User login

Dear colleagues and friends,

The Perspectives series continues! There are few issues in our discipline that are as challenging, and controversial, as liver transplant prioritization. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) has been the mainstay for organ allocation for nearly 2 decades, and there has been vigorous debate as to whether it should remain so. In this issue, Dr. Jasmohan Bajaj and Dr. Julie Heimbach discuss the strengths and limitations of MELD and provide a vision of upcoming developments. As always, I welcome your feedback and suggestions for future topics at [email protected].

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Yes, it’s time for an update

BY JASMOHAN S. BAJAJ, MD, AGAF

Since February 2002, the U.S.-based liver transplant system has adopted the MELD score for transplant priority. Initially developed to predict outcomes after transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt, it was modified to exclude etiology for the purpose of listing patients.1

There were several advantages with MELD including objectivity, ease of calculation using a website, and over time, a burgeoning experience nationwide that extended even beyond transplant. Moreover, it focused on “sickest-first,” did away with the extremely “manipulable” waiting list, and left off hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and ascites severity.1 However, even earlier on, there were concerns regarding not capturing hepatocellular cancer (HCC) and some complications of cirrhosis that required exceptions. The points awarded to all these exceptions also changed with time, with lower priority and reincorporation of the waiting list time for HCC. Over time, the addition of serum sodium led it to be converted to “MELD-Na,” which now remains the primary method for transplant listing priority.

But the population with cirrhosis that existed 20 years ago has shifted radically. Patients with cirrhosis currently tend to either be much older with more comorbid conditions that predispose them to chronic kidney disease and cerebrovascular and cardiovascular compromise or be younger with an earlier presentation of alcohol-associated hepatitis. Moreover, the widespread availability of hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication has changed the landscape and stopped the progression of cirrhosis organically by virtually removing that etiology. This is relevant because a recent United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) analysis showed that the concordance between MELD score and 90-day mortality was the lowest in the rapidly increasing population with alcohol-related and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease etiologies, but conversely, this concordance was the highest in the population with hepatitis C–related cirrhosis.2 These demographic shifts in age and changes in etiology likely lessen the predictive power of the current MELD score iteration.

There is also increasing evidence that MELD is “stuck in the middle.” This means that both patients at low MELD score and those with organ failures may be underserved with respect to transplant listing with the current MELD score iteration.

