User login

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

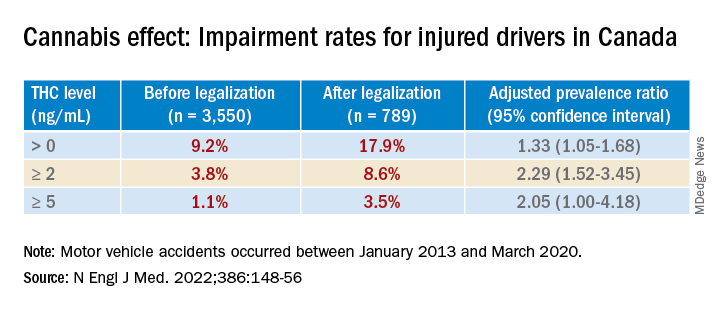

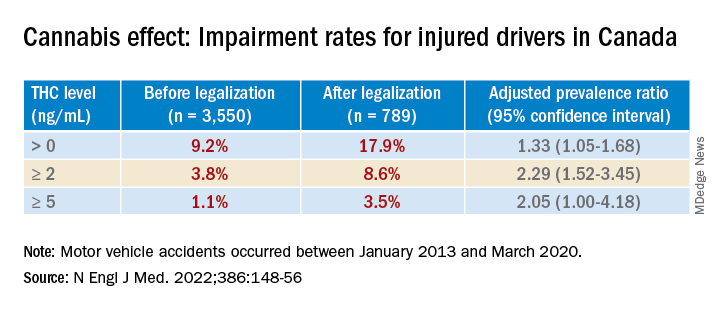

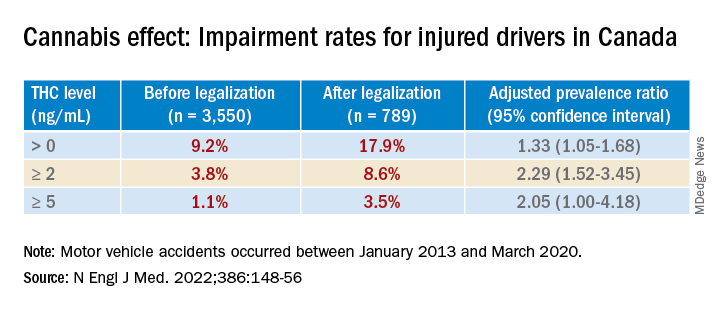

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.

The largest increases in a THC level of at least 2 ng/mL were in drivers 50 years of age or older and among male drivers (adjusted prevalence ratio, 5.18; 95% confidence interval, 2.49-10.78 and aPR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.60-3.74, respectively).

“There were no significant changes in the prevalence of drivers testing positive for alcohol,” the authors reported.

Dr. Brubacher said the evidence suggests these new laws “are not enough to stop everyone from driving after using cannabis.”

The findings have implications for clinicians and patients and for policymakers, he said. “My moderately conservative recommendations are that, if you are going to smoke cannabis, wait at least 4 hours after smoking before you drive. Edibles last longer, and patients should wait least 8 hours after ingesting [edibles] before driving. And of course, if you continue to feel the effects of the THC, you should avoid driving altogether until the time has elapsed and you no longer feel any effects.”

Dr. Brubacher hopes policy makers will use the study’s findings to “design public information campaigns and enforcement measures that encourage drivers, especially older drivers, to separate cannabis use from driving.”

Additionally, “policy makers shouldn’t lose sight of drinking and driving because that’s an even bigger problem than the risk of driving under the influence of cannabis.”

Focus on older adults

In a comment, Anees Bahji, MD, an International Collaborative Addiction Medicine research fellow at the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, called the study “interesting and relevant.”

He raised several questions regarding the “correlation between the level of a substance in a person’s system and the degree of impairment.” For example, “does the same level of THC in the blood affect us all the same way? And to what extent do the levels detected at the time of the analysis correlate with the level in the person’s system at the time of driving?”

An additional consideration “is for individuals with cannabis use disorder and for those who have developed tolerance to the psychoactive effects of THC: Does it affect their driving skills in the same way as someone who is cannabis naive?” asked Dr. Bahji, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Calgary (Alta.) who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting, Eric Sevigny, PhD, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University, Atlanta, described it as a “well-designed study that adds yet another data point for considering appropriate road safety policy responses alongside ongoing cannabis liberalization.”

However, the findings “cannot say much about whether cannabis legalization leads to an increase in cannabis-impaired driving, because current research finds little correlation between biological THC concentrations and driving performance,” said Dr. Sevigny, who was not involved with the study.

The finding of “higher THC prevalence among older adults is also relevant for road safety, as this population has a number of concomitant risk factors, such as cognitive decline and prescription drug use,” Dr. Sevigny added.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Brubacher and Dr. Sevigny disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bahji reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Calgary Health Trust, the American Psychiatric Association, NIDA, and the University of Calgary.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.

