User login

DSM-5 defines personality disorders (PDs) as the presence of an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that “deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment.”1 As a general rule, PDs are not limited to episodes of illness, but reflect an individual’s long-term adjustment. These disorders occur in 10% to 15% of the general population; the rates are especially high in health care settings, in criminal offenders, and in those with a substance use disorder (SUD).2 PDs nearly always have an onset in adolescence or early adulthood and tend to diminish in severity with advancing age. They are associated with high rates of unemployment, homelessness, divorce and separation, domestic violence, substance misuse, and suicide.3

Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for PDs, but there has been growing interest in using pharmacotherapy to treat PDs. While much of the PD treatment literature focuses on borderline PD,4-9 this article describes diagnosis, potential pharmacotherapy strategies, and methods to assess response to treatment for patients with all types of PDs.

Recognizing and diagnosing personality disorders

The diagnosis of a PD requires an understanding of DSM-5 criteria combined with a comprehensive psychiatric history and mental status examination. The patient’s history is the most important basis for diagnosing a PD.2 Collateral information from relatives or friends can help confirm the severity and pervasiveness of the individual’s personality problems. In some patients, long-term observation might be necessary to confirm the presence of a PD. Some clinicians are reluctant to diagnose PDs because of stigma, a problem common among patients with borderline PD.10,11

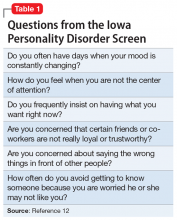

To screen for PDs, a clinician might ask the patient about problems with interpersonal relationships, sense of self, work, affect, impulse control, and reality testing. Table 112 lists general screening questions for the presence of a PD from the Iowa Personality Disorders Screen. Structured diagnostic interviews and self-report assessments could boost recognition of PDs, but these tools are rarely used outside of research settings.13,14

The PD clusters

DSM-5 divides 10 PDs into 3 clusters based on shared phenomenology and diagnostic criteria. Few patients have a “pure” case in which they meet criteria for only a single personality disorder.1

Cluster A. “Eccentric cluster” disorders are united by social aversion, a failure to form close attachments, or paranoia and suspiciousness.15 These include paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PD. Low self-awareness is typical. There are no treatment guidelines for these disorders, although there is some clinical trial data for schizotypal PD.

Cluster B. “Dramatic cluster” disorders share dramatic, emotional, and erratic characteristics.14 These include narcissistic, antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PD. Antisocial and narcissistic patients have low self-awareness. There are treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, and a variety of clinical trial data is available for the latter.15

Continue to: Cluster C

Cluster C. “Anxious cluster” disorders are united by anxiousness, fearfulness, and poor self-esteem. Many of these patients also display interpersonal rigidity.15 These disorders include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive PD. There are no treatment guidelines or clinical trial data for these disorders.

Why consider pharmacotherapy for personality disorders?

The consensus among experts is that psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for PDs.15 Despite significant gaps in the evidence base, there has been a growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. For example, research shows that >90% of patients with borderline PD are prescribed medication, most typically antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, stimulants, or sedative-hypnotics.16,17

Increased interest in pharmacotherapy for PDs could be related to research showing the importance of underlying neurobiology, particularly for antisocial and borderline PD.18,19 This work is complemented by genetic research showing the heritability of PD traits and disorders.20,21 Another factor could be renewed interest in dimensional approaches to the classification of PDs, as exemplified by DSM-5’s alternative model for PDs.1 This approach aligns with some expert recommendations to focus on treating PD symptom dimensions, rather than the syndrome itself.22

Importantly, no psychotropic medication is FDA-approved for the treatment of any PD. For that reason, prescribing medication for a PD is “off-label,” although prescribing a medication for a comorbid disorder for which the drug has an FDA-approved indication is not (eg, prescribing an antidepressant for major depressive disorder [MDD]).

Principles for prescribing

Despite gaps in research data, general principles for using medication to treat PDs have emerged from treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, clinical trial data, reviews and meta-analyses, and expert opinion. Clinicians should address the following considerations before prescribing medication to a patient with a PD.

Continue to: PD diagnosis

PD diagnosis. Has the patient been properly assessed and diagnosed? While history is the most important basis for diagnosis, the clinician should be familiar with the PDs and DSM-5 criteria. Has the patient been informed of the diagnosis and its implications for treatment?

Patient interest in medication. Is the patient interested in taking medication? Patients with borderline PD are often prescribed medication, but there are sparse data for the other PDs. The patient might have little interest in the PD diagnosis or its treatment.

Comorbidity. Has the patient been assessed for comorbid psychiatric disorders that could interfere with medication use (ie, an SUD) or might be a focus of treatment (eg, MDD)? Patients with PDs typically have significant comorbidity that a thorough evaluation will uncover.

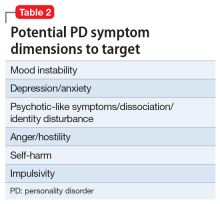

PD symptom dimensions. Has the patient been assessed to determine cognitive or behavioral symptom dimensions of their PD? One or more symptom dimension(s) could be the focus of treatment. Table 2 lists examples of PD symptom dimensions.

Strategies to guide prescribing

Strategies to help guide prescribing include targeting any comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions (eg, impulsive aggression), choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself.

Continue to: Targeting comorbid disorders

Targeting comorbid disorders. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD recommend that clinicians focus on treating comorbid disorders, a position echoed in Cochrane and other reviews.4,9,22-26 For example, a patient with borderline PD experiencing a major depressive episode could be treated with an antidepressant. Targeting the depressive symptoms could boost the patient’s mood, perhaps lessening the individual’s PD symptoms or reducing their severity.

Targeting important symptom dimensions. For patients with borderline PD, several guidelines and reviews have suggested that treatment should focus on emotional dysregulation and impulsive aggression (mood stabilizers, antipsychotics), or cognitive-perceptual symptoms (antipsychotics).4-6,15 There is some evidence that mood stabilizers or second-generation antipsychotics could help reduce impulsive aggression in patients with antisocial PD.27

Choosing medication based on similarity to another disorder known to respond to medication. Avoidant PD overlaps with social anxiety disorder and can be conceptualized as a chronic, pervasive social phobia. Avoidant PD might respond to a medication known to be effective for treating social anxiety disorder, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or venlafaxine.28 Treating obsessive-compulsive PD with an SSRI is another example of this strategy, as 1 small study of fluvoxamine suggests.29 Obsessive-compulsive PD is common in persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and overlap includes preoccupation with orders, rules, and lists, and an inability to throw things out.

Targeting the PD syndrome. Another strategy is to target the PD itself. Clinical trial data suggest the antipsychotic risperidone can reduce the symptoms of schizotypal PD.30 Considering that this PD has a genetic association with schizophrenia, it is not surprising that the patient’s ideas of reference, odd communication, or transient paranoia might respond to an antipsychotic. Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the use of the second-generation antipsychotics aripiprazole and quetiapine to treat BPD.31,32 While older guidelines4,5 supported the use of the mood stabilizer lamotrigine, a recent RCT found that it was no more effective than placebo for borderline PD or its symptom dimensions.33

What to do before prescribing

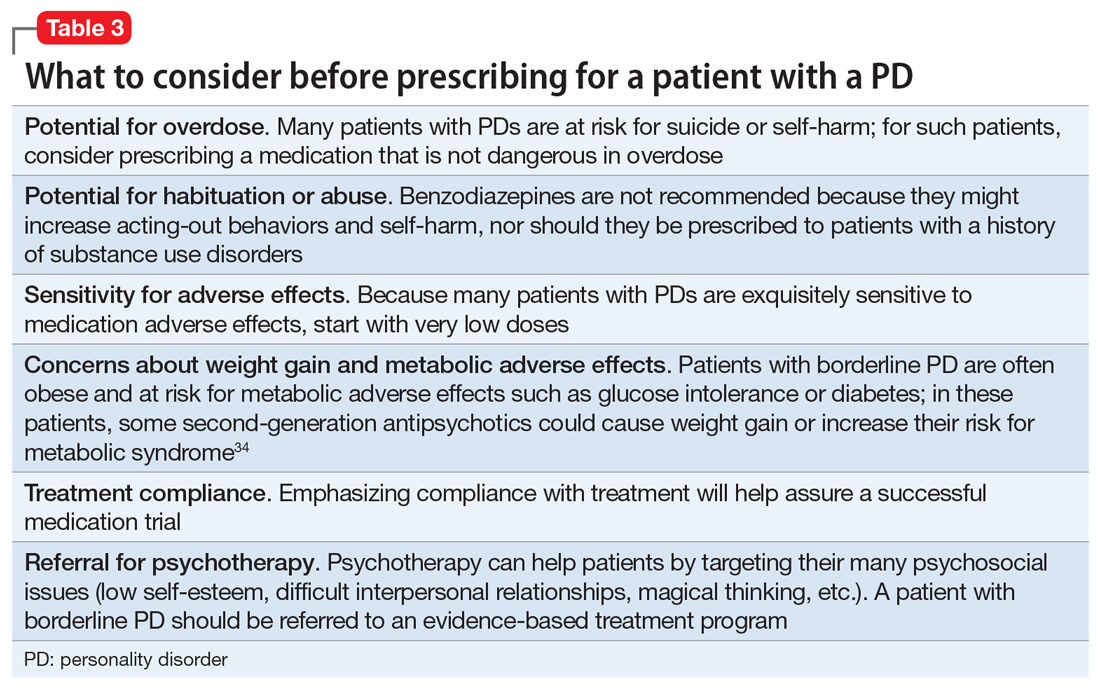

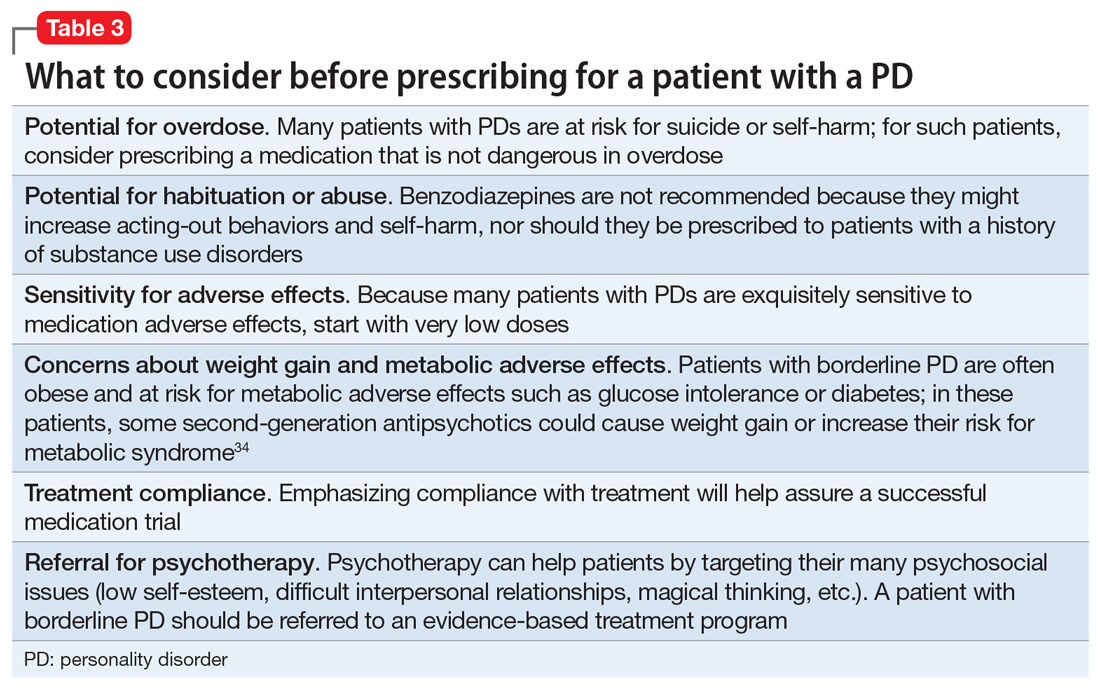

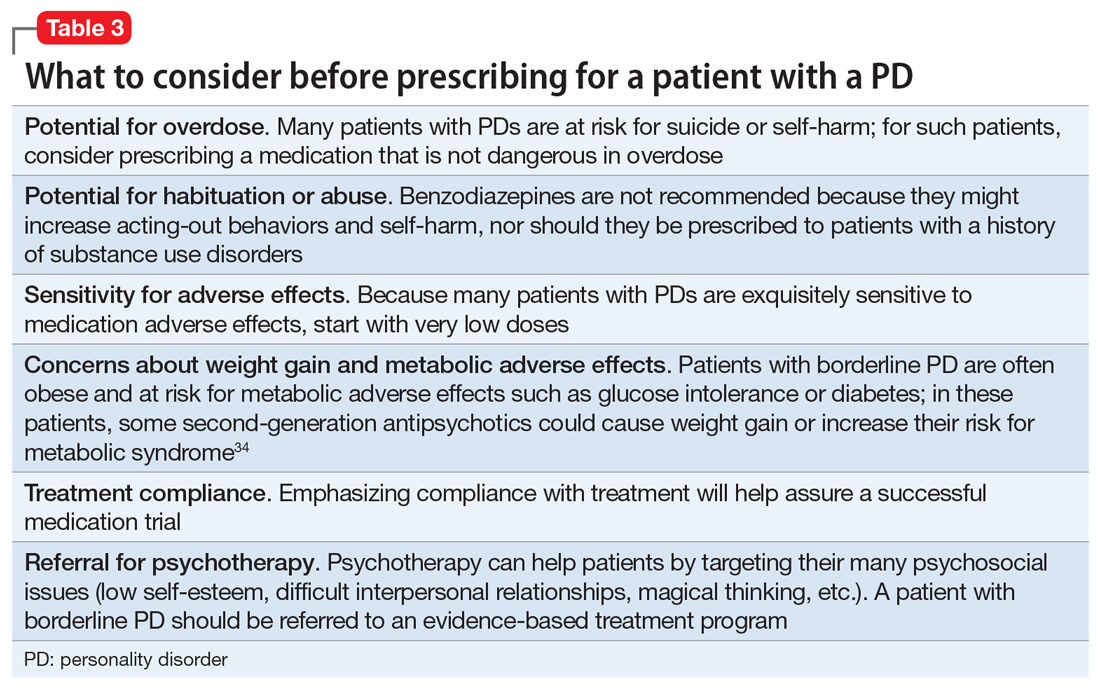

Before writing a prescription, the clinician and patient should discuss the presence of a PD and the desirability of treatment. The patient should understand the limited evidence base and know that medication prescribed for a PD is off-label. The clinician should discuss medication selection and its rationale, and whether the medication is targeting a comorbid disorder, symptom dimension(s), or the PD itself. Additional considerations for prescribing for patients with PDs are listed in Table 3.34

Continue to: Avoid polypharmacy

Avoid polypharmacy. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed multiple psychotropic medications.16,17 This approach leads to greater expense and more adverse effects, and is not evidence-based.

Avoid benzodiazepines. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed benzodiazepines, often as part of a polypharmacy regimen. These drugs can cause disinhibition, thereby increasing acting-out behaviors and self-harm.35 Also, patients with PDs often have SUDs, which is a contraindication for benzodiazepine use.

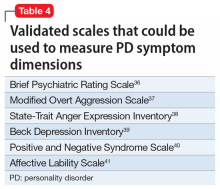

Rate the patient’s improvement. Both the patient and clinician can benefit from monitoring symptomatic improvement. Several validated scales can be used to rate depression, anxiety, impulsivity, mood lability, anger, and aggression (Table 436-41).Some validated scales for borderline PD align with DSM-5 criteria. Two such widely used instruments are the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD)42 and the self-rated Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST).43 Each has questions that could be pulled to rate a symptom dimension of interest, such as affective instability, anger dyscontrol, or abandonment fears (Table 542,43).

A visual analog scale is easy to use and can target symptom dimensions of interest.44 For example, a clinician could use a visual analog scale to rate mood instability by asking a patient to rate their mood severity by making a mark along a 10-cm line (0 = “Most erratic emotions I have experienced,” 10 = “Most stable I have ever experienced my emotions to be”). This score can be recorded at baseline and subsequent visits.

Take-home points

PDs are common in the general population and health care settings. They are underrecognized by the general public and mental health professionals, often because of stigma. Clinicians could boost their recognition of these disorders by embedding simple screening questions in their patient assessments. Many patients with PDs will be interested in pharmacotherapy for their disorder or symptoms. Treatment strategies include targeting the comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions, choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself. Each strategy has its limitations and varying degrees of empirical support. Treatment response can be monitored using validated scales or a visual analog scale.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although psychotherapy is the first-line treatment and no medications are FDAapproved for treating personality disorders (PDs), there has been growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. Strategies for pharmacotherapy include targeting comorbid disorders, PD symptom dimensions, or the PD itself. Choice of medication can be based on the similarity of the PD with another disorder known to respond to medication.

Related Resources

- Correa Da Costa S, Sanches M, Soares JC. Bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):26-29,35-39.

- Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Black DW, Andreasen N. Personality disorders. In: Black DW, Andreasen N. Introductory textbook of psychiatry, 7th edition. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2020:410-423.

3. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord 2004;18(3):226-239.

4. Lieb K, Völlm B, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):4-12.

5. Vita A, De Peri L, Sacchetti E. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and placebo on the symptom dimensions of borderline personality disorder – a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and open-label trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):613-624.

6. Stoffers JM, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder – current evidence and recent trends. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):534.

7. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):345-356.

8. Black DW, Paris J, Schulz SC. Personality disorders: evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M, ed. Cognitive behavioral psychopharmacology: the clinical practice of evidence-based biopsychosocial integration. John Wiley & Sons; 2018:137-165.

9. Stoffers-Winterling J, Sorebø OJ, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: an update of published, unpublished and ongoing studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):37.

10. Lewis G, Appleby L. Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:44-49.

11. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(3):67-74.

12. Langbehn DR, Pfohl BM, Reynolds S, et al. The Iowa Personality Disorder Screen: development and preliminary validation of a brief screening interview. J Pers Disord. 1999;13(1):75-89.

13. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV). American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Part II: multisite test-retest reliability study. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(2):92-104.

15. Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

16. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Treatment rates for patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality disorders: a 16-year study. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):15-20.

17. Black DW, Allen J, McCormick B, et al. Treatment received by persons with BPD participating in a randomized clinical trial of the Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving programme. Person Ment Health. 2011;5(3):159-168.

18. Yang Y, Glenn AL, Raine A. Brain abnormalities in antisocial individuals: implications for the law. Behav Sci Law. 2008;26(1):65-83.

19. Ruocco AC, Amirthavasagam S, Choi-Kain LW, et al. Neural correlates of negative emotionality in BPD: an activation-likelihood-estimation meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(2):153-160.

20. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831.

21. Slutske WS. The genetics of antisocial behavior. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3(2):158-162.

22. Ripoll LH, Triebwasser J, Siever LJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(9):1257-1288.

23. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management. Clinical guideline [CG78]. Published January 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antisocial personality disorder: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG77]. Published January 2009. Updated March 27, 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg77

25. Khalifa N, Duggan C, Stoffers J, et al. Pharmacologic interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rep. 2010;(8):CD007667.

26. Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(8):CD005652.

27. Black DW. The treatment of antisocial personality disorder. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-017-0123-z

28. Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, et al. Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(8):708-713.

29. Ansseau M. The obsessive-compulsive personality: diagnostic aspects and treatment possibilities. In: Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, eds. Focus on obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Syn-Thesis; 1997:61-73.

30. Koenigsberg HW, Reynolds D, Goodman M, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of schizotypal personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):628-634.

31. Black DW, Zanarini MC, Romine A, et al. Comparison of low and moderate dosages of extended-release quetiapine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(11):1174-1182.

32. Nickel MK, Muelbacher M, Nickel C, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):833-838.

33. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764.

34. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(12)1660-1665.

35. Cowdry RW, Gardner DL. Pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder. Alprazolam, carbamazepine, trifluoperazine, and tranylcypromine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(2):111-119.

36. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799-812.

37. Ratey JJ, Gutheil CM. The measurement of aggressive behavior: reflections on the use of the Overt Aggression Scale and the Modified Overt Aggression Scale. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 1991;3(2):S57-S60.

38. Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, et al. Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). In: Maruish ME, ed. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999:993-1021.

39. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory II. Psychological Corp; 1996.

40. Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form. The University of Iowa; 1999.

41. Harvey D, Greenberg BR, Serper MR, et al. The affective lability scales: development, reliability, and validity. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45(5):786-793.

42. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): a continuous measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology. J Person Disord. 2003:17(3):233-242.

43. Pfohl B, Blum N, St John D, et al. Reliability and validity of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST): a new scale to measure severity and change in borderline personality disorder. J Person Disord. 2009;23(3):281-293.

44. Ahearn EP. The use of visual analog scales in mood disorders: a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31(5):569-579.

DSM-5 defines personality disorders (PDs) as the presence of an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that “deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment.”1 As a general rule, PDs are not limited to episodes of illness, but reflect an individual’s long-term adjustment. These disorders occur in 10% to 15% of the general population; the rates are especially high in health care settings, in criminal offenders, and in those with a substance use disorder (SUD).2 PDs nearly always have an onset in adolescence or early adulthood and tend to diminish in severity with advancing age. They are associated with high rates of unemployment, homelessness, divorce and separation, domestic violence, substance misuse, and suicide.3

Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for PDs, but there has been growing interest in using pharmacotherapy to treat PDs. While much of the PD treatment literature focuses on borderline PD,4-9 this article describes diagnosis, potential pharmacotherapy strategies, and methods to assess response to treatment for patients with all types of PDs.

Recognizing and diagnosing personality disorders

The diagnosis of a PD requires an understanding of DSM-5 criteria combined with a comprehensive psychiatric history and mental status examination. The patient’s history is the most important basis for diagnosing a PD.2 Collateral information from relatives or friends can help confirm the severity and pervasiveness of the individual’s personality problems. In some patients, long-term observation might be necessary to confirm the presence of a PD. Some clinicians are reluctant to diagnose PDs because of stigma, a problem common among patients with borderline PD.10,11

To screen for PDs, a clinician might ask the patient about problems with interpersonal relationships, sense of self, work, affect, impulse control, and reality testing. Table 112 lists general screening questions for the presence of a PD from the Iowa Personality Disorders Screen. Structured diagnostic interviews and self-report assessments could boost recognition of PDs, but these tools are rarely used outside of research settings.13,14

The PD clusters

DSM-5 divides 10 PDs into 3 clusters based on shared phenomenology and diagnostic criteria. Few patients have a “pure” case in which they meet criteria for only a single personality disorder.1

Cluster A. “Eccentric cluster” disorders are united by social aversion, a failure to form close attachments, or paranoia and suspiciousness.15 These include paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PD. Low self-awareness is typical. There are no treatment guidelines for these disorders, although there is some clinical trial data for schizotypal PD.

Cluster B. “Dramatic cluster” disorders share dramatic, emotional, and erratic characteristics.14 These include narcissistic, antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PD. Antisocial and narcissistic patients have low self-awareness. There are treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, and a variety of clinical trial data is available for the latter.15

Continue to: Cluster C

Cluster C. “Anxious cluster” disorders are united by anxiousness, fearfulness, and poor self-esteem. Many of these patients also display interpersonal rigidity.15 These disorders include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive PD. There are no treatment guidelines or clinical trial data for these disorders.

Why consider pharmacotherapy for personality disorders?

The consensus among experts is that psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for PDs.15 Despite significant gaps in the evidence base, there has been a growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. For example, research shows that >90% of patients with borderline PD are prescribed medication, most typically antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, stimulants, or sedative-hypnotics.16,17

Increased interest in pharmacotherapy for PDs could be related to research showing the importance of underlying neurobiology, particularly for antisocial and borderline PD.18,19 This work is complemented by genetic research showing the heritability of PD traits and disorders.20,21 Another factor could be renewed interest in dimensional approaches to the classification of PDs, as exemplified by DSM-5’s alternative model for PDs.1 This approach aligns with some expert recommendations to focus on treating PD symptom dimensions, rather than the syndrome itself.22

Importantly, no psychotropic medication is FDA-approved for the treatment of any PD. For that reason, prescribing medication for a PD is “off-label,” although prescribing a medication for a comorbid disorder for which the drug has an FDA-approved indication is not (eg, prescribing an antidepressant for major depressive disorder [MDD]).

Principles for prescribing

Despite gaps in research data, general principles for using medication to treat PDs have emerged from treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, clinical trial data, reviews and meta-analyses, and expert opinion. Clinicians should address the following considerations before prescribing medication to a patient with a PD.

Continue to: PD diagnosis

PD diagnosis. Has the patient been properly assessed and diagnosed? While history is the most important basis for diagnosis, the clinician should be familiar with the PDs and DSM-5 criteria. Has the patient been informed of the diagnosis and its implications for treatment?

Patient interest in medication. Is the patient interested in taking medication? Patients with borderline PD are often prescribed medication, but there are sparse data for the other PDs. The patient might have little interest in the PD diagnosis or its treatment.

Comorbidity. Has the patient been assessed for comorbid psychiatric disorders that could interfere with medication use (ie, an SUD) or might be a focus of treatment (eg, MDD)? Patients with PDs typically have significant comorbidity that a thorough evaluation will uncover.

PD symptom dimensions. Has the patient been assessed to determine cognitive or behavioral symptom dimensions of their PD? One or more symptom dimension(s) could be the focus of treatment. Table 2 lists examples of PD symptom dimensions.

Strategies to guide prescribing

Strategies to help guide prescribing include targeting any comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions (eg, impulsive aggression), choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself.

Continue to: Targeting comorbid disorders

Targeting comorbid disorders. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD recommend that clinicians focus on treating comorbid disorders, a position echoed in Cochrane and other reviews.4,9,22-26 For example, a patient with borderline PD experiencing a major depressive episode could be treated with an antidepressant. Targeting the depressive symptoms could boost the patient’s mood, perhaps lessening the individual’s PD symptoms or reducing their severity.

Targeting important symptom dimensions. For patients with borderline PD, several guidelines and reviews have suggested that treatment should focus on emotional dysregulation and impulsive aggression (mood stabilizers, antipsychotics), or cognitive-perceptual symptoms (antipsychotics).4-6,15 There is some evidence that mood stabilizers or second-generation antipsychotics could help reduce impulsive aggression in patients with antisocial PD.27

Choosing medication based on similarity to another disorder known to respond to medication. Avoidant PD overlaps with social anxiety disorder and can be conceptualized as a chronic, pervasive social phobia. Avoidant PD might respond to a medication known to be effective for treating social anxiety disorder, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or venlafaxine.28 Treating obsessive-compulsive PD with an SSRI is another example of this strategy, as 1 small study of fluvoxamine suggests.29 Obsessive-compulsive PD is common in persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and overlap includes preoccupation with orders, rules, and lists, and an inability to throw things out.

Targeting the PD syndrome. Another strategy is to target the PD itself. Clinical trial data suggest the antipsychotic risperidone can reduce the symptoms of schizotypal PD.30 Considering that this PD has a genetic association with schizophrenia, it is not surprising that the patient’s ideas of reference, odd communication, or transient paranoia might respond to an antipsychotic. Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the use of the second-generation antipsychotics aripiprazole and quetiapine to treat BPD.31,32 While older guidelines4,5 supported the use of the mood stabilizer lamotrigine, a recent RCT found that it was no more effective than placebo for borderline PD or its symptom dimensions.33

What to do before prescribing

Before writing a prescription, the clinician and patient should discuss the presence of a PD and the desirability of treatment. The patient should understand the limited evidence base and know that medication prescribed for a PD is off-label. The clinician should discuss medication selection and its rationale, and whether the medication is targeting a comorbid disorder, symptom dimension(s), or the PD itself. Additional considerations for prescribing for patients with PDs are listed in Table 3.34

Continue to: Avoid polypharmacy

Avoid polypharmacy. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed multiple psychotropic medications.16,17 This approach leads to greater expense and more adverse effects, and is not evidence-based.

Avoid benzodiazepines. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed benzodiazepines, often as part of a polypharmacy regimen. These drugs can cause disinhibition, thereby increasing acting-out behaviors and self-harm.35 Also, patients with PDs often have SUDs, which is a contraindication for benzodiazepine use.

Rate the patient’s improvement. Both the patient and clinician can benefit from monitoring symptomatic improvement. Several validated scales can be used to rate depression, anxiety, impulsivity, mood lability, anger, and aggression (Table 436-41).Some validated scales for borderline PD align with DSM-5 criteria. Two such widely used instruments are the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD)42 and the self-rated Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST).43 Each has questions that could be pulled to rate a symptom dimension of interest, such as affective instability, anger dyscontrol, or abandonment fears (Table 542,43).

A visual analog scale is easy to use and can target symptom dimensions of interest.44 For example, a clinician could use a visual analog scale to rate mood instability by asking a patient to rate their mood severity by making a mark along a 10-cm line (0 = “Most erratic emotions I have experienced,” 10 = “Most stable I have ever experienced my emotions to be”). This score can be recorded at baseline and subsequent visits.

Take-home points

PDs are common in the general population and health care settings. They are underrecognized by the general public and mental health professionals, often because of stigma. Clinicians could boost their recognition of these disorders by embedding simple screening questions in their patient assessments. Many patients with PDs will be interested in pharmacotherapy for their disorder or symptoms. Treatment strategies include targeting the comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions, choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself. Each strategy has its limitations and varying degrees of empirical support. Treatment response can be monitored using validated scales or a visual analog scale.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although psychotherapy is the first-line treatment and no medications are FDAapproved for treating personality disorders (PDs), there has been growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. Strategies for pharmacotherapy include targeting comorbid disorders, PD symptom dimensions, or the PD itself. Choice of medication can be based on the similarity of the PD with another disorder known to respond to medication.

Related Resources

- Correa Da Costa S, Sanches M, Soares JC. Bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):26-29,35-39.

- Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Venlafaxine • Effexor

DSM-5 defines personality disorders (PDs) as the presence of an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that “deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment.”1 As a general rule, PDs are not limited to episodes of illness, but reflect an individual’s long-term adjustment. These disorders occur in 10% to 15% of the general population; the rates are especially high in health care settings, in criminal offenders, and in those with a substance use disorder (SUD).2 PDs nearly always have an onset in adolescence or early adulthood and tend to diminish in severity with advancing age. They are associated with high rates of unemployment, homelessness, divorce and separation, domestic violence, substance misuse, and suicide.3

Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for PDs, but there has been growing interest in using pharmacotherapy to treat PDs. While much of the PD treatment literature focuses on borderline PD,4-9 this article describes diagnosis, potential pharmacotherapy strategies, and methods to assess response to treatment for patients with all types of PDs.

Recognizing and diagnosing personality disorders

The diagnosis of a PD requires an understanding of DSM-5 criteria combined with a comprehensive psychiatric history and mental status examination. The patient’s history is the most important basis for diagnosing a PD.2 Collateral information from relatives or friends can help confirm the severity and pervasiveness of the individual’s personality problems. In some patients, long-term observation might be necessary to confirm the presence of a PD. Some clinicians are reluctant to diagnose PDs because of stigma, a problem common among patients with borderline PD.10,11

To screen for PDs, a clinician might ask the patient about problems with interpersonal relationships, sense of self, work, affect, impulse control, and reality testing. Table 112 lists general screening questions for the presence of a PD from the Iowa Personality Disorders Screen. Structured diagnostic interviews and self-report assessments could boost recognition of PDs, but these tools are rarely used outside of research settings.13,14

The PD clusters

DSM-5 divides 10 PDs into 3 clusters based on shared phenomenology and diagnostic criteria. Few patients have a “pure” case in which they meet criteria for only a single personality disorder.1

Cluster A. “Eccentric cluster” disorders are united by social aversion, a failure to form close attachments, or paranoia and suspiciousness.15 These include paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PD. Low self-awareness is typical. There are no treatment guidelines for these disorders, although there is some clinical trial data for schizotypal PD.

Cluster B. “Dramatic cluster” disorders share dramatic, emotional, and erratic characteristics.14 These include narcissistic, antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PD. Antisocial and narcissistic patients have low self-awareness. There are treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, and a variety of clinical trial data is available for the latter.15

Continue to: Cluster C

Cluster C. “Anxious cluster” disorders are united by anxiousness, fearfulness, and poor self-esteem. Many of these patients also display interpersonal rigidity.15 These disorders include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive PD. There are no treatment guidelines or clinical trial data for these disorders.

Why consider pharmacotherapy for personality disorders?

The consensus among experts is that psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for PDs.15 Despite significant gaps in the evidence base, there has been a growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. For example, research shows that >90% of patients with borderline PD are prescribed medication, most typically antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, stimulants, or sedative-hypnotics.16,17

Increased interest in pharmacotherapy for PDs could be related to research showing the importance of underlying neurobiology, particularly for antisocial and borderline PD.18,19 This work is complemented by genetic research showing the heritability of PD traits and disorders.20,21 Another factor could be renewed interest in dimensional approaches to the classification of PDs, as exemplified by DSM-5’s alternative model for PDs.1 This approach aligns with some expert recommendations to focus on treating PD symptom dimensions, rather than the syndrome itself.22

Importantly, no psychotropic medication is FDA-approved for the treatment of any PD. For that reason, prescribing medication for a PD is “off-label,” although prescribing a medication for a comorbid disorder for which the drug has an FDA-approved indication is not (eg, prescribing an antidepressant for major depressive disorder [MDD]).

Principles for prescribing

Despite gaps in research data, general principles for using medication to treat PDs have emerged from treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, clinical trial data, reviews and meta-analyses, and expert opinion. Clinicians should address the following considerations before prescribing medication to a patient with a PD.

Continue to: PD diagnosis

PD diagnosis. Has the patient been properly assessed and diagnosed? While history is the most important basis for diagnosis, the clinician should be familiar with the PDs and DSM-5 criteria. Has the patient been informed of the diagnosis and its implications for treatment?

Patient interest in medication. Is the patient interested in taking medication? Patients with borderline PD are often prescribed medication, but there are sparse data for the other PDs. The patient might have little interest in the PD diagnosis or its treatment.

Comorbidity. Has the patient been assessed for comorbid psychiatric disorders that could interfere with medication use (ie, an SUD) or might be a focus of treatment (eg, MDD)? Patients with PDs typically have significant comorbidity that a thorough evaluation will uncover.

PD symptom dimensions. Has the patient been assessed to determine cognitive or behavioral symptom dimensions of their PD? One or more symptom dimension(s) could be the focus of treatment. Table 2 lists examples of PD symptom dimensions.

Strategies to guide prescribing

Strategies to help guide prescribing include targeting any comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions (eg, impulsive aggression), choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself.

Continue to: Targeting comorbid disorders

Targeting comorbid disorders. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD recommend that clinicians focus on treating comorbid disorders, a position echoed in Cochrane and other reviews.4,9,22-26 For example, a patient with borderline PD experiencing a major depressive episode could be treated with an antidepressant. Targeting the depressive symptoms could boost the patient’s mood, perhaps lessening the individual’s PD symptoms or reducing their severity.

