User login

LAS VEGAS—Advances in autoimmune neurology, a rapidly evolving field, have the potential to prevent misdiagnosis of many disorders, from multiple sclerosis to neurodegenerative diseases. The key: increased detection of autoimmune and paraneoplastic neural antibodies, said Sean J. Pittock, MD, at the American Academy of Neurology’s Fall 2016 Conference. The importance of autoimmune neurology “cannot be overstated because these are reversible, treatable conditions,” Dr. Pittock said. “If you miss them, you have done your patients a disservice.”

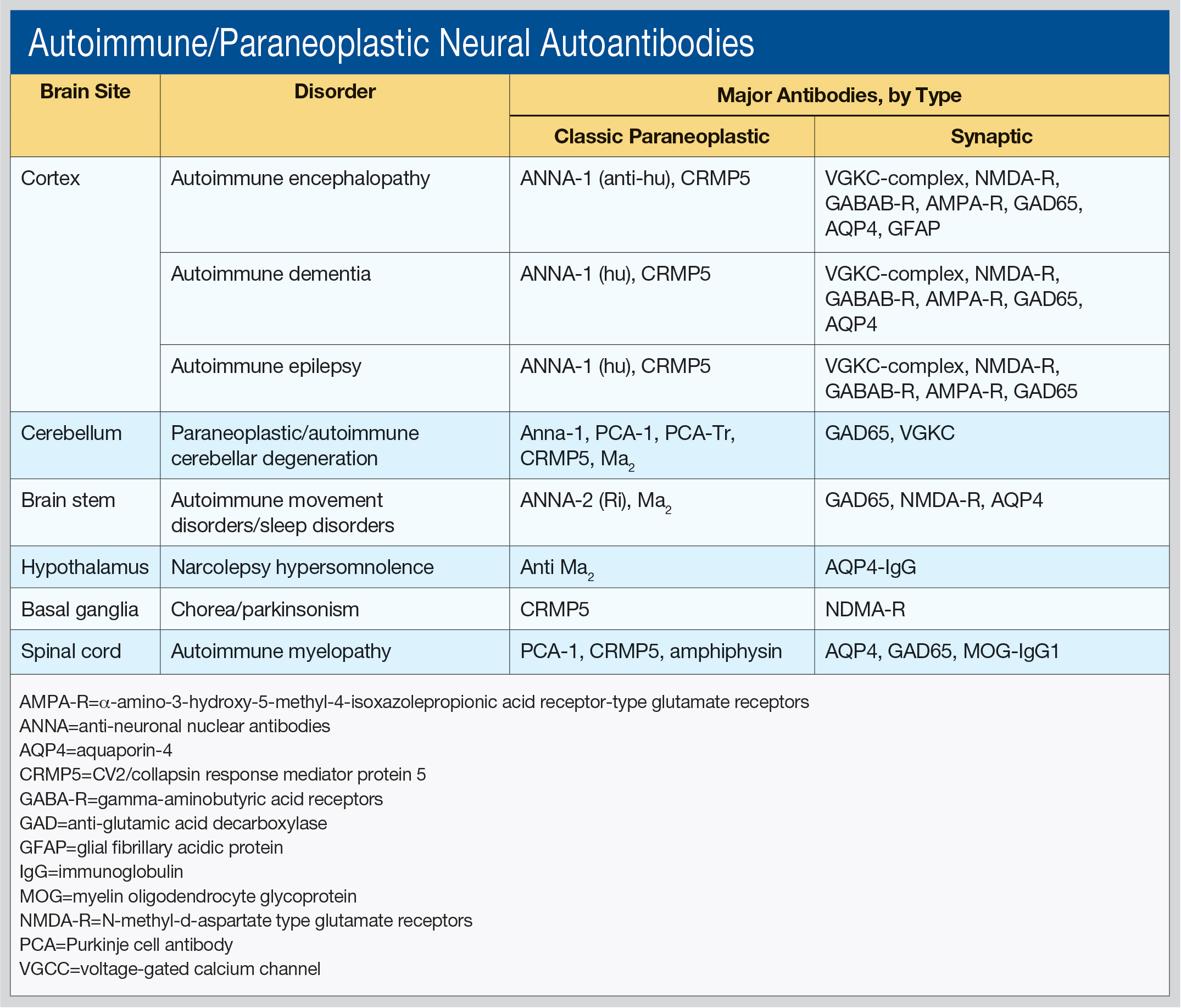

Dr. Pittock, Professor of Neurology, Director of the Neuroimmunology Laboratory, and Director of the Center for MS and Autoimmune Neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said he works primarily “in the field of discovering novel antibodies that make sense to the clinician.” He outlined these antibodies by brain site (cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and spinal cord), as well as associated disorders and type of antibodies (see table).

“Different antibodies tell you what cancers you should be looking for,” he said. The classic paraneoplastic antibodies have oncological associations with small cell and aerodigestive carcinomas, breast and gynecologic adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, and thymoma. The synaptic antibodies are associated with prostate, lung, thymic, and endometrial carcinomas, as well as with teratoma.

In his laboratory, Dr. Pittock uses a complex algorithm to test for 20 types of neural antibodies using diverse methodologies, from indirect immunofluorescence to cell-based and immunoprecipitation assays. Results are usually available within six to eight days. “We are moving towards a movement disorder evaluation, a CNS hyperexcitability evaluation, and a demyelinating disease evaluation,” he said.

“In paraneoplastic disorders, the tumors are often difficult to find,” Dr. Pittock said. “The immune system is having a dramatic impact on the tumor, and so these tumors are very small, so you may miss them.”

Dr. Pittock provided an overview of how clinicians might approach diagnosing autoimmune disorders. “For children, obviously, anaplastic diseases are rare, but if you have a patient with opsoclonus myoclonus, 50% of those children will have a cancer. For adolescents and young females, you always think about teratoma. If it is a young man, you really need to think about testicular tumors.”

The type of cancer defines what type of investigation is appropriate, he said. For example, due to low resolution, PET scans are not as useful for thymoma, teratoma, or testicular or gastrointestinal tumors. On the other hand, PET scans can help evaluate equivocal findings, such as pulmonary nodules or lymph nodes. With the exception of Medicare, however, PET scans are not generally covered by insurance. Medicare covers PET scanning under ICD-9 code V71.1, “observation for suspected malignant neoplasm,” and ICD-10, Z12, “encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm”; Z12.9, “site unspecified.”

At the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Pittock said they see five patients per week with NMDA-receptor encephalitis. To diagnose a possible autoimmune neurologic disorder, he asked that clinicians “please consider using the concept of immunotherapy as kind of a diagnostic test.” To do so, the patient should be treated acutely with IV methylprednisolone, IVIg, or plasma exchanges. If the patient improves, continue acute IV therapy and taper oral prednisone; other options include oral azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. If the patient does not improve, consider alternative acute therapy or no further therapy.

In one study that he and his colleagues conducted, 81% of patients who had failed antiepileptic drugs (AED) and were having daily seizures were treated with such a diagnostic test. Of these, 62% responded and 34% of patients became seizure-free. In contrast, Dr. Pittock said, patients treated with a third AED in a trial rarely experience meaningful improvement.

An autoimmune condition may also have a neuropsychiatric presentation. Dr. Pittock urged attendees to watch a recent film based on the 2013 book, “Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness,” by Susannah Cahalan, who went from psychosis to catatonia before a physician determined she had brain inflammation due to an autoimmune reaction.

“Many of these patients previously would have ended up in a psychiatric institution or in an ICU setting where, potentially, in the setting of intractable disease, they may have had their machine turned off, they may have died, when they have the potential to make a full recovery and, sometimes, spontaneously improve. The take-home message for this one is, if you want to investigate a patient with this, test spinal fluid.

“Autoimmune neurology is here to stay. It is a new field; it is very exciting; it has just been recognized by the American Academy of Neurology as having its own section,” Dr. Pittock said, and invited those interested to join.

Dr. Pittock has received research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

—Debra Hughes

Suggested Reading

Linnoila J, Pittock SJ. Autoantibody-associated central nervous system neurologic disorders. Semin Neurol. 2016;36(4):382-396.

Toledano M, Britton JW, McKeon A, et al. Utility of an immunotherapy trial in evaluating patients with presumed autoimmune epilepsy. Neurology. 2014;82(18):1578-1586.

LAS VEGAS—Advances in autoimmune neurology, a rapidly evolving field, have the potential to prevent misdiagnosis of many disorders, from multiple sclerosis to neurodegenerative diseases. The key: increased detection of autoimmune and paraneoplastic neural antibodies, said Sean J. Pittock, MD, at the American Academy of Neurology’s Fall 2016 Conference. The importance of autoimmune neurology “cannot be overstated because these are reversible, treatable conditions,” Dr. Pittock said. “If you miss them, you have done your patients a disservice.”

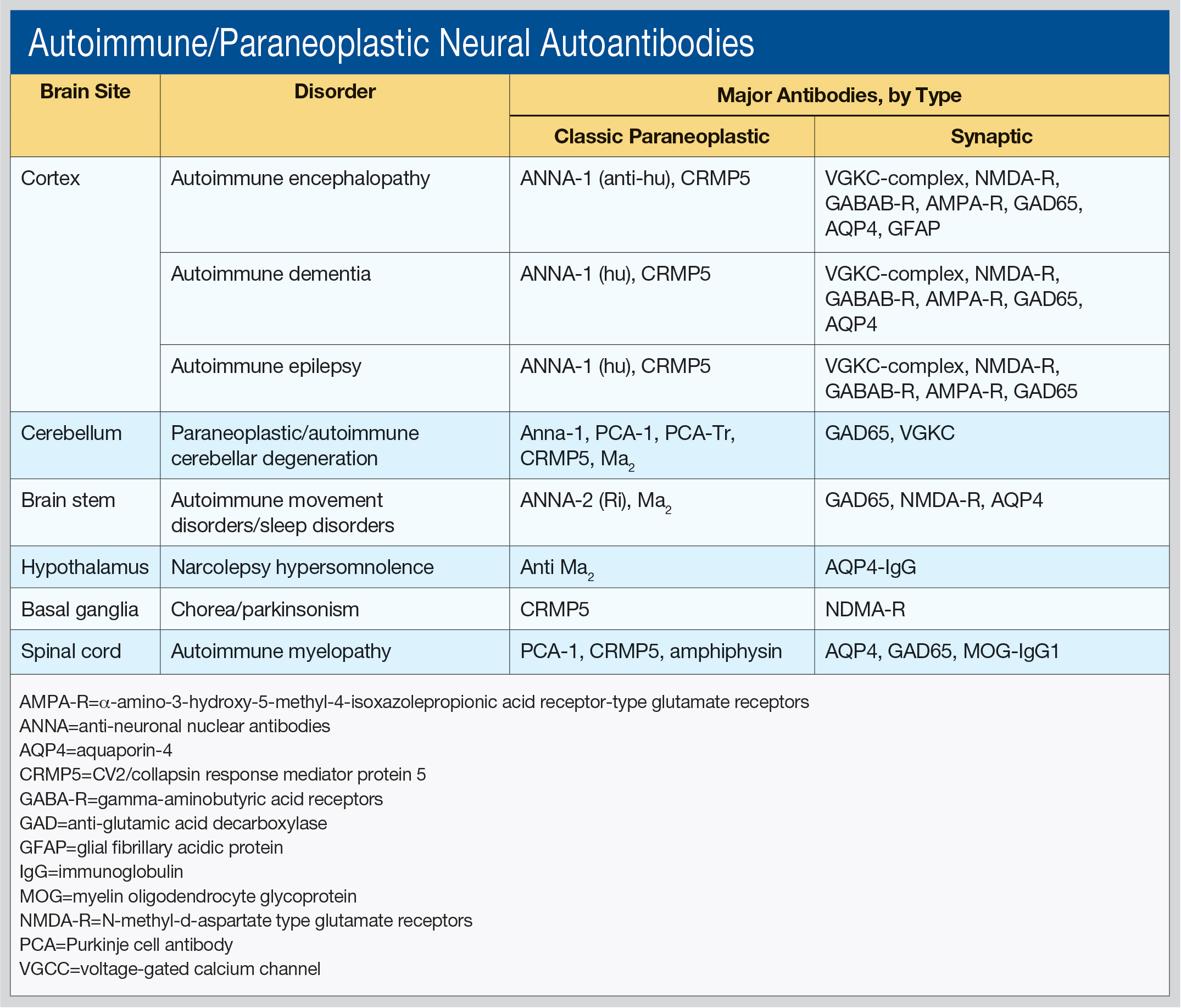

Dr. Pittock, Professor of Neurology, Director of the Neuroimmunology Laboratory, and Director of the Center for MS and Autoimmune Neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said he works primarily “in the field of discovering novel antibodies that make sense to the clinician.” He outlined these antibodies by brain site (cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and spinal cord), as well as associated disorders and type of antibodies (see table).

“Different antibodies tell you what cancers you should be looking for,” he said. The classic paraneoplastic antibodies have oncological associations with small cell and aerodigestive carcinomas, breast and gynecologic adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, and thymoma. The synaptic antibodies are associated with prostate, lung, thymic, and endometrial carcinomas, as well as with teratoma.

In his laboratory, Dr. Pittock uses a complex algorithm to test for 20 types of neural antibodies using diverse methodologies, from indirect immunofluorescence to cell-based and immunoprecipitation assays. Results are usually available within six to eight days. “We are moving towards a movement disorder evaluation, a CNS hyperexcitability evaluation, and a demyelinating disease evaluation,” he said.

“In paraneoplastic disorders, the tumors are often difficult to find,” Dr. Pittock said. “The immune system is having a dramatic impact on the tumor, and so these tumors are very small, so you may miss them.”

Dr. Pittock provided an overview of how clinicians might approach diagnosing autoimmune disorders. “For children, obviously, anaplastic diseases are rare, but if you have a patient with opsoclonus myoclonus, 50% of those children will have a cancer. For adolescents and young females, you always think about teratoma. If it is a young man, you really need to think about testicular tumors.”

The type of cancer defines what type of investigation is appropriate, he said. For example, due to low resolution, PET scans are not as useful for thymoma, teratoma, or testicular or gastrointestinal tumors. On the other hand, PET scans can help evaluate equivocal findings, such as pulmonary nodules or lymph nodes. With the exception of Medicare, however, PET scans are not generally covered by insurance. Medicare covers PET scanning under ICD-9 code V71.1, “observation for suspected malignant neoplasm,” and ICD-10, Z12, “encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm”; Z12.9, “site unspecified.”

At the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Pittock said they see five patients per week with NMDA-receptor encephalitis. To diagnose a possible autoimmune neurologic disorder, he asked that clinicians “please consider using the concept of immunotherapy as kind of a diagnostic test.” To do so, the patient should be treated acutely with IV methylprednisolone, IVIg, or plasma exchanges. If the patient improves, continue acute IV therapy and taper oral prednisone; other options include oral azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. If the patient does not improve, consider alternative acute therapy or no further therapy.

In one study that he and his colleagues conducted, 81% of patients who had failed antiepileptic drugs (AED) and were having daily seizures were treated with such a diagnostic test. Of these, 62% responded and 34% of patients became seizure-free. In contrast, Dr. Pittock said, patients treated with a third AED in a trial rarely experience meaningful improvement.

An autoimmune condition may also have a neuropsychiatric presentation. Dr. Pittock urged attendees to watch a recent film based on the 2013 book, “Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness,” by Susannah Cahalan, who went from psychosis to catatonia before a physician determined she had brain inflammation due to an autoimmune reaction.

“Many of these patients previously would have ended up in a psychiatric institution or in an ICU setting where, potentially, in the setting of intractable disease, they may have had their machine turned off, they may have died, when they have the potential to make a full recovery and, sometimes, spontaneously improve. The take-home message for this one is, if you want to investigate a patient with this, test spinal fluid.

“Autoimmune neurology is here to stay. It is a new field; it is very exciting; it has just been recognized by the American Academy of Neurology as having its own section,” Dr. Pittock said, and invited those interested to join.

Dr. Pittock has received research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

—Debra Hughes

Suggested Reading

Linnoila J, Pittock SJ. Autoantibody-associated central nervous system neurologic disorders. Semin Neurol. 2016;36(4):382-396.

Toledano M, Britton JW, McKeon A, et al. Utility of an immunotherapy trial in evaluating patients with presumed autoimmune epilepsy. Neurology. 2014;82(18):1578-1586.

LAS VEGAS—Advances in autoimmune neurology, a rapidly evolving field, have the potential to prevent misdiagnosis of many disorders, from multiple sclerosis to neurodegenerative diseases. The key: increased detection of autoimmune and paraneoplastic neural antibodies, said Sean J. Pittock, MD, at the American Academy of Neurology’s Fall 2016 Conference. The importance of autoimmune neurology “cannot be overstated because these are reversible, treatable conditions,” Dr. Pittock said. “If you miss them, you have done your patients a disservice.”

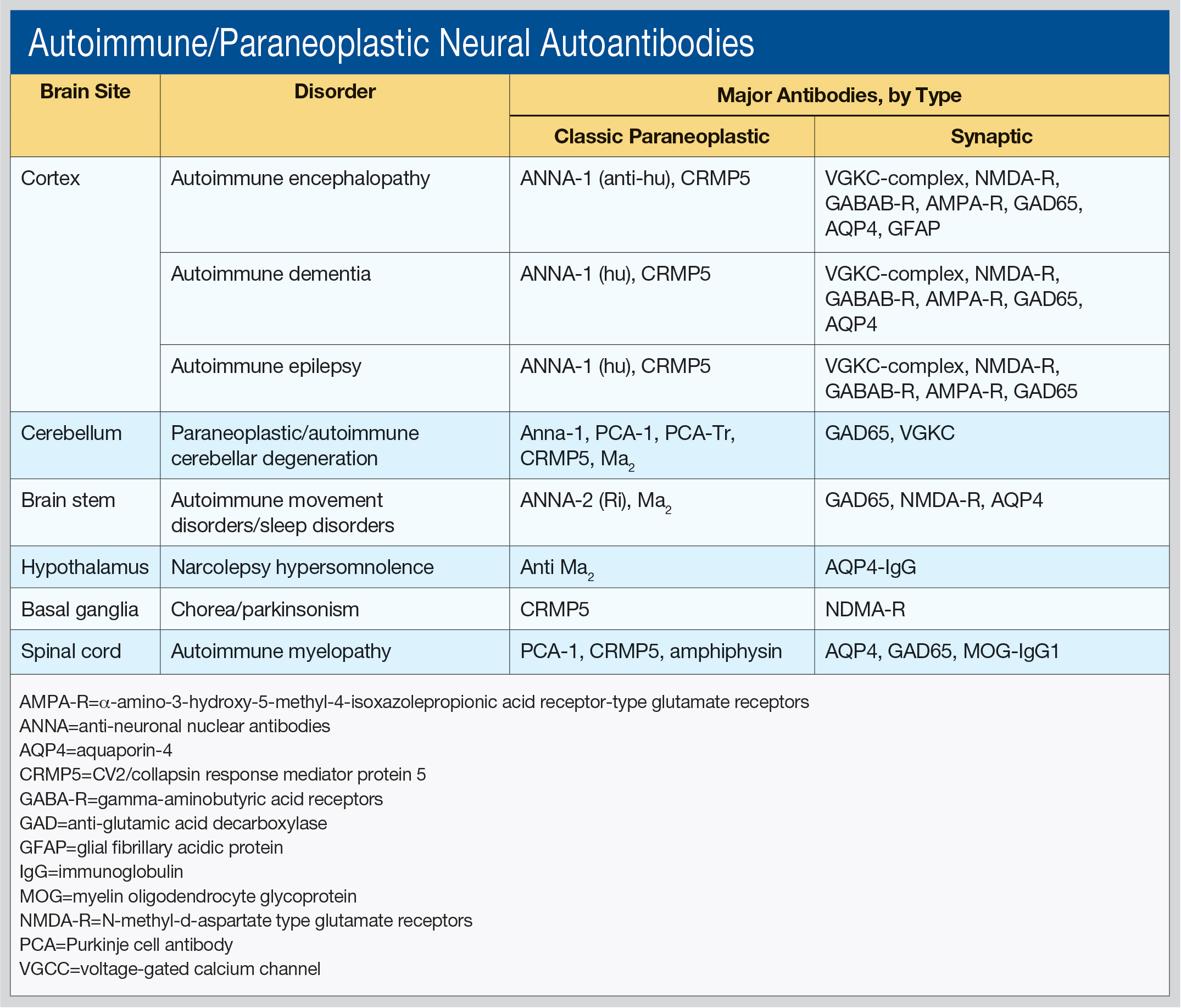

Dr. Pittock, Professor of Neurology, Director of the Neuroimmunology Laboratory, and Director of the Center for MS and Autoimmune Neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said he works primarily “in the field of discovering novel antibodies that make sense to the clinician.” He outlined these antibodies by brain site (cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and spinal cord), as well as associated disorders and type of antibodies (see table).

“Different antibodies tell you what cancers you should be looking for,” he said. The classic paraneoplastic antibodies have oncological associations with small cell and aerodigestive carcinomas, breast and gynecologic adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, and thymoma. The synaptic antibodies are associated with prostate, lung, thymic, and endometrial carcinomas, as well as with teratoma.

In his laboratory, Dr. Pittock uses a complex algorithm to test for 20 types of neural antibodies using diverse methodologies, from indirect immunofluorescence to cell-based and immunoprecipitation assays. Results are usually available within six to eight days. “We are moving towards a movement disorder evaluation, a CNS hyperexcitability evaluation, and a demyelinating disease evaluation,” he said.

“In paraneoplastic disorders, the tumors are often difficult to find,” Dr. Pittock said. “The immune system is having a dramatic impact on the tumor, and so these tumors are very small, so you may miss them.”

Dr. Pittock provided an overview of how clinicians might approach diagnosing autoimmune disorders. “For children, obviously, anaplastic diseases are rare, but if you have a patient with opsoclonus myoclonus, 50% of those children will have a cancer. For adolescents and young females, you always think about teratoma. If it is a young man, you really need to think about testicular tumors.”

The type of cancer defines what type of investigation is appropriate, he said. For example, due to low resolution, PET scans are not as useful for thymoma, teratoma, or testicular or gastrointestinal tumors. On the other hand, PET scans can help evaluate equivocal findings, such as pulmonary nodules or lymph nodes. With the exception of Medicare, however, PET scans are not generally covered by insurance. Medicare covers PET scanning under ICD-9 code V71.1, “observation for suspected malignant neoplasm,” and ICD-10, Z12, “encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm”; Z12.9, “site unspecified.”

At the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Pittock said they see five patients per week with NMDA-receptor encephalitis. To diagnose a possible autoimmune neurologic disorder, he asked that clinicians “please consider using the concept of immunotherapy as kind of a diagnostic test.” To do so, the patient should be treated acutely with IV methylprednisolone, IVIg, or plasma exchanges. If the patient improves, continue acute IV therapy and taper oral prednisone; other options include oral azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. If the patient does not improve, consider alternative acute therapy or no further therapy.

In one study that he and his colleagues conducted, 81% of patients who had failed antiepileptic drugs (AED) and were having daily seizures were treated with such a diagnostic test. Of these, 62% responded and 34% of patients became seizure-free. In contrast, Dr. Pittock said, patients treated with a third AED in a trial rarely experience meaningful improvement.

An autoimmune condition may also have a neuropsychiatric presentation. Dr. Pittock urged attendees to watch a recent film based on the 2013 book, “Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness,” by Susannah Cahalan, who went from psychosis to catatonia before a physician determined she had brain inflammation due to an autoimmune reaction.

“Many of these patients previously would have ended up in a psychiatric institution or in an ICU setting where, potentially, in the setting of intractable disease, they may have had their machine turned off, they may have died, when they have the potential to make a full recovery and, sometimes, spontaneously improve. The take-home message for this one is, if you want to investigate a patient with this, test spinal fluid.

“Autoimmune neurology is here to stay. It is a new field; it is very exciting; it has just been recognized by the American Academy of Neurology as having its own section,” Dr. Pittock said, and invited those interested to join.

Dr. Pittock has received research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

—Debra Hughes

Suggested Reading

Linnoila J, Pittock SJ. Autoantibody-associated central nervous system neurologic disorders. Semin Neurol. 2016;36(4):382-396.

Toledano M, Britton JW, McKeon A, et al. Utility of an immunotherapy trial in evaluating patients with presumed autoimmune epilepsy. Neurology. 2014;82(18):1578-1586.