User login

The Basement Flight

A 14-year-old girl with a history of asthma presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with three months of persistent, nonproductive cough, and progressive shortness of breath. She reported fatigue, chest tightness, orthopnea, and dyspnea with exertion. She denied fever, rhinorrhea, congestion, hemoptysis, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

Her age and past medical history of asthma are incongruent with her new symptoms, as asthma is typified by intermittent exacerbations, not progressive symptoms. Thus, another process, in addition to asthma, is most likely present; it is also important to question the accuracy of previous diagnoses in light of new information. Her symptoms may signify an underlying cardiopulmonary process, such as infiltrative diseases (eg, lymphoma or sarcoidosis), atypical infections, genetic conditions (eg, variant cystic fibrosis), autoimmune conditions, or cardiomyopathy. A detailed symptom history, family history, and careful physical examination will help expand and then refine the differential diagnosis. At this stage, typical infections are less likely.

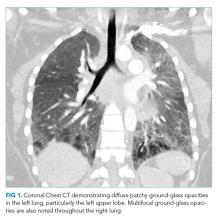

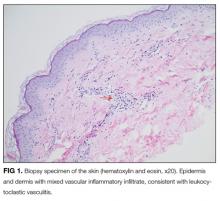

She had presented two months prior with nonproductive cough and dyspnea. At that presentation, her temperature was 36.3°C, heart rate 110 beats per minute, blood pressure 119/63 mm Hg, respiratory rate 43 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 86% while breathing ambient air. A chest CT with contrast demonstrated diffuse patchy multifocal ground-glass opacities in the bilateral lungs as well as a mixture of atelectasis and lobular emphysema in the dependent lobes bilaterally (Figure 1). Her main pulmonary artery was dilated at 3.6 cm (mean of 2.42 cm with SD 0.22). She was diagnosed with atypical pneumonia. She was administered azithromycin, weaned off oxygen, and discharged after a seven-day hospitalization.

Two months prior, she had marked tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxemia, and imaging revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities. The differential diagnosis for this constellation of symptoms is extensive and includes many conditions that have an inflammatory component, such as atypical pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma or Chlamydia pneumoniae or a common respiratory virus such as rhinovirus or human metapneumovirus. However, two findings make an acute pneumonia unlikely to be the sole cause of her symptoms: underlying emphysema and an enlarged pulmonary artery. Emphysema is an uncommon finding in children and can be related to congenital or acquired causes; congenital lobar emphysema most often presents earlier in life and is focal, not diffuse. Alpha-1-anti-trypin deficiency and mutations in connective tissue genes such as those encoding for elastin and fibrillin can lead to pulmonary disease. While not diagnostic of pulmonary hypertension, her dilated pulmonary artery, coupled with her history, makes pulmonary hypertension a strong possibility. While her pulmonary hypertension is most likely secondary to chronic lung disease based on the emphysematous changes on CT, it could still be related to a cardiac etiology.

The patient had a history of seasonal allergies and well-controlled asthma. She was hospitalized at age six for an asthma exacerbation associated with a respiratory infection. She was discharged with an albuterol inhaler, but seldom used it. Her parents denied any regular coughing during the day or night. She was morbidly obese. Her tonsils and adenoids were removed to treat obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) at age seven, and a subsequent polysomnography was normal. Her medications included intranasal fluticasone propionate and oral iron supplementation. She had no known allergies or recent travels. She had never smoked. She had two pet cats and a dog. Her mother had a history of obesity, OSA, and eczema. Her father had diabetes and eczema.

The patient’s history prior to the recent few months sheds little light on the cause of her current symptoms. While it is possible that her current symptoms are related to the worsening of a process that had been present for many years which mimicked asthma, this seems implausible given the long period of time between her last asthma exacerbation and her present symptoms. Similarly, while tonsillar and adenoidal hypertrophy can be associated with infiltrative diseases (such as lymphoma), this is less common than the usual (and normal) disproportionate increase in size of the adenoids compared to other airway structures during growth in children.

She was admitted to the hospital. On initial examination, her temperature was 37.4°C, heart rate 125 beats per minute, blood pressure 143/69 mm Hg, respiratory rate 48 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 86% breathing ambient air. Her BMI was 58 kg/m2. Her exam demonstrated increased work of breathing with accessory muscle use, and decreased breath sounds at the bases. There were no wheezes or crackles. Cardiovascular, abdominal, and skin exams were normal except for tachycardia. At rest, later in the hospitalization, her oxygen saturation was 97% breathing ambient air and heart rate 110 bpm. After two minutes of walking, her oxygen saturation was 77% and heart rate 132 bpm. Two minutes after resting, her oxygen saturation increased to 91%.

Her white blood cell count was 11.9 x 10 9 /L (67% neutrophils, 24.2% lymphocytes, 6% monocytes, and 2% eosinophils), hemoglobin 11.2 g/dL, and platelet count 278,000/mm 3 . Her complete metabolic panel was normal. The C-reactive protein (CRP) was 24 mg/L (normal range, < 4.9) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 103 mm/hour (normal range, 0-32). A venous blood gas (VBG) showed a pH of 7.42 and pCO2 39. An EKG demonstrated sinus tachycardia.

The combination of the patient’s tachypnea, hypoxemia, respiratory distress, and obesity is striking. Her lack of adventitious lung sounds is surprising given her CT findings, but the sensitivity of chest auscultation may be limited in obese patients. Her laboratory findings help narrow the diagnostic frame: she has mild anemia and leukocytosis along with significant inflammation. The normal CO2 concentration on VBG is concerning given the degree of her tachypnea and reflects significant alveolar hypoventilation.

This marked inflammation with diffuse lung findings again raises the possibility of an inflammatory or, less likely, infectious disorder. Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and juvenile dermatomyositis can present in young women with interstitial lung disease. She does have exposure to pets and hypersensitivity pneumonitis can worsen rapidly with continued exposure. Another possibility is that she has an underlying immunodeficiency such as common variable immunodeficiency, although a history of recurrent infections such as pneumonia, bacteremia, or sinusitis is lacking.

An echocardiogram should be performed. In addition, laboratory evaluation for the aforementioned autoimmune causes of interstitial lung disease, immunoglobulin levels, pulmonary function testing (if available as an inpatient), and potentially a bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and biopsy should be pursued. The BAL and biopsy would be helpful in evaluating for infection and interstitial lung disease in an expeditious manner.

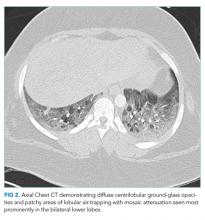

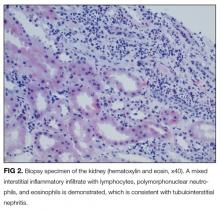

A chest CT without contrast was done and compared to the scan from two months prior. New diffuse, ill-defined centrilobular ground-glass opacities were evident throughout the lung fields; dilation of the main pulmonary artery was unchanged, and previously seen ground-glass opacities had resolved. There were patchy areas of air-trapping and mosaic attenuation in the lower lobes (Figure 2).

Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated a right ventricular systolic pressure of 58 mm Hg with flattened intraventricular septum during systole. Left and right ventricular systolic function were normal. The left ventricular diastolic function was normal. Pulmonary function testing demonstrated a FEV1/FVC ratio of 100 (112% predicted), FVC 1.07 L (35 % predicted) and FEV1 1.07 L (39% predicted), and total lung capacity was 2.7L (56% predicted) (Figure 3). Single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung was not interpretable based on 2017 European Respiratory Society (ERS)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) technical standards.

