogen throughout the withdrawal week of the regimen. These modifications may translate into increased efficacy. In two randomized trials comparing extended regimens with a standard regimen, the extended regimens were highly effective, with a Pearl index of up to 1.29 (1.29 pregnancies for every 100 woman-years of use), and produced shorter withdrawal bleeds.33,34

Decrease the number of placebo or withdrawal weeks

The FDA approved the first OC to be packaged for extended use (Seasonale) in 2003. Each pack contains 84 active tablets of ethinyl estradiol (0.03 mg) and levonorgestrel (0.15 mg), followed by seven placebo pills. This highly effective regimen has a failure rate of 0.60 per 100 woman-years.35 Another extended-use OC (Seasonique) contains 7 days of ethinyl estradiol (10 μg) instead of placebo pills and may, therefore, suppress follicular development to an even greater degree during the withdrawal week.36

Extended cycles can be achieved with any monophasic OC in an off-label manner. Simply instruct the patient to take one active tablet for 42 consecutive days (known as “bicycling”) or for 63 consecutive days (“tricycling”), followed by 4 to 7 pill-free days.

Unscheduled bleeding with the 63-day regimen appears to be similar to the rate associated with the 21-day regimen.35 An extended-cycle regimen can be modified according to how often the user wants withdrawal bleeding.

Eliminate the withdrawal week

Perhaps the most radical extended-cycle regimen is continuous use of active pills with no placebo or withdrawal interval. This option is safe and acceptable to women, according to two small randomized trials and two prospective trials, but larger studies are needed to confirm these results.37-40 Continuous use for 1 year is associated with less bleeding, higher rates of amenorrhea, and similar side effects, compared with conventional regimens.37,38 Patient acceptance and satisfaction also are high,39 with most women choosing to keep taking the pill continuously. Lybrel, an OC designed for this purpose, contains 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and 90 μg of levonorgestrel and is intended to eliminate menses through 1 year of continuous use.

Reduce breakthrough bleeding

For women who experience unscheduled bleeding while taking an OC continuously, one option is to stop taking pills when breakthrough bleeding occurs and initiate a hormone-free interval. This approach was studied in a randomized trial in which women were scheduled to take an OC continuously for 168 days.40 Women who had persistent unscheduled bleeding for longer than 7 days were randomized to a 3-day hormone-free interval or continuation of the active pills. Those who continued taking active pills had more bleeding over the long term, and a large percentage found it necessary to institute a delayed hormone-free interval.

This option may be particularly useful for women who experience persistent breakthrough bleeding on a continuous regimen.40

Greater access to Plan B leads to increased—and faster—use

Now that Plan B is available OTC to both men and women 18 years and older,1 several questions are in order:

- What are the effects of this change?

- Does OTC access or provision of the drug in advance reduce condom or oral contraceptive use?

- Does it increase the number of sexual partners or rate of sexually transmitted disease (STD)?

- Does it reduce unintended pregnancy?

Several randomized trials have found that advance provision of EC not only increases its utilization, but causes it to be used sooner.2-7 Most of the trials conducted so far have compared advance provision of EC with counseling about EC or a prescription for it. Only one trial has included a pharmacy-access arm, and it was conducted before FDA approval of OTC status.3 It found that pharmacy access did not increase use of EC, compared with standard access (ie, returning to the clinic when EC was needed). It is too early to tell what effect OTC availability will have on the usage rate, but data so far support the practice of giving the patient a supply of EC rather than just a prescription.

Increased access to EC does not affect regular contraceptive behavior

Multiple studies have shown that advance provision of EC has no significant effect on the use of regular contraception. Studies have examined the impact of EC on both baseline oral contraceptive usage and condom usage and found no significant change in either among women who used EC during the study.3-6

… nor does it cause promiscuity or increase the rate of STD

Multiple studies have demonstrated that advance provision of EC does not increase the number of sexual partners or rate of STD.3-6 The largest of these studies compared both pharmacy access without a prescription and advance provision of EC to standard access. That study included 2,117 sexually active young women and found no difference in the rate of STD or number of sex partners among the three study groups.3 Smaller studies comparing advance pro-vision of EC with standard access also found no significant difference in these variables.8,9

No evidence of fewer unintended pregnancies—yet

We know that progestin-only EC can reduce unintended pregnancy by almost 90%.10 However, studies have not yet demonstrated such a decrease in the general population. One reason may be that the two studies that considered unintended pregnancy as a primary outcome3,9 were too small to detect a difference in pregnancy rates, or it may be that EC was underutilized by women in the studies.

Prescribing information for levonorgestrel emergency contraception (EC) recommends ingestion of the first 0.75-mg tablet within 72 hours (3 days) of a single act of unprotected intercourse, with the second tablet taken 12 hours after the first.11 However, data show that levonorgestrel EC can prevent pregnancy up to 5 days after intercourse. In a World Health Organization multicenter randomized trial of various EC regimens, levonorgestrel EC prevented 79% to 84% of expected pregnancies when taken within 1 to 3 days, and 60% to 63% when taken 4 to 5 days after intercourse.12 Randomized trials have also found that taking both 0.75-mg levonorgestrel pills simultaneously prevents pregnancy as effectively as taking them 12 hours apart.

