User login

Ms. D, age 32, recently gave birth to her second child. Her psychiatric history includes major depressive disorder. She had been stable on mirtazapine 30 mg at bedtime for 3 years. Based on clinical stability and patient preference, Ms. D elected to taper off mirtazapine 1 month prior to delivery. Now at 1 month postdelivery, Ms. D notes the reemergence of her depressive symptoms; during her child’s latest pediatrician visit, she scores 15 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). She breastfeeds her baby and wants more information on the safety of taking an antidepressant while breastfeeding.

Ms. D discusses her previous use of mirtazapine with her treatment team. The team reviews the available resources with Ms. D and together they plan to make a shared decision regarding treatment of her depression at her next appointment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics1 and World Health Organization2 recommend exclusive breastfeeding of infants for their first 6 months of life and support it as a complement to other foods through and beyond age 2. Untreated conditions such as postpartum depression impact maternal well-being and may interfere with parenting and child development. In fact, untreated maternal mental health leads to an increased risk of suicide, reduced maternal economic productivity, and worsened health for both mother and child.3

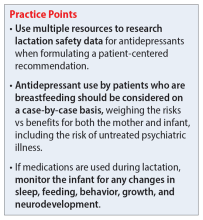

Because many women experience psychiatric symptoms before they become pregnant as well as during the perinatal period, questions often arise regardingthe use of psychiatric medications—specifically antidepressants—and their safety in patients who are breastfeeding. Key considerations regarding medication management should include the patient’s previous response to medications, the risks of untreated maternal mental illness, and evidence regarding risks and benefits in lactation. This article summarizes where to find evidence-based lactation information, how to interpret that information, and what information is available for select antidepressants.

Locating lactation information

Start by checking the manufacturer’s medication labeling (“prescribing information”) and medication information resources such as Micromedex (www.micromedexsolutions.com) and Lexicomp (www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/lexicomp). The updated labeling includes a risk/benefit assessment of available data on the risk for continued use of a medication during pregnancy compared to the risk if a medication is discontinued and the disorder goes untreated.4 The “breastfeeding considerations” section of medication labeling include details regarding the presence of the medication and the amount of it in breastmilk, adverse events in infants exposed to the medication through breastmilk, and additional pertinent data as applicable. Lexicomp includes information regarding breastfeeding considerations, and a subscription may also include access to Briggs Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation’s information pages. Micromedex includes its own lactation safety rating scale score.

Several other resources can help guide clinicians toward patient-specific recommendations. From the National Library of Medicine, LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/) allows clinicians to search for specific medications to see what information exists pertaining to medication levels in breastmilk and infant blood as well as potential adverse effects in the nursing infant and/or on lactation and breastmilk.5 LactMed provides information regarding alternative medications to consider and references from which the information was gathered.

Another helpful resource is the InfantRisk Center from Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, which includes a free call center for parents and clinicians who have questions about medications and breastfeeding (806-352-2519; Monday through Friday, 8

Continue to: How to interpret the information

How to interpret the information

Medication levels in breastmilk are affected by several properties, such as the medication’s molecular weight, protein binding, pKa, and volume of distribution. A few commonly used terms in lactation literature for medications include the relative infant dose (RID) and milk/plasma (M/P) ratio.

RID provides information about relative medication exposure for the infant. It is calculated by dividing the infant’s dose of a medication via breastmilk (mg/kg/d) by the mother’s dose (mg/kg/d).7 Most consider an RID <10% to be safe.7

M/P is the ratio of medication concentration in the mother’s milk divided by the medication concentration in the mother’s plasma. A ratio <1 is preferable and generally indicates that a low level of medication has been transferred to human milk.7

Another factor that can be evaluated is protein binding. Medications that are highly protein-bound do not tend to pass as easily into breastmilk and can minimize infant exposure.

