User login

Developing a career in medical pancreatology: An emerging postfellowship career path

Although described by the Greek physician Herophilos around 300 B.C., it was not until the 19th century that enzymes began to be isolated from pancreatic secretions and their digestive action described, and not until early in the 20th century that Banting, Macleod, and Best received the Nobel prize for purifying insulin from the pancreata of dogs. For centuries in between, the pancreas was considered to be just a ‘beautiful piece of flesh’ (kallikreas), the main role of which was to protect the blood vessels in the abdomen and to serve as a cushion to the stomach.1 Certainly, the pancreas has come a long way since then but, like most other organs in the body, is oft ignored until it develops issues.

Like many other disorders in gastroenterology, pancreatic disorders were historically approached as mechanical or “plumbing” issues. As modern technology and innovation percolated through the world of endoscopy, a wide array of state-of-the-art tools were devised. Availability of newer “toys” and development of newer techniques also means that an ever-increasing curriculum has been squeezed into a generally single year of therapeutic endoscopy training, such that trainees can no longer limit themselves to learning only endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or intervening on pancreatic disease alone. Modern, subspecialized approaches to disease and economic considerations often dictate that the therapeutic endoscopist of today must perform a wide range of procedures besides ERCP and EUS, such as advanced resection using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), endoscopic bariatric procedures, and newer techniques and acronyms that continue to evolve on a regular basis. This leaves the therapeutic endoscopist with little time for outpatient management of many patients that don’t need interventional procedures but are often very complex and need ongoing, long-term follow-up. In addition, any clinic slots available for interventional endoscopists may be utilized by patients coming in to discuss complex procedures or for postprocedure follow-up. Endoscopic management is not the definitive treatment for most pancreatic disorders. In fact, as our knowledge of pancreatic disease has continued to evolve, endoscopic intervention is now required in a minority of cases.

