User login

Five recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the efficacy of atypical antipsychotics for treating bipolar disorder in children and adolescents, but 4 of these 5 trials remain unpublished. The lag time between the completion of these trials and publication of their results—typically 4 to 5 years1—leaves psychiatrists without important evidence to explain to families and critics2 why they might recommend using these powerful medications in children with mental illness.

This article previews the preliminary results of these 5 RCTs of atypical antipsychotics, offers a treatment algorithm supported by this evidence, and discusses how to manage potentially serious risks when using antipsychotics to treat children and adolescents with bipolar disorder (BPD).

Where do atypical antipsychotics fit in?

Details of the 5 industry-sponsored RCTs of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with bipolar I manic or mixed episodes are summarized in Table 1.3-7 Only the olanzapine study4 has been published; data from the other 4 trials were presented at medical meetings in 2007 and 2008.

Change in Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was the primary outcome measure in these 5 trials, and each compound was more effective than placebo. The trials demonstrated statistically significant and clinically relevant differences between each antipsychotic and placebo. The number needed to treat (NNT)—how many patients need to be treated for 1 to benefit in a controlled clinical trial—ranged from 2 to 4. For comparison, the NNT for statins in the prevention of coronary events is 12 to 22,8 and the NNT in an analysis of trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for pediatric major depressive disorder was 9.9 Thus, an NNT of ≤4 represents a clinically significant effect.

Risperidone is FDA-approved for short-term treatment of acute bipolar I manic or mixed episodes in patients age 10 to 17. Aripiprazole is approved for acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar I manic or mixed episodes (with or without psychosis) as monotherapy or with lithium or valproate in patients age 10 to 17. In June, an FDA advisory committee recommended pediatric bipolar indications for olanzapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone.

‘Mood stabilizers’ such as lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine have been used for years to treat bipolar mania in adults, adolescents, and children, despite limited supporting evidence. Preliminary results of a National Institute of Mental Health-funded double-blind RCT provide insights on their efficacy.10

The 153 outpatients age 7 to 17 in a bipolar I manic or mixed episode were randomly assigned to lithium, divalproex, or placebo for 8 weeks. Response rates—based on a Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement score of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved)—were divalproex, 54%; lithium, 42%; and placebo, 29%. Lithium showed a trend toward efficacy but did not clearly separate from placebo on the primary outcome measures. Effect sizes for lithium and divalproex were moderate.10

Only 1 study has compared a mood stabilizer with an atypical antipsychotic for treating mania in adolescents. In a double-blind trial, DelBello et al11 randomly assigned 50 patients age 12 to 18 with a bipolar I manic or mixed episode to quetiapine, 400 to 600 mg/d, or divalproex, serum level 80 to 120 μg/mL, for 28 days. Manic symptoms resolved more rapidly, and remission rates measured by the YMRS were higher with quetiapine than with divalproex. Both medications were well tolerated.

Combination therapy. BPD as it presents in children and adolescents is often difficult to treat because of the disorder’s various phases (manic, depressed, mixed), frequent psychotic symptoms, and high rate of comorbidity. Pediatric BPD patients frequently require several psychotropics, including mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 30 adolescents in a bipolar I manic or mixed episode initially received divalproex, 20 mg/kg/d, then were randomly assigned to 6 weeks of adjunctive quetiapine, titrated to 450 mg/d in 7 days (n=15), or placebo (n=15). Those receiving divalproex plus quetiapine showed a statistically significant greater reduction in manic symptoms (P=.03) and a higher response rate (87% vs 53%, P=.05), compared with those receiving divalproex and placebo. This suggests that a mood stabilizer plus an atypical antipsychotic is more effective than a mood stabilizer alone for adolescent mania. Quetiapine was well tolerated.12

Treatment. The American Psychiatric Association’s outdated 2002 practice guideline for acute bipolar I manic or mixed episodes in adults recommends lithium, valproate, and/or an antipsychotic.13 The more recent Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) guidelines recommend monotherapy with lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone for adults with euphoric or irritable manic or hypomanic symptoms.14

Based on the TMAP algorithm, recent clinical trial evidence, and our experience in treating pediatric BPD, we offer an approach for treating mania/hypomania in patients age 10 to 17 (see Proposed Algorithm). For dosing and precautions when using atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with BPD, see Table 2.15-17

Comorbid psychiatric illnesses (such as anxiety disorders) are prevalent in adolescents with BPD. Evidence in adults and adolescents suggests that some atypical antipsychotics may provide additional benefit for these conditions as well. Thus, consider comorbid conditions and symptoms when choosing antimanic agents.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common comorbidity in children with BPD, and stimulant medications are most often prescribed to treat inattentiveness and hyperactivity. Caution is imperative when treating bipolar youth with stimulants, which can exacerbate manic symptoms. Treat the patient’s mania before adding or reintroducing stimulant medication. Research and clinical experience suggest that if you first stabilize these patients on a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic, adding a stimulant can be very helpful in treating comorbid ADHD symptoms. Start with low stimulant doses, and increase slowly.

Table 1

RCTs of atypical antipsychotics in patients age 10 to 17

with bipolar I disorder*

| Antipsychotic and source | Bipolar I episode (# of subjects) | Trial duration (days) | Dosage (mg/d) | Response rate or YMRS score change | NNT | Mean weight gain (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone Pandina et al3 AACAP 2007 | Manic, mixed (169) | 21 | 0.5 to 2.5 3 to 6 | 59% 63% | 3.3 3.5 | 1.9 1.4 |

| Olanzapine Tohen et al4 | Manic, mixed (161) | 21 | 10.4 ± 4.5 | 49% | 4.1 | 3.7 ± 2.2 |

| Quetiapine DelBello et al5 AACAP 2007 | Manic (284) | 21 | 400 600 | 64% 58% | 4.4 4.2 | 1.7 1.7 |

| Aripiprazole Wagner et al6 ACNP 2007 | Manic, mixed (296) | 28 | 10 30 | 45% 64% | 4.1 2.4 | 0.9 0.54 |

| Ziprasidone DelBello et al7 APA 2008 | Manic, mixed (238) | 28 | 80 to 160 | –13.83 with ziprasidone, –8.61 with placebo | 3.7 | None |

| *Each trial included a 6-month open extension phase; results are pending | ||||||

| AACAP: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; ACNP: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; APA: American Psychiatric Association; NNT: number needed to treat; RCT: randomized controlled trial; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale | ||||||

Table 2

Recommended antipsychotic use in pediatric bipolar disorder

| Drug | Starting dosage (mg) | Target dosage (mg/d) | Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | 2.5 to 5 at bedtime | 10 to 30 | Monitor for CYP 3A4 and 2D6 interactions, weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, and glucose |

| Olanzapine | 2.5 bid | 10 to 20 | Monitor for CYP 2D6 interactions, weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, glucose, and prolactin levels |

| Quetiapine | 50 bid | 400 to 1,200 | Monitor for weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, and glucose |

| Risperidone | 0.25 bid | 1 to 2.5 | Monitor for EPS, hyperprolactinemia (and associated sexual side effects, including galactorrhea), weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, glucose, and prolactin levels |

| Ziprasidone | 20 bid | 80 to 160 | Check baseline ECG and as dose increases or with reason for high level of concern; monitor prolactin levels |

| BMI: body mass index; CYP: cytochrome P450; ECG: electrocardiography; EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms | |||

| Source: References 15-17 | |||

Proposed Algorithm: Treating a bipolar mixed/manic episode in patients age 10 to 17

Stage 1. Consider patient’s experience with antipsychotics, body weight, and family history when choosing first-line monotherapy (1A). Quetiapine poses low risk for extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia. Aripiprazole and ziprasidone pose relatively low risk of weight gain. Risperidone is potent at low doses but increases prolactin levels (long-term effect unknown).