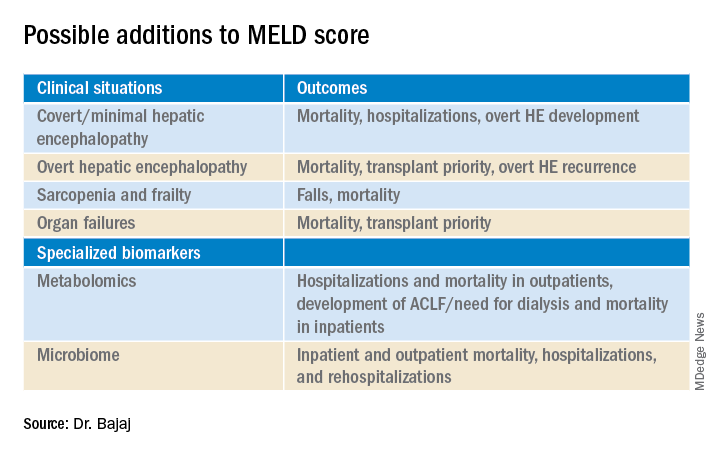

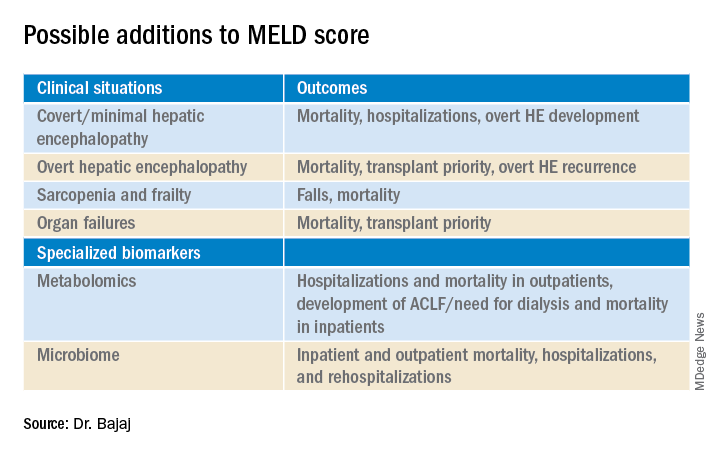

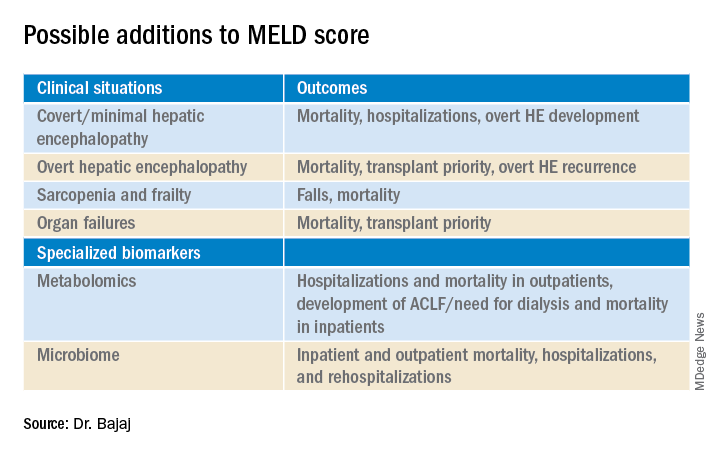

Among patients with a MELD score disproportionately lower than their complications of cirrhosis several studies demonstrate the improvement in prognostication with addition of covert HE, history of overt HE, frailty, and sarcopenia indices. These are independently prognostic variables that affect daily function, affect patient-reported outcomes, and can influence readmissions. The burden of impending falls, readmissions, infections, and overall ill health is not captured even though relatively objective methods such as cognitive tests and documented admissions for overt HE can be utilized.3 This relative mistrust in including HE and covariables likely harkens back to a dramatic reduction in grade III/IV HE severity seen the year after MELD introduction, when compared with the year before, during which that designation was added to the listing priority.4 However, objective additions to the MELD score that capture the distress of patients and their families with multiple readmissions for HE worsened by sarcopenia are desperately needed (see table).

On the other extreme, there is an increasing recognition of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and higher acceptability for transplanting alcohol-associated hepatitis (AAH).5 Prognostic variables in AAH have relied on Maddrey’s score and MELD score as well as the dynamic Lille score. The ability of MELD to predict outcomes is variable, but it is still required for listing these critical patients. A relatively newer entity, ACLF is defined variably across the world. In retrospective studies of the UNOS database in which patients were listed based on native MELD score rather than ACLF grades, there was a cut-off beyond which transplant was not useful. However, there is evidence that organ failures that do not involve creatinine or INR can influence survival independent of the MELD score.5 The rapidly increasing burden of critical illness may force a rethink of allocation policies, but a recent survey among U.S.-based transplant providers found little appetite to do so currently.

Objectivity is a major strength of the MELD score, but several systemic issues, including creatinine variability by sex, interlaboratory inconsistencies in laboratory results, and lack of accounting for international normalized ratio (INR) changes in those on warfarin or other INR-prolonging medications, to name a few that still exist.6 However, in our zeal to list patients and get the maximum chance for organ offers, there is a tendency to maximize or inflate the listing scores. This hope to provide the best care for patients under our specific care could come at the expense of patients listed elsewhere, but no score, however objective, is going to completely eliminate this possibility.

So, does this mean MELD-Na should be abandoned?

Absolutely not. An ecosystem of practitioners has now grown up under this system in the U.S., and it is rapidly being exported to other parts of the world. As with everything else, we need to keep up with the times, and for the popular MELD score, it needs to be responsive to issues at both extremes of cirrhosis severity. Studies on specialized markers such as serum, urine, and stool metabolomics as well as microbiome could be an objective addition to MELD score, but further studies are needed. It is also likely that artificial intelligence approaches could be used to not only improve access but also geographic equity that has plagued liver transplant in the U.S.

In the immortal words of Bob Dylan, “The times, they are a-changin’ …” We have to make sure the MELD score does too.

Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, is with the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and Richmond VA Medical Center. He has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Kamath PS and Kim WR. Hepatology. 2007;45:797-805.

2. Godfrey EL et al. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:3299-307.

3. Acharya C and Bajaj JS. Liver Transpl. 2021 May 21. doi:10.1002/lt.26099.

4. Bajaj JS and Saeian K. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:753-6.

5. Artru F and Samuel D. JHEP Rep 2019 May;1(1):53-65.

6. Bernardi M et al. J Hepatol 2010 Dec 9;54:1297-306.

Maybe, but take it slow

BY JULIE K. HEIMBACH, MD

Even though 2020 was another record year for organ donation in the United States, a truly remarkable feat considering the profound impact of COVID-19 on health care as well as the population at large, there remains a critical shortage of available liver allografts.1 Last year in the U.S., of the approximately 13,000 patients waiting for a liver transplant, just under 9,000 patients underwent liver transplantation from a deceased or a living donor, while 2,345 either died waiting on the list or were removed for being too sick, and the rest remained waiting.1 In a perfect system, we would transplant every wait-listed patient at a time that would provide them the greatest benefit with the least amount of distress. However, because of the shortage of available organs for transplantation, an allocation system to rank wait-listed candidates is required. Because organ transplantation relies on the incredible altruism of individuals and their family members who make this ultimate gift on their behalf, it is crucial both for donor families and for waiting recipients that organ allocation be transparent, as fair and equitable as possible, and compliant with federal law, which is currently determined by the “Final Rule” that states that organ allocation be based in order of urgency.2

Since February 2002, U.S. liver allocation policy has been based on MELD.3 Prior to that time, liver allocation was based in part on the Child-Turcot-Pugh classification of liver disease, which included subjective components (ascites and encephalopathy) that are difficult to measure, as well as increased priority based on admission to the intensive care unit, also subjective and open to interpretation or abuse. Most crucially, the system defaulted to length of waiting time with large numbers of patients in the same category, which led to higher death rates for patients whose disease progressed more quickly or who were referred very late in their disease course.

MELD relies on a simple set of laboratory values that are easily obtained at any clinical lab and are already being routinely monitored as part of standard care for patients with end-stage liver disease.3 MELD initially required just three variables (bilirubin, creatinine, INR) and was updated to include just four variables with the adoption of MELD-Na in 2016, which added sodium levels. The MELD- and MELD-Na–based approach is a highly reliable, accurate way to rank patients who are most at risk of death in the next 3 months, with a C statistic of approximately 0.83-0.84.3,4 Perhaps the greatest testament to the strength of MELD is that, following the adoption of MELD-based liver allocation, MELD has gradually been adopted as the system of liver allocation by most countries around the world.

With the adoption of MELD and subsequently MELD-Na, which prioritize deceased donor liver allografts to the sickest patients first and is therefore compliant with the Final Rule, outcomes for patients waiting for liver transplant have steadily improved.3,4 In addition, MELD has provided an easily obtainable, objective measure to guide decisions about timing of liver transplant, especially in the setting of potential living donor liver transplantation. MELD is also predictive of outcome for patients undergoing nontransplant elective and emergent surgical procedures, and because of the ease in calculating the score, it allows for an objective comparison of patients with cirrhosis across a variety of clinical and research settings.

The MELD system has many additional strengths, though perhaps the most important is that it is adaptable. While the MELD score accurately predicts death from chronic liver disease, the MELD score is not able to predict mortality or risk of wait-list dropout due to disease progression from certain complications of chronic liver disease such as the development of HCC or hepatopulmonary syndrome, in which access to timely transplantation has been proven to be beneficial. This has required an adaption to the system whereby candidates with conditions, such as HCC, that meet specific criteria receive an assigned MELD score, rather than a calculated score. Determining which patients should qualify for MELD exceptions, as well as what the assigned priority score should be, has required careful analysis and ongoing revision. An additional issue for MELD, which was identified more than a decade ago and is overdue for adjustment, is the disparity in access to transplant for women who continue to experience a lower transplant rate (14.4% according to the most recent analysis) and approximately 8.6% higher death rate than men with the same MELD score.5 This is due, in part, to the use of creatinine in the MELD equation, which as a by-product of muscle metabolism, underestimates the degree of renal dysfunction in women and thus underestimates their risk of wait-list mortality.5 A potential modification to the MELD-Na score that corrects for this sex-based disparity is currently being studied by the OPTN Liver-Intestine committee, which is further evidence of the strength and adaptability of a MELD-based allocation system.

While it is tempting to conclude that a system that requires on-going monitoring and revision is best discarded in favor of a new model such as an artificial intelligence–based solution, policy development requires a tremendous amount of time for consensus-building, as well as effort to ensure that unexpected negative effects are not created. Whereas a novel system could be identified and determined to be superior down the road, the amount of effort and expense that would be needed to build consensus around such a new model should not be underestimated. Considering the challenges to health care and the population at large that are already occurring as we emerge from the COVID pandemic, as well as the short-term need to monitor the impact from the recent adoption of the acuity circle model which went live in February 2020 and allocates according to MELD but over a broader geographic area based on a circle around the donor hospital, building consensus around incremental changes to a MELD-based allocation system likely represents the best option in our continued quest for the optimal liver allocation system.

Julie K. Heimbach, MD, is a transplant surgeon and the surgical director of liver transplantation at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. She has no conflicts to report.

References

1. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network data. Available at https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data. Accessed May 1, 2021.

2. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Final rule. Available at https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/about-the-optn/final-rule. Accessed May 1, 2021.

3. Wiesner R et al; United Network for Organ Sharing Liver Disease Severity Score Committee. Gastroenterology. 2003 Jan;124(1):91-6.

4. Nagai S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov;155(5):1451-62.e3.

5. Locke JE et al. JAMA Surg. 2020 Jul 1;155(7):e201129.

Dear colleagues and friends,

The Perspectives series continues! There are few issues in our discipline that are as challenging, and controversial, as liver transplant prioritization. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) has been the mainstay for organ allocation for nearly 2 decades, and there has been vigorous debate as to whether it should remain so. In this issue, Dr. Jasmohan Bajaj and Dr. Julie Heimbach discuss the strengths and limitations of MELD and provide a vision of upcoming developments. As always, I welcome your feedback and suggestions for future topics at [email protected].

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Yes, it’s time for an update

BY JASMOHAN S. BAJAJ, MD, AGAF

Since February 2002, the U.S.-based liver transplant system has adopted the MELD score for transplant priority. Initially developed to predict outcomes after transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt, it was modified to exclude etiology for the purpose of listing patients.1

There were several advantages with MELD including objectivity, ease of calculation using a website, and over time, a burgeoning experience nationwide that extended even beyond transplant. Moreover, it focused on “sickest-first,” did away with the extremely “manipulable” waiting list, and left off hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and ascites severity.1 However, even earlier on, there were concerns regarding not capturing hepatocellular cancer (HCC) and some complications of cirrhosis that required exceptions. The points awarded to all these exceptions also changed with time, with lower priority and reincorporation of the waiting list time for HCC. Over time, the addition of serum sodium led it to be converted to “MELD-Na,” which now remains the primary method for transplant listing priority.

But the population with cirrhosis that existed 20 years ago has shifted radically. Patients with cirrhosis currently tend to either be much older with more comorbid conditions that predispose them to chronic kidney disease and cerebrovascular and cardiovascular compromise or be younger with an earlier presentation of alcohol-associated hepatitis. Moreover, the widespread availability of hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication has changed the landscape and stopped the progression of cirrhosis organically by virtually removing that etiology. This is relevant because a recent United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) analysis showed that the concordance between MELD score and 90-day mortality was the lowest in the rapidly increasing population with alcohol-related and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease etiologies, but conversely, this concordance was the highest in the population with hepatitis C–related cirrhosis.2 These demographic shifts in age and changes in etiology likely lessen the predictive power of the current MELD score iteration.

There is also increasing evidence that MELD is “stuck in the middle.” This means that both patients at low MELD score and those with organ failures may be underserved with respect to transplant listing with the current MELD score iteration.

Among patients with a MELD score disproportionately lower than their complications of cirrhosis several studies demonstrate the improvement in prognostication with addition of covert HE, history of overt HE, frailty, and sarcopenia indices. These are independently prognostic variables that affect daily function, affect patient-reported outcomes, and can influence readmissions. The burden of impending falls, readmissions, infections, and overall ill health is not captured even though relatively objective methods such as cognitive tests and documented admissions for overt HE can be utilized.3 This relative mistrust in including HE and covariables likely harkens back to a dramatic reduction in grade III/IV HE severity seen the year after MELD introduction, when compared with the year before, during which that designation was added to the listing priority.4 However, objective additions to the MELD score that capture the distress of patients and their families with multiple readmissions for HE worsened by sarcopenia are desperately needed (see table).

On the other extreme, there is an increasing recognition of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and higher acceptability for transplanting alcohol-associated hepatitis (AAH).5 Prognostic variables in AAH have relied on Maddrey’s score and MELD score as well as the dynamic Lille score. The ability of MELD to predict outcomes is variable, but it is still required for listing these critical patients. A relatively newer entity, ACLF is defined variably across the world. In retrospective studies of the UNOS database in which patients were listed based on native MELD score rather than ACLF grades, there was a cut-off beyond which transplant was not useful. However, there is evidence that organ failures that do not involve creatinine or INR can influence survival independent of the MELD score.5 The rapidly increasing burden of critical illness may force a rethink of allocation policies, but a recent survey among U.S.-based transplant providers found little appetite to do so currently.

