User login

Imposing treatment on patients with eating disorders: What are the legal risks?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the general hospital where I perform consultations, the medical service asked me to fill out psychiatric “hold” documents to keep a severely malnourished young woman with anorexia nervosa from leaving the hospital. Ms. Q, whose body mass index (BMI) was 12 (yes, 12), came to the hospital to have her “electrolytes fixed.” She was willing to stay the night for electrolyte repletion, but insisted she could gain weight on her own at home.

I’m worried that she might die without prompt inpatient treatment; she needs to stay on the medical service. Should I fill out a psychiatric hold to keep her there? What legal risks could I face if Ms. Q is detained and force-fed against her will? What are the legal risks of letting her leave the hospital before she is medically stable?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

When a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder arrives on a medical floor, treatment teams often ask psychiatric consultants to help them impose care the patient desperately needs but doesn’t want. This reaction is understandable. After all, an eating disorder is a psychiatric illness, and hospital-based psychiatrists have experience with treating involuntary patients. A psychiatric hold may seem like a sensible way to save the life of a hospitalized patient with a mental illness.

But filling out a psychiatric hold only scratches the surface of what a psychiatric consultant’s contribution should include; in Ms. Q’s case, initiating a psychiatric hold is probably the wrong thing to do.

Why would filling out a psychiatric hold be inappropriate for Ms. Q? What clinical factors and legal issues should a psychiatrist consider when helping medical colleagues provide unwanted treatment to a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder? We’ll explore these matters as we consider the case of Ms. Q (Figure) and the following questions:

- What type of care is most appropriate for her now?

- Can she refuse medical treatment?

- What are the medicolegal risks of letting her leave the hospital?

- What are the medicolegal risks of detaining and force-feeding her against her will?

- When is a psychiatric “hold” appropriate?

What care is appropriate?

Given her state of self-starvation, Ms. Q’s treatment plan could require close monitoring of her electrolytes and cardiac status, as well as watching her for signs of “refeeding syndrome”—rapid, potentially fatal fluid shifts and metabolic derangements that malnourished patients could experience when they receive artificial refeeding.1

First, the physicians who are caring for Ms. Q should determine whether she needs more intensive medical supervision than is usually available on a psychiatric unit. If she does, but she won’t agree to stay on a medical unit for care, a psychiatric hold is the wrong step, for 2 reasons:

- Once a psychiatric hold has been executed, state statutes require the patient to be placed in a psychiatric facility—a state-approved psychiatric treatment setting, such as a psychiatric unit or free-standing psychiatric hospital—within a specified period.2,3 Most nonpsychiatric medical units would not meet state’s statutory definition for such a facility.

- A psychiatric hold only permits short-term detention. It does not provide legal authority to impose unwanted medical treatment.

Does Ms. Q have capacity?

In the United States, Ms. Q has a legal right to refuse medical care—even if she needs it urgently—provided that her refusal is made competently.4 As Appelbaum and Grisso5 explained in a now-classic 1988 article:

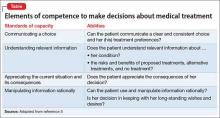

The legal standards for competence include the four related skills of communicating a choice, understanding relevant information, appreciating the current situation and its consequences, and manipulating information rationally.

The Table5 describes these abilities in more detail.

Only courts can make legal determinations of competence, so physicians refer to an evaluation of a patient’s competence-related abilities as a “capacity assessment.” The decision as to whether a patient has capacity ultimately rests with the primary treatment team; however, physicians in other specialties often enlist psychiatrists’ help with this matter because of their interviewing skills and knowledge of how mental illness can impair capacity.

No easy-to-use instrument for evaluating capacity is available. However, Appelbaum6 provides examples of questions that often prove useful in such assessments, and a review by Sessums et al7 on several capacity evaluation tools suggests that the Aid to Capacity Evaluation8 may be the best instrument for performing capacity assessments.