Role of the medical pancreatologist

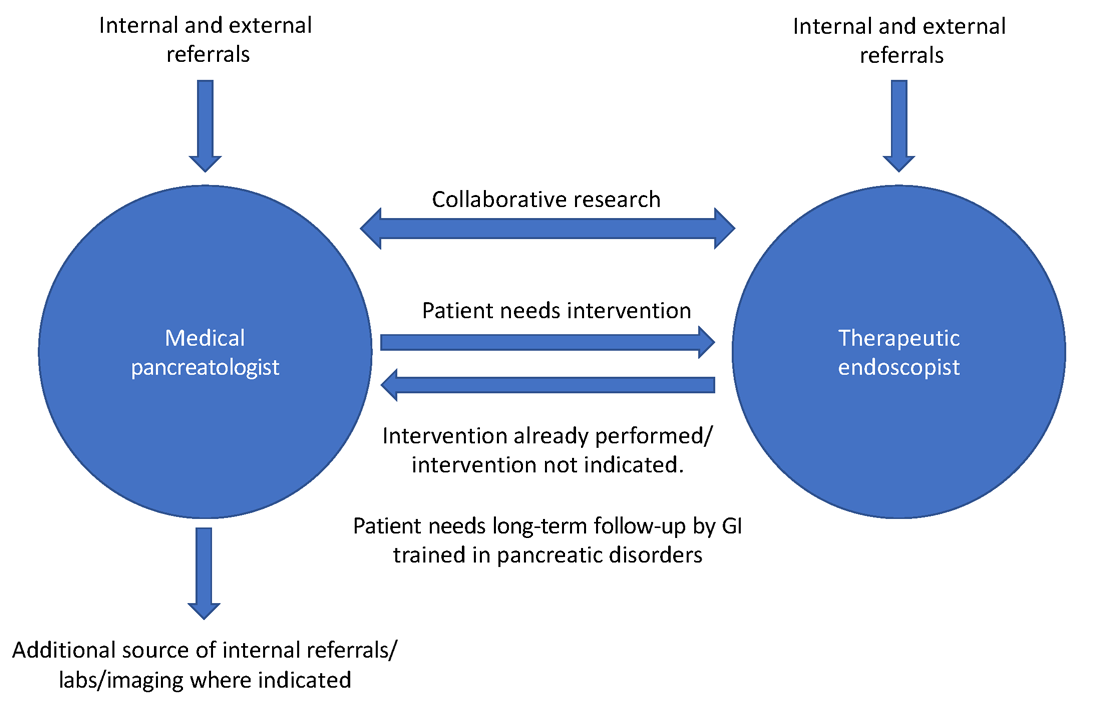

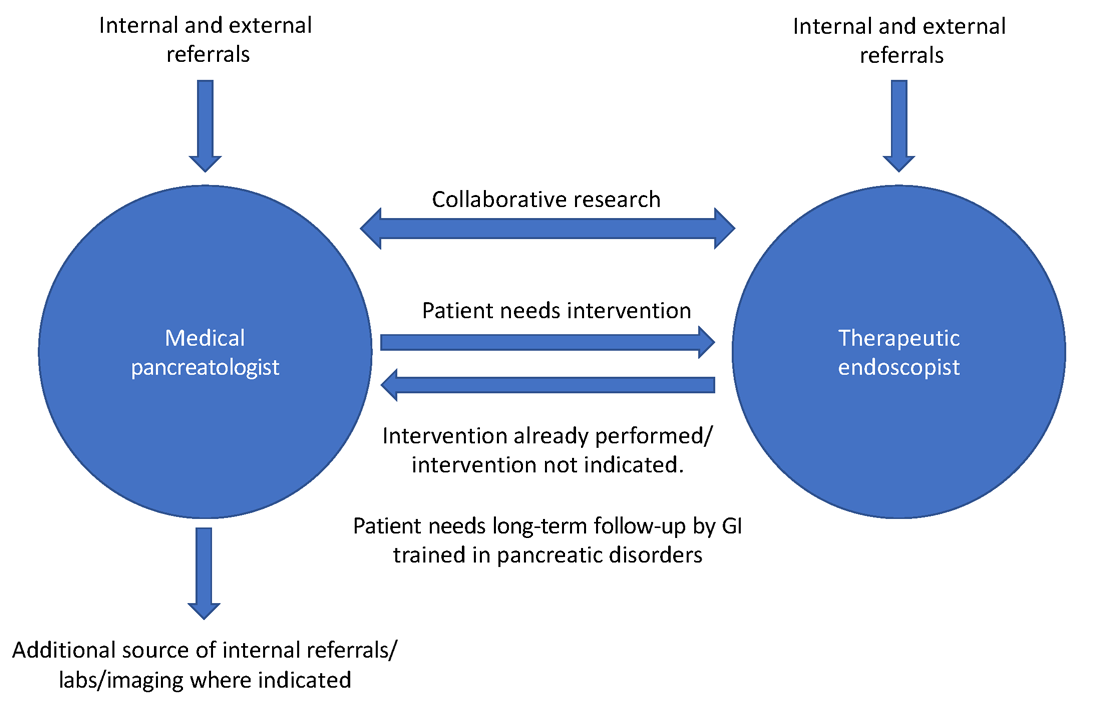

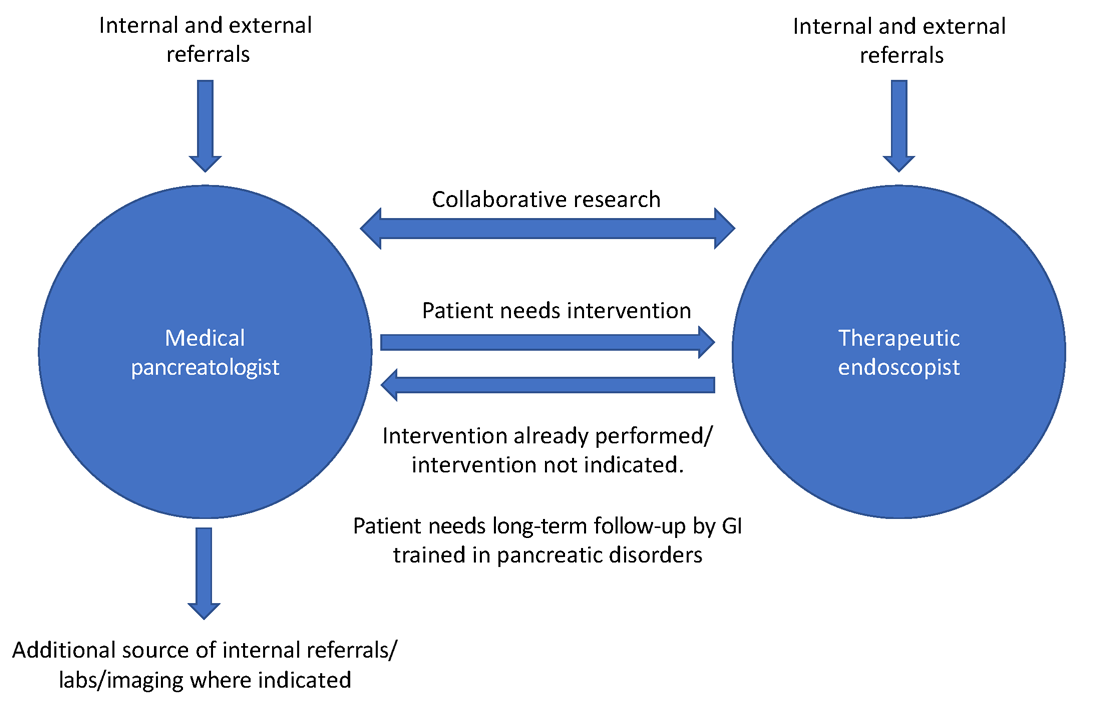

Patient Care

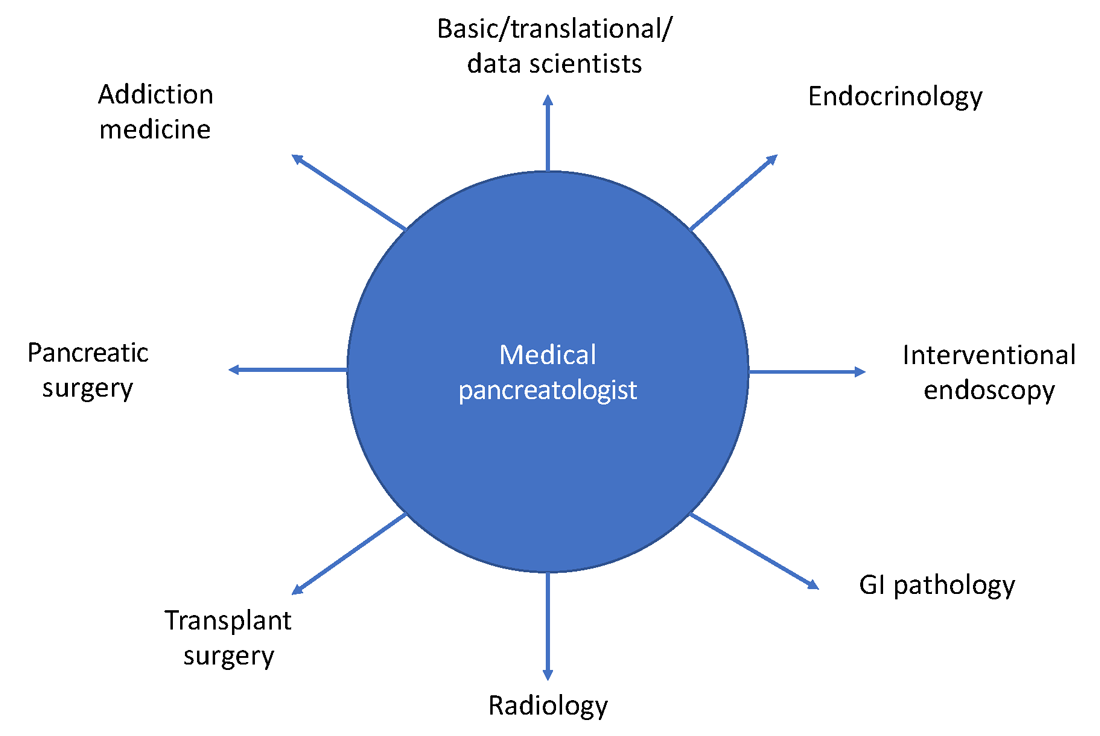

As part of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary team that also includes an interventional gastroenterologist, pancreatic surgeon, transplant surgeon (in centers offering islet autotransplantation with total pancreatectomy), radiology, endocrinology, and GI pathologist, the medical pancreatologist helps lead the care of patients with pancreatic disorders, such as pancreatic cysts, acute and chronic pancreatitis (especially in cases where there is no role for active endoscopic intervention), autoimmune pancreatitis, indeterminate pancreatic masses, as well as screens high-risk patients for pancreatic cancer in conjunction with a genetic counselor. The medical pancreatologist often also serves as a bridge between various members of a large multidisciplinary team that, formally in the form of conferences or informally, discusses the management of complex patients, with each member available to help the other based on the patient’s most immediate clinical need at that time. A schematic showing how the medical pancreatologist collaborates with the therapeutic endoscopist is provided in Figure 1.

Uzma Siddiqui, MD, director for the Center for Endoscopic Research and Technology (CERT) at the University of Chicago said, “The management of pancreatic diseases is often challenging. Surgeons and endoscopists can offer some treatments that focus on one aspect or symptom, but the medical pancreatologist brings focus to the patient as a whole and helps organize care. It is only with everyone’s combined efforts and the added perspective of the medical pancreatologist that we can provide the best care for our shared patients.”

David Xin, MD, MPH, a medical pancreatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, added, “I am often asked what it means to be a medical pancreatologist. What do I do if not EUS and ERCP? I provide longitudinal care, coordinate multidisciplinary management, assess nutritional status, optimize quality of life, and manage pain. But perhaps most importantly, I make myself available for patients who seek understanding and sympathy regarding their complex disease. I became a medical pancreatologist because my mentors during training helped me recognize how rewarding this career would be.”