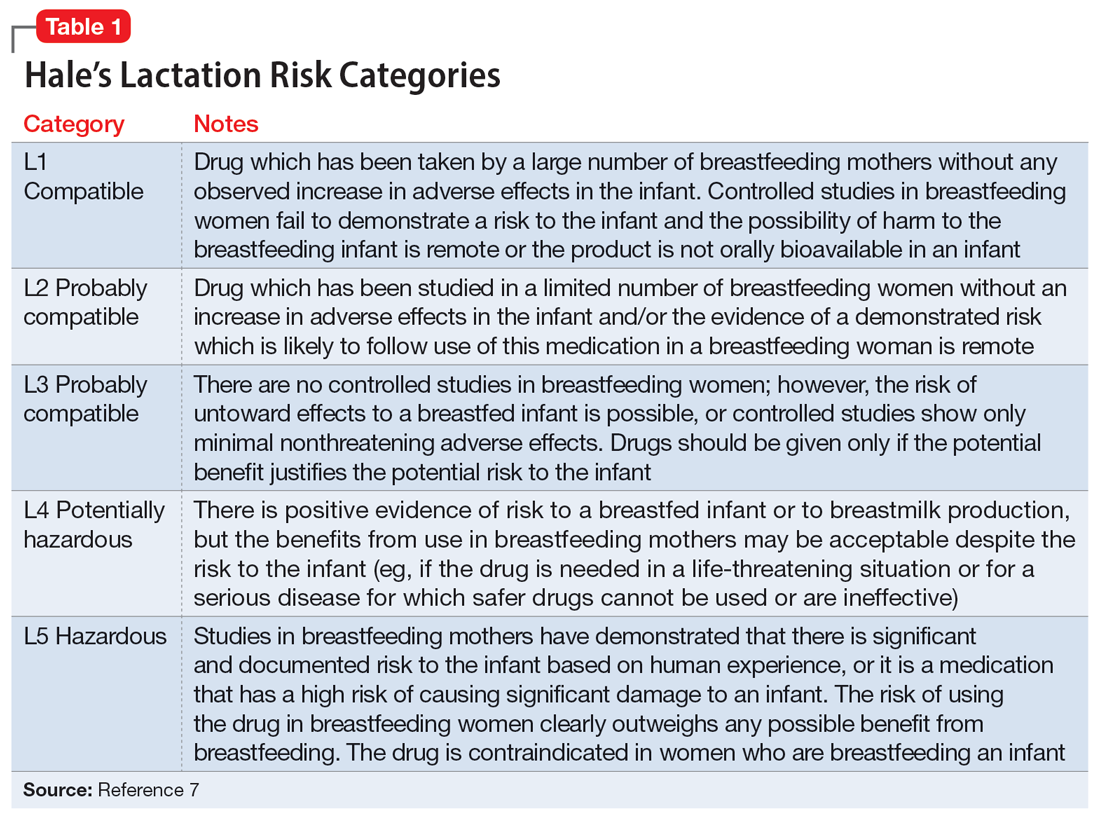

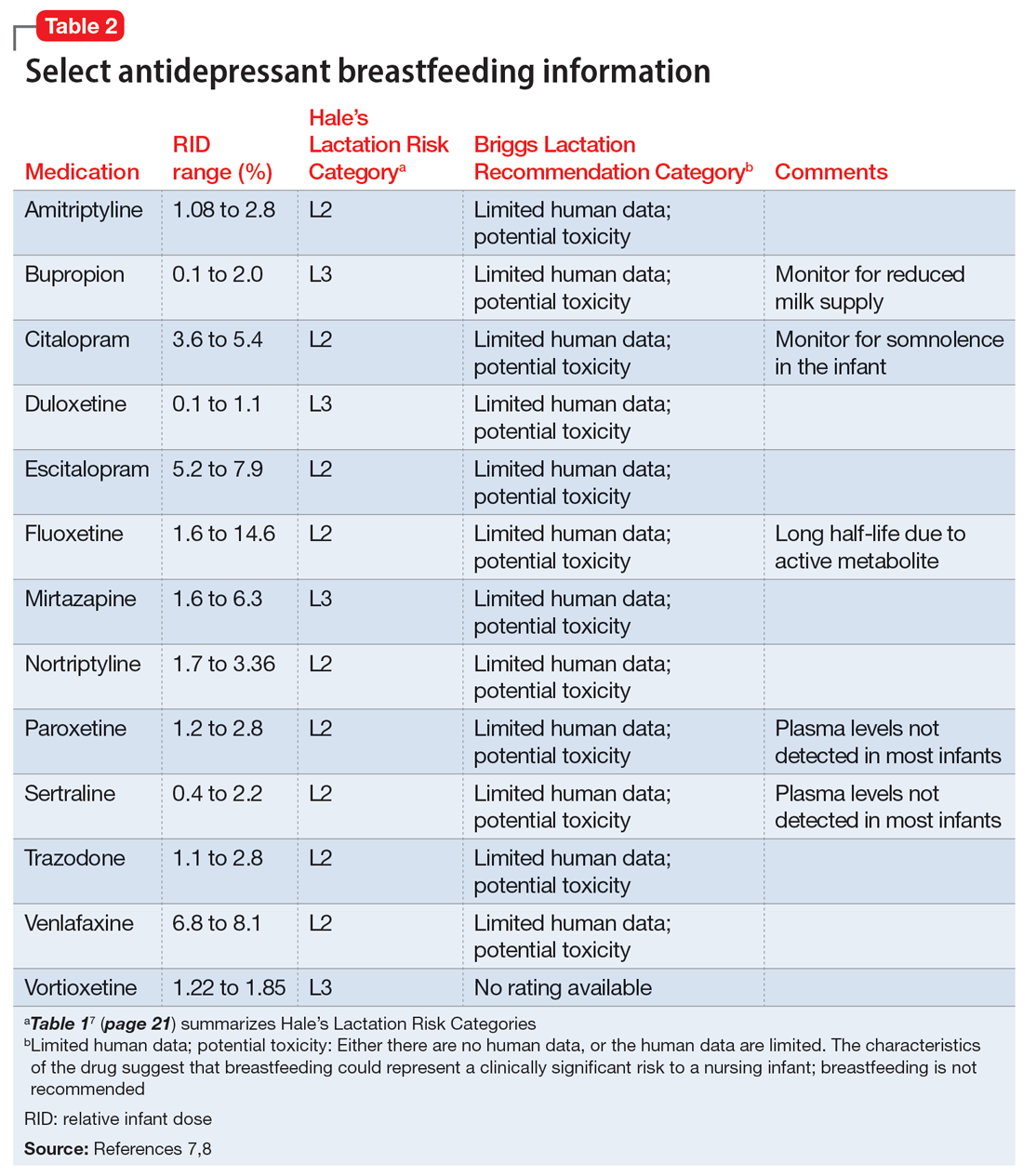

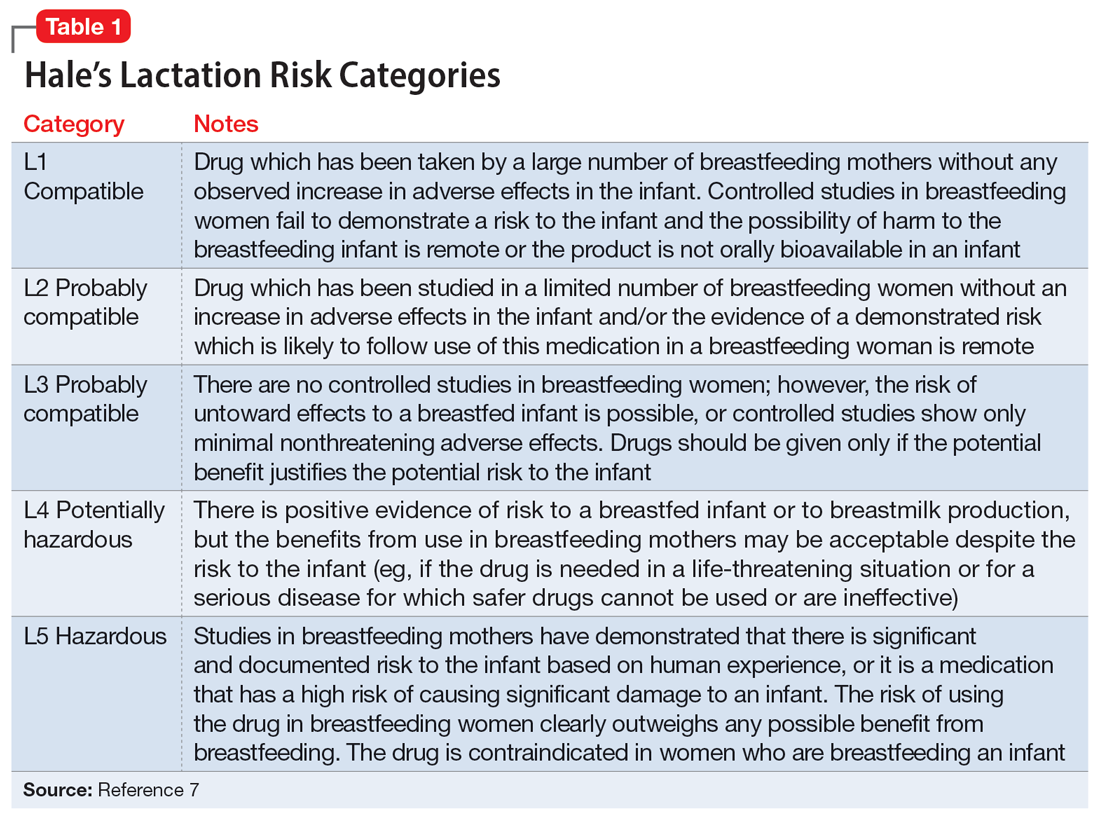

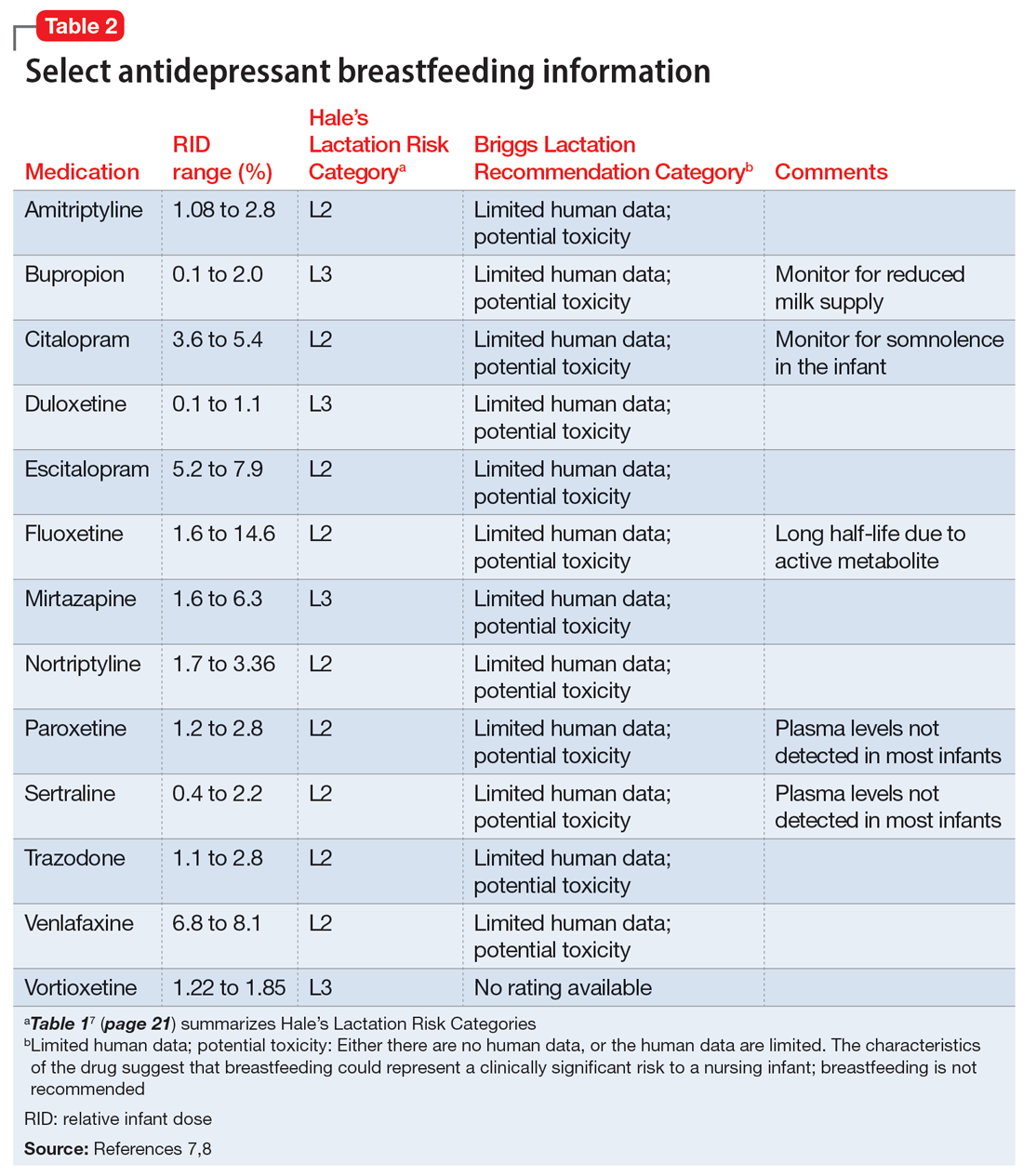

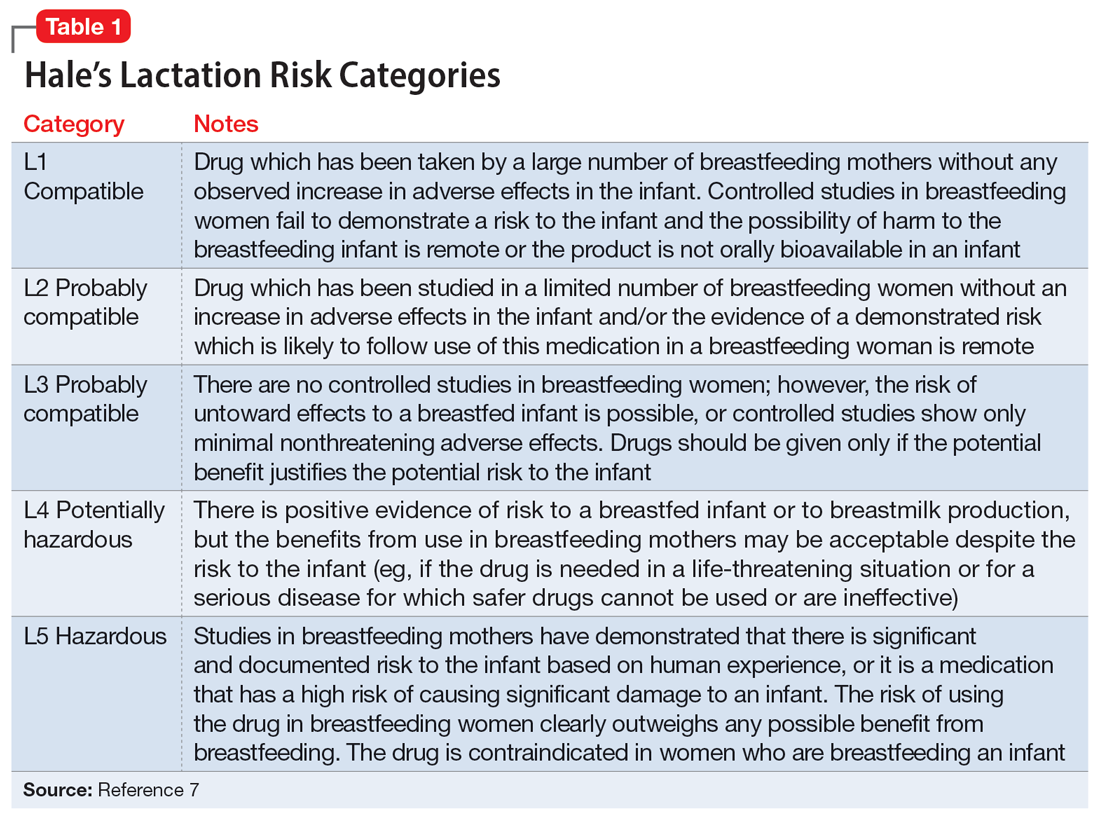

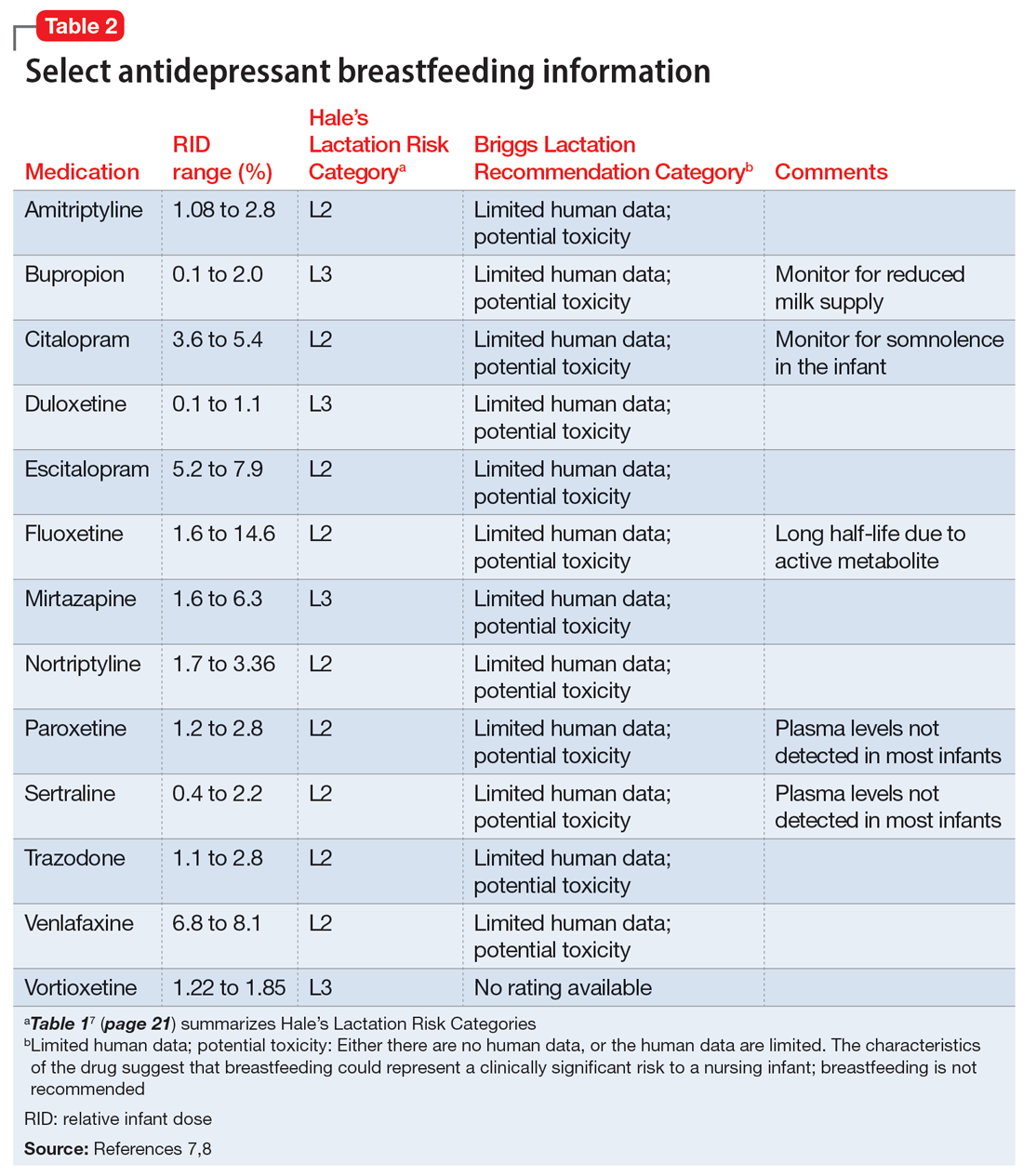

Several risk categorization systems are available, depending upon the resource used to obtain lactation information. One common system is Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories, with 5 safety levels ranging from L1 (breastfeeding compatible) to L5 (hazardous) (Table 17). Briggs et al8 utilize 7 categories to summarize recommendations ranging from breastfeeding-compatible to contraindicated; however, it is important to read the full medication monograph in the context of the rating provided. Table 27,8 provides breastfeeding information from Hale’s7 and from Briggs et al8 for some commonly used antidepressants.

