User login

“Mr. Smith seems somewhat confused today” is one of the most serious and concerning pre-visit reports you can receive from your staff or the patient’s family. Such a descriptor can be confusing—pardon the pun—not only for the patient, but to even seasoned mental health providers.

The term confusion can be code for diagnoses ranging from deliriuma to a progressive neurocognitive disorder (NCD) such as major NCD due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or even a more challenging problem such as beclouded dementia (delirium superimposed on dementia/NCD). It is essential for all mental health professionals to have an evidence-based approach when encountering signs or symptoms of confusion.

aICD-10 code R41.0 encompasses Confusion, Other Specified Delirium, or Unspecified Delirium.

CASE REPORT

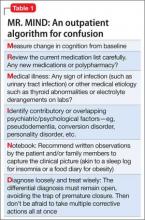

Ms. T, age 62, has hypothyroidism and bipolar I disorder, most recently depressed, with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. She has been taking lithium, 600 mg/d, to control her mood symptoms. Her daughter-in-law reports that Ms. T has been exhibiting increasing signs of confusion. During the office evaluation, Ms. T minimizes her symptoms, only describing mild issues with forgetfulness while cooking and concern over increasing anxiety. Her daughter-in-law plays a voicemail message from earlier in the week, in which Ms. T’s speech is halting, disorganized, and in a word, confused. I decide to use the mnemonic decision chart MR. MIND (Table 1) to get to the bottom of her recent confusion.

Measure cognition

It is nice to receive advanced warning about a cognitive change or a change in activities of daily living; however, many patients present with subtle, sub-acute changes that are more difficult to assess. When encountering a broad symptom such as “confusion”—which has an equally broad differential diagnosis—systematic assessment of the current cognitive state compared with the patient’s baseline becomes the first order of business. However, this requires that the patient has had a baseline cognitive assessment.

In my practice, I often administer one of the validated neurocognitive screening instruments when a patient first begins care—even a brief test such as the Mini- Cog (3-item recall plus clock drawing test), which is comparable to longer screening tests at least for NCD/dementia.1 During a presentation for confusion, a more detailed neurocognitive assessment instrument would be recommended, allowing one to marry the clinical impression with a validated, objective measure. Formal neuropsychological testing by a clinical neuropsychologist is the gold standard, but such testing is time-consuming and expensive and often not readily available. The screening instrument I use for a more thorough evaluation depends on the clinical scenario.

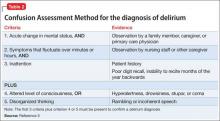

The Six-Item Screener is used in some emergency settings because it is short but boasts a higher sensitivity than the Mini- Cog (94% vs 75%) with similar specificity when screening for cognitive impairment.2 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a valuable instrument, although, recently, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination has been thought to be better at detecting mild NCD than the MMSE; more data are needed to substantiate this claim.3 The Montreal Cognitive Assessment is another validated screening tool that has been shown to be superior to the MMSE in terms of screening for mild cognitive impairment.4 The best delirium-specific assessment tool is the Confusion Assessment Method (Table 2).5

Ms. T’s MMSE score was 26/30, down from 29/30 at baseline. Her score fell below the cutoff score of 27 for mild cognitive impairment for someone with at least 8 years of completed education. Her results were abnormal mainly in the memory domain (3-item recall), raising the question of a possible prodromal state of AD although the acute nature of the change made delirium or mild NCD high in the differential.

Review medications

A review of the medication list is not just a Joint Commission mandate (medication reconciliation during each encounter) but is important whenever confusion is noted. Polypharmacy can be a concern, but is not as concerning as the class of medication prescribed, particularly anticholinergic and sedative medications in patients age >65. The Drug Burden Index can be helpful in assessing this risk.6 Medications such as the benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, tricyclic antidepressants, and antipsychotics should be discontinued if possible, keeping in mind that the addition or subtraction of medications must be done prudently and only after reviewing the evidence and in consultation with the patient. A detailed medication review is as important for confused outpatients as it is for an inpatient case (steps 2 and 3 of the inpatient algorithm outlined in Table 3).7

In Ms. T’s case, the primary concern on her medication list was that her medical team was prescribing levothyroxine, 112 mcg/d, and desiccated thyroid (combination thyroxine and triiodothyronine in the form of 20 mg Armour Thyroid), despite a lack of data for such combination therapy. Earlier, I had discontinued lorazepam, leaving lithium, 600 mg/d, quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d, as her remaining psychotropics. Her other medications included atorvastatin, 40 mg/d, for hyper-lipidemia and metformin, 750 mg/d, for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Medical illness

An organic basis must rank high in the differential diagnosis if medications are not the culprit. There are myriad medical disorders that can lead to confusion (Table 4).8 In an outpatient psychiatric setting, laboratory and radiology testing might not be readily available. It then becomes important to collaborate with a patient’s medical team if any of the following are met:

•there is high suspicion of a medical cause

•there could be delays in performing a medical workup

•a physical examination is needed.

Laboratory work-up should include:

•comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) to assess for electrolyte derangements and liver or kidney disease

•urinalysis if there are signs of urinary tract infection (low threshold for testing in patients age >65 even if they are asymptomatic)

•urine drug screen or serum alcohol level if substance use is suspected

•complete blood count (CBC) if there are reports of infection (white blood cell count) or blood loss/bruising to ensure that anemia or thrombocytopenia is not playing a role

•thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) because thyroid disorders can cause neuropsychiatric as well as somatic symptoms.9

Other laboratory testing could be valuable depending on the clinical scenario. These include tests such as:

•drug level monitoring (lithium, valproic acid, etc.) to assess for toxicity

•HIV and rapid plasma reagin for suspected sexually transmitted infections

•vitamin levels in patients with poor nutrition or post bariatric surgery

•erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, or both, if there are signs of inflammation

•bacterial culture if blood or tissue infection is a concern.

