User login

Education: Hospitalists Add Value to Formal and Informal Learning Processes

Type a medical condition or term into a search engine and watch what happens. A search on the words “diabetes” yields more than 13 million Web pages, and “pneumonia” produces another 1.65 million. In 1998, the Internet hosted approximately 5000 health-related Web sites; two years later that number quadrupled (1). Between 30,000 and 45,000 medical articles on various drug therapies are published annually. The Patent and Trademark Office issued between 2000 and 4200 drug patents each year between 1979 and 1989 (2). The National Library of Medicine reports that it adds more than 2000 journal article citations to its MEDLINE database on a daily basis. In 2003, more than 460,000 citations were entered.

Deciphering and applying this myriad of changing information is a critical activity in the medical field. Without disseminating new knowledge through ongoing education, medical practices and procedures would become outdated, and uninformed medical professionals and patients would continue to operate under misinformation that might be detrimental to health or worse.

Hospitalists as Inpatient Experts

In an inpatient setting, hospitalists are uniquely qualified to play the role of educator. They analyze and interpret a wide range of medical information to treat their patients and provide updated information to patients and their families, residents, interns, nursing staff, other health care professionals, and hospital administrators. The hospitalist can be viewed as the “hub” of educational activities in the inpatient environment, absorbing, synthesizing, and disseminating information. They are “inpatient experts” in the following five spheres of knowledge:

- patient management

- clinical knowledge

- clinical skills

- health care industry issues

- research and management/leadership (3)

Hospitalists are uniquely qualified in the sphere of patient management, efficiently and effectively guiding the patient through the mazelike inpatient environment. Most hospitalists are quite familiar with critical hospital functions and activities, including treatment in the emergency department, the admissions process, bedside care on the medical floor, treatment in the intensive care unit, and the discharge process. Hospitalists, because they understand “how to get things done” by ancillary departments, including diagnostic and therapeutic services, often find themselves as conductors of inpatient care. Many hospitalists have developed unique proficiency in co-managing surgical cases due to expertise in peri-operative evaluation and care. Hospitalists are recognized as inpatient team leaders, facilitating and coordinating a range of support services needed to treat the patient, including nursing, case management, pharmacy, occupational/physical therapy, and social work. Hospitalists must also be effective in managing relationships with health care personnel external to the inpatient environment, including community physicians, homecare providers, extended care facilities, and visiting nurse services. Finally, hospitalists are oaen well informed about hospital processes, procedures, rules, regulations, and information systems.

As inpatient generalists, hospitalists continually treat the most common reasons for admission and have exceptional clinical knowledge of these conditions. These conditions include pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), congestive heart failure (CHF), diabetes, end-of-life care, and other medical diagnoses. Since they treat many elderly patients, hospitalists are considered experts in managing patients with multiple co-morbidities. A related area of expertise is clinical guidelines/pathways, quality of care metrics, and practice standards. Since they spend nearly all of their time treating inpatients, hospitalists develop extraordinary familiarity with the clinical rules and tools supporting the patient care process.

In addition to clinical knowledge, hospitalists have the experience and expertise to teach inpatient clinical skills. These skills include diagnosis, physical examination, discharge planning, medical chart recording, family meeting coordination, and oversight. Also, most hospitalists are familiar with a range of technical procedures, including insertion of central lines and arterial lines, lumbar puncture, arthrocentesis, paracentesis, and thoracentesis.

Hospitalists often are the most knowledgeable inpatient clinicians with regard to a wide range of health care industry issues. These include comprehension of the payer/insurance regulations regarding medication formularies, utilization review requirements, and other care policies. Their expertise may extend to knowledge of state and federal regulations, public health initiatives, and recently enacted or pending health care legislation. Finally, hospitalists also are often conversant in the field of health care economics, especially regarding the financial impact on hospitals of reimbursement policies, legislative initiatives, technology, etc.

The fifth sphere of hospitalist expertise combines several knowledge domains. Individual hospitalists have specialized expertise in particular fields related to hospital medicine. Some hospitalists, mostly affiliated with academic institutions, are researchers who may develop research protocols, gather data, perform statistical analyses, and write papers that may potentially become the basis of improved patient care. Other hospitalists are exceptionally experienced in management/leadership. A hospitalist may be highly qualified to manage projects (e.g., computer-based physician order entry systems, throughput initiatives, etc.),or a hospitalist could be a strategic thinker who is viewed as a key clinical member of the hospital’s management team.

As a growing specialty, hospitalists have established a proficiency in a range of disciplines and intellectual domains. They are well positioned to assume the role of educator in the hospital environment. Given the exceptional knowledge and skills needed to be a hospitalist, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) is pursing an effort to standardize education and lend greater credibility to the hospitalist profession. The “core curriculum” project is currently formalizing training that will provide a solid foundation for effective clinical practice in the field of hospital medicine.