Patients with anorexia nervosa often differ substantially from healthy people in how they assign values to life and death,9 which can make it difficult to evaluate their capacity to refuse life-saving treatment. Malnutrition can alter patients’ ability to think clearly, a phenomenon that some patients with anorexia mention as a reason they are grateful (in retrospect) for the compulsory treatment they received.10 Yet, if an evaluation shows that the patient has the decision-making capacity to refuse care, then her (his) caregivers should carefully document this conclusion and the basis for it. Although caregivers might encourage her to accept the treatment they believe she needs, they should not provide treatment that conflicts with their patient’s wishes.

If evaluation shows that the patient lacks capacity, however, the findings that support this conclusion should be documented clearly. The team then should consult the hospital attorney to determine how to best proceed. The attorney might recommend that a physician on the primary treatment team initiate a “medical hold”—an order that the patient may not leave against medical advice (AMA)—and then seek an emergency guardianship to permit medical treatment, such as refeeding.

To treat or not to treat?

What are the legal risks of allowing Ms. Q to leave AMA before she reaches medical stability?

Powers and Cloak11 describe a case of a 26-year-old woman with anorexia nervosa who came to the hospital with dizziness, weakness, and a very low blood glucose level. She was discharged after 6 days without having received any feeding, only to return to the emergency department 2 days later. This time, she had a letter from her physician stating that she needed medical supervision to start refeeding, yet she was discharged from the emergency department within a few hours. She was re-admitted to the hospital the next day.

Powers and Cloak11 do not report this woman’s medical outcome. But what if she had suffered a fatal cardiac arrhythmia before her third presentation to the emergency department or suffered another injury attributable to her nutritional state: Could her physicians be found at fault?

On Cohen & Associates’ Web site, they essentially answer, “Yes.” They describe a case of “Miss McIntosh,” who had anorexia nervosa and was discharged home from a hospital despite “chronic metabolic problems and not eating properly.” She went into a “hypoglycemic encephalopathic coma” and “suffered irreversible brain damage.” A subsequent lawsuit against the hospital resulted in a 7-figure settlement,12 illustrating the potential for adverse medicolegal consequences if failure to treat a patient with anorexia nervosa could be linked to subsequent physical harm. On the other hand, could a patient with anorexia who is being force-fed take legal action against her providers? At least 3 recent British cases suggest that this is possible.13-15 A British medical student with anorexia, E, made an emergency application to the Court of Protection in London, claiming that being fed against her will was akin to reliving her past experience of sexual abuse. In E’s case, the judge ruled “that the balance tips slowly but unmistakably in the direction of life preserving treatment” and authorized feeding over her objection.6 In 2 other cases, however, British courts have ruled that force-feeding anorexic patients would be futile and disallowed the practice.14,15

Faced with possible legal action, no matter what course you take, how should you respond? Getting legal and ethical consultation is prudent if time allows. In many cases, hospital attorneys might prefer that physicians err on the side of preserving life(D. Vanderpool, MBA, JD, personal communication, February 3, 2016)—even if that means detaining a patient without clear legal authorization to do so—because attorneys would prefer to defend a doctor who acted to save someone’s life than to defend a doctor who knowingly allowed a patient to die.

When might persons with an eating disorder be civilly committed?

Suppose that Ms. Q does not need urgent nonpsychiatric medical care, or that her life-threatening physical problems now have been addressed. Her physicians strongly recommend that she undergo inpatient psychiatric treatment for her eating disorder, but she wants to leave. Would it now be appropriate to fill out paperwork to initiate a psychiatric hold?

All U.S. jurisdictions authorize “civil commitment” proceedings that can lead to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization of people who have a mental disorder and pose a risk to themselves or others because of the disorder.16

In general, to be subject to civil commitment, a person must have a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory. In addition, that disorder must grossly impair her (his) judgment, behavior, reality testing, or ability to meet the demands of everyday life.17

People with psychosis, a severe mood disorder, or dementia often meet these criteria. However, psychiatrists do not usually consider anorexia nervosa to be a thought disorder, mood disorder, or memory disorder. Does this mean that people with anorexia nervosa cannot meet the “substantial” mental disorder criterion?