Levonorgestrel EC prevents or delays ovulation by inhibiting the luteinizing hormone surge during the follicular phase.13 Secondary mechanisms of contraceptive action include thickening of the cervical mucus; decreased pH level, which immobilizes sperm; and decreased recovery of sperm from the uterus.14

Levonorgestrel intrauterine system has benefits beyond contraception

The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) has been shown to significantly decrease blood loss and increase hemoglobin and serum ferritin levels in women with idiopathic menorrhagia.15 The LNGIUS reduces blood loss to a greater degree (as much as 96% after 1 year) than do placebo, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antifibrinolytic medication, and oral contraceptives.16 In one study,16 the LNG-IUS was the only treatment that reduced menstrual bleeding to less than 80 mL/day—the upper limit of normal.

LNG-IUS compares favorably to endometrial ablation

The LNG-IUS provides nonoperative, local, and minimally invasive treatment of menorrhagia, producing clinical results similar to those of different endometrial ablation methods for dysfunctional uterine bleeding or menorrhagia. The LNG-IUS is comparable to endometrial resection in its reduction of blood loss, patient satisfaction, rate of amenorrhea, and recurrent menorrhagia.17 It also is equivalent to thermal balloon ablation in its reduction of bleeding and increased quality of life and hemoglobin level.18,19 And it produces a higher amenorrhea rate than expectant management after endometrial resection in women with adenomyosis, and averts the need for further procedures, such as hysterectomy and repeat resection.20

In many women, LNG-IUS renders hysterectomy unnecessary

In a controlled trial involving 56 women on a waiting list for hysterectomy, 64% of those who received the LNG-IUS and 14% of those in a control group removed themselves from the list at the end of 6 months because they were satisfied with symptom control (P.001>21 In a trial involving 236 women with menorrhagia randomized to LNG-IUS or hysterectomy, the groups had similar quality-of-life scores at 1 and 5 years of follow-up—and costs associated with the LNG-IUS were significantly lower than those associated with hysterectomy, even after 50 women randomized to the LNG-IUS opted for and underwent hysterectomy.41

Consider the LNG-IUS a first-line therapy for symptomatic fibroids

The LNG-IUS continuously decreases fibroid and uterine volume and blood loss and increases ferritin levels over time among women with symptomatic fibroids.22 It should therefore be routinely considered a first-line therapy for women with fibroids who wish to preserve their childbearing potential.

Endometrial hyperplasia is reduced

The LNG-IUS can prevent and induce regression of endometrial hyperplasia.23,24 In addition, it reduces bleeding and spotting among women using hormone replacement therapy.25,26 Studies also suggest it may be beneficial in the treatment of stage I endometrial cancer, although further research into this effect is needed.27

Endometriosis-related pain is eased

In a randomized trial comparing the LNG-IUS with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue among women with chronic pelvic pain due to endometriosis, both treatments reduced pain and improved psychological well-being to the same degree—but the LNG-IUS caused no systemic hypoestrogenic symptoms, unlike the GnRH analogue.28 In a randomized trial comparing the LNGIUS with expectant management among women who had undergone laparoscopic resection of endometriosis, women in the LNG-IUS arm had significantly decreased recurrent dysmenorrhea.29

In addition, the LNG-IUS is effective for as long as 5 years, can be used in conjunction with systemic estrogen, and is an effective contraceptive.

Continuous oral contraceptive regimens: 4 effective options

Oral contraceptives (OCs) can be prescribed for continuous use to achieve a number of different goals30:

- decrease the number of placebo days per cycle

- reduce the number of placebo weeks or withdrawal weeks per year

- eliminate withdrawal weeks from the cycle entirely

- reduce the incidence of breakthrough bleeding

Reduce the number of placebo days

Compared with the standard 28-day regimen (21 days of active pills followed by 7 days of placebo), extended regimens significantly reduce ovarian activity and produce smaller follicles and a lower estrogen level.31,32 Extended regimens may involve fewer days of placebo pills per cycle, or very small amounts of estrogen throughout the withdrawal week of the regimen. These modifications may translate into increased efficacy. In two randomized trials comparing extended regimens with a standard regimen, the extended regimens were highly effective, with a Pearl index of up to 1.29 (1.29 pregnancies for every 100 woman-years of use), and produced shorter withdrawal bleeds.33,34

Decrease the number of placebo or withdrawal weeks

The FDA approved the first OC to be packaged for extended use (Seasonale) in 2003. Each pack contains 84 active tablets of ethinyl estradiol (0.03 mg) and levonorgestrel (0.15 mg), followed by seven placebo pills. This highly effective regimen has a failure rate of 0.60 per 100 woman-years.35 Another extended-use OC (Seasonique) contains 7 days of ethinyl estradiol (10 μg) instead of placebo pills and may, therefore, suppress follicular development to an even greater degree during the withdrawal week.36

Extended cycles can be achieved with any monophasic OC in an off-label manner. Simply instruct the patient to take one active tablet for 42 consecutive days (known as “bicycling”) or for 63 consecutive days (“tricycling”), followed by 4 to 7 pill-free days.

Unscheduled bleeding with the 63-day regimen appears to be similar to the rate associated with the 21-day regimen.35 An extended-cycle regimen can be modified according to how often the user wants withdrawal bleeding.

Eliminate the withdrawal week

Perhaps the most radical extended-cycle regimen is continuous use of active pills with no placebo or withdrawal interval. This option is safe and acceptable to women, according to two small randomized trials and two prospective trials, but larger studies are needed to confirm these results.37-40 Continuous use for 1 year is associated with less bleeding, higher rates of amenorrhea, and similar side effects, compared with conventional regimens.37,38 Patient acceptance and satisfaction also are high,39 with most women choosing to keep taking the pill continuously. Lybrel, an OC designed for this purpose, contains 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and 90 μg of levonorgestrel and is intended to eliminate menses through 1 year of continuous use.