Dual Educational Tracks

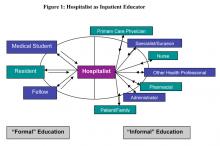

As depicted in Figure 1 below, medical education activity and the ways in which knowledge is imparted fall into two categories: formal and informal. Although some overlap may occur, there are distinct characteristics attributable to both classifications.

“Formal”

Formal education refers to the traditional “teacher-learner” roles in medicine. The learner can be a medical student, resident, or fellow. Education is typically transmitted from teacher to learner (as depicted in the diagram by a solid line), with some reciprocal feedback from the learner to the teacher (dotted line). It should be noted that as the importance and value of hospital medicine programs gain recognition, fellowship programs focusing on this specialty have been established. As of August 2004, eight active hospital medicine fellowship programs exist in the United States: three in California, two in Minnesota, and one each in Ohio, Illinois, and Texas. There are also pediatric hospital medicine fellowship programs in Boston, Washington DC, Houston, and San Diego. Each program enrolls one or two fellows annually (4).

Formal education can take place in both academic medical centers and community hospitals. By definition, academic medical centers provide supervised practical training for medical students, student nurses, and/or other health care professionals, as well as residents and fellows. In many academic medical centers throughout the country, hospitalists are emerging as core teachers of inpatient medicine. A prime example is the University of California, San Francisco. In 2002, 15 faculty hospitalists served as staff for approximately two-thirds of ward-attending months, as well as all medical consults (5).

By the same token, community hospitals that have residency programs also incorporate education to some degree into their daily operations. Today, medical education places a significant burden on residents and on the professionals charged with teaching students to absorb and understand vast amounts of science and medical information. On July 1, 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) revised the regulations governing the number of resident duty hours. These changes have forced residency programs to find viable options for imparting the required knowledge and hands-on experience to residents in fewer hours. Many consider hospitalists, by virtue of their “superior clinical and educational skills,” as representative of “the solution to the residency work duty problem.” In addition to providing excellence in teaching, hospitalists, known for their “superior clinical and educational skills,” may lead the way in creating and leading a clinical research agenda, which presents as the ultimate pedagogical experience (6).

In 2002, ACGME required six general competencies to be incorporated into residency curriculum and evaluation: patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. Hospitalists, because their practice already incorporates many aspects of these competencies, may be more effective at teaching these concepts to residents.

In the formal capacity of teacher, hospitalists can participate in attending/teaching rounds and in didactic patient-specific sessions presented in a case-based format, which provides residents with basic knowledge. As teaching supervisors, they can oversee the full range of clinical processes and procedures from the admission stage to post-discharge. Hospitalist teachers can also serve as mentors, providing a role model to residents who may be searching for direction regarding future plans. Through career counseling, hospitalists may steer learners into appropriate areas of study and training. Table 1 summarizes a series of research studies that document the positive impact hospitalists have achieved as educators in the academic environment.

Hospitalists may also have formal responsibility for developing curricula for learners in the academic environment. Whether the focus is on teaching medical students, residents, or hospitalist fellows, there is a need to determine the topics and material to be covered, incorporate them into a cogent curriculum, and update regularly to reflect the changing standards of care.

“Informal”

Informal education can be viewed as an exchange of information among stakeholders in the health care industry attempting to improve outcomes. Figure 1 depicts this as a two-way information exchange (solid arrows in both directions). As hospitalists impart knowledge to primary care physicians (PCPs), specialists/surgeons, other health care professionals (including nurses and pharmacists), patients, families, and hospital administrators, they reap benefits as well. These stakeholders stand to profit from the knowledge hospitalists can impart in daily interactions within the hospital and in less formal settings.

By working together with nurses, emergency room physicians, medical specialists, and PCPs, hospitalists can help achieve efficient and effective processes of care. The use of available software programs enables health care professionals to cooperatively exchange reliable information regarding patient management. Ongoing conversations regarding diagnoses, treatment, medications, and procedures serve to keep each member of the team educated and informed, thus ensuring more efficient delivery of care (12).

Alpesh Amin, MD, executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California, Irvine, and chair of SHM’s Education Committee, points out that hospitalists frequently have opportunities to act as educators during case-by-case interactions with PCPs and other health care providers. “Every time you talk to a doctor about admitting or discharging a patient, it’s an opportunity to educate,” he says. In addition, “the hospitalist can apply and/or develop critical pathways and algorithms to educate others.” In the course of managing care, criteria can be developed for previously unaddressed medical issues.