The largest increases in a THC level of at least 2 ng/mL were in drivers 50 years of age or older and among male drivers (adjusted prevalence ratio, 5.18; 95% confidence interval, 2.49-10.78 and aPR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.60-3.74, respectively).

“There were no significant changes in the prevalence of drivers testing positive for alcohol,” the authors reported.

Dr. Brubacher said the evidence suggests these new laws “are not enough to stop everyone from driving after using cannabis.”

The findings have implications for clinicians and patients and for policymakers, he said. “My moderately conservative recommendations are that, if you are going to smoke cannabis, wait at least 4 hours after smoking before you drive. Edibles last longer, and patients should wait least 8 hours after ingesting [edibles] before driving. And of course, if you continue to feel the effects of the THC, you should avoid driving altogether until the time has elapsed and you no longer feel any effects.”

Dr. Brubacher hopes policy makers will use the study’s findings to “design public information campaigns and enforcement measures that encourage drivers, especially older drivers, to separate cannabis use from driving.”

Additionally, “policy makers shouldn’t lose sight of drinking and driving because that’s an even bigger problem than the risk of driving under the influence of cannabis.”

Focus on older adults

In a comment, Anees Bahji, MD, an International Collaborative Addiction Medicine research fellow at the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, called the study “interesting and relevant.”

He raised several questions regarding the “correlation between the level of a substance in a person’s system and the degree of impairment.” For example, “does the same level of THC in the blood affect us all the same way? And to what extent do the levels detected at the time of the analysis correlate with the level in the person’s system at the time of driving?”

An additional consideration “is for individuals with cannabis use disorder and for those who have developed tolerance to the psychoactive effects of THC: Does it affect their driving skills in the same way as someone who is cannabis naive?” asked Dr. Bahji, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Calgary (Alta.) who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting, Eric Sevigny, PhD, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University, Atlanta, described it as a “well-designed study that adds yet another data point for considering appropriate road safety policy responses alongside ongoing cannabis liberalization.”

However, the findings “cannot say much about whether cannabis legalization leads to an increase in cannabis-impaired driving, because current research finds little correlation between biological THC concentrations and driving performance,” said Dr. Sevigny, who was not involved with the study.

The finding of “higher THC prevalence among older adults is also relevant for road safety, as this population has a number of concomitant risk factors, such as cognitive decline and prescription drug use,” Dr. Sevigny added.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Brubacher and Dr. Sevigny disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bahji reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Calgary Health Trust, the American Psychiatric Association, NIDA, and the University of Calgary.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.

The largest increases in a THC level of at least 2 ng/mL were in drivers 50 years of age or older and among male drivers (adjusted prevalence ratio, 5.18; 95% confidence interval, 2.49-10.78 and aPR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.60-3.74, respectively).

“There were no significant changes in the prevalence of drivers testing positive for alcohol,” the authors reported.

Dr. Brubacher said the evidence suggests these new laws “are not enough to stop everyone from driving after using cannabis.”

The findings have implications for clinicians and patients and for policymakers, he said. “My moderately conservative recommendations are that, if you are going to smoke cannabis, wait at least 4 hours after smoking before you drive. Edibles last longer, and patients should wait least 8 hours after ingesting [edibles] before driving. And of course, if you continue to feel the effects of the THC, you should avoid driving altogether until the time has elapsed and you no longer feel any effects.”

Dr. Brubacher hopes policy makers will use the study’s findings to “design public information campaigns and enforcement measures that encourage drivers, especially older drivers, to separate cannabis use from driving.”

Additionally, “policy makers shouldn’t lose sight of drinking and driving because that’s an even bigger problem than the risk of driving under the influence of cannabis.”

Focus on older adults

In a comment, Anees Bahji, MD, an International Collaborative Addiction Medicine research fellow at the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, called the study “interesting and relevant.”

He raised several questions regarding the “correlation between the level of a substance in a person’s system and the degree of impairment.” For example, “does the same level of THC in the blood affect us all the same way? And to what extent do the levels detected at the time of the analysis correlate with the level in the person’s system at the time of driving?”

An additional consideration “is for individuals with cannabis use disorder and for those who have developed tolerance to the psychoactive effects of THC: Does it affect their driving skills in the same way as someone who is cannabis naive?” asked Dr. Bahji, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Calgary (Alta.) who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting, Eric Sevigny, PhD, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University, Atlanta, described it as a “well-designed study that adds yet another data point for considering appropriate road safety policy responses alongside ongoing cannabis liberalization.”

However, the findings “cannot say much about whether cannabis legalization leads to an increase in cannabis-impaired driving, because current research finds little correlation between biological THC concentrations and driving performance,” said Dr. Sevigny, who was not involved with the study.

The finding of “higher THC prevalence among older adults is also relevant for road safety, as this population has a number of concomitant risk factors, such as cognitive decline and prescription drug use,” Dr. Sevigny added.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Brubacher and Dr. Sevigny disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bahji reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Calgary Health Trust, the American Psychiatric Association, NIDA, and the University of Calgary.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE