User login

A relative lack of important neurotransmitters is popularly believed to cause depression. This “monoamine hypothesis” makes sense: We give patients “chemicals,” and many depression symptoms improve. Just because an antidepressant works, however, does not mean that a “chemical imbalance” is causing the depression.

For one, 40 years of research has not consistently found diminished neurotransmitters or their metabolites in depressed persons. Also, the monoamine hypothesis fails to explain why clinical improvement can be delayed for weeks, even though antidepressants rapidly increase extracellular serotonin and norepinephrine.

Figure 1 How neural cells differentiate in the brain

In neurogenesis, undifferentiated neural stem cells proliferate and migrate in the brain. Approximately one-half develop into useful cells, such as neurons and glial cells, and one-half die.

Source: Ilustration for CURRENTPSYCHIATRY by Maura Flynn

Increasing evidence suggests that depression may be a subtle neurodegenerative disorder. Postmortem and imaging studies have consistently found atrophy or neuron loss in the prefrontal cortices and hippocampi of depressed patients.1 Some studies suggest that antidepressants prevent the atrophy.2

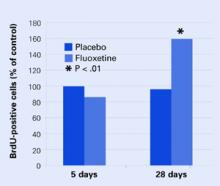

Figure 2 Neural cell development may explain delayed antidepressant effect

In mouse brains, fluoxetine—but not placebo—increased the number of recently developed neuralcells (as shown by the injected marker 5-bromo-2’- deoxyuridine [BrdU]), but only after 28 days.

Source: Adapted from reference 4.

NEW VIEWS ON NEUROGENESIS

Until recently, the brain was believed incapable of generating nerve cells. We were thought to be born with our entire allotment of brain cells and we could only lose them because of age, trauma, or toxins. Within the past 5 years, however, it has become clear that human neuronal stem cells are capable of neurogenesis (Figure 1).3

Neurogenesis is an ongoing process in the brain, and depression may result from a relative decrease in new neuron development. Effective depression treatments may work by stimulating neurogenesis, and Santarelli et al4 offer compelling support for this idea.

A group of mice was treated orally with fluoxetine or placebo. Several from each group were sacrificed after 5 days and others at 28 days. Twenty-four hours before being sacrificed, each mouse was injected with 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU), which is incorporated into DNA and serves as a marker for recently developed nerve cells.

None of the mice at 5 days showed any change in BrdU-positive cells, and only the mice who received fluoxetine showed an increase in new cells after 28 days Figure 2. These results correlated with a greater willingness after 28 days by those mice on fluoxetine to venture into open, lighted areas—a behavioral change that was not seen at 5 days or in the placebo group.

This study shows that an antidepressant can increase development of new neurons and does so in a time course similar to the onset of efficacy seen in human clinical trials.

CHEMICAL OR CELLULAR?

One can speculate that insufficient neurogenesis is a possible cause of depression and that effective depression treatments may reverse that problem. Supporting this concept are other studies showing that lithium and electroconvulsive therapy—well-known treatments for depression—also increase neurogenesis.5

All this evidence makes depression look more like a cellular than a chemical imbalance.

1. Manji HK, Quiroz JA, Sporn J, et al. Enhancing neuronal plasticity and cellular resilience to develop novel, improved therapeutics for difficult-to-treat depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53:707-42.

2. Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1516-8.

3. Gage FH. Brain, repair yourself. Sci Am 2003;289:46-53.

4. Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science 2003;301:805-9.

5. Kempermann G, Kronenberg G. Depressed new neurons—adult hippocampal neurogenesis and a cellular plasticity hypothesis of major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:499-503.

A relative lack of important neurotransmitters is popularly believed to cause depression. This “monoamine hypothesis” makes sense: We give patients “chemicals,” and many depression symptoms improve. Just because an antidepressant works, however, does not mean that a “chemical imbalance” is causing the depression.

For one, 40 years of research has not consistently found diminished neurotransmitters or their metabolites in depressed persons. Also, the monoamine hypothesis fails to explain why clinical improvement can be delayed for weeks, even though antidepressants rapidly increase extracellular serotonin and norepinephrine.

Figure 1 How neural cells differentiate in the brain

In neurogenesis, undifferentiated neural stem cells proliferate and migrate in the brain. Approximately one-half develop into useful cells, such as neurons and glial cells, and one-half die.

Source: Ilustration for CURRENTPSYCHIATRY by Maura Flynn

Increasing evidence suggests that depression may be a subtle neurodegenerative disorder. Postmortem and imaging studies have consistently found atrophy or neuron loss in the prefrontal cortices and hippocampi of depressed patients.1 Some studies suggest that antidepressants prevent the atrophy.2

Figure 2 Neural cell development may explain delayed antidepressant effect

In mouse brains, fluoxetine—but not placebo—increased the number of recently developed neuralcells (as shown by the injected marker 5-bromo-2’- deoxyuridine [BrdU]), but only after 28 days.

Source: Adapted from reference 4.

NEW VIEWS ON NEUROGENESIS

Until recently, the brain was believed incapable of generating nerve cells. We were thought to be born with our entire allotment of brain cells and we could only lose them because of age, trauma, or toxins. Within the past 5 years, however, it has become clear that human neuronal stem cells are capable of neurogenesis (Figure 1).3

Neurogenesis is an ongoing process in the brain, and depression may result from a relative decrease in new neuron development. Effective depression treatments may work by stimulating neurogenesis, and Santarelli et al4 offer compelling support for this idea.

A group of mice was treated orally with fluoxetine or placebo. Several from each group were sacrificed after 5 days and others at 28 days. Twenty-four hours before being sacrificed, each mouse was injected with 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU), which is incorporated into DNA and serves as a marker for recently developed nerve cells.

None of the mice at 5 days showed any change in BrdU-positive cells, and only the mice who received fluoxetine showed an increase in new cells after 28 days Figure 2. These results correlated with a greater willingness after 28 days by those mice on fluoxetine to venture into open, lighted areas—a behavioral change that was not seen at 5 days or in the placebo group.

This study shows that an antidepressant can increase development of new neurons and does so in a time course similar to the onset of efficacy seen in human clinical trials.

CHEMICAL OR CELLULAR?

One can speculate that insufficient neurogenesis is a possible cause of depression and that effective depression treatments may reverse that problem. Supporting this concept are other studies showing that lithium and electroconvulsive therapy—well-known treatments for depression—also increase neurogenesis.5

All this evidence makes depression look more like a cellular than a chemical imbalance.

A relative lack of important neurotransmitters is popularly believed to cause depression. This “monoamine hypothesis” makes sense: We give patients “chemicals,” and many depression symptoms improve. Just because an antidepressant works, however, does not mean that a “chemical imbalance” is causing the depression.

For one, 40 years of research has not consistently found diminished neurotransmitters or their metabolites in depressed persons. Also, the monoamine hypothesis fails to explain why clinical improvement can be delayed for weeks, even though antidepressants rapidly increase extracellular serotonin and norepinephrine.

Figure 1 How neural cells differentiate in the brain

In neurogenesis, undifferentiated neural stem cells proliferate and migrate in the brain. Approximately one-half develop into useful cells, such as neurons and glial cells, and one-half die.

Source: Ilustration for CURRENTPSYCHIATRY by Maura Flynn

Increasing evidence suggests that depression may be a subtle neurodegenerative disorder. Postmortem and imaging studies have consistently found atrophy or neuron loss in the prefrontal cortices and hippocampi of depressed patients.1 Some studies suggest that antidepressants prevent the atrophy.2

Figure 2 Neural cell development may explain delayed antidepressant effect

In mouse brains, fluoxetine—but not placebo—increased the number of recently developed neuralcells (as shown by the injected marker 5-bromo-2’- deoxyuridine [BrdU]), but only after 28 days.

Source: Adapted from reference 4.

NEW VIEWS ON NEUROGENESIS

Until recently, the brain was believed incapable of generating nerve cells. We were thought to be born with our entire allotment of brain cells and we could only lose them because of age, trauma, or toxins. Within the past 5 years, however, it has become clear that human neuronal stem cells are capable of neurogenesis (Figure 1).3

Neurogenesis is an ongoing process in the brain, and depression may result from a relative decrease in new neuron development. Effective depression treatments may work by stimulating neurogenesis, and Santarelli et al4 offer compelling support for this idea.

A group of mice was treated orally with fluoxetine or placebo. Several from each group were sacrificed after 5 days and others at 28 days. Twenty-four hours before being sacrificed, each mouse was injected with 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU), which is incorporated into DNA and serves as a marker for recently developed nerve cells.

None of the mice at 5 days showed any change in BrdU-positive cells, and only the mice who received fluoxetine showed an increase in new cells after 28 days Figure 2. These results correlated with a greater willingness after 28 days by those mice on fluoxetine to venture into open, lighted areas—a behavioral change that was not seen at 5 days or in the placebo group.

This study shows that an antidepressant can increase development of new neurons and does so in a time course similar to the onset of efficacy seen in human clinical trials.

CHEMICAL OR CELLULAR?

One can speculate that insufficient neurogenesis is a possible cause of depression and that effective depression treatments may reverse that problem. Supporting this concept are other studies showing that lithium and electroconvulsive therapy—well-known treatments for depression—also increase neurogenesis.5

All this evidence makes depression look more like a cellular than a chemical imbalance.

1. Manji HK, Quiroz JA, Sporn J, et al. Enhancing neuronal plasticity and cellular resilience to develop novel, improved therapeutics for difficult-to-treat depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53:707-42.

2. Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1516-8.

3. Gage FH. Brain, repair yourself. Sci Am 2003;289:46-53.

4. Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science 2003;301:805-9.

5. Kempermann G, Kronenberg G. Depressed new neurons—adult hippocampal neurogenesis and a cellular plasticity hypothesis of major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:499-503.

1. Manji HK, Quiroz JA, Sporn J, et al. Enhancing neuronal plasticity and cellular resilience to develop novel, improved therapeutics for difficult-to-treat depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53:707-42.

2. Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1516-8.

3. Gage FH. Brain, repair yourself. Sci Am 2003;289:46-53.

4. Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science 2003;301:805-9.

5. Kempermann G, Kronenberg G. Depressed new neurons—adult hippocampal neurogenesis and a cellular plasticity hypothesis of major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:499-503.