In addition to interpreting available literature, it is also important to consider patient-specific factors, including (but not limited to) the severity of the patient’s psychiatric disorder and their previous response to medication. If a mother achieved remission on a particular antidepressant in the past, it may be preferable to restart that agent rather than trial a new medication.

CASE CONTINUED

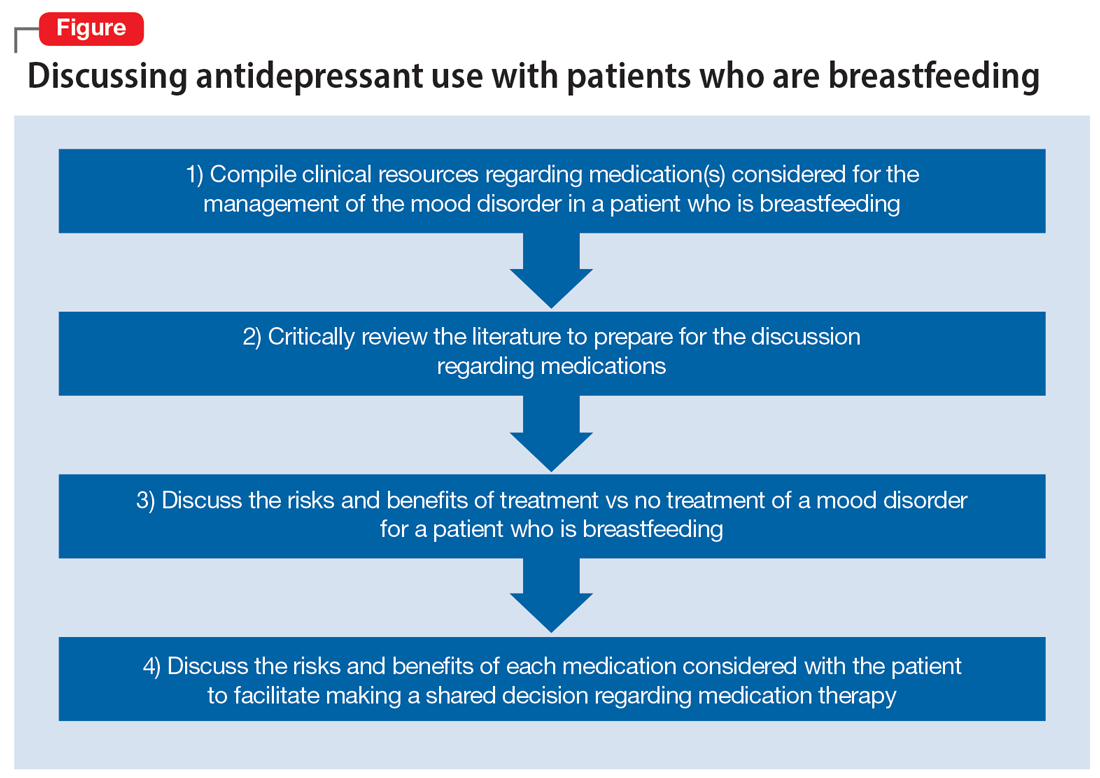

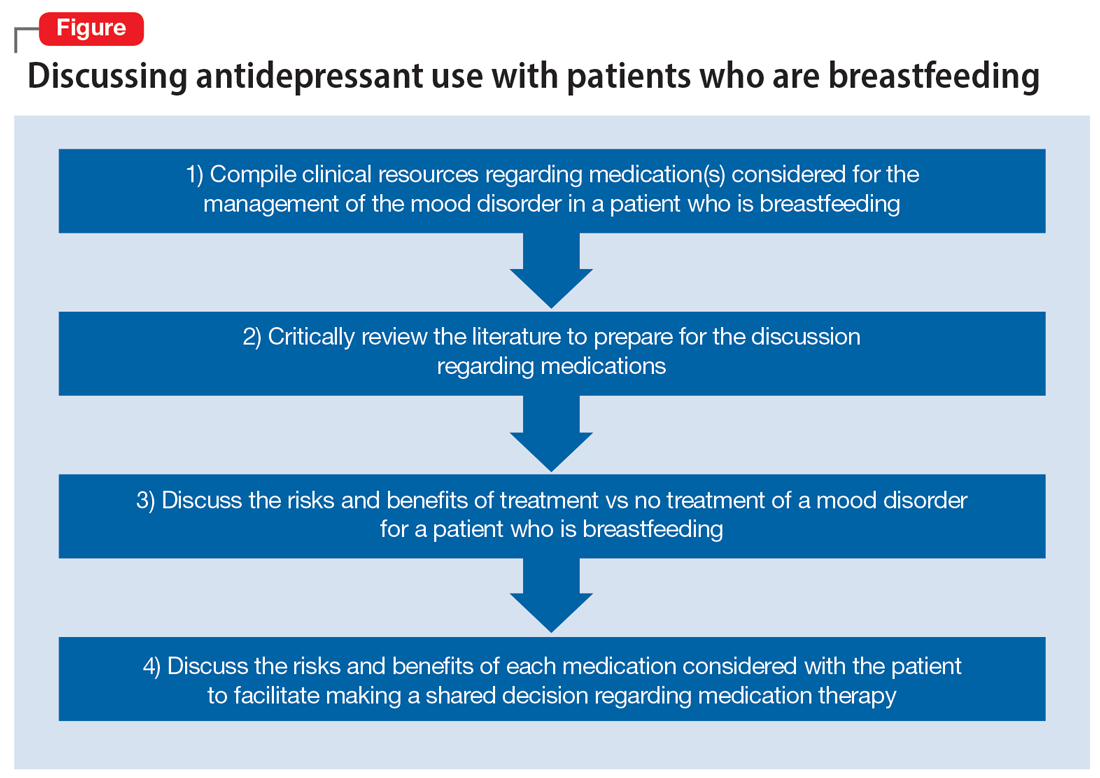

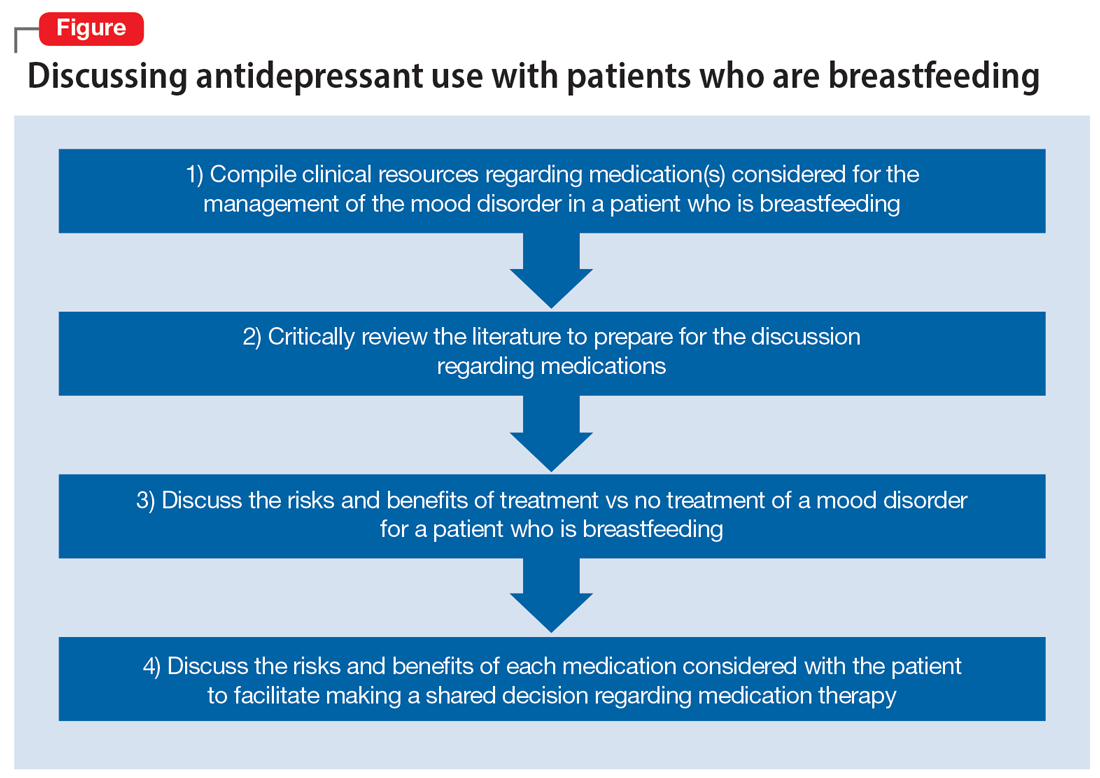

Two weeks later and following the use of a variety of resources, Ms. D’s treatment team finds that mirtazapine is rated Probably Compatible (L3 in Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories), with an M/P ratio of 0.76.7 The RID of mirtazapine ranges from 1.6% to 6.3%, and limited data from infants exposed to maternal use of mirtazapine during breastfeeding have not shown adverse effects.5 The treatment team administers the EDPS to Ms. D again and she scores 18. Given Ms. D’s previous remission with mirtazapine, current severity of depressive symptoms, and the risk/benefit assessment from lactation resources, the decision is made to restart mirtazapine 15 mg/d at bedtime with the option to titrate up if indicated. Ms. D plans to continue breastfeeding and will monitor for signs of any adverse effects in her infant. The Figure provides a summary of navigating this individualized decision with patients.

Related Resources

- MotherToBaby. Medication fact sheets, option to contact for no-charge consultation, free patient education information materials. www.mothertobaby.org

- Reprotox. Summaries on effects of medications on pregnancy, reproduction, and development (subscription required). www.reprotox.org

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Citalopram • Celexa

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Oleptro

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics calls for more support for breastfeeding mothers within updated policy recommendations. June 27, 2022. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/american-academy-of-pediatrics-calls-for-more-support-for-breastfeeding-mothers-within-updated-policy-recommendations

2. World Health Organization. Breastfeeding recommendations. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_2

3. Margiotta C, Gao J, O’Neil S, et al. The economic impact of untreated maternal mental health conditions in Texas. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):700. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-05001-6

4. Freeman MP, Farchione T, Yao L, et al. Psychiatric medications and reproductive safety: scientific and clinical perspectives pertaining to the US FDA pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(4):18ah38120.

5. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). National Library of Medicine (US); 2011. Updated April 18, 2016. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/

6. InfantRisk Center Resources. InfantRisk Center at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.infantrisk.com/infantrisk-center-resources

7. Hale TW, Krutsch K. Hale’s Medications and Mother’s Milk 2023: A Manual of Lactational Pharmacology. Springer Publishing; 2023.

8. Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Towers CV, et al. Briggs Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. 12th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2021.

Ms. D, age 32, recently gave birth to her second child. Her psychiatric history includes major depressive disorder. She had been stable on mirtazapine 30 mg at bedtime for 3 years. Based on clinical stability and patient preference, Ms. D elected to taper off mirtazapine 1 month prior to delivery. Now at 1 month postdelivery, Ms. D notes the reemergence of her depressive symptoms; during her child’s latest pediatrician visit, she scores 15 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). She breastfeeds her baby and wants more information on the safety of taking an antidepressant while breastfeeding.