Second-line choices (1B) are mood stabilizers lithium and valproate (because of lower potency than atypical antipsychotics), and olanzapine (which—although potent—causes substantial weight gain). In case of lack of response or intolerable side effects with initial agent, select an alternate from 1A or 1B. If this is not effective, move to Stage 2.

Stage 2. Consider augmentation for patients who show partial response to monotherapy (in your clinical judgment “mild to moderately improved” but not “much or very much improved”).

Stage 3. Combination therapy could include 2 mood stabilizers (such as lithium and valproate) plus an atypical antipsychotic; 2 atypical antipsychotics; or other combinations based on patient’s past responses. No research has shown these combinations to be efficacious in bipolar children and adolescents, but we find they sometimes help those with treatment-resistant symptoms.

Duration. Maintain psychotropics 12 to 18 months. When patient is euthymic, slowly taper 1 medication across several months. If symptoms recur, reintroduce the mood-stabilizing agent(s).

Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from Kowatch RA, Fristad MA, Findling R, et al. Clinical manual for the management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008

Managing adverse effects

Although clinically effective, atypical antipsychotics may cause serious side effects that must be recognized and managed. These include extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), tardive dyskinesia (TD), weight gain and obesity, hyperlipidemia, increased prolactin levels, and QTc changes. Counsel patients and families about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics when you consider them for children and adolescents with BPD (Table 3).

EPS. Drug-induced parkinsonism and akathisia are the most common EPS in children and adolescents with BPD treated with atypical antipsychotics.18

Correll et al19 reported a 10% rate of EPS in patients treated with aripiprazole. Treatment-emergent EPS also was observed in the RCT of risperidone.20 EPS-related adverse events were associated with higher doses of risperidone, although none of the akathisia/EPS measures were thought to be “clinically significant.”

EPS frequency was relatively low and similar to placebo in the 3-week quetiapine trial,21 and no changes in movement disorder scale scores were observed during the olanzapine or ziprasidone RCTs.4,7

Recommendations. If your pediatric patient develops EPS, first try an antipsychotic dose reduction. Because anticholinergics can contribute to antipsychotic-induced weight gain, reserve them until after a dosage reduction has been unsuccessful.

Benztropine (0.25 to 0.5 mg given 2 to 3 times daily, not to exceed 3 mg/d) or diphenhydramine (25 to 50 mg given 3 to 4 times daily; maximum dosage 5 mg/kg/d) can be effective in treating EPS. Avoid anticholinergics in children with narrow-angle glaucoma or age <3.

Akathisia may be managed with propranolol (20 to 120 mg/d in divided doses). Multiple doses (typically 3 times daily) are needed to prevent interdose withdrawal symptoms. Use this beta blocker with caution in children with asthma because of the possibility of bronchospasm.

TD. Short-term trials and a meta-analysis of atypical antipsychotic trials (>11 months’ duration, subject age <18) suggest a low annual risk for TD (0.4%).22 Large, prospective, long-term trials of atypical antipsychotics are necessary to more accurately define the risk of TD in the pediatric population, however. Retrospective analyses of adolescents treated with antipsychotics suggest 3 TD risk factors:

- early age of antipsychotic use

- medication nonadherence

- concomitant use of antiparkinsonian agents.23

Kumra et al24 identified lower premorbid functioning and greater positive symptoms at baseline as factors associated with “withdrawal dyskinesia/tardive dyskinesia” in children and adolescents with early-onset psychotic-spectrum disorders treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics.

Recommendations. To minimize TD risk, use the lowest effective antipsychotic dose, monitor for abnormal involuntary movements with standardized assessments (such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale), review risks and benefits with parents and patients, and regularly evaluate the indication and need for antipsychotic therapy. It is reasonable to attempt to lower the antipsychotic dose after the patient has attained remission and been stable for 1 year.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). This complication of dopamine-blocking medications:

- is among the most serious adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment

- continues to be associated with a mortality rate of 10%.25

Recommendation. At least 1 recent review of pediatric NMS cases suggests that essential features (hyperthermia and severe muscular rigidity) are retained in children.26 Nonetheless, monitor for variant presentations; hyper thermia or muscle rigidity may be absent or develop slowly over several days in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics.27

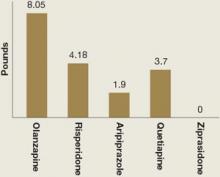

Weight gain and glucose metabolism. A major adverse effect of most atypical antipsychotics is increased appetite, weight gain, and possible obesity.28 In children, “obesity” refers to a body mass index (BMI) >95th percentile for age and sex; “over-weight” refers to BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile. Mean weight gain in the 5 atypical antipsychotic pediatric bipolar trials ranged from 0 to 8 lbs across 3 to 4 weeks of treatment (Figure).3-7

Recommendations. Emphasize diet and exercise, with restriction of high-carbohydrate food, “fast foods,” and soft drinks. Another option is a trial of metformin, which decreases hepatic glucose production, decreases intestinal absorption of glucose, and improves insulin sensitivity by increasing peripheral glucose uptake and utilization.

Klein et al29 studied 39 patients age 10 to 17 with mood and psychotic disorders whose weight increased by >10% during <1 year of olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine therapy. In this 16-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, weight was stabilized in subjects receiving metformin, whereas those receiving placebo continued to gain weight (0.31 kg [0.68 lb]/week).

The usual starting metformin dose is 500 mg bid with meals. Increase in increments of 500 mg weekly, up to a maximum of 2,000 mg/d in divided doses. Potential side effects include diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, flatulence, and headache.

Hyperlipidemia. Patients who gain weight with atypical antipsychotics also may develop hyperlipidemia. Fasting serum triglycerides >150 mg/dL (1.70 mmol/L) in obese children are considered to be elevated and an early sign of metabolic syndrome.30 Fasting total cholesterol >200 mg/dL (5.18 mmol/L) or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >130 mg/dL (3.38 mmol/L) is consistent with hyperlipidemia.

Recommendation. Monitor and treat hyperlipidemia, which increases the risk of atherosclerosis as obese children grow older.31

Prolactin. Elevated prolactin concentrations may have deleterious effects in the developing child or adolescent, including gynecomastia, oligomenorrhea, and amenorrhea.17 Long-term effects on growth and sexual maturation have not been fully evaluated.

The relative tendency of atypical antipsychotics to cause hyperprolactinemia is roughly: risperidone/paliperidone > olanzapine > ziprasidone > quetiapine > clozapine > aripiprazole.18 In the risperidone RCT, mean changes in baseline prolactin levels were 41 ng/mL for boys and 59 ng/mL in girls.3 Results of the olanzapine RCT suggest a high incidence of hyperprolactinemia (26% of girls, 63% of boys).4 Decreases in serum prolactin were observed in bipolar children and adolescents treated with aripiprazole for 30 weeks.19

Recommendations. For any pediatric patient treated with an atypical antipsychotic that increases prolactin levels:

- Obtain a baseline prolactin level.

- Repeat after 6 months of treatment or with the emergence of elevated prolactin symptoms, such as gynecomastia in boys. Ask about increases in breast size, galactorrhea, changes in menstruation, sexual functioning, and pubertal development.

Switch patients who develop any of these side effects to another atypical agent that does not increase serum prolactin.32

QTc interval prolongation. All atypical antipsychotics can cause QTc prolongation. Several cases of significant QTc prolongation have been reported in children and adolescents treated with ziprasidone.33,34 In the RCT of ziprasidone, QTc prolongation was not clinically significant in most of the patients in which it was reported, and it did not lead to adverse events.34 Mean QTc change was 8.1 msec at study termination.7

Patients enrolled in clinical trails are screened very carefully, however, and those with preexisting medical abnormalities typically are excluded. Thus, these findings may have limited usefulness for “real-world” patients.

