User login

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD)—a childhood condition of extreme irritability, anger, and frequent, intense temper outbursts—has been a source of controversy among clinicians in the field of pediatric mental health. Before DSM-5 was published, the validity of DMDD had been questioned because DMDD had failed a field trial; agreement between clinicians on the diagnosis of DMDD was poor.1 Axelson2 and Birmaher et al3 examined its validity in their COBY (Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth) sample. They concluded that only 19% met the criteria for DMDD in 3 times of follow-up. Furthermore, most DMDD criteria overlap with those of other common pediatric psychiatric disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and pediatric bipolar disorder (BD). Because diagnosis of pediatric BD increased drastically from 2.9% to 15.1% between 1990 and 2000,4 it was believed that introducing DMDD as a diagnosis might lessen the overdiagnosis of pediatric BD by identifying children with chronic irritability and temper tantrums who previously would have been diagnosed with BD.

It is important to recognize that in pediatric patients, mood disorders present differently than they do in adults.5 In children/adolescents, mood disorders are less likely to present as distinct episodes (narrow band), but more likely to present as chronic, broad symptoms. Also, irritability is a common presentation in many pediatric psychiatric disorders, such as ODD, BD (irritability without elation),6 and depression. Thus, for many clinicians, determining the correct mood disorder diagnosis in pediatric patients can be challenging.

This article describes the diagnosis of DMDD, and how its presentation is similar to—and different from—those of other common pediatric psychiatric disorders.

_

The origin of DMDD

Many researchers have investigated the broadband phenotypical presentation of pediatric mood disorders, which have been mostly diagnosed in the psychiatric community as pediatric BD. Leibenluft7 identified a subtype of mood disorder that they termed “severe mood dysregulation” (SMD). Compared with the narrow-band, clearly episodic BD, SMD has a different trajectory, outcome, and findings on brain imaging. SMD is characterized by chronic irritability with abnormal mood (anger or sadness) at least half of the day on most days, with 3 hyperarousal symptoms, including pressured speech, racing thoughts or flight of ideas, intrusiveness, distractibility, insomnia, and agitation.8 Eventually, SMD became the foundation of the development of DMDD.

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for DMDD include severe recurrent temper outbursts that are out of proportion to the situation, inconsistent with developmental level, and occurring on average ≥3 times per week, plus persistently irritable or angry mood for most of the day nearly every day.9 Additional criteria include the presence of symptoms for at least 12 months (without a symptom-free period of at least 3 consecutive months) in ≥2 settings (at home, at school, or with peers) with onset before age 10. The course of DMDD typically is chronic with accompanying severe temperament. The estimated 6-month to 1-year prevalence is 2% to 5%; the diagnosis is more common among males and school-age children than it is in females and adolescents.9,10

_

DMDD or bipolar disorder?