This information is helpful in classifying whether this patient’s primary condition is cardiac or pulmonary in nature. Her normal left ventricular systolic and diastolic function make a cardiac etiology for her pulmonary hypertension less likely. Further, the combination of pulmonary hypertension, a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing, and findings consistent with interstitial lung disease on cross-sectional imaging all suggest a primary pulmonary etiology rather than a cardiac, infectious, or thromboembolic condition. While chronic thromboembolic hypertension can result in nonspecific mosaic attenuation, it typically would not cause centrilobular ground-glass opacities nor restrictive lung disease. Thus, it seems most likely that this patient has a progressive pulmonary process resulting in hypoxia, pulmonary hypertension, centrilobular opacities, and lower-lobe mosaic attenuation. Considerations for this process can be broadly categorized as one of the childhood interstitial lung disease (chILD). While this differential diagnosis is broad, strong consideration should be given to hypersensitivity pneumonitis, chronic aspiration, sarcoidosis, and Sjogren’s syndrome. An intriguing possibility is that the patient’s “response to azithromycin” two months prior was due to the avoidance of an inhaled antigen while she was in the hospital; a detailed environmental history should be explored. The normal polysomnography after tonsilloadenoidectomy makes it unlikely that OSA is a major contributor to her current presentation. However, since the surgery was seven years ago, and her BMI is presently 58 kg/m2 she remains at risk for OSA and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome. Polysomnography should be done after her acute symptoms improve.

She was started on 5 mm Hg of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at night after a sleep study on room air demonstrated severe OSA with a respiratory disturbance index of 13 events per hour. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti-Jo-1 antibody, anti-RNP antibody, anti-Smith antibody, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibody were negative as was the histoplasmin antibody. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level was normal. Mycoplasma IgM and IgG were negative. IgE was 529 kU/L (normal range, <114).

This evaluation reduces the likelihood the patient has Sjogren’s syndrome, SLE, dermatomyositis, or ANCA-associated pulmonary disease. While many patients with dermatomyositis may have negative serologic evaluations, other findings usually present such as rash and myositis are lacking. The negative ANCA evaluation makes granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis very unlikely given the high sensitivity of the ANCA assay for these conditions. ANCA assays are less sensitive for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), but the lack of eosinophilia significantly decreases the likelihood of EGPA. ACE levels have relatively poor operating characteristics in the evaluation of sarcoidosis; however, sarcoidosis seems unlikely in this case, especially as patients with sarcoidosis tend to have low or normal IgE levels. Patients with asthma can have elevated IgE levels. However, very elevated IgE levels are more common in other conditions, including allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and the Hyper-IgE syndrome. The latter manifests with recurrent infections and eczema, and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. However, both the Hyper-IgE syndrome and ABPA have much higher IgE levels than seen in this case. Allergen-specific IgE testing (including for antibodies to Aspergillus) should be sent. It seems that an interstitial lung disease is present; the waxing and waning pattern and clinical presentation, along with the lack of other systemic findings, make hypersensitivity pneumonitis most likely.

The family lived in an apartment building. Her symptoms started when the family’s neighbor recently moved his outdoor pigeon coop into his basement. The patient often smelled the pigeons and noted feathers coming through the holes in the wall.

One of the key diagnostic features of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is the history of exposure to a potential offending antigen—in this case likely bird feathers—along with worsening upon reexposure to that antigen. HP is primarily a clinical diagnosis, and testing for serum precipitants has limited value, given the high false negative rate and the frequent lack of clinical symptoms accompanying positive testing. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid may reveal lymphocytosis and reduced CD4:CD8 ratio. Crackles are commonly heard on examination, but in this case were likely not auscultated due to her obese habitus. The most important treatment is withdrawal of the offending antigen. Limited data suggest that corticosteroid therapy may be helpful in certain HP cases, including subacute, chronic and severe cases as well as patients with hypoxemia, significant imaging findings, and those with significant abnormalities on pulmonary function testing (PFT).

A hypersensitivity pneumonitis precipitins panel was sent with positive antibodies to M. faeni, T. Vulgaris, A. Fumigatus 1 and 6, A. Flavus, and pigeon serum. Her symptoms gradually improved within five days of oral prednisone (60 mg). She was discharged home without dyspnea and normal oxygen saturation while breathing ambient air. A repeat echocardiogram after nighttime CPAP for 1 week demonstrated a right ventricular systolic pressure of 17 mm Hg consistent with improved pulmonary hypertension.

Three weeks later, she returned to clinic for follow up. She had re-experienced dyspnea, cough, and wheezing, which improved when she was outdoors. She was afebrile, tachypneic, tachycardic, and her oxygen saturation was 92% on ambient air.

Her steroid-responsive interstitial lung disease and rapid improvement upon avoidance of the offending antigen is consistent with HP. The positive serum precipitins assay lends further credence to the diagnosis of HP, although serologic analysis with such antibody assays is limited by false positives and false negatives; further, individuals exposed to pigeons often have antibodies present without evidence of HP. History taking at this visit should ask specifically about further pigeon exposure: were the pigeons removed from the home completely, were heating-cooling filters changed, carpets cleaned, and bedding laundered? An in-home evaluation may be helpful before conducting further diagnostic testing.

She was admitted for oxygen therapy and a bronchoscopy, which showed mucosal friability and cobblestoning, suggesting inflammation. BAL revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio of 3; BAL cultures were sterile. Her shortness of breath significantly improved following a prolonged course of systemic steroids and removal from the triggering environment. PFTs improved with a FEV1/FVC ratio of 94 (105% predicted), FVC of 2.00 L (66% predicted), FEV1 of 1.88L (69% predicted) (Figure 3B). Her presenting symptoms of persistent cough and progressive dyspnea on exertion, characteristic CT, sterile BAL cultures, positive serum precipitants against pigeon serum, and resolution of her symptoms with withdrawal of the offending antigen were diagnostic of hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to pigeon exposure, also known as bird fancier’s disease.

COMMENTARY

The patient’s original presentation of dyspnea, tachypnea, and hypoxia is commonly associated with pediatric pneumonia and asthma exacerbations.1 However, an alternative diagnosis was suggested by the lack of wheezing, absence of fever, and recurrent presentations with progressive symptoms.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) represents an exaggerated T-cell meditated immune response to inhalation of an offending antigen that results in a restrictive ventilatory defect and interstitial infiltrates.2 Bird pneumonitis (also known as bird fancier’s disease) is a frequent cause of HP, accounting for approximately 65-70% of cases.3 HP, however, only manifests in a small number of subjects exposed to culprit antigens, suggesting an underlying genetic susceptibility.4 Prevalence estimates vary depending on bird species, county, climate, and other possible factors.

There are no standard criteria for the diagnosis of HP, though a combination of findings is suggestive. A recent prospective multicenter study created a scoring system for HP based on factors associated with the disease to aid in accurate diagnosis. The most relevant criteria included antigen exposure, recurrent symptoms noted within 4-8 hours after antigen exposure, weight loss, presence of specific IgG antibodies to avian antigens, and inspiratory crackles on exam. Using this rule, the probability that our patient has HP based on clinical characteristics was 93% with an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.93 (96% confidence interval: 0.90-0.95)5. Chest imaging (high resolution CT) often consists of a mosaic pattern of air trapping, as seen in this patient in combination with ground-glass opacities6. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is sensitive in detecting lung inflammation in a patient with suspected HP. On BAL, a lymphocytic alveolitis can be seen, but absence of this finding does not exclude HP.5,7,8 Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) may be normal in acute HP. When abnormal, PFTs may reveal a restrictive pattern and reduction in carbon monoxide diffusing capacity.7 However, BAL and PFT results are neither specific nor diagnostic of HP; it is important to consider results in the context of the clinical picture.

The respiratory response to inhalation of the avian antigen has traditionally been classified as acute, subacute, or chronic.9 The acute response occurs within hours of exposure to the offending agent and usually resolves within 24 hours after antigen withdrawal. The subacute presentation involves cough and dyspnea over several days to weeks, and can progress to chronic and permanent lung damage if unrecognized and untreated. In chronic presentations, lung abnormalities may persist despite antigen avoidance and pharmacologic interventions.4,10 The patient’s symptoms occurred over a six-month period which coincided with pigeon exposure and resolved during each hospitalization with steroid treatment and removal from the offending agent. Her presentation was consistent with a subacute time course of HP.