Recommendations. Until additional information is known about the cardiac effects of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents:

- Perform a careful history, review of symptoms, and physical exam looking for any history of palpitations, shortness of breath, or syncope.

- Query specifically about any family history of sudden cardiac death.

- Perform a baseline resting ECG for patients starting ziprasidone or clozapine, or for other atypicals if indicated by history, review of systems, physical exam, etc.

- For patients treated with ziprasidone or clozapine, repeat ECG as the dose increases or if the patient has cardiac symptoms (unexplained shortness of breath, palpitations, skipped beats, etc.).

Table 3

Talking to families about using antipsychotics

in children with bipolar disorder

| Effectiveness. Large, placebo-controlled studies have shown that atypical antipsychotics can significantly reduce manic symptoms in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder |

| Safety data. Additional 6-month safety data indicate that atypical antipsychotics continue to be effective in children and adolescents, without dramatic changes in side effects |

| Precautions. Antipsychotics are powerful medications and must be used carefully in pediatric patients |

| Potential side effects. All antipsychotics have serious potential side effects that must be recognized, monitored, and managed |

| Potential benefits from using atypical antipsychotics include mood stabilization, treatment of psychotic symptoms, and lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms compared with typical antipsychotics |

| Risk vs benefit. On balance, the potential benefit of these agents outweighs the potential risk for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder |

Figure: Mean weight gain with atypical antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar trials

Weight gain in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder varied among atypical antipsychotics used in 5 recent randomized controlled trials. Treatment duration was 3 weeks with olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine and 4 weeks with aripiprazole and ziprasidone. Dosages were olanzapine, 10.4 ± 4.5 mg/d; risperidone, 0.5 to 2.5 mg/d or 3 to 6 mg/d; aripiprazole, 10 or 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 400 or 600 mg/d; and ziprasidone, 80 to 160 mg/d.

Source: References 3-7Related resources

- Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation. www.bpkids.org.

- University of Illinois at Chicago Pediatric Mood Disorders Clinic. www.psych.uic.edu/pmdc.

- Ryan Licht Sang Bipolar Foundation. www.ryanlichtsangbipolarfoundation.org.

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Metformin • Glucophage

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paliperidone • Invega

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Valproate • Depacon

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Kowatch is a consultant to and speaker for AstraZeneca and a consultant to Forest Pharmaceuticals. He receives research support from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Stanley Foundation.

Dr. Strawn has received research support from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (Lilly Pilot Research Award).

Dr. Sorter receives research support from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Health Foundation of Greater Cincinnati.

1. Hopewell S, Clarke M, Stewart L, et al. Time to publication for results of clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):MR000011.-

2. Carey B. Risks found for youths in new antipsychotics. The New York Times. September 15, 2008:A17.

3. Pandina G, DelBello M, Kushner S, et al. Risperidone for the treatment of acute mania in bipolar youth. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October 23-28, 2007; Boston, MA.

4. Tohen M, Kryzhanovskaya L, Carlson G, et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of adolescents with bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1547-1556.

5. DelBello M, Findling RL, Earley W, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine in children and adolescents with bipolar mania: a 3-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October 23-28, 2007; Boston, MA.

6. Wagner K, Nyilas M, Forbes R, et al. Acute efficacy of aripiprazole for the treatment of bipolar I disorder, mixed or manic, in pediatric patients. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, December 9-13, 2007; Boca Raton, FL.

7. DelBello M, Findling RL, Wang P, et al. Safety and efficacy of ziprasidone in pediatric bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, May 3-8, 2008; Washington, DC.

8. McElduff P, Jaefarnezhad M, Durrington PN. American, British and European recommendations for statins in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease applied to British men studied prospectively. Heart. 2006;92(9):1213-1218.

9. Tsapakis EM, Soldani F, Tondo L, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in juvenile depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(1):10-17.

10. Kowatch R, Findling R, Scheffer R, et al. Placebo controlled trial of divalproex versus lithium for bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; October 23-28, 2007; Boston, MA.

11. DelBello MP, Kowatch RA, Adler CM, et al. A double-blind randomized pilot study comparing quetiapine and divalproex for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(3):305-313.

12. DelBello MP, Schwiers ML, Rosenberg HL, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(10):1216-1223.

13. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 suppl):1-50.

14. Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Hirschfeld RM, et al. The Texas implementation of medication algorithms: update to the algorithms for treatment of bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(7):870-886.

15. Becker AL, Epperson CN. Female puberty: clinical implications for the use of prolactin-modulating psychotropics. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(1):207-220.

16. Correll CU, Penzner JB, Parikh UH, et al. Recognizing and monitoring adverse events of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(1):177-206.

17. Correll CU. Effect of hyperprolactinemia during development in children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(8):e24.-

18. Correll CU. Antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: minimizing adverse effects to maximize outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):9-20.

19. Correll CU, Nyilas M, Ashfaque S, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of aripiprazole in children (10-17 years) with bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 9-13, 2007; Boca Raton, FL.

20. Pandina GJ, Bossie CA, Youssef E, et al. Risperidone improves behavioral symptoms in children with autism in a improves behavioral symptoms in children with autism in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(2):367-373.

21. DelBello M, Findling RL, Earley W, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine in children and adolescent with bipolar mania; a 3-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 9-13, 2007; Boca Raton, FL.

22. Correll CU, Kane JM. One-year incidence rates of tardive dyskinesia in children and adolescents treated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(5):647-656.

23. McDermid SA, Hood J, Bockus S, et al. Adolescents on neuroleptic medication: is this population at risk for tardive dyskinesia? Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43(6):629-631.

24. Kumra S, Jacobsen LK, Lenane M, et al. Case series: spectrum of neuroleptic-induced movement disorders and extrapyramidal side effects in childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):221-227.

25. Strawn JR, Keck PE, Jr, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):870-876.

26. Croarkin PE, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with atypical antipsychotics in pediatric patients: a review of published cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1157-1165.

27. Picard LS, Lindsay S, Strawn JR, et al. Atypical neuroleptic malignant syndrome: diagnostic controversies and considerations. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(4):530-535.

28. Correll CU. Metabolic side effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a different story? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(10):1331-1332.

29. Klein DJ, Cottingham EM, Sorter M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of metformin treatment of weight gain associated with initiation of atypical antipsychotic therapy in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2072-2079.

30. Kavey RE, Allada V, Daniels SR, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science; the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Epidemiology and Prevention, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, High Blood Pressure Research, Cardiovascular Nursing, and the Kidney in Heart Disease; and the Interdisciplinary Working Group on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22(3):218-253.

31. O’Grady MJ, Brown AM, O’Neill MB. Cholesterol screening in an at-risk pediatric population. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29(3):609-613.

32. Ali J, Khemka M. Hyperprolactinemia: monitoring children on long-term risperidone. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(11):64-72.

33. Blair J, Scahill L, State M, et al. Electrocardiographic changes in children and adolescents treated with ziprasidone: a prospective study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(1):73-79.

34. Malone RP, Delaney MA, Hyman SB, et al. Ziprasidone in adolescents with autism: an open-label pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(6):779-790.

Five recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the efficacy of atypical antipsychotics for treating bipolar disorder in children and adolescents, but 4 of these 5 trials remain unpublished. The lag time between the completion of these trials and publication of their results—typically 4 to 5 years1—leaves psychiatrists without important evidence to explain to families and critics2 why they might recommend using these powerful medications in children with mental illness.

This article previews the preliminary results of these 5 RCTs of atypical antipsychotics, offers a treatment algorithm supported by this evidence, and discusses how to manage potentially serious risks when using antipsychotics to treat children and adolescents with bipolar disorder (BPD).

Where do atypical antipsychotics fit in?

Details of the 5 industry-sponsored RCTs of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with bipolar I manic or mixed episodes are summarized in Table 1.3-7 Only the olanzapine study4 has been published; data from the other 4 trials were presented at medical meetings in 2007 and 2008.

Change in Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was the primary outcome measure in these 5 trials, and each compound was more effective than placebo. The trials demonstrated statistically significant and clinically relevant differences between each antipsychotic and placebo. The number needed to treat (NNT)—how many patients need to be treated for 1 to benefit in a controlled clinical trial—ranged from 2 to 4. For comparison, the NNT for statins in the prevention of coronary events is 12 to 22,8 and the NNT in an analysis of trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for pediatric major depressive disorder was 9.9 Thus, an NNT of ≤4 represents a clinically significant effect.

Risperidone is FDA-approved for short-term treatment of acute bipolar I manic or mixed episodes in patients age 10 to 17. Aripiprazole is approved for acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar I manic or mixed episodes (with or without psychosis) as monotherapy or with lithium or valproate in patients age 10 to 17. In June, an FDA advisory committee recommended pediatric bipolar indications for olanzapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone.

‘Mood stabilizers’ such as lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine have been used for years to treat bipolar mania in adults, adolescents, and children, despite limited supporting evidence. Preliminary results of a National Institute of Mental Health-funded double-blind RCT provide insights on their efficacy.10

The 153 outpatients age 7 to 17 in a bipolar I manic or mixed episode were randomly assigned to lithium, divalproex, or placebo for 8 weeks. Response rates—based on a Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement score of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved)—were divalproex, 54%; lithium, 42%; and placebo, 29%. Lithium showed a trend toward efficacy but did not clearly separate from placebo on the primary outcome measures. Effect sizes for lithium and divalproex were moderate.10

Only 1 study has compared a mood stabilizer with an atypical antipsychotic for treating mania in adolescents. In a double-blind trial, DelBello et al11 randomly assigned 50 patients age 12 to 18 with a bipolar I manic or mixed episode to quetiapine, 400 to 600 mg/d, or divalproex, serum level 80 to 120 μg/mL, for 28 days. Manic symptoms resolved more rapidly, and remission rates measured by the YMRS were higher with quetiapine than with divalproex. Both medications were well tolerated.

Combination therapy. BPD as it presents in children and adolescents is often difficult to treat because of the disorder’s various phases (manic, depressed, mixed), frequent psychotic symptoms, and high rate of comorbidity. Pediatric BPD patients frequently require several psychotropics, including mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 30 adolescents in a bipolar I manic or mixed episode initially received divalproex, 20 mg/kg/d, then were randomly assigned to 6 weeks of adjunctive quetiapine, titrated to 450 mg/d in 7 days (n=15), or placebo (n=15). Those receiving divalproex plus quetiapine showed a statistically significant greater reduction in manic symptoms (P=.03) and a higher response rate (87% vs 53%, P=.05), compared with those receiving divalproex and placebo. This suggests that a mood stabilizer plus an atypical antipsychotic is more effective than a mood stabilizer alone for adolescent mania. Quetiapine was well tolerated.12

Treatment. The American Psychiatric Association’s outdated 2002 practice guideline for acute bipolar I manic or mixed episodes in adults recommends lithium, valproate, and/or an antipsychotic.13 The more recent Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) guidelines recommend monotherapy with lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone for adults with euphoric or irritable manic or hypomanic symptoms.14

Based on the TMAP algorithm, recent clinical trial evidence, and our experience in treating pediatric BPD, we offer an approach for treating mania/hypomania in patients age 10 to 17 (see Proposed Algorithm). For dosing and precautions when using atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with BPD, see Table 2.15-17

Comorbid psychiatric illnesses (such as anxiety disorders) are prevalent in adolescents with BPD. Evidence in adults and adolescents suggests that some atypical antipsychotics may provide additional benefit for these conditions as well. Thus, consider comorbid conditions and symptoms when choosing antimanic agents.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common comorbidity in children with BPD, and stimulant medications are most often prescribed to treat inattentiveness and hyperactivity. Caution is imperative when treating bipolar youth with stimulants, which can exacerbate manic symptoms. Treat the patient’s mania before adding or reintroducing stimulant medication. Research and clinical experience suggest that if you first stabilize these patients on a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic, adding a stimulant can be very helpful in treating comorbid ADHD symptoms. Start with low stimulant doses, and increase slowly.

Table 1

RCTs of atypical antipsychotics in patients age 10 to 17

with bipolar I disorder*

| Antipsychotic and source | Bipolar I episode (# of subjects) | Trial duration (days) | Dosage (mg/d) | Response rate or YMRS score change | NNT | Mean weight gain (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone Pandina et al3 AACAP 2007 | Manic, mixed (169) | 21 | 0.5 to 2.5 3 to 6 | 59% 63% | 3.3 3.5 | 1.9 1.4 |

| Olanzapine Tohen et al4 | Manic, mixed (161) | 21 | 10.4 ± 4.5 | 49% | 4.1 | 3.7 ± 2.2 |

| Quetiapine DelBello et al5 AACAP 2007 | Manic (284) | 21 | 400 600 | 64% 58% | 4.4 4.2 | 1.7 1.7 |

| Aripiprazole Wagner et al6 ACNP 2007 | Manic, mixed (296) | 28 | 10 30 | 45% 64% | 4.1 2.4 | 0.9 0.54 |

| Ziprasidone DelBello et al7 APA 2008 | Manic, mixed (238) | 28 | 80 to 160 | –13.83 with ziprasidone, –8.61 with placebo | 3.7 | None |

| *Each trial included a 6-month open extension phase; results are pending | ||||||

| AACAP: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; ACNP: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; APA: American Psychiatric Association; NNT: number needed to treat; RCT: randomized controlled trial; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale | ||||||

Table 2

Recommended antipsychotic use in pediatric bipolar disorder

| Drug | Starting dosage (mg) | Target dosage (mg/d) | Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | 2.5 to 5 at bedtime | 10 to 30 | Monitor for CYP 3A4 and 2D6 interactions, weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, and glucose |

| Olanzapine | 2.5 bid | 10 to 20 | Monitor for CYP 2D6 interactions, weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, glucose, and prolactin levels |

| Quetiapine | 50 bid | 400 to 1,200 | Monitor for weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, and glucose |

| Risperidone | 0.25 bid | 1 to 2.5 | Monitor for EPS, hyperprolactinemia (and associated sexual side effects, including galactorrhea), weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, glucose, and prolactin levels |

| Ziprasidone | 20 bid | 80 to 160 | Check baseline ECG and as dose increases or with reason for high level of concern; monitor prolactin levels |

| BMI: body mass index; CYP: cytochrome P450; ECG: electrocardiography; EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms | |||

| Source: References 15-17 | |||

Proposed Algorithm: Treating a bipolar mixed/manic episode in patients age 10 to 17

Stage 1. Consider patient’s experience with antipsychotics, body weight, and family history when choosing first-line monotherapy (1A). Quetiapine poses low risk for extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia. Aripiprazole and ziprasidone pose relatively low risk of weight gain. Risperidone is potent at low doses but increases prolactin levels (long-term effect unknown).

Second-line choices (1B) are mood stabilizers lithium and valproate (because of lower potency than atypical antipsychotics), and olanzapine (which—although potent—causes substantial weight gain). In case of lack of response or intolerable side effects with initial agent, select an alternate from 1A or 1B. If this is not effective, move to Stage 2.

Stage 2. Consider augmentation for patients who show partial response to monotherapy (in your clinical judgment “mild to moderately improved” but not “much or very much improved”).

Stage 3. Combination therapy could include 2 mood stabilizers (such as lithium and valproate) plus an atypical antipsychotic; 2 atypical antipsychotics; or other combinations based on patient’s past responses. No research has shown these combinations to be efficacious in bipolar children and adolescents, but we find they sometimes help those with treatment-resistant symptoms.