This same opportunity for education extends to the hospital floor where team building serves to enlighten each member of the group providing patient care. In a reciprocal environment, both hospitalists and their medical professional “teammates” benefit from each other’s knowledge. Amin points out that specialists typically focus on one condition, while hospitalists consider the entire patient. By openly receiving the specialist’s input and advice, processing it, and then applying it to the patient, the hospitalist can develop a comprehensive approach to disease management. By considering co-morbidities and long-term care, the health care team should base decisions on “patient-centered education (13).”

Hospitalists can initiate informal in-house educational outreach, such as informational programs about medical breakthroughs, new medications, explanations of existing medical legislation, and other relevant topics. These programs can enlighten nurses, case managers, pharmacists, and other health care professionals about issues important to managing patients and/or achieving quality outcomes. The format for these programs may be one-on-one interactions (either in-person or by telephone) relating to one specific patient; formal in-service lectures; “Lunch and Learns”; pharmaceutically funded drug- or-disease-management seminars; committee or departmental meetings, and/or random written communications (sent electronically or by interoffice mail) that incorporate history and physical findings, consultations, discharge summaries, or hard-copy articles (12).

Conclusion

Because they spend so much time in the hospital, hospitalists are experts on all aspects of inpatient care: clinical, administrative, patient flow, and health care industry issues. Published research shows that academic institutions that employ hospitalists will have more satisfied and better-educated students. Common sense suggests that nurses and other stakeholders who work with hospitalists will be more informed and better-educated team members in the patient care process. Hospitalists can be the key ingredient and centerpiece in effective inpatient medical education.

References

- Yale New Haven Hospital Report, March 2004.

- Ward, Michael R. “Drug approval overregulation.” Regulation: the Review of Business and Government. Cato Institute, September 27, 2004.

- Pak, MH. Associate Professor of Medicine, Hospitalist, Director, General Medicine Consultation Service, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison, WI.

- Ranji S, Rosenman D. “Hospital medicine fellowship update.” The Hospitalist. 2004; 8 (5): 39.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. “The hospitalist movement five years later.” JAMA.2002; 287(4): 487-94.

- Saint S, Flanders SA. “Hospitalists in teaching hospitals: opportunities but not without danger.” J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19: 392-3.

- Chung P, Morrison J, Jin L, Levinson W, Humphrey H, Meltzer D. “Resident satisfaction on an academic hospitalist service: time to teach.” Am J Med. 2002; 112: 597-601.

- Landrigan CP, Muret-Wagstaff S, Chiang VW, Nigrin DJ, Goldmann DA, Finkelstein JA. “Effect of a pediatric hospitalist system on housestaff education and experience.” Arch Ped Adoles Med. 2002; 156 (9): 877-83.

- Hunter AJ, Desai SS, Harrison RA, Chan BK. “Medical student evaluation of the quality of hospitalist and non-hospitalist teaching faculty on inpatient medicine rotations.” Acad Med. 2004; 79:78-82.

- 10. Kulaga, ME. “The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators.” J Gen Intern Med.2004; 19(4): 293-301.

- Hauer K, Wachter R, McCulloch C, Woo G, Auerbach A. Effects of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee satisfaction with teaching and with internal medicine rotations. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164: 1866-71.

- Jones T, DO. Director of Medical Affairs, IPC, The Hospitalist Company, Mesa, AZ.

- Amin A, MD, MBA, FACP, executive director, Hospitalist Program, University of California, Irvine. Chair, Education Committee, Society of Hospital Medicine. Personal interview. October 7, 2004.

Type a medical condition or term into a search engine and watch what happens. A search on the words “diabetes” yields more than 13 million Web pages, and “pneumonia” produces another 1.65 million. In 1998, the Internet hosted approximately 5000 health-related Web sites; two years later that number quadrupled (1). Between 30,000 and 45,000 medical articles on various drug therapies are published annually. The Patent and Trademark Office issued between 2000 and 4200 drug patents each year between 1979 and 1989 (2). The National Library of Medicine reports that it adds more than 2000 journal article citations to its MEDLINE database on a daily basis. In 2003, more than 460,000 citations were entered.

Deciphering and applying this myriad of changing information is a critical activity in the medical field. Without disseminating new knowledge through ongoing education, medical practices and procedures would become outdated, and uninformed medical professionals and patients would continue to operate under misinformation that might be detrimental to health or worse.