It does not. Courts interpret the words in statutes based on their “ordinary and natural meaning.”18 If Ms. Q perceived herself as fat, despite having a BMI that was far below the healthy range, most people would regard her thinking to be disordered. If, in addition, her mental disorder impaired her “judgment, behavior, and capacity to meet the ordinary demands of sustaining existence,” then her anorexia nervosa “would qualify as a mental disorder for commitment purposes.”19

To be subject to civil commitment, a person with a substantial mental disorder also must pose a risk of harm to herself or others because of the disorder. That risk can be evidenced via an action, attempt, or threat to do direct physical harm, or it might inhere in the potential for developing grave disability through neglect of one’s basic needs, such as failing to eat adequately. In Ms. Q’s case, if the evidence shows her eating-disordered behavior has placed her at imminent risk of permanent injury or death, she has satisfied the legal criteria that justify court-ordered psychiatric hospitalization.

Bottom Line

When a severely malnourished patient with anorexia nervosa does not agree to allow recommended care, an appropriate clinical response should include judgment about the urgency of the proposed treatment, what treatment setting is best suited to the patient’s condition, and whether the patient has the mental capacity to refuse potentially life-saving care.

1. Mehanna HM, Moledina J, Travis J. Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1495-1498.

2. Ohio Revised Code §5122.01(F).

3. Oregon Revised Statutes §426.005(c).

4. Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital, 211 N.Y. 125, 105 N.E. 92 (N1914).

5. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

6. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

7. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

8. Community tools: Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE). University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics. http://www.jcb.utoronto.ca/tools/ace_download.shtml. Updated May 8, 2008. Accessed December 21, 2015.

9. Tan J, Hope T, Stewart A. Competence to refuse treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2003;26(6):697-707.

10. Elzakkers IF, Danner UN, Hoek HW, et al. Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: a review. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(8):845-852.

11. Powers PS, Cloak NL. Failure to feed patients with anorexia nervosa and other perils and perplexities in the medical care of eating disorder patients. Eat Disord. 2013;21(1):81-89.

12. “Failure to properly treat anorexia nervosa.” Harry S. Cohen & Associates. http://medmal1.com/article/failure-to-properly-treat-anorexia-nervosa. Accessed February 1, 2016.

13. A Local Authority v E. and Others [2012] EWHC 1639 (COP).

14. A NHS Foundation Trust v Ms. X [2014] EWCOP 35.

15. NHS Trust v L [2012] EWHC 2741 (COP).

16. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for civil commitment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

17. Castellano-Hoyt DW. Enhancing police response to persons in mental health crisis: providing strategies, communication techniques, and crisis intervention preparation in overcoming institutional challenges. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 2003.

18. FDIC v Meyer, 510 U.S. 471 (1994).

19. Appelbaum PS, Rumpf T. Civil commitment of the anorexic patient. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20(4):225-230.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the general hospital where I perform consultations, the medical service asked me to fill out psychiatric “hold” documents to keep a severely malnourished young woman with anorexia nervosa from leaving the hospital. Ms. Q, whose body mass index (BMI) was 12 (yes, 12), came to the hospital to have her “electrolytes fixed.” She was willing to stay the night for electrolyte repletion, but insisted she could gain weight on her own at home.

I’m worried that she might die without prompt inpatient treatment; she needs to stay on the medical service. Should I fill out a psychiatric hold to keep her there? What legal risks could I face if Ms. Q is detained and force-fed against her will? What are the legal risks of letting her leave the hospital before she is medically stable?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

When a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder arrives on a medical floor, treatment teams often ask psychiatric consultants to help them impose care the patient desperately needs but doesn’t want. This reaction is understandable. After all, an eating disorder is a psychiatric illness, and hospital-based psychiatrists have experience with treating involuntary patients. A psychiatric hold may seem like a sensible way to save the life of a hospitalized patient with a mental illness.

But filling out a psychiatric hold only scratches the surface of what a psychiatric consultant’s contribution should include; in Ms. Q’s case, initiating a psychiatric hold is probably the wrong thing to do.

Why would filling out a psychiatric hold be inappropriate for Ms. Q? What clinical factors and legal issues should a psychiatrist consider when helping medical colleagues provide unwanted treatment to a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder? We’ll explore these matters as we consider the case of Ms. Q (Figure) and the following questions:

- What type of care is most appropriate for her now?

- Can she refuse medical treatment?

- What are the medicolegal risks of letting her leave the hospital?

- What are the medicolegal risks of detaining and force-feeding her against her will?

- When is a psychiatric “hold” appropriate?

What care is appropriate?

Given her state of self-starvation, Ms. Q’s treatment plan could require close monitoring of her electrolytes and cardiac status, as well as watching her for signs of “refeeding syndrome”—rapid, potentially fatal fluid shifts and metabolic derangements that malnourished patients could experience when they receive artificial refeeding.1

First, the physicians who are caring for Ms. Q should determine whether she needs more intensive medical supervision than is usually available on a psychiatric unit. If she does, but she won’t agree to stay on a medical unit for care, a psychiatric hold is the wrong step, for 2 reasons:

- Once a psychiatric hold has been executed, state statutes require the patient to be placed in a psychiatric facility—a state-approved psychiatric treatment setting, such as a psychiatric unit or free-standing psychiatric hospital—within a specified period.2,3 Most nonpsychiatric medical units would not meet state’s statutory definition for such a facility.

- A psychiatric hold only permits short-term detention. It does not provide legal authority to impose unwanted medical treatment.

Does Ms. Q have capacity?

In the United States, Ms. Q has a legal right to refuse medical care—even if she needs it urgently—provided that her refusal is made competently.4 As Appelbaum and Grisso5 explained in a now-classic 1988 article:

The legal standards for competence include the four related skills of communicating a choice, understanding relevant information, appreciating the current situation and its consequences, and manipulating information rationally.

The Table5 describes these abilities in more detail.

Only courts can make legal determinations of competence, so physicians refer to an evaluation of a patient’s competence-related abilities as a “capacity assessment.” The decision as to whether a patient has capacity ultimately rests with the primary treatment team; however, physicians in other specialties often enlist psychiatrists’ help with this matter because of their interviewing skills and knowledge of how mental illness can impair capacity.

No easy-to-use instrument for evaluating capacity is available. However, Appelbaum6 provides examples of questions that often prove useful in such assessments, and a review by Sessums et al7 on several capacity evaluation tools suggests that the Aid to Capacity Evaluation8 may be the best instrument for performing capacity assessments.

Patients with anorexia nervosa often differ substantially from healthy people in how they assign values to life and death,9 which can make it difficult to evaluate their capacity to refuse life-saving treatment. Malnutrition can alter patients’ ability to think clearly, a phenomenon that some patients with anorexia mention as a reason they are grateful (in retrospect) for the compulsory treatment they received.10 Yet, if an evaluation shows that the patient has the decision-making capacity to refuse care, then her (his) caregivers should carefully document this conclusion and the basis for it. Although caregivers might encourage her to accept the treatment they believe she needs, they should not provide treatment that conflicts with their patient’s wishes.

If evaluation shows that the patient lacks capacity, however, the findings that support this conclusion should be documented clearly. The team then should consult the hospital attorney to determine how to best proceed. The attorney might recommend that a physician on the primary treatment team initiate a “medical hold”—an order that the patient may not leave against medical advice (AMA)—and then seek an emergency guardianship to permit medical treatment, such as refeeding.

To treat or not to treat?

What are the legal risks of allowing Ms. Q to leave AMA before she reaches medical stability?

Powers and Cloak11 describe a case of a 26-year-old woman with anorexia nervosa who came to the hospital with dizziness, weakness, and a very low blood glucose level. She was discharged after 6 days without having received any feeding, only to return to the emergency department 2 days later. This time, she had a letter from her physician stating that she needed medical supervision to start refeeding, yet she was discharged from the emergency department within a few hours. She was re-admitted to the hospital the next day.