Esoteric tests include ceruloplasmin (Wilson’s disease), heavy metals screen, and even tests such as anti-gliadin antibodies because the prevalence of gluten sensitivity and celiac disease appear to be on the rise and have been associated with neuropsychiatric problems including encephalopathy.10

Brain imaging is an important consideration when a medical differential diagnosis for confusion is formulated. Unfortunately, there is little evidence-based guidance as to when brain imaging should be performed, often leading to overuse of tests such as CT, especially in emergency settings when confusion is noted. From a clinical standpoint, a head CT scan often is best ordered for patients who demonstrate an acute change in mental status, are age >70, are receiving anticoagulation, or have sustained trauma to the head. The key concern would be intracranial hemorrhage. However, some data suggest that the best use of head CT is for patients who have an impaired level of consciousness or a new focal neurologic deficit.11

Apart from more acute changes, a brain MRI study is more helpful than a head CT when evaluating the brain parenchyma for more sub-acute diagnoses such as multiple sclerosis or a brain tumor. T2-weighted hyperintensities seen on an MRI are thought to predict an increased risk of stroke, dementia, and death.

Their discovery should prompt a detailed evaluation for risk factors of stroke and dementia/NCD.12

In Ms. T’s case, she was taking lithium, so it was logical to obtain a trough lithium level 12 hours after the last dose and to check kidney function (serum creatinine to estimate the glomerular filtration rate), which were in the therapeutic/normal range. Her serum lithium level was 0.7 mEq/L. Brain imaging was not ordered, but several other labs (CMP, CBC, hemoglobin A1c [HgbA1c], and TSH) were drawn. These labs were notable for HgbA1c of 5.1% (normal <5.7%) and TSH of 0.5 mIU/L (normal level, 1.5 mIU/L), which is low for someone taking thyroid replacement.

I requested that Ms. T stop Armour Thyroid to address the suppressed TSH. I also requested that she stop metformin because, although hypoglycemia from metformin monotherapy is uncommon, it can happen in older patients. Hypoglycemia associated with metformin also can occur in situations when caloric intake is deficient or when metformin is used in combination with other drugs such as sulfonylureas (ie, glipizide), beta-adrenergic blocking drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or even nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.13

Identifying overlapping psychiatric (or psychological) illness

Symptoms of depression, anxiety, psychosis, and even dissociation can present as confusion. The term pseudodementia describes patients who exhibit cognitive symptoms consistent with NCD but could improve once the underlying mood, thought, anxiety, or personality disorder is treated.

For example, a patient with depression typically exhibits neurovegetative symptoms—such as poor sleep or appetite— amotivation, and low energy. All of these can lead to abrupt-onset cognitive changes, which are a hallmark of pseudodementia rather than the more insidious pattern of mild NCD. In cases of pseudodementia, neurocognitive testing will show impairment that often rapidly improves after the primary psychiatric (or psychological) issue is rectified. Making a diagnosis of pseudodementia at the initial presentation is difficult because neurocognitive tests such as the MMSE often fail to separate depression from true cognitive changes.14 Such a diagnosis typically requires hindsight. Yet, one must also keep in mind that pseudodementia may be part of a NCD prodrome.15

Conversion disorder as well as the dissociative disorders and substance-related disorders are notorious for causing confusion. In Ms. T’s case, pseudodementia stemming from her underlying bipolar disorder and anxiety figured prominently in the differential diagnosis, but she did not have any other overt psychopathology, personality disorder, or signs of malingering to further complicate her picture.

Notebook. I recommend that my patients keep a small notebook to record medical data ranging from blood pressure and glycemic measurements to details about sleep and dietary intake. Such data comprise the necessary metrics to properly assess target conditions and then track changes once treatment is initiated. This exercise not only yields much-needed detail about the patient’s condition for the clinician; the act of journaling also can be therapeutic for the writer through a process known as experimental disclosure, in which writing down one’s thoughts and observations has a positive impact on the writer’s physical health and psychology.16

Diagnosis. The first rule in medicine (perhaps the second, behind primum non nocere) is to determine what you are treating before beginning treatment (decernite quid tractemus, prius cura ministrandi, for Latin buffs). This means trying to fashion the best diagnostic label, even if it is merely a place-holder, while assessment of the confused state continues. DSM-5 has attempted to remove stigma from several neuropsychiatric disorders. On the cognition front, the new name for dementia is “neurocognitive disorder (NCD),” the umbrella term that focuses on the decline from a previous level of cognitive functioning. NCD has been divided into mild or major cognitive impairment headings either “with” or “without behavioral disturbance” subspecifiers.17

Aside from NCD, there are several other diagnoses in the differential for confusion. Delirium remains the most prominent and focuses on disturbances in attention and orientation that develops over a short period of time, with a change seen in an additional cognitive domain, such as memory, but not in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal such as coma. Subjective cognitive impairment (SCI) is when subjective complaints of cognitive impairment are hallmark compared with objective findings—with evidence suggesting that the presence of SCI could predict a 4.5 times higher rate of developing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) over 7 years.18 MCI was originally used to describe the early prodrome of AD, minus functional decline.

Treatment

After even a provisional diagnosis comes the final, all-important challenge: treating the neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of the confused patient. NPS are nearly universal in NCD/delirium throughout the course of illness. There are no FDA-approved treatments for the NPS associated with these conditions. In terms of treating delirium, the best approach is to treat the underlying medical condition. For control of behavior, which can range from agitated to psychotic to hypoactive, nonpharmacotherapeutic interventions are paramount; they include making sure that the patient is at the appropriate level of care, which, for the confused outpatient, could mean hospitalization. Ensuring proper nutrition, hydration, sensory care (hearing aids, glasses, etc.), and stability in ambulation must be done before considering pharmacotherapy.

Antipsychotic use has been the mainstay of drug treatment of behavioral dyscontrol. Haloperidol has been the traditional go-to medication because there is no evidence that low-dose haloperidol (<3 mg/d) has any different efficacy compared with the atypical antipsychotics or has a greater frequency of adverse drug effects. However, high-dose haloperidol (>4.5 mg/d) was associated with a greater incidence of adverse effects, mainly parkinsonism, than atypical antipsychotics.19 Neither the typical nor atypical antipsychotics have shown mortality benefit—the real outcome measure of interest.

In terms of treating major (or minor) NCD, there are only 2 FDA-approved medication classes: cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, etc.) and memantine. However, these medication classes—even when combined together—have only shown marginal benefit in terms of improving cognition. Worse, even when given early in the course of illness they do not reduce the rate of NCD. For pseudodementia, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors tend to form the mainstay of treating underlying depression or anxiety leading to cognitive changes. Preliminary data suggest that some SSRIs might improve cognition in terms of processing speed, verbal learning, and memory.20 More studies are needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

For the confused patient, a personalized therapeutic program, in which multiple interventions are considered at once (targeting all areas of the patient’s life) is gaining research traction. For example, a novel, comprehensive program involving multiple modalities designed to achieve metabolic enhancement for neurodegeneration (MEND) recently has shown robust benefit for patients with AD, MCI, and SCI.21 Using an individual approach to improve diet, activity, sleep, metabolic status including body mass index, and several other markers that affect neural plasticity, researchers demonstrated symptom improvement in 9 of 10 study patients.

Yet, some of the interventions, such as the use of statins for hyperlipidemia, remain controversial, with some studies suggesting that they help cognition,22,23 and others showing no association.24 The researchers caution that further research is warranted before costly dementia prevention trials with statins are undertaken. It does not appear that there are current MEND-type research projects in delirium but it’s to be hoped that we will see these in the future.

In the case of Ms. T, the cause of delirium vs mild NCD was thought to be multifactorial. Discontinuing Armour Thyroid and metformin—symptoms of hypoglycemia emerged as a leading concern—were simple adjustments that led to resolution of the most concerning elements of her confusion. She continued her other psychotropics, although there might be mild residual cognitive issues that warrant close observation.

Related Resources

• Lin JS, O’Connor E, Rossum RC, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults: an evidence update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013.

• Grover S, Kate N. Assessment scales for delirium: a review. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(4):58-70.

Drug Brand Names

Atorvastatin • Lipitor Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Donepezil • Aricept Lorazepam • Ativan

Escitalopram • Lexapro Memantine • Namenda

Flumazenil • Romazicon Metformin • Glucophage

Galantamine • Razadyne Naloxone • Narcan

Glipizide • Glucotrol Physostigmine • Antilirium

Haloperidol • Haldol Quetiapine • Seroquel

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid Rivastigmine • Exelon

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Valproic acid • Depakene

Disclosure

Dr. Raj is a speaker for Actavis Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Merck.

1. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, et al. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1451-1454.

2. Wilber ST, Lofgren SD, Mager TG, et al. An evaluation of two screening tools for cognitive impairment in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(7):612-616.

3. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder—a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910.

4. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695- 699.

5. Inouye S, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Int Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

6. Hillmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):781-787.

7. Raj YP. Psychiatric emergencies. In: Jiang W, Gagliardi JP, Krishnan KR, eds. Clinician’s guide to psychiatric care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009:33-40.

8. Liptzin B. Clinical diagnosis and management of delirium. In: Stoudemire A, Fogel BS, Greenberg DB, eds. Psychiatric care of the medical patient. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000:581-596.

9. Raj YP. Subclinical hypothyroidism: merely monitor or time to treat? Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(2):47-48.

10. Poloni N, Vender S, Bolla E, et al. Gluten encephalopathy with psychiatric onset: case report. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:16.

11. Naughton BJ, Moran M, Ghaly Y, et al. Computed tomography scanning and delirium in elder patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(12):1107-1110.

12. Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666.

13. Zitzmann S, Reimann IR, Schmechel H. Severe hypoglycemia in an elderly patient treated with metformin. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40(3):108-110.

14. Benson AD, Slavin MJ, Tran TT, et al. Screening for early Alzheimer’s Disease: is there still a role for the Mini-Mental State Examination? Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(2):62-69.

15. Brown WA. Pseudodementia: issues in diagnosis. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/ pseudodementia-issues-diagnosis. Published April 9, 2005. Accessed February 2, 2015.

16. Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):823-865.

17. Stetka BS, Correll CU. A guide to DSM-5: neurocognitive disorder. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/ viewarticle/803884_13. Published May 21, 2013. Accessed October 30, 2014.

18. Reisberg B, Sulman MD, Torossian C, et al. Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(1):11-24.

19. Lonergan E, Britton AM, Luxenberg J, et al. Antipsychotics for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005594.

20. Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Intern Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(4):215-223.

21. Bredesen DE. Reversal of cognitive decline: a novel therapeutic program. Aging (Albany NY). 2014;6(9):707-717.

22. Sparks DL, Kryscio RJ, Sabbagh MN, et al. Reduced risk of incident AD with elective statin use in a clinical trial cohort. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5(4):416-421.

23. Andrade C, Radhakrishnan R. The prevention and treatment of cognitive decline and dementia: an overview of recent research on experimental treatments. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(1):12-25.

24. Zandi PP, Sparks DL, Khachaturian AS, et al. Do statins reduce risk of incident dementia and Alzheimer disease? The Cache County Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(2):217-224.

“Mr. Smith seems somewhat confused today” is one of the most serious and concerning pre-visit reports you can receive from your staff or the patient’s family. Such a descriptor can be confusing—pardon the pun—not only for the patient, but to even seasoned mental health providers.

The term confusion can be code for diagnoses ranging from deliriuma to a progressive neurocognitive disorder (NCD) such as major NCD due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or even a more challenging problem such as beclouded dementia (delirium superimposed on dementia/NCD). It is essential for all mental health professionals to have an evidence-based approach when encountering signs or symptoms of confusion.

aICD-10 code R41.0 encompasses Confusion, Other Specified Delirium, or Unspecified Delirium.

CASE REPORT

Ms. T, age 62, has hypothyroidism and bipolar I disorder, most recently depressed, with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. She has been taking lithium, 600 mg/d, to control her mood symptoms. Her daughter-in-law reports that Ms. T has been exhibiting increasing signs of confusion. During the office evaluation, Ms. T minimizes her symptoms, only describing mild issues with forgetfulness while cooking and concern over increasing anxiety. Her daughter-in-law plays a voicemail message from earlier in the week, in which Ms. T’s speech is halting, disorganized, and in a word, confused. I decide to use the mnemonic decision chart MR. MIND (Table 1) to get to the bottom of her recent confusion.

Measure cognition

It is nice to receive advanced warning about a cognitive change or a change in activities of daily living; however, many patients present with subtle, sub-acute changes that are more difficult to assess. When encountering a broad symptom such as “confusion”—which has an equally broad differential diagnosis—systematic assessment of the current cognitive state compared with the patient’s baseline becomes the first order of business. However, this requires that the patient has had a baseline cognitive assessment.

