User login

Prudent prescribing: Intelligent use of lab tests and other diagnostics

Evidence that atypical antipsychotics can increase risk of diabetes and heart disease is changing psychiatry’s approach to laboratory testing. The need for careful psychotropic prescribing—with intelligent use of diagnostic testing—has been emphasized by:

- four medical associations recommending that physicians screen and monitor patients taking atypical antipsychotics.

- FDA requiring antipsychotic labeling to describe increased risk of hyperglycemia and diabetes

- medical malpractice lawyers using television and Internet ads to seek clients who might have developed diabetes while taking antipsychotics.

This article offers information you need to detect emerging metabolic problems in patients taking atypical antipsychotics. We also discuss five other clinical situations where laboratory testing can help you:

- rule out organic illness

- perform therapeutic drug monitoring

- protect the heart when prescribing

- watch for clozapine’s side effects

- monitor for substance abuse.

Table 1

Lab testing with atypical antipsychotics*

Obtain baseline values before or as soon as possible after starting the antipsychotic:

Also note patient/family histories of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart disease† |

Repeat diabetes monitoring with fasting blood glucose and/or Hb A1c after 3 months of treatment, then at least annually. More-frequent monitoring (quarterly or monthly) may be indicated for patients with:

|

Consider switching to a medication with less weight-gain liability‡ for patients:

|

| Identify patients with metabolic syndrome,§ and ensure that they are carefully monitored by a primary care clinician. Check weight (with BMI) monthly for all patients for the first 6 months, then every 3 months thereafter |

| Repeat fasting lipid profile after 3 months, then every 2 years if serum lipids are normal or every 6 months in consultation with primary care clinician if LDL >130 mg/dL |

| * Individualize to particular patients’ needs. |

| † Patients with schizophrenia are at increased risk of coronary heart disease. |

| ‡ Weight gain liability = clozapine, olanzapine > risperidone, quetiapine > aripiprazole, ziprasidone |

| § Metabolic syndrome: A proinflammatory, prothrombotic state described by a cluster of abnormalities including abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, hypertension, and low HDL cholesterol. Can be exacerbated by atypical antipsychotics. |

| Source: Adapted from reference 3. |

DIABETES RISK

New monitoring standards. The American Psychiatric Association set a new standard of care by collaborating with the American Diabetes Association and others in recommending how to manage the potential for increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and lipid disorders when using atypical antipsychotics.2 The February 2004 APA/ADA report cites olanzapine and clozapine as the atypicals most likely to cause metabolic changes that increase heart disease risk. It also notes, however, that atypicals’ potential benefits to certain patients outweigh the risks.

Because of this report, psychiatrists who prescribe atypicals are now obligated to document baseline lab values and monitor patients for potential side effects (Table 1).1 We recommend that you also note patient race, as certain ethnic populations (such as African-American, Hispanic, Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander) are at elevated risk for diabetes.

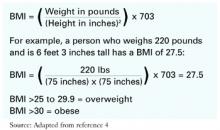

Determining BMI. When starting patients on atypical antipsychotics, calculate baseline body mass index (BMI) with the simple formula in Table 2 or by using BMI tables (see Related resources).4 Determine BMI before starting a new atypical antipsychotic, at every visit for the first 6 months, and then quarterly when the dosage is stable.

A BMI increase of 1 unit warrants medical intervention, including increased weight monitoring and placing the patient in a weight-management program and switching to another antipsychotic.3

Table 2 An easy formula to calculate body mass index (BMI)

The increasing incidence of diabetes in the U.S. population makes it difficult to assess the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and blood glucose abnormalities. Moreover, the risk of diabetes may be elevated in patients with schizophrenia, whether or not they are receiving medications. Diabetes and disturbed carbohydrate metabolism may be an integral component of schizophrenia itself.1

RULING OUT ORGANIC ILLNESS

A classic role of laboratory and diagnostic testing in psychiatry is to exclude organic illness that may be causing or exacerbating psychiatric symptoms. For a patient presenting with serious psychiatric symptoms, most sources recommend a standard battery of screening tests (Table 3).

Of course, the DSM-IV-TR “mental disorder due to a general medical condition” should be included in the differential diagnosis of any psychiatric presentation. DSM-IV-TR also calls for disease-specific tests, such as polysomnography in certain sleep disorders, CT for enlarged ventricles in schizophrenia, and electrolyte analysis in patients with anorexia nervosa.5 Order other tests as indicated, depending on patients’ medical conditions.

THERAPEUTIC DRUG MONITORING

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is used to optimize treatment with medications for which therapeutic blood levels for psychiatric disorders have been described.6 These include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, clozapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Keep in mind that “therapeutic” blood levels have been determined in “usual” patients in controlled clinical trials and may not apply to the many “unusual” patients who metabolize drugs differently because of genetic variation, age, and concomitant diseases, diet, or medications.7

Lithium. A therapeutic blood level is typically 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L, and—although the dosage must be individualized—900 to 1,200 mg/d in divided doses usually maintains this blood level. Lower levels between 0.4 mEq/L and 0.8 mEq/L have been described for the elderly.8

In uncomplicated cases, monitor lithium levels at least every 2 months during maintenance therapy. Draw blood immediately before a scheduled dose—such as 8 to 12 hours after the previous dose—when lithium concentrations are relatively stable.

Consider both clinical signs and serum levels when dosing, as patients unusually sensitive to lithium may exhibit toxic signs at <1.0 mEq/L. Elderly patients often respond to reduced dosages and may exhibit signs of toxicity—such as gastric upset and confusion—at serum levels most younger patients can tolerate.

Valproate. For seizure and bipolar disorders, the therapeutic blood level is 50 to 100 mcg/mL. Potential hematologic complications include thrombocytopenia; indigestion and nausea are common side effects. Typical practice is to obtain levels weekly for the first few weeks and then quarterly thereafter.

Carbamazepine. Plasma carbamazepine concentrations have not been correlated with response in bipolar disorder but are measured to prevent or identify toxicity. Dosages of 600 to 1,200 mg/d usually produce nontoxic levels of 4 to 12 mcg/mL. Carbamazepine interacts with many drugs that affect or are affected by hepatic metabolism. Blood dyscrasias including aplastic anemia are rare side effects.

Clozapine. Consensus is lacking on the optimal clozapine plasma level needed to achieve a therapeutic response. For some patients, it may be 200 to 350 ng/mL, which usually corresponds to 200 to 400 mg/d. Dosing must be individualized, however, because clozapine levels can vary almost 50-fold among patients taking the same dosage.9 Other studies10 and at least one recent textbook11 have reported therapeutic response most associated with clozapine levels >350 ng/mL, although adverse effects may be more likely at this higher dosage.

PROTECTING THE HEART

Before you prescribe any psychotropic with potential cardiotoxic effects, we recommend a baseline ECG for patients with cardiac risk factors, including:

- history of heart disease or ECG abnormalities

- history of syncope

- family history of sudden death before age 40, especially if both parents had sudden death

- history of prolonged QTc interval, such as congenital long QT syndrome.

Cardiotoxic effects such as QTc interval prolongation and torsades de pointes have been associated with thioridazine, mesoridazine, and pimozide. On ECG, a QTc interval >500 msec suggests an increased risk of potentially fatal arrhythmias. Do not prescribe medications associated with QTc interval prolongation to patients with this ECG finding.

Table 3

Screening tests most sources recommend for psychiatric practice

| Blood |

| Complete blood count (CBC) |

| Serum chemistry panel (“CHEM-20,” including liver function tests) |

| Lipid panels |

| Thyroid function tests (TFTs, TSH) |

| Screening tests for HIV, hepatitis C, syphilis |

| Serum B12 |

| Pregnancy tests in women of childbearing age and potential |

| Blood alcohol level in alcohol-intoxicated patient |

| Urine |

| Urine drug toxicology screen for substance abuse |

| Urinalysis |

| Cardiac |

| ECG |

| Imaging |

| Brain CT or MRI (preferred) if clinically indicated* |

| Chest radiography |

| Others |

| Serum medication levels† |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate or urine heavy metal screen, as indicated by medical history |

| Erythrocyte uroporphyrinogen-1-synthase |

| Urine uroporphyrins |

| EEG |

| Skull radiography |

| * Such as patient with disorientation, confusion, or abnormal neurologic exam |

| † When therapeutic/toxic blood levels are available for patient’s medications, such as theophylline, tricyclics, digoxin |

ECG is also indicated in patients who experience symptoms associated with a prolonged QT interval—such as dizziness or syncope—while taking antipsychotics. If ziprasidone is prescribed for patients with any of the risk factors described above, we recommend a baseline ECG before treatment begins, with a follow-up ECG if the patient experiences dizziness or syncope.4

Table 4

Screening tests for a patient beginning substance abuse treatment

|

WHEN USING CLOZAPINE

Clozapine is the only antipsychotic shown to improve neuroleptic-resistant symptoms12 and reduce suicidality13 in patients with schizophrenia. Unfortunately, clozapine’s potential side effects—including potentially life-threatening agranulocytosis—are legion, but careful monitoring with necessary lab testing can allow its benefits to outweigh the risks.

Agranulocytosis. Obtain white blood cell (WBC) count and differential at baseline, during treatment, and for 4 weeks after discontinuing clozapine, following the distribution program’s required schedule. Advise patients to immediately report flu-like complaints or signs that might suggest infection, such as lethargy, weakness, fever, sore throat, malaise, or mucous membrane ulceration.

Eosinophilia. In clinical trials, 1% of patients developed eosinophilia, which can be substantial in rare cases. If a differential count reveals a total eosinophil count >4,000/mm3 , stop clozapine therapy until the eosinophil count falls below 3,000/mm3 .

Myocarditis. Clozapine-treated patients are at much greater risk for developing myocarditis and of dying from it—especially during the first 6 weeks of therapy—than is the general population.3 Tachycardia can be a presenting sign.

Abnormal laboratory findings associated with clozapine-induced myocarditis may include increased WBC count, eosinophilia, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increased cardiac enzyme levels and plasma troponin. Because the mortality rate of clozapine-induced myocarditis approaches 40%, stop clozapine and refer the patient for medical evaluation as soon as possible when you suspect myocarditis.3

Endocrine and hepatic effects. Severe hyperglycemia, sometimes leading to ketoacidosis, can occur during clozapine treatment in patients without a history of hyperglycemia. Ketoacidosis symptoms include rapid breathing, nausea, vomiting, clouding of sensorium (even coma), weight loss, polyuria, polydipsia, and dehydration. Monitoring for blood glucose changes, as described in Table 1, is recommended with clozapine as with all other atypical antipsychotics.

Hepatitis during clozapine therapy has been reported in patients with baseline normal or preexisting abnormal liver function. After baseline liver function tests, we suggest follow-up LFTs:

- annually for patients with normal baseline values

- every 6 months for patients with minimally abnormal values

- every 3 months for patients with liver disease.

MONITORING SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Substance abuse is often associated with medical comorbidities that require laboratory workup and monitoring. These include overdose sequelae, sexual assault, cirrhosis, endocarditis, HIV infection, viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, and syphilis. Some testing is mandated by federal law for patients in methadone maintenance or opioid agonist therapy programs with methadone.

We recommend that new patients with substance abuse be screened for organic illness as described above, plus the workup in Table 4. Also gather a careful history for hepatitis, pancreatitis, diabetes, cirrhosis, unusual infections (cellulitis, endocarditis, atypical pneumonias, HIV), frequent hospitalizations, falls, injuries, and blackouts.

Obtain a blood alcohol level in alcohol-intoxicated patients and urine toxicology to screen for locally-available street drugs (typically marijuana, sedative/hypnotics, amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine).

Confer with your laboratory staff about the capabilities and sensitivities of their drug testing methods. Marijuana may be detected for 3 days to 4 weeks, depending on level of use. Cocaine can be detected for up to 2 to 4 days in urine.

- Rosse RB, Deutsch LH, Deutsch SI. Medical assessment and laboratory testing in psychiatry. In: Sadock B, Kaplan HI (eds). Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 6th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins 1995:601-19.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Body mass index tables. www.niddk.nih.gov/health/nutrit/pubs/statobes.htm#table.

- National Cholesterol Education Program. Guidelines for managing patients at risk for coronary heart disease. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/ncep/

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidelines on hyperglycemia associated with atypical antipsychotics [example]. www.fda.gov/medwatch/SAFETY/2004/Clozaril-deardoc.pdf

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, others

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Mesoridazine • Serentil

- Pimozide • Orap

- Thioridazine • Mellaril

- Valproate • Depakote, Depakene

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kohen D. Diabetes mellitus and schizophrenia: historical perspective. Br J Psychiatry 2004;47(Apr):S64-S66.

2. Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North merican Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus Development Conference on Antipsychotic Drugs and Obesity and Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:596-601.

3. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1334-49.

4. Work Group on Schizophrenia. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia (2nd ed). Am J Psychiatry 2004, 161:2(suppl). For BMI information related to this guideline, see http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/bmi/bmi-adult-formula.htm.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

6. Preskorn SH, Fast GA. Therapeutic drug monitoring for antidepressants: efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness. J Clin Psychiatry 1991;(52 suppl):23-33.

7. Preskorn SH. Why patients may not respond to usual recommended dosages: 3 variables to consider when prescribing antipsychotics [commentary]. Current Psychiatry 2004;3(8):38-43.

8. Price DG, Ghaemi SN. Lithium. In: Stern TA., Herman JB (eds). The Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation (2nd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004:355.

9. Kronig MH, Munne RA, Szymanski S, et al. Plasma clozapine levels and clinical response for treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152(2):179-82.

10. Schulte P. What is an adequate trial with clozapine? Therapeutic drug monitoring and time to response in treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003;42(7):607-18.

11. Henderson DC, Kunkel L, Goff DC. Antipsychotic drugs. In: Stern TA., Herman JB (eds). The Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation (2nd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004;338-9.

12. Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al. International Suicide Prevention Trial Study Group. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(1):82-91.

13. Meltzer HY. Suicide in schizophrenia: risk factors and clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 3):15-20.

Evidence that atypical antipsychotics can increase risk of diabetes and heart disease is changing psychiatry’s approach to laboratory testing. The need for careful psychotropic prescribing—with intelligent use of diagnostic testing—has been emphasized by:

- four medical associations recommending that physicians screen and monitor patients taking atypical antipsychotics.

- FDA requiring antipsychotic labeling to describe increased risk of hyperglycemia and diabetes

- medical malpractice lawyers using television and Internet ads to seek clients who might have developed diabetes while taking antipsychotics.

This article offers information you need to detect emerging metabolic problems in patients taking atypical antipsychotics. We also discuss five other clinical situations where laboratory testing can help you:

- rule out organic illness

- perform therapeutic drug monitoring

- protect the heart when prescribing

- watch for clozapine’s side effects

- monitor for substance abuse.

Table 1

Lab testing with atypical antipsychotics*

Obtain baseline values before or as soon as possible after starting the antipsychotic:

Also note patient/family histories of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart disease† |

Repeat diabetes monitoring with fasting blood glucose and/or Hb A1c after 3 months of treatment, then at least annually. More-frequent monitoring (quarterly or monthly) may be indicated for patients with:

|

Consider switching to a medication with less weight-gain liability‡ for patients:

|

| Identify patients with metabolic syndrome,§ and ensure that they are carefully monitored by a primary care clinician. Check weight (with BMI) monthly for all patients for the first 6 months, then every 3 months thereafter |

| Repeat fasting lipid profile after 3 months, then every 2 years if serum lipids are normal or every 6 months in consultation with primary care clinician if LDL >130 mg/dL |

| * Individualize to particular patients’ needs. |

| † Patients with schizophrenia are at increased risk of coronary heart disease. |

| ‡ Weight gain liability = clozapine, olanzapine > risperidone, quetiapine > aripiprazole, ziprasidone |

| § Metabolic syndrome: A proinflammatory, prothrombotic state described by a cluster of abnormalities including abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, hypertension, and low HDL cholesterol. Can be exacerbated by atypical antipsychotics. |

| Source: Adapted from reference 3. |

DIABETES RISK

New monitoring standards. The American Psychiatric Association set a new standard of care by collaborating with the American Diabetes Association and others in recommending how to manage the potential for increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and lipid disorders when using atypical antipsychotics.2 The February 2004 APA/ADA report cites olanzapine and clozapine as the atypicals most likely to cause metabolic changes that increase heart disease risk. It also notes, however, that atypicals’ potential benefits to certain patients outweigh the risks.

Because of this report, psychiatrists who prescribe atypicals are now obligated to document baseline lab values and monitor patients for potential side effects (Table 1).1 We recommend that you also note patient race, as certain ethnic populations (such as African-American, Hispanic, Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander) are at elevated risk for diabetes.

Determining BMI. When starting patients on atypical antipsychotics, calculate baseline body mass index (BMI) with the simple formula in Table 2 or by using BMI tables (see Related resources).4 Determine BMI before starting a new atypical antipsychotic, at every visit for the first 6 months, and then quarterly when the dosage is stable.

A BMI increase of 1 unit warrants medical intervention, including increased weight monitoring and placing the patient in a weight-management program and switching to another antipsychotic.3

Table 2 An easy formula to calculate body mass index (BMI)

The increasing incidence of diabetes in the U.S. population makes it difficult to assess the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and blood glucose abnormalities. Moreover, the risk of diabetes may be elevated in patients with schizophrenia, whether or not they are receiving medications. Diabetes and disturbed carbohydrate metabolism may be an integral component of schizophrenia itself.1

RULING OUT ORGANIC ILLNESS

A classic role of laboratory and diagnostic testing in psychiatry is to exclude organic illness that may be causing or exacerbating psychiatric symptoms. For a patient presenting with serious psychiatric symptoms, most sources recommend a standard battery of screening tests (Table 3).

Of course, the DSM-IV-TR “mental disorder due to a general medical condition” should be included in the differential diagnosis of any psychiatric presentation. DSM-IV-TR also calls for disease-specific tests, such as polysomnography in certain sleep disorders, CT for enlarged ventricles in schizophrenia, and electrolyte analysis in patients with anorexia nervosa.5 Order other tests as indicated, depending on patients’ medical conditions.

THERAPEUTIC DRUG MONITORING

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is used to optimize treatment with medications for which therapeutic blood levels for psychiatric disorders have been described.6 These include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, clozapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Keep in mind that “therapeutic” blood levels have been determined in “usual” patients in controlled clinical trials and may not apply to the many “unusual” patients who metabolize drugs differently because of genetic variation, age, and concomitant diseases, diet, or medications.7

Lithium. A therapeutic blood level is typically 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L, and—although the dosage must be individualized—900 to 1,200 mg/d in divided doses usually maintains this blood level. Lower levels between 0.4 mEq/L and 0.8 mEq/L have been described for the elderly.8

In uncomplicated cases, monitor lithium levels at least every 2 months during maintenance therapy. Draw blood immediately before a scheduled dose—such as 8 to 12 hours after the previous dose—when lithium concentrations are relatively stable.

Consider both clinical signs and serum levels when dosing, as patients unusually sensitive to lithium may exhibit toxic signs at <1.0 mEq/L. Elderly patients often respond to reduced dosages and may exhibit signs of toxicity—such as gastric upset and confusion—at serum levels most younger patients can tolerate.

Valproate. For seizure and bipolar disorders, the therapeutic blood level is 50 to 100 mcg/mL. Potential hematologic complications include thrombocytopenia; indigestion and nausea are common side effects. Typical practice is to obtain levels weekly for the first few weeks and then quarterly thereafter.

Carbamazepine. Plasma carbamazepine concentrations have not been correlated with response in bipolar disorder but are measured to prevent or identify toxicity. Dosages of 600 to 1,200 mg/d usually produce nontoxic levels of 4 to 12 mcg/mL. Carbamazepine interacts with many drugs that affect or are affected by hepatic metabolism. Blood dyscrasias including aplastic anemia are rare side effects.

Clozapine. Consensus is lacking on the optimal clozapine plasma level needed to achieve a therapeutic response. For some patients, it may be 200 to 350 ng/mL, which usually corresponds to 200 to 400 mg/d. Dosing must be individualized, however, because clozapine levels can vary almost 50-fold among patients taking the same dosage.9 Other studies10 and at least one recent textbook11 have reported therapeutic response most associated with clozapine levels >350 ng/mL, although adverse effects may be more likely at this higher dosage.

PROTECTING THE HEART

Before you prescribe any psychotropic with potential cardiotoxic effects, we recommend a baseline ECG for patients with cardiac risk factors, including:

- history of heart disease or ECG abnormalities

- history of syncope

- family history of sudden death before age 40, especially if both parents had sudden death

- history of prolonged QTc interval, such as congenital long QT syndrome.

Cardiotoxic effects such as QTc interval prolongation and torsades de pointes have been associated with thioridazine, mesoridazine, and pimozide. On ECG, a QTc interval >500 msec suggests an increased risk of potentially fatal arrhythmias. Do not prescribe medications associated with QTc interval prolongation to patients with this ECG finding.

Table 3

Screening tests most sources recommend for psychiatric practice

| Blood |

| Complete blood count (CBC) |

| Serum chemistry panel (“CHEM-20,” including liver function tests) |

| Lipid panels |

| Thyroid function tests (TFTs, TSH) |

| Screening tests for HIV, hepatitis C, syphilis |

| Serum B12 |

| Pregnancy tests in women of childbearing age and potential |

| Blood alcohol level in alcohol-intoxicated patient |

| Urine |

| Urine drug toxicology screen for substance abuse |

| Urinalysis |

| Cardiac |

| ECG |

| Imaging |

| Brain CT or MRI (preferred) if clinically indicated* |

| Chest radiography |

| Others |

| Serum medication levels† |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate or urine heavy metal screen, as indicated by medical history |

| Erythrocyte uroporphyrinogen-1-synthase |

| Urine uroporphyrins |

| EEG |

| Skull radiography |

| * Such as patient with disorientation, confusion, or abnormal neurologic exam |

| † When therapeutic/toxic blood levels are available for patient’s medications, such as theophylline, tricyclics, digoxin |

ECG is also indicated in patients who experience symptoms associated with a prolonged QT interval—such as dizziness or syncope—while taking antipsychotics. If ziprasidone is prescribed for patients with any of the risk factors described above, we recommend a baseline ECG before treatment begins, with a follow-up ECG if the patient experiences dizziness or syncope.4

Table 4

Screening tests for a patient beginning substance abuse treatment

|

WHEN USING CLOZAPINE

Clozapine is the only antipsychotic shown to improve neuroleptic-resistant symptoms12 and reduce suicidality13 in patients with schizophrenia. Unfortunately, clozapine’s potential side effects—including potentially life-threatening agranulocytosis—are legion, but careful monitoring with necessary lab testing can allow its benefits to outweigh the risks.

Agranulocytosis. Obtain white blood cell (WBC) count and differential at baseline, during treatment, and for 4 weeks after discontinuing clozapine, following the distribution program’s required schedule. Advise patients to immediately report flu-like complaints or signs that might suggest infection, such as lethargy, weakness, fever, sore throat, malaise, or mucous membrane ulceration.

Eosinophilia. In clinical trials, 1% of patients developed eosinophilia, which can be substantial in rare cases. If a differential count reveals a total eosinophil count >4,000/mm3 , stop clozapine therapy until the eosinophil count falls below 3,000/mm3 .

Myocarditis. Clozapine-treated patients are at much greater risk for developing myocarditis and of dying from it—especially during the first 6 weeks of therapy—than is the general population.3 Tachycardia can be a presenting sign.

Abnormal laboratory findings associated with clozapine-induced myocarditis may include increased WBC count, eosinophilia, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increased cardiac enzyme levels and plasma troponin. Because the mortality rate of clozapine-induced myocarditis approaches 40%, stop clozapine and refer the patient for medical evaluation as soon as possible when you suspect myocarditis.3

Endocrine and hepatic effects. Severe hyperglycemia, sometimes leading to ketoacidosis, can occur during clozapine treatment in patients without a history of hyperglycemia. Ketoacidosis symptoms include rapid breathing, nausea, vomiting, clouding of sensorium (even coma), weight loss, polyuria, polydipsia, and dehydration. Monitoring for blood glucose changes, as described in Table 1, is recommended with clozapine as with all other atypical antipsychotics.

Hepatitis during clozapine therapy has been reported in patients with baseline normal or preexisting abnormal liver function. After baseline liver function tests, we suggest follow-up LFTs:

- annually for patients with normal baseline values

- every 6 months for patients with minimally abnormal values

- every 3 months for patients with liver disease.

MONITORING SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Substance abuse is often associated with medical comorbidities that require laboratory workup and monitoring. These include overdose sequelae, sexual assault, cirrhosis, endocarditis, HIV infection, viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, and syphilis. Some testing is mandated by federal law for patients in methadone maintenance or opioid agonist therapy programs with methadone.

We recommend that new patients with substance abuse be screened for organic illness as described above, plus the workup in Table 4. Also gather a careful history for hepatitis, pancreatitis, diabetes, cirrhosis, unusual infections (cellulitis, endocarditis, atypical pneumonias, HIV), frequent hospitalizations, falls, injuries, and blackouts.

Obtain a blood alcohol level in alcohol-intoxicated patients and urine toxicology to screen for locally-available street drugs (typically marijuana, sedative/hypnotics, amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine).

Confer with your laboratory staff about the capabilities and sensitivities of their drug testing methods. Marijuana may be detected for 3 days to 4 weeks, depending on level of use. Cocaine can be detected for up to 2 to 4 days in urine.

- Rosse RB, Deutsch LH, Deutsch SI. Medical assessment and laboratory testing in psychiatry. In: Sadock B, Kaplan HI (eds). Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 6th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins 1995:601-19.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Body mass index tables. www.niddk.nih.gov/health/nutrit/pubs/statobes.htm#table.

- National Cholesterol Education Program. Guidelines for managing patients at risk for coronary heart disease. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/ncep/

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidelines on hyperglycemia associated with atypical antipsychotics [example]. www.fda.gov/medwatch/SAFETY/2004/Clozaril-deardoc.pdf

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, others

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Mesoridazine • Serentil

- Pimozide • Orap

- Thioridazine • Mellaril

- Valproate • Depakote, Depakene

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Evidence that atypical antipsychotics can increase risk of diabetes and heart disease is changing psychiatry’s approach to laboratory testing. The need for careful psychotropic prescribing—with intelligent use of diagnostic testing—has been emphasized by:

- four medical associations recommending that physicians screen and monitor patients taking atypical antipsychotics.

- FDA requiring antipsychotic labeling to describe increased risk of hyperglycemia and diabetes

- medical malpractice lawyers using television and Internet ads to seek clients who might have developed diabetes while taking antipsychotics.

This article offers information you need to detect emerging metabolic problems in patients taking atypical antipsychotics. We also discuss five other clinical situations where laboratory testing can help you:

- rule out organic illness

- perform therapeutic drug monitoring

- protect the heart when prescribing

- watch for clozapine’s side effects

- monitor for substance abuse.

Table 1

Lab testing with atypical antipsychotics*

Obtain baseline values before or as soon as possible after starting the antipsychotic:

Also note patient/family histories of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart disease† |

Repeat diabetes monitoring with fasting blood glucose and/or Hb A1c after 3 months of treatment, then at least annually. More-frequent monitoring (quarterly or monthly) may be indicated for patients with:

|

Consider switching to a medication with less weight-gain liability‡ for patients:

|

| Identify patients with metabolic syndrome,§ and ensure that they are carefully monitored by a primary care clinician. Check weight (with BMI) monthly for all patients for the first 6 months, then every 3 months thereafter |

| Repeat fasting lipid profile after 3 months, then every 2 years if serum lipids are normal or every 6 months in consultation with primary care clinician if LDL >130 mg/dL |

| * Individualize to particular patients’ needs. |

| † Patients with schizophrenia are at increased risk of coronary heart disease. |

| ‡ Weight gain liability = clozapine, olanzapine > risperidone, quetiapine > aripiprazole, ziprasidone |

| § Metabolic syndrome: A proinflammatory, prothrombotic state described by a cluster of abnormalities including abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, hypertension, and low HDL cholesterol. Can be exacerbated by atypical antipsychotics. |

| Source: Adapted from reference 3. |

DIABETES RISK

New monitoring standards. The American Psychiatric Association set a new standard of care by collaborating with the American Diabetes Association and others in recommending how to manage the potential for increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and lipid disorders when using atypical antipsychotics.2 The February 2004 APA/ADA report cites olanzapine and clozapine as the atypicals most likely to cause metabolic changes that increase heart disease risk. It also notes, however, that atypicals’ potential benefits to certain patients outweigh the risks.

Because of this report, psychiatrists who prescribe atypicals are now obligated to document baseline lab values and monitor patients for potential side effects (Table 1).1 We recommend that you also note patient race, as certain ethnic populations (such as African-American, Hispanic, Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander) are at elevated risk for diabetes.

Determining BMI. When starting patients on atypical antipsychotics, calculate baseline body mass index (BMI) with the simple formula in Table 2 or by using BMI tables (see Related resources).4 Determine BMI before starting a new atypical antipsychotic, at every visit for the first 6 months, and then quarterly when the dosage is stable.

A BMI increase of 1 unit warrants medical intervention, including increased weight monitoring and placing the patient in a weight-management program and switching to another antipsychotic.3

Table 2 An easy formula to calculate body mass index (BMI)

The increasing incidence of diabetes in the U.S. population makes it difficult to assess the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and blood glucose abnormalities. Moreover, the risk of diabetes may be elevated in patients with schizophrenia, whether or not they are receiving medications. Diabetes and disturbed carbohydrate metabolism may be an integral component of schizophrenia itself.1

RULING OUT ORGANIC ILLNESS

A classic role of laboratory and diagnostic testing in psychiatry is to exclude organic illness that may be causing or exacerbating psychiatric symptoms. For a patient presenting with serious psychiatric symptoms, most sources recommend a standard battery of screening tests (Table 3).

Of course, the DSM-IV-TR “mental disorder due to a general medical condition” should be included in the differential diagnosis of any psychiatric presentation. DSM-IV-TR also calls for disease-specific tests, such as polysomnography in certain sleep disorders, CT for enlarged ventricles in schizophrenia, and electrolyte analysis in patients with anorexia nervosa.5 Order other tests as indicated, depending on patients’ medical conditions.

THERAPEUTIC DRUG MONITORING

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is used to optimize treatment with medications for which therapeutic blood levels for psychiatric disorders have been described.6 These include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, clozapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Keep in mind that “therapeutic” blood levels have been determined in “usual” patients in controlled clinical trials and may not apply to the many “unusual” patients who metabolize drugs differently because of genetic variation, age, and concomitant diseases, diet, or medications.7

Lithium. A therapeutic blood level is typically 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L, and—although the dosage must be individualized—900 to 1,200 mg/d in divided doses usually maintains this blood level. Lower levels between 0.4 mEq/L and 0.8 mEq/L have been described for the elderly.8

In uncomplicated cases, monitor lithium levels at least every 2 months during maintenance therapy. Draw blood immediately before a scheduled dose—such as 8 to 12 hours after the previous dose—when lithium concentrations are relatively stable.