Targeting important symptom dimensions. For patients with borderline PD, several guidelines and reviews have suggested that treatment should focus on emotional dysregulation and impulsive aggression (mood stabilizers, antipsychotics), or cognitive-perceptual symptoms (antipsychotics).4-6,15 There is some evidence that mood stabilizers or second-generation antipsychotics could help reduce impulsive aggression in patients with antisocial PD.27

Choosing medication based on similarity to another disorder known to respond to medication. Avoidant PD overlaps with social anxiety disorder and can be conceptualized as a chronic, pervasive social phobia. Avoidant PD might respond to a medication known to be effective for treating social anxiety disorder, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or venlafaxine.28 Treating obsessive-compulsive PD with an SSRI is another example of this strategy, as 1 small study of fluvoxamine suggests.29 Obsessive-compulsive PD is common in persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and overlap includes preoccupation with orders, rules, and lists, and an inability to throw things out.

Targeting the PD syndrome. Another strategy is to target the PD itself. Clinical trial data suggest the antipsychotic risperidone can reduce the symptoms of schizotypal PD.30 Considering that this PD has a genetic association with schizophrenia, it is not surprising that the patient’s ideas of reference, odd communication, or transient paranoia might respond to an antipsychotic. Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the use of the second-generation antipsychotics aripiprazole and quetiapine to treat BPD.31,32 While older guidelines4,5 supported the use of the mood stabilizer lamotrigine, a recent RCT found that it was no more effective than placebo for borderline PD or its symptom dimensions.33

What to do before prescribing

Before writing a prescription, the clinician and patient should discuss the presence of a PD and the desirability of treatment. The patient should understand the limited evidence base and know that medication prescribed for a PD is off-label. The clinician should discuss medication selection and its rationale, and whether the medication is targeting a comorbid disorder, symptom dimension(s), or the PD itself. Additional considerations for prescribing for patients with PDs are listed in Table 3.34

Continue to: Avoid polypharmacy

Avoid polypharmacy. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed multiple psychotropic medications.16,17 This approach leads to greater expense and more adverse effects, and is not evidence-based.

Avoid benzodiazepines. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed benzodiazepines, often as part of a polypharmacy regimen. These drugs can cause disinhibition, thereby increasing acting-out behaviors and self-harm.35 Also, patients with PDs often have SUDs, which is a contraindication for benzodiazepine use.

Rate the patient’s improvement. Both the patient and clinician can benefit from monitoring symptomatic improvement. Several validated scales can be used to rate depression, anxiety, impulsivity, mood lability, anger, and aggression (Table 436-41).Some validated scales for borderline PD align with DSM-5 criteria. Two such widely used instruments are the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD)42 and the self-rated Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST).43 Each has questions that could be pulled to rate a symptom dimension of interest, such as affective instability, anger dyscontrol, or abandonment fears (Table 542,43).

A visual analog scale is easy to use and can target symptom dimensions of interest.44 For example, a clinician could use a visual analog scale to rate mood instability by asking a patient to rate their mood severity by making a mark along a 10-cm line (0 = “Most erratic emotions I have experienced,” 10 = “Most stable I have ever experienced my emotions to be”). This score can be recorded at baseline and subsequent visits.

Take-home points

PDs are common in the general population and health care settings. They are underrecognized by the general public and mental health professionals, often because of stigma. Clinicians could boost their recognition of these disorders by embedding simple screening questions in their patient assessments. Many patients with PDs will be interested in pharmacotherapy for their disorder or symptoms. Treatment strategies include targeting the comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions, choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself. Each strategy has its limitations and varying degrees of empirical support. Treatment response can be monitored using validated scales or a visual analog scale.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although psychotherapy is the first-line treatment and no medications are FDAapproved for treating personality disorders (PDs), there has been growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. Strategies for pharmacotherapy include targeting comorbid disorders, PD symptom dimensions, or the PD itself. Choice of medication can be based on the similarity of the PD with another disorder known to respond to medication.

Related Resources

- Correa Da Costa S, Sanches M, Soares JC. Bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):26-29,35-39.

- Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Black DW, Andreasen N. Personality disorders. In: Black DW, Andreasen N. Introductory textbook of psychiatry, 7th edition. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2020:410-423.

3. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord 2004;18(3):226-239.

4. Lieb K, Völlm B, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):4-12.

5. Vita A, De Peri L, Sacchetti E. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and placebo on the symptom dimensions of borderline personality disorder – a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and open-label trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):613-624.

6. Stoffers JM, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder – current evidence and recent trends. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):534.

7. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):345-356.

8. Black DW, Paris J, Schulz SC. Personality disorders: evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M, ed. Cognitive behavioral psychopharmacology: the clinical practice of evidence-based biopsychosocial integration. John Wiley & Sons; 2018:137-165.

9. Stoffers-Winterling J, Sorebø OJ, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: an update of published, unpublished and ongoing studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):37.

10. Lewis G, Appleby L. Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:44-49.

11. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(3):67-74.

12. Langbehn DR, Pfohl BM, Reynolds S, et al. The Iowa Personality Disorder Screen: development and preliminary validation of a brief screening interview. J Pers Disord. 1999;13(1):75-89.

13. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV). American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Part II: multisite test-retest reliability study. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(2):92-104.

15. Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

16. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Treatment rates for patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality disorders: a 16-year study. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):15-20.

17. Black DW, Allen J, McCormick B, et al. Treatment received by persons with BPD participating in a randomized clinical trial of the Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving programme. Person Ment Health. 2011;5(3):159-168.

18. Yang Y, Glenn AL, Raine A. Brain abnormalities in antisocial individuals: implications for the law. Behav Sci Law. 2008;26(1):65-83.

19. Ruocco AC, Amirthavasagam S, Choi-Kain LW, et al. Neural correlates of negative emotionality in BPD: an activation-likelihood-estimation meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(2):153-160.

20. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831.