Duration. Maintain psychotropics 12 to 18 months. When patient is euthymic, slowly taper 1 medication across several months. If symptoms recur, reintroduce the mood-stabilizing agent(s).

Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from Kowatch RA, Fristad MA, Findling R, et al. Clinical manual for the management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008

Managing adverse effects

Although clinically effective, atypical antipsychotics may cause serious side effects that must be recognized and managed. These include extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), tardive dyskinesia (TD), weight gain and obesity, hyperlipidemia, increased prolactin levels, and QTc changes. Counsel patients and families about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics when you consider them for children and adolescents with BPD (Table 3).

EPS. Drug-induced parkinsonism and akathisia are the most common EPS in children and adolescents with BPD treated with atypical antipsychotics.18

Correll et al19 reported a 10% rate of EPS in patients treated with aripiprazole. Treatment-emergent EPS also was observed in the RCT of risperidone.20 EPS-related adverse events were associated with higher doses of risperidone, although none of the akathisia/EPS measures were thought to be “clinically significant.”

EPS frequency was relatively low and similar to placebo in the 3-week quetiapine trial,21 and no changes in movement disorder scale scores were observed during the olanzapine or ziprasidone RCTs.4,7

Recommendations. If your pediatric patient develops EPS, first try an antipsychotic dose reduction. Because anticholinergics can contribute to antipsychotic-induced weight gain, reserve them until after a dosage reduction has been unsuccessful.

Benztropine (0.25 to 0.5 mg given 2 to 3 times daily, not to exceed 3 mg/d) or diphenhydramine (25 to 50 mg given 3 to 4 times daily; maximum dosage 5 mg/kg/d) can be effective in treating EPS. Avoid anticholinergics in children with narrow-angle glaucoma or age <3.

Akathisia may be managed with propranolol (20 to 120 mg/d in divided doses). Multiple doses (typically 3 times daily) are needed to prevent interdose withdrawal symptoms. Use this beta blocker with caution in children with asthma because of the possibility of bronchospasm.

TD. Short-term trials and a meta-analysis of atypical antipsychotic trials (>11 months’ duration, subject age <18) suggest a low annual risk for TD (0.4%).22 Large, prospective, long-term trials of atypical antipsychotics are necessary to more accurately define the risk of TD in the pediatric population, however. Retrospective analyses of adolescents treated with antipsychotics suggest 3 TD risk factors:

- early age of antipsychotic use

- medication nonadherence

- concomitant use of antiparkinsonian agents.23

Kumra et al24 identified lower premorbid functioning and greater positive symptoms at baseline as factors associated with “withdrawal dyskinesia/tardive dyskinesia” in children and adolescents with early-onset psychotic-spectrum disorders treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics.

Recommendations. To minimize TD risk, use the lowest effective antipsychotic dose, monitor for abnormal involuntary movements with standardized assessments (such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale), review risks and benefits with parents and patients, and regularly evaluate the indication and need for antipsychotic therapy. It is reasonable to attempt to lower the antipsychotic dose after the patient has attained remission and been stable for 1 year.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). This complication of dopamine-blocking medications:

- is among the most serious adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment

- continues to be associated with a mortality rate of 10%.25

Recommendation. At least 1 recent review of pediatric NMS cases suggests that essential features (hyperthermia and severe muscular rigidity) are retained in children.26 Nonetheless, monitor for variant presentations; hyper thermia or muscle rigidity may be absent or develop slowly over several days in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics.27

Weight gain and glucose metabolism. A major adverse effect of most atypical antipsychotics is increased appetite, weight gain, and possible obesity.28 In children, “obesity” refers to a body mass index (BMI) >95th percentile for age and sex; “over-weight” refers to BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile. Mean weight gain in the 5 atypical antipsychotic pediatric bipolar trials ranged from 0 to 8 lbs across 3 to 4 weeks of treatment (Figure).3-7

Recommendations. Emphasize diet and exercise, with restriction of high-carbohydrate food, “fast foods,” and soft drinks. Another option is a trial of metformin, which decreases hepatic glucose production, decreases intestinal absorption of glucose, and improves insulin sensitivity by increasing peripheral glucose uptake and utilization.

Klein et al29 studied 39 patients age 10 to 17 with mood and psychotic disorders whose weight increased by >10% during <1 year of olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine therapy. In this 16-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, weight was stabilized in subjects receiving metformin, whereas those receiving placebo continued to gain weight (0.31 kg [0.68 lb]/week).

The usual starting metformin dose is 500 mg bid with meals. Increase in increments of 500 mg weekly, up to a maximum of 2,000 mg/d in divided doses. Potential side effects include diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, flatulence, and headache.

Hyperlipidemia. Patients who gain weight with atypical antipsychotics also may develop hyperlipidemia. Fasting serum triglycerides >150 mg/dL (1.70 mmol/L) in obese children are considered to be elevated and an early sign of metabolic syndrome.30 Fasting total cholesterol >200 mg/dL (5.18 mmol/L) or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >130 mg/dL (3.38 mmol/L) is consistent with hyperlipidemia.

Recommendation. Monitor and treat hyperlipidemia, which increases the risk of atherosclerosis as obese children grow older.31

Prolactin. Elevated prolactin concentrations may have deleterious effects in the developing child or adolescent, including gynecomastia, oligomenorrhea, and amenorrhea.17 Long-term effects on growth and sexual maturation have not been fully evaluated.

The relative tendency of atypical antipsychotics to cause hyperprolactinemia is roughly: risperidone/paliperidone > olanzapine > ziprasidone > quetiapine > clozapine > aripiprazole.18 In the risperidone RCT, mean changes in baseline prolactin levels were 41 ng/mL for boys and 59 ng/mL in girls.3 Results of the olanzapine RCT suggest a high incidence of hyperprolactinemia (26% of girls, 63% of boys).4 Decreases in serum prolactin were observed in bipolar children and adolescents treated with aripiprazole for 30 weeks.19

Recommendations. For any pediatric patient treated with an atypical antipsychotic that increases prolactin levels:

- Obtain a baseline prolactin level.

- Repeat after 6 months of treatment or with the emergence of elevated prolactin symptoms, such as gynecomastia in boys. Ask about increases in breast size, galactorrhea, changes in menstruation, sexual functioning, and pubertal development.

Switch patients who develop any of these side effects to another atypical agent that does not increase serum prolactin.32

QTc interval prolongation. All atypical antipsychotics can cause QTc prolongation. Several cases of significant QTc prolongation have been reported in children and adolescents treated with ziprasidone.33,34 In the RCT of ziprasidone, QTc prolongation was not clinically significant in most of the patients in which it was reported, and it did not lead to adverse events.34 Mean QTc change was 8.1 msec at study termination.7

Patients enrolled in clinical trails are screened very carefully, however, and those with preexisting medical abnormalities typically are excluded. Thus, these findings may have limited usefulness for “real-world” patients.

Recommendations. Until additional information is known about the cardiac effects of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents:

- Perform a careful history, review of symptoms, and physical exam looking for any history of palpitations, shortness of breath, or syncope.

- Query specifically about any family history of sudden cardiac death.

- Perform a baseline resting ECG for patients starting ziprasidone or clozapine, or for other atypicals if indicated by history, review of systems, physical exam, etc.

- For patients treated with ziprasidone or clozapine, repeat ECG as the dose increases or if the patient has cardiac symptoms (unexplained shortness of breath, palpitations, skipped beats, etc.).