The dilated pulmonary artery, elevated right systolic ventricular pressure, and normal right ventricular function in our patient suggested pulmonary hypertension of chronic duration. Her risk factors for pulmonary hypertension included asthma, sleep apnea, possible obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, and HP-associated interstitial lung disease.11

The most important intervention in HP is avoidance of the causative antigen. Medical therapy without removal of antigen is inadequate. Systemic corticosteroids can help ameliorate acute symptoms though dosing and duration remains unclear. For chronic patients unresponsive to steroid therapy, lung transplantation can be considered.4

The key to diagnosis of HP in this patient—and to minimizing repeat testing upon the patient’s recrudescence of symptoms—was the clinician’s consideration that the major impetus for the patient’s improvement in the hospital was removal from the offending antigen in her home environment. As in this case, taking time to delve deeply into a patient’s environment—even by descending the basement stairs—may lead to the diagnosis.

LEARNING POINTS

- Consider hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) in patients with recurrent respiratory distress, offending exposure, and resolution of symptoms with removal of culprit antigen.

- The most important treatment of HP is removal of offending antigen; systemic and/or inhaled corticosteroids are indicated until the full resolution of respiratory symptoms.

- Prognosis is dependent on early diagnosis and removal of offending exposures.

- Failure to treat HP might result in end-stage lung disease from pulmonary fibrosis secondary to long-term inflammation.

Disclosures

Dr. Manesh is supported by the Jeremiah A. Barondess Fellowship in the Clinical Transaction of the New York Academy of Medicine, in collaboration with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

1. Ebell MH. Clinical diagnosis of pneumonia in children. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(2):192-193. PubMed

2. Cormier Y, Lacasse Y. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis and organic dust toxic syndrome. In: Malo J-L, Chan-Yeung M, Bernstein DI, eds. Asthma in the Workplace. Vol 32. Boca Raton, FL: Fourth Informa Healthcare; 2013:392-405.

3. Chan AL, Juarez MM, Leslie KO, Ismail HA, Albertson TE. Bird fancier’s lung: a state-of-the-art review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;43(1-2):69-83. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8282-y. PubMed

4. Camarena A, Juárez A, Mejía M, et al. Major histocompatibility complex and tumor necrosis factor-α polymorphisms in pigeon breeder’s disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1528-1533. https:/doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2004023. PubMed

5. Lacasse Y, Selman M, Costabel U, et al. Clinical diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(8):952-958. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-137OC. PubMed

6. Glazer CS, Rose CS, Lynch DA. Clinical and radiologic manifestations of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J Thorac Imaging. 2002;17(4):261-272. PubMed

7. Selman M, Pardo A, King TE Jr. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(4):314-324. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0513CI. PubMed

8. Calillad DM, Vergnon, JM, Madroszyk A, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage in hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a series of 139 patients. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2012;11(1):15-19. doi: 10.2174/187152812798889330. PubMed

9. Richerson HB, Bernstein IL, Fink JN, et al. Guidelines for the clinical evaluation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Report of the Subcommittee on Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;84(5 Pt 2):839-844. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90349-7. PubMed

10. Zacharisen MC, Schlueter DP, Kurup VP, Fink JN. The long-term outcome in acute, subacute, and chronic forms of pigeon breeder’s disease hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88(2):175-182. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61993-X. PubMed

11. Raymond TE, Khabbaza JE, Yadav R, Tonelli AR. Significance of main pulmonary artery dilation on imaging studies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(10):1623-1632. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201406-253PP. PubMed

A 14-year-old girl with a history of asthma presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with three months of persistent, nonproductive cough, and progressive shortness of breath. She reported fatigue, chest tightness, orthopnea, and dyspnea with exertion. She denied fever, rhinorrhea, congestion, hemoptysis, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

Her age and past medical history of asthma are incongruent with her new symptoms, as asthma is typified by intermittent exacerbations, not progressive symptoms. Thus, another process, in addition to asthma, is most likely present; it is also important to question the accuracy of previous diagnoses in light of new information. Her symptoms may signify an underlying cardiopulmonary process, such as infiltrative diseases (eg, lymphoma or sarcoidosis), atypical infections, genetic conditions (eg, variant cystic fibrosis), autoimmune conditions, or cardiomyopathy. A detailed symptom history, family history, and careful physical examination will help expand and then refine the differential diagnosis. At this stage, typical infections are less likely.

She had presented two months prior with nonproductive cough and dyspnea. At that presentation, her temperature was 36.3°C, heart rate 110 beats per minute, blood pressure 119/63 mm Hg, respiratory rate 43 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 86% while breathing ambient air. A chest CT with contrast demonstrated diffuse patchy multifocal ground-glass opacities in the bilateral lungs as well as a mixture of atelectasis and lobular emphysema in the dependent lobes bilaterally (Figure 1). Her main pulmonary artery was dilated at 3.6 cm (mean of 2.42 cm with SD 0.22). She was diagnosed with atypical pneumonia. She was administered azithromycin, weaned off oxygen, and discharged after a seven-day hospitalization.

Two months prior, she had marked tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxemia, and imaging revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities. The differential diagnosis for this constellation of symptoms is extensive and includes many conditions that have an inflammatory component, such as atypical pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma or Chlamydia pneumoniae or a common respiratory virus such as rhinovirus or human metapneumovirus. However, two findings make an acute pneumonia unlikely to be the sole cause of her symptoms: underlying emphysema and an enlarged pulmonary artery. Emphysema is an uncommon finding in children and can be related to congenital or acquired causes; congenital lobar emphysema most often presents earlier in life and is focal, not diffuse. Alpha-1-anti-trypin deficiency and mutations in connective tissue genes such as those encoding for elastin and fibrillin can lead to pulmonary disease. While not diagnostic of pulmonary hypertension, her dilated pulmonary artery, coupled with her history, makes pulmonary hypertension a strong possibility. While her pulmonary hypertension is most likely secondary to chronic lung disease based on the emphysematous changes on CT, it could still be related to a cardiac etiology.

The patient had a history of seasonal allergies and well-controlled asthma. She was hospitalized at age six for an asthma exacerbation associated with a respiratory infection. She was discharged with an albuterol inhaler, but seldom used it. Her parents denied any regular coughing during the day or night. She was morbidly obese. Her tonsils and adenoids were removed to treat obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) at age seven, and a subsequent polysomnography was normal. Her medications included intranasal fluticasone propionate and oral iron supplementation. She had no known allergies or recent travels. She had never smoked. She had two pet cats and a dog. Her mother had a history of obesity, OSA, and eczema. Her father had diabetes and eczema.

The patient’s history prior to the recent few months sheds little light on the cause of her current symptoms. While it is possible that her current symptoms are related to the worsening of a process that had been present for many years which mimicked asthma, this seems implausible given the long period of time between her last asthma exacerbation and her present symptoms. Similarly, while tonsillar and adenoidal hypertrophy can be associated with infiltrative diseases (such as lymphoma), this is less common than the usual (and normal) disproportionate increase in size of the adenoids compared to other airway structures during growth in children.

She was admitted to the hospital. On initial examination, her temperature was 37.4°C, heart rate 125 beats per minute, blood pressure 143/69 mm Hg, respiratory rate 48 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 86% breathing ambient air. Her BMI was 58 kg/m2. Her exam demonstrated increased work of breathing with accessory muscle use, and decreased breath sounds at the bases. There were no wheezes or crackles. Cardiovascular, abdominal, and skin exams were normal except for tachycardia. At rest, later in the hospitalization, her oxygen saturation was 97% breathing ambient air and heart rate 110 bpm. After two minutes of walking, her oxygen saturation was 77% and heart rate 132 bpm. Two minutes after resting, her oxygen saturation increased to 91%.

Her white blood cell count was 11.9 x 10 9 /L (67% neutrophils, 24.2% lymphocytes, 6% monocytes, and 2% eosinophils), hemoglobin 11.2 g/dL, and platelet count 278,000/mm 3 . Her complete metabolic panel was normal. The C-reactive protein (CRP) was 24 mg/L (normal range, < 4.9) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 103 mm/hour (normal range, 0-32). A venous blood gas (VBG) showed a pH of 7.42 and pCO2 39. An EKG demonstrated sinus tachycardia.