Powers and Cloak11 do not report this woman’s medical outcome. But what if she had suffered a fatal cardiac arrhythmia before her third presentation to the emergency department or suffered another injury attributable to her nutritional state: Could her physicians be found at fault?

On Cohen & Associates’ Web site, they essentially answer, “Yes.” They describe a case of “Miss McIntosh,” who had anorexia nervosa and was discharged home from a hospital despite “chronic metabolic problems and not eating properly.” She went into a “hypoglycemic encephalopathic coma” and “suffered irreversible brain damage.” A subsequent lawsuit against the hospital resulted in a 7-figure settlement,12 illustrating the potential for adverse medicolegal consequences if failure to treat a patient with anorexia nervosa could be linked to subsequent physical harm. On the other hand, could a patient with anorexia who is being force-fed take legal action against her providers? At least 3 recent British cases suggest that this is possible.13-15 A British medical student with anorexia, E, made an emergency application to the Court of Protection in London, claiming that being fed against her will was akin to reliving her past experience of sexual abuse. In E’s case, the judge ruled “that the balance tips slowly but unmistakably in the direction of life preserving treatment” and authorized feeding over her objection.6 In 2 other cases, however, British courts have ruled that force-feeding anorexic patients would be futile and disallowed the practice.14,15

Faced with possible legal action, no matter what course you take, how should you respond? Getting legal and ethical consultation is prudent if time allows. In many cases, hospital attorneys might prefer that physicians err on the side of preserving life(D. Vanderpool, MBA, JD, personal communication, February 3, 2016)—even if that means detaining a patient without clear legal authorization to do so—because attorneys would prefer to defend a doctor who acted to save someone’s life than to defend a doctor who knowingly allowed a patient to die.

When might persons with an eating disorder be civilly committed?

Suppose that Ms. Q does not need urgent nonpsychiatric medical care, or that her life-threatening physical problems now have been addressed. Her physicians strongly recommend that she undergo inpatient psychiatric treatment for her eating disorder, but she wants to leave. Would it now be appropriate to fill out paperwork to initiate a psychiatric hold?

All U.S. jurisdictions authorize “civil commitment” proceedings that can lead to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization of people who have a mental disorder and pose a risk to themselves or others because of the disorder.16

In general, to be subject to civil commitment, a person must have a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory. In addition, that disorder must grossly impair her (his) judgment, behavior, reality testing, or ability to meet the demands of everyday life.17

People with psychosis, a severe mood disorder, or dementia often meet these criteria. However, psychiatrists do not usually consider anorexia nervosa to be a thought disorder, mood disorder, or memory disorder. Does this mean that people with anorexia nervosa cannot meet the “substantial” mental disorder criterion?

It does not. Courts interpret the words in statutes based on their “ordinary and natural meaning.”18 If Ms. Q perceived herself as fat, despite having a BMI that was far below the healthy range, most people would regard her thinking to be disordered. If, in addition, her mental disorder impaired her “judgment, behavior, and capacity to meet the ordinary demands of sustaining existence,” then her anorexia nervosa “would qualify as a mental disorder for commitment purposes.”19

To be subject to civil commitment, a person with a substantial mental disorder also must pose a risk of harm to herself or others because of the disorder. That risk can be evidenced via an action, attempt, or threat to do direct physical harm, or it might inhere in the potential for developing grave disability through neglect of one’s basic needs, such as failing to eat adequately. In Ms. Q’s case, if the evidence shows her eating-disordered behavior has placed her at imminent risk of permanent injury or death, she has satisfied the legal criteria that justify court-ordered psychiatric hospitalization.

Bottom Line

When a severely malnourished patient with anorexia nervosa does not agree to allow recommended care, an appropriate clinical response should include judgment about the urgency of the proposed treatment, what treatment setting is best suited to the patient’s condition, and whether the patient has the mental capacity to refuse potentially life-saving care.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the general hospital where I perform consultations, the medical service asked me to fill out psychiatric “hold” documents to keep a severely malnourished young woman with anorexia nervosa from leaving the hospital. Ms. Q, whose body mass index (BMI) was 12 (yes, 12), came to the hospital to have her “electrolytes fixed.” She was willing to stay the night for electrolyte repletion, but insisted she could gain weight on her own at home.

I’m worried that she might die without prompt inpatient treatment; she needs to stay on the medical service. Should I fill out a psychiatric hold to keep her there? What legal risks could I face if Ms. Q is detained and force-fed against her will? What are the legal risks of letting her leave the hospital before she is medically stable?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

When a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder arrives on a medical floor, treatment teams often ask psychiatric consultants to help them impose care the patient desperately needs but doesn’t want. This reaction is understandable. After all, an eating disorder is a psychiatric illness, and hospital-based psychiatrists have experience with treating involuntary patients. A psychiatric hold may seem like a sensible way to save the life of a hospitalized patient with a mental illness.

But filling out a psychiatric hold only scratches the surface of what a psychiatric consultant’s contribution should include; in Ms. Q’s case, initiating a psychiatric hold is probably the wrong thing to do.

Why would filling out a psychiatric hold be inappropriate for Ms. Q? What clinical factors and legal issues should a psychiatrist consider when helping medical colleagues provide unwanted treatment to a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder? We’ll explore these matters as we consider the case of Ms. Q (Figure) and the following questions:

- What type of care is most appropriate for her now?

- Can she refuse medical treatment?

- What are the medicolegal risks of letting her leave the hospital?

- What are the medicolegal risks of detaining and force-feeding her against her will?

- When is a psychiatric “hold” appropriate?

What care is appropriate?

Given her state of self-starvation, Ms. Q’s treatment plan could require close monitoring of her electrolytes and cardiac status, as well as watching her for signs of “refeeding syndrome”—rapid, potentially fatal fluid shifts and metabolic derangements that malnourished patients could experience when they receive artificial refeeding.1

First, the physicians who are caring for Ms. Q should determine whether she needs more intensive medical supervision than is usually available on a psychiatric unit. If she does, but she won’t agree to stay on a medical unit for care, a psychiatric hold is the wrong step, for 2 reasons:

- Once a psychiatric hold has been executed, state statutes require the patient to be placed in a psychiatric facility—a state-approved psychiatric treatment setting, such as a psychiatric unit or free-standing psychiatric hospital—within a specified period.2,3 Most nonpsychiatric medical units would not meet state’s statutory definition for such a facility.

- A psychiatric hold only permits short-term detention. It does not provide legal authority to impose unwanted medical treatment.

Does Ms. Q have capacity?

In the United States, Ms. Q has a legal right to refuse medical care—even if she needs it urgently—provided that her refusal is made competently.4 As Appelbaum and Grisso5 explained in a now-classic 1988 article:

The legal standards for competence include the four related skills of communicating a choice, understanding relevant information, appreciating the current situation and its consequences, and manipulating information rationally.

The Table5 describes these abilities in more detail.

Only courts can make legal determinations of competence, so physicians refer to an evaluation of a patient’s competence-related abilities as a “capacity assessment.” The decision as to whether a patient has capacity ultimately rests with the primary treatment team; however, physicians in other specialties often enlist psychiatrists’ help with this matter because of their interviewing skills and knowledge of how mental illness can impair capacity.

No easy-to-use instrument for evaluating capacity is available. However, Appelbaum6 provides examples of questions that often prove useful in such assessments, and a review by Sessums et al7 on several capacity evaluation tools suggests that the Aid to Capacity Evaluation8 may be the best instrument for performing capacity assessments.

Patients with anorexia nervosa often differ substantially from healthy people in how they assign values to life and death,9 which can make it difficult to evaluate their capacity to refuse life-saving treatment. Malnutrition can alter patients’ ability to think clearly, a phenomenon that some patients with anorexia mention as a reason they are grateful (in retrospect) for the compulsory treatment they received.10 Yet, if an evaluation shows that the patient has the decision-making capacity to refuse care, then her (his) caregivers should carefully document this conclusion and the basis for it. Although caregivers might encourage her to accept the treatment they believe she needs, they should not provide treatment that conflicts with their patient’s wishes.