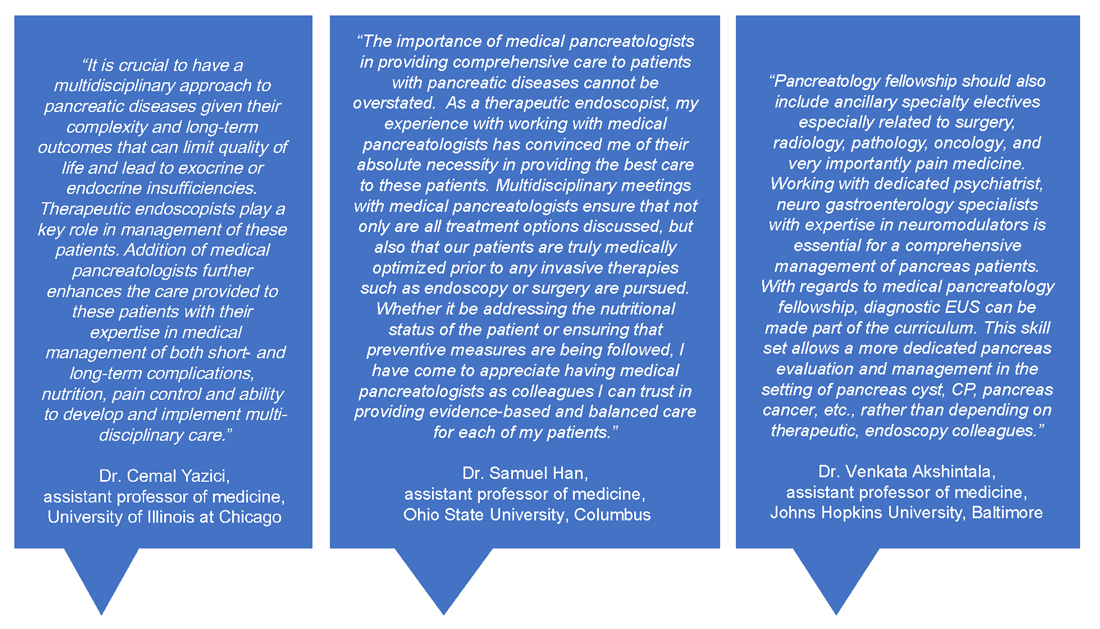

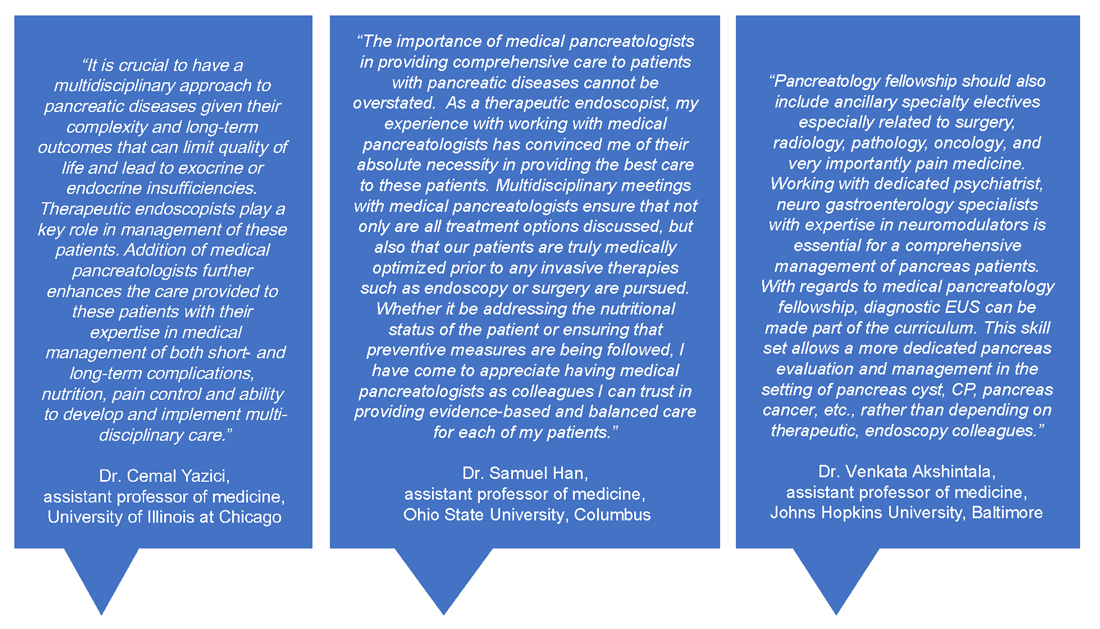

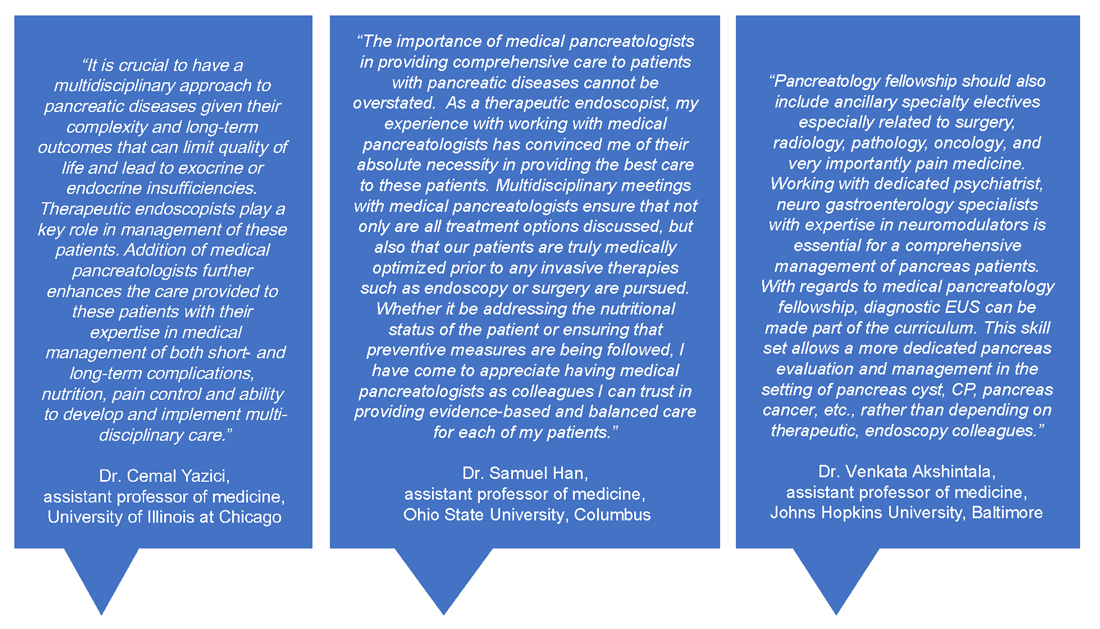

Insights from other medical pancreatologists and therapeutic endoscopists are provided in Figure 2.

Education

Having a dedicated medical pancreatology clinic has the potential to add a unique element to the training of gastroenterology fellows. In my own experience, besides fellows interested in medical pancreatology, even those interested in therapeutic endoscopy find it useful to rotate through the pancreas clinic and follow patients after or leading to their procedures, becoming comfortable with noninterventional pain management of patients with pancreatic disorders and risk stratification of pancreatic cystic lesions, and learning about the management of rare disorders such as autoimmune pancreatitis. Most importantly, this allows trainees to identify cases where endoscopic intervention may not offer definitive treatment for complex conditions such as pancreatic pain. Trainee-centered organizations such as the Collaborative Alliance for Pancreatic Education and Research (CAPER) enable trainees and young investigators to network with other physicians who are passionate about the pancreas and establish early research collaborations for current and future research endeavors that will help advance this field.

Research

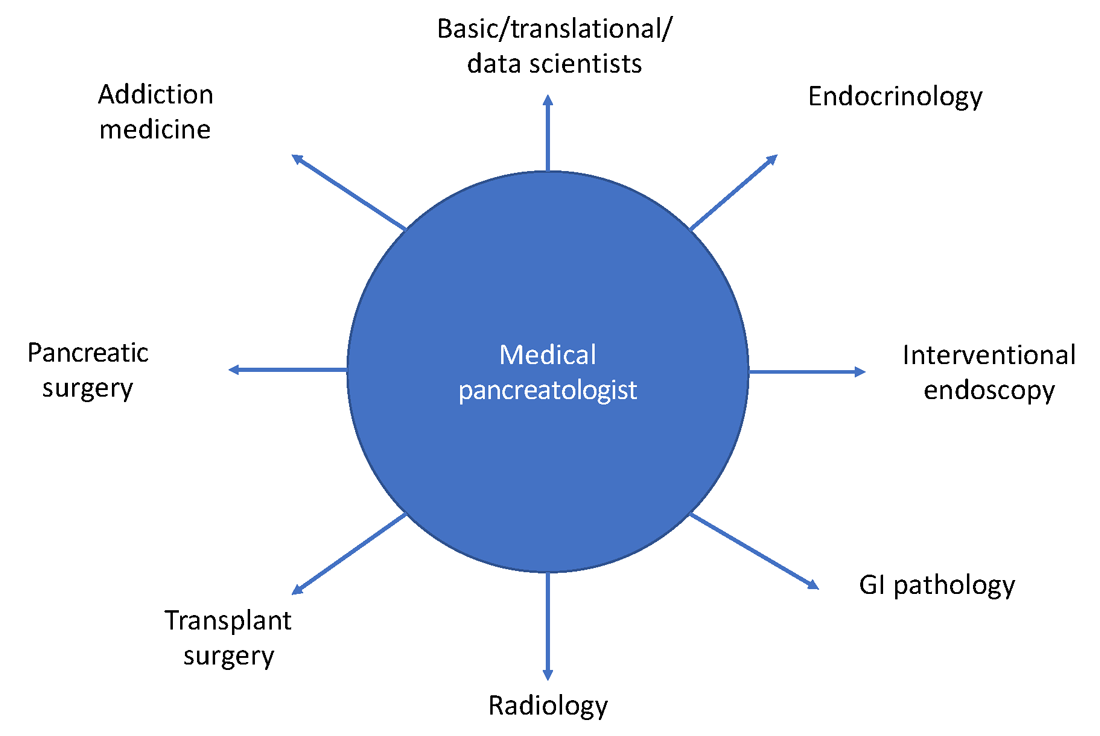

Having a trained medical pancreatologist adds the possibility of adding a unique angle to ongoing research within a gastroenterology division, especially in collaboration with others. For example, during my fellowship training I was able to focus on histological changes in pancreatic islets of patients with pancreatic cancer that develop diabetes, compared with those that do not, in collaboration with a pathologist who focused on studying islet pathology and under the guidance of my mentor, Dr. Suresh Chari, a medical pancreatologist.2 I was also part of other studies within the GI division with other medical pancreatologists, such as Dr. Santhi Vege and Dr. Shounak Majumder, who have continued to serve as career and research mentors.3 Collaborative, multicenter studies on pancreatic disease are also conducted by CAPER, the organization mentioned above. A list of potential collaborations for the fellow interested

in medical pancreatology is provided in Figure 3.

Marketing considerations for the gastroenterology division

Having a medical pancreatologist in the team is not only attractive for referring physicians within an institution but is often a great asset from a marketing standpoint, especially for tertiary care academic centers and large community practices with a broad referral base. Given that there are a limited number of medical pancreatologists in the country, having one as part of the faculty can certainly provide a competitive edge to that center within the area, especially with an ever-increasing preference of patients for hyperspecialized care.

How to develop a career in medical pancreatology

Gastroenterology fellows often start their fellowships “undifferentiated” and try to get exposed to a wide variety of GI pathology, either through general GI clinics or as part of subspecialized clinics, as they attempt to decide how they want their careers to look down the line. Similar to other subspecialities, if a trainee has already decided to pursue medical pancreatology (as happened in my case), they should strongly consider ranking programs with available opportunities for research/clinic in medical pancreatology and ideally undergo an additional year of training. Fellows who decide during the course of their fellowship that they want to pursue a career in medical pancreatology should consider applying for a 4th year in the subject to not only obtain further training in the field but to also conduct research in the area and become more “marketable” as a person that could start a medical pancreatology program at their future academic or community position. Trainees interested in medical pancreatology should try to focus their time on long-term, clinical management of patients with pancreatic disorders, engaging a multidisciplinary team composed of interventional endoscopists, pancreatic surgeons, transplant surgeons (if total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation is available), radiology, addiction medicine (if available), endocrinology, and pathology. The list of places that offer a 4th year in medical pancreatology is increasing every year, and as of the writing of this article there are six programs that have this opportunity, which include:

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Penn.

The CAPER website is also a great resource for education as well as for identifying potential medical pancreatology programs.

In summary, medical pancreatology is an evolving and rapidly growing career path for gastroenterology fellows interested in providing care to patients with pancreatic disease in close collaboration with multiple other subspecialties, especially therapeutic endoscopy and pancreatic surgery. The field is also ripe for fellows interested in clinical, translational, and basic science research related to pancreatic disorders.

Dr. Nagpal is assistant professor of medicine, director, pancreas clinic, University of Chicago. He had no conflicts to disclose.

References

1. Feldman M et al. “Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease,” 11th ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2021).

2. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2020 Jul;20(5):929-35.

3. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2019 Mar;19(2):290-5.

Although described by the Greek physician Herophilos around 300 B.C., it was not until the 19th century that enzymes began to be isolated from pancreatic secretions and their digestive action described, and not until early in the 20th century that Banting, Macleod, and Best received the Nobel prize for purifying insulin from the pancreata of dogs. For centuries in between, the pancreas was considered to be just a ‘beautiful piece of flesh’ (kallikreas), the main role of which was to protect the blood vessels in the abdomen and to serve as a cushion to the stomach.1 Certainly, the pancreas has come a long way since then but, like most other organs in the body, is oft ignored until it develops issues.