Hospitalists as Inpatient Experts

In an inpatient setting, hospitalists are uniquely qualified to play the role of educator. They analyze and interpret a wide range of medical information to treat their patients and provide updated information to patients and their families, residents, interns, nursing staff, other health care professionals, and hospital administrators. The hospitalist can be viewed as the “hub” of educational activities in the inpatient environment, absorbing, synthesizing, and disseminating information. They are “inpatient experts” in the following five spheres of knowledge:

- patient management

- clinical knowledge

- clinical skills

- health care industry issues

- research and management/leadership (3)

Hospitalists are uniquely qualified in the sphere of patient management, efficiently and effectively guiding the patient through the mazelike inpatient environment. Most hospitalists are quite familiar with critical hospital functions and activities, including treatment in the emergency department, the admissions process, bedside care on the medical floor, treatment in the intensive care unit, and the discharge process. Hospitalists, because they understand “how to get things done” by ancillary departments, including diagnostic and therapeutic services, often find themselves as conductors of inpatient care. Many hospitalists have developed unique proficiency in co-managing surgical cases due to expertise in peri-operative evaluation and care. Hospitalists are recognized as inpatient team leaders, facilitating and coordinating a range of support services needed to treat the patient, including nursing, case management, pharmacy, occupational/physical therapy, and social work. Hospitalists must also be effective in managing relationships with health care personnel external to the inpatient environment, including community physicians, homecare providers, extended care facilities, and visiting nurse services. Finally, hospitalists are oaen well informed about hospital processes, procedures, rules, regulations, and information systems.

As inpatient generalists, hospitalists continually treat the most common reasons for admission and have exceptional clinical knowledge of these conditions. These conditions include pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), congestive heart failure (CHF), diabetes, end-of-life care, and other medical diagnoses. Since they treat many elderly patients, hospitalists are considered experts in managing patients with multiple co-morbidities. A related area of expertise is clinical guidelines/pathways, quality of care metrics, and practice standards. Since they spend nearly all of their time treating inpatients, hospitalists develop extraordinary familiarity with the clinical rules and tools supporting the patient care process.

In addition to clinical knowledge, hospitalists have the experience and expertise to teach inpatient clinical skills. These skills include diagnosis, physical examination, discharge planning, medical chart recording, family meeting coordination, and oversight. Also, most hospitalists are familiar with a range of technical procedures, including insertion of central lines and arterial lines, lumbar puncture, arthrocentesis, paracentesis, and thoracentesis.

Hospitalists often are the most knowledgeable inpatient clinicians with regard to a wide range of health care industry issues. These include comprehension of the payer/insurance regulations regarding medication formularies, utilization review requirements, and other care policies. Their expertise may extend to knowledge of state and federal regulations, public health initiatives, and recently enacted or pending health care legislation. Finally, hospitalists also are often conversant in the field of health care economics, especially regarding the financial impact on hospitals of reimbursement policies, legislative initiatives, technology, etc.

The fifth sphere of hospitalist expertise combines several knowledge domains. Individual hospitalists have specialized expertise in particular fields related to hospital medicine. Some hospitalists, mostly affiliated with academic institutions, are researchers who may develop research protocols, gather data, perform statistical analyses, and write papers that may potentially become the basis of improved patient care. Other hospitalists are exceptionally experienced in management/leadership. A hospitalist may be highly qualified to manage projects (e.g., computer-based physician order entry systems, throughput initiatives, etc.),or a hospitalist could be a strategic thinker who is viewed as a key clinical member of the hospital’s management team.

As a growing specialty, hospitalists have established a proficiency in a range of disciplines and intellectual domains. They are well positioned to assume the role of educator in the hospital environment. Given the exceptional knowledge and skills needed to be a hospitalist, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) is pursing an effort to standardize education and lend greater credibility to the hospitalist profession. The “core curriculum” project is currently formalizing training that will provide a solid foundation for effective clinical practice in the field of hospital medicine.

Dual Educational Tracks

As depicted in Figure 1 below, medical education activity and the ways in which knowledge is imparted fall into two categories: formal and informal. Although some overlap may occur, there are distinct characteristics attributable to both classifications.

“Formal”

Formal education refers to the traditional “teacher-learner” roles in medicine. The learner can be a medical student, resident, or fellow. Education is typically transmitted from teacher to learner (as depicted in the diagram by a solid line), with some reciprocal feedback from the learner to the teacher (dotted line). It should be noted that as the importance and value of hospital medicine programs gain recognition, fellowship programs focusing on this specialty have been established. As of August 2004, eight active hospital medicine fellowship programs exist in the United States: three in California, two in Minnesota, and one each in Ohio, Illinois, and Texas. There are also pediatric hospital medicine fellowship programs in Boston, Washington DC, Houston, and San Diego. Each program enrolls one or two fellows annually (4).

Formal education can take place in both academic medical centers and community hospitals. By definition, academic medical centers provide supervised practical training for medical students, student nurses, and/or other health care professionals, as well as residents and fellows. In many academic medical centers throughout the country, hospitalists are emerging as core teachers of inpatient medicine. A prime example is the University of California, San Francisco. In 2002, 15 faculty hospitalists served as staff for approximately two-thirds of ward-attending months, as well as all medical consults (5).

By the same token, community hospitals that have residency programs also incorporate education to some degree into their daily operations. Today, medical education places a significant burden on residents and on the professionals charged with teaching students to absorb and understand vast amounts of science and medical information. On July 1, 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) revised the regulations governing the number of resident duty hours. These changes have forced residency programs to find viable options for imparting the required knowledge and hands-on experience to residents in fewer hours. Many consider hospitalists, by virtue of their “superior clinical and educational skills,” as representative of “the solution to the residency work duty problem.” In addition to providing excellence in teaching, hospitalists, known for their “superior clinical and educational skills,” may lead the way in creating and leading a clinical research agenda, which presents as the ultimate pedagogical experience (6).

In 2002, ACGME required six general competencies to be incorporated into residency curriculum and evaluation: patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. Hospitalists, because their practice already incorporates many aspects of these competencies, may be more effective at teaching these concepts to residents.

In the formal capacity of teacher, hospitalists can participate in attending/teaching rounds and in didactic patient-specific sessions presented in a case-based format, which provides residents with basic knowledge. As teaching supervisors, they can oversee the full range of clinical processes and procedures from the admission stage to post-discharge. Hospitalist teachers can also serve as mentors, providing a role model to residents who may be searching for direction regarding future plans. Through career counseling, hospitalists may steer learners into appropriate areas of study and training. Table 1 summarizes a series of research studies that document the positive impact hospitalists have achieved as educators in the academic environment.

Hospitalists may also have formal responsibility for developing curricula for learners in the academic environment. Whether the focus is on teaching medical students, residents, or hospitalist fellows, there is a need to determine the topics and material to be covered, incorporate them into a cogent curriculum, and update regularly to reflect the changing standards of care.

“Informal”

Informal education can be viewed as an exchange of information among stakeholders in the health care industry attempting to improve outcomes. Figure 1 depicts this as a two-way information exchange (solid arrows in both directions). As hospitalists impart knowledge to primary care physicians (PCPs), specialists/surgeons, other health care professionals (including nurses and pharmacists), patients, families, and hospital administrators, they reap benefits as well. These stakeholders stand to profit from the knowledge hospitalists can impart in daily interactions within the hospital and in less formal settings.

By working together with nurses, emergency room physicians, medical specialists, and PCPs, hospitalists can help achieve efficient and effective processes of care. The use of available software programs enables health care professionals to cooperatively exchange reliable information regarding patient management. Ongoing conversations regarding diagnoses, treatment, medications, and procedures serve to keep each member of the team educated and informed, thus ensuring more efficient delivery of care (12).

Alpesh Amin, MD, executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California, Irvine, and chair of SHM’s Education Committee, points out that hospitalists frequently have opportunities to act as educators during case-by-case interactions with PCPs and other health care providers. “Every time you talk to a doctor about admitting or discharging a patient, it’s an opportunity to educate,” he says. In addition, “the hospitalist can apply and/or develop critical pathways and algorithms to educate others.” In the course of managing care, criteria can be developed for previously unaddressed medical issues.

This same opportunity for education extends to the hospital floor where team building serves to enlighten each member of the group providing patient care. In a reciprocal environment, both hospitalists and their medical professional “teammates” benefit from each other’s knowledge. Amin points out that specialists typically focus on one condition, while hospitalists consider the entire patient. By openly receiving the specialist’s input and advice, processing it, and then applying it to the patient, the hospitalist can develop a comprehensive approach to disease management. By considering co-morbidities and long-term care, the health care team should base decisions on “patient-centered education (13).”

Hospitalists can initiate informal in-house educational outreach, such as informational programs about medical breakthroughs, new medications, explanations of existing medical legislation, and other relevant topics. These programs can enlighten nurses, case managers, pharmacists, and other health care professionals about issues important to managing patients and/or achieving quality outcomes. The format for these programs may be one-on-one interactions (either in-person or by telephone) relating to one specific patient; formal in-service lectures; “Lunch and Learns”; pharmaceutically funded drug- or-disease-management seminars; committee or departmental meetings, and/or random written communications (sent electronically or by interoffice mail) that incorporate history and physical findings, consultations, discharge summaries, or hard-copy articles (12).

Conclusion

Because they spend so much time in the hospital, hospitalists are experts on all aspects of inpatient care: clinical, administrative, patient flow, and health care industry issues. Published research shows that academic institutions that employ hospitalists will have more satisfied and better-educated students. Common sense suggests that nurses and other stakeholders who work with hospitalists will be more informed and better-educated team members in the patient care process. Hospitalists can be the key ingredient and centerpiece in effective inpatient medical education.

References

- Yale New Haven Hospital Report, March 2004.

- Ward, Michael R. “Drug approval overregulation.” Regulation: the Review of Business and Government. Cato Institute, September 27, 2004.

- Pak, MH. Associate Professor of Medicine, Hospitalist, Director, General Medicine Consultation Service, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison, WI.