The combination of the patient’s tachypnea, hypoxemia, respiratory distress, and obesity is striking. Her lack of adventitious lung sounds is surprising given her CT findings, but the sensitivity of chest auscultation may be limited in obese patients. Her laboratory findings help narrow the diagnostic frame: she has mild anemia and leukocytosis along with significant inflammation. The normal CO2 concentration on VBG is concerning given the degree of her tachypnea and reflects significant alveolar hypoventilation.

This marked inflammation with diffuse lung findings again raises the possibility of an inflammatory or, less likely, infectious disorder. Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and juvenile dermatomyositis can present in young women with interstitial lung disease. She does have exposure to pets and hypersensitivity pneumonitis can worsen rapidly with continued exposure. Another possibility is that she has an underlying immunodeficiency such as common variable immunodeficiency, although a history of recurrent infections such as pneumonia, bacteremia, or sinusitis is lacking.

An echocardiogram should be performed. In addition, laboratory evaluation for the aforementioned autoimmune causes of interstitial lung disease, immunoglobulin levels, pulmonary function testing (if available as an inpatient), and potentially a bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and biopsy should be pursued. The BAL and biopsy would be helpful in evaluating for infection and interstitial lung disease in an expeditious manner.

A chest CT without contrast was done and compared to the scan from two months prior. New diffuse, ill-defined centrilobular ground-glass opacities were evident throughout the lung fields; dilation of the main pulmonary artery was unchanged, and previously seen ground-glass opacities had resolved. There were patchy areas of air-trapping and mosaic attenuation in the lower lobes (Figure 2).

Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated a right ventricular systolic pressure of 58 mm Hg with flattened intraventricular septum during systole. Left and right ventricular systolic function were normal. The left ventricular diastolic function was normal. Pulmonary function testing demonstrated a FEV1/FVC ratio of 100 (112% predicted), FVC 1.07 L (35 % predicted) and FEV1 1.07 L (39% predicted), and total lung capacity was 2.7L (56% predicted) (Figure 3). Single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung was not interpretable based on 2017 European Respiratory Society (ERS)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) technical standards.

This information is helpful in classifying whether this patient’s primary condition is cardiac or pulmonary in nature. Her normal left ventricular systolic and diastolic function make a cardiac etiology for her pulmonary hypertension less likely. Further, the combination of pulmonary hypertension, a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing, and findings consistent with interstitial lung disease on cross-sectional imaging all suggest a primary pulmonary etiology rather than a cardiac, infectious, or thromboembolic condition. While chronic thromboembolic hypertension can result in nonspecific mosaic attenuation, it typically would not cause centrilobular ground-glass opacities nor restrictive lung disease. Thus, it seems most likely that this patient has a progressive pulmonary process resulting in hypoxia, pulmonary hypertension, centrilobular opacities, and lower-lobe mosaic attenuation. Considerations for this process can be broadly categorized as one of the childhood interstitial lung disease (chILD). While this differential diagnosis is broad, strong consideration should be given to hypersensitivity pneumonitis, chronic aspiration, sarcoidosis, and Sjogren’s syndrome. An intriguing possibility is that the patient’s “response to azithromycin” two months prior was due to the avoidance of an inhaled antigen while she was in the hospital; a detailed environmental history should be explored. The normal polysomnography after tonsilloadenoidectomy makes it unlikely that OSA is a major contributor to her current presentation. However, since the surgery was seven years ago, and her BMI is presently 58 kg/m2 she remains at risk for OSA and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome. Polysomnography should be done after her acute symptoms improve.

She was started on 5 mm Hg of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at night after a sleep study on room air demonstrated severe OSA with a respiratory disturbance index of 13 events per hour. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti-Jo-1 antibody, anti-RNP antibody, anti-Smith antibody, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibody were negative as was the histoplasmin antibody. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level was normal. Mycoplasma IgM and IgG were negative. IgE was 529 kU/L (normal range, <114).

This evaluation reduces the likelihood the patient has Sjogren’s syndrome, SLE, dermatomyositis, or ANCA-associated pulmonary disease. While many patients with dermatomyositis may have negative serologic evaluations, other findings usually present such as rash and myositis are lacking. The negative ANCA evaluation makes granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis very unlikely given the high sensitivity of the ANCA assay for these conditions. ANCA assays are less sensitive for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), but the lack of eosinophilia significantly decreases the likelihood of EGPA. ACE levels have relatively poor operating characteristics in the evaluation of sarcoidosis; however, sarcoidosis seems unlikely in this case, especially as patients with sarcoidosis tend to have low or normal IgE levels. Patients with asthma can have elevated IgE levels. However, very elevated IgE levels are more common in other conditions, including allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and the Hyper-IgE syndrome. The latter manifests with recurrent infections and eczema, and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. However, both the Hyper-IgE syndrome and ABPA have much higher IgE levels than seen in this case. Allergen-specific IgE testing (including for antibodies to Aspergillus) should be sent. It seems that an interstitial lung disease is present; the waxing and waning pattern and clinical presentation, along with the lack of other systemic findings, make hypersensitivity pneumonitis most likely.

The family lived in an apartment building. Her symptoms started when the family’s neighbor recently moved his outdoor pigeon coop into his basement. The patient often smelled the pigeons and noted feathers coming through the holes in the wall.

One of the key diagnostic features of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is the history of exposure to a potential offending antigen—in this case likely bird feathers—along with worsening upon reexposure to that antigen. HP is primarily a clinical diagnosis, and testing for serum precipitants has limited value, given the high false negative rate and the frequent lack of clinical symptoms accompanying positive testing. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid may reveal lymphocytosis and reduced CD4:CD8 ratio. Crackles are commonly heard on examination, but in this case were likely not auscultated due to her obese habitus. The most important treatment is withdrawal of the offending antigen. Limited data suggest that corticosteroid therapy may be helpful in certain HP cases, including subacute, chronic and severe cases as well as patients with hypoxemia, significant imaging findings, and those with significant abnormalities on pulmonary function testing (PFT).

A hypersensitivity pneumonitis precipitins panel was sent with positive antibodies to M. faeni, T. Vulgaris, A. Fumigatus 1 and 6, A. Flavus, and pigeon serum. Her symptoms gradually improved within five days of oral prednisone (60 mg). She was discharged home without dyspnea and normal oxygen saturation while breathing ambient air. A repeat echocardiogram after nighttime CPAP for 1 week demonstrated a right ventricular systolic pressure of 17 mm Hg consistent with improved pulmonary hypertension.

Three weeks later, she returned to clinic for follow up. She had re-experienced dyspnea, cough, and wheezing, which improved when she was outdoors. She was afebrile, tachypneic, tachycardic, and her oxygen saturation was 92% on ambient air.

Her steroid-responsive interstitial lung disease and rapid improvement upon avoidance of the offending antigen is consistent with HP. The positive serum precipitins assay lends further credence to the diagnosis of HP, although serologic analysis with such antibody assays is limited by false positives and false negatives; further, individuals exposed to pigeons often have antibodies present without evidence of HP. History taking at this visit should ask specifically about further pigeon exposure: were the pigeons removed from the home completely, were heating-cooling filters changed, carpets cleaned, and bedding laundered? An in-home evaluation may be helpful before conducting further diagnostic testing.

She was admitted for oxygen therapy and a bronchoscopy, which showed mucosal friability and cobblestoning, suggesting inflammation. BAL revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio of 3; BAL cultures were sterile. Her shortness of breath significantly improved following a prolonged course of systemic steroids and removal from the triggering environment. PFTs improved with a FEV1/FVC ratio of 94 (105% predicted), FVC of 2.00 L (66% predicted), FEV1 of 1.88L (69% predicted) (Figure 3B). Her presenting symptoms of persistent cough and progressive dyspnea on exertion, characteristic CT, sterile BAL cultures, positive serum precipitants against pigeon serum, and resolution of her symptoms with withdrawal of the offending antigen were diagnostic of hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to pigeon exposure, also known as bird fancier’s disease.

