User login

The diagnosis

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Dysphagia lusoria

Dysphagia may be divided into an oropharyngeal cause or an esophageal cause. Esophageal dysphagia may be due to a luminal narrowing or a motility dysfunction. Causes of luminal narrowing include lesions within the lumen such as a foreign body, lesions within the wall of the esophagus such as a mucosal or submucosal tumor, and extrinsic lesions such as an enlarged mediastinal lymph node or mass. Esophageal dysphagia typically presents with difficulty in swallowing solids compared with liquids.

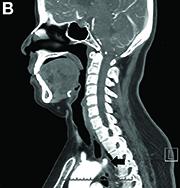

Evaluation of this condition involves a barium swallow study, CTA, or magnetic resonance angiography.2 Both CTA and MRA have largely supplanted the role of conventional angiography, which is invasive. Both CTA and magnetic resonance angiography may also diagnose any other intrathoracic pathology causing esophageal compression. The management of patients with mild to moderate dysphagia is diet modification (minced feeds to well-chewed food; eating slowly and with liquids). Vascular repair of the aberrant vessel is considered only if the patient has severe symptoms and has failed conservative management.3 Because our subject did not have significant weight loss or regurgitation, only dietary advice was offered. An interval outpatient upper endoscopy was planned upon discharge, for which she defaulted.

References

1. Bayford. An account of a singular case of obstructed degluitition. Memoirs of the Medical Society of London. 1794;2:275-86.

2. Alper, F., Akgun, M., Kantarci, M. et al. Demonstration of vascular abnormalities compressing esophagus by MDCT: special focus on dysphagia lusoria. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:82-7.

3. Levitt, B. and Richter, J.E. Dysphagia lusoria: a comprehensive review. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:455-60.

The diagnosis

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Dysphagia lusoria

Dysphagia may be divided into an oropharyngeal cause or an esophageal cause. Esophageal dysphagia may be due to a luminal narrowing or a motility dysfunction. Causes of luminal narrowing include lesions within the lumen such as a foreign body, lesions within the wall of the esophagus such as a mucosal or submucosal tumor, and extrinsic lesions such as an enlarged mediastinal lymph node or mass. Esophageal dysphagia typically presents with difficulty in swallowing solids compared with liquids.

Evaluation of this condition involves a barium swallow study, CTA, or magnetic resonance angiography.2 Both CTA and MRA have largely supplanted the role of conventional angiography, which is invasive. Both CTA and magnetic resonance angiography may also diagnose any other intrathoracic pathology causing esophageal compression. The management of patients with mild to moderate dysphagia is diet modification (minced feeds to well-chewed food; eating slowly and with liquids). Vascular repair of the aberrant vessel is considered only if the patient has severe symptoms and has failed conservative management.3 Because our subject did not have significant weight loss or regurgitation, only dietary advice was offered. An interval outpatient upper endoscopy was planned upon discharge, for which she defaulted.

References

1. Bayford. An account of a singular case of obstructed degluitition. Memoirs of the Medical Society of London. 1794;2:275-86.

2. Alper, F., Akgun, M., Kantarci, M. et al. Demonstration of vascular abnormalities compressing esophagus by MDCT: special focus on dysphagia lusoria. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:82-7.

3. Levitt, B. and Richter, J.E. Dysphagia lusoria: a comprehensive review. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:455-60.

The diagnosis

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Dysphagia lusoria

Dysphagia may be divided into an oropharyngeal cause or an esophageal cause. Esophageal dysphagia may be due to a luminal narrowing or a motility dysfunction. Causes of luminal narrowing include lesions within the lumen such as a foreign body, lesions within the wall of the esophagus such as a mucosal or submucosal tumor, and extrinsic lesions such as an enlarged mediastinal lymph node or mass. Esophageal dysphagia typically presents with difficulty in swallowing solids compared with liquids.

Evaluation of this condition involves a barium swallow study, CTA, or magnetic resonance angiography.2 Both CTA and MRA have largely supplanted the role of conventional angiography, which is invasive. Both CTA and magnetic resonance angiography may also diagnose any other intrathoracic pathology causing esophageal compression. The management of patients with mild to moderate dysphagia is diet modification (minced feeds to well-chewed food; eating slowly and with liquids). Vascular repair of the aberrant vessel is considered only if the patient has severe symptoms and has failed conservative management.3 Because our subject did not have significant weight loss or regurgitation, only dietary advice was offered. An interval outpatient upper endoscopy was planned upon discharge, for which she defaulted.

References

1. Bayford. An account of a singular case of obstructed degluitition. Memoirs of the Medical Society of London. 1794;2:275-86.

2. Alper, F., Akgun, M., Kantarci, M. et al. Demonstration of vascular abnormalities compressing esophagus by MDCT: special focus on dysphagia lusoria. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:82-7.

3. Levitt, B. and Richter, J.E. Dysphagia lusoria: a comprehensive review. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:455-60.

What’s your diagnosis?

By Eric Wee, MD and Ma Clarissa Buenaseda, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144:273,467,468).