User login

A shot in the arm: Boost your knowledge about immunizations for psychiatric patients

Patients with chronic, severe mental illness live much shorter lives than the general population. The 25-year loss in life expectancy for people with chronic mental illness has been attributed to higher rates of cardiovascular disease driven by increased smoking, obesity, poverty, and poor nutrition.1 These individuals also face the added burden of struggling with a psychiatric condition that often interferes with their ability to make optimal preventative health decisions, including staying up to date on vaccinations.2 A recent review from Toronto, Canada, found that the influenza vaccination rates among homeless adults with mental illness—a population at high risk of respiratory illness—was only 6.7% compared with 31.1% for the general population of Ontario.3

Mental health professionals may serve as the only contacts to offer medical care to this vulnerable population, leading some psychiatric leaders to advocate that psychiatrists be considered primary care providers within accountable care organizations. Because most vaccines are easily available, mental health professionals should know about key immunizations to guide their patients accordingly.

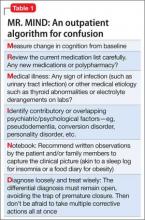

In the United States, approximately 45,000 adults die annually from vaccine-preventable diseases, the majority from influenza.4 When combined with the most recent Adult Immunization Schedule and general recommendations adapted from the CDC,5,6 the mnemonic ARM SHOT allows for a quick assessment of risk factors to guide administration and education about most vaccinations (Table 1). ARM SHOT involves assessing the following components of an individual’s health status and living arrangements to determine one’s risk of contracting communicable diseases:

- Age

- Risk of exposure

- Medical conditions (comorbidities)

- Substance use history

- HIV status or other immunocompromised states

- Occupancy, or living arrangements

- Tobacco use.

We recommend keeping a copy of the Adult Immunization Schedule (age ≥19) and/or the immunization schedule for children and adolescents (age ≤18) close for quick reference. Here, we provide a case and then explore how each component of the ARM SHOT mnemonic applies in decision-making.

Case Evaluating risk, assess needs

Ms. W, age 24, has bipolar I disorder, most recently manic with psychotic features. She presents for follow-up in clinic after a 5-day hospitalization for mania and comorbid alcohol use disorder. Her medical comorbidities include asthma and active tobacco use. She is taking lurasidone, 20 mg/d, and lithium, 900 mg/d. Her case manager is working to place Ms. W in a residential substance use disorder treatment program. Ms. W is on a waiting list to establish care with a primary care physician and has a history of poor engagement with medical services in general; prior attempts to place her with a primary care physician failed.

In advance of Ms. W’s transfer to a residential treatment facility, you have been asked to place a Mantoux screening test for tuberculosis (purified protein derivative), which raises the important question about her susceptibility to infectious diseases in general. To protect Ms. W from preventable diseases for which vaccines are available, you review the ARM SHOT mnemonic to broadly assess her candidacy for vaccinations.