Consider both clinical signs and serum levels when dosing, as patients unusually sensitive to lithium may exhibit toxic signs at <1.0 mEq/L. Elderly patients often respond to reduced dosages and may exhibit signs of toxicity—such as gastric upset and confusion—at serum levels most younger patients can tolerate.

Valproate. For seizure and bipolar disorders, the therapeutic blood level is 50 to 100 mcg/mL. Potential hematologic complications include thrombocytopenia; indigestion and nausea are common side effects. Typical practice is to obtain levels weekly for the first few weeks and then quarterly thereafter.

Carbamazepine. Plasma carbamazepine concentrations have not been correlated with response in bipolar disorder but are measured to prevent or identify toxicity. Dosages of 600 to 1,200 mg/d usually produce nontoxic levels of 4 to 12 mcg/mL. Carbamazepine interacts with many drugs that affect or are affected by hepatic metabolism. Blood dyscrasias including aplastic anemia are rare side effects.

Clozapine. Consensus is lacking on the optimal clozapine plasma level needed to achieve a therapeutic response. For some patients, it may be 200 to 350 ng/mL, which usually corresponds to 200 to 400 mg/d. Dosing must be individualized, however, because clozapine levels can vary almost 50-fold among patients taking the same dosage.9 Other studies10 and at least one recent textbook11 have reported therapeutic response most associated with clozapine levels >350 ng/mL, although adverse effects may be more likely at this higher dosage.

PROTECTING THE HEART

Before you prescribe any psychotropic with potential cardiotoxic effects, we recommend a baseline ECG for patients with cardiac risk factors, including:

- history of heart disease or ECG abnormalities

- history of syncope

- family history of sudden death before age 40, especially if both parents had sudden death

- history of prolonged QTc interval, such as congenital long QT syndrome.

Cardiotoxic effects such as QTc interval prolongation and torsades de pointes have been associated with thioridazine, mesoridazine, and pimozide. On ECG, a QTc interval >500 msec suggests an increased risk of potentially fatal arrhythmias. Do not prescribe medications associated with QTc interval prolongation to patients with this ECG finding.

Table 3

Screening tests most sources recommend for psychiatric practice

| Blood |

| Complete blood count (CBC) |

| Serum chemistry panel (“CHEM-20,” including liver function tests) |

| Lipid panels |

| Thyroid function tests (TFTs, TSH) |

| Screening tests for HIV, hepatitis C, syphilis |

| Serum B12 |

| Pregnancy tests in women of childbearing age and potential |

| Blood alcohol level in alcohol-intoxicated patient |

| Urine |

| Urine drug toxicology screen for substance abuse |

| Urinalysis |

| Cardiac |

| ECG |

| Imaging |

| Brain CT or MRI (preferred) if clinically indicated* |

| Chest radiography |

| Others |

| Serum medication levels† |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate or urine heavy metal screen, as indicated by medical history |

| Erythrocyte uroporphyrinogen-1-synthase |

| Urine uroporphyrins |

| EEG |

| Skull radiography |

| * Such as patient with disorientation, confusion, or abnormal neurologic exam |

| † When therapeutic/toxic blood levels are available for patient’s medications, such as theophylline, tricyclics, digoxin |

ECG is also indicated in patients who experience symptoms associated with a prolonged QT interval—such as dizziness or syncope—while taking antipsychotics. If ziprasidone is prescribed for patients with any of the risk factors described above, we recommend a baseline ECG before treatment begins, with a follow-up ECG if the patient experiences dizziness or syncope.4

Table 4

Screening tests for a patient beginning substance abuse treatment

|

WHEN USING CLOZAPINE

Clozapine is the only antipsychotic shown to improve neuroleptic-resistant symptoms12 and reduce suicidality13 in patients with schizophrenia. Unfortunately, clozapine’s potential side effects—including potentially life-threatening agranulocytosis—are legion, but careful monitoring with necessary lab testing can allow its benefits to outweigh the risks.

Agranulocytosis. Obtain white blood cell (WBC) count and differential at baseline, during treatment, and for 4 weeks after discontinuing clozapine, following the distribution program’s required schedule. Advise patients to immediately report flu-like complaints or signs that might suggest infection, such as lethargy, weakness, fever, sore throat, malaise, or mucous membrane ulceration.

Eosinophilia. In clinical trials, 1% of patients developed eosinophilia, which can be substantial in rare cases. If a differential count reveals a total eosinophil count >4,000/mm3 , stop clozapine therapy until the eosinophil count falls below 3,000/mm3 .

Myocarditis. Clozapine-treated patients are at much greater risk for developing myocarditis and of dying from it—especially during the first 6 weeks of therapy—than is the general population.3 Tachycardia can be a presenting sign.

Abnormal laboratory findings associated with clozapine-induced myocarditis may include increased WBC count, eosinophilia, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increased cardiac enzyme levels and plasma troponin. Because the mortality rate of clozapine-induced myocarditis approaches 40%, stop clozapine and refer the patient for medical evaluation as soon as possible when you suspect myocarditis.3

Endocrine and hepatic effects. Severe hyperglycemia, sometimes leading to ketoacidosis, can occur during clozapine treatment in patients without a history of hyperglycemia. Ketoacidosis symptoms include rapid breathing, nausea, vomiting, clouding of sensorium (even coma), weight loss, polyuria, polydipsia, and dehydration. Monitoring for blood glucose changes, as described in Table 1, is recommended with clozapine as with all other atypical antipsychotics.