Reduce breakthrough bleeding

For women who experience unscheduled bleeding while taking an OC continuously, one option is to stop taking pills when breakthrough bleeding occurs and initiate a hormone-free interval. This approach was studied in a randomized trial in which women were scheduled to take an OC continuously for 168 days.40 Women who had persistent unscheduled bleeding for longer than 7 days were randomized to a 3-day hormone-free interval or continuation of the active pills. Those who continued taking active pills had more bleeding over the long term, and a large percentage found it necessary to institute a delayed hormone-free interval.

This option may be particularly useful for women who experience persistent breakthrough bleeding on a continuous regimen.40

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves over-the-counter access for Plan B for women 18 and older; prescription remains required for those 17 and under [August 24, 2006]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01436.html. Accessed July 11, 2007.

2. Harper CC, Cheong M, Rocca CH, Darney PD, Raine TR. The effect of increased access to emergency contraception among young adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:483-491.

3. Raine TR, Harper CC, Rocca CH, et al. Direct access to emergency contraception through pharmacies and effect on unintended pregnancy and STIs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:54-62.

4. Raymond EG, Trussell J, Polis CB. Population effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:181-188.

5. Walsh TL, Frezieres RG. Patterns of emergency contraception use by age and ethnicity from a randomized trial comparing advance provision and information only. Contraception. 2006;74:110-117.

6. Jackson RA, Schwarz EB, Freedman L, Darney PD. Advance supply of emergency contraception. Effect on use and usual contraception—a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:8-16.

7. Hu X, Cheng L, Hua X, Glasier A. Advanced provision of emergency contraception to postnatal women in China makes no difference in abortion rates: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2005;72:111-116.

8. Gold MA, Wolford JE, Smith KA, Parker AM. The effects of advance provision of emergency contraception on adolescent women’s sexual and contraceptive behaviors. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17:87-96.

9. Raymond EG, Stewart F, Weaver M, Monteith C, Van Der Pol B. Impact of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1098-1106.

10. Trussell J, Ellertson C, Stewart F. The effectiveness of the Yuzpe regimen of emergency contraception. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28:58-64, 87.

11. Plan B. [package insert] Pomona, NY: Duramed Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2006.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1803-1810.

13. Durand M, del Carmen Cravioto M, Raymond EG, et al. On the mechanisms of action of short-term levonorgestrel administration in emergency contraception. Contraception. 2001;64:227-234.

14. Croxatto HB, Devoto L, Durand M, et al. Mechanism of action of hormonal preparations used for emergency contraception: a review of the literature. Contraception. 2001;63:111-121.

15. Xiao B, Wu SC, Chong J, et al. Therapeutic effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:963-969.

16. Milsom I, Andersson K, Andersch B, Rybo G. A comparison of flurbiprofen, tranexamic acid, and a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive device in the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:879-883.

17. Crosignani PG, Vercellini P, Mosconi P, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus hysteroscopic endometrial resection in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:257-263.

18. Soysal M, Soysal S, Ozer S. A randomized controlled trial of levonorgestrel releasing IUD and thermal balloon ablation in the treatment of menorrhagia. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2002;124:213-219.

19. Barrington JW, Arunkalaivanan AS, Abdel-Fattah M. Comparison between the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) and thermal balloon ablation in the treatment of menorrhagia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;108:72-74.

20. Maia H, Jr, Maltez A, Coelho G, et al. Insertion of Mirena after endometrial resection in patients with adenomyosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:512-516.

21. Lahteenmaki P, Haukkamaa M, Puolakka J, et al. Open randomised study of use of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system as alternative to hysterectomy. BMJ. 1998;316:1122-1126.

22. Grigorieva V, Chen-Mok M, Tarasova M, Mikhailov A. Use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system to treat bleeding related to uterine leiomyomas. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1194-1198.

23. Scarselli G, Tantini C, Colafranceschi M, et al. Levonorgestrel-nova-T and precancerous lesions of the endometrium. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1988;9:284-286.

24. Perino A, Quartararo P, Catinella E, et al. Treatment of endometrial hyperplasia with levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine devices. Acta Eur Fertil. 1987;18:137-140.

25. Ettinger B, Pressman A, Silver P. Effect of age on reasons for initiation and discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause. 1999;6:282-289.

26. Andersson K, Mattson LA, Rybo G, Stadberg E. Intrauterine release of levonorgestrel—a new way of adding progestogen in hormone replacement therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:963-967.

27. Montz FJ, Bristow RE, Bovicelli A, et al. Intrauterine progesterone treatment of early endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:651-657.

28. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1993-1998.

29. Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, Aimi G, Zaina B, Crosignani PG. Comparison of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:305-309.

30. Steinauer J, Autry AM. Extended cycle combined hormonal contraception. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:43-55, viii.

31. Spona J, Elstein M, Feichtinger W, et al. Shorter pill-free interval in combined oral contraceptives decreases follicular development. Contraception. 1996;54:71-77.

32. Sullivan H, Furniss H, Spona J, Elstein M. Effect of 21-day and 24-day oral contraceptive regimens containing gestodene (60 microg) and ethinyl estradiol (15 microg) on ovarian activity. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:115-120.

33. Bachmann G, Sulak PJ, Sampson-Landers C, Benda N, Marr J. Efficacy and safety of a low-dose 24-day combined oral contraceptive containing 20 micrograms ethinylestradiol and 3 mg drospirenone. Contraception. 2004;70:191-198.

34. Endrikat J, Cronin M, Gerlinger C, Ruebig A, Schmidt W, Düsterburg B. Open, multicenter comparison of efficacy, cycle control, and tolerability of a 23-day oral contraceptive regimen with 20 microg ethinyl estradiol and 75 microg gestodene and a 21-day regimen with 20 microg ethinyl estradiol and 150 microg desogestrel. Contraception. 2001;64:201-207.

35. Anderson FD, Hait H. A multicenter, randomized study of an extended cycle oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2003;68:89-96.

36. Anderson FD, Gibbons W, Portman D. Safety and efficacy of an extended-regimen oral contraceptive utilizing continuous low-dose ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:229-234.

37. Miller L, Hughes JP. Continuous combination oral contraceptive pills to eliminate withdrawal bleeding: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:653-661.

38. Kwiecien M, Edelman A, Nichols MD, et al. Bleeding patterns and patient acceptability of standard or continuous dosing regimens of a low-dose oral contraceptive: a randomized trial. Contraception. 2003;67:9-13.

39. Foidart JM, Sulak PJ, Schellschmidt I, Zimmermann D. Yasmin Extended Regimen Study Group. The use of an oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol and drospirenone in an extended regimen over 126 days. Contraception. 2006;73:34-40.

40. Sulak PJ, Kuehl TJ, Coffee A, Willis S. Prospective analysis of occurrence and management of breakthrough bleeding during an extended oral contraceptive regimen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:935-941.

41. Hurskainen R, et al. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:273-277.

Dr. Newmann reports no financial relationship relevant to this article. Dr. Darney receives support from Organon, is a consultant to Organon and Bayer, and is a speaker for Organon and Bayer.

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves over-the-counter access for Plan B for women 18 and older; prescription remains required for those 17 and under [August 24, 2006]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01436.html. Accessed July 11, 2007.

2. Harper CC, Cheong M, Rocca CH, Darney PD, Raine TR. The effect of increased access to emergency contraception among young adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:483-491.

3. Raine TR, Harper CC, Rocca CH, et al. Direct access to emergency contraception through pharmacies and effect on unintended pregnancy and STIs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:54-62.

4. Raymond EG, Trussell J, Polis CB. Population effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:181-188.

5. Walsh TL, Frezieres RG. Patterns of emergency contraception use by age and ethnicity from a randomized trial comparing advance provision and information only. Contraception. 2006;74:110-117.

6. Jackson RA, Schwarz EB, Freedman L, Darney PD. Advance supply of emergency contraception. Effect on use and usual contraception—a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:8-16.

7. Hu X, Cheng L, Hua X, Glasier A. Advanced provision of emergency contraception to postnatal women in China makes no difference in abortion rates: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2005;72:111-116.

8. Gold MA, Wolford JE, Smith KA, Parker AM. The effects of advance provision of emergency contraception on adolescent women’s sexual and contraceptive behaviors. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17:87-96.

9. Raymond EG, Stewart F, Weaver M, Monteith C, Van Der Pol B. Impact of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1098-1106.

10. Trussell J, Ellertson C, Stewart F. The effectiveness of the Yuzpe regimen of emergency contraception. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28:58-64, 87.

11. Plan B. [package insert] Pomona, NY: Duramed Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2006.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1803-1810.

13. Durand M, del Carmen Cravioto M, Raymond EG, et al. On the mechanisms of action of short-term levonorgestrel administration in emergency contraception. Contraception. 2001;64:227-234.

14. Croxatto HB, Devoto L, Durand M, et al. Mechanism of action of hormonal preparations used for emergency contraception: a review of the literature. Contraception. 2001;63:111-121.

15. Xiao B, Wu SC, Chong J, et al. Therapeutic effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:963-969.

16. Milsom I, Andersson K, Andersch B, Rybo G. A comparison of flurbiprofen, tranexamic acid, and a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive device in the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:879-883.

17. Crosignani PG, Vercellini P, Mosconi P, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus hysteroscopic endometrial resection in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:257-263.

18. Soysal M, Soysal S, Ozer S. A randomized controlled trial of levonorgestrel releasing IUD and thermal balloon ablation in the treatment of menorrhagia. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2002;124:213-219.

19. Barrington JW, Arunkalaivanan AS, Abdel-Fattah M. Comparison between the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) and thermal balloon ablation in the treatment of menorrhagia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;108:72-74.

20. Maia H, Jr, Maltez A, Coelho G, et al. Insertion of Mirena after endometrial resection in patients with adenomyosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:512-516.

21. Lahteenmaki P, Haukkamaa M, Puolakka J, et al. Open randomised study of use of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system as alternative to hysterectomy. BMJ. 1998;316:1122-1126.

22. Grigorieva V, Chen-Mok M, Tarasova M, Mikhailov A. Use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system to treat bleeding related to uterine leiomyomas. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1194-1198.

23. Scarselli G, Tantini C, Colafranceschi M, et al. Levonorgestrel-nova-T and precancerous lesions of the endometrium. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1988;9:284-286.