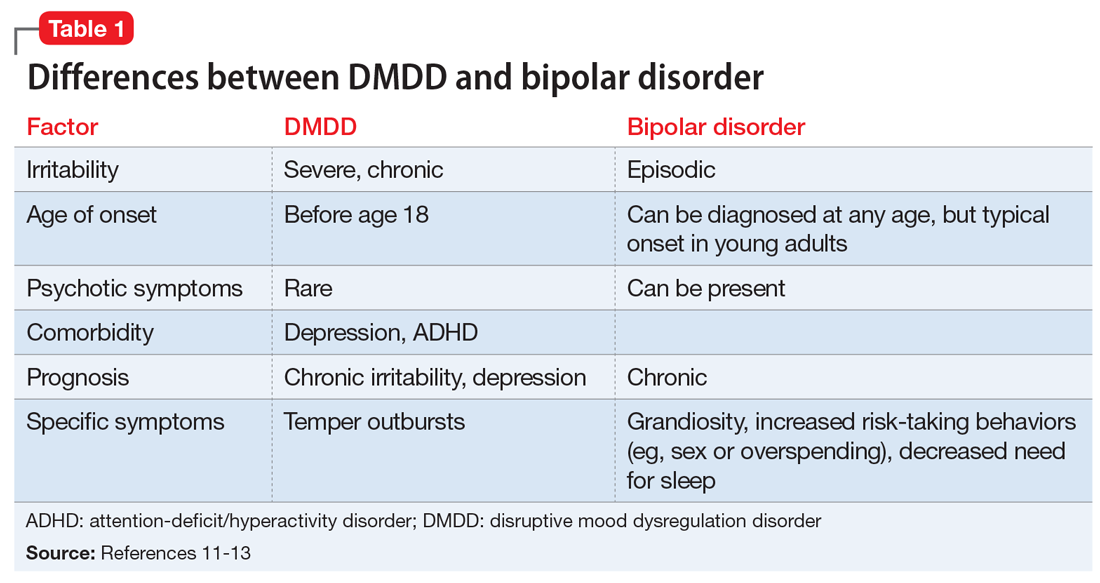

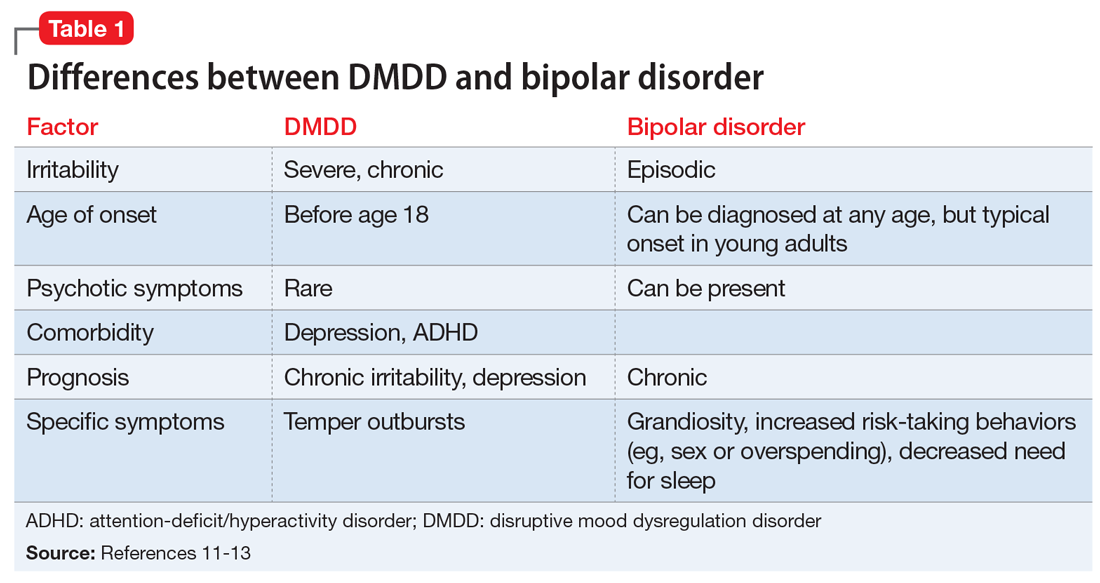

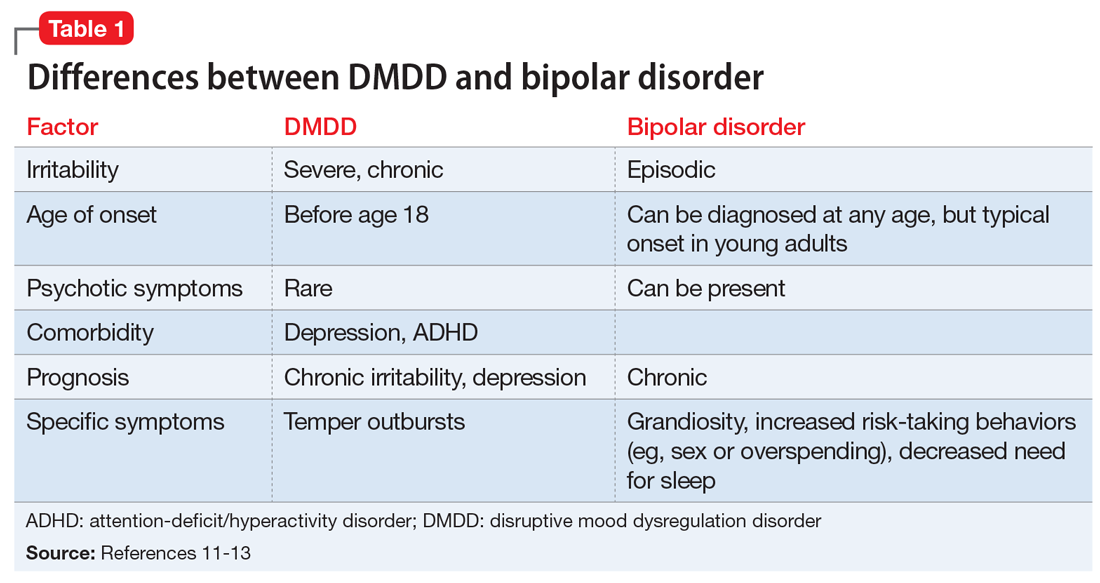

A patient cannot be dually diagnosed with both disorders. If a patient exhibits a manic episode for more than 1 day, that would null and void the DMDD diagnosis. However, in a study to evaluate BD in pediatric patients, researchers divided BD symptoms into BD-specific categories (elevated mood, grandiosity, and increased goal-directed activity) and nonspecific symptoms such as irritability and talkativeness, distractibility, and flight of ideas or racing thoughts. They found that in the absence of specific symptoms, a diagnosis of BD is unlikely to be the correct diagnosis.11 Hence, as a nonspecific symptom, chronic irritability should be attributed to the symptom count for DMDD, rather than BD. Most epidemiologic studies have concluded that depression and anxiety, and not irritability, are typically the preceeding presentations prior to the development of BD in young adults.12 Chronic irritability, however, predicts major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders in later adolescence and one’s early twenties.13 Furthermore, BD commonly presents with infrequent and discrete episodes and a later age of onset, while DMDD presents with chronic and frequent, severe temper outbursts. Some differences between DMDD and BD are illustrated in Table 1.11-13

Continue to: CASE 1

CASE 1

Irritable and taking risks

Ms. N, age 16, is brought to the outpatient psychiatry clinic by her parents for evaluation of mood symptoms, including irritability. Her mother claims her daughter was an introverted, anxious, shy child, but by the beginning of middle school, she began to feel irritable and frequently stayed up at night with little sleep. In high school, Ms. N had displayed several episodes of risk-taking behaviors, including taking her father’s vehicle for a drive despite not having a driver’s permit, running away for 2 days, and having unprotected sex.

During her assessment, Ms. N is pleasant and claims she usually has a great mood. She fought with her mother several times this year, which led her to run away. Her parents had divorced when Ms. N was 5 years old and have shared custody. Ms. N is doing well in school despite her parents’ concerns.

Diagnosis. The most likely diagnosis is emerging BD. Notice that Ms. N may have had anxiety symptoms before she developed irritability. She had a relatively late onset of symptoms that were episodic in nature, which further supports a diagnosis of BD.

_

>

DMDD or oppositional defiant disorder?