Age

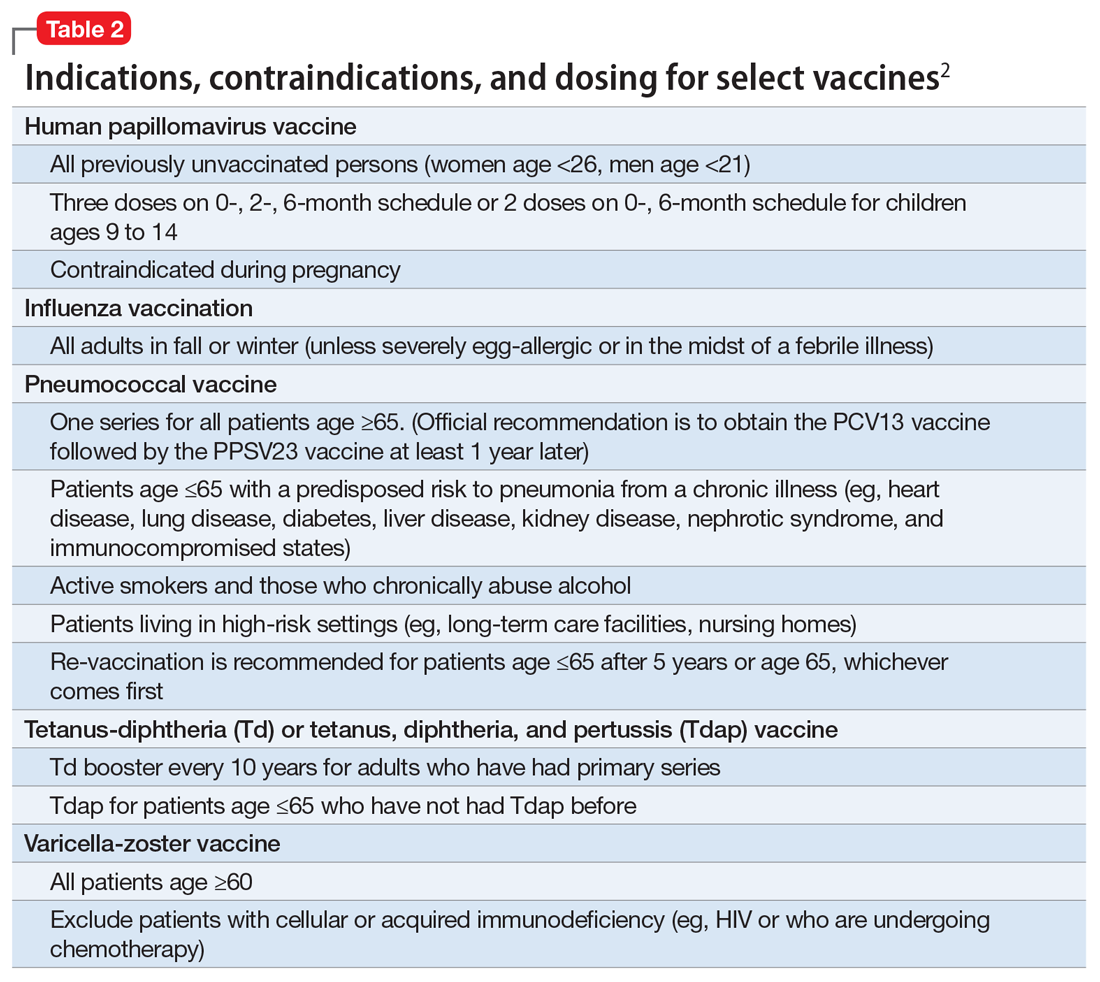

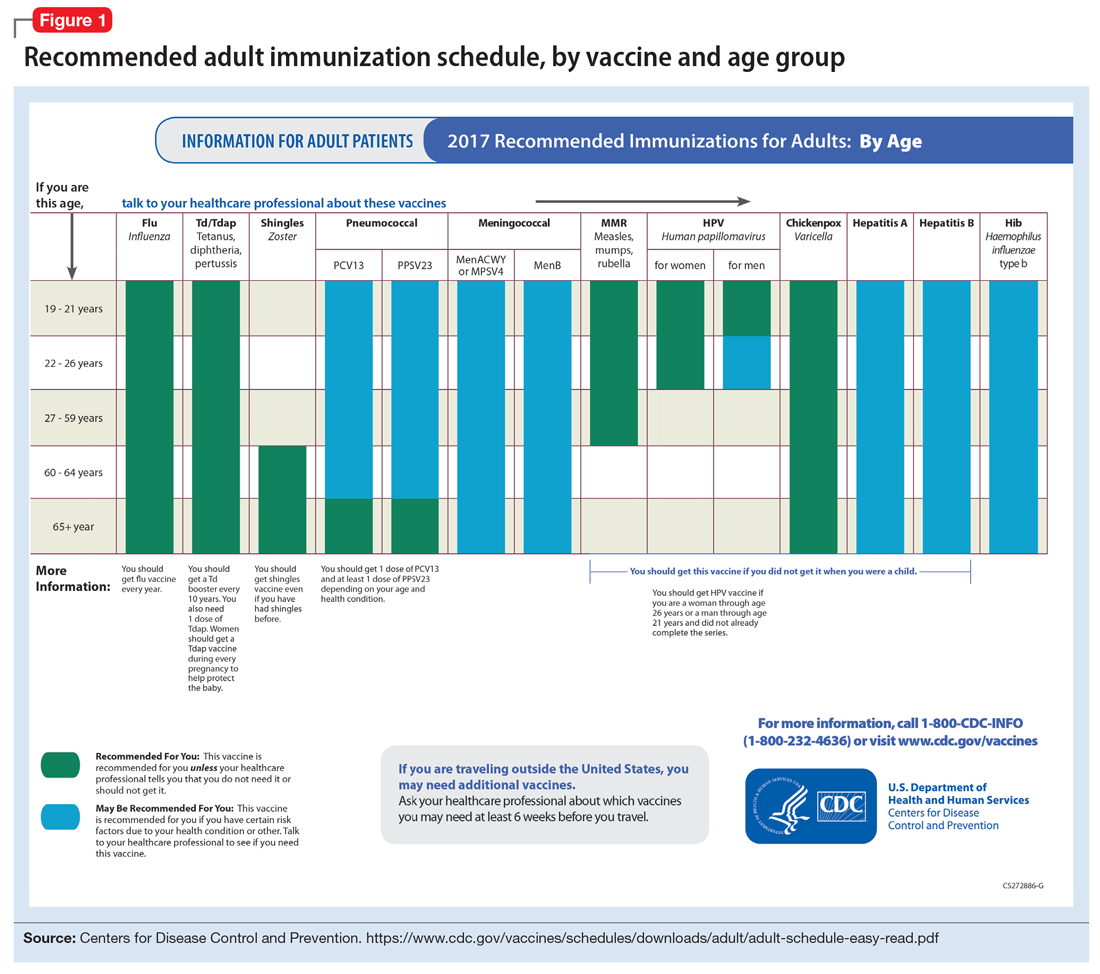

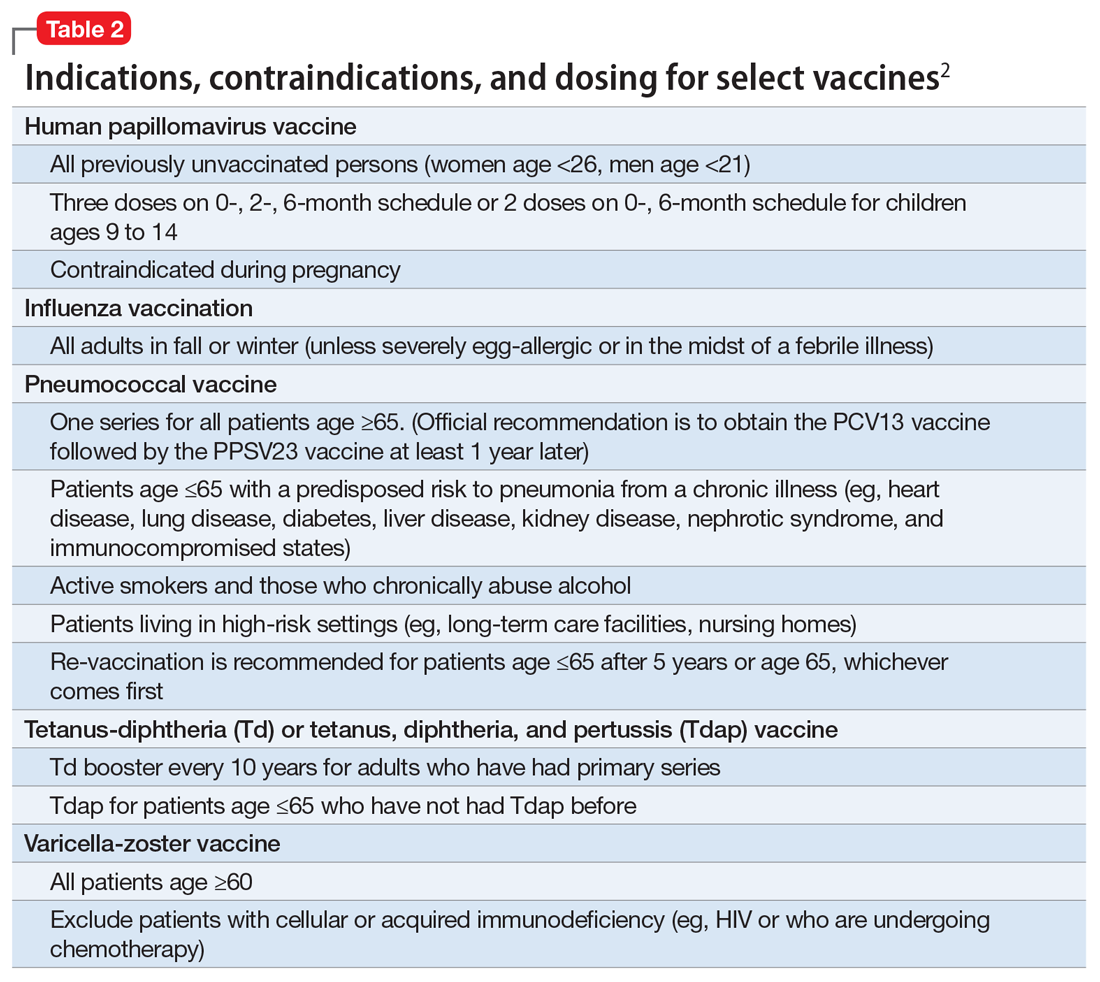

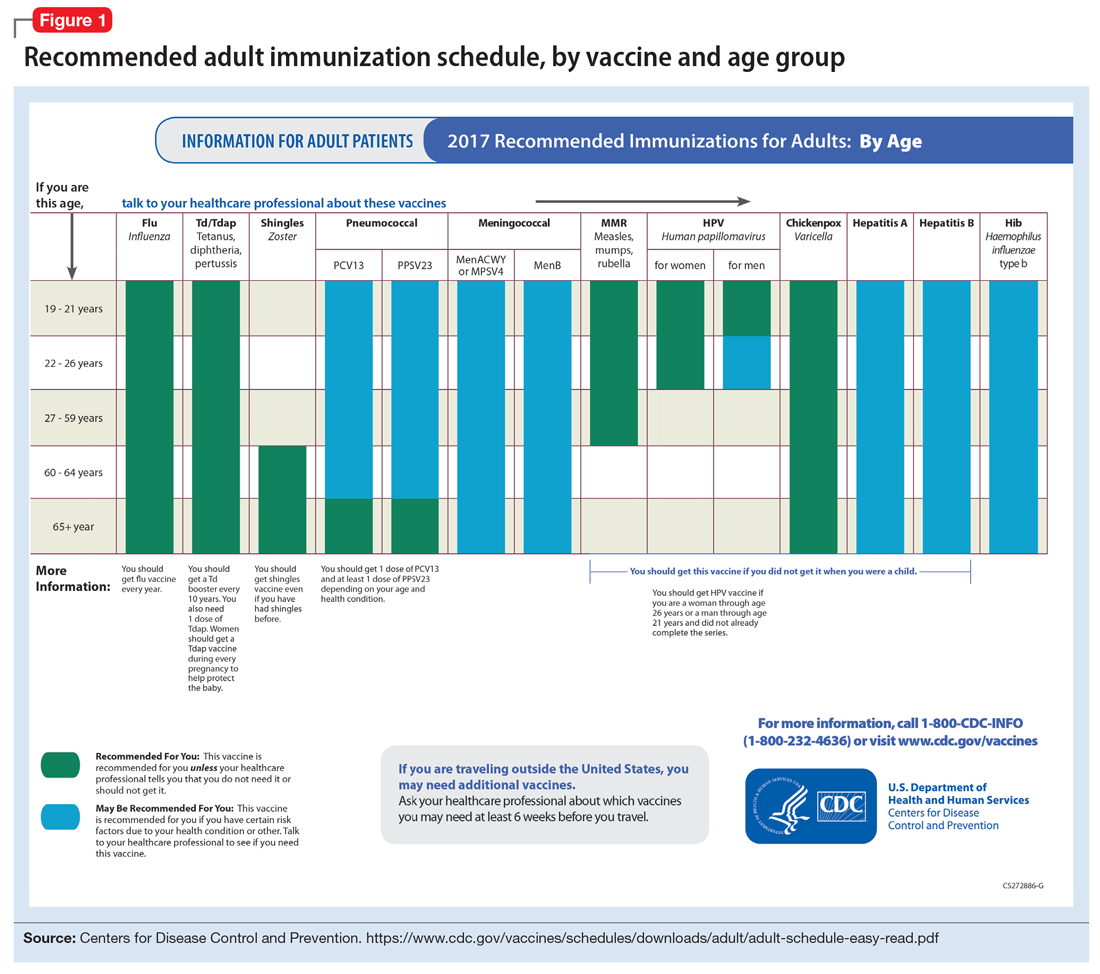

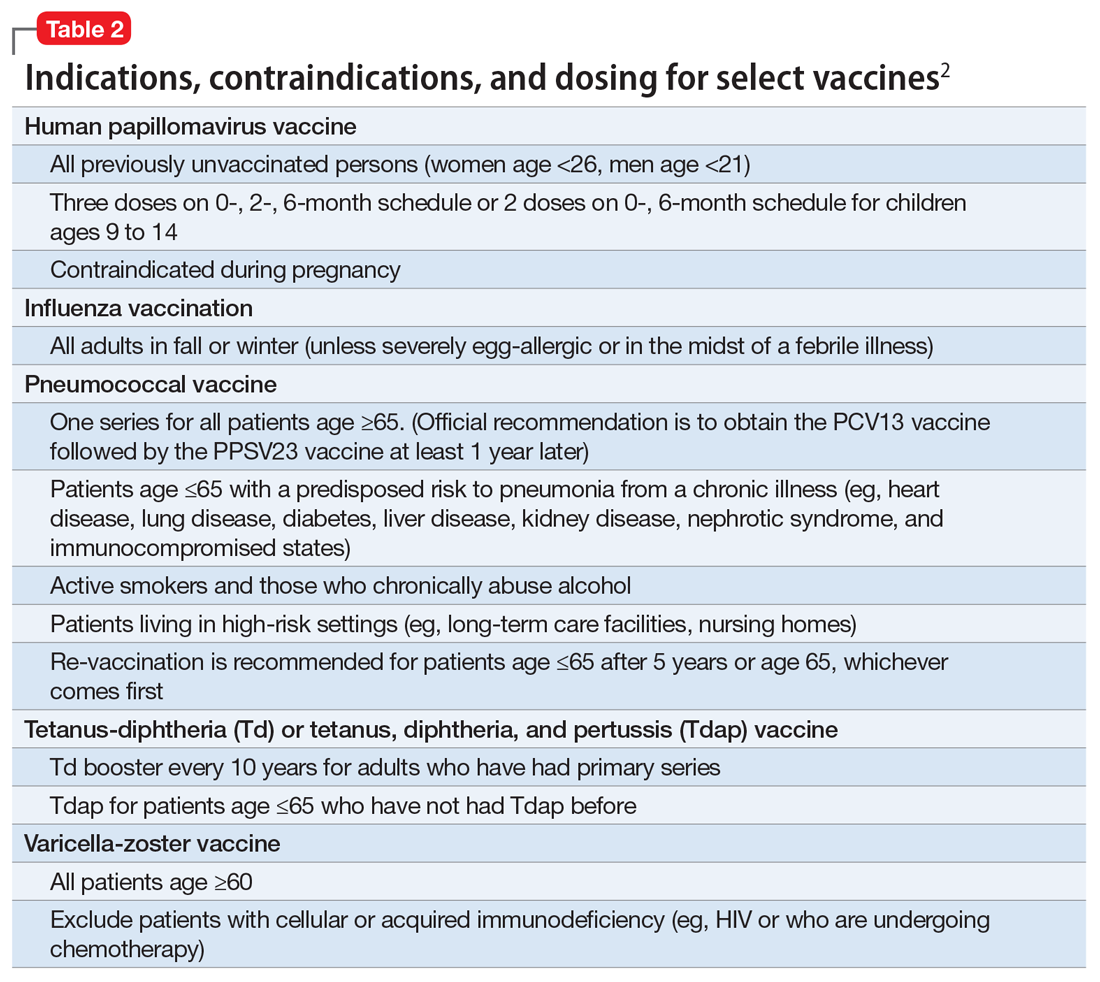

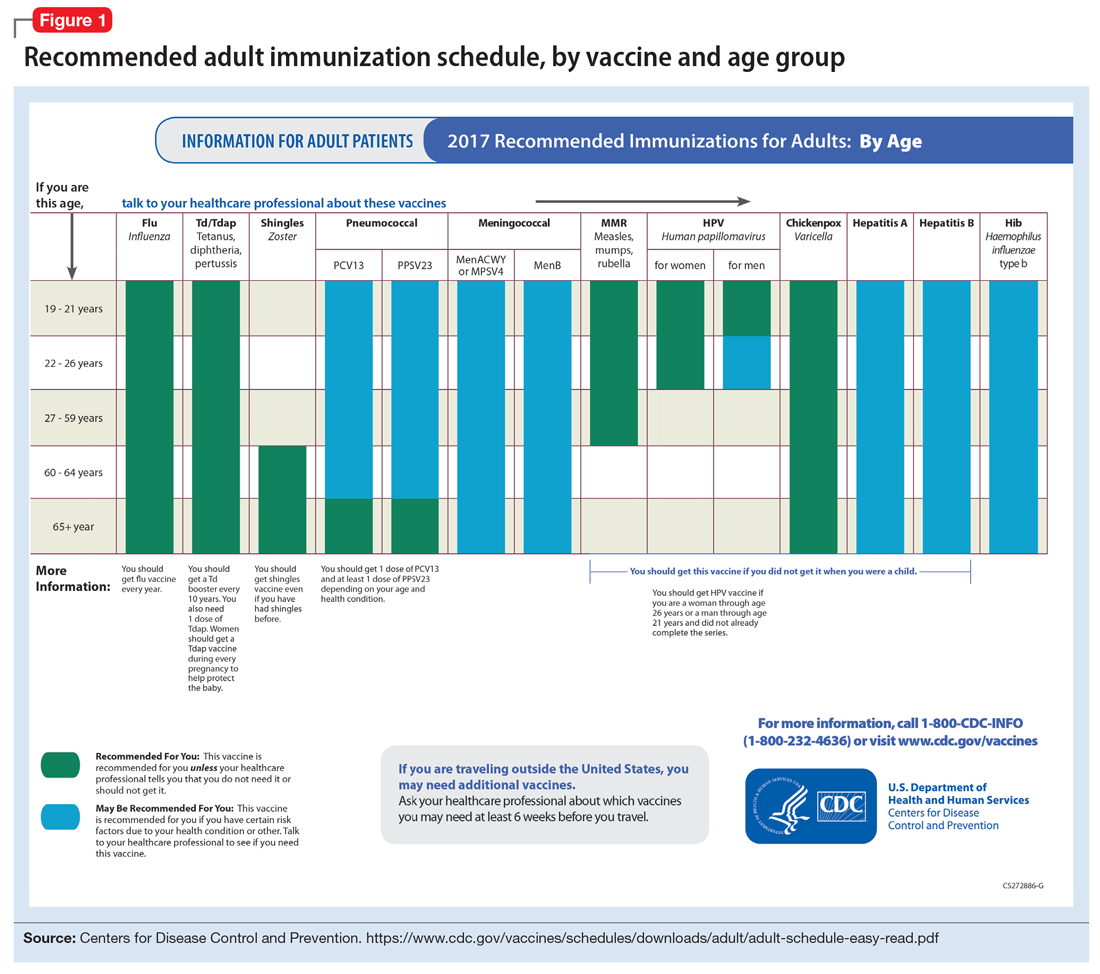

Age may be the most important determinant of a patient’s need for vaccination (Table 2). The CDC immunization schedules account for age-specific risks for diseases, complications, and responses to vaccination (Figure 1).6