24. Perino A, Quartararo P, Catinella E, et al. Treatment of endometrial hyperplasia with levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine devices. Acta Eur Fertil. 1987;18:137-140.

25. Ettinger B, Pressman A, Silver P. Effect of age on reasons for initiation and discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause. 1999;6:282-289.

26. Andersson K, Mattson LA, Rybo G, Stadberg E. Intrauterine release of levonorgestrel—a new way of adding progestogen in hormone replacement therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:963-967.

27. Montz FJ, Bristow RE, Bovicelli A, et al. Intrauterine progesterone treatment of early endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:651-657.

28. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1993-1998.

29. Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, Aimi G, Zaina B, Crosignani PG. Comparison of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:305-309.

30. Steinauer J, Autry AM. Extended cycle combined hormonal contraception. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:43-55, viii.

31. Spona J, Elstein M, Feichtinger W, et al. Shorter pill-free interval in combined oral contraceptives decreases follicular development. Contraception. 1996;54:71-77.

32. Sullivan H, Furniss H, Spona J, Elstein M. Effect of 21-day and 24-day oral contraceptive regimens containing gestodene (60 microg) and ethinyl estradiol (15 microg) on ovarian activity. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:115-120.

33. Bachmann G, Sulak PJ, Sampson-Landers C, Benda N, Marr J. Efficacy and safety of a low-dose 24-day combined oral contraceptive containing 20 micrograms ethinylestradiol and 3 mg drospirenone. Contraception. 2004;70:191-198.

34. Endrikat J, Cronin M, Gerlinger C, Ruebig A, Schmidt W, Düsterburg B. Open, multicenter comparison of efficacy, cycle control, and tolerability of a 23-day oral contraceptive regimen with 20 microg ethinyl estradiol and 75 microg gestodene and a 21-day regimen with 20 microg ethinyl estradiol and 150 microg desogestrel. Contraception. 2001;64:201-207.

35. Anderson FD, Hait H. A multicenter, randomized study of an extended cycle oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2003;68:89-96.

36. Anderson FD, Gibbons W, Portman D. Safety and efficacy of an extended-regimen oral contraceptive utilizing continuous low-dose ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:229-234.

37. Miller L, Hughes JP. Continuous combination oral contraceptive pills to eliminate withdrawal bleeding: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:653-661.

38. Kwiecien M, Edelman A, Nichols MD, et al. Bleeding patterns and patient acceptability of standard or continuous dosing regimens of a low-dose oral contraceptive: a randomized trial. Contraception. 2003;67:9-13.

39. Foidart JM, Sulak PJ, Schellschmidt I, Zimmermann D. Yasmin Extended Regimen Study Group. The use of an oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol and drospirenone in an extended regimen over 126 days. Contraception. 2006;73:34-40.

40. Sulak PJ, Kuehl TJ, Coffee A, Willis S. Prospective analysis of occurrence and management of breakthrough bleeding during an extended oral contraceptive regimen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:935-941.

41. Hurskainen R, et al. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:273-277.

Dr. Newmann reports no financial relationship relevant to this article. Dr. Darney receives support from Organon, is a consultant to Organon and Bayer, and is a speaker for Organon and Bayer.

Everything you need to know about the contraceptive implant

On July 17, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved what may be the most effective hormonal contraceptive ever developed, a single-rod implant that goes by the trade name Implanon. The implant contains 68 mg of etonogestrel (ENG), the active metabolite of desogestrel, in a membrane of ethylene vinyl acetate. In clinical trials involving 20,648 cycles of exposure, only 6 pregnancies occurred, for a cumulative Pearl Index of 0.38 per 100 woman-years.1

This article reviews:

- the 2 contraceptive mechanisms

- indications and patient selection

- pharmacology, safety, adverse effects

- patient satisfaction and discontinuation rates

- insertion and removal

- key points of patient counseling

Unlike Norplant, a multi-rod implant which garnered a million American users before it was removed from the market, the single-rod implant is easy to insert and remove. Before you can order the implant, you must complete a manufacturer-sponsored training program.

Which patients are suitable candidates?

Because the subdermal implant contains only progestin, provides up to 3 years of protection, and requires no daily, weekly, or even monthly action on the part of the user, it is well-suited for:

- Women who wish to or need to avoid estrogen

- Teens who find adherence to a contraceptive regimen difficult

- Healthy adult women who desire long-term protection

- Women who are breastfeeding

Pros and cons

Advantages include:

- Cost. A study2 of 15 contraceptive methods found the implant cost-effective compared to short-acting methods, provided it was used long-term. As of press time, the manufacturer had not released the price.

- Short fertility-recovery time.

- No serious cardiovascular effects.3

Drawbacks. Progestin-only contraceptives also have disadvantages:

- Implants require a minor surgical procedure by trained clinicians for insertion and removal.

- Cost-effectiveness depends on duration of use; early discontinuation negates this benefit.2

- The implant does not protect against sexually transmitted infections—this is a disadvantage of all contraceptive methods except condoms and, perhaps, other barrier methods.

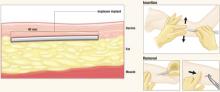

After Implanon is inserted just below the dermis 6 to 8 cm above the elbow crease on the inner aspect of the arm, it remains effective for up to 3 years. To remove it, make a 2-mm incision at the distal tip of the implant and push on the other end of the rod until it pops out.