Ms. D discusses her previous use of mirtazapine with her treatment team. The team reviews the available resources with Ms. D and together they plan to make a shared decision regarding treatment of her depression at her next appointment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics1 and World Health Organization2 recommend exclusive breastfeeding of infants for their first 6 months of life and support it as a complement to other foods through and beyond age 2. Untreated conditions such as postpartum depression impact maternal well-being and may interfere with parenting and child development. In fact, untreated maternal mental health leads to an increased risk of suicide, reduced maternal economic productivity, and worsened health for both mother and child.3

Because many women experience psychiatric symptoms before they become pregnant as well as during the perinatal period, questions often arise regardingthe use of psychiatric medications—specifically antidepressants—and their safety in patients who are breastfeeding. Key considerations regarding medication management should include the patient’s previous response to medications, the risks of untreated maternal mental illness, and evidence regarding risks and benefits in lactation. This article summarizes where to find evidence-based lactation information, how to interpret that information, and what information is available for select antidepressants.

Locating lactation information

Start by checking the manufacturer’s medication labeling (“prescribing information”) and medication information resources such as Micromedex (www.micromedexsolutions.com) and Lexicomp (www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/lexicomp). The updated labeling includes a risk/benefit assessment of available data on the risk for continued use of a medication during pregnancy compared to the risk if a medication is discontinued and the disorder goes untreated.4 The “breastfeeding considerations” section of medication labeling include details regarding the presence of the medication and the amount of it in breastmilk, adverse events in infants exposed to the medication through breastmilk, and additional pertinent data as applicable. Lexicomp includes information regarding breastfeeding considerations, and a subscription may also include access to Briggs Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation’s information pages. Micromedex includes its own lactation safety rating scale score.

Several other resources can help guide clinicians toward patient-specific recommendations. From the National Library of Medicine, LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/) allows clinicians to search for specific medications to see what information exists pertaining to medication levels in breastmilk and infant blood as well as potential adverse effects in the nursing infant and/or on lactation and breastmilk.5 LactMed provides information regarding alternative medications to consider and references from which the information was gathered.

Another helpful resource is the InfantRisk Center from Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, which includes a free call center for parents and clinicians who have questions about medications and breastfeeding (806-352-2519; Monday through Friday, 8

Continue to: How to interpret the information

How to interpret the information

Medication levels in breastmilk are affected by several properties, such as the medication’s molecular weight, protein binding, pKa, and volume of distribution. A few commonly used terms in lactation literature for medications include the relative infant dose (RID) and milk/plasma (M/P) ratio.

RID provides information about relative medication exposure for the infant. It is calculated by dividing the infant’s dose of a medication via breastmilk (mg/kg/d) by the mother’s dose (mg/kg/d).7 Most consider an RID <10% to be safe.7

M/P is the ratio of medication concentration in the mother’s milk divided by the medication concentration in the mother’s plasma. A ratio <1 is preferable and generally indicates that a low level of medication has been transferred to human milk.7

Another factor that can be evaluated is protein binding. Medications that are highly protein-bound do not tend to pass as easily into breastmilk and can minimize infant exposure.

Several risk categorization systems are available, depending upon the resource used to obtain lactation information. One common system is Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories, with 5 safety levels ranging from L1 (breastfeeding compatible) to L5 (hazardous) (Table 17). Briggs et al8 utilize 7 categories to summarize recommendations ranging from breastfeeding-compatible to contraindicated; however, it is important to read the full medication monograph in the context of the rating provided. Table 27,8 provides breastfeeding information from Hale’s7 and from Briggs et al8 for some commonly used antidepressants.

In addition to interpreting available literature, it is also important to consider patient-specific factors, including (but not limited to) the severity of the patient’s psychiatric disorder and their previous response to medication. If a mother achieved remission on a particular antidepressant in the past, it may be preferable to restart that agent rather than trial a new medication.

CASE CONTINUED

Two weeks later and following the use of a variety of resources, Ms. D’s treatment team finds that mirtazapine is rated Probably Compatible (L3 in Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories), with an M/P ratio of 0.76.7 The RID of mirtazapine ranges from 1.6% to 6.3%, and limited data from infants exposed to maternal use of mirtazapine during breastfeeding have not shown adverse effects.5 The treatment team administers the EDPS to Ms. D again and she scores 18. Given Ms. D’s previous remission with mirtazapine, current severity of depressive symptoms, and the risk/benefit assessment from lactation resources, the decision is made to restart mirtazapine 15 mg/d at bedtime with the option to titrate up if indicated. Ms. D plans to continue breastfeeding and will monitor for signs of any adverse effects in her infant. The Figure provides a summary of navigating this individualized decision with patients.

Related Resources

- MotherToBaby. Medication fact sheets, option to contact for no-charge consultation, free patient education information materials. www.mothertobaby.org

- Reprotox. Summaries on effects of medications on pregnancy, reproduction, and development (subscription required). www.reprotox.org

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Citalopram • Celexa

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Oleptro

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Ms. D, age 32, recently gave birth to her second child. Her psychiatric history includes major depressive disorder. She had been stable on mirtazapine 30 mg at bedtime for 3 years. Based on clinical stability and patient preference, Ms. D elected to taper off mirtazapine 1 month prior to delivery. Now at 1 month postdelivery, Ms. D notes the reemergence of her depressive symptoms; during her child’s latest pediatrician visit, she scores 15 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). She breastfeeds her baby and wants more information on the safety of taking an antidepressant while breastfeeding.

Ms. D discusses her previous use of mirtazapine with her treatment team. The team reviews the available resources with Ms. D and together they plan to make a shared decision regarding treatment of her depression at her next appointment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics1 and World Health Organization2 recommend exclusive breastfeeding of infants for their first 6 months of life and support it as a complement to other foods through and beyond age 2. Untreated conditions such as postpartum depression impact maternal well-being and may interfere with parenting and child development. In fact, untreated maternal mental health leads to an increased risk of suicide, reduced maternal economic productivity, and worsened health for both mother and child.3

Because many women experience psychiatric symptoms before they become pregnant as well as during the perinatal period, questions often arise regardingthe use of psychiatric medications—specifically antidepressants—and their safety in patients who are breastfeeding. Key considerations regarding medication management should include the patient’s previous response to medications, the risks of untreated maternal mental illness, and evidence regarding risks and benefits in lactation. This article summarizes where to find evidence-based lactation information, how to interpret that information, and what information is available for select antidepressants.