Influenza vaccination. Adults can have an intramuscular or intradermal inactivated influenza vaccination yearly in the fall or winter, unless they have an allergy to a vaccine component such as egg protein. Those with such an allergy can receive a recombinant influenza vaccine. Until the 2016 to 2017 flu season, an intranasal mist of live, attenuated influenza vaccine was available to healthy, non-pregnant women, ages 2 to 49, without high-risk medical conditions. However, the CDC dropped its recommendation for this vaccine because data showed it did not effectively prevent the flu.7 Individuals age ≥65 can receive either the standard- or high-dose inactivated influenza vaccination. The latter contains 4 times the amount of antigen with the intention of triggering a stronger immune response in older adults.

Pneumonia immunization. All patients age ≥65 should receive vaccinations for Streptococcus pneumoniae and its variants in the form of one 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and, at least 1 year later, one 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). Immunization reduces the morbidity and mortality from pneumococcal illness by decreasing the burden of a pneumonia, bacteremia, or meningitis infection. Adults, ages 19 to 64, with a chronic disease (referred to as “special populations” in CDC tables), such as diabetes, heart or lung disease, alcoholism, or cirrhosis, or those who smoke cigarettes, should receive PPSV23 with a second dose administered at least 5 years after the first. The CDC recommends a 1-time re-vaccination at age 65 for patients if >5 years have passed since the last PPSV23 and if the patient was younger than age 65 at the time of primary vaccine for S. pneumoniae. This can be a rather tricky clinical situation; the health care provider should verify a patient’s immunization history to ensure that she (he) is receiving only necessary vaccines. However, when the history cannot be verified, err on the side of inclusion, because risks are minimal.

Shingles vaccination. Adults age ≥60 who are not immunocompromised should receive a single dose of live attenuated vaccine from varicella-zoster virus (VZV) to limit the risk of shingles from a prior chickenpox infection. The vaccine is approximately 66.5% effective at preventing postherpetic neuralgia for up to 4.9 years. Individuals as young as age 50 may have the vaccine because the risk of herpes zoster radically increases from then on,8 although most insurers only cover VZV vaccination after age 60.

Tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine. All adults should complete the 3-dose primary vaccination series for tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (also known as whooping cough) and this should include 1 dose of Tdap. Administration of the primary series is staged so that the second dose is given 4 weeks after the initial dose and the final dose 6 to 12 months after the first dose. After receiving the primary series, adults should receive a tetanus-diphtheria booster dose every 10 years. For adults ages 19 to 64, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends 1 dose of Tdap in place of a booster vaccination to decrease the transmission risk of pertussis to vulnerable persons, especially children.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) immunization. The ACIP recommendation9 has been for children to receive routine vaccination for the 4 major strains of HPV—strains 6, 11, 16, and 18—starting at ages 11 to 12 to confer protection from HPV-associated diseases, such as genital warts, oropharyngeal cancer, and anal cancer; cancers of the cervix, vulva, and vagina in women; and penile cancer in men. Ideally, the vaccines are administered prior to HPV exposure from sexual contact. The quadrivalent HPV vaccine is safe and is administered as a 3-dose series, with the second and third doses given 2 and 6 months, respectively, after the initial dose. Adolescent girls also have the option of a bivalent HPV vaccine.

In 2016, the FDA approved a 9-valent HPV vaccine, a simpler 2-dose schedule for children ages 9 to 14 (2 doses at least 6 months apart). Leading cancer centers have endorsed this vaccine based on strong comparative data with the 3-dose regimen.10 For those not previously vaccinated, the HPV vaccine is available for women ages 13 to 26 and for men ages 13 to 21 (although men ages 22 to 26 can receive the vaccine, and it is recommended for men who have sex with men [MSM]). Women do not require Papanicolaou, serum pregnancy, HPV DNA, or HPV antibody tests prior to vaccination. If a woman becomes pregnant, remaining doses of the vaccine should be postponed until after delivery. Women still need to follow recommendations for cervical cancer screening because the HPV vaccine does not cover all genital strains of the virus. For sexually active individuals who might have HPV or genital warts, immunization has no clinical effect except to prevent other HPV strains.

Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. All adults should receive, at minimum, 1 dose of MMR vaccination unless serological immunity can be verified or if contraindicated. Two doses of the vaccine are recommended for students attending post-high school institutions, health care personnel, and international travelers because they are at higher risk for exposure and transmission of measles and mumps. Individuals born before 1957 are considered immune to measles and mumps. A measles outbreak from December 2014 to February 201511 highlighted the importance of maintaining one’s immunity status for MMR.

Case continued

Based on Ms. W’s age, she should be offered vaccinations for influenza and opportunities to receive vaccinations for HPV, Tdap (the primary series, a Tdap or Td booster), and MMR, if appropriate and not completed previously.

Risk of exposure

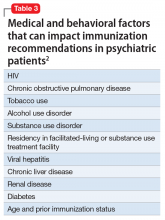

Certain behaviors will increase the risk of exposure to and transmission of diseases communicable by blood and other bodily fluids (Table 3). These behaviors include needle injections (eg, during use of illicit drugs) and sexual activity with multiple partners, including MSM or promiscuity/impulsivity during a manic episode. A common consequence of risky behaviors is comorbid infection of HIV and viral hepatitis for those with substance use disorder or those who engage in high-risk sexual practices.12,13

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) immunization. Vaccination is one of the most effective ways to prevent HBV infection, which is why it is offered to all health care workers. HBV immunization is a 3-dose series in which the second and third doses are given 1 and 6 months after the initial doses, respectively. In addition to certain medical risk factors or conditions that indicate HBV vaccination, people should be offered the vaccine if they are in a higher risk occupation, travel, are of Asian or Pacific Islander ethnicity from an endemic area, or have any present or suspected sexually transmitted diseases.

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) vaccination. HAV is transmitted via fecal–oral routes, often from contaminated water or food, or through household or sexual contact with an infected person. Individuals should receive the HAV vaccine if they use illicit drugs by any route of administration, work with primates infected with HAV, travel to countries with unknown or high rates of HAV, or have chronic liver disease (ie, hepatitis, alcohol use disorder, or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) or clotting deficiencies. The CDC Health Information for International Travel, commonly called the “Yellow Book,” publishes vaccination recommendations for those who plan travel to specific countries.14

Case continued

Ms. W’s history of mania (if such episodes included increased sexual activity) and substance use would make her a candidate for the HBV and HAV vaccinations and could also strengthen our previous recommendation that she receive the HPV vaccination.

Medical conditions

Patients with certain medical conditions may have difficulty fighting infections or become more susceptible to morbidity and mortality from coinfection with vaccine-preventable illnesses. Secondary effects of psychotropic medications that may carry implications for vaccine recommendations (eg, risk of agranulocytosis and impaired cell-medicated immunity with mirtazapine and clozapine or renal impairment from lithium use) are of particular concern in psychiatric patients.2

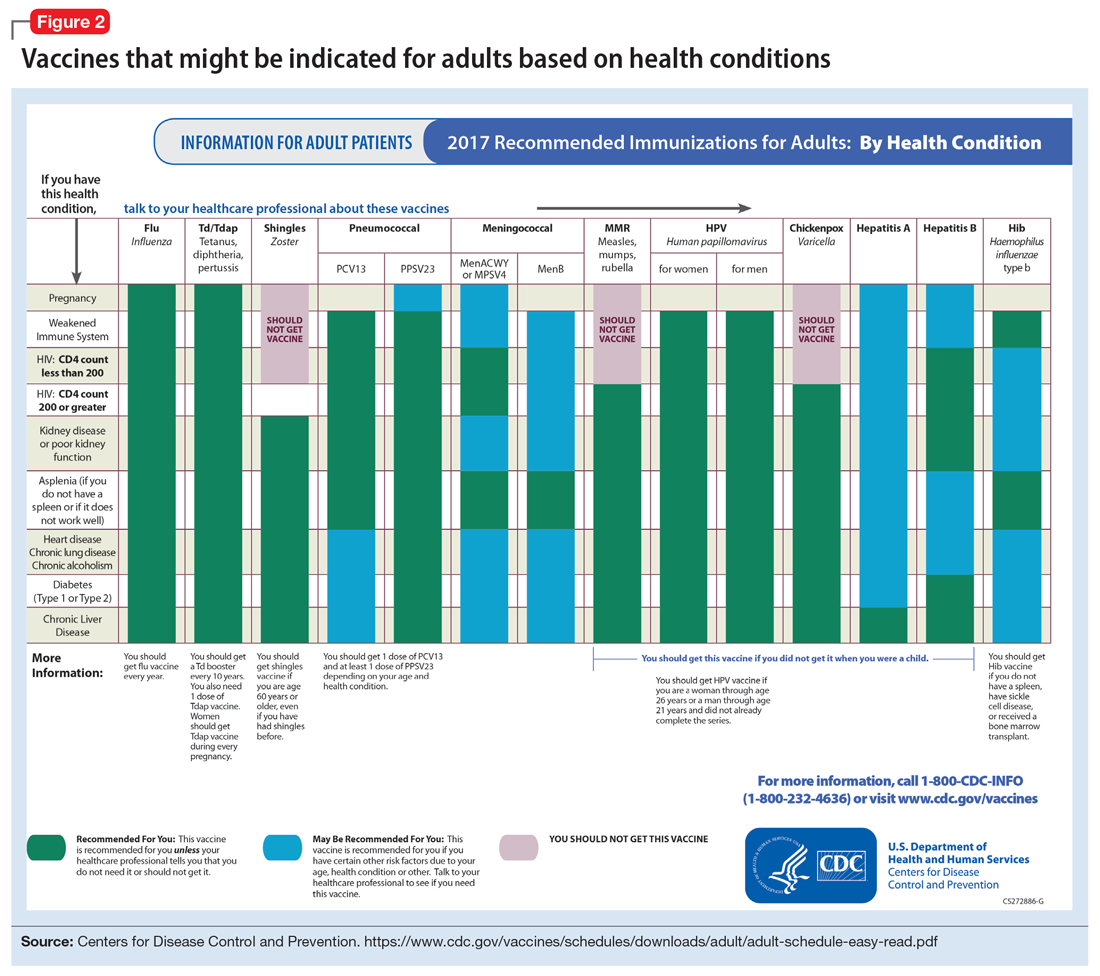

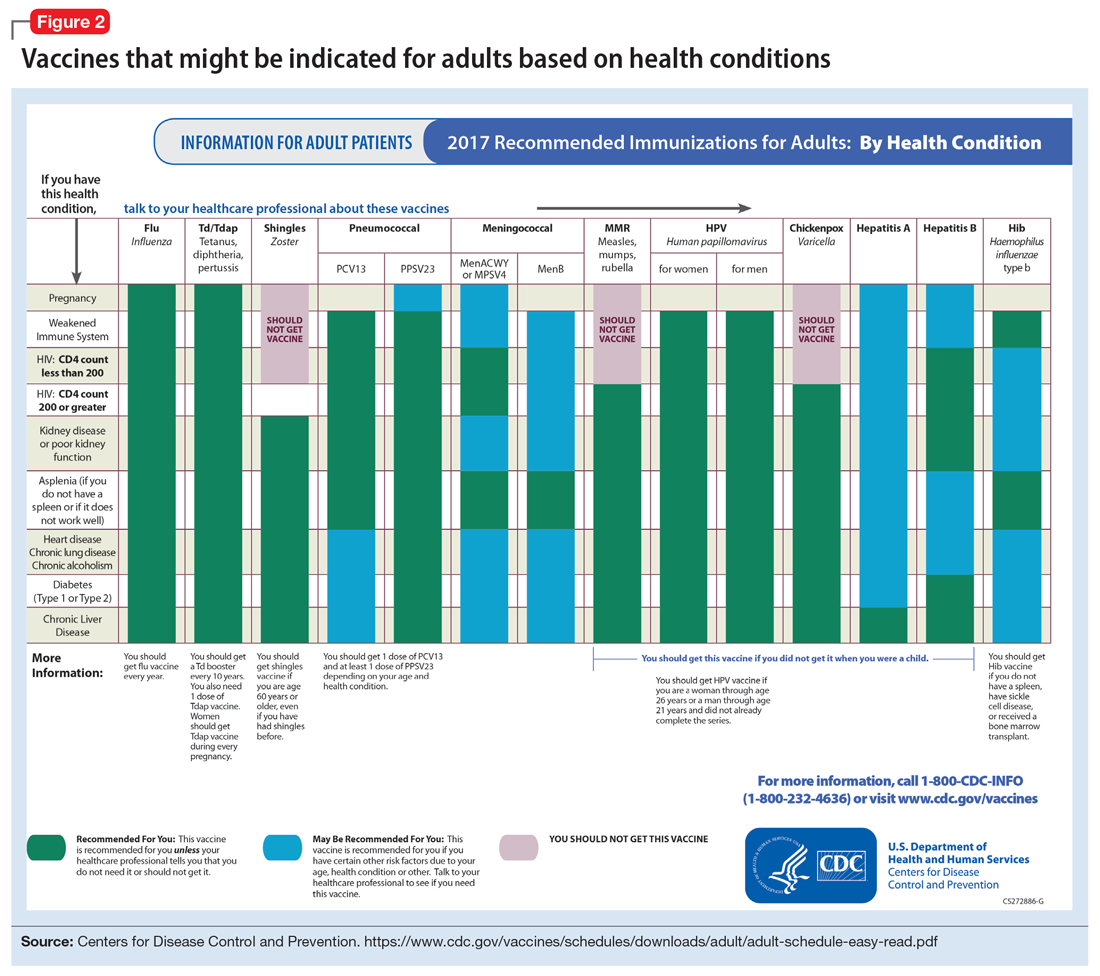

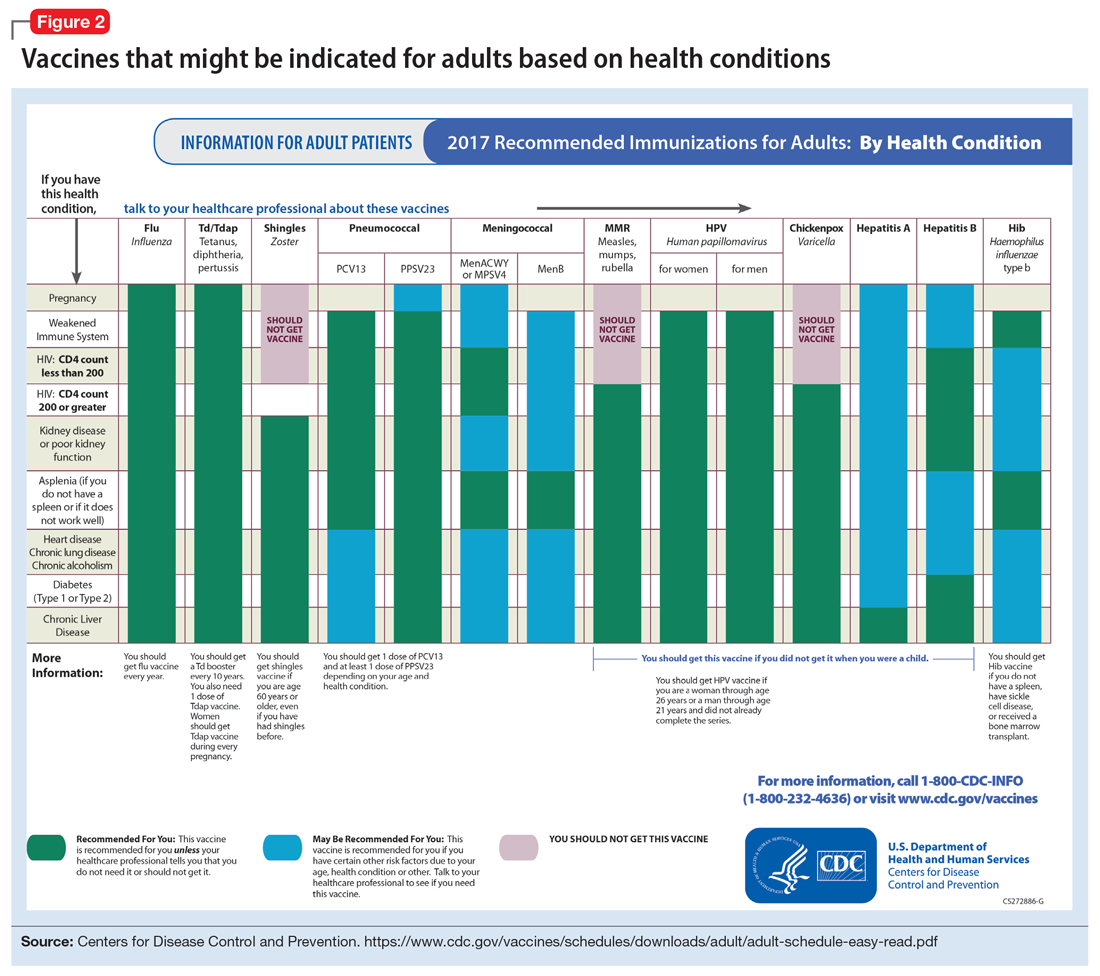

To help care for these patients, the CDC has developed a “medical conditions” schedule (Figure 2). This schedule makes vaccination recommendations for those with a weakened immune system, including patients with HIV, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, hepatitis, asplenia, end-stage renal disease, cardiac disease, and pregnancy.

Because patients with psychiatric illness face a greater risk of heart disease and diabetes, these conditions may warrant special reference on the schedule. The increased cardiometabolic risk factors in these patients may be due in part to genetics, socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviors, and medications to treat their mental illness (eg, antipsychotics). Patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in particular tend to have higher rates of COPD (mainly from chronic bronchitis) and asthma than the general population.12 Pay special attention to the indications schedule for those with chronic lung disease, especially patients who continue to smoke cigarettes.

Case continued

Because of Ms. W’s asthma, the CDC schedule recommends ensuring she is up to date on her influenza, pneumococcal, and Tdap vaccinations.

Substance use

Patients with combined psychiatric and substance use disorders (“dual diagnosis”) have lower rates of receiving preventive care than patients with either condition alone.15 Substance use can be behaviorally disinhibiting, leading to increased risk of exposures from sexual contact or other risky activities. The use of illicit substances can provide a nidus for infection depending on the route of administration and can result in negative effects on organ systems, compromising one’s ability to ward off infection.

Patients who use any illicit drugs, regardless of the method of delivery, should be recommended for HAV vaccination. For those with alcohol use disorder and/or chronic liver disease, and/or seeking treatment for substance use, hepatitis B screening and vaccination is recommended.

Case continued

From a substance use perspective, discussion of vaccination status for both hepatitis A and B would be important for Ms. W.

HIV or immunocompromised

Persons with severe mental illness have high rates of HIV, with almost 8 times the risk of exposure, compared with the general population due to myriad reasons, including greater rates of substance abuse, higher risk sexual behavior, and lack of awareness of HIV transmission.12,13 Patients with mental illness are also at risk of leukopenia and agranulocytosis from certain drugs used to treat their conditions, such as clozapine.

Pregnancy is a challenge for women with mental illness because of the pharmacologic risk and immune-system compromise to the mother and baby. A pregnant woman who has HIV with a CD4 count <200, or has a weakened immune system from an organ transplant or a similar condition, is a candidate for certain vaccines based on the Adult Immunization Schedule (Figure 2). However, these patients should avoid live vaccines, such as the intranasal mist of live influenza, MMR, VZV, and varicella, to avoid illness from these inoculations.

Case continued

Ms. W should undergo testing for pregnancy and HIV (and preferably other sexually transmitted infections per general preventive health guidelines) before receiving any live vaccinations.

Occupancy

Aside from direct transmission of bodily fluids, infectious diseases also can spread through droplets/secretions from the throat and respiratory tract. Close quarters or lengthy contact enhances communicability by droplets, and therefore people who reside in a communal living space (eg, individuals in substance use treatment facilities or those who reside in a nursing home) are most susceptible.

The bacterial disease Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) can spread through droplets and can cause pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis. Vaccination is indicated, and in some states is mandated, for college students who live in residence halls and missed routine vaccination by age 16. Meningococcus conjugate vaccine is administered in 2 doses; each dose may be given at least 2 months apart for those with HIV, asplenia, or persistent complement-related disorders. A single dose may be recommended for travelers to areas where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic, military recruits, or microbiologists. For those age ≥55 and older, meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine is recommended over meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

Influenza, MMR, diphtheria, pertussis, and pneumococcus also spread through droplet contact.

Case continued

If Ms. W had not previously received the meningococcus vaccine as part of adolescent immunizations, she could benefit from this vaccine because she plans to enter a residential substance use disorder treatment program.

Tobacco use

Patients with psychiatric illness are twice as likely to smoke compared with the general population.16 Adult smokers, especially those with chronic lung disease, are at higher risk for influenza and pneumococcal-related illness; they should be vaccinated against these illnesses regardless of age (as discussed in the “Age” section).

Case continued

Because she smokes, Ms. W should receive counseling on vaccinations, such as influenza and pneumonia, to lessen her risk of respiratory illnesses and downstream sepsis.

Conclusion

Ms. W’s case represents an unfortunately all-too-common scenario where her multifaceted biopsychosocial circumstances place her at high risk for vaccine-preventable conditions. Her weight is recorded and laboratory work ordered to evaluate her pregnancy status, blood counts, lipids, complete metabolic panel, lithium level, and HIV status. Fortunately, she had received her series of MMR, meningococcal, and Tdap vaccinations when she was younger. Influenza, HPV, HAV, HBV, and pneumococcal vaccinations were all recommended to her, all of which can be given on the same day (HAV and HBV often are available as a combined vaccine). Ms. W receives a renewal of her psychiatric medications and counseling on healthy living habits (eg, diet and exercise, quitting tobacco and alcohol use, and safe sex practices) and the importance of immunizations.

Vaccination is 1 of the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century when one considers how immunization of vaccine-preventable diseases has reduced morbidity, mortality, and health-associated costs.17 As mental health professionals, we can help pass on the direct and indirect benefits of immunizations to an often underserved and undertreated population to help improve their health outcomes and quality of life.

1. Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1794-1796.

2. Raj YP, Lloyd L. Adult immunizations. In: McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Keenan GR, et al, eds. Preventive medical care in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2015;215-227.

3. Young S, Dosani N, Whisler A, et al. Influenza vaccination rates among homeless adults with mental illness in Toronto. J Prim Care Community Health. 2015;6(3):211-214.

4. Kroger AT, Atkinson WL, Marcues EK, et al; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). General recommendations on immunization: recommendations on the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-15):1-48.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended Adult Immunization by Vaccine and Age Group. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html. Updated February 27, 2017. Accessed February 1, 2017.

6. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunization—recommendations on the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(2):1-64.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0622-laiv-flu.html. Updated June 22, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017.

8. Hales CM, Harpaz, R, Ortega-Sanchez I, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(33):729-731.

9. Petrosky E, Bocchini Jr JA, Hariri S, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccine recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(11)300-304.

10. Iversen OE, Miranda MJ, Ulied A, et al. Immunogenicity of the 9-valent HPV vaccine using 2-dose regimens in girls and boys vs a 3-dose regimen in women. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2411-2421.

11. Zipprich J, Winter K, Hacker J, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles outbreak—California, December 2014-February 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(6):153-154.

12. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77.

13. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31-37.

14. Centers for Disease for Control and Prevention. CDC yellow book 2018: health information for international travel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017.

15. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al. Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care. 2002;40(2):129-136.

16. Lasser K, Boyd J, Woolhandler S, et al. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606-2610.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ten great public health achievements—United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(19);619-623.

Patients with chronic, severe mental illness live much shorter lives than the general population. The 25-year loss in life expectancy for people with chronic mental illness has been attributed to higher rates of cardiovascular disease driven by increased smoking, obesity, poverty, and poor nutrition.1 These individuals also face the added burden of struggling with a psychiatric condition that often interferes with their ability to make optimal preventative health decisions, including staying up to date on vaccinations.2 A recent review from Toronto, Canada, found that the influenza vaccination rates among homeless adults with mental illness—a population at high risk of respiratory illness—was only 6.7% compared with 31.1% for the general population of Ontario.3

Mental health professionals may serve as the only contacts to offer medical care to this vulnerable population, leading some psychiatric leaders to advocate that psychiatrists be considered primary care providers within accountable care organizations. Because most vaccines are easily available, mental health professionals should know about key immunizations to guide their patients accordingly.

In the United States, approximately 45,000 adults die annually from vaccine-preventable diseases, the majority from influenza.4 When combined with the most recent Adult Immunization Schedule and general recommendations adapted from the CDC,5,6 the mnemonic ARM SHOT allows for a quick assessment of risk factors to guide administration and education about most vaccinations (Table 1). ARM SHOT involves assessing the following components of an individual’s health status and living arrangements to determine one’s risk of contracting communicable diseases:

- Age

- Risk of exposure

- Medical conditions (comorbidities)

- Substance use history

- HIV status or other immunocompromised states

- Occupancy, or living arrangements

- Tobacco use.

We recommend keeping a copy of the Adult Immunization Schedule (age ≥19) and/or the immunization schedule for children and adolescents (age ≤18) close for quick reference. Here, we provide a case and then explore how each component of the ARM SHOT mnemonic applies in decision-making.

Case Evaluating risk, assess needs

Ms. W, age 24, has bipolar I disorder, most recently manic with psychotic features. She presents for follow-up in clinic after a 5-day hospitalization for mania and comorbid alcohol use disorder. Her medical comorbidities include asthma and active tobacco use. She is taking lurasidone, 20 mg/d, and lithium, 900 mg/d. Her case manager is working to place Ms. W in a residential substance use disorder treatment program. Ms. W is on a waiting list to establish care with a primary care physician and has a history of poor engagement with medical services in general; prior attempts to place her with a primary care physician failed.

In advance of Ms. W’s transfer to a residential treatment facility, you have been asked to place a Mantoux screening test for tuberculosis (purified protein derivative), which raises the important question about her susceptibility to infectious diseases in general. To protect Ms. W from preventable diseases for which vaccines are available, you review the ARM SHOT mnemonic to broadly assess her candidacy for vaccinations.

Age

Age may be the most important determinant of a patient’s need for vaccination (Table 2). The CDC immunization schedules account for age-specific risks for diseases, complications, and responses to vaccination (Figure 1).6

Influenza vaccination. Adults can have an intramuscular or intradermal inactivated influenza vaccination yearly in the fall or winter, unless they have an allergy to a vaccine component such as egg protein. Those with such an allergy can receive a recombinant influenza vaccine. Until the 2016 to 2017 flu season, an intranasal mist of live, attenuated influenza vaccine was available to healthy, non-pregnant women, ages 2 to 49, without high-risk medical conditions. However, the CDC dropped its recommendation for this vaccine because data showed it did not effectively prevent the flu.7 Individuals age ≥65 can receive either the standard- or high-dose inactivated influenza vaccination. The latter contains 4 times the amount of antigen with the intention of triggering a stronger immune response in older adults.

Pneumonia immunization. All patients age ≥65 should receive vaccinations for Streptococcus pneumoniae and its variants in the form of one 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and, at least 1 year later, one 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). Immunization reduces the morbidity and mortality from pneumococcal illness by decreasing the burden of a pneumonia, bacteremia, or meningitis infection. Adults, ages 19 to 64, with a chronic disease (referred to as “special populations” in CDC tables), such as diabetes, heart or lung disease, alcoholism, or cirrhosis, or those who smoke cigarettes, should receive PPSV23 with a second dose administered at least 5 years after the first. The CDC recommends a 1-time re-vaccination at age 65 for patients if >5 years have passed since the last PPSV23 and if the patient was younger than age 65 at the time of primary vaccine for S. pneumoniae. This can be a rather tricky clinical situation; the health care provider should verify a patient’s immunization history to ensure that she (he) is receiving only necessary vaccines. However, when the history cannot be verified, err on the side of inclusion, because risks are minimal.

Shingles vaccination. Adults age ≥60 who are not immunocompromised should receive a single dose of live attenuated vaccine from varicella-zoster virus (VZV) to limit the risk of shingles from a prior chickenpox infection. The vaccine is approximately 66.5% effective at preventing postherpetic neuralgia for up to 4.9 years. Individuals as young as age 50 may have the vaccine because the risk of herpes zoster radically increases from then on,8 although most insurers only cover VZV vaccination after age 60.

Tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine. All adults should complete the 3-dose primary vaccination series for tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (also known as whooping cough) and this should include 1 dose of Tdap. Administration of the primary series is staged so that the second dose is given 4 weeks after the initial dose and the final dose 6 to 12 months after the first dose. After receiving the primary series, adults should receive a tetanus-diphtheria booster dose every 10 years. For adults ages 19 to 64, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends 1 dose of Tdap in place of a booster vaccination to decrease the transmission risk of pertussis to vulnerable persons, especially children.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) immunization. The ACIP recommendation9 has been for children to receive routine vaccination for the 4 major strains of HPV—strains 6, 11, 16, and 18—starting at ages 11 to 12 to confer protection from HPV-associated diseases, such as genital warts, oropharyngeal cancer, and anal cancer; cancers of the cervix, vulva, and vagina in women; and penile cancer in men. Ideally, the vaccines are administered prior to HPV exposure from sexual contact. The quadrivalent HPV vaccine is safe and is administered as a 3-dose series, with the second and third doses given 2 and 6 months, respectively, after the initial dose. Adolescent girls also have the option of a bivalent HPV vaccine.

In 2016, the FDA approved a 9-valent HPV vaccine, a simpler 2-dose schedule for children ages 9 to 14 (2 doses at least 6 months apart). Leading cancer centers have endorsed this vaccine based on strong comparative data with the 3-dose regimen.10 For those not previously vaccinated, the HPV vaccine is available for women ages 13 to 26 and for men ages 13 to 21 (although men ages 22 to 26 can receive the vaccine, and it is recommended for men who have sex with men [MSM]). Women do not require Papanicolaou, serum pregnancy, HPV DNA, or HPV antibody tests prior to vaccination. If a woman becomes pregnant, remaining doses of the vaccine should be postponed until after delivery. Women still need to follow recommendations for cervical cancer screening because the HPV vaccine does not cover all genital strains of the virus. For sexually active individuals who might have HPV or genital warts, immunization has no clinical effect except to prevent other HPV strains.

Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. All adults should receive, at minimum, 1 dose of MMR vaccination unless serological immunity can be verified or if contraindicated. Two doses of the vaccine are recommended for students attending post-high school institutions, health care personnel, and international travelers because they are at higher risk for exposure and transmission of measles and mumps. Individuals born before 1957 are considered immune to measles and mumps. A measles outbreak from December 2014 to February 201511 highlighted the importance of maintaining one’s immunity status for MMR.

Case continued

Based on Ms. W’s age, she should be offered vaccinations for influenza and opportunities to receive vaccinations for HPV, Tdap (the primary series, a Tdap or Td booster), and MMR, if appropriate and not completed previously.

Risk of exposure

Certain behaviors will increase the risk of exposure to and transmission of diseases communicable by blood and other bodily fluids (Table 3). These behaviors include needle injections (eg, during use of illicit drugs) and sexual activity with multiple partners, including MSM or promiscuity/impulsivity during a manic episode. A common consequence of risky behaviors is comorbid infection of HIV and viral hepatitis for those with substance use disorder or those who engage in high-risk sexual practices.12,13

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) immunization. Vaccination is one of the most effective ways to prevent HBV infection, which is why it is offered to all health care workers. HBV immunization is a 3-dose series in which the second and third doses are given 1 and 6 months after the initial doses, respectively. In addition to certain medical risk factors or conditions that indicate HBV vaccination, people should be offered the vaccine if they are in a higher risk occupation, travel, are of Asian or Pacific Islander ethnicity from an endemic area, or have any present or suspected sexually transmitted diseases.

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) vaccination. HAV is transmitted via fecal–oral routes, often from contaminated water or food, or through household or sexual contact with an infected person. Individuals should receive the HAV vaccine if they use illicit drugs by any route of administration, work with primates infected with HAV, travel to countries with unknown or high rates of HAV, or have chronic liver disease (ie, hepatitis, alcohol use disorder, or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) or clotting deficiencies. The CDC Health Information for International Travel, commonly called the “Yellow Book,” publishes vaccination recommendations for those who plan travel to specific countries.14

Case continued

Ms. W’s history of mania (if such episodes included increased sexual activity) and substance use would make her a candidate for the HBV and HAV vaccinations and could also strengthen our previous recommendation that she receive the HPV vaccination.

Medical conditions

Patients with certain medical conditions may have difficulty fighting infections or become more susceptible to morbidity and mortality from coinfection with vaccine-preventable illnesses. Secondary effects of psychotropic medications that may carry implications for vaccine recommendations (eg, risk of agranulocytosis and impaired cell-medicated immunity with mirtazapine and clozapine or renal impairment from lithium use) are of particular concern in psychiatric patients.2

To help care for these patients, the CDC has developed a “medical conditions” schedule (Figure 2). This schedule makes vaccination recommendations for those with a weakened immune system, including patients with HIV, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, hepatitis, asplenia, end-stage renal disease, cardiac disease, and pregnancy.

Because patients with psychiatric illness face a greater risk of heart disease and diabetes, these conditions may warrant special reference on the schedule. The increased cardiometabolic risk factors in these patients may be due in part to genetics, socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviors, and medications to treat their mental illness (eg, antipsychotics). Patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in particular tend to have higher rates of COPD (mainly from chronic bronchitis) and asthma than the general population.12 Pay special attention to the indications schedule for those with chronic lung disease, especially patients who continue to smoke cigarettes.

Case continued

Because of Ms. W’s asthma, the CDC schedule recommends ensuring she is up to date on her influenza, pneumococcal, and Tdap vaccinations.

Substance use

Patients with combined psychiatric and substance use disorders (“dual diagnosis”) have lower rates of receiving preventive care than patients with either condition alone.15 Substance use can be behaviorally disinhibiting, leading to increased risk of exposures from sexual contact or other risky activities. The use of illicit substances can provide a nidus for infection depending on the route of administration and can result in negative effects on organ systems, compromising one’s ability to ward off infection.

Patients who use any illicit drugs, regardless of the method of delivery, should be recommended for HAV vaccination. For those with alcohol use disorder and/or chronic liver disease, and/or seeking treatment for substance use, hepatitis B screening and vaccination is recommended.

Case continued

From a substance use perspective, discussion of vaccination status for both hepatitis A and B would be important for Ms. W.

HIV or immunocompromised

Persons with severe mental illness have high rates of HIV, with almost 8 times the risk of exposure, compared with the general population due to myriad reasons, including greater rates of substance abuse, higher risk sexual behavior, and lack of awareness of HIV transmission.12,13 Patients with mental illness are also at risk of leukopenia and agranulocytosis from certain drugs used to treat their conditions, such as clozapine.

Pregnancy is a challenge for women with mental illness because of the pharmacologic risk and immune-system compromise to the mother and baby. A pregnant woman who has HIV with a CD4 count <200, or has a weakened immune system from an organ transplant or a similar condition, is a candidate for certain vaccines based on the Adult Immunization Schedule (Figure 2). However, these patients should avoid live vaccines, such as the intranasal mist of live influenza, MMR, VZV, and varicella, to avoid illness from these inoculations.

Case continued

Ms. W should undergo testing for pregnancy and HIV (and preferably other sexually transmitted infections per general preventive health guidelines) before receiving any live vaccinations.

Occupancy

Aside from direct transmission of bodily fluids, infectious diseases also can spread through droplets/secretions from the throat and respiratory tract. Close quarters or lengthy contact enhances communicability by droplets, and therefore people who reside in a communal living space (eg, individuals in substance use treatment facilities or those who reside in a nursing home) are most susceptible.

The bacterial disease Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) can spread through droplets and can cause pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis. Vaccination is indicated, and in some states is mandated, for college students who live in residence halls and missed routine vaccination by age 16. Meningococcus conjugate vaccine is administered in 2 doses; each dose may be given at least 2 months apart for those with HIV, asplenia, or persistent complement-related disorders. A single dose may be recommended for travelers to areas where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic, military recruits, or microbiologists. For those age ≥55 and older, meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine is recommended over meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

Influenza, MMR, diphtheria, pertussis, and pneumococcus also spread through droplet contact.

Case continued

If Ms. W had not previously received the meningococcus vaccine as part of adolescent immunizations, she could benefit from this vaccine because she plans to enter a residential substance use disorder treatment program.

Tobacco use

Patients with psychiatric illness are twice as likely to smoke compared with the general population.16 Adult smokers, especially those with chronic lung disease, are at higher risk for influenza and pneumococcal-related illness; they should be vaccinated against these illnesses regardless of age (as discussed in the “Age” section).

Case continued

Because she smokes, Ms. W should receive counseling on vaccinations, such as influenza and pneumonia, to lessen her risk of respiratory illnesses and downstream sepsis.

Conclusion

Ms. W’s case represents an unfortunately all-too-common scenario where her multifaceted biopsychosocial circumstances place her at high risk for vaccine-preventable conditions. Her weight is recorded and laboratory work ordered to evaluate her pregnancy status, blood counts, lipids, complete metabolic panel, lithium level, and HIV status. Fortunately, she had received her series of MMR, meningococcal, and Tdap vaccinations when she was younger. Influenza, HPV, HAV, HBV, and pneumococcal vaccinations were all recommended to her, all of which can be given on the same day (HAV and HBV often are available as a combined vaccine). Ms. W receives a renewal of her psychiatric medications and counseling on healthy living habits (eg, diet and exercise, quitting tobacco and alcohol use, and safe sex practices) and the importance of immunizations.

Vaccination is 1 of the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century when one considers how immunization of vaccine-preventable diseases has reduced morbidity, mortality, and health-associated costs.17 As mental health professionals, we can help pass on the direct and indirect benefits of immunizations to an often underserved and undertreated population to help improve their health outcomes and quality of life.

Patients with chronic, severe mental illness live much shorter lives than the general population. The 25-year loss in life expectancy for people with chronic mental illness has been attributed to higher rates of cardiovascular disease driven by increased smoking, obesity, poverty, and poor nutrition.1 These individuals also face the added burden of struggling with a psychiatric condition that often interferes with their ability to make optimal preventative health decisions, including staying up to date on vaccinations.2 A recent review from Toronto, Canada, found that the influenza vaccination rates among homeless adults with mental illness—a population at high risk of respiratory illness—was only 6.7% compared with 31.1% for the general population of Ontario.3

Mental health professionals may serve as the only contacts to offer medical care to this vulnerable population, leading some psychiatric leaders to advocate that psychiatrists be considered primary care providers within accountable care organizations. Because most vaccines are easily available, mental health professionals should know about key immunizations to guide their patients accordingly.

In the United States, approximately 45,000 adults die annually from vaccine-preventable diseases, the majority from influenza.4 When combined with the most recent Adult Immunization Schedule and general recommendations adapted from the CDC,5,6 the mnemonic ARM SHOT allows for a quick assessment of risk factors to guide administration and education about most vaccinations (Table 1). ARM SHOT involves assessing the following components of an individual’s health status and living arrangements to determine one’s risk of contracting communicable diseases:

- Age

- Risk of exposure

- Medical conditions (comorbidities)

- Substance use history

- HIV status or other immunocompromised states

- Occupancy, or living arrangements

- Tobacco use.

We recommend keeping a copy of the Adult Immunization Schedule (age ≥19) and/or the immunization schedule for children and adolescents (age ≤18) close for quick reference. Here, we provide a case and then explore how each component of the ARM SHOT mnemonic applies in decision-making.

Case Evaluating risk, assess needs

Ms. W, age 24, has bipolar I disorder, most recently manic with psychotic features. She presents for follow-up in clinic after a 5-day hospitalization for mania and comorbid alcohol use disorder. Her medical comorbidities include asthma and active tobacco use. She is taking lurasidone, 20 mg/d, and lithium, 900 mg/d. Her case manager is working to place Ms. W in a residential substance use disorder treatment program. Ms. W is on a waiting list to establish care with a primary care physician and has a history of poor engagement with medical services in general; prior attempts to place her with a primary care physician failed.

In advance of Ms. W’s transfer to a residential treatment facility, you have been asked to place a Mantoux screening test for tuberculosis (purified protein derivative), which raises the important question about her susceptibility to infectious diseases in general. To protect Ms. W from preventable diseases for which vaccines are available, you review the ARM SHOT mnemonic to broadly assess her candidacy for vaccinations.

Age

Age may be the most important determinant of a patient’s need for vaccination (Table 2). The CDC immunization schedules account for age-specific risks for diseases, complications, and responses to vaccination (Figure 1).6

Influenza vaccination. Adults can have an intramuscular or intradermal inactivated influenza vaccination yearly in the fall or winter, unless they have an allergy to a vaccine component such as egg protein. Those with such an allergy can receive a recombinant influenza vaccine. Until the 2016 to 2017 flu season, an intranasal mist of live, attenuated influenza vaccine was available to healthy, non-pregnant women, ages 2 to 49, without high-risk medical conditions. However, the CDC dropped its recommendation for this vaccine because data showed it did not effectively prevent the flu.7 Individuals age ≥65 can receive either the standard- or high-dose inactivated influenza vaccination. The latter contains 4 times the amount of antigen with the intention of triggering a stronger immune response in older adults.

Pneumonia immunization. All patients age ≥65 should receive vaccinations for Streptococcus pneumoniae and its variants in the form of one 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and, at least 1 year later, one 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). Immunization reduces the morbidity and mortality from pneumococcal illness by decreasing the burden of a pneumonia, bacteremia, or meningitis infection. Adults, ages 19 to 64, with a chronic disease (referred to as “special populations” in CDC tables), such as diabetes, heart or lung disease, alcoholism, or cirrhosis, or those who smoke cigarettes, should receive PPSV23 with a second dose administered at least 5 years after the first. The CDC recommends a 1-time re-vaccination at age 65 for patients if >5 years have passed since the last PPSV23 and if the patient was younger than age 65 at the time of primary vaccine for S. pneumoniae. This can be a rather tricky clinical situation; the health care provider should verify a patient’s immunization history to ensure that she (he) is receiving only necessary vaccines. However, when the history cannot be verified, err on the side of inclusion, because risks are minimal.

Shingles vaccination. Adults age ≥60 who are not immunocompromised should receive a single dose of live attenuated vaccine from varicella-zoster virus (VZV) to limit the risk of shingles from a prior chickenpox infection. The vaccine is approximately 66.5% effective at preventing postherpetic neuralgia for up to 4.9 years. Individuals as young as age 50 may have the vaccine because the risk of herpes zoster radically increases from then on,8 although most insurers only cover VZV vaccination after age 60.

Tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine. All adults should complete the 3-dose primary vaccination series for tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (also known as whooping cough) and this should include 1 dose of Tdap. Administration of the primary series is staged so that the second dose is given 4 weeks after the initial dose and the final dose 6 to 12 months after the first dose. After receiving the primary series, adults should receive a tetanus-diphtheria booster dose every 10 years. For adults ages 19 to 64, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends 1 dose of Tdap in place of a booster vaccination to decrease the transmission risk of pertussis to vulnerable persons, especially children.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) immunization. The ACIP recommendation9 has been for children to receive routine vaccination for the 4 major strains of HPV—strains 6, 11, 16, and 18—starting at ages 11 to 12 to confer protection from HPV-associated diseases, such as genital warts, oropharyngeal cancer, and anal cancer; cancers of the cervix, vulva, and vagina in women; and penile cancer in men. Ideally, the vaccines are administered prior to HPV exposure from sexual contact. The quadrivalent HPV vaccine is safe and is administered as a 3-dose series, with the second and third doses given 2 and 6 months, respectively, after the initial dose. Adolescent girls also have the option of a bivalent HPV vaccine.

In 2016, the FDA approved a 9-valent HPV vaccine, a simpler 2-dose schedule for children ages 9 to 14 (2 doses at least 6 months apart). Leading cancer centers have endorsed this vaccine based on strong comparative data with the 3-dose regimen.10 For those not previously vaccinated, the HPV vaccine is available for women ages 13 to 26 and for men ages 13 to 21 (although men ages 22 to 26 can receive the vaccine, and it is recommended for men who have sex with men [MSM]). Women do not require Papanicolaou, serum pregnancy, HPV DNA, or HPV antibody tests prior to vaccination. If a woman becomes pregnant, remaining doses of the vaccine should be postponed until after delivery. Women still need to follow recommendations for cervical cancer screening because the HPV vaccine does not cover all genital strains of the virus. For sexually active individuals who might have HPV or genital warts, immunization has no clinical effect except to prevent other HPV strains.

Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. All adults should receive, at minimum, 1 dose of MMR vaccination unless serological immunity can be verified or if contraindicated. Two doses of the vaccine are recommended for students attending post-high school institutions, health care personnel, and international travelers because they are at higher risk for exposure and transmission of measles and mumps. Individuals born before 1957 are considered immune to measles and mumps. A measles outbreak from December 2014 to February 201511 highlighted the importance of maintaining one’s immunity status for MMR.

Case continued

Based on Ms. W’s age, she should be offered vaccinations for influenza and opportunities to receive vaccinations for HPV, Tdap (the primary series, a Tdap or Td booster), and MMR, if appropriate and not completed previously.

Risk of exposure

Certain behaviors will increase the risk of exposure to and transmission of diseases communicable by blood and other bodily fluids (Table 3). These behaviors include needle injections (eg, during use of illicit drugs) and sexual activity with multiple partners, including MSM or promiscuity/impulsivity during a manic episode. A common consequence of risky behaviors is comorbid infection of HIV and viral hepatitis for those with substance use disorder or those who engage in high-risk sexual practices.12,13

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) immunization. Vaccination is one of the most effective ways to prevent HBV infection, which is why it is offered to all health care workers. HBV immunization is a 3-dose series in which the second and third doses are given 1 and 6 months after the initial doses, respectively. In addition to certain medical risk factors or conditions that indicate HBV vaccination, people should be offered the vaccine if they are in a higher risk occupation, travel, are of Asian or Pacific Islander ethnicity from an endemic area, or have any present or suspected sexually transmitted diseases.

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) vaccination. HAV is transmitted via fecal–oral routes, often from contaminated water or food, or through household or sexual contact with an infected person. Individuals should receive the HAV vaccine if they use illicit drugs by any route of administration, work with primates infected with HAV, travel to countries with unknown or high rates of HAV, or have chronic liver disease (ie, hepatitis, alcohol use disorder, or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) or clotting deficiencies. The CDC Health Information for International Travel, commonly called the “Yellow Book,” publishes vaccination recommendations for those who plan travel to specific countries.14

Case continued

Ms. W’s history of mania (if such episodes included increased sexual activity) and substance use would make her a candidate for the HBV and HAV vaccinations and could also strengthen our previous recommendation that she receive the HPV vaccination.

Medical conditions

Patients with certain medical conditions may have difficulty fighting infections or become more susceptible to morbidity and mortality from coinfection with vaccine-preventable illnesses. Secondary effects of psychotropic medications that may carry implications for vaccine recommendations (eg, risk of agranulocytosis and impaired cell-medicated immunity with mirtazapine and clozapine or renal impairment from lithium use) are of particular concern in psychiatric patients.2

To help care for these patients, the CDC has developed a “medical conditions” schedule (Figure 2). This schedule makes vaccination recommendations for those with a weakened immune system, including patients with HIV, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, hepatitis, asplenia, end-stage renal disease, cardiac disease, and pregnancy.

Because patients with psychiatric illness face a greater risk of heart disease and diabetes, these conditions may warrant special reference on the schedule. The increased cardiometabolic risk factors in these patients may be due in part to genetics, socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviors, and medications to treat their mental illness (eg, antipsychotics). Patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in particular tend to have higher rates of COPD (mainly from chronic bronchitis) and asthma than the general population.12 Pay special attention to the indications schedule for those with chronic lung disease, especially patients who continue to smoke cigarettes.

Case continued

Because of Ms. W’s asthma, the CDC schedule recommends ensuring she is up to date on her influenza, pneumococcal, and Tdap vaccinations.

Substance use

Patients with combined psychiatric and substance use disorders (“dual diagnosis”) have lower rates of receiving preventive care than patients with either condition alone.15 Substance use can be behaviorally disinhibiting, leading to increased risk of exposures from sexual contact or other risky activities. The use of illicit substances can provide a nidus for infection depending on the route of administration and can result in negative effects on organ systems, compromising one’s ability to ward off infection.

Patients who use any illicit drugs, regardless of the method of delivery, should be recommended for HAV vaccination. For those with alcohol use disorder and/or chronic liver disease, and/or seeking treatment for substance use, hepatitis B screening and vaccination is recommended.

Case continued

From a substance use perspective, discussion of vaccination status for both hepatitis A and B would be important for Ms. W.

HIV or immunocompromised

Persons with severe mental illness have high rates of HIV, with almost 8 times the risk of exposure, compared with the general population due to myriad reasons, including greater rates of substance abuse, higher risk sexual behavior, and lack of awareness of HIV transmission.12,13 Patients with mental illness are also at risk of leukopenia and agranulocytosis from certain drugs used to treat their conditions, such as clozapine.

Pregnancy is a challenge for women with mental illness because of the pharmacologic risk and immune-system compromise to the mother and baby. A pregnant woman who has HIV with a CD4 count <200, or has a weakened immune system from an organ transplant or a similar condition, is a candidate for certain vaccines based on the Adult Immunization Schedule (Figure 2). However, these patients should avoid live vaccines, such as the intranasal mist of live influenza, MMR, VZV, and varicella, to avoid illness from these inoculations.

Case continued

Ms. W should undergo testing for pregnancy and HIV (and preferably other sexually transmitted infections per general preventive health guidelines) before receiving any live vaccinations.

Occupancy

Aside from direct transmission of bodily fluids, infectious diseases also can spread through droplets/secretions from the throat and respiratory tract. Close quarters or lengthy contact enhances communicability by droplets, and therefore people who reside in a communal living space (eg, individuals in substance use treatment facilities or those who reside in a nursing home) are most susceptible.

The bacterial disease Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) can spread through droplets and can cause pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis. Vaccination is indicated, and in some states is mandated, for college students who live in residence halls and missed routine vaccination by age 16. Meningococcus conjugate vaccine is administered in 2 doses; each dose may be given at least 2 months apart for those with HIV, asplenia, or persistent complement-related disorders. A single dose may be recommended for travelers to areas where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic, military recruits, or microbiologists. For those age ≥55 and older, meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine is recommended over meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

Influenza, MMR, diphtheria, pertussis, and pneumococcus also spread through droplet contact.

Case continued

If Ms. W had not previously received the meningococcus vaccine as part of adolescent immunizations, she could benefit from this vaccine because she plans to enter a residential substance use disorder treatment program.

Tobacco use

Patients with psychiatric illness are twice as likely to smoke compared with the general population.16 Adult smokers, especially those with chronic lung disease, are at higher risk for influenza and pneumococcal-related illness; they should be vaccinated against these illnesses regardless of age (as discussed in the “Age” section).

Case continued

Because she smokes, Ms. W should receive counseling on vaccinations, such as influenza and pneumonia, to lessen her risk of respiratory illnesses and downstream sepsis.

Conclusion

Ms. W’s case represents an unfortunately all-too-common scenario where her multifaceted biopsychosocial circumstances place her at high risk for vaccine-preventable conditions. Her weight is recorded and laboratory work ordered to evaluate her pregnancy status, blood counts, lipids, complete metabolic panel, lithium level, and HIV status. Fortunately, she had received her series of MMR, meningococcal, and Tdap vaccinations when she was younger. Influenza, HPV, HAV, HBV, and pneumococcal vaccinations were all recommended to her, all of which can be given on the same day (HAV and HBV often are available as a combined vaccine). Ms. W receives a renewal of her psychiatric medications and counseling on healthy living habits (eg, diet and exercise, quitting tobacco and alcohol use, and safe sex practices) and the importance of immunizations.

Vaccination is 1 of the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century when one considers how immunization of vaccine-preventable diseases has reduced morbidity, mortality, and health-associated costs.17 As mental health professionals, we can help pass on the direct and indirect benefits of immunizations to an often underserved and undertreated population to help improve their health outcomes and quality of life.

1. Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1794-1796.

2. Raj YP, Lloyd L. Adult immunizations. In: McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Keenan GR, et al, eds. Preventive medical care in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2015;215-227.

3. Young S, Dosani N, Whisler A, et al. Influenza vaccination rates among homeless adults with mental illness in Toronto. J Prim Care Community Health. 2015;6(3):211-214.

4. Kroger AT, Atkinson WL, Marcues EK, et al; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). General recommendations on immunization: recommendations on the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-15):1-48.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended Adult Immunization by Vaccine and Age Group. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html. Updated February 27, 2017. Accessed February 1, 2017.

6. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunization—recommendations on the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(2):1-64.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0622-laiv-flu.html. Updated June 22, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017.

8. Hales CM, Harpaz, R, Ortega-Sanchez I, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(33):729-731.

9. Petrosky E, Bocchini Jr JA, Hariri S, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccine recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(11)300-304.

10. Iversen OE, Miranda MJ, Ulied A, et al. Immunogenicity of the 9-valent HPV vaccine using 2-dose regimens in girls and boys vs a 3-dose regimen in women. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2411-2421.

11. Zipprich J, Winter K, Hacker J, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles outbreak—California, December 2014-February 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(6):153-154.

12. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77.

13. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31-37.

14. Centers for Disease for Control and Prevention. CDC yellow book 2018: health information for international travel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017.

15. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al. Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care. 2002;40(2):129-136.

