User login

Extraesophageal reflux (EER) symptoms are a subset of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that can be difficult to diagnose because of its heterogeneous nature and symptoms that overlap with other conditions.

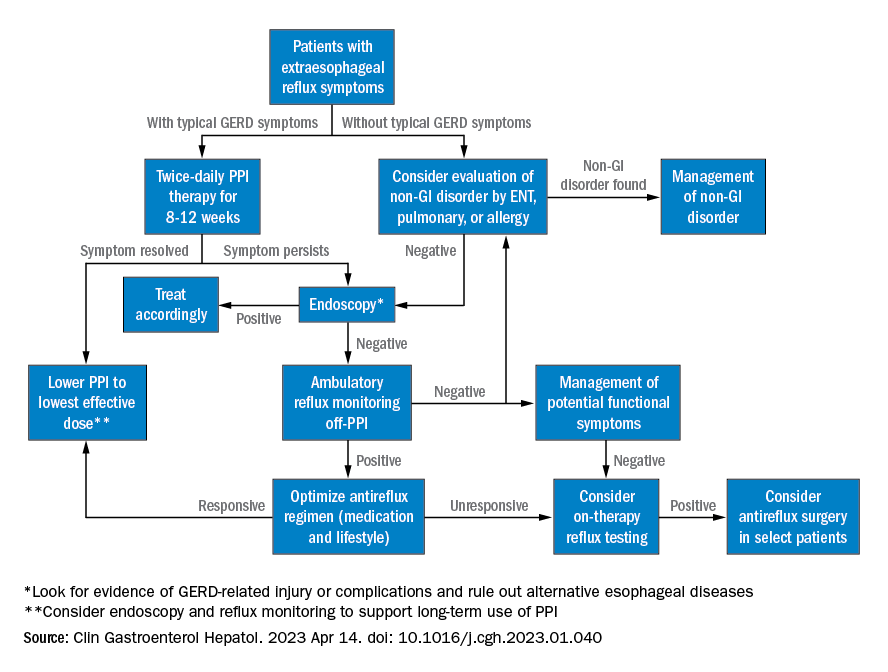

That puts the onus on physicians to take all symptoms into account and work across disciplines to diagnose, manage, and treat the condition, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

GERD is becoming increasingly common, which in turn has led to greater awareness and consideration of EER symptoms. EER symptoms can present a challenge because they may vary considerably and are not unique to GERD. The symptoms often do not respond well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

EER symptoms can include cough, laryngeal hoarseness, dysphonia, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, dental erosions/caries, sinus disease, ear disease, postnasal drip, and throat clearing. Some patients with EER symptoms do not report heartburn or regurgitation, which leaves it up to the physician to determine if acid reflux is present and contributing to symptoms.

“The concept of extraesophageal symptoms secondary to GERD is complex and often controversial, leading to diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Several extraesophageal symptoms have been associated with GERD, although the strength of evidence to support a causal relation varies,” wrote the authors, who were led by Joan W. Chen, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

There is also debate over whether fluid refluxate is the source of damage that causes EER symptoms, and if so, whether it is sufficient that the fluid be acidic or that pepsin be present, or if the cause is related to neurogenic signaling and resulting inflammation. Because of these questions, a PPI trial will not necessarily provide insight into the role of acid reflux in EER symptoms.

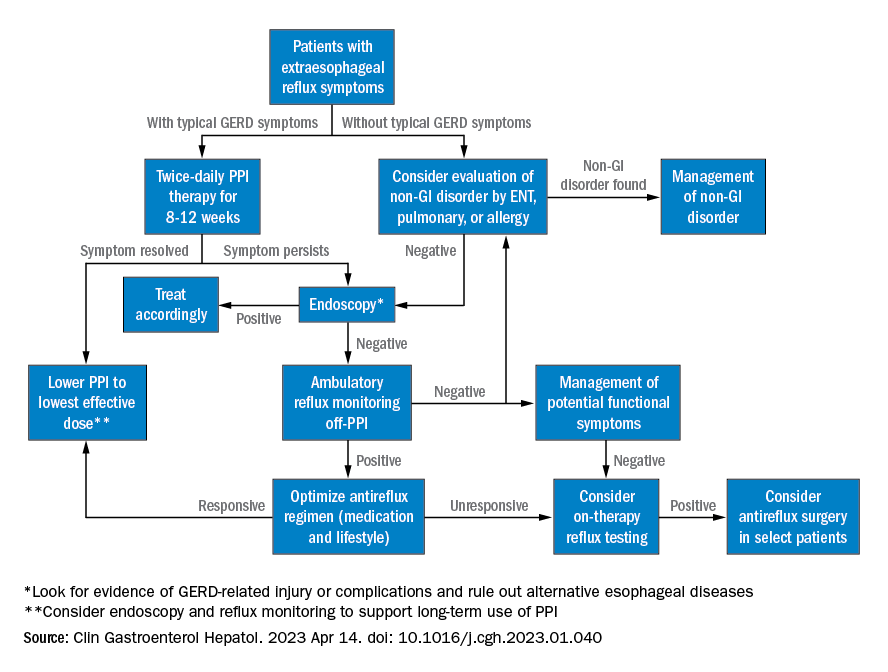

Best practice advice 1: The authors emphasized that gastroenterologists need to be aware of the potential extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. They should inquire with GERD patients to determine if laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, and dental erosions are present.

Best practice advice 2: Consider a multidisciplinary approach to EER manifestations. Cases may require input from non-GI specialties. Tests performed by other specialists, such as bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, or laryngoscopy, should be taken into account, since patients will also seek out multiple specialists to address their symptoms.

Best practice advice 3: There is no specific diagnostic test available to determine if GER is the cause of EER symptoms. Instead, physicians should interpret patient symptoms, response to GER therapy, and input from endoscopy and reflux tests.

Best practice advice 4: Rather than subject the patient to the cost and potential for even rare adverse events of a PPI trial, physicians should first consider conducting reflux testing. A PPI trial has clinical value but is insufficient on its own to help diagnose or manage EER. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily in those with typical GERD symptoms, is reasonable.

Best practice advice 5: The inconsistent therapeutic response to PPI therapy means that positive effects of PPI therapy on EER symptoms can’t confirm a GERD diagnosis because a placebo effect may be involved, and because symptom improvement can occur through mechanisms other than acid suppression. A meta-analysis found that a PPI trial has a sensitivity of 71%-78% and a specificity of 41%-54% with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. “Considering the greater variation expected with PPI response for extraesophageal symptoms, the diagnostic performance of empiric PPI trial for a diagnosis of EER would be anticipated to be substantially lower,” the authors wrote.

Best practice advice 6: When EER symptoms related to GERD are suspected and a PPI trial of up to 12 weeks does not lead to adequate improvement, the physician should consider testing for pathologic GER. Additional trials employing other PPIs are unlikely to succeed.

Best practice advice 7: Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation. Potential methods to evaluate reflux include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid suppressive therapy, which can assist with a GERD diagnosis, particularly when nonerosive reflux is present.

Best practice advice 8: About 50%-60% of patients with EER symptoms will not have GERD. Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GERD who do not respond well to high doses of acid suppression. Cost-effectiveness studies have confirmed the value of starting with ambulatory reflux monitoring, which can include a catheter-based pH sensor, pH impedance, or wireless pH capsule.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can also assist in making a GERD diagnosis, but it does not indicate whether GERD may be contributing to EER symptoms.

“Whichever the reflux testing modality, the strongest confidence for EER is achieved after ambulatory reflux testing showing pathologic acid exposure and a positive symptom-reflux association for EER symptoms,” the authors wrote. They also pointed out that ambulatory reflux monitoring in EER patients should be done in the absence of acid suppression unless there is already objective evidence for the presence of GERD.

Best practice advice 9: Aside from acid suppression, EER symptoms can also be managed through other means, including lifestyle modifications, such as eating avoidance prior to lying down, elevation of the head of the bed, sleeping on the left side, and weight loss. Or, alginate containing antacids, external upper esophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulators.

Best practice advice 10: In cases where the EER patient has objectively defined evidence of GERD, physicians should employ shared decision-making before considering anti-reflux surgery. If the patient did not respond to PPI therapy, this predicts a lack of response to antireflux surgery.

All four authors reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Extraesophageal reflux (EER) symptoms are a subset of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that can be difficult to diagnose because of its heterogeneous nature and symptoms that overlap with other conditions.

That puts the onus on physicians to take all symptoms into account and work across disciplines to diagnose, manage, and treat the condition, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

GERD is becoming increasingly common, which in turn has led to greater awareness and consideration of EER symptoms. EER symptoms can present a challenge because they may vary considerably and are not unique to GERD. The symptoms often do not respond well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

EER symptoms can include cough, laryngeal hoarseness, dysphonia, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, dental erosions/caries, sinus disease, ear disease, postnasal drip, and throat clearing. Some patients with EER symptoms do not report heartburn or regurgitation, which leaves it up to the physician to determine if acid reflux is present and contributing to symptoms.

“The concept of extraesophageal symptoms secondary to GERD is complex and often controversial, leading to diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Several extraesophageal symptoms have been associated with GERD, although the strength of evidence to support a causal relation varies,” wrote the authors, who were led by Joan W. Chen, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

There is also debate over whether fluid refluxate is the source of damage that causes EER symptoms, and if so, whether it is sufficient that the fluid be acidic or that pepsin be present, or if the cause is related to neurogenic signaling and resulting inflammation. Because of these questions, a PPI trial will not necessarily provide insight into the role of acid reflux in EER symptoms.

