User login

SAN FRANCISCO – Gastroenterology might be the proving ground of one of medicine’s boldest new ventures – the creation of fully functional human organs built with a 3-D printer.

Gut is a perfect beginning project, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 AGA Tech Summit, which is sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one. Even then, there is no guarantee that the selected organ will function as it should. Rejection is always a concern. Immunosuppression is a lifelong challenge.

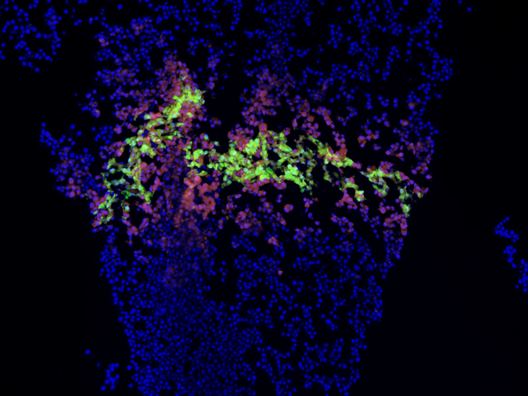

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The logical leap between dish and transplant is likely to be some sort of nonformed “piggyback liver,” which could be used as a bridge to keep liver failure patients alive until a traditional donor organ is found, Dr. Geibel said.

The Holy Grail, of course, would be a transplantable organ, created from the patient’s own cells – a made-to-order liver that’s 100% compatible with the recipient, who is actually also the donor.

“Think of the difference in quality of life these could make for patients who need transplants. The possibility of living without the fear of organ rejection, without the need for lifelong immunosuppression. Without the fear of having no alternative if the organ didn’t function well, or failed. If it did, we could simply grow another and try again.”

SAN FRANCISCO – Gastroenterology might be the proving ground of one of medicine’s boldest new ventures – the creation of fully functional human organs built with a 3-D printer.

Gut is a perfect beginning project, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 AGA Tech Summit, which is sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one. Even then, there is no guarantee that the selected organ will function as it should. Rejection is always a concern. Immunosuppression is a lifelong challenge.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The logical leap between dish and transplant is likely to be some sort of nonformed “piggyback liver,” which could be used as a bridge to keep liver failure patients alive until a traditional donor organ is found, Dr. Geibel said.

The Holy Grail, of course, would be a transplantable organ, created from the patient’s own cells – a made-to-order liver that’s 100% compatible with the recipient, who is actually also the donor.

“Think of the difference in quality of life these could make for patients who need transplants. The possibility of living without the fear of organ rejection, without the need for lifelong immunosuppression. Without the fear of having no alternative if the organ didn’t function well, or failed. If it did, we could simply grow another and try again.”

SAN FRANCISCO – Gastroenterology might be the proving ground of one of medicine’s boldest new ventures – the creation of fully functional human organs built with a 3-D printer.

Gut is a perfect beginning project, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 AGA Tech Summit, which is sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one. Even then, there is no guarantee that the selected organ will function as it should. Rejection is always a concern. Immunosuppression is a lifelong challenge.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The logical leap between dish and transplant is likely to be some sort of nonformed “piggyback liver,” which could be used as a bridge to keep liver failure patients alive until a traditional donor organ is found, Dr. Geibel said.

The Holy Grail, of course, would be a transplantable organ, created from the patient’s own cells – a made-to-order liver that’s 100% compatible with the recipient, who is actually also the donor.

“Think of the difference in quality of life these could make for patients who need transplants. The possibility of living without the fear of organ rejection, without the need for lifelong immunosuppression. Without the fear of having no alternative if the organ didn’t function well, or failed. If it did, we could simply grow another and try again.”

AT THE 2015 AGA TECH SUMMIT