Like many other disorders in gastroenterology, pancreatic disorders were historically approached as mechanical or “plumbing” issues. As modern technology and innovation percolated through the world of endoscopy, a wide array of state-of-the-art tools were devised. Availability of newer “toys” and development of newer techniques also means that an ever-increasing curriculum has been squeezed into a generally single year of therapeutic endoscopy training, such that trainees can no longer limit themselves to learning only endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or intervening on pancreatic disease alone. Modern, subspecialized approaches to disease and economic considerations often dictate that the therapeutic endoscopist of today must perform a wide range of procedures besides ERCP and EUS, such as advanced resection using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), endoscopic bariatric procedures, and newer techniques and acronyms that continue to evolve on a regular basis. This leaves the therapeutic endoscopist with little time for outpatient management of many patients that don’t need interventional procedures but are often very complex and need ongoing, long-term follow-up. In addition, any clinic slots available for interventional endoscopists may be utilized by patients coming in to discuss complex procedures or for postprocedure follow-up. Endoscopic management is not the definitive treatment for most pancreatic disorders. In fact, as our knowledge of pancreatic disease has continued to evolve, endoscopic intervention is now required in a minority of cases.

Role of the medical pancreatologist

Patient Care

As part of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary team that also includes an interventional gastroenterologist, pancreatic surgeon, transplant surgeon (in centers offering islet autotransplantation with total pancreatectomy), radiology, endocrinology, and GI pathologist, the medical pancreatologist helps lead the care of patients with pancreatic disorders, such as pancreatic cysts, acute and chronic pancreatitis (especially in cases where there is no role for active endoscopic intervention), autoimmune pancreatitis, indeterminate pancreatic masses, as well as screens high-risk patients for pancreatic cancer in conjunction with a genetic counselor. The medical pancreatologist often also serves as a bridge between various members of a large multidisciplinary team that, formally in the form of conferences or informally, discusses the management of complex patients, with each member available to help the other based on the patient’s most immediate clinical need at that time. A schematic showing how the medical pancreatologist collaborates with the therapeutic endoscopist is provided in Figure 1.

Uzma Siddiqui, MD, director for the Center for Endoscopic Research and Technology (CERT) at the University of Chicago said, “The management of pancreatic diseases is often challenging. Surgeons and endoscopists can offer some treatments that focus on one aspect or symptom, but the medical pancreatologist brings focus to the patient as a whole and helps organize care. It is only with everyone’s combined efforts and the added perspective of the medical pancreatologist that we can provide the best care for our shared patients.”

David Xin, MD, MPH, a medical pancreatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, added, “I am often asked what it means to be a medical pancreatologist. What do I do if not EUS and ERCP? I provide longitudinal care, coordinate multidisciplinary management, assess nutritional status, optimize quality of life, and manage pain. But perhaps most importantly, I make myself available for patients who seek understanding and sympathy regarding their complex disease. I became a medical pancreatologist because my mentors during training helped me recognize how rewarding this career would be.”

Insights from other medical pancreatologists and therapeutic endoscopists are provided in Figure 2.

Education

Having a dedicated medical pancreatology clinic has the potential to add a unique element to the training of gastroenterology fellows. In my own experience, besides fellows interested in medical pancreatology, even those interested in therapeutic endoscopy find it useful to rotate through the pancreas clinic and follow patients after or leading to their procedures, becoming comfortable with noninterventional pain management of patients with pancreatic disorders and risk stratification of pancreatic cystic lesions, and learning about the management of rare disorders such as autoimmune pancreatitis. Most importantly, this allows trainees to identify cases where endoscopic intervention may not offer definitive treatment for complex conditions such as pancreatic pain. Trainee-centered organizations such as the Collaborative Alliance for Pancreatic Education and Research (CAPER) enable trainees and young investigators to network with other physicians who are passionate about the pancreas and establish early research collaborations for current and future research endeavors that will help advance this field.