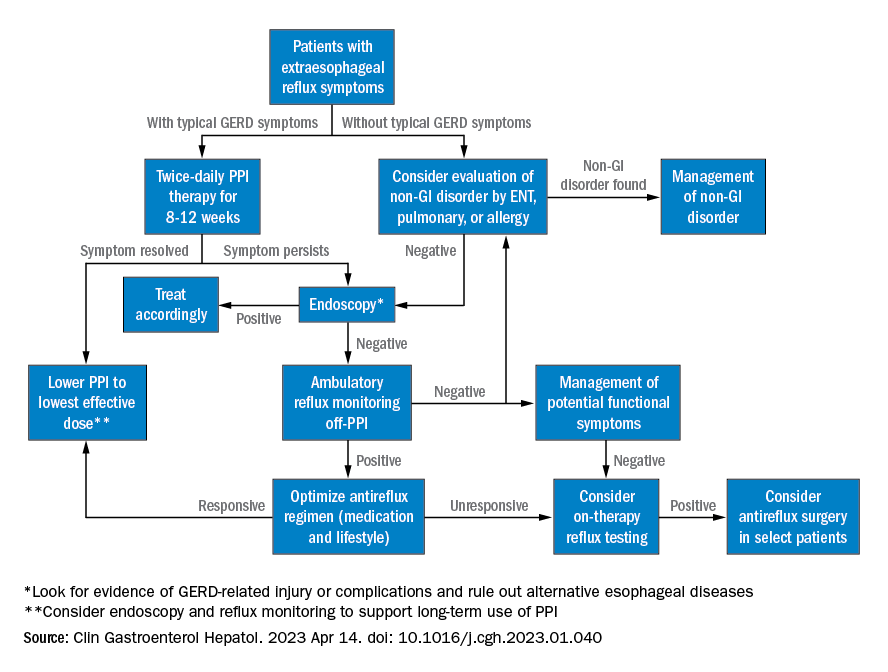

Best practice advice 1: The authors emphasized that gastroenterologists need to be aware of the potential extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. They should inquire with GERD patients to determine if laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, and dental erosions are present.

Best practice advice 2: Consider a multidisciplinary approach to EER manifestations. Cases may require input from non-GI specialties. Tests performed by other specialists, such as bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, or laryngoscopy, should be taken into account, since patients will also seek out multiple specialists to address their symptoms.

Best practice advice 3: There is no specific diagnostic test available to determine if GER is the cause of EER symptoms. Instead, physicians should interpret patient symptoms, response to GER therapy, and input from endoscopy and reflux tests.

Best practice advice 4: Rather than subject the patient to the cost and potential for even rare adverse events of a PPI trial, physicians should first consider conducting reflux testing. A PPI trial has clinical value but is insufficient on its own to help diagnose or manage EER. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily in those with typical GERD symptoms, is reasonable.

Best practice advice 5: The inconsistent therapeutic response to PPI therapy means that positive effects of PPI therapy on EER symptoms can’t confirm a GERD diagnosis because a placebo effect may be involved, and because symptom improvement can occur through mechanisms other than acid suppression. A meta-analysis found that a PPI trial has a sensitivity of 71%-78% and a specificity of 41%-54% with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. “Considering the greater variation expected with PPI response for extraesophageal symptoms, the diagnostic performance of empiric PPI trial for a diagnosis of EER would be anticipated to be substantially lower,” the authors wrote.

Best practice advice 6: When EER symptoms related to GERD are suspected and a PPI trial of up to 12 weeks does not lead to adequate improvement, the physician should consider testing for pathologic GER. Additional trials employing other PPIs are unlikely to succeed.

Best practice advice 7: Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation. Potential methods to evaluate reflux include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid suppressive therapy, which can assist with a GERD diagnosis, particularly when nonerosive reflux is present.

Best practice advice 8: About 50%-60% of patients with EER symptoms will not have GERD. Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GERD who do not respond well to high doses of acid suppression. Cost-effectiveness studies have confirmed the value of starting with ambulatory reflux monitoring, which can include a catheter-based pH sensor, pH impedance, or wireless pH capsule.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can also assist in making a GERD diagnosis, but it does not indicate whether GERD may be contributing to EER symptoms.

“Whichever the reflux testing modality, the strongest confidence for EER is achieved after ambulatory reflux testing showing pathologic acid exposure and a positive symptom-reflux association for EER symptoms,” the authors wrote. They also pointed out that ambulatory reflux monitoring in EER patients should be done in the absence of acid suppression unless there is already objective evidence for the presence of GERD.

Best practice advice 9: Aside from acid suppression, EER symptoms can also be managed through other means, including lifestyle modifications, such as eating avoidance prior to lying down, elevation of the head of the bed, sleeping on the left side, and weight loss. Or, alginate containing antacids, external upper esophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulators.