The implant resides beneath the dermis but above the subcutaneous fat. It remains palpable but invisible, releasing about 60 μg of etonogestrel per day

Images: Rich Larocco

The Norplant experience

Research and development of progestin-only subdermal implants began more than 35 years ago, but early research involving very-low-dose implants found that they did not prevent ectopic pregnancies. This problem ended with Norplant, a 6-capsule implant using the potent progestin levonorgestrel (LNG).

Norplant was highly effective. Over 7 years of use, fewer than 1% of women became pregnant.4 Despite low pregnancy rates and few serious side effects, limitations in component supplies and negative media coverage on complications with removal led to its withdrawal in 2002, leaving no implant available in the US.5

The antiestrogenic effect

Long-acting, progestin-only contraceptives such as the new implant, the LNG-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena), and injectable methods (Depo-Provera) are safer than oral contraceptives (OCs) because they lack estrogen, which can provoke deep venous thrombosis.6,7

LNG, the gonane progestin used in Norplant, binds with high affinity to the progesterone, androgen, mineralocorticoid, and glucocorticoid receptors, but not to estrogen receptors. ENG, also known as 3-keto-desogestrel, demonstrates no estrogenic, anti-inflammatory, or mineralocorticoid activity, but has shown weak androgenic and anabolic activity, as well as strong antiestrogenic activity.

Unlike LNG, which binds mainly to sex hormone-binding globulin, ENG binds mainly to albumin, which is not affected by varying endogenous or exogenous estradiol levels. The safety of ENG has been demonstrated in studies of combined estrogen-progestin OCs and progestin-only OCs that use desogestrel as a component.

The progestin-only implant has 2 primary mechanisms:

- Inhibition of ovulation

- Restriction of sperm penetration of cervical mucus28

Ovulation is suppressed. LNG implants disrupt follicular growth and inhibit ovulation by exerting negative feedback on the hypothalamic–pituitary axis, causing a variety of changes, from anovulation to insufficient luteal function. A few women using LNG implants have quiescent ovaries, but most begin to ovulate as LNG blood concentrations gradually fall.29 The ENG implant suppresses ovulation by altering the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis and down-regulating the luteinizing hormone surge, which is required to support the production, growth, and maturation of ovarian follicles.11

Oocytes are not fertilized, even if follicles grow during use of the progestin implant. If the follicle ruptures, abnormalities of the ovulatory process prevent release of a viable egg.

Sperm cannot penetrate the cervical mucus. The antiestrogenic action of the progestin renders the cervical mucus viscous, scanty, and impenetrable by sperm.12

Contraceptive effects occur before fertilization

No signs of embryonic development have been found among implant users, indicating the implant lacks abortifacient properties.

Desogestrel in combination with ethinyl estradiol may slightly increase the attributable risk of deep venous thrombosis, but this response has not been shown without estrogen.

Design features

The single-rod design means little discomfort for patients at insertion or removal, an unobtrusive implant, and almost no scarring. Insertion and removal are predictably brief. In US and European trials, which began 10 years ago, average insertion time was 1 minute, and removal time was 3 minutes. In contrast, Norplant required up to 10 minutes to insert and 1 hour to remove.8

Because only 1 rod is implanted, there is no risk of dislocating previously placed capsules.9 Nor is it necessary, as it was with Norplant, to create channels under the skin, which made implants difficult to palpate after insertion.

Finally, ethylene vinyl acetate, the plastic from which Implanon is made, is less likely than Norplant’s Silastic to form a fibrous sheath that can prolong removal.10

Pharmacology of Implanon

Implanon is a single nonbiodegradable rod of 40% ethylene vinyl acetate and 60% ENG (40 mm×2 mm) covered with a membrane of rate-controlling ethylene vinyl acetate 0.06 mm thick.

Bioavailability

The 68 mg of ENG contained in the rod are initially absorbed by the body at a rate of 60 μg per day, slowly declining to 30 μg per day after 2 years.

Peak serum concentrations (266 pg/mL) of ENG are achieved within 1 day after insertion, effectively suppressing ovulation (which requires 90 pg/mL ENG or more).11,12

The steady release of ENG into the circulation avoids first-pass effects on the liver.

The bioavailability of ENG remains nearly 100% throughout 2 years of use. The elimination half-life of ENG is 25 hours, compared with 42 hours for Norplant’s LNG.

Rapid return to ovulation

After removal, serum ENG concentrations become undetectable within 1 week, and ovulation resumes in 94% of women within 3 to 6 weeks after the implant is removed.11,12

Efficacy and safety

Liver enzyme-inducing drugs lower ENG levels

Like other contraceptive steroids, serum levels of ENG are reduced in women taking liver enzyme-inducing drugs such as rifampin, griseofulvin, phenylbutazone, phenytoin, and carbamazepine, as well as anti-HIV protease inhibitors. Pregnancies were reported among Australian women using Implanon along with some of these antiepileptic drugs.13

Equal efficacy in obese women?

The efficacy of the single-rod implant was studied in clinical trials involving 20,648 cycles of use.1 Only 6 pregnancies occurred in this population—2 each in years 1, 2, and 3 of use. None of the women who weighed 154 lb (70 kg) or more became pregnant.12

However, questions remain as to whether the new implant will maintain its high efficacy in obese women, as it has not been studied in women weighing more than 130% of their ideal body weight. Serum levels of ENG are inversely related to body weight and diminish over time, but increased pregnancy rates in obese women have not been reported.