Research

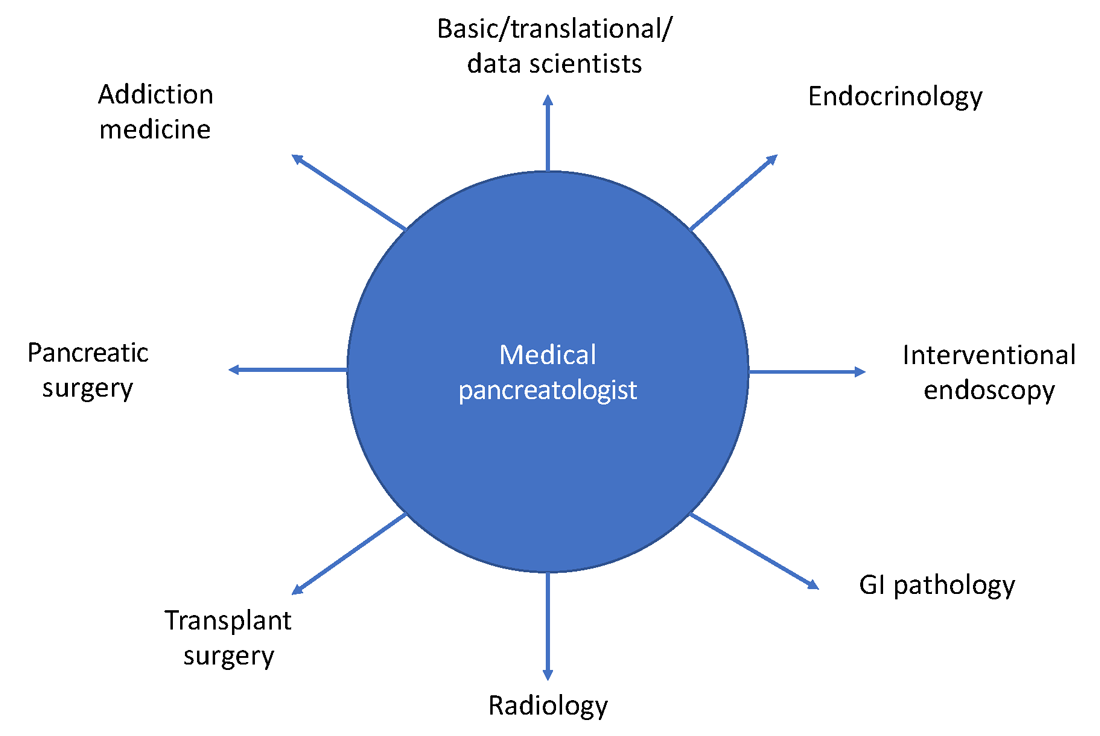

Having a trained medical pancreatologist adds the possibility of adding a unique angle to ongoing research within a gastroenterology division, especially in collaboration with others. For example, during my fellowship training I was able to focus on histological changes in pancreatic islets of patients with pancreatic cancer that develop diabetes, compared with those that do not, in collaboration with a pathologist who focused on studying islet pathology and under the guidance of my mentor, Dr. Suresh Chari, a medical pancreatologist.2 I was also part of other studies within the GI division with other medical pancreatologists, such as Dr. Santhi Vege and Dr. Shounak Majumder, who have continued to serve as career and research mentors.3 Collaborative, multicenter studies on pancreatic disease are also conducted by CAPER, the organization mentioned above. A list of potential collaborations for the fellow interested

in medical pancreatology is provided in Figure 3.

Marketing considerations for the gastroenterology division

Having a medical pancreatologist in the team is not only attractive for referring physicians within an institution but is often a great asset from a marketing standpoint, especially for tertiary care academic centers and large community practices with a broad referral base. Given that there are a limited number of medical pancreatologists in the country, having one as part of the faculty can certainly provide a competitive edge to that center within the area, especially with an ever-increasing preference of patients for hyperspecialized care.

How to develop a career in medical pancreatology

Gastroenterology fellows often start their fellowships “undifferentiated” and try to get exposed to a wide variety of GI pathology, either through general GI clinics or as part of subspecialized clinics, as they attempt to decide how they want their careers to look down the line. Similar to other subspecialities, if a trainee has already decided to pursue medical pancreatology (as happened in my case), they should strongly consider ranking programs with available opportunities for research/clinic in medical pancreatology and ideally undergo an additional year of training. Fellows who decide during the course of their fellowship that they want to pursue a career in medical pancreatology should consider applying for a 4th year in the subject to not only obtain further training in the field but to also conduct research in the area and become more “marketable” as a person that could start a medical pancreatology program at their future academic or community position. Trainees interested in medical pancreatology should try to focus their time on long-term, clinical management of patients with pancreatic disorders, engaging a multidisciplinary team composed of interventional endoscopists, pancreatic surgeons, transplant surgeons (if total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation is available), radiology, addiction medicine (if available), endocrinology, and pathology. The list of places that offer a 4th year in medical pancreatology is increasing every year, and as of the writing of this article there are six programs that have this opportunity, which include:

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Penn.

The CAPER website is also a great resource for education as well as for identifying potential medical pancreatology programs.

In summary, medical pancreatology is an evolving and rapidly growing career path for gastroenterology fellows interested in providing care to patients with pancreatic disease in close collaboration with multiple other subspecialties, especially therapeutic endoscopy and pancreatic surgery. The field is also ripe for fellows interested in clinical, translational, and basic science research related to pancreatic disorders.

Dr. Nagpal is assistant professor of medicine, director, pancreas clinic, University of Chicago. He had no conflicts to disclose.

References

1. Feldman M et al. “Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease,” 11th ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2021).

2. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2020 Jul;20(5):929-35.

3. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2019 Mar;19(2):290-5.

Although described by the Greek physician Herophilos around 300 B.C., it was not until the 19th century that enzymes began to be isolated from pancreatic secretions and their digestive action described, and not until early in the 20th century that Banting, Macleod, and Best received the Nobel prize for purifying insulin from the pancreata of dogs. For centuries in between, the pancreas was considered to be just a ‘beautiful piece of flesh’ (kallikreas), the main role of which was to protect the blood vessels in the abdomen and to serve as a cushion to the stomach.1 Certainly, the pancreas has come a long way since then but, like most other organs in the body, is oft ignored until it develops issues.

Like many other disorders in gastroenterology, pancreatic disorders were historically approached as mechanical or “plumbing” issues. As modern technology and innovation percolated through the world of endoscopy, a wide array of state-of-the-art tools were devised. Availability of newer “toys” and development of newer techniques also means that an ever-increasing curriculum has been squeezed into a generally single year of therapeutic endoscopy training, such that trainees can no longer limit themselves to learning only endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or intervening on pancreatic disease alone. Modern, subspecialized approaches to disease and economic considerations often dictate that the therapeutic endoscopist of today must perform a wide range of procedures besides ERCP and EUS, such as advanced resection using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), endoscopic bariatric procedures, and newer techniques and acronyms that continue to evolve on a regular basis. This leaves the therapeutic endoscopist with little time for outpatient management of many patients that don’t need interventional procedures but are often very complex and need ongoing, long-term follow-up. In addition, any clinic slots available for interventional endoscopists may be utilized by patients coming in to discuss complex procedures or for postprocedure follow-up. Endoscopic management is not the definitive treatment for most pancreatic disorders. In fact, as our knowledge of pancreatic disease has continued to evolve, endoscopic intervention is now required in a minority of cases.