In my practice, I often administer one of the validated neurocognitive screening instruments when a patient first begins care—even a brief test such as the Mini- Cog (3-item recall plus clock drawing test), which is comparable to longer screening tests at least for NCD/dementia.1 During a presentation for confusion, a more detailed neurocognitive assessment instrument would be recommended, allowing one to marry the clinical impression with a validated, objective measure. Formal neuropsychological testing by a clinical neuropsychologist is the gold standard, but such testing is time-consuming and expensive and often not readily available. The screening instrument I use for a more thorough evaluation depends on the clinical scenario.

The Six-Item Screener is used in some emergency settings because it is short but boasts a higher sensitivity than the Mini- Cog (94% vs 75%) with similar specificity when screening for cognitive impairment.2 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a valuable instrument, although, recently, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination has been thought to be better at detecting mild NCD than the MMSE; more data are needed to substantiate this claim.3 The Montreal Cognitive Assessment is another validated screening tool that has been shown to be superior to the MMSE in terms of screening for mild cognitive impairment.4 The best delirium-specific assessment tool is the Confusion Assessment Method (Table 2).5

Ms. T’s MMSE score was 26/30, down from 29/30 at baseline. Her score fell below the cutoff score of 27 for mild cognitive impairment for someone with at least 8 years of completed education. Her results were abnormal mainly in the memory domain (3-item recall), raising the question of a possible prodromal state of AD although the acute nature of the change made delirium or mild NCD high in the differential.

Review medications

A review of the medication list is not just a Joint Commission mandate (medication reconciliation during each encounter) but is important whenever confusion is noted. Polypharmacy can be a concern, but is not as concerning as the class of medication prescribed, particularly anticholinergic and sedative medications in patients age >65. The Drug Burden Index can be helpful in assessing this risk.6 Medications such as the benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, tricyclic antidepressants, and antipsychotics should be discontinued if possible, keeping in mind that the addition or subtraction of medications must be done prudently and only after reviewing the evidence and in consultation with the patient. A detailed medication review is as important for confused outpatients as it is for an inpatient case (steps 2 and 3 of the inpatient algorithm outlined in Table 3).7

In Ms. T’s case, the primary concern on her medication list was that her medical team was prescribing levothyroxine, 112 mcg/d, and desiccated thyroid (combination thyroxine and triiodothyronine in the form of 20 mg Armour Thyroid), despite a lack of data for such combination therapy. Earlier, I had discontinued lorazepam, leaving lithium, 600 mg/d, quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d, as her remaining psychotropics. Her other medications included atorvastatin, 40 mg/d, for hyper-lipidemia and metformin, 750 mg/d, for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Medical illness

An organic basis must rank high in the differential diagnosis if medications are not the culprit. There are myriad medical disorders that can lead to confusion (Table 4).8 In an outpatient psychiatric setting, laboratory and radiology testing might not be readily available. It then becomes important to collaborate with a patient’s medical team if any of the following are met:

•there is high suspicion of a medical cause

•there could be delays in performing a medical workup

•a physical examination is needed.

Laboratory work-up should include:

•comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) to assess for electrolyte derangements and liver or kidney disease

•urinalysis if there are signs of urinary tract infection (low threshold for testing in patients age >65 even if they are asymptomatic)

•urine drug screen or serum alcohol level if substance use is suspected

•complete blood count (CBC) if there are reports of infection (white blood cell count) or blood loss/bruising to ensure that anemia or thrombocytopenia is not playing a role

•thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) because thyroid disorders can cause neuropsychiatric as well as somatic symptoms.9

Other laboratory testing could be valuable depending on the clinical scenario. These include tests such as:

•drug level monitoring (lithium, valproic acid, etc.) to assess for toxicity

•HIV and rapid plasma reagin for suspected sexually transmitted infections

•vitamin levels in patients with poor nutrition or post bariatric surgery

•erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, or both, if there are signs of inflammation

•bacterial culture if blood or tissue infection is a concern.

Esoteric tests include ceruloplasmin (Wilson’s disease), heavy metals screen, and even tests such as anti-gliadin antibodies because the prevalence of gluten sensitivity and celiac disease appear to be on the rise and have been associated with neuropsychiatric problems including encephalopathy.10

Brain imaging is an important consideration when a medical differential diagnosis for confusion is formulated. Unfortunately, there is little evidence-based guidance as to when brain imaging should be performed, often leading to overuse of tests such as CT, especially in emergency settings when confusion is noted. From a clinical standpoint, a head CT scan often is best ordered for patients who demonstrate an acute change in mental status, are age >70, are receiving anticoagulation, or have sustained trauma to the head. The key concern would be intracranial hemorrhage. However, some data suggest that the best use of head CT is for patients who have an impaired level of consciousness or a new focal neurologic deficit.11

Apart from more acute changes, a brain MRI study is more helpful than a head CT when evaluating the brain parenchyma for more sub-acute diagnoses such as multiple sclerosis or a brain tumor. T2-weighted hyperintensities seen on an MRI are thought to predict an increased risk of stroke, dementia, and death.

Their discovery should prompt a detailed evaluation for risk factors of stroke and dementia/NCD.12

In Ms. T’s case, she was taking lithium, so it was logical to obtain a trough lithium level 12 hours after the last dose and to check kidney function (serum creatinine to estimate the glomerular filtration rate), which were in the therapeutic/normal range. Her serum lithium level was 0.7 mEq/L. Brain imaging was not ordered, but several other labs (CMP, CBC, hemoglobin A1c [HgbA1c], and TSH) were drawn. These labs were notable for HgbA1c of 5.1% (normal <5.7%) and TSH of 0.5 mIU/L (normal level, 1.5 mIU/L), which is low for someone taking thyroid replacement.

I requested that Ms. T stop Armour Thyroid to address the suppressed TSH. I also requested that she stop metformin because, although hypoglycemia from metformin monotherapy is uncommon, it can happen in older patients. Hypoglycemia associated with metformin also can occur in situations when caloric intake is deficient or when metformin is used in combination with other drugs such as sulfonylureas (ie, glipizide), beta-adrenergic blocking drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or even nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.13

Identifying overlapping psychiatric (or psychological) illness

Symptoms of depression, anxiety, psychosis, and even dissociation can present as confusion. The term pseudodementia describes patients who exhibit cognitive symptoms consistent with NCD but could improve once the underlying mood, thought, anxiety, or personality disorder is treated.

For example, a patient with depression typically exhibits neurovegetative symptoms—such as poor sleep or appetite— amotivation, and low energy. All of these can lead to abrupt-onset cognitive changes, which are a hallmark of pseudodementia rather than the more insidious pattern of mild NCD. In cases of pseudodementia, neurocognitive testing will show impairment that often rapidly improves after the primary psychiatric (or psychological) issue is rectified. Making a diagnosis of pseudodementia at the initial presentation is difficult because neurocognitive tests such as the MMSE often fail to separate depression from true cognitive changes.14 Such a diagnosis typically requires hindsight. Yet, one must also keep in mind that pseudodementia may be part of a NCD prodrome.15

Conversion disorder as well as the dissociative disorders and substance-related disorders are notorious for causing confusion. In Ms. T’s case, pseudodementia stemming from her underlying bipolar disorder and anxiety figured prominently in the differential diagnosis, but she did not have any other overt psychopathology, personality disorder, or signs of malingering to further complicate her picture.

Notebook. I recommend that my patients keep a small notebook to record medical data ranging from blood pressure and glycemic measurements to details about sleep and dietary intake. Such data comprise the necessary metrics to properly assess target conditions and then track changes once treatment is initiated. This exercise not only yields much-needed detail about the patient’s condition for the clinician; the act of journaling also can be therapeutic for the writer through a process known as experimental disclosure, in which writing down one’s thoughts and observations has a positive impact on the writer’s physical health and psychology.16

Diagnosis. The first rule in medicine (perhaps the second, behind primum non nocere) is to determine what you are treating before beginning treatment (decernite quid tractemus, prius cura ministrandi, for Latin buffs). This means trying to fashion the best diagnostic label, even if it is merely a place-holder, while assessment of the confused state continues. DSM-5 has attempted to remove stigma from several neuropsychiatric disorders. On the cognition front, the new name for dementia is “neurocognitive disorder (NCD),” the umbrella term that focuses on the decline from a previous level of cognitive functioning. NCD has been divided into mild or major cognitive impairment headings either “with” or “without behavioral disturbance” subspecifiers.17

Aside from NCD, there are several other diagnoses in the differential for confusion. Delirium remains the most prominent and focuses on disturbances in attention and orientation that develops over a short period of time, with a change seen in an additional cognitive domain, such as memory, but not in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal such as coma. Subjective cognitive impairment (SCI) is when subjective complaints of cognitive impairment are hallmark compared with objective findings—with evidence suggesting that the presence of SCI could predict a 4.5 times higher rate of developing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) over 7 years.18 MCI was originally used to describe the early prodrome of AD, minus functional decline.

Treatment

After even a provisional diagnosis comes the final, all-important challenge: treating the neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of the confused patient. NPS are nearly universal in NCD/delirium throughout the course of illness. There are no FDA-approved treatments for the NPS associated with these conditions. In terms of treating delirium, the best approach is to treat the underlying medical condition. For control of behavior, which can range from agitated to psychotic to hypoactive, nonpharmacotherapeutic interventions are paramount; they include making sure that the patient is at the appropriate level of care, which, for the confused outpatient, could mean hospitalization. Ensuring proper nutrition, hydration, sensory care (hearing aids, glasses, etc.), and stability in ambulation must be done before considering pharmacotherapy.

Antipsychotic use has been the mainstay of drug treatment of behavioral dyscontrol. Haloperidol has been the traditional go-to medication because there is no evidence that low-dose haloperidol (<3 mg/d) has any different efficacy compared with the atypical antipsychotics or has a greater frequency of adverse drug effects. However, high-dose haloperidol (>4.5 mg/d) was associated with a greater incidence of adverse effects, mainly parkinsonism, than atypical antipsychotics.19 Neither the typical nor atypical antipsychotics have shown mortality benefit—the real outcome measure of interest.

In terms of treating major (or minor) NCD, there are only 2 FDA-approved medication classes: cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, etc.) and memantine. However, these medication classes—even when combined together—have only shown marginal benefit in terms of improving cognition. Worse, even when given early in the course of illness they do not reduce the rate of NCD. For pseudodementia, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors tend to form the mainstay of treating underlying depression or anxiety leading to cognitive changes. Preliminary data suggest that some SSRIs might improve cognition in terms of processing speed, verbal learning, and memory.20 More studies are needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

For the confused patient, a personalized therapeutic program, in which multiple interventions are considered at once (targeting all areas of the patient’s life) is gaining research traction. For example, a novel, comprehensive program involving multiple modalities designed to achieve metabolic enhancement for neurodegeneration (MEND) recently has shown robust benefit for patients with AD, MCI, and SCI.21 Using an individual approach to improve diet, activity, sleep, metabolic status including body mass index, and several other markers that affect neural plasticity, researchers demonstrated symptom improvement in 9 of 10 study patients.

Yet, some of the interventions, such as the use of statins for hyperlipidemia, remain controversial, with some studies suggesting that they help cognition,22,23 and others showing no association.24 The researchers caution that further research is warranted before costly dementia prevention trials with statins are undertaken. It does not appear that there are current MEND-type research projects in delirium but it’s to be hoped that we will see these in the future.

In the case of Ms. T, the cause of delirium vs mild NCD was thought to be multifactorial. Discontinuing Armour Thyroid and metformin—symptoms of hypoglycemia emerged as a leading concern—were simple adjustments that led to resolution of the most concerning elements of her confusion. She continued her other psychotropics, although there might be mild residual cognitive issues that warrant close observation.

Related Resources

• Lin JS, O’Connor E, Rossum RC, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults: an evidence update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013.

• Grover S, Kate N. Assessment scales for delirium: a review. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(4):58-70.

Drug Brand Names

Atorvastatin • Lipitor Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Donepezil • Aricept Lorazepam • Ativan

Escitalopram • Lexapro Memantine • Namenda

Flumazenil • Romazicon Metformin • Glucophage

Galantamine • Razadyne Naloxone • Narcan

Glipizide • Glucotrol Physostigmine • Antilirium

Haloperidol • Haldol Quetiapine • Seroquel

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid Rivastigmine • Exelon

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Valproic acid • Depakene

Disclosure

Dr. Raj is a speaker for Actavis Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Merck.

“Mr. Smith seems somewhat confused today” is one of the most serious and concerning pre-visit reports you can receive from your staff or the patient’s family. Such a descriptor can be confusing—pardon the pun—not only for the patient, but to even seasoned mental health providers.

The term confusion can be code for diagnoses ranging from deliriuma to a progressive neurocognitive disorder (NCD) such as major NCD due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or even a more challenging problem such as beclouded dementia (delirium superimposed on dementia/NCD). It is essential for all mental health professionals to have an evidence-based approach when encountering signs or symptoms of confusion.

aICD-10 code R41.0 encompasses Confusion, Other Specified Delirium, or Unspecified Delirium.

CASE REPORT

Ms. T, age 62, has hypothyroidism and bipolar I disorder, most recently depressed, with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. She has been taking lithium, 600 mg/d, to control her mood symptoms. Her daughter-in-law reports that Ms. T has been exhibiting increasing signs of confusion. During the office evaluation, Ms. T minimizes her symptoms, only describing mild issues with forgetfulness while cooking and concern over increasing anxiety. Her daughter-in-law plays a voicemail message from earlier in the week, in which Ms. T’s speech is halting, disorganized, and in a word, confused. I decide to use the mnemonic decision chart MR. MIND (Table 1) to get to the bottom of her recent confusion.

Measure cognition

It is nice to receive advanced warning about a cognitive change or a change in activities of daily living; however, many patients present with subtle, sub-acute changes that are more difficult to assess. When encountering a broad symptom such as “confusion”—which has an equally broad differential diagnosis—systematic assessment of the current cognitive state compared with the patient’s baseline becomes the first order of business. However, this requires that the patient has had a baseline cognitive assessment.

In my practice, I often administer one of the validated neurocognitive screening instruments when a patient first begins care—even a brief test such as the Mini- Cog (3-item recall plus clock drawing test), which is comparable to longer screening tests at least for NCD/dementia.1 During a presentation for confusion, a more detailed neurocognitive assessment instrument would be recommended, allowing one to marry the clinical impression with a validated, objective measure. Formal neuropsychological testing by a clinical neuropsychologist is the gold standard, but such testing is time-consuming and expensive and often not readily available. The screening instrument I use for a more thorough evaluation depends on the clinical scenario.

The Six-Item Screener is used in some emergency settings because it is short but boasts a higher sensitivity than the Mini- Cog (94% vs 75%) with similar specificity when screening for cognitive impairment.2 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a valuable instrument, although, recently, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination has been thought to be better at detecting mild NCD than the MMSE; more data are needed to substantiate this claim.3 The Montreal Cognitive Assessment is another validated screening tool that has been shown to be superior to the MMSE in terms of screening for mild cognitive impairment.4 The best delirium-specific assessment tool is the Confusion Assessment Method (Table 2).5

Ms. T’s MMSE score was 26/30, down from 29/30 at baseline. Her score fell below the cutoff score of 27 for mild cognitive impairment for someone with at least 8 years of completed education. Her results were abnormal mainly in the memory domain (3-item recall), raising the question of a possible prodromal state of AD although the acute nature of the change made delirium or mild NCD high in the differential.

Review medications

A review of the medication list is not just a Joint Commission mandate (medication reconciliation during each encounter) but is important whenever confusion is noted. Polypharmacy can be a concern, but is not as concerning as the class of medication prescribed, particularly anticholinergic and sedative medications in patients age >65. The Drug Burden Index can be helpful in assessing this risk.6 Medications such as the benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, tricyclic antidepressants, and antipsychotics should be discontinued if possible, keeping in mind that the addition or subtraction of medications must be done prudently and only after reviewing the evidence and in consultation with the patient. A detailed medication review is as important for confused outpatients as it is for an inpatient case (steps 2 and 3 of the inpatient algorithm outlined in Table 3).7

In Ms. T’s case, the primary concern on her medication list was that her medical team was prescribing levothyroxine, 112 mcg/d, and desiccated thyroid (combination thyroxine and triiodothyronine in the form of 20 mg Armour Thyroid), despite a lack of data for such combination therapy. Earlier, I had discontinued lorazepam, leaving lithium, 600 mg/d, quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d, as her remaining psychotropics. Her other medications included atorvastatin, 40 mg/d, for hyper-lipidemia and metformin, 750 mg/d, for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Medical illness

An organic basis must rank high in the differential diagnosis if medications are not the culprit. There are myriad medical disorders that can lead to confusion (Table 4).8 In an outpatient psychiatric setting, laboratory and radiology testing might not be readily available. It then becomes important to collaborate with a patient’s medical team if any of the following are met:

•there is high suspicion of a medical cause

•there could be delays in performing a medical workup

•a physical examination is needed.

Laboratory work-up should include:

•comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) to assess for electrolyte derangements and liver or kidney disease

•urinalysis if there are signs of urinary tract infection (low threshold for testing in patients age >65 even if they are asymptomatic)

•urine drug screen or serum alcohol level if substance use is suspected

•complete blood count (CBC) if there are reports of infection (white blood cell count) or blood loss/bruising to ensure that anemia or thrombocytopenia is not playing a role

•thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) because thyroid disorders can cause neuropsychiatric as well as somatic symptoms.9

Other laboratory testing could be valuable depending on the clinical scenario. These include tests such as:

•drug level monitoring (lithium, valproic acid, etc.) to assess for toxicity

•HIV and rapid plasma reagin for suspected sexually transmitted infections

•vitamin levels in patients with poor nutrition or post bariatric surgery

•erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, or both, if there are signs of inflammation

•bacterial culture if blood or tissue infection is a concern.

Esoteric tests include ceruloplasmin (Wilson’s disease), heavy metals screen, and even tests such as anti-gliadin antibodies because the prevalence of gluten sensitivity and celiac disease appear to be on the rise and have been associated with neuropsychiatric problems including encephalopathy.10

Brain imaging is an important consideration when a medical differential diagnosis for confusion is formulated. Unfortunately, there is little evidence-based guidance as to when brain imaging should be performed, often leading to overuse of tests such as CT, especially in emergency settings when confusion is noted. From a clinical standpoint, a head CT scan often is best ordered for patients who demonstrate an acute change in mental status, are age >70, are receiving anticoagulation, or have sustained trauma to the head. The key concern would be intracranial hemorrhage. However, some data suggest that the best use of head CT is for patients who have an impaired level of consciousness or a new focal neurologic deficit.11

Apart from more acute changes, a brain MRI study is more helpful than a head CT when evaluating the brain parenchyma for more sub-acute diagnoses such as multiple sclerosis or a brain tumor. T2-weighted hyperintensities seen on an MRI are thought to predict an increased risk of stroke, dementia, and death.

