User login

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series examining bundled payments and hospital medicine. In full disclosure, Dr. Whitcomb works for a company that is an Awardee Convener in the CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative.

In part one of this series, we discussed the basics of the BPCI program. Now we will delve into specific roles and opportunities for hospitalists in bundled payment programs in general, and the BPCI program in particular.

The bundled payment model can be hard to explain. One example that might make it clearer is that of LASIK vision correction surgery, where a single bundled payment covers the fees of the ophthalmologist, the operating facility, and any other services (like optometry) and medications (like eye drops). Another example is the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for hospital care, in which all facility costs are bundled together into a single payment.

A simplistic way to differentiate bundled payment from accountable care organization (ACOs) is that the former is typically initiated by an acute medical or surgical event and concludes after a recovery period—often 30, 60, or 90 days. Conversely, the latter generally covers the care of individuals within a population over time, often focusing on the management of chronic conditions.

The Opportunity

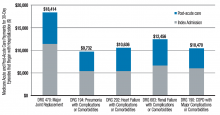

Two major opportunities for hospitalists to improve value (quality/cost) present themselves through the BPCI initiative. One is in post-acute facility utilization, and the other is in reducing readmissions. Figure 1 shows that for 30-day episodes starting with a hospitalization for five common conditions, payments for post-acute care are surprisingly close in amount to those for the preceding hospitalization.1

Much of the cost of post-acute care comes from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and, to a lesser degree, inpatient rehabilitation facilities. A broad range of research studies has demonstrated that inpatient care managed by hospitalists—compared with the traditional model—is associated with a decrease in inpatient costs; however, recent research indicates that the hospital cost savings generated by hospitalists are offset by more spending in the 30 days post discharge, specifically on more SNF care and increased readmissions.2 As another indicator that post-acute care needs a closer look, a 2013 Institute of Medicine report concluded that spending on post-acute care was responsible for the majority of Medicare’s overall regional variation in spending.1,3

Of course, success in a bundled payment model will also be derived from reducing costs in the hospital setting, such as those stemming from unnecessary or duplicative testing and imaging, injudicious use of consultants, and practices identified in programs such as Choosing Wisely.

How Your Practice Can Drive Bundled Payment Success

The aforementioned observations point to the need to improve the value of post-acute care by optimizing post-acute spending—driven mostly by SNF costs—and minimizing avoidable readmissions. I offer the following inpatient interventions to achieve these goals:

- Speak with patients early and often regarding expectations for recovery post discharge. When possible, set a goal of home discharge with the needed support.

- Write orders for early ambulation. Develop an early ambulation program with nursing and physical therapy.

- Address goals of care during the patient/family meeting. For appropriate patients with life-limiting illness, involve the palliative care service or equivalent and discuss the role of future aggressive interventions, including hospitalization, so that the course set is consistent with the patients’ goals and wishes.

- Lead the in-hospital team, instead of defaulting to others, like case management, in making an informed decision about ideal post-discharge location by factoring in caregiver availability, independence, and SNF needs. Marshal resources to enable a home recovery (i.e., home health evaluation), whether or not there is an intervening SNF stay. If patients go to a SNF, set expectations for length of stay in the facility.

- Adhere to best practices for care transitions, such as those in Project BOOST, including thorough medication reconciliation.

Beyond the Four Walls

As you aim for a high-value (high quality and affordable) discharge, your hospital medicine practice may consider new approaches to filling longstanding gaps in post-acute care. Forward-looking hospitalist groups have implemented the following approaches:

- Establish a post-discharge clinic where patients are seen after discharge, in the interim before they have an opportunity for primary care follow-up;

- Send teams to work in SNFs;

- Call patients after discharge to ensure they are following their plan of care;

- Leverage newer current procedural terminology (CPT) codes, like the Transitional Care Management or Chronic Care Management codes, to support your transitional care services;

- Provide home visits for high-risk patients; and

- Access waivers for G-codes for home visits and/or telemedicine outside of rural areas. These waivers exist under the BPCI initiative.

Shift from ‘Traditional’ Hospitalist to ‘Value’ Hospitalist

If some of the changes in practice needed to succeed in a bundled payment world seem daunting to you, it may be helpful to realize that with the challenge comes an opportunity. This opportunity for hospitalists parallels that of the early days of the specialty, when reducing length of stay created substantial support from hospital leaders and was a factor leading to the rapid growth in the number of hospitalists. In January, the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services set a goal to tie 50% of Medicare payments to ‘alternative payment models’ like bundled payments by 2018. In April, as part of the sustainable growth rate fix, Medicare announced it would create substantial new bonuses for physicians who have at least 25% of their revenue in such models.1

As healthcare policy aligns behind ‘alternative payment models,’ bundled payment programs are likely to be a potent driver of an evolving hospitalist specialty. Next-generation hospitalists will be asked to take a leadership role in addressing ‘value’ with responsibility for improving care coordination and affordability over an episode of illness.

Now may be the time to take to heart the words of computer scientist Alan Kay: “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

References

- Mechanic R. Post-acute care–the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):692-694.

- Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):152-159.

- Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in Medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1465-1468.

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series examining bundled payments and hospital medicine. In full disclosure, Dr. Whitcomb works for a company that is an Awardee Convener in the CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative.

In part one of this series, we discussed the basics of the BPCI program. Now we will delve into specific roles and opportunities for hospitalists in bundled payment programs in general, and the BPCI program in particular.

The bundled payment model can be hard to explain. One example that might make it clearer is that of LASIK vision correction surgery, where a single bundled payment covers the fees of the ophthalmologist, the operating facility, and any other services (like optometry) and medications (like eye drops). Another example is the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for hospital care, in which all facility costs are bundled together into a single payment.

A simplistic way to differentiate bundled payment from accountable care organization (ACOs) is that the former is typically initiated by an acute medical or surgical event and concludes after a recovery period—often 30, 60, or 90 days. Conversely, the latter generally covers the care of individuals within a population over time, often focusing on the management of chronic conditions.

The Opportunity

Two major opportunities for hospitalists to improve value (quality/cost) present themselves through the BPCI initiative. One is in post-acute facility utilization, and the other is in reducing readmissions. Figure 1 shows that for 30-day episodes starting with a hospitalization for five common conditions, payments for post-acute care are surprisingly close in amount to those for the preceding hospitalization.1

Much of the cost of post-acute care comes from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and, to a lesser degree, inpatient rehabilitation facilities. A broad range of research studies has demonstrated that inpatient care managed by hospitalists—compared with the traditional model—is associated with a decrease in inpatient costs; however, recent research indicates that the hospital cost savings generated by hospitalists are offset by more spending in the 30 days post discharge, specifically on more SNF care and increased readmissions.2 As another indicator that post-acute care needs a closer look, a 2013 Institute of Medicine report concluded that spending on post-acute care was responsible for the majority of Medicare’s overall regional variation in spending.1,3

Of course, success in a bundled payment model will also be derived from reducing costs in the hospital setting, such as those stemming from unnecessary or duplicative testing and imaging, injudicious use of consultants, and practices identified in programs such as Choosing Wisely.

How Your Practice Can Drive Bundled Payment Success

The aforementioned observations point to the need to improve the value of post-acute care by optimizing post-acute spending—driven mostly by SNF costs—and minimizing avoidable readmissions. I offer the following inpatient interventions to achieve these goals:

- Speak with patients early and often regarding expectations for recovery post discharge. When possible, set a goal of home discharge with the needed support.

- Write orders for early ambulation. Develop an early ambulation program with nursing and physical therapy.

- Address goals of care during the patient/family meeting. For appropriate patients with life-limiting illness, involve the palliative care service or equivalent and discuss the role of future aggressive interventions, including hospitalization, so that the course set is consistent with the patients’ goals and wishes.

- Lead the in-hospital team, instead of defaulting to others, like case management, in making an informed decision about ideal post-discharge location by factoring in caregiver availability, independence, and SNF needs. Marshal resources to enable a home recovery (i.e., home health evaluation), whether or not there is an intervening SNF stay. If patients go to a SNF, set expectations for length of stay in the facility.

- Adhere to best practices for care transitions, such as those in Project BOOST, including thorough medication reconciliation.

Beyond the Four Walls

As you aim for a high-value (high quality and affordable) discharge, your hospital medicine practice may consider new approaches to filling longstanding gaps in post-acute care. Forward-looking hospitalist groups have implemented the following approaches:

- Establish a post-discharge clinic where patients are seen after discharge, in the interim before they have an opportunity for primary care follow-up;

- Send teams to work in SNFs;

- Call patients after discharge to ensure they are following their plan of care;

- Leverage newer current procedural terminology (CPT) codes, like the Transitional Care Management or Chronic Care Management codes, to support your transitional care services;

- Provide home visits for high-risk patients; and

- Access waivers for G-codes for home visits and/or telemedicine outside of rural areas. These waivers exist under the BPCI initiative.

Shift from ‘Traditional’ Hospitalist to ‘Value’ Hospitalist

If some of the changes in practice needed to succeed in a bundled payment world seem daunting to you, it may be helpful to realize that with the challenge comes an opportunity. This opportunity for hospitalists parallels that of the early days of the specialty, when reducing length of stay created substantial support from hospital leaders and was a factor leading to the rapid growth in the number of hospitalists. In January, the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services set a goal to tie 50% of Medicare payments to ‘alternative payment models’ like bundled payments by 2018. In April, as part of the sustainable growth rate fix, Medicare announced it would create substantial new bonuses for physicians who have at least 25% of their revenue in such models.1

As healthcare policy aligns behind ‘alternative payment models,’ bundled payment programs are likely to be a potent driver of an evolving hospitalist specialty. Next-generation hospitalists will be asked to take a leadership role in addressing ‘value’ with responsibility for improving care coordination and affordability over an episode of illness.

Now may be the time to take to heart the words of computer scientist Alan Kay: “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

References

- Mechanic R. Post-acute care–the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):692-694.

- Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):152-159.

- Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in Medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1465-1468.

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series examining bundled payments and hospital medicine. In full disclosure, Dr. Whitcomb works for a company that is an Awardee Convener in the CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative.

In part one of this series, we discussed the basics of the BPCI program. Now we will delve into specific roles and opportunities for hospitalists in bundled payment programs in general, and the BPCI program in particular.

The bundled payment model can be hard to explain. One example that might make it clearer is that of LASIK vision correction surgery, where a single bundled payment covers the fees of the ophthalmologist, the operating facility, and any other services (like optometry) and medications (like eye drops). Another example is the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for hospital care, in which all facility costs are bundled together into a single payment.

A simplistic way to differentiate bundled payment from accountable care organization (ACOs) is that the former is typically initiated by an acute medical or surgical event and concludes after a recovery period—often 30, 60, or 90 days. Conversely, the latter generally covers the care of individuals within a population over time, often focusing on the management of chronic conditions.

The Opportunity

Two major opportunities for hospitalists to improve value (quality/cost) present themselves through the BPCI initiative. One is in post-acute facility utilization, and the other is in reducing readmissions. Figure 1 shows that for 30-day episodes starting with a hospitalization for five common conditions, payments for post-acute care are surprisingly close in amount to those for the preceding hospitalization.1

Much of the cost of post-acute care comes from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and, to a lesser degree, inpatient rehabilitation facilities. A broad range of research studies has demonstrated that inpatient care managed by hospitalists—compared with the traditional model—is associated with a decrease in inpatient costs; however, recent research indicates that the hospital cost savings generated by hospitalists are offset by more spending in the 30 days post discharge, specifically on more SNF care and increased readmissions.2 As another indicator that post-acute care needs a closer look, a 2013 Institute of Medicine report concluded that spending on post-acute care was responsible for the majority of Medicare’s overall regional variation in spending.1,3

Of course, success in a bundled payment model will also be derived from reducing costs in the hospital setting, such as those stemming from unnecessary or duplicative testing and imaging, injudicious use of consultants, and practices identified in programs such as Choosing Wisely.

How Your Practice Can Drive Bundled Payment Success

The aforementioned observations point to the need to improve the value of post-acute care by optimizing post-acute spending—driven mostly by SNF costs—and minimizing avoidable readmissions. I offer the following inpatient interventions to achieve these goals:

- Speak with patients early and often regarding expectations for recovery post discharge. When possible, set a goal of home discharge with the needed support.

- Write orders for early ambulation. Develop an early ambulation program with nursing and physical therapy.

- Address goals of care during the patient/family meeting. For appropriate patients with life-limiting illness, involve the palliative care service or equivalent and discuss the role of future aggressive interventions, including hospitalization, so that the course set is consistent with the patients’ goals and wishes.

- Lead the in-hospital team, instead of defaulting to others, like case management, in making an informed decision about ideal post-discharge location by factoring in caregiver availability, independence, and SNF needs. Marshal resources to enable a home recovery (i.e., home health evaluation), whether or not there is an intervening SNF stay. If patients go to a SNF, set expectations for length of stay in the facility.

- Adhere to best practices for care transitions, such as those in Project BOOST, including thorough medication reconciliation.

Beyond the Four Walls

As you aim for a high-value (high quality and affordable) discharge, your hospital medicine practice may consider new approaches to filling longstanding gaps in post-acute care. Forward-looking hospitalist groups have implemented the following approaches:

- Establish a post-discharge clinic where patients are seen after discharge, in the interim before they have an opportunity for primary care follow-up;

- Send teams to work in SNFs;

- Call patients after discharge to ensure they are following their plan of care;

- Leverage newer current procedural terminology (CPT) codes, like the Transitional Care Management or Chronic Care Management codes, to support your transitional care services;

- Provide home visits for high-risk patients; and

- Access waivers for G-codes for home visits and/or telemedicine outside of rural areas. These waivers exist under the BPCI initiative.

Shift from ‘Traditional’ Hospitalist to ‘Value’ Hospitalist

If some of the changes in practice needed to succeed in a bundled payment world seem daunting to you, it may be helpful to realize that with the challenge comes an opportunity. This opportunity for hospitalists parallels that of the early days of the specialty, when reducing length of stay created substantial support from hospital leaders and was a factor leading to the rapid growth in the number of hospitalists. In January, the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services set a goal to tie 50% of Medicare payments to ‘alternative payment models’ like bundled payments by 2018. In April, as part of the sustainable growth rate fix, Medicare announced it would create substantial new bonuses for physicians who have at least 25% of their revenue in such models.1

As healthcare policy aligns behind ‘alternative payment models,’ bundled payment programs are likely to be a potent driver of an evolving hospitalist specialty. Next-generation hospitalists will be asked to take a leadership role in addressing ‘value’ with responsibility for improving care coordination and affordability over an episode of illness.

Now may be the time to take to heart the words of computer scientist Alan Kay: “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

References

- Mechanic R. Post-acute care–the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):692-694.

- Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):152-159.

- Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in Medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1465-1468.