User login

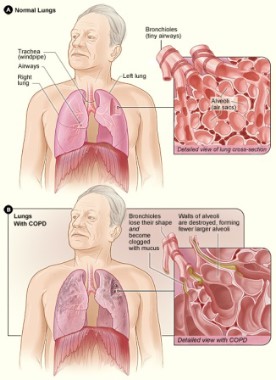

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations are a leading cause of admission and readmission in 2012, and they consume and exact a great toll on our patients while consuming a tremendous amount of resources. According to the American Lung Association, COPD is the third- leading cause of death, and it cost an estimated $50 billion in 2010 alone.

Although the typical day in the life of a hospitalist can be hectic, it is important for us to take the time to address simple yet crucial issues that impact the frequency and severity of COPD exacerbations. There are no magic bullets, but sometimes the basics can go a long way, as is the case with COPD treatment.

My colleague, pulmonologist William Han of Glen Burnie, Md., offers the following reminders:

• Smoking cessation. "Counseling patients to seek treatment as soon as possible when they experience symptoms of an exacerbation is ... of paramount importance, since steroids and antibiotics can often prevent an [emergency department] visit and a protracted hospitalization," he said. Most of us have had patients with advanced COPD who were on home oxygen and who, despite intense counseling, vowed to smoke until the day they died. Unfortunately, many of them did just that, as a result of this extraordinarily addictive habit.

• Vaccination. This is "of tremendous importance. We physicians tend to forget to check on the status of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines," Dr. Han said.

• Inhaler skills. "Many patients (and their physicians) do not know the correct way to use HFAs [hydrofluoroalkane inhalers]," Dr. Han noted. Up-to-Date Inc. has an easy-to-use instruction sheet to teach patients how to use their metered dose inhaler, and there are numerous other good resources as well.

COPD exacerbations are as much of a hospitalist issue as a primary care issue. After all, when patients are at their sickest, we are on the front lines working diligently to help them get through that exacerbation and back home to their families, hoping that a long time will elapse before the next one. But despite our best efforts, there are going to be those patients who just can’t stay out of the hospital for any extended period of time.

They stopped smoking a long time ago. They are already in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. They conscientiously use their long-acting inhaled beta-agonist, long-acting inhaled anticholinergic, and inhaled glucocorticoids, and yet their rescue inhalers and nebulizers are still needed frequently. So, what else can we do?

Maybe, after we have tried all the long-established treatments, it’s time to try something new. Because antibiotics work for acute exacerbations, would prophylactic use be beneficial as well?

The authors of a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine think so (2012; 367:340-7). They noted a trial in which researchers compared a daily dose of 250 mg of azithromycin vs. placebo for 1 year, with encouraging results. The trial, which involved 1,142 volunteers, showed that the median time to the first acute exacerbation of COPD was 174 days in the placebo group vs. 266 days in the azithromycin group – quite a profound difference, considering that each acute exacerbation that required hospitalization is associated with a 30-day all-cause death rate of up to 30%, the authors noted.

Macrolides have anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects in addition to bactericidal properties, which make them particularly well suited to tackling some of the pathophysiological aberrations of acute exacerbations of COPD.

Although this recommendation is not currently recommended by GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease), the findings do merit further consideration. This prophylactic regimen is not for everyone, but for a select group of patients it could be beneficial. The authors even went a step further by recommending considering using 250 mg of azithromycin on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays instead of each day, as tissue concentrations should be adequate to offer significant benefit even at this alternative dosing schedule.

However, it is important to note that certain patients may be at increased risk with this prophylactic regimen, including those on medications (such as statins, Coumadin, and amiodarone) in which significant drug-drug interactions could occur. In addition, patients should be screened for a prolonged QTc interval, as macrolides can prolong the QT interval and thus predispose to torsades de pointes. Even those with other significant heart disease (such as heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease) should be considered at higher-than-average risk. Patients with moderate or severe liver disease should also be excluded.

Even though hospitalists will not be following patients every 3 months for their recommended evaluation of medications, signs of ototoxicity, and EKG readings, we can still put a bug in the ear of primary care physicians to consider this approach when all else seems to fail.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations are a leading cause of admission and readmission in 2012, and they consume and exact a great toll on our patients while consuming a tremendous amount of resources. According to the American Lung Association, COPD is the third- leading cause of death, and it cost an estimated $50 billion in 2010 alone.

Although the typical day in the life of a hospitalist can be hectic, it is important for us to take the time to address simple yet crucial issues that impact the frequency and severity of COPD exacerbations. There are no magic bullets, but sometimes the basics can go a long way, as is the case with COPD treatment.

My colleague, pulmonologist William Han of Glen Burnie, Md., offers the following reminders:

• Smoking cessation. "Counseling patients to seek treatment as soon as possible when they experience symptoms of an exacerbation is ... of paramount importance, since steroids and antibiotics can often prevent an [emergency department] visit and a protracted hospitalization," he said. Most of us have had patients with advanced COPD who were on home oxygen and who, despite intense counseling, vowed to smoke until the day they died. Unfortunately, many of them did just that, as a result of this extraordinarily addictive habit.

• Vaccination. This is "of tremendous importance. We physicians tend to forget to check on the status of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines," Dr. Han said.

• Inhaler skills. "Many patients (and their physicians) do not know the correct way to use HFAs [hydrofluoroalkane inhalers]," Dr. Han noted. Up-to-Date Inc. has an easy-to-use instruction sheet to teach patients how to use their metered dose inhaler, and there are numerous other good resources as well.

COPD exacerbations are as much of a hospitalist issue as a primary care issue. After all, when patients are at their sickest, we are on the front lines working diligently to help them get through that exacerbation and back home to their families, hoping that a long time will elapse before the next one. But despite our best efforts, there are going to be those patients who just can’t stay out of the hospital for any extended period of time.

They stopped smoking a long time ago. They are already in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. They conscientiously use their long-acting inhaled beta-agonist, long-acting inhaled anticholinergic, and inhaled glucocorticoids, and yet their rescue inhalers and nebulizers are still needed frequently. So, what else can we do?

Maybe, after we have tried all the long-established treatments, it’s time to try something new. Because antibiotics work for acute exacerbations, would prophylactic use be beneficial as well?

The authors of a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine think so (2012; 367:340-7). They noted a trial in which researchers compared a daily dose of 250 mg of azithromycin vs. placebo for 1 year, with encouraging results. The trial, which involved 1,142 volunteers, showed that the median time to the first acute exacerbation of COPD was 174 days in the placebo group vs. 266 days in the azithromycin group – quite a profound difference, considering that each acute exacerbation that required hospitalization is associated with a 30-day all-cause death rate of up to 30%, the authors noted.

Macrolides have anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects in addition to bactericidal properties, which make them particularly well suited to tackling some of the pathophysiological aberrations of acute exacerbations of COPD.

Although this recommendation is not currently recommended by GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease), the findings do merit further consideration. This prophylactic regimen is not for everyone, but for a select group of patients it could be beneficial. The authors even went a step further by recommending considering using 250 mg of azithromycin on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays instead of each day, as tissue concentrations should be adequate to offer significant benefit even at this alternative dosing schedule.

However, it is important to note that certain patients may be at increased risk with this prophylactic regimen, including those on medications (such as statins, Coumadin, and amiodarone) in which significant drug-drug interactions could occur. In addition, patients should be screened for a prolonged QTc interval, as macrolides can prolong the QT interval and thus predispose to torsades de pointes. Even those with other significant heart disease (such as heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease) should be considered at higher-than-average risk. Patients with moderate or severe liver disease should also be excluded.

Even though hospitalists will not be following patients every 3 months for their recommended evaluation of medications, signs of ototoxicity, and EKG readings, we can still put a bug in the ear of primary care physicians to consider this approach when all else seems to fail.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations are a leading cause of admission and readmission in 2012, and they consume and exact a great toll on our patients while consuming a tremendous amount of resources. According to the American Lung Association, COPD is the third- leading cause of death, and it cost an estimated $50 billion in 2010 alone.

Although the typical day in the life of a hospitalist can be hectic, it is important for us to take the time to address simple yet crucial issues that impact the frequency and severity of COPD exacerbations. There are no magic bullets, but sometimes the basics can go a long way, as is the case with COPD treatment.

My colleague, pulmonologist William Han of Glen Burnie, Md., offers the following reminders:

• Smoking cessation. "Counseling patients to seek treatment as soon as possible when they experience symptoms of an exacerbation is ... of paramount importance, since steroids and antibiotics can often prevent an [emergency department] visit and a protracted hospitalization," he said. Most of us have had patients with advanced COPD who were on home oxygen and who, despite intense counseling, vowed to smoke until the day they died. Unfortunately, many of them did just that, as a result of this extraordinarily addictive habit.

• Vaccination. This is "of tremendous importance. We physicians tend to forget to check on the status of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines," Dr. Han said.

• Inhaler skills. "Many patients (and their physicians) do not know the correct way to use HFAs [hydrofluoroalkane inhalers]," Dr. Han noted. Up-to-Date Inc. has an easy-to-use instruction sheet to teach patients how to use their metered dose inhaler, and there are numerous other good resources as well.

COPD exacerbations are as much of a hospitalist issue as a primary care issue. After all, when patients are at their sickest, we are on the front lines working diligently to help them get through that exacerbation and back home to their families, hoping that a long time will elapse before the next one. But despite our best efforts, there are going to be those patients who just can’t stay out of the hospital for any extended period of time.

They stopped smoking a long time ago. They are already in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. They conscientiously use their long-acting inhaled beta-agonist, long-acting inhaled anticholinergic, and inhaled glucocorticoids, and yet their rescue inhalers and nebulizers are still needed frequently. So, what else can we do?

Maybe, after we have tried all the long-established treatments, it’s time to try something new. Because antibiotics work for acute exacerbations, would prophylactic use be beneficial as well?

The authors of a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine think so (2012; 367:340-7). They noted a trial in which researchers compared a daily dose of 250 mg of azithromycin vs. placebo for 1 year, with encouraging results. The trial, which involved 1,142 volunteers, showed that the median time to the first acute exacerbation of COPD was 174 days in the placebo group vs. 266 days in the azithromycin group – quite a profound difference, considering that each acute exacerbation that required hospitalization is associated with a 30-day all-cause death rate of up to 30%, the authors noted.

Macrolides have anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects in addition to bactericidal properties, which make them particularly well suited to tackling some of the pathophysiological aberrations of acute exacerbations of COPD.

Although this recommendation is not currently recommended by GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease), the findings do merit further consideration. This prophylactic regimen is not for everyone, but for a select group of patients it could be beneficial. The authors even went a step further by recommending considering using 250 mg of azithromycin on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays instead of each day, as tissue concentrations should be adequate to offer significant benefit even at this alternative dosing schedule.

However, it is important to note that certain patients may be at increased risk with this prophylactic regimen, including those on medications (such as statins, Coumadin, and amiodarone) in which significant drug-drug interactions could occur. In addition, patients should be screened for a prolonged QTc interval, as macrolides can prolong the QT interval and thus predispose to torsades de pointes. Even those with other significant heart disease (such as heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease) should be considered at higher-than-average risk. Patients with moderate or severe liver disease should also be excluded.

Even though hospitalists will not be following patients every 3 months for their recommended evaluation of medications, signs of ototoxicity, and EKG readings, we can still put a bug in the ear of primary care physicians to consider this approach when all else seems to fail.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.