16. Lasser K, Boyd J, Woolhandler S, et al. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606-2610.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ten great public health achievements—United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(19);619-623.

1. Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1794-1796.

2. Raj YP, Lloyd L. Adult immunizations. In: McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Keenan GR, et al, eds. Preventive medical care in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2015;215-227.

3. Young S, Dosani N, Whisler A, et al. Influenza vaccination rates among homeless adults with mental illness in Toronto. J Prim Care Community Health. 2015;6(3):211-214.

4. Kroger AT, Atkinson WL, Marcues EK, et al; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). General recommendations on immunization: recommendations on the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-15):1-48.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended Adult Immunization by Vaccine and Age Group. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html. Updated February 27, 2017. Accessed February 1, 2017.

6. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunization—recommendations on the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(2):1-64.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0622-laiv-flu.html. Updated June 22, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017.

8. Hales CM, Harpaz, R, Ortega-Sanchez I, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(33):729-731.

9. Petrosky E, Bocchini Jr JA, Hariri S, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccine recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(11)300-304.

10. Iversen OE, Miranda MJ, Ulied A, et al. Immunogenicity of the 9-valent HPV vaccine using 2-dose regimens in girls and boys vs a 3-dose regimen in women. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2411-2421.

11. Zipprich J, Winter K, Hacker J, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles outbreak—California, December 2014-February 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(6):153-154.

12. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77.

13. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31-37.

14. Centers for Disease for Control and Prevention. CDC yellow book 2018: health information for international travel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017.

15. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al. Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care. 2002;40(2):129-136.

16. Lasser K, Boyd J, Woolhandler S, et al. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606-2610.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ten great public health achievements—United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(19);619-623.

Memory problems: How best to assess and address

Memory disorders

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Clearing up confusion

“Mr. Smith seems somewhat confused today” is one of the most serious and concerning pre-visit reports you can receive from your staff or the patient’s family. Such a descriptor can be confusing—pardon the pun—not only for the patient, but to even seasoned mental health providers.

The term confusion can be code for diagnoses ranging from deliriuma to a progressive neurocognitive disorder (NCD) such as major NCD due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or even a more challenging problem such as beclouded dementia (delirium superimposed on dementia/NCD). It is essential for all mental health professionals to have an evidence-based approach when encountering signs or symptoms of confusion.

aICD-10 code R41.0 encompasses Confusion, Other Specified Delirium, or Unspecified Delirium.

CASE REPORT

Ms. T, age 62, has hypothyroidism and bipolar I disorder, most recently depressed, with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. She has been taking lithium, 600 mg/d, to control her mood symptoms. Her daughter-in-law reports that Ms. T has been exhibiting increasing signs of confusion. During the office evaluation, Ms. T minimizes her symptoms, only describing mild issues with forgetfulness while cooking and concern over increasing anxiety. Her daughter-in-law plays a voicemail message from earlier in the week, in which Ms. T’s speech is halting, disorganized, and in a word, confused. I decide to use the mnemonic decision chart MR. MIND (Table 1) to get to the bottom of her recent confusion.

Measure cognition

It is nice to receive advanced warning about a cognitive change or a change in activities of daily living; however, many patients present with subtle, sub-acute changes that are more difficult to assess. When encountering a broad symptom such as “confusion”—which has an equally broad differential diagnosis—systematic assessment of the current cognitive state compared with the patient’s baseline becomes the first order of business. However, this requires that the patient has had a baseline cognitive assessment.

In my practice, I often administer one of the validated neurocognitive screening instruments when a patient first begins care—even a brief test such as the Mini- Cog (3-item recall plus clock drawing test), which is comparable to longer screening tests at least for NCD/dementia.1 During a presentation for confusion, a more detailed neurocognitive assessment instrument would be recommended, allowing one to marry the clinical impression with a validated, objective measure. Formal neuropsychological testing by a clinical neuropsychologist is the gold standard, but such testing is time-consuming and expensive and often not readily available. The screening instrument I use for a more thorough evaluation depends on the clinical scenario.

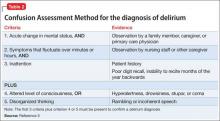

The Six-Item Screener is used in some emergency settings because it is short but boasts a higher sensitivity than the Mini- Cog (94% vs 75%) with similar specificity when screening for cognitive impairment.2 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a valuable instrument, although, recently, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination has been thought to be better at detecting mild NCD than the MMSE; more data are needed to substantiate this claim.3 The Montreal Cognitive Assessment is another validated screening tool that has been shown to be superior to the MMSE in terms of screening for mild cognitive impairment.4 The best delirium-specific assessment tool is the Confusion Assessment Method (Table 2).5

Ms. T’s MMSE score was 26/30, down from 29/30 at baseline. Her score fell below the cutoff score of 27 for mild cognitive impairment for someone with at least 8 years of completed education. Her results were abnormal mainly in the memory domain (3-item recall), raising the question of a possible prodromal state of AD although the acute nature of the change made delirium or mild NCD high in the differential.

Review medications

A review of the medication list is not just a Joint Commission mandate (medication reconciliation during each encounter) but is important whenever confusion is noted. Polypharmacy can be a concern, but is not as concerning as the class of medication prescribed, particularly anticholinergic and sedative medications in patients age >65. The Drug Burden Index can be helpful in assessing this risk.6 Medications such as the benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, tricyclic antidepressants, and antipsychotics should be discontinued if possible, keeping in mind that the addition or subtraction of medications must be done prudently and only after reviewing the evidence and in consultation with the patient. A detailed medication review is as important for confused outpatients as it is for an inpatient case (steps 2 and 3 of the inpatient algorithm outlined in Table 3).7

In Ms. T’s case, the primary concern on her medication list was that her medical team was prescribing levothyroxine, 112 mcg/d, and desiccated thyroid (combination thyroxine and triiodothyronine in the form of 20 mg Armour Thyroid), despite a lack of data for such combination therapy. Earlier, I had discontinued lorazepam, leaving lithium, 600 mg/d, quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d, as her remaining psychotropics. Her other medications included atorvastatin, 40 mg/d, for hyper-lipidemia and metformin, 750 mg/d, for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Medical illness

An organic basis must rank high in the differential diagnosis if medications are not the culprit. There are myriad medical disorders that can lead to confusion (Table 4).8 In an outpatient psychiatric setting, laboratory and radiology testing might not be readily available. It then becomes important to collaborate with a patient’s medical team if any of the following are met:

•there is high suspicion of a medical cause

•there could be delays in performing a medical workup

•a physical examination is needed.

Laboratory work-up should include:

•comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) to assess for electrolyte derangements and liver or kidney disease

•urinalysis if there are signs of urinary tract infection (low threshold for testing in patients age >65 even if they are asymptomatic)

•urine drug screen or serum alcohol level if substance use is suspected

•complete blood count (CBC) if there are reports of infection (white blood cell count) or blood loss/bruising to ensure that anemia or thrombocytopenia is not playing a role

•thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) because thyroid disorders can cause neuropsychiatric as well as somatic symptoms.9

Other laboratory testing could be valuable depending on the clinical scenario. These include tests such as:

•drug level monitoring (lithium, valproic acid, etc.) to assess for toxicity

•HIV and rapid plasma reagin for suspected sexually transmitted infections

•vitamin levels in patients with poor nutrition or post bariatric surgery

•erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, or both, if there are signs of inflammation

•bacterial culture if blood or tissue infection is a concern.

Esoteric tests include ceruloplasmin (Wilson’s disease), heavy metals screen, and even tests such as anti-gliadin antibodies because the prevalence of gluten sensitivity and celiac disease appear to be on the rise and have been associated with neuropsychiatric problems including encephalopathy.10

Brain imaging is an important consideration when a medical differential diagnosis for confusion is formulated. Unfortunately, there is little evidence-based guidance as to when brain imaging should be performed, often leading to overuse of tests such as CT, especially in emergency settings when confusion is noted. From a clinical standpoint, a head CT scan often is best ordered for patients who demonstrate an acute change in mental status, are age >70, are receiving anticoagulation, or have sustained trauma to the head. The key concern would be intracranial hemorrhage. However, some data suggest that the best use of head CT is for patients who have an impaired level of consciousness or a new focal neurologic deficit.11

Apart from more acute changes, a brain MRI study is more helpful than a head CT when evaluating the brain parenchyma for more sub-acute diagnoses such as multiple sclerosis or a brain tumor. T2-weighted hyperintensities seen on an MRI are thought to predict an increased risk of stroke, dementia, and death.

Their discovery should prompt a detailed evaluation for risk factors of stroke and dementia/NCD.12

In Ms. T’s case, she was taking lithium, so it was logical to obtain a trough lithium level 12 hours after the last dose and to check kidney function (serum creatinine to estimate the glomerular filtration rate), which were in the therapeutic/normal range. Her serum lithium level was 0.7 mEq/L. Brain imaging was not ordered, but several other labs (CMP, CBC, hemoglobin A1c [HgbA1c], and TSH) were drawn. These labs were notable for HgbA1c of 5.1% (normal <5.7%) and TSH of 0.5 mIU/L (normal level, 1.5 mIU/L), which is low for someone taking thyroid replacement.

I requested that Ms. T stop Armour Thyroid to address the suppressed TSH. I also requested that she stop metformin because, although hypoglycemia from metformin monotherapy is uncommon, it can happen in older patients. Hypoglycemia associated with metformin also can occur in situations when caloric intake is deficient or when metformin is used in combination with other drugs such as sulfonylureas (ie, glipizide), beta-adrenergic blocking drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or even nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.13

Identifying overlapping psychiatric (or psychological) illness

Symptoms of depression, anxiety, psychosis, and even dissociation can present as confusion. The term pseudodementia describes patients who exhibit cognitive symptoms consistent with NCD but could improve once the underlying mood, thought, anxiety, or personality disorder is treated.

For example, a patient with depression typically exhibits neurovegetative symptoms—such as poor sleep or appetite— amotivation, and low energy. All of these can lead to abrupt-onset cognitive changes, which are a hallmark of pseudodementia rather than the more insidious pattern of mild NCD. In cases of pseudodementia, neurocognitive testing will show impairment that often rapidly improves after the primary psychiatric (or psychological) issue is rectified. Making a diagnosis of pseudodementia at the initial presentation is difficult because neurocognitive tests such as the MMSE often fail to separate depression from true cognitive changes.14 Such a diagnosis typically requires hindsight. Yet, one must also keep in mind that pseudodementia may be part of a NCD prodrome.15

Conversion disorder as well as the dissociative disorders and substance-related disorders are notorious for causing confusion. In Ms. T’s case, pseudodementia stemming from her underlying bipolar disorder and anxiety figured prominently in the differential diagnosis, but she did not have any other overt psychopathology, personality disorder, or signs of malingering to further complicate her picture.

Notebook. I recommend that my patients keep a small notebook to record medical data ranging from blood pressure and glycemic measurements to details about sleep and dietary intake. Such data comprise the necessary metrics to properly assess target conditions and then track changes once treatment is initiated. This exercise not only yields much-needed detail about the patient’s condition for the clinician; the act of journaling also can be therapeutic for the writer through a process known as experimental disclosure, in which writing down one’s thoughts and observations has a positive impact on the writer’s physical health and psychology.16