Table 3

Talking to families about using antipsychotics

in children with bipolar disorder

| Effectiveness. Large, placebo-controlled studies have shown that atypical antipsychotics can significantly reduce manic symptoms in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder |

| Safety data. Additional 6-month safety data indicate that atypical antipsychotics continue to be effective in children and adolescents, without dramatic changes in side effects |

| Precautions. Antipsychotics are powerful medications and must be used carefully in pediatric patients |

| Potential side effects. All antipsychotics have serious potential side effects that must be recognized, monitored, and managed |

| Potential benefits from using atypical antipsychotics include mood stabilization, treatment of psychotic symptoms, and lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms compared with typical antipsychotics |

| Risk vs benefit. On balance, the potential benefit of these agents outweighs the potential risk for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder |

Figure: Mean weight gain with atypical antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar trials

Weight gain in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder varied among atypical antipsychotics used in 5 recent randomized controlled trials. Treatment duration was 3 weeks with olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine and 4 weeks with aripiprazole and ziprasidone. Dosages were olanzapine, 10.4 ± 4.5 mg/d; risperidone, 0.5 to 2.5 mg/d or 3 to 6 mg/d; aripiprazole, 10 or 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 400 or 600 mg/d; and ziprasidone, 80 to 160 mg/d.

Source: References 3-7Related resources

- Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation. www.bpkids.org.

- University of Illinois at Chicago Pediatric Mood Disorders Clinic. www.psych.uic.edu/pmdc.

- Ryan Licht Sang Bipolar Foundation. www.ryanlichtsangbipolarfoundation.org.

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Metformin • Glucophage

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paliperidone • Invega

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Valproate • Depacon

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Kowatch is a consultant to and speaker for AstraZeneca and a consultant to Forest Pharmaceuticals. He receives research support from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Stanley Foundation.

Dr. Strawn has received research support from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (Lilly Pilot Research Award).

Dr. Sorter receives research support from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Health Foundation of Greater Cincinnati.

Five recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the efficacy of atypical antipsychotics for treating bipolar disorder in children and adolescents, but 4 of these 5 trials remain unpublished. The lag time between the completion of these trials and publication of their results—typically 4 to 5 years1—leaves psychiatrists without important evidence to explain to families and critics2 why they might recommend using these powerful medications in children with mental illness.

This article previews the preliminary results of these 5 RCTs of atypical antipsychotics, offers a treatment algorithm supported by this evidence, and discusses how to manage potentially serious risks when using antipsychotics to treat children and adolescents with bipolar disorder (BPD).

Where do atypical antipsychotics fit in?

Details of the 5 industry-sponsored RCTs of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with bipolar I manic or mixed episodes are summarized in Table 1.3-7 Only the olanzapine study4 has been published; data from the other 4 trials were presented at medical meetings in 2007 and 2008.

Change in Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was the primary outcome measure in these 5 trials, and each compound was more effective than placebo. The trials demonstrated statistically significant and clinically relevant differences between each antipsychotic and placebo. The number needed to treat (NNT)—how many patients need to be treated for 1 to benefit in a controlled clinical trial—ranged from 2 to 4. For comparison, the NNT for statins in the prevention of coronary events is 12 to 22,8 and the NNT in an analysis of trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for pediatric major depressive disorder was 9.9 Thus, an NNT of ≤4 represents a clinically significant effect.

Risperidone is FDA-approved for short-term treatment of acute bipolar I manic or mixed episodes in patients age 10 to 17. Aripiprazole is approved for acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar I manic or mixed episodes (with or without psychosis) as monotherapy or with lithium or valproate in patients age 10 to 17. In June, an FDA advisory committee recommended pediatric bipolar indications for olanzapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone.

‘Mood stabilizers’ such as lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine have been used for years to treat bipolar mania in adults, adolescents, and children, despite limited supporting evidence. Preliminary results of a National Institute of Mental Health-funded double-blind RCT provide insights on their efficacy.10

The 153 outpatients age 7 to 17 in a bipolar I manic or mixed episode were randomly assigned to lithium, divalproex, or placebo for 8 weeks. Response rates—based on a Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement score of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved)—were divalproex, 54%; lithium, 42%; and placebo, 29%. Lithium showed a trend toward efficacy but did not clearly separate from placebo on the primary outcome measures. Effect sizes for lithium and divalproex were moderate.10

Only 1 study has compared a mood stabilizer with an atypical antipsychotic for treating mania in adolescents. In a double-blind trial, DelBello et al11 randomly assigned 50 patients age 12 to 18 with a bipolar I manic or mixed episode to quetiapine, 400 to 600 mg/d, or divalproex, serum level 80 to 120 μg/mL, for 28 days. Manic symptoms resolved more rapidly, and remission rates measured by the YMRS were higher with quetiapine than with divalproex. Both medications were well tolerated.

Combination therapy. BPD as it presents in children and adolescents is often difficult to treat because of the disorder’s various phases (manic, depressed, mixed), frequent psychotic symptoms, and high rate of comorbidity. Pediatric BPD patients frequently require several psychotropics, including mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 30 adolescents in a bipolar I manic or mixed episode initially received divalproex, 20 mg/kg/d, then were randomly assigned to 6 weeks of adjunctive quetiapine, titrated to 450 mg/d in 7 days (n=15), or placebo (n=15). Those receiving divalproex plus quetiapine showed a statistically significant greater reduction in manic symptoms (P=.03) and a higher response rate (87% vs 53%, P=.05), compared with those receiving divalproex and placebo. This suggests that a mood stabilizer plus an atypical antipsychotic is more effective than a mood stabilizer alone for adolescent mania. Quetiapine was well tolerated.12

Treatment. The American Psychiatric Association’s outdated 2002 practice guideline for acute bipolar I manic or mixed episodes in adults recommends lithium, valproate, and/or an antipsychotic.13 The more recent Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) guidelines recommend monotherapy with lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone for adults with euphoric or irritable manic or hypomanic symptoms.14

Based on the TMAP algorithm, recent clinical trial evidence, and our experience in treating pediatric BPD, we offer an approach for treating mania/hypomania in patients age 10 to 17 (see Proposed Algorithm). For dosing and precautions when using atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with BPD, see Table 2.15-17

Comorbid psychiatric illnesses (such as anxiety disorders) are prevalent in adolescents with BPD. Evidence in adults and adolescents suggests that some atypical antipsychotics may provide additional benefit for these conditions as well. Thus, consider comorbid conditions and symptoms when choosing antimanic agents.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common comorbidity in children with BPD, and stimulant medications are most often prescribed to treat inattentiveness and hyperactivity. Caution is imperative when treating bipolar youth with stimulants, which can exacerbate manic symptoms. Treat the patient’s mania before adding or reintroducing stimulant medication. Research and clinical experience suggest that if you first stabilize these patients on a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic, adding a stimulant can be very helpful in treating comorbid ADHD symptoms. Start with low stimulant doses, and increase slowly.

Table 1

RCTs of atypical antipsychotics in patients age 10 to 17

with bipolar I disorder*

| Antipsychotic and source | Bipolar I episode (# of subjects) | Trial duration (days) | Dosage (mg/d) | Response rate or YMRS score change | NNT | Mean weight gain (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone Pandina et al3 AACAP 2007 | Manic, mixed (169) | 21 | 0.5 to 2.5 3 to 6 | 59% 63% | 3.3 3.5 | 1.9 1.4 |

| Olanzapine Tohen et al4 | Manic, mixed (161) | 21 | 10.4 ± 4.5 | 49% | 4.1 | 3.7 ± 2.2 |

| Quetiapine DelBello et al5 AACAP 2007 | Manic (284) | 21 | 400 600 | 64% 58% | 4.4 4.2 | 1.7 1.7 |

| Aripiprazole Wagner et al6 ACNP 2007 | Manic, mixed (296) | 28 | 10 30 | 45% 64% | 4.1 2.4 | 0.9 0.54 |

| Ziprasidone DelBello et al7 APA 2008 | Manic, mixed (238) | 28 | 80 to 160 | –13.83 with ziprasidone, –8.61 with placebo | 3.7 | None |

| *Each trial included a 6-month open extension phase; results are pending | ||||||

| AACAP: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; ACNP: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; APA: American Psychiatric Association; NNT: number needed to treat; RCT: randomized controlled trial; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale | ||||||