- Ranji S, Rosenman D. “Hospital medicine fellowship update.” The Hospitalist. 2004; 8 (5): 39.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. “The hospitalist movement five years later.” JAMA.2002; 287(4): 487-94.

- Saint S, Flanders SA. “Hospitalists in teaching hospitals: opportunities but not without danger.” J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19: 392-3.

- Chung P, Morrison J, Jin L, Levinson W, Humphrey H, Meltzer D. “Resident satisfaction on an academic hospitalist service: time to teach.” Am J Med. 2002; 112: 597-601.

- Landrigan CP, Muret-Wagstaff S, Chiang VW, Nigrin DJ, Goldmann DA, Finkelstein JA. “Effect of a pediatric hospitalist system on housestaff education and experience.” Arch Ped Adoles Med. 2002; 156 (9): 877-83.

- Hunter AJ, Desai SS, Harrison RA, Chan BK. “Medical student evaluation of the quality of hospitalist and non-hospitalist teaching faculty on inpatient medicine rotations.” Acad Med. 2004; 79:78-82.

- 10. Kulaga, ME. “The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators.” J Gen Intern Med.2004; 19(4): 293-301.

- Hauer K, Wachter R, McCulloch C, Woo G, Auerbach A. Effects of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee satisfaction with teaching and with internal medicine rotations. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164: 1866-71.

- Jones T, DO. Director of Medical Affairs, IPC, The Hospitalist Company, Mesa, AZ.

- Amin A, MD, MBA, FACP, executive director, Hospitalist Program, University of California, Irvine. Chair, Education Committee, Society of Hospital Medicine. Personal interview. October 7, 2004.

Type a medical condition or term into a search engine and watch what happens. A search on the words “diabetes” yields more than 13 million Web pages, and “pneumonia” produces another 1.65 million. In 1998, the Internet hosted approximately 5000 health-related Web sites; two years later that number quadrupled (1). Between 30,000 and 45,000 medical articles on various drug therapies are published annually. The Patent and Trademark Office issued between 2000 and 4200 drug patents each year between 1979 and 1989 (2). The National Library of Medicine reports that it adds more than 2000 journal article citations to its MEDLINE database on a daily basis. In 2003, more than 460,000 citations were entered.

Deciphering and applying this myriad of changing information is a critical activity in the medical field. Without disseminating new knowledge through ongoing education, medical practices and procedures would become outdated, and uninformed medical professionals and patients would continue to operate under misinformation that might be detrimental to health or worse.

Hospitalists as Inpatient Experts

In an inpatient setting, hospitalists are uniquely qualified to play the role of educator. They analyze and interpret a wide range of medical information to treat their patients and provide updated information to patients and their families, residents, interns, nursing staff, other health care professionals, and hospital administrators. The hospitalist can be viewed as the “hub” of educational activities in the inpatient environment, absorbing, synthesizing, and disseminating information. They are “inpatient experts” in the following five spheres of knowledge:

- patient management

- clinical knowledge

- clinical skills

- health care industry issues

- research and management/leadership (3)

Hospitalists are uniquely qualified in the sphere of patient management, efficiently and effectively guiding the patient through the mazelike inpatient environment. Most hospitalists are quite familiar with critical hospital functions and activities, including treatment in the emergency department, the admissions process, bedside care on the medical floor, treatment in the intensive care unit, and the discharge process. Hospitalists, because they understand “how to get things done” by ancillary departments, including diagnostic and therapeutic services, often find themselves as conductors of inpatient care. Many hospitalists have developed unique proficiency in co-managing surgical cases due to expertise in peri-operative evaluation and care. Hospitalists are recognized as inpatient team leaders, facilitating and coordinating a range of support services needed to treat the patient, including nursing, case management, pharmacy, occupational/physical therapy, and social work. Hospitalists must also be effective in managing relationships with health care personnel external to the inpatient environment, including community physicians, homecare providers, extended care facilities, and visiting nurse services. Finally, hospitalists are oaen well informed about hospital processes, procedures, rules, regulations, and information systems.

As inpatient generalists, hospitalists continually treat the most common reasons for admission and have exceptional clinical knowledge of these conditions. These conditions include pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), congestive heart failure (CHF), diabetes, end-of-life care, and other medical diagnoses. Since they treat many elderly patients, hospitalists are considered experts in managing patients with multiple co-morbidities. A related area of expertise is clinical guidelines/pathways, quality of care metrics, and practice standards. Since they spend nearly all of their time treating inpatients, hospitalists develop extraordinary familiarity with the clinical rules and tools supporting the patient care process.