Objectivity is a major strength of the MELD score, but several systemic issues, including creatinine variability by sex, interlaboratory inconsistencies in laboratory results, and lack of accounting for international normalized ratio (INR) changes in those on warfarin or other INR-prolonging medications, to name a few that still exist.6 However, in our zeal to list patients and get the maximum chance for organ offers, there is a tendency to maximize or inflate the listing scores. This hope to provide the best care for patients under our specific care could come at the expense of patients listed elsewhere, but no score, however objective, is going to completely eliminate this possibility.

So, does this mean MELD-Na should be abandoned?

Absolutely not. An ecosystem of practitioners has now grown up under this system in the U.S., and it is rapidly being exported to other parts of the world. As with everything else, we need to keep up with the times, and for the popular MELD score, it needs to be responsive to issues at both extremes of cirrhosis severity. Studies on specialized markers such as serum, urine, and stool metabolomics as well as microbiome could be an objective addition to MELD score, but further studies are needed. It is also likely that artificial intelligence approaches could be used to not only improve access but also geographic equity that has plagued liver transplant in the U.S.

In the immortal words of Bob Dylan, “The times, they are a-changin’ …” We have to make sure the MELD score does too.

Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, is with the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and Richmond VA Medical Center. He has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Kamath PS and Kim WR. Hepatology. 2007;45:797-805.

2. Godfrey EL et al. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:3299-307.

3. Acharya C and Bajaj JS. Liver Transpl. 2021 May 21. doi:10.1002/lt.26099.

4. Bajaj JS and Saeian K. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:753-6.

5. Artru F and Samuel D. JHEP Rep 2019 May;1(1):53-65.

6. Bernardi M et al. J Hepatol 2010 Dec 9;54:1297-306.

Maybe, but take it slow

BY JULIE K. HEIMBACH, MD

Even though 2020 was another record year for organ donation in the United States, a truly remarkable feat considering the profound impact of COVID-19 on health care as well as the population at large, there remains a critical shortage of available liver allografts.1 Last year in the U.S., of the approximately 13,000 patients waiting for a liver transplant, just under 9,000 patients underwent liver transplantation from a deceased or a living donor, while 2,345 either died waiting on the list or were removed for being too sick, and the rest remained waiting.1 In a perfect system, we would transplant every wait-listed patient at a time that would provide them the greatest benefit with the least amount of distress. However, because of the shortage of available organs for transplantation, an allocation system to rank wait-listed candidates is required. Because organ transplantation relies on the incredible altruism of individuals and their family members who make this ultimate gift on their behalf, it is crucial both for donor families and for waiting recipients that organ allocation be transparent, as fair and equitable as possible, and compliant with federal law, which is currently determined by the “Final Rule” that states that organ allocation be based in order of urgency.2

Since February 2002, U.S. liver allocation policy has been based on MELD.3 Prior to that time, liver allocation was based in part on the Child-Turcot-Pugh classification of liver disease, which included subjective components (ascites and encephalopathy) that are difficult to measure, as well as increased priority based on admission to the intensive care unit, also subjective and open to interpretation or abuse. Most crucially, the system defaulted to length of waiting time with large numbers of patients in the same category, which led to higher death rates for patients whose disease progressed more quickly or who were referred very late in their disease course.

MELD relies on a simple set of laboratory values that are easily obtained at any clinical lab and are already being routinely monitored as part of standard care for patients with end-stage liver disease.3 MELD initially required just three variables (bilirubin, creatinine, INR) and was updated to include just four variables with the adoption of MELD-Na in 2016, which added sodium levels. The MELD- and MELD-Na–based approach is a highly reliable, accurate way to rank patients who are most at risk of death in the next 3 months, with a C statistic of approximately 0.83-0.84.3,4 Perhaps the greatest testament to the strength of MELD is that, following the adoption of MELD-based liver allocation, MELD has gradually been adopted as the system of liver allocation by most countries around the world.

With the adoption of MELD and subsequently MELD-Na, which prioritize deceased donor liver allografts to the sickest patients first and is therefore compliant with the Final Rule, outcomes for patients waiting for liver transplant have steadily improved.3,4 In addition, MELD has provided an easily obtainable, objective measure to guide decisions about timing of liver transplant, especially in the setting of potential living donor liver transplantation. MELD is also predictive of outcome for patients undergoing nontransplant elective and emergent surgical procedures, and because of the ease in calculating the score, it allows for an objective comparison of patients with cirrhosis across a variety of clinical and research settings.

The MELD system has many additional strengths, though perhaps the most important is that it is adaptable. While the MELD score accurately predicts death from chronic liver disease, the MELD score is not able to predict mortality or risk of wait-list dropout due to disease progression from certain complications of chronic liver disease such as the development of HCC or hepatopulmonary syndrome, in which access to timely transplantation has been proven to be beneficial. This has required an adaption to the system whereby candidates with conditions, such as HCC, that meet specific criteria receive an assigned MELD score, rather than a calculated score. Determining which patients should qualify for MELD exceptions, as well as what the assigned priority score should be, has required careful analysis and ongoing revision. An additional issue for MELD, which was identified more than a decade ago and is overdue for adjustment, is the disparity in access to transplant for women who continue to experience a lower transplant rate (14.4% according to the most recent analysis) and approximately 8.6% higher death rate than men with the same MELD score.5 This is due, in part, to the use of creatinine in the MELD equation, which as a by-product of muscle metabolism, underestimates the degree of renal dysfunction in women and thus underestimates their risk of wait-list mortality.5 A potential modification to the MELD-Na score that corrects for this sex-based disparity is currently being studied by the OPTN Liver-Intestine committee, which is further evidence of the strength and adaptability of a MELD-based allocation system.

While it is tempting to conclude that a system that requires on-going monitoring and revision is best discarded in favor of a new model such as an artificial intelligence–based solution, policy development requires a tremendous amount of time for consensus-building, as well as effort to ensure that unexpected negative effects are not created. Whereas a novel system could be identified and determined to be superior down the road, the amount of effort and expense that would be needed to build consensus around such a new model should not be underestimated. Considering the challenges to health care and the population at large that are already occurring as we emerge from the COVID pandemic, as well as the short-term need to monitor the impact from the recent adoption of the acuity circle model which went live in February 2020 and allocates according to MELD but over a broader geographic area based on a circle around the donor hospital, building consensus around incremental changes to a MELD-based allocation system likely represents the best option in our continued quest for the optimal liver allocation system.

Julie K. Heimbach, MD, is a transplant surgeon and the surgical director of liver transplantation at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. She has no conflicts to report.

References

1. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network data. Available at https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data. Accessed May 1, 2021.

2. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Final rule. Available at https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/about-the-optn/final-rule. Accessed May 1, 2021.

3. Wiesner R et al; United Network for Organ Sharing Liver Disease Severity Score Committee. Gastroenterology. 2003 Jan;124(1):91-6.

4. Nagai S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov;155(5):1451-62.e3.

5. Locke JE et al. JAMA Surg. 2020 Jul 1;155(7):e201129.

Dear colleagues and friends,

The Perspectives series continues! There are few issues in our discipline that are as challenging, and controversial, as liver transplant prioritization. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) has been the mainstay for organ allocation for nearly 2 decades, and there has been vigorous debate as to whether it should remain so. In this issue, Dr. Jasmohan Bajaj and Dr. Julie Heimbach discuss the strengths and limitations of MELD and provide a vision of upcoming developments. As always, I welcome your feedback and suggestions for future topics at [email protected].

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Yes, it’s time for an update

BY JASMOHAN S. BAJAJ, MD, AGAF

Since February 2002, the U.S.-based liver transplant system has adopted the MELD score for transplant priority. Initially developed to predict outcomes after transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt, it was modified to exclude etiology for the purpose of listing patients.1

There were several advantages with MELD including objectivity, ease of calculation using a website, and over time, a burgeoning experience nationwide that extended even beyond transplant. Moreover, it focused on “sickest-first,” did away with the extremely “manipulable” waiting list, and left off hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and ascites severity.1 However, even earlier on, there were concerns regarding not capturing hepatocellular cancer (HCC) and some complications of cirrhosis that required exceptions. The points awarded to all these exceptions also changed with time, with lower priority and reincorporation of the waiting list time for HCC. Over time, the addition of serum sodium led it to be converted to “MELD-Na,” which now remains the primary method for transplant listing priority.

But the population with cirrhosis that existed 20 years ago has shifted radically. Patients with cirrhosis currently tend to either be much older with more comorbid conditions that predispose them to chronic kidney disease and cerebrovascular and cardiovascular compromise or be younger with an earlier presentation of alcohol-associated hepatitis. Moreover, the widespread availability of hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication has changed the landscape and stopped the progression of cirrhosis organically by virtually removing that etiology. This is relevant because a recent United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) analysis showed that the concordance between MELD score and 90-day mortality was the lowest in the rapidly increasing population with alcohol-related and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease etiologies, but conversely, this concordance was the highest in the population with hepatitis C–related cirrhosis.2 These demographic shifts in age and changes in etiology likely lessen the predictive power of the current MELD score iteration.

There is also increasing evidence that MELD is “stuck in the middle.” This means that both patients at low MELD score and those with organ failures may be underserved with respect to transplant listing with the current MELD score iteration.

Among patients with a MELD score disproportionately lower than their complications of cirrhosis several studies demonstrate the improvement in prognostication with addition of covert HE, history of overt HE, frailty, and sarcopenia indices. These are independently prognostic variables that affect daily function, affect patient-reported outcomes, and can influence readmissions. The burden of impending falls, readmissions, infections, and overall ill health is not captured even though relatively objective methods such as cognitive tests and documented admissions for overt HE can be utilized.3 This relative mistrust in including HE and covariables likely harkens back to a dramatic reduction in grade III/IV HE severity seen the year after MELD introduction, when compared with the year before, during which that designation was added to the listing priority.4 However, objective additions to the MELD score that capture the distress of patients and their families with multiple readmissions for HE worsened by sarcopenia are desperately needed (see table).

On the other extreme, there is an increasing recognition of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and higher acceptability for transplanting alcohol-associated hepatitis (AAH).5 Prognostic variables in AAH have relied on Maddrey’s score and MELD score as well as the dynamic Lille score. The ability of MELD to predict outcomes is variable, but it is still required for listing these critical patients. A relatively newer entity, ACLF is defined variably across the world. In retrospective studies of the UNOS database in which patients were listed based on native MELD score rather than ACLF grades, there was a cut-off beyond which transplant was not useful. However, there is evidence that organ failures that do not involve creatinine or INR can influence survival independent of the MELD score.5 The rapidly increasing burden of critical illness may force a rethink of allocation policies, but a recent survey among U.S.-based transplant providers found little appetite to do so currently.

Objectivity is a major strength of the MELD score, but several systemic issues, including creatinine variability by sex, interlaboratory inconsistencies in laboratory results, and lack of accounting for international normalized ratio (INR) changes in those on warfarin or other INR-prolonging medications, to name a few that still exist.6 However, in our zeal to list patients and get the maximum chance for organ offers, there is a tendency to maximize or inflate the listing scores. This hope to provide the best care for patients under our specific care could come at the expense of patients listed elsewhere, but no score, however objective, is going to completely eliminate this possibility.

So, does this mean MELD-Na should be abandoned?

Absolutely not. An ecosystem of practitioners has now grown up under this system in the U.S., and it is rapidly being exported to other parts of the world. As with everything else, we need to keep up with the times, and for the popular MELD score, it needs to be responsive to issues at both extremes of cirrhosis severity. Studies on specialized markers such as serum, urine, and stool metabolomics as well as microbiome could be an objective addition to MELD score, but further studies are needed. It is also likely that artificial intelligence approaches could be used to not only improve access but also geographic equity that has plagued liver transplant in the U.S.

In the immortal words of Bob Dylan, “The times, they are a-changin’ …” We have to make sure the MELD score does too.

Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, is with the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and Richmond VA Medical Center. He has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Kamath PS and Kim WR. Hepatology. 2007;45:797-805.

2. Godfrey EL et al. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:3299-307.

3. Acharya C and Bajaj JS. Liver Transpl. 2021 May 21. doi:10.1002/lt.26099.

4. Bajaj JS and Saeian K. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:753-6.

5. Artru F and Samuel D. JHEP Rep 2019 May;1(1):53-65.

6. Bernardi M et al. J Hepatol 2010 Dec 9;54:1297-306.

Maybe, but take it slow

BY JULIE K. HEIMBACH, MD

Even though 2020 was another record year for organ donation in the United States, a truly remarkable feat considering the profound impact of COVID-19 on health care as well as the population at large, there remains a critical shortage of available liver allografts.1 Last year in the U.S., of the approximately 13,000 patients waiting for a liver transplant, just under 9,000 patients underwent liver transplantation from a deceased or a living donor, while 2,345 either died waiting on the list or were removed for being too sick, and the rest remained waiting.1 In a perfect system, we would transplant every wait-listed patient at a time that would provide them the greatest benefit with the least amount of distress. However, because of the shortage of available organs for transplantation, an allocation system to rank wait-listed candidates is required. Because organ transplantation relies on the incredible altruism of individuals and their family members who make this ultimate gift on their behalf, it is crucial both for donor families and for waiting recipients that organ allocation be transparent, as fair and equitable as possible, and compliant with federal law, which is currently determined by the “Final Rule” that states that organ allocation be based in order of urgency.2

Since February 2002, U.S. liver allocation policy has been based on MELD.3 Prior to that time, liver allocation was based in part on the Child-Turcot-Pugh classification of liver disease, which included subjective components (ascites and encephalopathy) that are difficult to measure, as well as increased priority based on admission to the intensive care unit, also subjective and open to interpretation or abuse. Most crucially, the system defaulted to length of waiting time with large numbers of patients in the same category, which led to higher death rates for patients whose disease progressed more quickly or who were referred very late in their disease course.

MELD relies on a simple set of laboratory values that are easily obtained at any clinical lab and are already being routinely monitored as part of standard care for patients with end-stage liver disease.3 MELD initially required just three variables (bilirubin, creatinine, INR) and was updated to include just four variables with the adoption of MELD-Na in 2016, which added sodium levels. The MELD- and MELD-Na–based approach is a highly reliable, accurate way to rank patients who are most at risk of death in the next 3 months, with a C statistic of approximately 0.83-0.84.3,4 Perhaps the greatest testament to the strength of MELD is that, following the adoption of MELD-based liver allocation, MELD has gradually been adopted as the system of liver allocation by most countries around the world.

With the adoption of MELD and subsequently MELD-Na, which prioritize deceased donor liver allografts to the sickest patients first and is therefore compliant with the Final Rule, outcomes for patients waiting for liver transplant have steadily improved.3,4 In addition, MELD has provided an easily obtainable, objective measure to guide decisions about timing of liver transplant, especially in the setting of potential living donor liver transplantation. MELD is also predictive of outcome for patients undergoing nontransplant elective and emergent surgical procedures, and because of the ease in calculating the score, it allows for an objective comparison of patients with cirrhosis across a variety of clinical and research settings.

The MELD system has many additional strengths, though perhaps the most important is that it is adaptable. While the MELD score accurately predicts death from chronic liver disease, the MELD score is not able to predict mortality or risk of wait-list dropout due to disease progression from certain complications of chronic liver disease such as the development of HCC or hepatopulmonary syndrome, in which access to timely transplantation has been proven to be beneficial. This has required an adaption to the system whereby candidates with conditions, such as HCC, that meet specific criteria receive an assigned MELD score, rather than a calculated score. Determining which patients should qualify for MELD exceptions, as well as what the assigned priority score should be, has required careful analysis and ongoing revision. An additional issue for MELD, which was identified more than a decade ago and is overdue for adjustment, is the disparity in access to transplant for women who continue to experience a lower transplant rate (14.4% according to the most recent analysis) and approximately 8.6% higher death rate than men with the same MELD score.5 This is due, in part, to the use of creatinine in the MELD equation, which as a by-product of muscle metabolism, underestimates the degree of renal dysfunction in women and thus underestimates their risk of wait-list mortality.5 A potential modification to the MELD-Na score that corrects for this sex-based disparity is currently being studied by the OPTN Liver-Intestine committee, which is further evidence of the strength and adaptability of a MELD-based allocation system.

While it is tempting to conclude that a system that requires on-going monitoring and revision is best discarded in favor of a new model such as an artificial intelligence–based solution, policy development requires a tremendous amount of time for consensus-building, as well as effort to ensure that unexpected negative effects are not created. Whereas a novel system could be identified and determined to be superior down the road, the amount of effort and expense that would be needed to build consensus around such a new model should not be underestimated. Considering the challenges to health care and the population at large that are already occurring as we emerge from the COVID pandemic, as well as the short-term need to monitor the impact from the recent adoption of the acuity circle model which went live in February 2020 and allocates according to MELD but over a broader geographic area based on a circle around the donor hospital, building consensus around incremental changes to a MELD-based allocation system likely represents the best option in our continued quest for the optimal liver allocation system.

Julie K. Heimbach, MD, is a transplant surgeon and the surgical director of liver transplantation at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. She has no conflicts to report.

References

1. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network data. Available at https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data. Accessed May 1, 2021.

2. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Final rule. Available at https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/about-the-optn/final-rule. Accessed May 1, 2021.

3. Wiesner R et al; United Network for Organ Sharing Liver Disease Severity Score Committee. Gastroenterology. 2003 Jan;124(1):91-6.

4. Nagai S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov;155(5):1451-62.e3.

5. Locke JE et al. JAMA Surg. 2020 Jul 1;155(7):e201129.