Table 2

Recommended antipsychotic use in pediatric bipolar disorder

| Drug | Starting dosage (mg) | Target dosage (mg/d) | Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | 2.5 to 5 at bedtime | 10 to 30 | Monitor for CYP 3A4 and 2D6 interactions, weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, and glucose |

| Olanzapine | 2.5 bid | 10 to 20 | Monitor for CYP 2D6 interactions, weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, glucose, and prolactin levels |

| Quetiapine | 50 bid | 400 to 1,200 | Monitor for weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, and glucose |

| Risperidone | 0.25 bid | 1 to 2.5 | Monitor for EPS, hyperprolactinemia (and associated sexual side effects, including galactorrhea), weight, BMI, cholesterol, lipids, glucose, and prolactin levels |

| Ziprasidone | 20 bid | 80 to 160 | Check baseline ECG and as dose increases or with reason for high level of concern; monitor prolactin levels |

| BMI: body mass index; CYP: cytochrome P450; ECG: electrocardiography; EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms | |||

| Source: References 15-17 | |||

Proposed Algorithm: Treating a bipolar mixed/manic episode in patients age 10 to 17

Stage 1. Consider patient’s experience with antipsychotics, body weight, and family history when choosing first-line monotherapy (1A). Quetiapine poses low risk for extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia. Aripiprazole and ziprasidone pose relatively low risk of weight gain. Risperidone is potent at low doses but increases prolactin levels (long-term effect unknown).

Second-line choices (1B) are mood stabilizers lithium and valproate (because of lower potency than atypical antipsychotics), and olanzapine (which—although potent—causes substantial weight gain). In case of lack of response or intolerable side effects with initial agent, select an alternate from 1A or 1B. If this is not effective, move to Stage 2.

Stage 2. Consider augmentation for patients who show partial response to monotherapy (in your clinical judgment “mild to moderately improved” but not “much or very much improved”).

Stage 3. Combination therapy could include 2 mood stabilizers (such as lithium and valproate) plus an atypical antipsychotic; 2 atypical antipsychotics; or other combinations based on patient’s past responses. No research has shown these combinations to be efficacious in bipolar children and adolescents, but we find they sometimes help those with treatment-resistant symptoms.

Duration. Maintain psychotropics 12 to 18 months. When patient is euthymic, slowly taper 1 medication across several months. If symptoms recur, reintroduce the mood-stabilizing agent(s).

Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from Kowatch RA, Fristad MA, Findling R, et al. Clinical manual for the management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008

Managing adverse effects

Although clinically effective, atypical antipsychotics may cause serious side effects that must be recognized and managed. These include extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), tardive dyskinesia (TD), weight gain and obesity, hyperlipidemia, increased prolactin levels, and QTc changes. Counsel patients and families about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics when you consider them for children and adolescents with BPD (Table 3).

EPS. Drug-induced parkinsonism and akathisia are the most common EPS in children and adolescents with BPD treated with atypical antipsychotics.18

Correll et al19 reported a 10% rate of EPS in patients treated with aripiprazole. Treatment-emergent EPS also was observed in the RCT of risperidone.20 EPS-related adverse events were associated with higher doses of risperidone, although none of the akathisia/EPS measures were thought to be “clinically significant.”

EPS frequency was relatively low and similar to placebo in the 3-week quetiapine trial,21 and no changes in movement disorder scale scores were observed during the olanzapine or ziprasidone RCTs.4,7

Recommendations. If your pediatric patient develops EPS, first try an antipsychotic dose reduction. Because anticholinergics can contribute to antipsychotic-induced weight gain, reserve them until after a dosage reduction has been unsuccessful.

Benztropine (0.25 to 0.5 mg given 2 to 3 times daily, not to exceed 3 mg/d) or diphenhydramine (25 to 50 mg given 3 to 4 times daily; maximum dosage 5 mg/kg/d) can be effective in treating EPS. Avoid anticholinergics in children with narrow-angle glaucoma or age <3.

Akathisia may be managed with propranolol (20 to 120 mg/d in divided doses). Multiple doses (typically 3 times daily) are needed to prevent interdose withdrawal symptoms. Use this beta blocker with caution in children with asthma because of the possibility of bronchospasm.

TD. Short-term trials and a meta-analysis of atypical antipsychotic trials (>11 months’ duration, subject age <18) suggest a low annual risk for TD (0.4%).22 Large, prospective, long-term trials of atypical antipsychotics are necessary to more accurately define the risk of TD in the pediatric population, however. Retrospective analyses of adolescents treated with antipsychotics suggest 3 TD risk factors:

- early age of antipsychotic use

- medication nonadherence

- concomitant use of antiparkinsonian agents.23

Kumra et al24 identified lower premorbid functioning and greater positive symptoms at baseline as factors associated with “withdrawal dyskinesia/tardive dyskinesia” in children and adolescents with early-onset psychotic-spectrum disorders treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics.

Recommendations. To minimize TD risk, use the lowest effective antipsychotic dose, monitor for abnormal involuntary movements with standardized assessments (such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale), review risks and benefits with parents and patients, and regularly evaluate the indication and need for antipsychotic therapy. It is reasonable to attempt to lower the antipsychotic dose after the patient has attained remission and been stable for 1 year.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). This complication of dopamine-blocking medications:

- is among the most serious adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment

- continues to be associated with a mortality rate of 10%.25

Recommendation. At least 1 recent review of pediatric NMS cases suggests that essential features (hyperthermia and severe muscular rigidity) are retained in children.26 Nonetheless, monitor for variant presentations; hyper thermia or muscle rigidity may be absent or develop slowly over several days in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics.27

Weight gain and glucose metabolism. A major adverse effect of most atypical antipsychotics is increased appetite, weight gain, and possible obesity.28 In children, “obesity” refers to a body mass index (BMI) >95th percentile for age and sex; “over-weight” refers to BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile. Mean weight gain in the 5 atypical antipsychotic pediatric bipolar trials ranged from 0 to 8 lbs across 3 to 4 weeks of treatment (Figure).3-7

Recommendations. Emphasize diet and exercise, with restriction of high-carbohydrate food, “fast foods,” and soft drinks. Another option is a trial of metformin, which decreases hepatic glucose production, decreases intestinal absorption of glucose, and improves insulin sensitivity by increasing peripheral glucose uptake and utilization.

Klein et al29 studied 39 patients age 10 to 17 with mood and psychotic disorders whose weight increased by >10% during <1 year of olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine therapy. In this 16-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, weight was stabilized in subjects receiving metformin, whereas those receiving placebo continued to gain weight (0.31 kg [0.68 lb]/week).

The usual starting metformin dose is 500 mg bid with meals. Increase in increments of 500 mg weekly, up to a maximum of 2,000 mg/d in divided doses. Potential side effects include diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, flatulence, and headache.

Hyperlipidemia. Patients who gain weight with atypical antipsychotics also may develop hyperlipidemia. Fasting serum triglycerides >150 mg/dL (1.70 mmol/L) in obese children are considered to be elevated and an early sign of metabolic syndrome.30 Fasting total cholesterol >200 mg/dL (5.18 mmol/L) or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >130 mg/dL (3.38 mmol/L) is consistent with hyperlipidemia.

Recommendation. Monitor and treat hyperlipidemia, which increases the risk of atherosclerosis as obese children grow older.31

Prolactin. Elevated prolactin concentrations may have deleterious effects in the developing child or adolescent, including gynecomastia, oligomenorrhea, and amenorrhea.17 Long-term effects on growth and sexual maturation have not been fully evaluated.