Potential for ectopic pregancy

Suspect ectopic pregnancy in the rare event that a woman becomes pregnant or experiences lower abdominal pain.1 The reason: Pregnancies in women using contraceptive implants are more likely to be ectopic than are pregnancies in the general population. Ovulation is possible in the third year of use, but intrauterine pregnancies are very rare.1

Limited metabolic effects

Published studies indicate that the metabolic effects of the ENG implant are unlikely to be clinically significant, including its effects on lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, liver function, hemostasis, blood pressure, and thyroid and adrenal function.14-17

Adverse event rates

Overall, implants, including the ENG implant, appear to be safe. The rate of adverse events is comparable to rates in nonusers18 (death, neoplastic disease, cardiovascular events, anemia, hypertension, bone-density changes, diabetes, gall bladder disease, thrombocytopenia, and pelvic inflammatory disease).

Lactation

In a study comparing 42 lactating mother–infant pairs using the ENG implant, compared with 38 pairs using intrauterine devices, there were no significant differences in milk volume, milk constituents, timing and amount of supplementary food, or infant growth rates.19

Because it contains no estrogen, Implanon is a good choice for immediate postpartum contraception.

Insertion and removal

Although the ENG implant is designed to facilitate rapid, simple insertion and removal, clinicians require training in Implanon-specific technique.20 Insertion takes an average of 1 to 2 minutes.21

The disposable trocar comes preloaded,22 and the needle tip has 2 cutting edges with different slopes. The extreme tip has a greater angle and is sharp to allow penetration through the skin. The second upper angle is smaller, and the corresponding edge is unsharpened to reduce the risk of placing the implant in muscle tissue.

Subdermal placement is imperative for efficacy and easy removal.

Insertion technique

Have the patient lie on the examination table with her nondominant arm flexed at the elbow and her hand next to her ear. Identify and mark the insertion site using a sterile marker, and apply any necessary local anesthetic. The insertion site should be 6 to 8 cm above the elbow crease on the inner aspect of the arm. Also mark the skin 6 to 8 cm proximal to the first mark; this serves as a guide during insertion.

Remove Implanon from its package and, with the shield still on the needle, confirm the presence of the implant (a white cylinder) within the needle tip. Remove the needle shield, holding the inserter upright to prevent the implant from falling out. Apply countertraction to the skin at the insertion point and, holding the inserter at an angle no greater than 20 degrees, insert the needle tip into the skin with the beveled side up. Lower the inserter to a horizontal position, lifting the skin with the needle tip without removing the tip from the subdermal connective tissue, and insert the needle to its full length.

Next, break the seal of the applicator by pressing the obturator support, and rotate the obturator 90% (in regard to the needle) in either direction. At this point, the insertion process is the opposite of an injection: Hold the obturator in place and retract the cannula.

After insertion, the implant may not be visible but must remain palpable.1

Timing the insertion. Placement should occur at one of the following times:

- For women who have not been using contraception or who have been using a nonhormonal method, insert the implant between days 1 and 5 of menses.

- For women changing from a combination or progestin-only OC, insert the implant any time during pill-taking.

- For women changing from injectable contraception, insert the implant on the date the next injection is scheduled.

- For women using the IUD, insertion can take place at any time.

Additional birth control for 7 days

Advise all women to use an additional barrier method of contraception for 7 days following insertion, unless insertion directly follows an abortion (in which case, no additional contraception is needed).

In all cases, exclude pregnancy before inserting the implant, although there is no evidence that hormonal contraceptives cause birth defects.

Removal technique

The ENG implant can be removed at any time at the woman’s discretion, but will remain effective for 3 years.

Removal requires a 2-mm incision at the distal tip of the implant. The other end of the rod is then pushed until the rod pops out of the incision.9

Mean removal time is 2.6 to 5.4 minutes.22

In rare cases, the ENG implant cannot be found when the time comes for removal, and special procedures, including sonographic determination of location and sonographically guided removal, are required.

Pain, swelling, redness, and hematoma have been reported during insertion and removal.

Because ovulation resumes rapidly following removal, women still desiring contraception should begin another method immediately or have a new rod inserted through the removal incision.

Tell patients to expect altered bleeding

Side effects associated with the ENG implant include menstrual irregularities:

- infrequent bleeding, 26.9%

- amenorrhea, 18.6%

- prolonged bleeding, 15.1%

- frequent bleeding, 7.4%

Other effects include weight gain, 20.7%; acne, 15.3%; breast pain, 9.1%; and headache, 8.5%.8,18

These symptoms rarely provoke discontinuation. Women using any progestin-only method will have changed bleeding patterns; it is estrogen, along with regular progestin withdrawal, that provides predictable uterine bleeding.23,24

A comparison of bleeding patterns in ENG implant users and LNG implant users found a lower mean number of bleeding/spotting days with the former (15.9–19.3 vs 19.4–21.6; P=.0169).25 Because total uterine blood loss is reduced, users of progestin-only contraceptives (as well as OCs) are less likely to be anemic.

The same comparison25 found that users of ENG implants had more variable bleeding patterns than users of LNG implants. Unfortunately, it is impossible to predict which patterns a woman is likely to experience.