21. Slutske WS. The genetics of antisocial behavior. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3(2):158-162.

22. Ripoll LH, Triebwasser J, Siever LJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(9):1257-1288.

23. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management. Clinical guideline [CG78]. Published January 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antisocial personality disorder: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG77]. Published January 2009. Updated March 27, 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg77

25. Khalifa N, Duggan C, Stoffers J, et al. Pharmacologic interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rep. 2010;(8):CD007667.

26. Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(8):CD005652.

27. Black DW. The treatment of antisocial personality disorder. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-017-0123-z

28. Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, et al. Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(8):708-713.

29. Ansseau M. The obsessive-compulsive personality: diagnostic aspects and treatment possibilities. In: Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, eds. Focus on obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Syn-Thesis; 1997:61-73.

30. Koenigsberg HW, Reynolds D, Goodman M, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of schizotypal personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):628-634.

31. Black DW, Zanarini MC, Romine A, et al. Comparison of low and moderate dosages of extended-release quetiapine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(11):1174-1182.

32. Nickel MK, Muelbacher M, Nickel C, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):833-838.

33. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764.

34. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(12)1660-1665.

35. Cowdry RW, Gardner DL. Pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder. Alprazolam, carbamazepine, trifluoperazine, and tranylcypromine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(2):111-119.

36. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799-812.

37. Ratey JJ, Gutheil CM. The measurement of aggressive behavior: reflections on the use of the Overt Aggression Scale and the Modified Overt Aggression Scale. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 1991;3(2):S57-S60.

38. Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, et al. Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). In: Maruish ME, ed. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999:993-1021.

39. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory II. Psychological Corp; 1996.

40. Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form. The University of Iowa; 1999.

41. Harvey D, Greenberg BR, Serper MR, et al. The affective lability scales: development, reliability, and validity. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45(5):786-793.

42. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): a continuous measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology. J Person Disord. 2003:17(3):233-242.

43. Pfohl B, Blum N, St John D, et al. Reliability and validity of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST): a new scale to measure severity and change in borderline personality disorder. J Person Disord. 2009;23(3):281-293.

44. Ahearn EP. The use of visual analog scales in mood disorders: a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31(5):569-579.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Black DW, Andreasen N. Personality disorders. In: Black DW, Andreasen N. Introductory textbook of psychiatry, 7th edition. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2020:410-423.

3. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord 2004;18(3):226-239.

4. Lieb K, Völlm B, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):4-12.

5. Vita A, De Peri L, Sacchetti E. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and placebo on the symptom dimensions of borderline personality disorder – a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and open-label trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):613-624.

6. Stoffers JM, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder – current evidence and recent trends. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):534.

7. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):345-356.

8. Black DW, Paris J, Schulz SC. Personality disorders: evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M, ed. Cognitive behavioral psychopharmacology: the clinical practice of evidence-based biopsychosocial integration. John Wiley & Sons; 2018:137-165.

9. Stoffers-Winterling J, Sorebø OJ, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: an update of published, unpublished and ongoing studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):37.

10. Lewis G, Appleby L. Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:44-49.

11. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(3):67-74.

12. Langbehn DR, Pfohl BM, Reynolds S, et al. The Iowa Personality Disorder Screen: development and preliminary validation of a brief screening interview. J Pers Disord. 1999;13(1):75-89.

13. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV). American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Part II: multisite test-retest reliability study. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(2):92-104.

15. Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

16. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Treatment rates for patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality disorders: a 16-year study. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):15-20.

17. Black DW, Allen J, McCormick B, et al. Treatment received by persons with BPD participating in a randomized clinical trial of the Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving programme. Person Ment Health. 2011;5(3):159-168.

18. Yang Y, Glenn AL, Raine A. Brain abnormalities in antisocial individuals: implications for the law. Behav Sci Law. 2008;26(1):65-83.

19. Ruocco AC, Amirthavasagam S, Choi-Kain LW, et al. Neural correlates of negative emotionality in BPD: an activation-likelihood-estimation meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(2):153-160.

20. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831.

21. Slutske WS. The genetics of antisocial behavior. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3(2):158-162.

22. Ripoll LH, Triebwasser J, Siever LJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(9):1257-1288.

23. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management. Clinical guideline [CG78]. Published January 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antisocial personality disorder: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG77]. Published January 2009. Updated March 27, 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg77

25. Khalifa N, Duggan C, Stoffers J, et al. Pharmacologic interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rep. 2010;(8):CD007667.

26. Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(8):CD005652.

27. Black DW. The treatment of antisocial personality disorder. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-017-0123-z

28. Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, et al. Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(8):708-713.

29. Ansseau M. The obsessive-compulsive personality: diagnostic aspects and treatment possibilities. In: Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, eds. Focus on obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Syn-Thesis; 1997:61-73.

30. Koenigsberg HW, Reynolds D, Goodman M, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of schizotypal personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):628-634.

31. Black DW, Zanarini MC, Romine A, et al. Comparison of low and moderate dosages of extended-release quetiapine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(11):1174-1182.

32. Nickel MK, Muelbacher M, Nickel C, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):833-838.

33. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764.

34. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(12)1660-1665.

35. Cowdry RW, Gardner DL. Pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder. Alprazolam, carbamazepine, trifluoperazine, and tranylcypromine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(2):111-119.

36. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799-812.

37. Ratey JJ, Gutheil CM. The measurement of aggressive behavior: reflections on the use of the Overt Aggression Scale and the Modified Overt Aggression Scale. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 1991;3(2):S57-S60.

38. Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, et al. Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). In: Maruish ME, ed. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999:993-1021.

39. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory II. Psychological Corp; 1996.

40. Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form. The University of Iowa; 1999.

41. Harvey D, Greenberg BR, Serper MR, et al. The affective lability scales: development, reliability, and validity. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45(5):786-793.

42. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): a continuous measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology. J Person Disord. 2003:17(3):233-242.

43. Pfohl B, Blum N, St John D, et al. Reliability and validity of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST): a new scale to measure severity and change in borderline personality disorder. J Person Disord. 2009;23(3):281-293.

44. Ahearn EP. The use of visual analog scales in mood disorders: a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31(5):569-579.