Locating lactation information

Start by checking the manufacturer’s medication labeling (“prescribing information”) and medication information resources such as Micromedex (www.micromedexsolutions.com) and Lexicomp (www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/lexicomp). The updated labeling includes a risk/benefit assessment of available data on the risk for continued use of a medication during pregnancy compared to the risk if a medication is discontinued and the disorder goes untreated.4 The “breastfeeding considerations” section of medication labeling include details regarding the presence of the medication and the amount of it in breastmilk, adverse events in infants exposed to the medication through breastmilk, and additional pertinent data as applicable. Lexicomp includes information regarding breastfeeding considerations, and a subscription may also include access to Briggs Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation’s information pages. Micromedex includes its own lactation safety rating scale score.

Several other resources can help guide clinicians toward patient-specific recommendations. From the National Library of Medicine, LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/) allows clinicians to search for specific medications to see what information exists pertaining to medication levels in breastmilk and infant blood as well as potential adverse effects in the nursing infant and/or on lactation and breastmilk.5 LactMed provides information regarding alternative medications to consider and references from which the information was gathered.

Another helpful resource is the InfantRisk Center from Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, which includes a free call center for parents and clinicians who have questions about medications and breastfeeding (806-352-2519; Monday through Friday, 8

Continue to: How to interpret the information

How to interpret the information

Medication levels in breastmilk are affected by several properties, such as the medication’s molecular weight, protein binding, pKa, and volume of distribution. A few commonly used terms in lactation literature for medications include the relative infant dose (RID) and milk/plasma (M/P) ratio.

RID provides information about relative medication exposure for the infant. It is calculated by dividing the infant’s dose of a medication via breastmilk (mg/kg/d) by the mother’s dose (mg/kg/d).7 Most consider an RID <10% to be safe.7

M/P is the ratio of medication concentration in the mother’s milk divided by the medication concentration in the mother’s plasma. A ratio <1 is preferable and generally indicates that a low level of medication has been transferred to human milk.7

Another factor that can be evaluated is protein binding. Medications that are highly protein-bound do not tend to pass as easily into breastmilk and can minimize infant exposure.

Several risk categorization systems are available, depending upon the resource used to obtain lactation information. One common system is Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories, with 5 safety levels ranging from L1 (breastfeeding compatible) to L5 (hazardous) (Table 17). Briggs et al8 utilize 7 categories to summarize recommendations ranging from breastfeeding-compatible to contraindicated; however, it is important to read the full medication monograph in the context of the rating provided. Table 27,8 provides breastfeeding information from Hale’s7 and from Briggs et al8 for some commonly used antidepressants.

In addition to interpreting available literature, it is also important to consider patient-specific factors, including (but not limited to) the severity of the patient’s psychiatric disorder and their previous response to medication. If a mother achieved remission on a particular antidepressant in the past, it may be preferable to restart that agent rather than trial a new medication.

CASE CONTINUED

Two weeks later and following the use of a variety of resources, Ms. D’s treatment team finds that mirtazapine is rated Probably Compatible (L3 in Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories), with an M/P ratio of 0.76.7 The RID of mirtazapine ranges from 1.6% to 6.3%, and limited data from infants exposed to maternal use of mirtazapine during breastfeeding have not shown adverse effects.5 The treatment team administers the EDPS to Ms. D again and she scores 18. Given Ms. D’s previous remission with mirtazapine, current severity of depressive symptoms, and the risk/benefit assessment from lactation resources, the decision is made to restart mirtazapine 15 mg/d at bedtime with the option to titrate up if indicated. Ms. D plans to continue breastfeeding and will monitor for signs of any adverse effects in her infant. The Figure provides a summary of navigating this individualized decision with patients.

Related Resources

- MotherToBaby. Medication fact sheets, option to contact for no-charge consultation, free patient education information materials. www.mothertobaby.org

- Reprotox. Summaries on effects of medications on pregnancy, reproduction, and development (subscription required). www.reprotox.org

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Citalopram • Celexa

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Oleptro

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics calls for more support for breastfeeding mothers within updated policy recommendations. June 27, 2022. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/american-academy-of-pediatrics-calls-for-more-support-for-breastfeeding-mothers-within-updated-policy-recommendations

2. World Health Organization. Breastfeeding recommendations. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_2

3. Margiotta C, Gao J, O’Neil S, et al. The economic impact of untreated maternal mental health conditions in Texas. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):700. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-05001-6

4. Freeman MP, Farchione T, Yao L, et al. Psychiatric medications and reproductive safety: scientific and clinical perspectives pertaining to the US FDA pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(4):18ah38120.

5. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). National Library of Medicine (US); 2011. Updated April 18, 2016. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/

6. InfantRisk Center Resources. InfantRisk Center at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.infantrisk.com/infantrisk-center-resources

7. Hale TW, Krutsch K. Hale’s Medications and Mother’s Milk 2023: A Manual of Lactational Pharmacology. Springer Publishing; 2023.

8. Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Towers CV, et al. Briggs Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. 12th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2021.

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics calls for more support for breastfeeding mothers within updated policy recommendations. June 27, 2022. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/american-academy-of-pediatrics-calls-for-more-support-for-breastfeeding-mothers-within-updated-policy-recommendations

2. World Health Organization. Breastfeeding recommendations. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_2

3. Margiotta C, Gao J, O’Neil S, et al. The economic impact of untreated maternal mental health conditions in Texas. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):700. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-05001-6

4. Freeman MP, Farchione T, Yao L, et al. Psychiatric medications and reproductive safety: scientific and clinical perspectives pertaining to the US FDA pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(4):18ah38120.

5. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). National Library of Medicine (US); 2011. Updated April 18, 2016. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/

6. InfantRisk Center Resources. InfantRisk Center at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.infantrisk.com/infantrisk-center-resources

7. Hale TW, Krutsch K. Hale’s Medications and Mother’s Milk 2023: A Manual of Lactational Pharmacology. Springer Publishing; 2023.

8. Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Towers CV, et al. Briggs Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. 12th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2021.