COMMENTARY

The patient’s original presentation of dyspnea, tachypnea, and hypoxia is commonly associated with pediatric pneumonia and asthma exacerbations.1 However, an alternative diagnosis was suggested by the lack of wheezing, absence of fever, and recurrent presentations with progressive symptoms.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) represents an exaggerated T-cell meditated immune response to inhalation of an offending antigen that results in a restrictive ventilatory defect and interstitial infiltrates.2 Bird pneumonitis (also known as bird fancier’s disease) is a frequent cause of HP, accounting for approximately 65-70% of cases.3 HP, however, only manifests in a small number of subjects exposed to culprit antigens, suggesting an underlying genetic susceptibility.4 Prevalence estimates vary depending on bird species, county, climate, and other possible factors.

There are no standard criteria for the diagnosis of HP, though a combination of findings is suggestive. A recent prospective multicenter study created a scoring system for HP based on factors associated with the disease to aid in accurate diagnosis. The most relevant criteria included antigen exposure, recurrent symptoms noted within 4-8 hours after antigen exposure, weight loss, presence of specific IgG antibodies to avian antigens, and inspiratory crackles on exam. Using this rule, the probability that our patient has HP based on clinical characteristics was 93% with an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.93 (96% confidence interval: 0.90-0.95)5. Chest imaging (high resolution CT) often consists of a mosaic pattern of air trapping, as seen in this patient in combination with ground-glass opacities6. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is sensitive in detecting lung inflammation in a patient with suspected HP. On BAL, a lymphocytic alveolitis can be seen, but absence of this finding does not exclude HP.5,7,8 Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) may be normal in acute HP. When abnormal, PFTs may reveal a restrictive pattern and reduction in carbon monoxide diffusing capacity.7 However, BAL and PFT results are neither specific nor diagnostic of HP; it is important to consider results in the context of the clinical picture.

The respiratory response to inhalation of the avian antigen has traditionally been classified as acute, subacute, or chronic.9 The acute response occurs within hours of exposure to the offending agent and usually resolves within 24 hours after antigen withdrawal. The subacute presentation involves cough and dyspnea over several days to weeks, and can progress to chronic and permanent lung damage if unrecognized and untreated. In chronic presentations, lung abnormalities may persist despite antigen avoidance and pharmacologic interventions.4,10 The patient’s symptoms occurred over a six-month period which coincided with pigeon exposure and resolved during each hospitalization with steroid treatment and removal from the offending agent. Her presentation was consistent with a subacute time course of HP.

The dilated pulmonary artery, elevated right systolic ventricular pressure, and normal right ventricular function in our patient suggested pulmonary hypertension of chronic duration. Her risk factors for pulmonary hypertension included asthma, sleep apnea, possible obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, and HP-associated interstitial lung disease.11

The most important intervention in HP is avoidance of the causative antigen. Medical therapy without removal of antigen is inadequate. Systemic corticosteroids can help ameliorate acute symptoms though dosing and duration remains unclear. For chronic patients unresponsive to steroid therapy, lung transplantation can be considered.4

The key to diagnosis of HP in this patient—and to minimizing repeat testing upon the patient’s recrudescence of symptoms—was the clinician’s consideration that the major impetus for the patient’s improvement in the hospital was removal from the offending antigen in her home environment. As in this case, taking time to delve deeply into a patient’s environment—even by descending the basement stairs—may lead to the diagnosis.

LEARNING POINTS

- Consider hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) in patients with recurrent respiratory distress, offending exposure, and resolution of symptoms with removal of culprit antigen.

- The most important treatment of HP is removal of offending antigen; systemic and/or inhaled corticosteroids are indicated until the full resolution of respiratory symptoms.

- Prognosis is dependent on early diagnosis and removal of offending exposures.

- Failure to treat HP might result in end-stage lung disease from pulmonary fibrosis secondary to long-term inflammation.

Disclosures

Dr. Manesh is supported by the Jeremiah A. Barondess Fellowship in the Clinical Transaction of the New York Academy of Medicine, in collaboration with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

A 14-year-old girl with a history of asthma presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with three months of persistent, nonproductive cough, and progressive shortness of breath. She reported fatigue, chest tightness, orthopnea, and dyspnea with exertion. She denied fever, rhinorrhea, congestion, hemoptysis, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

Her age and past medical history of asthma are incongruent with her new symptoms, as asthma is typified by intermittent exacerbations, not progressive symptoms. Thus, another process, in addition to asthma, is most likely present; it is also important to question the accuracy of previous diagnoses in light of new information. Her symptoms may signify an underlying cardiopulmonary process, such as infiltrative diseases (eg, lymphoma or sarcoidosis), atypical infections, genetic conditions (eg, variant cystic fibrosis), autoimmune conditions, or cardiomyopathy. A detailed symptom history, family history, and careful physical examination will help expand and then refine the differential diagnosis. At this stage, typical infections are less likely.

She had presented two months prior with nonproductive cough and dyspnea. At that presentation, her temperature was 36.3°C, heart rate 110 beats per minute, blood pressure 119/63 mm Hg, respiratory rate 43 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 86% while breathing ambient air. A chest CT with contrast demonstrated diffuse patchy multifocal ground-glass opacities in the bilateral lungs as well as a mixture of atelectasis and lobular emphysema in the dependent lobes bilaterally (Figure 1). Her main pulmonary artery was dilated at 3.6 cm (mean of 2.42 cm with SD 0.22). She was diagnosed with atypical pneumonia. She was administered azithromycin, weaned off oxygen, and discharged after a seven-day hospitalization.

Two months prior, she had marked tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxemia, and imaging revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities. The differential diagnosis for this constellation of symptoms is extensive and includes many conditions that have an inflammatory component, such as atypical pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma or Chlamydia pneumoniae or a common respiratory virus such as rhinovirus or human metapneumovirus. However, two findings make an acute pneumonia unlikely to be the sole cause of her symptoms: underlying emphysema and an enlarged pulmonary artery. Emphysema is an uncommon finding in children and can be related to congenital or acquired causes; congenital lobar emphysema most often presents earlier in life and is focal, not diffuse. Alpha-1-anti-trypin deficiency and mutations in connective tissue genes such as those encoding for elastin and fibrillin can lead to pulmonary disease. While not diagnostic of pulmonary hypertension, her dilated pulmonary artery, coupled with her history, makes pulmonary hypertension a strong possibility. While her pulmonary hypertension is most likely secondary to chronic lung disease based on the emphysematous changes on CT, it could still be related to a cardiac etiology.

The patient had a history of seasonal allergies and well-controlled asthma. She was hospitalized at age six for an asthma exacerbation associated with a respiratory infection. She was discharged with an albuterol inhaler, but seldom used it. Her parents denied any regular coughing during the day or night. She was morbidly obese. Her tonsils and adenoids were removed to treat obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) at age seven, and a subsequent polysomnography was normal. Her medications included intranasal fluticasone propionate and oral iron supplementation. She had no known allergies or recent travels. She had never smoked. She had two pet cats and a dog. Her mother had a history of obesity, OSA, and eczema. Her father had diabetes and eczema.

The patient’s history prior to the recent few months sheds little light on the cause of her current symptoms. While it is possible that her current symptoms are related to the worsening of a process that had been present for many years which mimicked asthma, this seems implausible given the long period of time between her last asthma exacerbation and her present symptoms. Similarly, while tonsillar and adenoidal hypertrophy can be associated with infiltrative diseases (such as lymphoma), this is less common than the usual (and normal) disproportionate increase in size of the adenoids compared to other airway structures during growth in children.

She was admitted to the hospital. On initial examination, her temperature was 37.4°C, heart rate 125 beats per minute, blood pressure 143/69 mm Hg, respiratory rate 48 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 86% breathing ambient air. Her BMI was 58 kg/m2. Her exam demonstrated increased work of breathing with accessory muscle use, and decreased breath sounds at the bases. There were no wheezes or crackles. Cardiovascular, abdominal, and skin exams were normal except for tachycardia. At rest, later in the hospitalization, her oxygen saturation was 97% breathing ambient air and heart rate 110 bpm. After two minutes of walking, her oxygen saturation was 77% and heart rate 132 bpm. Two minutes after resting, her oxygen saturation increased to 91%.