Their discovery should prompt a detailed evaluation for risk factors of stroke and dementia/NCD.12

In Ms. T’s case, she was taking lithium, so it was logical to obtain a trough lithium level 12 hours after the last dose and to check kidney function (serum creatinine to estimate the glomerular filtration rate), which were in the therapeutic/normal range. Her serum lithium level was 0.7 mEq/L. Brain imaging was not ordered, but several other labs (CMP, CBC, hemoglobin A1c [HgbA1c], and TSH) were drawn. These labs were notable for HgbA1c of 5.1% (normal <5.7%) and TSH of 0.5 mIU/L (normal level, 1.5 mIU/L), which is low for someone taking thyroid replacement.

I requested that Ms. T stop Armour Thyroid to address the suppressed TSH. I also requested that she stop metformin because, although hypoglycemia from metformin monotherapy is uncommon, it can happen in older patients. Hypoglycemia associated with metformin also can occur in situations when caloric intake is deficient or when metformin is used in combination with other drugs such as sulfonylureas (ie, glipizide), beta-adrenergic blocking drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or even nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.13

Identifying overlapping psychiatric (or psychological) illness

Symptoms of depression, anxiety, psychosis, and even dissociation can present as confusion. The term pseudodementia describes patients who exhibit cognitive symptoms consistent with NCD but could improve once the underlying mood, thought, anxiety, or personality disorder is treated.

For example, a patient with depression typically exhibits neurovegetative symptoms—such as poor sleep or appetite— amotivation, and low energy. All of these can lead to abrupt-onset cognitive changes, which are a hallmark of pseudodementia rather than the more insidious pattern of mild NCD. In cases of pseudodementia, neurocognitive testing will show impairment that often rapidly improves after the primary psychiatric (or psychological) issue is rectified. Making a diagnosis of pseudodementia at the initial presentation is difficult because neurocognitive tests such as the MMSE often fail to separate depression from true cognitive changes.14 Such a diagnosis typically requires hindsight. Yet, one must also keep in mind that pseudodementia may be part of a NCD prodrome.15

Conversion disorder as well as the dissociative disorders and substance-related disorders are notorious for causing confusion. In Ms. T’s case, pseudodementia stemming from her underlying bipolar disorder and anxiety figured prominently in the differential diagnosis, but she did not have any other overt psychopathology, personality disorder, or signs of malingering to further complicate her picture.

Notebook. I recommend that my patients keep a small notebook to record medical data ranging from blood pressure and glycemic measurements to details about sleep and dietary intake. Such data comprise the necessary metrics to properly assess target conditions and then track changes once treatment is initiated. This exercise not only yields much-needed detail about the patient’s condition for the clinician; the act of journaling also can be therapeutic for the writer through a process known as experimental disclosure, in which writing down one’s thoughts and observations has a positive impact on the writer’s physical health and psychology.16

Diagnosis. The first rule in medicine (perhaps the second, behind primum non nocere) is to determine what you are treating before beginning treatment (decernite quid tractemus, prius cura ministrandi, for Latin buffs). This means trying to fashion the best diagnostic label, even if it is merely a place-holder, while assessment of the confused state continues. DSM-5 has attempted to remove stigma from several neuropsychiatric disorders. On the cognition front, the new name for dementia is “neurocognitive disorder (NCD),” the umbrella term that focuses on the decline from a previous level of cognitive functioning. NCD has been divided into mild or major cognitive impairment headings either “with” or “without behavioral disturbance” subspecifiers.17

Aside from NCD, there are several other diagnoses in the differential for confusion. Delirium remains the most prominent and focuses on disturbances in attention and orientation that develops over a short period of time, with a change seen in an additional cognitive domain, such as memory, but not in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal such as coma. Subjective cognitive impairment (SCI) is when subjective complaints of cognitive impairment are hallmark compared with objective findings—with evidence suggesting that the presence of SCI could predict a 4.5 times higher rate of developing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) over 7 years.18 MCI was originally used to describe the early prodrome of AD, minus functional decline.

Treatment

After even a provisional diagnosis comes the final, all-important challenge: treating the neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of the confused patient. NPS are nearly universal in NCD/delirium throughout the course of illness. There are no FDA-approved treatments for the NPS associated with these conditions. In terms of treating delirium, the best approach is to treat the underlying medical condition. For control of behavior, which can range from agitated to psychotic to hypoactive, nonpharmacotherapeutic interventions are paramount; they include making sure that the patient is at the appropriate level of care, which, for the confused outpatient, could mean hospitalization. Ensuring proper nutrition, hydration, sensory care (hearing aids, glasses, etc.), and stability in ambulation must be done before considering pharmacotherapy.

Antipsychotic use has been the mainstay of drug treatment of behavioral dyscontrol. Haloperidol has been the traditional go-to medication because there is no evidence that low-dose haloperidol (<3 mg/d) has any different efficacy compared with the atypical antipsychotics or has a greater frequency of adverse drug effects. However, high-dose haloperidol (>4.5 mg/d) was associated with a greater incidence of adverse effects, mainly parkinsonism, than atypical antipsychotics.19 Neither the typical nor atypical antipsychotics have shown mortality benefit—the real outcome measure of interest.

In terms of treating major (or minor) NCD, there are only 2 FDA-approved medication classes: cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, etc.) and memantine. However, these medication classes—even when combined together—have only shown marginal benefit in terms of improving cognition. Worse, even when given early in the course of illness they do not reduce the rate of NCD. For pseudodementia, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors tend to form the mainstay of treating underlying depression or anxiety leading to cognitive changes. Preliminary data suggest that some SSRIs might improve cognition in terms of processing speed, verbal learning, and memory.20 More studies are needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

For the confused patient, a personalized therapeutic program, in which multiple interventions are considered at once (targeting all areas of the patient’s life) is gaining research traction. For example, a novel, comprehensive program involving multiple modalities designed to achieve metabolic enhancement for neurodegeneration (MEND) recently has shown robust benefit for patients with AD, MCI, and SCI.21 Using an individual approach to improve diet, activity, sleep, metabolic status including body mass index, and several other markers that affect neural plasticity, researchers demonstrated symptom improvement in 9 of 10 study patients.

Yet, some of the interventions, such as the use of statins for hyperlipidemia, remain controversial, with some studies suggesting that they help cognition,22,23 and others showing no association.24 The researchers caution that further research is warranted before costly dementia prevention trials with statins are undertaken. It does not appear that there are current MEND-type research projects in delirium but it’s to be hoped that we will see these in the future.

In the case of Ms. T, the cause of delirium vs mild NCD was thought to be multifactorial. Discontinuing Armour Thyroid and metformin—symptoms of hypoglycemia emerged as a leading concern—were simple adjustments that led to resolution of the most concerning elements of her confusion. She continued her other psychotropics, although there might be mild residual cognitive issues that warrant close observation.

Related Resources

• Lin JS, O’Connor E, Rossum RC, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults: an evidence update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013.

• Grover S, Kate N. Assessment scales for delirium: a review. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(4):58-70.

Drug Brand Names

Atorvastatin • Lipitor Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Donepezil • Aricept Lorazepam • Ativan

Escitalopram • Lexapro Memantine • Namenda

Flumazenil • Romazicon Metformin • Glucophage

Galantamine • Razadyne Naloxone • Narcan

Glipizide • Glucotrol Physostigmine • Antilirium

Haloperidol • Haldol Quetiapine • Seroquel

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid Rivastigmine • Exelon

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Valproic acid • Depakene

Disclosure

Dr. Raj is a speaker for Actavis Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Merck.

1. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, et al. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1451-1454.

2. Wilber ST, Lofgren SD, Mager TG, et al. An evaluation of two screening tools for cognitive impairment in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(7):612-616.

3. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder—a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910.

4. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695- 699.

5. Inouye S, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Int Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

6. Hillmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):781-787.

7. Raj YP. Psychiatric emergencies. In: Jiang W, Gagliardi JP, Krishnan KR, eds. Clinician’s guide to psychiatric care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009:33-40.

8. Liptzin B. Clinical diagnosis and management of delirium. In: Stoudemire A, Fogel BS, Greenberg DB, eds. Psychiatric care of the medical patient. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000:581-596.

9. Raj YP. Subclinical hypothyroidism: merely monitor or time to treat? Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(2):47-48.

10. Poloni N, Vender S, Bolla E, et al. Gluten encephalopathy with psychiatric onset: case report. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:16.

11. Naughton BJ, Moran M, Ghaly Y, et al. Computed tomography scanning and delirium in elder patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(12):1107-1110.

12. Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666.

13. Zitzmann S, Reimann IR, Schmechel H. Severe hypoglycemia in an elderly patient treated with metformin. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40(3):108-110.

14. Benson AD, Slavin MJ, Tran TT, et al. Screening for early Alzheimer’s Disease: is there still a role for the Mini-Mental State Examination? Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(2):62-69.

15. Brown WA. Pseudodementia: issues in diagnosis. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/ pseudodementia-issues-diagnosis. Published April 9, 2005. Accessed February 2, 2015.

16. Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):823-865.

17. Stetka BS, Correll CU. A guide to DSM-5: neurocognitive disorder. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/ viewarticle/803884_13. Published May 21, 2013. Accessed October 30, 2014.

18. Reisberg B, Sulman MD, Torossian C, et al. Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(1):11-24.

19. Lonergan E, Britton AM, Luxenberg J, et al. Antipsychotics for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005594.

20. Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Intern Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(4):215-223.

21. Bredesen DE. Reversal of cognitive decline: a novel therapeutic program. Aging (Albany NY). 2014;6(9):707-717.

22. Sparks DL, Kryscio RJ, Sabbagh MN, et al. Reduced risk of incident AD with elective statin use in a clinical trial cohort. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5(4):416-421.

23. Andrade C, Radhakrishnan R. The prevention and treatment of cognitive decline and dementia: an overview of recent research on experimental treatments. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(1):12-25.

24. Zandi PP, Sparks DL, Khachaturian AS, et al. Do statins reduce risk of incident dementia and Alzheimer disease? The Cache County Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(2):217-224.

1. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, et al. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1451-1454.

2. Wilber ST, Lofgren SD, Mager TG, et al. An evaluation of two screening tools for cognitive impairment in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(7):612-616.

3. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder—a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910.

4. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695- 699.

5. Inouye S, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Int Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

6. Hillmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):781-787.

7. Raj YP. Psychiatric emergencies. In: Jiang W, Gagliardi JP, Krishnan KR, eds. Clinician’s guide to psychiatric care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009:33-40.

8. Liptzin B. Clinical diagnosis and management of delirium. In: Stoudemire A, Fogel BS, Greenberg DB, eds. Psychiatric care of the medical patient. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000:581-596.

9. Raj YP. Subclinical hypothyroidism: merely monitor or time to treat? Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(2):47-48.

10. Poloni N, Vender S, Bolla E, et al. Gluten encephalopathy with psychiatric onset: case report. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:16.

11. Naughton BJ, Moran M, Ghaly Y, et al. Computed tomography scanning and delirium in elder patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(12):1107-1110.

12. Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666.

13. Zitzmann S, Reimann IR, Schmechel H. Severe hypoglycemia in an elderly patient treated with metformin. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40(3):108-110.

14. Benson AD, Slavin MJ, Tran TT, et al. Screening for early Alzheimer’s Disease: is there still a role for the Mini-Mental State Examination? Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(2):62-69.

15. Brown WA. Pseudodementia: issues in diagnosis. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/ pseudodementia-issues-diagnosis. Published April 9, 2005. Accessed February 2, 2015.

16. Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):823-865.

17. Stetka BS, Correll CU. A guide to DSM-5: neurocognitive disorder. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/ viewarticle/803884_13. Published May 21, 2013. Accessed October 30, 2014.

18. Reisberg B, Sulman MD, Torossian C, et al. Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(1):11-24.

19. Lonergan E, Britton AM, Luxenberg J, et al. Antipsychotics for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005594.

20. Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Intern Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(4):215-223.

21. Bredesen DE. Reversal of cognitive decline: a novel therapeutic program. Aging (Albany NY). 2014;6(9):707-717.

22. Sparks DL, Kryscio RJ, Sabbagh MN, et al. Reduced risk of incident AD with elective statin use in a clinical trial cohort. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5(4):416-421.

23. Andrade C, Radhakrishnan R. The prevention and treatment of cognitive decline and dementia: an overview of recent research on experimental treatments. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(1):12-25.

24. Zandi PP, Sparks DL, Khachaturian AS, et al. Do statins reduce risk of incident dementia and Alzheimer disease? The Cache County Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(2):217-224.