If evaluation shows that the patient lacks capacity, however, the findings that support this conclusion should be documented clearly. The team then should consult the hospital attorney to determine how to best proceed. The attorney might recommend that a physician on the primary treatment team initiate a “medical hold”—an order that the patient may not leave against medical advice (AMA)—and then seek an emergency guardianship to permit medical treatment, such as refeeding.

To treat or not to treat?

What are the legal risks of allowing Ms. Q to leave AMA before she reaches medical stability?

Powers and Cloak11 describe a case of a 26-year-old woman with anorexia nervosa who came to the hospital with dizziness, weakness, and a very low blood glucose level. She was discharged after 6 days without having received any feeding, only to return to the emergency department 2 days later. This time, she had a letter from her physician stating that she needed medical supervision to start refeeding, yet she was discharged from the emergency department within a few hours. She was re-admitted to the hospital the next day.

Powers and Cloak11 do not report this woman’s medical outcome. But what if she had suffered a fatal cardiac arrhythmia before her third presentation to the emergency department or suffered another injury attributable to her nutritional state: Could her physicians be found at fault?

On Cohen & Associates’ Web site, they essentially answer, “Yes.” They describe a case of “Miss McIntosh,” who had anorexia nervosa and was discharged home from a hospital despite “chronic metabolic problems and not eating properly.” She went into a “hypoglycemic encephalopathic coma” and “suffered irreversible brain damage.” A subsequent lawsuit against the hospital resulted in a 7-figure settlement,12 illustrating the potential for adverse medicolegal consequences if failure to treat a patient with anorexia nervosa could be linked to subsequent physical harm. On the other hand, could a patient with anorexia who is being force-fed take legal action against her providers? At least 3 recent British cases suggest that this is possible.13-15 A British medical student with anorexia, E, made an emergency application to the Court of Protection in London, claiming that being fed against her will was akin to reliving her past experience of sexual abuse. In E’s case, the judge ruled “that the balance tips slowly but unmistakably in the direction of life preserving treatment” and authorized feeding over her objection.6 In 2 other cases, however, British courts have ruled that force-feeding anorexic patients would be futile and disallowed the practice.14,15

Faced with possible legal action, no matter what course you take, how should you respond? Getting legal and ethical consultation is prudent if time allows. In many cases, hospital attorneys might prefer that physicians err on the side of preserving life(D. Vanderpool, MBA, JD, personal communication, February 3, 2016)—even if that means detaining a patient without clear legal authorization to do so—because attorneys would prefer to defend a doctor who acted to save someone’s life than to defend a doctor who knowingly allowed a patient to die.

When might persons with an eating disorder be civilly committed?

Suppose that Ms. Q does not need urgent nonpsychiatric medical care, or that her life-threatening physical problems now have been addressed. Her physicians strongly recommend that she undergo inpatient psychiatric treatment for her eating disorder, but she wants to leave. Would it now be appropriate to fill out paperwork to initiate a psychiatric hold?

All U.S. jurisdictions authorize “civil commitment” proceedings that can lead to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization of people who have a mental disorder and pose a risk to themselves or others because of the disorder.16

In general, to be subject to civil commitment, a person must have a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory. In addition, that disorder must grossly impair her (his) judgment, behavior, reality testing, or ability to meet the demands of everyday life.17

People with psychosis, a severe mood disorder, or dementia often meet these criteria. However, psychiatrists do not usually consider anorexia nervosa to be a thought disorder, mood disorder, or memory disorder. Does this mean that people with anorexia nervosa cannot meet the “substantial” mental disorder criterion?

It does not. Courts interpret the words in statutes based on their “ordinary and natural meaning.”18 If Ms. Q perceived herself as fat, despite having a BMI that was far below the healthy range, most people would regard her thinking to be disordered. If, in addition, her mental disorder impaired her “judgment, behavior, and capacity to meet the ordinary demands of sustaining existence,” then her anorexia nervosa “would qualify as a mental disorder for commitment purposes.”19

To be subject to civil commitment, a person with a substantial mental disorder also must pose a risk of harm to herself or others because of the disorder. That risk can be evidenced via an action, attempt, or threat to do direct physical harm, or it might inhere in the potential for developing grave disability through neglect of one’s basic needs, such as failing to eat adequately. In Ms. Q’s case, if the evidence shows her eating-disordered behavior has placed her at imminent risk of permanent injury or death, she has satisfied the legal criteria that justify court-ordered psychiatric hospitalization.