Her white blood cell count was 11.9 x 10 9 /L (67% neutrophils, 24.2% lymphocytes, 6% monocytes, and 2% eosinophils), hemoglobin 11.2 g/dL, and platelet count 278,000/mm 3 . Her complete metabolic panel was normal. The C-reactive protein (CRP) was 24 mg/L (normal range, < 4.9) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 103 mm/hour (normal range, 0-32). A venous blood gas (VBG) showed a pH of 7.42 and pCO2 39. An EKG demonstrated sinus tachycardia.

The combination of the patient’s tachypnea, hypoxemia, respiratory distress, and obesity is striking. Her lack of adventitious lung sounds is surprising given her CT findings, but the sensitivity of chest auscultation may be limited in obese patients. Her laboratory findings help narrow the diagnostic frame: she has mild anemia and leukocytosis along with significant inflammation. The normal CO2 concentration on VBG is concerning given the degree of her tachypnea and reflects significant alveolar hypoventilation.

This marked inflammation with diffuse lung findings again raises the possibility of an inflammatory or, less likely, infectious disorder. Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and juvenile dermatomyositis can present in young women with interstitial lung disease. She does have exposure to pets and hypersensitivity pneumonitis can worsen rapidly with continued exposure. Another possibility is that she has an underlying immunodeficiency such as common variable immunodeficiency, although a history of recurrent infections such as pneumonia, bacteremia, or sinusitis is lacking.

An echocardiogram should be performed. In addition, laboratory evaluation for the aforementioned autoimmune causes of interstitial lung disease, immunoglobulin levels, pulmonary function testing (if available as an inpatient), and potentially a bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and biopsy should be pursued. The BAL and biopsy would be helpful in evaluating for infection and interstitial lung disease in an expeditious manner.

A chest CT without contrast was done and compared to the scan from two months prior. New diffuse, ill-defined centrilobular ground-glass opacities were evident throughout the lung fields; dilation of the main pulmonary artery was unchanged, and previously seen ground-glass opacities had resolved. There were patchy areas of air-trapping and mosaic attenuation in the lower lobes (Figure 2).

Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated a right ventricular systolic pressure of 58 mm Hg with flattened intraventricular septum during systole. Left and right ventricular systolic function were normal. The left ventricular diastolic function was normal. Pulmonary function testing demonstrated a FEV1/FVC ratio of 100 (112% predicted), FVC 1.07 L (35 % predicted) and FEV1 1.07 L (39% predicted), and total lung capacity was 2.7L (56% predicted) (Figure 3). Single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung was not interpretable based on 2017 European Respiratory Society (ERS)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) technical standards.

This information is helpful in classifying whether this patient’s primary condition is cardiac or pulmonary in nature. Her normal left ventricular systolic and diastolic function make a cardiac etiology for her pulmonary hypertension less likely. Further, the combination of pulmonary hypertension, a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing, and findings consistent with interstitial lung disease on cross-sectional imaging all suggest a primary pulmonary etiology rather than a cardiac, infectious, or thromboembolic condition. While chronic thromboembolic hypertension can result in nonspecific mosaic attenuation, it typically would not cause centrilobular ground-glass opacities nor restrictive lung disease. Thus, it seems most likely that this patient has a progressive pulmonary process resulting in hypoxia, pulmonary hypertension, centrilobular opacities, and lower-lobe mosaic attenuation. Considerations for this process can be broadly categorized as one of the childhood interstitial lung disease (chILD). While this differential diagnosis is broad, strong consideration should be given to hypersensitivity pneumonitis, chronic aspiration, sarcoidosis, and Sjogren’s syndrome. An intriguing possibility is that the patient’s “response to azithromycin” two months prior was due to the avoidance of an inhaled antigen while she was in the hospital; a detailed environmental history should be explored. The normal polysomnography after tonsilloadenoidectomy makes it unlikely that OSA is a major contributor to her current presentation. However, since the surgery was seven years ago, and her BMI is presently 58 kg/m2 she remains at risk for OSA and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome. Polysomnography should be done after her acute symptoms improve.

She was started on 5 mm Hg of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at night after a sleep study on room air demonstrated severe OSA with a respiratory disturbance index of 13 events per hour. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti-Jo-1 antibody, anti-RNP antibody, anti-Smith antibody, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibody were negative as was the histoplasmin antibody. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level was normal. Mycoplasma IgM and IgG were negative. IgE was 529 kU/L (normal range, <114).

This evaluation reduces the likelihood the patient has Sjogren’s syndrome, SLE, dermatomyositis, or ANCA-associated pulmonary disease. While many patients with dermatomyositis may have negative serologic evaluations, other findings usually present such as rash and myositis are lacking. The negative ANCA evaluation makes granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis very unlikely given the high sensitivity of the ANCA assay for these conditions. ANCA assays are less sensitive for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), but the lack of eosinophilia significantly decreases the likelihood of EGPA. ACE levels have relatively poor operating characteristics in the evaluation of sarcoidosis; however, sarcoidosis seems unlikely in this case, especially as patients with sarcoidosis tend to have low or normal IgE levels. Patients with asthma can have elevated IgE levels. However, very elevated IgE levels are more common in other conditions, including allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and the Hyper-IgE syndrome. The latter manifests with recurrent infections and eczema, and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. However, both the Hyper-IgE syndrome and ABPA have much higher IgE levels than seen in this case. Allergen-specific IgE testing (including for antibodies to Aspergillus) should be sent. It seems that an interstitial lung disease is present; the waxing and waning pattern and clinical presentation, along with the lack of other systemic findings, make hypersensitivity pneumonitis most likely.

The family lived in an apartment building. Her symptoms started when the family’s neighbor recently moved his outdoor pigeon coop into his basement. The patient often smelled the pigeons and noted feathers coming through the holes in the wall.

One of the key diagnostic features of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is the history of exposure to a potential offending antigen—in this case likely bird feathers—along with worsening upon reexposure to that antigen. HP is primarily a clinical diagnosis, and testing for serum precipitants has limited value, given the high false negative rate and the frequent lack of clinical symptoms accompanying positive testing. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid may reveal lymphocytosis and reduced CD4:CD8 ratio. Crackles are commonly heard on examination, but in this case were likely not auscultated due to her obese habitus. The most important treatment is withdrawal of the offending antigen. Limited data suggest that corticosteroid therapy may be helpful in certain HP cases, including subacute, chronic and severe cases as well as patients with hypoxemia, significant imaging findings, and those with significant abnormalities on pulmonary function testing (PFT).

A hypersensitivity pneumonitis precipitins panel was sent with positive antibodies to M. faeni, T. Vulgaris, A. Fumigatus 1 and 6, A. Flavus, and pigeon serum. Her symptoms gradually improved within five days of oral prednisone (60 mg). She was discharged home without dyspnea and normal oxygen saturation while breathing ambient air. A repeat echocardiogram after nighttime CPAP for 1 week demonstrated a right ventricular systolic pressure of 17 mm Hg consistent with improved pulmonary hypertension.

Three weeks later, she returned to clinic for follow up. She had re-experienced dyspnea, cough, and wheezing, which improved when she was outdoors. She was afebrile, tachypneic, tachycardic, and her oxygen saturation was 92% on ambient air.

Her steroid-responsive interstitial lung disease and rapid improvement upon avoidance of the offending antigen is consistent with HP. The positive serum precipitins assay lends further credence to the diagnosis of HP, although serologic analysis with such antibody assays is limited by false positives and false negatives; further, individuals exposed to pigeons often have antibodies present without evidence of HP. History taking at this visit should ask specifically about further pigeon exposure: were the pigeons removed from the home completely, were heating-cooling filters changed, carpets cleaned, and bedding laundered? An in-home evaluation may be helpful before conducting further diagnostic testing.

She was admitted for oxygen therapy and a bronchoscopy, which showed mucosal friability and cobblestoning, suggesting inflammation. BAL revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio of 3; BAL cultures were sterile. Her shortness of breath significantly improved following a prolonged course of systemic steroids and removal from the triggering environment. PFTs improved with a FEV1/FVC ratio of 94 (105% predicted), FVC of 2.00 L (66% predicted), FEV1 of 1.88L (69% predicted) (Figure 3B). Her presenting symptoms of persistent cough and progressive dyspnea on exertion, characteristic CT, sterile BAL cultures, positive serum precipitants against pigeon serum, and resolution of her symptoms with withdrawal of the offending antigen were diagnostic of hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to pigeon exposure, also known as bird fancier’s disease.