In addition to clinical knowledge, hospitalists have the experience and expertise to teach inpatient clinical skills. These skills include diagnosis, physical examination, discharge planning, medical chart recording, family meeting coordination, and oversight. Also, most hospitalists are familiar with a range of technical procedures, including insertion of central lines and arterial lines, lumbar puncture, arthrocentesis, paracentesis, and thoracentesis.

Hospitalists often are the most knowledgeable inpatient clinicians with regard to a wide range of health care industry issues. These include comprehension of the payer/insurance regulations regarding medication formularies, utilization review requirements, and other care policies. Their expertise may extend to knowledge of state and federal regulations, public health initiatives, and recently enacted or pending health care legislation. Finally, hospitalists also are often conversant in the field of health care economics, especially regarding the financial impact on hospitals of reimbursement policies, legislative initiatives, technology, etc.

The fifth sphere of hospitalist expertise combines several knowledge domains. Individual hospitalists have specialized expertise in particular fields related to hospital medicine. Some hospitalists, mostly affiliated with academic institutions, are researchers who may develop research protocols, gather data, perform statistical analyses, and write papers that may potentially become the basis of improved patient care. Other hospitalists are exceptionally experienced in management/leadership. A hospitalist may be highly qualified to manage projects (e.g., computer-based physician order entry systems, throughput initiatives, etc.),or a hospitalist could be a strategic thinker who is viewed as a key clinical member of the hospital’s management team.

As a growing specialty, hospitalists have established a proficiency in a range of disciplines and intellectual domains. They are well positioned to assume the role of educator in the hospital environment. Given the exceptional knowledge and skills needed to be a hospitalist, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) is pursing an effort to standardize education and lend greater credibility to the hospitalist profession. The “core curriculum” project is currently formalizing training that will provide a solid foundation for effective clinical practice in the field of hospital medicine.

Dual Educational Tracks

As depicted in Figure 1 below, medical education activity and the ways in which knowledge is imparted fall into two categories: formal and informal. Although some overlap may occur, there are distinct characteristics attributable to both classifications.

“Formal”

Formal education refers to the traditional “teacher-learner” roles in medicine. The learner can be a medical student, resident, or fellow. Education is typically transmitted from teacher to learner (as depicted in the diagram by a solid line), with some reciprocal feedback from the learner to the teacher (dotted line). It should be noted that as the importance and value of hospital medicine programs gain recognition, fellowship programs focusing on this specialty have been established. As of August 2004, eight active hospital medicine fellowship programs exist in the United States: three in California, two in Minnesota, and one each in Ohio, Illinois, and Texas. There are also pediatric hospital medicine fellowship programs in Boston, Washington DC, Houston, and San Diego. Each program enrolls one or two fellows annually (4).

Formal education can take place in both academic medical centers and community hospitals. By definition, academic medical centers provide supervised practical training for medical students, student nurses, and/or other health care professionals, as well as residents and fellows. In many academic medical centers throughout the country, hospitalists are emerging as core teachers of inpatient medicine. A prime example is the University of California, San Francisco. In 2002, 15 faculty hospitalists served as staff for approximately two-thirds of ward-attending months, as well as all medical consults (5).

By the same token, community hospitals that have residency programs also incorporate education to some degree into their daily operations. Today, medical education places a significant burden on residents and on the professionals charged with teaching students to absorb and understand vast amounts of science and medical information. On July 1, 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) revised the regulations governing the number of resident duty hours. These changes have forced residency programs to find viable options for imparting the required knowledge and hands-on experience to residents in fewer hours. Many consider hospitalists, by virtue of their “superior clinical and educational skills,” as representative of “the solution to the residency work duty problem.” In addition to providing excellence in teaching, hospitalists, known for their “superior clinical and educational skills,” may lead the way in creating and leading a clinical research agenda, which presents as the ultimate pedagogical experience (6).

In 2002, ACGME required six general competencies to be incorporated into residency curriculum and evaluation: patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. Hospitalists, because their practice already incorporates many aspects of these competencies, may be more effective at teaching these concepts to residents.

In the formal capacity of teacher, hospitalists can participate in attending/teaching rounds and in didactic patient-specific sessions presented in a case-based format, which provides residents with basic knowledge. As teaching supervisors, they can oversee the full range of clinical processes and procedures from the admission stage to post-discharge. Hospitalist teachers can also serve as mentors, providing a role model to residents who may be searching for direction regarding future plans. Through career counseling, hospitalists may steer learners into appropriate areas of study and training. Table 1 summarizes a series of research studies that document the positive impact hospitalists have achieved as educators in the academic environment.

Hospitalists may also have formal responsibility for developing curricula for learners in the academic environment. Whether the focus is on teaching medical students, residents, or hospitalist fellows, there is a need to determine the topics and material to be covered, incorporate them into a cogent curriculum, and update regularly to reflect the changing standards of care.