Bottom Line

When a severely malnourished patient with anorexia nervosa does not agree to allow recommended care, an appropriate clinical response should include judgment about the urgency of the proposed treatment, what treatment setting is best suited to the patient’s condition, and whether the patient has the mental capacity to refuse potentially life-saving care.

1. Mehanna HM, Moledina J, Travis J. Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1495-1498.

2. Ohio Revised Code §5122.01(F).

3. Oregon Revised Statutes §426.005(c).

4. Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital, 211 N.Y. 125, 105 N.E. 92 (N1914).

5. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

6. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

7. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

8. Community tools: Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE). University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics. http://www.jcb.utoronto.ca/tools/ace_download.shtml. Updated May 8, 2008. Accessed December 21, 2015.

9. Tan J, Hope T, Stewart A. Competence to refuse treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2003;26(6):697-707.

10. Elzakkers IF, Danner UN, Hoek HW, et al. Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: a review. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(8):845-852.

11. Powers PS, Cloak NL. Failure to feed patients with anorexia nervosa and other perils and perplexities in the medical care of eating disorder patients. Eat Disord. 2013;21(1):81-89.

12. “Failure to properly treat anorexia nervosa.” Harry S. Cohen & Associates. http://medmal1.com/article/failure-to-properly-treat-anorexia-nervosa. Accessed February 1, 2016.

13. A Local Authority v E. and Others [2012] EWHC 1639 (COP).

14. A NHS Foundation Trust v Ms. X [2014] EWCOP 35.

15. NHS Trust v L [2012] EWHC 2741 (COP).

16. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for civil commitment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

17. Castellano-Hoyt DW. Enhancing police response to persons in mental health crisis: providing strategies, communication techniques, and crisis intervention preparation in overcoming institutional challenges. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 2003.

18. FDIC v Meyer, 510 U.S. 471 (1994).

19. Appelbaum PS, Rumpf T. Civil commitment of the anorexic patient. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20(4):225-230.

1. Mehanna HM, Moledina J, Travis J. Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1495-1498.

2. Ohio Revised Code §5122.01(F).

3. Oregon Revised Statutes §426.005(c).

4. Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital, 211 N.Y. 125, 105 N.E. 92 (N1914).

5. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

6. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

7. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

8. Community tools: Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE). University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics. http://www.jcb.utoronto.ca/tools/ace_download.shtml. Updated May 8, 2008. Accessed December 21, 2015.

9. Tan J, Hope T, Stewart A. Competence to refuse treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2003;26(6):697-707.

10. Elzakkers IF, Danner UN, Hoek HW, et al. Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: a review. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(8):845-852.

11. Powers PS, Cloak NL. Failure to feed patients with anorexia nervosa and other perils and perplexities in the medical care of eating disorder patients. Eat Disord. 2013;21(1):81-89.

12. “Failure to properly treat anorexia nervosa.” Harry S. Cohen & Associates. http://medmal1.com/article/failure-to-properly-treat-anorexia-nervosa. Accessed February 1, 2016.

13. A Local Authority v E. and Others [2012] EWHC 1639 (COP).

14. A NHS Foundation Trust v Ms. X [2014] EWCOP 35.

15. NHS Trust v L [2012] EWHC 2741 (COP).

16. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for civil commitment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

17. Castellano-Hoyt DW. Enhancing police response to persons in mental health crisis: providing strategies, communication techniques, and crisis intervention preparation in overcoming institutional challenges. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 2003.

18. FDIC v Meyer, 510 U.S. 471 (1994).

19. Appelbaum PS, Rumpf T. Civil commitment of the anorexic patient. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20(4):225-230.