User login

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

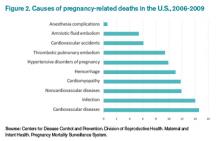

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.