“Informal”

Informal education can be viewed as an exchange of information among stakeholders in the health care industry attempting to improve outcomes. Figure 1 depicts this as a two-way information exchange (solid arrows in both directions). As hospitalists impart knowledge to primary care physicians (PCPs), specialists/surgeons, other health care professionals (including nurses and pharmacists), patients, families, and hospital administrators, they reap benefits as well. These stakeholders stand to profit from the knowledge hospitalists can impart in daily interactions within the hospital and in less formal settings.

By working together with nurses, emergency room physicians, medical specialists, and PCPs, hospitalists can help achieve efficient and effective processes of care. The use of available software programs enables health care professionals to cooperatively exchange reliable information regarding patient management. Ongoing conversations regarding diagnoses, treatment, medications, and procedures serve to keep each member of the team educated and informed, thus ensuring more efficient delivery of care (12).

Alpesh Amin, MD, executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California, Irvine, and chair of SHM’s Education Committee, points out that hospitalists frequently have opportunities to act as educators during case-by-case interactions with PCPs and other health care providers. “Every time you talk to a doctor about admitting or discharging a patient, it’s an opportunity to educate,” he says. In addition, “the hospitalist can apply and/or develop critical pathways and algorithms to educate others.” In the course of managing care, criteria can be developed for previously unaddressed medical issues.

This same opportunity for education extends to the hospital floor where team building serves to enlighten each member of the group providing patient care. In a reciprocal environment, both hospitalists and their medical professional “teammates” benefit from each other’s knowledge. Amin points out that specialists typically focus on one condition, while hospitalists consider the entire patient. By openly receiving the specialist’s input and advice, processing it, and then applying it to the patient, the hospitalist can develop a comprehensive approach to disease management. By considering co-morbidities and long-term care, the health care team should base decisions on “patient-centered education (13).”

Hospitalists can initiate informal in-house educational outreach, such as informational programs about medical breakthroughs, new medications, explanations of existing medical legislation, and other relevant topics. These programs can enlighten nurses, case managers, pharmacists, and other health care professionals about issues important to managing patients and/or achieving quality outcomes. The format for these programs may be one-on-one interactions (either in-person or by telephone) relating to one specific patient; formal in-service lectures; “Lunch and Learns”; pharmaceutically funded drug- or-disease-management seminars; committee or departmental meetings, and/or random written communications (sent electronically or by interoffice mail) that incorporate history and physical findings, consultations, discharge summaries, or hard-copy articles (12).

Conclusion

Because they spend so much time in the hospital, hospitalists are experts on all aspects of inpatient care: clinical, administrative, patient flow, and health care industry issues. Published research shows that academic institutions that employ hospitalists will have more satisfied and better-educated students. Common sense suggests that nurses and other stakeholders who work with hospitalists will be more informed and better-educated team members in the patient care process. Hospitalists can be the key ingredient and centerpiece in effective inpatient medical education.

References

- Yale New Haven Hospital Report, March 2004.

- Ward, Michael R. “Drug approval overregulation.” Regulation: the Review of Business and Government. Cato Institute, September 27, 2004.

- Pak, MH. Associate Professor of Medicine, Hospitalist, Director, General Medicine Consultation Service, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison, WI.

- Ranji S, Rosenman D. “Hospital medicine fellowship update.” The Hospitalist. 2004; 8 (5): 39.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. “The hospitalist movement five years later.” JAMA.2002; 287(4): 487-94.

- Saint S, Flanders SA. “Hospitalists in teaching hospitals: opportunities but not without danger.” J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19: 392-3.

- Chung P, Morrison J, Jin L, Levinson W, Humphrey H, Meltzer D. “Resident satisfaction on an academic hospitalist service: time to teach.” Am J Med. 2002; 112: 597-601.

- Landrigan CP, Muret-Wagstaff S, Chiang VW, Nigrin DJ, Goldmann DA, Finkelstein JA. “Effect of a pediatric hospitalist system on housestaff education and experience.” Arch Ped Adoles Med. 2002; 156 (9): 877-83.

- Hunter AJ, Desai SS, Harrison RA, Chan BK. “Medical student evaluation of the quality of hospitalist and non-hospitalist teaching faculty on inpatient medicine rotations.” Acad Med. 2004; 79:78-82.

- 10. Kulaga, ME. “The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators.” J Gen Intern Med.2004; 19(4): 293-301.

- Hauer K, Wachter R, McCulloch C, Woo G, Auerbach A. Effects of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee satisfaction with teaching and with internal medicine rotations. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164: 1866-71.

- Jones T, DO. Director of Medical Affairs, IPC, The Hospitalist Company, Mesa, AZ.

- Amin A, MD, MBA, FACP, executive director, Hospitalist Program, University of California, Irvine. Chair, Education Committee, Society of Hospital Medicine. Personal interview. October 7, 2004.