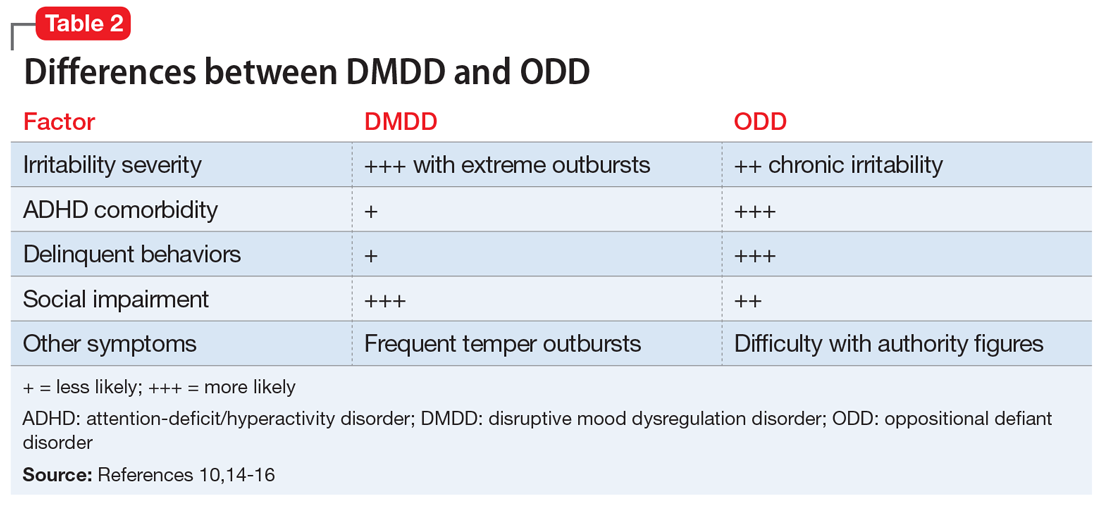

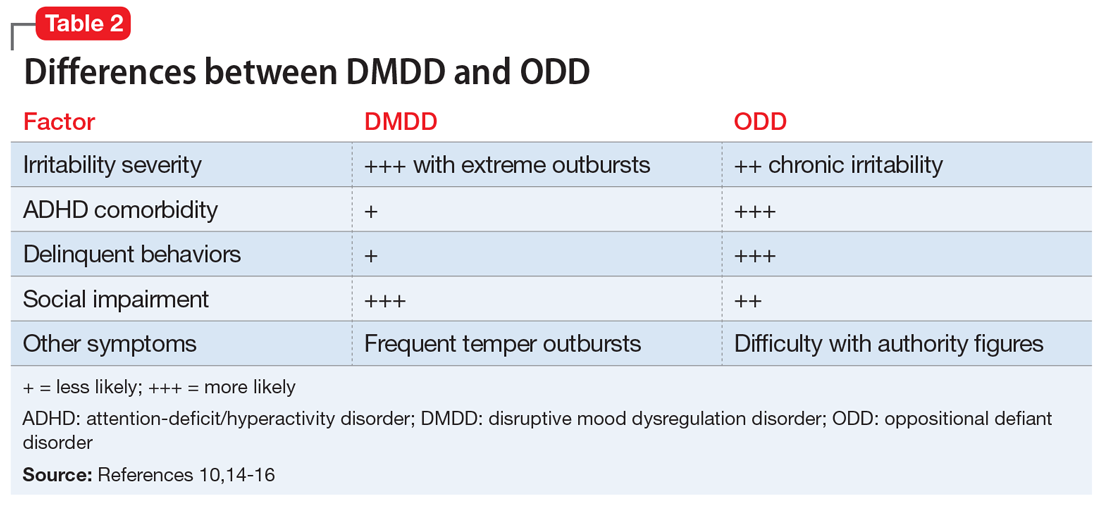

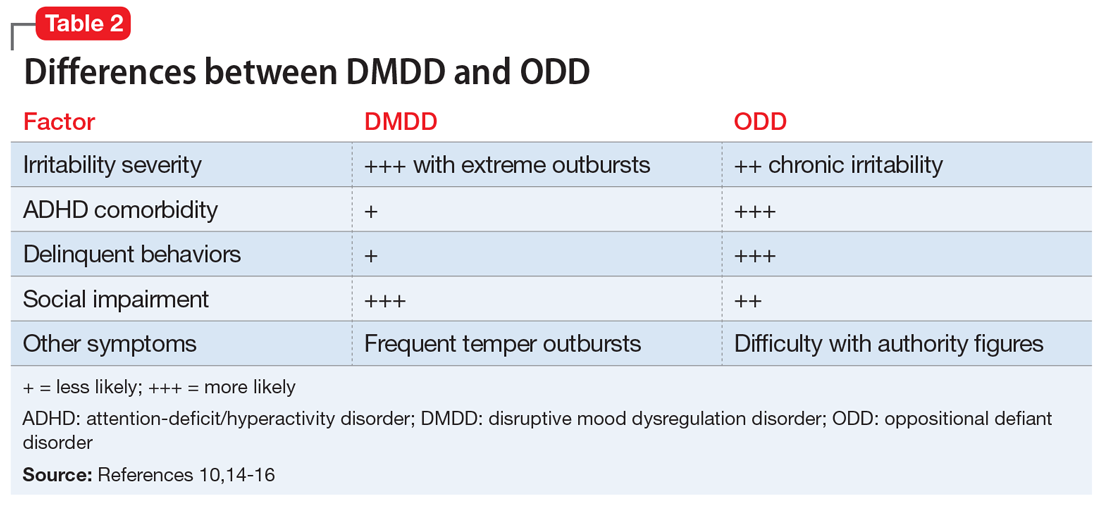

DMDD and ODD cannot be dually diagnosed. However, if a patient meets the criteria for both DMDD and ODD, only the DMDD diagnosis should be considered. One of many issues of DMDD is its similarity to ODD. In fact, more than 70% of patients with DMDD also meet the diagnostic criteria for ODD.10,14 Some researchers have conceptualized DMDD as a severe form of ODD. However, there are a few differences that clinicians can use to distinguish the 2 disorders.

Compared with patients with ODD, those with DMDD more frequently experience severe irritability.15 Patients with ODD may present with delinquent behaviors and trouble with authority figures. Moreover, comorbidity with ADHD is twice as common in ODD; more than 65% of patients with ADHD have ODD vs 30% who have DMDD.10,16 Finally, in general, children with DMDD have more social impairments compared with those with ODD. Differences between DMDD and BD are illustrated in Table 2.10,14-16

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2

Angry and defiant

Mr. R, age 14, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his parents after becoming very aggressive with them. He punched a wall and vandalized his room after his parents grounded him because of his previous defiant behavior. He had been suspended from school that day for disrespecting his teacher after he was caught fighting another student.

His parents describe Mr. R as a strong-willed, stubborn child. He has difficulty with rules and refuses to follow them. He is grouchy and irritable around adults, including the ED staff. Mr. R enjoys being with his friends and playing video games. He had been diagnosed with ADHD when he was in kindergarten, when his teacher noticed he had a poor attention span and could not sit still. According to his parents, Mr. R has “blown up” a few times before, smashing items in his room and shouting obscenities. Mr. R’s parents noticed that he is more defiant in concurrence with discontinuing his ADHD stimulant medication.

Diagnosis. The most likely diagnosis for Mr. R is ODD. Notice the comorbidity of ADHD, which is more commonly associated with ODD. The frequency and severity of his outbursts and irritability symptoms were lower than that typically associated with DMDD.

_

Treatment strategies for DMDD

Management of DMDD should focus on helping children and adolescents improve their emotional dysregulation.

Clinicians should always consider behavioral therapy as a first-line intervention. The behavioral planning team may include (but is not limited to) a behavior specialist, child psychiatrist, psychologist, therapist, skills trainer, teachers, and the caregiver(s). The plan should be implemented across all settings, including home and school. Furthermore, social skills training is necessary for many children with DMDD, who may require intensive behavioral modification planning. Comorbidity with ADHD should be addressed with a combination of behavioral planning and stimulant medications.17 If available, parent training and parent-child interactive therapy can help to improve defiant behavior.

Pharmacotherapy

Currently, no medications are FDA-approved for treating DMDD. Most pharmacologic trials that included patients with DMDD focused on managing chronic irritability and/or stabilizing comorbid disorders (ie, ADHD, depression, and anxiety).

Continue to: Stimulants

Stimulants. Previous trials examined the benefit of CNS stimulant medications, alone or in conjunction with behavioral therapy, in treating DMDD and comorbid ADHD. Methylphenidate results in a significant reduction in aggression18 with a dosing recommendation range from 1 to 1.2 mg/kg/d. CNS stimulants should be considered as first-line pharmacotherapy for DMDD, especially for patients with comorbid ADHD.

Anticonvulsants. Divalproex sodium is superior to placebo in treating aggression in children and adolescents.19 Trials found that divalproex sodium reduces irritability and aggression whether it is prescribed as monotherapy or combined with stimulant medications.19

Lithium is one of the main treatment options for mania in BD. The benefits of lithium for controlling aggression in DMDD are still under investigation. Earlier studies found that lithium significantly improves aggressive behavior in hospitalized pediatric with conduct disorder.20,21 However, a later study that evaluated lithium vs placebo for children with SMD (which arguably is phenotypically related to the DMDD) found there were no significant differences in improvement of irritability symptoms between groups.22 More research is needed to determine if lithium may play a role in treating patients with DMDD.

Antipsychotics. Aripiprazole and risperidone are FDA-approved for treating irritability in autism. A 2017 meta-analysis found both medications were effective in controlling irritability and aggression in other diagnoses as well.23 Other antipsychotic medications did not show sufficient benefits in treating irritability.23 When considering antipsychotics, clinicians should weigh the risks of metabolic adverse effects and follow practice guidelines.

Antidepressants. A systematic review did not find that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors effectively reduce irritability.24 However, in most of the studies evaluated, irritability was not the primary outcome measure.24

Other medications. Alpha-2 agonists (guanfacine, clonidine), and atomoxetine may help irritability indirectly by improving ADHD symptoms.25

Bottom Line

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), bipolar disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder have similar presentations and diagnostic criteria. The frequency and severity of irritability can be a distinguishing factor. Behavioral therapy is a first-line treatment. No medications are FDA-approved for treating DMDD, but pharmacotherapy may help reduce irritability and aggression.

Related Resources

- Rao U. DSM-5: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;11:119-123.

- Roy AK, Lopes V, Klein RG. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: a new diagnostic approach to chronic irritability in youth. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(9):918-924.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Clonidine • Catapres

Divalproex sodium • Depakote, Depakote ER

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE, et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(1):59-70.

2. Axelson D. Taking disruptive mood dysregulation disorder out for a test drive. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):136-139.

3. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, et al. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):795-804.

4. Case BG, Olfson M, Marcus SC, et al. Trends in the inpatient mental health treatment of children and adolescents in US community hospitals between 1990 and 2000. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):89-96.

5. Pliszka S; AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):894-921.

6. Hunt J, Birmaher B, Leonard H, et al. Irritability without elation in a large bipolar youth sample: frequency and clinical description. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(7):730-739.

7. Leibenluft E. Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(2):129-142.

8. Rich BA, Carver FW, Holroyd T, et al. Different neural pathways to negative affect in youth with pediatric bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(10):1283-1294.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of DSM-5 proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):173-179.

11. Elmaadawi AZ, Jensen PS, Arnold LE, et al. Risk for emerging bipolar disorder, variants, and symptoms in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, now grown up. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(4):412-424.

12. Duffy A. The early natural history of bipolar disorder: what we have learned from longitudinal high-risk research. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(8):477-485.

13. Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine DS, et al. Adult outcomes of youth irritability: a 20-year prospective community-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1048-1054.

14. Mayes SD, Waxmonsky JD, Calhoun SL, et al. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder symptoms and association with oppositional defiant and other disorders in a general population child sample. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(2):101-106.

15. Stringaris A, Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, et al. Practitioner review: definition, recognition, and treatment challenges of irritability in young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(7):721-739.

16. Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):57-87.

17. Fernandez de la Cruz L, Simonoff E, McGough JJ, et al. Treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and irritability: results from the multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD (MTA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(1):62-70.

18. Pappadopulos E, Woolston S, Chait A, et al. Pharmacotherapy of aggression in children and adolescents: efficacy and effect size. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(1):27-39.

19. Donovan SJ, Stewart JW, Nunes EV, et al. Divalproex treatment for youth with explosive temper and mood lability: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):818-820.

20. Campbell M, Adams PB, Small AM, et al. Lithium in hospitalized aggressive children with conduct disorder: a double-blind and placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(4):445-453.

21. Malone RP, Delaney MA, Luebbert JF, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lithium in hospitalized aggressive children and adolescents with conduct disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):649-654.

22. Dickstein DP, Towbin KE, Van Der Veen JW, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of lithium in youths with severe mood dysregulation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):61-73.

23. van Schalkwyk GI, Lewis AS, Beyer C, et al. Efficacy of antipsychotics for irritability and aggression in children: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(10):1045-1053.

24. Kim S, Boylan K. Effectiveness of antidepressant medications for symptoms of irritability and disruptive behaviors in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(8):694-704.

25. Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, et al. A placebo-controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1067-1074.

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD)—a childhood condition of extreme irritability, anger, and frequent, intense temper outbursts—has been a source of controversy among clinicians in the field of pediatric mental health. Before DSM-5 was published, the validity of DMDD had been questioned because DMDD had failed a field trial; agreement between clinicians on the diagnosis of DMDD was poor.1 Axelson2 and Birmaher et al3 examined its validity in their COBY (Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth) sample. They concluded that only 19% met the criteria for DMDD in 3 times of follow-up. Furthermore, most DMDD criteria overlap with those of other common pediatric psychiatric disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and pediatric bipolar disorder (BD). Because diagnosis of pediatric BD increased drastically from 2.9% to 15.1% between 1990 and 2000,4 it was believed that introducing DMDD as a diagnosis might lessen the overdiagnosis of pediatric BD by identifying children with chronic irritability and temper tantrums who previously would have been diagnosed with BD.

It is important to recognize that in pediatric patients, mood disorders present differently than they do in adults.5 In children/adolescents, mood disorders are less likely to present as distinct episodes (narrow band), but more likely to present as chronic, broad symptoms. Also, irritability is a common presentation in many pediatric psychiatric disorders, such as ODD, BD (irritability without elation),6 and depression. Thus, for many clinicians, determining the correct mood disorder diagnosis in pediatric patients can be challenging.

This article describes the diagnosis of DMDD, and how its presentation is similar to—and different from—those of other common pediatric psychiatric disorders.

_

The origin of DMDD

Many researchers have investigated the broadband phenotypical presentation of pediatric mood disorders, which have been mostly diagnosed in the psychiatric community as pediatric BD. Leibenluft7 identified a subtype of mood disorder that they termed “severe mood dysregulation” (SMD). Compared with the narrow-band, clearly episodic BD, SMD has a different trajectory, outcome, and findings on brain imaging. SMD is characterized by chronic irritability with abnormal mood (anger or sadness) at least half of the day on most days, with 3 hyperarousal symptoms, including pressured speech, racing thoughts or flight of ideas, intrusiveness, distractibility, insomnia, and agitation.8 Eventually, SMD became the foundation of the development of DMDD.

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for DMDD include severe recurrent temper outbursts that are out of proportion to the situation, inconsistent with developmental level, and occurring on average ≥3 times per week, plus persistently irritable or angry mood for most of the day nearly every day.9 Additional criteria include the presence of symptoms for at least 12 months (without a symptom-free period of at least 3 consecutive months) in ≥2 settings (at home, at school, or with peers) with onset before age 10. The course of DMDD typically is chronic with accompanying severe temperament. The estimated 6-month to 1-year prevalence is 2% to 5%; the diagnosis is more common among males and school-age children than it is in females and adolescents.9,10

_

DMDD or bipolar disorder?

A patient cannot be dually diagnosed with both disorders. If a patient exhibits a manic episode for more than 1 day, that would null and void the DMDD diagnosis. However, in a study to evaluate BD in pediatric patients, researchers divided BD symptoms into BD-specific categories (elevated mood, grandiosity, and increased goal-directed activity) and nonspecific symptoms such as irritability and talkativeness, distractibility, and flight of ideas or racing thoughts. They found that in the absence of specific symptoms, a diagnosis of BD is unlikely to be the correct diagnosis.11 Hence, as a nonspecific symptom, chronic irritability should be attributed to the symptom count for DMDD, rather than BD. Most epidemiologic studies have concluded that depression and anxiety, and not irritability, are typically the preceeding presentations prior to the development of BD in young adults.12 Chronic irritability, however, predicts major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders in later adolescence and one’s early twenties.13 Furthermore, BD commonly presents with infrequent and discrete episodes and a later age of onset, while DMDD presents with chronic and frequent, severe temper outbursts. Some differences between DMDD and BD are illustrated in Table 1.11-13

Continue to: CASE 1

CASE 1

Irritable and taking risks

Ms. N, age 16, is brought to the outpatient psychiatry clinic by her parents for evaluation of mood symptoms, including irritability. Her mother claims her daughter was an introverted, anxious, shy child, but by the beginning of middle school, she began to feel irritable and frequently stayed up at night with little sleep. In high school, Ms. N had displayed several episodes of risk-taking behaviors, including taking her father’s vehicle for a drive despite not having a driver’s permit, running away for 2 days, and having unprotected sex.

During her assessment, Ms. N is pleasant and claims she usually has a great mood. She fought with her mother several times this year, which led her to run away. Her parents had divorced when Ms. N was 5 years old and have shared custody. Ms. N is doing well in school despite her parents’ concerns.

Diagnosis. The most likely diagnosis is emerging BD. Notice that Ms. N may have had anxiety symptoms before she developed irritability. She had a relatively late onset of symptoms that were episodic in nature, which further supports a diagnosis of BD.

_

>

DMDD or oppositional defiant disorder?

DMDD and ODD cannot be dually diagnosed. However, if a patient meets the criteria for both DMDD and ODD, only the DMDD diagnosis should be considered. One of many issues of DMDD is its similarity to ODD. In fact, more than 70% of patients with DMDD also meet the diagnostic criteria for ODD.10,14 Some researchers have conceptualized DMDD as a severe form of ODD. However, there are a few differences that clinicians can use to distinguish the 2 disorders.

Compared with patients with ODD, those with DMDD more frequently experience severe irritability.15 Patients with ODD may present with delinquent behaviors and trouble with authority figures. Moreover, comorbidity with ADHD is twice as common in ODD; more than 65% of patients with ADHD have ODD vs 30% who have DMDD.10,16 Finally, in general, children with DMDD have more social impairments compared with those with ODD. Differences between DMDD and BD are illustrated in Table 2.10,14-16

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2

Angry and defiant

Mr. R, age 14, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his parents after becoming very aggressive with them. He punched a wall and vandalized his room after his parents grounded him because of his previous defiant behavior. He had been suspended from school that day for disrespecting his teacher after he was caught fighting another student.

His parents describe Mr. R as a strong-willed, stubborn child. He has difficulty with rules and refuses to follow them. He is grouchy and irritable around adults, including the ED staff. Mr. R enjoys being with his friends and playing video games. He had been diagnosed with ADHD when he was in kindergarten, when his teacher noticed he had a poor attention span and could not sit still. According to his parents, Mr. R has “blown up” a few times before, smashing items in his room and shouting obscenities. Mr. R’s parents noticed that he is more defiant in concurrence with discontinuing his ADHD stimulant medication.

Diagnosis. The most likely diagnosis for Mr. R is ODD. Notice the comorbidity of ADHD, which is more commonly associated with ODD. The frequency and severity of his outbursts and irritability symptoms were lower than that typically associated with DMDD.

_

Treatment strategies for DMDD

Management of DMDD should focus on helping children and adolescents improve their emotional dysregulation.

Clinicians should always consider behavioral therapy as a first-line intervention. The behavioral planning team may include (but is not limited to) a behavior specialist, child psychiatrist, psychologist, therapist, skills trainer, teachers, and the caregiver(s). The plan should be implemented across all settings, including home and school. Furthermore, social skills training is necessary for many children with DMDD, who may require intensive behavioral modification planning. Comorbidity with ADHD should be addressed with a combination of behavioral planning and stimulant medications.17 If available, parent training and parent-child interactive therapy can help to improve defiant behavior.

Pharmacotherapy

Currently, no medications are FDA-approved for treating DMDD. Most pharmacologic trials that included patients with DMDD focused on managing chronic irritability and/or stabilizing comorbid disorders (ie, ADHD, depression, and anxiety).

Continue to: Stimulants

Stimulants. Previous trials examined the benefit of CNS stimulant medications, alone or in conjunction with behavioral therapy, in treating DMDD and comorbid ADHD. Methylphenidate results in a significant reduction in aggression18 with a dosing recommendation range from 1 to 1.2 mg/kg/d. CNS stimulants should be considered as first-line pharmacotherapy for DMDD, especially for patients with comorbid ADHD.

Anticonvulsants. Divalproex sodium is superior to placebo in treating aggression in children and adolescents.19 Trials found that divalproex sodium reduces irritability and aggression whether it is prescribed as monotherapy or combined with stimulant medications.19

Lithium is one of the main treatment options for mania in BD. The benefits of lithium for controlling aggression in DMDD are still under investigation. Earlier studies found that lithium significantly improves aggressive behavior in hospitalized pediatric with conduct disorder.20,21 However, a later study that evaluated lithium vs placebo for children with SMD (which arguably is phenotypically related to the DMDD) found there were no significant differences in improvement of irritability symptoms between groups.22 More research is needed to determine if lithium may play a role in treating patients with DMDD.

Antipsychotics. Aripiprazole and risperidone are FDA-approved for treating irritability in autism. A 2017 meta-analysis found both medications were effective in controlling irritability and aggression in other diagnoses as well.23 Other antipsychotic medications did not show sufficient benefits in treating irritability.23 When considering antipsychotics, clinicians should weigh the risks of metabolic adverse effects and follow practice guidelines.

Antidepressants. A systematic review did not find that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors effectively reduce irritability.24 However, in most of the studies evaluated, irritability was not the primary outcome measure.24

Other medications. Alpha-2 agonists (guanfacine, clonidine), and atomoxetine may help irritability indirectly by improving ADHD symptoms.25

Bottom Line

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), bipolar disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder have similar presentations and diagnostic criteria. The frequency and severity of irritability can be a distinguishing factor. Behavioral therapy is a first-line treatment. No medications are FDA-approved for treating DMDD, but pharmacotherapy may help reduce irritability and aggression.

Related Resources

- Rao U. DSM-5: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;11:119-123.

- Roy AK, Lopes V, Klein RG. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: a new diagnostic approach to chronic irritability in youth. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(9):918-924.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Clonidine • Catapres

Divalproex sodium • Depakote, Depakote ER

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD)—a childhood condition of extreme irritability, anger, and frequent, intense temper outbursts—has been a source of controversy among clinicians in the field of pediatric mental health. Before DSM-5 was published, the validity of DMDD had been questioned because DMDD had failed a field trial; agreement between clinicians on the diagnosis of DMDD was poor.1 Axelson2 and Birmaher et al3 examined its validity in their COBY (Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth) sample. They concluded that only 19% met the criteria for DMDD in 3 times of follow-up. Furthermore, most DMDD criteria overlap with those of other common pediatric psychiatric disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and pediatric bipolar disorder (BD). Because diagnosis of pediatric BD increased drastically from 2.9% to 15.1% between 1990 and 2000,4 it was believed that introducing DMDD as a diagnosis might lessen the overdiagnosis of pediatric BD by identifying children with chronic irritability and temper tantrums who previously would have been diagnosed with BD.

It is important to recognize that in pediatric patients, mood disorders present differently than they do in adults.5 In children/adolescents, mood disorders are less likely to present as distinct episodes (narrow band), but more likely to present as chronic, broad symptoms. Also, irritability is a common presentation in many pediatric psychiatric disorders, such as ODD, BD (irritability without elation),6 and depression. Thus, for many clinicians, determining the correct mood disorder diagnosis in pediatric patients can be challenging.

This article describes the diagnosis of DMDD, and how its presentation is similar to—and different from—those of other common pediatric psychiatric disorders.

_

The origin of DMDD

Many researchers have investigated the broadband phenotypical presentation of pediatric mood disorders, which have been mostly diagnosed in the psychiatric community as pediatric BD. Leibenluft7 identified a subtype of mood disorder that they termed “severe mood dysregulation” (SMD). Compared with the narrow-band, clearly episodic BD, SMD has a different trajectory, outcome, and findings on brain imaging. SMD is characterized by chronic irritability with abnormal mood (anger or sadness) at least half of the day on most days, with 3 hyperarousal symptoms, including pressured speech, racing thoughts or flight of ideas, intrusiveness, distractibility, insomnia, and agitation.8 Eventually, SMD became the foundation of the development of DMDD.

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for DMDD include severe recurrent temper outbursts that are out of proportion to the situation, inconsistent with developmental level, and occurring on average ≥3 times per week, plus persistently irritable or angry mood for most of the day nearly every day.9 Additional criteria include the presence of symptoms for at least 12 months (without a symptom-free period of at least 3 consecutive months) in ≥2 settings (at home, at school, or with peers) with onset before age 10. The course of DMDD typically is chronic with accompanying severe temperament. The estimated 6-month to 1-year prevalence is 2% to 5%; the diagnosis is more common among males and school-age children than it is in females and adolescents.9,10

_

DMDD or bipolar disorder?

A patient cannot be dually diagnosed with both disorders. If a patient exhibits a manic episode for more than 1 day, that would null and void the DMDD diagnosis. However, in a study to evaluate BD in pediatric patients, researchers divided BD symptoms into BD-specific categories (elevated mood, grandiosity, and increased goal-directed activity) and nonspecific symptoms such as irritability and talkativeness, distractibility, and flight of ideas or racing thoughts. They found that in the absence of specific symptoms, a diagnosis of BD is unlikely to be the correct diagnosis.11 Hence, as a nonspecific symptom, chronic irritability should be attributed to the symptom count for DMDD, rather than BD. Most epidemiologic studies have concluded that depression and anxiety, and not irritability, are typically the preceeding presentations prior to the development of BD in young adults.12 Chronic irritability, however, predicts major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders in later adolescence and one’s early twenties.13 Furthermore, BD commonly presents with infrequent and discrete episodes and a later age of onset, while DMDD presents with chronic and frequent, severe temper outbursts. Some differences between DMDD and BD are illustrated in Table 1.11-13

Continue to: CASE 1

CASE 1

Irritable and taking risks

Ms. N, age 16, is brought to the outpatient psychiatry clinic by her parents for evaluation of mood symptoms, including irritability. Her mother claims her daughter was an introverted, anxious, shy child, but by the beginning of middle school, she began to feel irritable and frequently stayed up at night with little sleep. In high school, Ms. N had displayed several episodes of risk-taking behaviors, including taking her father’s vehicle for a drive despite not having a driver’s permit, running away for 2 days, and having unprotected sex.

During her assessment, Ms. N is pleasant and claims she usually has a great mood. She fought with her mother several times this year, which led her to run away. Her parents had divorced when Ms. N was 5 years old and have shared custody. Ms. N is doing well in school despite her parents’ concerns.

Diagnosis. The most likely diagnosis is emerging BD. Notice that Ms. N may have had anxiety symptoms before she developed irritability. She had a relatively late onset of symptoms that were episodic in nature, which further supports a diagnosis of BD.

_

>

DMDD or oppositional defiant disorder?

DMDD and ODD cannot be dually diagnosed. However, if a patient meets the criteria for both DMDD and ODD, only the DMDD diagnosis should be considered. One of many issues of DMDD is its similarity to ODD. In fact, more than 70% of patients with DMDD also meet the diagnostic criteria for ODD.10,14 Some researchers have conceptualized DMDD as a severe form of ODD. However, there are a few differences that clinicians can use to distinguish the 2 disorders.

Compared with patients with ODD, those with DMDD more frequently experience severe irritability.15 Patients with ODD may present with delinquent behaviors and trouble with authority figures. Moreover, comorbidity with ADHD is twice as common in ODD; more than 65% of patients with ADHD have ODD vs 30% who have DMDD.10,16 Finally, in general, children with DMDD have more social impairments compared with those with ODD. Differences between DMDD and BD are illustrated in Table 2.10,14-16

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2

Angry and defiant

Mr. R, age 14, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his parents after becoming very aggressive with them. He punched a wall and vandalized his room after his parents grounded him because of his previous defiant behavior. He had been suspended from school that day for disrespecting his teacher after he was caught fighting another student.

His parents describe Mr. R as a strong-willed, stubborn child. He has difficulty with rules and refuses to follow them. He is grouchy and irritable around adults, including the ED staff. Mr. R enjoys being with his friends and playing video games. He had been diagnosed with ADHD when he was in kindergarten, when his teacher noticed he had a poor attention span and could not sit still. According to his parents, Mr. R has “blown up” a few times before, smashing items in his room and shouting obscenities. Mr. R’s parents noticed that he is more defiant in concurrence with discontinuing his ADHD stimulant medication.

Diagnosis. The most likely diagnosis for Mr. R is ODD. Notice the comorbidity of ADHD, which is more commonly associated with ODD. The frequency and severity of his outbursts and irritability symptoms were lower than that typically associated with DMDD.

_

Treatment strategies for DMDD

Management of DMDD should focus on helping children and adolescents improve their emotional dysregulation.

Clinicians should always consider behavioral therapy as a first-line intervention. The behavioral planning team may include (but is not limited to) a behavior specialist, child psychiatrist, psychologist, therapist, skills trainer, teachers, and the caregiver(s). The plan should be implemented across all settings, including home and school. Furthermore, social skills training is necessary for many children with DMDD, who may require intensive behavioral modification planning. Comorbidity with ADHD should be addressed with a combination of behavioral planning and stimulant medications.17 If available, parent training and parent-child interactive therapy can help to improve defiant behavior.

Pharmacotherapy

Currently, no medications are FDA-approved for treating DMDD. Most pharmacologic trials that included patients with DMDD focused on managing chronic irritability and/or stabilizing comorbid disorders (ie, ADHD, depression, and anxiety).

Continue to: Stimulants

Stimulants. Previous trials examined the benefit of CNS stimulant medications, alone or in conjunction with behavioral therapy, in treating DMDD and comorbid ADHD. Methylphenidate results in a significant reduction in aggression18 with a dosing recommendation range from 1 to 1.2 mg/kg/d. CNS stimulants should be considered as first-line pharmacotherapy for DMDD, especially for patients with comorbid ADHD.

Anticonvulsants. Divalproex sodium is superior to placebo in treating aggression in children and adolescents.19 Trials found that divalproex sodium reduces irritability and aggression whether it is prescribed as monotherapy or combined with stimulant medications.19

Lithium is one of the main treatment options for mania in BD. The benefits of lithium for controlling aggression in DMDD are still under investigation. Earlier studies found that lithium significantly improves aggressive behavior in hospitalized pediatric with conduct disorder.20,21 However, a later study that evaluated lithium vs placebo for children with SMD (which arguably is phenotypically related to the DMDD) found there were no significant differences in improvement of irritability symptoms between groups.22 More research is needed to determine if lithium may play a role in treating patients with DMDD.

Antipsychotics. Aripiprazole and risperidone are FDA-approved for treating irritability in autism. A 2017 meta-analysis found both medications were effective in controlling irritability and aggression in other diagnoses as well.23 Other antipsychotic medications did not show sufficient benefits in treating irritability.23 When considering antipsychotics, clinicians should weigh the risks of metabolic adverse effects and follow practice guidelines.

Antidepressants. A systematic review did not find that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors effectively reduce irritability.24 However, in most of the studies evaluated, irritability was not the primary outcome measure.24

Other medications. Alpha-2 agonists (guanfacine, clonidine), and atomoxetine may help irritability indirectly by improving ADHD symptoms.25

Bottom Line

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), bipolar disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder have similar presentations and diagnostic criteria. The frequency and severity of irritability can be a distinguishing factor. Behavioral therapy is a first-line treatment. No medications are FDA-approved for treating DMDD, but pharmacotherapy may help reduce irritability and aggression.

Related Resources

- Rao U. DSM-5: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;11:119-123.

- Roy AK, Lopes V, Klein RG. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: a new diagnostic approach to chronic irritability in youth. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(9):918-924.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Clonidine • Catapres

Divalproex sodium • Depakote, Depakote ER

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE, et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(1):59-70.

2. Axelson D. Taking disruptive mood dysregulation disorder out for a test drive. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):136-139.

3. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, et al. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):795-804.

4. Case BG, Olfson M, Marcus SC, et al. Trends in the inpatient mental health treatment of children and adolescents in US community hospitals between 1990 and 2000. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):89-96.

5. Pliszka S; AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):894-921.

6. Hunt J, Birmaher B, Leonard H, et al. Irritability without elation in a large bipolar youth sample: frequency and clinical description. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(7):730-739.

7. Leibenluft E. Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(2):129-142.

8. Rich BA, Carver FW, Holroyd T, et al. Different neural pathways to negative affect in youth with pediatric bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(10):1283-1294.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of DSM-5 proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):173-179.

11. Elmaadawi AZ, Jensen PS, Arnold LE, et al. Risk for emerging bipolar disorder, variants, and symptoms in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, now grown up. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(4):412-424.

12. Duffy A. The early natural history of bipolar disorder: what we have learned from longitudinal high-risk research. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(8):477-485.

13. Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine DS, et al. Adult outcomes of youth irritability: a 20-year prospective community-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1048-1054.

14. Mayes SD, Waxmonsky JD, Calhoun SL, et al. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder symptoms and association with oppositional defiant and other disorders in a general population child sample. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(2):101-106.

15. Stringaris A, Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, et al. Practitioner review: definition, recognition, and treatment challenges of irritability in young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(7):721-739.

16. Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):57-87.

17. Fernandez de la Cruz L, Simonoff E, McGough JJ, et al. Treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and irritability: results from the multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD (MTA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(1):62-70.

18. Pappadopulos E, Woolston S, Chait A, et al. Pharmacotherapy of aggression in children and adolescents: efficacy and effect size. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(1):27-39.

19. Donovan SJ, Stewart JW, Nunes EV, et al. Divalproex treatment for youth with explosive temper and mood lability: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):818-820.

20. Campbell M, Adams PB, Small AM, et al. Lithium in hospitalized aggressive children with conduct disorder: a double-blind and placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(4):445-453.

21. Malone RP, Delaney MA, Luebbert JF, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lithium in hospitalized aggressive children and adolescents with conduct disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):649-654.

22. Dickstein DP, Towbin KE, Van Der Veen JW, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of lithium in youths with severe mood dysregulation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):61-73.

23. van Schalkwyk GI, Lewis AS, Beyer C, et al. Efficacy of antipsychotics for irritability and aggression in children: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(10):1045-1053.

24. Kim S, Boylan K. Effectiveness of antidepressant medications for symptoms of irritability and disruptive behaviors in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(8):694-704.

25. Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, et al. A placebo-controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1067-1074.

1. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE, et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(1):59-70.

2. Axelson D. Taking disruptive mood dysregulation disorder out for a test drive. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):136-139.

3. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, et al. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):795-804.

4. Case BG, Olfson M, Marcus SC, et al. Trends in the inpatient mental health treatment of children and adolescents in US community hospitals between 1990 and 2000. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):89-96.

5. Pliszka S; AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):894-921.

6. Hunt J, Birmaher B, Leonard H, et al. Irritability without elation in a large bipolar youth sample: frequency and clinical description. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(7):730-739.

7. Leibenluft E. Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(2):129-142.

8. Rich BA, Carver FW, Holroyd T, et al. Different neural pathways to negative affect in youth with pediatric bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(10):1283-1294.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of DSM-5 proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):173-179.

11. Elmaadawi AZ, Jensen PS, Arnold LE, et al. Risk for emerging bipolar disorder, variants, and symptoms in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, now grown up. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(4):412-424.

12. Duffy A. The early natural history of bipolar disorder: what we have learned from longitudinal high-risk research. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(8):477-485.

13. Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine DS, et al. Adult outcomes of youth irritability: a 20-year prospective community-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1048-1054.

14. Mayes SD, Waxmonsky JD, Calhoun SL, et al. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder symptoms and association with oppositional defiant and other disorders in a general population child sample. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(2):101-106.

15. Stringaris A, Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, et al. Practitioner review: definition, recognition, and treatment challenges of irritability in young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(7):721-739.

16. Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):57-87.

17. Fernandez de la Cruz L, Simonoff E, McGough JJ, et al. Treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and irritability: results from the multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD (MTA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(1):62-70.

18. Pappadopulos E, Woolston S, Chait A, et al. Pharmacotherapy of aggression in children and adolescents: efficacy and effect size. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(1):27-39.

19. Donovan SJ, Stewart JW, Nunes EV, et al. Divalproex treatment for youth with explosive temper and mood lability: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):818-820.

20. Campbell M, Adams PB, Small AM, et al. Lithium in hospitalized aggressive children with conduct disorder: a double-blind and placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(4):445-453.

21. Malone RP, Delaney MA, Luebbert JF, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lithium in hospitalized aggressive children and adolescents with conduct disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):649-654.

22. Dickstein DP, Towbin KE, Van Der Veen JW, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of lithium in youths with severe mood dysregulation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(1):61-73.

23. van Schalkwyk GI, Lewis AS, Beyer C, et al. Efficacy of antipsychotics for irritability and aggression in children: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(10):1045-1053.

24. Kim S, Boylan K. Effectiveness of antidepressant medications for symptoms of irritability and disruptive behaviors in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(8):694-704.

25. Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, et al. A placebo-controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1067-1074.