Hepatitis during clozapine therapy has been reported in patients with baseline normal or preexisting abnormal liver function. After baseline liver function tests, we suggest follow-up LFTs:

- annually for patients with normal baseline values

- every 6 months for patients with minimally abnormal values

- every 3 months for patients with liver disease.

MONITORING SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Substance abuse is often associated with medical comorbidities that require laboratory workup and monitoring. These include overdose sequelae, sexual assault, cirrhosis, endocarditis, HIV infection, viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, and syphilis. Some testing is mandated by federal law for patients in methadone maintenance or opioid agonist therapy programs with methadone.

We recommend that new patients with substance abuse be screened for organic illness as described above, plus the workup in Table 4. Also gather a careful history for hepatitis, pancreatitis, diabetes, cirrhosis, unusual infections (cellulitis, endocarditis, atypical pneumonias, HIV), frequent hospitalizations, falls, injuries, and blackouts.

Obtain a blood alcohol level in alcohol-intoxicated patients and urine toxicology to screen for locally-available street drugs (typically marijuana, sedative/hypnotics, amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine).

Confer with your laboratory staff about the capabilities and sensitivities of their drug testing methods. Marijuana may be detected for 3 days to 4 weeks, depending on level of use. Cocaine can be detected for up to 2 to 4 days in urine.

- Rosse RB, Deutsch LH, Deutsch SI. Medical assessment and laboratory testing in psychiatry. In: Sadock B, Kaplan HI (eds). Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 6th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins 1995:601-19.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Body mass index tables. www.niddk.nih.gov/health/nutrit/pubs/statobes.htm#table.

- National Cholesterol Education Program. Guidelines for managing patients at risk for coronary heart disease. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/ncep/

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidelines on hyperglycemia associated with atypical antipsychotics [example]. www.fda.gov/medwatch/SAFETY/2004/Clozaril-deardoc.pdf

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, others

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Mesoridazine • Serentil

- Pimozide • Orap

- Thioridazine • Mellaril

- Valproate • Depakote, Depakene

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kohen D. Diabetes mellitus and schizophrenia: historical perspective. Br J Psychiatry 2004;47(Apr):S64-S66.

2. Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North merican Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus Development Conference on Antipsychotic Drugs and Obesity and Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:596-601.

3. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1334-49.

4. Work Group on Schizophrenia. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia (2nd ed). Am J Psychiatry 2004, 161:2(suppl). For BMI information related to this guideline, see http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/bmi/bmi-adult-formula.htm.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

6. Preskorn SH, Fast GA. Therapeutic drug monitoring for antidepressants: efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness. J Clin Psychiatry 1991;(52 suppl):23-33.

7. Preskorn SH. Why patients may not respond to usual recommended dosages: 3 variables to consider when prescribing antipsychotics [commentary]. Current Psychiatry 2004;3(8):38-43.

8. Price DG, Ghaemi SN. Lithium. In: Stern TA., Herman JB (eds). The Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation (2nd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004:355.

9. Kronig MH, Munne RA, Szymanski S, et al. Plasma clozapine levels and clinical response for treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152(2):179-82.

10. Schulte P. What is an adequate trial with clozapine? Therapeutic drug monitoring and time to response in treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003;42(7):607-18.

11. Henderson DC, Kunkel L, Goff DC. Antipsychotic drugs. In: Stern TA., Herman JB (eds). The Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation (2nd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004;338-9.

12. Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al. International Suicide Prevention Trial Study Group. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(1):82-91.

13. Meltzer HY. Suicide in schizophrenia: risk factors and clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 3):15-20.

1. Kohen D. Diabetes mellitus and schizophrenia: historical perspective. Br J Psychiatry 2004;47(Apr):S64-S66.

2. Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North merican Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus Development Conference on Antipsychotic Drugs and Obesity and Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:596-601.

3. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1334-49.

4. Work Group on Schizophrenia. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia (2nd ed). Am J Psychiatry 2004, 161:2(suppl). For BMI information related to this guideline, see http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/bmi/bmi-adult-formula.htm.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

6. Preskorn SH, Fast GA. Therapeutic drug monitoring for antidepressants: efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness. J Clin Psychiatry 1991;(52 suppl):23-33.

7. Preskorn SH. Why patients may not respond to usual recommended dosages: 3 variables to consider when prescribing antipsychotics [commentary]. Current Psychiatry 2004;3(8):38-43.

8. Price DG, Ghaemi SN. Lithium. In: Stern TA., Herman JB (eds). The Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation (2nd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004:355.

9. Kronig MH, Munne RA, Szymanski S, et al. Plasma clozapine levels and clinical response for treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152(2):179-82.

10. Schulte P. What is an adequate trial with clozapine? Therapeutic drug monitoring and time to response in treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003;42(7):607-18.

11. Henderson DC, Kunkel L, Goff DC. Antipsychotic drugs. In: Stern TA., Herman JB (eds). The Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation (2nd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004;338-9.

12. Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al. International Suicide Prevention Trial Study Group. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(1):82-91.

13. Meltzer HY. Suicide in schizophrenia: risk factors and clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 3):15-20.