The ENG implant reduced or eliminated menstrual pain in 88% of women who previously experienced dysmenorrhea; pain increased in only 2% of ENG implant users.18

Most women liked the implant

Despite side effects and the need for a physician to insert and remove the implants, most women are satisfied with the method, citing its long duration, convenience, and high efficacy.26,27

Discontinuation rates

Nevertheless, some women do choose to discontinue the method before 3 years are up. Discontinuation rates range from 30.2% in Europe and Canada to 0.9% in Southeast Asia.18,22 Bleeding irregularities are the most commonly cited reason for discontinuation, as they were for Norplant.

A meta-analysis of 13 studies published between 1989 and 1992 found that, among 1,716 women using the ENG implant, 5.3% discontinued in months 1 to 6, 6.4% discontinued in months 7 to 12, 4.1% discontinued in months 13 to 18, and 2.8% discontinued in months 19 to 24. Overall, 82% of women continued to use the ENG implant for up to 24 months.8

Lack of training, lack of counseling, lack of success

When the ENG implant was introduced in Australia in 2001, an unexpectedly high number of unintended pregnancies were reported: 100 pregnancies during the first 18 months.13 Almost universally, these events were traced to improper insertion by untrained clinicians, as well as poor patient selection, timing, and counseling.

In response, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners developed policies for adequate documentation of proper insertion procedures and patient education. The problems disappeared.13

Preinsertion counseling and postinsertion follow-up are essential for continued use of implants because they increase the patient’s satisfaction with the method and help minimize costly removals.

What to advise patients30

- Strongly stress the likelihood of changes in bleeding patterns

- Lack of inherent protection against sexually transmitted infections, and importance of protective measures (though the implant likely reduces the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease)

- User-specific lifestyle and health advice, such as the need for supplemental contraception in some women during the first 7 days of use

- Pros and cons of implants compared with other methods

- The date when removal is indicated1

Consent form

The patient should sign a consent form, which should be included in her medical record.

Extensive, worldwide experience

Already the 6-capsule and 2-rod LNG implants and the single-rod ENG implant have been used successfully by millions of women. The benefits are high efficacy, long duration, absence of estrogen, ease of use, reversibility, and safety.

Dr. Darney reports that he is a consultant to Organon and a speaker for Barr Laboratories, Berlex, and Organon.

1. Implanon [package insert]. Roseland, NJ: Organon; 2006.

2. Trussell J, Leveque JA, Koenig JD, et al. The economic value of contraception: a comparison of 15 methods. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:494-503.

3. Diaz S, Pavez M, Cardenas H, Croxatto HB. Recovery of fertility and outcome of planned pregnancies after the removal of Norplant subdermal implants or copper-T IUDs. Contraception. 1987;35:569-579.

4. Sivin I, Mishell DR, Jr, Darney P, Wan L, Christ M. Levonorgestrel capsule implants in the United States: a 5-year study. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:337-344.

5. Kuiper H, Miller S, Martinez E, Loeb L, Darney PD. Urban adolescent females’ views on the implant and contraceptive decisionmaking: a double paradox. Fam Plann Perspect. 1997;29:167-172.

6. Fu H, Darroch JE, Haas T, Ranjit N. Contraceptive failure rates: new estimates from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:56-63.

7. Meirik O, Farley TMM, Sivin I, for the International Collaborative Post-Marketing Surveillance of Norplant. Safety and efficacy of levonorgestrel implant, intrauterine device, and sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:539.-

8. Croxatto HB, Urbancsek J, Massai R, Coelingh Bennink H, van Beek A. A multicentre efficacy and safety study of the single contraceptive implant Implanon. Implanon Study Group. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:976-981.

9. Zieman M, Klaisle C, Walker D, Bahisteri E, Darney P. Fingers versus instruments for removing levonorgestrel contraceptive implants (Norplant). J Gynecol Tech. 1997;3:213.-

10. Meckstroth K, Darney PD. Implantable contraception. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:781-815.

11. Markarainen L, van Beek A, Tuomiyaara L, Asplund B, Bennink HC. Ovarian function during the use of a single contraceptive implant (Implanon) compared with Norplant. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:714-721.

12. Croxatto HB, Mäkäräinen L. The pharmacodynamics and efficacy of Implanon. Contraception. 1998;58:91S-97S.

13. Harrison-Woolrych M, Hill R. Unintended pregnancies with the etonogestrel implant (Implanon): a case series from post-marketing experience in Australia. Contraception. 2005;71:306-308.

14. Mascarenhas L, van Beek A, Bennink H, Newton J. Twenty-four month comparison of apolipoproteins A-1, A-II and B in contraceptive implant users (Norplant and Implanon) in Birmingham, United Kingdom. Contraception. 1998;58:215-219.

15. Biswas A, Viegas OA, Bennink HJ, Korver T, Ratnam SS. Effect of Implanon use on selected parameters of thyroid and adrenal function. Contraception. 2000;62:247-251.

16. Biswas A, Viegas OA, Coeling Bennink JH, Korver T, Ratnam SS. Implanon contraceptive implants: effects on carbohydrate metabolism. Contraception. 2001;63:137-141.

17. Biswas A, Viegas OA, Roy AC. Effect of Implanon and Norplant subdermal contraceptive implants on serum lipids-a randomized comparative study. Contraception. 2003;68:189-193.

18. Rekers H, Affandi B. Implanon studies conducted in Indonesia. Contraception. 2004;70:433.-

19. Reinprayoon D, Taneepanichskul S, Bunyavejchevin S, et al. Effects of the etonogestrel-releasing contraceptive implant (Implanon) on parameters of breastfeeding compared to those of an intrauterine device. Contraception. 2000;62:239-246.