Best practice advice 10: In cases where the EER patient has objectively defined evidence of GERD, physicians should employ shared decision-making before considering anti-reflux surgery. If the patient did not respond to PPI therapy, this predicts a lack of response to antireflux surgery.

All four authors reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Extraesophageal reflux (EER) symptoms are a subset of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that can be difficult to diagnose because of its heterogeneous nature and symptoms that overlap with other conditions.

That puts the onus on physicians to take all symptoms into account and work across disciplines to diagnose, manage, and treat the condition, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

GERD is becoming increasingly common, which in turn has led to greater awareness and consideration of EER symptoms. EER symptoms can present a challenge because they may vary considerably and are not unique to GERD. The symptoms often do not respond well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

EER symptoms can include cough, laryngeal hoarseness, dysphonia, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, dental erosions/caries, sinus disease, ear disease, postnasal drip, and throat clearing. Some patients with EER symptoms do not report heartburn or regurgitation, which leaves it up to the physician to determine if acid reflux is present and contributing to symptoms.

“The concept of extraesophageal symptoms secondary to GERD is complex and often controversial, leading to diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Several extraesophageal symptoms have been associated with GERD, although the strength of evidence to support a causal relation varies,” wrote the authors, who were led by Joan W. Chen, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

There is also debate over whether fluid refluxate is the source of damage that causes EER symptoms, and if so, whether it is sufficient that the fluid be acidic or that pepsin be present, or if the cause is related to neurogenic signaling and resulting inflammation. Because of these questions, a PPI trial will not necessarily provide insight into the role of acid reflux in EER symptoms.

Best practice advice 1: The authors emphasized that gastroenterologists need to be aware of the potential extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. They should inquire with GERD patients to determine if laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, and dental erosions are present.

Best practice advice 2: Consider a multidisciplinary approach to EER manifestations. Cases may require input from non-GI specialties. Tests performed by other specialists, such as bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, or laryngoscopy, should be taken into account, since patients will also seek out multiple specialists to address their symptoms.

Best practice advice 3: There is no specific diagnostic test available to determine if GER is the cause of EER symptoms. Instead, physicians should interpret patient symptoms, response to GER therapy, and input from endoscopy and reflux tests.

Best practice advice 4: Rather than subject the patient to the cost and potential for even rare adverse events of a PPI trial, physicians should first consider conducting reflux testing. A PPI trial has clinical value but is insufficient on its own to help diagnose or manage EER. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily in those with typical GERD symptoms, is reasonable.

Best practice advice 5: The inconsistent therapeutic response to PPI therapy means that positive effects of PPI therapy on EER symptoms can’t confirm a GERD diagnosis because a placebo effect may be involved, and because symptom improvement can occur through mechanisms other than acid suppression. A meta-analysis found that a PPI trial has a sensitivity of 71%-78% and a specificity of 41%-54% with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. “Considering the greater variation expected with PPI response for extraesophageal symptoms, the diagnostic performance of empiric PPI trial for a diagnosis of EER would be anticipated to be substantially lower,” the authors wrote.

Best practice advice 6: When EER symptoms related to GERD are suspected and a PPI trial of up to 12 weeks does not lead to adequate improvement, the physician should consider testing for pathologic GER. Additional trials employing other PPIs are unlikely to succeed.

Best practice advice 7: Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation. Potential methods to evaluate reflux include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid suppressive therapy, which can assist with a GERD diagnosis, particularly when nonerosive reflux is present.

Best practice advice 8: About 50%-60% of patients with EER symptoms will not have GERD. Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GERD who do not respond well to high doses of acid suppression. Cost-effectiveness studies have confirmed the value of starting with ambulatory reflux monitoring, which can include a catheter-based pH sensor, pH impedance, or wireless pH capsule.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can also assist in making a GERD diagnosis, but it does not indicate whether GERD may be contributing to EER symptoms.

“Whichever the reflux testing modality, the strongest confidence for EER is achieved after ambulatory reflux testing showing pathologic acid exposure and a positive symptom-reflux association for EER symptoms,” the authors wrote. They also pointed out that ambulatory reflux monitoring in EER patients should be done in the absence of acid suppression unless there is already objective evidence for the presence of GERD.

Best practice advice 9: Aside from acid suppression, EER symptoms can also be managed through other means, including lifestyle modifications, such as eating avoidance prior to lying down, elevation of the head of the bed, sleeping on the left side, and weight loss. Or, alginate containing antacids, external upper esophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulators.

Best practice advice 10: In cases where the EER patient has objectively defined evidence of GERD, physicians should employ shared decision-making before considering anti-reflux surgery. If the patient did not respond to PPI therapy, this predicts a lack of response to antireflux surgery.

All four authors reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY