User login

In the last installment of this column we considered how group creativity can go very wrong even when all the neurobiological pieces are working properly. In this installment we will discuss how aging, a normal and inevitable consequence of living, affects these neurobiological pieces and in turn might affect creativity. The effect of age on creativity is particularly salient at this time when the most rapidly growing age demographic of our society is the oldest old. We see this in and around us: Baby boomers are reaching retirement, medical advances are reducing the rate of disease-related deaths, physicians are aging, we neurologists are aging.

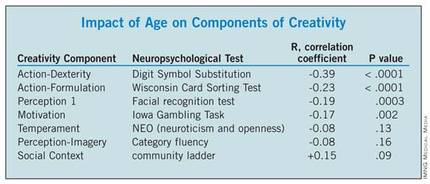

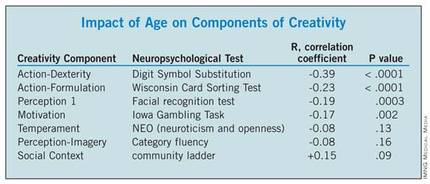

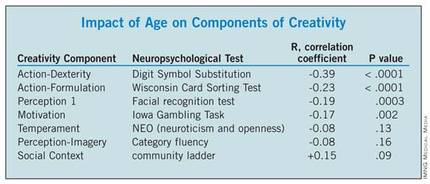

There are many cognitive manifestations of aging. In a cognitive aging study of the Arizona APOE Cohort that I led (Neurology 2011;76:1383-8), neuropsychological measures reflecting different components of creativity tended to decline with age (as seen in the accompanying table). These are the same components of the model of creativity that I introduced in a previous column. The cohort included 351 healthy individuals aged 21-81 years (two-thirds were women), with a mean educational level of nearly 16 years, who completed the Iowa Gambling Task and a battery of other tests.

The data in the table are presented for illustration purposes only, and do not constitute a thorough analysis of all aspects of creativity, but our findings do reflect those that others have reported as well in studies focused on creativity. With increasing age comes greater wisdom (as reflected by higher scores on tests of general knowledge and vocabulary not shown above), greater accumulated assets both materially and in terms of social standing (reflected in the Community ladder above). On the other hand, there appears to be a decline in motivational intensity and reward-based learning caused by age-related alterations in reward systems (Brain Res. Bull. 2005;67:382-90). Senescent changes in the neural machinery of perception, executive function, and dexterity cause these skills to decline even more (Am. J. Psychiatry 1998;155:344-9), and if our data is at all representative, it is in the area of action – including both strategic formulation and dexterous execution – that the biggest declines occur. Temperament, on the other hand, seems to be relatively stable, showing little change with age.

What is the net effect of increasing knowledge, assets, and social standing coupled with declining motivation, perception, and execution on individual creativity? Studies of creative productivity over a lifetime have revealed that noteworthy achievements tend to remain in constant proportion to one’s total creative output (Psychol. Bull. 1988;104:251-67). That is, the more one creates, the more noteworthy creations are produced. Even in old age, this ratio generally remains constant. What changes is the total output. Over the course of a lifetime, there is a ramp-up period leading eventually to a maximally productive phase, typically from one’s late 30s to their late 40s or early 50s (depending in part on the field of creative endeavor), and then a declining phase (not as steep as the initial ramp-up phase). The later years are also vulnerable to external circumstances such as illness and family problems. So the good news is that one’s ability to generate good work does not decline with age. The bad news is that total productivity does decline, and so too therefore does the total number of noteworthy contributions. This has been demonstrated in a variety of creative arenas including the arts and sciences.

Leadership ability, a specific form of creative behavior, appears to be relatively resilient with age. Two different aspects of cognition are crystallized or accumulated knowledge and fluid ability reflecting reasoning, memory, and speed. Our fluid ability peaks before age 30, yet the peak age for CEOs is 60. Accumulated knowledge increases with age until roughly age 60, after which it declines modestly, while fluid ability, such as novel problem solving, declines more steeply with age after its early age peak.

What accounts for the mismatch between declining fluid intelligence and work performance is unclear but may reflect at least four factors, including 1) one seldom needs to perform at their maximum level, 2) there is a shift with age from novel processing (fluid problem solving) to greater reliance on accumulated knowledge, 3) cognition may not be the only determinant of success ("can do, will do, have done"... the latter two represent temperament and experience), and 4) accommodations can be made for some declining skills (Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012;63:201-26). A fifth possibly related factor may be that older-appearing individuals are preferred as leaders during times of intergroup conflict (PLoS One 2012;7:e36945), a state in which most companies find themselves most of the time.

However, group members who are not in leadership positions may not be as fortunate. Few things are the same now as they were 10 years ago, and the rate of change has accelerated in the computer-catalyzed information age. Biological evolution may be slow, but ideas evolve quickly.

Meme evolution eventually results in meme speciation, with the consequence that memes of different species can no longer interbreed. Consider the example of subspecialization in medicine. We all begin as medical students with a common knowledge base and vernacular, but with subspecialization a child psychiatrist no longer has anything in common with a transplant surgeon. Even within neurology, there is little knowledge shared between epileptologists and neuroimmunologists.

Older individuals who failed to align themselves with one meme line (or physicians who failed to specialize) may find their ideas can no longer "interbreed" with the new meme species (or currently practiced medical specialties). Even within a field, those who fail to keep up with evolving technology will find themselves left behind, such as an aging surgeon who may not have mastered new robotic techniques or an aging secretary who may not understand the latest software. Add to this state of brain affairs, the prevalent ailments of the aging body such as arthritis, hypertension, and deconditioning, and we find that our workforce is not simply getting older, it actually is at risk of becoming obsolete.

And so the effects of age upon our creative behavior are varied and determined not only by our neurobiology, but also by our health (both physical and mental), our family and friends, and our fortune (or lack of it). Next month, we will conclude our 2-year series on creativity and its disorders.

Dr. Caselli is medical editor of Clinical Neurology News and is a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.

In the last installment of this column we considered how group creativity can go very wrong even when all the neurobiological pieces are working properly. In this installment we will discuss how aging, a normal and inevitable consequence of living, affects these neurobiological pieces and in turn might affect creativity. The effect of age on creativity is particularly salient at this time when the most rapidly growing age demographic of our society is the oldest old. We see this in and around us: Baby boomers are reaching retirement, medical advances are reducing the rate of disease-related deaths, physicians are aging, we neurologists are aging.

There are many cognitive manifestations of aging. In a cognitive aging study of the Arizona APOE Cohort that I led (Neurology 2011;76:1383-8), neuropsychological measures reflecting different components of creativity tended to decline with age (as seen in the accompanying table). These are the same components of the model of creativity that I introduced in a previous column. The cohort included 351 healthy individuals aged 21-81 years (two-thirds were women), with a mean educational level of nearly 16 years, who completed the Iowa Gambling Task and a battery of other tests.

The data in the table are presented for illustration purposes only, and do not constitute a thorough analysis of all aspects of creativity, but our findings do reflect those that others have reported as well in studies focused on creativity. With increasing age comes greater wisdom (as reflected by higher scores on tests of general knowledge and vocabulary not shown above), greater accumulated assets both materially and in terms of social standing (reflected in the Community ladder above). On the other hand, there appears to be a decline in motivational intensity and reward-based learning caused by age-related alterations in reward systems (Brain Res. Bull. 2005;67:382-90). Senescent changes in the neural machinery of perception, executive function, and dexterity cause these skills to decline even more (Am. J. Psychiatry 1998;155:344-9), and if our data is at all representative, it is in the area of action – including both strategic formulation and dexterous execution – that the biggest declines occur. Temperament, on the other hand, seems to be relatively stable, showing little change with age.

What is the net effect of increasing knowledge, assets, and social standing coupled with declining motivation, perception, and execution on individual creativity? Studies of creative productivity over a lifetime have revealed that noteworthy achievements tend to remain in constant proportion to one’s total creative output (Psychol. Bull. 1988;104:251-67). That is, the more one creates, the more noteworthy creations are produced. Even in old age, this ratio generally remains constant. What changes is the total output. Over the course of a lifetime, there is a ramp-up period leading eventually to a maximally productive phase, typically from one’s late 30s to their late 40s or early 50s (depending in part on the field of creative endeavor), and then a declining phase (not as steep as the initial ramp-up phase). The later years are also vulnerable to external circumstances such as illness and family problems. So the good news is that one’s ability to generate good work does not decline with age. The bad news is that total productivity does decline, and so too therefore does the total number of noteworthy contributions. This has been demonstrated in a variety of creative arenas including the arts and sciences.

Leadership ability, a specific form of creative behavior, appears to be relatively resilient with age. Two different aspects of cognition are crystallized or accumulated knowledge and fluid ability reflecting reasoning, memory, and speed. Our fluid ability peaks before age 30, yet the peak age for CEOs is 60. Accumulated knowledge increases with age until roughly age 60, after which it declines modestly, while fluid ability, such as novel problem solving, declines more steeply with age after its early age peak.

What accounts for the mismatch between declining fluid intelligence and work performance is unclear but may reflect at least four factors, including 1) one seldom needs to perform at their maximum level, 2) there is a shift with age from novel processing (fluid problem solving) to greater reliance on accumulated knowledge, 3) cognition may not be the only determinant of success ("can do, will do, have done"... the latter two represent temperament and experience), and 4) accommodations can be made for some declining skills (Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012;63:201-26). A fifth possibly related factor may be that older-appearing individuals are preferred as leaders during times of intergroup conflict (PLoS One 2012;7:e36945), a state in which most companies find themselves most of the time.

However, group members who are not in leadership positions may not be as fortunate. Few things are the same now as they were 10 years ago, and the rate of change has accelerated in the computer-catalyzed information age. Biological evolution may be slow, but ideas evolve quickly.

Meme evolution eventually results in meme speciation, with the consequence that memes of different species can no longer interbreed. Consider the example of subspecialization in medicine. We all begin as medical students with a common knowledge base and vernacular, but with subspecialization a child psychiatrist no longer has anything in common with a transplant surgeon. Even within neurology, there is little knowledge shared between epileptologists and neuroimmunologists.

Older individuals who failed to align themselves with one meme line (or physicians who failed to specialize) may find their ideas can no longer "interbreed" with the new meme species (or currently practiced medical specialties). Even within a field, those who fail to keep up with evolving technology will find themselves left behind, such as an aging surgeon who may not have mastered new robotic techniques or an aging secretary who may not understand the latest software. Add to this state of brain affairs, the prevalent ailments of the aging body such as arthritis, hypertension, and deconditioning, and we find that our workforce is not simply getting older, it actually is at risk of becoming obsolete.

And so the effects of age upon our creative behavior are varied and determined not only by our neurobiology, but also by our health (both physical and mental), our family and friends, and our fortune (or lack of it). Next month, we will conclude our 2-year series on creativity and its disorders.

Dr. Caselli is medical editor of Clinical Neurology News and is a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.

In the last installment of this column we considered how group creativity can go very wrong even when all the neurobiological pieces are working properly. In this installment we will discuss how aging, a normal and inevitable consequence of living, affects these neurobiological pieces and in turn might affect creativity. The effect of age on creativity is particularly salient at this time when the most rapidly growing age demographic of our society is the oldest old. We see this in and around us: Baby boomers are reaching retirement, medical advances are reducing the rate of disease-related deaths, physicians are aging, we neurologists are aging.

There are many cognitive manifestations of aging. In a cognitive aging study of the Arizona APOE Cohort that I led (Neurology 2011;76:1383-8), neuropsychological measures reflecting different components of creativity tended to decline with age (as seen in the accompanying table). These are the same components of the model of creativity that I introduced in a previous column. The cohort included 351 healthy individuals aged 21-81 years (two-thirds were women), with a mean educational level of nearly 16 years, who completed the Iowa Gambling Task and a battery of other tests.

The data in the table are presented for illustration purposes only, and do not constitute a thorough analysis of all aspects of creativity, but our findings do reflect those that others have reported as well in studies focused on creativity. With increasing age comes greater wisdom (as reflected by higher scores on tests of general knowledge and vocabulary not shown above), greater accumulated assets both materially and in terms of social standing (reflected in the Community ladder above). On the other hand, there appears to be a decline in motivational intensity and reward-based learning caused by age-related alterations in reward systems (Brain Res. Bull. 2005;67:382-90). Senescent changes in the neural machinery of perception, executive function, and dexterity cause these skills to decline even more (Am. J. Psychiatry 1998;155:344-9), and if our data is at all representative, it is in the area of action – including both strategic formulation and dexterous execution – that the biggest declines occur. Temperament, on the other hand, seems to be relatively stable, showing little change with age.

What is the net effect of increasing knowledge, assets, and social standing coupled with declining motivation, perception, and execution on individual creativity? Studies of creative productivity over a lifetime have revealed that noteworthy achievements tend to remain in constant proportion to one’s total creative output (Psychol. Bull. 1988;104:251-67). That is, the more one creates, the more noteworthy creations are produced. Even in old age, this ratio generally remains constant. What changes is the total output. Over the course of a lifetime, there is a ramp-up period leading eventually to a maximally productive phase, typically from one’s late 30s to their late 40s or early 50s (depending in part on the field of creative endeavor), and then a declining phase (not as steep as the initial ramp-up phase). The later years are also vulnerable to external circumstances such as illness and family problems. So the good news is that one’s ability to generate good work does not decline with age. The bad news is that total productivity does decline, and so too therefore does the total number of noteworthy contributions. This has been demonstrated in a variety of creative arenas including the arts and sciences.

Leadership ability, a specific form of creative behavior, appears to be relatively resilient with age. Two different aspects of cognition are crystallized or accumulated knowledge and fluid ability reflecting reasoning, memory, and speed. Our fluid ability peaks before age 30, yet the peak age for CEOs is 60. Accumulated knowledge increases with age until roughly age 60, after which it declines modestly, while fluid ability, such as novel problem solving, declines more steeply with age after its early age peak.

What accounts for the mismatch between declining fluid intelligence and work performance is unclear but may reflect at least four factors, including 1) one seldom needs to perform at their maximum level, 2) there is a shift with age from novel processing (fluid problem solving) to greater reliance on accumulated knowledge, 3) cognition may not be the only determinant of success ("can do, will do, have done"... the latter two represent temperament and experience), and 4) accommodations can be made for some declining skills (Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012;63:201-26). A fifth possibly related factor may be that older-appearing individuals are preferred as leaders during times of intergroup conflict (PLoS One 2012;7:e36945), a state in which most companies find themselves most of the time.

However, group members who are not in leadership positions may not be as fortunate. Few things are the same now as they were 10 years ago, and the rate of change has accelerated in the computer-catalyzed information age. Biological evolution may be slow, but ideas evolve quickly.

Meme evolution eventually results in meme speciation, with the consequence that memes of different species can no longer interbreed. Consider the example of subspecialization in medicine. We all begin as medical students with a common knowledge base and vernacular, but with subspecialization a child psychiatrist no longer has anything in common with a transplant surgeon. Even within neurology, there is little knowledge shared between epileptologists and neuroimmunologists.

Older individuals who failed to align themselves with one meme line (or physicians who failed to specialize) may find their ideas can no longer "interbreed" with the new meme species (or currently practiced medical specialties). Even within a field, those who fail to keep up with evolving technology will find themselves left behind, such as an aging surgeon who may not have mastered new robotic techniques or an aging secretary who may not understand the latest software. Add to this state of brain affairs, the prevalent ailments of the aging body such as arthritis, hypertension, and deconditioning, and we find that our workforce is not simply getting older, it actually is at risk of becoming obsolete.

And so the effects of age upon our creative behavior are varied and determined not only by our neurobiology, but also by our health (both physical and mental), our family and friends, and our fortune (or lack of it). Next month, we will conclude our 2-year series on creativity and its disorders.

Dr. Caselli is medical editor of Clinical Neurology News and is a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.