COMMENTARY

The patient’s original presentation of dyspnea, tachypnea, and hypoxia is commonly associated with pediatric pneumonia and asthma exacerbations.1 However, an alternative diagnosis was suggested by the lack of wheezing, absence of fever, and recurrent presentations with progressive symptoms.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) represents an exaggerated T-cell meditated immune response to inhalation of an offending antigen that results in a restrictive ventilatory defect and interstitial infiltrates.2 Bird pneumonitis (also known as bird fancier’s disease) is a frequent cause of HP, accounting for approximately 65-70% of cases.3 HP, however, only manifests in a small number of subjects exposed to culprit antigens, suggesting an underlying genetic susceptibility.4 Prevalence estimates vary depending on bird species, county, climate, and other possible factors.

There are no standard criteria for the diagnosis of HP, though a combination of findings is suggestive. A recent prospective multicenter study created a scoring system for HP based on factors associated with the disease to aid in accurate diagnosis. The most relevant criteria included antigen exposure, recurrent symptoms noted within 4-8 hours after antigen exposure, weight loss, presence of specific IgG antibodies to avian antigens, and inspiratory crackles on exam. Using this rule, the probability that our patient has HP based on clinical characteristics was 93% with an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.93 (96% confidence interval: 0.90-0.95)5. Chest imaging (high resolution CT) often consists of a mosaic pattern of air trapping, as seen in this patient in combination with ground-glass opacities6. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is sensitive in detecting lung inflammation in a patient with suspected HP. On BAL, a lymphocytic alveolitis can be seen, but absence of this finding does not exclude HP.5,7,8 Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) may be normal in acute HP. When abnormal, PFTs may reveal a restrictive pattern and reduction in carbon monoxide diffusing capacity.7 However, BAL and PFT results are neither specific nor diagnostic of HP; it is important to consider results in the context of the clinical picture.

The respiratory response to inhalation of the avian antigen has traditionally been classified as acute, subacute, or chronic.9 The acute response occurs within hours of exposure to the offending agent and usually resolves within 24 hours after antigen withdrawal. The subacute presentation involves cough and dyspnea over several days to weeks, and can progress to chronic and permanent lung damage if unrecognized and untreated. In chronic presentations, lung abnormalities may persist despite antigen avoidance and pharmacologic interventions.4,10 The patient’s symptoms occurred over a six-month period which coincided with pigeon exposure and resolved during each hospitalization with steroid treatment and removal from the offending agent. Her presentation was consistent with a subacute time course of HP.

The dilated pulmonary artery, elevated right systolic ventricular pressure, and normal right ventricular function in our patient suggested pulmonary hypertension of chronic duration. Her risk factors for pulmonary hypertension included asthma, sleep apnea, possible obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, and HP-associated interstitial lung disease.11

The most important intervention in HP is avoidance of the causative antigen. Medical therapy without removal of antigen is inadequate. Systemic corticosteroids can help ameliorate acute symptoms though dosing and duration remains unclear. For chronic patients unresponsive to steroid therapy, lung transplantation can be considered.4

The key to diagnosis of HP in this patient—and to minimizing repeat testing upon the patient’s recrudescence of symptoms—was the clinician’s consideration that the major impetus for the patient’s improvement in the hospital was removal from the offending antigen in her home environment. As in this case, taking time to delve deeply into a patient’s environment—even by descending the basement stairs—may lead to the diagnosis.

LEARNING POINTS

- Consider hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) in patients with recurrent respiratory distress, offending exposure, and resolution of symptoms with removal of culprit antigen.

- The most important treatment of HP is removal of offending antigen; systemic and/or inhaled corticosteroids are indicated until the full resolution of respiratory symptoms.

- Prognosis is dependent on early diagnosis and removal of offending exposures.

- Failure to treat HP might result in end-stage lung disease from pulmonary fibrosis secondary to long-term inflammation.

Disclosures

Dr. Manesh is supported by the Jeremiah A. Barondess Fellowship in the Clinical Transaction of the New York Academy of Medicine, in collaboration with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

1. Ebell MH. Clinical diagnosis of pneumonia in children. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(2):192-193. PubMed

2. Cormier Y, Lacasse Y. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis and organic dust toxic syndrome. In: Malo J-L, Chan-Yeung M, Bernstein DI, eds. Asthma in the Workplace. Vol 32. Boca Raton, FL: Fourth Informa Healthcare; 2013:392-405.

3. Chan AL, Juarez MM, Leslie KO, Ismail HA, Albertson TE. Bird fancier’s lung: a state-of-the-art review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;43(1-2):69-83. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8282-y. PubMed

4. Camarena A, Juárez A, Mejía M, et al. Major histocompatibility complex and tumor necrosis factor-α polymorphisms in pigeon breeder’s disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1528-1533. https:/doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2004023. PubMed

5. Lacasse Y, Selman M, Costabel U, et al. Clinical diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(8):952-958. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-137OC. PubMed

6. Glazer CS, Rose CS, Lynch DA. Clinical and radiologic manifestations of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J Thorac Imaging. 2002;17(4):261-272. PubMed

7. Selman M, Pardo A, King TE Jr. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(4):314-324. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0513CI. PubMed

8. Calillad DM, Vergnon, JM, Madroszyk A, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage in hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a series of 139 patients. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2012;11(1):15-19. doi: 10.2174/187152812798889330. PubMed

9. Richerson HB, Bernstein IL, Fink JN, et al. Guidelines for the clinical evaluation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Report of the Subcommittee on Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;84(5 Pt 2):839-844. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90349-7. PubMed

10. Zacharisen MC, Schlueter DP, Kurup VP, Fink JN. The long-term outcome in acute, subacute, and chronic forms of pigeon breeder’s disease hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88(2):175-182. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61993-X. PubMed

11. Raymond TE, Khabbaza JE, Yadav R, Tonelli AR. Significance of main pulmonary artery dilation on imaging studies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(10):1623-1632. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201406-253PP. PubMed

1. Ebell MH. Clinical diagnosis of pneumonia in children. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(2):192-193. PubMed

2. Cormier Y, Lacasse Y. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis and organic dust toxic syndrome. In: Malo J-L, Chan-Yeung M, Bernstein DI, eds. Asthma in the Workplace. Vol 32. Boca Raton, FL: Fourth Informa Healthcare; 2013:392-405.

3. Chan AL, Juarez MM, Leslie KO, Ismail HA, Albertson TE. Bird fancier’s lung: a state-of-the-art review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;43(1-2):69-83. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8282-y. PubMed

4. Camarena A, Juárez A, Mejía M, et al. Major histocompatibility complex and tumor necrosis factor-α polymorphisms in pigeon breeder’s disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1528-1533. https:/doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2004023. PubMed

5. Lacasse Y, Selman M, Costabel U, et al. Clinical diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(8):952-958. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-137OC. PubMed

6. Glazer CS, Rose CS, Lynch DA. Clinical and radiologic manifestations of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J Thorac Imaging. 2002;17(4):261-272. PubMed

7. Selman M, Pardo A, King TE Jr. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(4):314-324. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0513CI. PubMed

8. Calillad DM, Vergnon, JM, Madroszyk A, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage in hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a series of 139 patients. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2012;11(1):15-19. doi: 10.2174/187152812798889330. PubMed

9. Richerson HB, Bernstein IL, Fink JN, et al. Guidelines for the clinical evaluation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Report of the Subcommittee on Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;84(5 Pt 2):839-844. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90349-7. PubMed

10. Zacharisen MC, Schlueter DP, Kurup VP, Fink JN. The long-term outcome in acute, subacute, and chronic forms of pigeon breeder’s disease hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88(2):175-182. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61993-X. PubMed

11. Raymond TE, Khabbaza JE, Yadav R, Tonelli AR. Significance of main pulmonary artery dilation on imaging studies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(10):1623-1632. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201406-253PP. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Tough Egg to Crack

A 68-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with altered mental status. On the morning prior to admission, she was fully alert and oriented. Over the course of the day, she became more confused and somnolent, and by the evening, she was unarousable to voice. She had not fallen and had no head trauma.

Altered mental status may arise from metabolic (eg, hyponatremia), infectious (eg, urinary tract infection), structural (eg, subdural hematoma), or toxin-related (eg, adverse medication effect) processes. Any of these categories of encephalopathy can develop gradually over the course of a day.

One year prior, the patient was admitted for a similar episode of altered mental status. Asterixis and elevated transaminases prompted an abdominal ultrasound, which revealed a nodular liver and ascites. Paracentesis revealed a high serum-ascites albumin gradient. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was made based on these findings. Testing for viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, and Wilson’s disease were negative. Although steatosis was not detected on ultrasound, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was suspected based on the patient’s risk factors of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. She had four additional presentations of altered mental status with asterixis; each episode resolved with lactulose.

Other medical history included end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. Her medications were labetalol, amlodipine, insulin, propranolol, lactulose, and rifaximin. She was originally from China and moved to the United States 10 years earlier. Given concerns about her ability to consistently take medications, she had moved to a long-term facility. She did not use alcohol, tobacco, or illicit substances.

The normalization of the patient’s mental status after lactulose treatment, especially in the context of recurrent episodes, is characteristic of hepatic encephalopathy, in which ammonia and other substances bypass hepatic metabolism and impair cerebral function. Hepatic encephalopathy is the most common cause of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy, and may recur in the setting of infection or nonadherence with lactulose and rifaximin. Other causes of lactulose-responsive encephalopathy include hyperammonemia caused by urease-producing bacterial infection (eg, Proteus), valproic acid toxicity, and urea cycle abnormalities.

Other causes of confusion with a self-limited course should be considered for the current episode. A postictal state is possible, but convulsions were not reported. The patient is at risk of hypoglycemia from insulin use and impaired gluconeogenesis due to cirrhosis and ESRD, but low blood sugar would have likely been detected at the time of hospitalization. Finally, she might have experienced episodic encephalopathy from ingestion of unreported medications or toxins, whose effects may have resolved with abstinence during hospitalization.

The patient’s temperature was 37.8°C, pulse 73 beats/minute, blood pressure 133/69 mmHg, respiratory rate 12 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on ambient air. Her body mass index (BMI) was 19 kg/m2. She was somnolent but was moving all four extremities spontaneously. Her pupils were symmetric and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. Biceps and patellar reflexes were 2+ bilaterally. Babinski sign was absent bilaterally. The patient could not cooperate with the assessment for asterixis. Her sclerae were anicteric. The jugular venous pressure was estimated at 13 cm of water. Her heart was regular with no murmurs. Her lungs were clear. She had a distended, nontender abdomen with caput medusae. She had symmetric pitting edema in her lower extremities up to the shins.

The elevated jugular venous pressure, lower extremity edema, and distended abdomen suggest volume overload. Jugular venous distention with clear lungs is characteristic of right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular myocardial infarction, tricuspid regurgitation, or constrictive pericarditis. However, chronic biventricular heart failure often presents in this manner and is more common than the aforementioned conditions. ESRD and cirrhosis may be contributing to the hypervolemia.

Although Asian patients may exhibit metabolic syndrome and NAFLD at a lower BMI than non-Asians, her BMI is uncharacteristically low for NAFLD, especially given the increased weight expected from volume overload. There are no signs of infection to account for worsening of hepatic encephalopathy.

Laboratory tests demonstrated a white blood cell count of 4400/µL with a normal differential, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count of 108,000 per cubic millimeter. Mean corpuscular volume was 103 fL. Basic metabolic panel was normal with the exception of blood urea nitrogen of 46 mg/dL and a creatinine of 6.4 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase was 34 units/L, alanine aminotransferase 34 units/L, alkaline phosphatase 289 units/L (normal, 31-95), gamma-glutamyl transferase 104 units (GGT, normal, 12-43), total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL, and albumin 2.5 g/dL (normal, 3.5-4.5). Pro-brain natriuretic peptide was 1429 pg/mL (normal, <100). The international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.0. Urinalysis showed trace proteinuria. The chest x-ray was normal. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head demonstrated no intracranial pathology. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal-sized nodular liver, a nonocclusive portal vein thrombus (PVT), splenomegaly (15 cm in length), and trace ascites. There was no biliary dilation, hepatic steatosis, or hepatic mass.

The evolving data set presents a mixed picture about the state of the liver. The distended abdominal wall veins, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly are commonly observed in advanced cirrhosis, but these findings reflect the associated portal hypertension and not the liver disease itself. The normal bilirubin and INR suggest preserved liver function and decrease the likelihood of cirrhosis being responsible for the portal hypertension. However, the elevated alkaline phosphatase and GGT levels suggest an infiltrative liver disease, such as lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis.

Furthermore, while a nodular liver on imaging is consistent with cirrhosis, no steatosis was noted to support the presumed diagnosis of NAFLD. One explanation for this discrepancy is that fatty infiltration may be absent when NAFLD-associated cirrhosis develops. In summary, there is evidence of liver disease, and there is evidence of portal hypertension, but there is no evidence of liver parenchymal failure. The key features of the latter – spider angiomata, palmar erythema, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy – are absent.

Noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is an alternative explanation for the patient’s findings. NCPH is an elevation in the portal venous system pressure that arises from intrahepatic (but noncirrhotic) disease or from extrahepatic disease. Hepatic schistosomiasis is an example of intrahepatic but noncirrhotic portal hypertension. PVT that arises on account of a hypercoagulable condition (eg, abdominal malignancy, pancreatitis, or myeloproliferative disorders) is a prototype of extrahepatic NCPH. At this point, it is impossible to know if the PVT is a complication of NCPH or a cause of NCPH. PVT as a complication of cirrhosis is less likely.

An abdominal CT scan would better assess the hepatic parenchyma and exclude abdominal malignancies such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma. An echocardiogram is indicated to evaluate the cause of the elevated jugular venous pressure. A liver biopsy and measurement of portal venous pressure would help distinguish between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

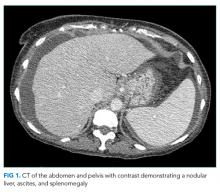

Hepatitis A, B, and C serologies were negative as were antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies. Ferritin and ceruloplasmin levels were normal. A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast demonstrated a nodular liver contour, splenomegaly, and a nonocclusive PVT (Figure 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal biventricular systolic function and size, normal diastolic function, a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 57 mmHg (normal, < 25), moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and no pericardial effusion or thickening. The patient’s confusion and somnolence resolved after two days of lactulose therapy. She denied the use of other medications, supplements, or herbs.

Pulmonary hypertension is usually a consequence of cardiopulmonary disease, but there is no exam or imaging evidence for left ventricular failure, mitral stenosis, obstructive lung disease, or interstitial lung disease. Portopulmonary hypertension (a form of pulmonary hypertension) can develop as a consequence of end-stage liver disease. The most common cause of hepatic encephalopathy due to portosystemic shunting is cirrhosis, but such shunting also arises in NCPH.

Schistosomiasis is the most common cause of NCPH worldwide. Parasite eggs trapped within the terminal portal venules cause inflammation, leading to fibrosis and intrahepatic portal hypertension. The liver becomes nodular on account of these changes, but the overall hepatic function is typically preserved. Portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, and pulmonary hypertension are common complications. The latter can arise from portosystemic shunting, which leads to embolization of schistosome eggs into the pulmonary circulation, where a granulomatous reaction ensues.

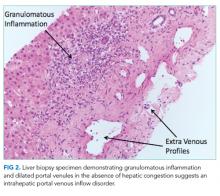

A percutaneous liver biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and dilated portal venules consistent with increased resistance to venous inflow (Figure 2). There was no sinusoidal congestion to indicate impaired hepatic venous outflow. Mild sinusoidal and portal fibrosis and increased iron in Kupffer cells were noted. There was no evidence of cirrhosis or steatohepatitis. Stains for acid-fast bacilli and fungi were negative. 16S rDNA (a test assessing for bacterial DNA) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reactions were negative. The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of noncirrhotic portal hypertension.