Role of the medical pancreatologist

Patient Care

As part of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary team that also includes an interventional gastroenterologist, pancreatic surgeon, transplant surgeon (in centers offering islet autotransplantation with total pancreatectomy), radiology, endocrinology, and GI pathologist, the medical pancreatologist helps lead the care of patients with pancreatic disorders, such as pancreatic cysts, acute and chronic pancreatitis (especially in cases where there is no role for active endoscopic intervention), autoimmune pancreatitis, indeterminate pancreatic masses, as well as screens high-risk patients for pancreatic cancer in conjunction with a genetic counselor. The medical pancreatologist often also serves as a bridge between various members of a large multidisciplinary team that, formally in the form of conferences or informally, discusses the management of complex patients, with each member available to help the other based on the patient’s most immediate clinical need at that time. A schematic showing how the medical pancreatologist collaborates with the therapeutic endoscopist is provided in Figure 1.

Uzma Siddiqui, MD, director for the Center for Endoscopic Research and Technology (CERT) at the University of Chicago said, “The management of pancreatic diseases is often challenging. Surgeons and endoscopists can offer some treatments that focus on one aspect or symptom, but the medical pancreatologist brings focus to the patient as a whole and helps organize care. It is only with everyone’s combined efforts and the added perspective of the medical pancreatologist that we can provide the best care for our shared patients.”

David Xin, MD, MPH, a medical pancreatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, added, “I am often asked what it means to be a medical pancreatologist. What do I do if not EUS and ERCP? I provide longitudinal care, coordinate multidisciplinary management, assess nutritional status, optimize quality of life, and manage pain. But perhaps most importantly, I make myself available for patients who seek understanding and sympathy regarding their complex disease. I became a medical pancreatologist because my mentors during training helped me recognize how rewarding this career would be.”

Insights from other medical pancreatologists and therapeutic endoscopists are provided in Figure 2.

Education

Having a dedicated medical pancreatology clinic has the potential to add a unique element to the training of gastroenterology fellows. In my own experience, besides fellows interested in medical pancreatology, even those interested in therapeutic endoscopy find it useful to rotate through the pancreas clinic and follow patients after or leading to their procedures, becoming comfortable with noninterventional pain management of patients with pancreatic disorders and risk stratification of pancreatic cystic lesions, and learning about the management of rare disorders such as autoimmune pancreatitis. Most importantly, this allows trainees to identify cases where endoscopic intervention may not offer definitive treatment for complex conditions such as pancreatic pain. Trainee-centered organizations such as the Collaborative Alliance for Pancreatic Education and Research (CAPER) enable trainees and young investigators to network with other physicians who are passionate about the pancreas and establish early research collaborations for current and future research endeavors that will help advance this field.

Research

Having a trained medical pancreatologist adds the possibility of adding a unique angle to ongoing research within a gastroenterology division, especially in collaboration with others. For example, during my fellowship training I was able to focus on histological changes in pancreatic islets of patients with pancreatic cancer that develop diabetes, compared with those that do not, in collaboration with a pathologist who focused on studying islet pathology and under the guidance of my mentor, Dr. Suresh Chari, a medical pancreatologist.2 I was also part of other studies within the GI division with other medical pancreatologists, such as Dr. Santhi Vege and Dr. Shounak Majumder, who have continued to serve as career and research mentors.3 Collaborative, multicenter studies on pancreatic disease are also conducted by CAPER, the organization mentioned above. A list of potential collaborations for the fellow interested

in medical pancreatology is provided in Figure 3.

Marketing considerations for the gastroenterology division

Having a medical pancreatologist in the team is not only attractive for referring physicians within an institution but is often a great asset from a marketing standpoint, especially for tertiary care academic centers and large community practices with a broad referral base. Given that there are a limited number of medical pancreatologists in the country, having one as part of the faculty can certainly provide a competitive edge to that center within the area, especially with an ever-increasing preference of patients for hyperspecialized care.

How to develop a career in medical pancreatology

Gastroenterology fellows often start their fellowships “undifferentiated” and try to get exposed to a wide variety of GI pathology, either through general GI clinics or as part of subspecialized clinics, as they attempt to decide how they want their careers to look down the line. Similar to other subspecialities, if a trainee has already decided to pursue medical pancreatology (as happened in my case), they should strongly consider ranking programs with available opportunities for research/clinic in medical pancreatology and ideally undergo an additional year of training. Fellows who decide during the course of their fellowship that they want to pursue a career in medical pancreatology should consider applying for a 4th year in the subject to not only obtain further training in the field but to also conduct research in the area and become more “marketable” as a person that could start a medical pancreatology program at their future academic or community position. Trainees interested in medical pancreatology should try to focus their time on long-term, clinical management of patients with pancreatic disorders, engaging a multidisciplinary team composed of interventional endoscopists, pancreatic surgeons, transplant surgeons (if total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation is available), radiology, addiction medicine (if available), endocrinology, and pathology. The list of places that offer a 4th year in medical pancreatology is increasing every year, and as of the writing of this article there are six programs that have this opportunity, which include:

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Penn.

The CAPER website is also a great resource for education as well as for identifying potential medical pancreatology programs.

In summary, medical pancreatology is an evolving and rapidly growing career path for gastroenterology fellows interested in providing care to patients with pancreatic disease in close collaboration with multiple other subspecialties, especially therapeutic endoscopy and pancreatic surgery. The field is also ripe for fellows interested in clinical, translational, and basic science research related to pancreatic disorders.

Dr. Nagpal is assistant professor of medicine, director, pancreas clinic, University of Chicago. He had no conflicts to disclose.

References

1. Feldman M et al. “Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease,” 11th ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2021).

2. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2020 Jul;20(5):929-35.

3. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2019 Mar;19(2):290-5.