The relative tendency of atypical antipsychotics to cause hyperprolactinemia is roughly: risperidone/paliperidone > olanzapine > ziprasidone > quetiapine > clozapine > aripiprazole.18 In the risperidone RCT, mean changes in baseline prolactin levels were 41 ng/mL for boys and 59 ng/mL in girls.3 Results of the olanzapine RCT suggest a high incidence of hyperprolactinemia (26% of girls, 63% of boys).4 Decreases in serum prolactin were observed in bipolar children and adolescents treated with aripiprazole for 30 weeks.19

Recommendations. For any pediatric patient treated with an atypical antipsychotic that increases prolactin levels:

- Obtain a baseline prolactin level.

- Repeat after 6 months of treatment or with the emergence of elevated prolactin symptoms, such as gynecomastia in boys. Ask about increases in breast size, galactorrhea, changes in menstruation, sexual functioning, and pubertal development.

Switch patients who develop any of these side effects to another atypical agent that does not increase serum prolactin.32

QTc interval prolongation. All atypical antipsychotics can cause QTc prolongation. Several cases of significant QTc prolongation have been reported in children and adolescents treated with ziprasidone.33,34 In the RCT of ziprasidone, QTc prolongation was not clinically significant in most of the patients in which it was reported, and it did not lead to adverse events.34 Mean QTc change was 8.1 msec at study termination.7

Patients enrolled in clinical trails are screened very carefully, however, and those with preexisting medical abnormalities typically are excluded. Thus, these findings may have limited usefulness for “real-world” patients.

Recommendations. Until additional information is known about the cardiac effects of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents:

- Perform a careful history, review of symptoms, and physical exam looking for any history of palpitations, shortness of breath, or syncope.

- Query specifically about any family history of sudden cardiac death.

- Perform a baseline resting ECG for patients starting ziprasidone or clozapine, or for other atypicals if indicated by history, review of systems, physical exam, etc.

- For patients treated with ziprasidone or clozapine, repeat ECG as the dose increases or if the patient has cardiac symptoms (unexplained shortness of breath, palpitations, skipped beats, etc.).

Table 3

Talking to families about using antipsychotics

in children with bipolar disorder

| Effectiveness. Large, placebo-controlled studies have shown that atypical antipsychotics can significantly reduce manic symptoms in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder |

| Safety data. Additional 6-month safety data indicate that atypical antipsychotics continue to be effective in children and adolescents, without dramatic changes in side effects |

| Precautions. Antipsychotics are powerful medications and must be used carefully in pediatric patients |

| Potential side effects. All antipsychotics have serious potential side effects that must be recognized, monitored, and managed |

| Potential benefits from using atypical antipsychotics include mood stabilization, treatment of psychotic symptoms, and lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms compared with typical antipsychotics |

| Risk vs benefit. On balance, the potential benefit of these agents outweighs the potential risk for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder |

Figure: Mean weight gain with atypical antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar trials

Weight gain in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder varied among atypical antipsychotics used in 5 recent randomized controlled trials. Treatment duration was 3 weeks with olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine and 4 weeks with aripiprazole and ziprasidone. Dosages were olanzapine, 10.4 ± 4.5 mg/d; risperidone, 0.5 to 2.5 mg/d or 3 to 6 mg/d; aripiprazole, 10 or 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 400 or 600 mg/d; and ziprasidone, 80 to 160 mg/d.

Source: References 3-7Related resources

- Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation. www.bpkids.org.

- University of Illinois at Chicago Pediatric Mood Disorders Clinic. www.psych.uic.edu/pmdc.

- Ryan Licht Sang Bipolar Foundation. www.ryanlichtsangbipolarfoundation.org.

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Metformin • Glucophage

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paliperidone • Invega

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Valproate • Depacon

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Kowatch is a consultant to and speaker for AstraZeneca and a consultant to Forest Pharmaceuticals. He receives research support from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Stanley Foundation.

Dr. Strawn has received research support from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (Lilly Pilot Research Award).

Dr. Sorter receives research support from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Health Foundation of Greater Cincinnati.

1. Hopewell S, Clarke M, Stewart L, et al. Time to publication for results of clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):MR000011.-

2. Carey B. Risks found for youths in new antipsychotics. The New York Times. September 15, 2008:A17.

3. Pandina G, DelBello M, Kushner S, et al. Risperidone for the treatment of acute mania in bipolar youth. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October 23-28, 2007; Boston, MA.

4. Tohen M, Kryzhanovskaya L, Carlson G, et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of adolescents with bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1547-1556.

5. DelBello M, Findling RL, Earley W, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine in children and adolescents with bipolar mania: a 3-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October 23-28, 2007; Boston, MA.

6. Wagner K, Nyilas M, Forbes R, et al. Acute efficacy of aripiprazole for the treatment of bipolar I disorder, mixed or manic, in pediatric patients. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, December 9-13, 2007; Boca Raton, FL.

7. DelBello M, Findling RL, Wang P, et al. Safety and efficacy of ziprasidone in pediatric bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, May 3-8, 2008; Washington, DC.

8. McElduff P, Jaefarnezhad M, Durrington PN. American, British and European recommendations for statins in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease applied to British men studied prospectively. Heart. 2006;92(9):1213-1218.

9. Tsapakis EM, Soldani F, Tondo L, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in juvenile depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(1):10-17.

10. Kowatch R, Findling R, Scheffer R, et al. Placebo controlled trial of divalproex versus lithium for bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; October 23-28, 2007; Boston, MA.

11. DelBello MP, Kowatch RA, Adler CM, et al. A double-blind randomized pilot study comparing quetiapine and divalproex for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(3):305-313.

12. DelBello MP, Schwiers ML, Rosenberg HL, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(10):1216-1223.

13. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 suppl):1-50.

14. Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Hirschfeld RM, et al. The Texas implementation of medication algorithms: update to the algorithms for treatment of bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(7):870-886.

15. Becker AL, Epperson CN. Female puberty: clinical implications for the use of prolactin-modulating psychotropics. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(1):207-220.

16. Correll CU, Penzner JB, Parikh UH, et al. Recognizing and monitoring adverse events of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(1):177-206.

17. Correll CU. Effect of hyperprolactinemia during development in children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(8):e24.-

18. Correll CU. Antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: minimizing adverse effects to maximize outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):9-20.

19. Correll CU, Nyilas M, Ashfaque S, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of aripiprazole in children (10-17 years) with bipolar disorder. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 9-13, 2007; Boca Raton, FL.

20. Pandina GJ, Bossie CA, Youssef E, et al. Risperidone improves behavioral symptoms in children with autism in a improves behavioral symptoms in children with autism in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(2):367-373.

21. DelBello M, Findling RL, Earley W, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine in children and adolescent with bipolar mania; a 3-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 9-13, 2007; Boca Raton, FL.

22. Correll CU, Kane JM. One-year incidence rates of tardive dyskinesia in children and adolescents treated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(5):647-656.

23. McDermid SA, Hood J, Bockus S, et al. Adolescents on neuroleptic medication: is this population at risk for tardive dyskinesia? Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43(6):629-631.

24. Kumra S, Jacobsen LK, Lenane M, et al. Case series: spectrum of neuroleptic-induced movement disorders and extrapyramidal side effects in childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):221-227.

25. Strawn JR, Keck PE, Jr, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):870-876.

26. Croarkin PE, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with atypical antipsychotics in pediatric patients: a review of published cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1157-1165.

27. Picard LS, Lindsay S, Strawn JR, et al. Atypical neuroleptic malignant syndrome: diagnostic controversies and considerations. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(4):530-535.

28. Correll CU. Metabolic side effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a different story? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(10):1331-1332.

29. Klein DJ, Cottingham EM, Sorter M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of metformin treatment of weight gain associated with initiation of atypical antipsychotic therapy in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2072-2079.